Anton Chekhov

(1860-1904)

Who Was Anton Chekhov?

Through stories such as "The Steppe" and "The Lady with the Dog," and plays such as The Seagull and Uncle Vanya , Anton Chekhov emphasized the depths of human nature, the hidden significance of everyday events and the fine line between comedy and tragedy. Chekhov died of tuberculosis on July 15, 1904, in Badenweiler, Germany.

Youth and Education

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was born on January 29, 1860, in Taganrog, Russia. His father, Pavel, was a grocer with frequent money troubles; his mother, Yevgeniya, shared her love of storytelling with Chekhov and his five siblings.

When Pavel’s business failed in 1875, he took the family to Moscow to look for other work while Chekhov remained in Taganrog until he finished his studies. Chekhov finally joined his family in Moscow in 1879 and enrolled at medical school. With his father still struggling financially, Chekhov supported the family with his freelance writing, producing hundreds of short comic pieces under a pen name for local magazines.

Early Writing Career

During the mid-1880s, Chekhov practiced as a physician and began to publish serious works of fiction under his own name. His pieces appeared in the newspaper New Times and then as part of collections such as Motley Stories (1886). His story “The Steppe” was an important success, earning its author the Pushkin Prize in 1888. Like most of Chekhov’s early work, it showed the influence of the major Russian realists of the 19th century, such as Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

Chekhov also wrote works for the theater during this period. His earliest plays were short farces; however, he soon developed his signature style, which was a unique mix of comedy and tragedy. Plays such as Ivanov (1887) and The Wood Demon (1889) told stories about educated men of the upper classes coping with debt, disease and inevitable disappointment in life.

Major Works

Chekhov wrote many of his greatest works from the 1890s through the last few years of his life. In his short stories of that period, including “Ward No. 6” and “The Lady with the Dog,” he revealed a profound understanding of human nature and the ways in which ordinary events can carry deeper meaning.

In his plays of these years, Chekhov concentrated primarily on mood and characters, showing that they could be more important than the plots. Not much seems to happen to his lonely, often desperate characters, but their inner conflicts take on great significance. Their stories are very specific, painting a picture of pre-revolutionary Russian society, yet timeless.

From the late 1890s onward, Chekhov collaborated with Constantin Stanislavski and the Moscow Art Theater on productions of his plays, including his masterpieces The Seagull (1895), Uncle Vanya (1897), The Three Sisters (1901) and The Cherry Orchard (1904).

Later Life and Death

In 1901, Chekhov married Olga Knipper, an actress from the Moscow Art Theatre. However, by this point his health was in decline due to the tuberculosis that had affected him since his youth. While staying at a health resort in Badenweiler, Germany, he died in the early hours of July 15, 1904, at the age of 44.

Chekhov is considered one of the major literary figures of his time. His plays are still staged worldwide, and his overall body of work influenced important writers of an array of genres, including James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams and Henry Miller.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Anton Chekhov

- Birth Year: 1860

- Birth date: January 29, 1860

- Birth City: Taganrog

- Birth Country: Russia

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Russian writer Anton Chekhov is recognized as a master of the modern short story and a leading playwright of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- Writing and Publishing

- Astrological Sign: Aquarius

- Death Year: 1904

- Death date: July 15, 1904

- Death City: Badenweiler

- Death Country: Germany

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Anton Chekhov Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/writer/anton-chekhov

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: October 27, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- People don't notice whether it's winter or summer when they're happy.

Playwrights

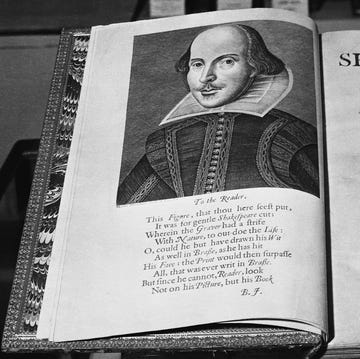

A Huge Shakespeare Mystery, Solved

How Did Shakespeare Die?

Is ‘Shakespeare in Love’ Accurate?

10 Movies & TV Shows Based on Shakespeare

Shakespeare Wrote 3 Tragedies in Turbulent Times

Was Shakespeare the Real Author of His Plays?

20 Shakespeare Quotes

William Shakespeare

Agatha Christie

Truman Capote

August Wilson

Langston Hughes

- Humanities ›

- Literature ›

- Plays & Drama ›

- Playwrights ›

Biography of Anton Chekhov

- Playwrights

- Basics & Advice

- Play & Drama Reviews

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- M.A., Literature, California State University - Northridge

- B.A., Creative Writing, California State University - Northridge

Born in 1860, Anton Chekhov grew up in the Russian town of Taganrog. He spent much of his childhood quietly sitting in his father's fledgling grocery store. He watched the customers and listened to the their gossip, their hopes, and their complaints. Early on, he learned to observe the everyday lives of humans. His ability to listen would become one of his most valuable skills as a storyteller.

Chekhov's Youth His father, Paul Chekhov, grew up in an impoverished family. Anton's grandfather was actually a serf in Czarist Russia, but through hard work and thriftiness, he purchased his family's freedom. Young Anton's father became a self-employed grocer, but the business never prospered and eventually fell apart.

Monetary woes dominated Chekhov's childhood. As a result, financial conflicts are prominent in his plays and fiction.

Despite economic hardship, Chekhov was a talented student. In 1879, he left Taganrog to attend medical school in Moscow. At this time, he felt the pressure of being the head of the household. His father was no longer earning a living. Chekhov needed a way to make money without abandoning school. Writing stories provided a solution.

He began writing humorous stories for local newspapers and journals. At first the stories paid very little. However, Chekhov was a quick and prolific humorist. By the time he was in his forth year of medical school, he had caught the attention of several editors. By 1883, his stories were earning him not only money but notoriety.

Chekhov's Literary Purpose As a writer, Chekhov did not subscribe to a particular religion or political affiliation. He wanted to satirize not preach. At the time, artists and scholars debated the purpose of literature. Some felt that literature should offer "life instructions." Others felt that art should simply exist to please. For the most part, Chekhov agreed with the latter view.

"The artist must be, not the judge of his characters and of what they say, but merely a dispassionate observer." -- Anton Chekhov

Chekhov the Playwright Because of his fondness for dialogue, Chekhov felt drawn to the theatre. His early plays such as Ivanov and The Wood Demon artistically dissatisfied him. In 1895 he began working on a rather original theatrical project: The Seagull . It was a play that defied many of the traditional elements of common stage productions. It lacked plot and it focused on many interesting yet emotionally static characters.

In 1896 The Seagull received a disastrous response on opening night. The audience actually booed during the first act. Fortunately, innovative directors Konstantin Stanislavski and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danechenko believed in Chekhov's work. Their new approach to drama invigorated audiences. The Moscow Art Theatre restaged The Seagull and created a triumphant crowd-pleaser.

Soon after, the Moscow Art Theatre, led by Stanislavski and Nemirovich-Danechenko, produced the rest of Chekhov's masterpieces:

- Uncle Vanya (1899)

- The Three Sisters (1900)

- The Cherry Orchard (1904)

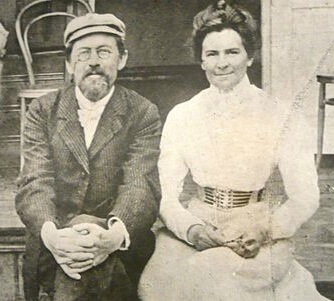

Chekhov's Love Life The Russian storyteller played with themes of romance and marriage, but throughout most of his life he did not take love seriously. He had occasional affairs, but he did not fall in love until he met Olga Knipper, an up-and-coming Russian actress. They were very discreetly married in 1901.

Olga not only starred in Chekhov's plays, she also deeply understood them. More than anyone in Chekhov's circle, she interpreted the subtle meanings within the plays. For example, Stanislavski thought The Cherry Orchard was a "tragedy of Russian life." Olga instead knew that Chekhov intended it to be a "gay comedy," one that almost touched upon farce.

Olga and Chekhov were kindred spirits, though they did not spend much time together. Their letters indicate that they were very affectionate to one another. Sadly, their marriage would not last very long, due to Chekhov's failing health.

Chekhov's Final Days At the age of 24, Chekhov began showing signs of tuberculosis. He tried to ignore this condition; however by his early 30s his health had deterorated beyond denial.

When The Cherry Orchard opened in 1904, tuberculosis had ravaged his lungs. His body was visibly weakened. Most of his friends and family knew the end was near. Opening night of The Cherry Orchard became a tribute filled with speeches and heartfelt thanks. It was their was of saying goodbye to Russia's greatest playwright.

On July 14th, 1904, Chekhov stayed up late working on yet another short story. After going to bed, he suddenly awoke and summoned a doctor. The physician could do nothing for him but offer a glass of champagne. Reportedly, his final words were, "It's a long time since I drank champagne." Then, after drinking the beverage, he died

Chekhov's Legacy During and after his lifetime, Anton Chekhov was adored throughout Russia. Aside from his beloved stories and plays, he is also remembered as a humanitarian and a philanthropist. While living in the country, he often attended to the medical needs of the local peasants. Also, he was renowned for sponsoring local writers and medical students.

His literary work has been embraced throughout the world. While many playwrights create intense, life-or-death scenarios, Chekhov's plays offer everyday conversations. Readers cherish his extraordinary insight into the lives of the ordinary.

References Malcolm, Janet, Reading Chekhov, a Critical Journey, Granta Publications, 2004 edition. Miles, Patrick (ed), Chekhov on the British Stage, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- The Best Plays of George Bernard Shaw

- Biography of Henrik Ibsen, Norwegian Playwright

- Biography of Arthur Miller, Major American Playwright

- Biography of Sam Shepard, American Playwright

- Biography of Tennessee Williams, American Playwright

- A Biography of Playwright Susan Glaspell

- Biography of Oscar Wilde, Irish Poet and Playwright

- Biography of Lillian Hellman, Playwright Who Stood Up to the HUAC

- The Life and Work of Playwright Berthold Brecht

- Fast Facts About George Bernard Shaw's Life and Plays

- Samuel French Inc.: Play Publishing Company

- Agatha Christie's Mystery Plays

- The Best of Harold Pinter's Plays

- Anton Chekhov's 'The Marriage Proposal' One-Act Play

- "The Good Doctor" by Neil Simon

- Plot Summary of "The Seagull" by Anton Chekhov

- World Biography

Anton Chekhov Biography

Born: January 17, 1860 Taganrog, Russia Died: July 2, 1904 Badenweiler, Germany Russian dramatist and author

The Russian author Anton Chekhov is among the major short-story writers and dramatists in history. He wrote seventeen plays and almost six hundred stories.

Early life in Russia

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was born in Taganrog in South Russia on the Azov Sea on January 17, 1860. He was the third of six children of Pavel Egorovich Chekhov, a grocery store owner. Chekhov's grandfather was a serf (a peasant who lives and works on land owned by another) who bought his family's freedom in 1841. The young Chekhov and his brothers and sisters worked in the family store and studied in the local school. Their extremely religious father often beat them. In 1876 his father's business failed, and the family moved to Moscow, Russia, for a fresh start. Chekhov, then sixteen, was left behind to finish his schooling.

The blond, brown-eyed Chekhov was a self-reliant, amusing, energetic, and attractive young man. In August 1879 he joined his parents in Moscow, where his father was a laborer and his mother did part-time sewing work. Chekhov immediately entered the medical school of Moscow University. He soon took his father's place as head of the household, a responsibility he carried the rest of his life. After graduating in 1884 he went to work in the hospital at Chikino, Russia, but by December of that year he had begun coughing up blood—the first symptom of the tuberculosis (an infection in the lungs) that eventually caused his death.

First works

Chekhov's first book published by someone else, Motley Stories, came out in 1886 with his real name on it. The book did well, and Chekhov was recognized as a new talent. He began practicing medicine less and writing more. In February 1887 he was elected to the Literary Fund, an honor given only to prominent authors. In the Twilight, a collection of short stories, appeared in August. Chekhov's first completed play, Ivanov, was produced in Moscow in November 1887. He stopped writing for humor magazines in favor of serious fiction and drama in an attempt to, as he stated in a letter, "depict life as it actually is."

Many successes

"The Steppe" (1888), a story of the Russian countryside revolving around the adventures of nine-year-old Egorushka while on his way to a distant town with his uncle, began a new phase in Chekhov's writing career. Not only was it accepted by the high-class Northern Messenger magazine—bringing Chekhov a considerable sum of money—but it also was highly praised by other famous writers. In October 1888 he won the Academy of Sciences' Pushkin Prize. "The Lights," "The Name-Day Party," and "An Attack of Nerves" all appeared in this year.

Chekhov spent the summer of 1888 in the Ukraine (where his brother Nikolai died) and at Yalta. The events of this period inspired "A Dreary Story" (1889), in which a dying old man thinks back on what he considers his pointless life. After another collection of stories, Children, was published in March 1889, Chekhov decided that he could now support his family by his writing alone. He wrote some one-act plays and worked on The Wood Demon, but the St. Petersburg (Russia) Theatrical Committee rejected the play, deeply wounding him. In March 1890 his seventh book, a collection of stories entitled Gloomy People, appeared. Late in April 1890 Chekhov set out for the prison colony on the Siberian island of Sakhalin. After spending three months studying the island, Chekhov returned home and wrote Sakhalin Island, which was later published in serial form.

In February 1892 Chekhov bought a 675-acre estate outside of Moscow called Melikhovo, and he settled down on it with his family. Guests streamed out to visit him. By the end of 1893 he was supporting his family comfortably. He began writing more slowly and focusing more on writing plays than before, but his stories continued to appear in the leading St. Petersburg and Moscow magazines. Chekhov was popular and admired. He had a number of pretty, lively, and talented women friends, but none whom he felt strongly enough about to propose marriage. But in 1898, when he was thirty-eight and seriously ill, he met the actress Olga Knipper, and they began an affair.

Series of famous plays

Chekhov's play The Sea Gull drew heavily on a romance between his former love Lidiya Mizinova and his writer friend I. N. Potapenko. The play had failed in its first presentation in 1896, but in 1898 in the new Moscow Art Theater it was such a spectacular success that the gull became, and remains, the theater's official emblem. Chekhov's other great plays followed quickly: Uncle Vanya, a new version of The Wood Demon, in 1897; Three Sisters in 1900–01; and The Cherry Orchard in 1903–04. They are all about the passing of the old order. In each, a group of upper-class landowners struggles to preserve their cultural values against the social change insisted on by the middle-and lower-class teachers, writers, and businessmen to whom the new life belongs.

Chekhov was at the height of his fame. He encouraged younger writers such as Ivan Bunin (1870–1953) and Leonid Andreyev (1871–1919), recommended writers for the Pushkin Prize, and was eagerly sought out for advice and comment. In 1900 he became the first writer elected to membership in the Russian Academy of Sciences, and in 1901 he and Olga Knipper were married. She acted in Moscow during the season while he stayed in Yalta to improve his health. The letters between them indicate a deep affection. Chekhov's health worsened in 1904, and his doctors told him that he had to go to a hospital. In June 1904 he set off for Badenweiler, Germany. A friend who saw him in Moscow the day before he left for Europe quoted Chekhov as having said, "Tomorrow I leave. Good-bye. I'm going away to die." On July 2, 1904, he died in a hotel at Badenweiler. His body was returned to Moscow for burial.

For More Information

Bloom, Harold, ed. Anton Chekhov. Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 1999.

Callow, Philip. Chekhov, the Hidden Ground: A Biography. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1998.

Chekov, Anton. The Undiscovered Chekhov: Thirty-Eight New Stories. New York: Seven Stories, 1999.

Rayfield, Donald. Anton Chekhov: A Life. New York: Henry Holt, 1998.

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

- Events calendar

- Account home

- Account settings

- Purchase history

- Subscription renewals

- Wish list 0

- Change language FR

Anton Tchekhov

Born on the desolate shores of the Black Sea, a simple dispensing physician at the outset, umpteenth son of a family sizzling with intense personalities: rarely in the history of literature has a writer’s self-perception been so far removed from his true genius. Despite that incongruity, Russian playwright Anton Pavlovich Chekhov penned Ivanov (1887), The Seagull (1895–96), Uncle Vanya (1897), Three Sisters (1901) and The Cherry Orchard (1904)—five masterpieces that ushered in, at the dawn of the twentieth century, a form of realism with touches of the unfamiliar and strange, interweaving comedy and tragedy in a reflection of the elusive dance of existence.

Upcoming events

Anton Chekhov

Short stories.

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (Jan 29, 1860 - Jul 15, 1904) was a Russian physician and supreme short story writer and playwright. He was the third of six children. His father was a grocer, painter and religious fanatic with a mercurial temperament who "thrashed" his children and was likely emotionally abusive to his wife. Chekhov, like Dickens , was no stranger to financial hardship and in 1875 his father took the family and fled to Moscow to escape creditors. Chekhov stayed behind for three more years to finish school. He paid for his tuition by catching and selling goldfinches and dispensing private tutoring lessons, and selling short sketches to the newspaper. He sent any money he could spare money to his family in Moscow. Chekhov is considered an exemplar author in the genre of Realism . A child-family separation theme plays out in several of Chekhov's stories including Vanka , The Steppe , and Sleepy .

"Medicine is my lawful wife and literature my mistress; when I get tired of one, I spend the night with the other."

Some consider Chekhov to be the founder of the modern short story and his influence is observed in a diverse group of writers including Flannery O'Connor , Tennessee Williams, William Somerset Maugham , Raymond Carver and John Cheever. Most of the English-speaking world knows him as a playwright, particularly for The Seagull , Uncle Vanya , Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard .

In 1897 Chekhov was diagnosed with tuberculosis. He purchased land in Yalta in 1898 after his father's death and had a villa built. He moved into the villa in 1899 with his mother and sister. This was a very prolific period for the great writer and he produced some of his most famous work during this period. Amongst those works is a trilogy featuring Ivan Ivanovitch, a veterinary surgeon and his schoolmaster friend, Burkin. The two are on a small trekking and shooting holiday. Chekhov overlays three stories that are amongst his most famous short stories in a trilogy sometimes referred to as "The Little Trilogy". The three short stories, in order, are: The Man in a Case , Gooseberries , and About Love . It was also during this period in Yalta that he produced Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard .

We feature two volumes of Anton Chekhov's great short stories in our Favorite Short Stories Collection . You may also enjoy reminiscences about Chekhov by Maxim Gorky and Aleksandr Kuprin .

Chekhov is featured in our collection of favorite Russian Writers

Anton Chekhov's Prose

A middlebury blog.

- Born on January 29, 1860 in Taganrog, Russia.

- Died (of tuberculosis) on July 15, 1904 in Germany (Aged 44)

- Practiced as a medical doctor throughout his writing career: “Medicine is my lawful wife and literature is my mistress.”

- One of the originators of early modernism in the theater and his stores emphasize the depth of the human experience

BIBLIOGRAPHY (in order of publication)

- That Worthless Fellow Platonov

- On the Harmful Effects of Tobacco

- Ivanov (maybe not a classic, but created Chekhov’s “gun rule”)

- A Marriage Proposal

- A Tragedian in Spite of Himself

- The Wedding

- The Wood Demon

- The Festivities

- The Seagull

- Uncle Vanya

- Three Sisters

- The Cherry Orchard

- “ The Death of a Government Clerk “

- “The Chameleon”

- “Oysters”

- “A Living Chronology”

- “Small Fry”

- “ The Huntsman “

- “Seargeant Prishibeyev”

- “A Gentleman Friend”

- “At the Mill”

- “Agafya”

- “Anyuta”

- “Easter Eve”

- “Grisha”

- “Misery”

- “The Chorus Girl”

- “Ivan Matveyich”

- “The Requiem”

- “Van’ka”

- “Home”

- “The Siren”

- “Kashtanka”

- “Sleepy”

- “The Bet”

- “A Dreary Story”

- “Gusev”

- “Peasant Wives”

- “In Exile”

- “Ward No. 6”

- “The Black Monk”

- “Rothschild’s Violin”

- “ The Student “

- “The Teacher of Literature”

- “Anna on the Neck”

- “Whitebrow”

- “Ariadna”

- “An Artist’s Story”

- “Peasants”

- “The Petchenyeg”

- “The Schoolmistress”

- “ The Man in a Case “

- “ Gooseberries “

- “About Love”

- “Ionych”

- “A Doctor’s Visit”

- “The Darling”

- “On Official Duty”

- “The Lady with the Dog”

- “At Christmas Time”

- “In the Ravine”

- “The Bishop”

- “Betrothed”

- An Anonymous Story

- Three Years

LATER LIFE AND DEATH

Tired from relentless writing and fading health, Chekhov went to Ukraine–and found influence to create The Steppe. He was then asked to create a play–Ivanov–and from that play Chekhov’s rule of theater was discovered:

“Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.”

Chekhov soon after became obsessed with prison reform and traveled to Sakhalin, an island north of Japan. He came to the conclusion that it is the government’s responsibility to humanely treat convicts.

Chekhov then moved to Melikhovo after purchasing a small country estate, and then ultimately moves again to Yalta after his father’s death. He married an actress–Olga Knipper–in 1901, but at that point the tuburculosis that Chekhov had had since his youth was seriously affecting his health. He died in 1904, while staying at a health resort in Germany. His death has since become a piece of literary history, as many have fictionalized it and used it as inspiration for their own writing, most famously by Raymond Carver in his short story “Errand”.

Chekhov’s plays are still staged, his works still read. He is one of the greatest writers of his time and his tremendous body of work shaped the arc of literature and still does.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

The Vast Humanity of Anton Chekhov

A new book traces chekhov’s relentless work as both a doctor and a master of the short story..

Anton Chekhov was probably the least statuesque major Russian writer of his generation. He wrote short stories rather than novels, lived modestly, and rarely boomed out complicated philosophical ideas in large valise-sized volumes, as his contemporaries, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, were wont to do. He came from peasant stock, unlike the aristocratic Turgenev; and his politics rarely got in the way of his fiction, as they sometimes did for Gorky. He was generous, intimate, hardworking, and didn’t express grandiose opinions of himself or suffer unduly from the usual Russian vices—vodka, infidelity, and gambling. But most of all, even after achieving success as a short story writer and playwright, Chekhov never quit his day job as a doctor, and continued supporting his friends and family while suffering everything from hemorrhoids and bad teeth to frequent brain-numbing depressions, phlebitis, and the long case of tuberculosis that eventually killed him at the age of 44.

Born in Taganrog in 1860, Chekhov knew the extremes of Russian life. His father was a freed serf who achieved a brief, hard-fought success as the owner of two local grocery shops before losing them both. He impressed upon Chekhov and his siblings both a respect for the world’s natural forces (he frequently beat them) and a love for music (he devotedly took them to church each week to enjoy the choirs). His mother, a far gentler creature, doesn’t show up as prominently in Chekhov’s correspondence but resides in the background as a vast, humanizing force. Chekhov’s four close-knit brothers and sister each seem to have been both talented and wild. His older brother Nikolai suffered from alcoholism and bad debts that caused him to disappear for weeks at a time, while the youthful Alexander shamed his parents by taking up residence with a married woman.

From a young age, Chekhov delighted in the company of friends and family, and rarely had a dismissive word to say about anyone. (Toward the end of his life, he even spoke kind words for his violent father, who never bothered to read his stories even after he became famous.) What distinguished both the young and middle-aged Chekhov was his continuing capacity for intensive, daily, unremitting work—whether he was studying for medical exams, writing stories and humor pieces, or pouring out correspondence filled with well-considered advice to those he loved.

He often composed his stories at home in the evenings while surrounded by friends and family, taking a few minutes off to play the piano or join in a song. As his brother Mikhail recalled of their first months living together in Moscow, “he thrived on the excitement.” Another friend recalled the continuous and often amorous clamor of young men and women as a “bacchanalia, my dear, a real bacchanalia!” Even amid his worst periods of depression, ill health, and insolvency, Chekhov never tired of company. He wrote to a cousin who moved nearby: “You will not be an infrequent guest, at least every week.… Except for Tuesday, Thursday, and sometimes on Saturdays, I’m always at home in the evenings. Come early so you can stay longer. P.S .: On Tuesdays I’m home after nine, on Thursdays only until nine, so that there is not a single day when you risk not seeing me.”

As Chekhov’s most engaging biographer, Ernest Simmons, once put it: Chekhov “loved life more than the meaning of life.” He took his pleasures small, intimate, and frequent. He was quietly magnanimous and privately monumental—the exact opposite of Tolstoy, who strode widely on the world stage but at home remained a distant, irreproachable personality, especially to his wife and children. Bob Blaisdell’s new biography, Chekhov Becomes Chekhov , is absorbing, pleasurable, and as unaffected as its subject; and while describing Chekhov’s life through close readings of his multitudinous stories and correspondence over two years—1886 to 1887—he doesn’t simply (as the title promises) explain how Chekhov came to be Chekhov but rather how impossible it was for him to become anybody else.

As Blaisdell summarizes these two tumultuous years, it feels almost as exhausting to read about Chekhov as to be him:

In 1886, the 26-year-old Moscow doctor published 112 short stories, humor pieces, and articles. In 1887, he published sixty-four short stories… and three volumes of his short stories were published. Meanwhile, three hours a day, six days a week, Dr. Chekhov treated patients in his office at his family’s residence, and also made house calls; he lived with and supported his parents and younger siblings. In the winter of 1886, he became engaged and unengaged to be married. He mentored other writers with matter-of-fact encouragement and brilliant criticism. He carried on lively, frank, funny correspondence with editors, friends, and his older brothers.… After a blue and dreary summer of 1887, he wrote a four-act play in the space of two weeks.

It wasn’t as if literature beckoned him so much as he slipped in through the back door. Chekhov’s early short comic pieces and stories appeared pseudonymously in poorly paying literary magazines such as the Petersburg-based Fragments, usually under the self-mocking byline of Antosha Checkhonte. And yet quite quickly he established an audience even while, as a doctor, he treated some of the poorest and most desperate people in Moscow.

The “study of medicine,” he wrote about those years, “had a serious impact on my literary activities … and enriched me with knowledge whose value for me as a writer only a doctor can appreciate.” Illness and death are certainly everywhere in Chekhov, and his people suffer a range of infirmities from tuberculosis and pleurisy to anemia and cancer. (Whenever a Chekhov character coughs, it bodes poorly.) But while his stories grew more serious and emotional in later years, and he began publishing in better-paying, better-regarded journals (such as the right-wing New Times, edited by Aleksei Suvorin), they always retained a comic undertone. His characters strive to achieve things—such as love, self-command, or financial success—but those efforts are made ironic in the face of a world that, while sometimes beautiful to look at, remains indurate to human happiness. And even though New Times brought Chekhov wider success, it didn’t reflect his own liberal politics. Yet this was another sign of Chekhov’s broadly accepting nature since, so far as he believed, politics (like religion) didn’t provide much of an antidote to social, or merely human, miseries.

He preferred to put his faith in art and science—and the opportunities they provided to approach human lives with calm, objective compassion. On the other hand, almost any whiff of ideology or religion worried him, and in many stories, such as “Uprooted: An Incident From my Travels,” he expresses sympathy with young people who find ways to “uproot” themselves from the religious beliefs of their families (especially those of their fathers). For him, Christianity, Judaism, nihilism, and superstition were all common spiritual drags on human life, much like the physical drags of illness, alcoholism, gambling, and despair.

Many of these early, relatively brief stories are better than one might expect, and it’s the greatest pleasure of this book that it invites us to read (or reread) such “minor” stories as “The Beggar,” in which a middle-class businessman boasts about how he reformed a poor man with “tough love” rather than handouts—only to learn that it was the kindness of a fellow servant that actually put him on the road to sustainable living. A similar dynamic drives another shortish story, “Who Was to Blame?” in which a school headmaster buys a cat to hunt the mice in his school, but the cat proves shy of mice, which the headmaster tries to correct by beating him. Eventually the headmaster throws the cat into the street, where it spends the rest of its life more terrified of mice than ever before. As the headmaster’s sympathetic nephew recounts at the end of the story, he was himself “taught” Latin by this same uncle and later grows up to find that whenever he sees a classical work, he’s haunted by the vision of his uncle’s “sallow grey face.” “I turn pale,” he confesses, “my hair stands up on my head, and, like the cat, I take to ignominious flight.”

Chekhov’s “twist in the tail” endings are never just jokes but reveal fundamental ironies of human life—such as that cruelty and force don’t teach animals (like us) how to behave but only what to fear (which is, of course, cruelty and force). In “A Work of Art,” a doctor receives a special gift from a poor client—a candelabra decorated with rude orgiastic images that he’s ashamed to display in his home, and so he “regifts” it to someone else. They “regift” it forward, and forward again, until the original client returns to the doctor with a surprise—he found a matching candelabra! Unlike O’Henry’s “Gift of the Magi,” this relay race of gift-giving doesn’t disclose a sentimental message about the selflessness of love; it reveals a fundamental human selfishness: that people don’t appreciate an act of generosity if it makes them look bad in front of their friends.

Chekhov’s early stories have often been dismissed as minor work, or a pulpish training ground that led him to write bigger, better stories, but most of them are no less complex or moving than the later ones, inhabited by the same sorts of men and women who seek (and usually fail) to achieve the same things: love, knowledge, success, freedom, and a good life. But if they’re lucky, being alive and healthy is the only true achievement they ever attain; and even then it’s with the knowledge that it won’t last.

Chekhov may have been one of the most realism-bound of all the great short story writers; he rarely tried his hand at fantastic stories or stories that verged on the supernatural (unlike Maupassant), and whenever “macabre” events occur—such as in “A Night in the Cemetery,” in which a drunk, dreaming of a post-death experience, awakens in a very real mortuary where he had passed out—the punch line of the “joke” is reality itself, which proves more terrifying than any dream. “Chekhov believed in nightmares and hallucinations,” Blaisdell notes, “but not in ghosts”

And while Chekhov’s peers wrote big books on banner-headline topics such as War and Peace, The Possessed, and Crime and Punishment, Chekhov produced the most unassumingly titled stories in modern fiction: “A Boring Story,” “A Trifle,” “A Misfortune,” “A Trivial Incident,” and so on. (His second collection was simply titled “Motley Tales,” as if it were an assembly of scruffy, mismatched mutts.) He presented his stories as small, insignificant, and forgettable; and yet within the first few sentences, each one deftly establishes who and where the main characters are, what is significant about their lives (not much), and what the weather is like—a continuum of natural forces that determines the lives of Chekhov’s characters far more than their private desires and aspirations.

In one of Chekhov’s first stories for Suvorin’s New Times, “The Witch,” the sexton of a rural church sits pondering the storm outside his house. He believes that it’s driven by the passionate desires of his errant wife, whom he envisages as possessing vast supernatural powers:

It was hard to say who was being wiped off the face of the earth, and for the sake of whose destruction nature was being churned up into such a ferment; but, judging from the unceasing malignant roar, someone was getting it very hot. A victorious force was in full chase over the fields, storming in the forest and on the church roof, battering spitefully with its fists upon the windows, raging and tearing, while something vanquished was howling and wailing.… A plaintive lament sobbed at the window, on the roof, or in the stove. It sounded not like a call for help, but like a cry of misery, a consciousness that it was too late, that there was no salvation.

When the storm forces a postman to seek protection in their home, the sexton presumes his wife has lured him there for sex. For Chekhov, all-too-human rage and passion are about as supernatural as the world ever gets.

Chekhov wrote quickly, industriously, and prodigiously during these years, and he largely did it for money. At the same time, he never dissembled about the world as he saw it, and he seemed to care as much for his fictional characters as he did for his friends and family. For him, writing had little to do with technique, plot devices, acceptable notions about politics and religion, or educating his readers. It was only about writing as quickly as possible about the world he knew. “What is there to teach?” one of his many writerly characters asks. “There is nothing to teach. Sit down and write.” Don’t waste life on theorizing about it, Chekhov said, again and again. Which is why Chekhov’s most cerebral characters are unhappy—they think too much about the things they should be doing (telling someone they love them, moving to Moscow, selling the family estate, etc.). If there is any panacea for the stress and bitterness of human life, it is only by exhausting one’s anxieties and ambitions through hard work. And working hard was something that Chekhov rarely stopped doing until he died.

These two tumultuous years chronicled by Blaisdell came to a conclusion with the production of Chekhov’s first full-length play, Ivanov, leading him to write more for the theater and less for the magazines, at which point he washed up on the happiest, most successful years of his short life. He finally had time and opportunity to write stories at whatever length he preferred, and found his way into his great novella-length stories, such as “Ward Six,” “The Duel,” “A Boring Story,” and “Three Years.”

“Among the Russians who are happily writing at the present day I am the most light-minded and least serious,” Chekhov wrote near the height of his fame as a story writer. And it was by toiling in what was considered the relatively unserious shorter forms that Chekhov must have felt free to express his monumentally small visions of life. But “light-mindedness” doesn’t do justice to the brooding and complex dispositions of his characters, who are usually too serious for their own good. They commit horrible acts when they think they’re behaving nobly, or noble acts for the most selfish of motives; they misjudge the true qualities of other people and are just as often misjudged in turn; and while they occasionally enjoy love, a nice meal, or a warm day in the sun, they never escape the knowledge that these moments can’t last.

As Blaisdell confesses in his conclusion to Chekhov Becomes Chekhov : “I have found myself in the midst of writing this biography sometimes reading Chekhov’s publication record like an accountant.” But this almost stolid intrepid reading of Chekhov’s daily productions is what makes this book so pleasurable. It’s the sort of book that dedicated readers rarely find, one that doesn’t presume to teach us about Chekhov so much as simply enjoy him. It is like reading along with a fellow lover of Chekhov, attentive to the nuances of the life behind the work and yet never absorbed by anything but Chekhov’s inexhaustible affection for the odd, brave, ridiculous, grotesque, noble, brutal, and always marvelously understandable people he knows so well.

Scott Bradfield’s most recent book is Reading Great Books in the Bathtub: Essays & Reviews 2005–2021 .

(92) 336 3216666

Anton Chekhov

Anton Chekhov is remembered as one of the leading short story writers in world literature. He is considered the founder of the modern short story and has influenced many modern writers. He is one of the major literary figures of all time. Chekhov was a playwright as well and is known in English speaking world mainly for his plays.

He was a prolific writer and produced a great bulk of quality works. In his works, he has touched the depths of nature. He has explored everyday events that make either comedy or tragedy and the hidden significance of these events. He had personal experience of hard times in his life, and this is expressed in his works.

He presented a realist depiction of life in his works. His initial plays were farces, but he changed this soon. He wrote plays that were a mix of comedy and tragedy, and this shows how life is. He knew that ordinary life is special, and the events taking place in it carry special meanings. Like some other contemporary successful fiction writers, his focus remained on character development and mood instead of plot.

He has shown the inner conflict of the characters to the world, and through this, the pre-revolution Russian society is portrayed. He goes beyond the surface, and through this, he shows the root causes of happenings.

His precision was laconic, and he describes a complex issue neatly in a few words. His short stories and plays don’t have complex plots and conclude in neat solutions. In his work, he has provided portraits of people hailing from different classes of society. These vary from the intelligentsia to the working labor in factories.

He had a non-conventional approach towards peasantry in contrast to his contemporary writers. His works can be called a panoramic study of the then Russia. Some scholars suggest that this can be even used as an accurate sociological source.

He developed internal drama in the characters’ minds, and this is the essence of his short stories. He is considered a master of psychological realism. His plays are also the subject of innovation in his corpus. He has changed the conventions of dramatic speech.

Sometimes characters stay silent for long; sometimes there are interruptions by characters in each other’s speech. Changes brought by him into drama and short stories are substantial and seminal.

Chekhov’s works proved influential for his contemporary writers because they taught the writers about the use of mood, apparent trivialities, the inaction of characters. His profession, work as a physician, has immense impacts on his writing, and the most evident manifestation is his objective style.

He followed great writers like Tolstoy and Dostoevsky in his initial days but later changed his course. Instead of having a grand stage and universal truths like them in his works, he preferred to portray the everyday life of common people.

Due to his outstanding work, Chekhov was widely hailed by readers and theatergoers. He received several distinctions, and one of them is the Academy of Sciences’ Pushkin Prize.

A Short Biography of Anton Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was born on January 29 th , 1860 in Taganrog, southern Russia. His father was Pavel Yegorovich Chekhov while his mother was Yevgeniya Morozova. He was the third of their surviving six children. His father was a former serf whose father had liberated his family by paying for their freedom. Pavel was a religious fanatic and did often beat his children and wife.

He worked as a grocer in the town where they lived and was the director of the local parish choir. His mother was a brilliant storyteller, and Chekhov inherited this talent from her. Chekhov’s childhood life wasn’t in any sense normal, but it later became the backdrop for his great works.

He was enrolled at Greek school in Taganrog and then at Taganrog Gymnasium. He remained there until the age of sixteen. His father was declared bankrupt in 1876 due to the spending of finances on building their house. He fled their native town to avoid being imprisoned by the debtor. They settled in Moscow while Chekhov remained in the town.

He continued his education and joined them when his education at Gymnasium completed. He remained there with a fake name and worked to pay for his education. He also maintained love affairs with different women during this period, and one was with the wife of a teacher.

He was admitted to I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University in 1879, and then he joined his family in Moscow. He had well-read classic writers during his stay at Gymnasium, and he used it now to earn a livelihood for his family. He wrote comic sketches and sold them to help his family and continue his studies.

He wrote these with different pseudonyms and became a famous chronicler of Russian street life, satirizing it. He completed his medical education in 1884 and qualified as a physician. He made it his principal profession and used the income to support his family.

He had contracted tuberculosis from a patient and worsened in 1886. Though he noticed blood in his cough, he didn’t admit it to his family. By this time, he had earned enough money that could meet the financial needs of his family. He looked for better accommodation and changed houses. He joined the famous paper New Times in 1886 as a writer.

The owner of this paper, Alexey Suvorin, was a millionaire and remained Chekhov’s best friend for long. He visited Sakhalin in 1890 and wrote a reportage of his journey and the conditions of the inhabitants of the island.

In 1892 he bought an estate in Melikhovo and started spending his time managing it. During this period he continued his medical practice and had first-hand experience of Russian life. He suffered a hemorrhage in his lungs and was diagnosed with tuberculosis. He then moved to Yalta with his family and built a villa there for residence. He met Olga Knipper in 1903 and married her quietly.

They didn’t have any children and lived apart for most of the time. Chekhov fell terminally ill from tuberculosis in May 1904. He left for the German spa town of Badenweiler with his wife where he showed signs of recovery but died on July 15 th , 1904. His body was brought back to Russia for burial.

Anton Chekhov’s Writing Style

Chekhov was interested in writing about the ordinary lives and their interests in rural Russia. He has employed a number of techniques in his works. These include words and their pacing that portray the images in a reader’s mind, the creation of round characters and their moods, etc. He built a new literary form which many of his contemporaries called impressionistically.

His works lack lengthy verbiage and this he advised other writers as well. He was totally objective about his characters and provided truthful descriptions of objects and characters in his works. Brevity is characteristic of Chekhov’s work. He has fled stereotypes and used original characters.

He is essentially a dramatist, and this is evident even in his short stories. Like his plays, in which action is subtle and ineluctable, his stories have the same dramatic features. His characters have individuality and their own way of speaking. His language doesn’t have raciness and verve. For this reason, his work is easy to translate. There are exceptions to it, which include occasional catchwords, allusions, and technical terms.

There are incidental passages and details in his works which are not primarily related to the main theme. This incidental is the key feature of his writings. This is used to point to the broad context, open to discussion. Though it looks incidental, it is a source to look at the deeper meaning of the text.

Re-examination of Objective Point of View: Variations

Chekhov’s short stories are known for their objective point of view. They are made to appear as if these are snapshots from real life. They are written in the manner that there doesn’t appear any relationship between the reader and the characters. His works seem to lack any meddling, opinionated narrator who describes events from his ‘biased’ point of view.

These stories appear so that the narrator seems muted and in some cases, non-existent. In his short stories, A Trifle From Life and The Bet, there are narrators who are in disagreement with the protagonist. These stories are written from a particular moral perspective. Most often, Chekhov’s protagonists and narrators disagree.

Most of the readers think that The Bet is written from the banker’s point of view. Though this narrative doesn’t sympathize with the banker. In this story, the narrator’s stance is ironic though subtle. The more closely the narrative voice is examined, the more it becomes a blunt object, and we come to know how the narrator perceives the banker.

In Trifle, the author is inclined towards a dramatic narrative, and the story is written in dialogue. There is almost no narrator seen, and the readers feel if there is none. This short story is an example focused, objective narrative. In the first and final paragraphs, the narrator is given the opportunity to express himself.

From these paragraphs, it is apparent that the narrator is a third-person voice and refers to the protagonist as ‘my hero.’ The story seems to be narrated from the protagonist’s perspective, and the readers feel sympathy for him.

Later, when the story develops, and his actions are revealed, it is evident that the narrator’s reference to him was sarcastic. The tone is ironic in the end, and that shows the development from innocence to experience and loss of innocence.

Anton Chekhov was a lyrical playwright. He is the master of lyricism not only in the traditional sense where the writer touches the strings of the human soul. In a non-traditional sense, he is direct and precise. Like famous writers Goethe, Pushkin, and Byron, he was the master of representation of profundity in human reflection. He was an introspective writer.

This lyricism is related to reflections on his own life and his own situation in literature. An example is his play, The Cherry Orchard, and the reason for its lyricism lies in the fact that it has never been looked at from a single point of view. Another example is the Seagull, where the characters Trigorin and Treplev are the mirrors of Chekhov’s self-image.

The argument between these two characters represents the argument that is going on in Chekhov’s mind.

Modernist Short Story

Chekhov gave the short story a new literary form and set the aesthetic criteria for the short story. His short stories are marked by plotless-ness and the lack of conventional narrative organization. His fiction has the interrogative quality, and it questions even its own existence. His narratives advance towards irresolution and in some cases even misapprehension. His short stories resist the Victorian narrative convention.

His short stories resist being miniaturized novel form. His inconclusiveness and abandoning of formal closure make the reader melancholy. Through this, in conclusion, the meaning is multiplied. The brevity of his short stories leads to the co-productive capacity of the reader.

In the new kind of short story, the transaction between the reader and writer is decreased. The writer is free from the obligation to provide interpretative content. He uses the technique of creating an inner reality while focusing on outer details. The interrogative effect is achieved by the infiltration of character interiority. An example is his short story, The Bishop .

In this short story, the omniscient narrative is suppressed for a perspective filtered through a character. The essence of his realism was the personality that he refined and described in full detail.

The Paradox of Melancholy: Medical Subtext

In Chekhov’s novella A Boring Story, the fictional author is a professor of physiology, and he believes that he has symptoms of a disease and that will kill him. He believes that he has undergone changes in his personality with the onset of this disease. The plot of the novella is structured around the novel and uncharacteristic pessimism which leads to the protagonist’s search for identity.

There are several reasons for the change in his personality, which include illness, new insight, and the world around him. He deeply considers the questions which are behind his illness and how he can treat himself. This all is done from the medical point of view and shows the insight of the narrator.

He deals as either the symptoms of an illness or the actual problem that is lack of meaning in life. He believes that if these are not symptoms, then the sixty-two years of life he has lived is wasted. From this second view, some critics have inferred that Chekhov is the poet of hopelessness. This thinking also has traces of existential thinking.

Though the medical subtext is not directly visible in this novel, psychopathology plays a significant role in developing the argument of the novel. There are a lot of signs and symptoms, but the professor is unable to unite them to form a coherent picture. Thus these appear to be incidental and disconnected.

Two-timing Time

Chekhov’s play Three Sisters uses quotations that have more value than just being referential. This has subversive and even a destabilizing effect on the narrative. Here quotation is used as a device. Applying Derrida’s understanding of repetition it is clear that no two repetitions can have the same meaning.

From this, it can be inferred that the conclusion of the short story conveys the message that memory deceives and is often fallible. The same is the case with time in this play. There are various references to time in the text. From there, it can be inferred that these plays create a link between the plays and the author’s time.

This also links the characters’ responses to time. The aspect of the play goes beyond the fictional and functional levels. Though it may not present the philosophy of time, it may be at least a critique of existing concepts relevant to the time. Apart from the devices which are implied in this work, there is a discourse weaved around time. These include the ticking of the clock, the verbal device of the quotation, and the clock smashed on stage, etc.

There are references to the birth of children, change of seasons which add to the description. Chekhov tries to make the point that discussions about the future are futile. He allows the characters to either dwell in the past or future. This shows the dilemma of the instability and ever-changing nature of the present.

Works Of Anton Chekhov

Short stories.

- The Huntsman

- The Cherry Orchard

Biography of Anton Chekhov

Anton Chekhov was a Russian playwright, a writer of short stories, and one of the most prominent dramatists in theater history. He was born in Taganrog, a bustling port in southern Russia. The third of six children, his family was once serfs, but his grandfather managed to purchase their freedom. Only a year after Chekhov's birth, Russian peasants were emancipated and the feudal system was abolished. Still, Chekhov was weighed down by the class status of his family. His father was a merchant and was often physically abusive to his family. Eventually, his father went bankrupt, and Anton became financially responsible for his family. He wrote vignettes about Russian street life to support himself while also pursuing a medical degree. At the time, Russia was so socially stratified that there were no successful writers of his class; Chekhov became the only great Russian writer of the 19th century from the peasant class.

In 1887, Chekhov was commissioned to write a play, Ivanov . In 1895, he wrote The Seagull , which was a failure: after it ended, the audience booed, and Chekhov renounced theater. In 1898, however, the play was revived by Stanislavski's Moscow Art Theatre to great critical acclaim. This launched Chekhov's career as a playwright, and Stanislavski would go on to produce Chekhov's Uncle Vanya , Three Sisters , and The Cherry Orchard .

In 1901, Chekhov married Russian actress Olga Knipper, who had acted in many of his plays in Moscow. Their marriage lasted only three years: Chekhov died of tuberculosis in 1904. That same year, his final play, The Cherry Orchard, premiered to great acclaim. Posthumously, Chekhov became a Russian literary celebrity on par with Tolstoy, who was a friend and admirer. Gradually, Chekhov became popular elsewhere. In the United States, his popularity is linked to the trend of Stanislavski's school of method acting becoming more popular in the 20th century. There, Chekhov's approach to psychology and drama greatly influenced the work of many theater practitioners, including Clifford Odets, Lee Strasberg, and actors like Marlon Brando. He also influenced non-dramatic writers, such as Raymond Carver and William Boyd.

Study Guides on Works by Anton Chekhov

Agafya anton chekhov.

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was born in Russia in 1860. He initially wanted to study Medicine but he later also began a career as an author. He died in 1904 in Germany after being diagnosed with tuberculosis. Agafya focuses on the story of Savka, a...

- Study Guide

The Bet Anton Chekhov

"The Bet" is a short story by Anton Pavlovich Chekov, written in 1889. It centers on a bet that is made one night between a banker and a young lawyer at a party of intellectuals. The banker, a successful millionaire and gambler bets the lawyer...

The Black Monk Anton Chekhov

"The Black Monk” belongs to that lush category of fiction which is said to have been inspired by the dreams of the author. The nature of remembering dreams being what it is, one should take any assertion on this subject with a grain of salt. This...

Chekhov's Short Stories Anton Chekhov

Anton Chekhov was a Russian playwright and short story writer of the nineteenth century. He was born during 1860 in Russia and died during 1904 in Germany. Chekhov possessed rather simplistic yet commendable literary talent as his top plays and...

The Cherry Orchard Anton Chekhov

The nineteenth century offered two important developments to Russia which are manifested in the play. In the 1830's, the railroads arrived, an important step in Russia's move into a more international sphere. More importantly, in February of 1861,...

- Lesson Plan

The Darling Anton Chekhov

"The Darling" is a short story by Anton Chekhov, written in December 1898. First published in The Family magazine, it was ultimately included in the nine volume of Chekhov's work, released by book publisher Adolph Marx. The story draws from...

The Death of a Government Clerk Anton Chekhov

"The Death of a Government Clerk" is a short story by Anton Chekhov. It was first published in "Fragments" in 1883 with the subtitle "The Incident." It was later included in the collection "Motley Stories" in 1886.

The story details an incident...

The Lady With the Dog Anton Chekhov

"The Lady with the Dog" was written in 1899 by Russian writer and playwright Anton Chekhov, and was first published in the journal Russian Idea. It has often been deemed by critics to be Chekhov's answer to Anna Karenina; Lyudmila Parts calls it...

The Malefactor Anton Chekhov

Technically, the title of this story by Anton Chekhov usually carries the indefinite article rather than the definite, thus making it a story about “A Malefactor” rather than “The Malefactor.” Since there are only two major characters at play,...

The Seagull Anton Chekhov

“A comedy – three f., six m., four acts, rural scenery (a view over a lake); much talk of literature, little action, five bushels of love.”

One month before Chekhov finished writing The Seagull , this is the synopsis he offered to Suvorin, a rich...

Three Sisters Anton Chekhov

Three Sisters is a play written by Anton Chekhov in 1900. It follows the lives of the Prozorov sisters as their fortune is in decline and they must seek out a happy life against the odds. The play traces various human disappointments, specifically...

Uncle Vanya Anton Chekhov

Uncle Vanya, Scenes of Country Life in Four Acts (1897) is one of Russian playwright Anton Chekov’s most notable dramas and a mainstay of the theater. The play is set at the estate of the first wife of Professor Serebryakov, where he and his...

Vanka Anton Chekhov

Anton Chekhov devoted several of his stories to the lives of ordinary people; in some famous cases, he focused specifically on unknown, obscure, and miserable individuals. One such poignant work is "Vanka," the story of a lonely peasant boy who...

Anton Chekhov

- Born January 29 , 1860 · Taganrog, Russian Empire [now Rostov Oblast, Russia]

- Died July 15 , 1904 · Badenweiler, Baden, Germany (complications from lung tuberculosis)

- Birth name Anton Pavlovich Chekhov

- Antosha Chekhonte

- Height 6′ 1¼″ (1.86 m)

- Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was born in 1860, the third of six children to a family of a grocer, in Taganrog, Russia, a southern seaport and resort on the Azov Sea. His father, a 3rd-rank Member of the Merchant's Guild, was a religious fanatic and a tyrant who used his children as slaves. Young Chekhov was a part-time assistant in his father's business and also a singer in a church choir. At age 15, he was abandoned by his bankrupt father and lived alone for 3 years while finishing the Classical Gymnazium in Taganrog. Chekhov obtained a scholarship at the Moscow University Medical School in 1879, from which he graduated in 1884 as a Medical Doctor. He practiced general medicine for about ten years. While a student, Chekhov published numerous short stories and humorous sketches under a pseudonym. He reserved his real name for serious medical publications, saying "medicine is my wife; literature - a mistress." While a doctor, he kept writing and had success with his first books, and his first play "Ivanov." He gradually decreased his medical practice in favor of writing. Chekhov created his own style based on objectivity, brevity, originality, and compassion. It was different from the mainstream Russian literature's scrupulous analytical depiction of "heroes." Chekhov used a delicate fabric of hints, subtle nuances in dialogs, and precise details. He described his original style as an "objective manner of writing." He avoided stereotyping and instructive political messages in favor of cool comic irony. Praised by writers Lev Tolstoy and Nikolai Leskov , he was awarded the Pushkin Prize from the Russian Academy of Sciences in 1888. In 1890, Chekhov made a lengthy journey to Siberia and to the remote prison-island of Sakhalin. There, he surveyed thousands of convicts and conducted research for a dissertation about the life of prisoners. His research grew bigger than a dissertation, and in 1894, he published a detailed social-analytical essay on the Russian penitentiary system in Siberia and the Far East, titled "Island of Sakhalin." Chekhov's valuable research was later used and quoted by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in his "Gulag Archipelago." In 1897-1899, Chekhov returned to his medical practice in order to stop the epidemic of cholera. Chekhov developed special relationship with Stanislavsky and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko at the Moscow Art Theater. He emerged as a mature playwright who influenced the modern theater. In the plays "Uncle Vanya," "Three Sisters," "Seagull," and "Cherry Orchard," he mastered the use of understatement, anticlimax, and implied emotion. The leading actress of the Moscow Art Theater, Olga Knipper-Chekhova , became his wife. In 1898, Chekhov moved to his Mediterranean-style home at the Black Sea resort of Yalta in the Crimea. There he was visited by writers Lev Tolstoy , Maxim Gorky , Ivan Bunin , and artists Konstantin Korovin and Isaac Levitan. - IMDb Mini Biography By: Steve Shelokhonov

- Spouse Olga Knipper-Chekhova (May 25, 1901 - July 15, 1904) (his death)

- Uncle of Olga Tschechowa and Michael Chekhov .

- His drama, Uncle Vanya performed at the Donmar Warehouse, was awarded the 2003 Laurence Olivier Theatre Award for Best Revival of 2002.

- When an actor has money he doesn't send letters, he sends telegrams.

- Love, friendship, respect, do not unite people as much as a common hatred of something.

- The personal life of every individual is based on secrecy, and perhaps it is partly for that reason that civilized man is so nervously anxious that personal privacy should be respected.

- If a lot of cures are suggested for a disease, it means the disease is incurable.

- A woman can become a man's friend only in the following stages: first an acquaintance, then a mistress, and only then a friend.

Contribute to this page

- Learn more about contributing

More from this person

- View agent, publicist, legal and company contact details on IMDbPro

More to explore

Recently viewed.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Anton Chekhov (born January 29 [January 17, Old Style], 1860, Taganrog, Russia—died July 14/15 [July 1/2], 1904, Badenweiler, Germany) was a Russian playwright and master of the modern short story.He was a literary artist of laconic precision who probed below the surface of life, laying bare the secret motives of his characters. Chekhov's best plays and short stories lack complex plots and ...

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov [a] (/ ˈ tʃ ɛ k ɒ f /; [3] Russian: Антон Павлович Чехов [b], IPA: [ɐnˈton ˈpavləvʲɪtɕ ˈtɕexəf]; 29 January 1860 [c] - 15 July 1904 [d]) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer. His career as a playwright produced four classics, and his best short stories are held in high esteem ...

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was born on January 29, 1860, in Taganrog, Russia. His father, Pavel, was a grocer with frequent money troubles; his mother, Yevgeniya, shared her love of storytelling with ...

Chekhov the Playwright Because of his fondness for dialogue, Chekhov felt drawn to the theatre. His early plays such as Ivanov and The Wood Demon artistically dissatisfied him. In 1895 he began working on a rather original theatrical project: The Seagull.It was a play that defied many of the traditional elements of common stage productions.

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was born in Taganrog in South Russia on the Azov Sea on January 17, 1860. He was the third of six children of Pavel Egorovich Chekhov, a grocery store owner. Chekhov's grandfather was a serf (a peasant who lives and works on land owned by another) who bought his family's freedom in 1841.

Anton Chekhov, (born Jan. 29, 1860, Taganrog, Russia—died July 14/15, 1904, Badenweiler, Ger.), Russian playwright and short-story writer.The son of a former serf, he supported his family by writing popular comic sketches while studying medicine in Moscow. While practicing as a doctor, he had his first full-length play, Ivanov (1887), produced, but it was not well-received.

CHEKHOV, ANTON. CHEKHOV, ANTON (1860-1904), Russian playwright and short story writer. Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was born in Taganrog, Russia, on 29 January (17 January, old style) 1860, the grandson of an emancipated serf. His father failed as owner of a small shop; to escape his creditors, he fled to Moscow. Chekhov was left on his own to ...

Anton Chekhov was born on January 29, 1860, in a small port town on the Sea of Azov in the Crimea. His grandfather was a former slave who bought his own freedom.

Despite that incongruity, Russian playwright Anton Pavlovich Chekhov penned Ivanov (1887), The Seagull (1895-96), Uncle Vanya (1897), Three Sisters (1901) and The Cherry Orchard (1904)—five masterpieces that ushered in, at the dawn of the twentieth century, a form of realism with touches of the unfamiliar and strange, interweaving comedy ...

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (Jan 29, 1860 - Jul 15, 1904) was a Russian physician and supreme short story writer and playwright. He was the third of six children. His father was a grocer, painter and religious fanatic with a mercurial temperament who "thrashed" his children and was likely emotionally abusive to his wife.

"Biography Part II" Anton Pavlovich Chekhov, considered the father of the modern short story and of the modern play, was born, the third of six children, in the Russian seaport town of Taganrog, near the Black Sea. Son of a grocer and grandson of a serf who had bought his family's freedom before emancipation, Chekhov was well-acquainted with ...

The third of six children, Chekhov was born unto a struggling grocer living on a southern sea port in Russia. An ultra-Orthodox Christian and physically abusive, Pavel-Chekhov's father-modeled the hypocritical nature of man that Chekhov wrote about. He described his childhood as "suffering" and later became an atheist.

Anton Chekhov was probably the least statuesque major Russian writer of his generation. He wrote short stories rather than novels, lived modestly, and rarely boomed out complicated philosophical ...

Anton Chekhov is remembered as one of the leading short story writers in world literature. He is considered the founder of the modern short story and has influenced many modern writers. He is one of the major literary figures of all time. Chekhov was a playwright as well and is known in English speaking world mainly for his plays.

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was born on 29 January 1860 in the port town of Taganrog (at the northern tip of the Black Sea between Ukraine and Russia) in Rostov Oblast, Southern Russia, the third of six children born to Yevgenia Yakovlevna Morozov, daughter of a well-traveled cloth merchant and Pavel Yegorovitch (1825-1898), a grocer.

Biography of Anton Chekhov. Anton Chekhov was a Russian playwright, a writer of short stories, and one of the most prominent dramatists in theater history. He was born in Taganrog, a bustling port in southern Russia. The third of six children, his family was once serfs, but his grandfather managed to purchase their freedom. Only a year after ...

Anton Chekhov. Writer: Winter Sleep. Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was born in 1860, the third of six children to a family of a grocer, in Taganrog, Russia, a southern seaport and resort on the Azov Sea. His father, a 3rd-rank Member of the Merchant's Guild, was a religious fanatic and a tyrant who used his children as slaves. Young Chekhov was a part-time assistant in his father's business and also ...

The Life and Letters of Anton Tchekov. Translated and Edited by S.S. Koteliansky and Philip Tomlinson. New York. 1925. The Personal Papers of Anton Chekhov. Introduction by Matthew Josephson. New York. 1948. The Selected Letters of Anton Chekhov. Edited by Lillian Hellman and translated by Sidonie Lederer. New York. 1955. ISBN -374-51838-6.

The "Chekhov's Gun" literary technique, popularized by Anton Chekhov, emphasizes the importance of every element in a story serving a purpose. It suggests that if a gun is introduced in the first act, it must be fired by the end. This approach highlights Chekhov's economy of storytelling and avoidance of unnecessary details.

Die Anton Chekhov (russisch Антон Чехов, dt. Transkription: Anton Tschechow) ist das erste Flusskreuzfahrtschiff der Anton Chekhov-Klasse, Projekt Q-056, [3] das im Jahr 1978 unter der Baunummer 713 auf der Österreichischen Schiffswerften AG Linz in Korneuburg/Österreich gebaut und am 30. Juni 1978 im Hafen Galați in Rumänien an den Auftraggeber, Wsessojusnoje objedinenije ...

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (en ruso: Антон Павлович Чехов), nado en Taganrog o 29 de xaneiro de 1860 e finado en Badenweiler o 14 ou 15 de xullo de 1904, foi un famoso escritor ruso, un dramaturgo e un mestre do conto moderno [1] considerado un dos máis grandes escritores de todos os tempos. A súa carreira como dramaturgo produciu catro clásicos, e os seus mellores relatos ...

Anton Pavloviç Çehov (Rusça: Анто́н Па́влович Че́хов, Rusça telaffuz: [ɐnˈton ˈpavɫəvʲɪtɕ ˈtɕɛxəf]; 29 Ocak 1860 - 15 Temmuz 1904), Rus oyun ve kısa öykü yazarıdır.Tarihte kısa öykü alanında en iyi yazarlar arasında sayılmaktadır. Oyun yazarı olarak kariyerinde dört klasik eser üretmiş ve en iyi kısa öyküleri, yazarlar ve eleştirmenler ...

Anton Viktorovich Yelchin (Russian: Антон Викторович Ельчин, IPA: [ɐnˈton ˈvʲiktərəvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtɕɪn]; March 11, 1989 - June 19, 2016) was an American actor.Born in the Soviet Union to a Russian Jewish family, he immigrated to the United States with his parents at the age of six months. He began his career as a child actor, appearing as the lead of the mystery ...

Anton Pavlovici Cehov (în rusă Анто́н Па́влович Че́хов; n. 17/29 ianuarie 1860, Taganrog, Imperiul Rus - d. 15 iulie 1904, Badenweiler, Imperiul German) a fost un medic, prozator și dramaturg rus.. De peste o sută de ani spectacole după piesele sale sunt prezente, practic, în fiecare stagiune pe afișele teatrelor din România.