13 social media research topics to explore in 2024

Last updated

15 January 2024

Reviewed by

Miroslav Damyanov

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

To help you choose a specific area to examine, here are some of the top social media research topics that are relevant in 2024.

- What makes a strong social media research topic?

Consider the factors below to ensure your topic is strong and compelling:

Clarity: regardless of the topic you investigate, clarity is essential. It ensures readers will be able to understand your work and any wider learnings. Your argument should be clear and your language unambiguous.

Trend relevancy: you need to know what’s currently happening in social media to draw relevant conclusions. Before choosing a topic, consider current popular platforms, trending content, and current use cases to ensure you understand social media as it is today.

New insights: if your research is to be new, innovative, and helpful for the wider population, it should cover areas that haven’t been studied before. Look into what’s already been thoroughly researched to help you uncover knowledge gaps that could be good focus areas.

- Tips for choosing social media research topics

When considering social media research questions, it’s also important to consider whether you’re the right person to conduct that area of study. Your skills, interests, and time allocated will all impact your suitability.

Consider your skillset: your specific expertise is highly valuable when conducting research. Choosing a topic that aligns with your skills will help ensure you can add a thorough analysis and your own learnings.

Align with your interests: if you’re deeply interested in a topic, you’re much more likely to enjoy the process and dedicate the time it needs for a thorough analysis.

Consider your resources: the time you have available to complete the research, your allocated funds, and access to resources should all impact the research topic you choose.

- 13 social media research paper topics

To help you choose the right area of research, we’ve rounded up some of the most compelling topics within the sector. These ideas may also help you come up with your own.

1. The influence of social media on mental health

It’s well-documented that social media can impact mental health. For example, a significant amount of research has highlighted the link between social media and conditions like anxiety, depression, and stress—but there’s still more to uncover in this area.

There are high rates of mental illness worldwide, so there’s continual interest in ways to understand and mitigate it. Studies could focus on the following areas:

The reasons why social media can impact mental health

How social media can impact specific mental health conditions (you might also look at different age groups here)

How to reduce social media’s impact on mental health

2. The effects of social media exposure on child development

There are many unknowns with social media. More research is needed to understand how it impacts children. As such, this is a very valuable research area.

You might explore the following topics:

How social media impacts children at different ages

The long-term effects of childhood social media use

The benefits of social media use in children

How social media use impacts childhood socialization, communication, and learning

3. The role of social media in political campaigning

Social media’s role in political campaigning is nothing new. The Cambridge Analytica Scandal, for example, involved data from millions of Facebook profiles being sold to a third party for political advertising. Many believe this could have impacted the 2016 US election results. Ultimately, Facebook had to pay a private class-action lawsuit of $725 million.

The role of social media in political campaigns is of global significance. Concerns are still high that social media can play a negative role in elections due to the spread of misinformation, disinformation, and the bandwagon effect.

Research in this area could look into the following topics:

How people are influenced by social media when it comes to voting

Ways to mitigate misinformation

Election interference and how this can be prevented

4. The role of social media in misinformation and disinformation

Misinformation and disinformation mean slightly different things. Misinformation is unintentionally sharing false or inaccurate information, while disinformation is sharing false information with the deliberate intent to mislead people.

Both can play a role not just in elections but throughout social media. This became particularly problematic during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research into this area is important given the widespread risk that comes with spreading false information about health and safety-related topics.

Here are some potential research areas:

How misinformation and disinformation are spread via social media

The impact of false information (you could focus on how it impacts health, for example)

Strategies for mitigating the impact of false information and encouraging critical thinking

The avenues through which to hold technology companies accountable for spreading misinformation

5. The impact of AI and deepfakes on social media

AI technology is expected to continue expanding in 2024. Some are concerned that this could impact social media. One concern is the potential for the widespread use of deepfake technology—a form of AI that uses deep learning to create fake images.

Fake images can be used to discredit, shame, and control others, so researchers need to deeply understand this area of technology. You might look into the following areas:

The potential impacts of deepfakes on businesses and their reputations

Deepfake identities on social media: privacy concerns and other risks

How deepfake images can be identified, controlled, and prevented

6. How social media can benefit communities

While there’s much research into the potential negative impacts of social media, it can also provide many benefits.

Social media can establish connections for those who might otherwise be isolated in the community. It can facilitate in-person gatherings and connect people who are physically separated, such as relatives who live in different countries. Social media can also provide critical information to communities quickly in the case of emergencies.

Research into the ways social media can provide these key benefits can make interesting topics. You could consider the following:

Which social media platforms offer the most benefits

How to better use social media to lean into these benefits

How new social platforms could connect us in more helpful ways

7. The psychology of social media

Social media psychology explores human behavior in relation to social media. There are a range of topics within social media psychology, including the following:

The influence of social media on social comparison

Addiction and psychological dependence on social media

How social media increases the risk of cyberbullying

How social media use impacts people’s attention spans

Social interactions and the impact on socialization

Persuasion and influence on social media

8. How communication has evolved through social media

Social media has provided endless ways for humans to connect and interact, so the ways we do this have evolved.

Most obviously, social media has provided ways to connect instantaneously via real-time messaging and communicate using multimedia formats, including text, images, emojis, video content, and audio.

This has made communication more accessible and seamless, especially given many people now own smartphones that can connect to social media apps from anywhere.

You might consider researching the following topics:

How social media has changed the way people communicate

The impacts of being continuously connected, both positive and negative

How communication may evolve in the future due to social media

9. Social media platforms as primary news sources

As social media use has become more widespread, many are accessing news information primarily from their newsfeeds. This can be particularly problematic, given that newsfeeds are personalized providing content to people based on their data.

This can cause people to live in echo chambers, where they are constantly targeted with content that aligns with their beliefs. This can cause people to become more entrenched in their way of thinking and more unable or unwilling to see other people’s opinions and points of view.

Research in this area could consider the following:

The challenges that arise from using social media platforms as a primary news source

The pros and cons of social media: does it encourage “soloization” or diverse perspectives?

How to prevent social media echo chambers from occurring

The impact of social media echo chambers on journalistic integrity

10. How social media is impacting modern journalism

News platforms typically rely on an advertising model where more clicks and views increase revenue. Since sensationalist stories can attract more clicks and shares on social media, modern journalism is evolving.

Journalists are often rewarded for writing clickbait headlines and content that’s more emotionally triggering (and therefore shareable).

Your research could cover the following areas:

How journalism is evolving due to social media

How to mitigate social media’s impact on neutral reporting

The importance of journalistic standards in the age of social media

11. The impact of social media on traditional advertising

Digital advertising is growing in popularity. Worldwide, ad spending on social media was expected to reach $207.1 billion in 2023 . Experts estimate that ad spending on mobile alone will reach $255.8 billion by 2028 . This move continues to impact traditional advertising, which takes place via channels like print, TV, and radio.

Most organizations consider their social strategy a critical aspect of their advertising program. Many exclusively advertise on social media—especially those with limited budgets.

Here are some interesting research topics in this area

The impact of different advertising methods

Which social media advertising channels provide the highest return on investment (ROI)

The societal impacts of social media advertising

12. Impacts of social media presence on corporate image

Social media presence can provide companies with an opportunity to be visible and increase brand awareness . Social media also provides a key way to interact with customers.

More and more customers now expect businesses to be online. Research shows that 63% of customers expect companies to offer customer service via their social media channels, while a whopping 90% have connected with a brand or business through social media.

Research in this area could focus on the following topics:

The advantages and disadvantages of social media marketing for businesses

How social media can impact a business’s corporate image

How social media can boost customer experience and loyalty

13. How social media impacts data privacy

Using social media platforms is free for the most part, but users have to provide their personal data for the privilege. This means data collection , tracking, the potential for third parties to access that data, psychological profiling, geolocation, and tracking are all potential risks for users.

Data security and privacy are of increasing interest globally. Research within this area will likely be in high demand in 2024.

Here are some of the research topics you might want to consider in this area:

Common privacy concerns with social media use

Why is social media privacy important?

What can individuals do to protect their data when using social media?

- The importance of social media research

As social media use continues to expand in the US and around the world, there’s continual interest in research on the topic. The research you conduct could positively impact many groups of people.

Topics can cover a broad range of areas. You might look at how social media can harm or benefit people, how social media can impact journalism, how platforms can impact young people, or the data privacy risks involved with social media use. The options are endless, and new research topics will present themselves as technology evolves.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 9 November 2024

Last updated: 30 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 12 October 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 31 January 2024

Last updated: 23 January 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, a whole new way to understand your customer is here, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Privacy Policy

Home » Social Media Research Topics

Social Media Research Topics

Table of Contents

Social media has transformed how we communicate, work, and interact with the world, making it a fertile ground for research. As a constantly evolving platform, social media touches various fields like psychology, business, politics, and technology. Research in this area helps us understand its effects on individuals, societies, and economies. This post explores key research topics in social media, providing ideas and insights for students, academics, and professionals interested in studying its dynamics.

Social media research helps us uncover insights into digital behavior, identify trends, and understand the societal impacts of these platforms. With over 4 billion users globally, social media has profound effects on identity, privacy, public opinion, and even mental health. Research in this area can guide best practices, inform policies, and shed light on how social media reshapes our daily lives.

Key Areas for Social Media Research

- Impact of Social Media on Self-Esteem and Body Image : Examines how curated images and content affect users’ self-perception and self-worth.

- Addiction and Dependency : Studies social media addiction, its behavioral patterns, and its impact on overall mental health.

- Cyberbullying and Online Harassment : Explores the psychological impact of bullying and harassment online, especially among young users.

- Effectiveness of Influencer Marketing : Analyzes how influencers shape consumer attitudes and purchasing behavior.

- Trust and Authenticity in Influencer-Consumer Relationships : Investigates how perceived authenticity influences consumer trust and loyalty.

- Role of Micro-Influencers in Marketing : Looks into the power of smaller influencers compared to celebrity endorsements in driving engagement.

- User Awareness of Privacy Risks : Studies the awareness and attitudes of users towards privacy risks on social media.

- Data Collection and Personalization : Examines how data is collected, how it’s used for targeted advertising, and the ethics surrounding it.

- Impact of Privacy Policy Changes on User Behavior : Investigates how updates in privacy policies (such as Facebook’s and WhatsApp’s) affect user engagement and trust.

- Social Media as a Tool for Political Campaigns : Analyzes how politicians and campaigns use social media to shape public opinion and influence elections.

- Spread of Misinformation and Fake News : Explores the role of social media in spreading misinformation and its effect on public trust.

- Echo Chambers and Polarization : Studies how algorithms can create echo chambers, leading to increased polarization on topics like politics and health.

- Role of Social Media in Public Health Crises : Investigates how social media has been used to communicate information during health crises like the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Government and Organization Use of Social Media in Emergencies : Analyzes how governments and organizations use platforms to share emergency updates.

- Public Response to Crisis Information : Studies how the public engages with and responds to crisis information shared online.

- Influence of Social Media on Teen Identity : Looks into how social media affects identity formation and self-image among adolescents.

- Presentation of Self on Social Media : Studies how users curate and present different aspects of their identities on social platforms.

- Gender and Social Media : Explores how gender representation and stereotypes are reinforced or challenged on social media platforms.

- Social Media as a Learning Tool : Investigates the effectiveness of platforms like YouTube and LinkedIn in providing educational content.

- Digital Literacy and Responsible Usage : Studies how digital literacy training can help students use social media responsibly.

- Impact of Social Media on Student Performance : Examines how the use of social media affects students’ academic performance and time management.

- Role of AI in Content Moderation : Looks into how AI is being used to moderate content, identify hate speech, and prevent the spread of misinformation.

- Rise of Augmented Reality (AR) in Social Media : Examines how AR features like filters and virtual try-ons are transforming user experiences on platforms like Instagram and Snapchat.

- Social Commerce and E-commerce Integration : Studies the role of social media as a direct sales platform and its effect on e-commerce.

- Responsibility of Platforms in Preventing Harm : Analyzes the role social media companies play in protecting users from harmful content.

- Ethical Implications of Social Media Algorithms : Studies how recommendation algorithms may affect user behavior and content consumption.

- Social Media’s Role in Shaping Cultural Values : Explores how platforms influence cultural norms, values, and social behavior.

- Social Media’s Impact on Relationships

- Effects on Romantic Relationships : Studies the impact of social media on romantic relationships, including jealousy, trust issues, and communication.

- Family Dynamics in the Age of Social Media : Investigates how social media affects family relationships and parent-child interactions.

- Friendship and Social Networks : Looks into how online friendships compare to offline ones and the role of social media in maintaining long-distance relationships.

How to Choose a Research Topic in Social Media

- Identify Your Interests Start by identifying which aspect of social media interests you most—whether it’s mental health, marketing, privacy, or any other area.

- Review Recent Studies Use resources like Google Scholar to review recent research in your area of interest. This will give you an idea of the latest findings and areas that need further exploration.

- Narrow Your Focus Social media is a broad field, so try to narrow your focus. Instead of researching “Social Media and Mental Health,” specify it to something like “The Impact of Instagram on Teenage Body Image.”

- Formulate a Research Question Once you have a specific area, formulate a research question that will guide your study. A clear research question will help you structure your investigation and provide a clear goal.

- Consider Ethical Implications Social media research often involves sensitive topics, so consider the ethical implications. Ensure your research respects privacy and adheres to ethical guidelines.

Example Research Questions

- How does the use of Instagram filters affect self-esteem among adolescents?

- What role does social media play in spreading misinformation during public health crises?

- How do social media algorithms impact political polarization and public opinion?

- What factors influence consumer trust in influencer recommendations?

- How do different age groups respond to privacy policies on social media platforms?

Social media research covers a broad range of topics with far-reaching implications. By studying the effects, trends, and ethical considerations surrounding social media, researchers can contribute valuable insights into this digital phenomenon that impacts every aspect of modern life. Whether you’re a student, an academic, or a professional, exploring these topics can provide a deeper understanding of how social media shapes individuals and society.

- Chen, G. M., & Zhang, Y. (2019). Social Media Research: Theories, Constructs, and Applications . Journal of Communication, 69(3), 370–389.

- Boyd, D., & Ellison, N. B. (2017). Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship . Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210–230.

- Aral, S., Eckles, D., & Levandoski, J. (2020). The Impact of Social Media on Well-being and Social Comparison . Annual Review of Psychology, 71, 639-665.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Qualitative Research Titles and Topics

Astronomy Research Topics

Educational Research Topics

Argumentative Research Paper Topics

Political Science Research Topics

Psychology Research Paper Topics

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Social Media Use in 2021

A majority of Americans say they use YouTube and Facebook, while use of Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok is especially common among adults under 30.

Table of contents.

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

To better understand Americans’ use of social media, online platforms and messaging apps, Pew Research Center surveyed 1,502 U.S. adults from Jan. 25 to Feb. 8, 2021, by cellphone and landline phone. The survey was conducted by interviewers under the direction of Abt Associates and is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, education and other categories. Here are the questions used for this report , along with responses, and its methodology .

Despite a string of controversies and the public’s relatively negative sentiments about aspects of social media, roughly seven-in-ten Americans say they ever use any kind of social media site – a share that has remained relatively stable over the past five years, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults.

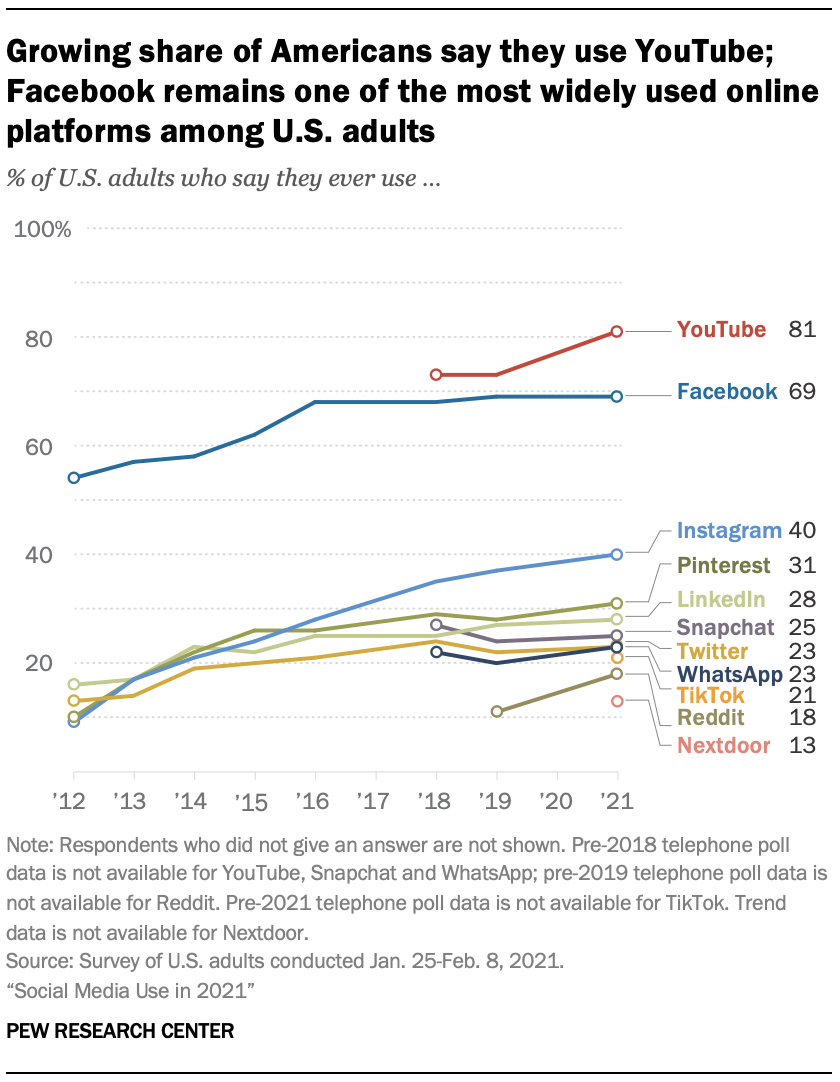

Beyond the general question of overall social media use, the survey also covers use of individual sites and apps. YouTube and Facebook continue to dominate the online landscape, with 81% and 69%, respectively, reporting ever using these sites. And YouTube and Reddit were the only two platforms measured that saw statistically significant growth since 2019 , when the Center last polled on this topic via a phone survey.

When it comes to the other platforms in the survey, 40% of adults say they ever use Instagram and about three-in-ten report using Pinterest or LinkedIn. One-quarter say they use Snapchat, and similar shares report being users of Twitter or WhatsApp. TikTok – an app for sharing short videos – is used by 21% of Americans, while 13% say they use the neighborhood-focused platform Nextdoor.

Even as other platforms do not nearly match the overall reach of YouTube or Facebook, there are certain sites or apps, most notably Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok, that have an especially strong following among young adults. In fact, a majority of 18- to 29-year-olds say they use Instagram (71%) or Snapchat (65%), while roughly half say the same for TikTok.

These findings come from a nationally representative survey of 1,502 U.S. adults conducted via telephone Jan. 25-Feb.8, 2021.

With the exception of YouTube and Reddit, most platforms show little growth since 2019

YouTube is the most commonly used online platform asked about in this survey, and there’s evidence that its reach is growing. Fully 81% of Americans say they ever use the video-sharing site, up from 73% in 2019. Reddit was the only other platform polled about that experienced statistically significant growth during this time period – increasing from 11% in 2019 to 18% today.

Facebook’s growth has leveled off over the last five years, but it remains one of the most widely used social media sites among adults in the United States: 69% of adults today say they ever use the site, equaling the share who said this two years prior.

Similarly, the respective shares of Americans who report using Instagram, Pinterest, LinkedIn, Snapchat, Twitter and WhatsApp are statistically unchanged since 2019 . This represents a broader trend that extends beyond the past two years in which the rapid adoption of most of these sites and apps seen in the last decade has slowed. (This was the first year the Center asked about TikTok via a phone poll and the first time it has surveyed about Nextdoor.)

Adults under 30 stand out for their use of Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok

When asked about their social media use more broadly – rather than their use of specific platforms – 72% of Americans say they ever use social media sites.

In a pattern consistent with past Center studies on social media use, there are some stark age differences. Some 84% of adults ages 18 to 29 say they ever use any social media sites, which is similar to the share of those ages 30 to 49 who say this (81%). By comparison, a somewhat smaller share of those ages 50 to 64 (73%) say they use social media sites, while fewer than half of those 65 and older (45%) report doing this.

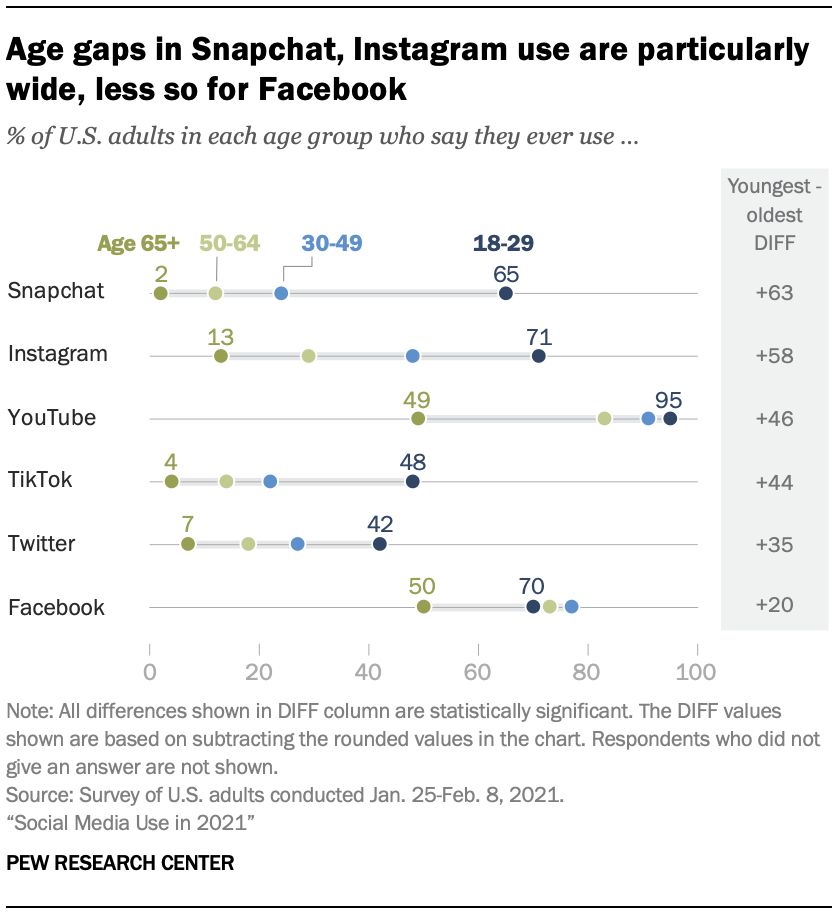

These age differences generally extend to use of specific platforms, with younger Americans being more likely than their older counterparts to use these sites – though the gaps between younger and older Americans vary across platforms.

Majorities of 18- to 29-year-olds say they use Instagram or Snapchat and about half say they use TikTok, with those on the younger end of this cohort – ages 18 to 24 – being especially likely to report using Instagram (76%), Snapchat (75%) or TikTok (55%). 1 These shares stand in stark contrast to those in older age groups. For instance, while 65% of adults ages 18 to 29 say they use Snapchat, just 2% of those 65 and older report using the app – a difference of 63 percentage points.

Additionally, a vast majority of adults under the age of 65 say they use YouTube. Fully 95% of those 18 to 29 say they use the platform, along with 91% of those 30 to 49 and 83% of adults 50 to 64. However, this share drops substantially – to 49% – among those 65 and older.

By comparison, age gaps between the youngest and oldest Americans are narrower for Facebook. Fully 70% of those ages 18 to 29 say they use the platform, and those shares are statistically the same for those ages 30 to 49 (77%) or ages 50 to 64 (73%). Half of those 65 and older say they use the site – making Facebook and YouTube the two most used platforms among this older population.

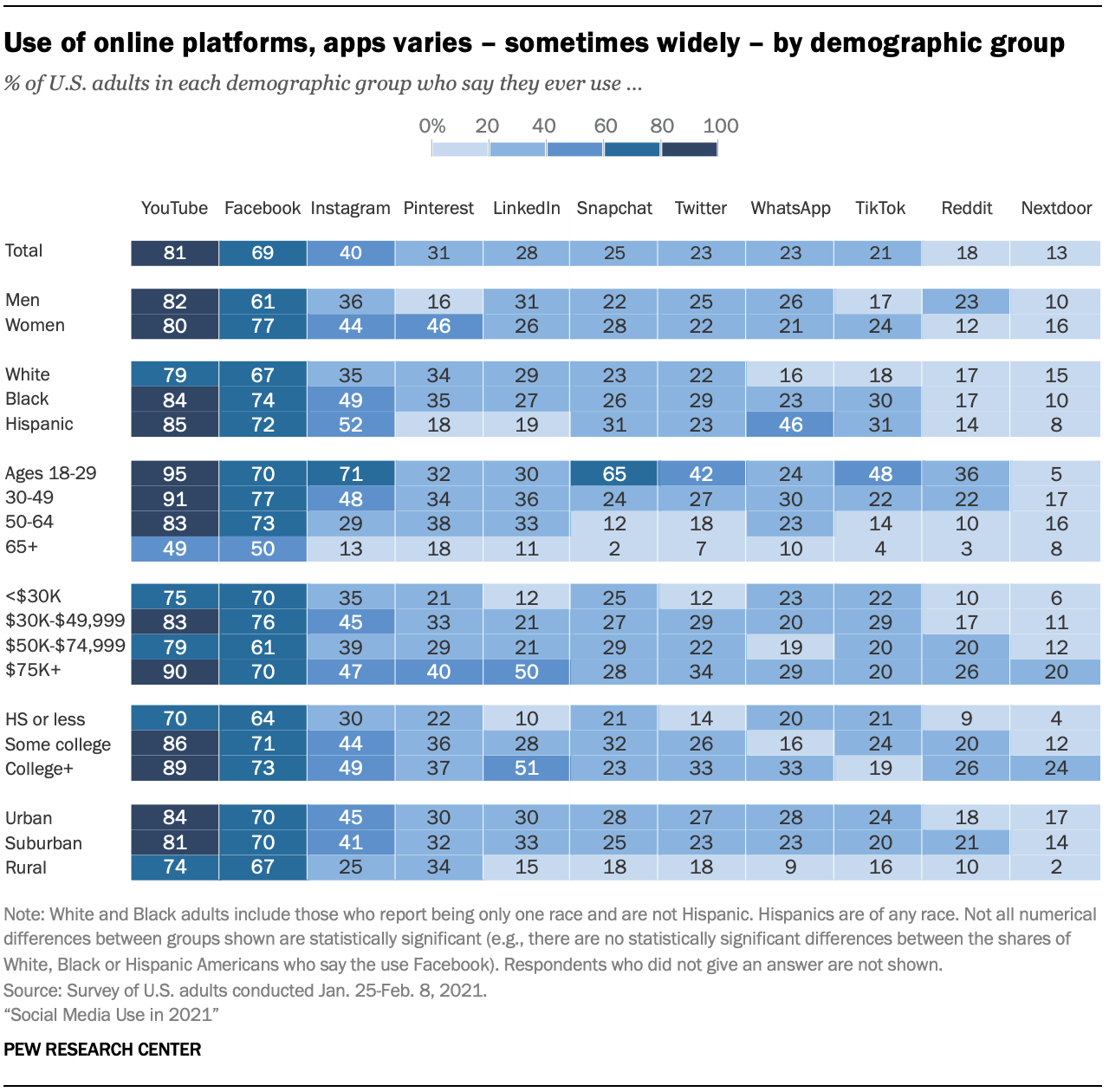

Other sites and apps stand out for their demographic differences:

- Instagram: About half of Hispanic (52%) and Black Americans (49%) say they use the platform, compared with smaller shares of White Americans (35%) who say the same. 2

- WhatsApp: Hispanic Americans (46%) are far more likely to say they use WhatsApp than Black (23%) or White Americans (16%). Hispanics also stood out for their WhatsApp use in the Center’s previous surveys on this topic.

- LinkedIn: Those with higher levels of education are again more likely than those with lower levels of educational attainment to report being LinkedIn users. Roughly half of adults who have a bachelor’s or advanced degree (51%) say they use LinkedIn, compared with smaller shares of those with some college experience (28%) and those with a high school diploma or less (10%).

- Pinterest: Women continue to be far more likely than men to say they use Pinterest when compared with male counterparts, by a difference of 30 points (46% vs. 16%).

- Nextdoor: There are large differences in use of this platform by community type. Adults living in urban (17%) or suburban (14%) areas are more likely to say they use Nextdoor. Just 2% of rural Americans report using the site.

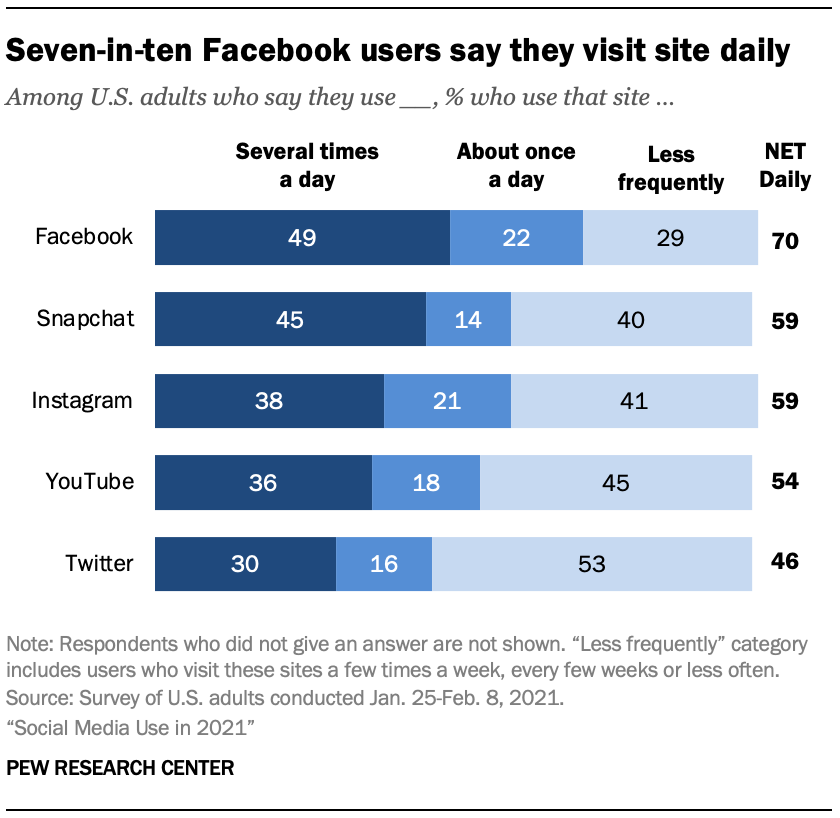

A majority of Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram users say they visit these platforms on a daily basis

While there has been much written about Americans’ changing relationship with Facebook , its users remain quite active on the platform. Seven-in-ten Facebook users say they use the site daily, including 49% who say they use the site several times a day. (These figures are statistically unchanged from those reported in the Center’s 2019 survey about social media use.)

Smaller shares – though still a majority – of Snapchat or Instagram users report visiting these respective platforms daily (59% for both). And being active on these sites is especially common for younger users. For instance, 71% of Snapchat users ages 18 to 29 say they use the app daily, including six-in-ten who say they do this multiple times a day. The pattern is similar for Instagram: 73% of 18- to 29-year-old Instagram users say they visit the site every day, with roughly half (53%) reporting they do so several times per day.

YouTube is used daily by 54% if its users, with 36% saying they visit the site several times a day. By comparison, Twitter is used less frequently, with fewer than half of its users (46%) saying they visit the site daily.

- Due to a limited sample size, figures for those ages 25 to 29 cannot be reported on separately. ↩

- There were not enough Asian American respondents in the sample to be broken out into a separate analysis. As always, their responses are incorporated into the general population figures throughout this report. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Social Media

- User Demographics

America’s News Influencers

- Social Media Fact Sheet

More Americans – especially young adults – are regularly getting news on TikTok

Many israelis say social media content about the israel-hamas war should be censored, whatsapp and facebook dominate the social media landscape in middle-income nations, most popular, report materials.

- 2021 Core Trends Survey

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Research trends in social media addiction and problematic social media use: a bibliometric analysis.

- 1 Sasin School of Management, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

- 2 Business Administration Division, Mahidol University International College, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand

Despite their increasing ubiquity in people's lives and incredible advantages in instantly interacting with others, social media's impact on subjective well-being is a source of concern worldwide and calls for up-to-date investigations of the role social media plays in mental health. Much research has discovered how habitual social media use may lead to addiction and negatively affect adolescents' school performance, social behavior, and interpersonal relationships. The present study was conducted to review the extant literature in the domain of social media and analyze global research productivity during 2013–2022. Bibliometric analysis was conducted on 501 articles that were extracted from the Scopus database using the keywords social media addiction and problematic social media use. The data were then uploaded to VOSviewer software to analyze citations, co-citations, and keyword co-occurrences. Volume, growth trajectory, geographic distribution of the literature, influential authors, intellectual structure of the literature, and the most prolific publishing sources were analyzed. The bibliometric analysis presented in this paper shows that the US, the UK, and Turkey accounted for 47% of the publications in this field. Most of the studies used quantitative methods in analyzing data and therefore aimed at testing relationships between variables. In addition, the findings in this study show that most analysis were cross-sectional. Studies were performed on undergraduate students between the ages of 19–25 on the use of two social media platforms: Facebook and Instagram. Limitations as well as research directions for future studies are also discussed.

Introduction

Social media generally refers to third-party internet-based platforms that mainly focus on social interactions, community-based inputs, and content sharing among its community of users and only feature content created by their users and not that licensed from third parties ( 1 ). Social networking sites such as Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok are prominent examples of social media that allow people to stay connected in an online world regardless of geographical distance or other obstacles ( 2 , 3 ). Recent evidence suggests that social networking sites have become increasingly popular among adolescents following the strict policies implemented by many countries to counter the COVID-19 pandemic, including social distancing, “lockdowns,” and quarantine measures ( 4 ). In this new context, social media have become an essential part of everyday life, especially for children and adolescents ( 5 ). For them such media are a means of socialization that connect people together. Interestingly, social media are not only used for social communication and entertainment purposes but also for sharing opinions, learning new things, building business networks, and initiate collaborative projects ( 6 ).

Among the 7.91 billion people in the world as of 2022, 4.62 billion active social media users, and the average time individuals spent using the internet was 6 h 58 min per day with an average use of social media platforms of 2 h and 27 min ( 7 ). Despite their increasing ubiquity in people's lives and the incredible advantages they offer to instantly interact with people, an increasing number of studies have linked social media use to negative mental health consequences, such as suicidality, loneliness, and anxiety ( 8 ). Numerous sources have expressed widespread concern about the effects of social media on mental health. A 2011 report by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) identifies a phenomenon known as Facebook depression which may be triggered “when preteens and teens spend a great deal of time on social media sites, such as Facebook, and then begin to exhibit classic symptoms of depression” ( 9 ). Similarly, the UK's Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) claims that there is a clear evidence of the relationship between social media use and mental health issues based on a survey of nearly 1,500 people between the ages of 14–24 ( 10 ). According to some authors, the increase in usage frequency of social media significantly increases the risks of clinical disorders described (and diagnosed) as “Facebook depression,” “fear of missing out” (FOMO), and “social comparison orientation” (SCO) ( 11 ). Other risks include sexting ( 12 ), social media stalking ( 13 ), cyber-bullying ( 14 ), privacy breaches ( 15 ), and improper use of technology. Therefore, social media's impact on subjective well-being is a source of concern worldwide and calls for up-to-date investigations of the role social media plays with regard to mental health ( 8 ). Many studies have found that habitual social media use may lead to addiction and thus negatively affect adolescents' school performance, social behavior, and interpersonal relationships ( 16 – 18 ). As a result of addiction, the user becomes highly engaged with online activities motivated by an uncontrollable desire to browse through social media pages and “devoting so much time and effort to it that it impairs other important life areas” ( 19 ).

Given these considerations, the present study was conducted to review the extant literature in the domain of social media and analyze global research productivity during 2013–2022. The study presents a bibliometric overview of the leading trends with particular regard to “social media addiction” and “problematic social media use.” This is valuable as it allows for a comprehensive overview of the current state of this field of research, as well as identifies any patterns or trends that may be present. Additionally, it provides information on the geographical distribution and prolific authors in this area, which may help to inform future research endeavors.

In terms of bibliometric analysis of social media addiction research, few studies have attempted to review the existing literature in the domain extensively. Most previous bibliometric studies on social media addiction and problematic use have focused mainly on one type of screen time activity such as digital gaming or texting ( 20 ) and have been conducted with a focus on a single platform such as Facebook, Instagram, or Snapchat ( 21 , 22 ). The present study adopts a more comprehensive approach by including all social media platforms and all types of screen time activities in its analysis.

Additionally, this review aims to highlight the major themes around which the research has evolved to date and draws some guidance for future research directions. In order to meet these objectives, this work is oriented toward answering the following research questions:

(1) What is the current status of research focusing on social media addiction?

(2) What are the key thematic areas in social media addiction and problematic use research?

(3) What is the intellectual structure of social media addiction as represented in the academic literature?

(4) What are the key findings of social media addiction and problematic social media research?

(5) What possible future research gaps can be identified in the field of social media addiction?

These research questions will be answered using bibliometric analysis of the literature on social media addiction and problematic use. This will allow for an overview of the research that has been conducted in this area, including information on the most influential authors, journals, countries of publication, and subject areas of study. Part 2 of the study will provide an examination of the intellectual structure of the extant literature in social media addiction while Part 3 will discuss the research methodology of the paper. Part 4 will discuss the findings of the study followed by a discussion under Part 5 of the paper. Finally, in Part 7, gaps in current knowledge about this field of research will be identified.

Literature review

Social media addiction research context.

Previous studies on behavioral addictions have looked at a lot of different factors that affect social media addiction focusing on personality traits. Although there is some inconsistency in the literature, numerous studies have focused on three main personality traits that may be associated with social media addiction, namely anxiety, depression, and extraversion ( 23 , 24 ).

It has been found that extraversion scores are strongly associated with increased use of social media and addiction to it ( 25 , 26 ). People with social anxiety as well as people who have psychiatric disorders often find online interactions extremely appealing ( 27 ). The available literature also reveals that the use of social media is positively associated with being female, single, and having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), or anxiety ( 28 ).

In a study by Seidman ( 29 ), the Big Five personality traits were assessed using Saucier's ( 30 ) Mini-Markers Scale. Results indicated that neurotic individuals use social media as a safe place for expressing their personality and meet belongingness needs. People affected by neurosis tend to use online social media to stay in touch with other people and feel better about their social lives ( 31 ). Narcissism is another factor that has been examined extensively when it comes to social media, and it has been found that people who are narcissistic are more likely to become addicted to social media ( 32 ). In this case users want to be seen and get “likes” from lots of other users. Longstreet and Brooks ( 33 ) did a study on how life satisfaction depends on how much money people make. Life satisfaction was found to be negatively linked to social media addiction, according to the results. When social media addiction decreases, the level of life satisfaction rises. But results show that in lieu of true-life satisfaction people use social media as a substitute (for temporary pleasure vs. longer term happiness).

Researchers have discovered similar patterns in students who tend to rank high in shyness: they find it easier to express themselves online rather than in person ( 34 , 35 ). With the use of social media, shy individuals have the opportunity to foster better quality relationships since many of their anxiety-related concerns (e.g., social avoidance and fear of social devaluation) are significantly reduced ( 36 , 37 ).

Problematic use of social media

The amount of research on problematic use of social media has dramatically increased since the last decade. But using social media in an unhealthy manner may not be considered an addiction or a disorder as this behavior has not yet been formally categorized as such ( 38 ). Although research has shown that people who use social media in a negative way often report negative health-related conditions, most of the data that have led to such results and conclusions comprise self-reported data ( 39 ). The dimensions of excessive social media usage are not exactly known because there are not enough diagnostic criteria and not enough high-quality long-term studies available yet. This is what Zendle and Bowden-Jones ( 40 ) noted in their own research. And this is why terms like “problematic social media use” have been used to describe people who use social media in a negative way. Furthermore, if a lot of time is spent on social media, it can be hard to figure out just when it is being used in a harmful way. For instance, people easily compare their appearance to what they see on social media, and this might lead to low self-esteem if they feel they do not look as good as the people they are following. According to research in this domain, the extent to which an individual engages in photo-related activities (e.g., taking selfies, editing photos, checking other people's photos) on social media is associated with negative body image concerns. Through curated online images of peers, adolescents face challenges to their self-esteem and sense of self-worth and are increasingly isolated from face-to-face interaction.

To address this problem the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) has been used by some scholars ( 41 , 42 ). These scholars have used criteria from the DSM-V to describe one problematic social media use, internet gaming disorder, but such criteria could also be used to describe other types of social media disorders. Franchina et al. ( 43 ) and Scott and Woods ( 44 ), for example, focus their attention on individual-level factors (like fear of missing out) and family-level factors (like childhood abuse) that have been used to explain why people use social media in a harmful way. Friends-level factors have also been explored as a social well-being measurement to explain why people use social media in a malevolent way and demonstrated significant positive correlations with lower levels of friend support ( 45 ). Macro-level factors have also been suggested, such as the normalization of surveillance ( 46 ) and the ability to see what people are doing online ( 47 ). Gender and age seem to be highly associated to the ways people use social media negatively. Particularly among girls, social media use is consistently associated with mental health issues ( 41 , 48 , 49 ), an association more common among older girls than younger girls ( 46 , 48 ).

Most studies have looked at the connection between social media use and its effects (such as social media addiction) and a number of different psychosomatic disorders. In a recent study conducted by Vannucci and Ohannessian ( 50 ), the use of social media appears to have a variety of effects “on psychosocial adjustment during early adolescence, with high social media use being the most problematic.” It has been found that people who use social media in a harmful way are more likely to be depressed, anxious, have low self-esteem, be more socially isolated, have poorer sleep quality, and have more body image dissatisfaction. Furthermore, harmful social media use has been associated with unhealthy lifestyle patterns (for example, not getting enough exercise or having trouble managing daily obligations) as well as life threatening behaviors such as illicit drug use, excessive alcohol consumption and unsafe sexual practices ( 51 , 52 ).

A growing body of research investigating social media use has revealed that the extensive use of social media platforms is correlated with a reduced performance on cognitive tasks and in mental effort ( 53 ). Overall, it appears that individuals who have a problematic relationship with social media or those who use social media more frequently are more likely to develop negative health conditions.

Social media addiction and problematic use systematic reviews

Previous studies have revealed the detrimental impacts of social media addiction on users' health. A systematic review by Khan and Khan ( 20 ) has pointed out that social media addiction has a negative impact on users' mental health. For example, social media addiction can lead to stress levels rise, loneliness, and sadness ( 54 ). Anxiety is another common mental health problem associated with social media addiction. Studies have found that young adolescents who are addicted to social media are more likely to suffer from anxiety than people who are not addicted to social media ( 55 ). In addition, social media addiction can also lead to physical health problems, such as obesity and carpal tunnel syndrome a result of spending too much time on the computer ( 22 ).

Apart from the negative impacts of social media addiction on users' mental and physical health, social media addiction can also lead to other problems. For example, social media addiction can lead to financial problems. A study by Sharif and Yeoh ( 56 ) has found that people who are addicted to social media tend to spend more money than those who are not addicted to social media. In addition, social media addiction can also lead to a decline in academic performance. Students who are addicted to social media are more likely to have lower grades than those who are not addicted to social media ( 57 ).

Research methodology

Bibliometric analysis.

Merigo et al. ( 58 ) use bibliometric analysis to examine, organize, and analyze a large body of literature from a quantitative, objective perspective in order to assess patterns of research and emerging trends in a certain field. A bibliometric methodology is used to identify the current state of the academic literature, advance research. and find objective information ( 59 ). This technique allows the researchers to examine previous scientific work, comprehend advancements in prior knowledge, and identify future study opportunities.

To achieve this objective and identify the research trends in social media addiction and problematic social media use, this study employs two bibliometric methodologies: performance analysis and science mapping. Performance analysis uses a series of bibliometric indicators (e.g., number of annual publications, document type, source type, journal impact factor, languages, subject area, h-index, and countries) and aims at evaluating groups of scientific actors on a particular topic of research. VOSviewer software ( 60 ) was used to carry out the science mapping. The software is used to visualize a particular body of literature and map the bibliographic material using the co-occurrence analysis of author, index keywords, nations, and fields of publication ( 61 , 62 ).

Data collection

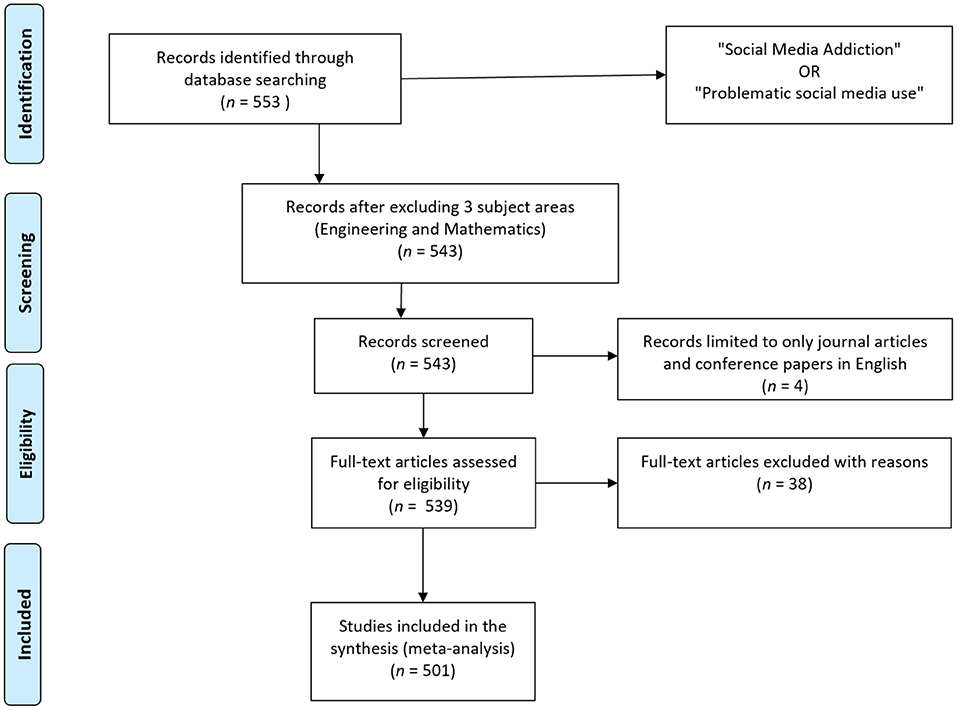

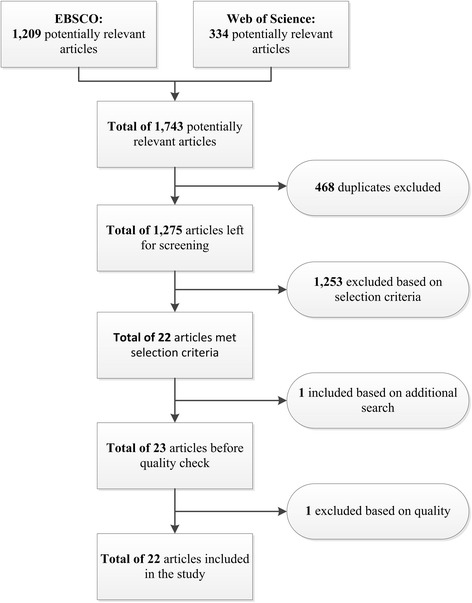

After picking keywords, designing the search strings, and building up a database, the authors conducted a bibliometric literature search. Scopus was utilized to gather exploration data since it is a widely used database that contains the most comprehensive view of the world's research output and provides one of the most effective search engines. If the research was to be performed using other database such as Web Of Science or Google Scholar the authors may have obtained larger number of articles however they may not have been all particularly relevant as Scopus is known to have the most widest and most relevant scholar search engine in marketing and social science. A keyword search for “social media addiction” OR “problematic social media use” yielded 553 papers, which were downloaded from Scopus. The information was gathered in March 2022, and because the Scopus database is updated on a regular basis, the results may change in the future. Next, the authors examined the titles and abstracts to see whether they were relevant to the topics treated. There were two common grounds for document exclusion. First, while several documents emphasized the negative effects of addiction in relation to the internet and digital media, they did not focus on social networking sites specifically. Similarly, addiction and problematic consumption habits were discussed in relation to social media in several studies, although only in broad terms. This left a total of 511 documents. Articles were then limited only to journal articles, conference papers, reviews, books, and only those published in English. This process excluded 10 additional documents. Then, the relevance of the remaining articles was finally checked by reading the titles, abstracts, and keywords. Documents were excluded if social networking sites were only mentioned as a background topic or very generally. This resulted in a final selection of 501 research papers, which were then subjected to bibliometric analysis (see Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) flowchart showing the search procedures used in the review.

After identifying 501 Scopus files, bibliographic data related to these documents were imported into an Excel sheet where the authors' names, their affiliations, document titles, keywords, abstracts, and citation figures were analyzed. These were subsequently uploaded into VOSViewer software version 1.6.8 to begin the bibliometric review. Descriptive statistics were created to define the whole body of knowledge about social media addiction and problematic social media use. VOSViewer was used to analyze citation, co-citation, and keyword co-occurrences. According to Zupic and Cater ( 63 ), co-citation analysis measures the influence of documents, authors, and journals heavily cited and thus considered influential. Co-citation analysis has the objective of building similarities between authors, journals, and documents and is generally defined as the frequency with which two units are cited together within the reference list of a third article.

The implementation of social media addiction performance analysis was conducted according to the models recently introduced by Karjalainen et al. ( 64 ) and Pattnaik ( 65 ). Throughout the manuscript there are operational definitions of relevant terms and indicators following a standardized bibliometric approach. The cumulative academic impact (CAI) of the documents was measured by the number of times they have been cited in other scholarly works while the fine-grained academic impact (FIA) was computed according to the authors citation analysis and authors co-citation analysis within the reference lists of documents that have been specifically focused on social media addiction and problematic social media use.

Results of the study presented here include the findings on social media addiction and social media problematic use. The results are presented by the foci outlined in the study questions.

Volume, growth trajectory, and geographic distribution of the literature

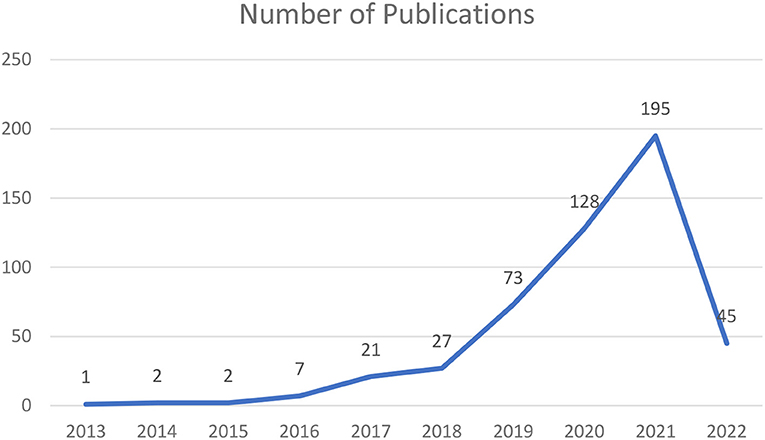

After performing the Scopus-based investigation of the current literature regarding social media addiction and problematic use of social media, the authors obtained a knowledge base consisting of 501 documents comprising 455 journal articles, 27 conference papers, 15 articles reviews, 3 books and 1 conference review. The included literature was very recent. As shown in Figure 2 , publication rates started very slowly in 2013 but really took off in 2018, after which publications dramatically increased each year until a peak was reached in 2021 with 195 publications. Analyzing the literature published during the past decade reveals an exponential increase in scholarly production on social addiction and its problematic use. This might be due to the increasingly widespread introduction of social media sites in everyday life and the ubiquitous diffusion of mobile devices that have fundamentally impacted human behavior. The dip in the number of publications in 2022 is explained by the fact that by the time the review was carried out the year was not finished yet and therefore there are many articles still in press.

Figure 2 . Annual volume of social media addiction or social media problematic use ( n = 501).

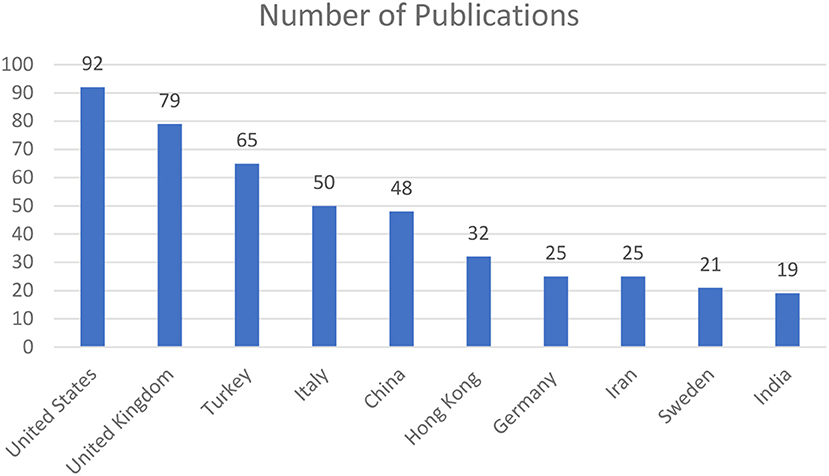

The geographical distribution trends of scholarly publications on social media addiction or problematic use of social media are highlighted in Figure 3 . The articles were assigned to a certain country according to the nationality of the university with whom the first author was affiliated with. The figure shows that the most productive countries are the USA (92), the U.K. (79), and Turkey ( 63 ), which combined produced 236 articles, equal to 47% of the entire scholarly production examined in this bibliometric analysis. Turkey has slowly evolved in various ways with the growth of the internet and social media. Anglo-American scholarly publications on problematic social media consumer behavior represent the largest research output. Yet it is interesting to observe that social networking sites studies are attracting many researchers in Asian countries, particularly China. For many Chinese people, social networking sites are a valuable opportunity to involve people in political activism in addition to simply making purchases ( 66 ).

Figure 3 . Global dispersion of social networking sites in relation to social media addiction or social media problematic use.

Analysis of influential authors

This section analyses the high-impact authors in the Scopus-indexed knowledge base on social networking sites in relation to social media addiction or problematic use of social media. It provides valuable insights for establishing patterns of knowledge generation and dissemination of literature about social networking sites relating to addiction and problematic use.

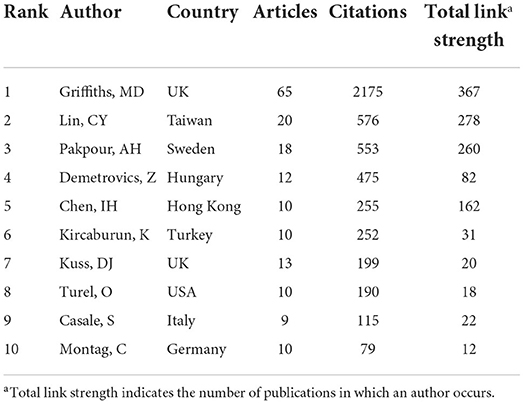

Table 1 acknowledges the top 10 most highly cited authors with the highest total citations in the database.

Table 1 . Highly cited authors on social media addiction and problematic use ( n = 501).

Table 1 shows that MD Griffiths (sixty-five articles), CY Lin (twenty articles), and AH Pakpour (eighteen articles) are the most productive scholars according to the number of Scopus documents examined in the area of social media addiction and its problematic use . If the criteria are changed and authors ranked according to the overall number of citations received in order to determine high-impact authors, the same three authors turn out to be the most highly cited authors. It should be noted that these highly cited authors tend to enlist several disciplines in examining social media addiction and problematic use. Griffiths, for example, focuses on behavioral addiction stemming from not only digital media usage but also from gambling and video games. Lin, on the other hand, focuses on the negative effects that the internet and digital media can have on users' mental health, and Pakpour approaches the issue from a behavioral medicine perspective.

Intellectual structure of the literature

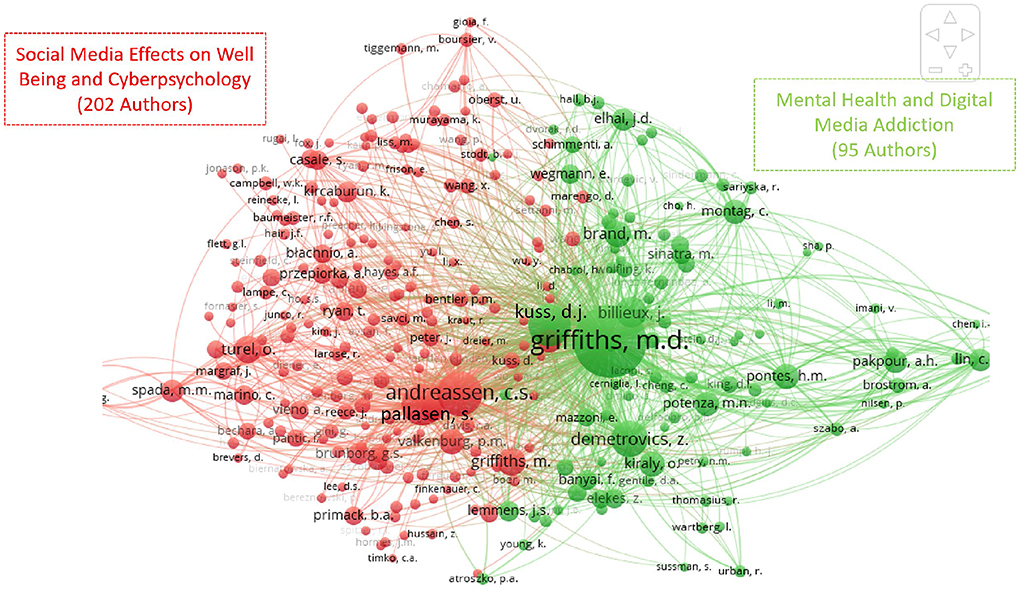

In this part of the paper, the authors illustrate the “intellectual structure” of the social media addiction and the problematic use of social media's literature. An author co-citation analysis (ACA) was performed which is displayed as a figure that depicts the relations between highly co-cited authors. The study of co-citation assumes that strongly co-cited authors carry some form of intellectual similarity ( 67 ). Figure 4 shows the author co-citation map. Nodes represent units of analysis (in this case scholars) and network ties represent similarity connections. Nodes are sized according to the number of co-citations received—the bigger the node, the more co-citations it has. Adjacent nodes are considered intellectually similar.

Figure 4 . Two clusters, representing the intellectual structure of the social media and its problematic use literature.

Scholars belonging to the green cluster (Mental Health and Digital Media Addiction) have extensively published on medical analysis tools and how these can be used to heal users suffering from addiction to digital media, which can range from gambling, to internet, to videogame addictions. Scholars in this school of thought focus on the negative effects on users' mental health, such as depression, anxiety, and personality disturbances. Such studies focus also on the role of screen use in the development of mental health problems and the increasing use of medical treatments to address addiction to digital media. They argue that addiction to digital media should be considered a mental health disorder and treatment options should be made available to users.

In contrast, scholars within the red cluster (Social Media Effects on Well Being and Cyberpsychology) have focused their attention on the effects of social media toward users' well-being and how social media change users' behavior, focusing particular attention on the human-machine interaction and how methods and models can help protect users' well-being. Two hundred and two authors belong to this group, the top co-cited being Andreassen (667 co-citations), Pallasen (555 co-citations), and Valkenburg (215 co-citations). These authors have extensively studied the development of addiction to social media, problem gambling, and internet addiction. They have also focused on the measurement of addiction to social media, cyberbullying, and the dark side of social media.

Most influential source title in the field of social media addiction and its problematic use

To find the preferred periodicals in the field of social media addiction and its problematic use, the authors have selected 501 articles published in 263 journals. Table 2 gives a ranked list of the top 10 journals that constitute the core publishing sources in the field of social media addiction research. In doing so, the authors analyzed the journal's impact factor, Scopus Cite Score, h-index, quartile ranking, and number of publications per year.

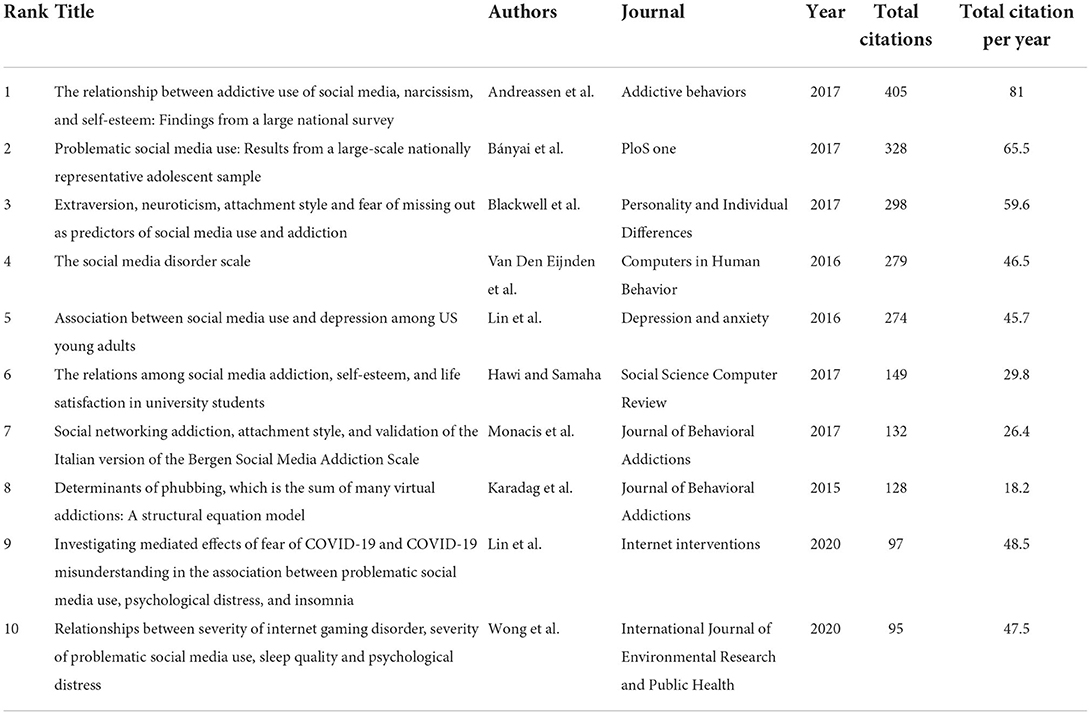

Table 2 . Top 10 most cited and more frequently mentioned documents in the field of social media addiction.

The journal Addictive Behaviors topped the list, with 700 citations and 22 publications (4.3%), followed by Computers in Human Behaviors , with 577 citations and 13 publications (2.5%), Journal of Behavioral Addictions , with 562 citations and 17 publications (3.3%), and International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction , with 502 citations and 26 publications (5.1%). Five of the 10 most productive journals in the field of social media addiction research are published by Elsevier (all Q1 rankings) while Springer and Frontiers Media published one journal each.

Documents citation analysis identified the most influential and most frequently mentioned documents in a certain scientific field. Andreassen has received the most citations among the 10 most significant papers on social media addiction, with 405 ( Table 2 ). The main objective of this type of studies was to identify the associations and the roles of different variables as predictors of social media addiction (e.g., ( 19 , 68 , 69 )). According to general addiction models, the excessive and problematic use of digital technologies is described as “being overly concerned about social media, driven by an uncontrollable motivation to log on to or use social media, and devoting so much time and effort to social media that it impairs other important life areas” ( 27 , 70 ). Furthermore, the purpose of several highly cited studies ( 31 , 71 ) was to analyse the connections between young adults' sleep quality and psychological discomfort, depression, self-esteem, and life satisfaction and the severity of internet and problematic social media use, since the health of younger generations and teenagers is of great interest this may help explain the popularity of such papers. Despite being the most recent publication Lin et al.'s work garnered more citations annually. The desire to quantify social media addiction in individuals can also help explain the popularity of studies which try to develop measurement scales ( 42 , 72 ). Some of the highest-ranked publications are devoted to either the presentation of case studies or testing relationships among psychological constructs ( 73 ).

Keyword co-occurrence analysis

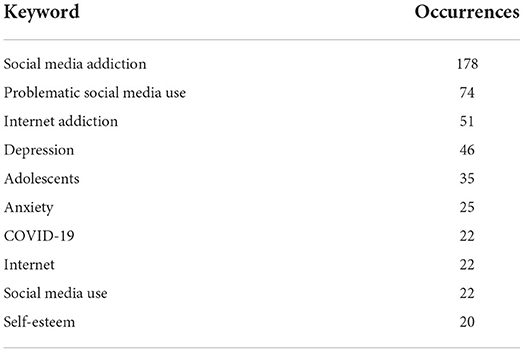

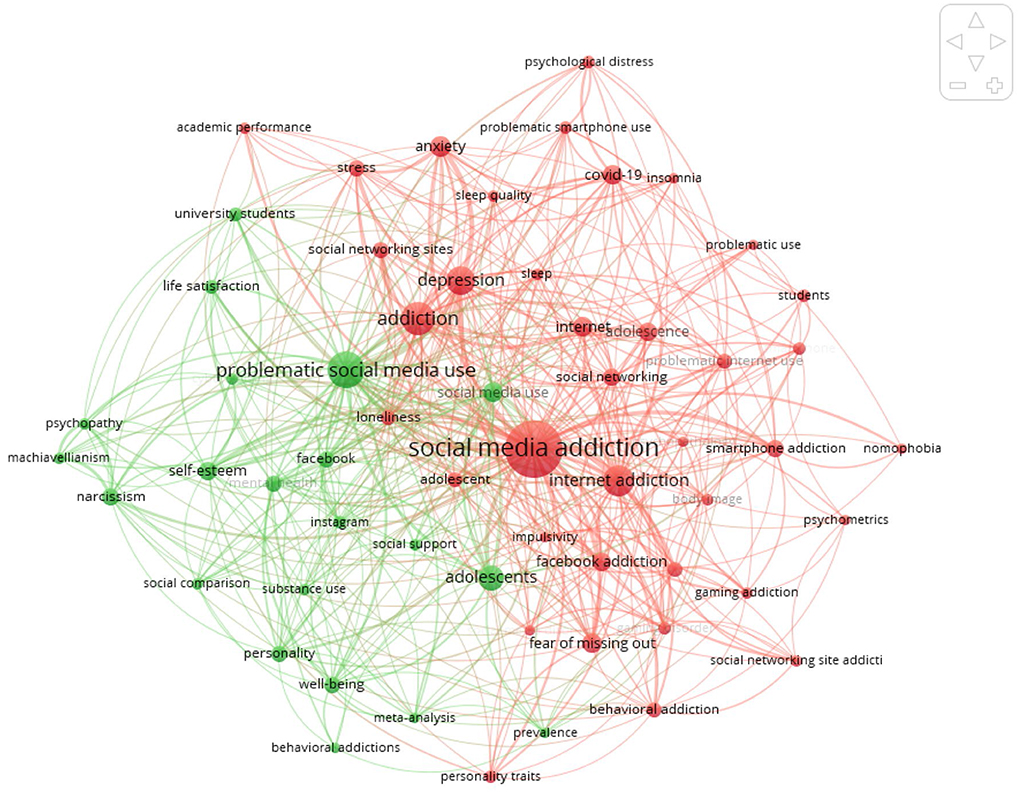

The research question, “What are the key thematic areas in social media addiction literature?” was answered using keyword co-occurrence analysis. Keyword co-occurrence analysis is conducted to identify research themes and discover keywords. It mainly examines the relationships between co-occurrence keywords in a wide variety of literature ( 74 ). In this approach, the idea is to explore the frequency of specific keywords being mentioned together.

Utilizing VOSviewer, the authors conducted a keyword co-occurrence analysis to characterize and review the developing trends in the field of social media addiction. The top 10 most frequent keywords are presented in Table 3 . The results indicate that “social media addiction” is the most frequent keyword (178 occurrences), followed by “problematic social media use” (74 occurrences), “internet addiction” (51 occurrences), and “depression” (46 occurrences). As shown in the co-occurrence network ( Figure 5 ), the keywords can be grouped into two major clusters. “Problematic social media use” can be identified as the core theme of the green cluster. In the red cluster, keywords mainly identify a specific aspect of problematic social media use: social media addiction.

Table 3 . Frequency of occurrence of top 10 keywords.

Figure 5 . Keywords co-occurrence map. Threshold: 5 co-occurrences.

The results of the keyword co-occurrence analysis for journal articles provide valuable perspectives and tools for understanding concepts discussed in past studies of social media usage ( 75 ). More precisely, it can be noted that there has been a large body of research on social media addiction together with other types of technological addictions, such as compulsive web surfing, internet gaming disorder, video game addiction and compulsive online shopping ( 76 – 78 ). This field of research has mainly been directed toward teenagers, middle school students, and college students and university students in order to understand the relationship between social media addiction and mental health issues such as depression, disruptions in self-perceptions, impairment of social and emotional activity, anxiety, neuroticism, and stress ( 79 – 81 ).

The findings presented in this paper show that there has been an exponential increase in scholarly publications—from two publications in 2013 to 195 publications in 2021. There were 45 publications in 2022 at the time this study was conducted. It was interesting to observe that the US, the UK, and Turkey accounted for 47% of the publications in this field even though none of these countries are in the top 15 countries in terms of active social media penetration ( 82 ) although the US has the third highest number of social media users ( 83 ). Even though China and India have the highest number of social media users ( 83 ), first and second respectively, they rank fifth and tenth in terms of publications on social media addiction or problematic use of social media. In fact, the US has almost double the number of publications in this field compared to China and almost five times compared to India. Even though East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia make up the top three regions in terms of worldwide social media users ( 84 ), except for China and India there have been only a limited number of publications on social media addiction or problematic use. An explanation for that could be that there is still a lack of awareness on the negative consequences of the use of social media and the impact it has on the mental well-being of users. More research in these regions should perhaps be conducted in order to understand the problematic use and addiction of social media so preventive measures can be undertaken.

From the bibliometric analysis, it was found that most of the studies examined used quantitative methods in analyzing data and therefore aimed at testing relationships between variables. In addition, many studies were empirical, aimed at testing relationships based on direct or indirect observations of social media use. Very few studies used theories and for the most part if they did they used the technology acceptance model and social comparison theories. The findings presented in this paper show that none of the studies attempted to create or test new theories in this field, perhaps due to the lack of maturity of the literature. Moreover, neither have very many qualitative studies been conducted in this field. More qualitative research in this field should perhaps be conducted as it could explore the motivations and rationales from which certain users' behavior may arise.

The authors found that almost all the publications on social media addiction or problematic use relied on samples of undergraduate students between the ages of 19–25. The average daily time spent by users worldwide on social media applications was highest for users between the ages of 40–44, at 59.85 min per day, followed by those between the ages of 35–39, at 59.28 min per day, and those between the ages of 45–49, at 59.23 per day ( 85 ). Therefore, more studies should be conducted exploring different age groups, as users between the ages of 19–25 do not represent the entire population of social media users. Conducting studies on different age groups may yield interesting and valuable insights to the field of social media addiction. For example, it would be interesting to measure the impacts of social media use among older users aged 50 years or older who spend almost the same amount of time on social media as other groups of users (56.43 min per day) ( 85 ).

A majority of the studies tested social media addiction or problematic use based on only two social media platforms: Facebook and Instagram. Although Facebook and Instagram are ranked first and fourth in terms of most popular social networks by number of monthly users, it would be interesting to study other platforms such as YouTube, which is ranked second, and WhatsApp, which is ranked third ( 86 ). Furthermore, TikTok would also be an interesting platform to study as it has grown in popularity in recent years, evident from it being the most downloaded application in 2021, with 656 million downloads ( 87 ), and is ranked second in Q1 of 2022 ( 88 ). Moreover, most of the studies focused only on one social media platform. Comparing different social media platforms would yield interesting results because each platform is different in terms of features, algorithms, as well as recommendation engines. The purpose as well as the user behavior for using each platform is also different, therefore why users are addicted to these platforms could provide a meaningful insight into social media addiction and problematic social media use.

Lastly, most studies were cross-sectional, and not longitudinal, aiming at describing results over a certain point in time and not over a long period of time. A longitudinal study could better describe the long-term effects of social media use.

This study was conducted to review the extant literature in the field of social media and analyze the global research productivity during the period ranging from 2013 to 2022. The study presents a bibliometric overview of the leading trends with particular regard to “social media addiction” and “problematic social media use.” The authors applied science mapping to lay out a knowledge base on social media addiction and its problematic use. This represents the first large-scale analysis in this area of study.

A keyword search of “social media addiction” OR “problematic social media use” yielded 553 papers, which were downloaded from Scopus. After performing the Scopus-based investigation of the current literature regarding social media addiction and problematic use, the authors ended up with a knowledge base consisting of 501 documents comprising 455 journal articles, 27 conference papers, 15 articles reviews, 3 books, and 1 conference review.

The geographical distribution trends of scholarly publications on social media addiction or problematic use indicate that the most productive countries were the USA (92), the U.K. (79), and Turkey ( 63 ), which together produced 236 articles. Griffiths (sixty-five articles), Lin (twenty articles), and Pakpour (eighteen articles) were the most productive scholars according to the number of Scopus documents examined in the area of social media addiction and its problematic use. An author co-citation analysis (ACA) was conducted which generated a layout of social media effects on well-being and cyber psychology as well as mental health and digital media addiction in the form of two research literature clusters representing the intellectual structure of social media and its problematic use.

The preferred periodicals in the field of social media addiction and its problematic use were Addictive Behaviors , with 700 citations and 22 publications, followed by Computers in Human Behavior , with 577 citations and 13 publications, and Journal of Behavioral Addictions , with 562 citations and 17 publications. Keyword co-occurrence analysis was used to investigate the key thematic areas in the social media literature, as represented by the top three keyword phrases in terms of their frequency of occurrence, namely, “social media addiction,” “problematic social media use,” and “social media addiction.”

This research has a few limitations. The authors used science mapping to improve the comprehension of the literature base in this review. First and foremost, the authors want to emphasize that science mapping should not be utilized in place of established review procedures, but rather as a supplement. As a result, this review can be considered the initial stage, followed by substantive research syntheses that examine findings from recent research. Another constraint stems from how 'social media addiction' is defined. The authors overcame this limitation by inserting the phrase “social media addiction” OR “problematic social media use” in the search string. The exclusive focus on SCOPUS-indexed papers creates a third constraint. The SCOPUS database has a larger number of papers than does Web of Science although it does not contain all the publications in a given field.

Although the total body of literature on social media addiction is larger than what is covered in this review, the use of co-citation analyses helped to mitigate this limitation. This form of bibliometric study looks at all the publications listed in the reference list of the extracted SCOPUS database documents. As a result, a far larger dataset than the one extracted from SCOPUS initially has been analyzed.

The interpretation of co-citation maps should be mentioned as a last constraint. The reason is that the procedure is not always clear, so scholars must have a thorough comprehension of the knowledge base in order to make sense of the result of the analysis ( 63 ). This issue was addressed by the authors' expertise, but it remains somewhat subjective.

Implications

The findings of this study have implications mainly for government entities and parents. The need for regulation of social media addiction is evident when considering the various risks associated with habitual social media use. Social media addiction may lead to negative consequences for adolescents' school performance, social behavior, and interpersonal relationships. In addition, social media addiction may also lead to other risks such as sexting, social media stalking, cyber-bullying, privacy breaches, and improper use of technology. Given the seriousness of these risks, it is important to have regulations in place to protect adolescents from the harms of social media addiction.

Regulation of social media platforms

One way that regulation could help protect adolescents from the harms of social media addiction is by limiting their access to certain websites or platforms. For example, governments could restrict adolescents' access to certain websites or platforms during specific hours of the day. This would help ensure that they are not spending too much time on social media and are instead focusing on their schoolwork or other important activities.

Another way that regulation could help protect adolescents from the harms of social media addiction is by requiring companies to put warning labels on their websites or apps. These labels would warn adolescents about the potential risks associated with excessive use of social media.

Finally, regulation could also require companies to provide information about how much time each day is recommended for using their website or app. This would help adolescents make informed decisions about how much time they want to spend on social media each day. These proposed regulations would help to protect children from the dangers of social media, while also ensuring that social media companies are more transparent and accountable to their users.

Parental involvement in adolescents' social media use

Parents should be involved in their children's social media use to ensure that they are using these platforms safely and responsibly. Parents can monitor their children's online activity, set time limits for social media use, and talk to their children about the risks associated with social media addiction.

Education on responsible social media use

Adolescents need to be educated about responsible social media use so that they can enjoy the benefits of these platforms while avoiding the risks associated with addiction. Education on responsible social media use could include topics such as cyber-bullying, sexting, and privacy breaches.

Research directions for future studies

A content analysis was conducted to answer the fifth research questions “What are the potential research directions for addressing social media addiction in the future?” The study reveals that there is a lack of screening instruments and diagnostic criteria to assess social media addiction. Validated DSM-V-based instruments could shed light on the factors behind social media use disorder. Diagnostic research may be useful in order to understand social media behavioral addiction and gain deeper insights into the factors responsible for psychological stress and psychiatric disorders. In addition to cross-sectional studies, researchers should also conduct longitudinal studies and experiments to assess changes in users' behavior over time ( 20 ).

Another important area to examine is the role of engagement-based ranking and recommendation algorithms in online habit formation. More research is required to ascertain how algorithms determine which content type generates higher user engagement. A clear understanding of the way social media platforms gather content from users and amplify their preferences would lead to the development of a standardized conceptualization of social media usage patterns ( 89 ). This may provide a clearer picture of the factors that lead to problematic social media use and addiction. It has been noted that “misinformation, toxicity, and violent content are inordinately prevalent” in material reshared by users and promoted by social media algorithms ( 90 ).

Additionally, an understanding of engagement-based ranking models and recommendation algorithms is essential in order to implement appropriate public policy measures. To address the specific behavioral concerns created by social media, legislatures must craft appropriate statutes. Thus, future qualitative research to assess engagement based ranking frameworks is extremely necessary in order to provide a broader perspective on social media use and tackle key regulatory gaps. Particular emphasis must be placed on consumer awareness, algorithm bias, privacy issues, ethical platform design, and extraction and monetization of personal data ( 91 ).