How Your Thinking Affects Your Brain Chemistry

Your thoughts matter because they change how your brain and body function..

Posted April 10, 2023 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

- What Is Dopamine?

- Find a therapist near me

- Your thoughts are transmitted via neurotransmitters and other neurochemicals.

- You can proactively release various feel-good neurotransmitters in your brain based on what you think about.

- Your brain chemistry changes physical structures in your brain and body.

Most people don’t think about the fact that their thoughts are chemical, and even less so about how to use their thoughts to manage their brain chemistry. Your brain chemistry is your mental health. If it’s optimally balanced, you feel good and function well. If it’s unbalanced in some way, you start to feel not like yourself, and if it stays that way for too long, you can end up with serious mental health disorders.

The relationship between our thoughts and brain chemistry is complex and multifaceted. There are many different factors that can influence this relationship, including our genetics , environment, and life experiences. The key thing to understand, however, is that thoughts are transmitted via neurotransmitters and other neurochemicals in our brain. These neurochemicals are also responsible for your emotions.

One of the most well-known neurotransmitters is dopamine . Dopamine is often referred to as the “feel-good” neurotransmitter because it is associated with pleasure and reward. When you think about something pleasurable, such as eating a delicious meal or listening to your favorite music, your brain releases dopamine.

Another well-known neurotransmitter, oxytocin , is sometimes called the “love hormone” because it is released during social bonding activities, such as hugging or cuddling. This can create feelings of closeness and connection with others. Just thinking about a loved one releases oxytocin in the brain.

Your thoughts can also influence the release of stress hormones , such as cortisol. When you experience stress, your body releases cortisol as part of the “fight or flight” response. This can be helpful in the short term if you’re responding to a perceived threat. However, if you experience chronic stress, and you regularly think about stressful situations, your body may release too much cortisol, which can have negative effects on your physical and mental health.

Thinking and brain chemistry is a two-way street. While your thoughts influence your brain chemistry, your brain chemistry also influences your thoughts. For example, if you’re thinking about things that make you feel anxious, your brain releases more cortisol, which can make you feel even more anxious. This creates a negative feedback loop that can be hard to break.

Your brain’s chemistry not only affects how you feel but also changes the actual physical structures of your brain and body. Research has shown that over time, changing what you think can change the size of certain regions of your brain. Research has also shown that the neurochemicals released via your thinking have the power to influence physical symptoms in your body.

For example, the placebo effect often occurs in medical research when someone thinks they are getting a certain treatment for an illness, and they are instead given a sham or fake version of the treatment. These people improve anyway because they think they are getting the real treatment. Placebos have been shown to improve physical symptoms of depression , anxiety , pain, coughs, erectile dysfunction, IBS, Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy, to name a few. On the other hand, if an individual does not think the drug will work, or expects there to be side effects, the placebo can create negative outcomes. When this is the case, the placebo is instead called a nocebo.

The relationship between the mind and body is complex but the two cannot be separated. Your thinking directly impacts your mental and physical well-being via your brain chemistry. If you’d like to take charge of this process naturally and optimize your brain’s ability to function in a healthy way, there are a number of strategies you can try:

1. Practice mindfulness and mindful redirecting

One of the most effective ways to regulate your brain's chemistry is to practice mindfulness . Mindfulness involves focusing your attention on the present moment, without judgment or distraction. By practicing mindfulness regularly, you can train your brain to become more aware of your thoughts and emotions.

With awareness, you can choose to redirect your thoughts. When you choose to move your thoughts away from things that don’t feel good and instead focus on things that are rewarding and elicit a positive emotion , you are proactively deciding which neurochemicals get released in your brain.

2. Exercise regularly

Regular exercise has been shown to have a positive impact on brain chemistry by increasing the production of neurotransmitters, such as endorphins, dopamine, and serotonin. These neurotransmitters play a key role in regulating mood, motivation , and attention.

3. Get enough sleep

Good sleep is essential for maintaining healthy brain chemistry. During sleep, the brain flushes out toxins and repairs itself, which helps to maintain the balance of neurotransmitters and other chemicals in the brain. Research has shown that sleep deprivation can have a negative impact on brain chemistry, leading to mood disorders, anxiety, and other cognitive impairments.

4. Get the right nutrition

What you eat becomes the building blocks for the neurochemicals used by your brain. At least 90% of the serotonin in your body is produced in your gut microbiome . Recent research is linking food to disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and depression. While there is a wide range of conflicting information out there on what good nutrition is, the one diet that has been examined and shown to improve brain functioning using the gold standard of a randomized clinical trial is the Mediterranean diet. Lots of fruits and vegetables, healthy fats such as avocados and olive oils, and lean poultry and fish. Get rid of processed carbohydrates, sugar, fried food, and alcohol .

5. Practice gratitude

When you’re thinking about what you’re grateful for, your thoughts are intentionally being directed toward things you know make you feel good. Practicing gratitude has been shown to have a positive impact on brain chemistry by increasing the production of dopamine and serotonin, two neurotransmitters that play a key role in regulating mood and motivation.

How your brain functions plays a very big role in your quality of life. Learning to regulate your thoughts and behavior in a way that optimizes your brain’s chemistry is well worth the effort.

Jennice Vilhauer, Ph.D. , is the Director of Emory University’s Adult Outpatient Psychotherapy Program in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science in the School of Medicine.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

When we fall prey to perfectionism, we think we’re honorably aspiring to be our very best, but often we’re really just setting ourselves up for failure, as perfection is impossible and its pursuit inevitably backfires.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Partnerships

Critical thinking

Effective lifelong learning

Executive summary

- One of the most striking characteristics of the XX and XXI centuries is the “exponential growth” of knowledge generated in any discipline, which is available to most of the world’s citizens.

- As it is no longer possible to comprehend all the information available, in relation to disciplines or even subdisciplines, education should promote the acquisition of learning abilities related to modes of thought rather than solely the accumulation or memorization of, in many cases, information that may be only infrequently useful.

- One mode of thought, reflective thinking or critical thinking, is a metacognitive process—a set of habituated intellectual resources put purposefully into action—that enables a deeper understanding of new information. It also provides a secure foundation for more effective problem-solving, decision-making, and appropriate argumentation of ideas and opinions.

- The global output of teaching critical thinking is adding new competences to everyone’s basic capacities for greater cognitive development and freedom.

“… Nothing better for the mental development of the child and the adolescent than to teach them superior ways of learning that complement, continue, rectify and elevate the spontaneous ways. Originality is a precious heritage that the pedagogue must not only guard, but lead, in the domain of values, to its maximum expression. And with superior ways of learning, culture and originality grow in parallel. To teach superior ways of learning is to add to the native powers, new powers for greater independence of the spirit in all its manifestations. It is teaching to move only upwards…Teaching to observe well, to think well, to feel good, to express oneself well and to act well is what, in sum, every pedagogical doctrine, new or old, revolutionary or conservative, of now and forever, is materialized.” (Clemente Estable, 1947 1 ).

Introduction and historical background

The brain is the organ that allows us to think. This confronts us with a philosophical challenge that has been accompanying human civilization for more than 2,500 years: H ow can the brain help us to understand how the brain enables us to understand? 2

Ancient Greek philosophers have already questioned themselves about the source of knowledge and cognitive functions and hypothesized about the fundamental role of the brain, in opposition to the heart or even the air or fire 3-6 . The Socratic method, involving the introspective scrutiny of thought guided by questioning, paved the long-lasting way to contemporary approaches and conceptions about “good thinking,” also called “reflective thinking,” 7 and more recently, “critical thinking” 8 .

As in any area of knowledge, most of the accumulated content—which is vast and always evolving—is nowadays accessible to everyone who has access to the internet. Thus, it can be argued that educational efforts should concentrate on improving the next generation’s modes of thinking. It is desirable to promote engagement with knowledge rather than transmitting the requirement of accumulating data—usually disposable information—through mastery or memorization 9 .

Critical thinking is a fundamental pillar in every field of learning within disciplines as diverse as science, technology, engineering, and mathematics as well as the humanities including literature, history, art, and philosophy 5,9,10 .

No matter the discipline, critical thinking pursues some end or purpose, such as answering a question, deciding, solving a problem, devising a plan, or carrying out a project to face present and future challenges 11 . Hence, it is also applicable to everyday life and is desirable for a plural society with citizenship literacy and scientific competence for participation in diverse situations, including dilemmas of scientific tenor 7,12 .

In spite of the explicit valuing of critical thinking, and iterative efforts to promote its effective incorporation in the curricula at different levels of education of science, humanities, and education itself, difficulties for deeper grasping of critical thinking and challenges for its fruitful integration in educational curricula persist 13,14 . Such difficulty is in part caused by a lack of consensus regarding a definition of critical thinking.

Defining critical thinking

Critical thinking is a mental process 11 like creative thinking, intuition, and emotional reasoning, all of which are important to the psychological life of an individual 10 . It pertains to a family of forms of higher order thinking, including problem-solving, creative thinking, and decision-making 15 . However, there is not a single or direct definition of critical thinking, probably reflecting the emphasis made on different features or aspects by several authors from diverse disciplines as education, philosophy, and neurosciences 7,10,16-18 .

Some of the distinguishing features of critical thinking and critical thinkers are ( 7, 11, 12, 16, 19, 20 ; see Figure 1):

Figure 1. Diagram of the principal features of critical thinking, including some of the necessary cognitive functions and intellectual resources. The arrows indicate the main mechanisms of modulation: top-down, involving the effect of upper on lower level intellectual resources (for example, the effect of metacognition on motivation that in turn affects perception), and bottom-up (such as the influence of self-analysis and habituation on self-regulation and metacognition).

- Critical thinkers pursue some end or purpose such as answering a question, making a decision, solving a problem, devising a plan, or carrying out a project to cope with present or future challenges.

- Accordingly, critical thinking is purposively put into action and driven by .

- As a result of this top-down influence, critical thinking is an attitude which does not occur spontaneously.

- Critical thinking also involves the knowledge, acquisition, and improvement of a spectrum of intellectual resources such as: – methods of logical inquiry; – information literacy to gather significant information about the problem and the context for embracing comprehensive background knowledge; – operational knowledge of processing skills for generation of concepts and beliefs: analysis, evaluation, inference, reflective judgment.

- To accomplish these intellectual resources, critical thinkers need to put into action the most basic cognitive functions such as perception, motor coordination and action, sensory-motor coordination, language perception and production, memory, and decision-making.

- Critical thinkers apply these procedures and methods in a systematic and reasonable way.

- As a result, critical thinking is not an immediate cognitive event but a process .

- The main outcome of critical thinking is a reflective, ordered, causal flow of ideas .

- Critical thinkers self-analyze and self-assess the mode of thinking.

- Consequently, critical thinking is a metacognitive process .

- Self-evaluation launches a bottom-up process for modulation and improvement of critical thinking, enabling greater adaptability to different situations.

- Thus, critical thinking also requires training and habituation .

- As a global outcome, critical thinking, as a metacognitive process, also refines self-regulation (i.e., the ability to understand and control our learning environments) 20 .

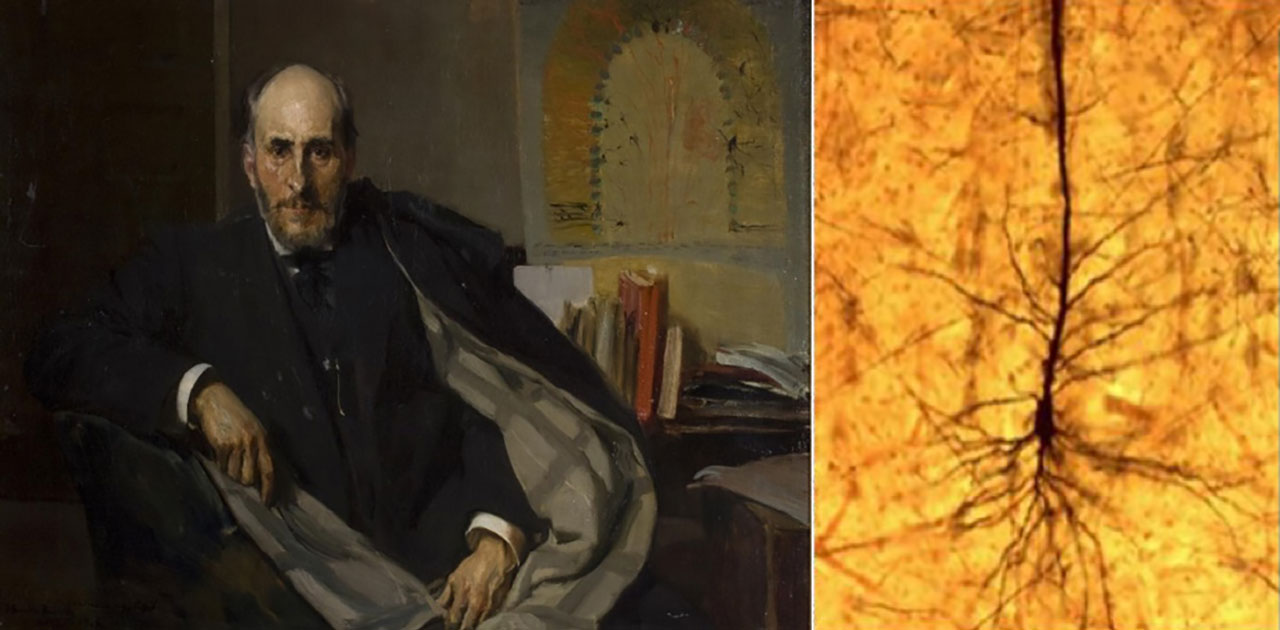

In sum, critical thinking is a purposeful, intellectually demanding, disciplined, plastic, and trainable mode of thinking in which motivation, self-analysis, and self-regulation play key roles. Several of these aspects were stressed by Santiago Ramón y Cajal (see Figure 2A). Cajal—founder of modern neuroscience and Nobel Prize of Medicine in 1906—hypothesized about the role of brain plasticity, metanalysis habituation, and self-regulation for the acquisition of knowledge about objects or problems: “When one thinks about the curious property that man possesses of changing and refining his mental activity in relation to a profoundly meditated object or problem, one cannot but suspect that the brain, thanks to its plasticity, evolves anatomically and dynamically, adapting progressively to the subject. This adequate and specific organization acquired by the nerve cells eventually produces what I would call professional talent or adaptation, and has its own will, that is, the energetic resolution to adapt our understanding to the nature of the matter.” 20

Figure 2. Left: Portrait of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Oil painted by the Spanish Postimpressionist painter Joaquín Sorolla in 1906, the year Cajal received the Nobel Prize in Medicine 21 . Right: Microphotography of an original preparation of Cajal showing a pyramidal neuron of the human brain cortex. Staining: Golgi staining. Original handwritten label: Pyramid. Boy 22 .

Neural basis of critical thinking

Figure 3. Mapping of cognitive functions. The diagram superposed on the lateral view of the human brain indicates the location of distributed neural assemblies activated in relation to cognitive functions. Note that the indicated cognitive functions are involved in the same or successive phases of critical thinking. (Modified from ref. 26 ).

The cognitive functions and intellectual resources involved in critical thinking are emergent properties of the human brain’s structure and function which depend on the activity of its building blocks, the neurons (see Figure 2B). Neurons are specialized cells which are almost equal in number to nonneuronal cells in human brains. Of the total amount of 86 billon neurons, 19% form the cerebral cortex and 78% the cerebellum 23 . Neurons are interconnected and intercommunicate through specialized junctions called synapses, of which there are about 0,15 quadrillion in the cerebral cortex 24 and more than 3 trillion in the cerebellar cortex (considering the total number of Purkinje cells and the total amount of synapses/Purkinje cell 25 ). These stellar numbers help us imagine the density of the entangled brain web. This web is not fully active at any time. Instead, distributed groups of neurons or “distributed neural assemblies” are more active at certain topographies when particular cognitive functions are taking place 26 . Considering the spectrum of cognitive functions involved in the process of critical thinking, it will increase activation in much of the brain cortex (see Figure 3).

Teaching critical thinking

“It is not enough to know how we learn, we must know how to teach.” (Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2010 27 ).

Teachers have the invaluable potential power of fostering knowledge in the next generations of students and citizens. However, this power is expressed when teachers, instead of teaching what they know—and hence limiting students’ knowledge to their own—teach students to think critically and so open up the possibility that students’ knowledge will expand beyond the borders of the teachers’ own knowledge 28 . Thus, it is important to be aware that—similar to electrical circuits and Ohm’s law—the wealth and depth of students’ knowledge that is achieved or expressed depends not only on the energy or effort that students put in the task but also their own (internal) resistance as well as teachers’ (external) resistance. This metaphor exemplifies that the expected outcomes of education may be better achieved if teachers are familiar with the foundations of critical thinking, better appreciate its worth, and themselves become proficient at thinking critically, particularly in relation to their professional activity.

Now more than ever it is possible for teachers to build a framework to improve the teaching and learning of critical thinking in the classroom 29 thanks to a wealth of information and guidelines resulting from contributions of diverse disciplines since the renewed interest in critical thinking and its promotion in education pioneered by Dewey 7 at the dawn of the 20th century. According to Boisvert (1999 28 ), up to the 1980s, education focused on the abilities of critical thinking as goals to achieve.

Since then, a growing movement of critical thinking has been characterized by iterative attempts to define critical thinking, as well as by instructing teachers about this process and how to teach it. In parallel, several tools for assessment have been created 11, 30, 31, 32, 33 .

Nevertheless, the long-lasting aim has not been achieved. In trying to envisage more fruitful strategies, it is worth noting the difficulty of transmitting critical thinking as just a skill that can be trained without considering the context. On the contrary, the domain of knowledge and the development of critical thinking should be considered in parallel as related intellectual resources—as pointed out by Willimham 33 . It is worth pointing out that, parallel to the critical thinking movement, there has been an increasing simultaneous interest in the neural bases of critical thinking, leading to the emergence 5,34 of “educational neuroscience” 35 and “brain, mind and education” 36 . These interdisciplinary fields have been elucidating the fundamental mechanisms involved in critical thinking as well as the role of factors that impact on this ability. This, along with the tight collaboration between scientists and teachers, is forging a new (Machado) path or bridge over the “gulf” between these fields 35 .

References/Suggested Readings & Notes

- Estable, C. 1947. Pedagogía de presión normativa y pedagogía de la personalidad y de la vocación. An. Ateneo Urug., 2ª ed., 1, 155-156. http://www.periodicas.edu.uy/Anales_Ateneo_Uruguay/pdfs/Anales_Ateneo_Uruguay_2a_epoca_n2.pdf

- Shepherd, G, M. 1994. Neurobiology, 3rd edn , Oxford University Press.

- Cope, E. M. 1875. Plato’s Phaedo, Literally translated , Cambridge University Press.

- Adams, L. L. D. 1849. Hippocrates Translated from the Greek with a preliminary discourse and annotations. The Sydenham Society.

- Vieira, R. M., Tenreiro-Vieira, C. & Martins, I. P. Critical thinking: conceptual clarification and its importance in science education. Science Education International 22,43–54 (2011).

- Panegyres, K. P. & Panegyres, P. K. The ancient Greek discovery of the nervous system: Alcmaeon, Praxagoras and Herophilus. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 29, 21–24 (2016).

- Dewey, J. How we think. The Problem of Training Thought 14 (1910). doi:10.1037/10903-000

- Glaser, E. M. (1941). An experiment in the development of critical thinking . New York: Columbia University Teachers College.

- Edmonds, Michael, et al. History & Critical Thinking: A Handbook for Using Historical Documents to Improve Students’ Thinking Skills in the Secondary Grades. Wisconsin Historical Society, 2005. http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/pdfs/lessons/EDU-History-and-Critical-Thinking-Handbook.pdf

- Mulnix, J. W. Thinking critically about critical thinking. Educational Philosophy and Theory 44, 464–479 (2012).

- Bailin, S., Case, R., Coombs, J. R. & Daniels, L. B. Conceptualizing critical thinking. Journal of Curriculum Studies 31, 285–302 (1999).

- Dwyer, C. P., Hogan, M. J. & Stewart, I. An integrated critical thinking framework for the 21st century. Thinking Skills and Creativity 12, 43–52 (2014).

- Paul, R. The state of critical thinking today. New Directions for Community Colleges 130, 27–39 (2005).

- Lloyd, M. & Bahr, N. Thinking critically about critical thinking in higher education. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning 4, 1–16 (2010).

- Rudd, R. D. Defining critical thinking. Techniques. 46 (2007).

- Siegel, H. (1988) . Educating reason: Rationality, critical thinking, and education . Philosophy of education research library. Routledge Inc.

- Siegel, H. in International Encyclopedia of Education 141–145 (Elsevier Ltd, 2010). doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.00582-0

- Bailin, S. Critical thinking and science education. Science & Education (2002) 11: 361. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016042608621

- Facione, P. A. Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction. California Academic Press 1–19 (1990). doi:10.1080/00324728.2012.723893

- Schraw, G., Crippen, K. J., & Hartley, K. (2006). Promoting self-regulation in science education: metacognition as part of a broader perspective on learning. Research in Science Education 36(1–2), 111–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-005-3917-8

- Ramon y Cajal, S. Recuerdos de mi vida . Juan Fernández Santarén, Barcelona. Editorial Crítica ( 1899); Of Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32562506).

- From: http://www.montelouro.es/Cajal.html.

- Herculano-Houzel, S. The human brain in numbers: a linearly scaled-up primate brain. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 3, (2009).

- Pakkenberg, B. et al. Aging and the human neocortex. Experimental Gerontology 38, 95–99 (2003).

- Nairn JG, Bedi KS, Mayhew TM, Campbell LF. On the number of Purkinje cells in the human cerebellum: unbiased estimates obtained by using the “fractionator”. J Comp Neurol. 290(4), 527-32 (1989).

- Pulvermüller, F., Garagnani, M. & Wennekers, T. Thinking in circuits: toward neurobiological explanation in cognitive neuroscience. Biological Cybernetics 108, 573–593 (2014).

- Tokuhama-Espinosa, T. The New Science of Teaching and Learning: Using the Best of Mind, Brain, and Education Science in the Classroom. Teachers College Press (2010).

- Chavan, A. A. & Khandagale V. S. Development of critical thinking skill programme for the student teachers of diploma in teacher education colleges. Issues Ideas Educ. http://dspace.chitkara.edu.in/xmlui/handle/1/159.

- Paul, R. & Elder, L. Guide for educators to critical thinking competency standards: standards, principles, performance indicators, and outcomes with a critical thinking master rubric. Foundation for Critical Thinking. (2007).

- Paul, R. W. Critical Thinking: What Every Person Needs to Survive in a Rapidly Changing World. Foundation for Critical Thinking. (2000). Retrieved from http://assets00.grou.ps/0F2E3C/wysiwyg_files/FilesModule/criticalthinkingandwriting/20090921185639-uxlhmlnvedpammxrz/CritThink1.pdf

- Paul, R. W., Elder, L. & Bartell, T. California Teacher Preparation for Instruction in Critical Thinking: Research Findings and Policy Recommendations. (1997). Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1001.1087&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Vieira, R. M. Formação continuada de professores do 1.º e 2.º ciclos do Ensino Básico para uma educação em Ciências com orientação CTS/PC. Tese de doutoramento (não publicada), Universidade de Aveiro. (2003). Retrieved from: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/374/37419205.pdf

- Willingham, D. T. Critical Thinking: Why Is It So Hard to Teach? American Educator 31, 8-19. (2007). Retrieved from http://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Crit_Thinking.pdf

- Zadina, J. N. The emerging role of educational neuroscience in education reform. Psicología Educativa 21,71–77 (2015).

- Goswami, U. Neurociencia y Educación: ¿podemos ir de la investigación básica a su aplicación? Un posible marco de referencia desde la investigación en dislexia. Psicologia Educativa 21, 97–105 (2015).

- Schwartz, M. Mind, brain and education: a decade of evolution. Mind, Brain, and Education 9, 64–71 (2015).

IMAGES