- Office of the Deputy Dean

- MD Admissions Committee

- Progress Committee

- EPCC Committee Minutes

- Thesis Chair Committee

- Curriculum Mapping Documents

- PreClerkship Policies

- Clerkship & ATP Policies

- University Policy Links

- Self-Study Task Force

- You said . . . We did . . .

- Faculty Training

- Renovation & Expansion of Student Space

- Faculty Mentor Responsibilities and Resources

- Departmental Thesis Chairs

- First-Year Summer Research

- Short-term Research

- One-year Fellowships

- Travel Info & Reimbursement

- Research Didactics

- START Summer Program

- Master of Health Science

- Student Research Day

- Forms, Deadlines & Funding

- Student Research Team

- Research Tradition

- How to Apply

- The Yale System

- Dates and Deadlines

- Pre-medical Requirements

- Admissions Team

- Electives & Subinternships

- Staying for a Fifth Year

- Academic Advisors

- Performance Improvement

- Residency Applications

- Meet our Staff & Make an Appointment

- Wellness Programming: Upcoming Events

- Peer Advocate Program

- Day in the life of Med student

- Hear our Experiences

- Student Affairs Team

- Application Process

- International Students

- 2024-2025 Budget

- 2023-2024 Budget

- 2022-2023 Budget

- 2021-2022 Budget

- 2020-2021 Budget

- 2019-2020 Budget

- 2018-2019 Budget

- 2017-2018 Budget

- 2016-2017 Budget

- 2015-2016 Budget

- 2014-2015 Budget

- Research Funding, Extended Study and Financial Aid

- Frequently Asked Questions

- PA Online Student Budget

- FAFSA Application

- CSS Profile Application

- How to Avoid Common Errors

- Student Billing Information

- Financial Literacy Information

- External Scholarships

- Financial Aid Team

- Certificate in Global Medicine

- Topics in Global Medicine and Health

- Global Health Seminar

- Summer Research Abroad

- Electives at Other Yale Graduate Schools

- About the Course

- South Africa

- Connecticut

- Dominican Republic

- Lectures, Series, & Conferences

- Community & Advocacy Opportunities

- Faculty Advisors & Mentors

- Global Health Team

- Services & Facilities

- Program & Faculty Development

- Education & Research

- Simulated Participants

- Year in Review

- Faculty & Staff

- Advisory Board

- HAVEN Free Clinic

- Neighborhood Health Project

- Humanities in Medicine

- Biomedical Ethics

- Yale Journal of Biology & Medicine

- University Engagement Opportunities

- Community Engagement Opportunities

- Competencies

- Guiding Principles

- Graduation Requirements

- Year 1 Curriculum

- Year 2 Curriculum

- Introduction to the Profession (iPro)

- Scientific Foundations

- Genes and Development

- Attacks and Defenses

- Homeostasis

- Energy and Metabolism

- Connection to the World

- Across the Lifespan

- Professional Responsibility

- Scientific Inquiry

- Populations & Methods

- Biochemistry

- Cell Biology

- Diagnostic Methods

- Domains of the Health Equity Thread

- Advisory Group

- Pharmacology

- Communications Skills

- Clinical Reasoning

- Palliative Care

- Physical Examination

- Point of Care Ultrasound

- Early Clinical Experiences

- Emergency Medicine

- Primary Care

- Internal Medicine

- Recommended Readings

- Online Learning

- Interprofessional Educational

- Anesthesiology

- Child Study Center

- Clinical Longitudinal Elective

- Definitions

- Dermatology

- Diagnostic Imaging

- Family Medicine

- Interventional Radiology

- Laboratory Medicine

- Neurosurgery

- Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences

- Ophthalmology and Visual Science

- Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation

- Therapeutic Radiology

- Elective Dates

- WEC Faculty

- Non-Clinical Electives

- Coaching Program

- Patient-Centered Language

- Race & Ethnicity

- Sex & Gender

- Full Glossary of Terms

- About The Inclusive Language Initiative

- Glossary Bibliography

- Curriculum Team

- Faculty Attestation

- Visiting Student Scholarship Program

- International Student FAQs

INFORMATION FOR

- Residents & Fellows

- Researchers

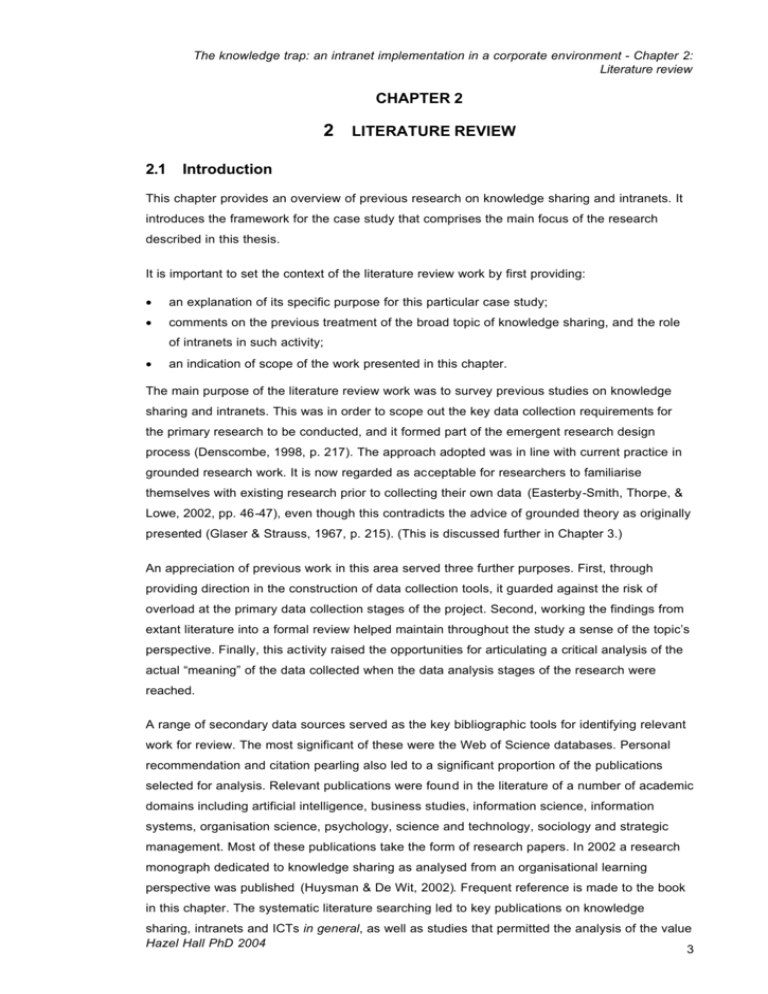

Formal MD Thesis Requirement

All students at Yale School of Medicine engage in research and are required to write an MD thesis during medical school. The only exceptions are students who have earned a PhD degree in the health sciences before matriculation and students enrolled in Yale’s MD/PhD program. The YSM MD Thesis is under the governance of the EPCC, which meets regularly to recommend rules, regulations, and deadlines.

Deadlines/Important Dates

Thesis approval process, thesis awards, required formatting and components of the md thesis, examples for reference section formatting, avoiding the risk of copyright violation and liability when submitting your md thesis, instructions for submitting a thesis to the yale medicine thesis digital library, thesis depositors declaration form, evaluations of advisor, student evaluation of thesis advisor.

- Yale School of Medicine Digital Thesis Depositor’s Declaration Form

- Thesis Deadline Extension Request Form

Thesis Deadlines for the 2023-2024 Academic Year

Md students:.

The Office of Student Research, in conjunction with the Dean’s Office, has established the following deadlines for theses submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in May 2024. The deadlines ensure that (1) students have sufficient time to complete their theses; (2) that there is sufficient time for rigorous departmental review and subsequent revision by students before final approval. These deadlines are strictly followed. Students are strongly encouraged to submit their theses well before the Class of 2024 Thesis Deadlines provided below. This timeliness will provide students, advisors, and sponsoring departments sufficient time for useful review and revision. It should be recognized by all concerned that the integrity of the thesis requirement and effective, rigorous review requires adherence to these deadlines. OSR will hold periodic “Thesis Check-in Sessions” via zoom for the Class of 2024 and will send periodic reminder emails with more detailed instructions as these deadlines approach.

| Deadline | Details |

|---|---|

| August 4, 2023* | Deadline for students to provide information regarding thesis title and advisor to OSR. |

| August 4, 2023 – December 22, 2023 | Student finishes research and writes thesis draft. |

| December 22, 2023 – January 2, 2024 | Recommended date by which student provides thesis draft to thesis mentor/advisor. Students should communicate with their thesis mentor/advisor to determine a mutually agreeable date. |

| December 22, 2023 – January 19, 2024 | Thesis mentor/advisor meets with student to review thesis. Student makes revisions and provides thesis mentor/advisor with edited version. The revised thesis then receives the Thesis mentor/advisor’s approval for submission. |

| January 19, 2024* | Thesis formally approved by thesis mentor/advisor and student submits to for review and approval. |

| January 19, 2024 – March 1, 2024 | Thesis undergoes Departmental review and assessment. Thesis Chair provides thesis approvals to the OSR, and student receives notification of thesis approval from Department. |

| March 1-22, 2024 | The OSR reviews theses, and assessments, and provides formal YSM approval. Student receives notification of thesis approval and feedback from the OSR. Information for ProQuest upload will also be provided at this time. |

| March 22-29, 2024* | Student makes any requested changes to thesis and submits the approved, final version of thesis to the library via ProQuest (all students meeting the above deadlines. ) |

*Students missing the August 4th, January 19th, and/or March 29th deadlines will be referred to the Progress Committee to ensure they receive adequate support to make progress towards this graduation requirement. Students missing the January 19th and/or March 29th deadlines will be ineligible for thesis prizes at graduation.

Extensions beyond the above thesis deadlines will be granted only for special circumstances and must have the approval of the student’s thesis mentor/advisor, academic advisor, and the Departmental Thesis Chairperson . Students seeking an extension for the January 19, 2024, deadline must submit a Thesis Deadline Extension Request Form to their Academic Advisor, and the Departmental Thesis Chair, for approval. Students missing the August 4th, January 19th, and/or March 29th deadlines will be referred to the Progress Committee to ensure they receive adequate support to make progress towards this graduation requirement. In the event of an extension, if granted, the following ABSOLUTE Class of 2024 Thesis Extension Deadlines will apply:

| Deadline | Details |

|---|---|

| March 22, 2024 | For those students receiving thesis extensions, this is the last date for the thesis to be formally approved by the thesis mentor/advisor and submitted to Departmental Thesis Chair for review and approval. |

| April 21, 2024 | For those students receiving thesis extensions, this is the last date for submission of an approved, final version of thesis to the library via ProQuest. |

*All late theses require an extension. The student must submit the Thesis Deadline Extension Request Form before January 19, 2024.

MD/MHS Students:

Consistent with degree requirements, MD/MHS students must present their thesis to their three-person committee prior to the January 19th deadline. Students are encouraged to start arranging the date of this committee meeting in the fall to avoid unanticipated delays.

| Deadline | Details |

|---|---|

| August 4, 2023* | Deadline for students to provide information regarding thesis title and advisor to the OSR via Medtrics. |

| August 4, 2023 – December 22, 2023 | Student finishes research and writes thesis draft. |

| December 22, 2023 | Recommended date by which student provides thesis draft to MHS advisor and committee members. Students should communicate with their committee to determine a mutually agreeable date. |

| December 22, 2023 – January 19, 2024 | Student presents thesis to MHS committee. Student makes revisions and provides committee with revisions. Committee formally approves thesis and completes assessment. |

| January 19, 2024* | Student submits thesis to the OSR. |

| January 19-March 1, 2024 | The OSR reviews theses, and assessments, and provides formal YSM approval of thesis. Student receives notification of thesis approval and any feedback from the OSR. Information for ProQuest upload will also be provided at this time. |

| March 1-29, 2024* | Student makes any requested changes to thesis and submits the approved, final version of thesis to the library via ProQuest (all students meeting the above deadlines). |

MD/PhD Students:

A different process applies to students in the MD/PhD program. For students enrolled in the combined MD/PhD Program, the dissertation submitted to and approved by the Graduate School will satisfy the MD thesis requirement. Therefore, MD/PhD students who have already defended their dissertation and received their PhD should provide this information to OSR via email as soon as possible.

To ensure compliance with YSM graduation deadlines, MD/PhD students in the class of 2024 who have not defended and submitted their dissertation to the Graduate School by the October 1, 2023, deadline will need to submit a copy of their dissertation directly to OSR via the MD/PhD Box Upload Link by March 15, 2024. OSR will convene a committee to review the dissertation, obtain feedback, and provide approval for graduation. Please note that MD/PhD students must also defend and submit their dissertation to the Graduate School no later than March 15, 2024, to meet the Graduate School spring degree deadline for conferral of the PhD degree. MD/PhD students who have not yet defended their dissertation should provide this information to OSR. If there are any questions about the process, please contact the MD/PhD Office.

Financial support is not provided for writing the thesis.

Thesis Preparation and Approval

Preparation for thesis submission begins in the summer of the fourth year with the OSR leadership. At this time, timeline and practices are distributed via email and reviewed with students in class meetings. Because thesis approval is a lengthy process involving three levels of review, students are encouraged to manage their time well and start writing their first draft early in the fall semester of their final year of medical school. A suggested timeline is provided below.

July : Thesis deadlines are distributed via email to all students in the graduating class and an informational session is held. Students should be on track to complete their thesis research by mid-fall. Any student anticipating a challenge in this regard should contact the OSR as soon as possible. All students expecting to graduate in May of a given year must, provide the OSR with information regarding their thesis title and mentor/advisor. Students will receive an email from the OSR containing a Medtrics link requesting this information. The OSR will contact all thesis mentors/advisors to confirm this role and to provide information and expectations regarding the thesis process.

August – December : Students should be finalizing research and writing their thesis draft. As the semester progresses, activities should shift from the data generation/analysis to the writing of the actual thesis. Students should do their best to complete the first draft of the thesis by mid-late December. Because students are also involved in the residency application and interview process, they are discouraged from starting new projects at this time.

December – January : This period is devoted to reviewing and editing of thesis draft that is ultimately approved by their thesis mentor/advisor and submitted by the student to the Thesis Chair of their sponsoring department. The YSM thesis mentor/advisor will be asked to complete a thesis assessment that evaluates the student’s mastery of YSM’s research-related educational objectives and provides formative summative feedback to the student.

January – March : The Departmental Thesis Chair coordinates thesis review by external reviewers. An “external reviewer” is defined as an individual who is not directly involved in the project. This individual may be a Yale faculty member internal or external to YSM or may hold a faculty appointment at an outside institution. This reviewer is required to complete a thesis assessment and provide formative summative feedback, as well as recommendations for any required changes, to the thesis. Departmental Thesis Chairs review assessments, notify students of departmental approval, and transmit these approvals to the OSR.

March : Theses and their associated assessments undergo school-level review by the OSR. Students receive YSM approval of their thesis along with summative feedback obtained during the review process. Students incorporate any required changes into their thesis and upload to the Yale Medicine Digital Thesis Library/Eli Scholar via the ProQuest platform (see below).

April : The OSR confirms that theses have been deposited into the Yale Medicine Digital Thesis Library and the registrar receives the names of students who have completed the thesis requirement.

The central role of the medical student thesis is to assess student’s performance on the YSM’s research-related educational objectives. As such, all students are expected to produce an excellent piece of scholarly work. In recognition of these achievements, the OSR has worked to develop an award process that celebrates the wonderful research being done by our students without creating a competitive atmosphere surrounding the thesis. Hence, thesis awards are based on competency-based assessments submitted by thesis mentors/advisors and reviewers during the approval process, and internal review of the final thesis that was deposited into the Yale Medicine Digital Thesis Library. Consistent with all other graduation prizes, YSM MD Thesis Awards will remain confidential until they are announced in the YSM Commencement Program on May 20, 2024. While some departments may elect to confer thesis “honors” based upon their own internal review, this recognition is distinct from YSM graduation prizes and is not under OSR’s purview.

Read about the required formatting and components for the thesis .

See helpful examples for reference section formatting.

Read about avoiding the risk of copyright violation and liability when submitting your MD Thesis.

Learn more about submitting a thesis to the Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library .

Learn more about the Thesis Depositors Declaration Form.

Learn more about evaluating your experience with your thesis advisor .

Apply for a Thesis Extension

Read about the required formatting and components for the thesis.

Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine

Learn more about the journal or submit a manuscript.

Melbourne Medical School

- Our Departments

- Medical Education

- Qualitative journeys

Writing a thesis

A thesis is a written report of your research, and generally contains the following chapters: introduction, methods, results, discussion and conclusion. It will also have a list of references and appendices. Check with your faculty/department/school for degree-specific thesis requirements. You may also find it helpful to look at published theses (in your department) to see how they are structured. (Internationally, the ‘thesis’ may be referred to as a ‘dissertation’).

- Gruba, P., & Zobel, J. (2014). How to write a better minor thesis . Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Publishing.

- Stoddart, K. (1991) Writing Sociologically: A Note on Teaching the Construction of a Qualitative Report. Teaching Sociology (2), 243-248.

- Mullins, G. and M. Kiley (2002). It’s a PhD, not a Nobel Prize: how experienced examiners assess research theses. Studies in Higher Education . 27(2): 369-386 .

- Thesis Bootcamp

- Shut Up and Write Sessions

- Study Skills workshops (including Word for Thesis and Introduction to NVivo workshops).

- Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences

- Baker Department of Cardiometabolic Health

- Clinical Pathology

- Critical Care

- General Practice and Primary Care

- Infectious Diseases

- Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Newborn Health

- Paediatrics

- Rural Health

- News & Events

- Medical Research Projects by Theme

- Department Research Overviews

- General Practice

- Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Graduate Research

- Medical Research Services

- Our Degrees

- Scholarships, Bursaries and Prizes

- Our Short Courses

- Current Student Resources

- Melbourne Medical Electives

- Welcome from the School Head

- Honorary Appointments

- MMS Staff Hub

- Current Students

Last updated 09/07/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Introduction to Research Methodology for Specialists and Trainees

- > How to Write a Medical Thesis

Book contents

- Introduction to Research Methodology for Specialists and Trainees

- Copyright page

- Contributors

- Chapter 1 Research During Specialist Medical Training

- Chapter 2 Time Management When Planning and Conducting Medical Research

- Chapter 3 Computer Skills Required for Medical Research

- Chapter 4 Computer Skills Required for Medical Research: Social Media

- Chapter 5 Finding and Using Information in Your Research

- Chapter 6 Critical Appraisal of the Medical Literature

- Chapter 7 Evidence-based Medicine and Translating Research into Practice

- Chapter 8 Clinical Audit for Quality Improvement

- Chapter 9 A Journey of Exploration

- Chapter 10 Randomised Clinical Trials

- Chapter 11 Animal Research and Alternatives

- Chapter 12 Genetic and Epigenetic Research

- Chapter 13 ‘Omic’ Research

- Chapter 14 Data Management in Medical Research

- Chapter 15 Statistics in Medical Research

- Chapter 16 Epidemiological Research

- Chapter 17 Informing Patients, Consent, Governance and Good Clinical Practice

- Chapter 18 Patient Involvement in Medical Research

- Chapter 19 Research in the National Health Service

- Chapter 20 Supervising Medical Research and Being Supervised

- Chapter 21 Funding Medical Research

- Chapter 22 The Purpose and Practice of Medical Research Meetings

- Chapter 23 How to Present a Medical Research Paper

- Chapter 24 How to Write a Medical Research Paper and Get It Accepted for Publication

- Chapter 25 How to Write a Medical Thesis

- Obstetrics and Gynaecology Supplement

- B Research in Fetal Medicine

- C Research in Maternal Medicine

- D Research in Benign Gynaecology

- E Research in Gynaecological Oncology

Chapter 25 - How to Write a Medical Thesis

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 August 2017

Access options

Save book to kindle.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- How to Write a Medical Thesis

- By Jennifer Byrom , David Lissauer

- Edited by P. M. Shaughn O'Brien , Fiona Broughton Pipkin , University of Nottingham

- Book: Introduction to Research Methodology for Specialists and Trainees

- Online publication: 04 August 2017

- Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781107585775.026

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

- [email protected]

- No.6/387, First Floor, Mogappair East, Chennai.

- GET A QUOTE

Service Beyond Hopes!

Writing a medical thesis: tips for post-graduate students.

What is a medical thesis?

A medical thesis is the written work resulting from an original research in the field of Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, and other health and life sciences. It is submitted by the students in order to obtain a higher degree from the University.

However, keep this in mind! The purpose of submitting a medical thesis is not limited to the achievement of a doctoral or post-graduate degree. It is a medium to organize the scientific knowledge in a way to make further progress in the field.

That’s the reason why the experts in medical thesis writing stress on the importance of choosing the right topic for your thesis. You must be able to address a genuine problem or series of problems through your medical thesis. Choose a topic that aligns with your interest and where you can offer a fresh perspective through your research study.

Writing your medical thesis

After choosing the topic for your research study, collaborate with your supervisor to design your research study and its goal. Collect all the information and data pertaining to your research before proceeding with your clinical trials.

Now, you are ready with your research data and clinical findings. You just need to pen down your findings in your medical thesis.

That sounds easy, isn’t it?

In reality, it’s not so. But, you need not worry! Writing a medical thesis becomes easy and fun if you follow the given steps with competence:

1.Outline the structure of medical thesis

Prepare an outline of the thesis in accordance with the following sections:

- Introduction: Why did you start your study?

- Methods Used

- Results of the study

- Discussion of results

List the major sections and chapters in each. Do a section at a time. Assemble all the figures and tables and organise them into a logical sequence.

2.Writing a title of the thesis

The title reflects the content of your thesis. For writing a perfect thesis title:

- Be concise and accurate. The title must neither be too long nor too short

- Avoid unnecessary words and phrases like “Observation of” or “A study of”

- Do not use abbreviations

- Avoid grammatical mistakes

3.Writing an Introduction

The purpose of writing an Introduction is to provide the reader with sufficient background information on the topic and help him understand and evaluate the results of the present study, without needing to refer to the previous publications on the topic.

- Give this background information in brief in the first paragraph

- Include the importance of the problem and what is unknown about it in the second paragraph

- State the purpose, hypothesis, and objective of your study in the last paragraph

Cite the research papers written on your research topic

- Include unnecessary information other than the problem being examined

- Include the research design, data or conclusion of your study

- Cite well-known facts

- Include information found in any textbook in the field

4.Writing the section of “Methods Used”

This section must be so written that the reader is able to repeat the study and validate its findings.

Write a detailed exposition about the participants in the study, what materials you used and how you analyzed the results

- Give references but no description for established methods

- Give a brief description and references for published but lesser known methods

- Give detailed description of new methods citing the reasons for using them and any limitations if present

- Include background information and results of the study

- Refer to animals and patients as material

- Use trade name of the drugs; instead, use their generic names

- Use non-technical language for technical statistical terms

5.Writing your Results

Keep in mind the objective of your research while writing the “Results” section. The findings of the research can be documented in the form of:

- Illustrative graphs

Use text to summarize small amounts of data. Do not over-use tables, figures, and graphs in your paper. Moreover, do not repeat information presented in the table or figure in the text format. Text must be a summary or highlight of the information presented in tables or figures.

6.Discussing your Results

Good medical theses have a targeted discussion keeping it focused on the topic of the research. Include:

- Statement of the principal findings. Make it clear to show that your thesis includes new information

- Strengths and weaknesses of your study

- Strengths and weaknesses in relation to the other studies

- A take-home message from your study for clinicians and policymakers

- Any questions that are left unanswered in your study to propose new research

How to conclude your medical thesis?

The conclusion of your research study must comprise of:

- The most important statement or remark from the observations

- Summary of new observations, interpretations, and insights from the present study

- How your study fills the knowledge gap in its respected field?

- The broader implications of your work

- How can your work be improved by future research?

However, avoid any statement that does not support your data.

With these tips, write your thesis like a pro and don’t let it delay your doctoral award!

11 Comments

Somebody essentially lend a hand to make critically articles I’d state. This is the very first time I frequented your web page and thus far? I surprised with the research you made to create this actual submit incredible. Magnificent task!

Also visit my homepage: Bio Core CBD Reviews

I as well believe thence, perfectly written post!

Have a look at my web site – Green Life CBD Reviews

Good post however , I was wondering if you could write a litte more on this subject? I’d be very thankful if you could elaborate a little bit further. Appreciate it!

Hey, I think your blog might be having browser compatibility issues.

When I look at your blog in Firefox, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, awesome blog!

Wow that was unusual. I just wrote an incredibly long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyhow, just wanted to say excellent blog!

Feel free to surf to my homepage – Fiwi Booster

I’m really impressed with your writing skills as well as with the layout on your weblog. Is this a paid theme or did you customize it yourself? Anyway keep up the excellent quality writing, it is rare to see a great blog like this one today.

Thankfulness to my father who told me concerning this webpage, this blog is really awesome.

This is a topic which is near to my heart… Best wishes! Exactly where are your contact details though?

Excellent pieces. Keep posting such kind of info on your blog. Im really impressed by it. Hello there, You have done an incredible job. I will certainly digg it and individually suggest to my friends. I am sure they will be benefited from this site.

I recently tried CBD gummies recompense the first all together and they exceeded my expectations. The taste was thrilling, and full spectrum cbd oil helped me unwind and relax. My concern noticeably decreased, and I felt a perceive of inclusive well-being. These gummies are any more a standard in my self-care routine. Enthusiastically recommend in favour of a ordinary and soft experience.

Thank you for any other magnificent post. Where else may anybody get that type of info in such an ideal means of writing? I’ve a presentation next week, and I’m at the look for such info.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Dissertations & Theses

- Collections

EliScholar > Medicine > Medicine Thesis Digital Library

Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library

Starting with the Yale School of Medicine (YSM) graduating class of 2002, the Cushing/Whitney Medical Library and YSM Office of Student Research have collaborated on the Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library (YMTDL) project, publishing the digitized full text of medical student theses on the web as a valuable byproduct of Yale student research efforts. The digital thesis deposit has been a graduation requirement since 2006. Starting in 2012, alumni of the Yale School of Medicine were invited to participate in the YMTDL project by granting scanning and hosting permission to the Cushing/Whitney Medical Library, which digitized the Library’s print copy of their thesis or dissertation. A grant from the Arcadia Fund in 2017 provided the means for digitizing over 1,000 additional theses. IF YOU ARE A MEMBER OF THE YALE COMMUNITY AND NEED ACCESS TO A THESIS RESTRICTED TO THE YALE NETWORK, PLEASE MAKE SURE YOUR VPN (VIRTUAL PRIVATE NETWORK) IS ON.

Theses/Dissertations from 2024 2024

Refractory Neurogenic Cough Management: The Non-Inferiority Of Soluble Steroids To Particulate Suspensions For Superior Laryngeal Nerve Blocks , Hisham Abdou

Percutaneous Management Of Pelvic Fluid Collections: A 10-Year Series , Chidumebi Alim

Behavioral Outcomes In Patients With Metopic Craniosynostosis: Relationship With Radiographic Severity , Mariana Almeida

Ventilator Weaning Parameters Revisited: A Traditional Analysis And A Test Of Artificial Intelligence To Predict Successful Extubation , John James Andrews

Developing Precision Genome Editors: Peptide Nucleic Acids Modulate Crispr Cas9 To Treat Autosomal Dominant Disease , Jem Atillasoy

Radiology Education For U.s. Medical Students In 2024: A State-Of-The-Art Analysis , Ryan Bahar

Out-Of-Pocket Spending On Medications For Diabetes In The United States , Baylee Bakkila

Imaging Markers Of Microstructural Development In Neonatal Brains And The Impact Of Postnatal Pathologies , Pratheek Sai Bobba

A Needs Assessment For Rural Health Education In United States Medical Schools , Kailey Carlson

Racial Disparities In Behavioral Crisis Care: Investigating Restraint Patterns In Emergency Departments , Erika Chang-Sing

Social Determinants Of Health & Barriers To Care In Diabetic Retinopathy Patients Lost To Follow-Up , Thomas Chang

Association Between Fine Particulate Matter And Eczema: A Cross-Sectional Study Of The All Of Us Research Program And The Center For Air, Climate, And Energy Solutions , Gloria Chen

Predictors Of Adverse Outcomes Following Surgical Intervention For Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy , Samuel Craft

Genetic Contributions To Thoracic Aortic Disease , Ellelan Arega Degife

Actigraphy And Symptom Changes With A Social Rhythm Intervention In Young Persons With Mood Disorders , Gabriela De Queiroz Campos

Incidence Of Pathologic Nodal Disease In Clinically Node Negative, Microinvasive/t1a Breast Cancers , Pranammya Dey

Spinal Infections: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Prevention, And Management , Meera Madhav Dhodapkar

Childen's Reentry To School After Psychiatric Hospitalization: A Qualitative Study , Madeline Digiovanni

Bringing Large Language Models To Ophthalmology: Domain-Specific Ontologies And Evidence Attribution , Aidan Gilson

Surgical Personalities: A Cultural History Of Early 20th Century American Plastic Surgery , Joshua Zev Glahn

Implications Of Acute Brain Injury Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement , Daniel Grubman

Latent Health Status Trajectory Modelling In Patients With Symptomatic Peripheral Artery Disease , Scott Grubman

The Human Claustrum Tracks Slow Waves During Sleep , Brett Gu

Patient Perceptions Of Machine Learning-Enabled Digital Mental Health , Clara Zhang Guo

Variables Affecting The 90-Day Overall Reimbursement Of Four Common Orthopaedic Procedures , Scott Joseph Halperin

The Evolving Landscape Of Academic Plastic Surgery: Understanding And Shaping Future Directions In Diversity, Equity, And Inclusion , Sacha C. Hauc

Association Of Vigorous Physical Activity With Psychiatric Disorders And Participation In Treatment , John L. Havlik

Long-Term Natural History Of Ush2a-Retinopathy , Michael Heyang

Clinical Decision Support For Emergency Department-Initiated Buprenorphine For Opioid Use Disorder , Wesley Holland

Applying Deep Learning To Derive Noninvasive Imaging Biomarkers For High-Risk Phenotypes Of Prostate Cancer , Sajid Hossain

The Hardships Of Healthcare Among People With Lived Experiences Of Homelessness In New Haven, Ct , Brandon James Hudik

Outcomes Of Peripheral Vascular Interventions In Patients Treated With Factor Xa Inhibitors , Joshua Joseph Huttler

Janus Kinase Inhibition In Granuloma Annulare: Two Single-Arm, Open-Label Clinical Trials , Erica Hwang

Medicaid Coverage For Undocumented Children In Connecticut: A Political History , Chinye Ijeli

Population Attributable Fraction Of Reproductive Factors In Triple Negative Breast Cancer By Race , Rachel Jaber Chehayeb

Evaluation Of Gastroesophageal Reflux And Hiatal Hernia As Risk Factors For Lobectomy Complications , Michael Kaminski

Health-Related Social Needs Before And After Critical Illness Among Medicare Beneficiaries , Tamar A. Kaminski

Effects Of Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair On Cardiac Function At Rest , Nabeel Kassam

Conditioned Hallucinations By Illness Stage In Individuals With First Episode Schizophrenia, Chronic Schizophrenia, And Clinical High Risk For Psychosis , Adam King

The Choroid Plexus Links Innate Immunity To Dysregulation Of Csf Homeostasis In Diverse Forms Of Hydrocephalus , Emre Kiziltug

Health Status Changes After Stenting For Stroke Prevention In Carotid Artery Stenosis , Jonathan Kluger

Rare And Undiagnosed Liver Diseases: New Insights From Genomic And Single Cell Transcriptomic Analyses , Chigoziri Konkwo

“Teen Health” Empowers Informed Contraception Decision-Making In Adolescents And Young Adults , Christina Lepore

Barriers To Mental Health Care In Us Military Veterans , Connor Lewis

Barriers To Methadone For Hiv Prevention Among People Who Inject Drugs In Kazakhstan , Amanda Rachel Liberman

Unheard Voices: The Burden Of Ischemia With No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease In Women , Marah Maayah

Partial And Total Tonsillectomy For Pediatric Sleep-Disordered Breathing: The Role Of The Cas-15 , Jacob Garn Mabey

Association Between Insurance, Access To Care, And Outcomes For Patients With Uveal Melanoma In The United States , Victoria Anne Marks

Urinary Vegf And Cell-Free Dna As Non-Invasive Biomarkers For Diabetic Retinopathy Screening , Mitchelle Matesva

Pain Management In Facial Trauma: A Narrative Review , Hunter Mccurdy

Meningioma Relational Database Curation Using A Pacs-Integrated Tool For Collection Of Clinical And Imaging Features , Ryan Mclean

Colonoscopy Withdrawal Time And Dysplasia Detection In Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease , Chandler Julianne Mcmillan

Cerebral Arachnoid Cysts Are Radiographic Harbingers Of Epigenetics Defects In Neurodevelopment , Kedous Mekbib

Regulation And Payment Of New Medical Technologies , Osman Waseem Moneer

Permanent Pacemaker Implantation After Tricuspid Valve Repair Surgery , Alyssa Morrison

Non-Invasive Epidermal Proteome-Based Subclassification Of Psoriasis And Eczema And Identification Of Treatment Relevant Biomarkers , Michael Murphy

Ballistic And Explosive Orthopaedic Trauma Epidemiology And Outcomes In A Global Population , Jamieson M. O'marr

Dermatologic Infectious Complications And Mimickers In Cancer Patients On Oncologic Therapy , Jolanta Pach

Distressed Community Index In Patients Undergoing Carotid Endarterectomy In Medicare-Linked Vqi Registry , Carmen Pajarillo

Preoperative Psychosocial Risk Burden Among Patients Undergoing Major Thoracic And Abdominal Surgery , Emily Park

Volumetric Assessment Of Imaging Response In The Pnoc Pediatric Glioma Clinical Trials , Divya Ramakrishnan

Racial And Sex Disparities In Adult Reconstructive Airway Surgery Outcomes: An Acs Nsqip Analysis , Tagan Rohrbaugh

A School-Based Study Of The Prevalence Of Rheumatic Heart Disease In Bali, Indonesia , Alysha Rose

Outcomes Following Hypofractionated Radiotherapy For Patients With Thoracic Tumors In Predominantly Central Locations , Alexander Sasse

Healthcare Expenditure On Atrial Fibrillation In The United States: The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey 2016-2021 , Claudia See

A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Of Oropharyngeal Cancer Post-Treatment Surveillance Practices , Rema Shah

Machine Learning And Risk Prediction Tools In Neurosurgery: A Rapid Review , Josiah Sherman

Maternal And Donor Human Milk Support Robust Intestinal Epithelial Growth And Differentiation In A Fetal Intestinal Organoid Model , Lauren Smith

Constructing A Fetal Human Liver Atlas: Insights Into Liver Development , Zihan Su

Somatic Mutations In Aging, Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria, And Myeloid Neoplasms , Tho Tran

Illness Perception And The Impact Of A Definitive Diagnosis On Women With Ischemia And No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Qualitative Study , Leslie Yingzhijie Tseng

Advances In Keratin 17 As A Cancer Biomarker: A Systematic Review , Robert Tseng

Regionalization Strategy To Optimize Inpatient Bed Utilization And Reduce Emergency Department Crowding , Ragini Luthra Vaidya

Survival Outcomes In T3 Laryngeal Cancer Based On Staging Features At Diagnosis , Vickie Jiaying Wang

Analysis Of Revertant Mosaicism And Cellular Competition In Ichthyosis With Confetti , Diana Yanez

A Hero's Journey: Experiences Using A Therapeutic Comicbook In A Children’s Psychiatric Inpatient Unit , Idil Yazgan

Prevalence Of Metabolic Comorbidities And Viral Infections In Monoclonal Gammopathy , Mansen Yu

Automated Detection Of Recurrent Gastrointestinal Bleeding Using Large Language Models , Neil Zheng

Vascular Risk Factor Treatment And Control For Stroke Prevention , Tianna Zhou

Theses/Dissertations from 2023 2023

Radiomics: A Methodological Guide And Its Applications To Acute Ischemic Stroke , Emily Avery

Characterization Of Cutaneous Immune-Related Adverse Events Due To Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors , Annika Belzer

An Investigation Of Novel Point Of Care 1-Tesla Mri Of Infants’ Brains In The Neonatal Icu , Elisa Rachel Berson

Understanding Perceptions Of New-Onset Type 1 Diabetes Education In A Pediatric Tertiary Care Center , Gabriel BetancurVelez

Effectiveness Of Acitretin For Skin Cancer Prevention In Immunosuppressed And Non-Immunosuppressed Patients , Shaman Bhullar

Adherence To Tumor Board Recommendations In Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma , Yueming Cao

Clinical Trials Related To The Spine & Shoulder/elbow: Rates, Predictors, & Reasons For Termination , Dennis Louis Caruana

Improving Delivery Of Immunomodulator Mpla With Biodegradable Nanoparticles , Jungsoo Chang

Sex Differences In Patients With Deep Vein Thrombosis , Shin Mei Chan

Incorporating Genomic Analysis In The Clinical Practice Of Hepatology , David Hun Chung

Emergency Medicine Resident Perceptions Of A Medical Wilderness Adventure Race (medwar) , Lake Crawford

Surgical Outcomes Following Posterior Spinal Fusion For Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis , Wyatt Benajmin David

Representing Cells As Sentences Enables Natural Language Processing For Single Cell Transcriptomics , Rahul M. Dhodapkar

Life Vs. Liberty And The Pursuit Of Happiness: Short-Term Involuntary Commitment Laws In All 50 US States , Sofia Dibich

Healthcare Disparities In Preoperative Risk Management For Total Joint Arthroplasty , Chloe Connolly Dlott

Toll-Like Receptors 2/4 Directly Co-Stimulate Arginase-1 Induction Critical For Macrophage-Mediated Renal Tubule Regeneration , Natnael Beyene Doilicho

Associations Of Atopic Dermatitis With Neuropsychiatric Comorbidities , Ryan Fan

International Academic Partnerships In Orthopaedic Surgery , Michael Jesse Flores

Young Adults With Adhd And Their Involvement In Online Communities: A Qualitative Study , Callie Marie Ginapp

Becoming A Doctor, Becoming A Monster: Medical Socialization And Desensitization In Nazi Germany And 21st Century USA , SimoneElise Stern Hasselmo

Comparative Efficacy Of Pharmacological Interventions For Borderline Personality Disorder: A Network Meta-Analysis , Olivia Dixon Herrington

Page 1 of 32

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Disciplines

- Researcher Profiles

- Author Help

Copyright, Publishing and Open Access

- Terms & Conditions

- Open Access at Yale

- Yale University Library

- Yale Law School Repository

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

What is a thesis | A Complete Guide with Examples

Table of Contents

A thesis is a comprehensive academic paper based on your original research that presents new findings, arguments, and ideas of your study. It’s typically submitted at the end of your master’s degree or as a capstone of your bachelor’s degree.

However, writing a thesis can be laborious, especially for beginners. From the initial challenge of pinpointing a compelling research topic to organizing and presenting findings, the process is filled with potential pitfalls.

Therefore, to help you, this guide talks about what is a thesis. Additionally, it offers revelations and methodologies to transform it from an overwhelming task to a manageable and rewarding academic milestone.

What is a thesis?

A thesis is an in-depth research study that identifies a particular topic of inquiry and presents a clear argument or perspective about that topic using evidence and logic.

Writing a thesis showcases your ability of critical thinking, gathering evidence, and making a compelling argument. Integral to these competencies is thorough research, which not only fortifies your propositions but also confers credibility to your entire study.

Furthermore, there's another phenomenon you might often confuse with the thesis: the ' working thesis .' However, they aren't similar and shouldn't be used interchangeably.

A working thesis, often referred to as a preliminary or tentative thesis, is an initial version of your thesis statement. It serves as a draft or a starting point that guides your research in its early stages.

As you research more and gather more evidence, your initial thesis (aka working thesis) might change. It's like a starting point that can be adjusted as you learn more. It's normal for your main topic to change a few times before you finalize it.

While a thesis identifies and provides an overarching argument, the key to clearly communicating the central point of that argument lies in writing a strong thesis statement.

What is a thesis statement?

A strong thesis statement (aka thesis sentence) is a concise summary of the main argument or claim of the paper. It serves as a critical anchor in any academic work, succinctly encapsulating the primary argument or main idea of the entire paper.

Typically found within the introductory section, a strong thesis statement acts as a roadmap of your thesis, directing readers through your arguments and findings. By delineating the core focus of your investigation, it offers readers an immediate understanding of the context and the gravity of your study.

Furthermore, an effectively crafted thesis statement can set forth the boundaries of your research, helping readers anticipate the specific areas of inquiry you are addressing.

Different types of thesis statements

A good thesis statement is clear, specific, and arguable. Therefore, it is necessary for you to choose the right type of thesis statement for your academic papers.

Thesis statements can be classified based on their purpose and structure. Here are the primary types of thesis statements:

Argumentative (or Persuasive) thesis statement

Purpose : To convince the reader of a particular stance or point of view by presenting evidence and formulating a compelling argument.

Example : Reducing plastic use in daily life is essential for environmental health.

Analytical thesis statement

Purpose : To break down an idea or issue into its components and evaluate it.

Example : By examining the long-term effects, social implications, and economic impact of climate change, it becomes evident that immediate global action is necessary.

Expository (or Descriptive) thesis statement

Purpose : To explain a topic or subject to the reader.

Example : The Great Depression, spanning the 1930s, was a severe worldwide economic downturn triggered by a stock market crash, bank failures, and reduced consumer spending.

Cause and effect thesis statement

Purpose : To demonstrate a cause and its resulting effect.

Example : Overuse of smartphones can lead to impaired sleep patterns, reduced face-to-face social interactions, and increased levels of anxiety.

Compare and contrast thesis statement

Purpose : To highlight similarities and differences between two subjects.

Example : "While both novels '1984' and 'Brave New World' delve into dystopian futures, they differ in their portrayal of individual freedom, societal control, and the role of technology."

When you write a thesis statement , it's important to ensure clarity and precision, so the reader immediately understands the central focus of your work.

What is the difference between a thesis and a thesis statement?

While both terms are frequently used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings.

A thesis refers to the entire research document, encompassing all its chapters and sections. In contrast, a thesis statement is a brief assertion that encapsulates the central argument of the research.

Here’s an in-depth differentiation table of a thesis and a thesis statement.

Aspect | Thesis | Thesis Statement |

Definition | An extensive document presenting the author's research and findings, typically for a degree or professional qualification. | A concise sentence or two in an essay or research paper that outlines the main idea or argument. |

Position | It’s the entire document on its own. | Typically found at the end of the introduction of an essay, research paper, or thesis. |

Components | Introduction, methodology, results, conclusions, and bibliography or references. | Doesn't include any specific components |

Purpose | Provides detailed research, presents findings, and contributes to a field of study. | To guide the reader about the main point or argument of the paper or essay. |

Now, to craft a compelling thesis, it's crucial to adhere to a specific structure. Let’s break down these essential components that make up a thesis structure

15 components of a thesis structure

Navigating a thesis can be daunting. However, understanding its structure can make the process more manageable.

Here are the key components or different sections of a thesis structure:

Your thesis begins with the title page. It's not just a formality but the gateway to your research.

Here, you'll prominently display the necessary information about you (the author) and your institutional details.

- Title of your thesis

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date

- Your Supervisor's name (in some cases)

- Your Department or faculty (in some cases)

- Your University's logo (in some cases)

- Your Student ID (in some cases)

In a concise manner, you'll have to summarize the critical aspects of your research in typically no more than 200-300 words.

This includes the problem statement, methodology, key findings, and conclusions. For many, the abstract will determine if they delve deeper into your work, so ensure it's clear and compelling.

Acknowledgments

Research is rarely a solitary endeavor. In the acknowledgments section, you have the chance to express gratitude to those who've supported your journey.

This might include advisors, peers, institutions, or even personal sources of inspiration and support. It's a personal touch, reflecting the humanity behind the academic rigor.

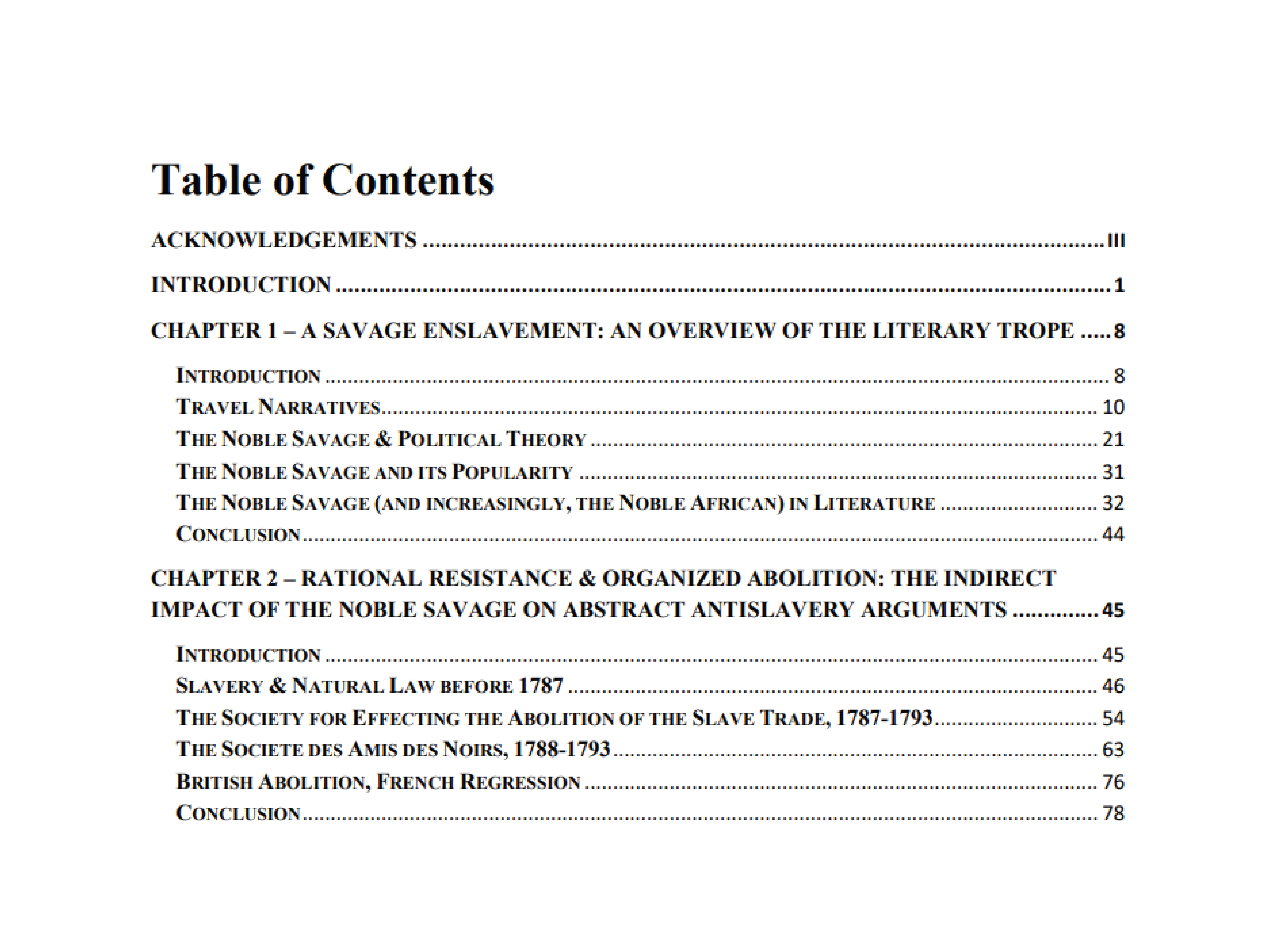

Table of contents

A roadmap for your readers, the table of contents lists the chapters, sections, and subsections of your thesis.

By providing page numbers, you allow readers to navigate your work easily, jumping to sections that pique their interest.

List of figures and tables

Research often involves data, and presenting this data visually can enhance understanding. This section provides an organized listing of all figures and tables in your thesis.

It's a visual index, ensuring that readers can quickly locate and reference your graphical data.

Introduction

Here's where you introduce your research topic, articulate the research question or objective, and outline the significance of your study.

- Present the research topic : Clearly articulate the central theme or subject of your research.

- Background information : Ground your research topic, providing any necessary context or background information your readers might need to understand the significance of your study.

- Define the scope : Clearly delineate the boundaries of your research, indicating what will and won't be covered.

- Literature review : Introduce any relevant existing research on your topic, situating your work within the broader academic conversation and highlighting where your research fits in.

- State the research Question(s) or objective(s) : Clearly articulate the primary questions or objectives your research aims to address.

- Outline the study's structure : Give a brief overview of how the subsequent sections of your work will unfold, guiding your readers through the journey ahead.

The introduction should captivate your readers, making them eager to delve deeper into your research journey.

Literature review section

Your study correlates with existing research. Therefore, in the literature review section, you'll engage in a dialogue with existing knowledge, highlighting relevant studies, theories, and findings.

It's here that you identify gaps in the current knowledge, positioning your research as a bridge to new insights.

To streamline this process, consider leveraging AI tools. For example, the SciSpace literature review tool enables you to efficiently explore and delve into research papers, simplifying your literature review journey.

Methodology

In the research methodology section, you’ll detail the tools, techniques, and processes you employed to gather and analyze data. This section will inform the readers about how you approached your research questions and ensures the reproducibility of your study.

Here's a breakdown of what it should encompass:

- Research Design : Describe the overall structure and approach of your research. Are you conducting a qualitative study with in-depth interviews? Or is it a quantitative study using statistical analysis? Perhaps it's a mixed-methods approach?

- Data Collection : Detail the methods you used to gather data. This could include surveys, experiments, observations, interviews, archival research, etc. Mention where you sourced your data, the duration of data collection, and any tools or instruments used.

- Sampling : If applicable, explain how you selected participants or data sources for your study. Discuss the size of your sample and the rationale behind choosing it.

- Data Analysis : Describe the techniques and tools you used to process and analyze the data. This could range from statistical tests in quantitative research to thematic analysis in qualitative research.

- Validity and Reliability : Address the steps you took to ensure the validity and reliability of your findings to ensure that your results are both accurate and consistent.

- Ethical Considerations : Highlight any ethical issues related to your research and the measures you took to address them, including — informed consent, confidentiality, and data storage and protection measures.

Moreover, different research questions necessitate different types of methodologies. For instance:

- Experimental methodology : Often used in sciences, this involves a controlled experiment to discern causality.

- Qualitative methodology : Employed when exploring patterns or phenomena without numerical data. Methods can include interviews, focus groups, or content analysis.

- Quantitative methodology : Concerned with measurable data and often involves statistical analysis. Surveys and structured observations are common tools here.

- Mixed methods : As the name implies, this combines both qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

The Methodology section isn’t just about detailing the methods but also justifying why they were chosen. The appropriateness of the methods in addressing your research question can significantly impact the credibility of your findings.

Results (or Findings)

This section presents the outcomes of your research. It's crucial to note that the nature of your results may vary; they could be quantitative, qualitative, or a mix of both.

Quantitative results often present statistical data, showcasing measurable outcomes, and they benefit from tables, graphs, and figures to depict these data points.

Qualitative results , on the other hand, might delve into patterns, themes, or narratives derived from non-numerical data, such as interviews or observations.

Regardless of the nature of your results, clarity is essential. This section is purely about presenting the data without offering interpretations — that comes later in the discussion.

In the discussion section, the raw data transforms into valuable insights.

Start by revisiting your research question and contrast it with the findings. How do your results expand, constrict, or challenge current academic conversations?

Dive into the intricacies of the data, guiding the reader through its implications. Detail potential limitations transparently, signaling your awareness of the research's boundaries. This is where your academic voice should be resonant and confident.

Practical implications (Recommendation) section

Based on the insights derived from your research, this section provides actionable suggestions or proposed solutions.

Whether aimed at industry professionals or the general public, recommendations translate your academic findings into potential real-world actions. They help readers understand the practical implications of your work and how it can be applied to effect change or improvement in a given field.

When crafting recommendations, it's essential to ensure they're feasible and rooted in the evidence provided by your research. They shouldn't merely be aspirational but should offer a clear path forward, grounded in your findings.

The conclusion provides closure to your research narrative.

It's not merely a recap but a synthesis of your main findings and their broader implications. Reconnect with the research questions or hypotheses posited at the beginning, offering clear answers based on your findings.

Reflect on the broader contributions of your study, considering its impact on the academic community and potential real-world applications.

Lastly, the conclusion should leave your readers with a clear understanding of the value and impact of your study.

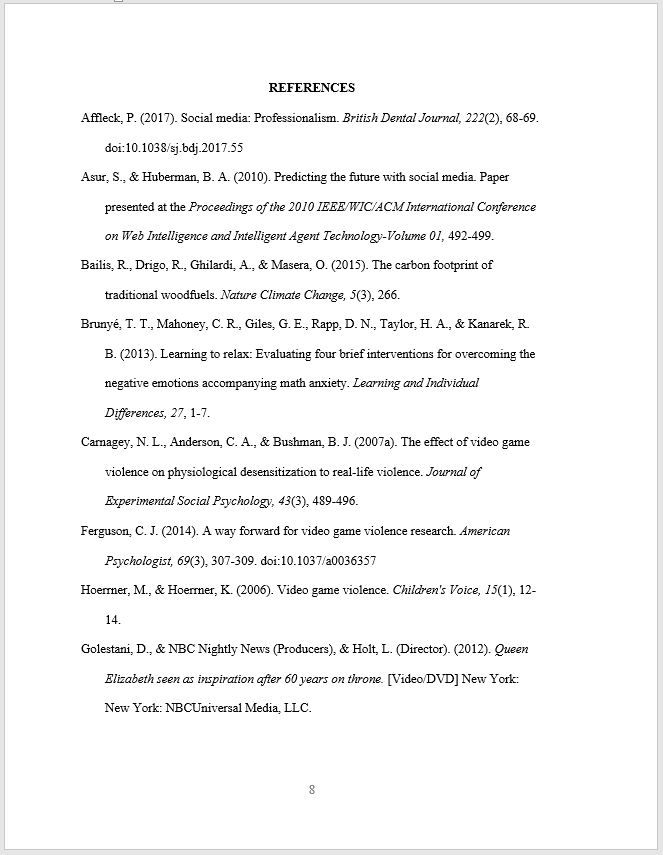

References (or Bibliography)

Every theory you've expounded upon, every data point you've cited, and every methodological precedent you've followed finds its acknowledgment here.

In references, it's crucial to ensure meticulous consistency in formatting, mirroring the specific guidelines of the chosen citation style .

Proper referencing helps to avoid plagiarism , gives credit to original ideas, and allows readers to explore topics of interest. Moreover, it situates your work within the continuum of academic knowledge.

To properly cite the sources used in the study, you can rely on online citation generator tools to generate accurate citations!

Here’s more on how you can cite your sources.

Often, the depth of research produces a wealth of material that, while crucial, can make the core content of the thesis cumbersome. The appendix is where you mention extra information that supports your research but isn't central to the main text.

Whether it's raw datasets, detailed procedural methodologies, extended case studies, or any other ancillary material, the appendices ensure that these elements are archived for reference without breaking the main narrative's flow.

For thorough researchers and readers keen on meticulous details, the appendices provide a treasure trove of insights.

Glossary (optional)

In academics, specialized terminologies, and jargon are inevitable. However, not every reader is versed in every term.

The glossary, while optional, is a critical tool for accessibility. It's a bridge ensuring that even readers from outside the discipline can access, understand, and appreciate your work.

By defining complex terms and providing context, you're inviting a wider audience to engage with your research, enhancing its reach and impact.

Remember, while these components provide a structured framework, the essence of your thesis lies in the originality of your ideas, the rigor of your research, and the clarity of your presentation.

As you craft each section, keep your readers in mind, ensuring that your passion and dedication shine through every page.

Thesis examples

To further elucidate the concept of a thesis, here are illustrative examples from various fields:

Example 1 (History): Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the ‘Noble Savage’ on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807 by Suchait Kahlon.

Example 2 (Climate Dynamics): Influence of external forcings on abrupt millennial-scale climate changes: a statistical modelling study by Takahito Mitsui · Michel Crucifix

Checklist for your thesis evaluation

Evaluating your thesis ensures that your research meets the standards of academia. Here's an elaborate checklist to guide you through this critical process.

Content and structure

- Is the thesis statement clear, concise, and debatable?

- Does the introduction provide sufficient background and context?

- Is the literature review comprehensive, relevant, and well-organized?

- Does the methodology section clearly describe and justify the research methods?

- Are the results/findings presented clearly and logically?

- Does the discussion interpret the results in light of the research question and existing literature?

- Is the conclusion summarizing the research and suggesting future directions or implications?

Clarity and coherence

- Is the writing clear and free of jargon?

- Are ideas and sections logically connected and flowing?

- Is there a clear narrative or argument throughout the thesis?

Research quality

- Is the research question significant and relevant?

- Are the research methods appropriate for the question?

- Is the sample size (if applicable) adequate?

- Are the data analysis techniques appropriate and correctly applied?

- Are potential biases or limitations addressed?

Originality and significance

- Does the thesis contribute new knowledge or insights to the field?

- Is the research grounded in existing literature while offering fresh perspectives?

Formatting and presentation

- Is the thesis formatted according to institutional guidelines?

- Are figures, tables, and charts clear, labeled, and referenced in the text?

- Is the bibliography or reference list complete and consistently formatted?

- Are appendices relevant and appropriately referenced in the main text?

Grammar and language

- Is the thesis free of grammatical and spelling errors?

- Is the language professional, consistent, and appropriate for an academic audience?

- Are quotations and paraphrased material correctly cited?

Feedback and revision

- Have you sought feedback from peers, advisors, or experts in the field?

- Have you addressed the feedback and made the necessary revisions?

Overall assessment

- Does the thesis as a whole feel cohesive and comprehensive?

- Would the thesis be understandable and valuable to someone in your field?

Ensure to use this checklist to leave no ground for doubt or missed information in your thesis.

After writing your thesis, the next step is to discuss and defend your findings verbally in front of a knowledgeable panel. You’ve to be well prepared as your professors may grade your presentation abilities.

Preparing your thesis defense

A thesis defense, also known as "defending the thesis," is the culmination of a scholar's research journey. It's the final frontier, where you’ll present their findings and face scrutiny from a panel of experts.

Typically, the defense involves a public presentation where you’ll have to outline your study, followed by a question-and-answer session with a committee of experts. This committee assesses the validity, originality, and significance of the research.

The defense serves as a rite of passage for scholars. It's an opportunity to showcase expertise, address criticisms, and refine arguments. A successful defense not only validates the research but also establishes your authority as a researcher in your field.

Here’s how you can effectively prepare for your thesis defense .

Now, having touched upon the process of defending a thesis, it's worth noting that scholarly work can take various forms, depending on academic and regional practices.

One such form, often paralleled with the thesis, is the 'dissertation.' But what differentiates the two?

Dissertation vs. Thesis

Often used interchangeably in casual discourse, they refer to distinct research projects undertaken at different levels of higher education.

To the uninitiated, understanding their meaning might be elusive. So, let's demystify these terms and delve into their core differences.

Here's a table differentiating between the two.

Aspect | Thesis | Dissertation |

Purpose | Often for a master's degree, showcasing a grasp of existing research | Primarily for a doctoral degree, contributing new knowledge to the field |

Length | 100 pages, focusing on a specific topic or question. | 400-500 pages, involving deep research and comprehensive findings |

Research Depth | Builds upon existing research | Involves original and groundbreaking research |

Advisor's Role | Guides the research process | Acts more as a consultant, allowing the student to take the lead |

Outcome | Demonstrates understanding of the subject | Proves capability to conduct independent and original research |

Wrapping up

From understanding the foundational concept of a thesis to navigating its various components, differentiating it from a dissertation, and recognizing the importance of proper citation — this guide covers it all.

As scholars and readers, understanding these nuances not only aids in academic pursuits but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the relentless quest for knowledge that drives academia.

It’s important to remember that every thesis is a testament to curiosity, dedication, and the indomitable spirit of discovery.

Good luck with your thesis writing!

Frequently Asked Questions

A thesis typically ranges between 40-80 pages, but its length can vary based on the research topic, institution guidelines, and level of study.

A PhD thesis usually spans 200-300 pages, though this can vary based on the discipline, complexity of the research, and institutional requirements.

To identify a thesis topic, consider current trends in your field, gaps in existing literature, personal interests, and discussions with advisors or mentors. Additionally, reviewing related journals and conference proceedings can provide insights into potential areas of exploration.

The conceptual framework is often situated in the literature review or theoretical framework section of a thesis. It helps set the stage by providing the context, defining key concepts, and explaining the relationships between variables.

A thesis statement should be concise, clear, and specific. It should state the main argument or point of your research. Start by pinpointing the central question or issue your research addresses, then condense that into a single statement, ensuring it reflects the essence of your paper.

You might also like

Boosting Citations: A Comparative Analysis of Graphical Abstract vs. Video Abstract

The Impact of Visual Abstracts on Boosting Citations

Introducing SciSpace’s Citation Booster To Increase Research Visibility

Definitions of terms in a bachelors', master's or PhD thesis - 3 cases

Finding a suitable definition for a term in a bachelor's thesis, master's thesis or dissertation is often tedious, but absolutely necessary. Otherwise, you start from scratch. There are often many definitions for the same term...

What definition do I use? Fortunately, there are proven methods for searching and formulating definitions. This will help you get a grip on the terms. Let's go!

What is a definition?

A definition always leads a term back to a generic term. In an academic paper, such as a Bachelor's thesis, Master's Thesis or dissertation, the definitions MUST come from recognized sources. But sometimes there aren’t any scientific sources for a research subject, which is especially true when exploring a new field. At that point, you have to formulate a definition yourself.

Three cases can be distinguished with regard to the definition of terms:

- Accepted term - Case 1

- New inconsistent concept - case 2

- New, largely unexplored term (YOUR focus) - Case 3.

Let's go through the cases in order.

Case 1: Definition of an accepted term

The term has been known for a long time and is frequently used in scientific sources. The definitions in different sources are relatively consistent. This can be seen from the fact that the same source references appear repeatedly in definitions.

Examples of such terms are attitudes, motivation, incentives, learning disabilities or controlling.

Such terms are hardly ever discussed anymore. They are simply implied by the definition. Nevertheless, there may be new variations of definitions. However, they are usually for a very specific term and therefore not relevant for your text.

A quick way to get started in defining these terms:

- Be sure to use the correct spelling of the term. Distinguish singular and plural. Search the term in Google.

- Go to Wikipedia and look up the references inside the term article. Focus on scientific sources like books or papers. (Of course you can also do this without a wiki!)

- Locate these sources and gather them. Search at the beginning of the chapter or book for possible definitions. Usually several authors are cited. This is followed by a proposal for a definition, as it is subsequently used in the textbook.

- Adopt this definition, but refer to the original source if it came from another source.

- Write the definition into your text, with the full reference.

IMPORTANT: Do not use Google, Wikipedia, other pure online sources or encyclopedias as a source reference for definitions of recognized terms. It signals carelessness, if not laziness... The only possible sources for the definition of terms are

- textbooks or reference books

- scientific articles (paper)

- lists of standards like DIN, ISO, Law Codices...

By the way, the best sources are standards like DIN and ISO or laws of all kinds. These legal definitions are the best.

Case 2: Definition of still inconsistent term

A characteristic of this type of term is the existence of several definitions by different authors. Ultimately, each definition focuses on specific characteristics. That is why it is often not "either-or", but "both-also".

This is reminiscent of the example with the elephant, which six blind people examine by touch and then describe. The person who touches the trunk says it is a snake. The one sitting on his back says, "That's a mountain." Whoever touches the legs says it is a tree trunk, the ears are ferns, the ivory teeth are field cliffs, etc.

This situation is typical for relatively new subject areas where there is still a lot to discover. New is of course relative and depends on the subject. If there are only five to ten articles on a subject area, this indicates a need for research.

Examples of such terms are social media, trust, mediation.

Proceed as follows when defining these terms for the dissertation:

- Search for the relevant authors on the subject area.

- Search in their scientific articles for the definitions used.

- Make an overview of these definitions. Literally and with reference!!

- Filter out the substance from the respective definitions, the central words and the generic term.

- Check which of these definitions fits your approach.

- Use the appropriate definition or combine several definitions.

- Reconsider and justify your decision. Further work depends on this.

- Ask experts in the field, authors of papers.

- Agree upon the definition with the supervisor of the dissertation.

Case 3: Definition of new, still largely unexplored terms = focus of a dissertation

In this case it is a completely new concept. So far, there are only definitions of experts with experience in the subject area. These have themselves formulated a definition, but it has not been recognized officially. In any case, there are no recognized scientific sources on the field of research to date. But you need a clear definition for your text.

IMPORTANT: Please think very carefully if you really want to work on this topic. The lack of scientifically formulated definitions suggests that this could be an extremely tedious project. You practically have to explore the field without any orientation in the literature. Maybe you are the first to build a model. It could be heroic, but I'm sure it's a lot of work.

This is how you should proceed with new terms in the dissertation:

- Collect all available publications with information on this topic.

- Sort the publications found according to their quality, substance and scientific quality. Use only the best sources (data sources must be traceable and trustworthy)

- Make a comprehensive word cloud of relevant terms and variants.

- Collect the characteristics for the object or terms.

- Think carefully about which other terms are related to the term.

- Filter the ideas and arguments from texts that describe characteristics and are heading towards a definition.

- Make a list of these attributes. These are candidates for the definition.

- Search for generic terms for the term in appropriate documents.

- Make a list.

If you have collected enough sources or five days have passed (whichever happens first):

- Formulate YOUR first definition.

- Leave it for a day or two.

- Check, revise, iterate, collect the evidence, share the definition with others.

- Formulate the working definition for your text. It may be refined along the way.

- Discuss the draft of your definition with the supervisor or even with experts as soon as you are sure you have something to show.

IMPORTANT: Include the reference for each quote.

Now formulate the preliminary working definition that you will use during your research for the dissertation. Refine it if necessary.

Good luck writing your text! Silvio and the Aristolo Team

PS: Check out the Thesis-ABC and the Thesis Guide for writing a bachelor's or master's thesis in 31 days.

Medical Dictionary

Search medical terms and abbreviations with the most up-to-date and comprehensive medical dictionary from the reference experts at Merriam-Webster. Master today's medical vocabulary. Become an informed health-care consumer!

Browse the Medical Dictionary

Featured game.

Find the Best Synonym

Test your vocabulary with our 10-question quiz!

Ringo Starr & 'Drum'

Shaquille O'Neal & 'Dominant'

Katy Perry & 'Firework'

How to Use a Dictionary

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Games & Quizzes

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

How to Write the Definition of Terms in Chapter 1 of a Thesis

Related Papers

Meta: Journal des traducteurs

Phaedra Royle

Rahmadi Nirwanto

The study is intended to describe the methods of defining terms found in the theses of the English Foreign Language (EFL) students of IAIN Palangka Raya. The method to be used is a mixed method, qualitative and quantitative. Quantitative approach was used to identify, describe the frequencies, and classify the methods of defining terms. In interpreting and explaining the types of method to be used, the writer used qualitative approach. In qualitative approach, data were described in the form of words and explanation. The findings show that there were two methods of defining terms, dictionary approach and athoritative reference.

Terminology

Blaise Nkwenti