Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Common Assignments: Literature Review Matrix

Literature review matrix.

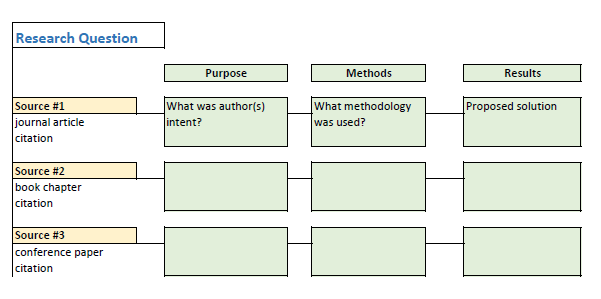

As you read and evaluate your literature there are several different ways to organize your research. Courtesy of Dr. Gary Burkholder in the School of Psychology, these sample matrices are one option to help organize your articles. These documents allow you to compile details about your sources, such as the foundational theories, methodologies, and conclusions; begin to note similarities among the authors; and retrieve citation information for easy insertion within a document.

You can review the sample matrixes to see a completed form or download the blank matrix for your own use.

- Literature Review Matrix 1 This PDF file provides a sample literature review matrix.

- Literature Review Matrix 2 This PDF file provides a sample literature review matrix.

- Literature Review Matrix Template (Word)

- Literature Review Matrix Template (Excel)

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Commentary Versus Opinion

- Next Page: Professional Development Plans (PDPs)

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- Linguistics

- Composition Studies

Five tips for developing useful literature summary tables for writing review articles

- Evidence-Based Nursing 24(2)

- Memorial University of Newfoundland

- The University of Sheffield

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Heart Lung Circ

- Alyne Santos Borges

- Paola Pugian Jardim

- Creativ Nurs

- Richard Booth

- Pearse McCusker

- Hamzah Shahid Rafiq

- Bethany Jackson

- Esther Weir

- Jonathan Mead

- Maryanna Cruz da Costa e Silva Andrade

- Juliana de Melo Vellozo Pereira Tinoco

- Isabelle Andrade Silveira

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved October 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Research Guides

- Vanderbilt University Libraries

- Peabody Library

Literature Reviews

Literature review table.

- Steps to Success: The Literature Review Process

- Literature Reviews Webinar Recording

- Writing Like an Academic

- Publishing in Academic Journals

- Managing Citations This link opens in a new window

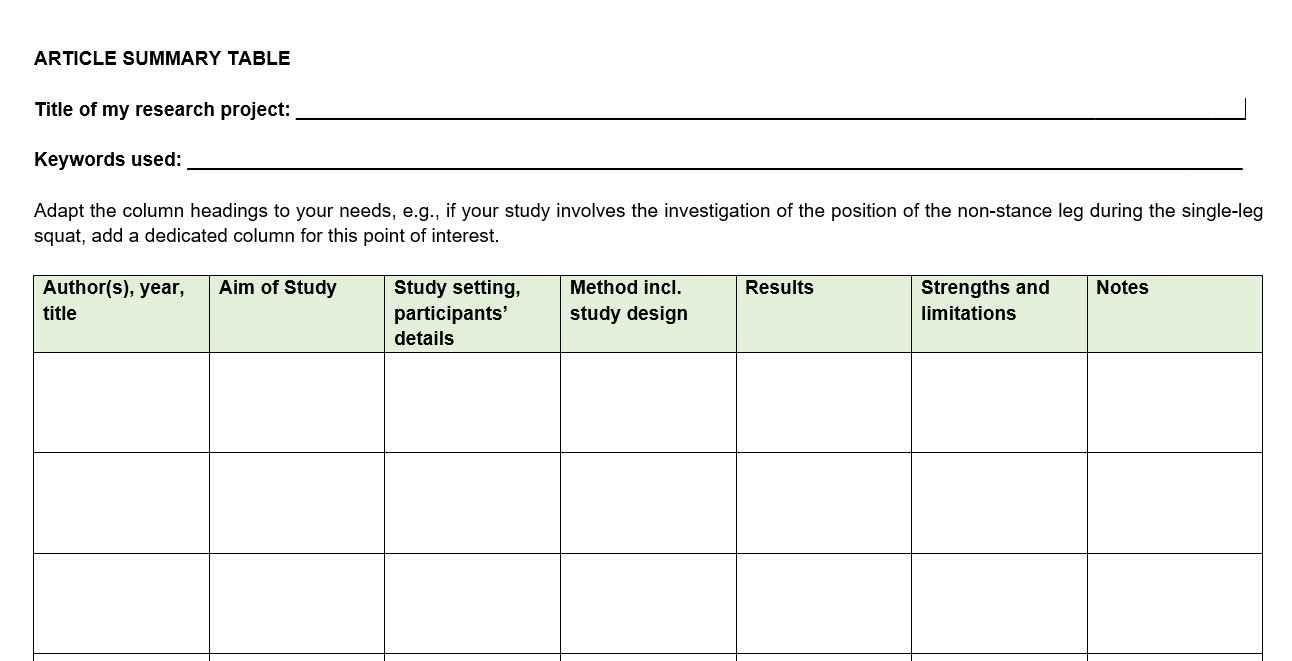

- Literature Review Table Template Peabody Librarians have created a sample literature review table to use to organize your research. Feel free to download this file and use or adapt as needed.

- << Previous: Literature Reviews Webinar Recording

- Next: Writing Like an Academic >>

- Last Updated: Oct 1, 2024 12:43 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.vanderbilt.edu/peabody/litreviews

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Writing a Literature Review

Hundreds of original investigation research articles on health science topics are published each year. It is becoming harder and harder to keep on top of all new findings in a topic area and – more importantly – to work out how they all fit together to determine our current understanding of a topic. This is where literature reviews come in.

In this chapter, we explain what a literature review is and outline the stages involved in writing one. We also provide practical tips on how to communicate the results of a review of current literature on a topic in the format of a literature review.

7.1 What is a literature review?

Literature reviews provide a synthesis and evaluation of the existing literature on a particular topic with the aim of gaining a new, deeper understanding of the topic.

Published literature reviews are typically written by scientists who are experts in that particular area of science. Usually, they will be widely published as authors of their own original work, making them highly qualified to author a literature review.

However, literature reviews are still subject to peer review before being published. Literature reviews provide an important bridge between the expert scientific community and many other communities, such as science journalists, teachers, and medical and allied health professionals. When the most up-to-date knowledge reaches such audiences, it is more likely that this information will find its way to the general public. When this happens, – the ultimate good of science can be realised.

A literature review is structured differently from an original research article. It is developed based on themes, rather than stages of the scientific method.

In the article Ten simple rules for writing a literature review , Marco Pautasso explains the importance of literature reviews:

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications. For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively. Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests. Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read. For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way (Pautasso, 2013, para. 1).

An example of a literature review is shown in Figure 7.1.

Video 7.1: What is a literature review? [2 mins, 11 secs]

Watch this video created by Steely Library at Northern Kentucky Library called ‘ What is a literature review? Note: Closed captions are available by clicking on the CC button below.

Examples of published literature reviews

- Strength training alone, exercise therapy alone, and exercise therapy with passive manual mobilisation each reduce pain and disability in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review

- Traveler’s diarrhea: a clinical review

- Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology

7.2 Steps of writing a literature review

Writing a literature review is a very challenging task. Figure 7.2 summarises the steps of writing a literature review. Depending on why you are writing your literature review, you may be given a topic area, or may choose a topic that particularly interests you or is related to a research project that you wish to undertake.

Chapter 6 provides instructions on finding scientific literature that would form the basis for your literature review.

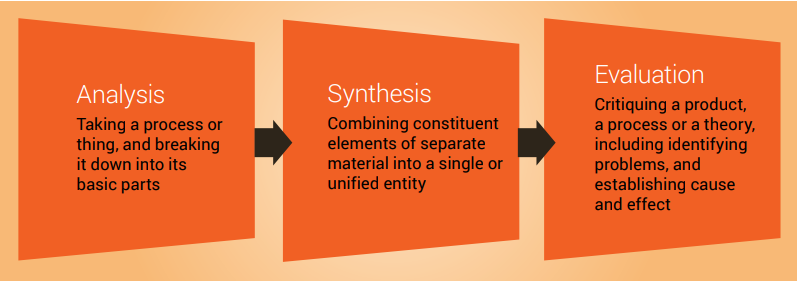

Once you have your topic and have accessed the literature, the next stages (analysis, synthesis and evaluation) are challenging. Next, we look at these important cognitive skills student scientists will need to develop and employ to successfully write a literature review, and provide some guidance for navigating these stages.

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation are three essential skills required by scientists and you will need to develop these skills if you are to write a good literature review ( Figure 7.3 ). These important cognitive skills are discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.

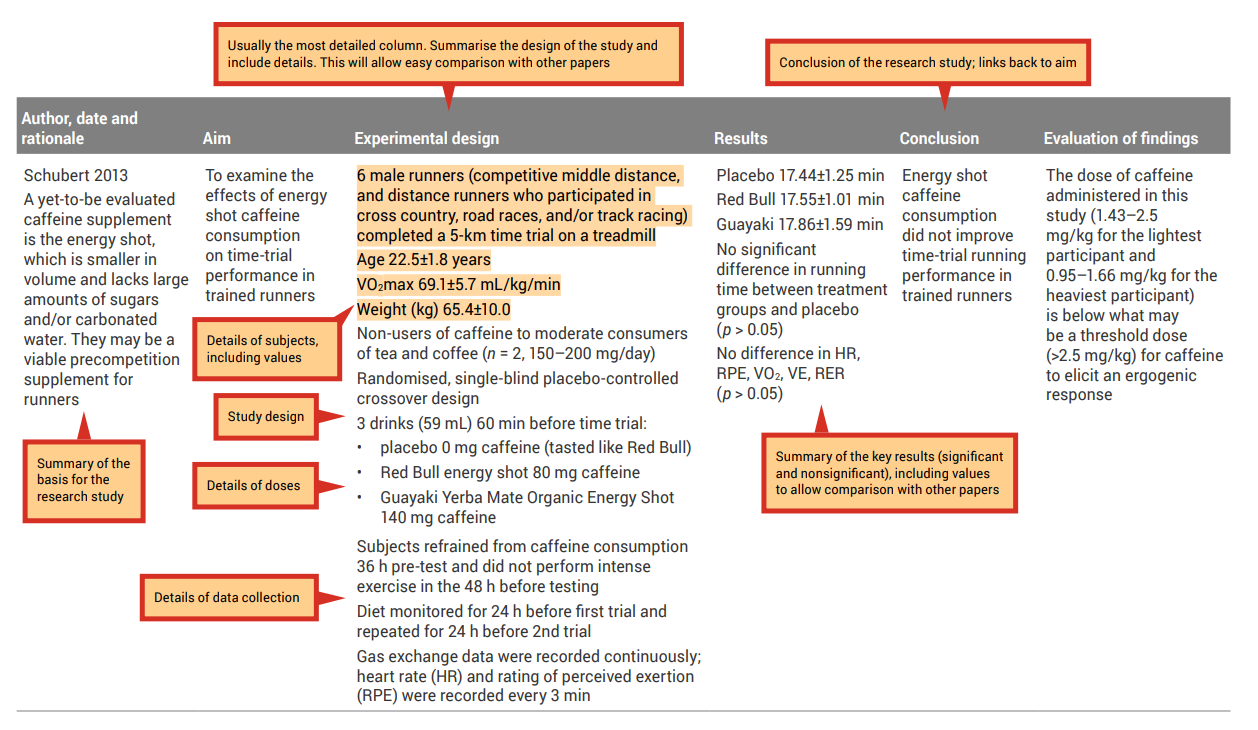

The first step in writing a literature review is to analyse the original investigation research papers that you have gathered related to your topic.

Analysis requires examining the papers methodically and in detail, so you can understand and interpret aspects of the study described in each research article.

An analysis grid is a simple tool you can use to help with the careful examination and breakdown of each paper. This tool will allow you to create a concise summary of each research paper; see Table 7.1 for an example of an analysis grid. When filling in the grid, the aim is to draw out key aspects of each research paper. Use a different row for each paper, and a different column for each aspect of the paper ( Tables 7.2 and 7.3 show how completed analysis grid may look).

Before completing your own grid, look at these examples and note the types of information that have been included, as well as the level of detail. Completing an analysis grid with a sufficient level of detail will help you to complete the synthesis and evaluation stages effectively. This grid will allow you to more easily observe similarities and differences across the findings of the research papers and to identify possible explanations (e.g., differences in methodologies employed) for observed differences between the findings of different research papers.

Table 7.1: Example of an analysis grid

| [include details about the authors, date of publication and the rationale for the review] | [summarise the aim of the experiment] | [summarise the experiment design, include the subjects used and experimental groups] | [summarise the main findings] | [summarise the conclusion] | [evaluate the paper’s findings, and highlight any terms or physiology concepts that you are unfamiliar with and should be included in your review] |

Table 7.3: Sample filled-in analysis grid for research article by Ping and colleagues

| Ping 2010 The effect of chronic caffeine supplementation on endurance performance has been studied extensively in different populations. However, concurrent research on the effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance exercise in hot and humid conditions is unavailable | To determine the effect of caffeine supplementation on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in hot and humid conditions | 9 heat-adapted recreational male runners Age 25.4±6.9 years Weight (kg) 57.6±8.4 Non-users of caffeine (23.7±12.6 mg/day) Randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over design (at least 7 days gap between trials to nullify effect of caffeine) Caffeine (5 mg/kg) or placebo ingested as a capsule one hour before a running trial to exhaustion (70% VO2 max on a motorised treadmill in a heat-controlled laboratory (31 °C, 70% humidity) Diet monitored for 3 days before first trial and repeated for 3 days before 2nd trial (to minimise variation in pre-exercise muscle glycogen) Subjects asked to refrain from heavy exercise for 24 h before trials Subjects drank 3 ml of cool water per kg of body weight every 20 min during running trial to stay hydrated Heart rate (HR), core body temperature and rating of perceived exertion (RPE) were recorded at intervals of 10 mins, while oxygen consumption was measured at intervals of 20 min | Mean exhaustion time was 31.6% higher in the caffeine group: • Placebo 83.6±21.4 • Caffeine 110.1±29.3 Running time to exhaustion was significantly higher (p | Ingestion of caffeine improved the endurance running performance, but did not affect heart rate, core body temperature, oxygen uptake or RPE. | The lower RPE during the caffeine trial may be because of the positive effect of caffeine ingestion on nerve impulse transmission, as well as an analgesic effect and psychological effect. Perhaps this is the same reason subjects could sustain the treadmill running for longer in the caffeine trial. |

Source: Ping, WC, Keong, CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41. Used under a CC-BY-NC-SA licence.

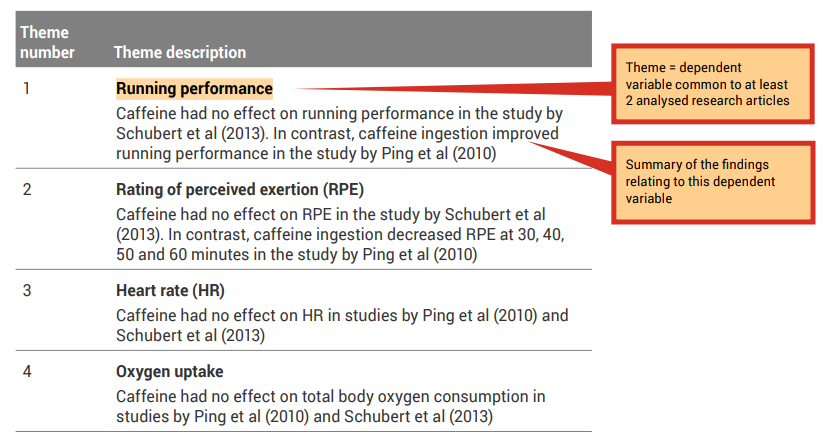

Step two of writing a literature review is synthesis.

Synthesis describes combining separate components or elements to form a connected whole.

You will use the results of your analysis to find themes to build your literature review around. Each of the themes identified will become a subheading within the body of your literature review.

A good place to start when identifying themes is with the dependent variables (results/findings) that were investigated in the research studies.

Because all of the research articles you are incorporating into your literature review are related to your topic, it is likely that they have similar study designs and have measured similar dependent variables. Review the ‘Results’ column of your analysis grid. You may like to collate the common themes in a synthesis grid (see, for example Table 7.4 ).

Step three of writing a literature review is evaluation, which can only be done after carefully analysing your research papers and synthesising the common themes (findings).

During the evaluation stage, you are making judgements on the themes presented in the research articles that you have read. This includes providing physiological explanations for the findings. It may be useful to refer to the discussion section of published original investigation research papers, or another literature review, where the authors may mention tested or hypothetical physiological mechanisms that may explain their findings.

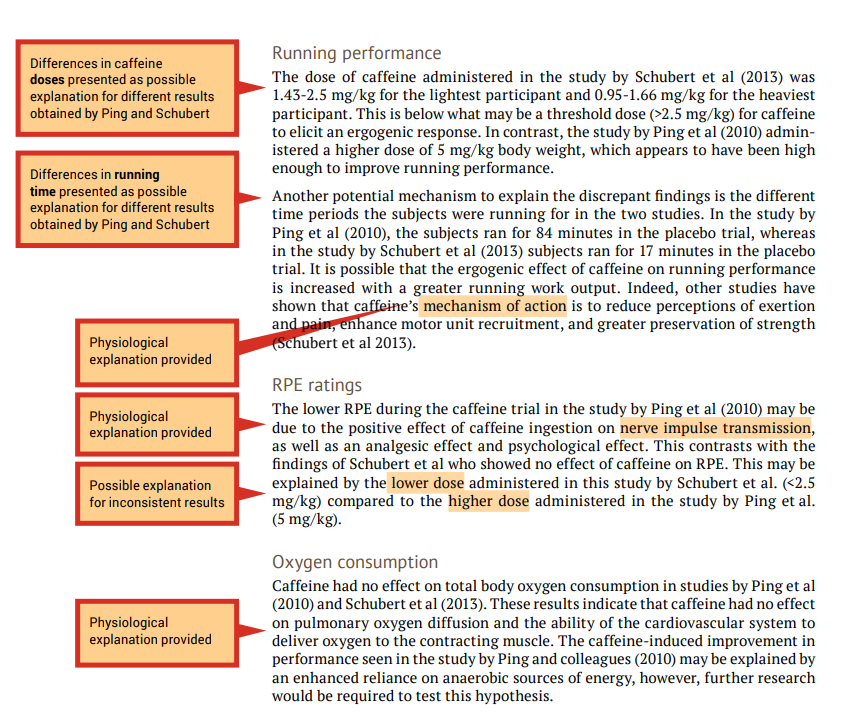

When the findings of the investigations related to a particular theme are inconsistent (e.g., one study shows that caffeine effects performance and another study shows that caffeine had no effect on performance) you should attempt to provide explanations of why the results differ, including physiological explanations. A good place to start is by comparing the methodologies to determine if there are any differences that may explain the differences in the findings (see the ‘Experimental design’ column of your analysis grid). An example of evaluation is shown in the examples that follow in this section, under ‘Running performance’ and ‘RPE ratings’.

When the findings of the papers related to a particular theme are consistent (e.g., caffeine had no effect on oxygen uptake in both studies) an evaluation should include an explanation of why the results are similar. Once again, include physiological explanations. It is still a good idea to compare methodologies as a background to the evaluation. An example of evaluation is shown in the following under ‘Oxygen consumption’.

7.3 Writing your literature review

Once you have completed the analysis, and synthesis grids and written your evaluation of the research papers , you can combine synthesis and evaluation information to create a paragraph for a literature review ( Figure 7.4 ).

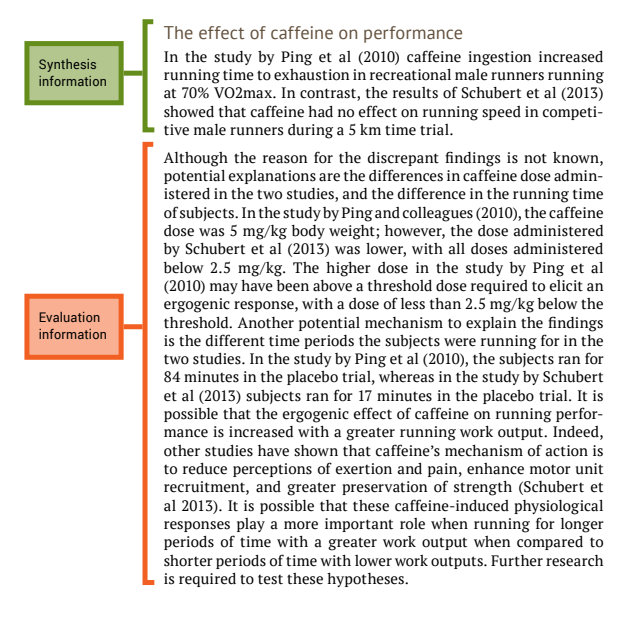

The following paragraphs are an example of combining the outcome of the synthesis and evaluation stages to produce a paragraph for a literature review.

Note that this is an example using only two papers – most literature reviews would be presenting information on many more papers than this ( (e.g., 106 papers in the review article by Bain and colleagues discussed later in this chapter). However, the same principle applies regardless of the number of papers reviewed.

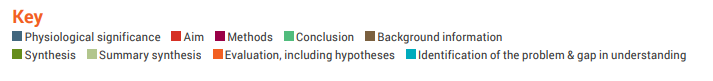

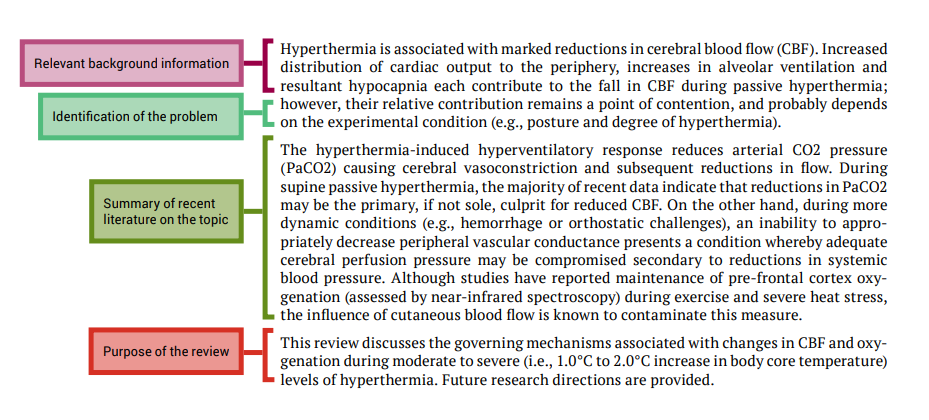

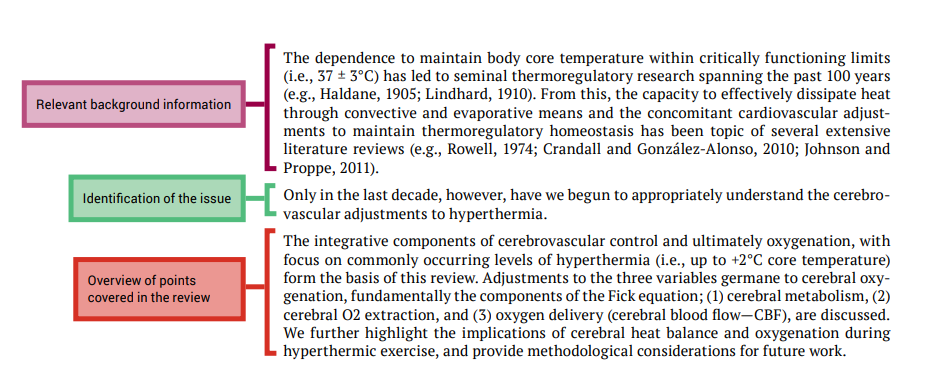

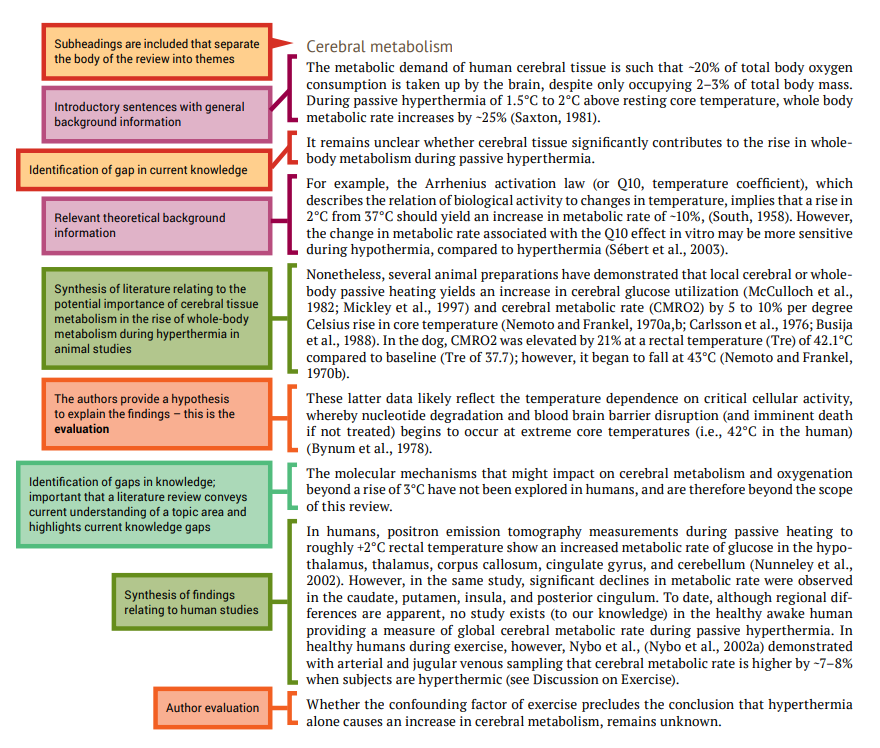

The next part of this chapter looks at the each section of a literature review and explains how to write them by referring to a review article that was published in Frontiers in Physiology and shown in Figure 7.1. Each section from the published article is annotated to highlight important features of the format of the review article, and identifies the synthesis and evaluation information.

In the examination of each review article section we will point out examples of how the authors have presented certain information and where they display application of important cognitive processes; we will use the colour code shown below:

This should be one paragraph that accurately reflects the contents of the review article.

Introduction

The introduction should establish the context and importance of the review

Body of literature review

The reference section provides a list of the references that you cited in the body of your review article. The format will depend on the journal of publication as each journal has their own specific referencing format.

It is important to accurately cite references in research papers to acknowledge your sources and ensure credit is appropriately given to authors of work you have referred to. An accurate and comprehensive reference list also shows your readers that you are well-read in your topic area and are aware of the key papers that provide the context to your research.

It is important to keep track of your resources and to reference them consistently in the format required by the publication in which your work will appear. Most scientists will use reference management software to store details of all of the journal articles (and other sources) they use while writing their review article. This software also automates the process of adding in-text references and creating a reference list. In the review article by Bain et al. (2014) used as an example in this chapter, the reference list contains 106 items, so you can imagine how much help referencing software would be. Chapter 5 shows you how to use EndNote, one example of reference management software.

Click the drop down below to review the terms learned from this chapter.

Copyright note:

- The quotation from Pautasso, M 2013, ‘Ten simple rules for writing a literature review’, PLoS Computational Biology is use under a CC-BY licence.

- Content from the annotated article and tables are based on Schubert, MM, Astorino, TA & Azevedo, JJL 2013, ‘The effects of caffeinated ‘energy shots’ on time trial performance’, Nutrients, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 2062–2075 (used under a CC-BY 3.0 licence ) and P ing, WC, Keong , CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41 (used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence ).

Bain, A.R., Morrison, S.A., & Ainslie, P.N. (2014). Cerebral oxygenation and hyperthermia. Frontiers in Physiology, 5 , 92.

Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten simple rules for writing a literature review. PLoS Computational Biology, 9 (7), e1003149.

How To Do Science Copyright © 2022 by University of Southern Queensland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Organizing and Creating Information

- Citation and Attribution

What Is a Literature Review?

Review the literature, write the literature review, further reading, learning objectives, attribution.

This guide is designed to:

- Identify the sections and purpose of a literature review in academic writing

- Review practical strategies and organizational methods for preparing a literature review

A literature review is a summary and synthesis of scholarly research on a specific topic. It should answer questions such as:

- What research has been done on the topic?

- Who are the key researchers and experts in the field?

- What are the common theories and methodologies?

- Are there challenges, controversies, and contradictions?

- Are there gaps in the research that your approach addresses?

The process of reviewing existing research allows you to fine-tune your research question and contextualize your own work. Preparing a literature review is a cyclical process. You may find that the research question you begin with evolves as you learn more about the topic.

Once you have defined your research question , focus on learning what other scholars have written on the topic.

In order to do a thorough search of the literature on the topic, define the basic criteria:

- Databases and journals: Look at the subject guide related to your topic for recommended databases. Review the tutorial on finding articles for tips.

- Books: Search BruKnow, the Library's catalog. Steps to searching ebooks are covered in the Finding Ebooks tutorial .

- What time period should it cover? Is currency important?

- Do I know of primary and secondary sources that I can use as a way to find other information?

- What should I be aware of when looking at popular, trade, and scholarly resources ?

One strategy is to review bibliographies for sources that relate to your interest. For more on this technique, look at the tutorial on finding articles when you have a citation .

Tip: Use a Synthesis Matrix

As you read sources, themes will emerge that will help you to organize the review. You can use a simple Synthesis Matrix to track your notes as you read. From this work, a concept map emerges that provides an overview of the literature and ways in which it connects. Working with Zotero to capture the citations, you build the structure for writing your literature review.

| Citation | Concept/Theme | Main Idea | Notes 1 | Notes 2 | Gaps in the Research | Quotation | Page |

How do I know when I am done?

A key indicator for knowing when you are done is running into the same articles and materials. With no new information being uncovered, you are likely exhausting your current search and should modify search terms or search different catalogs or databases. It is also possible that you have reached a point when you can start writing the literature review.

Tip: Manage Your Citations

These citation management tools also create citations, footnotes, and bibliographies with just a few clicks:

Zotero Tutorial

Endnote Tutorial

Your literature review should be focused on the topic defined in your research question. It should be written in a logical, structured way and maintain an objective perspective and use a formal voice.

Review the Summary Table you created for themes and connecting ideas. Use the following guidelines to prepare an outline of the main points you want to make.

- Synthesize previous research on the topic.

- Aim to include both summary and synthesis.

- Include literature that supports your research question as well as that which offers a different perspective.

- Avoid relying on one author or publication too heavily.

- Select an organizational structure, such as chronological, methodological, and thematic.

The three elements of a literature review are introduction, body, and conclusion.

Introduction

- Define the topic of the literature review, including any terminology.

- Introduce the central theme and organization of the literature review.

- Summarize the state of research on the topic.

- Frame the literature review with your research question.

- Focus on ways to have the body of literature tell its own story. Do not add your own interpretations at this point.

- Look for patterns and find ways to tie the pieces together.

- Summarize instead of quote.

- Weave the points together rather than list summaries of each source.

- Include the most important sources, not everything you have read.

- Summarize the review of the literature.

- Identify areas of further research on the topic.

- Connect the review with your research.

- DeCarlo, M. (2018). 4.1 What is a literature review? In Scientific Inquiry in Social Work. Open Social Work Education. https://scientificinquiryinsocialwork.pressbooks.com/chapter/4-1-what-is-a-literature-review/

- Literature Reviews (n.d.) https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/literature-reviews/ Accessed Nov. 10, 2021

This guide was designed to:

- Identify the sections and purpose of a literature review in academic writing

- Review practical strategies and organizational methods for preparing a literature review

Content on this page adapted from:

Frederiksen, L. and Phelps, S. (2017). Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students. Licensed CC BY 4.0

- << Previous: EndNote

- Last Updated: Jul 17, 2024 3:55 PM

- URL: https://libguides.brown.edu/organize

Brown University Library | Providence, RI 02912 | (401) 863-2165 | Contact | Comments | Library Feedback | Site Map

Library Intranet

Nursing and Allied Health: Building a Summary Table or Synthesis Matrix

- Nursing Library Services

- Library Support for Nursing Accreditation

- Academic Research Libraries (ACRL) Information Literacy Standards for Science

- ACRL Guidelines for Distance Learning

- AACN Resources: Information Literacy

- The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education

- Accreditation Commision for Education

- ACEN Learning Resources | Definitions & Standards

- Tutoring & Paper Review: College of Nursing & Allied Health Students

- Technology and Collaboration

- Affordable Learning Louisiana

- NIH Virtual Reality Funding

- How to Create Links to Library Resources

- Nursing Resources

- Literature Searching: Overview

- Nursing Resources: Books, Journals and Articles

- Assistive Technology Resources

- Web Accessibility Initiative WC3

- Healthcare Links for Persons With Disabilities

- Accessibility

- Accessibility Tools: Videos

- Braile Institute: Blind and Low Vision Web Accessibility

- Braile Institute: Assistive Technology for the Visually Impaired This link opens in a new window

- Mental Health Resources for Students & Faculty

- Student Activities & Organizations

- Anatomage FAQ's

- APA Reference Worksheet With Examples This link opens in a new window

- APA Style and Grammar Guidelines, 7.0

- What's New in APA Guide, 7.0 This link opens in a new window

- APA Instructional Aids for Professors/Instructors

- APA Handouts & Guides This link opens in a new window

- Sample Papers for Students and Instructors

- Academic Writer Tutorial: Basics This link opens in a new window

- APA Styling Your Paper

- When to cite or not cite a database

- Video: A Step-By-Step Guide for APA Style Student Papers

- Video: Citing Works in Text Using APA 7.0 This link opens in a new window

- Video: Creating References Using APA Guide, 7.0 This link opens in a new window

- Journal Article Reporting Standards

- Digital Information Literacy

- Tips Sheet: Copyright Essentials for Higher Education This link opens in a new window

- Citing National Patient Safety Goals (Joint Commission)

- Citing Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in APA format

- Best Nursing Apps

- Writing an Abstract for Your PILT or Special Project

- PILT Poster Presentation Archive

- Academic Success

- Healthcare Career Salaries

- Industry Statistics: Healthcare

- Nursing Organizations

- Radiology Organizations

- Controlled Medical Vocabularies

- COVID-19 Current Vaccines (Medscape)

- COVID-19 Current and Candidate Vaccine Landscape and Tracker (WHO)

- COVID-19: Clinician Care Guidance (CDC.gov) This link opens in a new window

- COVID -19 Contract Tracing & Patient Privacy (Cornell) This link opens in a new window

- COVID-19: Coronavirus Dashboard (Johns Hopkins Epidemiology)

- COVID-19: Coronavirus Guidelines (Up-To-Date) This link opens in a new window

- COVID-19: Critical Care Evidence (Cochrane) This link opens in a new window

- COVID-19: Diagnosis & Treatment (JAMA) This link opens in a new window

- COVID-19: Free Video Access (Jove) This link opens in a new window

- COVID-19: Healthcare Hub (Elsevier) This link opens in a new window

- COVID-19: Keeping Up With A Moving Target (Johns Hopkins Nursing Videos)

- COVID-19: LitCovid Daily Update (NLM)

- COVID 19 - Long Term Health Effects Stemming From COVID-19

- COVID-19: Louisiana Department of Health

- COVID-19: Novel Coronavirus Information Center (Elsevier) This link opens in a new window

- COVID-19 Nursing Resources (Medscape)

- COVID-19: Red Book - Recent Pediatric Updates (AAP)

- COVID-19: Washing Your Hands Thoroughly (NHS)

- COVID-19: Well-Being Initiative (ANF)

- Properly Putting On Your Facemask & Getting a Good Seal (Dr. Scheiner) This link opens in a new window

- Creating Personal Accounts

- Creating a CINAHL MyFolder Account

- Creating a PubMed | MyNCBI Personal Account

- Creating a ProQuest Nursing & Allied Health Premium | MyResearch Folder

- Creating an OVID MyWorkspace Personal Account

- Mobile APPS | CINAHL for Apple and Android Mobile Devices

- My Circulation Login

- Interlibrary Loan Personal Account

- Data Visualization Products

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD)

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders | DSM-5-TR

- [C1] Infections | Infectious Diseases

- [C04] Neoplasms

- [C05] Musculoskeletal Diseases

- [C06] Digestive System Diseases

- [C07] Stomatognathic Diseases

- [C08] Respiratory Tract Diseases

- [C09] Otorhinolaryngologic Diseases

- [C10] Nervous System Diseases

- [C11] Eye Diseases

- [C12] Urogenital Diseases

- [C14] Cardiovascular Diseases

- [C15] Hemic and Lymphatic Diseases

- [C16] Congenital, Hereditary, and Neonatal Diseases and Abnormalities

- [C17] Skin and Connective Tissue Diseases

- [C18] Nutritional and Metabolic Diseases

- [C19] Endocrine System Diseases

- [C20] Immune System Diseases

- [C21] Disorders of Environmental Origin

- [C22] Animal Diseases [Zoonotic diseases]

- [C23] Pathological Conditions, Signs and Symptoms

- [C24] Occupational Diseases

- [C25] Chemically-Induced Disorders

- [C26] Wounds and Injuries

- WHO Drug Information [Relative to Diseases]

- NDDK Patient Education Tool Kit

- Clinical Tools & Patient Education

- NDDK Resources on Medline Plus

- NDDK Open Research

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans

- Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans

- Move Your Way Community Resources

- National Youth Sports Strategy

- President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition

- White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health

- Equitable Long-Term Recovery and Resilience

- National Health Observances

- Finding Clinical Trials

- NIH News in Health

- Dosage Calculations & Pharmacology

- PICO - EBM Video This link opens in a new window

- PICO Slides

- Fillable CONSAH Pico Form

- Evidence Based Practice for Nursing

- Evidence-Based Nursing: -Step 2

- Evidence Appraisal - Step 3

- Evidence Application - Step 4

- Outcome Evaluation - Step 5

- Evidence Translation - Step 6

- Google Advanced Search for EBM

- Nursing Research Methods

- Faculty Book Request

- Proctor Request Form

- Peer Reviewed Literature: Assessment Goals

- Full Text Finder

- EBSCO e-Books Nursing 2021

- EBSCO eBooks Anesthesia

- EBSCO eBooks Radiology Science & Allied Health

- EBSCO eBooks: Writing About Nursing and Allied Health

- Alzheimers and Dementia

- Statistics on Aging

- CDC Bibliography: Alzheimers & Aging This link opens in a new window

- Health Conditions

- Health Behaviors

- Populations

- Settings and Systems

- Social Determinants of Health

- ILL Interlibrary Loan

- Gestational Diabetes and Fast Foods (MeSH)

- Mobile Resources

- Nursing Theory

- Psychiatric Nursing Journals

- Display, sort and; navigate

- Similar articles

- Cite, save and share

- Citations in PubMed

- All About PubMed Filters

- PubMed Quick Tours and Tutorials

- Evidence Based Practice Tutorial (PubMed) This link opens in a new window

- Developing a Clinical Question This link opens in a new window

- Using PubMed to Find Relevant Articles This link opens in a new window

- Next Steps This link opens in a new window

- Scenario (practice) This link opens in a new window

- Radiology Books and e-Books

- History of Radiology & Radiography

- Radiology: Anatomage This link opens in a new window

- Radiology Anatomy Atlas Viewer

- Advanced Radiographic Research

- Diagnostic Imaging Selected Articles

- Faculty and Administrative Resources

- Radiology Tech and MRI Salaries (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Radiology Technician Demand by State

- Review Tools for Graduate Students

- Training & Videos

- Register for an Online Meeting

- Joining an Online Meeting

- Training Videos & Search Examples

- Training Survey

- Sources for Health Statistics

- Ebola and Infectious Diseases

- Nursing Sites

- Writing Research Papers

Building a Summary Table or Synthesis Matrix

Quick Links | Nursing & Allied Health

- NSU Libraries Home

- Contact Your Librarian (Research Assistance)

- Nursing & Allied Health Databases

- Holidays & University Closures

- Review My Paper**

- Student Help Desk : Phone: (318) 357-6696 [email protected]

- Nursing & Alled Health Databases

- Shreveport Library Main Phone: 318.677.3007

- Shreveport Librarian Phone: 318.677.301 3

- Simplifying Synthesis | Download the Article PDF Copy

- Writing a Literature Review and Using a Synthesis Matrix

What a Summary Table or Synthesis Matrix looks like

Use the "Literature Review Matrix Template" as a guideline to help you sort through your thoughts, note important points and think through the similarities and differences:

You are organizing the review by ideas and not by sources . The literature review is not just a summary of the already published works. Your synthesis should show how various articles are linked.

A summary table is also called a synthesis matrix. The table helps you organize and compare information for your systematic review, scholarly report, dissertation or thesis

Synthesis Matrix.

A summary table is also called a synthesis matrix . A summary table helps you record the main points of each source and document how sources relate to each other. After summarizing and evaluating your sources, arrange them in a matrix to help you see how they relate to each other, and apply to each of your themes or variables.

Faculty who typically guide students find it challenging to help students learn how to synthesize material (Blondy, Blakesless, Scheffer, Rubenfeld, Cronin, & Luster-Turner, 2016; Kearney, 2015) . Writers can easily summarize material but seem to struggle to adequately synthesize knowledge about their topic and express that in their writing. So, whether you are writing a student papers, dissertations, or scholarly report it is necessary to learn a few tips and tricks to organize your ideas.

Building a summary table and developing solid synthesis skills is important for nurses, nurse practitioners, and allied health researchers. Quality evidence-based practice initiatives and nursing care and medicine are based on understanding and evaluating the resources and research available, identifying gaps, and building a strong foundation for future work.

Good synthesis is about putting the data gathered, references read, and literature analyzed together in a new way that shows connections and relationships. ( Shellenbarger, 2016 ). The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines synthesis as something that is made by combining different things or the composition or combination of parts or elements so as to form a whole (Synthesis, n.d.).

In other words, building a summary table or synthesis matrix involves taking information from a variety of sources, evaluating that information and forming new ideas or insights in an original way. This can be a new and potentially challenging experience for students and researchers who are used to just repeating what is already in the literature.

Visit Our Libraries

Interlibrary Loan | Shreveport Education Center Library | Eugene P. Watson Memorial Library | NSU Leesville Library

Cammie G. Henry Research Center | Prince Music Media Library

- << Previous: Best Nursing Apps

- Next: Writing an Abstract for Your PILT or Special Project >>

- Last Updated: Sep 5, 2024 2:05 PM

- URL: https://libguides.nsula.edu/NursingandAlliedHealth

Literature Review Basics

- What is a Literature Review?

- Synthesizing Research

- Using Research & Synthesis Tables

- Additional Resources

About the Research and Synthesis Tables

Research Tables and Synthesis Tables are useful tools for organizing and analyzing your research as you assemble your literature review. They represent two different parts of the review process: assembling relevant information and synthesizing it. Use a Research table to compile the main info you need about the items you find in your research -- it's a great thing to have on hand as you take notes on what you read! Then, once you've assembled your research, use the Synthesis table to start charting the similarities/differences and major themes among your collected items.

We've included an Excel file with templates for you to use below; the examples pictured on this page are snapshots from that file.

- Research and Synthesis Table Templates This Excel workbook includes simple templates for creating research tables and synthesis tables. Feel free to download and use!

Using the Research Table

This is an example of a research table, in which you provide a basic description of the most important features of the studies, articles, and other items you discover in your research. The table identifies each item according to its author/date of publication, its purpose or thesis, what type of work it is (systematic review, clinical trial, etc.), the level of evidence it represents (which tells you a lot about its impact on the field of study), and its major findings. Your job, when you assemble this information, is to develop a snapshot of what the research shows about the topic of your research question and assess its value (both for the purpose of your work and for general knowledge in the field).

Think of your work on the research table as the foundational step for your analysis of the literature, in which you assemble the information you'll be analyzing and lay the groundwork for thinking about what it means and how it can be used.

Using the Synthesis Table

This is an example of a synthesis table or synthesis matrix , in which you organize and analyze your research by listing each source and indicating whether a given finding or result occurred in a particular study or article ( each row lists an individual source, and each finding has its own column, in which X = yes, blank = no). You can also add or alter the columns to look for shared study populations, sort by level of evidence or source type, etc. The key here is to use the table to provide a simple representation of what the research has found (or not found, as the case may be). Think of a synthesis table as a tool for making comparisons, identifying trends, and locating gaps in the literature.

How do I know which findings to use, or how many to include? Your research question tells you which findings are of interest in your research, so work from your research question to decide what needs to go in each Finding header, and how many findings are necessary. The number is up to you; again, you can alter this table by adding or deleting columns to match what you're actually looking for in your analysis. You should also, of course, be guided by what's actually present in the material your research turns up!

- << Previous: Synthesizing Research

- Next: Additional Resources >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 12:06 PM

- URL: https://usi.libguides.com/literature-review-basics

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 7: Synthesizing Sources

Learning objectives.

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

- synthesize key sources connecting them with the research question and topic area.

7.1 Overview of synthesizing

7.1.1 putting the pieces together.

Combining separate elements into a whole is the dictionary definition of synthesis. It is a way to make connections among and between numerous and varied source materials. A literature review is not an annotated bibliography, organized by title, author, or date of publication. Rather, it is grouped by topic to create a whole view of the literature relevant to your research question.

Your synthesis must demonstrate a critical analysis of the papers you collected as well as your ability to integrate the results of your analysis into your own literature review. Each paper collected should be critically evaluated and weighed for “adequacy, appropriateness, and thoroughness” ( Garrard, 2017 ) before inclusion in your own review. Papers that do not meet this criteria likely should not be included in your literature review.

Begin the synthesis process by creating a grid, table, or an outline where you will summarize, using common themes you have identified and the sources you have found. The summary grid or outline will help you compare and contrast the themes so you can see the relationships among them as well as areas where you may need to do more searching. Whichever method you choose, this type of organization will help you to both understand the information you find and structure the writing of your review. Remember, although “the means of summarizing can vary, the key at this point is to make sure you understand what you’ve found and how it relates to your topic and research question” ( Bennard et al., 2014 ).

As you read through the material you gather, look for common themes as they may provide the structure for your literature review. And, remember, research is an iterative process: it is not unusual to go back and search information sources for more material.

At one extreme, if you are claiming, ‘There are no prior publications on this topic,’ it is more likely that you have not found them yet and may need to broaden your search. At another extreme, writing a complete literature review can be difficult with a well-trod topic. Do not cite it all; instead cite what is most relevant. If that still leaves too much to include, be sure to reference influential sources…as well as high-quality work that clearly connects to the points you make. ( Klingner, Scanlon, & Pressley, 2005 ).

7.2 Creating a summary table

Literature reviews can be organized sequentially or by topic, theme, method, results, theory, or argument. It’s important to develop categories that are meaningful and relevant to your research question. Take detailed notes on each article and use a consistent format for capturing all the information each article provides. These notes and the summary table can be done manually, using note cards. However, given the amount of information you will be recording, an electronic file created in a word processing or spreadsheet is more manageable. Examples of fields you may want to capture in your notes include:

- Authors’ names

- Article title

- Publication year

- Main purpose of the article

- Methodology or research design

- Participants

- Measurement

- Conclusions

Other fields that will be useful when you begin to synthesize the sum total of your research:

- Specific details of the article or research that are especially relevant to your study

- Key terms and definitions

- Strengths or weaknesses in research design

- Relationships to other studies

- Possible gaps in the research or literature (for example, many research articles conclude with the statement “more research is needed in this area”)

- Finally, note how closely each article relates to your topic. You may want to rank these as high, medium, or low relevance. For papers that you decide not to include, you may want to note your reasoning for exclusion, such as ‘small sample size’, ‘local case study,’ or ‘lacks evidence to support assertion.’

This short video demonstrates how a nursing researcher might create a summary table.

7.2.1 Creating a Summary Table

Summary tables can be organized by author or by theme, for example:

| Author/Year | Research Design | Participants or Population Studied | Comparison | Outcome |

| Smith/2010 | Mixed methods | Undergraduates | Graduates | Improved access |

| King/2016 | Survey | Females | Males | Increased representation |

| Miller/2011 | Content analysis | Nurses | Doctors | New procedure |

For a summary table template, see http://blogs.monm.edu/writingatmc/files/2013/04/Synthesis-Matrix-Template.pdf

7.3 Creating a summary outline

An alternate way to organize your articles for synthesis it to create an outline. After you have collected the articles you intend to use (and have put aside the ones you won’t be using), it’s time to identify the conclusions that can be drawn from the articles as a group.

Based on your review of the collected articles, group them by categories. You may wish to further organize them by topic and then chronologically or alphabetically by author. For each topic or subtopic you identified during your critical analysis of the paper, determine what those papers have in common. Likewise, determine which ones in the group differ. If there are contradictory findings, you may be able to identify methodological or theoretical differences that could account for the contradiction (for example, differences in population demographics). Determine what general conclusions you can report about the topic or subtopic as the entire group of studies relate to it. For example, you may have several studies that agree on outcome, such as ‘hands on learning is best for science in elementary school’ or that ‘continuing education is the best method for updating nursing certification.’ In that case, you may want to organize by methodology used in the studies rather than by outcome.

Organize your outline in a logical order and prepare to write the first draft of your literature review. That order might be from broad to more specific, or it may be sequential or chronological, going from foundational literature to more current. Remember, “an effective literature review need not denote the entire historical record, but rather establish the raison d’etre for the current study and in doing so cite that literature distinctly pertinent for theoretical, methodological, or empirical reasons.” ( Milardo, 2015, p. 22 ).

As you organize the summarized documents into a logical structure, you are also appraising and synthesizing complex information from multiple sources. Your literature review is the result of your research that synthesizes new and old information and creates new knowledge.

7.4 Additional resources:

Literature Reviews: Using a Matrix to Organize Research / Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota

Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources / Indiana University

Writing a Literature Review and Using a Synthesis Matrix / Florida International University

Sample Literature Reviews Grid / Complied by Lindsay Roberts

Select three or four articles on a single topic of interest to you. Then enter them into an outline or table in the categories you feel are important to a research question. Try both the grid and the outline if you can to see which suits you better. The attached grid contains the fields suggested in the video .

Literature Review Table

| Author Date | Topic/Focus Purpose | Conceptual Theoretical Framework | Paradigm Methods | Context Setting Sample | Findings | Gaps |

Test Yourself

- Select two articles from your own summary table or outline and write a paragraph explaining how and why the sources relate to each other and your review of the literature.

- In your literature review, under what topic or subtopic will you place the paragraph you just wrote?

Image attribution

Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students Copyright © by Linda Frederiksen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Literature Review Example

A literature review is a summary of the existing knowledge and research on a particular subject. by identifying gaps in the literature, it provides a foundation for future research. as such, it’s a crucial first step in any research project..

What is a literature review?

A literature review serves several purposes:

- identifies knowledge gaps

- evaluates the quality of existing research

- provides a foundation for newly presented research

Looking at existing examples of literature reviews is beneficial to get a clear understanding of what they entail. Find examples of a literature review by using an academic search engine (e.g. Google Scholar). As a starting point, search for your keyword or topic along with the term "literature review".

Example of literature review

Identify the research question or topic, making it as narrow as possible. In this example of a literature review, we review the anxiolytic (anti-anxiety) activity of Piper methysticum , or Kava .

Let's walk through the steps in the process with this literature review example.

Define the research question

First, identify the research question or topic, making it as narrow as possible. In this literature review example, we're examining the effects of urbanization on the migration of birds.

Search for relevant literature

Searching for relevant studies is arguably the most important aspect of the literature review.

Start by identifying keywords and phrases related to the topic and use them to search academic journals and databases ( Google Scholar , BASE , PubMed , etc.). For our example, you might start with "the effects of urbanization on bird migration", but after researching the field, discover that other terms like "avian migration" and "avian populations" are more commonly used.

Search for your keywords in Litmaps to find some initial articles to explore the field from. You can then use Litmaps to find additinal sources and curate a whole library of literature on your topic.

Search for your keywords in Litmaps, and select a starting article. This will return a visualization containing suggestions for relevant articles on your literature review topic. Review these to start curating your library.

Evaluate the sources

Evaluate the relevance and quality of the sources found by reading abstracts of the most relevant articles. Additionally, consider the publication venue, year of publication and other salient measures to identify the reliability and relevance of the source.

Read and analyze the sources

Take notes on the key findings, methodologies, and theoretical frameworks used in the studies.

Use a research-friendly note-taking software, like Obsidian , that provide #tags to keep track of key concepts.

Organize the literature

Organize the literature according to themes, subtopics, or categories, which will help outline the layout of the literature review.

Tag keywords using a tool like Obsidian to help organize papers into subtopics for the review.

Write the literature review

Summarize and synthesize the findings from the sources analyzed. Start with an introduction that defines the research question, followed by the themes, subtopics, or categories identified. After that, provide a discussion or conclusion that addresses any gaps in the literature to motivate future research. Lastly, edit and revise your review to ensure it is well-structured, clear, and concise. The example below is from a review paper, which includes a table comparing the different sources evaluated. Such tables can be useful if you are conducting a comprehensive review.

If you're conducting a comprehensive review, you can include a table of sources reviewed in your process, like the one above from this publication .

Cite and reference the sources

Lastly, cite and reference the sources used in the literature review. Consider any referencing style requirements of the institution or journal you're submitting to. APA is the most common. However, you may need to familiarize yourself with other citation styles such as MLA, Chicago, or MHRA depending on your venue. See the image below for a literature review example APA of references. To cite references you've saved in Litmaps, you can move your saved articles from Litmaps to a reference manager (i.e. Zotero, Mendeley, EndNote, etc.) and then export their bibliography from there. Here's how to export articles from Litmaps.

Use a reference manager tool like Zotero to easily export which makes them easy to manage, like in this APA literature review example.

A successful literature review tells a brief story about the topic at hand and leaves the reader a clear notion of what has been covered. Most importantly, a literature review addresses any gaps in the field and frames newly presented research. Understand the key steps and look at literature review examples in order to create a high quality review.

Header image Forest & Kim Starr, used under Creative Commons BY 3.0

Jump to navigation

Cochrane Training

Chapter 14: completing ‘summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence.

Holger J Schünemann, Julian PT Higgins, Gunn E Vist, Paul Glasziou, Elie A Akl, Nicole Skoetz, Gordon H Guyatt; on behalf of the Cochrane GRADEing Methods Group (formerly Applicability and Recommendations Methods Group) and the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group

Key Points:

- A ‘Summary of findings’ table for a given comparison of interventions provides key information concerning the magnitudes of relative and absolute effects of the interventions examined, the amount of available evidence and the certainty (or quality) of available evidence.

- ‘Summary of findings’ tables include a row for each important outcome (up to a maximum of seven). Accepted formats of ‘Summary of findings’ tables and interactive ‘Summary of findings’ tables can be produced using GRADE’s software GRADEpro GDT.

- Cochrane has adopted the GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) for assessing certainty (or quality) of a body of evidence.

- The GRADE approach specifies four levels of the certainty for a body of evidence for a given outcome: high, moderate, low and very low.

- GRADE assessments of certainty are determined through consideration of five domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias. For evidence from non-randomized studies and rarely randomized studies, assessments can then be upgraded through consideration of three further domains.

Cite this chapter as: Schünemann HJ, Higgins JPT, Vist GE, Glasziou P, Akl EA, Skoetz N, Guyatt GH. Chapter 14: Completing ‘Summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence [last updated August 2023]. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5. Cochrane, 2024. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

14.1 ‘Summary of findings’ tables

14.1.1 introduction to ‘summary of findings’ tables.

‘Summary of findings’ tables present the main findings of a review in a transparent, structured and simple tabular format. In particular, they provide key information concerning the certainty or quality of evidence (i.e. the confidence or certainty in the range of an effect estimate or an association), the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the main outcomes. Cochrane Reviews should incorporate ‘Summary of findings’ tables during planning and publication, and should have at least one key ‘Summary of findings’ table representing the most important comparisons. Some reviews may include more than one ‘Summary of findings’ table, for example if the review addresses more than one major comparison, or includes substantially different populations that require separate tables (e.g. because the effects differ or it is important to show results separately). In the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), all ‘Summary of findings’ tables for a review appear at the beginning, before the Background section.

14.1.2 Selecting outcomes for ‘Summary of findings’ tables

Planning for the ‘Summary of findings’ table starts early in the systematic review, with the selection of the outcomes to be included in: (i) the review; and (ii) the ‘Summary of findings’ table. This is a crucial step, and one that review authors need to address carefully.

To ensure production of optimally useful information, Cochrane Reviews begin by developing a review question and by listing all main outcomes that are important to patients and other decision makers (see Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 ). The GRADE approach to assessing the certainty of the evidence (see Section 14.2 ) defines and operationalizes a rating process that helps separate outcomes into those that are critical, important or not important for decision making. Consultation and feedback on the review protocol, including from consumers and other decision makers, can enhance this process.

Critical outcomes are likely to include clearly important endpoints; typical examples include mortality and major morbidity (such as strokes and myocardial infarction). However, they may also represent frequent minor and rare major side effects, symptoms, quality of life, burdens associated with treatment, and resource issues (costs). Burdens represent the impact of healthcare workload on patient function and well-being, and include the demands of adhering to an intervention that patients or caregivers (e.g. family) may dislike, such as having to undergo more frequent tests, or the restrictions on lifestyle that certain interventions require (Spencer-Bonilla et al 2017).

Frequently, when formulating questions that include all patient-important outcomes for decision making, review authors will confront reports of studies that have not included all these outcomes. This is particularly true for adverse outcomes. For instance, randomized trials might contribute evidence on intended effects, and on frequent, relatively minor side effects, but not report on rare adverse outcomes such as suicide attempts. Chapter 19 discusses strategies for addressing adverse effects. To obtain data for all important outcomes it may be necessary to examine the results of non-randomized studies (see Chapter 24 ). Cochrane, in collaboration with others, has developed guidance for review authors to support their decision about when to look for and include non-randomized studies (Schünemann et al 2013).

If a review includes only randomized trials, these trials may not address all important outcomes and it may therefore not be possible to address these outcomes within the constraints of the review. Review authors should acknowledge these limitations and make them transparent to readers. Review authors are encouraged to include non-randomized studies to examine rare or long-term adverse effects that may not adequately be studied in randomized trials. This raises the possibility that harm outcomes may come from studies in which participants differ from those in studies used in the analysis of benefit. Review authors will then need to consider how much such differences are likely to impact on the findings, and this will influence the certainty of evidence because of concerns about indirectness related to the population (see Section 14.2.2 ).

Non-randomized studies can provide important information not only when randomized trials do not report on an outcome or randomized trials suffer from indirectness, but also when the evidence from randomized trials is rated as very low and non-randomized studies provide evidence of higher certainty. Further discussion of these issues appears also in Chapter 24 .

14.1.3 General template for ‘Summary of findings’ tables

Several alternative standard versions of ‘Summary of findings’ tables have been developed to ensure consistency and ease of use across reviews, inclusion of the most important information needed by decision makers, and optimal presentation (see examples at Figures 14.1.a and 14.1.b ). These formats are supported by research that focused on improved understanding of the information they intend to convey (Carrasco-Labra et al 2016, Langendam et al 2016, Santesso et al 2016). They are available through GRADE’s official software package developed to support the GRADE approach: GRADEpro GDT (www.gradepro.org).

Standard Cochrane ‘Summary of findings’ tables include the following elements using one of the accepted formats. Further guidance on each of these is provided in Section 14.1.6 .

- A brief description of the population and setting addressed by the available evidence (which may be slightly different to or narrower than those defined by the review question).

- A brief description of the comparison addressed in the ‘Summary of findings’ table, including both the experimental and comparison interventions.

- A list of the most critical and/or important health outcomes, both desirable and undesirable, limited to seven or fewer outcomes.

- A measure of the typical burden of each outcomes (e.g. illustrative risk, or illustrative mean, on comparator intervention).

- The absolute and relative magnitude of effect measured for each (if both are appropriate).

- The numbers of participants and studies contributing to the analysis of each outcomes.

- A GRADE assessment of the overall certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome (which may vary by outcome).