Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing Essays in Art History

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Art History Analysis – Formal Analysis and Stylistic Analysis

Typically in an art history class the main essay students will need to write for a final paper or for an exam is a formal or stylistic analysis.

A formal analysis is just what it sounds like – you need to analyze the form of the artwork. This includes the individual design elements – composition, color, line, texture, scale, contrast, etc. Questions to consider in a formal analysis is how do all these elements come together to create this work of art? Think of formal analysis in relation to literature – authors give descriptions of characters or places through the written word. How does an artist convey this same information?

Organize your information and focus on each feature before moving onto the text – it is not ideal to discuss color and jump from line to then in the conclusion discuss color again. First summarize the overall appearance of the work of art – is this a painting? Does the artist use only dark colors? Why heavy brushstrokes? etc and then discuss details of the object – this specific animal is gray, the sky is missing a moon, etc. Again, it is best to be organized and focused in your writing – if you discuss the animals and then the individuals and go back to the animals you run the risk of making your writing unorganized and hard to read. It is also ideal to discuss the focal of the piece – what is in the center? What stands out the most in the piece or takes up most of the composition?

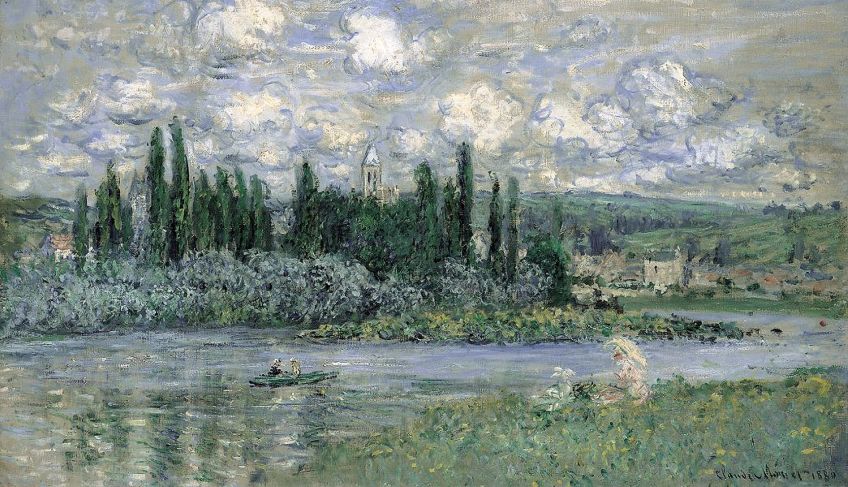

A stylistic approach can be described as an indicator of unique characteristics that analyzes and uses the formal elements (2-D: Line, color, value, shape and 3-D all of those and mass).The point of style is to see all the commonalities in a person’s works, such as the use of paint and brush strokes in Van Gogh’s work. Style can distinguish an artist’s work from others and within their own timeline, geographical regions, etc.

Methods & Theories To Consider:

Expressionism

Instructuralism

Postmodernism

Social Art History

Biographical Approach

Poststructuralism

Museum Studies

Visual Cultural Studies

Stylistic Analysis Example:

The following is a brief stylistic analysis of two Greek statues, an example of how style has changed because of the “essence of the age.” Over the years, sculptures of women started off as being plain and fully clothed with no distinct features, to the beautiful Venus/Aphrodite figures most people recognize today. In the mid-seventh century to the early fifth, life-sized standing marble statues of young women, often elaborately dress in gaily painted garments were created known as korai. The earliest korai is a Naxian women to Artemis. The statue wears a tight-fitted, belted peplos, giving the body a very plain look. The earliest korai wore the simpler Dorian peplos, which was a heavy woolen garment. From about 530, most wear a thinner, more elaborate, and brightly painted Ionic linen and himation. A largely contrasting Greek statue to the korai is the Venus de Milo. The Venus from head to toe is six feet seven inches tall. Her hips suggest that she has had several children. Though her body shows to be heavy, she still seems to almost be weightless. Viewing the Venus de Milo, she changes from side to side. From her right side she seems almost like a pillar and her leg bears most of the weight. She seems be firmly planted into the earth, and since she is looking at the left, her big features such as her waist define her. The Venus de Milo had a band around her right bicep. She had earrings that were brutally stolen, ripping her ears away. Venus was noted for loving necklaces, so it is very possibly she would have had one. It is also possible she had a tiara and bracelets. Venus was normally defined as “golden,” so her hair would have been painted. Two statues in the same region, have throughout history, changed in their style.

Compare and Contrast Essay

Most introductory art history classes will ask students to write a compare and contrast essay about two pieces – examples include comparing and contrasting a medieval to a renaissance painting. It is always best to start with smaller comparisons between the two works of art such as the medium of the piece. Then the comparison can include attention to detail so use of color, subject matter, or iconography. Do the same for contrasting the two pieces – start small. After the foundation is set move on to the analysis and what these comparisons or contrasting material mean – ‘what is the bigger picture here?’ Consider why one artist would wish to show the same subject matter in a different way, how, when, etc are all questions to ask in the compare and contrast essay. If during an exam it would be best to quickly outline the points to make before tackling writing the essay.

Compare and Contrast Example:

Stele of Hammurabi from Susa (modern Shush, Iran), ca. 1792 – 1750 BCE, Basalt, height of stele approx. 7’ height of relief 28’

Stele, relief sculpture, Art as propaganda – Hammurabi shows that his law code is approved by the gods, depiction of land in background, Hammurabi on the same place of importance as the god, etc.

Top of this stele shows the relief image of Hammurabi receiving the law code from Shamash, god of justice, Code of Babylonian social law, only two figures shown, different area and time period, etc.

Stele of Naram-sin , Sippar Found at Susa c. 2220 - 2184 bce. Limestone, height 6'6"

Stele, relief sculpture, Example of propaganda because the ruler (like the Stele of Hammurabi) shows his power through divine authority, Naramsin is the main character due to his large size, depiction of land in background, etc.

Akkadian art, made of limestone, the stele commemorates a victory of Naramsin, multiple figures are shown specifically soldiers, different area and time period, etc.

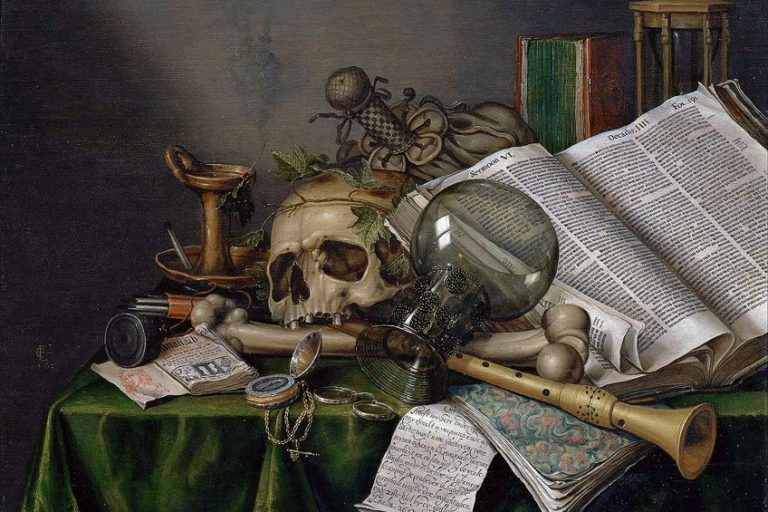

Iconography

Regardless of what essay approach you take in class it is absolutely necessary to understand how to analyze the iconography of a work of art and to incorporate into your paper. Iconography is defined as subject matter, what the image means. For example, why do things such as a small dog in a painting in early Northern Renaissance paintings represent sexuality? Additionally, how can an individual perhaps identify these motifs that keep coming up?

The following is a list of symbols and their meaning in Marriage a la Mode by William Hogarth (1743) that is a series of six paintings that show the story of marriage in Hogarth’s eyes.

- Man has pockets turned out symbolizing he has lost money and was recently in a fight by the state of his clothes.

- Lap dog shows loyalty but sniffs at woman’s hat in the husband’s pocket showing sexual exploits.

- Black dot on husband’s neck believed to be symbol of syphilis.

- Mantel full of ugly Chinese porcelain statues symbolizing that the couple has no class.

- Butler had to go pay bills, you can tell this by the distasteful look on his face and that his pockets are stuffed with bills and papers.

- Card game just finished up, women has directions to game under foot, shows her easily cheating nature.

- Paintings of saints line a wall of the background room, isolated from the living, shows the couple’s complete disregard to faith and religion.

- The dangers of sexual excess are underscored in the Hograth by placing Cupid among ruins, foreshadowing the inevitable ruin of the marriage.

- Eventually the series (other five paintings) shows that the woman has an affair, the men duel and die, the woman hangs herself and the father takes her ring off her finger symbolizing the one thing he could salvage from the marriage.

Art History

What this handout is about.

This handout discusses a few common assignments found in art history courses. To help you better understand those assignments, this handout highlights key strategies for approaching and analyzing visual materials.

Writing in art history

Evaluating and writing about visual material uses many of the same analytical skills that you have learned from other fields, such as history or literature. In art history, however, you will be asked to gather your evidence from close observations of objects or images. Beyond painting, photography, and sculpture, you may be asked to write about posters, illustrations, coins, and other materials.

Even though art historians study a wide range of materials, there are a few prevalent assignments that show up throughout the field. Some of these assignments (and the writing strategies used to tackle them) are also used in other disciplines. In fact, you may use some of the approaches below to write about visual sources in classics, anthropology, and religious studies, to name a few examples.

This handout describes three basic assignment types and explains how you might approach writing for your art history class.Your assignment prompt can often be an important step in understanding your course’s approach to visual materials and meeting its specific expectations. Start by reading the prompt carefully, and see our handout on understanding assignments for some tips and tricks.

Three types of assignments are discussed below:

- Visual analysis essays

- Comparison essays

- Research papers

1. Visual analysis essays

Visual analysis essays often consist of two components. First, they include a thorough description of the selected object or image based on your observations. This description will serve as your “evidence” moving forward. Second, they include an interpretation or argument that is built on and defended by this visual evidence.

Formal analysis is one of the primary ways to develop your observations. Performing a formal analysis requires describing the “formal” qualities of the object or image that you are describing (“formal” here means “related to the form of the image,” not “fancy” or “please, wear a tuxedo”). Formal elements include everything from the overall composition to the use of line, color, and shape. This process often involves careful observations and critical questions about what you see.

Pre-writing: observations and note-taking

To assist you in this process, the chart below categorizes some of the most common formal elements. It also provides a few questions to get you thinking.

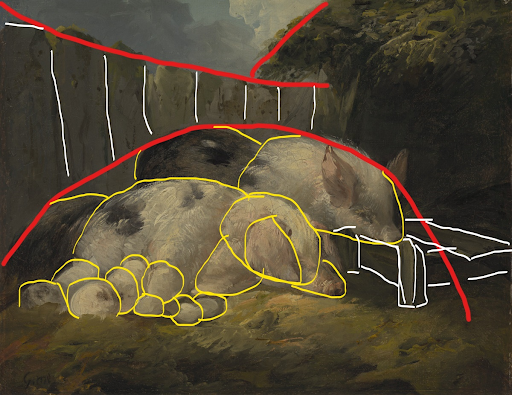

Let’s try this out with an example. You’ve been asked to write a formal analysis of the painting, George Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty , ca. 1800 (created in Britain and now in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond).

What do you notice when you see this image? First, you might observe that this is a painting. Next, you might ask yourself some of the following questions: what kind of paint was used, and what was it painted on? How has the artist applied the paint? What does the scene depict, and what kinds of figures (an art-historical term that generally refers to humans) or animals are present? What makes these animals similar or different? How are they arranged? What colors are used in this painting? Are there any colors that pop out or contrast with the others? What might the artist have been trying to accomplish by adding certain details?

What other questions come to mind while examining this work? What kinds of topics come up in class when you discuss paintings like this one? Consider using your class experiences as a model for your own description! This process can be lengthy, so expect to spend some time observing the artwork and brainstorming.

Here is an example of some of the notes one might take while viewing Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty :

Composition

- The animals, four pigs total, form a gently sloping mound in the center of the painting.

- The upward mound of animals contrasts with the downward curve of the wooden fence.

- The gentle light, coming from the upper-left corner, emphasizes the animals in the center. The rest of the scene is more dimly lit.

- The composition is asymmetrical but balanced. The fence is balanced by the bush on the right side of the painting, and the sow with piglets is balanced by the pig whose head rests in the trough.

- Throughout the composition, the colors are generally muted and rather limited. Yellows, greens, and pinks dominate the foreground, with dull browns and blues in the background.

- Cool colors appear in the background, and warm colors appear in the foreground, which makes the foreground more prominent.

- Large areas of white with occasional touches of soft pink focus attention on the pigs.

- The paint is applied very loosely, meaning the brushstrokes don’t describe objects with exact details but instead suggest them with broad gestures.

- The ground has few details and appears almost abstract.

- The piglets emerge from a series of broad, almost indistinct, circular strokes.

- The painting contrasts angular lines and rectangles (some vertical, some diagonal) with the circular forms of the pig.

- The negative space created from the intersection of the fence and the bush forms a wide, inverted triangle that points downward. The point directs viewers’ attention back to the pigs.

Because these observations can be difficult to notice by simply looking at a painting, art history instructors sometimes encourage students to sketch the work that they’re describing. The image below shows how a sketch can reveal important details about the composition and shapes.

Writing: developing an interpretation

Once you have your descriptive information ready, you can begin to think critically about what the information in your notes might imply. What are the effects of the formal elements? How do these elements influence your interpretation of the object?

Your interpretation does not need to be earth-shatteringly innovative, but it should put forward an argument with which someone else could reasonably disagree. In other words, you should work on developing a strong analytical thesis about the meaning, significance, or effect of the visual material that you’ve described. For more help in crafting a strong argument, see our Thesis Statements handout .

For example, based on the notes above, you might draft the following thesis statement:

In Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty, the close proximity of the pigs to each other–evident in the way Morland has overlapped the pigs’ bodies and grouped them together into a gently sloping mound–and the soft atmosphere that surrounds them hints at the tranquility of their humble farm lives.

Or, you could make an argument about one specific formal element:

In Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty, the sharp contrast between rectilinear, often vertical, shapes and circular masses focuses viewers’ attention on the pigs, who seem undisturbed by their enclosure.

Support your claims

Your thesis statement should be defended by directly referencing the formal elements of the artwork. Try writing with enough specificity that someone who has not seen the work could imagine what it looks like. If you are struggling to find a certain term, try using this online art dictionary: Tate’s Glossary of Art Terms .

Your body paragraphs should explain how the elements work together to create an overall effect. Avoid listing the elements. Instead, explain how they support your analysis.

As an example, the following body paragraph illustrates this process using Morland’s painting:

Morland achieves tranquility not only by grouping animals closely but also by using light and shadow carefully. Light streams into the foreground through an overcast sky, in effect dappling the pigs and the greenery that encircles them while cloaking much of the surrounding scene. Diffuse and soft, the light creates gentle gradations of tone across pigs’ bodies rather than sharp contrasts of highlights and shadows. By modulating the light in such subtle ways, Morland evokes a quiet, even contemplative mood that matches the restful faces of the napping pigs.

This example paragraph follows the 5-step process outlined in our handout on paragraphs . The paragraph begins by stating the main idea, in this case that the artist creates a tranquil scene through the use of light and shadow. The following two sentences provide evidence for that idea. Because art historians value sophisticated descriptions, these sentences include evocative verbs (e.g., “streams,” “dappling,” “encircles”) and adjectives (e.g., “overcast,” “diffuse,” “sharp”) to create a mental picture of the artwork in readers’ minds. The last sentence ties these observations together to make a larger point about the relationship between formal elements and subject matter.

There are usually different arguments that you could make by looking at the same image. You might even find a way to combine these statements!

Remember, however you interpret the visual material (for example, that the shapes draw viewers’ attention to the pigs), the interpretation needs to be logically supported by an observation (the contrast between rectangular and circular shapes). Once you have an argument, consider the significance of these statements. Why does it matter if this painting hints at the tranquility of farm life? Why might the artist have tried to achieve this effect? Briefly discussing why these arguments matter in your thesis can help readers understand the overall significance of your claims. This step may even lead you to delve deeper into recurring themes or topics from class.

Tread lightly

Avoid generalizing about art as a whole, and be cautious about making claims that sound like universal truths. If you find yourself about to say something like “across cultures, blue symbolizes despair,” pause to consider the statement. Would all people, everywhere, from the beginning of human history to the present agree? How do you know? If you find yourself stating that “art has meaning,” consider how you could explain what you see as the specific meaning of the artwork.

Double-check your prompt. Do you need secondary sources to write your paper? Most visual analysis essays in art history will not require secondary sources to write the paper. Rely instead on your close observation of the image or object to inform your analysis and use your knowledge from class to support your argument. Are you being asked to use the same methods to analyze objects as you would for paintings? Be sure to follow the approaches discussed in class.

Some classes may use “description,” “formal analysis” and “visual analysis” as synonyms, but others will not. Typically, a visual analysis essay may ask you to consider how form relates to the social, economic, or political context in which these visual materials were made or exhibited, whereas a formal analysis essay may ask you to make an argument solely about form itself. If your prompt does ask you to consider contextual aspects, and you don’t feel like you can address them based on knowledge from the course, consider reading the section on research papers for further guidance.

2. Comparison essays

Comparison essays often require you to follow the same general process outlined in the preceding sections. The primary difference, of course, is that they ask you to deal with more than one visual source. These assignments usually focus on how the formal elements of two artworks compare and contrast with each other. Resist the urge to turn the essay into a list of similarities and differences.

Comparison essays differ in another important way. Because they typically ask you to connect the visual materials in some way or to explain the significance of the comparison itself, they may require that you comment on the context in which the art was created or displayed.

For example, you might have been asked to write a comparative analysis of the painting discussed in the previous section, George Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty (ca. 1800), and an unknown Vicús artist’s Bottle in the Form of a Pig (ca. 200 BCE–600 CE). Both works are illustrated below.

You can begin this kind of essay with the same process of observations and note-taking outlined above for formal analysis essays. Consider using the same questions and categories to get yourself started.

Here are some questions you might ask:

- What techniques were used to create these objects?

- How does the use of color in these two works compare? Is it similar or different?

- What can you say about the composition of the sculpture? How does the artist treat certain formal elements, for example geometry? How do these elements compare to and contrast with those found in the painting?

- How do these works represent their subjects? Are they naturalistic or abstract? How do these artists create these effects? Why do these similarities and differences matter?

As our handout on comparing and contrasting suggests, you can organize these thoughts into a Venn diagram or a chart to help keep the answers to these questions distinct.

For example, some notes on these two artworks have been organized into a chart:

As you determine points of comparison, think about the themes that you have discussed in class. You might consider whether the artworks display similar topics or themes. If both artworks include the same subject matter, for example, how does that similarity contribute to the significance of the comparison? How do these artworks relate to the periods or cultures in which they were produced, and what do those relationships suggest about the comparison? The answers to these questions can typically be informed by your knowledge from class lectures. How have your instructors framed the introduction of individual works in class? What aspects of society or culture have they emphasized to explain why specific formal elements were included or excluded? Once you answer your questions, you might notice that some observations are more important than others.

Writing: developing an interpretation that considers both sources

When drafting your thesis, go beyond simply stating your topic. A statement that says “these representations of pig-like animals have some similarities and differences” doesn’t tell your reader what you will argue in your essay.

To say more, based on the notes in the chart above, you might write the following thesis statement:

Although both artworks depict pig-like animals, they rely on different methods of representing the natural world.

Now you have a place to start. Next, you can say more about your analysis. Ask yourself: “so what?” Why does it matter that these two artworks depict pig-like animals? You might want to return to your class notes at this point. Why did your instructor have you analyze these two works in particular? How does the comparison relate to what you have already discussed in class? Remember, comparison essays will typically ask you to think beyond formal analysis.

While the comparison of a similar subject matter (pig-like animals) may influence your initial argument, you may find that other points of comparison (e.g., the context in which the objects were displayed) allow you to more fully address the matter of significance. Thinking about the comparison in this way, you can write a more complex thesis that answers the “so what?” question. If your class has discussed how artists use animals to comment on their social context, for example, you might explore the symbolic importance of these pig-like animals in nineteenth-century British culture and in first-millenium Vicús culture. What political, social, or religious meanings could these objects have generated? If you find yourself needing to do outside research, look over the final section on research papers below!

Supporting paragraphs

The rest of your comparison essay should address the points raised in your thesis in an organized manner. While you could try several approaches, the two most common organizational tactics are discussing the material “subject-by-subject” and “point-by-point.”

- Subject-by-subject: Organizing the body of the paper in this way involves writing everything that you want to say about Moreland’s painting first (in a series of paragraphs) before moving on to everything about the ceramic bottle (in a series of paragraphs). Using our example, after the introduction, you could include a paragraph that discusses the positioning of the animals in Moreland’s painting, another paragraph that describes the depiction of the pigs’ surroundings, and a third explaining the role of geometry in forming the animals. You would then follow this discussion with paragraphs focused on the same topics, in the same order, for the ancient South American vessel. You could then follow this discussion with a paragraph that synthesizes all of the information and explores the significance of the comparison.

- Point-by-point: This strategy, in contrast, involves discussing a single point of comparison or contrast for both objects at the same time. For example, in a single paragraph, you could examine the use of color in both of our examples. Your next paragraph could move on to the differences in the figures’ setting or background (or lack thereof).

As our use of “pig-like” in this section indicates, titles can be misleading. Many titles are assigned by curators and collectors, in some cases years after the object was produced. While the ceramic vessel is titled Bottle in the Form of a Pig , the date and location suggest it may depict a peccary, a pig-like species indigenous to Peru. As you gather information about your objects, think critically about things like titles and dates. Who assigned the title of the work? If it was someone other than the artist, why might they have given it that title? Don’t always take information like titles and dates at face value.

Be cautious about considering contextual elements not immediately apparent from viewing the objects themselves unless you are explicitly asked to do so (try referring back to the prompt or assignment description; it will often describe the expectation of outside research). You may be able to note that the artworks were created during different periods, in different places, with different functions. Even so, avoid making broad assumptions based on those observations. While commenting on these topics may only require some inference or notes from class, if your argument demands a large amount of outside research, you may be writing a different kind of paper. If so, check out the next section!

3. Research papers

Some assignments in art history ask you to do outside research (i.e., beyond both formal analysis and lecture materials). These writing assignments may ask you to contextualize the visual materials that you are discussing, or they may ask you to explore your material through certain theoretical approaches. More specifically, you may be asked to look at the object’s relationship to ideas about identity, politics, culture, and artistic production during the period in which the work was made or displayed. All of these factors require you to synthesize scholars’ arguments about the materials that you are analyzing. In many cases, you may find little to no research on your specific object. When facing this situation, consider how you can apply scholars’ insights about related materials and the period broadly to your object to form an argument. While we cannot cover all the possibilities here, we’ll highlight a few factors that your instructor may task you with investigating.

Iconography

Papers that ask you to consider iconography may require research on the symbolic role or significance of particular symbols (gestures, objects, etc.). For example, you may need to do some research to understand how pig-like animals are typically represented by the cultural group that made this bottle, the Vicús culture. For the same paper, you would likely research other symbols, notably the bird that forms part of the bottle’s handle, to understand how they relate to one another. This process may involve figuring out how these elements are presented in other artworks and what they mean more broadly.

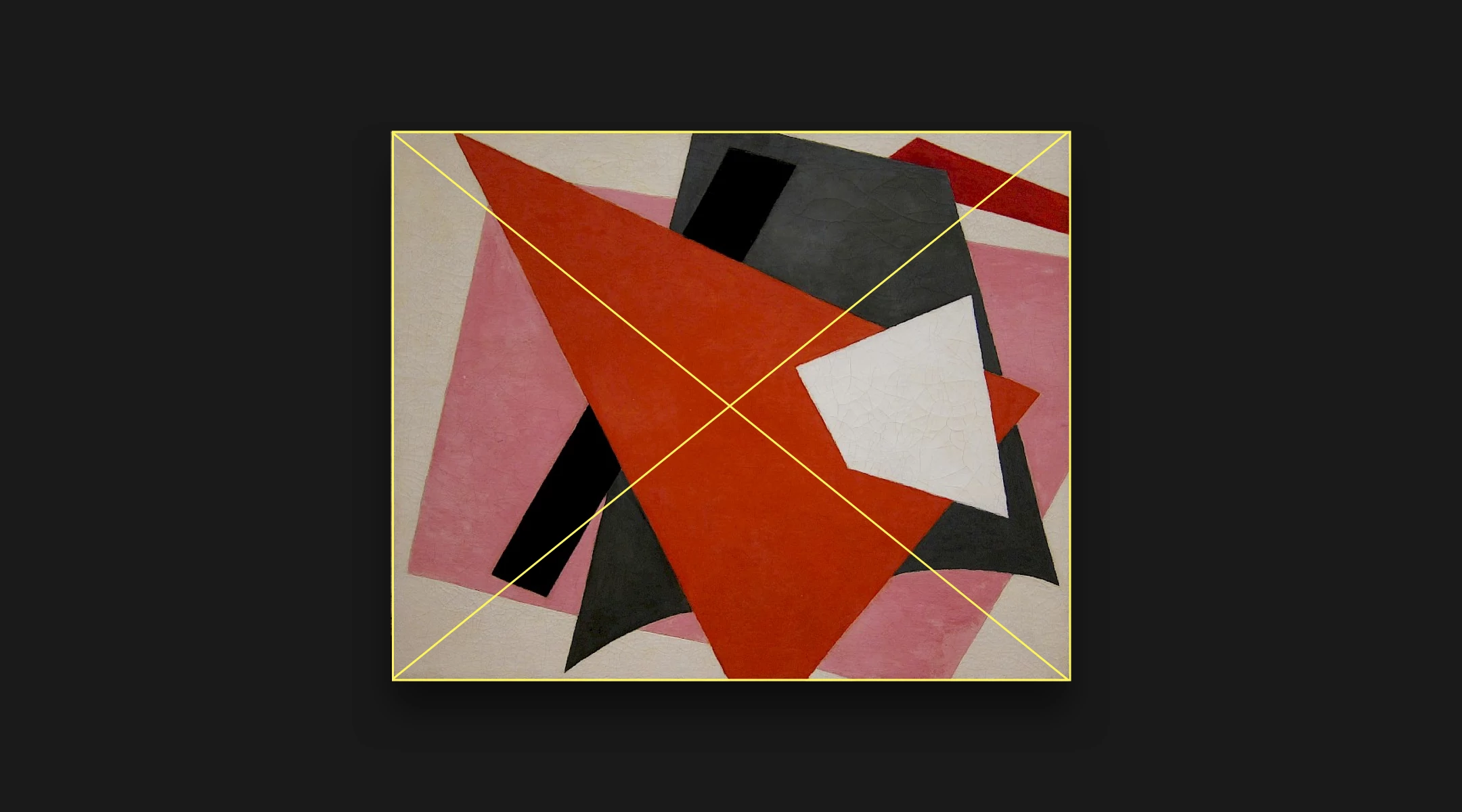

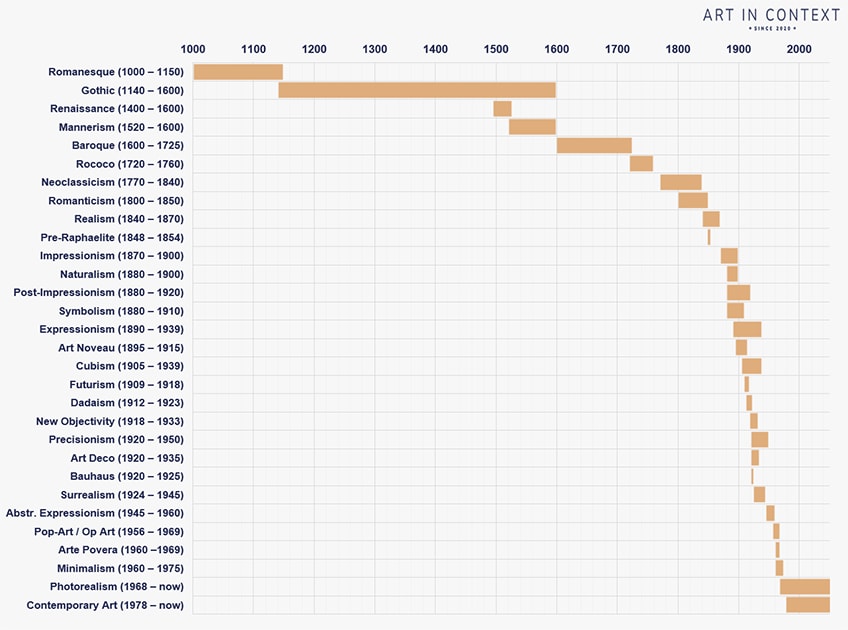

Artistic style and stylistic period

You may also be asked to compare your object or painting to a particular stylistic category. To determine the typical traits of a style, you may need to hit the library. For example, which period style or stylistic trend does Moreland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty belong to? How well does the piece “fit” that particular style? Especially for works that depict the same or similar topics, how might their different styles affect your interpretation? Assignments that ask you to consider style as a factor may require that you do some research on larger historical or cultural trends that influenced the development of a particular style.

Provenance research asks you to find out about the “life” of the object itself. This research can include the circumstances surrounding the work’s production and its later ownership. For the two works discussed in this handout, you might research where these objects were originally displayed and how they ended up in the museum collections in which they now reside. What kind of argument could you develop with this information? For example, you might begin by considering that many bottles and jars resembling the Bottle in the Form of a Pig can be found in various collections of Pre-Columbian art around the world. Where do these objects originate? Do they come from the same community or region?

Patronage study

Prompts that ask you to discuss patronage might ask you to think about how, when, where, and why the patron (the person who commissions or buys the artwork or who supports the artist) acquired the object from the artist. The assignment may ask you to comment on the artist-patron relationship, how the work fit into a broader series of commissions, and why patrons chose particular artists or even particular subjects.

Additional resources

To look up recent articles, ask your librarian about the Art Index, RILA, BHA, and Avery Index. Check out www.lib.unc.edu/art/index.html for further information!

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Adams, Laurie Schneider. 2003. Looking at Art . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Barnet, Sylvan. 2015. A Short Guide to Writing about Art , 11th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Tate Galleries. n.d. “Art Terms.” Accessed November 1, 2020. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

What is art history and where is it going?

Peter Paul Rubens, three paintings from the 24-picture cycle Rubens painted for the Medici Gallery in the Luxembourg Palace, Paris. From left to right: Peter Paul Rubens, The Presentation of the Portrait of Marie de’ Medici , The Wedding by Proxy of Marie de’ Medici to King Henry IV , Arrival (or Disembarkation) of Marie de’ Medici at Marseilles , 1621–25, oil on canvas (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Art history might seem like a relatively straightforward concept: “art” and “history” are subjects most of us first studied in elementary school. In practice, however, the idea of “the history of art” raises complex questions. What exactly do we mean by art, and what kind of history (or histories) should we explore? Let’s consider each term further.

Art versus artifact

The word “art” is derived from the Latin ars , which originally meant “skill” or “craft.” These meanings are still primary in other English words derived from ars , such as “artifact” (a thing made by human skill) and “artisan” (a person skilled at making things). The meanings of “art” and “artist,” however, are not so straightforward. We understand art as involving more than just skilled craftsmanship. What exactly distinguishes a work of art from an artifact, or an artist from an artisan?

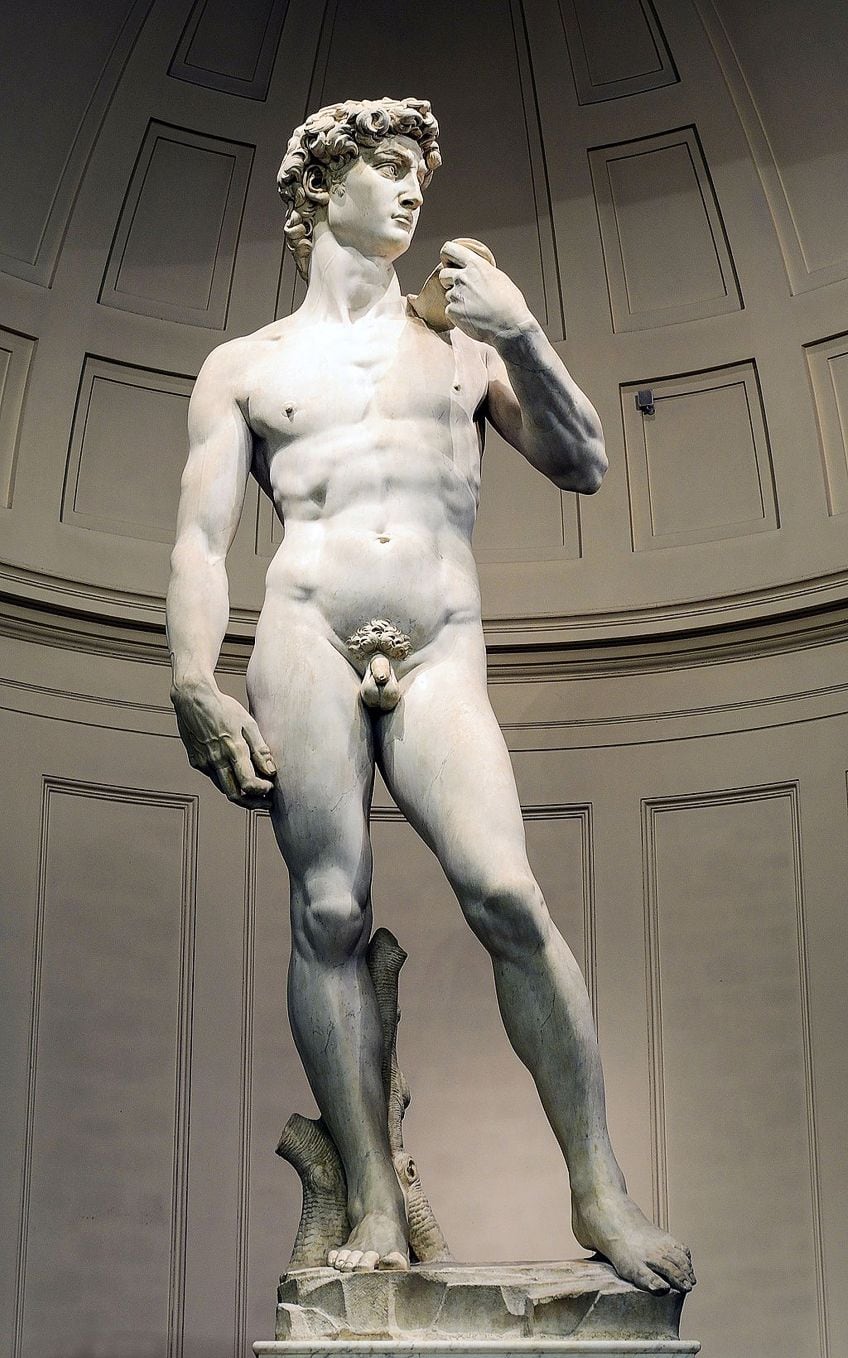

When asked this question, students typically come up with several ideas. One is beauty. Much art is visually striking, and in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, the analysis of aesthetic qualities was indeed central in art history. During this time, art that imitated ancient Greek and Roman art (the art of classical antiquity ), was considered to embody a timeless perfection. Art historians focused on the so-called fine arts—painting, sculpture, and architecture—analyzing the virtues of their forms. Over the past century and a half, however, both art and art history have evolved radically.

Left: Lysippos, Apoxyomenos (Scraper) , Roman copy after a bronze statue from c. 330 B.C.E., 81 inches high (Vatican Museums, photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Kiki Smith, male figure from Untitled , 1990, 198.1 x 181.6 x 54 cm, beeswax and microcrystalline wax figures on metal stands (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York) © Kiki Smith

Artists turned away from the classical tradition , embracing new media and aesthetic ideals, and art historians shifted their focus from the analysis of art’s formal beauty to interpretation of its cultural meaning. Today we understand beauty as subjective—a cultural construct that varies across time and space. While most art continues to be primarily visual, and visual analysis is still a fundamental tool used by art historians, beauty itself is no longer considered an essential attribute of art.

Images of Peter and Paul appear much the same through the centuries in Byzantine icons. Left: glass bowl base, 4th century, Roman ( The Metropolitan Museum of Art ); center: mosaics, 11th century, Hosios Loukas Monastery, Greece; right: panel icon, 17th century, Greek ( Temple Gallery ).

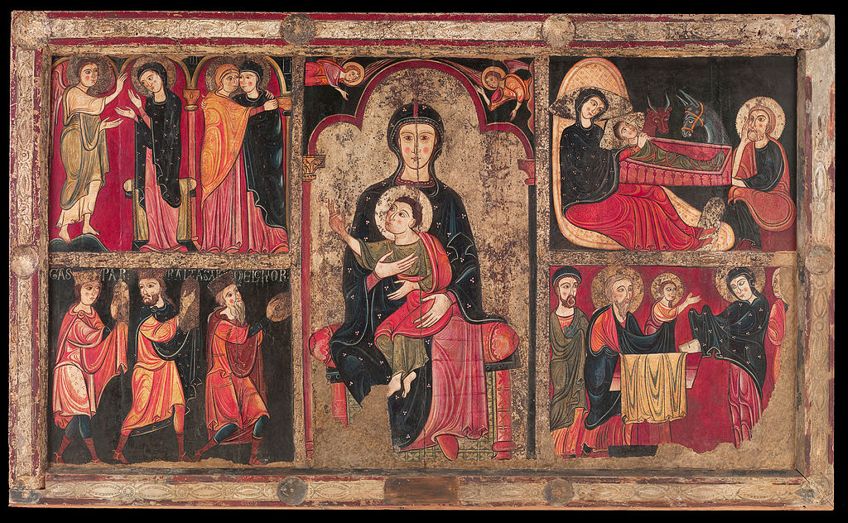

A second common answer to the question of what distinguishes art emphasizes originality, creativity, and imagination. This reflects a modern understanding of art as a manifestation of the ingenuity of the artist. This idea, however, originated five hundred years ago in Renaissance Europe , and is not directly applicable to many of the works studied by art historians. For example, in the case of ancient Egyptian art or Byzantine icons , the preservation of tradition was more valued than innovation. While the idea of ingenuity is certainly important in the history of art, it is not a universal attribute of the works studied by art historians.

All this might lead one to conclude that definitions of art, like those of beauty, are subjective and unstable. One solution to this dilemma is to propose that art is distinguished primarily by its visual agency, that is, by its ability to captivate viewers. Artifacts may be interesting, but art, I suggest, has the potential to move us—emotionally, intellectually, or otherwise. It may do this through its visual characteristics (scale, composition, color, etc.), expression of ideas, craftsmanship, ingenuity, rarity, or some combination of these or other qualities. How art engages varies, but in some manner, art takes us beyond the everyday and ordinary experience. The greatest examples attest to the extremes of human ambition, skill, imagination, perception, and feeling. As such, art prompts us to reflect on fundamental aspects of what it is to be human. Any artifact, as a product of human skill, might provide insight into the human condition. But art, in moving beyond the commonplace, has the potential to do so in more profound ways. Art, then, is perhaps best understood as a special class of artifact, exceptional in its ability to make us think and feel through visual experience.

Coatlicue , c. 1500, Mexica (Aztec), found on the SE edge of the Plaza Mayor/Zocalo in Mexico City, basalt, 257 cm high (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

History: Making Sense of the Past

Like definitions of art and beauty, ideas about history have changed over time. It might seem that writing history should be straightforward—it’s all based on facts, isn’t it? In theory, yes, but the evidence surviving from the past is vast, fragmentary, and messy. Historians must make decisions about what to include and exclude, how to organize the material, and what to say about it. In doing so, they create narratives that explain the past in ways that make sense in the present. Inevitably, as the present changes, these narratives are updated, rewritten, or discarded altogether and replaced with new ones. All history, then, is subjective—as much a product of the time and place it was written as of the evidence from the past that it interprets.

The discipline of art history developed in Europe during the colonial period (roughly the 15th to the mid-20th century). Early art historians emphasized the European tradition, celebrating its Greek and Roman origins and the ideals of academic art . By the mid-20th century, a standard narrative for “Western art” was established that traced its development from the prehistoric , ancient , and medieval Mediterranean to modern Europe and the United States . Art from the rest of the world, labeled “non-Western art,” was typically treated only marginally and from a colonialist perspective.

The immense sociocultural changes that took place in the 20th century led art historians to amend these narratives. Accounts of Western art that once featured only white males were revised to include artists of color and women. The traditional focus on painting, sculpture, and architecture was expanded to include so-called minor arts such as ceramics and textiles and contemporary media such as video and performance art . Interest in non-Western art increased, accelerating dramatically in recent years.

Queen Mother Pendant Mask (Iyoba), 16th century, Edo peoples, Court of Benin, Nigeria, ivory, iron, copper, 23.8 x 12.7 x 8.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Today, the biggest social development facing art history is globalism. As our world becomes increasingly interconnected, familiarity with different cultures and facility with diversity are essential. Art history, as the story of exceptional artifacts from a broad range of cultures, has a role to play in developing these skills. Now art historians ponder and debate how to reconcile the discipline’s European intellectual origins and its problematic colonialist legacy with contemporary multiculturalism and how to write art history in a global era.

Smarthistory’s videos and articles reflect this history of art history. Since the site was originally created to support a course in Western art and history, the content initially focused on the most celebrated works of the Western canon . With the key periods and civilizations of this tradition now well-represented and a growing number of scholars contributing, the range of objects and topics has increased in recent years. Most importantly, substantial coverage of world traditions outside the West has been added. As the site continues to expand, the works and perspectives presented will evolve in step with contemporary trends in art history. In fact, as innovators in the use of digital media and the internet to create, disseminate, and interrogate art historical knowledge, Smarthistory and its users have the potential to help shape the future of the discipline.

Important fundamentals

“ Introduction: Learning to look and think critically ,” a chapter in Reframing Art History (our free art history textbook).

“ Introduction: Close looking and approaches to art ,” a chapter in Reframing Art History (our free art history textbook)—especially useful for materials related to formal (visual) analysis.

Check out all the chapters on world art in Reframing Art History .

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

What is art history and where is it going?

Peter Paul Rubens, three paintings from the 24-picture cycle Rubens painted for the Medici Gallery in the Luxembourg Palace, Paris. From left to right: Peter Paul Rubens, The Presentation of the Portrait of Marie de’ Medici , The Wedding by Proxy of Marie de’ Medici to King Henry IV , Arrival (or Disembarkation) of Marie de’ Medici at Marseilles , 1621–25, oil on canvas (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Art history might seem like a relatively straightforward concept: “art” and “history” are subjects most of us first studied in elementary school. In practice, however, the idea of “the history of art” raises complex questions. What exactly do we mean by art, and what kind of history (or histories) should we explore? Let’s consider each term further.

Art versus artifact

The word “art” is derived from the Latin ars , which originally meant “skill” or “craft.” These meanings are still primary in other English words derived from ars , such as “artifact” (a thing made by human skill) and “artisan” (a person skilled at making things). The meanings of “art” and “artist,” however, are not so straightforward. We understand art as involving more than just skilled craftsmanship. What exactly distinguishes a work of art from an artifact, or an artist from an artisan?

When asked this question, students typically come up with several ideas. One is beauty. Much art is visually striking, and in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, the analysis of aesthetic qualities was indeed central in art history. During this time, art that imitated ancient Greek and Roman art (the art of classical antiquity ), was considered to embody a timeless perfection. Art historians focused on the so-called fine arts—painting, sculpture, and architecture—analyzing the virtues of their forms. Over the past century and a half, however, both art and art history have evolved radically.

Left: Lysippos, Apoxyomenos (Scraper) , Roman copy after a bronze statue from c. 330 B.C.E., 81 inches high (Vatican Museums, photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Kiki Smith, male figure from Untitled , 1990, 198.1 x 181.6 x 54 cm, beeswax and microcrystalline wax figures on metal stands (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York) © Kiki Smith

Artists turned away from the classical tradition, embracing new media and aesthetic ideals, and art historians shifted their focus from the analysis of art’s formal beauty to interpretation of its cultural meaning. Today we understand beauty as subjective—a cultural construct that varies across time and space. While most art continues to be primarily visual, and visual analysis is still a fundamental tool used by art historians, beauty itself is no longer considered an essential attribute of art.

Images of Peter and Paul appear much the same through the centuries in Byzantine icons. Left: glass bowl base, 4th century, Roman ( The Metropolitan Museum of Art ); center: mosaics, 11th century, Hosios Loukas Monastery, Greece; right: panel icon, 17th century, Greek ( Temple Gallery ).

A second common answer to the question of what distinguishes art emphasizes originality, creativity, and imagination. This reflects a modern understanding of art as a manifestation of the ingenuity of the artist. This idea, however, originated five hundred years ago in Renaissance Europe , and is not directly applicable to many of the works studied by art historians. For example, in the case of ancient Egyptian art or Byzantine icons , the preservation of tradition was more valued than innovation. While the idea of ingenuity is certainly important in the history of art, it is not a universal attribute of the works studied by art historians.

All this might lead one to conclude that definitions of art, like those of beauty, are subjective and unstable. One solution to this dilemma is to propose that art is distinguished primarily by its visual agency, that is, by its ability to captivate viewers. Artifacts may be interesting, but art, I suggest, has the potential to move us—emotionally, intellectually, or otherwise. It may do this through its visual characteristics (scale, composition, color, etc.), expression of ideas, craftsmanship, ingenuity, rarity, or some combination of these or other qualities. How art engages varies, but in some manner, art takes us beyond the everyday and ordinary experience. The greatest examples attest to the extremes of human ambition, skill, imagination, perception, and feeling. As such, art prompts us to reflect on fundamental aspects of what it is to be human. Any artifact, as a product of human skill, might provide insight into the human condition. But art, in moving beyond the commonplace, has the potential to do so in more profound ways. Art, then, is perhaps best understood as a special class of artifact, exceptional in its ability to make us think and feel through visual experience.

Coatlicue , c. 1500, Mexica (Aztec), found on the SE edge of the Plaza Mayor/Zocalo in Mexico City, basalt, 257 cm high (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

History: Making Sense of the Past

Like definitions of art and beauty, ideas about history have changed over time. It might seem that writing history should be straightforward—it’s all based on facts, isn’t it? In theory, yes, but the evidence surviving from the past is vast, fragmentary, and messy. Historians must make decisions about what to include and exclude, how to organize the material, and what to say about it. In doing so, they create narratives that explain the past in ways that make sense in the present. Inevitably, as the present changes, these narratives are updated, rewritten, or discarded altogether and replaced with new ones. All history, then, is subjective—as much a product of the time and place it was written as of the evidence from the past that it interprets.

The discipline of art history developed in Europe during the colonial period (roughly the 15th to the mid-20th century). Early art historians emphasized the European tradition, celebrating its Greek and Roman origins and the ideals of academic art . By the mid-20th century, a standard narrative for “Western art” was established that traced its development from the prehistoric , ancient , and medieval Mediterranean to modern Europe and the United States . Art from the rest of the world, labeled “non-Western art,” was typically treated only marginally and from a colonialist perspective.

The immense sociocultural changes that took place in the 20th century led art historians to amend these narratives. Accounts of Western art that once featured only white males were revised to include artists of color and women. The traditional focus on painting, sculpture, and architecture was expanded to include so-called minor arts such as ceramics and textiles and contemporary media such as video and performance art . Interest in non-Western art increased, accelerating dramatically in recent years.

Queen Mother Pendant Mask (Iyoba), 16th century, Edo peoples, Court of Benin, Nigeria, ivory, iron, copper, 23.8 x 12.7 x 8.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Today, the biggest social development facing art history is globalism. As our world becomes increasingly interconnected, familiarity with different cultures and facility with diversity are essential. Art history, as the story of exceptional artifacts from a broad range of cultures, has a role to play in developing these skills. Now art historians ponder and debate how to reconcile the discipline’s European intellectual origins and its problematic colonialist legacy with contemporary multiculturalism and how to write art history in a global era.

Smarthistory’s videos and articles reflect this history of art history. Since the site was originally created to support a course in Western art and history, the content initially focused on the most celebrated works of the Western canon. With the key periods and civilizations of this tradition now well-represented and a growing number of scholars contributing, the range of objects and topics has increased in recent years. Most importantly, substantial coverage of world traditions outside the West has been added. As the site continues to expand, the works and perspectives presented will evolve in step with contemporary trends in art history. In fact, as innovators in the use of digital media and the internet to create, disseminate, and interrogate art historical knowledge, Smarthistory and its users have the potential to help shape the future of the discipline.

Additional resources

“ Introduction: Learning to look and think critically ,” a chapter in Reframing Art History (our free art history textbook).

“ Introduction: Close looking and approaches to art ,” a chapter in Reframing Art History (our free art history textbook)—especially useful for materials related to formal (visual) analysis.

Check out all the chapters on world art in Reframing Art History .

History of Art: Prehistoric to Gothic Copyright © by Dr. Amy Marshman; Dr. Jeanette Nicewinter; and Dr. Paula Winn is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The Courtauld is an internationally renowned centre for the teaching and research of art history and a major public gallery

Be part of an international community of influential art enthusiasts, thought leaders and change makers

Current students

Information and resources for students currently studying at The Courtauld

Stay in touch

Quick links, suggested searches, what is art history.

Art history – the study of art from across the world, and from the ancient to the present day – covers virtually every aspect of human history and experience. This is because it looks at works of art not just as objects, but as a way of understanding the world, and the societies in which they were created.

What were the conscious and unconscious choices that led to an artwork’s form and subject matter? What does its content – how people are represented, how religion is shown – tell you about the society in which it was created, and its history? How was it received when it was first put on display, and how has this changed?

By asking these questions, art historians gain a fascinating insight into how people throughout time and across the world lived, thought, felt and understood everything around them. Developing understanding of these challenges helps us make sense of the relationship between people, art and the forces that shape the world we live in today – and provides us with the critical skills to understand the visual world around us.

Why study Art History?

It combines the rigour of a history degree with the visual skills required to interpret works of art. It will help you develop critical skills, to think about art and history from a variety of perspectives, and to present your ideas succinctly and persuasively. These are all key skills that will help you to stand out in today’s job market. You will learn to analyse the role art plays in shaping society. Art History will introduce you to world-famous works of art, as well as others that are less well known but equally as fascinating to examine and study. You will get to explore new areas of Art History, and artworks from a variety of time periods, from all around the world, delivered in a range of different forms. If you enjoy reading history, studying literature or languages, looking at art, and are fascinated by the relationship between people, art, and the forces that have shaped the world we live in, then Art History is the subject for you.

"What is art history" - we asked our academics:

Dr Guido Rebecchini, Reader in Sixteenth-Century Southern European Art:

Artworks from the past communicate with us across centuries in a language that is much more mysterious and nuanced than one might first assume. Interrogating them and looking closely at what they represent, as well as at their materials and techniques, enables us to make contact with ideas, rituals, beliefs and practices wholly different from our own. Art historians therefore explore the gulf between the appearance of artworks – as we might see them today in museums, galleries and historical buildings – and the complex ideas behind their production.

It is important to remember that artworks produced in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period, in both the East and the West, were not intended to be displayed in museums. Instead, such artworks communicated with their audiences in spaces where rituals and practices that helped to form familial, civic and religious identities, such as palaces, churches and squares. Works of art were often made to mark marriages, births, deaths, and they reflected hopes and ambitions; in fact, they were often thought to have real agency in the world. Artworks were considered to possess holy powers, brought in procession, or stood in for absent people.

Ultimately, as art historians, we look closely and carefully, patiently and inquisitively, and ask questions incessantly. To do so, we analyse, compare and connect a wide range of difference sources and pieces of evidence; primarily the artworks themselves, but also documents, literature and many other traces of the past. By doing so, we locate works of art in the ecosystem in which they were conceived, which helps us to better understand how artworks of the past have shaped the world we live in. For these reasons, art history is a truly interdisciplinary: it demands that we take the vantage point of others, like the anthropologist does; that we see things in historical perspective, as the historian does; and that we consider how ideas related religion, family, gender, race, and politics are implicated in the art of the past. In conclusion, art history is an inquiry into human culture pursued mainly – but not only – by critically looking at the extraordinary images that past generations have left behind.

You might also like

Why does art history matter?

- Art Degrees

- Galleries & Exhibits

- Request More Info

Art History Resources

- Guidelines for Analysis of Art

- Formal Analysis Paper Examples

Guidelines for Writing Art History Research Papers

- Oral Report Guidelines

- Annual Arkansas College Art History Symposium

Writing a paper for an art history course is similar to the analytical, research-based papers that you may have written in English literature courses or history courses. Although art historical research and writing does include the analysis of written documents, there are distinctive differences between art history writing and other disciplines because the primary documents are works of art. A key reference guide for researching and analyzing works of art and for writing art history papers is the 10th edition (or later) of Sylvan Barnet’s work, A Short Guide to Writing about Art . Barnet directs students through the steps of thinking about a research topic, collecting information, and then writing and documenting a paper.

A website with helpful tips for writing art history papers is posted by the University of North Carolina.

Wesleyan University Writing Center has a useful guide for finding online writing resources.

The following are basic guidelines that you must use when documenting research papers for any art history class at UA Little Rock. Solid, thoughtful research and correct documentation of the sources used in this research (i.e., footnotes/endnotes, bibliography, and illustrations**) are essential. Additionally, these guidelines remind students about plagiarism, a serious academic offense.

Paper Format

Research papers should be in a 12-point font, double-spaced. Ample margins should be left for the instructor’s comments. All margins should be one inch to allow for comments. Number all pages. The cover sheet for the paper should include the following information: title of paper, your name, course title and number, course instructor, and date paper is submitted. A simple presentation of a paper is sufficient. Staple the pages together at the upper left or put them in a simple three-ring folder or binder. Do not put individual pages in plastic sleeves.

Documentation of Resources

The Chicago Manual of Style (CMS), as described in the most recent edition of Sylvan Barnet’s A Short Guide to Writing about Art is the department standard. Although you may have used MLA style for English papers or other disciplines, the Chicago Style is required for all students taking art history courses at UA Little Rock. There are significant differences between MLA style and Chicago Style. A “Quick Guide” for the Chicago Manual of Style footnote and bibliography format is found http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html. The footnote examples are numbered and the bibliography example is last. Please note that the place of publication and the publisher are enclosed in parentheses in the footnote, but they are not in parentheses in the bibliography. Examples of CMS for some types of note and bibliography references are given below in this Guideline. Arabic numbers are used for footnotes. Some word processing programs may have Roman numerals as a choice, but the standard is Arabic numbers. The use of super script numbers, as given in examples below, is the standard in UA Little Rock art history papers.

The chapter “Manuscript Form” in the Barnet book (10th edition or later) provides models for the correct forms for footnotes/endnotes and the bibliography. For example, the note form for the FIRST REFERENCE to a book with a single author is:

1 Bruce Cole, Italian Art 1250-1550 (New York: New York University Press, 1971), 134.

But the BIBLIOGRAPHIC FORM for that same book is:

Cole, Bruce. Italian Art 1250-1550. New York: New York University Press. 1971.

The FIRST REFERENCE to a journal article (in a periodical that is paginated by volume) with a single author in a footnote is:

2 Anne H. Van Buren, “Madame Cézanne’s Fashions and the Dates of Her Portraits,” Art Quarterly 29 (1966): 199.

The FIRST REFERENCE to a journal article (in a periodical that is paginated by volume) with a single author in the BIBLIOGRAPHY is:

Van Buren, Anne H. “Madame Cézanne’s Fashions and the Dates of Her Portraits.” Art Quarterly 29 (1966): 185-204.

If you reference an article that you found through an electronic database such as JSTOR, you do not include the url for JSTOR or the date accessed in either the footnote or the bibliography. This is because the article is one that was originally printed in a hard-copy journal; what you located through JSTOR is simply a copy of printed pages. Your citation follows the same format for an article in a bound volume that you may have pulled from the library shelves. If, however, you use an article that originally was in an electronic format and is available only on-line, then follow the “non-print” forms listed below.

B. Non-Print

Citations for Internet sources such as online journals or scholarly web sites should follow the form described in Barnet’s chapter, “Writing a Research Paper.” For example, the footnote or endnote reference given by Barnet for a web site is:

3 Nigel Strudwick, Egyptology Resources , with the assistance of The Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Cambridge University, 1994, revised 16 June 2008, http://www.newton.ac.uk/egypt/ , 24 July 2008.

If you use microform or microfilm resources, consult the most recent edition of Kate Turabian, A Manual of Term Paper, Theses and Dissertations. A copy of Turabian is available at the reference desk in the main library.

C. Visual Documentation (Illustrations)

Art history papers require visual documentation such as photographs, photocopies, or scanned images of the art works you discuss. In the chapter “Manuscript Form” in A Short Guide to Writing about Art, Barnet explains how to identify illustrations or “figures” in the text of your paper and how to caption the visual material. Each photograph, photocopy, or scanned image should appear on a single sheet of paper unless two images and their captions will fit on a single sheet of paper with one inch margins on all sides. Note also that the title of a work of art is always italicized. Within the text, the reference to the illustration is enclosed in parentheses and placed at the end of the sentence. A period for the sentence comes after the parenthetical reference to the illustration. For UA Little Rcok art history papers, illustrations are placed at the end of the paper, not within the text. Illustration are not supplied as a Powerpoint presentation or as separate .jpgs submitted in an electronic format.

Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream, dated 1893, represents a highly personal, expressive response to an experience the artist had while walking one evening (Figure 1).

The caption that accompanies the illustration at the end of the paper would read:

Figure 1. Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893. Tempera and casein on cardboard, 36 x 29″ (91.3 x 73.7 cm). Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo, Norway.

Plagiarism is a form of thievery and is illegal. According to Webster’s New World Dictionary, to plagiarize is to “take and pass off as one’s own the ideas, writings, etc. of another.” Barnet has some useful guidelines for acknowledging sources in his chapter “Manuscript Form;” review them so that you will not be mguilty of theft. Another useful website regarding plagiarism is provided by Cornell University, http://plagiarism.arts.cornell.edu/tutorial/index.cfm

Plagiarism is a serious offense, and students should understand that checking papers for plagiarized content is easy to do with Internet resources. Plagiarism will be reported as academic dishonesty to the Dean of Students; see Section VI of the Student Handbook which cites plagiarism as a specific violation. Take care that you fully and accurately acknowledge the source of another author, whether you are quoting the material verbatim or paraphrasing. Borrowing the idea of another author by merely changing some or even all of your source’s words does not allow you to claim the ideas as your own. You must credit both direct quotes and your paraphrases. Again, Barnet’s chapter “Manuscript Form” sets out clear guidelines for avoiding plagiarism.

VISIT OUR GALLERIES SEE UPCOMING EXHIBITS

- School of Art and Design

- Windgate Center of Art + Design, Room 202 2801 S University Avenue Little Rock , AR 72204

- Phone: 501-916-3182 Fax: 501-683-7022 (fax)

- More contact information

Connect With Us

UA Little Rock is an accredited member of the National Association of Schools of Art and Design.

The Writing Place

Resources – how to write an art history paper, introduction to the topic.

There are many different types of assignments you might be asked to do in an art history class. The most common are a formal analysis and a stylistic analysis. Stylistic analyses often involve offering a comparison between two different works. One of the challenges of art history writing is that it requires a vocabulary to describe what you see when you look at a painting, drawing, sculpture or other media. This checklist is designed to explore questions that will help you write these types of art history papers.

Features of An Art History Analysis Paper

Features of a formal analysis paper.

This type of paper involves looking at compositional elements of an object such as color, line, medium, scale, and texture. The goal of this kind of assignment it to demonstrate how these elements work together to produce the whole art object. When writing a formal analysis, ask yourself:

- What is the first element of the work that the audience’s eye captures?

- What materials were used to create the object?

- What colors and textures did the artist employ?

- How do these function together to give the object its overall aesthetic look?

Tips on Formal Analysis

- Describe the piece as if your audience has not seen it.

- Be detailed.

- The primary focus should be on description rather than interpretation.

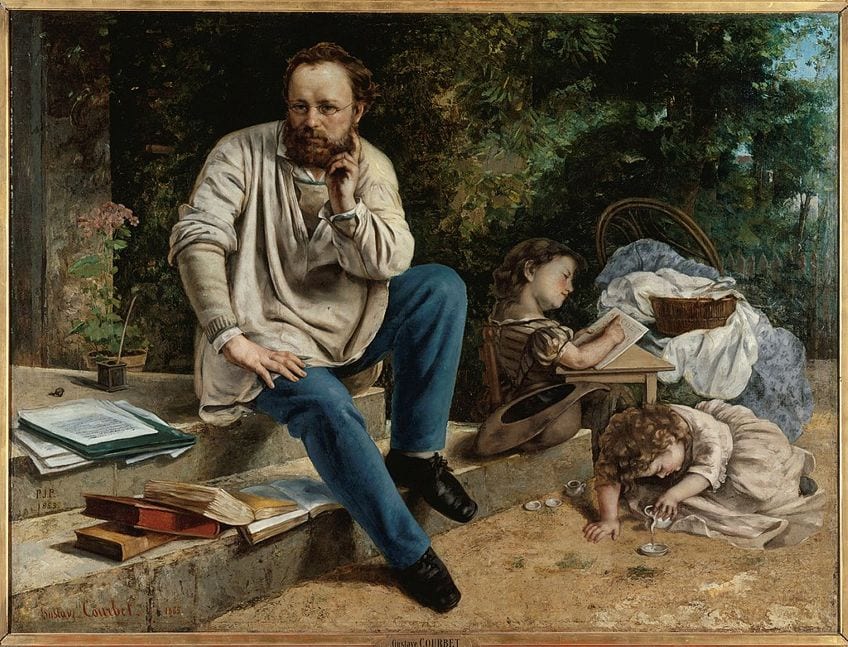

Features of a Stylistic / Comparative Analysis

Similar to a formal analysis, a stylistic analysis asks you to discuss a work in relation to its stylistic period (Impressionism, Fauvism, High Renaissance, etc.). These papers often involve a comparative element (such as comparing a statue from Early Antiquity to Late Antiquity). When writing a stylistic analysis, ask yourself:

- How does this work fit the style of its historical period? How does it depart from the typical style?

- What is the social and historical context of the work? When was it completed?

- Who was the artist? Who commissioned it? What does it depict?

- How is this work different from other works of the same subject matter?

- How have the conventions (formal elements) for this type of work changed over time?

Tips for Stylistic and Comparative Analysis

- In a comparison, make a list of similarities and differences between the two works. Try to establish what changes in the art world may account for the differences.

- Integrate discussions of formal elements into your stylistic analysis.

- This type of paper can involve more interpretation than a basic formal analysis.

- Focus on context and larger trends in art history.

A Quick Practice Exercise...

Practice - what is wrong with these sentences.

The key to writing a good art history paper involves relating the formal elements of a piece to its historical context. Can you spot the errors in these sentences? What would make the sentences better?

- “Courbet’s The Stone Breakers is a good painting because he uses texture.”

- “Duchamp’s work is in the Dada style while Dali’s is Surrealist.”

- “Pope Julius II commissioned the work.”

- “Gauguin uses color to draw in the viewer’s eye.”

Answers for Practice Sentences

- Better: “Courbet’s The Stone Breakers is a radical painting because the artist used a palette knife to create a rough texture on the surface.”

- Better: “The use of everyday objects in Duchamp’s work reflects the Dada style while Dali’s incorporation of absurd images into his work demonstrates a Surrealist style.”

- Better: “In 1505, Pope Julius II commissioned the sculpture for his tomb.”

- Better: “The first element a viewer notices is the bold blue of the sky in Gauguin’s painting.”

Adapted by Ann Bruton, with the help of Isaac Alpert, From:

The Writing Center at UNC Handouts ( http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/art-history/ )

The Writing Center at Hamilton College ( http://www.hamilton.edu/writing/writing-resources/writing-an-art-history-paper )

Click here to return to the “Writing Place Resources” main page.

Additional Navigation and Search

- Search Icon

Accessibility Options

Art history writing guide.

I. Introduction II. Writing Assignments III. Discipline-Specific Strategies IV. Keep in Mind V. Appendix

Introduction

At the heart of every art history paper is a close visual analysis of at least one work of art. In art history you are building an argument about something visual. Depending on the assignment, this analysis may be the basis for an assignment or incorporated into a paper as support to contextualize an argument. To guide students in how to write an art history paper, the Art History Department suggests that you begin with a visual observation that leads to the development of an interpretive thesis/argument. The writing uses visual observations as evidence to support an argument about the art that is being analyzed.

Writing Assignments

You will be expected to write several different kinds of art history papers. They include:

- Close Visual Analysis Essays

- Close Visual Analysis in dialogue with scholarly essays

- Research Papers

Close Visual Analysis pieces are the most commonly written papers in an introductory art history course. You will have to look at a work of art and analyze it in its entirety. The analysis and discussion should provide a clearly articulated interpretation of the object. Your argument for this paper should be backed up with careful description and analysis of the visual evidence that led you to your conclusion.

Close Visual Analysis in dialogue with scholarly essays combines formal analysis with close textual analysis.

Research papers range from theoretic studies to critical histories. Based on library research, students are asked to synthesize analyses of the scholarship in relation to the work upon which it is based.

Discipline-Specific Strategies

As with all writing assignment, a close visual analysis is a process. The work you do before you actually start writing can be just as important as what you consider when writing up your analysis.

Conducting the analysis :

- Ask questions as you are studying the artwork. Consider, for example, how does each element of the artwork contribute to the work's overall meaning. How do you know? How do elements relate to each other? What effect is produced by their juxtaposition

- Use the criteria provided by your professor to complete your analysis. This criteria may include forms, space, composition, line, color, light, texture, physical characteristics, and expressive content.

Writing the analysis:

- Develop a strong interpretive thesis about what you think is the overall effect or meaning of the image.

- Ground your argument in direct and specific references to the work of art itself.

- Describe the image in specific terms and with the criteria that you used for the analysis. For example, a stray diagonal from the upper left corner leads the eye to...

- Create an introduction that sets the stage for your paper by briefly describing the image you are analyzing and by stating your thesis.

- Explain how the elements work together to create an overall effect. Try not to just list the elements, but rather explain how they lead to or support your analysis.

- Contextualize the image within a historical and cultural framework only when required for an assignment. Some assignments actually prefer that you do not do this. Remember not to rely on secondary sources for formal analysis. The goal is to see what in the image led to your analysis; therefore, you will not need secondary sources in this analysis. Be certain to show how each detail supports your argument.

- Include only the elements needed to explain and support your analysis. You do not need to include everything you saw since this excess information may detract from your main argument.

Keep in Mind

- An art history paper has an argument that needs to be supported with elements from the image being analyzed.

- Avoid making grand claims. For example, saying "The artist wanted..." is different from "The warm palette evokes..." The first phrasing necessitates proof of the artist's intent, as opposed to the effect of the image.

- Make sure that your paper isn't just description. You should choose details that illustrate your central ideas and further the purpose of your paper.

If you find you are still having trouble writing your art history paper, please speak to your professor, and feel free to make an appointment at the Writing Center. For further reading, see Sylvan Barnet's A Short Guide to Writing about Art , 5th edition.

Additional Site Navigation

Social media links, additional navigation links.

- Alumni Resources & Events

- Athletics & Wellness

- Campus Calendar

- Parent & Family Resources

Helpful Information

Dining hall hours, next trains to philadelphia, next trico shuttles.

Swarthmore Traditions

How to Plan Your Classes

The Swarthmore Bucket List

Search the website

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Discover the story of art and global culture through The Met collection. Funded by the Heilbrunn Foundation, New Tamarind Foundation, and Zodiac Fund.

Explore more than 1,000 essays on a wide range of topics, including artists, materials, movements, and themes.

Andean Textiles

For centuries prior to the Spanish Conquest, Andean textiles were used to express status and identity.

Allegories of the Four Continents

European artists from the Renaissance onward have visualized the known world through allegorical figures.

Works of Art

Browse a selection of more than 8,000 works from the collection.

Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise

Giovanni di Paolo

Untitled Film Still #21

Cindy Sherman

Chronologies

Trace the global evolution of art and culture across millennia.

Ancient Greece, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

China, 500–1000 A.D.

Eastern Africa, 1600–1800 A.D.

Discover connections across time and cultures through more than 150 essays and 800 works of art in this book inspired by the Timeline .

The Value of Art Why should we care about art?

One of the first questions raised when talking about art is simple—why should we care? Art in the contemporary era is easy to dismiss as a selfish pastime for people who have too much time on their hands. Creating art doesn't cure disease, build roads, or feed the poor. So to understand the value of art, let’s look at how art has been valued through history and consider how it is valuable today.

The value of creating

At its most basic level, the act of creating is rewarding in itself. Children draw for the joy of it before they can speak, and creating pictures, sculptures and writing is both a valuable means of communicating ideas and simply fun. Creating is instinctive in humans, for the pleasure of exercising creativity. While applied creativity is valueable in a work context, free-form creativity leads to new ideas.

Material value

Through the ages, art has often been created from valuable materials. Gold , ivory and gemstones adorn medieval crowns , and even the paints used by renaissance artists were made from rare materials like lapis lazuli , ground into pigment. These objects have creative value for their beauty and craftsmanship, but they are also intrinsically valuable because of the materials they contain.

Historical value

Artwork is a record of cultural history. Many ancient cultures are entirely lost to time except for the artworks they created, a legacy that helps us understand our human past. Even recent work can help us understand the lives and times of its creators, like the artwork of African-American artists during the Harlem Renaissance . Artwork is inextricably tied to the time and cultural context it was created in, a relationship called zeitgeist , making art a window into history.

Religious value

For religions around the world, artwork is often used to illustrate their beliefs. Depicting gods and goddesses, from Shiva to the Madonna , make the concepts of faith real to the faithful. Artwork has been believed to contain the spirits of gods or ancestors, or may be used to imbue architecture with an aura of awe and worship like the Badshahi Mosque .

Patriotic value

Art has long been a source of national pride, both as an example of the skill and dedication of a country’s artisans and as expressions of national accomplishments and history, like the Arc de Triomphe , a heroic monument honoring the soldiers who died in the Napoleonic Wars. The patriotic value of art slides into propaganda as well, used to sway the populace towards a political agenda.

Symbolic value

Art is uniquely suited to communicating ideas. Whether it’s writing or painting or sculpture, artwork can distill complex concepts into symbols that can be understood, even sometimes across language barriers and cultures. When art achieves symbolic value it can become a rallying point for a movement, like J. Howard Miller’s 1942 illustration of Rosie the Riveter, which has become an icon of feminism and women’s economic impact across the western world.

Societal value

And here’s where the rubber meets the road: when we look at our world today, we see a seemingly insurmountable wave of fear, bigotry, and hatred expressed by groups of people against anyone who is different from them. While issues of racial and gender bias, homophobia and religious intolerance run deep, and have many complex sources, much of the problem lies with a lack of empathy. When you look at another person and don't see them as human, that’s the beginning of fear, violence and war. Art is communication. And in the contemporary world, it’s often a deeply personal communication. When you create art, you share your worldview, your history, your culture and yourself with the world. Art is a window, however small, into the human struggles and stories of all people. So go see art, find art from other cultures, other religions, other orientations and perspectives. If we learn about each other, maybe we can finally see that we're all in this together. Art is a uniquely human expression of creativity. It helps us understand our past, people who are different from us, and ultimately, ourselves.

Reed Enger, "The Value of Art, Why should we care about art?," in Obelisk Art History , Published June 24, 2017; last modified November 08, 2022, http://www.arthistoryproject.com/essays/the-value-of-art/.

Introduction to Art

30,000 years of human creativity

Art History Methodologies

Eight ways to understand art