How Does Research Help the Community

Table of Contents

Research help the community by providing valuable insights that can inform evidence-based policies and interventions, fostering sustainable development and positive change. Research is a powerful tool that not only expands the horizons of human knowledge but also plays a pivotal role in shaping and transforming communities. In this article, we will explore the profound impact of research on communities and delve into the ways it contributes to the betterment of society. From understanding the community’s needs to addressing social and environmental challenges, research stands as a cornerstone for progress.

Understanding the Community

To understand the importance of research in community development, one must first grasp the complexities and dynamics of the community itself. A community isn’t just a place on a map; it’s like a woven fabric made up of different parts, like cultures, economies, and how people interact. Research in community psychology allows us to delve deep into these threads, unraveling the unique challenges, strengths, and aspirations that define a particular community.

By employing methods like surveys, interviews, and observational studies, researchers can gather valuable insights into the collective mindset of a community. This understanding forms the basis for tailoring interventions and initiatives that are not only effective but resonate with the community’s values.

Research helps the community in the following ways:

i. Enhancing Healthcare and Well-being

Research contributes significantly to the enhancement of healthcare and well-being within a community. By identifying prevalent health issues, assessing healthcare accessibility, and developing targeted interventions, research plays a pivotal role in improving the overall health of community members. For instance, a community facing a high prevalence of a particular disease can utilize research findings to implement preventive measures and ensure timely medical interventions.

ii. Advancing Education and Learning

Research in education is instrumental in advancing learning outcomes within a community. By conducting studies on educational methodologies, literacy rates, and learning environments, researchers can provide valuable insights that inform educational policies and practices. This, in turn, enhances the quality of education and equips community members with the necessary skills for personal and collective development.

iii. Promoting Economic Growth and Development

Economic growth and development are intricately linked to research within a community. Through studies on economic trends, employment patterns, and market dynamics, researchers can offer valuable information that guides economic policies and initiatives. For instance, a community aiming for sustainable economic development can use research findings to identify key sectors for investment, develop entrepreneurship programs, and attract businesses that align with the community’s goals.

iv. Addressing Social and Environmental Challenges

Communities often face numerous of social and environmental challenges, ranging from social inequality to climate change. Research serves as a powerful tool for understanding the complexities of these challenges and devising effective strategies for mitigation and adaptation.

For instance, in the face of social issues such as discrimination or inequality, research can uncover the underlying causes and propose evidence-based solutions. This might involve implementing community programs, raising awareness, or advocating for policy changes that address systemic issues. Similarly, in the realm of environmental challenges, research helps communities understand their ecological footprint, identify sources of pollution, and develop sustainable practices to preserve natural resources.

How Research Will Benefit the Community?

The benefits of research to a community are multi-dimensional. Firstly, it acts as a guiding light for policymakers and community leaders. Armed with evidence-based insights, decision-makers can formulate policies that are not only relevant but also responsive to the genuine needs of the community. This not only ensures the efficient allocation of resources but also fosters a sense of trust and collaboration between the community and its leaders. Additionally, research improves the quality of life for residents by identifying and addressing key factors that impact well-being, thus contributing to the overall health and prosperity of the community. Furthermore, research help the community by empowering residents with knowledge, enabling them to actively participate in decision-making processes and contribute to the overall well-being and development of their community.

Moreover, research acts as a catalyst for innovation and progress. It provides a platform for identifying emerging trends, understanding shifting demographics, and predicting future challenges. For instance, a community facing an aging population can utilize research findings to develop targeted healthcare programs, ensuring the well-being of its residents.

How Do Research Studies Help the Society?

Research studies are the foundation of societal progress, offering a systematic approach to understanding complex issues. They serve as a bridge between theoretical knowledge and practical solutions, transforming ideas into actionable strategies. In the context of communities, research studies offer a lens through which we can analyze and interpret the challenges and opportunities that shape their trajectory.

One of the key ways research studies contribute to society is by fostering a culture of continuous learning. By examining the outcomes of different interventions and policies, communities can adapt and refine their approaches, fostering an environment of resilience and adaptability.

What Is the Impact of Research in the Community?

The impact of research in a community is far-reaching, touching various aspects of daily life. One notable impact is the enhancement of healthcare and well-being. Research enables the identification of prevalent health issues, the assessment of healthcare accessibility, and the development of targeted interventions.

In addition to healthcare, research contributes significantly to the advancement of education and learning within a community. Studies on educational methodologies, literacy rates, and learning outcomes empower educators and policymakers to implement evidence-based strategies that improve the overall quality of education.

How Can Research Help the Community in Solving Such Problems?

Research not only identifies problems but also offers practical solutions. By adopting a problem-solving approach, communities can leverage research findings to devise effective strategies for overcoming challenges. For instance, in a community grappling with unemployment, research can pinpoint the root causes and inform the creation of job training programs, stimulating economic growth.

Furthermore, research facilitates collaboration between communities and external entities such as governmental organizations, NGOs, and academic institutions. This collaborative approach ensures a holistic understanding of problems and encourages the pooling of resources and expertise for comprehensive solutions.

How to Do Research in the Community?

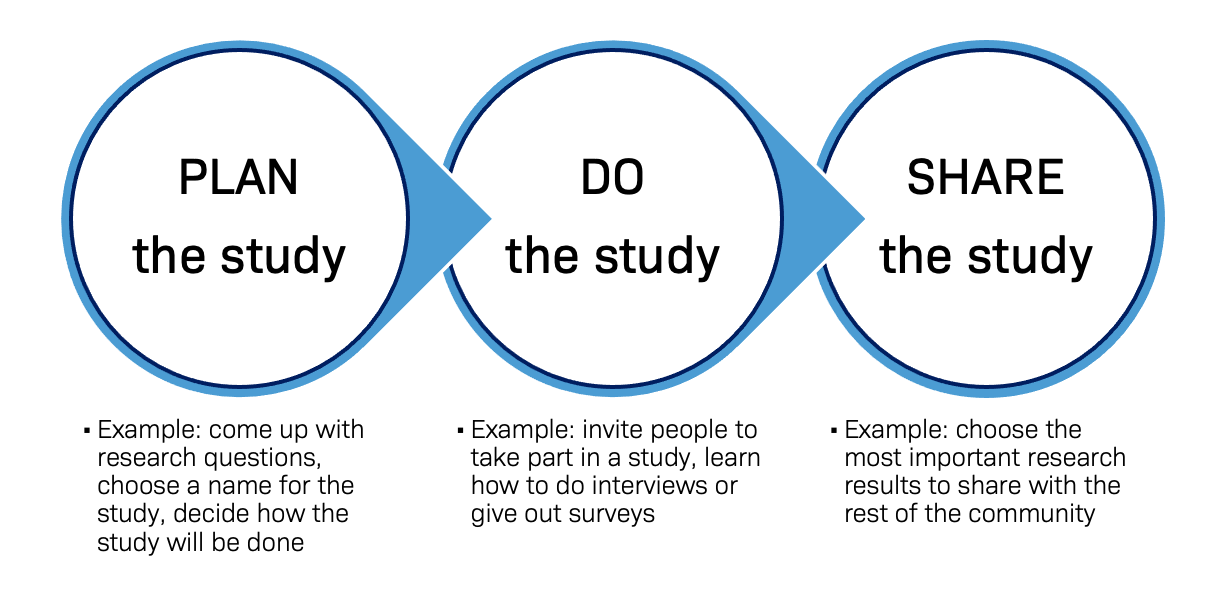

Conducting research in a community requires a thoughtful and ethical approach. Researchers must engage with the community members, respecting their perspectives and involving them in the research process. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is an approach that emphasizes collaboration between researchers and community members, ensuring that the research is not only scientifically rigorous but also culturally sensitive.

Additionally, employing diverse research methods such as qualitative and quantitative approaches provides a comprehensive understanding of the community. Surveys, focus group discussions, and participatory observations are some of the tools that researchers can use to gather rich and varied data.

5 Purposes of Research

1. understanding:.

Involves gaining deep insights into the dynamics of the community.

2. Exploration:

Encompasses delving into unexplored realms of knowledge to uncover new perspectives and possibilities.

3. Description:

Focuses on accurately portraying the community, providing a detailed and realistic snapshot of its characteristics.

4. Explanation:

Seeks to comprehend the underlying causes and relationships within the community, unraveling the complexities that shape its dynamics.

5. Application:

Involves utilizing research findings as a practical tool for positive change within the community.

Importance of Research in Community

Here are the following 5 importance of research in the community:

1. Guiding Force:

Research serves as a guiding force, aiding communities in navigating the complexities of social, economic, and environmental challenges.

2. Informed Decision-Making:

The importance of research lies in its role as a catalyst for informed decision-making within communities, ensuring that choices are grounded in evidence and data.

3. Adaptability:

Research empowers communities to adapt to changing circumstances, providing the knowledge necessary to navigate evolving landscapes effectively.

4. Envisioning the Future:

It enables communities to envision a future that aligns with their collective aspirations, shaping a trajectory for purposeful and sustainable development.

5. Foundation for Growth:

Research establishes a robust foundation for community growth by offering insights that contribute to comprehensive and responsive development strategies.

In conclusion, the role of research in community development is indispensable. From understanding the intricate dynamics of a community to addressing social, economic, and environmental challenges, research serves as a guiding force for positive change. The benefits of research to a community are vast, spanning healthcare, education, economic development, and the overall well-being of community members.

In essence, research help the community in solving its problems by providing evidence-based strategies, fostering collaboration, and offering a systematic approach to understanding complex issues. It serves as a guiding force, supporting informed decision-making, adaptability, and envisioning a future aligned with collective aspirations.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Understanding Health Disparities

- What is Research?

- Importance of Diversity

- Final Thoughts

- Do You Know?

- Learning from the Past

- Protections Today

- Should I Participate?

- What is Informed Consent?

- Knowledge is Power

- What Can Research Do In Your Community?

- Getting Involved

- Being An Informed Consumer

- Being A Participant

What Can Research Do In Your Community?

Research takes place in many different settings.

Some research is done in clinical settings like a hospital or doctor’s office. Some may take place on a university campus. Other research happens in community settings where community members themselves may play a variety of roles in the research. This unit will present ideas about how you can get involved in research and work with researchers to improve the health and well-being of your community.

"It's going to take a community to really deal with these kinds of issues." - Dr. John Ruffin, Founding Director of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD)

Below are examples of how communities and researchers have been able to work together in the United States.

u3-slide1.jpg

u3-slide2.jpg

u3-slide3.jpg

u3-slide4.jpg

u3-slide5.jpg

King County Healthy Homes, Seattle, WA

The King County Healthy Homes project was an intervention research project to help prevent asthma and encourage healthy indoor environments in Seattle.

The indoor home environment presents a range of health risks, including asthma triggers and exposures to toxics such as lead, pesticides, and volatile organics. Minority and low income populations are at increased risk for many of these exposures and children are most sensitive to their effects. Asthma is an important health consequence of these exposures, and its incidence and mortality appear to be steadily increasing, especially among low-income children.

The Seattle-King County Healthy Homes Project addressed these concerns. Paraprofessional Community Home Environmental Specialists (CHES) provided a comprehensive package of educational materials to reduce the total exposure burden of indoor environmental health risks. CHES conducted an initial home environmental assessment in low-income households with asthmatic children age 4-12. The home environmental specialists offered education and social support, encouraged behavior changes, provided materials to reduce exposures (bedding covers, vacuums, door mats, cleaning kits). This initial assessment was followed by five to nine visits over the next 12 months in which CHES worked with tenants, offering continued education and social support.

Community participation was an important component of this project. The project was developed by a partnership of community agencies, a tenant’s union, an environmental justice organization, the local health department, the CDC-sponsored Seattle Partners for Healthy Communities and the University of Washington. Primary funding was provided by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences with additional support from the Nesholm Foundation, the Seattle Foundation, and the Seattle-King County Department of Public Health. The project ran from 1997-2005 and found that the homes receiving the educational materials and supports had lower rates of development and severity of asthma in their children and higher awareness of how to prevent asthma.

Source http://www.kingcounty.gov/healthservices/health/partnerships/sphc/projects.aspx

- King County Homes Project

- Healthy Mothers on the Move

- Vietnamese-American Cervical Cancer Screening

- Weact Northern Manhattan Food Survey

Questions to think about and discuss when reviewing the four examples.

- Who did the study aim to help?

- What problem was the study trying to address?

- When did the study take place?

- How did researchers and community groups work together?

- How did the study make a difference in the community?

Healthy Mothers on the Move, Detroit, MI

The Healthy Mothers on the Move project aimed to demonstrate the effectiveness of a social support healthy lifestyle intervention designed to reduce risk factors for Type 2 diabetes among pregnant and postpartum women. The project worked with Latina and African American pregnant and post-partum women in Detroit. Two intervention programs were offered. One intervention was a Healthy Lifestyle Program with education and support for a healthy diet and exercise. A second intervention was a Pregnancy Control Program that taught stress management and provided general care support but did not include information or support for diet and exercise. Women’s Health Advocates from the community interacted with the study participants.

Among Latinas, there was almost 90% retention through pregnancy and more than 80% retention through six weeks postpartum. There was also high participant, Women’s Health Advocate, and host site satisfaction. Vegetable consumption in the Healthy Lifestyle group increased significantly. Other analyses are still ongoing.

Preliminary results suggest significant decrease in diabetes risk factors for the healthy lifestyle group. The Community Women’s Health Advocates were instrumental in conducting home visits and working with the women.

Source http://www.detroiturc.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=15&Itemid=28

Cervical cancer screening, santa clara, ca.

Vietnamese-American women are five times more likely to develop cervical cancer than other American women. In Santa Clara, CA a REACH 2010 project aimed to increase Pap smear screening for early detection and prevention. The researchers ran a media campaign on the importance of screening in the community. The University of California also worked with the Vietnamese REACH Health Coalition and lay health workers to encourage Vietnamese Americans to get screened for cervical cancer. The study concluded that the women who spoke with the community health workers were more likely to get screened than the women who were exposed to the media campaign alone.

An evaluation of coalition programs showed that 47.7% of participants who had never had a Pap test received one after meeting with a lay health worker. The evaluation also showed that 17.9% of participants received a mammogram and 27.9% received a clinical breast exam after meeting with a lay health worker, compared with 3.9% and 5.1%, respectively, of women who did not meet with a lay health worker. In addition, 52.1% of participants had a repeat Pap test within 18 months, and 4,187 women enrolled in a reminder system. The study took place from 2004-2007 and involved 105,000 Vietnamese-American women.

Source http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494888/

Weact food justice initiative, new york, ny.

The goals of the Food Justice Initiative are to understand the challenges and opportunities that children, parents, school officials and residents face regarding healthy food choices in school and at home through research. The WEACT Food Justice Initiative works with community residents in Northern Manhattan grassroots groups and other New York organizations to help influence and develop programs, laws and policies that affect access to healthy food in Northern Manhattan. WEACT has conducted surveys with community residents and schools. They are currently investigating the supply chain of public school lunches to better understand the ingredients and nutritional makeup of the food purchased by the New York City Public School system. One key portion of the Food Justice Initiative is educating policy makers on food justice issues and providing recommendations for improved policies at the City, State and Federal levels.

In addition, WEACT works at the community level to involve parents, students, teachers, the school board, school administrators, and the public in development of the local wellness policies at several Northern Manhattan schools. Since nearly all Northern Manhattan public school students are low-income, this is a critical window of opportunity to empower the community work together to influence policy for greater equality. WEACT educates and mobilizes the public school community to advocate for healthier policies at the NYC Board of Education, City Council, NYS Legislature and NYS Departments of Education and Health.

WEACT for Environmental Justice is a Northern Manhattan community-based organization whose mission is to build healthy communities by assuring that people of color and/or low-income participate meaningfully in the creation of sound and fair environmental health and protection policies and practices.

Source http://www.weact.org/Programs/EnvironmentalHealthCBPR/NorthernManhattanFoodJusticeInitiative/tabid/206/Default.aspx

Additional resources, cdc healthy homes, community engaged scholarship 4 health, community-campus partnerships for health, developing and sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: a skill building curriculum, healthy homes ii asthma project, king county healthy homes project, seattle, wa, reach cdc success stories, reach: the power to reduce health disparities, the community toolbox (university of kansas), important question.

What could research do in your community?

Please take some time to think about and discuss this question with your group or others.

to review Unit 2: Informed Decision-Making

Go to next page

to learn about how To Get Involved

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 28 November 2022

Community-engaged research is stronger and more impactful

- Gabrielle Wong-Parodi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5207-7489 1

Nature Human Behaviour volume 6 , pages 1601–1602 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

838 Accesses

4 Citations

9 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Research management

Based on her own experience, Gabrielle Wong-Parodi describes how a community-engaged approach has the potential to strengthen research and increase its impact.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. Principles of Community Engagement (NIH publication no. 11-7782) (Department of Health and Human Services USA, 2011).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The OCOB project was developed under assistance agreement no. 84024001 awarded by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to G.W.-P. (Stanford University) and S.-H. Cho (RTI International). This World View has not been formally reviewed by the EPA. The views expressed in this document are solely those of G.W.-P. and do not necessarily reflect those of the agency. The EPA does not endorse any products or commercial services mentioned in this World View. OCOB is also supported by a National Science Foundation CAREER award (SES-2045129), Stanford Center for Population Health Sciences award and United States Parcel Service Endowment Fund at Stanford award to G.W.-P., and by a Stanford Impact Labs award to J. Suckale.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Earth System Science, the Woods Institute for the Environment, and Environmental Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

Gabrielle Wong-Parodi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gabrielle Wong-Parodi .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wong-Parodi, G. Community-engaged research is stronger and more impactful. Nat Hum Behav 6 , 1601–1602 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01494-5

Download citation

Published : 28 November 2022

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01494-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Financial incentives overcome ego-depletion effect in the waste separation task.

- Pingping Liu

Current Psychology (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

24 Community-Based Research: Understanding the Principles, Practices, Challenges, and Rationale

Margaret R. Boyd Bridgewater State University Bridgewater, MA, USA

- Published: 01 July 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Community-based research challenges the traditional research paradigm by recognizing that complex social problems today must involve multiple stakeholders in the research process—not as subjects but as co-investigators and co-authors. It is an “orientation to inquiry” rather than a methodology and reflects a transdisciplinary paradigm by including academics from many different disciplines, community members, activists, and often students in all stages of the research process. Community-based research is relational research where all partners change and grow in a synergistic relationship as they work together and strategize to solve issues and problems that are defined by and meaningful to them. This chapter is an introduction to the historical roots and subdivisions within community-based research and discusses the core principles and skills useful when designing and working with community members in a collaborative, innovative, and transformative research partnership. The rationale for working within this research paradigm is discussed as well as the challenges researchers and practitioners face when conducting community-based research. As the scholarship and practice of this form of research has increased dramatically over the last twenty years, this chapter looks at both new and emerging issues as well as founding questions that continue to be debated in the contemporary discourse.

It is best to begin, I think, by reminding you, the beginning student, that the most admirable thinkers within the scholarly community you have chosen to join do not split their work from their lives. They seem to take both too seriously to allow such disassociation. — C.W. Mills, (1959 , 195)

Community-based research challenges the traditional research paradigm by recognizing that complex social problems today must involve multiple stakeholders in the research process—not as subjects but as co-investigators and co-authors. It has roots in critical pedagogy, as well as critical and feminist theory, and is research centered on social justice and community empowerment. Community-based research is not a methodology; it is an “orientation to inquiry” where researchers and community stakeholders collaborate to address community-identified problems and investigate meaningful and realistic solutions. Community-based research came out of a growing discontent among academics, researchers, and practitioners with the positivist research paradigm and instead argues that research must be “value based” not “value free.” It is relational research that fosters both individual and collective transformation. Community-based research also challenges disciplinary silos and instead fosters a transdisciplinary research paradigm.

There has been a growing interest and expectation within academia and community organizations that campus–community research partnerships provide benefits and challenges. We have seen a proliferation of research partnerships, courses, workshops and trainings on how to collaborate with community partners in community-driven research projects. There has also been a substantial increase in the literature (books and articles) describing best practices providing exemplars, and discussing methodologies. Israel, Eng, Schulz, and Parker (2005) argue that within the field of public health “researchers, practitioners, community members, and funders have increasingly recognized the importance of comprehensive and participatory approaches to research and intervention” (3).

This chapter begins with a discussion of the historical roots and theoretical background to this form of inquiry and a clarification of terminology. I include a discussion of the rationale and evaluation literature that offers convincing evidence for new and experienced researchers to consider this alternative research paradigm. Building on the work of others, I discuss seven core principles of community-based research and a list of skills often useful in the practice of engaged scholarship. This chapter argues that, as community-based research continues to grow, it is important that our scholarship includes exemplars, reflection, evaluation, and a critical discussion of best practices. This chapter hopes to contribute to this discourse.

I cannot think for others or without others, nor can others think for me. Even if the peoples thinking is superstitious or naïve, it is only as they rethink their assumptions in action that they can change. Producing and acting upon their own ideas—not consuming those of others. — Freire, 1970 , 108

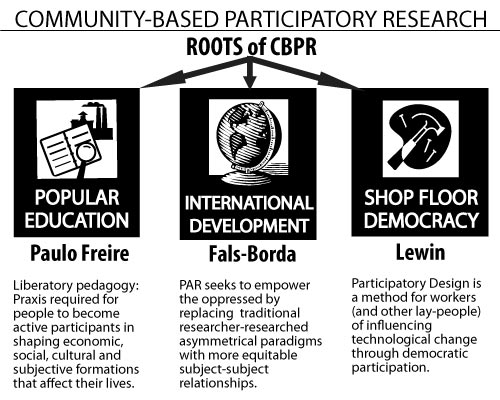

The epistemology of community-based research can be traced back to many roots—Karl Marx, John Dewey, Paulo Freire, C.W. Mills, Thomas Kuhn, and Jane Addams to name but a few. Community-based research as it is practiced today has been enriched by the diversity of thoughts, methodologies, and practices that has been its foundation. The practice and scholarship of community-based research can found in many disciplines: sociology, psychology, economics, philosophy, education, public health, anthropology, urban planning and development, and social work. Different historical traditions and academic disciplines have led to contemporary differences in the form or focus of engaged scholarship, but what has united many practitioners and scholars is a social justice mission and the desire for personal and structural transformation. Lykes and Mallona (2008) argue:

Critical pedagogy (Freire) and liberation theologies (Berryman, Boff, Gutierrez, Ruether, Cone) and liberation psychologies (Martin-Baro, Watts, and Serrano-Garcia, Moane) emerged within relatively similar historical moments characterized by widespread social upheavals including armed struggle and broad- based non-violent social movements. A belief that the poor could be producers of knowledge and lead the transformation to a new social reality. [114]

Today you can find community-based research pedagogy, practices and scholarship across disciplines and collaboration between disciplines including new areas such as medicine, native or aboriginal research, conflict studies, history, and archeology. The expansion of community-engaged scholarship as epistemology reflects an important paradigm shift towards understanding multiple ways of knowing and experiential learning as critical to good research practices.

While it is not possible to include an extensive summary of the history and development of community-based research here, a brief review is necessary to provide the context and rationale for this major epistemological paradigm shift across multiple disciplines. Wicks, Reason, and Bradbury (2008) identify the influence of critical theory, civil rights, feminist movements, liberationists, and critical race theory—“critiques of domination and marginalization” and “critical examination of issues of power, identity and agency” (19). The historical roots and scholars who, I believe, have most influenced the development of community-based research are critical pedagogy (Paulo Freire and John Dewey), critical theory (Karl Marx and C.W. Mills), the epistemology of knowledge (Thomas Kuhn), and feminist theory (Jane Addams).

While Marx is noted for his writing about the conditions of the working class in Europe and his theories of alienation and oppression under capitalism, he was also an active participant in the French Revolution. According to Hall (cited in Ozerdem and Bowd, 2010 ) Marx was not only doing research and theorizing about the working classes but actively working with the workers to educate and raise consciousness. In addition to building theory, Marx and Engels sought to radically change and improve the political, economic, and social structure of society. The need to work with those most disadvantaged to challenge institutional inequality and power relationships is reflected in the principles of community-based research today. Many academics and scholars working from a critical theoretical perspective found a synergy with the principles and practices of community-based research.

Within education, John Dewey and Paulo Freire were reformers, activists, and key figures working to challenge traditional pedagogy and positivist research practices. Both were very influential in connecting research, theory, action, and refection to social reform. John Dewey (1859–1952) questioned the relevance of much of what was considered “education” by asking, “How many found what they did learn so foreign to the situations of life outside the school as to give them no power or control over the latter” (cited in Noll, 2010 , 8). Dewey saw educational institutions as agencies of social reform and social change through providing opportunities for learning and engagement with the world beyond the classroom. Summarizing Dewey, Peterson (2009) wrote:

Dewey believed that learning is a wholehearted affair; that is, you can’t sever knowing and doing, and with cycles of action and reflection, one’s greatest learning occurs. Dewey was interested in the learning that resulted from the mutual exchange between people and their environment. [542]

Dewey argued that learning—action and reflection—must take place in commune with one’s environment. Learning is co-created rather than unidirectional; a challenge to the traditional view of knowledge transfer from teacher to learner. Co-education and co-learning are key principles of community-based research.

Paulo Freire (1921–1997), the founder of critical pedagogy, also challenged conventional educational pedagogy and traditional research paradigms and saw education’s potential as liberation from oppression. His most famous and widely distributed book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970) , was a call to action for both teacher and student to work together for social change and social reform. Freire saw learning as a two-way process involving “conscientization”—critical analysis and reflection leading to action. It is only through theory and practice, action and reflection, that real social change is possible. He also saw that the poor and oppressed can and must be leaders of their own liberation. Freire’s work—in challenging pedagogy and demanding researchers and academics to work with and learn from those most oppressed—has greatly influenced the practice of community-based research today.

Sociologist C.W. Mills also influenced critical pedagogy and engaged scholarship. In his classic work The Sociological Imagination (1959) he wrote:

An educator must begin with what interests the individual most deeply, even if it seems altogether trivial and cheap. He must proceed in such a way and with such materials as to enable the student to gain increasingly rational insight into these concerns, and into others he will acquire in the process of his education.... [187], We are trying to make the society more democratic. [189]

Similar to Freire, Mills challenged the social sciences to educate and through experiential education to foster democratic citizenry. Mills saw the connection between personal troubles and public issues and the role of sociology in helping others see the larger structures in society and how they reinforced inequality.

Another scholar who had a major influence on the development of community-based research is Thomas Kuhn in his classic book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1996). Kuhn’s work regarding the theory of the subjective nature of knowledge raised epistemological questions of “how we know what we know” and “what it is that we value as knowledge” (Wicks, Reason, & Bradbury, 2008 ). This became critically important in the development of engaged scholarship as academics and researchers began to respect and validate local knowledge, expertise, and other ways of thinking as equal to the knowledge and skills they could offer. Kuhn’s work led to questions about the privileged position of the researcher and how this privilege has denied or denigrated the experiential knowledge and understandings of oppressed groups.

It is also important to note the influence of feminist theory, in particular Jane Addams, on the development of community-based research and scholarship. Addams (1860–1935), a social activist and sociologist, played a key role in the development of engaged scholarship and community research. Naples (1996) writes that feminists argued for “a methodology designed to break the false separation between the subject of the research and the researcher” (160). Addams employed hundreds of women to go into their communities to interview, observe, and understand the experiences of other immigrant women in Chicago early in the twentieth century.

Addams also saw the need to make research relevant to the communities in which it originated. Much of the data gathered in Chicago was published as Hull House Maps and Papers (1895) and was for the benefit of the community, not for an academic audience. Her focus was social justice and social change, not theoretical conceptualizations of urban poverty. In writing about Jane Addams and the Chicago School, Deegan (1990) stated that Addams wrote “all the book’s royalties would be waived as we have little thought about the financial gain” (57). Deegan goes on to argue that Addams’ interests were in “empowering the community, the laborer, the elderly and youth, women and immigrants” (255). Addams, similar to Dewey and later Freire, was also very critical of traditional education, which reproduced inequality. Deegan (1990) writes that Addams articulated a goal of “generating reflective adults” (283).

Definitions, Terminology, and Subdivisions

We have exemplars of the methods of participatory research and canons for their practice, even if we cannot as yet agree on a single name. — Couto (2003 , 69)

Clarification of terminology is necessary before beginning a discussion of the principles and skills of community-based research,. Broadly defined, campus–community research collaboration can be referred to as community-based research (CBR), community-based participatory research (CBPR), collaborative research, engaged scholarship, participatory research (PR), participatory action research (PAR), action research (AR), aboriginal community research, popular education, participatory rural appraisal, public scholarship, university–community research collaboration, co-inquiry, and synergistic research. New terms and subdivisions continue to emerge. Strand, Marullo, Cutforth, Stoecker, and Donohue (2003a) suggest that practitioners of CBR come “from within and outside academia and work in areas throughout the world—all of which makes any commonly-accepted definition problematic” (6).

It is not my intent here to minimize or ignore the different historical roots or traditions reflected in the above forms of campus-community research, but a discussion of the distinct nature of each is beyond the scope of this chapter. Acknowledging that there are differences, this chapter will focus on commonalities and core principles that can apply broadly to campus—community research partnerships. Generally, the term “community-based research,” or CBR, is used here, although I have tried to include the terms used by authors when describing their own research. Other scholars have also focused on similarities rather than differences. Atalay (2010) suggests that, “regardless of the terminology used, the central tents remain the same” (419). CBR aims to connect academic researchers with individuals, groups, and community organizations to collaborate on a research project to solve community-identified and community-defined problems. CBR is intended to educate, empower, and transform at the individual, community, and structural level to challenge inequality and oppression.

While using a broad brush to be inclusive of all campus–community research partnerships, it is important to address what I see as two important differences in the goals and outcomes within CBR. For many practitioners, the ideal is a long-term, collaborative, and egalitarian partnership that builds community, fosters transformation, and promotes social change. Academics conduct research with and for the community, and all participants teach and learn in a synergistic relationship. Clayton, Bringle, Senor, Huq, and Morrison (2010) argue that campus–community relationships can be short term (transactional) or, ideally, a partnership in which both parties grow and change because of a deeper and more sustained (transformative) relationship.

For others, (e.g., McNaughton & Rock, 2004 ; Nygreen, 2009 –2010) the relationship between academic researchers, the university, and the community is always contentious, and power is rarely equal. For this reason, some CBR practitioners advocate community members learn the skills and knowledge necessary to conduct their own research within their communities. Nyden, Figbert, Shibley, and Burrows (1997) write, “Participatory Action Research aims at empowering the community by giving it the tools to do its own research and not to be beholden to universities or university professors to complete the work” (17). Academic researchers within this tradition are looking to empower local communities to be researchers and authors of their own transformation. The goal is to foster self-determination and self-reliance of the disenfranchised and powerless so they can be self-sufficient ( Park, 1993 ).

From this perspective, a long-term or sustained partnership with academic researchers could be seen as exploitive and disempowering.

Another major difference is that. for many, the goal of CBR includes pedagogy ( Strand, 2000 ). CBR provides an opportunity to involve students in a research project with community partners, often as part of their curriculum requirement. Strand, Marullo, Cutforth, Stoecker, and Donohue (2003b , xxi) suggest CBR is a way to “unite the three traditional academic missions of teaching, research and service in innovative ways.” CBR as pedagogy can bring students together with faculty and community partners to address community problems, as well as learn valuable skills regarding democratic research processes, communication, and civic responsibility. Porpora (1999 , 121) considers CBR “the highest state of service learning” and important as a way to promote engaged citizenship among students. There is an extensive body of research discussing the benefits, challenges, and practice of CBR as pedagogy that has generally found substantial benefits to students.

What is meant by “community” within the term community-based research requires some clarification. Alinsky (1971 , 120) noted that “in a highly mobile, urbanized society the word ‘community’ means community of interest, not geographic location.” This suggests a collective identity with shared goals, issues, or problems, or a shared fate ( Israel, Eng, Schultz & Parker, 2005 ). This has been particularly evident in the growing number of international community–researcher collaborative partnerships. Pinto et al (2007) writes:

International researchers need to become members, even if from afar, of the communities that host their studies, so that they can be part of the interactions that affect social processes and people’s understanding of their behaviors and identities. These interactions may occur at physical, psycho-social and electronic levels, encompassing geographic and virtual spaces and behaviors, social and cultural trends, and psychological constructs and interpretations. [55]

Accepting that today individuals and groups can participate in numerous “communities of interest” at the local and global level, many exemplars of CBR are situated in geographically defined communities. The community, however, is rarely a unified or homogenous group. It often includes groups within groups, competing and contentious factions, and members with diverse perspectives, needs and expectations ( Atalay, 2010 ). The diversity of participants within CBR projects reflects both the strengths and the challenges of engaged scholarship and will be discussed later in this chapter.

A final clarification with regards to CBR is that it is not the same as community organizing or advocacy. CBR includes scientific investigation respecting research ethics, methodologies, and analysis. CBR practitioners and community partners are seeking knowledge and understanding through data collection and analysis. The findings will inform decisions as to community organizing, social action, or advocacy work. Fuentes (2009 –2010, 733) makes the distinction between “ community organizing ,” which usually focuses on the development and support of leaders and “ organizing community ,” which “centers on community building, collectivism, caring, mutual respect, and self-transformation.” CBR is about organizing community to create research partnerships to address inequalities. Another misconception is that CBR is a form of public service. Public service implies a one-way transfer of knowledge, expertise, and action from the campus to the community. CBR is a multi-directional process that results in shared and collaborative teaching, learning, action, reflection, and transformation.

We both know some things, neither of us knows everything. Working together, we will both know more, and we will both learn more about how to know. — Maguire (1987 37–38)

There is universal agreement that research is critical in terms of planning, implementing, and evaluating policies and programs. Nyden and Wiewel (1992 , 44) state, “research is a political resource that can be used as ammunition” to provide credible evidence regarding funding, programs, and or policy decisions. So why do CBR? For engaged scholars and activist working within a CBR paradigm, the reasons for doing so are numerous—personal and structural transformation, co-education, community empowerment, capacity building, and a belief in the need to democratize the research process. Even though engaged scholarship has not always been given the support and resources needed within academia, many argue that it is the only type of research that really makes a difference. Reason and Bradbury (2008) assert “indeed we might respond to the disdainful attitude of mainstream social scientists to our work that action research practices have changed the world in far more positive ways than conventional social science” (3). Rahman (2008) in summarizing the early work of Budd Hall in the 1970s states, “Participatory Action Research is a more scientific method of research because the full participation of the community in the research process facilitates a more accurate and authentic analysis of social reality” (51).

For many engaged scholars, ethical research requires working with and for individuals and groups, not doing research on or about subjects. Collaboration with multiple stakeholders allows for an opportunity to re-conceptualize problems and come up with innovative solutions. For many, this form of research is “more than creating knowledge; in the process it is educational, transformative and mobilization for action” ( Gaventa; 1993 ; xiv–xv). Community-based researchers acknowledge that this form of inquiry is not the only way, but often it is the best way to address the magnitude and complexity of contemporary social programs. It requires researchers across disciplines and from multiple perspectives, together with activists and community members, to join as equal partners and to think about and strategize solutions that are meaningful and beneficial to them. The benefits of combining scientific methods and lived experiences to re-conceptualize problems and find solutions are clear. Involving community stakeholders in all stages of the research process also increases the chances that solutions will be relevant and meaningful to community members. CBR is ideally situated to inform best practices as it is research generated from the ground up.

For more traditional social scientists, the reasons for considering CBR may reflect pressure from outside funders or community members. There has been a growing frustration with traditional research that the findings have not been applied or benefited the community or broader society. Nyden, Figert, Shibley, and Burrows (1997 , 3) state, “Traditional academic research has focused on furthering sociological theory and research” and not social action or social justice. Forty years ago, Fritz and Plog saw traditional research methods as no longer viable within archeology, stating:

We suspect that unless archaeologists find ways to make their research increasingly relevant to the modern world, the modern world will find itself increasingly capable of getting along without archaeologists. [ Cited in Atalay, 2010 , 419].

This concern has been raised within other disciplines and is reflected in the development of CBR and scholarship.

There are also very good reasons for institutions of higher education to align their mission to reflect a commitment to serve. Boyer (1994) suggests that the historical roots of higher education as a service to the community and a “public good” have diminished. He argues for the “New American College”—an institution that celebrates and fosters action, theory, practice, and reflection among faculty, students, and practitioners to solve the very real problems facing communities today. Colleges and universities must respond to and engage with communities to listen, learn, and work together on solutions. Netshandama (2010) describes how the University of Venda in South Africa changed over the course of four years to “align its vision and mission to the needs of the community at local, regional, national, continental and international levels” (72). Netshandama (2010) argues that the university did not just support faculty or add resources; their vision was to “integrate community engagement into the core business of the university” (72).

Methodology and a Transdisciplinary Paradigm

CBR is not a research methodology. Researchers and community members use a variety of methods to gather data about a community issue or problem and then seek solutions. It reflects a radical paradigm shift away from positivist methods of inquiry to what Leavy (2011) refers to as “a holistic, synergistic, and highly collaborative approach to research” (83). It can be best understood as a “ philosophy of inquiry ” ( Cockerill, Meyers, & Allman, 2000 ) or an “ orientation to inquiry ” ( Reason & Bradbury, 2008 ) that seeks to create participative communities of inquiry to collaborate to address community problems. Practitioners of CBR recognize and value multiple ways of knowing and do not privilege the knowledge or skills of the researcher over local experiences, skills, and methodologies. Torre and Fine (2011) suggest that PAR “represents a practice of research, a theory of method and an epistemology that values the intimate, painful and often shamed knowledge held by those who have most endured social injustice” (116). At its best, CBR reflects a democratization of the research process and a validation of multiple forms of knowledge, expertise, and methodologies. It is a shift away from research “subjects” to research collaborators and colleagues.

Although CBR is not a methodology, it does address the recent methodological questions concerning the role of “reflexivity” in research design and practice. Subramaniam (2009) states, “After adopting reflexivity as a valid research process, the researcher must make decisions about her status vis-à-vis those being researched and become conscious about their status in relation to her, the researcher” (203). This has led to further methodological questions concerning the validity of traditional binaries such as “researcher/researched,” “insider/outsider,” and “objective/subjective.” These statuses are addressed openly and critically in CBR projects. For example, critical psychologists often face an ethical dilemma when involved in CBR projects. Baumann, Rodriguez, and Parra-Cardona (2011 , 142) refer to this dilemma, citing the American Psychological Association (APA) Code of Ethics that states psychologists must refrain from “multiple and dual relationships with clients and community members.” For CBR practitioners, research is relational. Scientific “objectivity” is problematic and does not strengthen the validity of research outcomes.

CBR lends itself to mixed method design and often reflects a transdisciplinary research paradigm. According to Leavy (2011) , “Transdisciplanarity is a social justice oriented approach to research in which resources and expertise from multiple disciplines are integrated in order to holistically address a real-world issue or problem” (35). Leavy argues that “transdisciplanarity does not mean the abandonment of disciplines (34)” but rather knowledge gained through this form of inquiry transcends traditional disciplinary silos. I would agree that CBR reflects a “transdisciplanary research paradigm” and that this also includes community scholars outside academia.

Although data can result from many methods, there are core principles or tenets of CBR that are generally agreed upon by most practitioners. Scholars do disagree on the number of core principles. However, the unique nature of every CBR project allows for flexibility and differences. The principles represent guidelines or best practices, and are helpful for setting goals and for praxis,—continuous reflection, and action. They are also interconnected and interdependent. Each principle can be conceptualized along a continuum. For example, Schwartz (2010) suggests that PAR can include research that has minimal collaboration to projects that have full participation of all stakeholders in every stage of the research process with most projects falling somewhere in the middle.

Principles of Community-Based Research