- Results & Stories

- News & Opinion

- Publications & Resources

- People and Structures

- Partnerships

- History of the Global Fund

- Staff & Organization

- Strategy (2023-2028)

- The Global Fund’s Monitoring and Evaluation Framework

Our Partnership

- Civil Society

- Friends of the Fund

- Government & Public Donors

- Implementing Partners

- Private Sector & Foundations

- Technical & Development Partners

Key Structures

- Country Coordinating Mechanisms

- Independent Evaluation & Learning

- Local Fund Agents

- Office of the Inspector General

- Technical Review Panel

Engage With Us

- Business Opportunities

- Tuberculosis

- Climate Change and Health

- Community Responses & Systems

- Human Rights

- Gender Equality

- Global Health Security

- Key Populations

- Protection from Sexual Exploitation, Abuse and Harassment

- Community Health Workers

- Digital Health

- Sustainability, Transition & Co-Financing

Replenishment

- How We Raise Funds

- Seventh Replenishment

Our Financing

- How We Fund Our Grants

- Who We Fund

- Funding Decisions

Grant Life Cycle

- Applying for Funding

- Grant-making

- Grant Implementation

- Throughout the Cycle

- Operational Policy

- Information Sessions

- Programmatic Monitoring for Grants

- M&E Systems Strengthening

- Sourcing & Management of Health Products

Results & Data

- Data Explorer

- Data Service (Downloadable reports)

Results Report 2024

- All Stories

Impact Stories

In Uganda, Laboratories Innovate to Prepare for Future Disease Threats

Bangladesh: Providing TB Services to People Displaced by Climate Change

The Philippines: Supporting Country- and Community-led Efforts to End Malaria

Sudan: Supporting People With Essential Health Care in Crisis

More Stories

Media Resources

- Digital Library

- Photo Galleries

- All News Releases

- All Opinion

- All Updates

News Releases

Global Fund Approves US$5 Million for Rwanda’s Mpox Response, Expands Emergency …

The World’s First Global Oxygen Strategic Framework and Investment Case Calls fo…

Global Fund Approves Additional Funding to Sustain Health Services in Bangladesh…

UNGA: Progress in Global Health Shows the Path to a Safer, More Secure World

We Are Still Here

Walking in Other People’s Shoes

Global Fund Helps Bolster Indonesia’s Health Products Supply Chain Digitization

Global Fund and Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development Sign Multiyear Contrib…

HIV Prevention Evaluation

Publication Categories

- Publications

- Donor Reports

- Impact Reports

- Thematic Reports

- Partnership Reports

- Governance & Policies

- iLearn Online Learning

Featured Publications

Strengthening Health and Community Systems At a glance (2024)

Our Next Generation Market Shaping Approach (2024)

Malaria At a Glance (2024)

COVID-19 Response in the Philippines

20 January 2022

The Philippines has been severely affected by COVID-19. According to latest WHO figures , as of 17 January 2022, the Philippines had recorded over 3 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 with over 52,700 deaths. Since March 2020, the country has taken strict measures to halt the spread of the virus, including lockdowns such as Enhanced Community Quarantines.

The impact of COVID-19 has especially been significant on TB and HIV. In 2020, the National TB Control Program recorded a marked decrease in TB testing as well as notification for TB and drug-resistant TB (DR-TB). In 2021, COVID-19 cases surged again as the Delta variant spread.

In 2021, through our COVID-19 Response Mechanism (C19RM), the Global Fund supported the Philippines with over US$37.7 million to fight COVID-19, including to expand COVID-19 testing capacities and support the COVID-19 case management strategy. In addition, interventions focus on COVID-19 mitigation measures for HIV, TB and malaria programs. This includes telemedicine, mobile clinics, bidirectional testing, digital tools to help patients adhere to their treatment, improving TB case finding and transportation networks to transport samples, supporting differentiated service delivery approach to providing HIV services, and integrating information campaigns for COVID-19 and malaria. The programs also support social protection interventions, community-based organization strengthening, addressing human rights barriers to health care and services, and HIV mitigation measures addressing community needs like mental health support and gender-based violence prevention. The Philippines was one of the first countries to develop a strong comprehensive TB adaptive plan to the impact of COVID-19.

The Global Fund uses cookies for anonymized statistics on website use and content performance to help us improve and adapt the website. To consent to the use of cookies, please click “Accept”. To learn more about your rights and options, please read our Privacy Statement .

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Early response to COVID-19 in the Philippines

Arianna maever l amit, veincent christian f pepito, manuel m dayrit.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence to Arianna Maever L. (email: [email protected] )

Collection date 2021 Jan-Mar.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution IGO License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/legalcode ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In any reproduction of this article there should not be any suggestion that WHO or this article endorse any specific organization or products. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. This notice should be preserved along with the article's original URL.

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with weak health systems are especially vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this paper, we describe the challenges and early response of the Philippine Government, focusing on travel restrictions, community interventions, risk communication and testing, from 30 January 2020 when the first case was reported, to 21 March 2020. Our narrative provides a better understanding of the specific limitations of the Philippines and other LMICs, which could serve as basis for future action to improve national strategies for current and future public health outbreaks and emergencies.

The Philippine health system and the threat of public health emergencies

Despite improvements during the past decade, the Philippines continues to face challenges in responding to public health emergencies because of poorly distributed resources and capacity. The Philippines has 10 hospital beds and six physicians per 10 000 people. ( 1 , 2 ) and only about 2335 critical care beds nationwide. ( 3 ) The available resources are concentrated in urban areas, and rural areas have only one physician for populations up to 20 000 people and only one bed for a population of 1000. ( 4 ) Disease surveillance capacity is also unevenly distributed among regions and provinces. The primary care system comprises health centres and community health workers, but these are generally ill-equipped and poorly resourced, with limited surge capacity, as evidenced by lack of laboratory testing capacity, limited equipment and medical supplies, and lack of personal protective equipment for health workers in both primary care units and hospitals. ( 5 ) Local government disaster preparedness plans are designed for natural disasters and not for epidemics.

Inadequate, poorly distributed resources and capacity nationally and subnationally have made it difficult to respond adequately to public health emergencies in the past, as in the case of typhoon Haiyan in 2013. ( 6 ) The typhoon affected 13.3 million people, overwhelming the Government’s capacity to mobilize human and financial resources rapidly to affected areas. ( 7 ) Failure to deliver basic needs and health services resulted in disease outbreaks, including a community outbreak of gastroenteritis. ( 8 ) Access to care has improved in recent years due to an increase in the number of private hospital beds; ( 5 ) however, improvements in private sector facilities mainly benefit people who can afford them, in both urban and rural areas.

In this paper, we describe the challenges and early response of the Philippine Government, focusing on travel restrictions, community interventions, risk communication and testing, from 30 January 2020 when the first case was reported, to 21 March 2020.

Early response to COVID-19

Travel restrictions.

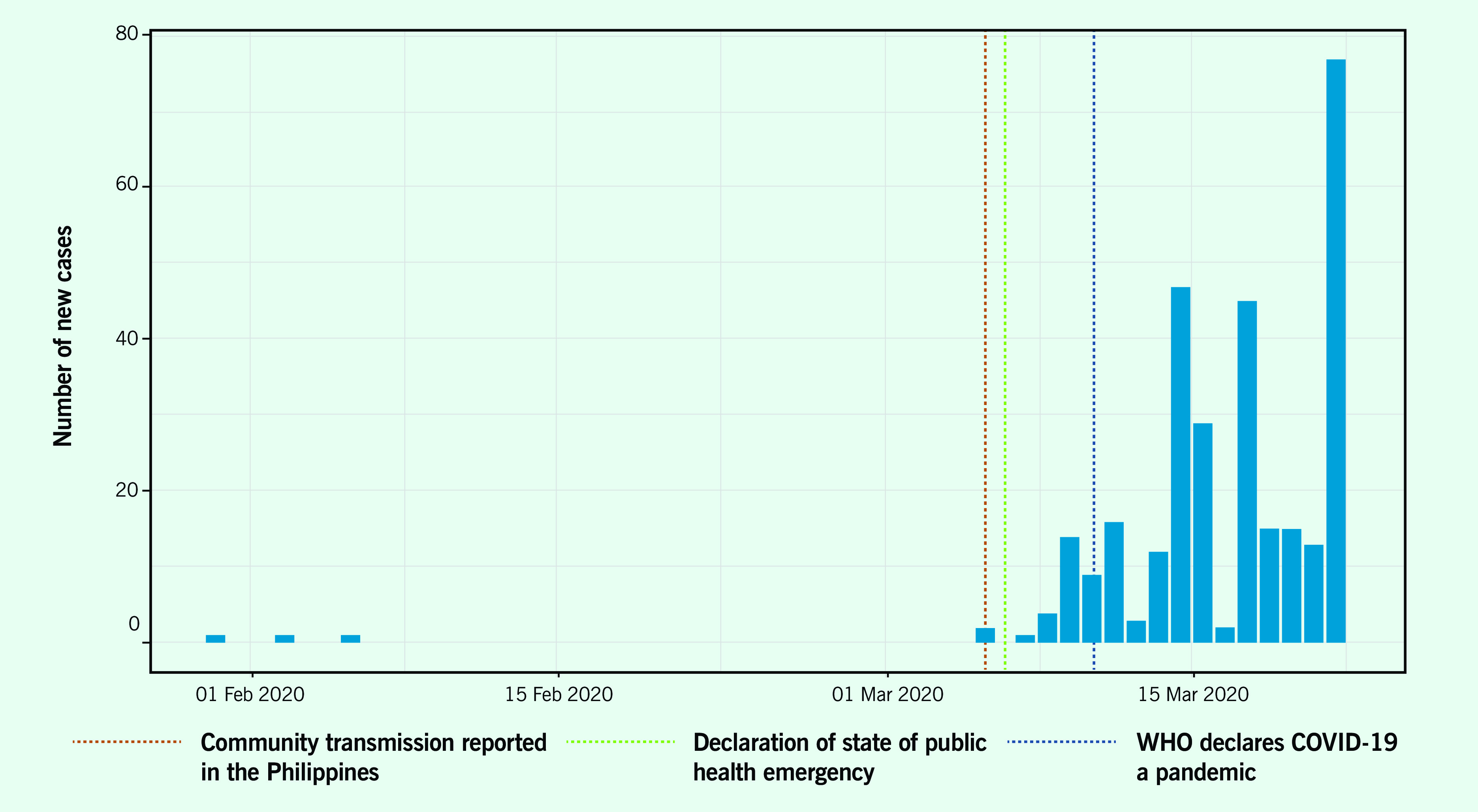

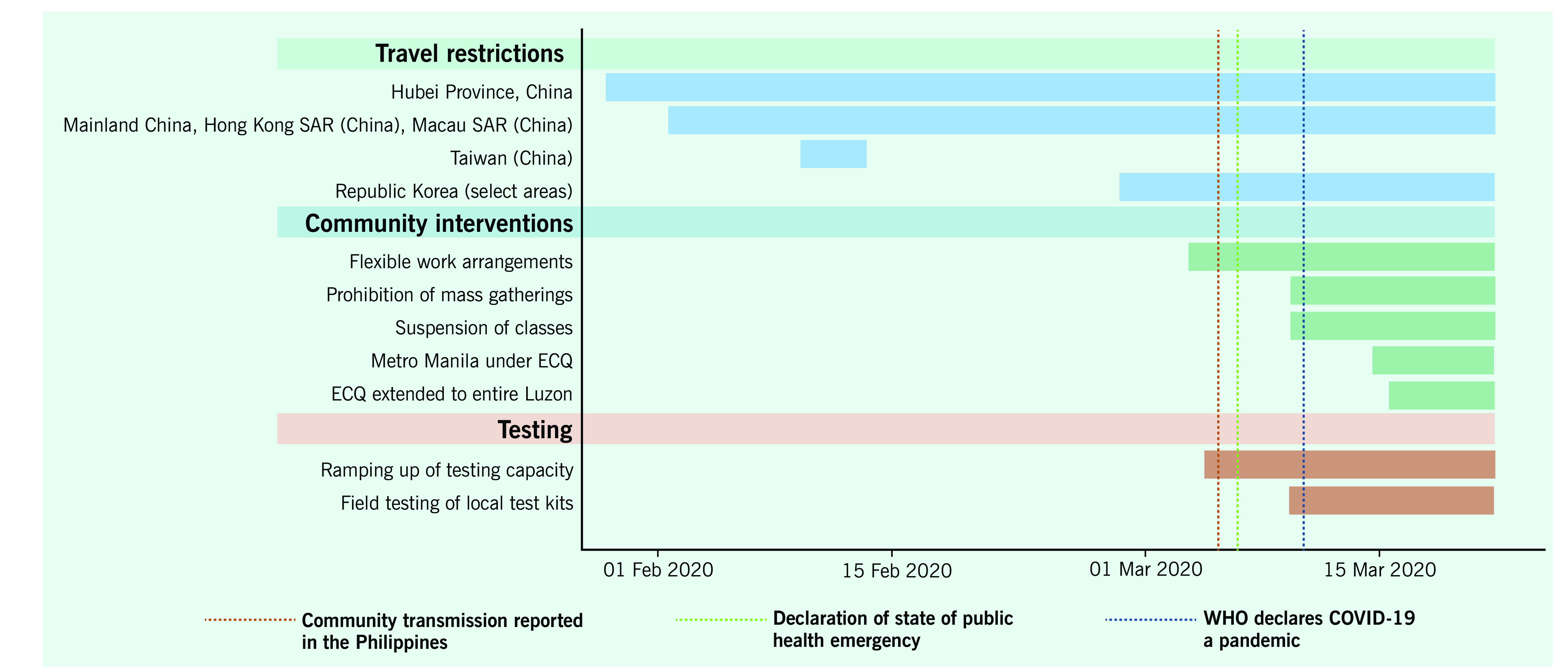

Travel restrictions in the Philippines were imposed as early as 28 January, before the first confirmed case was reported on 30 January ( Fig. 1a ). ( 9 ) After the first few COVID-19 cases and deaths, the Government conducted contact tracing and imposed additional travel restrictions, ( 10 ) with arrivals from restricted countries subject to 14-day quarantine and testing. While travel restrictions in the early phase of the COVID-19 response prevented spread of the disease by potentially infected people, travellers from countries not on the list of restricted countries were not subject to the same screening and quarantine protocols. The restrictions were successful in delaying the spread of the disease only briefly, as the number of confirmed cases increased in the weeks that followed. ( 11 ) Fig. 1b shows all interventions, including travel restrictions undertaken before 6 March, when the Government declared the occurrence of community spread, and after 11 March, when WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

New cases of COVID-19 in the Philippines, 30 January–21 March 2020

[ insert Figure 1a ]

Timeline of key events and developments in the Philippines, 30 January–21 March 2020

[ insert Figure 1b ]

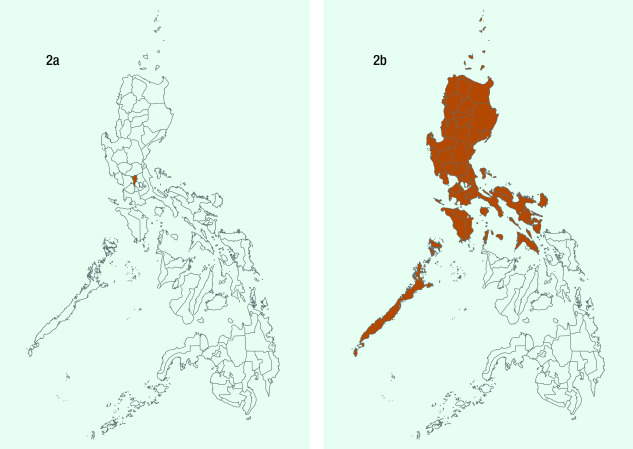

Community interventions

The Government declared “enhanced community quarantine” (ECQ) for Metro Manila between 15 March and 14 April ( Fig. 2a ), which was subsequently extended to the whole island of Luzon ( Fig. 2b ). The quarantine consisted of: strict home quarantine in all households, physical distancing, suspension of classes and introduction of work from home, closure of public transport and non-essential business establishments, prohibition of mass gatherings and non-essential public events, regulation of the provision of food and essential health services, curfews and bans on sale of liquor and a heightened presence of uniformed personnel to enforce the quarantine procedures. ( 12 ) ECQ – an unprecedented move in the country’s history – was modelled on the lockdown in Hubei, China, which was reported to have slowed disease transmission. ( 13 ) Region-wide disease control interventions, such as quarantining of the entire Luzon island, were challenging to implement because of their scale and social and economic impacts, but they were deemed necessary to “flatten the curve” so that health systems were not overwhelmed. ( 14 ) While the lockdown implemented by the Government applied only to the island of Luzon, local governments in other parts of the country followed this example and also locked down. The ECQ gave the country the opportunity to mobilize resources and organize its pandemic response, which was especially important in a country with poorly distributed, scarce resources and capacity.

Provinces placed under enhanced community quarantine (ECQ). (2a) The Government declared ECQ in Metro Manila effective 15 March 2020; (2b) The Government declared ECQ on the entire island of Luzon effective 17 March 2020.

[ insert Figure 2 ]

Risk communication

The Government strengthened and implemented national risk communication plans to provide information on the new disease. The Government conducted daily press briefings, sponsored health-related television and Internet advertisements and circulated infographics on social media. Misinformation and conspiracy theories about COVID-19 were nevertheless a challenge for a population that spends more than 10 hours a day on the Internet. ( 15 , 16 ) These spread quickly and became increasingly difficult to correct. Furthermore, the Government’s messages did not reach all households, despite access to health services and information, resulting in limited knowledge of preventive practices, except for hand-washing. ( 17 )

Testing is key to controlling the pandemic but was done on a small scale in the Philippines. As of 19 March, fewer than 1200 individuals had been tested, ( 11 ) as only the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine located in Metro Manila performed tests and assisted subnational reference laboratories in testing. ( 18 ) No positivity rates for RT–PCR tests were reported until early April 2020. Because of the limited capacity for testing at the start of the pandemic, the Department of Health imposed strict protocols to ration testing resources while ramping up testing capacity. Most tests were conducted for individuals in urban areas, where the incidence was highest. ( 19 )

Conclusions

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the country’s initial response lacked organizational preparedness to counter the public health threat. The Philippines’ disease surveillance system could conduct contact tracing, but this was overwhelmed in the early phases of outbreak response. Similarly, in February, only one laboratory could conduct reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) testing, so the country could not rapidly deploy extensive laboratory testing for infected cases. In addition, the primary care system of the Philippines did not serve as a primary line of defence, as people went straight to hospitals in urban areas, overwhelming critical care capacity in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In response to the early phase of the pandemic, the Government of the Philippines implemented travel restrictions, community quarantine, risk communication and testing; however, the slow ramping up of capacities particularly on testing contributed to unbridled disease transmission. By 15 October, the number of confirmed cases had exponentially grown to 340 000 of which 13.8% were deemed active. ( 11 ) The lack of pandemic preparedness had left the country poorly defended against the new virus and its devastating effects. Investing diligently and consistently in pandemic preparedness, surveillance and testing capacity in particular is a lesson that the Philippines and other LMICs should learn from COVID-19.

Acknowledgements

Conflict of interests.

None reported

Not applicable

- 1. Hospital beds (per 1,000 people). Washington, DC: World Bank; 2020. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS

- 2. World Bank open data. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2019. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/ , accessed 18 March 2020.

- 3. Phua J, Faruq MO, Kulkarni AP, Redjeki IS, Detleuxay K, Mendsaikhan N, et al. ; Asian Analysis of Bed Capacity in Critical Care (ABC) Study Investigators, and the Asian Critical Care Clinical Trials Group. Critical Care Bed Capacity in Asian Countries and Regions. Crit Care Med. 2020. May;48(5):654–62. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004222 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Human resources for health country profiles: Philippines. Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2013. Available from: https://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/7869/9789290616245_eng.pdf

- 5. Dayrit M, Lagrada L, Picazo O, Pons M, Villaverde M. The Philippines health system review. New Delhi: WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2018. [cited 2020 August 28]. Available from: Available from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274579 [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. McPherson M, Counahan M, Hall JL. Responding to Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. West Pac Surveill Response. 2015. November 6;6 Suppl 1:1–4. 10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.4.HYN_026 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Santiago JSS, Manuela WS Jr, Tan MLL, Sañez SK, Tong AZU. Of timelines and timeliness: lessons from Typhoon Haiyan in early disaster response. Disasters. 2016. October;40(4):644–67. 10.1111/disa.12178 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Ventura RJ, Muhi E, de los Reyes VC, Sucaldito MN, Tayag E. A community-based gastroenteritis outbreak after Typhoon Haiyan, Leyte, Philippines, 2013. West Pac Surveill Response. 2015. January 10;6(1):1–6. 10.5365/wpsar.2014.5.1.010 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases. Resolution No. 01. Recommendations for the management of the novel coronavirus situation. Manila: Department of Health; 2020. Available from: https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/2020/01jan/20200128-IATF-RESOLUTION-NO-1-RRD.pdf , accessed 3 June 2020.

- 10. February files. Manila: Civil Aeronautics Board; 2020. Available from: https://www.cab.gov.ph/announcements/category/february-16 , accessed 19 March 2020.

- 11. Updates of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Manila: Department of Health; 2020. Available from: https://www.doh.gov.ph/2019-nCov , accessed 16 October 2020.

- 12. Marquez C. Palace releases temporary guidelines on Metro Manila community quarantine. Inquirer News. 14 March 2020. Available from: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1241790/palace-releases-temporary-guidelines-on-metro-manila-community-quarantine , accessed 18 April 2020.

- 13. Leung K, Wu JT, Liu D, Leung GM. First-wave COVID-19 transmissibility and severity in China outside Hubei after control measures, and second-wave scenario planning: a modelling impact assessment. Lancet. 2020. April 25;395(10233):1382–93. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30746-7 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Wilder-Smith A, Freedman DO. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020. March 13;27(2):taaa020. 10.1093/jtm/taaa020 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Digital 2020: The Philippines. DataReportal – global digital insights. Available from: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-philippines , accessed 28 August 2020.

- 16. Nicomedes CJC, Avila RMA. An analysis on the panic during COVID-19 pandemic through an online form. J Affect Disord. 2020. November 1;276:14–22. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.046 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Lau LL, Hung N, Go DJ, Ferma J, Choi M, Dodd W, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of COVID-19 among income-poor households in the Philippines: A cross-sectional study. J Glob Health. 2020. June;10(1):011007. 10.7189/jogh.10.011007 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Nuevo CE, Sigua JA, Boxshall M. Wee Co PA, Yap ME. Scaling up capacity for COVID-19 testing in the Philippines. Coronavirus (COVID-19) blog posts collection. London: BMJ Journals; 2020. [cited 2020 August 28]. Available from: Available from https://blogs.bmj.com/bmjgh/2020/06/05/scaling-up-capacity-for-covid-19-testing-in-the-philippines/ [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Decision tool for 2019 novel coronavirus acute respiratory disease (2019-nCoV ARD) health event as of January 30, 2020. Manila: Department of Health; 2020. Available from: https://www.doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/health-update/COVID-19-Advisory-No2.pdf , accessed 28 August 2020.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (1.4 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Supporting the Philippines’ COVID-19 Emergency Response

Beneficiaries

For Vilma Campos , a Quezon City resident and mother of five, life has improved since her family received their vaccinations. “My daughter has resumed working, so has my husband,” she said. “Life is no longer that difficult.”

Before COVID-19 hit, Vilma’s job was taking care of children. When the authorities started implementing quarantine restrictions, she, her daughter, and her spouse lost their jobs. Vilma said her family was always wondering where to get the next meal. “What gave us hope was the arrival of vaccines,” she said. “Things have improved and I really wish we can all overcome this pandemic.”

The Philippines was one of the countries hit hardest by COVID-19 in the East Asia and Pacific region. To manage the spread of the virus, authorities implemented strict quarantine restrictions and health protocols, restricted mobility of people as wells as the operational capacity of businesses. As a result, the Philippine economy suffered. In 2020, GDP contracted 9.5 percent, driven by significant declines in consumption and investment growth, and exacerbated by the sharp slowdown in exports, tourism, and remittances. Many Filipinos lost jobs and experienced food shortages and difficulties accessing health care. Due to global shortages, procurement of COVID-19 vaccines, medical supplies, personal protective equipment (PPE), reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test machines, and test kits proved challenging in the early phases of the pandemic.

The project supported the country’s efforts to scale up vaccination across the national territory, strengthen the country’s health system, and overcome the impact of the pandemic especially on the poor and the most vulnerable. Besides vaccines, the project supported procurement of PPE, essential medical equipment such as mechanical ventilators, cardiac monitors, portable x-ray machines; laboratory equipment and test kits; and ambulances. The project also supported construction and refurbishment of negative pressure isolation rooms and quarantine facilities, as well as the expansion of the country’s laboratory capacity at the national and sub-national levels for prevention of and preparedness against emerging infectious diseases. It funded retrofitting of the national reference laboratory – the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM) – as well as six sub-national and public health laboratories in Baguio, Cebu, Davao, and Manila, and the construction and expansion of laboratory capacity in priority regions without such facilities.

During year1 to year 2, the following results were achieved:

- The project supported the procurement and deployment of 33 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine across the country. The project supported pediatric vaccination for 7.5 million children. With the support of development partners including the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank, the Philippines administered more than 137 million vaccines (more than 126 million first and second doses, and more than 10 million booster doses) by March of 2022.

- The project helped scale up testing capacity from 1,000 RT-PCR tests per day to 24,979 per day.

- The project supported the procurement of 500 mechanical ventilators, 119 portable x-ray machines, 70 infusion pumps, 50 RT-PCR machines, and 68 ambulances.

- As a result of the strong vaccination rates and strengthened health response capacity, the Philippines is now much better able to manage the pandemic.

The Philippines COVID-19 Emergency Response Project supported the procurement and deployment of 33 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine across the country. The project also supported pediatric vaccination for 7.5 million Filipino children.

Bank Group Contribution

The World Bank through the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) provided $900 million of funding in total for the emergency response project. The project provided $100 million for medical and laboratory equipment and supplies; $500 million for primary vaccine doses, ancillaries, and end-to-end logistics; and $300 million for boosters and additional doses, and end-to-end logistics.

The World Bank collaborated with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) on project preparation and vaccines financing. The Bank worked with the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) on the Vaccine Introduction Readiness Tool (VIRAT) and Vaccine Readiness Assessment Tool (VRAF) Tool 2.0, which is used to assess status, gaps, and issues in four domains: planning and management, supply and distribution, program delivery, and supporting systems and infrastructure. Australia, through the AGaP Trust Fund, provided a US$300,000 grant to support implementation. The World Bank also collaborated with UNICEF to address vaccine hesitancy and with the WHO to procure RT-PCR machines and test kits.

Looking Ahead

The Philippine government is considering additional support for scaling up testing capacity. Equipment has been acquired and civil works commissioned through the project are now in use. An action plan is being developed for continued implementation of environmental and social safeguards employed in the project, such as COVID-19 waste management and assessment of accessibility of vulnerable groups to health care services. These will be institutionalized using the manuals developed and through directive issuances by the Department of Health. The project also supports the development of National Action Plan Towards Increased Accessibility of Health Care Facilities for Vulnerable Groups. The World Bank is also supporting the Department of Health and priority LGUs in strengthen local health systems for Universal Health Coverage.

Philippines Covid-19 Emergency Response Project

Philippines Covid-19 Emergency Response Project Additional Financing

Philippines COVID-19 Emergency Response Project – Additional Financing 2

Department of Health Covid-19 Tracker.

Department of Health Covid-19 Updates on Covid-19 Vaccines

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

- Open access

- Published: 21 September 2021

Local government responses for COVID-19 management in the Philippines

- Dylan Antonio S. Talabis 1 , 2 ,

- Ariel L. Babierra 1 , 2 ,

- Christian Alvin H. Buhat 1 , 2 ,

- Destiny S. Lutero 1 , 2 ,

- Kemuel M. Quindala III 1 , 2 &

- Jomar F. Rabajante 1 , 2 , 3

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 1711 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

562k Accesses

32 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Responses of subnational government units are crucial in the containment of the spread of pathogens in a country. To mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Philippine national government through its Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases outlined different quarantine measures wherein each level has a corresponding degree of rigidity from keeping only the essential businesses open to allowing all establishments to operate at a certain capacity. Other measures also involve prohibiting individuals at a certain age bracket from going outside of their homes. The local government units (LGUs)–municipalities and provinces–can adopt any of these measures depending on the extent of the pandemic in their locality. The purpose is to keep the number of infections and mortality at bay while minimizing the economic impact of the pandemic. Some LGUs have demonstrated a remarkable response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of this study is to identify notable non-pharmaceutical interventions of these outlying LGUs in the country using quantitative methods.

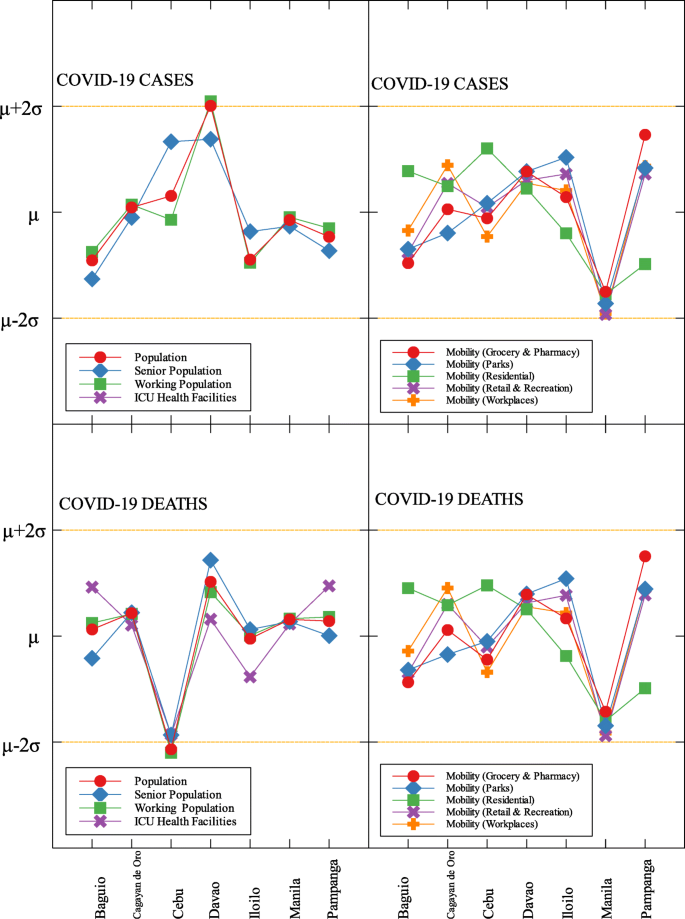

Data were taken from public databases such as Philippine Department of Health, Philippine Statistics Authority Census, and Google Community Mobility Reports. These are normalized using Z-transform. For each locality, infection and mortality data (dataset Y ) were compared to the economic, health, and demographic data (dataset X ) using Euclidean metric d =( x − y ) 2 , where x ∈ X and y ∈ Y . If a data pair ( x , y ) exceeds, by two standard deviations, the mean of the Euclidean metric values between the sets X and Y , the pair is assumed to be a ‘good’ outlier.

Our results showed that cluster of cities and provinces in Central Luzon (Region III), CALABARZON (Region IV-A), the National Capital Region (NCR), and Central Visayas (Region VII) are the ‘good’ outliers with respect to factors such as working population, population density, ICU beds, doctors on quarantine, number of frontliners and gross regional domestic product. Among metropolitan cities, Davao was a ‘good’ outlier with respect to demographic factors.

Conclusions

Strict border control, early implementation of lockdowns, establishment of quarantine facilities, effective communication to the public, and monitoring efforts were the defining factors that helped these LGUs curtail the harm that was brought by the pandemic. If these policies are to be standardized, it would help any country’s preparedness for future health emergencies.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of cases have already reached 82 million worldwide at the end of 2020. In the Philippines, the number of cases exceeded 473,000. As countries around the world face the continuing threat of the COVID-19 pandemic, national governments and health ministries formulate, implement and revise health policies and standards based on recommendations by world health organization (WHO), experiences of other countries, and on-the-ground experiences. Early health measures were primarily aimed at preventing and reducing transmission in populations at risk. These measures differ in scale and speed among countries, as some countries have more resources and are more prepared in terms of healthcare capacity and availability of stringent policies [ 1 , 2 ].

During the first months of the pandemic, several countries struggled to find tolerable, if not the most effective, measures to ‘flatten’ the COVID-19 epidemic curve so that health facilities will not be overwhelmed [ 3 , 4 ]. In responding to the threat of the pandemic, public health policies included epidemiological and socio-economic factors. The success or failure of these policies exposed the strengths or weaknesses of governments as well as the range of inequalities in the society [ 5 , 6 ].

As national governments implemented large-scale ‘blanket’ policies to control the pandemic, local government units (LGUs) have to consider granular policies as well as real-time interventions to address differences in the local COVID-19 transmission dynamics due to heterogeneity and diversity in communities. Some policies in place, such as voluntary physical distancing, wearing of face masks and face shields, mass testing, and school closures, could be effective in one locality but not in another [ 7 – 9 ]. Subnational governments like LGUs are confronted with a health crisis that have economic, social and fiscal impact. While urban areas have been hot spots of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are health facilities that are already well in placed as compared to less developed and deprived rural communities [ 10 ]. The importance of local narratives in addressing subnational concerns are apparent from published experiences in the United States [ 11 ], China [ 12 , 13 ], and India [ 14 ].

In the Philippines, the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF) was convened by the national government in January 2020 to monitor a viral outbreak in Wuhan, China. The first case of local transmission of COVID-19 was confirmed on March 7, 2020. Following this, on March 8, the entire country was placed under a State of Public Health Emergency. By March 25, the IATF released a National Action Plan to control the spread of COVID-19. A community quarantine was initially put in place for the national capital region (NCR) starting March 13, 2020 and it was expanded to the whole island of Luzon by March 17. The initial quarantine was extended up to April 30 [ 5 , 15 ]. Several quarantine protocols were then implemented based on evaluation of IATF:

Community Quarantine (CQ) refers to restrictions in mobility between quarantined areas.

In Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ), strict home quarantine is implemented and movement of residents is limited to access essential goods and services. Public transportation is suspended. Only economic activities related to essential and utility services are allowed. There is heightened presence of uniformed personnel to enforce community quarantine protocols.

Modified Enhanced Community Quarantine (MECQ) is implemented as a transition phase between ECQ and GCQ. Strict home quarantine and suspension of public transportation are still in place. Mobility restrictions are relaxed for work-related activities. Government offices operates under a skeleton workforce. Manufacturing facilities are allowed to operate with up to 50% of the workforce. Transportation services are only allowed for essential goods and services.

In General Community Quarantine (GCQ), individuals from less susceptible age groups and without health risks are allowed to move within quarantined zones. Public transportation can operate at reduced vehicle capacity observing physical distancing. Government offices may be at full work capacity or under alternative work arrangements. Up to 50% of the workforce in industries (except for leisure and amusement) are allowed to work.

Modified General Community Quarantine (MGCQ) refers to the transition phase between GCQ and the New Normal. All persons are allowed outside their residences. Socio-economic activities are allowed with minimum public health standard.

LGUs are tasked to adopt, coordinate, and implement guidelines concerning COVID-19 in accordance with provincial and local quarantine protocols released by the national government [ 16 ].

In this study, we identified economic and demographic factors that are correlated with epidemiological metrics related to COVID-19, specifically to the number of infected cases and number of deaths [ 17 , 18 ]. At the regional, provincial, and city levels, we investigated the localities that differ with the other localities, and determined the possible reasons why they are outliers compared to the average practices of the others.

We categorized the data into economic, health, and demographic components (See Table 1 ). In the economic setting, we considered the number of people employed and the number of work hours. The number of health facilities provides an insight into the health system of a locality. Population and population density, as well as age distribution and mobility, were used as the demographic indicators. The data (as of November 10, 2020) from these seven factors were analyzed and compared to the number of deaths and cumulative cases in cities, provinces or regions in the Philippines to determine the outlier.

The Philippine government’s administrative structure and the availability of the data affected its range for each factor. Regional data were obtained for the economic component. For the health and demographic components, data from cities and provinces were retrieved from the sources. Due to the NCR exhibiting the highest figures in all key components, an investigation was conducted to identify an outlier among its cities. The z -transform

where x is the actual data, μ is the mean and σ is the standard deviation were applied to normalize the dataset. Two sets of normalized data X and Y were compared by assigning to each pair ( x , y ), where x ∈ X and y ∈ Y , its Euclidean metric d given by d =( x − y ) 2 . Here, the Y ’s are the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths, and X ’s are the other demographic indicators. Since 95% of the data fall within two standard deviations from the mean, this will be the threshold in determining an outlier. This means that if a data pair ( x , y ) exceeds, by two standard deviations, the mean of the Euclidean metric values between the sets X and Y , the pair is assumed to be an outlier.

To identify a good outlier, a bias computation was performed. In this procedure, Y represents the normalized data set for the number of deaths or the number of cases while X represents the normalized data set for every factor that were considered in this study. The bias is computed using the metric

for all x in X and y in Y . To categorize a city, province, or region as a good outlier, the bias corresponding to this locality must exceed two standard deviations from the mean of all the bias computations between the sets X and Y .

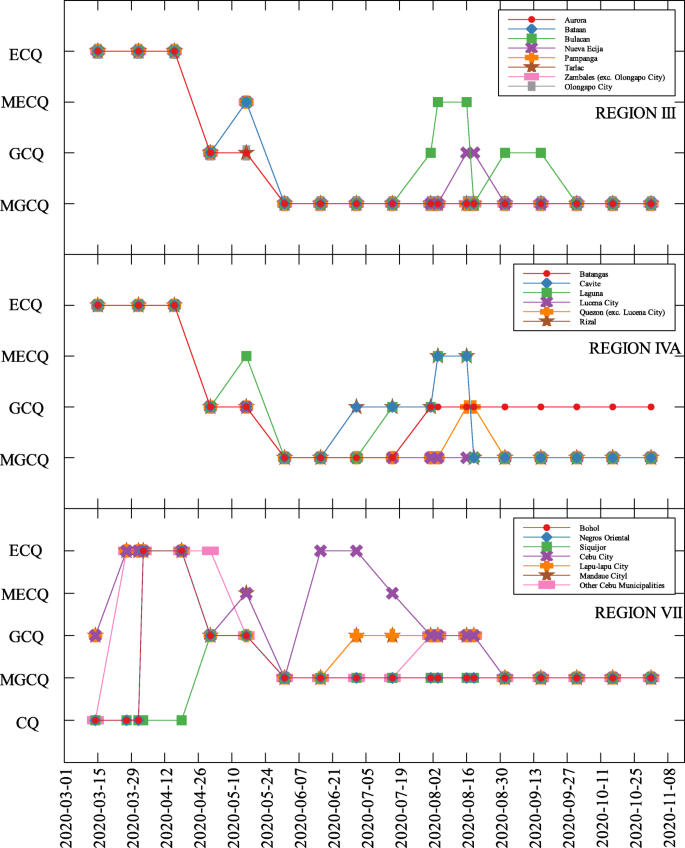

Results and discussion

The data used were the reported COVID-19 cases and deaths in the Philippines as of November 10, 2020 which is 240 days since community lockdowns were implemented in the country. Figure 1 shows the different lockdowns implemented per province since March 15. It can be seen that ECQ was implemented in Luzon and major cities in the country in the first few weeks since March 15, and slowly eased into either GCQ or MGCQ as time progressed. By August, the most stringent lockdown was MECQ in the National Capital Region (NCR) and some nearby provinces. Places under MECQ on September were Iloilo City, Bacolod City, and Lanao del Sur, with the last province as the lone community to be placed under MECQ the month after. By November 1, 2020, communities were either placed under GCQ or MGCQ.

COVID-19 community quarantines in Regions III, IVA and VII

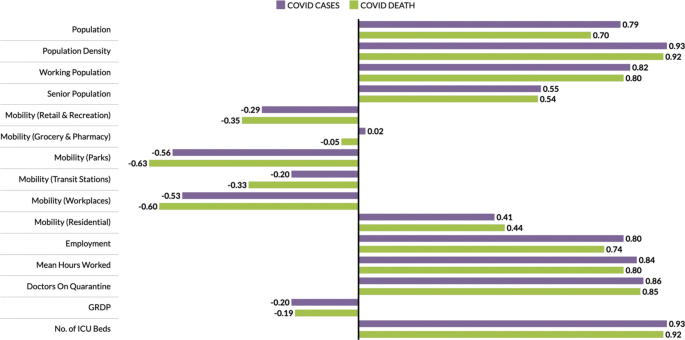

Comparison of economic, health, and demographic components and COVID-19 parameters

The economic, health and demographic components were compared to COVID-19 cases and deaths. These comparisons were done for different community levels (regional, provincial, city/metropolitan) (See Tables 2 , 3 , and 4 ). Figure 2 summarizes the correlation of components to COVID-19 cases and deaths at the regional level. In all components, correlations with other parameters to both COVID-19 cases and deaths are close. Every component except Residential Mobility and GRDP have slightly higher correlation coefficient for COVID-19 cases as compared to COVID-19 deaths.

Correlation of components to COVID-19 cases and deaths at the regional level

Among the components, the number of ICU beds component has the highest correlation with COVID-19 parameters. This makes sense as this is one of the first-degree measures of COVID-19 transmission. Population density comes in second, followed by mean hours worked and working population, which are all related to how developed the region is economy-wise. Regions having larger population density also have a huge working population and longer working hours [ 24 ]. Thus, having a huge population density implies high chance of having contact with each other [ 25 , 26 ]. Another component with high correlation to the cases and deaths is the number of doctors on quarantine, which can be looked at two ways; (i) huge infection rate in the region which is the reason the doctors got exposed or are on quarantine, and (ii) lots of doctors on quarantine which resulted to less frontliners taking care of the infected individuals. All definitions of mobility and the GDP are not strongly correlated to any of the COVID-19 measures.

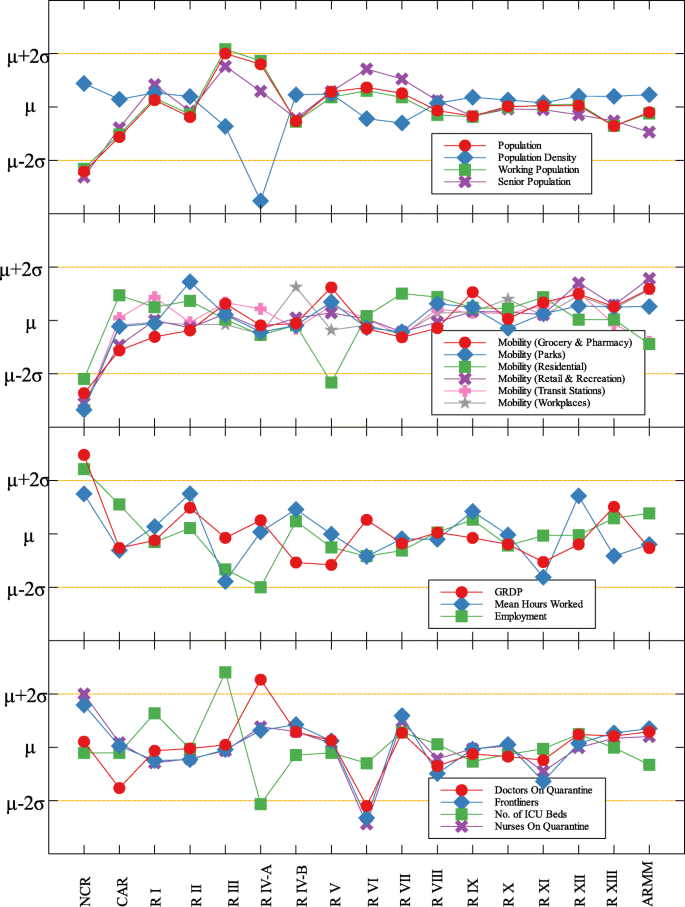

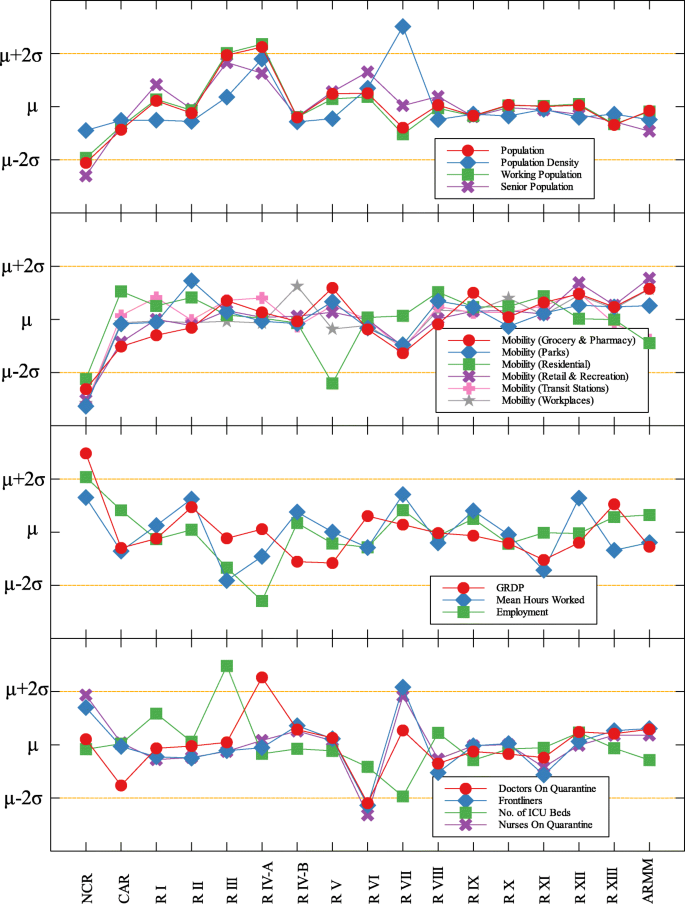

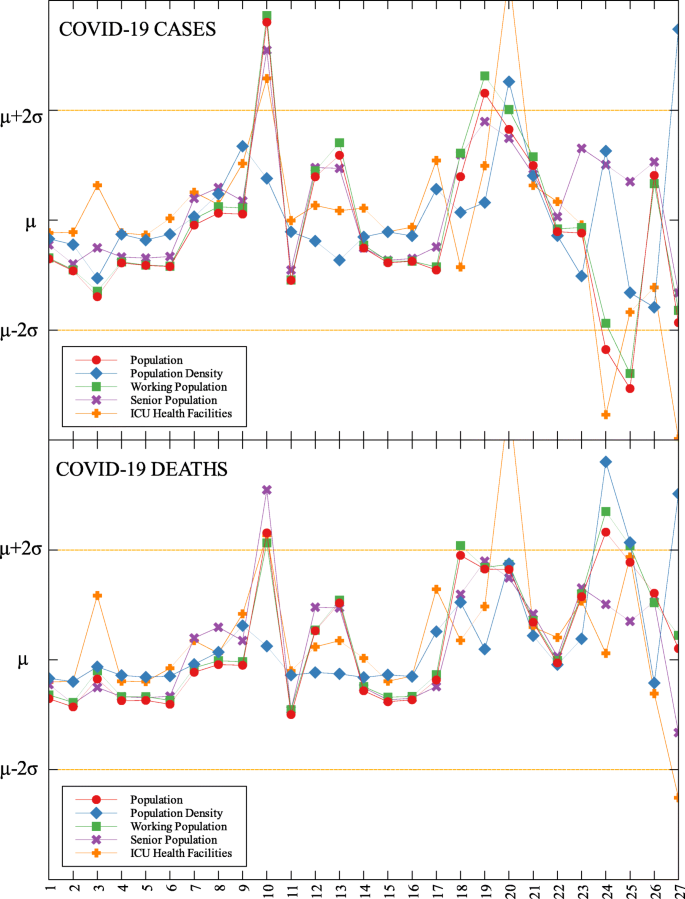

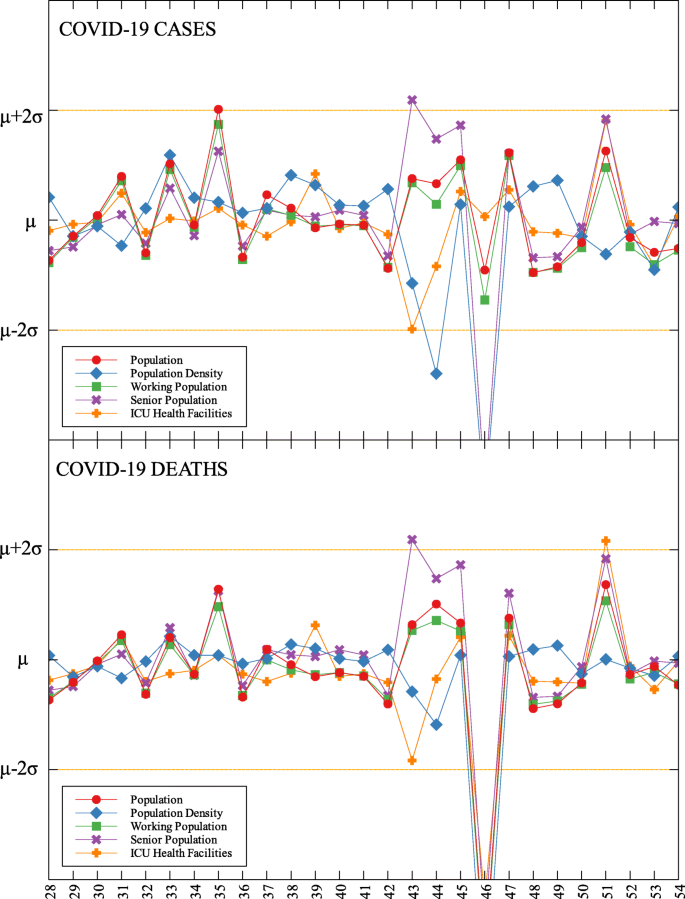

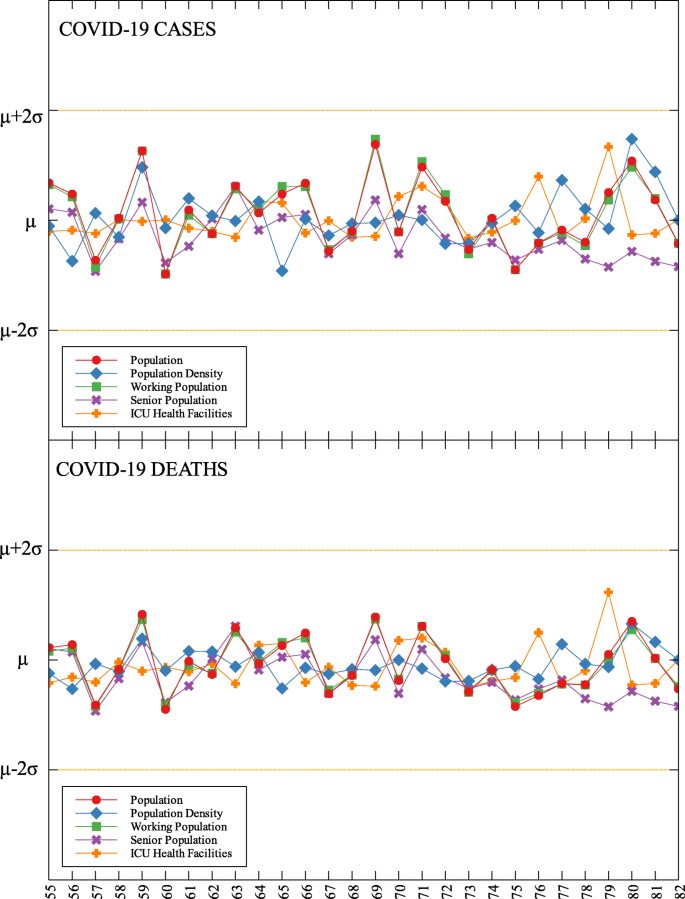

In each data set, outliers were identified depending on their distance from the mean. For simplicity, we denote components that are compared with COVID-19 cases by (C) and with COVID-19 deaths by (D). The summary of outliers among regions in the Philippines is shown in Figs. 3 and 4 . Data is classified according to groups of component. In each outlier region, non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) implemented and their timing are identified.

Outliers among regions in the Philippines with respect to COVID-19 cases

Outliers among regions in the Philippines with respect to COVID-19 deaths

Region III is an outlier in terms of working population (C) and the number of ICU beds (C) (see Fig. 5 and Table 5 ). This means that considering the working population of the region, the number of COVID-19 infections are better than that of other regions. Same goes with the number of ICU beds in relation to COVID-19 deaths. Region III is comprised of Aurora, Bataan, Nueva Ecija, Pampanga, Tarlac, Zambales, and Bulacan. This good performance might be attributed to their performance especially on their programs against COVID-19. As early as March 2020, the region had been under a community lockdown together with other regions in Luzon. Being the closest to NCR, Bulacan has been the most likely to have high number of COVID-19 cases in the region. But the province responded by opening infection control centers which offer free healthcare, meals, and rooms for moderate-severe COVID-19 patients [ 27 ]. They have also implemented strict monitoring of entry-exit borders, organization of provincial task force and incident command center, establishment of provincial quarantine facilities for returning overseas Filipino workers, mandated municipal quarantine facilities for asymptomatic cases, and mass testing, among others [ 27 ]. Most of which have been proven effective in reducing the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths [ 28 ].

Outliers among the provinces in Luzon with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths

Outliers among the provinces in Visayas with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths

Outliers among the provinces in Mindanao with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths

Region IV-A is an outlier in terms of population and working population (D) and doctors on quarantine (D) (see Fig. 5 and Table 5 ). Considering their population and working population, the COVID-19 death statistics show better results compared to other regions. Same goes with the number of doctors in the region which are in quarantine in relation to the reported COVID-19 deaths. This shows that the region is doing well in terms of decreasing the COVID-19 fatalities compared to other regions in terms of populations and doctors on quarantine. Region IV-A is comprised of Batangas, Cavite, Laguna, Quezon, and Rizal. Same with Region III, they have been under the community lockdown since March of last year. Provinces of the region such as Rizal have been proactive in responding to the epidemic as they have already suspended classes and distributed face masks even before the nationwide lockdown [ 29 ]. Despite being hit by natural calamities, the region still continue ramping up the response to the pandemic through cash assistance, first aid kits, and spreading awareness [ 30 ].

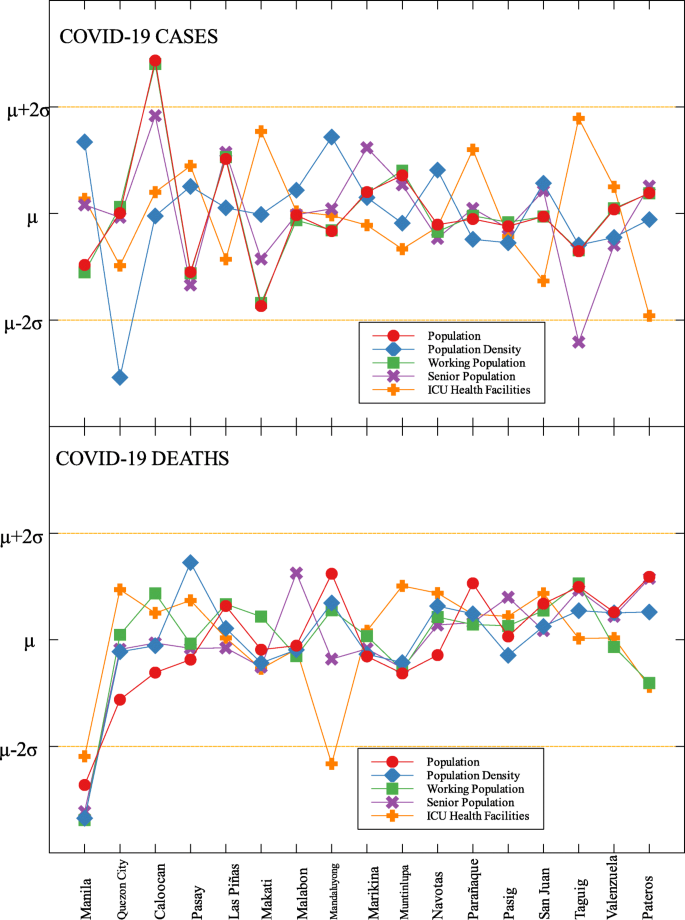

An interesting result is that NCR, the center of the country and the most densely populated, is a good outlier in terms of GRDP (C) and GRDP (D). Cities in the region launched various programs in order to combat the disease. They have launched mass testings with Quezon City, Taguig City, and Caloocan City starting as early as April 2020. Pasig City started an on-the-go market called Jeepalengke. Navotas, Malabon, and Caloocan recorded the lowest attack rate of the virus. Caloocan city had good strategies for zoning, isolation and even in finding ways to be more effective and efficient. Other programs also include color-coded quarantine pass, and quarantine bands. It is also possible that NCR may just have a very high GRDP compared to other regions. A breakdown of the outliers within NCR can be seen in Fig. 8 .

Outliers in the national capital region with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths

Region VII is also an outlier in terms of population density (D) and frontliners (D) (see Fig. 6 and Table 5 ). This means that given the population density and the number of frontliners in the region, their COVID-related deaths in the region is better than the rest of the country. This region consists of four provinces (Cebu, Bohol, Negros Oriental, and Siquijor) and three highly urbanized cities (Cebu City, Lapu-Lapu City, and Mandaue City), referred to as metropolitan Cebu. This significant decline may be explained by how the local government responded after they were placed in stricter community quarantine measures despite the rest of the country easing in to more lenient measures. Due to the longer and stricter quarantine in Cebu, the lockdown had a greater impact here than in other areas where restrictions were eased earlier [ 31 ]. Dumaguete was one of the destinations of the first COVID case in the Philippines [ 32 ], their local government was able to keep infections at bay early on. Siquijor was also COVID-19-free for 6 months [ 33 ]. The compounded efforts of the different provinces in the region can account for the region being identified as an outlier.

Among the metropolitan cities, Davao came out as a good outlier in terms of population (C) and working population (C) (see Figs. 7 , 9 , and Table 5 ). This result may be attributed to their early campaign on consistent communication of COVID-19-related concerns to the public [ 34 ]. They were also able to set up transportation for essential workers early on [ 35 ].

Outliers among metropolitan areas in the Philippines with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths

This study identified outliers in each data group and determined the NPIs implemented in the locality. Economic, health and demographic components were used to identify these outliers. For the regional data, three regions in Luzon and one in Visayas were identified as outliers. Apart from the minimum IATF recommended NPIs, various NPIs were implemented by different regions in containing the spread of COVID-19 in their areas. Some of these NPIs were also implemented in other localities yet these other localities did not come out as outliers. This means that one practice cannot be the sole explanation in determining an outlier. The compounding effects of practices and their timing of implementation are seen to have influenced the results. A deeper analysis of daily data for different trends in the epidemic curve is considered for future research.

Correlation tables, outliers and community quarantine timeline

Availability of data and materials.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, Ren R, Leung KSM, Lau EHY, Wong JY, Xing X, Xiang N, Wu Y, Li C, Chen Q, Li D, Liu T, Zhao J, Liu M, Tu W, Chen C, Jin L, Yang R, Wang Q, Zhou S, Wang R, Liu H, Luo Y, Liu Y, Shao G, Li H, Tao Z, Yang Y, Deng Z, Liu B, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Shi G, Lam TTY, Wu JT, Gao GF, Phil D, Cowling BJ, Yang B, Leung GM, Feng Z. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(13):1199–207.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hsiang S, Allen D, Annan-Phan S, Bell K, Bolliger I, Chong T, Druckenmiller H, Huang LY, Hultgren A, Krasovich E, Lau P, Lee J, Rolf E, Tseng J, Wu T. The effect of large-scale anti-contagion policies on the covid-19 pandemic. Nature. 2020; 584:262–67.

Anderson R, Heesterbeek JAP, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth T. Comment how will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the covid-19 epidemic?Lancet. 2020; 395. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5 .

Buhat CA, Torres M, Olave Y, Gavina MK, Felix E, Gamilla G, Verano KV, Babierra A, Rabajante J. A mathematical model of covid-19 transmission between frontliners and the general public. Netw Model Anal Health Inform Bioinforma. 2021; 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13721-021-00295-6 .

Ocampo L, Yamagishic K. Modeling the lockdown relaxation protocols of the philippine government in response to the covid-19 pandemic: an intuitionistic fuzzy dematel analysis. Socioecon Plann Sci. 2020; 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2020.100911 .

Weible C, Nohrstedt D, Cairney P, Carter D, Crow D, Durnová A, Heikkila T, Ingold K, McConnell A, Stone D. Covid-19 and the policy sciences: initial reactions and perspectives. Policy Sci. 2020; 53:225–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-020-09381-4 .

Article Google Scholar

Wibbens PD, Koo WW-Y, McGahan AM. Which covid policies are most effective? a bayesian analysis of covid-19 by jurisdiction. PLoS ONE. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244177 .

Mintrom M, O’Connor R. The importance of policy narrative: effective government responses to covid-19. Policy Des Pract. 2020; 3(3):205–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2020.1813358 .

Google Scholar

Chin T, Kahn R, Li R, Chen JT, Krieger N, Buckee CO, Balsari S, Kiang MV. Us-county level variation in intersecting individual, household and community characteristics relevant to covid-19 and planning an equitable response: a cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open. 2020; 10(9). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039886 .

OECD. The territorial impact of COVID-19: managing the crisis across levels of government. 2020. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-territorial-impact-of-covid-19-managing-the-crisis-across-levels-of-government-d3e314e1/#biblio-d1e5202 . Accessed 20 Feb 2007.

White ER, Hébert-Dufresne L. State-level variation of initial covid-19 dynamics in the united states. PLoS ONE. 2020; 15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240648 .

Lin S, Huang J, He Z, Zhan D. Which measures are effective in containing covid-19? — empirical research based on prevention and control cases in China. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.28.20046110 . https://www.medrxiv.org/content/early/2020/03/30/2020.03.28.20046110.full.pdf .

Mei C. Policy style, consistency and the effectiveness of the policy mix in China’s fight against covid-19. Policy Soc. 2020; 39(3):309–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1787627. http://arxiv.org/abs/https: //doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1787627.

Dutta A, Fischer HW. The local governance of covid-19: disease prevention and social security in rural india. World Dev. 2021; 138:105234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105234 .

Vallejo BM, Ong RAC. Policy responses and government science advice for the covid 19 pandemic in the philippines: january to april 2020. Prog Disaster Sci. 2020; 7:100115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100115 .

Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases. Omnibus guidelines on the implementation of community quarantine in the Philippines. 2020. https://doh.gov.ph/node/27640 . Accessed 20 Feb 2020.

Roy S, Ghosh P. Factors affecting covid-19 infected and death rates inform lockdown-related policymaking. PloS ONE. 2020; 15(10):0241165. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241165 .

Pullano G, Valdano E, Scarpa N, Rubrichi S, Colizza V. Evaluating the effect of demographic factors, socioeconomic factors, and risk aversion on mobility during the covid-19 epidemic in france under lockdown: a population-based study. Lancet Digit Health. 2020; 2(12):638–49.

Department of Health. COVID-19 tracker. 2020. https://doh.gov.ph/covid19tracker . Accessed 25 Nov 2020.

Authority PS. Philippine population density (based on the 2015 census of population). 2020. https://psa.gov.ph/content/philippine-population-density-based-2015-census-population . Accessed 11 Apr 2020.

Google. COVID-19 community mobility report. 2020; https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility?hl=en. Accessed 25 Nov 2020.

Authority PS. Labor force survey. 2020. https://psa.gov.ph/statistics/survey/labor-and-employment/labor-force-survey?fbclid=IwAR0a5GS7XtRgRmBwAcGl9wGwNhptqnSBm-SNVr69cm8sCVd9wVmcoKHRCdU . Accessed 11 Apr 2020.

Authority PS. https://psa.gov.ph/grdp/tables?fbclid=IwAR3dKvo3B5eauY7KcWQG4VXbuiCrzFHO4b-f1k5Od76ccAlYxUimUIaqs94 . Accessed 11 Apr 2020. 2020.

Peterson E. The role of population in economic growth. SAGE Open. 2017; 7:215824401773609. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017736094 .

Buhat CA, Duero JC, Felix E, Rabajante J, Mamplata J. Optimal allocation of covid-19 test kits among accredited testing centers in the philippines. J Healthc Inform Res. 2021; 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41666-020-00081-5 .

Hamidi S, Sabouri S, Ewing R. Does density aggravate the covid-19 pandemic?: early findings and lessons for planners. J Am Plan Assoc. 2020; 86:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1777891 .

Philippine News Agency. Bulacan shares anti-COVID-19 best practices. 2020. https://mb.com.ph/2020/08/16/bulacan-shares-anti-covid-19-best-practices/ . Accessed Mar 2020.

Buhat CA, Villanueva SK. Determining the effectiveness of practicing non-pharmaceutical interventions in improving virus control in a pandemic using agent-based modelling. Math Appl Sci Eng. 2020; 1:423–38. https://doi.org/10.5206/mase/10876 .

Hallare K. Cainta, Rizal suspends classes, distributes face masks over coronavirus threat. 2020. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1238217/cainta-rizal-suspends-classes-distributes-face-masks-over-coronavirus-threat . Accessed Mar 2020.

Relief International. Responding to COVID-19 in the Aftermath of Volcanic Eruption. 2020. https://www.ri.org/projects/responding-to-covid-19-in-the-aftermath-of-volcanic-eruption/. Accessed Mar 2020.

Macasero R. Averting disaster: how Cebu City flattened its curve. 2020. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/explainers/how-cebu-city-flattened-covid-19-curve/ . Accessed Mar 2020.

Edrada EM, Lopez EB, Villarama JB, Salva-Villarama EP, Dagoc BF, Smith C, Sayo AR, Verona JA, Trifalgar-Arches J, Lazaro J, Balinas EGM, Telan EFO, Roy L, Galon M, Florida CHN, Ukawa T, Villaneuva AMG, Saito N, Nepomuceno JR, Ariyoshi K, Carlos C, Nicolasor AD, Solante RM. First covid-19 infections in the philippines: a case report. Trop Med Health. 2020; 48(30). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-020-00218-7 .

Macasero R. Coronavirus-free for 6 months, Siquijor reports first 2 cases. 2020. https://www.rappler.com/nation/siquijor-coronavirus-cases-august-2-2020 . Accessed Mar 2020.

Davao City. Mayor Sara, disaster radio journeying with dabawenyos. 2020. https://www.davaocity.gov.ph/disaster-risk-reduction-mitigation/mayor-sara-disaster-radio-journeying-with-dabawenyos . Accessed Mar 2020.

Davao City. Davao city free rides to serve GCQ-allowed workers. 2020. https://www.davaocity.gov.ph/transportation-planning-traffic-management/davao-city-free-rides-to-serve-gcq-allowed-workers/ . Accessed Mar 2020.

Download references

Acknowledgements

JFR is supported by the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics Associateship Scheme.

This research is funded by the UP System through the UP Resilience Institute.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Mathematical Sciences and Physics, University of the Philippines Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines

Dylan Antonio S. Talabis, Ariel L. Babierra, Christian Alvin H. Buhat, Destiny S. Lutero, Kemuel M. Quindala III & Jomar F. Rabajante

University of the Philippines Resilience Institute, University of the Philippines, Quezon City, Philippines

Faculty of Education, University of the Philippines Open University, Laguna, Philippines

Jomar F. Rabajante

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors are involved in drafting the manuscript and in revising it. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dylan Antonio S. Talabis .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable. We used secondary data. These are from the public database of the Philippine Department of Health ( https://www.doh.gov.ph/covid19tracker ) and Philippine Statistics Authority Census ( https://psa.gov.ph )

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

S. Talabis, D.A., Babierra, A.L., H. Buhat, C.A. et al. Local government responses for COVID-19 management in the Philippines. BMC Public Health 21 , 1711 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11746-0

Download citation

Received : 19 April 2021

Accepted : 30 August 2021

Published : 21 September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11746-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Local government

- Quantitative methods

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Journalism, public health, and COVID-19: some preliminary insights from the Philippines

Jan michael alexandre c bernadas, karol ilagan.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Jan Michael Alexandre C Bernadas, Department of Communication, De La Salle University, 2401 Taft Avenue, 1004 Manila, Philippines. Email: [email protected]

Issue date 2020 Nov.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ) which permits any use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access page ( https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage ).

In this essay, we engage with the call for Extraordinary Issue: Coronavirus, Crisis and Communication. Situated in the Philippines, we reflect on how COVID-19 has made visible the often-overlooked relationship between journalism and public health. In covering the pandemic, journalists struggle with the shrinking space for press freedom and limited access to information as they also grapple with threats to their physical and mental well-being. Digital media enable journalists to report even in quarantine, but new challenges such as the wide circulation of health mis-/disinformation and private information emerge. Moreover, journalists have to contend with broader structural contexts of shutdown not just of a mainstream broadcast but also of community newspapers serving as critical sources of pandemic-related information. Overall, we hope this essay broadens the dialogue among journalists, policymakers, and healthcare professionals to improve the delivery of public health services and advance health reporting.

Keywords: COVID-19, critical analysis of media and public health, journalism, Philippines, public health

Introduction

In this essay, we reflect on how COVID-19 has brought to our attention the often-overlooked relationship between journalism and public health. We draw initial insights from critical analysis of media and public health ( Henderson and Hilton, 2018 ) to suggest that health reporting in the country during the pandemic can be connected to journalistic practices, technological changes, and structural constraints. For journalism to advance public health, it needs to contend with the pandemic and the context into which it is uniquely situated – both of which are moving targets and difficult to predict. In this essay, we pay attention to the Philippines not just because it has one of the highest COVID 19-related cases and deaths in the world but also because the country is at the crossroads of changes in digital media and shrinking space for media freedom, as evidenced by the shutdown of the country’s biggest media network, closing or suspension of community newspapers, and passage of laws that may restrict free speech. In doing so, we hope to broaden dialogue among journalists, policymakers, and healthcare professionals to improve the delivery of public health services as well as advance health reporting.

Similar to other countries, the public health system in the Philippines was unprepared for and overburdened by COVID-19. The first case was reported on January 30 when a Chinese woman reached the country from Wuhan, China, and then a few days later her male companion died of the virus – making it the first recorded death outside of China ( Department of Health (DOH), 2020b ; Ramzy and May, 2020 ; World Health Organization (WHO), 2020a ). By March 7, the first case of local transmission was confirmed ( DOH, 2020a ; WHO, 2020a ). To date, there are 112,593 confirmed cases, 6,263 new cases, and 2,115 deaths in the country ( WHO, 2020b ) – making the Philippines as one of the most highly impacted in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific Region. Equally alarming is the number of doctors, nurses, and other hospital staff who get infected and die of COVID-19 ( CNN Philippines, 2020a ; McCarthy, 2020 ). Recently, professional medical and allied medical associations have called for a unified and calibrated response and temporary quarantine of the country’s capital to avoid a total collapse of the healthcare system ( Batnag, 2020 ). Critical but seldom discussed are the challenges of journalism in making sense of the rapid spread and devastating impact of COVID-19 in the Philippines and how the pandemic is also gradually transforming journalism in the country.

Journalism and public health work together to broaden health information sources, facilitate public understanding of health, and mobilize support for or against public health policy ( Henderson and Hilton, 2018 ; Larsson et al., 2003 ; Vercellesi et al., 2010 ) and this relationship is magnified during pandemics. The relationship between journalism and public health has mostly been explained based on journalistic roles and news framing. During the 2009 H1N1, for instance, Klemm et al. (2017) found that journalists shifted from ‘watchdogs’ to ‘cooperative’ roles. Holland et al. (2014) further argued that the 2009 H1N1 enabled journalists to be reflexive of their roles especially with conflicts of interest among experts and decision makers. News framing has likewise informed the conversations between journalism and public health. For example, Krishnatray and Gadekar (2014) found that fear and panic dominated the frames used by journalists in their news stories about the 2009 H1N1. In this essay, we hope to engage with ongoing discussion about journalism and public health by reflecting on how health reporting during COVID-19 in the Philippines relates to broader, emergent, and interconnected issues of journalistic practices, technological changes, and structural constraints in the country.

Reporting from home

COVID-19, along with the ensuing quarantines, poses challenges to existing journalistic practices that typically require fieldwork, but it also encourages journalists in the Philippines to reimagine news production. We observe that access to information has generally been limited because government offices have not been in full operation while virtual press briefings do not allow for a more open discussion between journalists and officials. To illustrate, Ilagan (2020) reported that most routine requests for information have not been processed since March 2020 when government offices were wholly or partly closed due to the ongoing quarantine. The Philippines is among many governments in the world that had to suspend the processing of freedom-of-information (FOI) requests because of the pandemic ( McIntosh, 2020 ). FOI officers working from home could not address requests because they lacked Internet connection, laptop computers, and scanners, including digital copies of files. They also found it difficult to coordinate remotely with record custodians. While some national agencies have been proactive in providing information on COVID-19, the same cannot be said for many local government units. Ilagan (2020) further noted that ‘[un]like frontline agencies at the national level, local governments do not proactively publish data on their websites’. Information about plans to combat the impact of the virus are usually available, but more prodding is needed to find out how these plans are being implemented and funded. Camus (2020) also reported that journalists were prohibited from covering what is happening in hospitals and other high-risk areas. More and more press briefings have thus taken place online, but reporters have found it harder to demand answers because officials and their staff often screen questions. For instance, Camus (2020) wrote that some questions from journalists were ignored while official reports from the government were consistently discussed.

Moreover, we observe that the pandemic has taken a toll on both the physical and mental well-being of journalists. Reported cases of journalists experiencing high levels of stress, undergoing self-quarantines, and at least one news anchor contracting the virus point to the need for broader safety measures at the organizational level of news outlets. The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) lamented the limited mental health support for journalists by saying that ‘there are hardly any readily available and sustained support systems for colleagues experiencing mental health issues’ ( Adel, 2020 ). Safeguarding the physical and psychological well-being of journalists during pandemics or any type of crisis does not rest on individuals alone but should be demanded from news organizations and advocated for by professional associations. Yet some journalists have been able to navigate the consequences of COVID-19 on the profession by reimagining newsgathering, taking advantage of online resources as well as doing collaborations.

First, journalists have been coping with the challenge of limited access to information by interviewing sources through phones and attending webinars with experts to learn more about the pandemic ( Tantuco, 2020 ). Bolledo (2020) said that journalists had to adapt in light of the global health crisis changing media operations. By adapting, he referred to Reuters’ approaches to comprehensive newsgathering, which focus on open-source and non-mainstream techniques such as ‘citizen and collaborative journalism’ and ‘social journalism’. In practice, this set of methods includes monitoring Facebook and Twitter feeds, joining Facebook groups created for a specific cause or geographical area, following hashtags and using keywording to find leads and sources. Bolledo (2020) also emphasized the need to fact-check information gathered using these methods, highlighting the importance of news values and the 5Ws and one H in reporting. Second, to address the barriers in online press briefings, journalists organized themselves to raise their unanswered questions in media group chats of government organizations ( Ilagan, 2020 ). Third, the NUJP organized peer support networks critical for minimizing stress and trauma among journalists who reported about and during COVID-19. Finally, in an effort to prevent contracting and spreading the virus among co-workers, journalists are maintaining records of their activities and a list of sources whom they interacted for purposes of contact tracing ( Camus, 2020 ). The new methods employed in health reporting, as creative responses to the constraints brought upon by COVID-19, partly illustrate how an emerging practice may turn into professional norm ( Henderson and Hilton, 2018 ) in health reporting during pandemic.

Double-edged sword

At the onset of COVID-19, journalism in the Philippines has struggled with ongoing technological changes that bring about double-edged consequences. On one hand, digital media has enabled journalists to help Filipinos make better sense of the pandemic – from reporting infections and deaths regularly to covering press conferences organized by agencies at the frontlines of COVID-19 response. Through Facebook live videos, Zoom , and other video conferencing applications, journalists are able to talk about their lived experiences in covering COVID-19. Various groups inside and outside of the Philippines have been hosting a series of webinars on how to cover the pandemic. Media groups in the Philippines meanwhile have also organized press briefings that tackle the state of news reporting in the country. In the forum titled ‘Intrepid Journalism in the Time of Corona’ organized by This Side Up Manila , two journalists discussed the state of news from the early stages of the pandemic to the declaration of enhanced community quarantine (ECQ). Early in the live video, they shared their frustrations about the consequences of COVID-19 on fieldwork and storytelling. According to the reporters, covering COVID-19 is different from reporting about natural disasters or conflict zones because they felt that there was no end in sight to the pandemic. As a result, they reminded themselves and their colleagues to find a balance and slow down as the pandemic may be prolonged and even put the lives of their families at risk. These webinars, which are in theory accessible to anyone in the world, also allow journalists to share their experiences with and learn from their counterparts in other countries. For instance, Hivos organized a webinar titled ‘Data Driven Reporting During Covid-19’ with journalists from the Philippines, Kenya, and Mexico to find out how they have been affected by and coping with the pandemic. The journalists said they have found collaboration or working with other journalists and members of the academe and civil society as key in reporting when fieldwork is not possible. Like the Philippines, too, Kenya and Mexico also experience barriers in accessing and reporting information while their governments too are also mandating policies that could restrict press freedom ( Hivos, 2020 ).

On the other hand, digital media has complicated the work of journalists as they had to deal with the spread of health mis- and/or disinformation. To partly explain the diffusion of online fake news (e.g. mass testing and vaccines), we engage with Tandoc et al. (2018) who emphasized the characteristics of technology and the role of audiences. For instance, social media made it challenging for journalists to delineate information sources from each other, especially given the evolving science of COVID-19. Because science is evolving, journalists tend to rely heavily on expert opinion, without verifying the experts’ assumptions. Correcting mis- and/ or disinformation about the pandemic was likewise difficult because journalists had limited understanding of what counted as fake news among Filipinos. Another problem that journalists had to contend with while working during the pandemic is the recent ‘data breach’ that used Facebook profiles of real people ( Robles et al., 2020 ). The rise of fake Facebook accounts is counterproductive not just to fight against health mis- and/or disinformation but also places the identities of journalists at risk. To a large extent, the proliferation of health mis- and/ or disinformation is inextricably connected to the social context not just of COVID-19 but also the Philippines. As Tandoc et al. (2018) pointed out, ‘fake news needs the nourishment of troubled times in order to take root. Social tumult and divisions facilitate our willingness to believe news that confirms our enmity toward another group’ (p. 149). While it created new issues, COVID-19 has also reinforced existing problems in the country and one of those is the shrinking space for free speech.

Shutdowns, suspensions, and shrinking spaces

The pandemic is also laying bare pre-existing conditions hounding the Philippine press in a supposed democracy. For instance, the government passed ‘The Bayanihan to Heal as One Act’ (Republic Act No. 11469) to give the president emergency powers that would enable him to quickly respond to COVID-19. Human rights and media advocates criticized this law as it included a provision penalizing ‘fake news’, which can easily be used and abused by those in power to file complaints against individuals, including journalists ( Freedom for Media, Freedom for All Network, 2020 ). Again this posed another challenge to journalists and the audience who both use social media as a means to get and share information. In similar vein, the passage of the ‘ Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 ’ (Republic Act No. 11479) received pushback for its broad provisions. Human rights groups also say that the law has essentially also criminalized intent, which could send a chilling effect especially among journalists who might be working on stories critical of the government.

On 5 May 2020, ABS-CBN, the country’s largest media network, went off-air after its broadcast franchise expired. The House of Representatives, which oversees the granting of franchises, refused ABS-CBN’s bid for a renewal, which ultimately led the media giant to close its broadcast operations and lay off thousands of employees. This development comes after the conviction of Rappler executive editor Maria Ressa and former researcher-writer Reynaldo Santos Jr for supposedly violating the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 (Republic Act No. 10175). The shutdown is seen as the latest in a series of attacks and threats against news organizations deemed as critical of the current administration ( Gutierrez, 2020 ; Pago, 2020 ). Community journalism is neither spared. At least half of some 60 community newspapers have suspended or ceased printing due to economic losses caused by the quarantine, according to estimates from the Philippine Press Institute, the national association of newspapers. The NUJP also raised economic difficulties confronting many freelance journalists, especially those who work on contract in broadcast, since the start of the lockdown. Suspension of operations means that contractual media workers would not be able to earn because work is not available. The halt in the production of news by ABS-CBN and various papers across the archipelago means that people, especially those in far-flung areas, have fewer sources of news at a time when getting information is most crucial. Again, these developments point to how pandemic reportage may be tied to political landscape in the country ( Henderson and Hilton, 2018 ).

COVID-19 is transforming the practice and business of journalism. On one hand, the pandemic and the ensuing quarantine restrictions have prompted news organizations and journalists to adapt and take advantage of digital media to continue gathering and presenting news. On the other hand, the pandemic has also exposed journalists and audiences alike to further mis- and/ or disinformation as well as to government’s new efforts to stamp out ‘fake news’. These developments run in parallel with threats to press freedom and journalist safety. In a pandemic, journalists are not mere observers or mere reporters as they also face the same risks everyone else is exposed to ( CNN Philippines, 2020b ). By laying out the current media environment in this essay, we hope to expand and deepen the conversation between and among journalists, policymakers, and healthcare professionals about public health reporting. In line with Larsson et al. (2003) , we encourage further conversations between journalists and healthcare professionals to collectively identify gaps in health reporting and broaden understanding of ‘fake news’ and how it thrives in social media. Consistent with Tandoc et al. (2018) , we also recommend that journalists and healthcare professionals listen to their audience to help understand what counts as health-related ‘fake news’ for them. Moreover, we invite policymakers to protect democratic spaces that enable journalists, healthcare professionals, and citizens alike to gather and share information related to COVID-19. At a time when disseminating reliable information and holding the powerful to account have never been more critical, we deem it necessary to understand where journalists are coming from to understand both the long-standing and emerging issues they have to grapple with in a pandemic.

Authors’ note: The views provided in this essay do not represent the official views of the authors’ institutional affiliations.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.