Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 What is Visual Culture?

J. Keri Cronin and Hannah Dobbie

Introduction

It is no exaggeration to say that we are surrounded by images. Take a look around you now. How many different kinds of images do you see at this moment? Think back on all of the images you encountered so far today. Can you bring them to mind? Is it possible you didn’t even notice some?

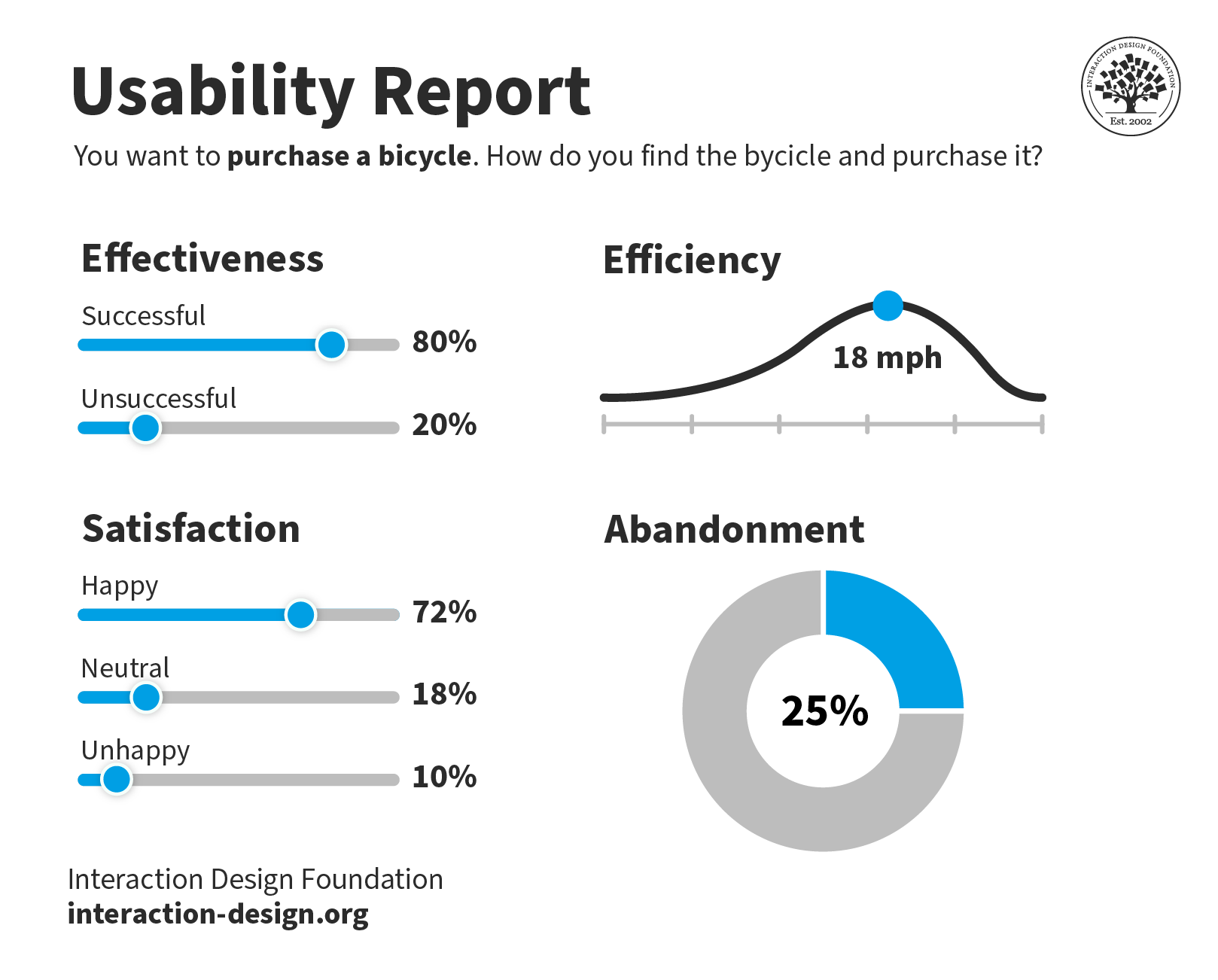

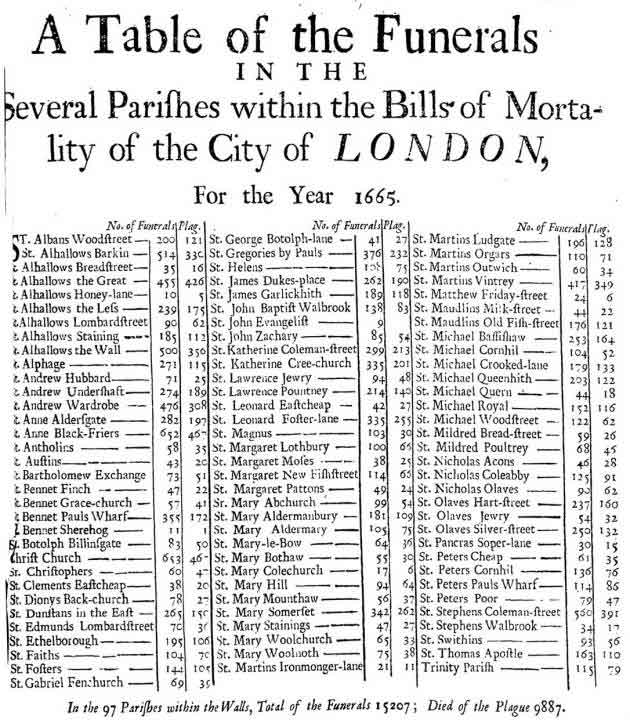

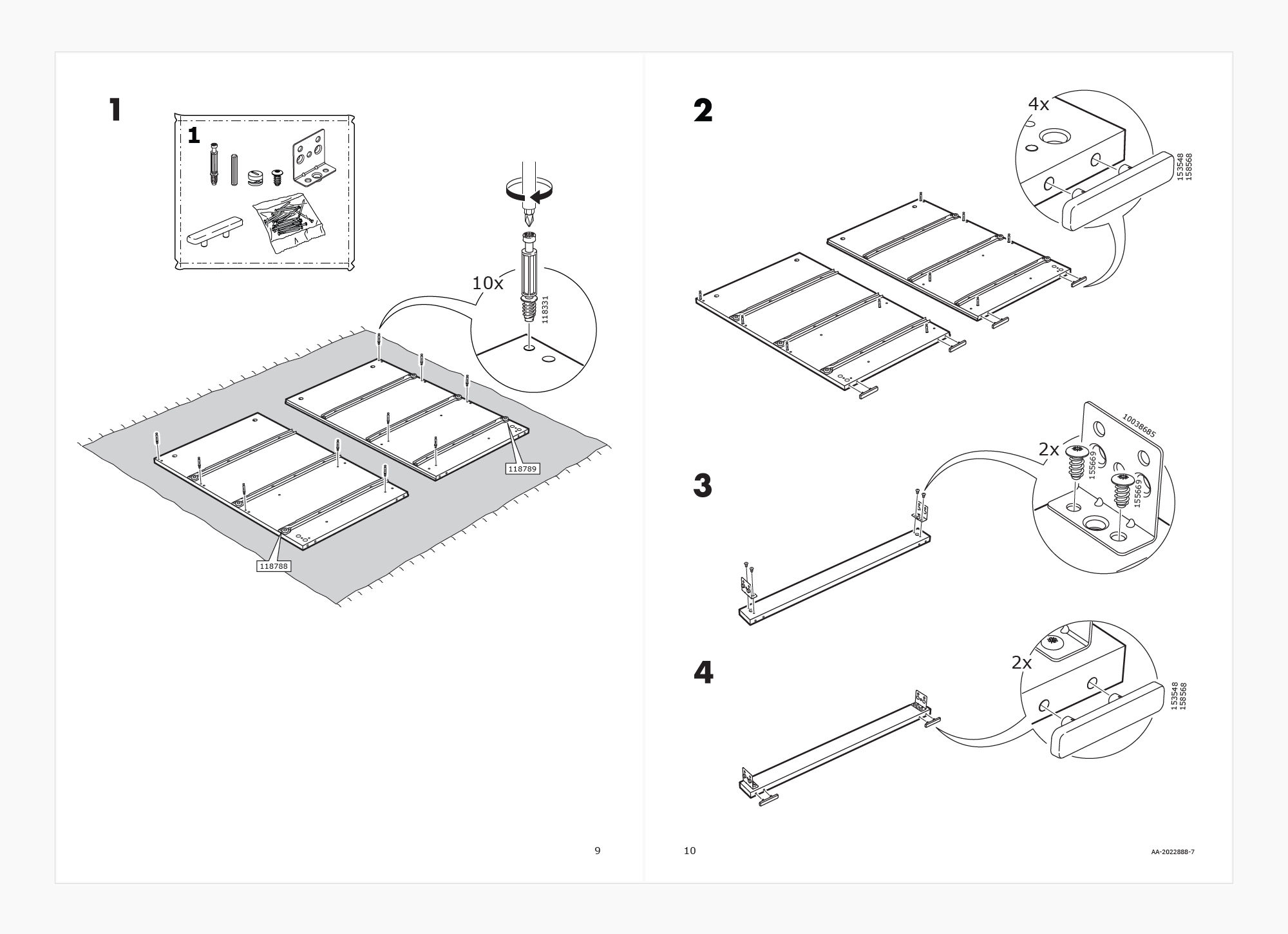

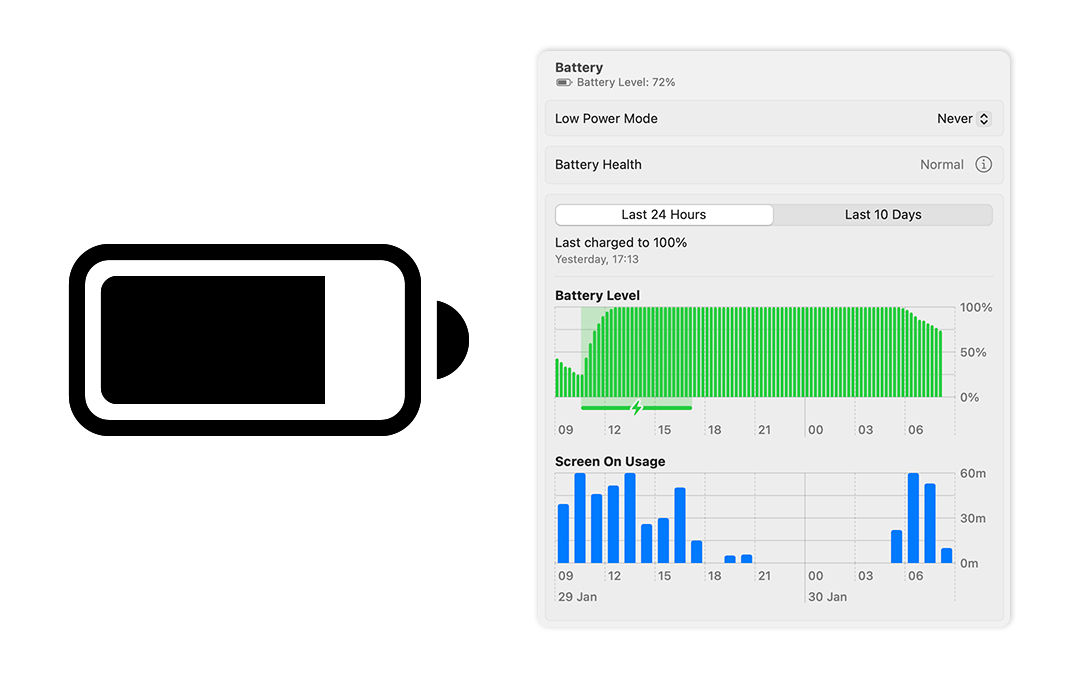

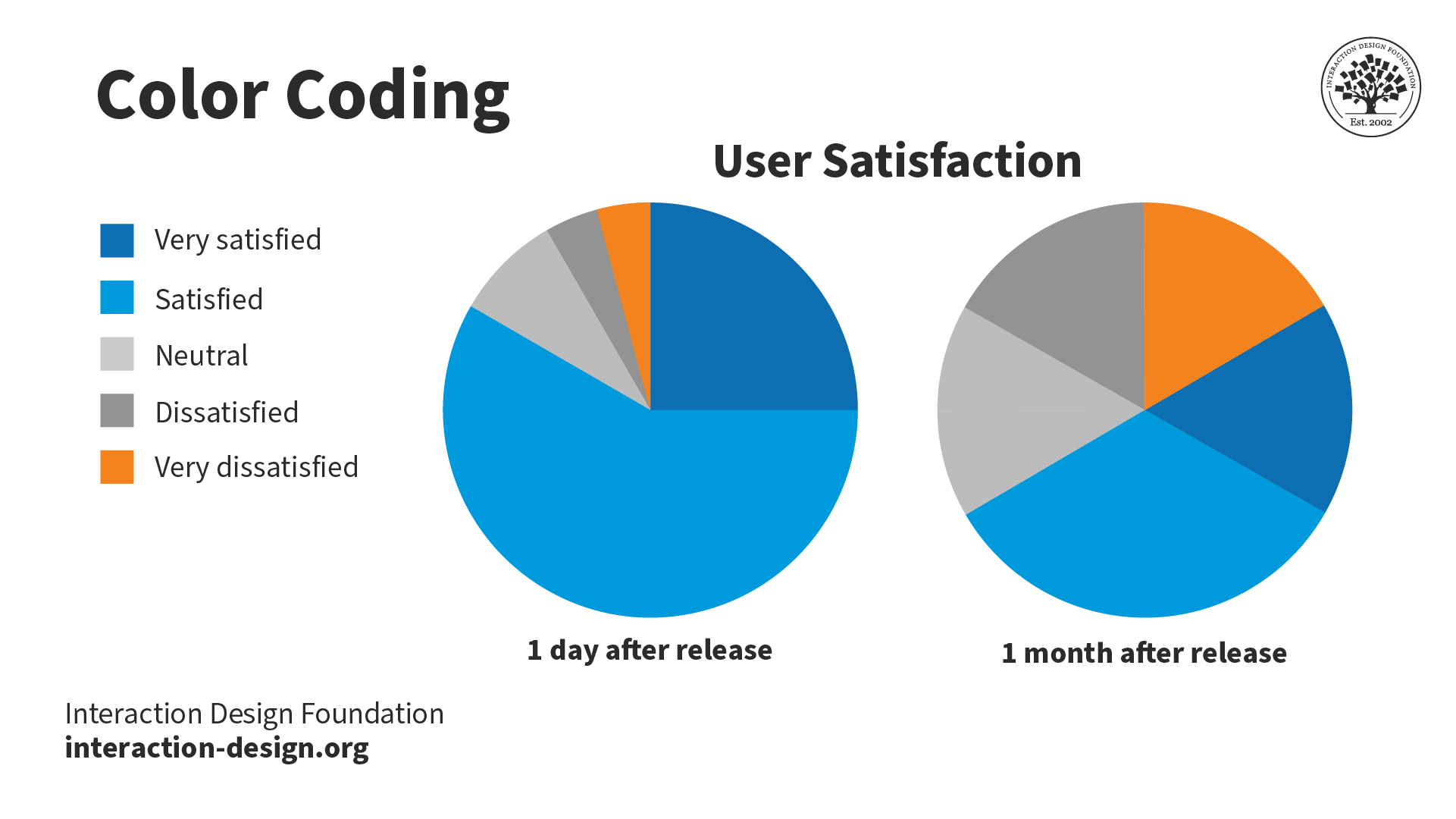

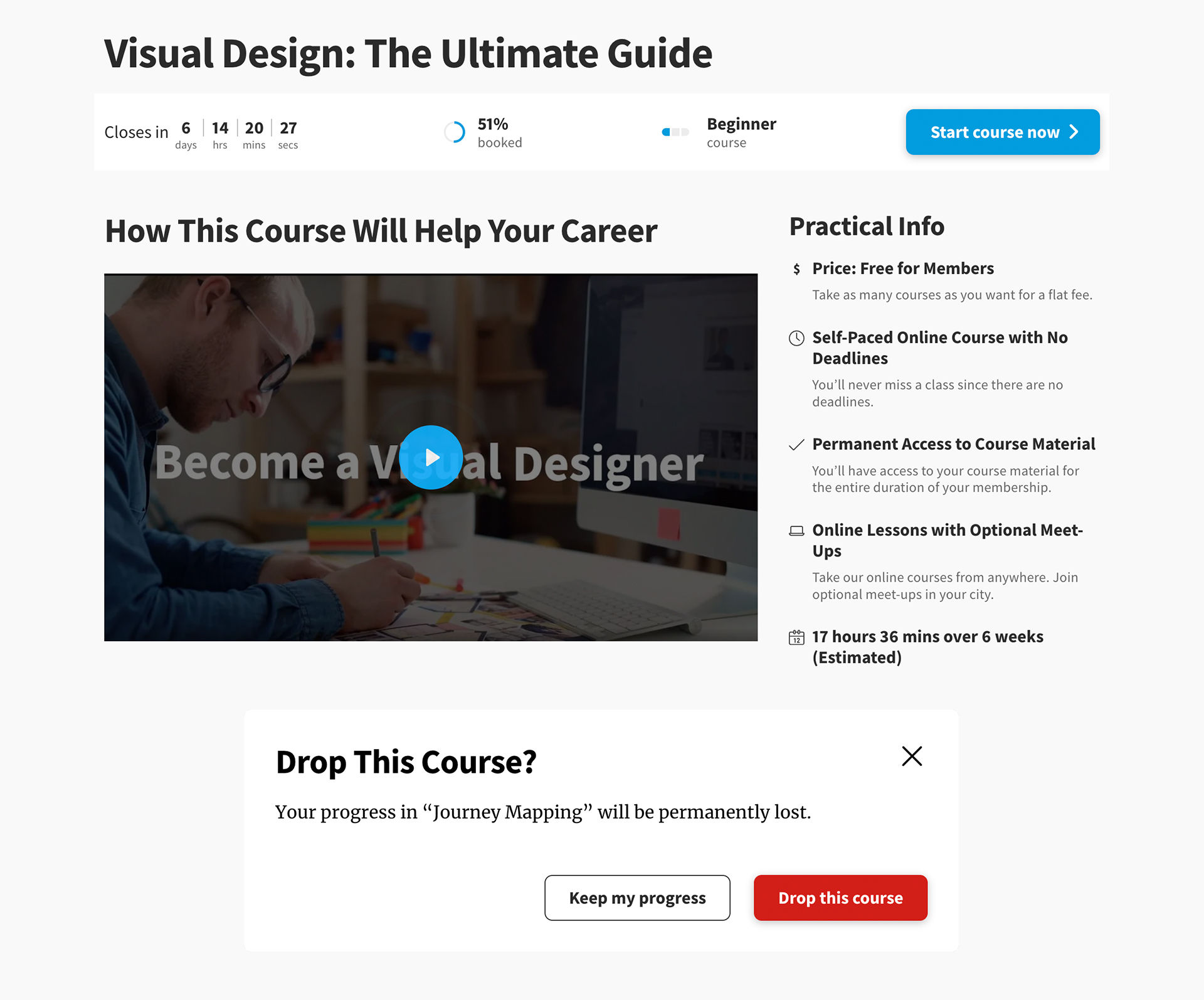

From the moment we wake up in the morning we are inundated with images. Perhaps you scrolled through social media as you ate your breakfast. Were there colourful images on the box of cereal in front of you? Do you have posters or framed family photographs in your living space? On your way to work or school you likely passed advertisements, billboards, and window displays in your local shops. Does your bus pass or parking pass have a logo or image on it? Did you stop to take a picture of your cat curled up in a patch of sun? Did your professors use images or graphs on the slides they showed in your classes today? Is there an image on the cover of the textbook in your backpack? A logo on your jacket?

We are surrounded by images on a daily basis– some would even say we are overloaded by images ! However, we don’t often stop to think critically about them. Learning to think about how images work and make meaning in our societies opens our eyes to many important social, cultural, ethical, economic, political, historical, and technological issues.

Images can help us make sense of the world. They can challenge ideas, but they can also reinforce dominant ideas and the status quo. And the meanings generated by images can be complex. How do we negotiate this?

When we talk about studying visual culture we simply mean that we are focusing our learning, research, and scholarly inquiries on images. Studying visual culture in an academic context involves thinking critically and seriously about pictures and about how they make meaning in our world. We live in a very visual world and yet we are rarely given the opportunity to learn about the ways that images make meaning.

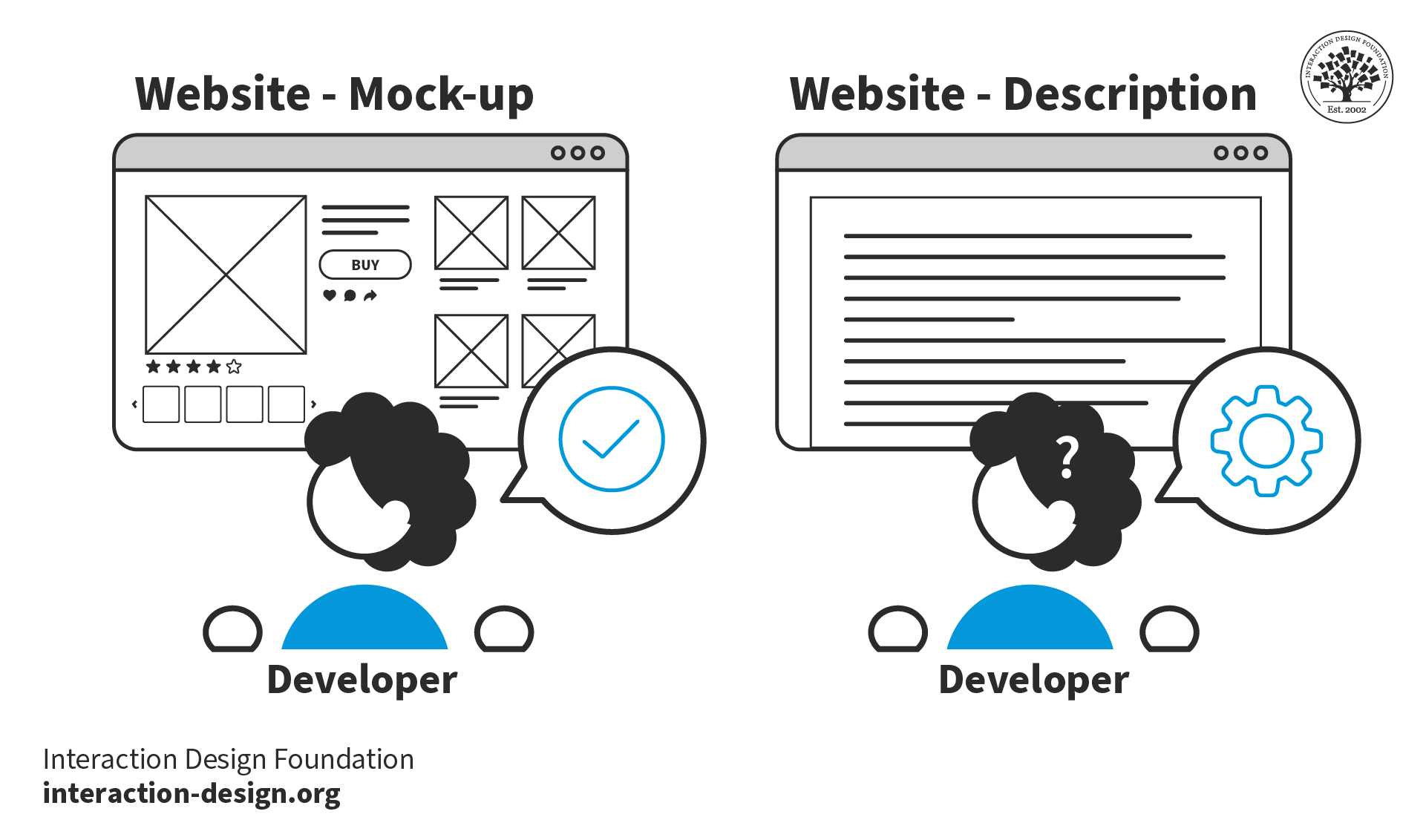

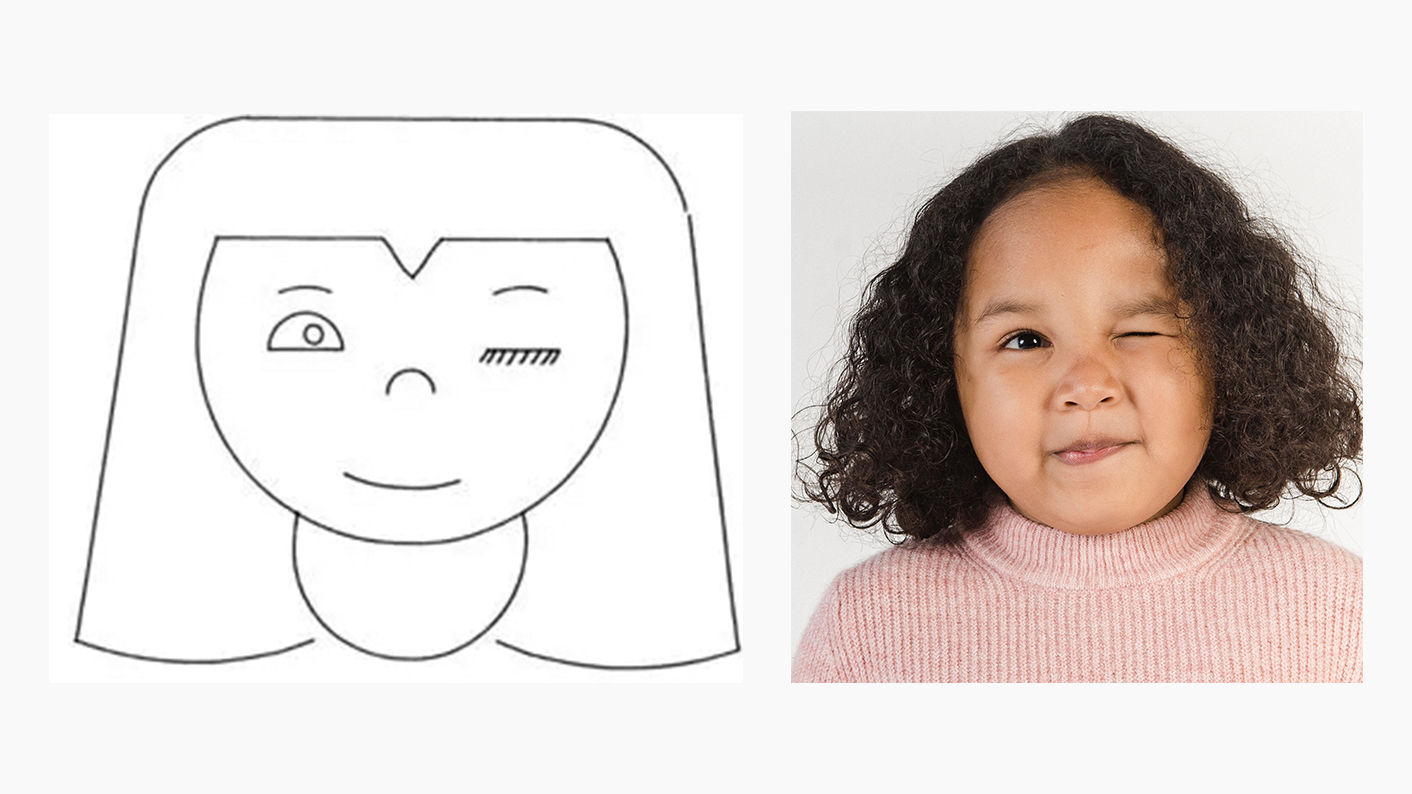

When we use the term “visual culture” we are typically referring to visual representations of something. So, your adorable baby niece isn’t an example of visual culture (she is a living being!), but the photograph of her on the invitation to her 1st birthday party is an example of visual culture. Your cat isn’t an example of visual culture, but the cartoon cat on the bag of cat food he enjoys would be. A forest isn’t an example of visual culture, but a map of the hiking trails that run through it would be. In each of these cases, the living thing (baby, cat, forest) is represented in a way that conveys specific information (a happy child, a hungry cat, a way to safely navigate the forest). In each of these cases, the representation of the baby/cat/forest offers a select interpretation of that living thing (your niece isn’t always grinning is she?), and it is this process of interpreting something complex through an always incomplete process of representation that we are interested in investigating in this course. The way an image looks, the choices the artist/image-maker made, and where the image is viewed shapes how we understand it. As we will see, there are also complex political, social, and technological issues that inform what Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright have termed the “practices of looking.” [1]

Images as “Active Players”

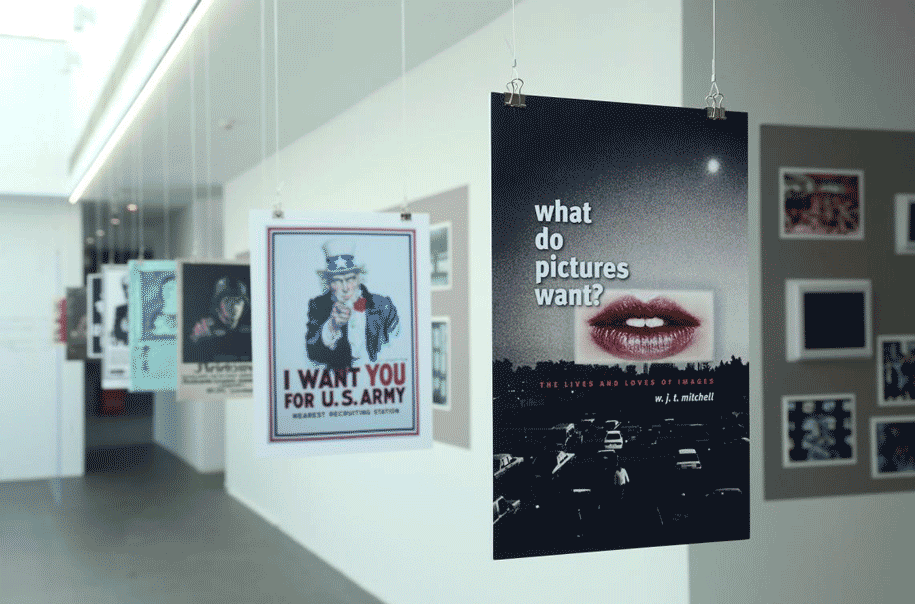

You will note that we were very deliberate about our use of language in the previous paragraph–we wrote that “images make meaning” not that they have meaning. Our point here is that pictures don’t come preloaded with a single, fixed meaning that we have to learn to decipher and decode. Rather, as W.J.T. Mitchell writes, images are “active players in the game of establishing and changing values.” [2]

What does Mitchell mean here? Let’s dig in further. In his book What Do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images , Mitchell argues that:

“we don’t just evaluate images; images introduce new forms of value into the world, contesting our criteria, forcing us to change our minds… Images are not just passive entities that coexist with their human hosts, any more than the microorganisms that dwell in our intestines. They change the way we think and see and dream.” [3]

To think of a picture as an “active player” might seem a bit odd at first, but Mitchell is not suggesting that an image is alive in the same way that, say, a puppy is.

Pictures don’t have sentience, they don’t have central nervous systems. But their very presence can influence, reinforce, challenge, and shift ideas. They can make us question what we think we know. They can be the cause of new understandings or ways of seeing the world. They can give us information. They might make us angry, sad, happy, or intrigued. And each person viewing that picture might have a different response. There is a beautiful complexity when we start to think about how pictures function in our world. And once we start to understand this, we can transpose this understanding to any image we encounter in our world.

You might be thinking “well, a picture doesn’t do all of that. The artist or person who made it does!” We will delve into this point in more detail a little later in this course, but for now we will just say that the meaning an artist or image maker intends a picture to have isn’t always the one that a viewer receives.

Let’s look at a quick example to help illustrate this point. The image below was taken by a photographer named Caroline Gunn and it is part of the Wellcome Collection , a museum, library, and archive based in London, England that focuses on health, science, and medicine.

The information accompanying this image on the Wellcome Collection’s website doesn’t give us much context about why Caroline Gunn took this image. We don’t have any information about who this little mouse is, but we can infer from the title (“Mouse Health Check”) that the mouse is being handled carefully and gently by the person performing the health check. Is this mouse a pet? Is the human a veterinarian? Does this animal live in a laboratory? We don’t know, but given that it is part of the Wellcome Collection we can assume that this picture has something to do with science, medicine, or health.

Even though there are gaps in the information we have about this picture, we still bring our knowledge, assumptions, perspectives, understandings, backgrounds, feelings, and emotions to these pictures. Some people might see this picture and smile because they think this mouse is really cute. Others might be afraid of mice and recoil a little when they look at it. Some might be reminded of a pet mouse they once had while others might be thinking of the time they had to rescue a mouse from the jaws of their overzealous housecat. If you are an animal rights activist this image might make you uneasy–perhaps this mouse is about to be the subject of a scientific experiment.

I’m sure we can add to this list of possible reactions to this photograph, but the point here is that even though Caroline Gunn would have had an idea about what she wanted to express through this photograph, other meanings are being generated as we look at it. The picture, in other words, is playing an active role.

Still unsure or unconvinced? We will be returning to this concept of pictures being dynamic participants in the meaning-making process throughout this course.

How is Visual Culture Different From Art History?

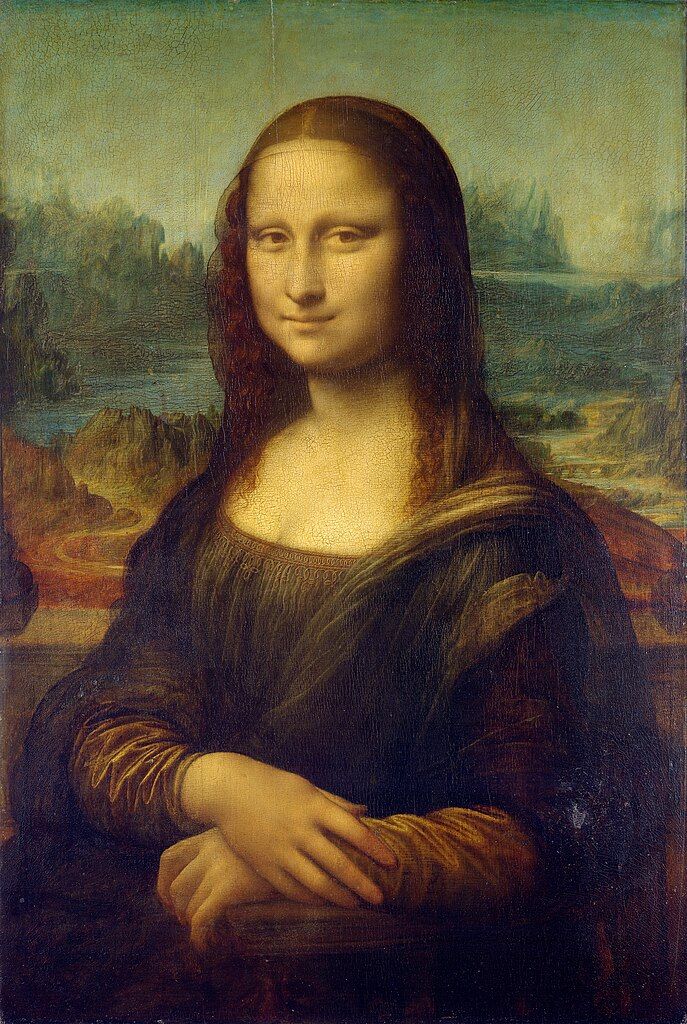

Visual culture is related to art history, but the field of inquiry is expanded. Art history has traditionally been concerned with things like the biographies and motivations of artists and/or the formal style of an image. Further, art history tends to be very limited in terms of the kinds of images focused on–typically painting, drawing, and sculpture considered to be “great masterpieces” and “things in art galleries.”

Visual culture, on the other hand, is concerned with a very broad scope of images and image makers. Famous paintings found in art galleries can certainly be the subject of visual culture inquiries, but so can advertisements, social media images, sports logos, cartoons, and passport photos (to name just a few examples). Visual culture scholars ask a very broad range of questions when they work with images and focus their inquiries on how images make meaning in the world.

Visual Culture and Accessibility

In recent years we have seen new initiatives in the fields of art history and visual culture in terms of attempting to be more accessible for a wider audience. Museums and art galleries are often leading the way on this front. For example, the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) uses an app called BlindSquare to provide exhibition and wayfinding information for visitors who are blind or partially sighted . The Dallas Art Museum has established a program where visitors who have Color Vision Deficiency (often known as “color blindness”) can borrow a set of lenses that can help visitors to the gallery “view the world with a more enriched color field .” [4]

Another example of accessibility initiatives in the context of viewing images comes, once again, from the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO). For their summer 2023 exhibition called Cassatt-McNicoll: Impressionists Between Worlds , the AGO included an American Sign Language Video that offered supplementary information about the life and work of Helen McNicoll presented by Peter Owusu-Ansah and Rae RezWell . Owusu-Ansah and RezWell are Deaf visual artists, as was McNicoll.

Reflection Exercise

Have a listen to this episode of Art Matters which features an interview with representatives from VocalEyes , a charity in the UK that brings “art and culture to life for blind and visually impaired people at theatres, museums, galleries, heritage sites and online.”

Take 5-10 minutes to do some freewriting on this topic. What did you find the most interesting or surprising about the information presented in this podcast? Does this topic raise any questions for you? Are you interested in thinking further about the topic?

Who Should Study Visual Culture?

Visual culture is something that relates to every subject of study. Even if you are not planning to major in art or visual culture you can develop skills that can help you in your chosen field of study. Are you a history major? What can those old photographs in the archives tell you about your subject? Are you a science major? Why do scientific illustrations look the way that they do? Do you plan to be a teacher? How can images help children learn in the classroom? The list is endless! Developing skills that help us analyse images can be very useful no matter where your academic studies and career take you!

Writing Exercise

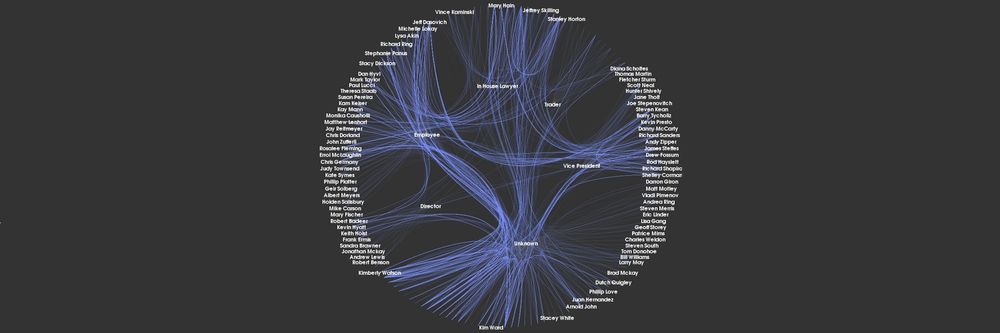

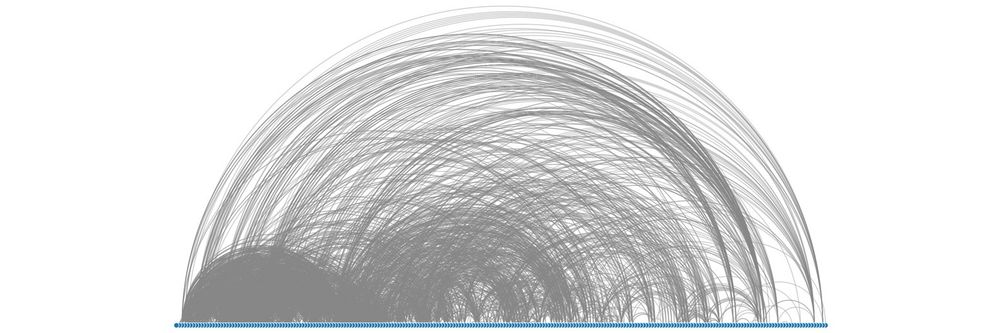

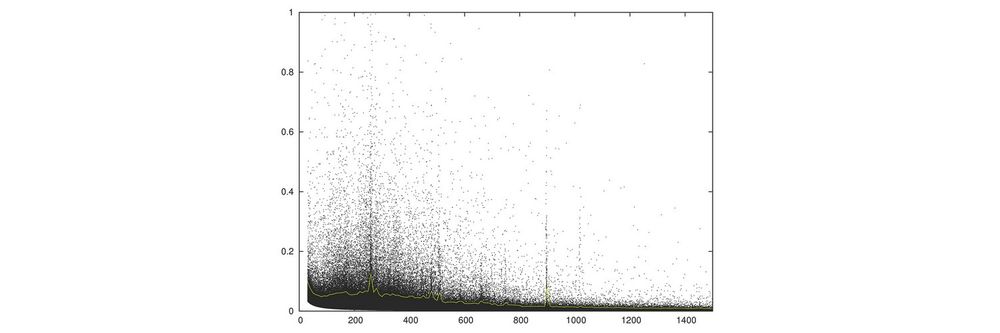

- Make a list of some of the ways that images relate to your field of study. (examples: logos, advertising, data visualisation, works of art, film adaptations of novels, medical imaging technologies, etc.)

- Pick one item from your list above. Can you think of a specific example of this type of image? What does it look like? What details stand out in your memory? Where did you see it? How does it make you feel? How does this example relate back to your larger field of study?

Spend 5-10 minutes on this exercise.

Learning to look carefully and to ask questions about what you see is a very important skill to have. For example, many medical schools are now requiring their students to take courses in art history and/or visual culture so that they become more skilled at careful looking and detailed observation . Studying visual culture can lead to career paths in the arts, media, museums, advertising, social media, etc., but more importantly this kind of learning can help you become a more astute consumer of the images that you see every single day.

Becoming a critical thinker when it comes to assessing and analysing images can help you judge whether what you read online or see on television is credible. While there is a long history of images being manipulated and edited, this has become an even more complex topic with the rise of AI tools in recent years .

Critical Thinking

You will often see the phrase “critical thinking” or “thinking critically” in these pages. What do we mean by these terms?

bell hooks describes critical thinking as “discovering the who, what, when, where, and how of things–finding the answers to those eternal questions of the inquisitive child–and then utilizing that knowledge in a manner that enables you to determine what matters most.” [5]

Critical thinking does not necessarily mean taking a negative stance or perspective. It is very possible–and quite desirable, actually–to think critically about an image or an idea you are excited about or really enjoy.

Critical thinking is an important concept in the Arts and the Humanities. When we talk about engaging in critical thinking we are simply talking about asking deep questions about whatever it is we are focusing on. We then support that process of questioning through evidence.

In our everyday language we often use the word “critical” to mean something bad or negative. For example, if we say something like “my father was critical of my outfit” we mean that our dad didn’t like what we were wearing. This has a negative connotation.

However, when we use the word “critical” in the phrase “critical thinking” we are not necessarily taking a negative point of view. All we mean when we talk about “critical thinking” is that we are interrogating our object of study–asking questions and thinking deeply about how it works to make meaning in our world. It is perfectly acceptable to engage in critical thinking about things you like–say, for instance, your favourite movie, novel, or video game.

Throughout this course we will be developing critical thinking skills to help us make sense of how images work in our world.

- Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright, Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. Oxford University Press. ↵

- W.J.T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), p. 105. ↵

- W.J.T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), p. 92 ↵

- Rhea Nayyar, "A Better Museum Experience for Color-Blind Visitors" Hyperallergic (Oct 23, 2022): https://hyperallergic.com/771685/dallas-art-museum-color-blind-visitors-enchroma/ ↵

- bell hooks, Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom (New York and London: Routledge, 2010), p.9 ↵

Look Closely: A Critical Introduction to Visual Culture Copyright © 2023 by J. Keri Cronin and Hannah Dobbie is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Visual Culture – Definition, Examples, History & More – Art Theory Glossary

Table of Contents

What is Visual Culture?

Visual culture refers to the study of visual images, objects, and practices in society. It encompasses a wide range of visual forms, including art, photography, film, advertising, and social media.

Visual culture examines how images and visual representations shape our understanding of the world around us. It explores the ways in which visual communication influences our perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors.

Key Concepts in Visual Culture

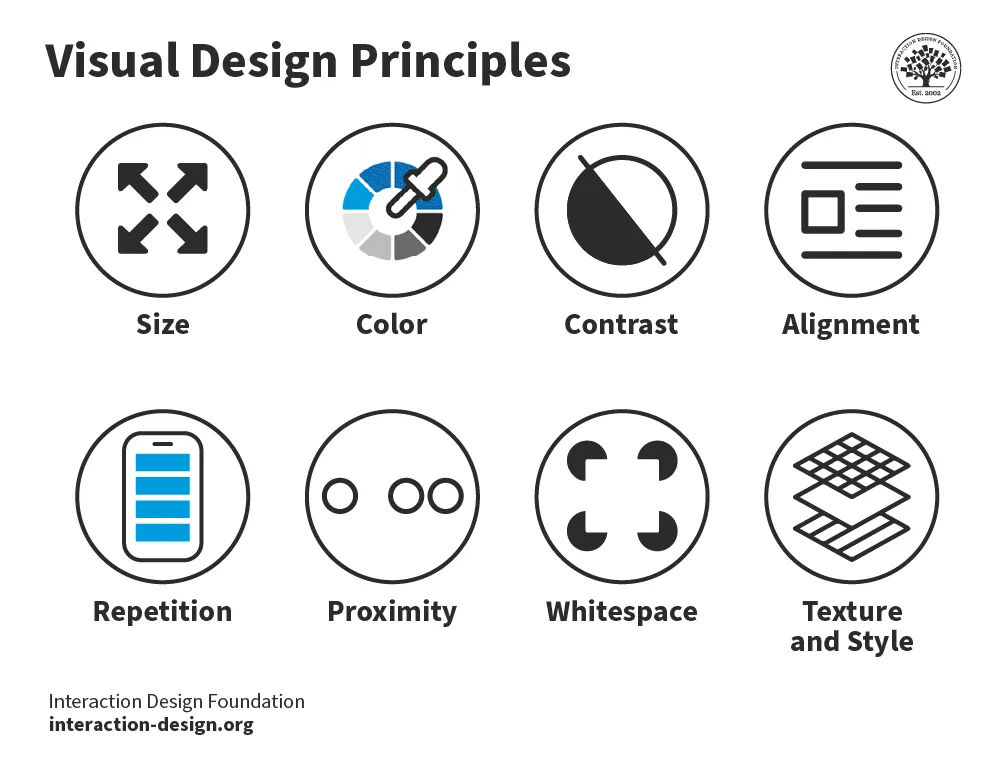

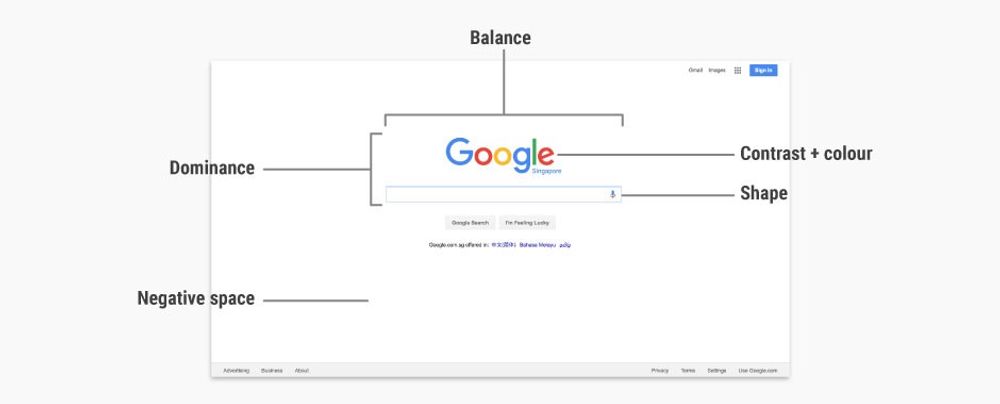

Some key concepts in visual culture include representation, interpretation, and visual literacy. Representation refers to how images and visual symbols convey meaning and represent ideas, identities, and values. Interpretation involves analyzing and making sense of visual images and understanding their cultural significance. Visual literacy is the ability to interpret and create visual messages effectively.

Other important concepts in visual culture include visual rhetoric, visual ethics, and visual semiotics. Visual rhetoric is the use of visual elements to persuade, inform, or entertain audiences. Visual ethics involves ethical considerations related to the creation and consumption of visual images. Visual semiotics is the study of signs and symbols in visual communication and how they convey meaning.

The Role of Visual Culture in Society

Visual culture plays a significant role in shaping our cultural identities, beliefs, and values. It influences how we perceive ourselves and others, as well as how we understand and interact with the world.

Visual culture also plays a crucial role in politics, advertising, and social movements. Images are often used to convey powerful messages, evoke emotions, and mobilize support for various causes.

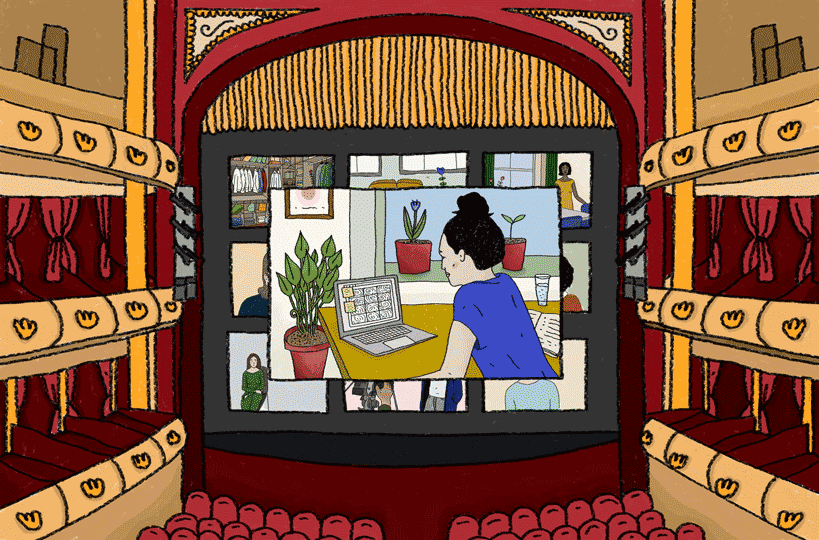

Visual Culture and Technology

Technology has had a profound impact on visual culture, transforming the way we create, consume, and share visual images. The rise of digital media and the internet has made it easier for people to create and distribute visual content on a global scale.

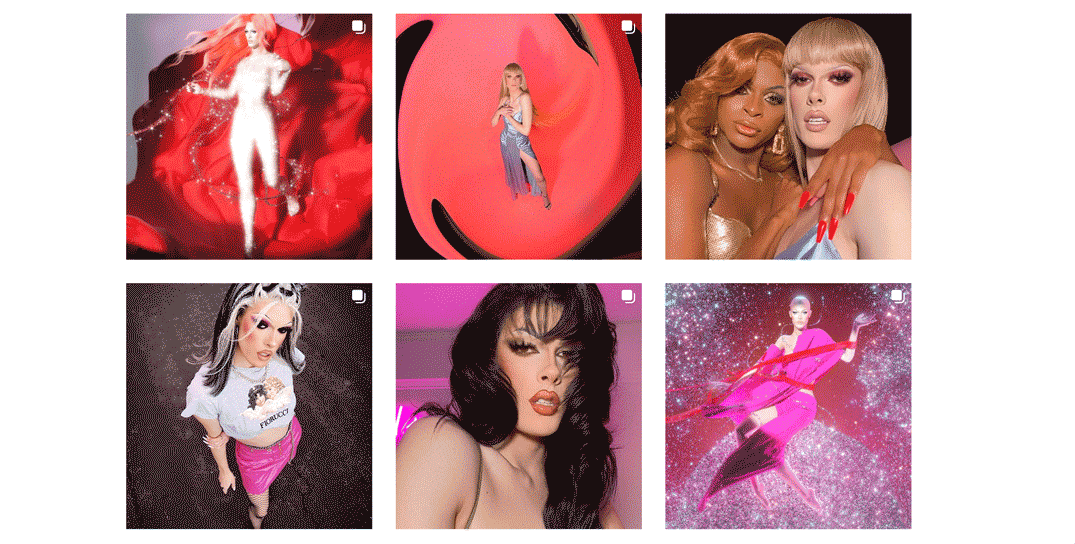

Social media platforms like Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok have become popular tools for sharing visual images and connecting with others. Virtual reality and augmented reality technologies are also changing the way we experience and interact with visual content.

Visual Culture and Globalization

Globalization has led to the spread of visual culture across borders and cultures, influencing how people around the world perceive and engage with visual images. Globalization has also facilitated the exchange of visual ideas, styles, and practices between different societies.

Visual culture has become a powerful tool for promoting cultural diversity, challenging stereotypes, and fostering cross-cultural understanding. It has the potential to bridge cultural divides and promote dialogue and collaboration between people from diverse backgrounds.

Critiques of Visual Culture

Despite its many benefits, visual culture has also been criticized for perpetuating stereotypes, promoting unrealistic beauty standards, and manipulating public opinion. Some critics argue that visual images can be used to manipulate and control people’s perceptions and behaviors.

Others have raised concerns about the impact of visual culture on mental health, particularly among young people who are constantly exposed to idealized images of beauty and success. Critics also point to the potential for visual culture to reinforce social inequalities and perpetuate harmful ideologies.

In conclusion, visual culture is a complex and dynamic field of study that examines the role of visual images in shaping our perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors. It encompasses a wide range of visual forms and concepts that influence our understanding of the world around us. By critically analyzing and engaging with visual culture, we can better understand how visual images shape our cultural identities and influence our interactions with others.

JerwoodVisualArts

Hundreds of articles, guides and free resources

Email: [email protected]

Follow Us !

Copyright © 2024 All Rights Reserved

Privacy policy

Cookie Policy

Art Theory: Visual Culture

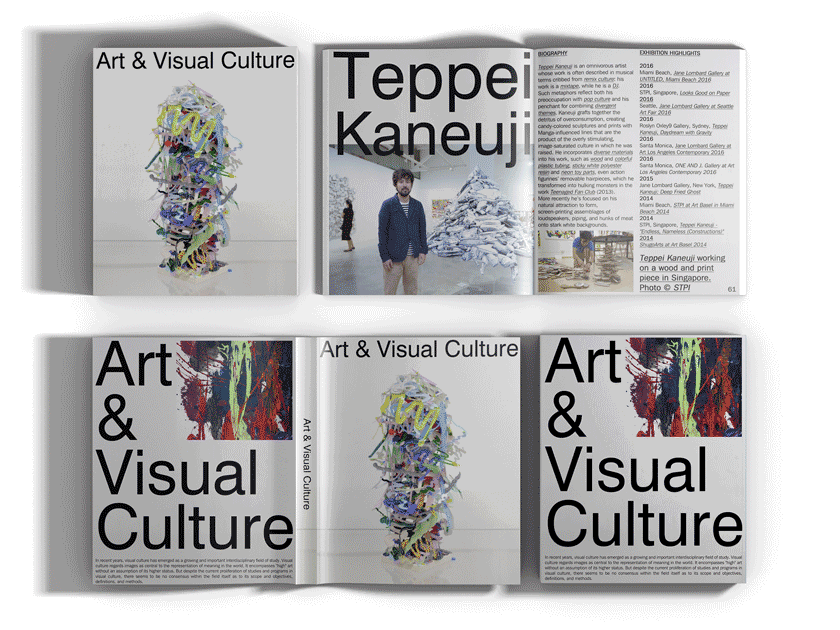

*This article is part of Arts Help's Art Theory series.

In 2014, Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary coined the term “culture” as the word of the year. An uptick in “culture” definition searches on Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary website implies that, in 2014, “Confusion about culture was just part of the year’s “culture.” As New Yorker reporter Jonathan Rothman suggests, an effort to entirely understand the sociological concept of culture is elusive, no matter the year . Human beings are in a continuous search to grasp how culture is defined, practiced, and embodied. What’s more is that culture is an all-encompassing term that blanket describes the complex and manifold matters for which humans interact, believe, think, create, and behave–– there is no one way to categorize culture as it is ever-changing, always diverse, and immeasurable.

In action, the word “culture” is often compounded with an additional term or phrase: a descriptor that aims to compartmentalize the different modes through which culture exists and is enacted. In 2014, compound terms including culture were searched online just as fervently as the word culture alone . Phrases like pop culture, consumer culture, start-up culture, high culture, media culture, as well as, violence culture, rape culture, and cultures of silence include just a handful of the ways that the word culture is adapted and given expanded meaning. As apt as the quest was to understand the expansive notion of culture seven years ago (and many years before), the journey still continues. In 2021, the concept of what culture is, how it operates, and the ways in which it transforms is still at the height of society’s minds and systems.

One formation, or categorization, of the term culture has accrued notoriety over the past two decades as it seemingly tries to make sense of all the rest. Visual culture , as Lauren Schleimer puts into words “is a term that refers to the tangible, or visible, expressions by a people, a state or a civilization, and collectively describes the characteristics of that body as a whole.” Schleimer’s definition of visual culture stems from an anthropological blueprint, and the term now encompasses many more concepts.

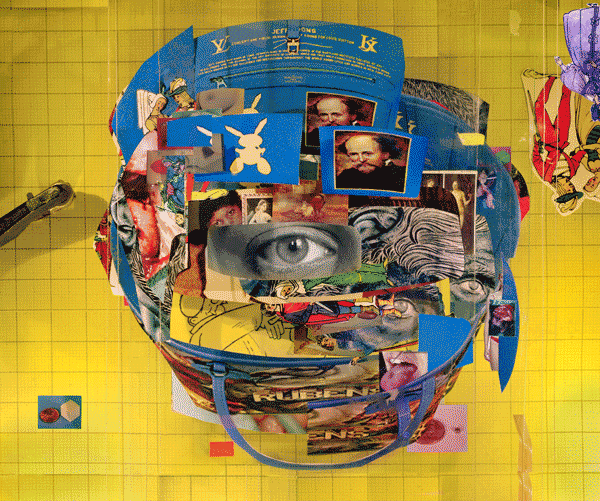

Visual culture is an interdisciplinary notion that constitutes the visual as a precursor for knowledge and understanding. Leah Houston articulates , “visual culture is a way of studying” the world and its relations through means of “art history, humanities, sciences, and social sciences. It is intertwined with everything that one sees in [their] day to day life––advertising, landscape, buildings, photographs, movies, paintings, apparel––anything within our culture that communicates through visual means.” For transdisciplinary theorist Irit Rogoff, “visual culture opens up an entire world of intertextuality in which images, sounds and spatial delineations are read on to and through one another, lending ever-accruing layers of meanings and of subjective responses to each encounter we might have with film, TV, advertising, art works, buildings or urban environments”. Visual culture is “a transdisciplinary and cross-methodological field of inquiry.”

While the concept and nature of visual culture is not new, its popularization as a field is relatively young. In Mieke Bal’s 2003 essay Visual Essentialism and the Object of Visual Culture , Bal questions whether visual culture can be defined as a positive, productive discipline. She expresses , “rather than declaring visual culture studies either a discipline or a non-discipline, I prefer to leave the question open and provisionally refer to it as a movement. Like all movements, it may die soon, or it may have a long and productive life”. Contrary to Bal’s sentiments, the contemporary notion of visual culture is widespread. In contemporary times, visual culture has proven to outlast its particular moment in history. In fact, the nature of visual culture is expansive enough that it now operates as a highly popular field of study. Countless academic institutions offer visual culture studies as a major for undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral degrees, and moreover, several institutions have dedicated visual culture departments.

In a written response to Bal’s article, art historian James Elkin meets Bal’s statements with tension, and argues positively for the interdisciplinarity of the emerging visual studies field. Elkins implies that visual culture studies offer the space for disciplines such as art history, media studies, and linguistics to come together; it appeals to “those who want to bring together several fields to create a meeting place of disciplines, a kind of bazaar or collage of simultaneous and kaleidoscopically alternating disciplinary fragments”. In extension to Elkin’s thoughts, the study of visual culture brackets various societal shifts, bridging notions of postmodernism, poststructuralism, postcolonialism, and the information age into a realm of intersectional study. Elkin’s quotes theorist W.J.T Mitchell , “‘Visual culture starts out in an area beneath the notice of these disciplines – the realm of non-artistic, non-aesthetic, and unmediated or “immediate” visual images and experiences.’ It is about ‘everyday seeing’, which is ‘bracketed out’ by the disciplines that conventionally address visuality”.

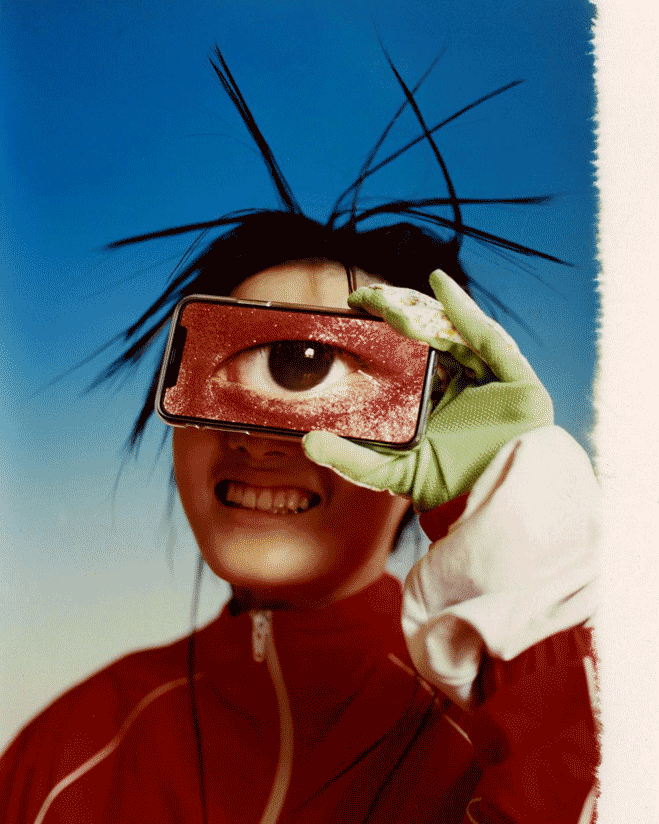

Despite academic bearings, the notion of visual culture is prudent to contemporary life. In contemporary society, a “shift in emphasis toward an increasing importance of the visible…is due principally to two related factors: the organization of economies and societies with and by images and the related hyper-development and intensification of visual technologies.” Marquard Smith articulates the ways in which apparatuses of visual culture are almost always multi-sensory, stating that “the internet always involves a coming together of text and image, of reading and looking simultaneously; that cinema always comprises sight and sound, viewing and hearing at once; that video phones necessitate a confluence of text (texting), image (photographing/videoing), sound (ringtones), and touch (the haptic or tactile bond between the user and [their] unit)”.

Visual culture flows through the circuits of everyday social, economic, political, and scientific systems––the broad culture of the 21st century is supremely visual and multisensorial. Images (photographs, pictures, illustrations, videos, and so on) precipitate beyond the realm of contemporary art; they are active elements that coordinate functions of the internet, journalism, marketing, computer technologies, systems of surveillance, scientific practice, and more. Likewise, the pinnacle of visual exchange, social media, relies on images as well as visual and sensory communication in order to exist and persist. There is a sea of images directly outside the eyes of most individuals: humans come into contact with rows of visual objects through their cell phone devices, newsfeeds, and streaming accounts. Humans are in a constant relationship with “a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution.”

The definition of the “visible” is changing due to the rapid advancement of technologies; new technologies have succeeded in making that which was never visible before perceivable. Newfangled forms of visual media––from video conferencing to augmented reality––continue to change the way that humans communicate, experience, learn, and exchange. Furthermore, individuals’ access to visual exchange platforms is perpetuating how visual content is made, circulated, and aestheticized––these platforms give space for the development of visual mediums, expanding and revolutionizing the way that art, design, photography, performance, music, marketing and so on are traditionally practiced and determined.

In addition, these technologies simply change the way that images are seen and understood. Through the immense popularity of social platforms such as Instagram and YouTube the visual world intersects with the contemplative world. The systems of social media are just one aspect of contemporary visual culture. Yet, the advancement of these visual exchange platforms exemplifies a shift in how contemporary culture tends to embody visualization as a means to develop intersectional understanding and take action towards the social and economic consequential issues that prevail global societies.

Visual culture is fluid, continuously adapting, and as humans we constantly find new ways to engage with, contemplate, and question the world through visual imagery. In the words of W.J.T Mitchell , “The most far-reaching shift signaled by the search for an adequate concept of visual culture is its emphasis on the social field of the visual, the everyday processes of looking at others and being looked at. This complex field of visual reciprocity is not merely a by-product of social reality but actively constitutive of it”. While perhaps the exact theory of visual culture is challenging to pinpoint, it is without dispute that visual culture is a pivotal element in the apparatuses of art, art history, design, media as well as contemporary global societies. As a field of study, and everyday notion, the theory of visual culture argues for how images influence new ways of thinking, understanding, and mediating. It is a way of looking at the world to make sense of the universe and humanity’s divergent and complex relations.

Mallory Gemmel

Mallory is an interdisciplinary writer & editor. She has a BFA in Photography & Curatorial Studies from Emily Carr University & a Master of Arts in Comparative Media from Simon Fraser University.

May we suggest a tag?

May we suggest an author.

The ‘Politics of Representation’ in Post-Colonial Studies

Representation refers to how ideas, beliefs, values, and other aspects of different societies and cultures are imagined, expressed, shared, and understood by others, in both language-based or visual form.

This is considered ‘political’ because of considerations linked to who holds the power to create representations; whose voices are heard and amplified; which cultural practices are privileged or suppressed; and how the representations are interpreted and weaponised as a tool for domination or resistance, whatever the original intentions of the people who created the representation (Said 1973; Lockmann 2004).

When used in the context of post-colonial studies, the term “politics of representation” refers to how colonisers and colonised peoples were depicted and understood, as well as how their relationship was interpreted.

This includes examining power dynamics between the two groups, understanding the cultural and historical context for their interactions, and looking at how colonization still impacts present-day society.

Assessing the politics of representation makes it possible to better understand the complexities behind colonialism , imperialism, racialisation, and other dynamics that have shaped our contemporary world.

In this essay I will first address the issue of representation in anthropology, with a particular focus on the links between the discipline and colonialism, which led to much scholarly debate and criticism in the 1980s about potential bias in ethnographic and other scholarly representations of the colonised during the colonial era, which subsequently became the foundation for the emergence of post-colonial studies (Lockmann 2004).

I will then broaden the discussion to include other forms of representation, including the representation of power relations through discourse, photography and movies.

Anthropology is a representational discipline in which anthropologists seek to contextualize and interpret the complexities of the societies they study, representing their findings in the form of documentation, images, photos, artifacts, and stories kept in their archives or displayed in exhibitions and museums, scholarly papers and presentations made at conferences, as well as articles and books written for a general audience (Vargas-Cetina 2013).

It initially emerged as the study of the ‘primitive’ and the ‘exotic,’ with its origins firmly rooted in the power structures of the colonial era (Said 1973; Assad 1973; Lockmann 2004; Vargas-Cetina 2013; Gleach 2013).

Early anthropologists gained access to the subjects they were to study as part of the colonial apparatus, and while they may have tried to be neutral observers, it would be naïve to claim that their positionality, which hinged on the power inequalities in the relationship between coloniser and colonised, did not shape the outcomes of their research (Lockmann 2004).

This influence was one of the main thrusts of Said’s argument about the flawed representation of colonised nations by scholars representing the Orient –

‘… for a European or American studying the Orient there can be no disclaiming the main circumstances of his actuality: that he comes up against the Orient as a European or American first, as an individual second. And to be a European or an American in such a situation is by no means an inert fact’ Said 1973

(Said 1973, as cited in Lockmann 2004: 188).

Thus, anthropology came into being as the study by Europeans of non-European societies ruled by European powers, with the resulting representations meant for a European audience (Assad 1973: 90).

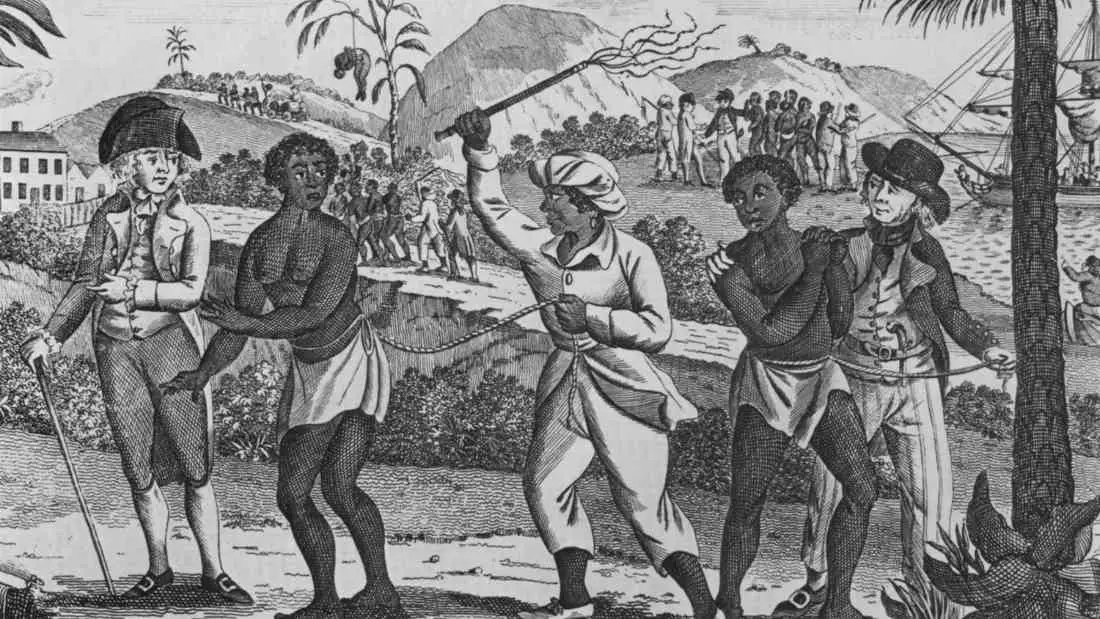

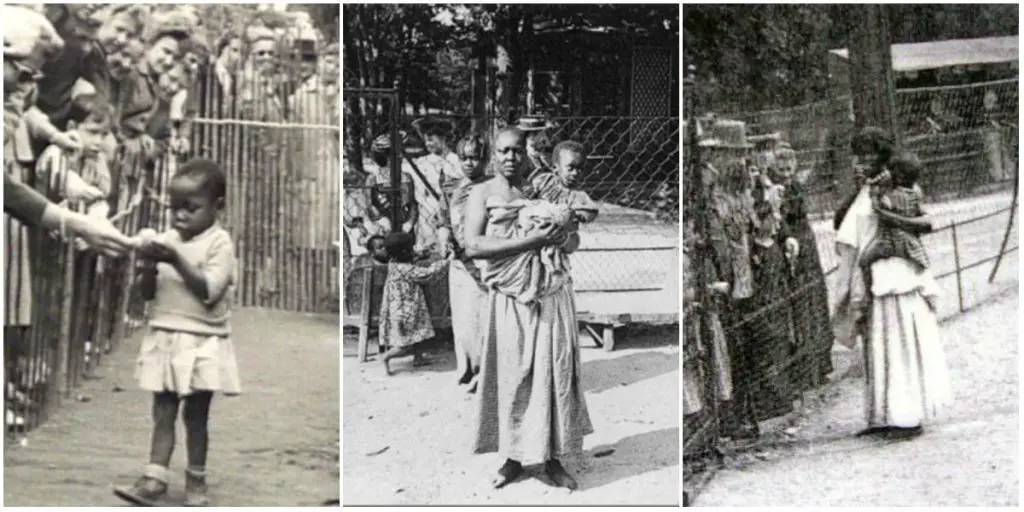

Beyond ethnographic representations created by early anthropologists, there were of course other forms of representation which shaped the Western public’s views of colonised peoples and cultures.

Artwork, literature, photography, cartoons and even human ‘zoos’ have been used to propagate ideas about ‘the Other’ that constructed a distorted vision of these societies while also reinforcing colonial power relations (Said 1973; Lockmann 2004; Vargas-Cetina 2013).

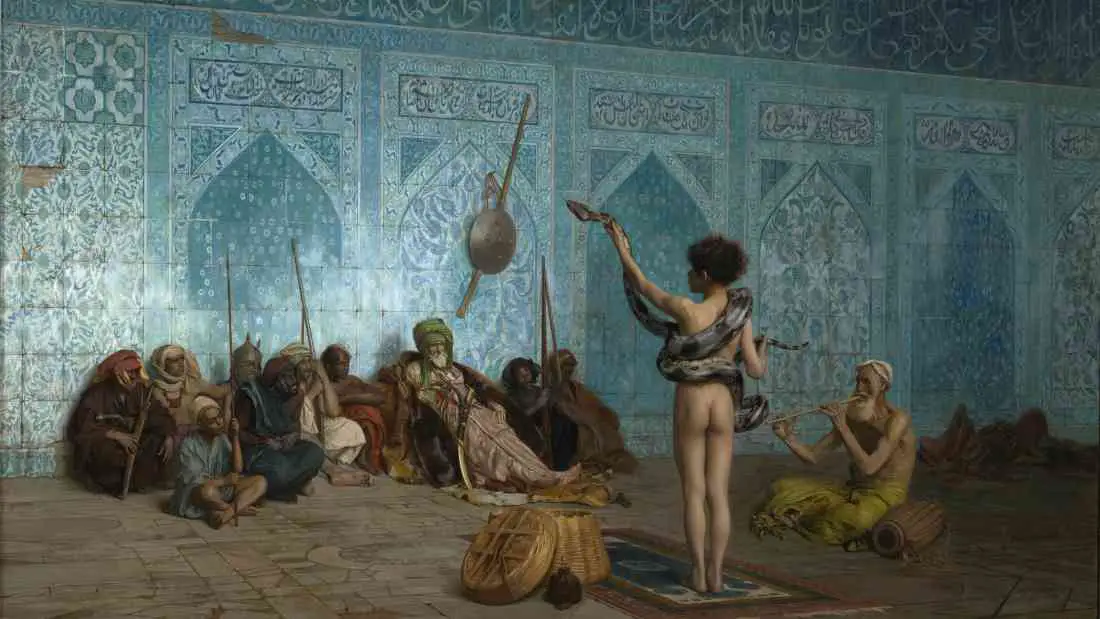

One of the seminal texts in the field is Edward Said’s Orientalism , which examines the politics of representation in the context of colonialism and imperialism in Eastern countries.

He argues that Western (European and American) perceptions of the East were shaped by a cycle of representation that presented “the Orient” as exotic, mysterious, and inferior.

The core premise perpetuated by the dichotomization of the East and the West, was the ‘othering’ of the East, based on preconceptions and attitudes that had little or no foundation.

In fact, many of the representations in question were often produced with little regard for or knowledge of the culture they were representing.

Through this process, he argues, colonised cultures were reduced to a set of stereotypes that explained and justified the inequality and oppression perpetuated upon them by Western powers (Said 1973; Lockmann 2004; Shohat & Stam 2014; Lutz and Collins 2020).

In the article ‘Shattered Myths,’ Said posits that much of the body of knowledge created by European and American scholars about ‘Arab society’ was in fact an exercise of ‘mythification,’ since ‘Arabs all told number over a hundred million people and at least a dozen different societies’ so it was impossible to study them ‘as a single monolith’ (Said 1975: 90).

He illustrates his point by referring to several examples of blinkered representations by Orientalists or Arabists (scholars who profess ‘to know the Arabs’ (Said 1975: 91)), focusing on articles written by Professor Gil Carl Alroy and Dr Harold Glidden as flagrant examples of the contentious ‘othering’ of non-Western cultures.

The former author makes several sweeping statements about Arabs, claiming that they are obsessed with violence and bloodshed and ‘psychologically incapable of peace,’ citing as proof of his claims various articles which appeared in Egyptian newspapers, ‘as if the two, Arabs and Egyptian newspapers, are but one’ (Said 1975: 90).

The latter, on the other hand, published an article in the American Journal of Psychiatry which purported to be a distilled psychological analysis of the Arab worldview, namely an obsession with revenge, the inability to be objective and make rational decisions, and the predilection for constant conflict, which were presented as the antithesis of Western ideals of peace and harmony (Said 1975: 91).

These two examples are not only reflective of a reductive view of Arab society, but are also highly political, since such representations can be, and in fact have been, used to legitimize and even encourage aggressive policies by Western powers, masking their aggression as an attempt to control or police the behaviour of people living in eastern countries.

The political implications of the abovementioned articles are very clear, but in other representations, such as those in photography and film, they can be covert, and one could argue, even more pernicious.

Through a careful selection of images and composition, photographers and filmmakers create narratives which have a powerful effect on how audiences understand and imagine the people and cultures being depicted (Shohat & Stam 2014; Lutz and Collins 2020).

The proliferation of photography and videography coincided with the heights of the imperial expansion projects of countries such as Britain, France and the United States.

Movies were much more accessible than literature or scholarly articles, creating new opportunities to craft representations of other cultures aimed for the consumption of the general public, including the illiterate (Shohat & Stam 2014).

When films were first introduced, audiences accepted what they saw on the big screen as fact, unaware of how filmmakers were manipulating the images and narratives to create different stories and portrayals.

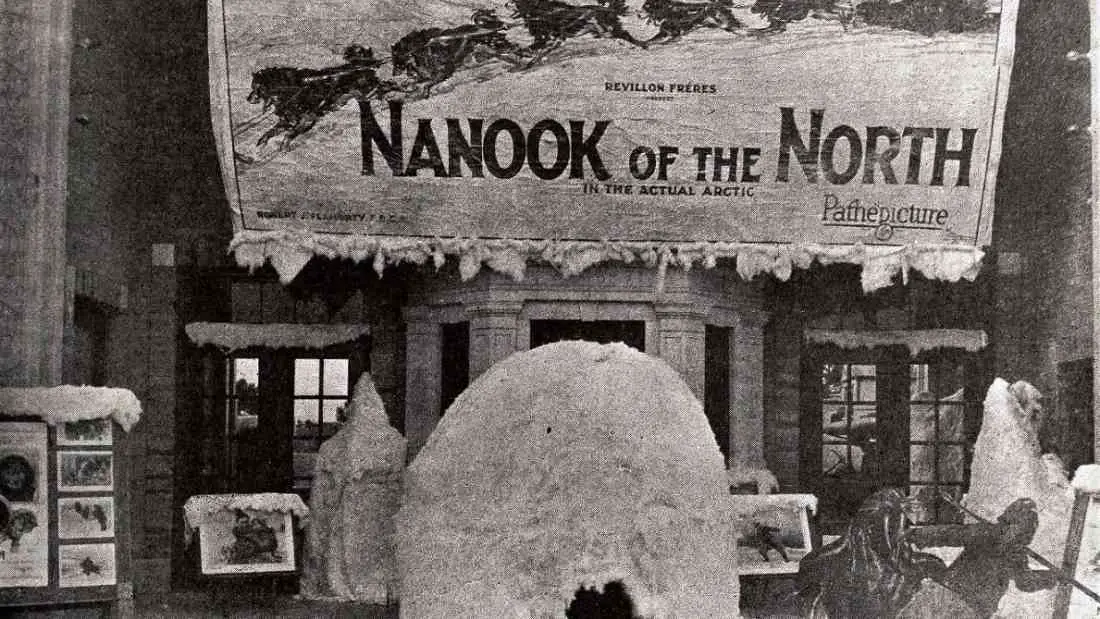

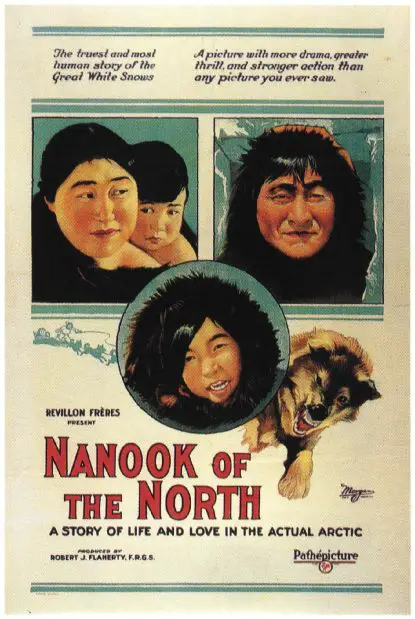

A case in point is Nanook of the North: A Story of Life and Love in the Actual Arctic , which was released by Robert Flaherty in 1922 and became a box-office hit.

The film was hailed as the first ‘documentary,’ but in truth it was fiction.

The characters in the film were actors, and the family that the camera supposedly followed unobtrusively for a year were simply acting a part.

Furthermore, by then the Inuit were using guns to hunt, but the movie showed them using old-fashioned harpoons.

Flaherty justified misrepresenting the lives that contemporary Inuit were living as an attempt to capture and ‘preserve’ on film the Inuit’s culture before it was tainted by modernity – however the audience who ended up watching the film accepted it as factual and a representation of the way the Inuit lived in 1922, and not a recreation of the ways of the past (Mackay 2017).

A similar phenomenon occurred when photographers and videographers travelled to far flung places in the empire.

The images and films they produced presented and ‘otherizing’ the alien cultures and landscapes as exotic and inferior to those of the West (Said 1973; Lockmann 2004; Vargas-Cetina 2013).

The natives were pictured as ‘primitive’ and infantilized, with videographers such as Martin and Ola Johnson, in the 1920s, portraying them as a form of wildlife, comparable to monkeys (Shohat & Stam 2014: 122).

This was by no means an accident, for the Western imagination was at the time enamoured of the Darwinian notion that Westerners were the apogee of the evolutionary process, while the natives discovered in the far-flung parts of the globe were inferior beings, much lower down on the evolutionary ladder.

This evolutionary perspective led to atrocities such as the caging of Ota Benga, an African Pygmy, at the Bronx Zoo, for the delectation of the American public; and the study of the anatomy of black people by zoologists, who compared them to mandrills and baboons (Shohat & Stam 2014: 122).

With time, videography ‘progressed’ from what was purported to be documentary or ‘fly-on-the-wall’ representations, to storytelling.

This gave film makers even more licence, and the result were movies in which Africans were presented as cannibals or the people of India portrayed as needing protection.

These storylines lent themselves well to the glorification of the colonisers as philanthropists committed to reforming or saving the savages. An excellent example is the 1937 film Wee Willie Winkie , where Colonel Williams explains to Shirley Temple that –

‘Beyond that pass, thousands of savages are waiting to sweep down and ravage India. It’s England’s duty, it’s my duty, to see that this doesn’t happen’ Colonel Williams (Shohat & Stam 2014: 126)

Lutz and Collins (2020) conducted an analysis of the photographs shown in National Geographic magazines between 1950 and 1986.

Their findings indicate that images were chosen to match an imaginary evolutionary scale based on skin colour, ranging from black / poor / strenuous physical labour / low technology / ethnic clothing / superstitious to white / wealthy / time for leisure / high technology machinery / western clothing / science.

Black people were thus portrayed engaged in strenuous physical labour, using simple tools and wearing ethnic clothing. They were also more likely to be shown conducting ‘exotic’ activities such as ritual dances.

People with bronze skin tones, on the other hand, were portrayed as less poor than those who were black and using tools that were slightly more advanced.

And finally, at the other end of the scale, white people were portrayed using state-of-the-art machinery, wearing western clothes and the trappings of wealth, and in several cases at leisure (Lutz and Collins 2020: 97-100).

The authors concluded that the selection of images sent a subliminal message to readers that ‘at one point people of color were poor, dirty, technologically backward and superstitious – and some still are. … [but] With guidance and support from the West, they can in fact overcome these problems, acquire the characteristics of civilized peoples, and take their place alongside them in the world’ (Lutz and Collins 2020: 99).

What better way of justifying Euro-American exploitation of African and Asian countries than by deploying a narrative that black and bronze people were ‘poor’ and ‘backward’ and that the Western forays into their countries would help them to modernize and improve their quality of life?

The politics of representation is thus a very important part of post-colonial studies because it examines how certain images, words and stories were used to represent non-western peoples, creating over-generalisations based on an ethnocentric cultural hierarchy of differences and values, acting as justification and camouflage for the exploitation and subjugation of the ‘Other’ in the name of progress.

Bibliography

Asad, T. (1979) ‘Anthropology and the Colonial Encounter.’ In Huizer, G., Mannheim, B. (eds), The Politics of Anthropology: From Colonialism and Sexism Toward a View from Below . De Gruyter, Inc., Berlin/Boston.

Gleach, F. (2013) ‘Notes on the Use and Abuse of Cultural Knowledge.’ In Vargas-Cetina, G, Nash, J., Igor Ayora-Diaz, S., Conklin, B.A. and Field, L.W. (eds), Anthropology and the Politics of Representation . The University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, pp. 176–190.

Lockman, Z. (2004) ‘Said’s Orientalism: A Book and Its Aftermath.’ Contending Visions of the Middle East. Cambridge University Press, pp. 182–214.

Lutz, C., and Collins, J. (2002) ‘The Color of Sex: Postwar Photographic Histories of Race and Gender.’ In Askew, K., Wilk, R. (eds), The Anthropology of Media . Blackwell Publishers, Oxford.

Said, E. (1975) ‘Shattered Myths.’ In Naseer, H. (ed.), Middle East Crucible . Medina University Press, pp. 410 – 427.

Shohat, E., Stam, R. (2014) Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media (2nd ed.). Routledge, London.

Mackay, R. (2017) ‘Nanook of the North: All the Worlds a Stage.’ Queen’s Quarterly , vol. 124, no. 2, pp. 249–258.

Vargas-Cetina, G. (2013) ‘Introduction: Anthropology and the Politics of Representation.’ In Vargas-Cetina, G, Nash, J., Igor Ayora-Diaz, S., Conklin, B.A. and Field, L.W. (eds) Anthropology and the Politics of Representation . The University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, pp. 1–15.

Claudine Cassar began her professional journey in business, earning a BSc in Business and Computing from the University of Malta, followed by an MSc in International Marketing from the University of Strathclyde and an MPhil in Innovation from Maastricht Business School. At the age of 23, she founded her first company, which she successfully sold to Deloitte 17 years later.

At 45, Claudine made a bold career shift, returning to university to pursue a degree in Anthropology. Three years later, she graduated with a BA (Hons) in Anthropological Sciences. In 2022, she published her debut book, “ The Battle for Sicily’s Soul. “

Interdisciplinary Studies Field

Visual culture, field description.

The ISF Research Field on Visual Culture incorporates the breadth, depth and complexity of visuality in shaping aesthetics and culture, and also society and politics, in history and today. It presents a broad array of visual objects (from painting to cinema, but also the built environment) encompassing the field of art history and the humanities, and extending to disciplines throughout the social sciences, from geography to anthropology. By “visual culture”, we study at once the visual display of information in all disciplines and especially visual modes of constituting regimes and orders–inquiries that include the cognitive sciences and psychology. Visual materials produce and represent social change and historical evidence, are mobilized as legal and scientific proof, used to build and forge identities, and change modes of perception generally. These are the kinds of interdisciplinary domains for the study of visual culture.

Recent ISF Senior Theses

- Comparing Love: How Romantic Relationships are Portrayed in Hollywood and Bollywood Movies, 1999-2009

- Comparing Holocaust and Memorial Sites in Germany, South Africa, Chile and the US

- Street Art in Tahrir Square

- Westernizing China Through Images: How the West Influences Chinese Culture Despite Government Controls

- The Contemporary Spanish Art Film and its Effects on Mexican Cinema

- In the Eye of the Beholder: The French Art Museum and its Publics

- Image and Projected Space of Mind: The Role of Image in the Creation of Meaning

- Shaping Young Women: The Connection Between Photography in Advertising and Rates of Bulimia

- Politicization of Aesthetics and the Fetish of the Visual: The Veiled Muslim Woman as Sociopolitical Critique in Street Art

- Bin ich ein Berliner ? Identity Construction Through the Use of Public Art and Space in Post-Reunification Berlin

- The Public Aesthetics of Social Change

- Appropriating Culture After War: The Street Art Movement in the Post-World War II United States

- Changing Society Through the Fake: How the Young Use their Imagination for Social Change

Relevant UC Berkeley Courses

- Practice of Art 119: Global Perspectives in Contemporary Art

- Rhetoric 114: Rhetoric of New Media–Visual Rhetoric

- Media Studies 101: Visual Communications

- Media Studies 170: Cultural History of Advertising

- Visual Studies 185X: Special Topics: Word and Image

- History of Art 180C: Nineteenth-Century Europe: The Invention of Avant-Gardes

- English 173: Language and Literature of Films

- Anthropology 152: Art and culture

- Rhetoric 133T: Theories of Film

- French 175A: Literature and Visual Arts

- Anthropology 138A: History and Theory of Ethnographic Film

- Sociology 160: Sociology of Culture

Bibliographical Resources

Abel, Elizabeth. 1999. “Bathroom Doors and Drinking Fountains: Jim Crow’s Racial Symbolic.” Critical Inquiry 25(3):435–81.

Adorno, Theodor W. 2001. The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture . Edited by J. M. Bernstein. London and New York: Routledge.

Adorno, Theodor, Walter Benjamin, Ernst Bloch, Bertolt Brecht, and Georg Lukacs. 2007. Aesthetics and Politics . London and New York: Verso.

Agamben, Giorgio. 2000. “Notes on Gesture,” “Marginal Notes on Commentaries on the Society of the Spectacle,” and “The Face.” Pp. 49–62, 73–102 in Means Without End: Notes on Politics . Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Auslander, Philip. 2008. Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture . 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

Bal, Mieke. 2003. “Visual Essentialism and the Object of Visual Culture.” Journal of Visual Culture 2(1):5–32.

Banet-Weiser, Sarah, Cynthia Chris, and Anthony Freitas, eds. 2007. Cable Visions: Television Beyond Broadcasting . New York: New York University Press.

Barthes, Roland. 1978. Image-Music-Text . New York: Hill and Wang.

Barthes, Roland. 2010. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography . New York: Hill and Wang.

Barthes, Roland. 2013. Mythologies . New York: Hill and Wang.

Baudrillard, Jean. 1995. Simulacra and Simulation . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Belting, Hans. 2014. An Anthropology of Images: Picture, Medium, Body . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Benjamin, Walter. 1988. “Rigorous Study of Art: On the First Volume of the Kunstwissenschaftliche Forschungen.” October 47:84–90.

Benjamin, Walter. 1999. “Little History of Photography.” Pp. 506–30 in Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, Volume 2, 1927-1934 , edited by Michael Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Benjamin, Walter. 1999. “The Formula in Which the Dialectical Structure of Film Finds Expression.” Pp. 94–95 in Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, Volume 3, 1935-1938 , edited by Howard Eiland and Michael Jennings. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Benjamin, Walter. 2009. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction . New York: Classic Books America.

Boorstin, Daniel J. 1992. The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America . New York: Vintage.

Borch-Jacobsen, Mikkel. 1991. “The Statue Man.” Pp. 43–72 in Lacan: The Absolute Master . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production . Edited by Randal Johnson. New York: Columbia University Press.

Boyle, Deirdre. 1997. Subject to Change: Guerrilla Television Revisited . New York: Oxford University Press.

Bradley, Will and Charles Esche, eds. 2008. Art and Social Change: A Critical Reader . London and New York: Tate Publishing.

Braudy, Leo and Marshall Cohen, eds. 2009. Film Theory and Criticism . 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bryson, Norman. 1986. Vision and Painting: The Logic of the Gaze . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Bryson, Norman, ed. 1988. Calligram: Essays in New Art History from France . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buckingham, David. 2000. After the Death of Childhood: Growing Up in the Age of Electronic Media . Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity Press.

Burgess, Jean and Joshua Green. 2009. YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture . Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity.

Campbell, Christopher P., Kim M. LeDuff, Cheryl D. Jenkins, and Rockell A. Brown. 2012. Race and News: Critical Perspectives . New York and London: Routledge.

Caplan, Jane, ed. 2000. Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Carson, Fiona and Claire Pajaczkowska, eds. 2001. Feminist Visual Culture . New York: Routledge.

Certeau, Michel de. 2011. “Walking in the City.” Pp. 91–110 in The Practice of Everyday Life . Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Cheetham, Mark A., Michael Ann Holly, and Keith Moxey. 2005. “Visual Studies, Historiography and Aesthetics.” Journal of Visual Culture 4(1):75–90.

Crary, Jonathan. 2001. Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture . Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Crossley, Nick. 1993. “The Politics of the Gaze: Between Foucault and Meleau-Ponty.” Human Studies 16(4):399–419.

Davies, Máire Messenger. 2013. Fake, Fact, and Fantasy: Children’s Interpretations of Television Reality . New York: Routledge.

Davis, Whitney. 2011. A General Theory of Visual Culture . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Dayan, Daniel and Elihu Katz. 1992. Media Events: The Live Broadcasting of History . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Debord, Guy. 2000. Society of The Spectacle . Detroit, MI: Black & Red.

Dewey, John. 2005. Art as Experience . New York: Perigee Trade.

Dikovitskaya, Margaret. 2006. Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Duncombe, Stephen. 2007. Dream: Re-Imagining Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy . New York: New Press.

Elkins, James, Kristi McGuire, Maureen Burns, Alicia Chester, and Joel Kuennen, eds. 2012. Theorizing Visual Studies: Writing Through the Discipline . New York: Routledge.

Ewen, Stuart. 1990. All Consuming Images: The Politics Of Style In Contemporary Culture . New York: Basic Books.

Feldman, Allen. 1997. “Violence and Vision: The Prosthetics and Aesthetics of Terror in Northern Ireland.” Public Culture 10(1):25–60.

Feldman, Allen. 2005. “On the Actuarial Gaze: From 9/11 to Abu Ghraib.” Cultural Studies 19(2):203–26.

Fernie, Eric. 1995. Art History and Its Methods: A Critical Anthology . London: Phaidon Press.

Fisherkeller, JoEllen. 2002. Growing Up with Television: Everyday Learning Among Young Adolescents . Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Fleming, Juliet. 2001. Graffiti and the Writing Arts of Early Modern England . Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1994. “Las Meninas.” Pp. 3–16 in The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences . New York: Vintage.

Foucault, Michel. 1995. “The Spectacle of the Scaffold” and “Panopticism.” Pp. 32–72 and 195–230 in Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison . New York: Vintage Books.

Frank, Gustav. 2007. “Layers of the Visual: Towards a Literary History of Visual Culture.” Pp. 76–97 in Seeing Perception , edited by Silke Horstkotte and Karin Leonhard. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Gao, Minglu. 2011. Total Modernity and the Avant-Garde in Twentieth-Century Chinese Art . Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Gillespie, Marie. 1995. Television, Ethnicity and Cultural Change . London and New York: Routledge.

Gitlin, Todd. 1981. The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Gitlin, Todd. 2000. Inside Prime Time . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Gole, Nilufer. 2002. “Islam in Public: New Visibilities and New Imaginaries.” Public Culture 14(1):173–90.

Gruzinski, Serge. 2001. Images at War: Mexico From Columbus to Blade Runner . Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Hall, Stuart, Jessica Evans, and Sean Nixon, eds. 1998. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Harvey, David. 1991. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change . Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hedges, Chris. 2010. Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle . New York: Nation Books.

Heywood, Ian and Barry Sandywell, eds. 1999. Interpreting Visual Culture: Explorations in the Hermeneutics of Vision . London and New York: Routledge.

Hilmes, Michele, ed. 2007. NBC: America’s Network . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Hite, Katherine. 2013. Politics and the Art of Commemoration: Memorials to Struggle in Latin America and Spain . New York: Routledge.

Horowitz, Noah. 2014. Art of the Deal: Contemporary Art in a Global Financial Market . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hung, Wu. 1996. The Double Screen: Medium and Representation in Chinese Painting . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Jain, Kajri. 2007. Gods in the Bazaar: The Economies of Indian Calendar Art . Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books.

Jenks, Chris, ed. 1995. Visual Culture . London and New York: Routledge.

Johnson, Galen A., ed. 1993. The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader: Philosophy and Painting . Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Kaes, Anton. 1993. “The Cold Gaze: Notes on Mobilization and Modernity.” New German Critique (59):24–26.

Kellner, Douglas. 1995. Media Culture: Cultural Studies, Identity and Politics between the Modern and the Post-Modern . London and New York: Routledge.

Kleege, Georgina. 2005. “Blindness and Visual Culture: An Eyewitness Account.” Journal of Visual Culture 4(2):179–90.

Lacan, Jacques. 1998. “Of the Gaze as Objet Petit a .” Pp. 67–122 in The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis , edited by Jacques-Alain Miller. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Lacan, Jacques. 2007. “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I.” Pp. 75–81 in Ecrits . New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Lamarche, Pierre. 2001. “Tradition, Crisis, and the Work of Art in Benjamin and Heidegger:” Philosophy Today 45(9999):37–45.

Larson, Stephanie Greco. 2005. Media & Minorities: The Politics of Race in News and Entertainment . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Latour, Bruno. 1990. “Visualization and Cognition: Drawing Things Together.” Pp. 19–68 in Representation in Scientific Activity , edited by Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lavin, Maud. 2002. Clean New World: Culture, Politics, and Graphic Design . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lemish, Dafna. 2006. Children and Television: A Global Perspective . Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Levin, Thomas Y., Ursula Frohne, and Peter Weibel, eds. 2002. CTRL [SPACE]: Rhetorics of Surveillance from Bentham to Big Brother . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lewis, Lisa. 1991. Gender Politics And MTV: Voicing the Difference . Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Manghani, Sunil. 2008. Image Critique and the Fall of the Berlin Wall . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Manovich, Lev. 2002. The Language of New Media . Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Masheck, Joseph. 1993. Building-Art: Modern Architecture under Cultural Construction . Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Massood, Paula, ed. 2008. The Spike Lee Reader . Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Mayer, Vicki. 2003. Producing Dreams, Consuming Youth: Mexican Americans and Mass Media . New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

McCarthy, Anna. 2010. The Citizen Machine: Governing by Television in 1950s America . New York: The New Press.

McLuhan, Marshall. 2008. The Mechanical Bride . Reprint edition. Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press.

McLuhan, Marshall and Quentin Fiore. 2001. The Medium Is the Massage . Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press.

McNair, Brian. 2002. Striptease Culture: Sex, Media and the Democratisation of Desire . London and New York: Routledge.

Miller, Mark Crispin. 1990. Seeing Through Movies . New York: Pantheon.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 1999. Diaspora and Visual Culture: Representing Africans and Jews . London and New York: Routledge.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 2004. Watching Babylon: The War in Iraq and Global Visual Culture . London: Routledge.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 2011. The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality . Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas, ed. 2012. The Visual Culture Reader . London and New York: Routledge.

Mitchell, W. J. T. 1987. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Mitchell, W. J. T. 1995. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Mitchell, W. J. T. 2002. “Showing Seeing: A Critique of Visual Culture.” Journal of Visual Culture 1(2):165–81.

Mitchell, W. J. T. 2006. What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Mosco, Vincent. 2009. The Political Economy of Communication . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Murray, Susan and Laurie Ouellette, eds. 2008. Reality TV: Remaking Television Culture . 2nd ed. New York: New York University Press.

Najmabadi, Afsaneh. 2004. “Gender and the Sexual Politics of Public Visibility in Iranian Modernity.” In Going Public: Feminism and the Shifting Boundaries of the Private Sphere , edited by Joan W. Scott and Debra Keates. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Nakamura, Lisa. 2007. Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet . Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Ouellette, Laurie. 1995. “Will the Revolution Be Televised? Camcorders, Activism, and Alternative Television in the 1990s.” Pp. 165–89 in Transmission: Toward a Post-Television Culture , edited by Peter d’ Agostino and David Tafler. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Rajagopal, Arvind. 2001. Politics after Television: Hindu Nationalism and the Reshaping of the Public in India . Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Rajchman, John. 1988. “Foucault’s Art of Seeing.” October (44):88–117.

Rancière, Jacques. 2009. The Future of the Image . London and New York: Verso.

Rancière, Jacques. 2011. The Emancipated Spectator . London: Verso.

Rancière, Jacques. 2013. The Politics of Aesthetics . London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Richardson, John, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis, eds. 2013. The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics . New York: Oxford University Press.

Said, Edward W. 1979. Orientalism . New York: Vintage.

Saint-Amour, Paul K. 2003. “Modernist Reconnaissance.” Modernism/modernity 10(2):349–80.

Schiller, Daniel. 2000. Digital Capitalism: Networking the Global Market System . Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Schneider, Alexandra and Birgit Mersmann. 2008. Transmission Image: Visual Translation and Cultural Agency . Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Simon, Richard Keller. 1999. Trash Culture: Popular Culture and the Great Tradition . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Smith, Marquard. 2005. “Visual Studies, or the Ossification of Thought.” Journal of Visual Culture 4(2):237–56.

Smith, Terry. 2006. The Architecture of Aftermath . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Sontag, Susan. 2001. On Photography . New York: Picador.

Spigel, Lynn. 1992. Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Straayer, Chris. 1996. Deviant Eyes, Deviant Bodies: Sexual Re-Orientation in Film and Video . New York: Columbia University Press.

Sturken, Marita and Lisa Cartwright. 2009. Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture . 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tagg, John. 1993. Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories . Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Taylor, Diana. 2012. Disappearing Acts: Spectacles of Gender and Nationalism in Argentina’s “Dirty War.” Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Treib, Marc, ed. 2009. Spatial Recall: Memory in Architecture and Landscape . New York: Routledge.

Treichler, Paula, Lisa Cartwright, and Constance Penley, eds. 1998. The Visible Woman: Imaging Technologies, Gender, and Science . New York: New York University Press.

Tryon, Chuck. 2009. Reinventing Cinema: Movies in the Age of Media Convergence . New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Turner, Fred. 2008. “Romantic Automatism: Art, Technology, and Collaborative Labor in Cold War America.” Journal of Visual Culture 7(1):5–26.

Turner, Graeme. 2013. Understanding Celebrity . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

West, Shearer. 2004. Portraiture . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wolff, Janet. 2000. “The Feminine in Modern Art: Benjamin, Simmel and the Gender of Modernity.” Theory, Culture & Society 17(6):33–53.

Zimmermann, Michael F. 2003. The Art Historian: National Traditions and Institutional Practices . Williamstown, MA: Clark Art Institute.

Zimmermann, Patricia R. 2000. States of Emergency: Documentaries, Wars, Democracy . Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Zizek, Slavoj. 1991. “The Truth Arises from Misrecognition.” Pp. 188–211 in Lacan and the Subject of Language , edited by Ellie Ragland-Sullivan and Mark Bracher. New York: Routledge.

Campus Resources

- Townsend Center for the Humanities, Course Threads Program ( http://coursethreads.berkeley.edu/course-threads/visibilities-still-image ) ( http://coursethreads.berkeley.edu/course-threads/cultural-forms-transit )

- Arts Research Center; Newsletter, events ( http://arts.berkeley.edu/ )

- Visual Resources Center; library, digital image collection ( http://ced.berkeley.edu/research/visual-resources-center/ )

- Faculty Expertise Database; search faculty research profiles by searching research interest or expertise keywords ( http://vcresearch.berkeley.edu/faculty-expertise?name=&expertise_area=la… )

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Media constructions of culture, race, and ethnicity.

- Travis L. Dixon , Travis L. Dixon Department of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Kristopher R. Weeks Kristopher R. Weeks Department of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- , and Marisa A. Smith Marisa A. Smith Department of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.502

- Published online: 23 May 2019

Racial stereotypes flood today’s mass media. Researchers investigate these stereotypes’ prevalence, from news to entertainment. Black and Latino stereotypes draw particular concern, especially because they misrepresent these racial groups. From both psychological and sociological perspectives, these misrepresentations can influence how people view their racial group as well as other groups. Furthermore, a racial group’s lack of representation can also reduce the group’s visibility to the general public. Such is the case for Native Americans and Asian Americans.

Given mass media’s widespread distribution of black and Latino stereotypes, most research on mediated racial portrayals focuses on these two groups. For instance, while black actors and actresses appear often in prime-time televisions shows, black women appear more often in situational comedies than any other genre. Also, when compared to white actors and actresses, television casts blacks in villainous or despicable roles at a higher rate. In advertising, black women often display Eurocentric features, like straight hair. On the other hand, black men are cast as unemployed, athletic, or entertainers. In sports entertainment, journalists emphasize white athletes’ intelligence and black athletes’ athleticism. In music videos, black men appear threatening and sport dark skin tones. These music videos also sexualize black women and tend to emphasize those with light skin tones. News media overrepresent black criminality and exaggerate the notion that blacks belong to the undeserving poor class. Video games tend to portray black characters as either violent outlaws or athletic.

While mass media misrepresent the black population, it tends to both misrepresent and underrepresent the Latino population. When represented in entertainment media, Latinos assume hypersexualized roles and low-occupation jobs. Both news and entertainment media overrepresent Latino criminality. News outlets also overly associate Latino immigration with crime and relate Latino immigration to economic threat. Video games rarely portray Latino characters.

Creators may create stereotypic content or fail to fairly represent racial and ethnic groups for a few reasons. First, the ethnic blame discourse in the United States may influence creators’ conscious and unconscious decision-making processes. This discourse contends that the ethnic and racial minorities are responsible for their own problems. Second, since stereotypes appeal to and are easily processed by large general audiences, the misrepresentation of racial and ethnic groups facilitates revenue generation. This article largely discusses media representations of blacks and Latinos and explains the implications of such portrayals.

- content analysis

- African American portrayals

- Latino portrayals

- ethnic blame discourse

- structural limitations and economic interests

- social identity theory

- Clark’s Stage Model of Representations

Theoretical Importance of Media Stereotypes

Media constructions of culture, race, and ethnicity remain important to study because of their potential impact on both sociological and psychological phenomena. Specifically, researchers have utilized two major theoretical constructs to understand the potential impact of stereotyping: (a) priming and cognitive accessibility (Dixon, 2006 ; Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007 ; Shrum, 2009 ), and (b) social identity and social categorization theory (Mastro, 2004 ; Mastro, Behm-Morawitz, & Kopacz, 2008 ; Tajfel & Turner, 2004 ).

Priming and Cognitive Accessibility

Priming and cognitive accessibility suggests that media consumption encourages the creation of mental shortcuts used to make relevant judgments about various social issues. For example, if a news viewer encounters someone cognitively related to a given stereotype, he or she might make a judgment about that person based on repeated exposure to the mediated stereotype. As an illustration, repeated exposure to the Muslim terrorist stereotype may lead news viewers to conclude that all Muslims are terrorists. This individual may also support punitive policies related to this stereotype, such as a Muslim ban on entry to the United States. Therefore, this cognitive linkage influences race and crime judgments (e.g., increased support for criminalizing Muslims and deporting them).

Social Identity Theory and Media Judgments

Other scholars have noted that our own identities are often tied to how people perceive their groups’ relationships to other groups. Social categorization theory argues that the higher the salience of the category to the individual, the greater the in-group favoritism one will demonstrate. Media scholars demonstrated that exposure to a mediated out-group member can increase in-group favoritism (Mastro, 2004 ). For example, researchers found that negative stories about Latino immigrants can contribute to negative out-group emotions that lead to support for harsher immigration laws (Atwell Seate & Mastro, 2016 , 2017 ).

Both the priming/cognitive accessibility approach and the social identity approach demonstrate that cultural stereotypes have significant implications for our psychology, social interactions, and policymaking. It remains extremely important for us to understand the nature and frequency of mediated racial and ethnic stereotypes to further our understanding of how these stereotypes impact viewers. This article seeks to facilitate our understanding.

Stage Model of Representation

In order to provide the reader with an introduction to this topic, this article relies on the published content-analytic literature regarding race and media. Clark’s Stage Model of Representation articulates a key organizing principle for understanding how media may construct various depictions of social groups (Clark, 1973 ; Harris, 2013 ). This model purports that race/ethnic groups move through four stages of representation in the media. In the first stage, invisibility or non-recognition , a particular race or ethnic group rarely appears on the screen at all. In the second stage, ridicule , a racial group will appear more frequently, yet will be depicted in consistently stereotypical ways. In the third stage, regulation , an ethnic group might find themselves depicted primarily in roles upholding the social order, such as judges or police officers. Finally, a particular social group reaches the respect stage in which members of the group occupy diverse and nuanced roles. Given Clark’s model, this article contends that Native Americans and Asian Americans tend to fall into the non-recognition stage (Harris, 2013 ). It follows that few empirical studies have investigated these groups because empirical content analyses have difficulty scientifically assessing phenomena that lack presence (Krippendorff, 2004 ).

Bearing in mind Clark’s stages, Latinos appear to vacillate between non-recognition and ridicule. Meanwhile, blacks move between the ridicule and regulation stages, while whites remain permanently fixed in the respect stage. In other words, in this article, our lack of deep consideration of Native Americans and Asian Americans is rooted in a lack of representation which generates few empirical studies and thus leaves us little to review. The article offers a quick overview of their portrayal and then moves on to describe the social groups that receive more media and empirical attention.

Native American and Asian American Depictions

Although severely underrepresented, there are a few consistent stereotypical portrayals that regularly emerge for these groups. In some ways, both Native American and Asian Americans are often relegated to “historical” and/or fetishized portrayals (Lipsitz, 1998 ). Native American “savage” imagery was commonly depicted in Westerns and has been updated with images of alcoholism, along with depictions of shady Native American casino owners (Strong, 2004 ). Many news images of Native Americans tend to focus on Native festivals, relegating this group to a presentation as “mysterious” spiritual people (Heider, 2000 ). Meanwhile, various school and professional team mascots embody the savage Native American Warrior trope (Strong, 2004 ).

Asian Americans overall have often been associated with being the model minority (Harris, 2009 ; Josey, Hurley, Hefner, & Dixon, 2009 ). They typically represent “successful” non-whites. Specifically, media depictions associate Asian American men with technology and Asian American women with sexual submissiveness (Harris & Barlett, 2009 ; Schug, Alt, Lu, Gosin, & Fay, 2017 ).

Overall, scholars know very little about how either of these groups are regularly portrayed based on empirical research, although novelists and critical scholars have offered useful critiques (Wilson, Gutiérrez, & Chao, 2003 ). Hopefully, future quantitative content analyses will further delineate the nature of Native American and Asian American portrayals. Consider the discussion about entertainment, news, and digital imagery of blacks, Latinos, and whites presented in the next section.

Entertainment Constructions of Race, Culture, and Ethnicity

Entertainment media receives a great deal of consideration, given that Americans spend much of their time using media for entertainment purposes (Harris, 2013 ; Sparks, 2016 ). This section begins with an analysis of black portrayals, then moves on to Latino portrayals to understand the prevalence of stereotyping . When appropriate, black and Latino representations are compared to white ones. Two measures describe a group’s representation: (a) the numerical presence of a particular racial/ethnic group, and (b) the distribution of roles or stereotypes regarding each group. When researchers have often engaged in examinations of race they typically begin by comparing African American portrayals to white portrayals (Entman & Rojecki, 2000 ). As a result, there is a substantial amount of research on black portrayals.

Black Entertainment Television Imagery

Overall, a number of studies have found that blacks receive representation in prime-time television at parity to their actual proportion in the US population with their proportion ranging from 10% to 17% of prime-time characters (Mastro & Greenberg, 2000 ; Signorielli, 2009 ; Tukachinsky, Mastro, & Yarchi, 2015 ). African Americans currently compose approximately 13% of the US population (US Census Bureau, 2018 ). When considering the type of characters (e.g., major or minor) portrayed by this group, the majority of black (61%) cast members land roles as major characters (Monk-Turner, Heiserman, Johnson, Cotton, & Jackson, 2010 ). Black women also fare well in these representations, accounting for 73% of black appearances on prime-time television (Monk-Turner et al., 2010 ).

However, recent content analyses reveal an instability in black prime-time television representation over the last few decades. Tukachinsky et al. ( 2015 ) found that the prevalence of black characters dropped in 1993 and remain diminished compared to previous decades. Similarly, Signorielli ( 2009 ) found a significant linear decrease in the proportion of black representation from 2001 (17%) to 2008 (12%). Signorielli ( 2009 ) attributes this decrease in black representation to the decrease in situation comedy programming. Indeed, African Americans appear most frequently in situation comedies. Sixty percent of black women featured in prime-time television are cast in situation comedies, and 25% of black male prime-time portrayals occur in situation comedies (Signorielli, 2009 ). However, between 2001 and 2008 , situational comedies decreased, while action and crime programs increased.