Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Case analysis is a problem-based teaching and learning method that involves critically analyzing complex scenarios within an organizational setting for the purpose of placing the student in a “real world” situation and applying reflection and critical thinking skills to contemplate appropriate solutions, decisions, or recommended courses of action. It is considered a more effective teaching technique than in-class role playing or simulation activities. The analytical process is often guided by questions provided by the instructor that ask students to contemplate relationships between the facts and critical incidents described in the case.

Cases generally include both descriptive and statistical elements and rely on students applying abductive reasoning to develop and argue for preferred or best outcomes [i.e., case scenarios rarely have a single correct or perfect answer based on the evidence provided]. Rather than emphasizing theories or concepts, case analysis assignments emphasize building a bridge of relevancy between abstract thinking and practical application and, by so doing, teaches the value of both within a specific area of professional practice.

Given this, the purpose of a case analysis paper is to present a structured and logically organized format for analyzing the case situation. It can be assigned to students individually or as a small group assignment and it may include an in-class presentation component. Case analysis is predominately taught in economics and business-related courses, but it is also a method of teaching and learning found in other applied social sciences disciplines, such as, social work, public relations, education, journalism, and public administration.

Ellet, William. The Case Study Handbook: A Student's Guide . Revised Edition. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2018; Christoph Rasche and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Analysis . Writing Center, Baruch College; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

How to Approach Writing a Case Analysis Paper

The organization and structure of a case analysis paper can vary depending on the organizational setting, the situation, and how your professor wants you to approach the assignment. Nevertheless, preparing to write a case analysis paper involves several important steps. As Hawes notes, a case analysis assignment “...is useful in developing the ability to get to the heart of a problem, analyze it thoroughly, and to indicate the appropriate solution as well as how it should be implemented” [p.48]. This statement encapsulates how you should approach preparing to write a case analysis paper.

Before you begin to write your paper, consider the following analytical procedures:

- Review the case to get an overview of the situation . A case can be only a few pages in length, however, it is most often very lengthy and contains a significant amount of detailed background information and statistics, with multilayered descriptions of the scenario, the roles and behaviors of various stakeholder groups, and situational events. Therefore, a quick reading of the case will help you gain an overall sense of the situation and illuminate the types of issues and problems that you will need to address in your paper. If your professor has provided questions intended to help frame your analysis, use them to guide your initial reading of the case.

- Read the case thoroughly . After gaining a general overview of the case, carefully read the content again with the purpose of understanding key circumstances, events, and behaviors among stakeholder groups. Look for information or data that appears contradictory, extraneous, or misleading. At this point, you should be taking notes as you read because this will help you develop a general outline of your paper. The aim is to obtain a complete understanding of the situation so that you can begin contemplating tentative answers to any questions your professor has provided or, if they have not provided, developing answers to your own questions about the case scenario and its connection to the course readings,lectures, and class discussions.

- Determine key stakeholder groups, issues, and events and the relationships they all have to each other . As you analyze the content, pay particular attention to identifying individuals, groups, or organizations described in the case and identify evidence of any problems or issues of concern that impact the situation in a negative way. Other things to look for include identifying any assumptions being made by or about each stakeholder, potential biased explanations or actions, explicit demands or ultimatums , and the underlying concerns that motivate these behaviors among stakeholders. The goal at this stage is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the situational and behavioral dynamics of the case and the explicit and implicit consequences of each of these actions.

- Identify the core problems . The next step in most case analysis assignments is to discern what the core [i.e., most damaging, detrimental, injurious] problems are within the organizational setting and to determine their implications. The purpose at this stage of preparing to write your analysis paper is to distinguish between the symptoms of core problems and the core problems themselves and to decide which of these must be addressed immediately and which problems do not appear critical but may escalate over time. Identify evidence from the case to support your decisions by determining what information or data is essential to addressing the core problems and what information is not relevant or is misleading.

- Explore alternative solutions . As noted, case analysis scenarios rarely have only one correct answer. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that the process of analyzing the case and diagnosing core problems, while based on evidence, is a subjective process open to various avenues of interpretation. This means that you must consider alternative solutions or courses of action by critically examining strengths and weaknesses, risk factors, and the differences between short and long-term solutions. For each possible solution or course of action, consider the consequences they may have related to their implementation and how these recommendations might lead to new problems. Also, consider thinking about your recommended solutions or courses of action in relation to issues of fairness, equity, and inclusion.

- Decide on a final set of recommendations . The last stage in preparing to write a case analysis paper is to assert an opinion or viewpoint about the recommendations needed to help resolve the core problems as you see them and to make a persuasive argument for supporting this point of view. Prepare a clear rationale for your recommendations based on examining each element of your analysis. Anticipate possible obstacles that could derail their implementation. Consider any counter-arguments that could be made concerning the validity of your recommended actions. Finally, describe a set of criteria and measurable indicators that could be applied to evaluating the effectiveness of your implementation plan.

Use these steps as the framework for writing your paper. Remember that the more detailed you are in taking notes as you critically examine each element of the case, the more information you will have to draw from when you begin to write. This will save you time.

NOTE : If the process of preparing to write a case analysis paper is assigned as a student group project, consider having each member of the group analyze a specific element of the case, including drafting answers to the corresponding questions used by your professor to frame the analysis. This will help make the analytical process more efficient and ensure that the distribution of work is equitable. This can also facilitate who is responsible for drafting each part of the final case analysis paper and, if applicable, the in-class presentation.

Framework for Case Analysis . College of Management. University of Massachusetts; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Rasche, Christoph and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Study Analysis . University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center; Van Ness, Raymond K. A Guide to Case Analysis . School of Business. State University of New York, Albany; Writing a Case Analysis . Business School, University of New South Wales.

Structure and Writing Style

A case analysis paper should be detailed, concise, persuasive, clearly written, and professional in tone and in the use of language . As with other forms of college-level academic writing, declarative statements that convey information, provide a fact, or offer an explanation or any recommended courses of action should be based on evidence. If allowed by your professor, any external sources used to support your analysis, such as course readings, should be properly cited under a list of references. The organization and structure of case analysis papers can vary depending on your professor’s preferred format, but its structure generally follows the steps used for analyzing the case.

Introduction

The introduction should provide a succinct but thorough descriptive overview of the main facts, issues, and core problems of the case . The introduction should also include a brief summary of the most relevant details about the situation and organizational setting. This includes defining the theoretical framework or conceptual model on which any questions were used to frame your analysis.

Following the rules of most college-level research papers, the introduction should then inform the reader how the paper will be organized. This includes describing the major sections of the paper and the order in which they will be presented. Unless you are told to do so by your professor, you do not need to preview your final recommendations in the introduction. U nlike most college-level research papers , the introduction does not include a statement about the significance of your findings because a case analysis assignment does not involve contributing new knowledge about a research problem.

Background Analysis

Background analysis can vary depending on any guiding questions provided by your professor and the underlying concept or theory that the case is based upon. In general, however, this section of your paper should focus on:

- Providing an overarching analysis of problems identified from the case scenario, including identifying events that stakeholders find challenging or troublesome,

- Identifying assumptions made by each stakeholder and any apparent biases they may exhibit,

- Describing any demands or claims made by or forced upon key stakeholders, and

- Highlighting any issues of concern or complaints expressed by stakeholders in response to those demands or claims.

These aspects of the case are often in the form of behavioral responses expressed by individuals or groups within the organizational setting. However, note that problems in a case situation can also be reflected in data [or the lack thereof] and in the decision-making, operational, cultural, or institutional structure of the organization. Additionally, demands or claims can be either internal and external to the organization [e.g., a case analysis involving a president considering arms sales to Saudi Arabia could include managing internal demands from White House advisors as well as demands from members of Congress].

Throughout this section, present all relevant evidence from the case that supports your analysis. Do not simply claim there is a problem, an assumption, a demand, or a concern; tell the reader what part of the case informed how you identified these background elements.

Identification of Problems

In most case analysis assignments, there are problems, and then there are problems . Each problem can reflect a multitude of underlying symptoms that are detrimental to the interests of the organization. The purpose of identifying problems is to teach students how to differentiate between problems that vary in severity, impact, and relative importance. Given this, problems can be described in three general forms: those that must be addressed immediately, those that should be addressed but the impact is not severe, and those that do not require immediate attention and can be set aside for the time being.

All of the problems you identify from the case should be identified in this section of your paper, with a description based on evidence explaining the problem variances. If the assignment asks you to conduct research to further support your assessment of the problems, include this in your explanation. Remember to cite those sources in a list of references. Use specific evidence from the case and apply appropriate concepts, theories, and models discussed in class or in relevant course readings to highlight and explain the key problems [or problem] that you believe must be solved immediately and describe the underlying symptoms and why they are so critical.

Alternative Solutions

This section is where you provide specific, realistic, and evidence-based solutions to the problems you have identified and make recommendations about how to alleviate the underlying symptomatic conditions impacting the organizational setting. For each solution, you must explain why it was chosen and provide clear evidence to support your reasoning. This can include, for example, course readings and class discussions as well as research resources, such as, books, journal articles, research reports, or government documents. In some cases, your professor may encourage you to include personal, anecdotal experiences as evidence to support why you chose a particular solution or set of solutions. Using anecdotal evidence helps promote reflective thinking about the process of determining what qualifies as a core problem and relevant solution .

Throughout this part of the paper, keep in mind the entire array of problems that must be addressed and describe in detail the solutions that might be implemented to resolve these problems.

Recommended Courses of Action

In some case analysis assignments, your professor may ask you to combine the alternative solutions section with your recommended courses of action. However, it is important to know the difference between the two. A solution refers to the answer to a problem. A course of action refers to a procedure or deliberate sequence of activities adopted to proactively confront a situation, often in the context of accomplishing a goal. In this context, proposed courses of action are based on your analysis of alternative solutions. Your description and justification for pursuing each course of action should represent the overall plan for implementing your recommendations.

For each course of action, you need to explain the rationale for your recommendation in a way that confronts challenges, explains risks, and anticipates any counter-arguments from stakeholders. Do this by considering the strengths and weaknesses of each course of action framed in relation to how the action is expected to resolve the core problems presented, the possible ways the action may affect remaining problems, and how the recommended action will be perceived by each stakeholder.

In addition, you should describe the criteria needed to measure how well the implementation of these actions is working and explain which individuals or groups are responsible for ensuring your recommendations are successful. In addition, always consider the law of unintended consequences. Outline difficulties that may arise in implementing each course of action and describe how implementing the proposed courses of action [either individually or collectively] may lead to new problems [both large and small].

Throughout this section, you must consider the costs and benefits of recommending your courses of action in relation to uncertainties or missing information and the negative consequences of success.

The conclusion should be brief and introspective. Unlike a research paper, the conclusion in a case analysis paper does not include a summary of key findings and their significance, a statement about how the study contributed to existing knowledge, or indicate opportunities for future research.

Begin by synthesizing the core problems presented in the case and the relevance of your recommended solutions. This can include an explanation of what you have learned about the case in the context of your answers to the questions provided by your professor. The conclusion is also where you link what you learned from analyzing the case with the course readings or class discussions. This can further demonstrate your understanding of the relationships between the practical case situation and the theoretical and abstract content of assigned readings and other course content.

Problems to Avoid

The literature on case analysis assignments often includes examples of difficulties students have with applying methods of critical analysis and effectively reporting the results of their assessment of the situation. A common reason cited by scholars is that the application of this type of teaching and learning method is limited to applied fields of social and behavioral sciences and, as a result, writing a case analysis paper can be unfamiliar to most students entering college.

After you have drafted your paper, proofread the narrative flow and revise any of these common errors:

- Unnecessary detail in the background section . The background section should highlight the essential elements of the case based on your analysis. Focus on summarizing the facts and highlighting the key factors that become relevant in the other sections of the paper by eliminating any unnecessary information.

- Analysis relies too much on opinion . Your analysis is interpretive, but the narrative must be connected clearly to evidence from the case and any models and theories discussed in class or in course readings. Any positions or arguments you make should be supported by evidence.

- Analysis does not focus on the most important elements of the case . Your paper should provide a thorough overview of the case. However, the analysis should focus on providing evidence about what you identify are the key events, stakeholders, issues, and problems. Emphasize what you identify as the most critical aspects of the case to be developed throughout your analysis. Be thorough but succinct.

- Writing is too descriptive . A paper with too much descriptive information detracts from your analysis of the complexities of the case situation. Questions about what happened, where, when, and by whom should only be included as essential information leading to your examination of questions related to why, how, and for what purpose.

- Inadequate definition of a core problem and associated symptoms . A common error found in case analysis papers is recommending a solution or course of action without adequately defining or demonstrating that you understand the problem. Make sure you have clearly described the problem and its impact and scope within the organizational setting. Ensure that you have adequately described the root causes w hen describing the symptoms of the problem.

- Recommendations lack specificity . Identify any use of vague statements and indeterminate terminology, such as, “A particular experience” or “a large increase to the budget.” These statements cannot be measured and, as a result, there is no way to evaluate their successful implementation. Provide specific data and use direct language in describing recommended actions.

- Unrealistic, exaggerated, or unattainable recommendations . Review your recommendations to ensure that they are based on the situational facts of the case. Your recommended solutions and courses of action must be based on realistic assumptions and fit within the constraints of the situation. Also note that the case scenario has already happened, therefore, any speculation or arguments about what could have occurred if the circumstances were different should be revised or eliminated.

Bee, Lian Song et al. "Business Students' Perspectives on Case Method Coaching for Problem-Based Learning: Impacts on Student Engagement and Learning Performance in Higher Education." Education & Training 64 (2022): 416-432; The Case Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors. Grand Valley State University; Georgallis, Panikos and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching using Case-Based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Georgallis, Panikos, and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching Using Case-based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; .Dean, Kathy Lund and Charles J. Fornaciari. "How to Create and Use Experiential Case-Based Exercises in a Management Classroom." Journal of Management Education 26 (October 2002): 586-603; Klebba, Joanne M. and Janet G. Hamilton. "Structured Case Analysis: Developing Critical Thinking Skills in a Marketing Case Course." Journal of Marketing Education 29 (August 2007): 132-137, 139; Klein, Norman. "The Case Discussion Method Revisited: Some Questions about Student Skills." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 30-32; Mukherjee, Arup. "Effective Use of In-Class Mini Case Analysis for Discovery Learning in an Undergraduate MIS Course." The Journal of Computer Information Systems 40 (Spring 2000): 15-23; Pessoa, Silviaet al. "Scaffolding the Case Analysis in an Organizational Behavior Course: Making Analytical Language Explicit." Journal of Management Education 46 (2022): 226-251: Ramsey, V. J. and L. D. Dodge. "Case Analysis: A Structured Approach." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 27-29; Schweitzer, Karen. "How to Write and Format a Business Case Study." ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/how-to-write-and-format-a-business-case-study-466324 (accessed December 5, 2022); Reddy, C. D. "Teaching Research Methodology: Everything's a Case." Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 18 (December 2020): 178-188; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

Writing Tip

Ca se Study and Case Analysis Are Not the Same!

Confusion often exists between what it means to write a paper that uses a case study research design and writing a paper that analyzes a case; they are two different types of approaches to learning in the social and behavioral sciences. Professors as well as educational researchers contribute to this confusion because they often use the term "case study" when describing the subject of analysis for a case analysis paper. But you are not studying a case for the purpose of generating a comprehensive, multi-faceted understanding of a research problem. R ather, you are critically analyzing a specific scenario to argue logically for recommended solutions and courses of action that lead to optimal outcomes applicable to professional practice.

To avoid any confusion, here are twelve characteristics that delineate the differences between writing a paper using the case study research method and writing a case analysis paper:

- Case study is a method of in-depth research and rigorous inquiry ; case analysis is a reliable method of teaching and learning . A case study is a modality of research that investigates a phenomenon for the purpose of creating new knowledge, solving a problem, or testing a hypothesis using empirical evidence derived from the case being studied. Often, the results are used to generalize about a larger population or within a wider context. The writing adheres to the traditional standards of a scholarly research study. A case analysis is a pedagogical tool used to teach students how to reflect and think critically about a practical, real-life problem in an organizational setting.

- The researcher is responsible for identifying the case to study; a case analysis is assigned by your professor . As the researcher, you choose the case study to investigate in support of obtaining new knowledge and understanding about the research problem. The case in a case analysis assignment is almost always provided, and sometimes written, by your professor and either given to every student in class to analyze individually or to a small group of students, or students select a case to analyze from a predetermined list.

- A case study is indeterminate and boundless; a case analysis is predetermined and confined . A case study can be almost anything [see item 9 below] as long as it relates directly to examining the research problem. This relationship is the only limit to what a researcher can choose as the subject of their case study. The content of a case analysis is determined by your professor and its parameters are well-defined and limited to elucidating insights of practical value applied to practice.

- Case study is fact-based and describes actual events or situations; case analysis can be entirely fictional or adapted from an actual situation . The entire content of a case study must be grounded in reality to be a valid subject of investigation in an empirical research study. A case analysis only needs to set the stage for critically examining a situation in practice and, therefore, can be entirely fictional or adapted, all or in-part, from an actual situation.

- Research using a case study method must adhere to principles of intellectual honesty and academic integrity; a case analysis scenario can include misleading or false information . A case study paper must report research objectively and factually to ensure that any findings are understood to be logically correct and trustworthy. A case analysis scenario may include misleading or false information intended to deliberately distract from the central issues of the case. The purpose is to teach students how to sort through conflicting or useless information in order to come up with the preferred solution. Any use of misleading or false information in academic research is considered unethical.

- Case study is linked to a research problem; case analysis is linked to a practical situation or scenario . In the social sciences, the subject of an investigation is most often framed as a problem that must be researched in order to generate new knowledge leading to a solution. Case analysis narratives are grounded in real life scenarios for the purpose of examining the realities of decision-making behavior and processes within organizational settings. A case analysis assignments include a problem or set of problems to be analyzed. However, the goal is centered around the act of identifying and evaluating courses of action leading to best possible outcomes.

- The purpose of a case study is to create new knowledge through research; the purpose of a case analysis is to teach new understanding . Case studies are a choice of methodological design intended to create new knowledge about resolving a research problem. A case analysis is a mode of teaching and learning intended to create new understanding and an awareness of uncertainty applied to practice through acts of critical thinking and reflection.

- A case study seeks to identify the best possible solution to a research problem; case analysis can have an indeterminate set of solutions or outcomes . Your role in studying a case is to discover the most logical, evidence-based ways to address a research problem. A case analysis assignment rarely has a single correct answer because one of the goals is to force students to confront the real life dynamics of uncertainly, ambiguity, and missing or conflicting information within professional practice. Under these conditions, a perfect outcome or solution almost never exists.

- Case study is unbounded and relies on gathering external information; case analysis is a self-contained subject of analysis . The scope of a case study chosen as a method of research is bounded. However, the researcher is free to gather whatever information and data is necessary to investigate its relevance to understanding the research problem. For a case analysis assignment, your professor will often ask you to examine solutions or recommended courses of action based solely on facts and information from the case.

- Case study can be a person, place, object, issue, event, condition, or phenomenon; a case analysis is a carefully constructed synopsis of events, situations, and behaviors . The research problem dictates the type of case being studied and, therefore, the design can encompass almost anything tangible as long as it fulfills the objective of generating new knowledge and understanding. A case analysis is in the form of a narrative containing descriptions of facts, situations, processes, rules, and behaviors within a particular setting and under a specific set of circumstances.

- Case study can represent an open-ended subject of inquiry; a case analysis is a narrative about something that has happened in the past . A case study is not restricted by time and can encompass an event or issue with no temporal limit or end. For example, the current war in Ukraine can be used as a case study of how medical personnel help civilians during a large military conflict, even though circumstances around this event are still evolving. A case analysis can be used to elicit critical thinking about current or future situations in practice, but the case itself is a narrative about something finite and that has taken place in the past.

- Multiple case studies can be used in a research study; case analysis involves examining a single scenario . Case study research can use two or more cases to examine a problem, often for the purpose of conducting a comparative investigation intended to discover hidden relationships, document emerging trends, or determine variations among different examples. A case analysis assignment typically describes a stand-alone, self-contained situation and any comparisons among cases are conducted during in-class discussions and/or student presentations.

The Case Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors. Grand Valley State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Ramsey, V. J. and L. D. Dodge. "Case Analysis: A Structured Approach." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 27-29; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2017; Crowe, Sarah et al. “The Case Study Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 11 (2011): doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 1994.

- << Previous: Reviewing Collected Works

- Next: Writing a Case Study >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Organizational behavior.

- Neal M. Ashkanasy Neal M. Ashkanasy University of Queensland

- and Alana D. Dorris Alana D. Dorris University of Queensland

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.23

- Published online: 29 March 2017

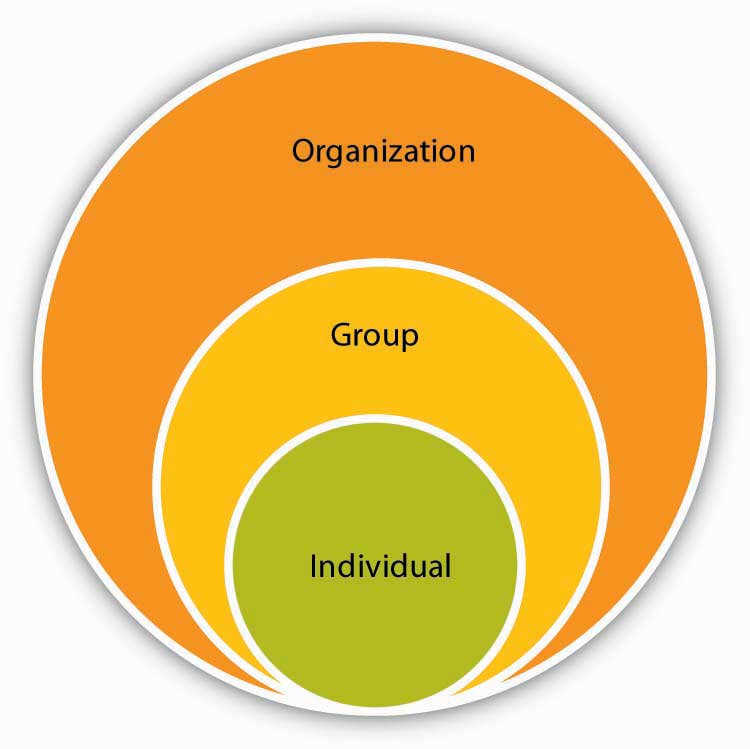

Organizational behavior (OB) is a discipline that includes principles from psychology, sociology, and anthropology. Its focus is on understanding how people behave in organizational work environments. Broadly speaking, OB covers three main levels of analysis: micro (individuals), meso (groups), and macro (the organization). Topics at the micro level include managing the diverse workforce; effects of individual differences in attitudes; job satisfaction and engagement, including their implications for performance and management; personality, including the effects of different cultures; perception and its effects on decision-making; employee values; emotions, including emotional intelligence, emotional labor, and the effects of positive and negative affect on decision-making and creativity (including common biases and errors in decision-making); and motivation, including the effects of rewards and goal-setting and implications for management. Topics at the meso level of analysis include group decision-making; managing work teams for optimum performance (including maximizing team performance and communication); managing team conflict (including the effects of task and relationship conflict on team effectiveness); team climate and group emotional tone; power, organizational politics, and ethical decision-making; and leadership, including leadership development and leadership effectiveness. At the organizational level, topics include organizational design and its effect on organizational performance; affective events theory and the physical environment; organizational culture and climate; and organizational change.

- organizational psychology

- organizational sociology

- organizational anthropology

Introduction

Organizational behavior (OB) is the study of how people behave in organizational work environments. More specifically, Robbins, Judge, Millett, and Boyle ( 2014 , p. 8) describe it as “[a] field of study that investigates the impact that individual groups and structure have on behavior within organizations, for the purposes of applying such knowledge towards improving an organization’s effectiveness.” The OB field looks at the specific context of the work environment in terms of human attitudes, cognition, and behavior, and it embodies contributions from psychology, social psychology, sociology, and anthropology. The field is also rapidly evolving because of the demands of today’s fast-paced world, where technology has given rise to work-from-home employees, globalization, and an ageing workforce. Thus, while managers and OB researchers seek to help employees find a work-life balance, improve ethical behavior (Ardichivili, Mitchell, & Jondle, 2009 ), customer service, and people skills (see, e.g., Brady & Cronin, 2001 ), they must simultaneously deal with issues such as workforce diversity, work-life balance, and cultural differences.

The most widely accepted model of OB consists of three interrelated levels: (1) micro (the individual level), (2) meso (the group level), and (3) macro (the organizational level). The behavioral sciences that make up the OB field contribute an element to each of these levels. In particular, OB deals with the interactions that take place among the three levels and, in turn, addresses how to improve performance of the organization as a whole.

In order to study OB and apply it to the workplace, it is first necessary to understand its end goal. In particular, if the goal is organizational effectiveness, then these questions arise: What can be done to make an organization more effective? And what determines organizational effectiveness? To answer these questions, dependent variables that include attitudes and behaviors such as productivity, job satisfaction, job performance, turnover intentions, withdrawal, motivation, and workplace deviance are introduced. Moreover, each level—micro, meso, and macro—has implications for guiding managers in their efforts to create a healthier work climate to enable increased organizational performance that includes higher sales, profits, and return on investment (ROE).

The Micro (Individual) Level of Analysis

The micro or individual level of analysis has its roots in social and organizational psychology. In this article, six central topics are identified and discussed: (1) diversity; (2) attitudes and job satisfaction; (3) personality and values; (4) emotions and moods; (5) perception and individual decision-making; and (6) motivation.

An obvious but oft-forgotten element at the individual level of OB is the diverse workforce. It is easy to recognize how different each employee is in terms of personal characteristics like age, skin color, nationality, ethnicity, and gender. Other, less biological characteristics include tenure, religion, sexual orientation, and gender identity. In the Australian context, while the Commonwealth Disability Discrimination Act of 1992 helped to increase participation of people with disabilities working in organizations, discrimination and exclusion still continue to inhibit equality (Feather & Boeckmann, 2007 ). In Western societies like Australia and the United States, however, antidiscrimination legislation is now addressing issues associated with an ageing workforce.

In terms of gender, there continues to be significant discrimination against female employees. Males have traditionally had much higher participation in the workforce, with only a significant increase in the female workforce beginning in the mid-1980s. Additionally, according to Ostroff and Atwater’s ( 2003 ) study of engineering managers, female managers earn a significantly lower salary than their male counterparts, especially when they are supervising mostly other females.

Job Satisfaction and Job Engagement

Job satisfaction is an attitudinal variable that comes about when an employee evaluates all the components of her or his job, which include affective, cognitive, and behavioral aspects (Weiss, 2002 ). Increased job satisfaction is associated with increased job performance, organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs), and reduced turnover intentions (Wilkin, 2012 ). Moreover, traditional workers nowadays are frequently replaced by contingent workers in order to reduce costs and work in a nonsystematic manner. According to Wilkin’s ( 2012 ) findings, however, contingent workers as a group are less satisfied with their jobs than permanent employees are.

Job engagement concerns the degree of involvement that an employee experiences on the job (Kahn, 1990 ). It describes the degree to which an employee identifies with their job and considers their performance in that job important; it also determines that employee’s level of participation within their workplace. Britt, Dickinson, Greene-Shortridge, and McKibbin ( 2007 ) describe the two extremes of job satisfaction and employee engagement: a feeling of responsibility and commitment to superior job performance versus a feeling of disengagement leading to the employee wanting to withdraw or disconnect from work. The first scenario is also related to organizational commitment, the level of identification an employee has with an organization and its goals. Employees with high organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and employee engagement tend to perceive that their organization values their contribution and contributes to their wellbeing.

Personality represents a person’s enduring traits. The key here is the concept of enduring . The most widely adopted model of personality is the so-called Big Five (Costa & McCrae, 1992 ): extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness. Employees high in conscientiousness tend to have higher levels of job knowledge, probably because they invest more into learning about their role. Those higher in emotional stability tend to have higher levels of job satisfaction and lower levels of stress, most likely because of their positive and opportunistic outlooks. Agreeableness, similarly, is associated with being better liked and may lead to higher employee performance and decreased levels of deviant behavior.

Although the personality traits in the Big Five have been shown to relate to organizational behavior, organizational performance, career success (Judge, Higgins, Thoresen, & Barrick, 2006 ), and other personality traits are also relevant to the field. Examples include positive self-evaluation, self-monitoring (the degree to which an individual is aware of comparisons with others), Machiavellianism (the degree to which a person is practical, maintains emotional distance, and believes the end will justify the means), narcissism (having a grandiose sense of self-importance and entitlement), risk-taking, proactive personality, and type A personality. In particular, those who like themselves and are grounded in their belief that they are capable human beings are more likely to perform better because they have fewer self-doubts that may impede goal achievements. Individuals high in Machiavellianism may need a certain environment in order to succeed, such as a job that requires negotiation skills and offers significant rewards, although their inclination to engage in political behavior can sometimes limit their potential. Employees who are high on narcissism may wreak organizational havoc by manipulating subordinates and harming the overall business because of their over-inflated perceptions of self. Higher levels of self-monitoring often lead to better performance but they may cause lower commitment to the organization. Risk-taking can be positive or negative; it may be great for someone who thrives on rapid decision-making, but it may prove stressful for someone who likes to weigh pros and cons carefully before making decisions. Type A individuals may achieve high performance but may risk doing so in a way that causes stress and conflict. Proactive personality, on the other hand, is usually associated with positive organizational performance.

Employee Values

Personal value systems are behind each employee’s attitudes and personality. Each employee enters an organization with an already established set of beliefs about what should be and what should not be. Today, researchers realize that personality and values are linked to organizations and organizational behavior. Years ago, only personality’s relation to organizations was of concern, but now managers are more interested in an employee’s flexibility to adapt to organizational change and to remain high in organizational commitment. Holland’s ( 1973 ) theory of personality-job fit describes six personality types (realistic, investigative, social, conventional, enterprising, and artistic) and theorizes that job satisfaction and turnover are determined by how well a person matches her or his personality to a job. In addition to person-job (P-J) fit, researchers have also argued for person-organization (P-O) fit, whereby employees desire to be a part of and are selected by an organization that matches their values. The Big Five would suggest, for example, that extraverted employees would desire to be in team environments; agreeable people would align well with supportive organizational cultures rather than more aggressive ones; and people high on openness would fit better in organizations that emphasize creativity and innovation (Anderson, Spataro, & Flynn, 2008 ).

Individual Differences, Affect, and Emotion

Personality predisposes people to have certain moods (feelings that tend to be less intense but longer lasting than emotions) and emotions (intense feelings directed at someone or something). In particular, personalities with extraversion and emotional stability partially determine an individual predisposition to experience emotion more or less intensely.

Affect is also related as describing the positive and negative feelings that people experience (Ashkanasy, 2003 ). Moreover, emotions, mood, and affect interrelate; a bad mood, for instance, can lead individuals to experience a negative emotion. Emotions are action-oriented while moods tend to be more cognitive. This is because emotions are caused by a specific event that might only last a few seconds, while moods are general and can last for hours or even days. One of the sources of emotions is personality. Dispositional or trait affects correlate, on the one hand, with personality and are what make an individual more likely to respond to a situation in a predictable way (Watson & Tellegen, 1985 ). Moreover, like personality, affective traits have proven to be stable over time and across settings (Diener, Larsen, Levine, & Emmons, 1985 ; Watson, 1988 ; Watson & Tellegen, 1985 ; Watson & Walker, 1996 ). State affect, on the other hand, is similar to mood and represents how an individual feels in the moment.

The Role of Affect in Organizational Behavior

For many years, affect and emotions were ignored in the field of OB despite being fundamental factors underlying employee behavior (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1995 ). OB researchers traditionally focused on solely decreasing the effects of strong negative emotions that were seen to impede individual, group, and organizational level productivity. More recent theories of OB focus, however, on affect, which is seen to have positive, as well as negative, effects on behavior, described by Barsade, Brief, and Spataro ( 2003 , p. 3) as the “affective revolution.” In particular, scholars now understand that emotions can be measured objectively and be observed through nonverbal displays such as facial expression and gestures, verbal displays, fMRI, and hormone levels (Ashkanasy, 2003 ; Rashotte, 2002 ).

Fritz, Sonnentag, Spector, and McInroe ( 2010 ) focus on the importance of stress recovery in affective experiences. In fact, an individual employee’s affective state is critical to OB, and today more attention is being focused on discrete affective states. Emotions like fear and sadness may be related to counterproductive work behaviors (Judge et al., 2006 ). Stress recovery is another factor that is essential for more positive moods leading to positive organizational outcomes. In a study, Fritz et al. ( 2010 ) looked at levels of psychological detachment of employees on weekends away from the workplace and how it was associated with higher wellbeing and affect.

Emotional Intelligence and Emotional Labor

Ashkanasy and Daus ( 2002 ) suggest that emotional intelligence is distinct but positively related to other types of intelligence like IQ. It is defined by Mayer and Salovey ( 1997 ) as the ability to perceive, assimilate, understand, and manage emotion in the self and others. As such, it is an individual difference and develops over a lifetime, but it can be improved with training. Boyatzis and McKee ( 2005 ) describe emotional intelligence further as a form of adaptive resilience, insofar as employees high in emotional intelligence tend to engage in positive coping mechanisms and take a generally positive outlook toward challenging work situations.

Emotional labor occurs when an employee expresses her or his emotions in a way that is consistent with an organization’s display rules, and usually means that the employee engages in either surface or deep acting (Hochschild, 1983 ). This is because the emotions an employee is expressing as part of their role at work may be different from the emotions they are actually feeling (Ozcelik, 2013 ). Emotional labor has implications for an employee’s mental and physical health and wellbeing. Moreover, because of the discrepancy between felt emotions (how an employee actually feels) and displayed emotions or surface acting (what the organization requires the employee to emotionally display), surface acting has been linked to negative organizational outcomes such as heightened emotional exhaustion and reduced commitment (Erickson & Wharton, 1997 ; Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002 ; Grandey, 2003 ; Groth, Hennig-Thurau, & Walsh, 2009 ).

Affect and Organizational Decision-Making

Ashkanasy and Ashton-James ( 2008 ) make the case that the moods and emotions managers experience in response to positive or negative workplace situations affect outcomes and behavior not only at the individual level, but also in terms of strategic decision-making processes at the organizational level. These authors focus on affective events theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996 ), which holds that organizational events trigger affective responses in organizational members, which in turn affect organizational attitudes, cognition, and behavior.

Perceptions and Behavior

Like personality, emotions, moods, and attitudes, perceptions also influence employees’ behaviors in the workplace. Perception is the way in which people organize and interpret sensory cues in order to give meaning to their surroundings. It can be influenced by time, work setting, social setting, other contextual factors such as time of day, time of year, temperature, a target’s clothing or appearance, as well as personal trait dispositions, attitudes, and value systems. In fact, a person’s behavior is based on her or his perception of reality—not necessarily the same as actual reality. Perception greatly influences individual decision-making because individuals base their behaviors on their perceptions of reality. In this regard, attribution theory (Martinko, 1995 ) outlines how individuals judge others and is our attempt to conclude whether a person’s behavior is internally or externally caused.

Decision-Making and the Role of Perception

Decision-making occurs as a reaction to a problem when the individual perceives there to be discrepancy between the current state of affairs and the state s/he desires. As such, decisions are the choices individuals make from a set of alternative courses of action. Each individual interprets information in her or his own way and decides which information is relevant to weigh pros and cons of each decision and its alternatives to come to her or his perception of the best outcome. In other words, each of our unique perceptual processes influences the final outcome (Janis & Mann, 1977 ).

Common Biases in Decision-Making

Although there is no perfect model for approaching decision-making, there are nonetheless many biases that individuals can make themselves aware of in order to maximize their outcomes. First, overconfidence bias is an inclination to overestimate the correctness of a decision. Those most likely to commit this error tend to be people with weak intellectual and interpersonal abilities. Anchoring bias occurs when individuals focus on the first information they receive, failing to adjust for information received subsequently. Marketers tend to use anchors in order to make impressions on clients quickly and project their brand names. Confirmation bias occurs when individuals only use facts that support their decisions while discounting all contrary views. Lastly, availability bias occurs when individuals base their judgments on information readily available. For example, a manager might rate an employee on a performance appraisal based on behavior in the past few days, rather than the past six months or year.

Errors in Decision-Making

Other errors in decision-making include hindsight bias and escalation of commitment . Hindsight bias is a tendency to believe, incorrectly, after an outcome of an event has already happened, that the decision-maker would have accurately predicted that same outcome. Furthermore, this bias, despite its prevalence, is especially insidious because it inhibits the ability to learn from the past and take responsibility for mistakes. Escalation of commitment is an inclination to continue with a chosen course of action instead of listening to negative feedback regarding that choice. When individuals feel responsible for their actions and those consequences, they escalate commitment probably because they have invested so much into making that particular decision. One solution to escalating commitment is to seek a source of clear, less distorted feedback (Staw, 1981 ).

The last but certainly not least important individual level topic is motivation. Like each of the topics discussed so far, a worker’s motivation is also influenced by individual differences and situational context. Motivation can be defined as the processes that explain a person’s intensity, direction, and persistence toward reaching a goal. Work motivation has often been viewed as the set of energetic forces that determine the form, direction, intensity, and duration of behavior (Latham & Pinder, 2005 ). Motivation can be further described as the persistence toward a goal. In fact many non-academics would probably describe it as the extent to which a person wants and tries to do well at a particular task (Mitchell, 1982 ).

Early theories of motivation began with Maslow’s ( 1943 ) hierarchy of needs theory, which holds that each person has five needs in hierarchical order: physiological, safety, social, esteem, and self-actualization. These constitute the “lower-order” needs, while social and esteem needs are “higher-order” needs. Self-esteem for instance underlies motivation from the time of childhood. Another early theory is McGregor’s ( 1960 ) X-Y theory of motivation: Theory X is the concept whereby individuals must be pushed to work; and theory Y is positive, embodying the assumption that employees naturally like work and responsibility and can exercise self-direction.

Herzberg subsequently proposed the “two-factor theory” that attitude toward work can determine whether an employee succeeds or fails. Herzberg ( 1966 ) relates intrinsic factors, like advancement in a job, recognition, praise, and responsibility to increased job satisfaction, while extrinsic factors like the organizational climate, relationship with supervisor, and salary relate to job dissatisfaction. In other words, the hygiene factors are associated with the work context while the motivators are associated with the intrinsic factors associated with job motivation.

Contemporary Theories of Motivation

Although traditional theories of motivation still appear in OB textbooks, there is unfortunately little empirical data to support their validity. More contemporary theories of motivation, with more acceptable research validity, include self-determination theory , which holds that people prefer to have control over their actions. If a task an individual enjoyed now feels like a chore, then this will undermine motivation. Higher self-determined motivation (or intrinsically determined motivation) is correlated with increased wellbeing, job satisfaction, commitment, and decreased burnout and turnover intent. In this regard, Fernet, Gagne, and Austin ( 2010 ) found that work motivation relates to reactions to interpersonal relationships at work and organizational burnout. Thus, by supporting work self-determination, managers can help facilitate adaptive employee organizational behaviors while decreasing turnover intention (Richer, Blanchard, & Vallerand, 2002 ).

Core self-evaluation (CSE) theory is a relatively new concept that relates to self-confidence in general, such that people with higher CSE tend to be more committed to goals (Bono & Colbert, 2005 ). These core self-evaluations also extend to interpersonal relationships, as well as employee creativity. Employees with higher CSE are more likely to trust coworkers, which may also contribute to increased motivation for goal attainment (Johnson, Kristof-Brown, van Vianen, de Pater, & Klein, 2003 ). In general, employees with positive CSE tend to be more intrinsically motivated, thus additionally playing a role in increasing employee creativity (Judge, Bono, Erez, & Locke, 2005 ). Finally, according to research by Amabile ( 1996 ), intrinsic motivation or self-determined goal attainment is critical in facilitating employee creativity.

Goal-Setting and Conservation of Resources

While self-determination theory and CSE focus on the reward system behind motivation and employee work behaviors, Locke and Latham’s ( 1990 ) goal-setting theory specifically addresses the impact that goal specificity, challenge, and feedback has on motivation and performance. These authors posit that our performance is increased when specific and difficult goals are set, rather than ambiguous and general goals. Goal-setting seems to be an important motivational tool, but it is important that the employee has had a chance to take part in the goal-setting process so they are more likely to attain their goals and perform highly.

Related to goal-setting is Hobfoll’s ( 1989 ) conservation of resources (COR) theory, which holds that people have a basic motivation to obtain, maintain, and protect what they value (i.e., their resources). Additionally there is a global application of goal-setting theory for each of the motivation theories. Not enough research has been conducted regarding the value of goal-setting in global contexts, however, and because of this, goal-setting is not recommended without consideration of cultural and work-related differences (Konopaske & Ivancevich, 2004 ).

Self-Efficacy and Motivation

Other motivational theories include self-efficacy theory, and reinforcement, equity, and expectancy theories. Self-efficacy or social cognitive or learning theory is an individual’s belief that s/he can perform a task (Bandura, 1977 ). This theory complements goal-setting theory in that self-efficacy is higher when a manager assigns a difficult task because employees attribute the manager’s behavior to him or her thinking that the employee is capable; the employee in turn feels more confident and capable.

Reinforcement theory (Skinner, 1938 ) counters goal-setting theory insofar as it is a behaviorist approach rather than cognitive and is based in the notion that reinforcement conditions behavior, or in other words focuses on external causes rather than the value an individual attributes to goals. Furthermore, this theory instead emphasizes the behavior itself rather than what precedes the behavior. Additionally, managers may use operant conditioning, a part of behaviorism, to reinforce people to act in a desired way.

Social-learning theory (Bandura, 1977 ) extends operant conditioning and also acknowledges the influence of observational learning and perception, and the fact that people can learn and retain information by paying attention, observing, and modeling the desired behavior.

Equity theory (Adams, 1963 ) looks at how employees compare themselves to others and how that affects their motivation and in turn their organizational behaviors. Employees who perceive inequity for instance, will either change how much effort they are putting in (their inputs), change or distort their perceptions (either of self or others in relation to work), change their outcomes, turnover, or choose a different referent (acknowledge performance in relation to another employee but find someone else they can be better than).

Last but not least, Vroom’s ( 1964 ) expectancy theory holds that individuals are motivated by the extent to which they can see that their effort is likely to result in valued outcomes. This theory has received strong support in empirical research (see Van Erde & Thierry, 1996 , for meta-analytic results). Like each of the preceding theories, expectancy theory has important implications that managers should consider. For instance, managers should communicate with employees to determine their preferences to know what rewards to offer subordinates to elicit motivation. Managers can also make sure to identify and communicate clearly the level of performance they desire from an employee, as well as to establish attainable goals with the employee and to be very clear and precise about how and when performance will be rewarded (Konopaske & Ivancevich, 2004 ).

The Meso (Group) Level of Analysis

The second level of OB research also emerges from social and organizational psychology and relates to groups or teams. Topics covered so far include individual differences: diversity, personality and emotions, values and attitudes, motivation, and decision-making. Thus, in this section, attention turns to how individuals come together to form groups and teams, and begins laying the foundation for understanding the dynamics of group and team behavior. Topics at this level also include communication, leadership, power and politics, and conflict.

A group consists of two or more individuals who come together to achieve a similar goal. Groups can be formal or informal. A formal group on the one hand is assigned by the organization’s management and is a component of the organization’s structure. An informal group on the other hand is not determined by the organization and often forms in response to a need for social contact. Teams are formal groups that come together to meet a specific group goal.

Although groups are thought to go through five stages of development (Tuckman, 1965 : forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning) and to transition to effectiveness at the halfway mark (Gersick, 1988 ), group effectiveness is in fact far more complex. For example, two types of conformity to group norms are possible: compliance (just going along with the group’s norms but not accepting them) and personal acceptance (when group members’ individual beliefs match group norms). Behavior in groups then falls into required behavior usually defined by the formal group and emergent behavior that grows out of interactions among group members (Champoux, 2011 ).

Group Decision-Making

Although many of the decisions made in organizations occur in groups and teams, such decisions are not necessarily optimal. Groups may have more complex knowledge and increased perspectives than individuals but may suffer from conformity pressures or domination by one or two members. Group decision-making has the potential to be affected by groupthink or group shift. In groupthink , group pressures to conform to the group norms deter the group from thinking of alternative courses of action (Janis & Mann, 1977 ). In the past, researchers attempted to explain the effects of group discussion on decision-making through the following approaches: group decision rules, interpersonal comparisons, and informational influence. Myers and Lamm ( 1976 ), however, present a conceptual schema comprised of interpersonal comparisons and informational influence approaches that focus on attitude development in a more social context. They found that their research is consistent with the group polarization hypothesis: The initial majority predicts the consensus outcome 90% of the time. The term group polarization was founded in Serge Moscovici and his colleagues’ literature (e.g., Moscovici & Zavalloni, 1969 ). Polarization refers to an increase in the extremity of the average response of the subject population.

In other words, the Myer and Lamm ( 1976 ) schema is based on the idea that four elements feed into one another: social motivation, cognitive foundation, attitude change, and action commitment. Social motivation (comparing self with others in order to be perceived favorably) feeds into cognitive foundation , which in turn feeds into attitude change and action commitment . Managers of organizations can help reduce the negative phenomena and increase the likelihood of functional groups by encouraging brainstorming or openly looking at alternatives in the process of decision-making such as the nominal group technique (which involves restricting interpersonal communication in order to encourage free thinking and proceeding to a decision in a formal and systematic fashion such as voting).

Elements of Team Performance

OB researchers typically focus on team performance and especially the factors that make teams most effective. Researchers (e.g., see De Dreu & Van Vianen, 2001 ) have organized the critical components of effective teams into three main categories: context, composition, and process. Context refers to the team’s physical and psychological environment, and in particular the factors that enable a climate of trust. Composition refers to the means whereby the abilities of each individual member can best be most effectively marshaled. Process is maximized when members have a common goal or are able to reflect and adjust the team plan (for reflexivity, see West, 1996 ).

Communication

In order to build high-performing work teams, communication is critical, especially if team conflict is to be minimized. Communication serves four main functions: control, motivation, emotional expression, and information (Scott & Mitchell, 1976 ). The communication process involves the transfer of meaning from a sender to a receiver through formal channels established by an organization and informal channels, created spontaneously and emerging out of individual choice. Communication can flow downward from managers to subordinates, upward from subordinates to managers, or between members of the same group. Meaning can be transferred from one person to another orally, through writing, or nonverbally through facial expressions and body movement. In fact, body movement and body language may complicate verbal communication and add ambiguity to the situation as does physical distance between team members.

High-performance teams tend to have some of the following characteristics: interpersonal trust, psychological and physical safety, openness to challenges and ideas, an ability to listen to other points of view, and an ability to share knowledge readily to reduce task ambiguity (Castka, Bamber, Sharp, & Belohoubek, 2001 ). Although the development of communication competence is essential for a work team to become high-performing, that communication competence is also influenced by gender, personality, ability, and emotional intelligence of the members. Ironically, it is the self-reliant team members who are often able to develop this communication competence. Although capable of working autonomously, self-reliant team members know when to ask for support from others and act interdependently.

Emotions also play a part in communicating a message or attitude to other team members. Emotional contagion, for instance, is a fascinating effect of emotions on nonverbal communication, and it is the subconscious process of sharing another person’s emotions by mimicking that team member’s nonverbal behavior (Hatfield, Cacioppo, & Rapson, 1993 ). Importantly, positive communication, expressions, and support of team members distinguished high-performing teams from low-performing ones (Bakker & Schaufeli, 2008 ).

Team Conflict

Because of member interdependence, teams are inclined to more conflict than individual workers. In particular, diversity in individual differences leads to conflict (Thomas, 1992 ; Wall & Callister, 1995 ; see also Cohen & Bailey, 1997 ). Jehn ( 1997 ) identifies three types of conflict: task, relationship, and process. Process conflict concerns how task accomplishment should proceed and who is responsible for what; task conflict focuses on the actual content and goals of the work (Robbins et al., 2014 ); and relationship conflict is based on differences in interpersonal relationships. While conflict, and especially task conflict, does have some positive benefits such as greater innovation (Tjosvold, 1997 ), it can also lead to lowered team performance and decreased job satisfaction, or even turnover. De Dreu and Van Vianen ( 2001 ) found that team conflict can result in one of three responses: (1) collaborating with others to find an acceptable solution; (2) contending and pushing one member’s perspective on others; or (3) avoiding and ignoring the problem.

Team Effectiveness and Relationship Conflict

Team effectiveness can suffer in particular from relationship conflict, which may threaten team members’ personal identities and self-esteem (Pelled, 1995 ). In this regard, Murnighan and Conlon ( 1991 ) studied members of British string quartets and found that the most successful teams avoided relationship conflict while collaborating to resolve task conflicts. This may be because relationship conflict distracts team members from the task, reducing team performance and functioning. As noted earlier, positive affect is associated with collaboration, cooperation, and problem resolution, while negative affect tends to be associated with competitive behaviors, especially during conflict (Rhoades, Arnold, & Jay, 2001 ).

Team Climate and Emotionality

Emotional climate is now recognized as important to team processes (Ashkanasy & Härtel, 2014 ), and team climate in general has important implications for how individuals behave individually and collectively to effect organizational outcomes. This idea is consistent with Druskat and Wolff’s ( 2001 ) notion that team emotional-intelligence climate can help a team manage both types of conflict (task and relationship). In Jehn’s ( 1997 ) study, she found that emotion was most often negative during team conflict, and this had a negative effect on performance and satisfaction regardless of the type of conflict team members were experiencing. High emotionality, as Jehn calls it, causes team members to lose sight of the work task and focus instead on the negative affect. Jehn noted, however, that absence of group conflict might also may block innovative ideas and stifle creativity (Jehn, 1997 ).

Power and Politics

Power and organizational politics can trigger employee conflict, thus affecting employee wellbeing, job satisfaction, and performance, in turn affecting team and organizational productivity (Vigoda, 2000 ). Because power is a function of dependency, it can often lead to unethical behavior and thus become a source of conflict. Types of power include formal and personal power. Formal power embodies coercive, reward, and legitimate power. Coercive power depends on fear. Reward power is the opposite and occurs when an individual complies because s/he receives positive benefits from acting in accordance with the person in power. In formal groups and organizations, the most easily accessed form of power is legitimate because this form comes to be from one’s position in the organizational hierarchy (Raven, 1993 ). Power tactics represent the means by which those in a position of power translate their power base (formal or personal) into specific actions.

The nine influence tactics that managers use according to Yukl and Tracey ( 1992 ) are (1) rational persuasion, (2) inspirational appeal, (3) consultation, (4) ingratiation, (5) exchange, (6) personal appeal, (7) coalition, (8) legitimating, and (9) pressure. Of these tactics, inspirational appeal, consultation, and rational persuasion were among the strategies most effective in influencing task commitment. In this study, there was also a correlation found between a manager’s rational persuasion and a subordinate rating her effectively. Perhaps this is because persuasion requires some level of expertise, although more research is needed to verify which methods are most successful. Moreover, resource dependence theory dominates much theorizing about power and organizational politics. In fact, it is one of the central themes of Pfeffer and Salancik’s ( 1973 ) treatise on the external control of organizations. First, the theory emphasizes the importance of the organizational environment in understanding the context of how decisions of power are made (see also Pfeffer & Leblebici, 1973 ). Resource dependence theory is based on the premise that some organizations have more power than others, occasioned by specifics regarding their interdependence. Pfeffer and Salancik further propose that external interdependence and internal organizational processes are related and that this relationship is mediated by power.

Organizational Politics

Political skill is the ability to use power tactics to influence others to enhance an individual’s personal objectives. In addition, a politically skilled person is able to influence another person without being detected (one reason why he or she is effective). Persons exerting political skill leave a sense of trust and sincerity with the people they interact with. An individual possessing a high level of political skill must understand the organizational culture they are exerting influence within in order to make an impression on his or her target. While some researchers suggest political behavior is a critical way to understand behavior that occurs in organizations, others simply see it as a necessary evil of work life (Champoux, 2011 ). Political behavior focuses on using power to reach a result and can be viewed as unofficial and unsanctioned behavior (Mintzberg, 1985 ). Unlike other organizational processes, political behavior involves both power and influence (Mayes & Allen, 1977 ). Moreover, because political behavior involves the use of power to influence others, it can often result in conflict.

Organizational Politics, Power, and Ethics

In concluding this section on power and politics, it is also appropriate to address the dark side, where organizational members who are persuasive and powerful enough might become prone to abuse standards of equity and justice and thereby engage in unethical behavior. An employee who takes advantage of her position of power may use deception, lying, or intimidation to advance her own interests (Champoux, 2011 ). When exploring interpersonal injustice, it is important to consider the intent of the perpetrator, as well as the effect of the perpetrator’s treatment from the victim’s point of view. Umphress, Simmons, Folger, Ren, and Bobocel ( 2013 ) found in this regard that not only does injustice perceived by the self or coworkers influence attitudes and behavior within organizations, but injustice also influences observer reactions both inside and outside of the organization.

Leadership plays an integrative part in understanding group behavior, because the leader is engaged in directing individuals toward attitudes and behaviors, hopefully also in the direction of those group members’ goals. Although there is no set of universal leadership traits, extraversion from the Big Five personality framework has been shown in meta-analytic studies to be positively correlated with transformational, while neuroticism appears to be negatively correlated (Bono & Judge, 2004 ). There are also various perspectives to leadership, including the competency perspective, which addresses the personality traits of leaders; the behavioral perspective, which addresses leader behaviors, specifically task versus people-oriented leadership; and the contingency perspective, which is based on the idea that leadership involves an interaction of personal traits and situational factors. Fiedler’s ( 1967 ) contingency, for example, suggests that leader effectiveness depends on the person’s natural fit to the situation and the leader’s score on a “least preferred coworker” scale.

More recently identified styles of leadership include transformational leadership (Bass, Avolio, & Atwater, 1996 ), charismatic leadership (Conger & Kanungo, 1988 ), and authentic leadership (Luthans & Avolio, 2003 ). In a nutshell, transformational leaders inspire followers to act based on the good of the organization; charismatic leaders project a vision and convey a new set of values; and authentic leaders convey trust and genuine sentiment.

Leader-member exchange theory (LMX; see Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995 ) assumes that leadership emerges from exchange relationships between a leader and her or his followers. More recently, Tse, Troth, and Ashkanasy ( 2015 ) expanded on LMX to include social processes (e.g., emotional intelligence, emotional labor, and discrete emotions), arguing that affect plays a large part in the leader-member relationship.

Leadership Development

An emerging new topic in leadership concerns leadership development, which embodies the readiness of leadership aspirants to change (Hannah & Avolio, 2010 ). In this regard, the learning literature suggests that intrinsic motivation is necessary in order to engage in development (see Hidi & Harackiewicz, 2000 ), but also that the individual needs to be goal-oriented and have developmental efficacy or self-confidence that s/he can successfully perform in leadership contexts.

Ashkanasy, Dasborough, and Ascough ( 2009 ) argue further that developing the affective side of leaders is important. In this case, because emotions are so pervasive within organizations, it is important that leaders learn how to manage them in order to improve team performance and interactions with employees that affect attitudes and behavior at almost every organizational level.

Abusive Leadership

Leaders, or those in positions of power, are particularly more likely to run into ethical issues, and only more recently have organizational behavior researchers considered the ethical implications of leadership. As Gallagher, Mazur, and Ashkanasy ( 2015 ) describe, since 2009 , organizations have been under increasing pressure to cut costs or “do more with less,” and this sometimes can lead to abusive supervision, whereby employee job demands exceed employee resources, and supervisors engage in bullying, undermining, victimization, or personal attacks on subordinates (Tepper, 2000 ).