Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Ulcerative colitis articles within Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology

Review Article | 25 April 2024

Pouchitis: pathophysiology and management

Pouchitis is a common condition that can occur after intestinal surgery. In this Review, Shen discusses our current understanding of the multifactorial pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of pouchitis, primarily in patients with underlying ulcerative colitis.

Year in Review | 07 December 2023

Upgrading therapeutic ambitions and treatment outcomes

Important studies published in 2023 outlined new agents and strategies for the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Therapeutic ambitions for the management of inflammatory bowel disease were raised by the success of combinations of biologic agents in ulcerative colitis and early surgical resection in Crohn’s disease.

- Paulo Gustavo Kotze

- & Severine Vermeire

Review Article | 10 November 2023

Deciphering the different phases of preclinical inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease (IMID). Here, the authors review evidence on the preclinical phase of IBD, outlining and describing the proposed at-risk, initiation and expansion phases. Overlap with other IMIDs is discussed alongside the possible future directions for research into preclinical IBD.

- Jonas J. Rudbaek

- , Manasi Agrawal

- & Tine Jess

In Brief | 08 August 2023

Mirikizumab for inducing and maintaining clinical remission in ulcerative colitis

- Jordan Hindson

Perspective | 20 April 2023

The appendix and ulcerative colitis — an unsolved connection

The appendix is thought to have a role in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis but the association remains unclear. In this Perspective, the authors consider the biology of the appendix with respect to its immunological function and the microbiome, and how this relates to its possible involvement in ulcerative colitis.

- Manasi Agrawal

- , Kristine H. Allin

- & Jean-Frederic Colombel

In Brief | 07 March 2023

Two therapeutic antibodies better than one

Clinical Outlook | 27 January 2023

Positioning therapies for the management of inflammatory bowel disease

A careful integration of the effectiveness and safety of the therapies for inflammatory bowel disease, considering patients’ disease risks, treatment complications and preferences, is warranted to inform the positioning of therapies in clinical practice. Precision medicine might help choose the best option for an individual patient.

- Siddharth Singh

Comment | 19 December 2022

Risk minimization of JAK inhibitors in ulcerative colitis following regulatory guidance

The European Medicines Agency safety committee has revisited the label and recommended the use of Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with certain risk factors only if no suitable treatment alternatives are available. Although regulatory decisions are key to place therapeutic options based on safety, broad restrictions might lead to unintended consequences without an individualized benefit–risk evaluation.

- Silvio Danese

- , Virginia Solitano

- & Laurent Peyrin-Biroulet

Clinical Outlook | 16 September 2022

Medical therapy of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease

Antibodies targeting tumour necrosis factor have substantially advanced the treatment of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Understanding pharmacokinetics and therapeutic drug monitoring has led to increased efficacy and durability of response. Primary non-response is more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease, highlighting the need for alternative biologic agents and oral small molecules.

- Luca Scarallo

- & Anne M. Griffiths

Review Article | 07 December 2021

Revisiting fibrosis in inflammatory bowel disease: the gut thickens

Intestinal fibrosis is an important feature of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that remains poorly understood. Here, D’Alessio and Ungaro et al. review the cellular and molecular mechanisms contributing to intestinal fibrosis and discuss future therapeutic strategies for IBD-related fibrosis.

- Silvia D’Alessio

- , Federica Ungaro

- & Silvio Danese

In Brief | 01 October 2021

Ozanimod is efficacious in ulcerative colitis

- Katrina Ray

Journal Club | 20 September 2021

Inflammatory bowel disease and corticosteroids: the first RCT

- Fernando Gomollón

In Brief | 22 June 2021

Filgotinib for ulcerative colitis

Research Highlight | 04 May 2021

Intercrypt goblet cells — the key to colonic mucus barrier function

News & Views | 05 February 2021

IBD risk prediction using multi-ethnic polygenic risk scores

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has emerged as a global disease, yet identifying those at higher risk of developing IBD remains challenging. A new study highlights the use of a multi-ethnic polygenic risk score to determine risk of inflammatory bowel disease in a large primary care population.

- Ashwin N. Ananthakrishnan

Comment | 20 January 2021

SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in IBD: more pros than cons

Data on the efficacy and safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are now available, but evidence for these vaccines in those who are immunocompromised (including patients with inflammatory bowel diseases) are lacking. As vaccination begins, questions on advantages and disadvantages can be partially addressed using the experience from other vaccines or immune-mediated inflammatory disorders.

- Ferdinando D’Amico

- , Christian Rabaud

News & Views | 01 October 2020

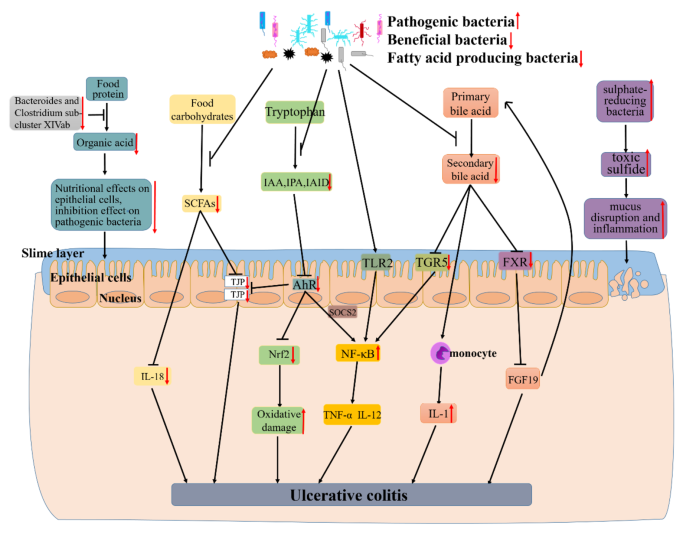

Environmental stimuli and gut inflammation via dysbiosis in mouse and man

A new study sheds further light on the interplay between environmental stimuli, the gut microbiota and intestinal inflammation. Identification of modifiable environmental triggers and the mechanisms by which they act has implications for the prevention and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease.

- Charlie W. Lees

Research Highlight | 03 September 2020

Deciphering the role of CD8 + T cells in IBD: from single-cell analysis to biomarkers

Research Highlight | 21 January 2020

Shining a spotlight on somatic mutations in ulcerative colitis

Research Highlight | 15 October 2019

New trials in ulcerative colitis therapies

- Iain Dickson

Comment | 13 September 2019

Evolving therapeutic goals in ulcerative colitis: towards disease clearance

In ulcerative colitis, treating beyond endoscopic healing has shown a reduction of relapse and hospitalization, pushing for histological remission to be embraced in clinical practice and clinical trials. Here, we propose the concept of disease clearance (symptomatic, endoscopic and histological remission) as the ultimate goal in the treatment of ulcerative colitis.

- , Giulia Roda

In Brief | 29 March 2019

Gut mucosal virome altered in ulcerative colitis

News & Views | 08 March 2019

FMT for ulcerative colitis: closer to the turning point

A new study shows that a sustainable faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) treatment protocol, including anaerobic sample preparation, induces remission of active ulcerative colitis. The promising results are another piece in the puzzle, but it is not yet possible to draw conclusions and implement the procedure in clinical practice.

- Giovanni Cammarota

- & Gianluca Ianiro

In Brief | 06 April 2018

Autofluorescence inferior for dysplasia surveillance

In Brief | 02 November 2017

The changing epidemiology of IBD

Review Article | 11 October 2017

Environmental triggers in IBD: a review of progress and evidence

A wide variety of environmental triggers have been associated with IBD pathogenesis, including the gut microbiota, diet, pollution and early-life factors. This Review discusses the latest evidence and progress towards better understanding the environmental factors associated with IBD.

- , Charles N. Bernstein

- & Claudio Fiocchi

Review Article | 19 July 2017

Gut microbiota and IBD: causation or correlation?

Changes in the composition and metabolic function of the gut microbiota have been linked to IBD, but a direct causal association has yet to be established in humans. This Review discusses the evidence supporting dysbiosis in the gut microbiota in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, exploring evidence from animal models and the translation to human disease.

- Josephine Ni

- , Gary D. Wu

- & Vesselin T. Tomov

In Brief | 14 June 2017

Phase II trial success for anti-MADCAM1 antibody

Research Highlight | 17 May 2017

Tofacitinib effective in ulcerative colitis

- Conor A. Bradley

Research Highlight | 01 March 2017

FMT induces clinical remission in ulcerative colitis

- Hugh Thomas

News & Views | 07 December 2016

Mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis: what constitutes remission?

Patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission are increasingly undergoing colonoscopies to determine endoscopic remission. However, the histological evaluation of biopsy samples provides additional criteria to predict which patients are most likely to undergo relapse, so what is the ideal therapeutic end point for patients with ulcerative colitis?

- Robert H. Riddell

Research Highlight | 05 October 2016

A role for GATA3 in ulcerative colitis

Review Article | 01 September 2016

Acute severe ulcerative colitis: from pathophysiology to clinical management

Acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC) is a potentially life-threatening condition that occurs in ∼20% of patients with ulcerative colitis. Here, the authors provide an overview of ASUC from pathophysiology to clinical management (including drug therapy and surgery).

- Pieter Hindryckx

- , Vipul Jairath

- & Geert D'Haens

In Brief | 13 July 2016

Treatment for acute severe ulcerative colitis

- Isobel Leake

News & Views | 05 May 2016

Vitamin D and IBD: moving towards clinical trials

A new study reports that low vitamin D levels are associated with increased morbidity and severity of IBD. A number of issues must now be addressed to enable the optimal design of interventional studies to test whether vitamin D supplementation can improve outcomes in this disease.

- Margherita T. Cantorna

In Brief | 17 February 2016

CT-P13: a safe and effective treatment for IBD

Research Highlight | 24 December 2015

Maintaining the mucosal barrier in intestinal inflammation

In Brief | 18 November 2015

Who benefits the most from etrolizumab in ulcerative colitis?

In Brief | 08 September 2015

Gel-based drug delivery for IBD hits the target

In Brief | 21 April 2015

Faecal transplant from donors no more effective than autologous transplant for treating ulcerative colitis

News & Views | 15 July 2014

Sequential rescue therapy in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis

Treatment of patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis is still a challenge for physicians. A recent study has evaluated the effectiveness and safety of sequential rescue therapies in this subgroup of patients.

- Paolo Gionchetti

- & Fernando Rizzello

Research Highlight | 24 June 2014

T H 9 cells might have a role in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis

In Brief | 17 June 2014

Phase II study reveals potential of etrolizumab as induction therapy for ulcerative colitis

Research Highlight | 22 April 2014

Mouse model reveals how appendicitis protects against ulcerative colitis

- Claire Greenhill

Research Highlight | 18 March 2014

EUS can differentiate Crohn's disease from ulcerative colitis

- Natalie J. Wood

News & Views | 04 March 2014

Which makes patients happier, surgery or anti-TNF therapy?

Quality of life and disability have been compared in patients with ulcerative colitis who were undergoing one of the two current major treatments of choice, proctocolectomy or anti-TNF therapy. The only significant differences between the two groups were increased use of antidiarrhoeal medication and stool frequency in those who underwent surgery.

- Taku Kobayashi

- & Toshifumi Hibi

Review Article | 07 January 2014

Tailoring anti-TNF therapy in IBD: drug levels and disease activity

Despite the proven and often clinically marked efficacy of anti-TNF drugs for IBD, these biologic agents are not immune to treatment failures. Tailoring anti-TNF treatment in IBD mandates considerations of the different clinical scenarios in which therapy failure might occur while bearing in mind an opposite group of patients in whom intensive therapy might be unnecessary.

- Shomron Ben-Horin

- & Yehuda Chowers

In Brief | 17 September 2013

Induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis—vedolizumab more effective than placebo

News & Views | 13 August 2013

Activity of IBD during pregnancy

Women worry that their IBD will flare during pregnancy. A prospective multicentre study from Europe has now demonstrated that although women with Crohn's disease do not have an increased risk of relapse during pregnancy, women with ulcerative colitis are at increased risk of relapse, both during pregnancy and postpartum.

- Sunanda Kane

News & Views | 30 July 2013

Golimumab in ulcerative colitis: a 'ménage à trois' of drugs

Golimumab, a human anti-TNF antibody, is effective in patients with ulcerative colitis, according to new findings from an international phase III double-blind trial. The addition of this drug makes a ménage à trois of available drugs—comprising infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab—for the treatment of ulcerative colitis.

Browse broader subjects

- Inflammatory diseases

- Inflammatory bowel disease

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Drugs Context

New developments in ulcerative colitis: latest evidence on management, treatment, and maintenance

Kartikeya tripathi.

1 Department of Medicine, St Vincent Hospital, Worcester, MA, USA

Joseph D Feuerstein

2 Department of Medicine and Division of Gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic idiopathic inflammatory disorder that involves any part of the colon starting in the rectum in a continuous fashion presenting typically with symptoms such as bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and rectal urgency. UC is diagnosed based on clinical presentation and endoscopic evidence of inflammation in the colon starting in the rectum and extending proximally in the colon. The clinical presentation of the disease usually dictates the choice of pharmacologic therapy, where the goal is to first induce remission and then maintain a corticosteroid-free remission. There are multiple classes of drugs that are available and are used based on the clinical severity of the disease. For mild-to-moderate disease, oral or rectal formulations of 5-aminosalicylic acid are used. In moderate-to-severe UC, corticosteroids are usually used in induction of remission with or without another class of medications such as thiopurines or biologics including anti-tumor necrosis factor, anti-integrins, or Janus kinase inhibitors for maintenance of remission. Up to 15% of the patients may require surgery as they fail to respond to medications and have risk of developing dysplasia secondary to longstanding colitis.

Introduction

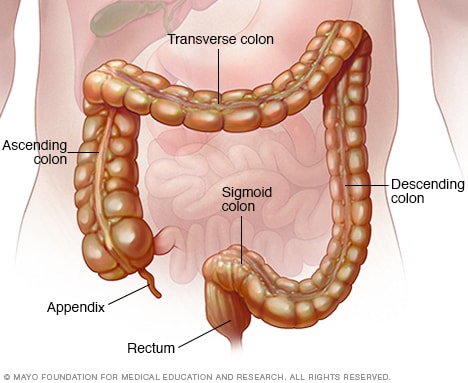

Ulcerative colitis (UC) was first described in mid-1800s. 1 It is an idiopathic, chronic inflammatory disorder of the colonic mucosa that commonly involves the rectum and may extend in a proximal and continuous fashion to involve other parts of the colon. 2 The disease typically affects individuals in the second or third decade of life with hallmark clinical symptoms of bloody diarrhea and rectal urgency with tenesmus. 3 , 4 The clinical course is marked by exacerbations and remissions, which may occur spontaneously or in response to treatment changes. 5 , 6 There are multiple drug classes discussed in this review that can be used to treat acute exacerbation of the disease and for maintenance of remission. However, even with medical therapy, up to 15% of patients will require surgery to treat UC or disease complications of dysplasia.

Overall, the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has traditionally been highest in North America and Western Europe with increasing incidence in the mid-20th century. However, incidence of IBD is increasing in emerging populations in continental Asia. 7 , 8 In North America, the incidence of UC is 2.2–14.3 cases per 100,000 persons per year, and its prevalence is 37–246 cases per 100,000 per year. 7 The exact pathogenesis of the disease is not well understood but there are genetic factors that are attributed to the risk of developing the disease accompanied by epithelial barrier defects and environmental factors. Currently, a number of genetic and environmental factors that increase the risk of developing UC are identified. 9 A westernized lifestyle and diet including cessation of tobacco use, fatty diet, stress, and medication use and high socioeconomic status are all associated with the development of IBD. 10 Among many such factors, tobacco smoking and appendectomy are linked to milder disease, fewer hospitalizations, and decreased incidence of UC but the reverse is true for Crohn’s disease. 11 , 12

The diagnosis of UC is based on the clinical presentation and symptoms consistent with the disease and findings on colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy showing continuous colonic inflammation starting in the rectum. Pathologic findings of chronic colitis confirm the diagnosis.

Disease approach, assessment of clinical severity, and disease management

Initial treatment is based upon disease severity and extent. Patients can present with mild, moderate, or severe disease – stratification based on clinical severity is used to guide medical and pharmacologic management. The goals of treatment are induction of remission followed by maintenance of remission in conjunction with steroid-free treatments in the long-term management. 6 Historically, the Truelove and Witts criteria are utilized to stratify patients with mild, severe, or fulminant colitis ( Table 1 ). Patients categorized as having mild clinical disease have less than four stools per day with or without blood with no signs of systemic toxicity. Mild crampy abdominal pain and tenesmus are common clinical symptoms. In moderate–severe disease, patients have abdominal pain, frequent loose bloody stools (typically more than four per day), and mild anemia not requiring blood transfusions. They also have minimal signs of systemic toxicity such as low grade fever. In contrast, patients with fulminant disease present with over six loose bloody stools with severe abdominal cramps and systemic toxicity such as fever or tachycardia. They also have manifestations such as anemia or an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)/c-reactive protein (CRP). In addition to assessing patients with the Truelove and Witts criteria, the colon should be evaluated endoscopically either with a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, depending on the clinical presentation and any validated score such as Mayo Endoscopy score or Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) should be utilized 13 ( Tables 2 and and3). 3 ). The endoscopic Mayo score classifies disease as mild, moderate, or severe based on the erythema, erosions, ulcers, and/or severe friability. The management of severe and fulminant clinical disease differs from that of mild-to-moderate disease. Historically, step-up therapy was used for treating any flare ups of UC. However, recent evidence suggests a top down approach using effective therapy such as anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) often with immunomodulator to control severe disease; thus, patients with severe clinical disease on presentation may be treated with biologics early on as opposed to use of mesalamines that are effective only in mild-to-moderate disease.

Truelove and Witts’ severity index.

Adapted from Sturm et al. 13

Endoscopic Mayo score.

UCEIS (Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity) descriptors and definitions.

Mild-to-moderate disease

5-aminosalicylate.

There are multiple 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) compounds available. One of the first drugs available was sulfasalazine. Sulfasalazine is a prodrug that is partially absorbed in the jejunum and passes to the colon where it is reduced by coliforms to sulfapyridine and its active form, 5-ASA. 14 5-ASA is primarily responsible for efficacy of sulfasalazine. Other 5-ASA products (i.e. mesalamine) are formulated to release in the colon via a number of different mechanisms including both bacterial-mediated release and pH-mediated release. In azo-bond prodrug, the mesalazine is synthesized as a prodrug binding via an azo-bond to a transport molecule. Due to the presence of an azo-bond, it is not absorbed in the upper gastrointestinal tract. The bond is subsequently cleaved by bacterial action in the colon by azoreductase, releasing the active mesalazine component of the drug. In pH-mediated release formulations, the active drug is encapsulated in an enteric coating to control the site of drug release. Other available formulations include time-dependent release, which consists of microspheres of mesalazine encapsulated within a semipermeable membrane that produces time and moisture-dependent release of active drug. Although the different release mechanisms may be of benefit for certain patients, the recent American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) guidelines on mild-to-moderate UC do not suggest changing mesalamine based on release formulation in someone who is not responding adequately to the initial mesalamine release mechanism. 15

The dosing per pill is variable but in general, these medications can be taken once a day or in twice daily regimens. The initial approach for mild-to-moderate disease is to start oral and topical 5-ASA. Oral 5-ASA is started at a full-strength dose of 4.8 g/day for induction of remission. Over time, this can be reduced to a maintenance dose of 2.4 g/day. In patients who have not achieved remission on oral therapy, combining oral and rectal therapy is more effective in inducing remission. 16 – 18

In patients with more limited disease of the rectum and/or sigmoid colon, some patients may opt for only topical rectal treatments and defer oral therapy due to cheaper costs, quicker response time, and typically requiring lesser frequent dosing when compared to oral therapy. However, if the patient fails to respond to topical therapy, then oral therapy should be added to the regimen. Topical therapy with 5-ASA can be given via suppository or enema. 19 – 21

In left-sided colitis and pancolitis, combination therapy has proven to be more effective in achieving remission and its maintenance than isolated oral therapy or isolated topical therapy. 22 In general, 5-ASA drugs start working within 2–4 weeks and they show response in up to 80% of patients (when selected appropriately). 19 Once remission is achieved, patients are continued on the drug for maintenance therapy. Given the safety of the drug and lack of any dose-dependent side-effect profile, some practitioners opt to keep patients on the 4.8 g/day dose while others will lower the dose to 2.4 g/day when dosing for maintenance. There are no data to support doses that are less than 2.4 g/day, and these doses should be avoided. 15

In patients with only mild-to-moderate disease who fail to respond to mesalamine, one can consider adding a steroid-containing foam or enema in combination with 5-ASA therapy. 23 In patients who have an inadequate response to the combination of oral 5-ASA and topical 5-ASA/steroids in 2–4 weeks, the budesonide multimatrix (MMX) formulation can be considered. 24 , 25 Although these steroid formulations are relatively safe given their lack of systemic absorption, they are not as effective as oral prednisone. The initial study importantly compared budesonide MMX to mesalamine and not prednisone. 26 Additionally, none of these steroid formulations are approved for long-term maintenance of remission. 15

Although side effects can happen with both sulfasalazine and 5-ASA, sulfasalazine appears to have a wider range of more serious adverse events. Both anemia and abnormal liver tests are associated with sulfasalazine use and, to that end, patients should have routine complete blood counts (CBC) and liver function tests (LFTs) checked while on sulfasalazine. Additionally, to reduce the risk of anemia, patients should take folic acid 1 mg daily. Other side effects include nausea, headaches, fevers, and rash. Headaches and nausea are often dose dependent but slow titration of the dose can minimize these issues. However, sulfasalazine should be discontinued if the patient experiences idiosyncratic drug reactions such as skin rash, pancreatitis, pneumonitis, and agranulocytosis, and the patient should not be rechallenged. Approximately, 25% of patients stop using sulfasalazine due to its broader side-effect profile compared to mesalamine.

In contrast, mesalamine is a very safe and effective medication. It is extremely rare to develop any side effects on the drug. Up to 3% of patients may experience paradoxical worsening of diarrhea, and stopping the drug may be helpful. 27 Interstitial nephritis is a very rare side effect occurring in less than 0.2% of cases. Routine monitoring of kidney function is recommended to screen for interstitial nephritis. 28

Oral budesonide and rectal budesonide formulations carry little to no risk. Rectal budesonide foam was more efficacious in inducing remission in patients when compared to placebo. 29 Studies show that there is a small change in systemic cortisol levels, but classic steroid-related side effects are not seen with these drugs. There are case reports of steroid-related side effects with oral budesonide when used in high doses for long term. 30

Moderate-to-severe disease

Systemic corticosteroids are typically given first line for induction of remission in cases of moderate-to-severe disease. Oral steroids are used in most cases, but in up to 15% of patients, the disease may present as acute severe ulcerative colitis necessitating hospitalization and intravenous steroids. 31 Steroids are used in the acute inflammatory phase of the disease to assist with induction of remission but should always be bridged with a steroid-sparing agent for a goal of long-term steroid-free maintenance of remission. 6 Intravenous or oral steroids should never be used for long-term therapy as they are associated with a myriad of irreversible side effects such as weight gain, cataracts, osteoporosis, hypothalamic pituitary axis suppression, and immunocompromised state. Several classes of drugs can be used for maintenance of remission including thiopurines, anti-TNF agents, anti-integrins, and Janus kinase inhibitors that are discussed in detail in this review.

Corticosteroids

As stated earlier, corticosteroids are only used for induction of remission. Oral prednisone is usually the first choice of treatment at a dose of 40–60 mg daily. 6 Higher doses have not been shown to be more effective. In most patients, oral steroids are useful for induction of remission; however, if symptoms do not respond adequately, intravenous steroids should be used and the patient should be hospitalized. 32 These patients are at risks of developing complications, and close monitoring in the hospital setting is recommended. Intravenous methylprednisone is usually preferred at a dose of 40–60 mg daily (e.g. 20 mg every 8 hours) over intravenous hydrocortisone that may cause sodium retention. 31 Approximately two-thirds of the patients respond to this treatment. There are no specific recommendations for tapering the steroid dose, but it is advised to transition to an oral prednisone dose of 40–60 mg daily until significant clinical improvement occurs and then taper with a dose of 5–10 mg weekly until a dose of 20 mg is reached, then a tapering of 2.5–5 mg every week is advised. 6 , 33

If there is no meaningful response to the intravenous steroids in acute severe disease within 3–5 days as determined by the Oxford index, steroid-refractory disease should be considered and rescue therapy with other therapeutic entities – either infliximab or cyclosporine – should be initiated. 34

Steroids are very effective in inducing remission but have a number of adverse effects. In addition, they are ineffective in maintaining remission. 35 The frequency and severity of steroid toxicity are substantial and may involve virtually any organ system and many of these complications are irreversible 6 , 36 such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, cataracts, glaucoma, depression, anxiety, insomnia, irritability, and avascular necrosis. Additionally, the risks of opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease patients using steroids are increased three-fold and are more common over the age of 50 years. 6 , 37 The risks are increased synergistically when steroids are used concomitantly with other immunosuppressive therapies such as infliximab or thiopurines. 37

Thiopurines

Thiopurines (azathioprine [AZA] and 6-mercaptopurine [6-MP]) have a steroid-sparing effect and are used for maintenance of remission when steroids are withdrawn. Thiopurines have no role for induction of remission. AZA and 6-MP are slow-acting medications, and it can take 3 months before therapeutic concentrations are achieved. Hence, a longer course of steroids is often required until the pharmacologic effect of thiopurines is exerted.

AZA and 6-MP have multiple side effects where leukopenia and elevation in transaminases are the most common. These are dose-dependent side effects of the medication and are typically related to the activity of thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) enzyme. These adverse effects occur in 10% of the patients and usually in the first month of therapy. 38 It is recommended to monitor CBC and LFTs in patients on treatment with thiopurines frequently when first starting the drug and then periodically thereafter. Given that there is a small risk of mortality secondary to severe leukopenia and infections, the current guidelines recommend testing for TPMT enzymatic activity before starting thiopurines. 39 – 41 Another limiting side effects is intractable nausea. There is 0.3% of the population with homozygous mutations for TPMT, and they have negligible enzyme activity. In these cases, one should avoid using a thiopurine. If the enzymatic activity is intermediate, the starting dose should be reduced by 25–50%. 39 , 42

Thiopurines are also associated with an increased risk of malignancy. There is a risk of non-melanoma skin cancer, and an annual skin exam is advisable to mitigate this risk. Patients should be advised to wear sunscreen and avoid prolonged exposures to the sun. Additionally, there is also an increased risk of lymphoma in patients treated with thiopurines. The incidence is small and is quantified as 1 in 1000-person years. 43 The risk of developing lymphoma is most pronounced in patients with negative Epstein Barr virus at the time drug is initiated, and it is advised to not use thiopurines in these patients. 44 Use of thiopurines over 2 years appears to be a common denominator in cases of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphomas. This is particularly significant in young men under the age of 35. 45

Other nonspecific side effects include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and pancreatitis. Most of these side effects aside from the pancreatitis are self-limited and often dissipate over time. In cases of pancreatitis, however, the drug should be stopped and not reinstituted.

Anti-TNF agents (infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab)

Different from thiopurines, anti-TNFs can be used for both induction and maintenance of remission. 46 , 47 They are most often used with corticosteroids to induce remission. 48 The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) recommend the use of infliximab for induction of remission in patients with glucocorticoid-refractory or glucocorticoid-dependent disease. 6 , 49 The recommendations also suggest use in patients with severe disease where standard treatment has failed or is not responding to high-dose steroids in hospital. 6 There are three anti-TNF agents that are approved to be used in moderate-to-severe UC: infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab. 46 , 50 , 51

Infliximab is a chimeric (combination of human and murine) IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds with affinity to TNF-ά and neutralizes its biologic activity. 52 Adalimumab and golimumab are 100% human antibodies. There are several clinical trials on infliximab evaluating its efficacy and its use in UC. 50 The number-needed-to-treat is four to induce one case of remission. 53 All anti-TNF agents are effective, with infliximab being slightly more efficacious than adalimumab with regard to inducing a clinical response or mucosal healing, but these results are not well established. 54 Infliximab is an infusion that is typically infused over 2 hours. In contrast, both adalimumab and golimumab are subcutaneous injectables. All of these agents are effective for induction and maintenance of remission in UC. However, only infliximab dosing is weight based and has efficacy in acute severe UC refractory to intravenous steroids. 55

Anti-TNF agents are safe but there are many recognized adverse effects associated with them, which can be minimized by preinitiation testing and careful monitoring after starting the treatment. Injection site reactions are seen in less than 10% of the patients and these reactions are usually mild. Infusion reactions with infliximab can be acute or delayed. Acute reactions occur in the first 24 hours of infusion. True anaphylaxis (IgE mediated) may occur in some patients; however, in most patients it is nonallergic or an anaphylactoid reaction. 56 , 57 If allergic reaction is suspected, the drug should be discontinued, and the patient should not be rechallenged with infliximab.

The most common significant side effect of anti-TNF agents are infections. Most infections are mild, such as common cold, otitis media, and sinusitis. However, these patients are at increased risk of developing serious infections due to their immunocompromised state. All patients must undergo tests to eliminate latent tuberculosis (TB) and chronic hepatitis B infection before starting therapy as both are at increased risk of reactivation if found to be latent in the patient. 58 There are numerous rare side effects associated with anti-TNF therapy. One of the rare but more commonly seen side effects is the nonspecific elevation of liver enzymes. The elevated liver enzymes can be a reaction to the infliximab itself and considered a drug reaction that should reverse with cessation of the drug, but a second condition potentially brought out by infliximab is autoimmune hepatitis that may or may not be directly related to the infliximab. Often in this scenario, the condition persists even with cessation of the infliximab. 59 Periodic testing of liver function tests is recommended. Liver enzymes usually tend to normalize once the drug is discontinued. Although rare, there are case reports of acute liver failure requiring liver transplantation with the use of infliximab. 60

The risk of cancer with anti-TNF therapy is debatable. There appears to be an increased risk of melanoma skin cancer, and a yearly skin exam is advisable. There is conflicting evidence about increased risks of lymphoma; therefore, there are no specific screening recommendations for this while on anti-TNF therapy.

Anti-TNF agents can take up to 6–12 weeks to achieve initial response and mucosal healing. Therapeutic drug monitoring is the new standard of care in treatment of IBD patients. In addition, all anti-TNF agents have risks of developing antibodies altering its efficacy. 61 Hence, checking drug levels and levels of antibodies may allow tailoring of drug dosage or choice of medication to achieve a clinical response or remission. 61 , 62

Calcineurin inhibitors

Cyclosporine has a role in induction of remission in severe-to-fulminant steroid-refractory colitis. Although there are some limited data for the use of tacrolimus, they are not recommended for typical use. Cyclosporine is used as a rescue therapy at select IBD centers, but it does not have a role for long-term therapy. Transition to oral cyclosporine from a continuous infusion is typically performed after patients show response to intravenous cyclosporine. When transitioning to oral cyclosporine, patients are also started on a long-term maintenance plan consisting of thiopurines or anti-integrins. 6 The oral cyclosporine is usually discontinued within 3 months. Even though, over 60% of patients with severe UC respond to intravenous cyclosporine, most will still ultimately require colectomy in 5–7 years. 63

Cyclosporine is administered as a continuous infusion at a dose of 2–4 mg/kg per 24 hours. As studies show similar efficacy and lesser toxicity with the lower dose of 2 mg/kg, many clinicians start with this dose. 64 , 65 It is recommended to maintain intravenous use of glucocorticoids in these patients. Because of the extent of immunosuppression given the steroids, cyclosporine, and a long-term maintenance drug, prophylaxis against pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) is recommended.

Conversion from the continuous infusion of cyclosporine to oral cyclosporine should be sought early in the course of treatment once a patient shows adequate response to the intravenous dose. Blood levels of cyclosporine should be checked every day to every alternate day with goal levels ranging between 200 and 400 ng/mL in doses 2–4 mg/kg, respectively. Doses can be adjusted based on efficacy and toxicity and rounded off to nearest 25 mg to aid oral conversion, which is calculated by doubling the intravenous dose that led to resolution of symptoms and is administered 12 hours apart. Trough levels are checked before the fourth dose. Levels of 200–300 ng/mL are optimum as levels that are less than 200 ng/mL are associated with loss of response. 66

Patients receiving intravenous cyclosporine should show initial response in 2–3 days of starting treatment, evidenced by clinical resolution of symptoms of abdominal pain, blood in stool, and may have formed stools with normalization of laboratory tests. Before transitioning to oral cyclosporine, patients should be able to tolerate an oral diet. In patients who fail to show resolution of symptoms of severe disease in 72 hours, Clostridioides difficile should be tested and treated if positive. Unfortunately, patients failing to respond within 72 hours likely will need a colectomy.

Patients responding to intravenous cyclosporine and successfully transitioned or oral cyclosporine can be discharged on oral cyclosporine, oral steroids, a long-term steroid sparing drug (e.g. thiopurine or anti-integrin) and PCP prophylaxis with a tapering regimen of steroids over the 4–6 weeks followed by tapering of oral cyclosporine over the ensuing 3 months. Patients who cannot get off steroids should be evaluated for surgery.

Adverse effects are common with use of cyclosporine and sometimes, life threatening. Patients must be monitored for electrolyte abnormalities like hyperkalemia and hypomagnesemia. Nephrotoxicity is a common side effect and is usually reversible after discontinuation of the drug. Neurotoxicity may manifest as mild tremor or sometimes, severe headache, visual abnormality or seizures. 67 Calcineurin-inhibitor pain syndrome is characterized by symmetrical pain in feet and ankles. Symptoms may improve once the drug is stopped or by use of calcium channel blockers. 68

Anti-integrins

Integrins are proteins that regulate migration of leucocytes to the intestines. Vedolizumab is a fully humanized recombinant monoclonal antibody that binds to alpha4–beta7 integrin and prevents migration of leucocytes to the gut. Vedolizumab has shown to be effective and is approved for use to induce and maintain remission in moderate-to-severe active UC. 69 , 70 It is the first anti-integrin approved for use in UC. The initial therapeutic response is usually seen in 6 weeks of treatment, but it can take up to 6 months for the full maximal benefit to be seen.

With regard to safety, vedolizumab is the safest biologic available with minimal side effects such as intestinal infections – attributed to its mechanism of action that is very gut therapeutic. 71 There is a small theoretical risk of developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), which is a viral infection of the brain resulting in severe disability and death and has been associated with the use of anti-integrins. However, in the initial studies there are no reported cases of PML with vedolizumab. 71 , 72 Upper respiratory tract infections are the most common infections in patients on treatment with vedolizumab. There is no increased incidence of abdominal infections and lower respiratory tract infections with vedolizumab when compared to placebo. 71 Infusion-related reactions are also identified as an adverse event of vedolizumab with an incidence of <5% with most of these reactions being mild to moderate. 71 , 72 These are mostly self-limiting and do not usually require the discontinuation of the drug.

Tofacitinib

Tofacitinib is a Janus kinase inhibitor and was recently licensed in 2018 for treatment of moderate-to-severe active UC. 73 The timing and decision to use is similar to that of anti-TNFs or vedolizumab. It is indicated for treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe UC, but it is not recommended for use in combination with other biologics or potent immunosuppressants such as a thiopurine or calcineurin inhibitor. 73 A decision to start treatment with tofacitinib should be based on the patient’s compliance with drug therapy and comfort with the drug’s adverse events profile. In the United States insurance coverage and costs also need to be considered. Initial drug response can be seen in 6 weeks.

Tofacitinib is the first oral formulation of a small molecule that is taken twice a day. It is available in doses of 5 mg and 10 administered twice a day. The lowest effective dose should be used to maintain the response. If adequate therapeutic benefit is not achieved after 16 weeks of 10 mg twice a day dosing, it must be discontinued. Dose adjustment is required in moderate-to-severe renal impairment and it is recommended to cut down to a half-daily dose compared with the dose given to patients with normal renal function. It is not recommended to use tofacitinib in patients with severe hepatic impairment. Half-dosing should also apply to those patients receiving concomitant CYP 3A4 inhibitors such as ketoconazole. 73

Adverse effects of tofacitinib are similar to anti-TNF agents. 74 Serious and sometimes fatal infections due to bacterial, mycobacterial, invasive fungal, viral, or other opportunistic pathogens have been reported in the clinical trials with tofacitinib. 73 Patients with UC on 10 mg twice daily were associated with a greater risk of serious infections compared with those on 5 mg twice daily. Additionally, opportunistic herpes zoster infections including meningoencephalitis, ophthalmologic, and disseminated cutaneous were seen in patients on 10 mg twice daily. 73 To mitigate the risk of zoster activation, it is recommended that these patients should be vaccinated against zoster.

Before starting tofacitinib, patients should be evaluated and tested for latent or active TB. In patients who are tested positive for latent TB, it is recommended to consult an infectious disease specialist to whether or not to initiate anti-TB therapy before starting the treatment with tofacitinib. Other side effects include neutropenia and it is recommended that patients should undergo episodic checking of a CBC with differential. It is also associated with an increase in liver enzymes of up to three times the upper limit of normal. Reduction of dose of tofacitinib in these patients resulted in normalization of liver enzymes. 75

UC is a chronic inflammatory condition where medications are used to induce remission and maintain a steroid-free remission. Up to 15% patients may require colectomy due to inability to control the disease. The choice of medication depends upon the clinical stage of the disease. Contrary to the historical treatment paradigm of a bottom-up versus top-down strategy, now the recommendation is to treat the underlying severity of disease with medications that are most appropriate for that level of disease severity. In cases of mild-to-moderate disease severity, mesalamine is preferred as it is the safest available drug for the management of UC with a 0.2% risk of interstitial nephritis. However, if the disease is not responding adequately to mesalamine or if the disease is categorized as moderate-to-severe, then one should utilize immunosuppressants, and biologics including anti-TNF, anti-integrin, or a small molecule Janus kinase inhibitors. Thiopurines including azathioprine and mercaptopurine have been utilized for decades in the management of UC, but they only have a role in maintenance of remission and can take up to 3 months to achieve efficacy. In contrast, anti-TNF medications including infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab all have efficacy for induction of remission and maintenance of remission. The drugs are fairly equivalent, but infliximab has greater bioavailability, as it is administered intravenously, and can be dosed based on one’s weight. These drugs have side effects from the immunosuppression but no more than a thiopurine. The safest available biologic is vedolizumab that is a gut-specific anti-integrin. Given its gut specificity it does not carry many side effects. The newest group of drugs is the small molecule Janus kinase inhibitors. Tofacitinib is an oral pill taken twice a day that is likely to be quite desirable to patients given the mode of administration. However, it still retains a side-effect profile that is equal to, or more significant than, anti-TNF medications. All of these drugs should be considered in the appropriate setting based on the severity of the UC. Most importantly, though, no patients should be left on long-term corticosteroids.

Acknowledgements

Contributions: Both authors contributed equally to the preparation of this review. The authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosure and potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) Potential Conflicts of Interests form for the authors are available for download at http://www.drugsincontext.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/dic.212572-COI.pdf

Funding declaration: There was no funding associated with the preparation of this article.

Correct attribution: Copyright © 2019 Tripathi K, Feuerstein JD. https://doi.org/10.7573/dic.212572 . Published by Drugs in Context under Creative Commons License Deed CC BY NC ND 4.0.

Article URL: https://drugsincontext.com/new-developments-in-ulcerative-colitis:-latest-evidence-on-management,-treatment,-and-maintenance

Provenance: invited; externally peer reviewed.

Peer review comments to author: 8 January 2019

Drugs in Context is published by BioExcel Publishing Ltd. Registered office: Plaza Building, Lee High Road, London, England, SE13 5PT.

BioExcel Publishing Limited is registered in England Number 10038393. VAT GB 252 7720 07.

For all manuscript and submissions enquiries, contact the Editor-in-Chief [email protected]

For all permissions, rights and reprints, contact David Hughes [email protected]

- Our Ambition, Purpose, & Values

- Executive Leadership Team

- Board of Directors

- Our Locations

- Gastrointestinal

- Dermatology Products/Aesthetics Devices

- International Pharmaceuticals

- Generics, Neurology and Other

- Vision Care

- U.S. Product List

- Our Pipeline

- U.S. Health Care Compliance Policy

- Declaration of Compliance

- Misconduct Reporting Mechanisms

- Auditing, Monitoring and Risk Assessments

- Training and Awareness

- Policies and Procedures

- Compliance Governance

- U.S. Grants

- Payments to U.S. Health Care Professionals

- Charitable Contributions

- Education and Research Grants

- Patient Assistance Programs

- Responsible Procurement

- Global Quality Management System (GQMS)

- Public Reporting on Product and Service Safety Issues

- Safety Data Sheets

- Responsible Clinical Trials

- INVESTOR RELATIONS HOME

- Stock Chart

- Historical Price Lookup

- Investment Calculator

- Advanced Fundamentals

- Annual Reports Archive

- SEC Filings

- Corporate Governance Documents

- News Releases

- Events and Presentations

- Financial Tear Sheet

- Shareholder Services

- IR and Communications Contacts

- Working at Bausch Health

- Our U.S. Businesses

Salix to Present Late-Breaking Data from Phase 2 Trial of Amiselimod in Active Ulcerative Colitis at Digestive Disease Week 2024

May 17, 2024

LAVAL, Quebec, May 17, 2024 – Bausch Health Companies Inc. (NYSE/TSX: BHC) and its gastroenterology (GI) business, Salix Pharmaceuticals, today announced that they will be presenting data from its Phase 2 trial evaluating Amiselimod as treatment for active ulcerative colitis (UC). The data will be presented at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2024 during the IMIBD Late Breakers and Innovations in IBD session on Sunday, May 19, 2024, in Washington, D.C.

“We are pleased to present late-breaking data on Amiselimod, our investigational, oral, sphingosine 1- phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator as a potential treatment for the induction of remission in UC,” said Tage Ramakrishna, M.D., Chief Medical Officer and President of Research & Development, Bausch Health. “The abstract underscores our steadfast commitment to developing new and innovative therapies for patients with UC.”

The research to be featured at DDW 2024 and available via the meeting's online platform is as follows:

- Hanauer, Stephen B. et al. “Amiselimod for the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial” Abstract #4094796

The Phase 2 clinical trial was a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, dose ranging study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Amiselimod in 320 patients with mildly-to- moderately active UC. Bausch Health announced positive topline results from this study in December 2023.

About Amiselimod Amiselimod is a sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor functional antagonist and, by inhibiting the receptor function of the lymphocyte sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor, retains lymphocytes sequestered in the lymph nodes and prevents them from contributing to autoimmune reactions.1 Due to this mechanism of action, Amiselimod may potentially be useful for various autoimmune diseases.2 Affinity to S1P1 and S1P5 receptor subtypes, suggests that Amiselimod could potentially have a more pronounced effect on ulcerative colitis related inflammation than compounds with restricted activity on S1P1 receptor subtype exclusively or combined activity on S1P1 and S1P5. 3

About Salix Salix Pharmaceuticals is one of the largest specialty pharmaceutical companies in the world committed to the prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal diseases. For more than 30 years, Salix has licensed, developed, and marketed innovative products to improve patients' lives and provide health care providers with life-changing solutions for many chronic and debilitating conditions. Salix currently markets its product line to U.S. health care providers through an expanded sales force that focuses on gastroenterology, hepatology, pain specialists, and primary care. Salix is headquartered in Bridgewater, New Jersey. For more information about Salix, visit www.Salix.com and connect with us on Twitter and Linkedin

About Bausch Health Bausch Health Companies Inc. (NYSE:BHC)(TSX:BHC) is a global diversified pharmaceutical company enriching lives through our relentless drive to deliver better health outcomes. We develop, manufacture and market a range of products, primarily in gastroenterology, hepatology, neurology, dermatology, medical aesthetic devices, international pharmaceuticals, and eye health, through our controlling interest in Bausch + Lomb. Our ambition is to be a globally integrated healthcare company, trusted and valued by patients, HCPs, employees and investors. For more information, visit www.bauschhealth.com and connect with us on Twitter and LinkedIn .

About DDW Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) is the largest international gathering of physicians, researchers and academics in the fields of gastroenterology, hepatology, endoscopy and gastrointestinal surgery. Jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT), DDW is an in-person and online meeting from May 18-21, 2024. The meeting showcases more than 4,400 abstracts and hundreds of lectures on the latest advances in GI research, medicine and technology. More information can be found at www.ddw.org .

- Kunio Sugahara, Yasuhiro Maeda. Amiselimod, a novel sphingosine 1‐phosphate receptor‐1 modulator, has potent therapeutic efficacy for autoimmune diseases, with low bradycardia risk. British Journal of Pharmacology. January 2017.

- Peyrin-Biroulet, Ronald Christopher Modulation of sphingosine-1-phosphate in inflammatory bowel disease. Autoimmunity Reviews. February 2017.

- BiseraStepanovska, AndreaHuwiler . Targeting the S1P receptor signaling pathways as a promising approach for treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Pharmacological Research. February 2019.

©2024 Salix Pharmaceuticals or its affiliates. UNB.0018.USA.24

STEPHEN M. ADAMS, MD, ELIZABETH D. CLOSE, MD, AND APARNA P. SHREENATH, MD, PhD

Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(4):406-411

Related Letter to the Editor: New-Onset Ulcerative Colitis in Patients With COVID-19

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Ulcerative colitis is a relapsing and remitting inflammatory bowel disease of the large intestine. Risk factors include recent Salmonella or Campylobacter infection and a family history of ulcerative colitis. Diagnosis is suspected based on symptoms of urgency, tenesmus, and hematochezia and is confirmed with endoscopic findings of continuous inflammation from the rectum to more proximal colon, depending on the extent of disease. Fecal calprotectin may be used to assess disease activity and relapse. Medications available to treat the inflammation include 5-aminosalicylic acid, corticosteroids, tumor necrosis factor–alpha antibodies, anti-integrin antibodies, anti-interleukin-12 and -23 antibodies, and Janus kinase inhibitors. Choice of medication and method of delivery depend on the location and severity of mucosal inflammation. Other treatments such as fecal microbiota transplantation are considered experimental, and complementary therapies such as probiotics and curcumin have mixed data. Surgical treatment may be needed for fulminant or refractory disease. Increased risk of colorectal cancer and use of immunosuppressive therapies affect the preventive care needs for these patients.

Ulcerative colitis is a relapsing and remitting inflammatory bowel disease frequently encountered in primary care. This article provides a summary of ulcerative colitis and a review of the available evidence for management.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Ulcerative colitis most commonly presents between 15 and 30 years of age and is more common in industrialized nations, with a prevalence of 286 per 100,000 adults in the United States. 1 , 2

Incidence is similar in men and women. 3

Risk factors include urban living; family history of ulcerative colitis; recent Salmonella , Clostridioides difficile , or Campylobacter infection; tobacco cessation; and soda consumption. 4 , 5

Protective factors include history of appendectomy, active tobacco use, tea consumption, and having been breastfed as an infant. 4 , 5

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Active Salmonella , Shigella , Escherichia coli , Yersinia , Campylobacter , or C. difficile infection should be ruled out using stool studies. 1

Amebic dysentery should be considered if an appropriate travel or exposure history exists. Cytomegalovirus infection should be excluded in immunocompromised patients. 1

Other causes of bloody diarrhea include ischemic colitis, Crohn disease, and colitis caused by medications or radiation. Non-bloody diarrhea can be caused by microscopic colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, celiac disease, or food intolerances. 6

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The most common presenting symptom is bloody diarrhea. Other common symptoms include abdominal pain, tenesmus, and fecal urgency. 1 , 2

Extraintestinal manifestations include arthropathies, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, uveitis, iritis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis. These may be present before the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms. 7 , 8

Overall, extraintestinal manifestations are only 6% more common in patients with inflammatory bowel disease than in the general population and are more common with Crohn disease compared with ulcerative colitis. 8

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Lower endoscopy should be performed on all adult patients with suspected ulcerative colitis. 1 , 9

Fecal calprotectin testing has a high negative predictive value and helps to differentiate inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome, but no serum biomarkers alone are sufficient for the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. 10 A normal fecal calprotectin level (100 mcg per g or less) in children virtually excludes the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis (100% negative predictive value; 95% CI, 98% to 100%). Therefore, in children with a negative fecal calprotectin test, endoscopy can be limited to those whose symptoms persist without another diagnosis. 9 , 11

Bacterial stool culture, including C. difficile toxin assay and stool examination for ova and parasites, should be performed. Other tests, such as complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and measurement of C-reactive protein, may be useful but are nonspecific. 1

Endoscopic evidence of continuous colonic inflammation starting at the rectum with confirmatory biopsies establishes the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. 1

Elevation in serial measurements of fecal calprotectin predicts relapse, whereas serial values in the normal range predict continued remission over time. 12

INDUCTION AND MAINTENANCE OF REMISSION

The goal of managing patients with ulcerative colitis is to attain mucosal healing with symptom control so that sustained steroid-free remission can be achieved and prevent hospitalizations and surgeries.

Initiation of treatment begins with stratifying disease activity into mild vs. moderate to severe. The American College of Gastroenterology Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index provides a set of criteria to help determine if the disease is in remission, mild, moderate to severe, or fulminant. 1

Therapy and medication delivery modes ( Table 1 ) are based on the location and extent of mucosal inflammation. This is broadly divided into proctitis (i.e., 18 cm from the true anal verge), left-sided colitis (i.e., extending to the splenic flexure), and pancolitis (i.e., extending proximal to the splenic flexure). 1

TREATMENT OF MILD DISEASE

The 2019 guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology recommend treatment of mild ulcerative proctitis with rectal 5-amino-salicylic acid (5-ASA) therapies. 1

Mild to moderate colitis should be treated with a combination of rectal 5-ASA enemas and oral 5-ASA therapies. Rectal 5-ASA enemas are preferred to rectal steroid formulations. Mesalamine is more potent than sulfasalazine for inducing remission. 1 , 13

Patients who are unresponsive to or intolerant of 5-ASA should use oral budesonide, extended release (Uceris; multimatrix formulation designed to deliver medication to the colonic mucosa). 1

TREATMENT OF MODERATE TO SEVERE DISEASE

First-line therapy for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis is biologics. 14

Biologic agents with or without glucocorticoids and immune modulators should be used to induce and maintain remission. Thiopurines or methotrexate should not be used as monotherapy. 1

Systemic corticosteroids are effective in inducing remission, but dosages and treatment duration should be limited. Other options for inducing remission include tumor necrosis factor–alpha antibodies, anti-integrin antibodies, anti-interleukin antibodies, and Janus kinase inhibitors 1 ( Table 1 ) .

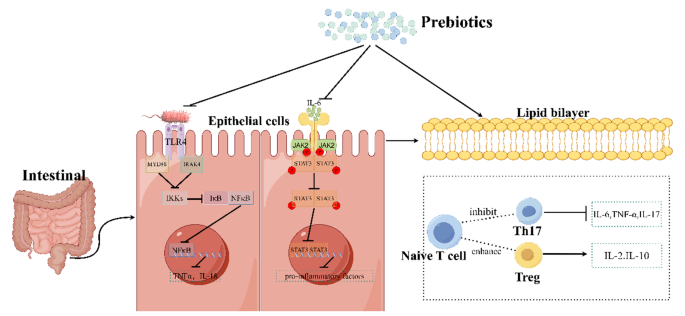

Fecal microbiota transplantation induces remission in some patients with ulcerative colitis, but current use is limited to clinical trials. 15 – 17

SURGICAL TREATMENT

Among patients with ulcerative colitis, 15% will ultimately need colectomy. Indications include failure of medical therapy, toxic megacolon, perforation, uncontrolled hemorrhage, or dysplasia/malignancy. 7

About 50% of patients who undergo colectomy will experience postoperative inflammation of the residual rectal tissue. 18

Predictors for aggressive disease include age younger than 40 years, pancolitis, severe disease activity seen on endoscopy, presence of extraintestinal manifestations, early need for steroids, and elevated inflammatory markers. 1

COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE

One probiotic (VSL#3) modestly improves symptoms. It also helps to prevent pouchitis, an abnormal immune response in patients susceptible to autoimmune disease that leads to inflammation of the rectal pouch fashioned after a colectomy. 19 – 21

A systematic review of six small studies found that curcumin (2 to 3 g daily) promotes clinical and endoscopic improvement when added to conventional therapy in patients with mild ulcerative colitis. 22

Fish oil does not improve remission rates. 23 , 24

Acupuncture is considered safe in addition to conventional treatment, but high-quality evidence of effectiveness is lacking. 25

LIFESTYLE AND BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS

Exercise and diet interventions help improve symptom burden and quality of life.

A low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) diet reduces symptoms but does not change clinical severity. 26 , 27

Physical activity improves quality of life and the anxiety that commonly affects patients with inflammatory bowel disease. 28

HOSPITAL CARE

Up to 25% of patients with ulcerative colitis will require hospitalization for severe disease.

Early endoscopy should be performed to exclude cytomegalovirus colitis, and C. difficile testing should be ordered.

Avoidance of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opiates, and anticholinergic medications is recommended. Antibiotics should not be used routinely.

Surgical consultation should be obtained for patients not responding to intravenous corticosteroids after three days, or earlier if other surgical indications (e.g., toxic megacolon) arise.

If there is failure of intravenous corticosteroids after three days of treatment, cyclosporine (Sandimmune) or infliximab (Remicade) may be used as rescue therapy. 29

Preventive Care Considerations

Vaccinations should be given according to routine recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, paying special attention to additional vaccinations necessary for patients on immunosuppressive therapies. 30

Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry is recommended to check for low bone mineral density in patients with ulcerative colitis, especially those with a history of chronic oral corticosteroid use for three months or more. 31

Skin cancer occurs at higher rates in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. In addition, common therapies for ulcerative colitis increase the risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer. 32

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends annual cytology screening for cervical cancer in women on immunosuppressive therapy. 33

Colonoscopy is recommended starting eight years after diagnosis of ulcerative colitis or immediately if primary sclerosing cholangitis is also present because of an increased risk of colorectal cancer. Interval surveillance in those with disease proximal to the sigmoid colon should occur every one to three years based on risk factors and prior endoscopy findings, with annual colonoscopies in patients with concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis, due to very high risk of developing colorectal cancer. 1 , 34

Most patients with ulcerative colitis experience a mild to moderate course with periods of remission and flare-ups.

Ulcerative colitis does not increase mortality but is associated with high morbidity. 7

ULCERATIVE COLITIS AND COVID-19

Based on a panel of international experts, in the absence of definitive data, the American Gastroenterological Association has concluded that the risk of a patient with ulcerative colitis becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 is no higher than that of the general population, independent of treatment.

It is unknown whether active inflammation from ulcerative colitis can increase the risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2.

The American Gastroenterological Association recommends ongoing biologic therapy, deeming it safe for patients who are on such medications to continue working in environments with those who have known or suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Patients who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 and whose ulcerative colitis medications are held because of this can restart their medications after 14 days if they do not develop symptoms or if symptoms resolve. 35

A retrospective review of patients vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 suggests the vaccine effectiveness and adverse event rate in patients with inflammatory bowel disease is similar to the general population. 36

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Adams and Bornemann . 37

Data Sources: This article was based on ACG and AGA Guidelines, the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, and a PubMed search including meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and systematic reviews. Search dates: December 2020 through October 2021.

- Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):384-413.

- Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies [published correction appears in Lancet . 2020; 396(10256): e56]. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769-2778.

Ngo ST, Steyn FJ, McCombe PA. Gender differences in autoimmune disease. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35(3):347-369.

- Esan OB, Perera R, McCarthy N, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and health service burden of sequelae of Campylobacter and non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in England, 2000–2015: a retrospective cohort study using linked electronic health records. J Infect. 2020;81(2):221-230.

- Piovani D, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(3):647-659.e4.

- Arasaradnam RP, Brown S, Forbes A, et al. Guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea in adults: British Society of Gastroenterology, 3rd ed. Gut. 2018;67(8):1380-1399.

- Fumery M, Singh S, Dulai PS, et al. Natural history of adult ulcerative colitis in population-based cohorts: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):343-356.e3.

Card TR, Langan SM, Chu TPC. Extra-gastrointestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease may be less common than previously reported. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(9):2619-2626.

- Holtman GA, Lisman-van Leeuwen Y, Kollen BJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in primary care: a prospective cohort study. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(5):437-445. Accessed October 14, 2021. https://www.annfammed.org/content/14/5/437.long

- Menees SB, Powell C, Kurlander J, et al. A meta-analysis of the utility of C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, fecal calprotectin, and fecal lactoferrin to exclude inflammatory bowel disease in adults with IBS. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(3):444-454.

- Walker GJ, Chanchlani N, Thomas A, et al. Primary care faecal calprotectin testing in children with suspected inflammatory bowel disease: a diagnostic accuracy study. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105(10):957-963.

Heida A, Park KT, van Rheenen PF. Clinical utility of fecal calprotectin monitoring in asymptomatic patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and practical guide. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(6):894-902.

- Ko CW, Singh S, Feuerstein JD, et al.; American Gastroenterological Association Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(3):748-764.

- Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, et al.; AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1450-1461.

- Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1218-1228.

- Costello SP, Hughes PA, Waters O, et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on 8-week remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(2):156-164.

- Imdad A, Nicholson MR, Tanner-Smith EE, et al. Fecal transplantation for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;(11):CD012774.

- Nguyen N, Zhang B, Holubar SD, et al. Treatment and prevention of pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(11):CD001176.

- Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Papa A, et al. Treatment of relapsing mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis with the probiotic VSL#3 as adjunctive to a standard pharmaceutical treatment: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(10):2218-2227.

Limketkai BN, Wolf A, Parian AM. Nutritional interventions in the patient with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2018;47(1):155-177.

Lin SC, Cheifetz AS. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2018;14(7):415-425.

- Coelho MR, Romi MD, Ferreira DMTP, et al. The use of curcumin as a complementary therapy in ulcerative colitis: a systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2296.

- Scaioli E, Sartini A, Bellanova M, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid reduces fecal levels of calprotectin and prevents relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(8):1268-1275.e2.

Turner D, Steinhart AH, Griffiths AM. Omega 3 fatty acids (fish oil) for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD006443.

- Wang X, Zhao NQ, Sun YX, et al. Acupuncture for ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20(1):309.

- Cox SR, Lindsay JO, Fromentin S, et al. Effects of low FOD-MAP diet on symptoms, fecal microbiome, and markers of inflammation in patients with quiescent inflammatory bowel disease in a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(1):176-188.e7.

- Prince AC, Myers CE, Joyce T, et al. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction (low FODMAP diet) in clinical practice improves functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(5):1129-1136.

- Eckert KG, Abbasi-Neureither I, Köppel M, et al. Structured physical activity interventions as a complementary therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease - a scoping review and practical implications. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19(1):115.

Fudman DI, Sattler L, Feuerstein JD. Inpatient management of acute severe ulcerative colitis. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(12):766-773.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended adult immunization schedule by medical condition and other indications, United States, 2021. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Last reviewed February 12, 2021. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/adult-conditions.html#table-conditions

- Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al.; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis [published correction appears in Osteoporos Int . 2015;26(7):2045–2047]. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2381.

- Farraye FA, Melmed GY, Lichtenstein GR, et al. ACG clinical guideline: preventive care in inflammatory bowel disease [published correction appears in Am J Gastroenterol . 2017;112(7):1208]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(2):241-258.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e111-e130.

- Lopez A, Pouillon L, Beaugerie L, et al. Colorectal cancer prevention in patients with ulcerative colitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;32–33:103-109.

- Rubin DT, Feuerstein JD, Wang AY, et al. AGA clinical practice update on management of inflammatory bowel disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: expert commentary. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(1):350-357.

- Hadi YB, Thakkar S, Shah-Khan SM, et al. COVID-19 vaccination is safe and effective in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: analysis of a large multi-institutional research network in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(4):1336-1339.e3.

Adams SM, Bornemann PH. Ulcerative colitis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87(10):699-705. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2013/0515/p699.html

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2022 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

A comprehensive review and update on ulcerative colitis

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Science Center El Paso, 2000B Transmountain Road, El Paso, TX 79911, USA; Paul L. Foster School of Medicine (PLFSOM), Texas Tech University Health Science Center El Paso, 5001 El Paso Dr, El Paso, TX 79905, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Internal Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, 4800 Alberta Avenue, El Paso, TX 79905, USA.

- 3 Paul L. Foster School of Medicine (PLFSOM), Texas Tech University Health Science Center El Paso, 5001 El Paso Dr, El Paso, TX 79905, USA.

- 4 Department of Family Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Science Center El Paso, 2000B Transmountain Road, El Paso, TX 79911, USA.

- 5 Department of Surgery, Texas Tech University Health Science Center El Paso, 2000B Transmountain Road, El Paso, TX 79911, USA.

- 6 Department of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, University of California San Francisco (UCSF), Fresno, CA, USA.

- 7 Division of Gastroenterology, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon.

- 8 Division of Gastroenterology, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon; Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, University of Pittsburgh, M2, C Wing, 200 Lothrop Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA.

- PMID: 30837080

- DOI: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2019.02.004