- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Quick Facts

- Plant and animal life

- Ethnic groups

- Settlement patterns

- Demographic trends

- Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

- Resources and power

- Manufacturing

- Labour and taxation

- Transportation and telecommunications

- Constitutional framework

- Local government

- Political process

- Health and welfare

- Cultural milieu

- Daily life and social customs

- Cultural institutions

- Sports and recreation

- Media and publishing

- Pre-Spanish history

- The Spanish period

- The 19th century

- The Philippine Revolution

- The period of U.S. influence

- World War II

- The early republic

Martial law

The downfall of marcos and return of democratic government.

- The Philippines since c. 1990

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Jewish Virtual Library - Philippines

- Official Site of the Department of Tourism , Philippines

- Central Intelligence Agency - The World Factbook - Philippines

- Philippines - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Philippines - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

In September 1972 Marcos declared martial law , claiming that it was the last defense against the rising disorder caused by increasingly violent student demonstrations, the alleged threats of communist insurgency by the new Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), and the Muslim separatist movement of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF). One of his first actions was to arrest opposition politicians in Congress and the Constitutional Convention . Initial public reaction to martial law was mostly favourable except in Muslim areas of the south, where a separatist rebellion, led by the MNLF, broke out in 1973. Despite halfhearted attempts to negotiate a cease-fire, the rebellion continued to claim thousands of military and civilian casualties. Communist insurgency expanded with the creation of the National Democratic Front (NDF), an organization embracing the CPP and other communist groups.

Under martial law the regime was able to reduce violent urban crime, collect unregistered firearms, and suppress communist insurgency in some areas. At the same time, a series of important new concessions were given to foreign investors, including a prohibition on strikes by organized labour , and a land-reform program was launched. In January 1973 Marcos proclaimed the ratification of a new constitution based on the parliamentary system , with himself as both president and prime minister . He did not, however, convene the interim legislature that was called for in that document.

News •

General disillusionment with martial law and with the consolidation of political and economic control by Marcos, his family, and close associates grew during the 1970s. Despite growth in the country’s gross national product , workers’ real income dropped, few farmers benefited from land reform , and the sugar industry was in confusion. The precipitous drop in sugar prices in the early 1980s coupled with lower prices and less demand for coconuts and coconut products—traditionally the most important export commodity—added to the country’s economic woes; the government was forced to borrow large sums from the international banking community . Also troubling to the regime, reports of widespread corruption began to surface with increasing frequency.

Elections for an interim National Assembly were finally held in 1978. The opposition—of which the primary group was led by the jailed former senator Benigno S. Aquino, Jr. —produced such a bold and popular campaign that the official results, which gave Marcos’s opposition virtually no seats, were widely believed to have been illegally altered. In 1980 Aquino was allowed to go into exile in the United States , and the following year, after announcing the suspension of martial law, Marcos won a virtually uncontested election for a new six-year term.

The assassination of Benigno Aquino as he returned to Manila in August 1983 was generally thought to have been the work of the military; it became the focal point of a renewed and more heavily supported opposition to Marcos’s rule. By late 1985 Marcos, under mounting pressure both inside and outside the Philippines, called a snap presidential election for February 1986. Corazon C. Aquino , Benigno’s widow, became the candidate of a coalition of opposition parties. Marcos was declared the official winner, but strong public outcry over the election results precipitated a revolt that by the end of the month had driven Marcos from power. Aquino then assumed the presidency.

Aquino’s great personal popularity and widespread international support were instrumental in establishing the new government. Shortly after taking office, she abolished the constitution of 1973 and began ruling by decree. A new constitution was drafted and was ratified in February 1987 in a general referendum; legislative elections in May 1987 and the convening of a new bicameral congress in July marked the return of the form of government that had been present before the imposition of martial law in 1972.

Euphoria over the ouster of Marcos proved to be short-lived, however. The new government had inherited an enormous external debt, a severely depleted economy, and a growing threat from Moro and communist insurgents. The Aquino administration also had to weather considerable internal dissension, repeated coup attempts, and such natural disasters as a major earthquake and the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo . The resumption of active partisan politics, moreover, was the beginning of the end of the coalition that had brought Aquino to power. Pro-Aquino candidates had won a sweeping victory in the 1987 legislative elections, but there was less support for her among those elected to provincial and local offices in early 1988. By the early 1990s the criticisms against her administration—i.e., charges of weak leadership, corruption, and human rights abuses—had begun to stick.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- What She Wants

- The Directory

- The Noble Man

- Food & Drink

- Arts & Entertainment

- Movies & TV

- Books & Art

- Motorcycles

- Notes & Essays

- What I've Learned

- Health & Fitness

- Sex & Relationships

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

NPC Seal of Registration

Esquire has been granted the NPC Seal of Registration in recognition of the successful registration of its DPO and DPS

Gregorio Brillantes' Brief History of Martial Law

IT WAS NOT SEPTEMBER 21, but September 22, 1972, that signaled the actual start of Ferdinand Marcos’ martial law regime. To be exact, 9:11 p.m. on that day 17 years ago— a Friday, as is the 22nd of this the first “Marcos Month” to be proclaimed by the admirers of the deposed despot. [1] The correct date of what Canor Yñiguez, Turing Tolentino, and Annie Ferrer [2] should commemorate as “Thanksgiving Day,” and the exact hour of the commencement of that infamy, are provided us by I.M. Escolastico, our friend and press brod of long standing (though he prefers to take things sitting down). And perhaps only in our fraternal estimate: pal Esky or Lasty or Ticong is one of the smartest, most perceptive and penetrating observers of the Pilipinas scene.

Ticong cites as his primary source or authority for the martial law data no less than the extraordinary author of Proclamation 1081 : Ferdinand Edralin (Ferdie, Andy, Apo, Tuta, Hitler) Marcos, who in 1980 or eight years after the event found the gall, cost, and ghost to write, in Notes on the New Society , now mercifully out of print, that “the instrument ‘Proclaiming a State of Martial Law in the Philippines’ had been signed on the 21st of September and transmitted to the Defense Authorities for implementation…clearance for which was given at 9:00 p.m., 22nd of September, after the ambush of Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile at 8:10 p.m. at Wack Wack Subdivision, Mandaluyong, Rizal.”

As for “implementation” being 11 minutes behind martial schedule—that, claims Ticong, ever the scrupulous student of history, was Enrile’s driver’s fault. The man, on learning that the defense chief was supposed to have been waylaid by Communist terrorists at Wack Wack, had called it a day and gone home to his second common-law wife, leaving Johnny driverless for crucial minutes on that fateful night. [3] As for the ambush, Enrile has since humbly confessed, under the tender gaze of Our Lady of Fatima at Edsa, that it was faked, to justify the desperate need—of his boss, as it turned out—for martial law.

As for the ambush, Enrile has since humbly confessed, under the tender gaze of Our Lady of Fatima at Edsa, that it was faked, to justify the desperate need—of his boss, as it turned out—for martial law.

So all that business about the Inglorious 21st had more to do with Apo Marcos’ superstitious obsession with numbers—dates divisible by seven were deemed most auspicious, until of course the 21st of August 1983—than with the facts of history, before which Esky can only bow down in reverent humility.

Anyway, that Friday night in September ‘72, Escolastico remembers sharing a convivial table at the Acapulco Bar of the Tower Hotel in Ermita with the Free Press’ Napoleon Rama, Pilipino Star’s Ruther Batuigas and the Economic Monitor’s Willie Baun, watching, together with two-thirds of Manila’s licentious press, an alleged fashion show of the latest-style lingerie. [4]

Nap Rama and some other connoisseurs of avant-garde fashion were nabbed on the way or when they got home in the pre-dawn darkness of September 23. To his surprise, dejection and eventual relief, Escolastico was spared the attentions lavished by the Metrocom on his subversive media colleagues. It seems his mother’s own cousin from Camiling, a rather short but high official close to Mr. Marcos, and a couple of Palace friends with no little influence at Camp Crame, had managed to have a few names, including his and that of a future National Artist then working on a biography of Ninoy Aquino, deleted from a colonel’s mission order. [5]

Whatever the real lowdown, which has never been confirmed or denied, the net result for Escolastico was an injustice, one of the most dastardly in that long dark night—denying him accommodations among the brave, the true and the honorable in the Crame gym, and depriving him of such manly ordeals, such inspiring tales of faith, valor and egoism as Max V. Soliven hadn’t tired of recycling 'til the day he died. [6]

Denied that transfiguring encounter with destiny, Escolastico now reveals that he sought redemption and peace of soul by writing down his impressions of the martial law years, for the benefit, as the former Malacañang tenant was wont to say, of “our country and people, of all Filipinos and their posterity.” By the time Apo Marcos and Imelda got settled in Makiki Heights, our friend had produced more than two thousand pages of jottings, enough for a hefty volume that can brain a thick-skulled FM loyalist if dropped from, say, the top of the Imeldific Cultural Center.

But is Escolastico’s chronicle of martial law, like Soc Rodrigo’s in this distinguished journal, worth the telling? [7] What can he possibly recount that hasn’t already been recorded in far more vivid detail and memorable style since the Marcoses took that flight to Hawaii?

Nap Rama and some other connoisseurs of avant-garde fashion were nabbed on the way or when they got home in the pre-dawn darkness of September 23.

People have a point there, he concedes; but not one to be so quickly squelched on the subject, he offers us this condensation of his massive work—a history of martial law, all in one paragraph:

“Contrary to oft-repeated allegations, it wasn’t honest-to-goodness one-man rule. Like any good dictator’s wife, Imelda helped ruin the country.” Johnny, Danding, Bobby, Hermie, Disini, Rudy, Jun, Laya, Ongpin, de Venecia, and other business-minded busy buddies pitched in, too. So did Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, George Bush, and Michael Armacost. [8] Not to be forgotten are the contributions to the erection of the New Republic from Kokoy, Bejo, Pacifico, Elizabeth, and other hard-working relatives. Marcos & Co. indeed had a lot to do—to our people and country, our history, government, economy, posterity, etc.

The 1973 Constitution, delayed by the abrupt disappearance of many Con-Con delegates, had to be finished, naturally in 1973. A group of diligent delegates, led by somebody who looked like Diosdado Macapagal, worked overtime in the Malacañang library, often forgoing dinner and floor show, to complete the Charter. The self-appointed constitutional authoritarian liked the results especially the provisions that would make him president for life. Marcos thought the Filipino people should, too. Multitudes expressed their approval by cheerfully raising their hands as they were photographed. The photo industry, along with other trades favored by the First Couple, was thus given a big boost.

The Muslims, who had been requested to surrender their guns, had to be placated, also with guns. [9] Generals added the mortuary business to their portfolio of lucrative sidelines. The Department of Public Information promoted developmental journalism. This led to some interesting developments in the media, anyway in the newspapers and publications that had replaced the Manila Times, Chronicle, Herald, Free Press, etc. Doroy Valencia developed Rizal Park and environs and was hailed as the Dean of Philippine Journalism. The cultural scene was enlivened by visiting artists like Van Cliburn, George Hamilton, Gina Lollobrigida, Rudolf Nureyev, Margot Fonteyn, George Frazier, and Muhammad Ali.

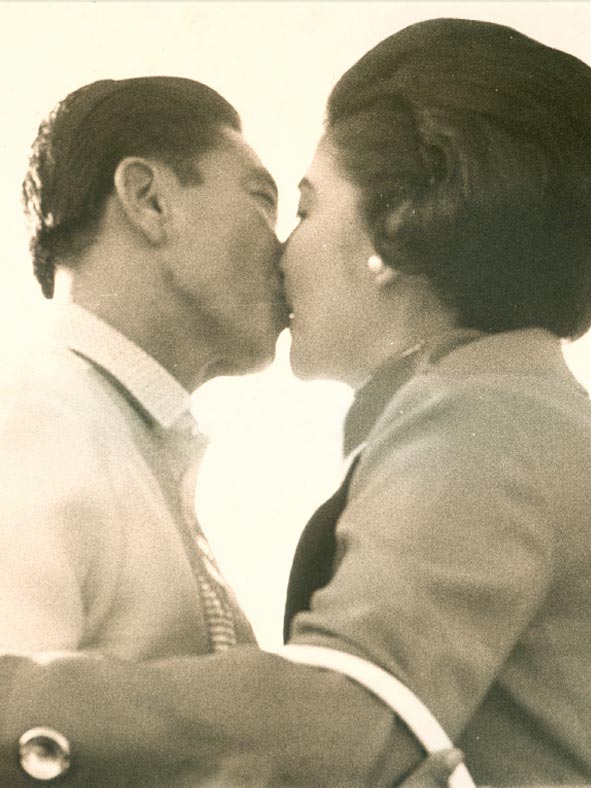

Marcos and Meldy didn’t neglect to bring Philippine-American relations to new heights or old depths, as the case may be—FM by entertaining Hollywood starlet Dovie Beams with bedside renditions of Ilocano love songs, and Imelda discoing all night long with the billionaire heiress Cristina Ford. Ninoy Aquino, the regime’s most famous detainee, and Soc Rodrigo, Tany Tañada, Tito Guingona, and other irrepressible souls ran for the Interim Batasan. They lost to Imelda, Cesar Virata, Vicente Paterno, and other beloved figures of the Kilusan Bagong Lipunan. The ensuing noise barrage failed to shatter Marcos’ eardrums or his equanimity.

Then, Francisco Tatad [10] resigned as information minister to campaign for the Opposition’s surprised presidential candidate, the heroic and semi-senile Alejo Santos. The old guy was trounced, too, but that didn’t seem to depress him or his pious campaign manager, who kept his job as media psychology consultant to the Office of the President. Marcos went on making speeches, something he had always liked to do since his UP days. [11]

What did martial law, Marcos, Imelda, Enrile, Danding, Ver, EDSA, and all that teach us Filipinos? What have we learned?” He answers his own momentous query: “Next to nothing.”

Florentino “Yen” Makabenta, not Adrian Cristobal, as was long wrongly assumed, wrote for Marcos something like 1,769 speeches, on subjects ranging from Absolutism to Zoning, without pronunciation guides. Consequently, Marcos kept saying ‘le-jeés-lah-tive,’ and ‘towárds’ and ‘Sar-tre,’ things like that, until aggravated Ateneans just had to launch the Light-a-Fire movement to stop the atrocities in conference halls, auditoriums, theaters, not to mention on radio-TV. Imelda also delivered her quota of speeches, with titles like "City of Man in the Kingdom of God" and "The Moral Dimensions and Aesthetic Parameters of the Green Revolution." On the side, with the audio-visual assistance of Dr. Jolly Benitez, she gave lectures on the "Synergy of the Good, the True and the Beautiful," and the "Bountiful Hole in the Sky."

The gap widened between the very rich and the very poor, with more and more of the latter tumbling into it or below the poverty line or along railway lines. The NPA featured Marcos’ portrait on its recruitment posters, with unprecedented results—9,743 more Joemao guerrillas roaming the countryside and chanting, “Down with the US-Marcos dictatorship, and expose and oppose US imperialism, domestic feudalism and bureaucratic capitalism!”

Amnesty International discovered that there were now many more human wrongs than rights. Metro Aides lent zest and color to often flooded streets and June 12 parades. Earlier, the Afro-Asian Writers Conference had for a special guest the famed punctuation poet, Jose Garcia Villa, [12] who, without really trying, almost caused the confab to lapse into a coma. Enrile and Danding put up a non-profit foundation for the coconut industry—to collect and invest the coco levy, research on stem borers, worms and other pests, and boost export production and the gross income of coconut planters playing the stock market. [13]

All this time, Marcos and his spouse were amassing a fabulous fortune by venturing into hidden wealth areas. This single-minded interest in matters financial would have some negative effects on the Philippine economy and the international banking system. Justice Secretary Ricardo Puno improved the syntax of the laws on detention. Chief Justice Ikeng Fernando penned his landmark annotations to the jurisprudence on Imelda’s official umbrella. On the third or fourth anniversary of the declaration of you-know-what, the Supreme Court Justices in special session rose as one chorus to sing the Hymn to Constitutional Authoritarianism that sounded more than a bit like Handel‘s Hallelujah . [14] Imelda borrowed at least five 747 jumbo jets from PAL (for her junkets round the world) and several millions from the GSIS (for building heart and lung centers and buying shoe stores), all without collateral and just by phoning Roman Cruz, Jr. which all involved some use of farce, as the First Lady had by then seized the airline from Benny Toda, and Marcos of course owned GSIS, SSS, PNB, and all the rest.

Around this time, Marcos decided to lift martial law, transferring the decree to a higher drawer in his Malacañang study, and throwing in some fresh mothballs to boot. This was before Ninoy Aquino came back from exile, [15] despite General Fabian Ver’s solicitous warning that some people would shoot him in the head if he wore a bulletproof vest. This was exactly what happened, at the airport, as Ninoy was gingerly helped down the passenger tube stairs. He was shot dead, in the head from behind and above, although his shorter assassin was seen standing on the tarmac several feet away in front of the tube stairs. [16]

The gap widened between the very rich and the very poor, with more and more of the latter tumbling into it or below the poverty line or along railway lines.

This led to a lot of confusion and bad feelings and angry demos throughout the land. Storms of yellow confetti donated by Bea Zobel and Ting-Ting Cojuangco blocked traffic on Ayala Avenue, while Butz Aquino and Nikki Coseteng alternately marched, skipped, and jogged from Tarlac to Tarmac. Then Marcos snapped at the chance of winning his sixth or seventh mandate from the people. But faced with the popular and saintly Cory, he found his macho appeal failing him, followed by his kidneys, or vice versa. He tried to do a repeat of his ‘69 election victory complete with guns, goons, gold, silver, and stuffed ballot boxes. That was when, as they say, ‘the shit hit the fan,’ which is more graphic, rhythmic and onomatopoeic in Ilocano. [17]

Finally, God, Enrile, Ramos, RAM, and Cardinal Sin brought about the EDSA Revolt, which gave the gringos the chance to repay Marcos for being their right arm or hand or whatever appendage in Asia. In a semi-comatose state the toppled constitutional authoritarian, together with his wife and kids Imee, Bongbong, and Irene, [18] was flown out by the U.S. State Department or the CIA or the Green Berets to involuntary exile, and retirement in Hono-lulu, [19] with Imelda on the plane singing ‘Killing Me Softly’ and ‘New York, New York,’ looking and sounding like Tessie Tomas, only “heavier, mournful and melodramatic.”

“Now,” says Escolastico as he looks us reprimandingly in the eye, “what did martial law, Marcos, Imelda, Enrile, Danding, Ver, EDSA and all that teach us Filipinos? What have we learned?” He answers his own momentous query: “Next to nothing.” [20]

1 “17 years ago” in 1989 when this historical paper was first written. About FM’s fans, as of 5 p.m., Aug. 22, 2012: there were 3, 147,568 card-carrying Marcos loyalists (as distinct from auxiliaries), roughly 57% from Ilocos Norte and/or Leyte, three from the Senate, 17 in the Lower House. (Ref. Marcos Forever Directory, KLB Club, Barangay Kalentong, Mandaluyong, MetroManila.)

2 Rep. Yñiguez and Sen. Tolentino have since gone to their reward. Actress Annie was last seen in Rizal Park chasing after or being chased by the riot police in ‘89 or ‘90. If located, Esquire might consider a photoshoot.

3 The driver, Joker or Jocar Nalundasan, was fired the next day and reportedly went back to Sarrat or Batac or Tuguegarao and turned NPA or OFW before or after EDSA.

4 Star of the show was Ruffa’s mom, Anabelle Rama. As Nap Rama, Bulletin publisher after EDSA, was heard to say: Time really fugits, bai!

5 Now it can be told: that highly influential official was the great CPR, this magazine’s editor-in-chief’s grand-uncle; the Palace friends were FM’s Special Assistant Juan Tuvera and wife, writer Kerima Polotan—all three from the loyal and ever noble province of Tarlac. That “future National Artist” was Nick Joaquin, whom the author had succeeded as editor-in-chief of Asia-Philippines Leader.

6 Max co-founded The Philippine Star with Betty Belmonte. That middle initial V., he used to say, didn’t mean Ver but valiant, vigilant, venturesome—and sometimes vociferous, verbose and voluminous, haha. A genuine, great Ilocano.

7 The Times-Journal was owned by Kokoy Romuladez, bless him—he never censored Soc or Escolastico. There was press freedom in that nook and cranny of Port Area—ask Jullie Yap Daza.

8 Macoy would never have declared martial law without U.S. O.K., thanks to special relations, Clark, Subic, etc.—until EDSA. As for those cronies, there’s Ricardo Manapat’s must-read Some Are Smarter Than Others (which in retrospect was putting it mildly).

9 One offshoot of the Mindanao MNLF wars—Imelda became roving Ambassador of the New Society. She and select Blue Ladies flew to Libya for peace talks with Nur Misuari’s mentor Muamar Khadaffi—and then on to Rome, Paris, London, Moscow, Beijing, Tokyo, San Francisco, New York, Cancun, Rio de Janeiro.

10 Yeah, the same Opus Dei minister who sparked People Power II by sitting on that sealed envelope which contained Erap’s laundry or jueteng list. Not to be confused, as happened once too often at news desks, with the celebrated Iglesia ni Cristo rapper and heavy metal sculp-tor, Kitch or Itlog Taccad.

11 FM had always had a special relationship with his alma mater—and the UP studentry. The First Quarter Storm that so discombobulated him was mostly a UP production, as was the Diliman launch of The Apo’s cassette tape, “Pamulinawen Lovie Dovie.”

12 Doveglion was one of Ma’am Meldy’s National Artists—for Pwetry. At a Malacañang state dinner, JGV shucked off his slacks to show his butt to Russian poet Yevtushenko and company, whereupon the First Lady had Villa hustled out by the Presidential Guard, never to be seen again.

13 They are still at it—or rather the stock-playing coco farmers—though the research on stem borers, worms and other coconut industry pests continues to this day, thanks to the agribusiness foundation founded by JP Enrile and E. Cojuangco.

14 No truth to the rumor that one Renato Corona was seen singing along—this Supreme Court choral performance was in 1979 and the recently impeached Chief Justice was then still in the Ateneo Grade School and hadn’t met Marcos, let alone Gloria, nor any dollar trader.

15 This was in August 1983—some months after Ninoy’s court martial and death sentence—and Imelda’s permission for him to leave for the U.S., to see his heart doctor in Boston.

16 Correction: Rolando Galman was never seen standing on the tarmac—he was pushed out stiff and dead from the Aviation Security Van as Ninoy was shot, from behind going down on the tube stairs. The mastermind or at least two of the conspirators are still alive and at large.

17 Nagparsiak ititakki nga impurwak didiay bentilador —translation courtesy of Sonny “Saluyot” Bangloy, VP for entertainment of the Laoag Press Club.

18 Imelda has since served as Leyte representative, and is now governor of Ilocos Norte. Imee too has been to Congress. And Senator Ferdinand Marcos Jr. is even now gearing for a run to Malacañang a few years hence. And those loyalists in Congress and out are clamoring louder than ever for their refrigerated idol in Batac to be enshrined in the Libingan ng Mga Bayani. So what else is new?

19 To be exact, in Makiki Heights—in the residence of Bienvenido Tantoco. The Marcoses stayed in Tantoco’s villa till the dictator’s demise from lupus and extraconstitutional complications in September 1989, age 72.

20 Next to zero or what? Ask Cory, or rather her KAMAGANAK, Inc. and the tenants of Hacienda Luisita. Ask Fidel Ramos and top officials and generals and old Cha-Cha troupe. Ask Joseph Erap Estrada, the popular plunderer and convicted charmer. Ask Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo…Ask P-Noy—Benigno Simeon Aquino III...They just might all agree.

Gregorio C. Brillantes’ “A Brief History of Martial Law” first appeared in the Times-Journal in 1989, and was later collected in his non-fiction collection The Cardinal’s Sins, the General’s Cross, the Martyr’s Testimony and Other Affirmations (Ateneo de Manila Press, 2005). It was then published in the September 2012 issue of Esquire Philippines .

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on Esquiremag.ph. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. Find out more here .

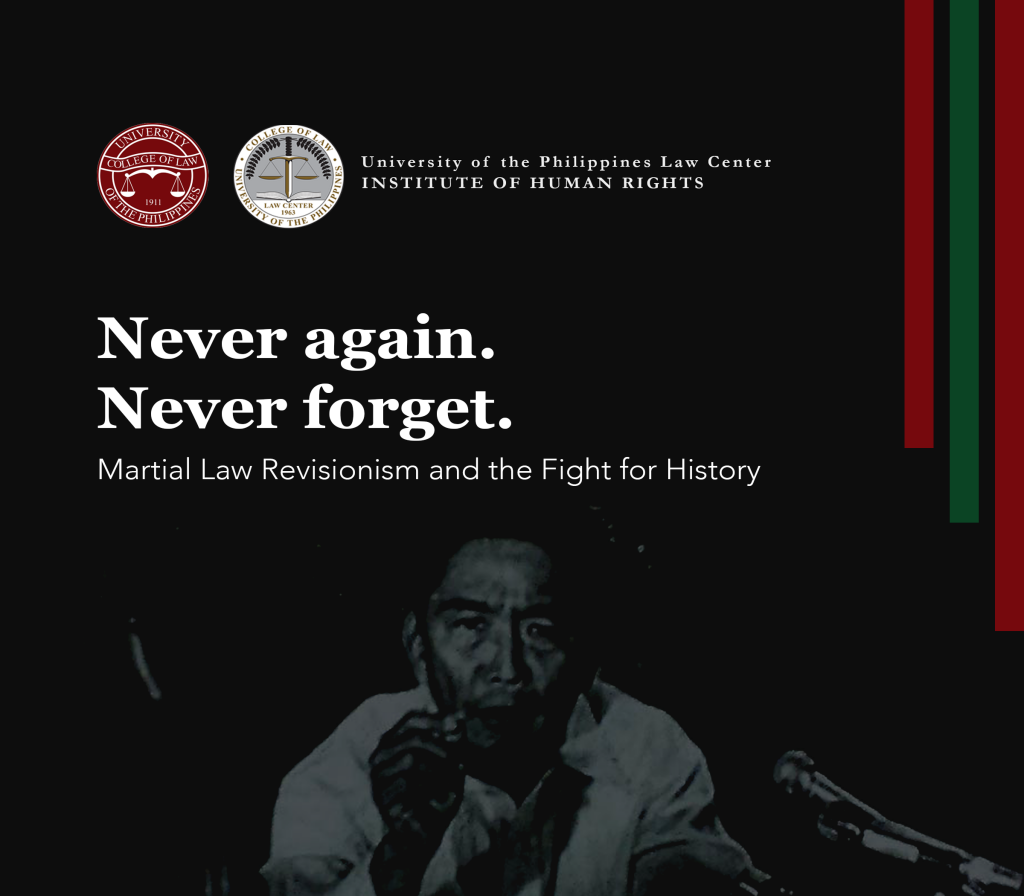

Martial Law Revisionism and the Fight for History

Never again. never forget. martial law revisionism and the fight for history.

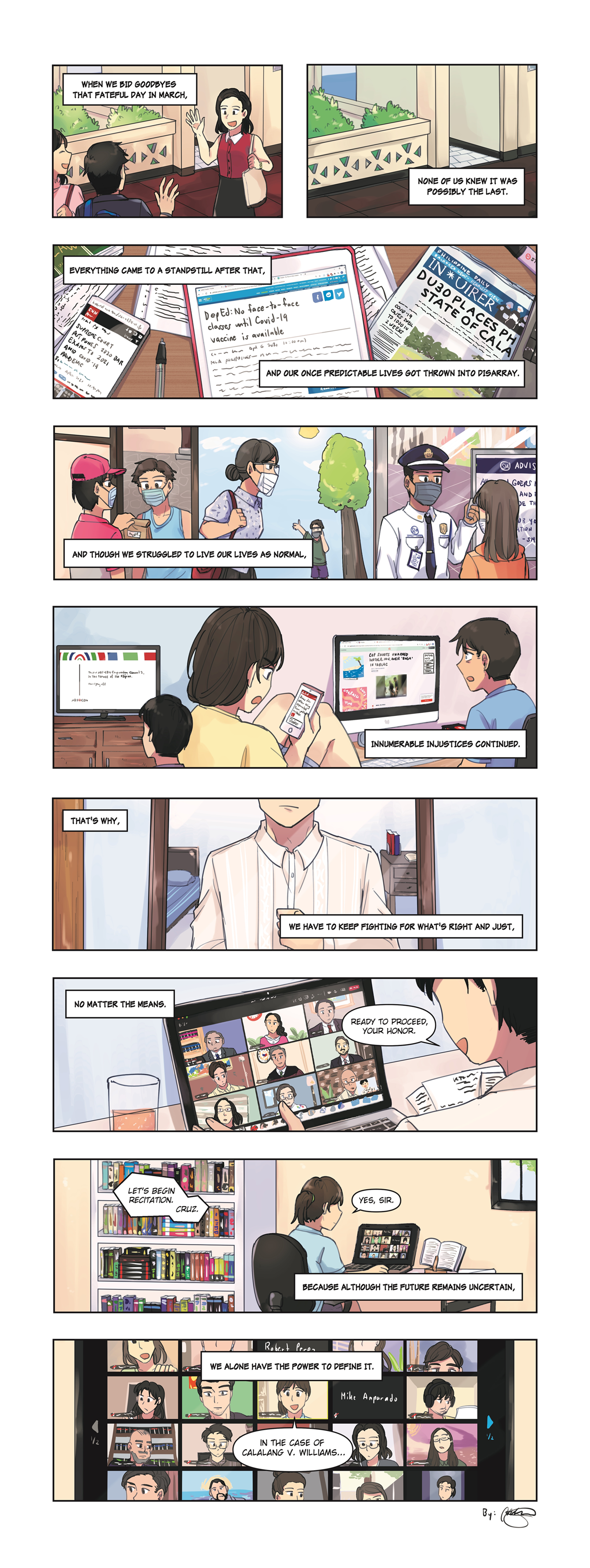

UP IHR releases photo album of human rights atrocities during martial law.

Remembering the 48th anniversary of the declaration of Martial Law in the country by the Dictator Ferdinand Marcos, the UP Institute of Human Rights published on 21 September 2020 a photo album showing the various human rights atrocities committed during the period. With the theme, “Martial Law Revisionism and the Fight for History,” the album displayed photos and stories from the Human Rights Victims’ Memorial Claims Board, Bantayog ng mga Bayani, and the Martial Law Chronicles Project.

Click here to download the IHR’s Martial Law Album

- Post category: News

- Post published: September 22, 2020

- Post last modified: November 13, 2020

Atty. Fina dela Cuesta-Tantuico

- Assistant to the Dean for Alumni Affairs

- Senior Lecturer, UP College of Law

- Professorial Lecturer, Lyceum of the Philippines College of Law

- Fellow, 1st UP Creative Writers’ Workshop (1980)

- Instructor I, UP Department of English and Comparative Literature (1982)

- Trustee and Corporate Secretary, UP Law Alumni Foundation Inc.; Justice George Malcolm Foundation Inc.

- Past President, UP Women Lawyers’ Circle

- Past President, Philippine Bar Association

- UP College of Arts and Sciences, A.B. English, cum laude (1982)

- UP Law Class 1988

Atty. Rizalde Laudencia

- Member, Sangguniang Panlungsod, San Fernando, La Union

- Studied at Confucius Institute, Ateneo de Manila University

- Does Chinese Painting ( Lingnan Style)

- Writes poems in English, Tagalog, and Ilocano

- UP A.B. Political Science (1978)

- UP Law Class 1982

Dr. Rolando Tolentino

- Professor, UP Film Institute

- Director, UP Institute of Creative Writing

- Former Dean, UP College of Mass Communication

- Member, Manunuri ng Pelikulang Pilipino and the Film Development Council of the Philippines

- Awardee: UP Press Centennial Publication Award; National Book Award, Obermann Summer Research Fellowship; Manila Critics Circle Award; Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards for Literature

- A.B. Economics, De La Salle University

- M.A. in Philippine Studies, De La Salle University

- Ph. D. in Film, Literature and Culture, University of Southern California

Atty. Nicolas Pichay

- Director, Legislative Research Service, Senate of the Philippines

- Poet, playwright, essayist

- Hubert Humphrey Fellow, Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University 2018

- Awardee: Carlos Palanca Literary Prize (2007 Hall of Fame); NCCA Literary Awards; CCP Literary Awards; Asian Cultural Council; and Gawad Pambansang Alagad ni Balagtas of UMPIL (2016)

- UP A.B. Political Science (1984)

Atty. Alden Lauzon

- Assistant Professor 7, Department of Art Studies, UP College of Arts and Letters (CAL)

- Associate Dean for Administration, CAL (June 2015 – June 2021)

- Senior Partner, Pedregosalaw Offices

- UP M.A. Art Studies, Art History (1998)

- UP Law Class 2000

Dr. Jose Dalisay Jr.

- Professor Emeritus , English and Creative Writing, UP

- Fellow and Former Director, UP Institute of Creative Writing

- Author, writer

- Awardee: 16 Carlos Palanca Awards in 5 genres

- UP College of Arts and Sciences, A.B. English, cum laude (1984)

Jayvee Arbonida del Rosario (Student)

Fever dream (I want to stay)

What is to wake? As days blur by and memory fails, so too does the line between dream and reality fade. One is as ephemeral as the other. Perhaps, it is in this realm of warped time and lost futures, of muted joys and terrors, where things make more sense.

Marissa Lucido Iñigo (Admin Staff)

Pagsulong sa kabila ng pagsubok

Bagamat matagal at paulit-ulit na tayong naghihigpit at lumuluwag sa mga kwarantin na ipinapatupad sa ating bansa, iisa lang ang nababakas sa mga buhay ng mga Pilipino araw-araw, pagsulong at pagtataguyod sa pamilya sa kabila ng pagsubok na sinasagupa araw-araw.

Nababata ng mga manggagawa ang lahat para sa kanilang mga pamilya. Nadagdag isuot araw-araw ang proteksyon laban sa nakakahawang sakit, pero talaga nga bang napoproteksyunan tayo sa totoong sakit sa bansa?

“Ano nga ba ang tunay na pagsubok? Ang Pandemya o ang sistema?” – Tanong ng Pilipinong lumalaban.

Gianina O. Cabanilla (REPS)

Stay with me till the sun sets and we rise together

The fury, the fire, the glory of endings and beginnings, the bone melting pain of it all

Life goes on… and we will not stop pushing for a better tomorrow. Not now, not ever.

Note: This e-book is intended for online viewing only. It is not intended as an actual publication. Click on the thumbnail to view the winning entries.

(To view all entries , click here )

Recommended internet cookies are used by this website to improve your browsing experience. These cookies include Google Analytics, Facebook, Instagram, WordPress and Zendesk products or widgets. Your consent is important to us.

- Israel-Gaza War

- War in Ukraine

- US & Canada

- UK Politics

- N. Ireland Politics

- Scotland Politics

- Wales Politics

- Latin America

- Middle East

- In Pictures

- BBC InDepth

- US Election

- Election polls

- Kamala Harris

- Donald Trump

- Executive Lounge

- Technology of Business

- Women at the Helm

- Future of Business

- Science & Health

- Artificial Intelligence

- AI v the Mind

- Film & TV

- Art & Design

- Entertainment News

- Arts in Motion

- Destinations

- Australia and Pacific

- Caribbean & Bermuda

- Central America

- North America

- South America

- World’s Table

- Culture & Experiences

- The SpeciaList

- Natural Wonders

- Weather & Science

- Climate Solutions

- Sustainable Business

- Green Living

Philippines martial law: The fight to remember a decade of arrests and torture

Santiago Matela was 22 when he was dragged off the street by soldiers while playing basketball.

The year was 1977, five years since President Ferdinand E Marcos had declared martial law in the Philippines - on 21 September 1972.

Mr Marcos suspended parliament and arrested opposition leaders - Mr Matela was among the tens of thousands of people detained and tortured during a decade of martial law.

Fifty years on, he is no longer afraid to speak out. But he is afraid of not being believed at a time when the truth about one of the darkest periods in Filipino history is under attack.

Mr Matela endured three months of torture, including being tied naked to a block of ice. His captors demanded he admit to being a communist. He says he didn't even know what that word meant.

"They kept on forcing me to confess that I was leading a rally and throwing grenades. They asked me the same questions again and again and beat me. They used a yantok - a cane - and they hit my body many times," he said.

"Even my genitals were assaulted by the military just to make you confess what you should not be confessing."

Some 70,000 people were imprisoned, 34,000 were tortured and over 3,200 people were killed in the nine years after Mr Marcos imposed martial law, according to Amnesty International.

Meanwhile, the Marcos family lived famously opulent lifestyles. Mr Marcos' wife, Imelda Marcos, amassed a huge collection of art and other luxuries, including hundreds of pairs of shoes.

They deny siphoning off billions of dollars of state wealth while at the helm of what historians consider one of Asia's most notorious kleptocracies.

Public anger at abuse and corruption eventually led to pro-democracy protests in 1986 and the family were forced to flee to Hawaii where they lived in exile. Ferdinand Marcos died three years later.

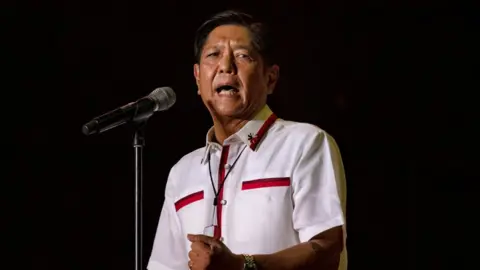

But earlier this year, his son and namesake, Ferdinand Marcos Jr - popularly known as "Bongbong" - led an extraordinary comeback and won the presidency in a landslide victory.

What a Marcos revival means for the Philippines

Why the marcos family is so infamous.

- 'Politicians hire me to spread fake stories'

The Marcos rebranding is the result of a major social media operation, aimed at younger Filipinos born after martial law ended. The message seeded in snappy Facebook, YouTube and TikTok posts is that the family has been unfairly treated by the mainstream press.

Mr Marcos Jr has shunned network news interviews and refused to participate in presidential debates. He has made it clear he doesn't want to discuss the past and has instead focused on a promise to unite the nation and help it recover from the crippling effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

This popular message, by a recognisable celebrity name, hit home with voters eager for change - including Mr Matela's children.

Mr Matela tells me that his son believes the past should stay in the past, a view that he finds upsetting.

"My son is adamantly on their side. He doesn't know that what I'm doing is all for them. These are my experiences and what I'm fighting for is for their sake too, so that they will know what happened.

"You want me to just disregard what I went through? That cannot happen. The sufferings I went through are embedded in my mind," he said.

"I'm still fighting because of my pain."

Disinformation and denial

The Marcos administration insists it has not engaged in disinformation.

Gemma, a fact checker from the news website Rappler founded by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Maria Ressa, says the disinformation being propagated is difficult to quantify.

"It's not one single page, it's not one single account, it's not one single group. The point is that it's coming at you from various points. We've mapped tens of thousands of accounts and groups and pages.

"Many look like official history pages and post content that triggers nostalgia but within that content you will find stories peddling an incorrect narrative."

Among the most widely spread falsehoods are claims that no arrests were made under martial law.

"Many of the posts deny human rights abuses took place and claim that the only people incarcerated were rebels or criminals or troublemakers," Gemma said.

The Marcos administration has not responded to the BBC's requests for an interview.

Mr Marcos Jr has posted an interview on YouTube with his goddaughter where he denies that his father was a dictator.

The Marcos family has never apologised, but more than 11,000 victims, including Mr Matela, have received reparations from the government.

Their written accounts are logged in dozens of numbered cardboard boxes piled high in an archive at the Human Rights Violations Victims' Memorial Commission, an independent government body.

In a new green room at the centre, a young team are creating their own snappy social media posts - with facts about martial law.

"You have to go where the young people are," says executive director Crisanto Carmelo.

Fears the past is being rewritten have led to a push to preserve and digitise the detailed accounts of martial law abuse in the hope that they can be placed in a museum. One file recalls how a mother was handed back the body of her brutally tortured and murdered son. The account is too gruesome to detail here.

But will Mr Marcos allow such a museum - one built to honour the victims of martial law - while he is president?

"I am optimistic that he will be magnanimous in victory and serious in his intention to unify the country," Mr Carmelo said.

"This is the year which marks the 50th year of the declaration of martial law which transformed our country and transformed the lives of many ordinary Filipinos. Many of them are now in their senior years, like me, so a museum is not for me, I lived through it.

"A museum is for the younger generation - to say that this happened to our country and if we can come together, they can determine what type of country and system of government and rules of liberty and democracy they want for the future."

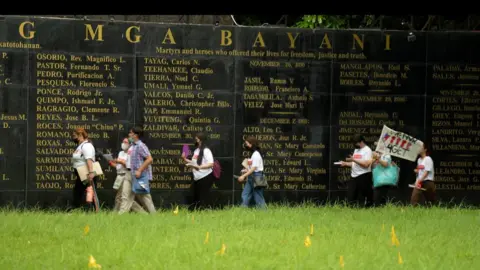

Many young Filipinos are engaged. On a recent popular historical tour, young Filipinos played games to recreate the past.

The idea is to help them pin down the facts and navigate away from a maze of martial law myths.

The teams took selfies together - most of them had met only a few hours earlier. They planted flowers at the memorial with the names of those who died under martial law.

Seventeen-year-old Hannah found the day emotional.

"They've lost their dreams, their lives and I wanted to recognise that. I want to go and tell my friends that in order for us to have the liberty and democracy we have today, these were people who sacrificed everything. They suffered a lot of violence and immoral wrongdoings, and they deserve to be recognised."

It seems that voices from the past, however painful, are helping to keep this country's collective memory alive.

Bongbong Marcos: Judge me on actions not ancestors

Philippine e-Legal Forum

Philippine laws and legal system (pnl-law blog).

Declaration of Martial Law under the Philippine Constitution: Exercise and Review

The constitutional provisions on Martial Law — as contained in Section 18, Article VII of the Constitution — is intended to provide additional safeguard against possible abuse by the President in the exercise of his power to declare martial law or suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus. Section 18 contains six paragraphs, and reads in full:

SECTION 18. The President shall be the Commander-in-Chief of all armed forces of the Philippines and whenever it becomes necessary, he may call out such armed forces to prevent or suppress lawless violence, invasion or rebellion. In case of invasion or rebellion, when the public safety requires it, he may, for a period not exceeding sixty days, suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus or place the Philippines or any part thereof under martial law. Within forty-eight hours from the proclamation of martial law or the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, the President shall submit a report in person or in writing to the Congress. The Congress, voting jointly, by a vote of at least a majority of all its Members in regular or special session, may revoke such proclamation or suspension, which revocation shall not be set aside by the President. Upon the initiative of the President, the Congress may, in the same manner, extend such proclamation or suspension for a period to be determined by the Congress, if the invasion or rebellion shall persist and public safety requires it. The Congress, if not in session, shall, within twenty-four hours following such proclamation or suspension, convene in accordance with its rules without any need of a call. The Supreme Court may review, in an appropriate proceeding filed by any citizen, the sufficiency of the factual basis of the proclamation of martial law or the suspension of the privilege of the writ or the extension thereof, and must promulgate its decision thereon within thirty days from its filing. A state of martial law does not suspend the operation of the Constitution, nor supplant the functioning of the civil courts or legislative assemblies, nor authorize the conferment of jurisdiction on military courts and agencies over civilians where civil courts are able to function, nor automatically suspend the privilege of the writ. The suspension of the privilege of the writ shall apply only to persons judicially charged for rebellion or offenses inherent in or directly connected with the invasion. During the suspension of the privilege of the writ, any person thus arrested or detained shall be judicially charged within three days, otherwise he shall be released.

I. FIRST PARAGRAPH: GRADUATED POWERS

The President is granted a “sequence of graduated powers” under Section 1 of Rule VII . From the most to the least benign, these are:

- 3. the calling out power

- 2. the power to suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus

- 1. the power to declare martial law

The graduation refers only to hierarchy based on scope and effect. It does not in any manner refer to a sequence, arrangement, or order which the Commander-in-Chief must follow. This so-called “graduation of powers” does not dictate or restrict the manner by which the President decides which power to choose.

Calling out the armed forces

Among the three extraordinary powers, the calling out power is the most benign and involves ordinary police action. The President may resort to this extraordinary power whenever it becomes necessary to prevent or suppress lawless violence, invasion, or rebellion.

The power to call is fully discretionary to the President; the only limitations being that he acts within permissible constitutional boundaries or in a manner not constituting grave abuse of discretion. In fact, the actual use to which the President puts the armed forces is not subject to judicial review.”

Suspending the writ; Declaring Martial Law

The extraordinary powers of suspending the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus and/or declaring martial law may be exercised only when there is actual invasion or rebellion, and public safety requires it. The 1987 Constitution imposed the following limits in the exercise of these powers:

- (1) a time limit of sixty days;

- (2) review and possible revocation by Congress; and

- (3) review and possible nullification by the Supreme Court

The framers of the 1987 Constitution eliminated insurrection, and the phrase “imminent danger thereof’ as grounds for the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus or declaration of martial law. They perceived the phrase “imminent danger” to be “fraught with possibilities of abuse;” besides, the calling out power of the President “is sufficient for handling imminent danger.”

The powers to declare martial law and to suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus involve curtailment and suppression of civil rights and individual freedom. Thus, the declaration of martial law serves as a warning to citizens that the Executive Department has called upon the military to assist in the maintenance of law and order, and while the emergency remains, the citizens must, under pain of arrest and punishment, not act in a manner that will render it more difficult to restore order and enforce the law.

The guarantees under the Bill of Rights remain in place during its pendency. And in such instance where the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus is also suspended, such suspension applies only to those judicially charged with rebellion or offenses connected with invasion.

Martial Law

A state of martial law is peculiar because the President, at such a time, exercises police power, which is normally a function of the Legislature. In particular, the President exercises police power, with the military’s assistance, to ensure public safety and in place of government agencies which for the time being are unable to cope with the condition in a locality, which remains under the control of the State.

Under a valid declaration of martial law, the President as Commander-in-Chief may order the: (a) arrests and seizures without judicial warrants; (b) ban on public assemblies; (c) [takeover] of news media and agencies and press censorship; and (d) issuance of Presidential Decrees. The President, however, does not have the unbridled discretion to infringe on the rights of civilians during martial law. This is because martial law does not suspend the operation of the Constitution, neither does it supplant the operation of civil courts or legislative assemblies.

Time is paramount in situations necessitating the proclamation of martial law or suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus. It was precisely this time element that prompted the Constitutional Commission to eliminate the requirement of concurrence of the Congress in the initial imposition by the President of martial law or suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus.

There is a necessity and urgency for the President to act quickly to protect the country. The Supreme Court , as Congress does, must thus accord the President the same leeway by not wading into the realm that is reserved exclusively by the Constitution to the Executive Departmen t.

II. SECOND PARAGRAPH: CONGRESSIONAL VS. JUDICIAL REVIEW

The other two branches of government — Congress and Judiciary — have the authority to review a declaration of martial law by the Executive . These review powers are independent from each other.

The power of review by Congress is provided in the second paragraph of Section 18, which reads: “The Congress, if not in session, shall, within twenty-four hours following such proclamation or suspension, convene in accordance with its rules without any need of a call.”

Congress ‘ review mechanism is automatic in the sense that it may be activated by Congress itself at any time after the proclamation or suspension was made. contrast, the Supreme Court’s review power is passive; it is only initiated by the filing of a petition by a citizen.

Congress may revoke the proclamation or suspension, which revocation shall not be set aside by the President. On the other hand, the Supreme Court may strike down the presidential proclamation in an appropriate proceeding filed by any citizen on the ground of lack of sufficient factual basis.

Congress could probe deeper and further; it can delve into the accuracy of the facts presented before it. The Supreme Court does not look into the absolute correctness of the factual basis.

Congress may take into consideration not only data available prior to, but likewise events supervening the declaration. The Supreme Court considers only the information and data available to the President prior to or at the time of the declaration; it is not allowed td “undertake an independent investigation beyond the pleadings.”

III. THIRD PARAGRAPH: JUDICIAL REVIEW

The third paragraph of Section 18 reads: “The Supreme Court may review, in an appropriate proceeding filed by any citizen, the sufficiency of the factual basis of the proclamation of martial law or the suspension of the privilege of the writ or the extension thereof, and must promulgate its decision thereon within thirty days from its filing.”

There is no similar provision in the previous constitutions. In 1951, the Supreme Court ruled that the President’s decision to declare a state of rebellion and suspend the writ of habeas corpus is final and conclusive upon the courts.

The Supreme Court, in 1971, declared that it has the power to review the existence of factual basis of the declaration of martial law and the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus . In other words, it is not covered by the “political question” doctrine.

In 1983, years after the declaration of Martial Law in 1972, the Supreme Court reverted to the 1951 ruling. The constitutional power of the President to suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus , according to the Supreme Court, is a political questions and NOT subject to judicial inquiry.

Thus, by inserting Section 18 in Article VII which allows judicial review of the declaration of martial law and suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, the framers of the 1987 Constitution in effect constitutionalized and reverted to the Lansang doctrine.

The framers of the 1987 Constitution inserted the third paragraph of Section 18, Article VII to reinstate the 1971 ruling and prevent any reinterpretation. As the Constitution stands today, the factual basis of the declaration of martial law or the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus is not a political question but within the ambit of judicial review.

Section 18 also relaxed the rule on standing by allowing any citizen to question before this Court the sufficiency of the factual basis of such proclamation or suspension. Section 18, Article VII conferred upon any citizen a demandable right to challenge the sufficiency of the factual basis of said proclamation or suspension.

The “sufficiency of factual basis test”

The Supreme Court’s power to review is limited to the determination of whether the President in declaring martial law and suspending the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus had sufficient factual basis. The review would be limited to an examination on whether the President acted within the bounds set by the Constitution, i.e., whether the facts in his possession prior to and at the time of the declaration or suspension are sufficient for him to declare martial law or suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus.

The parameters for determining the sufficiency of the factual basis for the declaration of martial law and/or the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, based on Section 18 fo Article VII , as as follows:

- (1) actual invasion or rebellion,

- (2) public safety requires the exercise of such power, and

- 3) there is probable cause for the President to believe that there is actual rebellion or invasion.

All three elements must be present; otherwise, the President’s declaration of martial law and/or suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus must be struck down.

[Source: Digest/summary of Lagman vs. Medialdea , G.R. No. 231658, 4 July 2017]

- Recent Posts

- Extension of Filing Periods and Suspension of Hearings for March 29 to April 4, 2021: SC Administrative Circular No. 14-2021 (Full Text) - March 28, 2021

- ECQ Bubble for NCR, Bulacan, Cavite, Laguna and Rizal: Resolution No. 106-A (Full Text) - March 27, 2021

- Guidelines on the Administration of COVID-19 Vaccines in the Workplaces (Labor Advisory No. 3) - March 12, 2021

- Primer on Separation of Powers, Inquiry in Aid of Legislation

- State of the Nation Address (SONA) 2009

- Bangsamoro Basic Law: House Bill No. 4994 (full text)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

AttyAtWork * VisitPinas * ChatTimeWithJulia RSS Entries and RSS Comments

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Martial law—or a state where a particular area (or the whole country) is under the control of the military or armed forces—is most often associated with former President Ferdinand Marcos. But not many people know the late strongman was not the first to declare it.

In September 1972 Marcos declared martial law, claiming that it was the last defense against the rising disorder caused by increasingly violent student demonstrations, the alleged threats of communist insurgency by the new Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), and the Muslim separatist movement of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF).

What did martial law, Marcos, Imelda, Enrile, Danding, Ver, EDSA, and all that teach us Filipinos? What have we learned?” He answers his own momentous query: “Next to nothing.”

Martial law in the Philippines (Filipino: Batas Militar sa Pilipinas) refers to the various historical instances in which the Philippine head of state placed all or part of the country under military control [1] —most prominently [2]: 111 during the administration of Ferdinand Marcos, [3] [4] but also during the Philippines' colonial period ...

During the UP IHR martial law forum in 2019, National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers Chair Colmenares narrated his experiences during Martial Law, tracing the development of his activism through his leadership in the UP Student Catholic Action(UPSCA).

Some 70,000 people were imprisoned, 34,000 were tortured and over 3,200 people were killed in the nine years after Mr Marcos imposed martial law, according to Amnesty International.

Here are five things to know about why the period under Martial Law matters in the ongoing fight for truth, justice and reparations in the Philippines. 1. Extensive human rights violations

The constitutional provisions on Martial Law — as contained in Section 18, Article VII of the Constitution — is intended to provide additional safeguard against possible abuse by the President in the exercise of his power to declare martial law or suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus. Section 18 contains six paragraphs, and ...

The essay explains the singular event of the declaration of martial law in the Philippines in September 1972 through the lens of two competing paradigms of explanation: formal-legalism (or...

Edited by Edilberto C. De Jesus and Ivyrose S. Baysic, Martial Law in the Philippines is composed of essays revisiting the martial law regime imposed by Ferdinand Marcos Sr. fifty years ago. This book provides information and analyses of its legacy of complex and contentious issues that still require resolution.