- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

Table of Contents

How To Write a Research Proposal

Writing a Research proposal involves several steps to ensure a well-structured and comprehensive document. Here is an explanation of each step:

1. Title and Abstract

- Choose a concise and descriptive title that reflects the essence of your research.

- Write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. It should provide a brief overview of your proposal.

2. Introduction:

- Provide an introduction to your research topic, highlighting its significance and relevance.

- Clearly state the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Discuss the background and context of the study, including previous research in the field.

3. Research Objectives

- Outline the specific objectives or aims of your research. These objectives should be clear, achievable, and aligned with the research problem.

4. Literature Review:

- Conduct a comprehensive review of relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings, identify gaps, and highlight how your research will contribute to the existing knowledge.

5. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to employ to address your research objectives.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques you will use.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate and suitable for your research.

6. Timeline:

- Create a timeline or schedule that outlines the major milestones and activities of your research project.

- Break down the research process into smaller tasks and estimate the time required for each task.

7. Resources:

- Identify the resources needed for your research, such as access to specific databases, equipment, or funding.

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources to carry out your research effectively.

8. Ethical Considerations:

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise during your research and explain how you plan to address them.

- If your research involves human subjects, explain how you will ensure their informed consent and privacy.

9. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

- Clearly state the expected outcomes or results of your research.

- Highlight the potential impact and significance of your research in advancing knowledge or addressing practical issues.

10. References:

- Provide a list of all the references cited in your proposal, following a consistent citation style (e.g., APA, MLA).

11. Appendices:

- Include any additional supporting materials, such as survey questionnaires, interview guides, or data analysis plans.

Research Proposal Format

The format of a research proposal may vary depending on the specific requirements of the institution or funding agency. However, the following is a commonly used format for a research proposal:

1. Title Page:

- Include the title of your research proposal, your name, your affiliation or institution, and the date.

2. Abstract:

- Provide a brief summary of your research proposal, highlighting the research problem, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

3. Introduction:

- Introduce the research topic and provide background information.

- State the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Explain the significance and relevance of the research.

- Review relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings and identify gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Explain how your research will contribute to filling those gaps.

5. Research Objectives:

- Clearly state the specific objectives or aims of your research.

- Ensure that the objectives are clear, focused, and aligned with the research problem.

6. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to use.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate for your research.

7. Timeline:

8. Resources:

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources effectively.

9. Ethical Considerations:

- If applicable, explain how you will ensure informed consent and protect the privacy of research participants.

10. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

11. References:

12. Appendices:

Research Proposal Template

Here’s a template for a research proposal:

1. Introduction:

2. Literature Review:

3. Research Objectives:

4. Methodology:

5. Timeline:

6. Resources:

7. Ethical Considerations:

8. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

9. References:

10. Appendices:

Research Proposal Sample

Title: The Impact of Online Education on Student Learning Outcomes: A Comparative Study

1. Introduction

Online education has gained significant prominence in recent years, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes by comparing them with traditional face-to-face instruction. The study will explore various aspects of online education, such as instructional methods, student engagement, and academic performance, to provide insights into the effectiveness of online learning.

2. Objectives

The main objectives of this research are as follows:

- To compare student learning outcomes between online and traditional face-to-face education.

- To examine the factors influencing student engagement in online learning environments.

- To assess the effectiveness of different instructional methods employed in online education.

- To identify challenges and opportunities associated with online education and suggest recommendations for improvement.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study Design

This research will utilize a mixed-methods approach to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. The study will include the following components:

3.2 Participants

The research will involve undergraduate students from two universities, one offering online education and the other providing face-to-face instruction. A total of 500 students (250 from each university) will be selected randomly to participate in the study.

3.3 Data Collection

The research will employ the following data collection methods:

- Quantitative: Pre- and post-assessments will be conducted to measure students’ learning outcomes. Data on student demographics and academic performance will also be collected from university records.

- Qualitative: Focus group discussions and individual interviews will be conducted with students to gather their perceptions and experiences regarding online education.

3.4 Data Analysis

Quantitative data will be analyzed using statistical software, employing descriptive statistics, t-tests, and regression analysis. Qualitative data will be transcribed, coded, and analyzed thematically to identify recurring patterns and themes.

4. Ethical Considerations

The study will adhere to ethical guidelines, ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Informed consent will be obtained, and participants will have the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

5. Significance and Expected Outcomes

This research will contribute to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on the impact of online education on student learning outcomes. The findings will help educational institutions and policymakers make informed decisions about incorporating online learning methods and improving the quality of online education. Moreover, the study will identify potential challenges and opportunities related to online education and offer recommendations for enhancing student engagement and overall learning outcomes.

6. Timeline

The proposed research will be conducted over a period of 12 months, including data collection, analysis, and report writing.

The estimated budget for this research includes expenses related to data collection, software licenses, participant compensation, and research assistance. A detailed budget breakdown will be provided in the final research plan.

8. Conclusion

This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes through a comparative study with traditional face-to-face instruction. By exploring various dimensions of online education, this research will provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and challenges associated with online learning. The findings will contribute to the ongoing discourse on educational practices and help shape future strategies for maximizing student learning outcomes in online education settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide...

Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

How To Write A Business Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

Proposal – Types, Examples, and Writing Guide

How to choose an Appropriate Method for Research?

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Steps in Developing a Research Proposal

Learning objectives.

- Identify the steps in developing a research proposal.

- Choose a topic and formulate a research question and working thesis.

- Develop a research proposal.

Writing a good research paper takes time, thought, and effort. Although this assignment is challenging, it is manageable. Focusing on one step at a time will help you develop a thoughtful, informative, well-supported research paper.

Your first step is to choose a topic and then to develop research questions, a working thesis, and a written research proposal. Set aside adequate time for this part of the process. Fully exploring ideas will help you build a solid foundation for your paper.

Choosing a Topic

When you choose a topic for a research paper, you are making a major commitment. Your choice will help determine whether you enjoy the lengthy process of research and writing—and whether your final paper fulfills the assignment requirements. If you choose your topic hastily, you may later find it difficult to work with your topic. By taking your time and choosing carefully, you can ensure that this assignment is not only challenging but also rewarding.

Writers understand the importance of choosing a topic that fulfills the assignment requirements and fits the assignment’s purpose and audience. (For more information about purpose and audience, see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” .) Choosing a topic that interests you is also crucial. You instructor may provide a list of suggested topics or ask that you develop a topic on your own. In either case, try to identify topics that genuinely interest you.

After identifying potential topic ideas, you will need to evaluate your ideas and choose one topic to pursue. Will you be able to find enough information about the topic? Can you develop a paper about this topic that presents and supports your original ideas? Is the topic too broad or too narrow for the scope of the assignment? If so, can you modify it so it is more manageable? You will ask these questions during this preliminary phase of the research process.

Identifying Potential Topics

Sometimes, your instructor may provide a list of suggested topics. If so, you may benefit from identifying several possibilities before committing to one idea. It is important to know how to narrow down your ideas into a concise, manageable thesis. You may also use the list as a starting point to help you identify additional, related topics. Discussing your ideas with your instructor will help ensure that you choose a manageable topic that fits the requirements of the assignment.

In this chapter, you will follow a writer named Jorge, who is studying health care administration, as he prepares a research paper. You will also plan, research, and draft your own research paper.

Jorge was assigned to write a research paper on health and the media for an introductory course in health care. Although a general topic was selected for the students, Jorge had to decide which specific issues interested him. He brainstormed a list of possibilities.

If you are writing a research paper for a specialized course, look back through your notes and course activities. Identify reading assignments and class discussions that especially engaged you. Doing so can help you identify topics to pursue.

- Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) in the news

- Sexual education programs

- Hollywood and eating disorders

- Americans’ access to public health information

- Media portrayal of health care reform bill

- Depictions of drugs on television

- The effect of the Internet on mental health

- Popularized diets (such as low-carbohydrate diets)

- Fear of pandemics (bird flu, HINI, SARS)

- Electronic entertainment and obesity

- Advertisements for prescription drugs

- Public education and disease prevention

Set a timer for five minutes. Use brainstorming or idea mapping to create a list of topics you would be interested in researching for a paper about the influence of the Internet on social networking. Do you closely follow the media coverage of a particular website, such as Twitter? Would you like to learn more about a certain industry, such as online dating? Which social networking sites do you and your friends use? List as many ideas related to this topic as you can.

Narrowing Your Topic

Once you have a list of potential topics, you will need to choose one as the focus of your essay. You will also need to narrow your topic. Most writers find that the topics they listed during brainstorming or idea mapping are broad—too broad for the scope of the assignment. Working with an overly broad topic, such as sexual education programs or popularized diets, can be frustrating and overwhelming. Each topic has so many facets that it would be impossible to cover them all in a college research paper. However, more specific choices, such as the pros and cons of sexual education in kids’ television programs or the physical effects of the South Beach diet, are specific enough to write about without being too narrow to sustain an entire research paper.

A good research paper provides focused, in-depth information and analysis. If your topic is too broad, you will find it difficult to do more than skim the surface when you research it and write about it. Narrowing your focus is essential to making your topic manageable. To narrow your focus, explore your topic in writing, conduct preliminary research, and discuss both the topic and the research with others.

Exploring Your Topic in Writing

“How am I supposed to narrow my topic when I haven’t even begun researching yet?” In fact, you may already know more than you realize. Review your list and identify your top two or three topics. Set aside some time to explore each one through freewriting. (For more information about freewriting, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .) Simply taking the time to focus on your topic may yield fresh angles.

Jorge knew that he was especially interested in the topic of diet fads, but he also knew that it was much too broad for his assignment. He used freewriting to explore his thoughts so he could narrow his topic. Read Jorge’s ideas.

Conducting Preliminary Research

Another way writers may focus a topic is to conduct preliminary research . Like freewriting, exploratory reading can help you identify interesting angles. Surfing the web and browsing through newspaper and magazine articles are good ways to start. Find out what people are saying about your topic on blogs and online discussion groups. Discussing your topic with others can also inspire you. Talk about your ideas with your classmates, your friends, or your instructor.

Jorge’s freewriting exercise helped him realize that the assigned topic of health and the media intersected with a few of his interests—diet, nutrition, and obesity. Preliminary online research and discussions with his classmates strengthened his impression that many people are confused or misled by media coverage of these subjects.

Jorge decided to focus his paper on a topic that had garnered a great deal of media attention—low-carbohydrate diets. He wanted to find out whether low-carbohydrate diets were as effective as their proponents claimed.

Writing at Work

At work, you may need to research a topic quickly to find general information. This information can be useful in understanding trends in a given industry or generating competition. For example, a company may research a competitor’s prices and use the information when pricing their own product. You may find it useful to skim a variety of reliable sources and take notes on your findings.

The reliability of online sources varies greatly. In this exploratory phase of your research, you do not need to evaluate sources as closely as you will later. However, use common sense as you refine your paper topic. If you read a fascinating blog comment that gives you a new idea for your paper, be sure to check out other, more reliable sources as well to make sure the idea is worth pursuing.

Review the list of topics you created in Note 11.18 “Exercise 1” and identify two or three topics you would like to explore further. For each of these topics, spend five to ten minutes writing about the topic without stopping. Then review your writing to identify possible areas of focus.

Set aside time to conduct preliminary research about your potential topics. Then choose a topic to pursue for your research paper.

Collaboration

Please share your topic list with a classmate. Select one or two topics on his or her list that you would like to learn more about and return it to him or her. Discuss why you found the topics interesting, and learn which of your topics your classmate selected and why.

A Plan for Research

Your freewriting and preliminary research have helped you choose a focused, manageable topic for your research paper. To work with your topic successfully, you will need to determine what exactly you want to learn about it—and later, what you want to say about it. Before you begin conducting in-depth research, you will further define your focus by developing a research question , a working thesis, and a research proposal.

Formulating a Research Question

In forming a research question, you are setting a goal for your research. Your main research question should be substantial enough to form the guiding principle of your paper—but focused enough to guide your research. A strong research question requires you not only to find information but also to put together different pieces of information, interpret and analyze them, and figure out what you think. As you consider potential research questions, ask yourself whether they would be too hard or too easy to answer.

To determine your research question, review the freewriting you completed earlier. Skim through books, articles, and websites and list the questions you have. (You may wish to use the 5WH strategy to help you formulate questions. See Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” for more information about 5WH questions.) Include simple, factual questions and more complex questions that would require analysis and interpretation. Determine your main question—the primary focus of your paper—and several subquestions that you will need to research to answer your main question.

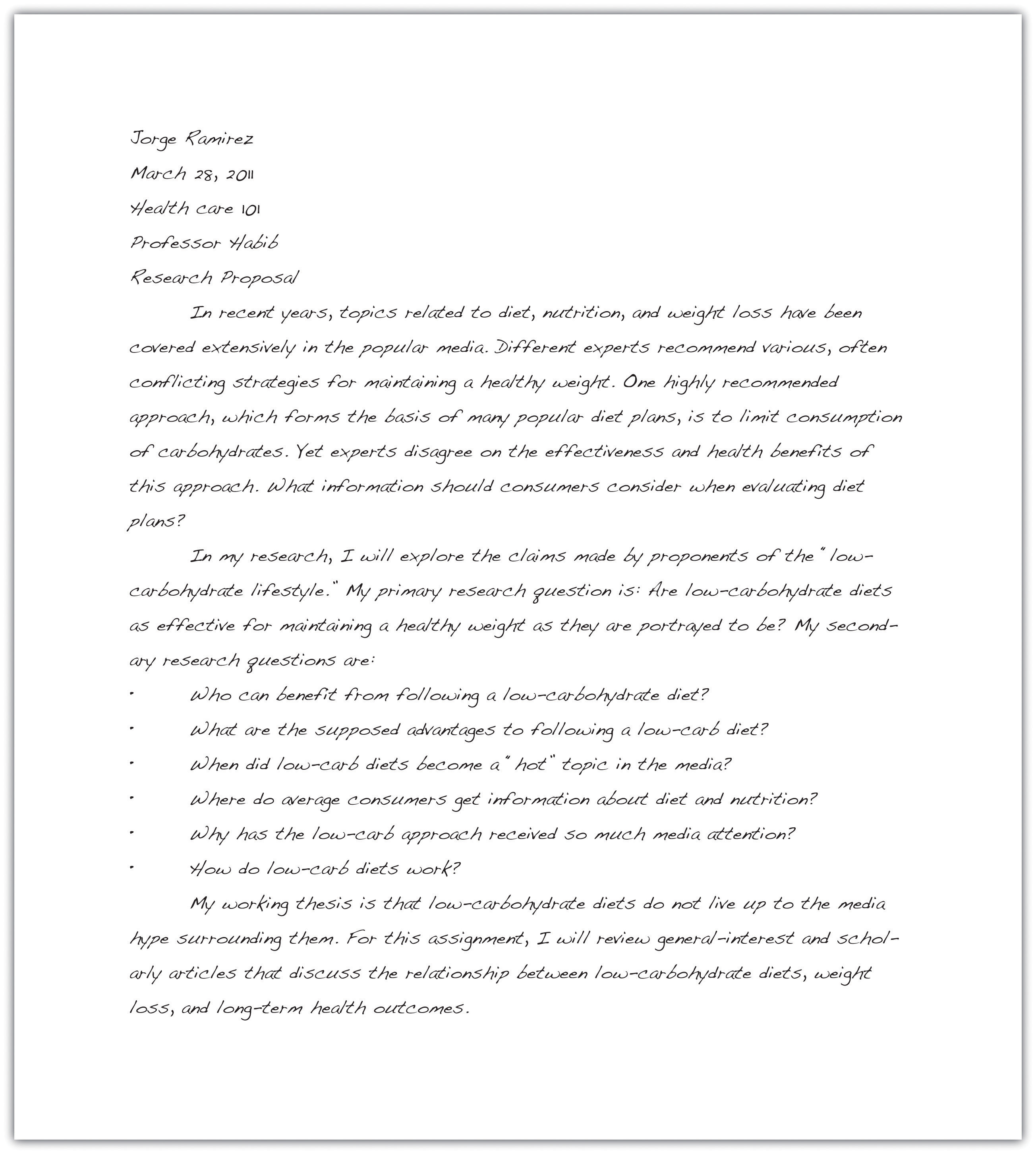

Here are the research questions Jorge will use to focus his research. Notice that his main research question has no obvious, straightforward answer. Jorge will need to research his subquestions, which address narrower topics, to answer his main question.

Using the topic you selected in Note 11.24 “Exercise 2” , write your main research question and at least four to five subquestions. Check that your main research question is appropriately complex for your assignment.

Constructing a Working ThesIs

A working thesis concisely states a writer’s initial answer to the main research question. It does not merely state a fact or present a subjective opinion. Instead, it expresses a debatable idea or claim that you hope to prove through additional research. Your working thesis is called a working thesis for a reason—it is subject to change. As you learn more about your topic, you may change your thinking in light of your research findings. Let your working thesis serve as a guide to your research, but do not be afraid to modify it based on what you learn.

Jorge began his research with a strong point of view based on his preliminary writing and research. Read his working thesis statement, which presents the point he will argue. Notice how it states Jorge’s tentative answer to his research question.

One way to determine your working thesis is to consider how you would complete sentences such as I believe or My opinion is . However, keep in mind that academic writing generally does not use first-person pronouns. These statements are useful starting points, but formal research papers use an objective voice.

Write a working thesis statement that presents your preliminary answer to the research question you wrote in Note 11.27 “Exercise 3” . Check that your working thesis statement presents an idea or claim that could be supported or refuted by evidence from research.

Creating a Research Proposal

A research proposal is a brief document—no more than one typed page—that summarizes the preliminary work you have completed. Your purpose in writing it is to formalize your plan for research and present it to your instructor for feedback. In your research proposal, you will present your main research question, related subquestions, and working thesis. You will also briefly discuss the value of researching this topic and indicate how you plan to gather information.

When Jorge began drafting his research proposal, he realized that he had already created most of the pieces he needed. However, he knew he also had to explain how his research would be relevant to other future health care professionals. In addition, he wanted to form a general plan for doing the research and identifying potentially useful sources. Read Jorge’s research proposal.

Before you begin a new project at work, you may have to develop a project summary document that states the purpose of the project, explains why it would be a wise use of company resources, and briefly outlines the steps involved in completing the project. This type of document is similar to a research proposal. Both documents define and limit a project, explain its value, discuss how to proceed, and identify what resources you will use.

Writing Your Own Research Proposal

Now you may write your own research proposal, if you have not done so already. Follow the guidelines provided in this lesson.

Key Takeaways

- Developing a research proposal involves the following preliminary steps: identifying potential ideas, choosing ideas to explore further, choosing and narrowing a topic, formulating a research question, and developing a working thesis.

- A good topic for a research paper interests the writer and fulfills the requirements of the assignment.

- Defining and narrowing a topic helps writers conduct focused, in-depth research.

- Writers conduct preliminary research to identify possible topics and research questions and to develop a working thesis.

- A good research question interests readers, is neither too broad nor too narrow, and has no obvious answer.

- A good working thesis expresses a debatable idea or claim that can be supported with evidence from research.

- Writers create a research proposal to present their topic, main research question, subquestions, and working thesis to an instructor for approval or feedback.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

What (Exactly) Is A Research Proposal?

A simple explainer with examples + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020 (Updated April 2023)

Whether you’re nearing the end of your degree and your dissertation is on the horizon, or you’re planning to apply for a PhD program, chances are you’ll need to craft a convincing research proposal . If you’re on this page, you’re probably unsure exactly what the research proposal is all about. Well, you’ve come to the right place.

Overview: Research Proposal Basics

- What a research proposal is

- What a research proposal needs to cover

- How to structure your research proposal

- Example /sample proposals

- Proposal writing FAQs

- Key takeaways & additional resources

What is a research proposal?

Simply put, a research proposal is a structured, formal document that explains what you plan to research (your research topic), why it’s worth researching (your justification), and how you plan to investigate it (your methodology).

The purpose of the research proposal (its job, so to speak) is to convince your research supervisor, committee or university that your research is suitable (for the requirements of the degree program) and manageable (given the time and resource constraints you will face).

The most important word here is “ convince ” – in other words, your research proposal needs to sell your research idea (to whoever is going to approve it). If it doesn’t convince them (of its suitability and manageability), you’ll need to revise and resubmit . This will cost you valuable time, which will either delay the start of your research or eat into its time allowance (which is bad news).

What goes into a research proposal?

A good dissertation or thesis proposal needs to cover the “ what “, “ why ” and” how ” of the proposed study. Let’s look at each of these attributes in a little more detail:

Your proposal needs to clearly articulate your research topic . This needs to be specific and unambiguous . Your research topic should make it clear exactly what you plan to research and in what context. Here’s an example of a well-articulated research topic:

An investigation into the factors which impact female Generation Y consumer’s likelihood to promote a specific makeup brand to their peers: a British context

As you can see, this topic is extremely clear. From this one line we can see exactly:

- What’s being investigated – factors that make people promote or advocate for a brand of a specific makeup brand

- Who it involves – female Gen-Y consumers

- In what context – the United Kingdom

So, make sure that your research proposal provides a detailed explanation of your research topic . If possible, also briefly outline your research aims and objectives , and perhaps even your research questions (although in some cases you’ll only develop these at a later stage). Needless to say, don’t start writing your proposal until you have a clear topic in mind , or you’ll end up waffling and your research proposal will suffer as a result of this.

Need a helping hand?

As we touched on earlier, it’s not good enough to simply propose a research topic – you need to justify why your topic is original . In other words, what makes it unique ? What gap in the current literature does it fill? If it’s simply a rehash of the existing research, it’s probably not going to get approval – it needs to be fresh.

But, originality alone is not enough. Once you’ve ticked that box, you also need to justify why your proposed topic is important . In other words, what value will it add to the world if you achieve your research aims?

As an example, let’s look at the sample research topic we mentioned earlier (factors impacting brand advocacy). In this case, if the research could uncover relevant factors, these findings would be very useful to marketers in the cosmetics industry, and would, therefore, have commercial value . That is a clear justification for the research.

So, when you’re crafting your research proposal, remember that it’s not enough for a topic to simply be unique. It needs to be useful and value-creating – and you need to convey that value in your proposal. If you’re struggling to find a research topic that makes the cut, watch our video covering how to find a research topic .

It’s all good and well to have a great topic that’s original and valuable, but you’re not going to convince anyone to approve it without discussing the practicalities – in other words:

- How will you actually undertake your research (i.e., your methodology)?

- Is your research methodology appropriate given your research aims?

- Is your approach manageable given your constraints (time, money, etc.)?

While it’s generally not expected that you’ll have a fully fleshed-out methodology at the proposal stage, you’ll likely still need to provide a high-level overview of your research methodology . Here are some important questions you’ll need to address in your research proposal:

- Will you take a qualitative , quantitative or mixed -method approach?

- What sampling strategy will you adopt?

- How will you collect your data (e.g., interviews, surveys, etc)?

- How will you analyse your data (e.g., descriptive and inferential statistics , content analysis, discourse analysis, etc, .)?

- What potential limitations will your methodology carry?

So, be sure to give some thought to the practicalities of your research and have at least a basic methodological plan before you start writing up your proposal. If this all sounds rather intimidating, the video below provides a good introduction to research methodology and the key choices you’ll need to make.

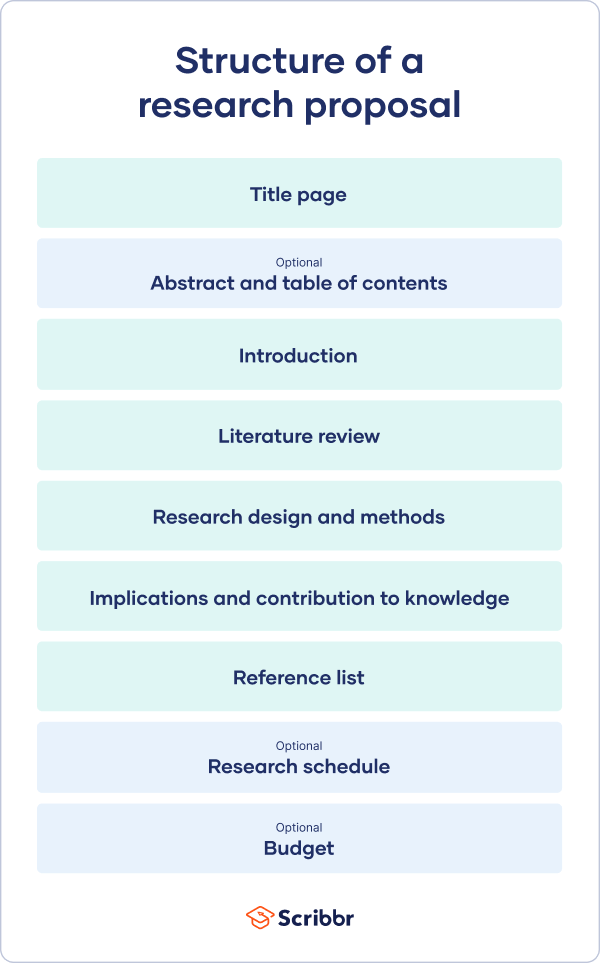

How To Structure A Research Proposal

Now that we’ve covered the key points that need to be addressed in a proposal, you may be wondering, “ But how is a research proposal structured? “.

While the exact structure and format required for a research proposal differs from university to university, there are four “essential ingredients” that commonly make up the structure of a research proposal:

- A rich introduction and background to the proposed research

- An initial literature review covering the existing research

- An overview of the proposed research methodology

- A discussion regarding the practicalities (project plans, timelines, etc.)

In the video below, we unpack each of these four sections, step by step.

Research Proposal Examples/Samples

In the video below, we provide a detailed walkthrough of two successful research proposals (Master’s and PhD-level), as well as our popular free proposal template.

Proposal Writing FAQs

How long should a research proposal be.

This varies tremendously, depending on the university, the field of study (e.g., social sciences vs natural sciences), and the level of the degree (e.g. undergraduate, Masters or PhD) – so it’s always best to check with your university what their specific requirements are before you start planning your proposal.

As a rough guide, a formal research proposal at Masters-level often ranges between 2000-3000 words, while a PhD-level proposal can be far more detailed, ranging from 5000-8000 words. In some cases, a rough outline of the topic is all that’s needed, while in other cases, universities expect a very detailed proposal that essentially forms the first three chapters of the dissertation or thesis.

The takeaway – be sure to check with your institution before you start writing.

How do I choose a topic for my research proposal?

Finding a good research topic is a process that involves multiple steps. We cover the topic ideation process in this video post.

How do I write a literature review for my proposal?

While you typically won’t need a comprehensive literature review at the proposal stage, you still need to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the key literature and are able to synthesise it. We explain the literature review process here.

How do I create a timeline and budget for my proposal?

We explain how to craft a project plan/timeline and budget in Research Proposal Bootcamp .

Which referencing format should I use in my research proposal?

The expectations and requirements regarding formatting and referencing vary from institution to institution. Therefore, you’ll need to check this information with your university.

What common proposal writing mistakes do I need to look out for?

We’ve create a video post about some of the most common mistakes students make when writing a proposal – you can access that here . If you’re short on time, here’s a quick summary:

- The research topic is too broad (or just poorly articulated).

- The research aims, objectives and questions don’t align.

- The research topic is not well justified.

- The study has a weak theoretical foundation.

- The research design is not well articulated well enough.

- Poor writing and sloppy presentation.

- Poor project planning and risk management.

- Not following the university’s specific criteria.

Key Takeaways & Additional Resources

As you write up your research proposal, remember the all-important core purpose: to convince . Your research proposal needs to sell your study in terms of suitability and viability. So, focus on crafting a convincing narrative to ensure a strong proposal.

At the same time, pay close attention to your university’s requirements. While we’ve covered the essentials here, every institution has its own set of expectations and it’s essential that you follow these to maximise your chances of approval.

By the way, we’ve got plenty more resources to help you fast-track your research proposal. Here are some of our most popular resources to get you started:

- Proposal Writing 101 : A Introductory Webinar

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : The Ultimate Online Course

- Template : A basic template to help you craft your proposal

If you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your research proposal, be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the proposal development process (and the entire research journey), step by step.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

51 Comments

I truly enjoyed this video, as it was eye-opening to what I have to do in the preparation of preparing a Research proposal.

I would be interested in getting some coaching.

I real appreciate on your elaboration on how to develop research proposal,the video explains each steps clearly.

Thank you for the video. It really assisted me and my niece. I am a PhD candidate and she is an undergraduate student. It is at times, very difficult to guide a family member but with this video, my job is done.

In view of the above, I welcome more coaching.

Wonderful guidelines, thanks

This is very helpful. Would love to continue even as I prepare for starting my masters next year.

Thanks for the work done, the text was helpful to me

Bundle of thanks to you for the research proposal guide it was really good and useful if it is possible please send me the sample of research proposal

You’re most welcome. We don’t have any research proposals that we can share (the students own the intellectual property), but you might find our research proposal template useful: https://gradcoach.com/research-proposal-template/

Cheruiyot Moses Kipyegon

Thanks alot. It was an eye opener that came timely enough before my imminent proposal defense. Thanks, again

thank you very much your lesson is very interested may God be with you

I am an undergraduate student (First Degree) preparing to write my project,this video and explanation had shed more light to me thanks for your efforts keep it up.

Very useful. I am grateful.

this is a very a good guidance on research proposal, for sure i have learnt something

Wonderful guidelines for writing a research proposal, I am a student of m.phil( education), this guideline is suitable for me. Thanks

You’re welcome 🙂

Thank you, this was so helpful.

A really great and insightful video. It opened my eyes as to how to write a research paper. I would like to receive more guidance for writing my research paper from your esteemed faculty.

Thank you, great insights

Thank you, great insights, thank you so much, feeling edified

Wow thank you, great insights, thanks a lot

Thank you. This is a great insight. I am a student preparing for a PhD program. I am requested to write my Research Proposal as part of what I am required to submit before my unconditional admission. I am grateful having listened to this video which will go a long way in helping me to actually choose a topic of interest and not just any topic as well as to narrow down the topic and be specific about it. I indeed need more of this especially as am trying to choose a topic suitable for a DBA am about embarking on. Thank you once more. The video is indeed helpful.

Have learnt a lot just at the right time. Thank you so much.

thank you very much ,because have learn a lot things concerning research proposal and be blessed u for your time that you providing to help us

Hi. For my MSc medical education research, please evaluate this topic for me: Training Needs Assessment of Faculty in Medical Training Institutions in Kericho and Bomet Counties

I have really learnt a lot based on research proposal and it’s formulation

Thank you. I learn much from the proposal since it is applied

Your effort is much appreciated – you have good articulation.

You have good articulation.

I do applaud your simplified method of explaining the subject matter, which indeed has broaden my understanding of the subject matter. Definitely this would enable me writing a sellable research proposal.

This really helping

Great! I liked your tutoring on how to find a research topic and how to write a research proposal. Precise and concise. Thank you very much. Will certainly share this with my students. Research made simple indeed.

Thank you very much. I an now assist my students effectively.

Thank you very much. I can now assist my students effectively.

I need any research proposal

Thank you for these videos. I will need chapter by chapter assistance in writing my MSc dissertation

Very helpfull

the videos are very good and straight forward

thanks so much for this wonderful presentations, i really enjoyed it to the fullest wish to learn more from you

Thank you very much. I learned a lot from your lecture.

I really enjoy the in-depth knowledge on research proposal you have given. me. You have indeed broaden my understanding and skills. Thank you

interesting session this has equipped me with knowledge as i head for exams in an hour’s time, am sure i get A++

This article was most informative and easy to understand. I now have a good idea of how to write my research proposal.

Thank you very much.

Wow, this literature is very resourceful and interesting to read. I enjoyed it and I intend reading it every now then.

Thank you for the clarity

Thank you. Very helpful.

Thank you very much for this essential piece. I need 1o1 coaching, unfortunately, your service is not available in my country. Anyways, a very important eye-opener. I really enjoyed it. A thumb up to Gradcoach

What is JAM? Please explain.

Thank you so much for these videos. They are extremely helpful! God bless!

very very wonderful…

thank you for the video but i need a written example

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide

Published on September 24, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on March 27, 2023.

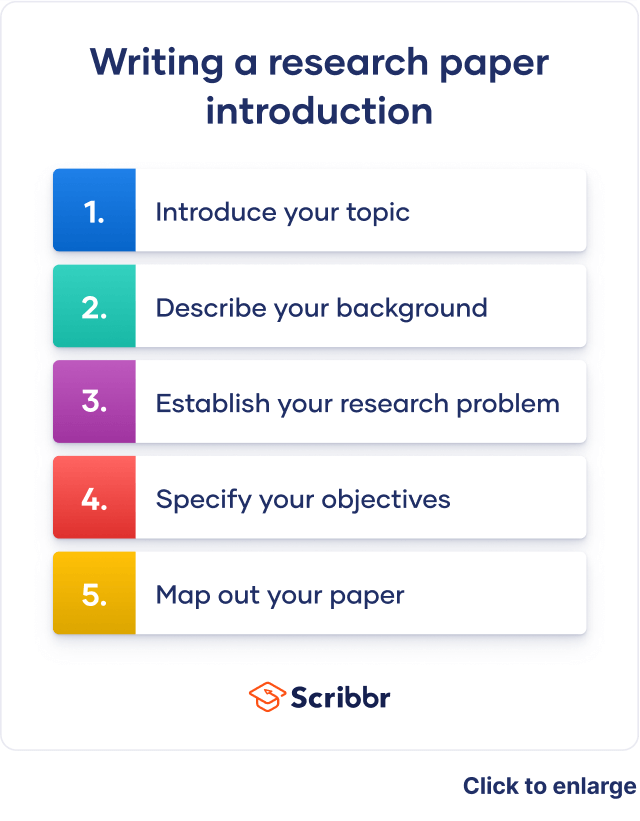

The introduction to a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your topic and get the reader interested

- Provide background or summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Detail your specific research problem and problem statement

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The introduction looks slightly different depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or constructs an argument by engaging with a variety of sources.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: introduce your topic, step 2: describe the background, step 3: establish your research problem, step 4: specify your objective(s), step 5: map out your paper, research paper introduction examples, frequently asked questions about the research paper introduction.

The first job of the introduction is to tell the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening hook.

The hook is a striking opening sentence that clearly conveys the relevance of your topic. Think of an interesting fact or statistic, a strong statement, a question, or a brief anecdote that will get the reader wondering about your topic.

For example, the following could be an effective hook for an argumentative paper about the environmental impact of cattle farming:

A more empirical paper investigating the relationship of Instagram use with body image issues in adolescent girls might use the following hook:

Don’t feel that your hook necessarily has to be deeply impressive or creative. Clarity and relevance are still more important than catchiness. The key thing is to guide the reader into your topic and situate your ideas.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

This part of the introduction differs depending on what approach your paper is taking.

In a more argumentative paper, you’ll explore some general background here. In a more empirical paper, this is the place to review previous research and establish how yours fits in.

Argumentative paper: Background information

After you’ve caught your reader’s attention, specify a bit more, providing context and narrowing down your topic.

Provide only the most relevant background information. The introduction isn’t the place to get too in-depth; if more background is essential to your paper, it can appear in the body .

Empirical paper: Describing previous research

For a paper describing original research, you’ll instead provide an overview of the most relevant research that has already been conducted. This is a sort of miniature literature review —a sketch of the current state of research into your topic, boiled down to a few sentences.

This should be informed by genuine engagement with the literature. Your search can be less extensive than in a full literature review, but a clear sense of the relevant research is crucial to inform your own work.

Begin by establishing the kinds of research that have been done, and end with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to respond to.

The next step is to clarify how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses.

Argumentative paper: Emphasize importance

In an argumentative research paper, you can simply state the problem you intend to discuss, and what is original or important about your argument.

Empirical paper: Relate to the literature

In an empirical research paper, try to lead into the problem on the basis of your discussion of the literature. Think in terms of these questions:

- What research gap is your work intended to fill?

- What limitations in previous work does it address?

- What contribution to knowledge does it make?

You can make the connection between your problem and the existing research using phrases like the following.

Now you’ll get into the specifics of what you intend to find out or express in your research paper.

The way you frame your research objectives varies. An argumentative paper presents a thesis statement, while an empirical paper generally poses a research question (sometimes with a hypothesis as to the answer).

Argumentative paper: Thesis statement

The thesis statement expresses the position that the rest of the paper will present evidence and arguments for. It can be presented in one or two sentences, and should state your position clearly and directly, without providing specific arguments for it at this point.

Empirical paper: Research question and hypothesis

The research question is the question you want to answer in an empirical research paper.

Present your research question clearly and directly, with a minimum of discussion at this point. The rest of the paper will be taken up with discussing and investigating this question; here you just need to express it.

A research question can be framed either directly or indirectly.

- This study set out to answer the following question: What effects does daily use of Instagram have on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls?

- We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls.

If your research involved testing hypotheses , these should be stated along with your research question. They are usually presented in the past tense, since the hypothesis will already have been tested by the time you are writing up your paper.

For example, the following hypothesis might respond to the research question above:

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The final part of the introduction is often dedicated to a brief overview of the rest of the paper.

In a paper structured using the standard scientific “introduction, methods, results, discussion” format, this isn’t always necessary. But if your paper is structured in a less predictable way, it’s important to describe the shape of it for the reader.

If included, the overview should be concise, direct, and written in the present tense.

- This paper will first discuss several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then will go on to …

- This paper first discusses several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then goes on to …

Full examples of research paper introductions are shown in the tabs below: one for an argumentative paper, the other for an empirical paper.

- Argumentative paper

- Empirical paper

Are cows responsible for climate change? A recent study (RIVM, 2019) shows that cattle farmers account for two thirds of agricultural nitrogen emissions in the Netherlands. These emissions result from nitrogen in manure, which can degrade into ammonia and enter the atmosphere. The study’s calculations show that agriculture is the main source of nitrogen pollution, accounting for 46% of the country’s total emissions. By comparison, road traffic and households are responsible for 6.1% each, the industrial sector for 1%. While efforts are being made to mitigate these emissions, policymakers are reluctant to reckon with the scale of the problem. The approach presented here is a radical one, but commensurate with the issue. This paper argues that the Dutch government must stimulate and subsidize livestock farmers, especially cattle farmers, to transition to sustainable vegetable farming. It first establishes the inadequacy of current mitigation measures, then discusses the various advantages of the results proposed, and finally addresses potential objections to the plan on economic grounds.

The rise of social media has been accompanied by a sharp increase in the prevalence of body image issues among women and girls. This correlation has received significant academic attention: Various empirical studies have been conducted into Facebook usage among adolescent girls (Tiggermann & Slater, 2013; Meier & Gray, 2014). These studies have consistently found that the visual and interactive aspects of the platform have the greatest influence on body image issues. Despite this, highly visual social media (HVSM) such as Instagram have yet to be robustly researched. This paper sets out to address this research gap. We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls. It was hypothesized that daily Instagram use would be associated with an increase in body image concerns and a decrease in self-esteem ratings.

The introduction of a research paper includes several key elements:

- A hook to catch the reader’s interest

- Relevant background on the topic

- Details of your research problem

and your problem statement

- A thesis statement or research question

- Sometimes an overview of the paper

Don’t feel that you have to write the introduction first. The introduction is often one of the last parts of the research paper you’ll write, along with the conclusion.

This is because it can be easier to introduce your paper once you’ve already written the body ; you may not have the clearest idea of your arguments until you’ve written them, and things can change during the writing process .

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis —a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, March 27). Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved April 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-paper/research-paper-introduction/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, writing a research paper conclusion | step-by-step guide, research paper format | apa, mla, & chicago templates, what is your plagiarism score.

How To Write Chapter 1 Of A PhD Thesis Proposal (A Practical Guide)

After submitting a concept paper and your supervisor gives you the go-ahead, then it is time to start writing the proposal for your PhD thesis or dissertation.

The format of a thesis proposal varies from one institution to another but generally has three main chapters: chapter 1 (introduction), chapter 2 (literature review), and chapter 3 (research methodology).

Related post: How To Choose a Research Topic For Your PhD Thesis (7 Key Factors to Consider)

While in some institutions PhD students may be required to write more chapters, these three chapters are the meat of any thesis proposal. This article focuses on how to write chapter 1 of a PhD thesis proposal.

Chapter 1 of a thesis proposal has about 10 sections discussed below:

Introduction to the chapter

Background to the study, statement of the problem, justification of the study, significance of the study, objectives of the study and/or research questions, scope of the study, limitations and delimitations of the study, definition of terms, chapter summary, final thoughts on how to write chapter 1 of a phd thesis proposal, related posts.

This is the first section of chapter 1 of a thesis proposal. It is normally short about a paragraph in length. Its purpose is to inform the readers what the chapter is all about.

This section is the longest in chapter 1 of a thesis proposal.

It provides the context within which the study will be undertaken.

It gives a historical explanation of the issue under investigation.

It is important to use existing data and statistics to show the magnitude of the issue. Grey literature (for instance, reports from the government, non-governmental organisations, local institutions and international organisations among others) play an important role when providing the background to the study.

The background is often given starting from a general perspective and narrows down to a specific perspective.

For example, if the proposal is on maternal health in South Africa, then the background of the study will discuss maternal health from the global perspective, then maternal health in Africa, and then it will narrow down to maternal health in South Africa. It will provide data and statistics provided by reports from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and demographic and health surveys (DHS) of various countries and specifically South Africa, among other reports. Such information paints a clear picture of the problem under investigation and sets the stage for the discussion of the problem statement.

The background to the study should be clear and comprehensive enough such that your readers will be on the same page after reading the section, irrespective of their prior knowledge in your research topic.

While reviewing literature for this section, a good practice is to build mind maps that highlight the important concepts for the study topic and how those concepts relate to each other.

It is also referred to as problem statement or issue under investigation.

The statement of the problem is the elephant in the “chapter 1” room. It is what most students struggle with and the area that can make or break a proposal defense.

It is very common to hear supervisors or defense panelists make comments such as:

“I don’t see any problem here.”

“This problem is not a problem.”

“This problem does not warrant a PhD-level study.”

When writing the statement of the problem, start the section with the problem, as in… The problem (or issue) under investigation is ….

After stating the problem then follow it up with an explanation of why it is a problem.

For PhD students, the problem under investigation should be complex enough to warrant a doctoral-level study and at the same time it should add to the body of knowledge in your chosen field of study. The latter – addition to knowledge – is what distinguishes a PhD-level thesis from a Masters-level thesis.

While crafting the problem statement it is also important to remember that the problem will influence the research objectives and the research methodology as well. The student should therefore think through these aspects carefully.

The justification is used to address the need for conducting the study and addressing the problem. It therefore follows the problem statement.

It is also referred to as the rationale for the study and addresses the “why” of the study: Why does this problem warrant an investigation? What is the purpose for carrying out the study?

In the example of maternal health in South Africa, the rationale or justification for the study would be the high maternal mortality ratios in South Africa and their undesirable effects on children and family. Therefore the study would help bring to light the major causes of maternal mortality in the country and how they can best be mitigated.

Whereas the justification of the study addresses the need for the study, the significance of the study highlights the benefits that would accrue after the study is completed.

The significance can be looked at from two perspectives:

- Academic perspective

- Practical perspective

For the academic perspective , the significance entails how the study would contribute to the existing body of knowledge in the chosen topic. Will it add to the methodology? Theory? New data? Will it study a population or phenomenon that has been neglected?

For PhD students, the addition to the body of knowledge is key, and should always be at the back of the student’s mind.

For the practical perspective , the significance of the study would be the impact and benefits that different stakeholders would derive from the findings of the study.

Depending on the study, the stakeholders may include: the Government, policymakers, different ministries and their agencies, different institutions, individuals, a community etc. This will vary from one study to another.

The significance of the study is best presented from a general to specific manner, like an inverted pyramid.

Each beneficiary is discussed separately.

Research questions are the question form of the research objectives. Depending on your institution and/or department where you are doing your PhD you may have both objectives and research questions or either.

There are two types of objectives: the general objective and the specific objectives. The general objective is a reflection of the study topic while the specific objectives are a breakdown of the general objective.

Coming up with good research objectives is an important step of any PhD thesis proposal. This is because the research objectives will determine whether the research problem will be adequately addressed and at the same time it will influence the research methodology that the study will adopt.

Research objectives should therefore emanate from the research problem.

While crafting the objectives, think about all those things that you would like to accomplish for your study and if by doing them they will address the research problem in totality.

Once you’ve noted all those activities that you would like to undertake, group the like ones together so as to narrow them down to 4 or 5 strong objectives.

The number of research objectives that PhD students should come up with will be determined by the requirements of their institution. However, the objectives should be adequate enough such that a single paper can be produced from each objective. This is important in ensuring that the PhD student publishes as many papers as is required by their institution.

Objectives are usually stated using action verbs. For instance: to examine, to analyse, to understand, to review, to investigate… etc.

It is important to understand the meaning of the action verbs used in the research objectives because different action verbs imply different methodology approaches. For instance: to analyse implies a quantitative approach, whereas to explore implies a qualitative approach.

Therefore, if a study will use purely quantitative research methodology, then the action verbs for the research objectives should strictly reflect that. Same case applies to qualitative studies. Studies that use a mixed-methods approach can have a mix of the action verbs.

Have a variety of the action verbs in your research objectives. Don’t just use the same action verb throughout.

Useful tip: To have a good idea of the action verbs that scholars use, create an Excel file with three columns: 1) action verb, 2) example of research objective, and 3) research methodology used. Then every time you read a journal paper, note down the objectives stated in that paper and fill in the three columns respectively. Besides journal papers, past PhD theses and dissertations are a good source of how research objectives are stated.

Another important point to remember is that the research objectives will form the basis of the discussion chapter. Each research objective will be discussed separately and will form its own sub-chapter under the discussion chapter. This is why the complexity of the research objectives is important especially for PhD students.

The scope of the study simply means the boundaries or the space within which the study will be undertaken.

Most studies have the potential of covering a wider scope than stated but because of time and budget constraints the scope gets narrowed down.

When defining the scope for a PhD study, it should not be too narrow or too wide but rather it should be adequate enough to meet the requirements of the program.

The scope chosen by the student should always be justified.

Limitations refer to factors that may affect a study which are not under the control of the student.

Delimitations on the other hand are factors that may affect the study for which the student has control.

Limitations are therefore caused by circumstances while delimitations are a matter of choice of the student.

It is therefore important for the student to justify their delimitations and mitigate their study’s limitations.

Examples of study limitations:

– political unrest in a region of interest: this can be mitigated by choosing another region for the study.

– covid-19 restrictions may limit physical collection of data: this can be mitigated by collecting data via telephone interviews or emailing questionnaires to the respondents.

Examples of study delimitations:

– choice of a particular community as the unit of the study: in this case the student should justify why that particular community was chosen over others.

– use of quantitative research methodology only: in this case the student should justify why they chose the research methodology over mixed-methods research.

The definition of key terms used in the study is important because it helps the readers understand the main concepts of the study. Not all readers have the background information or knowledge about the focus of the study.

However, the definitions used should be the denotative definitions, rather than the connotative (dictionary) definitions. Therefore the context within which the terms have been used should be provided.

This is the last section of the introduction chapter and it basically informs the reader what the chapter covered.

Like the introduction to the chapter, the chapter summary should be short: about one paragraph in length.

Chapter 1 of a PhD thesis proposal is an important chapter because it lays the foundation for the rest of the proposal and the thesis itself. Its role is to inspire and motivate the readers to read on. The most challenging task with chapter 1 is learning how to state the problem in a manner that is clear and to the point. For PhD students, the research problem should be complex enough to warrant a doctoral-level study.

Whereas the format of the chapter may vary from one institution to another, the sections presented in this article provide a guide to most of what is required for the chapter to be complete. Learning how to write chapter 1 of a PhD thesis proposal requires constant writing practice as well as reading of many past PhD theses and dissertations.

How To Write Chapter 2 Of A PhD Thesis Proposal (A Beginner’s Guide)

How To Write Chapter 3 Of A PhD Thesis Proposal (A Detailed Guide)

Grace Njeri-Otieno

Grace Njeri-Otieno is a Kenyan, a wife, a mom, and currently a PhD student, among many other balls she juggles. She holds a Bachelors' and Masters' degrees in Economics and has more than 7 years' experience with an INGO. She was inspired to start this site so as to share the lessons learned throughout her PhD journey with other PhD students. Her vision for this site is "to become a go-to resource center for PhD students in all their spheres of learning."

Recent Content

SPSS Tutorial #11: Correlation Analysis in SPSS

In this post, I discuss what correlation is, the two most common types of correlation statistics used (Pearson and Spearman), and how to conduct correlation analysis in SPSS. What is correlation...

SPSS Tutorial #10: How to Check for Normality of Data in SPSS

The normality assumption states that the data is normally distributed. This post touches on the importance of normality of data and illustrates how to check for normality of data in SPSS. Why...

- Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Apply to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Give to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Search Form

Components of a research proposal.

In general, the proposal components include:

Introduction: Provides reader with a broad overview of problem in context.

Statement of problem: Answers the question, “What research problem are you going to investigate?”

Literature review: Shows how your approach builds on existing research; helps you identify methodological and design issues in studies similar to your own; introduces you to measurement tools others have used effectively; helps you interpret findings; and ties results of your work to those who’ve preceded you.

Research design and methods: Describes how you’ll go about answering your research questions and confirming your hypothesis(es). Lists the hypothesis(es) to be tested, or states research question you’ll ask to seek a solution to your research problem. Include as much detail as possible: measurement instruments and procedures, subjects and sample size.

The research design is what you’ll also need to submit for approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) or the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) if your research involves human or animal subjects, respectively.

Timeline: Breaks your project into small, easily doable steps via backwards calendar.

- Request new password

- Create a new account

Research Methods in Early Childhood: An Introductory Guide

Student resources, chapter 2: the research proposal.

Abdulai, R.T. and Owusu-Ansah, A. (2014) ‘Essential ingredients of a good research proposal for undergraduate and postgraduate students in the social sciences’, SAGE Open , 4(3): 1–11. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2158244014548178

This article is a comprehensive guide to writing research proposals. It is recommended that you read Chapters 1 and 2 in the textbook before you read this article as the article looks at both research proposals and research design. You will discover that terminology is not fixed. Different authors will use different terms to describe the same thing. For example, in this article the research question is called the research objective. Your institution may expect you to use specific terminology, but as long as you define your terms and use them consistently then these differences are of no account.

Wharewera-Mika, J., Cooper, E., Kool, B., Pereira, S. and Kelly, P. (2015) ‘Caregivers’ voices: the experiences of caregivers of children who sustained serious accidental and non-accidental head injury in early childhood’, Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 21(2): 268–86. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1359104515589636

This article looks at parents’ experiences of caring for children who received a head injury before the age of 5. It is a New Zealand study. Imagine you were the researchers at the beginning of the research process. They were required to present a research proposal to one of New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committees. Outline what their proposal might look like (minus the literature review).

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11 The Body of the Research Proposal

Drawing on guidelines developed in the UBC graduate guide to writing proposals (Petrina, 2009), we highlight eight steps for constructing an effective research proposal:

- Presenting the topic

- Literature Review

- Identifying the Gap

- Research Questions that addresses the Gap

- Methods to address the research questions

Data Analysis

- Summary, Limitations and Implications

In addition to those eight sections, research proposals frequently include a research timeline. We discuss each of these eight sections as well as producing a research timeline below.

Presenting The Topic (Statement of Research Problem)

The research proposal should begin with a hook to entice your readers. Like a steaming fresh pie on a windowsill, you want to allure your reader by presenting your topic (the pie on the sill) and then alluding to its importance (the delicious scent and taste of the cooling cherry pie). This can be done in many ways, so long as you are able to entice your reader to the core themes of your research. Some suggestions include:

Highlighting a paradox that your work will attempt to resolve e.g., “Why is it that social research has been shown to bring about higher net-positive outcomes than natural scientific research, but is funded less?” or “Why is it that women earn less than men in meritocratic societies even though they have more qualifications?” Paradoxes are popular because they draw on problematics (see Chapter 1) and indicate an obstacle in the thinking of fellow researchers that you may offer hope in resolving.

- Presenting a narrative introduction (often used in ethnographic papers) to the problem at hand. The following opening statement from Bowen, Elliott & Brenton (2014, p. 20) illustrates:

It’s a hot, sticky Fourth of July in North Carolina, and Leanne, a married working-class black mother of three, is in her cramped kitchen. She’s been cooking for several hours, lovingly preparing potato salad, beef ribs, chicken legs, and collards for her family. Abruptly, her mother decides to leave before eating anything. “But you haven’t eaten,” Leanne says. “You know I prefer my own potato salad,” says her mom. She takes a plateful to go anyway,

- Provide an historical overview of the problem, discussing its significance in history and indicating how that interrelates to the present: “On January 23rd, 2020, tears were shed as cabbies heard the news of Uber’s approval to operate in the city of Vancouver.”

- Introduce your positionality to the problem: How did it come of concern? How are you personally related to the social problem in question? The following introduction by Germon (1999, p.687) illustrates:

Throughout the paper I locate myself as part of the disabled peoples movement, and write from a position of a shared value base and analyses of a collective experience. In doing so, I make no apology for flouting academic pretentions of objectivity and neutrality. Rather, I believe I am giving essential information which clarifies my motivation and political position

- Begin with a quotation : Because this is an overused technique, if you use it, make sure that it addresses your research question and that you can explicitly relate to it in the body of your introduction. Do not start with a quotation for the sake of.

- Begin with a concession : Start with a statement recognizing an opinion or approach different from the one you plan to take in your thesis. You can acknowledge the merits in a previous approach but show how you will improve it or make a different argument, e.g., “Although critical theory and antiracism explain oppression and exploitation in contemporary society, they do not fully address the experiences of Indigenous peoples”.

- Start with an interesting fact or statistics : This is a sure way to draw attention to the topic and its significance e.g. “Canada is the fourth most popular destination country in the world for international students in 2018, with close to half a million international students” (CBIE, 2018)

- A definition : You may start by defining a key term in your research topic. This is useful if it distinguishes how you plan to use a term or concept in your thesis.

The above strategies are not exhaustive nor are they only applicable to the introduction of your research proposal. They can be used to introduce any section of your thesis or any paper. Regardless of the strategy that you use to introduce your topic, remember that the key objective is to convince your reader that the issue is problematic and is worth investigating. A well developed statement of research problem will do the following:

- Contextualize the problem . This means highlighting what is already known and how it is problematic to the specific context in which you wish to study it. By highlighting what is already known, you can build on key facts (such as the prevalence and whether it has received attention in the past). Please note that this is not the literature review; you are simply fleshing out a few pertinent details to introduce the topic in a few sentences or a paragraph.

- Specify the problem by describing precisely what you plan to address. In other words, elaborate on what we need to know. For example, building on your contextualization of the problem, you can specify the problem with a statement such as: “There is an abundance of literature on international migration. In fact, the IOM (2018) estimates that there are close to 258 million international migrants globally, who contribute billions to the global economy. However, not much is known about the extent of intra-regional migration in the global south such as within the African continent. There is, hence, a pressing need to study this phenomenon in greater detail.”

- Highlight the relevance of the problem . This means explaining to the readers why we need to know this information, who will be affected, who will benefit?

- Outline the goal and objectives of the research.

- The goal of your research is what you hope to achieve by answering the research question. To write the goal of your research, go back to your research question and state the results you intend to obtain. For example, if your research question is “What effect does extended social media use have on female body images?”, the goal of your research could be stated as “The goal of this study is to identity the point at which social media use negatively impact female body images so that they can be informed about how to use it responsibly.

- The objectives of your study is a further elaboration on your goals i.e., details about the steps that you will take to achieve the goal. Based on the goal above, you probably will study incidents of depression among female social media users, changes in self-esteem and incidents of eating disorders. These could translate into objectives such as to: (1) compare the incidents of depression among female social media users based on length of use (2) assess changes in female social media users’ self esteem (3) determine if there are differences in the incidents of eating disorder among female social media users based on extent of use. Notice that in achieving those objectives, you will be able to reach the goal of answering your research question.

In summary, you should strive to have one goal for each research question. If your project has only one research question, one goal is sufficient. Your objectives are the pathways (or steps) that will get you to achieve the goal i.e., what will you need to do in order to answer the research question. Summarize the steps in no more than two or three objectives per goal.

Brief Literature Review

After the problem and rationale are introduced, the next step is to frame the problem within the academic discourse. This involves conducting a preliminary literature review covering, inter alia, the history of the phenomena itself and the scholarly theories and investigations that have attempted to understand it (Petrina, 2009). In elaborating on the history of the concepts and theories, you should also attempt to draw attention to the theories which will guide your own research (or which will be contested by your research). By foregrounding the major ways of perceiving the problem, you will then set the stage for your own methodology: the major concepts and tools you will use to investigate/interpret the problem.

While in graduate research proposals the literature review often composes a section of its own (Petrina, 2009), in undergraduate research this step can be incorporated into the introduction. However, you should avoid, as Wong (n.d.) writes, framing your research question “in the context of a general, rambling literature review,” where your research question “may appear trivial and uninteresting.” Try to respond to seminal papers in the literature and to identify clearly for your reader the key concepts in the literature that you will be discussing. Part of outlining the scholarly discussion should also focus on clarifying the boundaries of your topic. While making the significance concrete, try to hone in on select themes that your research will evaluate. This way, when you go to outline the methods you will use, the topic will have clearly defined boundaries and concerns. See chapter 5 for more guidance on how to construct an extended literature review.

Box 2. 1 – Tips for the Literature Review

- Summarize : The literature in your literature review is not going to be exhaustive but it should demonstrate that you have a good grasp on key debates and trends in the field

- Quality not quantity : Despite the fact that this is non-exhaustive, there is no magic number of sources that you need. Do not think in terms of how many sources are sufficient. Think about presenting a decent representation of key themes in the literature.