How to Write Dialogue: 7 Great Tips for Writers (With Examples)

By Hannah Yang

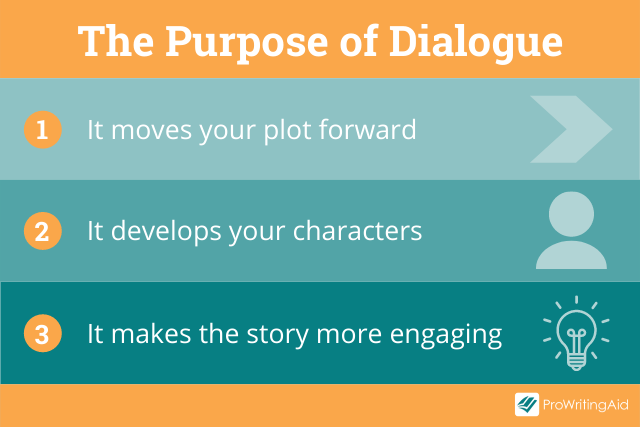

Great dialogue serves multiple purposes. It moves your plot forward. It develops your characters and it makes the story more engaging.

It’s not easy to do all these things at once, but when you master the art of writing dialogue, readers won’t be able to put your book down.

In this article, we will teach you the rules for writing dialogue and share our top dialogue tips that will make your story sing.

Dialogue Rules

How to format dialogue, 7 tips for writing dialogue in a story or book, dialogue examples.

Before we look at tips for writing powerful dialogue , let’s start with an overview of basic dialogue rules.

- Start a new paragraph each time there’s a new speaker. Whenever a new character begins to speak, you should give them their own paragraph. This rule makes it easier for the reader to follow the conversation.

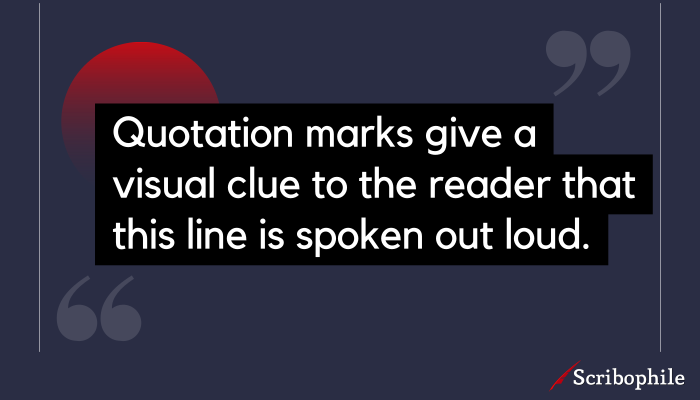

- Keep all speech between quotation marks . Everything that a character says should go between quotation marks, including the final punctuation marks. For example, periods and commas should always come before the final quotation mark, not after.

- Don’t use end quotations for paragraphs within long speeches. If a single character speaks for such a long time that you break their speech up into multiple paragraphs, you should omit the quotation marks at the end of each paragraph until they stop talking. The final quotation mark indicates that their speech is over.

- Use single quotes when a character quotes someone else. Whenever you have a quote within a quote, you should use single quotation marks (e.g. She said, “He had me at ‘hello.’”)

- Dialogue tags are optional. A dialogue tag is anything that indicates which character is speaking and how, such as “she said,” “he whispered,” or “I shouted.” You can use dialogue tags if you want to give the reader more information about who’s speaking, but you can also choose to omit them if you want the dialogue to flow more naturally. We’ll be discussing more about this rule in our tips below.

Let’s walk through some examples of how to format dialogue .

The simplest formatting option is to write a line of speech without a dialogue tag. In this case, the entire line of speech goes within the quotation marks, including the period at the end.

- Example: “I think I need a nap.”

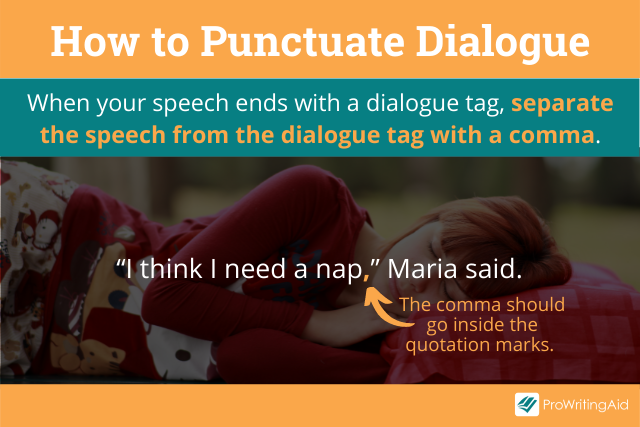

Another common formatting option is to write a single line of speech that ends with a dialogue tag.

Here, you should separate the speech from the dialogue tag with a comma, which should go inside the quotation marks.

- Example: “I think I need a nap,” Maria said.

You can also write a line of speech that starts with a dialogue tag. Again, you separate the dialogue tag with a comma, but this time, the comma goes outside the quotation marks.

- Example: Maria said, “I think I need a nap.”

As an alternative to a simple dialogue tag, you can write a line of speech accompanied by an action beat. In this case, you should use a period rather than a comma, because the action beat is a full sentence.

- Example: Maria sat down on the bed. “I think I need a nap.”

Finally, you can choose to include an action beat while the character is talking.

In this case, you would use em-dashes to separate the action from the dialogue, to indicate that the action happens without a pause in the speech.

- Example: “I think I need”—Maria sat down on the bed—“a nap.”

Now that we’ve covered the basics, we can move on to the more nuanced aspects of writing dialogue.

Here are our seven favorite tips for writing strong, powerful dialogue that will keep your readers engaged.

Tip #1: Create Character Voices

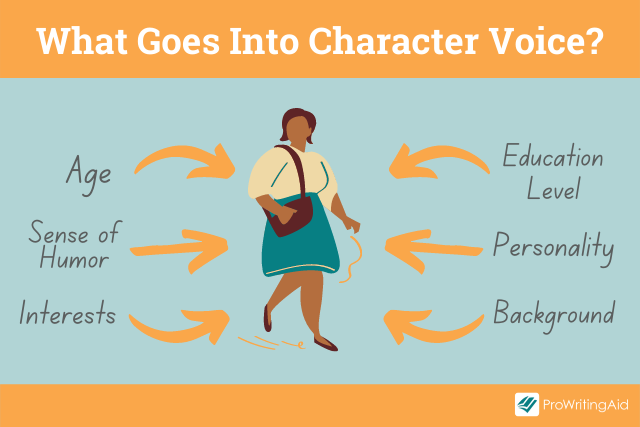

Dialogue is a great way to reveal your characters. What your characters say, and how they say it, can tell us so much about what kind of people they are.

Some characters are witty and gregarious. Others are timid and unobtrusive.

Speech patterns vary drastically from person to person.

To make someone stop talking to them, one character might say “I would rather not talk about this right now,” while another might say, “Shut your mouth before I shut it for you.”

When you’re writing dialogue, think about your character’s education level, personality, and interests.

- What kind of slang do they use?

- Do they prefer long or short sentences?

- Do they ask questions or make assertions?

Each character should have their own voice.

Ideally, you want to write dialogue that lets your reader identify the person speaking at any point in your story just by looking at what’s between the quotation marks.

Tip #2: Write Realistic Dialogue

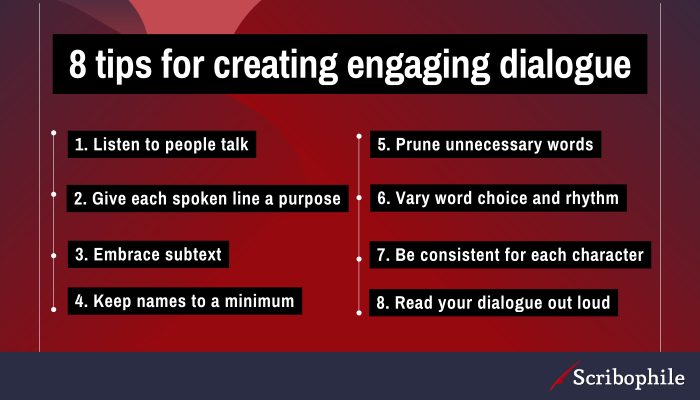

Good dialogue should sound natural. Listen to how people talk in real life and try to replicate it on the page when you write dialogue.

Don’t be afraid to break the rules of grammar, or to use an occasional exclamation point to punctuate dialogue.

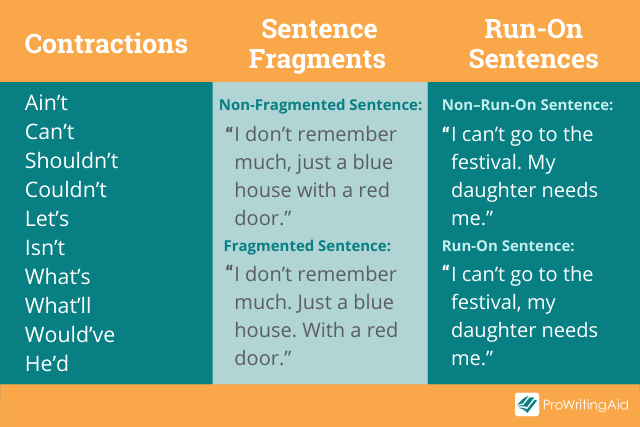

It’s okay to use contractions , sentence fragments , and run-on sentences , even if you wouldn’t use them in other parts of the story.

This doesn’t mean that realistic dialogue should sound exactly like the way people speak in the real world.

If you’ve ever read a court transcript, you know that real-life speech is riddled with “ums” and “ahs” and repeated words and phrases. A few paragraphs of this might put your readers to sleep.

Compelling dialogue should sound like a real conversation, while still being wittier, smoother, and better worded than real speech.

Tip #3: Simplify Your Dialogue Tags

A dialogue tag is anything that tells the reader which character is talking within that same paragraph, such as “she said” or “I asked.”

When you’re writing dialogue, remember that simple dialogue tags are the most effective .

Often, you can omit dialogue tags after the conversation has started flowing, especially if only two characters are participating.

The reader will be able to keep up with who’s speaking as long as you start a new paragraph each time the speaker changes.

When you do need to use a dialogue tag, a simple “he said” or “she said” will do the trick.

Our brains generally skip over the word “said” when we’re reading, while other dialogue tags are a distraction.

A common mistake beginner writers make is to avoid using the word “said.”

Characters in amateur novels tend to mutter, whisper, declare, or chuckle at every line of dialogue. This feels overblown and distracts from the actual story.

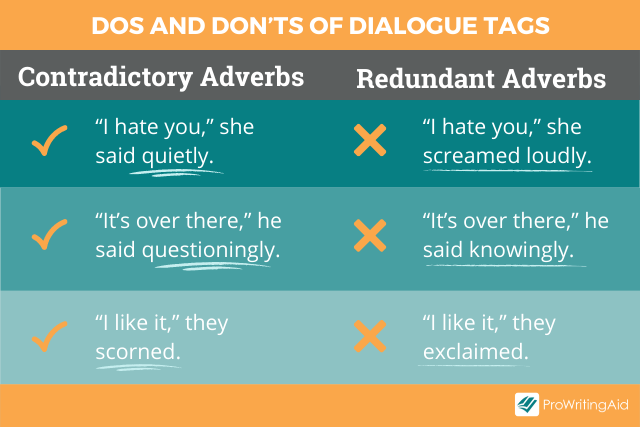

Another common mistake is to attach an adverb to the word “said.” Characters in amateur novels rarely just say things—they have to say things loudly, quietly, cheerfully, or angrily.

If you’re writing great dialogue, readers should be able to figure out whether your character is cheerful or angry from what’s within the quotation marks.

The only exception to this rule is if the dialogue tag contradicts the dialogue itself. For example, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said angrily.

The word “angrily” is redundant here because the words inside the quotation marks already imply that the character is speaking angrily.

In contrast, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said thoughtfully.

Here, the word “thoughtfully” is well-placed because it contrasts with what we might otherwise assume. It adds an additional nuance to the sentence inside the quotation marks.

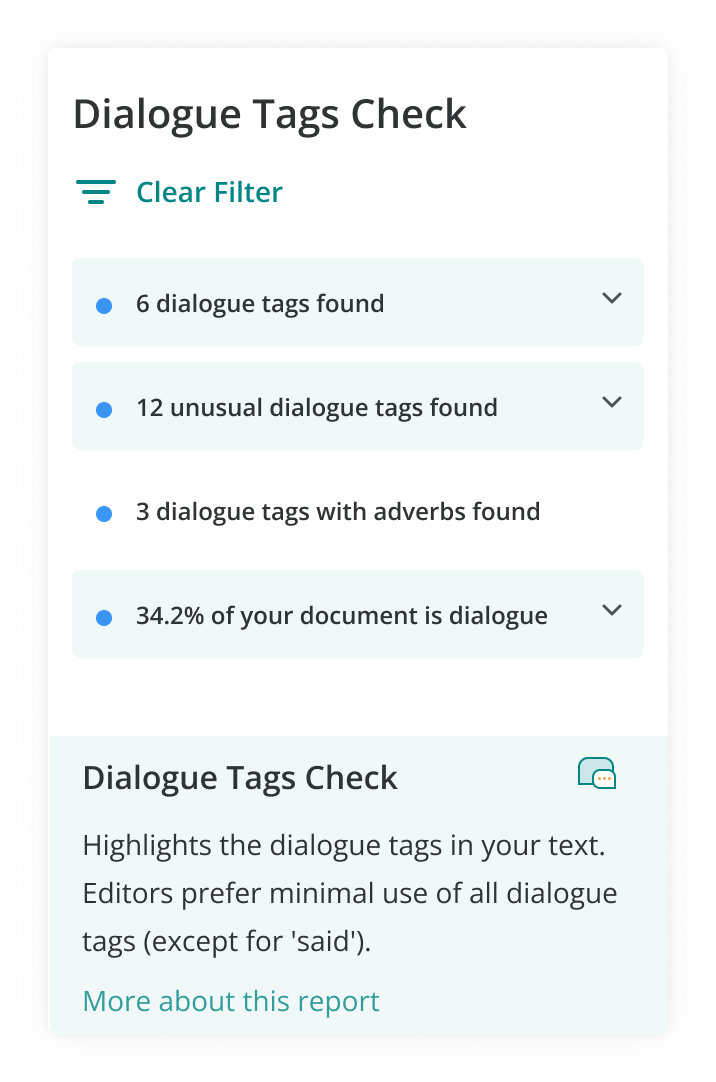

You can use the ProWritingAid dialogue check when you write dialogue to make sure your dialogue tags are pulling their weight and aren’t distracting readers from the main storyline.

Sign up for your free ProWritingAid account to check your dialogue tags today.

Tip #4: Balance Speech with Action

When you’re writing dialogue, you can use action beats —descriptions of body language or physical action—to show what each character is doing throughout the conversation.

Learning how to write action beats is an important component of learning how to write dialogue.

Good dialogue becomes even more interesting when the characters are doing something active at the same time.

You can watch people in real life, or even characters in movies, to see what kinds of body language they have. Some pick at their fingernails. Some pace the room. Some tap their feet on the floor.

Including physical action when writing dialogue can have multiple benefits:

- It changes the pace of your dialogue and makes the rhythm more interesting

- It prevents “white room syndrome,” which is when a scene feels like it’s happening in a white room because it’s all dialogue and no description

- It shows the reader who’s speaking without using speaker tags

You can decide how often to include physical descriptions in each scene. All dialogue has an ebb and flow to it, and you can use beats to control the pace of your dialogue scenes.

If you want a lot of tension in your scene, you can use fewer action beats to let the dialogue ping-pong back and forth.

If you want a slower scene, you can write dialogue that includes long, detailed action beats to help the reader relax.

You should start a separate sentence, or even a new paragraph, for each of these longer beats.

Tip #5: Write Conversations with Subtext

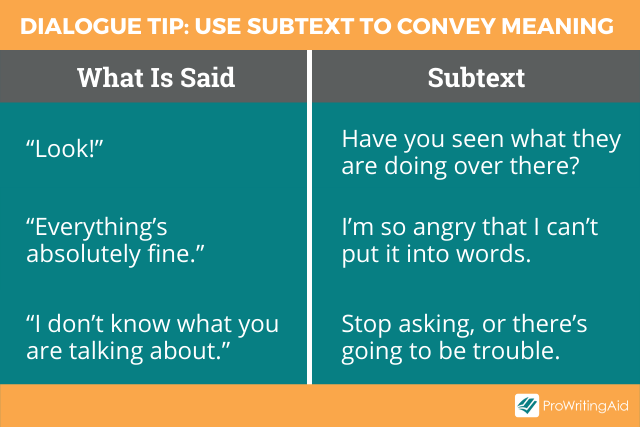

Every conversation has subtext , because we rarely say exactly what we mean. The best dialogue should include both what is said and what is not said.

I once had a roommate who cared a lot about the tidiness of our apartment, but would never say it outright. We soon figured out that whenever she said something like “I might bring some friends over tonight,” what she meant was “Please wash your dishes, because there are no clean plates left for my friends to use.”

When you’re writing dialogue, it’s important to think about what’s not being said. Even pleasant conversations can hide a lot beneath the surface.

Is one character secretly mad at the other?

Is one secretly in love with the other?

Is one thinking about tomorrow’s math test and only pretending to pay attention to what the other person is saying?

Personally, I find it really hard to use subtext when I write dialogue from scratch.

In my first drafts I let my characters say what they really mean. Then, when I’m editing, I go back and figure out how to convey the same information through subtext instead.

Tip #6: Show, Don’t Tell

When I was in high school, I once wrote a story in which the protagonist’s mother tells her: “As you know, Susan, your dad left us when you were five.”

I’ve learned a lot about the writing craft since high school, but it doesn’t take a brilliant writer to figure out that this is not something any mother would say to her daughter in real life.

The reason I wrote that line of dialogue was because I wanted to tell the reader when Susan last saw her father, but I didn’t do it in a realistic way.

Don’t shoehorn information into your characters’ conversations if they’re not likely to say it to each other.

One useful trick is to have your characters get into an argument.

You can convey a lot of information about a topic through their conflicting opinions, without making it sound like either of the characters is saying things for the reader’s benefit.

Here’s one way my high school self could have conveyed the same information in a more realistic way in just a few lines:

Susan: “Why didn’t you tell me Dad was leaving? Why didn’t you let me say goodbye?”

Mom: “You were only five. I wanted to protect you.”

Tip #7: Keep Your Dialogue Concise

Dialogue tends to flow out easily when you’re drafting your story, so in the editing process, you’ll need to be ruthless. Cut anything that doesn’t move the story forward.

Try not to write dialogue that feels like small talk.

You can eliminate most hellos and goodbyes, or summarize them instead of showing them. Readers don’t want to waste their time reading dialogue that they hear every day.

In addition, try not to write dialogue with too many trigger phrases, which are questions that trigger the next line of dialogue, such as:

- “And then what?”

- “What do you mean?”

It’s tempting to slip these in when you’re writing dialogue because they keep the conversation flowing. I still catch myself doing this from time to time.

Remember that you don’t need three lines of dialogue when one line could accomplish the same thing.

Let’s look at some dialogue examples from successful novels that follow each of our seven tips.

Dialogue Example #1: How to Create Character Voice

Let’s start with an example of a character with a distinct voice from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets by J.K. Rowling.

“What happened, Harry? What happened? Is he ill? But you can cure him, can’t you?” Colin had run down from his seat and was now dancing alongside them as they left the field. Ron gave a huge heave and more slugs dribbled down his front. “Oooh,” said Colin, fascinated and raising his camera. “Can you hold him still, Harry?”

Most readers could figure out that this was Colin Creevey speaking, even if his name hadn’t been mentioned in the passage.

This is because Colin Creevey is the only character who speaks with such extreme enthusiasm, even at a time when Ron is belching slugs.

This snippet of written dialogue does a great job of showing us Colin’s personality and how much he worships his hero Harry.

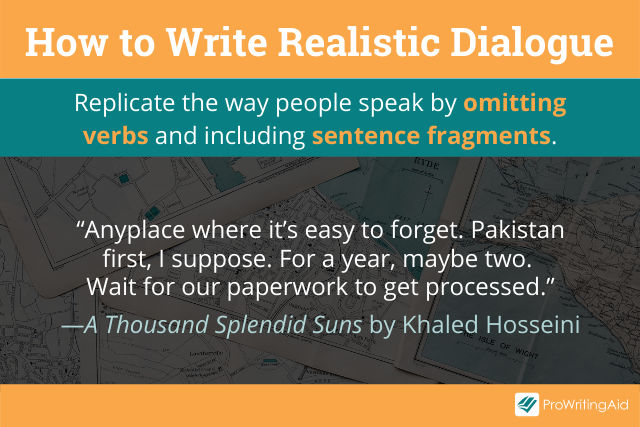

Dialogue Example #2: How to Write Realistic Dialogue

Here’s an example of how to write dialogue that feels realistic from A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini.

“As much as I love this land, some days I think about leaving it,” Babi said. “Where to?” “Anyplace where it’s easy to forget. Pakistan first, I suppose. For a year, maybe two. Wait for our paperwork to get processed.” “And then?” “And then, well, it is a big world. Maybe America. Somewhere near the sea. Like California.”

Notice the punctuation and grammar that these two characters use when they speak.

There are many sentence fragments in this conversation like, “Anyplace where it’s easy to forget.” and “Somewhere near the sea.”

Babi often omits the verbs from his sentences, just like people do in real life. He speaks in short fragments instead of long, flowing paragraphs.

This dialogue shows who Babi is and feels similar to the way a real person would talk, while still remaining concise.

Dialogue Example #3: How to Simplify Your Dialogue Tags

Here’s an example of effective dialogue tags in Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier.

In this passage, the narrator’s been caught exploring the forbidden west wing of her new husband’s house, and she’s trying to make excuses for being there.

“I lost my way,” I said, “I was trying to find my room.” “You have come to the opposite side of the house,” she said; “this is the west wing.” “Yes, I know,” I said. “Did you go into any of the rooms?” she asked me. “No,” I said. “No, I just opened a door, I did not go in. Everything was dark, covered up in dust sheets. I’m sorry. I did not mean to disturb anything. I expect you like to keep all this shut up.” “If you wish to open up the rooms I will have it done,” she said; “you have only to tell me. The rooms are all furnished, and can be used.” “Oh, no,” I said. “No. I did not mean you to think that.”

In this passage, the only dialogue tags Du Maurier uses are “I said,” “she said,” and “she asked.”

Even so, you can feel the narrator’s dread and nervousness. Her emotions are conveyed through what she actually says, rather than through the dialogue tags.

This is a splendid example of evocative speech that doesn’t need fancy dialogue tags to make it come to life.

Dialogue Example #4: How to Balance Speech with Action

Let’s look at a passage from The Princess Bride by William Goldman, where dialogue is melded with physical action.

With a smile the hunchback pushed the knife harder against Buttercup’s throat. It was about to bring blood. “If you wish her dead, by all means keep moving," Vizzini said. The man in black froze. “Better,” Vizzini nodded. No sound now beneath the moonlight. “I understand completely what you are trying to do,” the Sicilian said finally, “and I want it quite clear that I resent your behavior. You are trying to kidnap what I have rightfully stolen, and I think it quite ungentlemanly.” “Let me explain,” the man in black began, starting to edge forward. “You’re killing her!” the Sicilian screamed, shoving harder with the knife. A drop of blood appeared now at Buttercup’s throat, red against white.

In this passage, William Goldman brings our attention seamlessly from the action to the dialogue and back again.

This makes the scene twice as interesting, because we’re paying attention not just to what Vizzini and the man in black are saying, but also to what they’re doing.

This is a great way to keep tension high and move the plot forward.

Dialogue Example #5: How to Write Conversations with Subtext

This example from Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card shows how to write dialogue with subtext.

Here is the scene when Ender and his sister Valentine are reunited for the first time, after Ender’s spent most of his childhood away from home training to be a soldier.

Ender didn’t wave when she walked down the hill toward him, didn’t smile when she stepped onto the floating boat slip. But she knew that he was glad to see her, knew it because of the way his eyes never left her face. “You’re bigger than I remembered,” she said stupidly. “You too,” he said. “I also remembered that you were beautiful.” “Memory does play tricks on us.” “No. Your face is the same, but I don’t remember what beautiful means anymore. Come on. Let’s go out into the lake.”

In this scene, we can tell that Valentine missed her brother terribly, and that Ender went through a lot of trauma at Battle School, without either of them saying it outright.

The conversation could have started with Valentine saying “I missed you,” but instead, she goes for a subtler opening: “You’re bigger than I remembered.”

Similarly, Ender could say “You have no idea what I’ve been through,” but instead he says, “I don’t remember what beautiful means anymore.”

We can deduce what each of these characters is thinking and feeling from what they say and from what they leave unsaid.

Dialogue Example #6: How to Show, Not Tell

Let’s look at an example from The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss. This scene is the story’s first introduction of the ancient creatures called the Chandrian.

“I didn’t know the Chandrian were demons,” the boy said. “I’d heard—” “They ain’t demons,” Jake said firmly. “They were the first six people to refuse Tehlu’s choice of the path, and he cursed them to wander the corners—” “Are you telling this story, Jacob Walker?” Cob said sharply. “Cause if you are, I’ll just let you get on with it.” The two men glared at each other for a long moment. Eventually Jake looked away, muttering something that could, conceivably, have been an apology. Cob turned back to the boy. “That’s the mystery of the Chandrian,” he explained. “Where do they come from? Where do they go after they’ve done their bloody deeds? Are they men who sold their souls? Demons? Spirits? No one knows.” Cob shot Jake a profoundly disdainful look. “Though every half-wit claims he knows...”

The three characters taking part in this conversation all know what the Chandrian are.

Imagine if Cob had said “As we all know, the Chandrian are mysterious demon-spirits.” We would feel like he was talking to us, not to the two other characters.

Instead, Rothfuss has all three characters try to explain their own understanding of what the Chandrian are, and then shoot each other’s explanations down.

When Cob reprimands Jake for interrupting him and then calls him a half-wit for claiming to know what he’s talking about, it feels like a realistic interaction.

This is a clever way for Rothfuss to introduce the Chandrian in a believable way.

Dialogue Example #7: How to Keep Your Dialogue Concise

Here’s an example of concise dialogue from The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger.

“Do you blame me for flunking you, boy?” he said. “No, sir! I certainly don’t,” I said. I wished to hell he’d stop calling me “boy” all the time. He tried chucking my exam paper on the bed when he was through with it. Only, he missed again, naturally. I had to get up again and pick it up and put it on top of the Atlantic Monthly. It’s boring to do that every two minutes. “What would you have done in my place?” he said. “Tell the truth, boy.” Well, you could see he really felt pretty lousy about flunking me. So I shot the bull for a while. I told him I was a real moron, and all that stuff. I told him how I would’ve done exactly the same thing if I’d been in his place, and how most people didn’t appreciate how tough it is being a teacher. That kind of stuff. The old bull.

Here, the last paragraph diverges from the prior ones. After the teacher says “Tell the truth, boy,” the rest of the conversation is summarized, rather than shown.

The summary of what the narrator says in the last paragraph—“I told him I was a real moron, and all that stuff”—serves to hammer home that this is the type of “old bull” that the narrator has fed to his teachers over and over before.

It doesn’t need to be shown because it’s not important to the narrator—it’s just “all that stuff.”

Salinger could have written out the entire conversation in dialogue, but instead he kept the dialogue concise.

Final Words

Now you know how to write clear, effective dialogue! Start with the basic rules for dialogue and try implementing the more advanced tips as you go.

What are your favorite dialogue tips? Let us know in the comments below.

Do you know how to craft memorable, compelling characters? Download this free book now:

Creating Legends: How to Craft Characters Readers Adore… or Despise!

This guide is for all the writers out there who want to create compelling, engaging, relatable characters that readers will adore… or despise., learn how to invent characters based on actions, motives, and their past..

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Hannah Yang

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via:

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Jul 24, 2023

15 Examples of Great Dialogue (And Why They Work So Well)

About the author.

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

About Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

Great dialogue is hard to pin down, but you know it when you hear or see it. In the earlier parts of this guide, we showed you some well-known tips and rules for writing dialogue. In this section, we'll show you those rules in action with 15 examples of great dialogue, breaking down exactly why they work so well.

1. Barbara Kingsolver, Unsheltered

In the opening of Barbara Kingsolver’s Unsheltered, we meet Willa Knox, a middle-aged and newly unemployed writer who has just inherited a ramshackle house.

“The simplest thing would be to tear it down,” the man said. “The house is a shambles.” She took this news as a blood-rush to the ears: a roar of peasant ancestors with rocks in their fists, facing the evictor. But this man was a contractor. Willa had called him here and she could send him away. She waited out her panic while he stood looking at her shambles, appearing to nurse some satisfaction from his diagnosis. She picked out words. “It’s not a living thing. You can’t just pronounce it dead. Anything that goes wrong with a structure can be replaced with another structure. Am I right?” “Correct. What I am saying is that the structure needing to be replaced is all of it. I’m sorry. Your foundation is nonexistent.”

Alfred Hitchcock once described drama as "life with the boring bits cut out." In this passage, Kingsolver cuts out the boring parts of Willa's conversation with her contractor and brings us right to the tensest, most interesting part of the conversation.

By entering their conversation late , the reader is spared every tedious detail of their interaction.

Instead of a blow-by-blow account of their negotiations (what she needs done, when he’s free, how she’ll be paying), we’re dropped right into the emotional heart of the discussion. The novel opens with the narrator learning that the home she cherishes can’t be salvaged.

By starting off in the middle of (relatively obscure) dialogue, it takes a moment for the reader to orient themselves in the story and figure out who is speaking, and what they’re speaking about. This disorientation almost mirrors Willa’s own reaction to the bad news, as her expectations for a new life in her new home are swiftly undermined.

FREE COURSE

How to Write Believable Dialogue

Master the art of dialogue in 10 five-minute lessons.

2. Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

In the first piece of dialogue in Pride and Prejudice , we meet Mr and Mrs Bennet, as Mrs Bennet attempts to draw her husband into a conversation about neighborhood gossip.

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?” Mr. Bennet replied that he had not. “But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.” Mr. Bennet made no answer. “Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently. “You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.” This was invitation enough. “Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.”

Austen’s dialogue is always witty, subtle, and packed with character. This extract from Pride and Prejudice is a great example of dialogue being used to develop character relationships .

We instantly learn everything we need to know about the dynamic between Mr and Mrs Bennet’s from their first interaction: she’s chatty, and he’s the beleaguered listener who has learned to entertain her idle gossip, if only for his own sake (hence “you want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it”).

There is even a clear difference between the two characters visually on the page: Mr Bennet responds in short sentences, in simple indirect speech, or not at all, but this is “invitation enough” for Mrs Bennet to launch into a rambling and extended response, dominating the conversation in text just as she does audibly.

The fact that Austen manages to imbue her dialogue with so much character-building realism means we hardly notice the amount of crucial plot exposition she has packed in here. This heavily expository dialogue could be a drag to get through, but Austen’s colorful characterization means she slips it under the radar with ease, forwarding both our understanding of these people and the world they live in simultaneously.

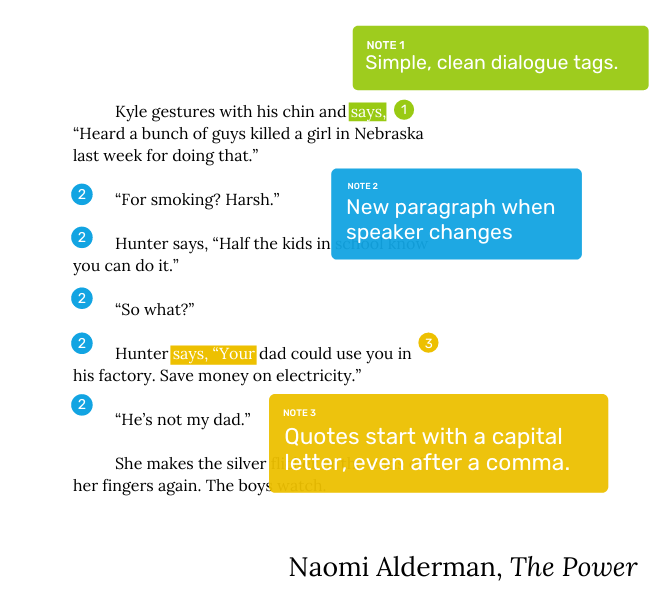

3. Naomi Alderman, The Power

In The Power , young women around the world suddenly find themselves capable of generating and controlling electricity. In this passage, between two boys and a girl who just used those powers to light her cigarette.

Kyle gestures with his chin and says, “Heard a bunch of guys killed a girl in Nebraska last week for doing that.” “For smoking? Harsh.” Hunter says, “Half the kids in school know you can do it.” “So what?” Hunter says, “Your dad could use you in his factory. Save money on electricity.” “He’s not my dad.” She makes the silver flicker at the ends of her fingers again. The boys watch.

Alderman here uses a show, don’t tell approach to expositional dialogue . Within this short exchange, we discover a lot about Allie, her personal circumstances, and the developing situation elsewhere. We learn that women are being punished harshly for their powers; that Allie is expected to be ashamed of those powers and keep them a secret, but doesn’t seem to care to do so; that her father is successful in industry; and that she has a difficult relationship with him. Using dialogue in this way prevents info-dumping backstory all at once, and instead helps us learn about the novel’s world in a natural way.

Show, Don't Tell

Master the golden rule of writing in 10 five-minute lessons.

4. Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go

Here, friends Tommy and Kathy have a conversation after Tommy has had a meltdown. After being bullied by a group of boys, he has been stomping around in the mud, the precise reaction they were hoping to evoke from him.

“Tommy,” I said, quite sternly. “There’s mud all over your shirt.” “So what?” he mumbled. But even as he said this, he looked down and noticed the brown specks, and only just stopped himself crying out in alarm. Then I saw the surprise register on his face that I should know about his feelings for the polo shirt. “It’s nothing to worry about.” I said, before the silence got humiliating for him. “It’ll come off. If you can’t get it off yourself, just take it to Miss Jody.” He went on examining his shirt, then said grumpily, “It’s nothing to do with you anyway.”

This episode from Never Let Me Go highlights the power of interspersing action beats within dialogue . These action beats work in several ways to add depth to what would otherwise be a very simple and fairly nondescript exchange. Firstly, they draw attention to the polo shirt, and highlight its potential significance in the plot. Secondly, they help to further define Kathy’s relationship with Tommy.

We learn through Tommy’s surprised reaction that he didn’t think Kathy knew how much he loved his seemingly generic polo shirt. This moment of recognition allows us to see that she cares for him and understands him more deeply than even he realized. Kathy breaking the silence before it can “humiliate” Tommy further emphasizes her consideration for him. While the dialogue alone might make us think Kathy is downplaying his concerns with pragmatic advice, it is the action beats that tell the true story here.

5. J R R Tolkien, The Hobbit

The eponymous hobbit Bilbo is engaged in a game of riddles with the strange creature Gollum.

"What have I got in my pocket?" he said aloud. He was talking to himself, but Gollum thought it was a riddle, and he was frightfully upset. "Not fair! not fair!" he hissed. "It isn't fair, my precious, is it, to ask us what it's got in its nassty little pocketses?" Bilbo seeing what had happened and having nothing better to ask stuck to his question. "What have I got in my pocket?" he said louder. "S-s-s-s-s," hissed Gollum. "It must give us three guesseses, my precious, three guesseses." "Very well! Guess away!" said Bilbo. "Handses!" said Gollum. "Wrong," said Bilbo, who had luckily just taken his hand out again. "Guess again!" "S-s-s-s-s," said Gollum, more upset than ever.

Tolkein’s dialogue for Gollum is a masterclass in creating distinct character voices . By using a repeated catchphrase (“my precious”) and unconventional spelling and grammar to reflect his unusual speech pattern, Tolkien creates an idiosyncratic, unique (and iconic) speech for Gollum. This vivid approach to formatting dialogue, which is almost a transliteration of Gollum's sounds, allows readers to imagine his speech pattern and practically hear it aloud.

We wouldn’t recommend using this extreme level of idiosyncrasy too often in your writing — it can get wearing for readers after a while, and Tolkien deploys it sparingly, as Gollum’s appearances are limited to a handful of scenes. However, you can use Tolkien’s approach as inspiration to create (slightly more subtle) quirks of speech for your own characters.

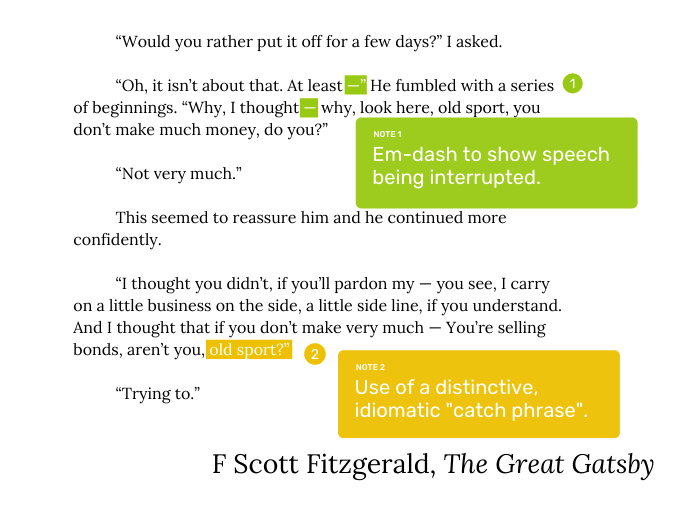

6. F Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

The narrator, Nick has just done his new neighbour Gatsby a favor by inviting his beloved Daisy over to tea. Perhaps in return, Gatsby then attempts to make a shady business proposition.

“There’s another little thing,” he said uncertainly, and hesitated. “Would you rather put it off for a few days?” I asked. “Oh, it isn’t about that. At least —” He fumbled with a series of beginnings. “Why, I thought — why, look here, old sport, you don’t make much money, do you?” “Not very much.” This seemed to reassure him and he continued more confidently. “I thought you didn’t, if you’ll pardon my — you see, I carry on a little business on the side, a little side line, if you understand. And I thought that if you don’t make very much — You’re selling bonds, aren’t you, old sport?” “Trying to.”

This dialogue from The Great Gatsby is a great example of how to make dialogue sound natural. Gatsby tripping over his own words (even interrupting himself , as marked by the em-dashes) not only makes his nerves and awkwardness palpable but also mimics real speech. Just as real people often falter and make false starts when they’re speaking off the cuff, Gatsby too flounders, giving us insight into his self-doubt; his speech isn’t polished and perfect, and neither is he despite all his efforts to appear so.

Fitzgerald also creates a distinctive voice for Gatsby by littering his speech with the character's signature term of endearment, “old sport”. We don’t even really need dialogue markers to know who’s speaking here — a sign of very strong characterization through dialogue.

7. Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarlet

In this first meeting between the two heroes of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, John is introduced to Sherlock while the latter is hard at work in the lab.

“How are you?” he said cordially, gripping my hand with a strength for which I should hardly have given him credit. “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.” “How on earth did you know that?” I asked in astonishment. “Never mind,” said he, chuckling to himself. “The question now is about hemoglobin. No doubt you see the significance of this discovery of mine?” “It is interesting, chemically, no doubt,” I answered, “but practically— ” “Why, man, it is the most practical medico-legal discovery for years. Don’t you see that it gives us an infallible test for blood stains. Come over here now!” He seized me by the coat-sleeve in his eagerness, and drew me over to the table at which he had been working. “Let us have some fresh blood,” he said, digging a long bodkin into his finger, and drawing off the resulting drop of blood in a chemical pipette. “Now, I add this small quantity of blood to a litre of water. You perceive that the resulting mixture has the appearance of pure water. The proportion of blood cannot be more than one in a million. I have no doubt, however, that we shall be able to obtain the characteristic reaction.” As he spoke, he threw into the vessel a few white crystals, and then added some drops of a transparent fluid. In an instant the contents assumed a dull mahogany colour, and a brownish dust was precipitated to the bottom of the glass jar. “Ha! ha!” he cried, clapping his hands, and looking as delighted as a child with a new toy. “What do you think of that?”

This passage uses a number of the key techniques for writing naturalistic and exciting dialogue, including characters speaking over one another and the interspersal of action beats.

Sherlock cutting off Watson to launch into a monologue about his blood experiment shows immediately where Sherlock’s interest lies — not in small talk, or the person he is speaking to, but in his own pursuits, just like earlier in the conversation when he refuses to explain anything to John and is instead self-absorbedly “chuckling to himself”. This helps establish their initial rapport (or lack thereof) very quickly.

Breaking up that monologue with snippets of him undertaking the forensic tests allows us to experience the full force of his enthusiasm over it without having to read an uninterrupted speech about the ins and outs of a science experiment.

Starting to think you might like to read some Sherlock? Check out our guide to the Sherlock Holmes canon !

8. Brandon Taylor, Real Life

Here, our protagonist Wallace is questioned by Ramon, a friend-of-a-friend, over the fact that he is considering leaving his PhD program.

Wallace hums. “I mean, I wouldn’t say that I want to leave, but I’ve thought about it, sure.” “Why would you do that? I mean, the prospects for… black people, you know?” “What are the prospects for black people?” Wallace asks, though he knows he will be considered the aggressor for this question.

Brandon Taylor’s Real Life is drawn from the author’s own experiences as a queer Black man, attempting to navigate the unwelcoming world of academia, navigating the world of academia, and so it’s no surprise that his dialogue rings so true to life — it’s one of the reasons the novel is one of our picks for must-read books by Black authors .

This episode is part of a pattern where Wallace is casually cornered and questioned by people who never question for a moment whether they have the right to ambush him or criticize his choices. The use of indirect dialogue at the end shows us this is a well-trodden path for Wallace: he has had this same conversation several times, and can pre-empt the exact outcome.

This scene is also a great example of the dramatic significance of people choosing not to speak. The exchange happens in front of a big group, but — despite their apparent discomfort — nobody speaks up to defend Wallace, or to criticize Ramon’s patronizing microaggressions. Their silence is deafening, and we get a glimpse of Ramon’s isolation due to the complacency of others, all due to what is not said in this dialogue example.

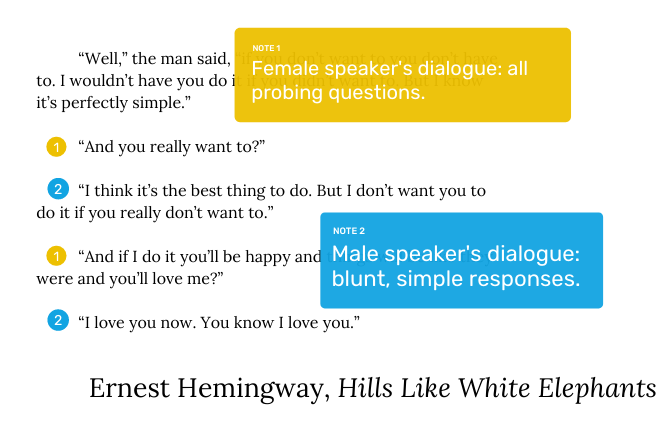

9. Ernest Hemingway, Hills Like White Elephants

In this short story, an unnamed man and a young woman discuss whether or not they should terminate a pregnancy while sitting on a train platform.

“Well,” the man said, “if you don’t want to you don’t have to. I wouldn’t have you do it if you didn’t want to. But I know it’s perfectly simple.” “And you really want to?” “I think it’s the best thing to do. But I don’t want you to do it if you really don’t want to.” “And if I do it you’ll be happy and things will be like they were and you’ll love me?” “I love you now. You know I love you.” “I know. But if I do it, then it will be nice again if I say things are like white elephants, and you’ll like it?” “I’ll love it. I love it now but I just can’t think about it. You know how I get when I worry.” “If I do it you won’t ever worry?” “I won’t worry about that because it’s perfectly simple.”

This example of dialogue from Hemingway’s short story Hills Like White Elephants moves at quite a clip. The conversation quickly bounces back and forth between the speakers, and the call-and-response format of the woman asking and the man answering is effective because it establishes a clear dynamic between the two speakers: the woman is the one seeking reassurance and trying to understand the man’s feelings, while he is the one who is ultimately in control of the situation.

Note the sparing use of dialogue markers: this minimalist approach keeps the dialogue brisk, and we can still easily understand who is who due to the use of a new paragraph when the speaker changes .

Like this classic author’s style? Head over to our selection of the 11 best Ernest Hemingway books .

10. Madeline Miller, Circe

In Madeline Miller’s retelling of Greek myth, we witness a conversation between the mythical enchantress Circe and Telemachus (son of Odysseus).

“You do not grieve for your father?” “I do. I grieve that I never met the father everyone told me I had.” I narrowed my eyes. “Explain.” “I am no storyteller.” “I am not asking for a story. You have come to my island. You owe me truth.” A moment passed, and then he nodded. “You will have it.”

This short and punchy exchange hits on a lot of the stylistic points we’ve covered so far. The conversation is a taut tennis match between the two speakers as they volley back and forth with short but impactful sentences, and unnecessary dialogue tags have been shaved off . It also highlights Circe’s imperious attitude, a result of her divine status. Her use of short, snappy declaratives and imperatives demonstrates that she’s used to getting her own way and feels no need to mince her words.

11. Andre Aciman, Call Me By Your Name

This is an early conversation between seventeen-year-old Elio and his family’s handsome new student lodger, Oliver.

What did one do around here? Nothing. Wait for summer to end. What did one do in the winter, then? I smiled at the answer I was about to give. He got the gist and said, “Don’t tell me: wait for summer to come, right?” I liked having my mind read. He’d pick up on dinner drudgery sooner than those before him. “Actually, in the winter the place gets very gray and dark. We come for Christmas. Otherwise it’s a ghost town.” “And what else do you do here at Christmas besides roast chestnuts and drink eggnog?” He was teasing. I offered the same smile as before. He understood, said nothing, we laughed. He asked what I did. I played tennis. Swam. Went out at night. Jogged. Transcribed music. Read. He said he jogged too. Early in the morning. Where did one jog around here? Along the promenade, mostly. I could show him if he wanted. It hit me in the face just when I was starting to like him again: “Later, maybe.”

Dialogue is one of the most crucial aspects of writing romance — what’s a literary relationship without some flirty lines? Here, however, Aciman gives us a great example of efficient dialogue. By removing unnecessary dialogue and instead summarizing with narration, he’s able to confer the gist of the conversation without slowing down the pace unnecessarily. Instead, the emphasis is left on what’s unsaid, the developing romantic subtext.

Furthermore, the fact that we receive this scene in half-reported snippets rather than as an uninterrupted transcript emphasizes the fact that this is Elio’s own recollection of the story, as the manipulation of the dialogue in this way serves to mimic the nostalgic haziness of memory.

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

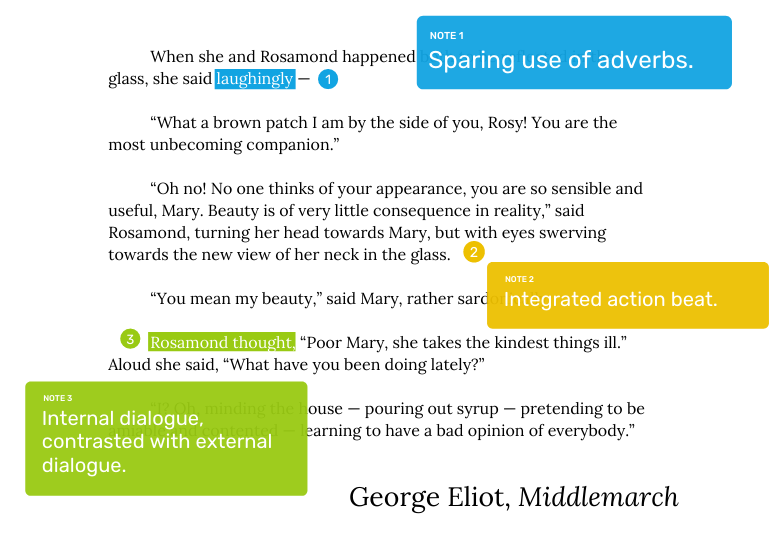

12. George Eliot, Middlemarch

Two of Eliot’s characters, Mary and Rosamond, are out shopping,

When she and Rosamond happened both to be reflected in the glass, she said laughingly — “What a brown patch I am by the side of you, Rosy! You are the most unbecoming companion.” “Oh no! No one thinks of your appearance, you are so sensible and useful, Mary. Beauty is of very little consequence in reality,” said Rosamond, turning her head towards Mary, but with eyes swerving towards the new view of her neck in the glass. “You mean my beauty,” said Mary, rather sardonically. Rosamond thought, “Poor Mary, she takes the kindest things ill.” Aloud she said, “What have you been doing lately?” “I? Oh, minding the house — pouring out syrup — pretending to be amiable and contented — learning to have a bad opinion of everybody.”

This excerpt, a conversation between the level-headed Mary and vain Rosamond, is an example of dialogue that develops character relationships naturally. Action descriptors allow us to understand what is really happening in the conversation.

Whilst the speech alone might lead us to believe Rosamond is honestly (if clumsily) engaging with her friend, the description of her simultaneously gazing at herself in a mirror gives us insight not only into her vanity, but also into the fact that she is not really engaged in her conversation with Mary at all.

The use of internal dialogue cut into the conversation (here formatted with quotation marks rather than the usual italics ) lets us know what Rosamond is actually thinking, and the contrast between this and what she says aloud is telling. The fact that we know she privately realizes she has offended Mary, but quickly continues the conversation rather than apologizing, is emphatic of her character. We get to know Rosamond very well within this short passage, which is a hallmark of effective character-driven dialogue.

13. John Steinbeck, The Winter of our Discontent

Here, Mary (speaking first) reacts to her husband Ethan’s attempts to discuss his previous experiences as a disciplined soldier, his struggles in subsequent life, and his feeling of impending change.

“You’re trying to tell me something.” “Sadly enough, I am. And it sounds in my ears like an apology. I hope it is not.” “I’m going to set out lunch.”

Steinbeck’s Winter of our Discontent is an acute study of alienation and miscommunication, and this exchange exemplifies the ways in which characters can fail to communicate, even when they’re speaking. The pair speaking here are trapped in a dysfunctional marriage which leaves Ethan feeling isolated, and part of his loneliness comes from the accumulation of exchanges such as this one. Whenever he tries to communicate meaningfully with his wife, she shuts the conversation down with a complete non sequitur.

We expect Mary’s “you’re trying to tell me something” to be followed by a revelation, but Ethan is not forthcoming in his response, and Mary then exits the conversation entirely. Nothing is communicated, and the jarring and frustrating effect of having our expectations subverted goes a long way in mirroring Ethan’s own frustration.

Just like Ethan and Mary, we receive no emotional pay-off, and this passage of characters talking past one another doesn’t further the plot as we hope it might, but instead gives us insight into the extent of these characters’ estrangement.

14. Bret Easton Ellis , Less Than Zero

The disillusioned main character of Bret Easton Ellis’ debut novel, Clay, here catches up with a college friend, Daniel, whom he hasn’t seen in a while.

He keeps rubbing his mouth and when I realize that he’s not going to answer me, I ask him what he’s been doing. “Been doing?” “Yeah.” “Hanging out.” “Hanging out where?” “Where? Around.”

Less Than Zero is an elegy to conversation, and this dialogue is an example of the many vacuous exchanges the protagonist engages in, seemingly just to fill time. The whole book is deliberately unpoetic and flat, and depicts the lives of disaffected youths in 1980s LA. Their misguided attempts to fill the emptiness within them with drink and drugs are ultimately fruitless, and it shows in their conversations: in truth, they have nothing to say to one another at all.

This utterly meaningless exchange would elsewhere be considered dead weight to a story. Here, rather than being fat in need of trimming, the empty conversation is instead thematically resonant.

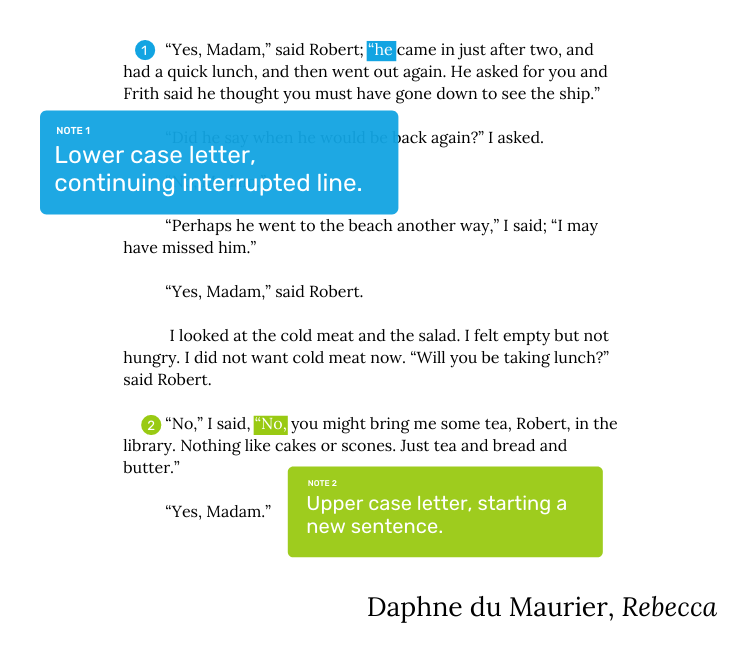

15. Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca

The young narrator of du Maurier’s classic gothic novel here has a strained conversation with Robert, one of the young staff members at her new husband’s home, the unwelcoming Manderley.

“Has Mr. de Winter been in?” I said. “Yes, Madam,” said Robert; “he came in just after two, and had a quick lunch, and then went out again. He asked for you and Frith said he thought you must have gone down to see the ship.” “Did he say when he would be back again?” I asked. “No, Madam.” “Perhaps he went to the beach another way,” I said; “I may have missed him.” “Yes, Madam,” said Robert. I looked at the cold meat and the salad. I felt empty but not hungry. I did not want cold meat now. “Will you be taking lunch?” said Robert. “No,” I said, “No, you might bring me some tea, Robert, in the library. Nothing like cakes or scones. Just tea and bread and butter.” “Yes, Madam.”

We’re including this one in our dialogue examples list to show you the power of everything Du Maurier doesn’t do: rather than cycling through a ton of fancy synonyms for “said”, she opts for spare dialogue and tags.

This interaction's cold, sparse tone complements the lack of warmth the protagonist feels in the moment depicted here. By keeping the dialogue tags simple , the author ratchets up the tension — without any distracting flourishes taking the reader out of the scene. The subtext of the conversation is able to simmer under the surface, and we aren’t beaten over the head with any stage direction extras.

The inclusion of three sentences of internal dialogue in the middle of the dialogue (“I looked at the cold meat and the salad. I felt empty but not hungry. I did not want cold meat now.”) is also a masterful touch. What could have been a single sentence is stretched into three, creating a massive pregnant pause before Robert continues speaking, without having to explicitly signpost one. Manipulating the pace of dialogue in this way and manufacturing meaningful silence is a great way of adding depth to a scene.

Phew! We've been through a lot of dialogue, from first meetings to idle chit-chat to confrontations, and we hope these dialogue examples have been helpful in illustrating some of the most common techniques.

If you’re looking for more pointers on creating believable and effective dialogue, be sure to check out our course on writing dialogue. Or, if you find you learn better through examples, you can look at our list of 100 books to read before you die — it’s packed full of expert storytellers who’ve honed the art of dialogue.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your stories to life

Our free writing app lets you set writing goals and track your progress, so you can finally write that book!

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Writing Dialogue [20 Best Examples + Formatting Guide]

Have you ever found yourself cringing at clunky dialogue while reading a book or watching a movie? I know I have.

It’s like nails on a chalkboard, completely ruining the experience. But on the flip side, well-written dialogue can transform a story. It’s the magic that makes characters leap off the page, immersing us in their world.

As a writer, I’m fascinated by the mechanics of great dialogue.

So here are 20 of the best examples of writing dialogue that brings your story to life.

Example 1: Dialogue that Reveals Character

Table of Contents

One of the most powerful functions of dialogue is to shed light on your characters’ personalities.

The way they speak – their word choice, tone, even their hesitations – can tell us so much about who they are. Check out this example:

“Look, I ain’t gonna sugarcoat this,” the detective growled, his knuckles whitening as he gripped the chair. “You were spotted leaving the scene, and the murder weapon’s got your prints all over it.”

Without any lengthy description, we get a sense of this detective as a no-nonsense, direct type of guy.

Example 2: Dialogue that Builds Tension

Dialogue can become this amazing tool to ratchet up the tension in a scene.

Short, clipped exchanges and carefully placed silences can leave the reader on the edge of their seat.

Here’s how it might play out:

“Do you hear that?” Sarah whispered. “Hear what?” A scratching noise echoed from the attic. Sarah’s eyes widened. “It’s coming back.”

The suspense is killing me just writing that!

Example 3: Dialogue that Drives the Plot

Conversations aren’t just about characters sitting around and chatting.

Great dialogue should actively push the story forward. It can set up a conflict, reveal key information, or change the course of events.

Take a look at this:

“I’ve made my decision,” the king declared, the crown heavy on his brow. “We go to war.”

A single line, and the whole trajectory of the story shifts.

Formatting Tips: The Basics

Now, before we get carried away, let’s cover some essential dialogue formatting rules.

Think of these as the grammar of a good conversation.

- Quotation Marks: Yep, those little squiggles are your best friend. They signal to the reader: “Hey! Someone’s talking!”

- New Speaker, New Paragraph: Whenever a different character starts talking, give them a new paragraph. It’s all about keeping things easy to follow.

- Dialogue Tags: These are the little phrases like “he said” or “she replied.” Use them, but try not to overuse them. A well-placed action beat can often do a better job of showing who’s speaking.

Example 4: Dialogue that Creates Humor

Dialogue can be ridiculously funny when done well.

The key? Snappy exchanges, playful misunderstandings, and just a dash of absurdity. Consider this:

“I saw the weirdest thing at the grocery store today,” Tom said, “A woman arguing with a head of lettuce.” “Was she winning?” Lily asked, a grin playing on her lips.

You can almost hear the deadpan delivery, can’t you?

Example 5: Dialogue that Shows Relationships

The way characters speak to each other says a ton about the dynamics between them.

Is there warmth, hostility, an underlying power struggle? Dialogue can paint a crystal-clear picture. Imagine this exchange:

“You didn’t do the dishes again?” Sarah sighed, hands planted on her hips. “Aw, c’mon babe. I was busy,” Mike whined, avoiding her gaze.

We instantly sense the long-suffering tone from Sarah and the playful guilt from Mike.

Example 6: Dialogue with Subtext

The most interesting dialogue often has layers. What the characters say might not be exactly what they mean.

This is where subtext comes in – the unspoken thoughts and feelings bubbling beneath the surface.

Take this snippet:

“It’s a nice ring,” Emily said, her voice flat. “You don’t like it?” Mark’s brow furrowed. Emily shrugged. “It’s fine.”

Is Emily truly indifferent? Or is she masking disappointment, perhaps a sense of something not being quite right? Subtext makes us read between the lines.

Formatting Tips: Getting Fancy

Now, let’s spice things up with a few more advanced formatting tricks:

- Ellipses (…): These little dots are perfect for showing a character trailing off, hesitating, or searching for words. Example: “I…I don’t know what to say.”

- Em Dashes (—): These guys can interrupt a thought or indicate a sudden change in direction. Example: “I was going to apologize, but then — well, you’re still being a jerk.”

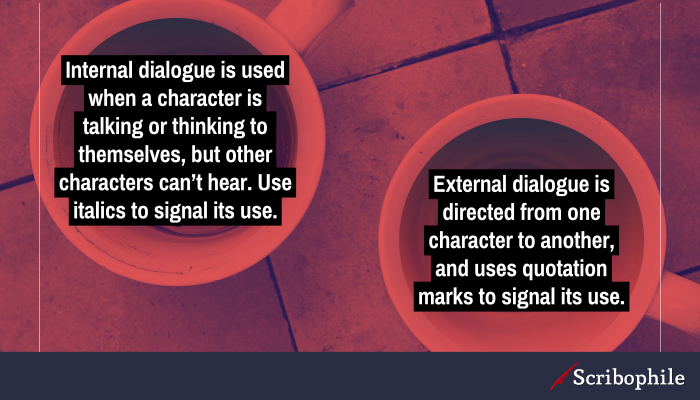

- Internal Dialogue: Instead of quotation marks, sometimes you’ll want to italicize a character’s inner thoughts. Example: Why did I say that? I’m such an idiot.

Cautionary Note

It’s important to remember: dialogue shouldn’t feel like an interrogation. Avoid rigid “question-answer, question-answer” patterns. Real conversations flow and meander naturally.

Example 7: Dialogue with Dialects and Accents

Regional dialects and accents can bring so much flavor to your characters, but it’s a delicate balance.

You want to add authenticity without it becoming a caricature or making it hard to understand.

Here’s a subtle example:

“Well, I’ll be darned,” drawled the farmer, squinting at the sky. “Looks like a storm’s brewin’.”

Notice how just a few word choices and a slight change in pronunciation hint at the speaker’s background.

Example 8: Dialogue in Groups

Writing conversations with more than two people can get chaotic fast. The key is clarity.

Here are a few tips:

- Strong Dialogue Tags: Sometimes, you need to be more specific than just “he said” or “she said”. Example: “Don’t be ridiculous,” scoffed Sarah.

- Action Beats: Break up chunks of dialogue with actions that show who’s speaking. Example: Tom slammed his fist on the table. “I won’t stand for this!”

Example 9: Dialogue Over the Phone (or Other Technology)

Conversations where characters aren’t physically together pose unique challenges.

You can’t rely on body language cues. Instead, focus on conveying tone and potential misunderstandings.

For instance:

“Hello?” Sarah’s voice crackled through the phone. A long pause. “Sarah, is that you?” “Mom? Why are you whispering?”

Instantly there’s a sense of distance and something not being quite right.

Example 10: Inner Monologue with a Twist

We often think of internal dialogue as a single character reflecting, but sometimes our inner voices can argue.

This can be a powerful way to showcase internal conflict.

Here’s how it might look:

You should just tell him how you feel, one voice chimed. Are you crazy? the other shrieked back. He’ll never feel the same way .

This creates a vivid picture of a character torn between opposing desires.

Example 11: Dialogue With a Manipulative Character

Manipulative characters often use language as a weapon.

They might use guilt trips, flattery, or veiled threats to get what they want.

Consider this:

“After everything I’ve done for you…” The old woman sighed, a flicker of disappointment in her eyes. “Well, I guess I shouldn’t expect gratitude.”

Notice how she doesn’t directly ask for anything, instead hinting at a debt, leaving the listener feeling uneasy and obligated.

Example 12: Dialogue Across Time Periods

If you’re writing historical fiction or anything with time travel elements, you’ll need to capture the distinct speech patterns of different eras.

Imagine this exchange:

“Gadzooks! What manner of contraption is this?” The Victorian gentleman exclaimed, staring in bewilderment at the smartphone. “It’s a phone,” the teenager replied, barely suppressing a laugh. “Let me show you.”

This little snippet highlights the potential for both humor and linguistic challenges when worlds collide.

Formatting Tip: Dialogue Without Tags

Sometimes, for a rapid-fire or dreamlike effect, you might want to ditch the “he said” or “she asked” altogether.

It’s a bold move, but it can be effective if done sparingly.

Check this out:

“Where are you going?” “Away.” “When will you be back?” “I don’t know.” “Please don’t leave me.”

This creates a sense of urgency, the raw exchange forcing us to focus solely on the words themselves.

Example 13: Dialogue that Shows Transformation

A great way to showcase how a character develops is through shifts in how they speak.

Maybe they become bolder, quieter, or their vocabulary changes.

Let’s see an example:

Scene 1: “I-I don’t know,” Emily whimpered, cowering in the corner. Scene 2 (Later in the story): “That’s it. I’m not taking this anymore!” Emily declared, her chin held high.

The dialogue itself reflects her transformation from victim to someone ready to stand up for herself.

Example 14: Dialogue that’s Just Plain Weird

It’s okay to get strange sometimes.

Absurdist humor or unsettling conversations can add a unique flavor to your story. Just be sure it fits the overall tone.

“Do you believe in cucumbers?” the man asked, his eyes wide and unblinking. “Excuse me?” “Cucumbers, my dear. Agents of the underground vegetable kingdom.”

This immediately creates a sense of oddness and perhaps a touch of unease. Is this guy crazy, or is there something more going on?

Example 15: Dialogue with a Purpose

Remember, good dialogue isn’t just about being entertaining.

It should move your story along. Here are some functions dialogue can serve:

- Providing Exposition: Sometimes, you need to inform the reader of backstory or world-building details. Trickle information through natural conversation rather than an information dump.

- Foreshadowing: Subtle hints within a conversation can foreshadow future events or create a sense of unease for the reader.

- Revealing a Twist: A single line of dialogue can completely flip the script and reframe everything that came before.

Example 16: Dialogue with Non-Verbal Elements

So much of communication happens beyond just words.

Sighs, laughs, and gestures can add richness to dialogue on the page.

“I’m fine,” she said, crossing her arms and looking away.

Notice how the body language contradicts her words, hinting at inner turmoil.

Example 17: Silence as Dialogue

Sometimes, what isn’t said is the most powerful thing of all.

A pregnant pause or a character refusing to speak can convey volumes.

Imagine this:

“So, will you help me or not?” Tom pleaded. Sarah stared at him, her lips a thin line. Finally, she turned and walked away.

The lack of a verbal response speaks louder than any words could.

Example 18: Dialogue With Humorous Effect

A well-timed O.S. voice can deliver a funny remark or punchline, undercutting the seriousness of a scene or taking a moment in an unexpected comedic direction.

INT. CLASSROOM – DAY The teacher drones on about the causes of the American Revolution, his voice as dull as the worn textbook in front of him. KEVIN tries to stifle his yawns, failing miserably. STUDENT (O.S.) Is he ever going to stop talking? My brain just turned to mush. Snickers ripple through the class. The teacher pauses, a look of annoyance flickering across his face. Kevin shoots a desperate look towards the source of the O.S. voice.

- Timing is everything. The best comedic O.S. lines act as a witty reaction to something else happening in a scene. The student’s comment comes right as Kevin’s boredom peaks.

- Subverting expectations is funny. The audience expects the scene to continue with a stern reprimand for speaking out of turn, but the script doesn’t give us that. This leaves room for further humor.

- Consider the tone of the voice – sarcastic, matter-of-fact, or outright whiny? This adds to the comedic effect.

Example 19: Dialogue With Unexpected Reveals

Think of this as a surprise twist using O.S. dialogue.

The audience (and maybe even some characters) are led to believe one thing, only for an O.S. voice to reveal something completely unexpected, shifting the scene’s dynamic.

INT. POLICE INTERROGATION ROOM – NIGHTDETECTIVE HARRIS paces in front of a nervous SUSPECT. Photos of the crime scene are scattered on the table. HARRIS Don’t lie to me! We’ve got witnesses who saw you at the scene. SUSPECT I – I swear, I had nothing to do with it! I was… I was with my girlfriend. Harris leans in, a triumphant glint in her eyes. She claps her hands sharply, startling the suspect. WOMAN (O.S.) That’s a lie! He was nowhere near me last night! The suspect whips around. His face pales as we hear the sound of the interrogation room door swinging open…

- The power lies in the build-up. The initial dialogue and the characters’ reactions should lead the audience to believe one outcome, making the O.S. interruption all the more impactful.

- Consider who speaks the O.S. line. Is it someone the audience recognizes, or a totally new character whose identity becomes a new mystery?

- Play with the proximity of the voice. Is it right outside the room, adding to the dramatic reveal as the door opens, or is it more distant – perhaps a voice over an intercom – for an even more unsettling effect?

Example 20: Dialogue With a “Haunted” Feeling

Explanation: O.S. can be used to create an eerie or unsettling atmosphere, particularly in horror or psychological thrillers. This could be unexplained voices, creepy whispers, or sounds that hint at a supernatural (or simply unnerving) presence.

INT. OLD MANSION – NIGHTSARAH explores the abandoned mansion, flashlight cutting through the thick dust. Cobwebs cling to every surface. A faint WHISPER drifts through the air, seeming to come from everywhere at once. Sarah freezes. VOICE (O.S.) Get out… leave this place… Sarah’s breath catches in her throat. She hesitantly follows the direction of the voice, her flashlight beam trembling.

- Less is more. The vaguer and more inexplicable the O.S. voice, the more chilling it becomes.

- Layer sounds for a full creepy effect. Combine whispers with unexpected bangs, creaks, or the faint sound of footsteps following behind Sarah.

- Play with audience expectations. If the script initially leads the audience to think the house is merely abandoned, the O.S. voices become that much more terrifying.

Here is a good video about writing dialogue:

Additional Dialogue Tips & Tricks

- Read Your Dialogue Aloud: This is the best way to catch awkward phrasing or unnatural rhythms. Our ears often pick up on what our eyes might miss.

- Less is More: Don’t feel the need to have every single interaction be profound. Sometimes a simple “Hey” or “Thanks” can do the job just fine.

- Eavesdrop: Paying attention to real-life conversations is fantastic research. Note the pauses, the filler words, the way people interrupt each other.

Final Thoughts: Writing Dialogue

Phew! We did it!

Does that feel like a solid collection of dialogue examples? We haven’t covered absolutely every scenario, but I hope these illustrate the vast potential within dialogue to bring your stories to life.

Read This Next:

- How To Use Action Tags in Dialogue: Ultimate Guide

- How Do Writers Fill a Natural Pause in Dialogue? [7 Crazy Effective Ways]

- Can You Start a Novel with Dialogue?

- How To Write A Southern Accent (17 Tips + Examples)

- How to Write a French Accent (13 Best Tips with Examples)

How to Format Dialogue: Complete Guide

Dialogue formatting matters. Whether you’re working on an essay, novel, or any other form of creative writing. Perfectly formatted dialogue makes your work more readable and engaging for the audience.

In this article, you’ll learn the dialogue formatting rules. Also, we’ll share examples of dialogue in essays for you to see the details.

What is a Dialogue Format?

Dialogue format is a writing form authors use to present characters' communication. It's common for play scripts, literature works, and other forms of storytelling.

A good format helps the audience understand who is speaking and what they say. It makes the communication clear and enjoyable. In dialogue writing, we follow the basic grammar rules like punctuation and capitalization. They help us illustrate the speaker’s ideas.

General Rules to Follow When Formatting a Dialogue

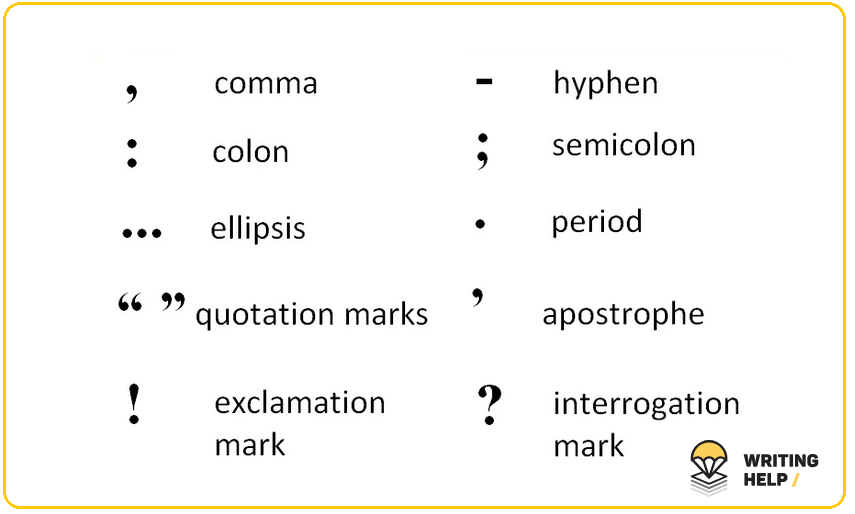

Dialogue writing is an essential skill for both professionals and scholars . It shows your ability to express the issues and ideas of other people in different setups. The core rules of formatting are about punctuation. So, below is a quick reminder on punctuation marks’ names:

And now, to practice.

Please follow these rules for proper dialogue formatting:

- Use quotation marks. Enclose the speaker’s words in double quotations. It helps readers distinguish between a character’s speech and a narrator’s comments.

- Place punctuation inside quotation marks. All punctuation like commas, exclamations, or interrogation marks, go inside the double quotations.

- Keep dialogue tags behind quotation marks. A dialogue tag is (1) words framing direct speech to convey the context and emotions of a conversation. For example, in (“I can’t believe this is you,” she replied.), the dialogue tag is “she replied.”

- Use an ellipsis or em-dashes for pauses or interruptions. To show interruptions or pauses, end phrases with ellipses inside quotations. Em-dashes go outside quotations. No other extra marks are necessary here.

- Remember a character’s voice. Ensure that each character’s phrases reflect their background and personality.

5 More Rules to Know (+ Examples of Dialogue)

For proper formatting of dialogue in writing, stick to the following rules:

1. Each speaker’s saying comes in a new paragraph

Begin a new paragraph whenever a new character starts speaking. It allows you to differentiate speakers and make their conversation look more organized. (2)

“Has Mr. de Winter been in?” I said. “Yes, Madam,” said Robert; “he came in just after two, and had a quick lunch, and then went out again. He asked for you and Frith said he thought you must have gone down to see the ship.” “Did he say when he would be back again?” I asked. “No, Madam.” — from Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

2. Separate dialogue tags with commas

When using dialogue tags ( e.g., “she said,” “he replied,”), separate them with commas.

For example:

“You’ve got to do something right now , ” Aaron said , “Mom is really hurting. She says you have to drive her to the hospital.” “Actually, Dad , ” said Caleb, sidling in with his catalog , “There’s someplace you can drive me, too.” “No, Caleb.” — from The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen

3. When quoting within dialogue, place single quotes

If a character cites somebody or something while speaking, we call it a reported dialogue. In this case, use single quotations within double ones you place for a direct speech. It will help readers see that it’s a quote.

John started to cry. “When you said, ‘I never wanted to meet you again in my life!’ It hurts my feelings.”

4. You can divide a character’s long speech into paragraphs

Dialogue writing is different when a person speaks for a longer time. It’s fine to divide it into shorter paragraphs. Ensure the proper quotation marks placing:

The first quotation mark goes at the beginning of the dialogue. Each later paragraph also starts with it until that direct speech ends.

The second quotation mark — the one “closing” the monologue — goes at the dialogue’s end.

Josphat took a deep breath and began. “ Here’s the things about lions. They’re dangerous creatures. They only know how to kill. Have you ever seen a lion in an open area? Probably not. Because if you had you’d be dead now. “ I saw a lion once. I was fetching firewood to cook lunch. All of a sudden I found myself face to face with a lion. My heart stopped. I knew it was my end on earth. If it wasn’t the poachers we wouldn’t be having this talk. ”

Yet, you can keep a long text as a whole by adding some context with dialogue tags. Like here:

As you can see, there’s no quotation mark at the end of the paragraph in red. It’s because the next “Ha! ha!” paragraph continues the character’s speech.

5. Use action beats

Describe actions to provide context and keep readers engaged. Help them “hear” your characters. Punctuation also helps here: exclamation (!) or interrogation with exclamations (?!) demonstrate the corresponding tone of your narrative.

He slammed the door and shouted , “I can’t believe you did that ! “

Mistakes to Avoid When Formatting Dialogue

A good dialogue is a powerful instrument for a writer to show the character’s nature to the audience. Below are the mistakes to avoid in formatting if you want to reach that goal.

So, please don’t :

- Allow characters to speak for too long. Writing long paragraphs will bore the reader, making them skip through your speech. Short but sweet talk is the best. When writing, aim to be brief, dynamic, and purposeful. If your character speaks too much, generating opinion essays , ensure this speech makes sense and serves a bigger purpose.

- Overburden dialogue with exposition. Avoid telling the story background or building sophisticated words in your characters’ speeches. Instead, reveal the narrative content in small bursts and blend it around the rest of the prose. Convey it through your character’s actions and thoughts rather than summaries and explanations.

- Create rhetorical flourishes. Make your characters sound natural. Let them speak the way they’d do if they were real people. Consider their age, profession, and cultural background — and choose lexical items that fit them most.

- Use repetitive dialogue tags. Constant “he asked” and “she said” sounds monotonous. Diversify your tags: use power verbs, synonyms, and dialogue beats.

Frequently Asked Questions by Students

How to format dialogue in an essay.

Formatting a dialogue in an essay is tricky for most students. Here’s how to do it: Enclose the speaker’s words with double quotations and start every other character’s line from a new paragraph. Stick to the citation styles like APA or MLA to ensure credibility.

How to format dialogue in a novel?

A dialogue in a novel follows all the standard rules for clarity and readability. Ensure to use attributions, quotation marks, and paragraph format. It makes your dialogue flow, grabbing the reader’s attention.

How to format dialogue in a book?

Dialogue formatting in a book is critical for storytelling. It helps the audience distinguish the hero’s words. Follow the general rules we’ve discussed above:

Use double quotations and isolate dialogue tags with commas. Remember to place the discussion in blocks for better readability.

How to format dialogue between two characters?

A two-character dialogue offers the best way to prove successful formatting skills. Ensure you use action beats, quotations, and attribution tags. It allows readers to follow the conversation and understand it better.

What is the purpose of dialogue in a narrative essay?

Dialogue writing is the exchange of views between two or more people to reach a consensus. It reveals the character’s attitude and argumentation. Last but not least, it helps convey the descriptive nature of your narrative essay.

References:

- https://valenciacollege.edu/students/learning-support/winter-park/communications/documents/WritingDialogueCSSCTipSheet_Revised_.pdf

- https://www.ursinus.edu/live/files/1158-formatting-dialogue

- Essay samples

- Essay writing

- Writing tips

Recent Posts

- Writing the “Why Should Abortion Be Made Legal” Essay: Sample and Tips

- 3 Examples of Enduring Issue Essays to Write Yours Like a Pro

- Writing Essay on Friendship: 3 Samples to Get Inspired

- How to Structure a Leadership Essay (Samples to Consider)

- What Is Nursing Essay, and How to Write It Like a Pro

Write, learn, make friends, meet beta readers, and become the best writer you can be!

Join our writing group!

How to Write Dialogue: Rules, Examples, and 8 Tips for Engaging Dialogue

by Fija Callaghan

Fija Callaghan is an author, poet, and writing workshop leader. She has been recognized by a number of awards, including being shortlisting for the H. G. Wells Short Story Prize. She is the author of the short story collection Frail Little Embers , and her writing can be read in places like Seaside Gothic , Gingerbread House , and Howl: New Irish Writing . She is also a developmental editor with Fictive Pursuits. You can read more about her at fijacallaghan.com .

You’ll often hear fiction writers talking about “character-driven stories”—stories where the strengths, weaknesses, and aspirations of the central cast of characters stay with us long after the book is closed. But what drives character, and how do we create characters that leave long-lasting impressions?

The answer lies in dialogue : the device used by our characters to communicate with each other. Powerful dialogue can elevate a story and subtly reveal important information, but poorly written dialogue can send your work straight to the slush bin. Let’s look at what dialogue is in writing, how to properly format dialogue, and how to make your characters’ dialogue the best it can be.

What is dialogue in a story?

Dialogue is the verbal exchange between two or more characters. In most fiction, the exchange is in the form of a spoken conversation. However, conversations in a story can also be things like letters, text messages, telepathy, or even sign language. Any moment where two characters speak or connect with each other through their choice of words, they’re engaging in dialogue.

Why does dialogue matter in a story?

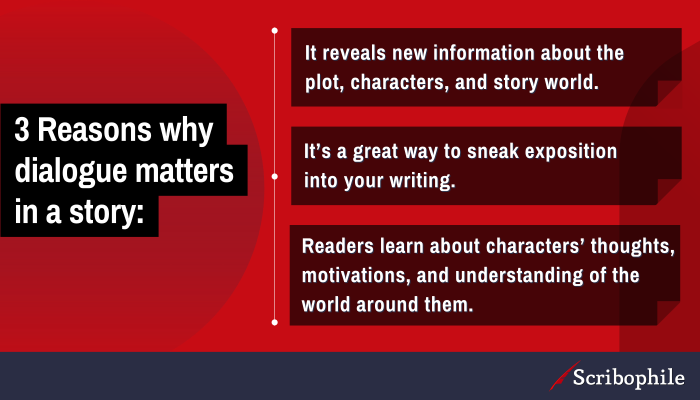

We use dialogue in a story to reveal new information about the plot, characters, and story world. Great dialogue is essential to character development and helps move the plot forward in a story.

Writing good dialogue is a great way to sneak exposition into your story without stating it overtly to the reader; you can also use tools like dialect and diction in your dialogue to communicate more detail about your characters.

Through a character’s dialogue, we can learn about their motivations, relationships, and understanding of the world around them.

A character won’t always say what they mean (more on dialogue subtext below), but everything they say will serve some larger purpose in the story. If your dialogue is well-written, the reader will absorb this information without even realizing it. If your dialogue is clunky, however, it will stand out and pull your reader away from your story.

Rules for writing dialogue

Before we get into how to make your dialogue realistic and engaging, let’s make sure you’ve got the basics down: how to properly format dialogue in a story. We’ll look at how to punctuate dialogue, how to write dialogue correctly when using a question mark or exclamation point, and some helpful dialogue writing examples.

Here are the need-to-know rules for formatting dialogue in writing.

Enclose lines of dialogue in double quotation marks