Scarcity in economics

Definition: Scarcity refers to resources being finite and limited. Scarcity means we have to decide how and what to produce from these limited resources. It means there is a constant opportunity cost involved in making economic decisions. Scarcity is one of the fundamental issues in economics.

Examples of scarcity

- Land – a shortage of fertile land for populations to grow food. For example, the desertification of the Sahara is causing a decline in land useful for farming in Sub-Saharan African countries.

- Water scarcity – Global warming and changing weather, has caused some parts of the world to become drier and rivers to dry up. This has led to a shortage of drinking water for both humans and animals.

- Labour shortages . In the post-war period, the UK experienced labour shortages – insufficient workers to fill jobs, such as bus drivers. In more recent years, shortages have been focused on particular skilled areas, such as nursing, doctors and engineers

- Health care shortages . In any health care system, there are limits on the available supply of doctors and hospital beds. This causes waiting lists for certain operations.

- Seasonal shortages. If there is a surge in demand for a popular Christmas present, it can cause temporary shortages as demand as greater than supply and it takes time to provide.

- Fixed supply of roads . Many city centres experience congestion – there is a shortage of road space compared to number of road users. There is a scarcity of available land to build new roads or railways.

How does the free market solve the problem of scarcity?

If we take a good like oil. The reserves of oil are limited; there is a scarcity of the raw material. As we use up oil reserves, the supply of oil will start to fall.

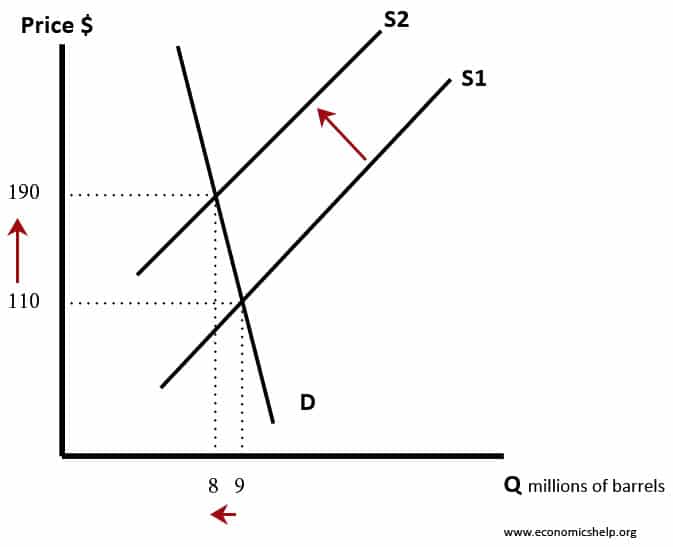

Diagram of fall in supply of oil

If there is a scarcity of a good the supply will be falling, and this causes the price to rise. In a free market, this rising price acts as a signal and therefore demand for the good falls (movement along the demand curve). Also, the higher price of the good provides incentives for firms to:

- Look for alternative sources of the good e.g. new supplies of oil from the Antarctic.

- Look for alternatives to oil, e.g. solar panel cars.

- If we were unable to find alternatives to oil, then we would have to respond by using less transport. People would cut back on transatlantic flights and make fewer trips.

Demand over time

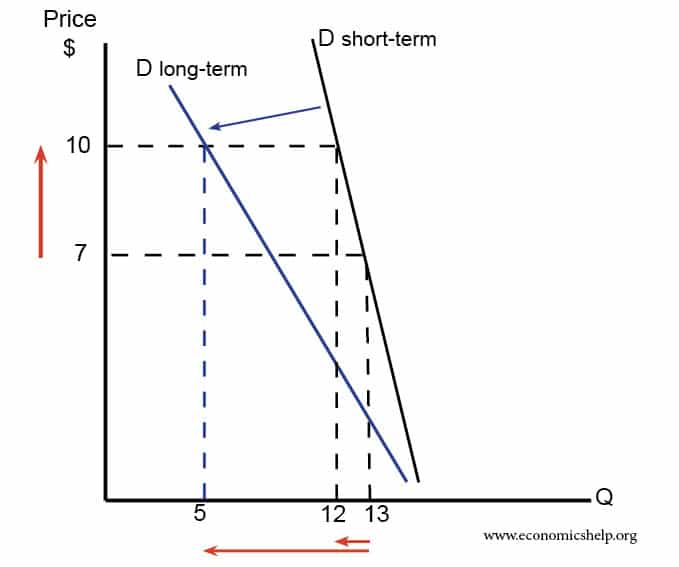

In the short-term, demand is price inelastic. People with petrol cars, need to keep buying petrol. However, over time, people may buy electric cars or bicycles, therefore, the demand for petrol falls. Demand is more price elastic over time.

Therefore, in a free market, there are incentives for the market mechanisms to deal with the issue of scarcity.

Causes of scarcity

Scarcity can be due to both

- Demand-induced scarcity

- Supply-induced scarcity

and a combination of the two. See more at: Causes of scarcity.

Scarcity and potential market failure

With scarcity, there is a potential for market failure. For example, firms may not think about the future until it is too late. Therefore, when the good becomes scarce, there might not be any practical alternative that has been developed.

Another problem with the free market is that since goods are rationed by price, there may be a danger that some people cannot afford to buy certain goods; they have limited income. Therefore, economics is also concerned with the redistribution of income to help everyone be able to afford necessities.

Another potential market failure is a scarcity of environmental resources. Decisions we take in this present generation may affect the future availability of resources for future generations. For example, the production of CO2 emissions lead to global warming, rising sea levels, and therefore, future generations will face less available land and a shortage of drinking water.

The problem is that the free market is not factoring in this impact on future resource availability. Production of CO2 has negative externalities, which worsen future scarcity.

Tragedy of the commons

The tragedy of the commons occurs when there is over-grazing of a particular land/field. It can occur in areas such as deep-sea fishing which cause loss of fish stocks. Again the free-market may fail to adequately deal with this scarce resource.

Further reading on Tragedy of the Commons

Quotas and scarcity

One solution to dealing with scarcity is to implement quotas on how much people can buy. An example of this is the rationing system that occurred in the Second World War. Because there was a scarcity of food, the government had strict limits on how much people could get. This was to ensure that even people with low incomes had access to food – a basic necessity.

A problem of quotas is that it can lead to a black market; for some goods, people are willing to pay high amounts to get extra food. Therefore, it can be difficult to police a rationing system. But, it was a necessary policy for the second world war.

Related pages

- Opportunity cost

- Production possibility frontiers

- Is economics irrelevant in the absence of scarcity?

- Dealing with food scarcity

12 thoughts on “Scarcity in economics”

- Pingback: Is Economics Irrelevant in Absence of Scarcity? | Economics Help

Good from what are you doing but you have to provide to us some of sample questions concerning the University level

l want to be explained further on scarcity as it is becoming hard topic for me to understand

When we even make a choice we have to forgo the other alternative.The alternative forgone in making am informed choice is also known as oppotunity

I really learned a lot in this website, thank you very much I appreciate

I want my text book explanation of social subject

Actually, I don’t understand about the entrepreneurship.. Can you please help me?.. I’m a senior high student for the upcoming school year..and We don’t have a actual class so please could you help me to understand this?😅

Thank you so much its clear

This makes some sense but the graphs just messed my head up pls help

I enjoyed the nature of information

The only “problem” with the free market is when it is interfered with. It is a natural process, by interfering with it you are indirectly interfering with nature. Everything on our planet is finite, everything has to be paid for. Every action has an equal and opposite reaction. The is no free lunch. Interfering with the free market is like kicking a can down the road, it may seem just and righteous in the instant, but it is by no means sustainable ultimately over time.

Thank you so much

Comments are closed.

Module 1: Economic Thinking

Understanding economics and scarcity, learning objectives.

- Describe scarcity and explain its economic impact

- Describe factors of production

Figure 1. Food, like the wheat shown here, is a scarce good because it exists in limited supply.

The resources that we value—time, money, labor, tools, land, and raw materials—exist in limited supply. There are simply never enough resources to meet all our needs and desires. This condition is known as scarcity.

At any moment in time, there is a finite amount of resources available. Even when the number of resources is very large, it’s limited. For example, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2016, the labor force in the United States contained more than 158 million workers—that’s a lot, but it’s not infinite. Similarly, the total area of the United States is 3,794,101 square miles—an impressive amount of acreage, but not endless. Because these resources are limited, so are the numbers of goods and services we can produce with them. Combine this with the fact that human wants seem to be virtually infinite, and you can see why scarcity is a problem.

Throughout the course, you will find these “Try It” boxes with questions to help you check your understanding and apply the concepts from the reading. Choose an answer, then select “check answer” to get feedback about how you did.

When faced with limited resources, we have to make choices. Again, economics is the study of how humans make choices under conditions of scarcity. These decisions can be made by individuals, families, businesses, or societies.

Let’s consider a few decisions that we make based on limited resources. Take the following:

1. What classes are you taking this term?

Are you the lucky student who is taking every class you wanted with your first-choice professor during the perfect time and at the ideal location? The odds are that you have probably had to make trade-offs on account of scarcity. There is a limited number of time slots each day for classes and only so many faculty available to teach them. Every faculty member can’t be assigned to every time slot. Only one class can be assigned to each classroom at a given time. This means that each student has to make trade-offs between the time slot, the instructor, and the class location.

2. Where do you live?

Think for a moment, if you had all the money in the world, where would you live? It’s probably not where you’re living today. You have probably made a housing decision based on scarcity. What location did you pick? Given limited time, you may have chosen to live close to work or school. Given the demand for housing, some locations are more expensive than others, though, and you may have chosen to spend more money for a convenient location or to spend less money for a place that leaves you spending more time on transportation. There is a limited amount of housing in any location, so you are forced to choose from what’s available at any time. Housing decisions always have to take into account what someone can afford. Individuals making decisions about where to live must deal with limitations of financial resources, available housing options, time, and often other restrictions created by builders, landlords, city planners, and government regulations.

Watch it: Scarcity and Choice

Throughout this course you’ll encounter a series of short videos that explain complex economic concepts in very simple terms. Take the time to watch them! They’ll help you master the basics and understand the readings (which tend to cover the same information in more depth).

As you watch the video, consider the following key points:

- Economics is the study of how humans make choices under conditions of scarcity.

- Scarcity exists when human wants for goods and services exceed the available supply.

- People make decisions in their own self-interest, weighing benefits and costs.

Problems of Scarcity

Every society, at every level, must make choices about how to use its resources. Families must decide whether to spend their money on a new car or a fancy vacation. Towns must choose whether to put more of the budget into police and fire protection or into the school system. Nations must decide whether to devote more funds to national defense or to protecting the environment. In most cases, there just isn’t enough money in the budget to do everything.

Economics helps us understand the decisions that individuals, families, businesses, or societies make, given the fact that there are never enough resources to address all needs and desires.

Economic Goods and Free Goods

Most goods (and services) are economic goods , i.e. they are scarce. Scarce goods are those for which the demand would be greater than the supply if their price were zero. Because of this shortage, economic goods have a positive price in the market. That is, consumers have to pay to get them.

What is an example of a good which is not scarce? Water in the ocean? Sand in the desert? Any good whose supply is greater than the demand if their price were zero is called a free good , since consumers can obtain all they want at no charge. We used to consider air a free good, but increasingly clean air is scarce.

Productive Resources

Having established that resources are limited, let’s take a closer look at what we mean when we talk about resources. There are four productive resources (resources have to be able to produce something), also called factors of production :

- Land: any natural resource, including actual land, but also trees, plants, livestock, wind, sun, water, etc.

- Econ omic capital: anything that’s manufactured in order to be used in the production of goods and services. Note the distinction between financial capital (which is not productive) and economic capital (which is). While money isn’t directly productive, the tools and machinery that it buys can be.

- Labor: any human service—physical or intellectual. Also referred to as human capital .

- Entrepreneurship : the ability of someone (an entrepreneur) to recognize a profit opportunity, organize the other factors of production, and accept risk.

Productive resources and factors of production are explained again in more detail in the following video:

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Revision and adaptation. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- What Is Economics, and Why Is It Important?. Authored by : OpenStax College. Provided by : Rice University. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:mdNAtxNF/What-Is-Economics-and-Why-Is-I . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]

- Kansas Summer Wheat and Storm Panorama. Authored by : James Watkins. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/23737778@N00/7115229223/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Episode 2: Scarcity and Choice. Authored by : Dr. Mary J. McGlasson. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yoVc_S_gd_0 . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- Episode 3: Resources. Authored by : Dr. Mary J. McGlasson. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0PgP0dXAGAE&feature=youtu.be . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is Scarcity?

Production and demand.

- Natural Resource Scarcity

Scarcity and the Market

The bottom line.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Group1805-3b9f749674f0434184ef75020339bd35.jpg)

Scarcity is an economic concept where individuals must allocate limited resources to satisfy their needs. Scarcity occurs when demand for a good or service is greater than availability. Scarcity affects the monetary value individuals place on goods and services.

Key Takeaways

- Scarcity is an economic concept where individuals must allocate limited resources to satisfy their needs.

- Scarcity limits the choices available to consumers in an economy.

- Some natural resources that are easily and widely accessible eventually prove scarce as they are depleted from overuse.

- Scarcity affects the monetary value individuals place on goods and services.

Investopedia / Mira Norian

If goods and services are abundant and unlimited, there is no need to make decisions about allocating resources. However, scarcity limits the choices available to consumers in an economy. Scarcity makes goods more valuable and sellers can set higher prices.

Scarcity also describes the relative availability of factors or production or economic inputs. Suppose producing a widget requires two labor inputs: workers and managers, with one manager required per 20 workers. The available labor pool consists of 20,000 workers and 5,000 managers. There are more available workers than managers. Yet, workers are a relatively scarce resource, since they're needed for a ratio of 20 per manager for production, but outnumber managers by a ratio of only 4 to 1 in the labor pool.

Societies face limitations when trying to increase supply. Production capacity, land available for use, time, and labor are all considerations. Another way to deal with scarcity is by reducing demand through quotas , rationing , or price caps .

Scarcity forces consumers to make choices that come with associated opportunity costs . Opportunity cost is the cost of what is given up, compared to the value of the alternative.

Natural Resource Scarcity

Abundant common resources over-consumed at zero cost at first often prove limited. Climate isn't a tangible asset and its value is hard to calculate, but the costs of climate change affect companies and societies. Air is free, but clean air has a cost in terms of the economic activity discouraged to prevent pollution for health and quality of life .

Some natural resources that may appear free because they are easily and widely accessible eventually prove scarce as they are depleted from overuse in a tragedy of the commons . Economists increasingly view a climate compatible with human welfare as scarce goods because of the cost of protecting them and place a price on them for a cost-benefit analysis .

Governments may require manufacturers and utilities to invest in pollution control equipment, or to adopt cleaner power sources. Governments and the regulated industries eventually pass costs to taxpayers and consumers.

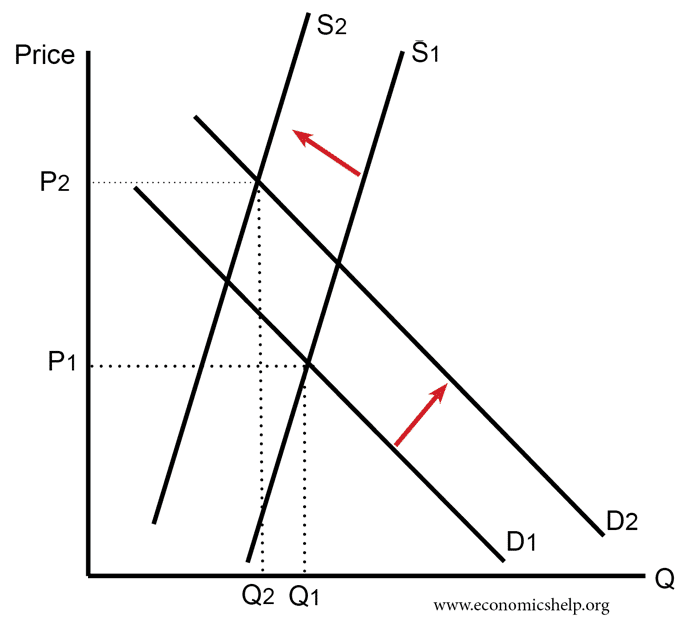

Scarcity may denote a change in a market equilibrium raising the price based on the law of supply and demand . In those instances, scarcity denotes a decrease over time in the supply of the product or commodity relative to demand. The growing scarcity reflected in the higher price required to attain a market equilibrium could be attributable to one or more of the following:

- Demand-induced scarcity reflects rising demand

- Supply-induced scarcity caused by diminished supply

- Structural scarcity attributable to mismanagement or inequality

Does Scarcity Mean Something Is Hard to Obtain?

Scarcity can explain a market shift to a higher price, compare the availability of economic inputs, or convey the opportunity cost in allocating limited resources. The definition of a market price is one at which supply equals demand, meaning all those willing to obtain the resource at a market price can do so. Scarcity can explain a market shift to a higher price, compare the availability of economic inputs, or convey the opportunity cost in allocating limited resources.

When Is Scarcity Intentionally Created?

This article is free to read and other content is easily reproduced intellectual property , including films and music, but may derive their scarcity from copyright protection . Inventors of new drugs and devices must secure patents to deter imitators. Many free goods may have an indirect or hidden cost .

How Does Monetary Policy Affect Scarcity?

In the U.S., the Federal Reserve controls the money supply. When governments print too much money, the value of the money decreases. Supply is high and money is less scarce. However, too much money in an economy can lead to inflation. Governments tend to keep the money supply relatively scarce through contractionary policy. The main contractionary policies employed by the United States include raising interest rates, increasing bank reserve requirements, and selling government securities.

When individuals must allocate limited resources to satisfy their needs, scarcity occurs. Scarcity limits the choices of consumers in an economy. Scarcity can affect a country's money supply, natural resources, available labor, and means of production.

ScienceDirect. " Population and Technological Change in Agriculture ."

SSRN. " Relative Prices and Climate Policy: How the Scarcity of Non-Market Goods Drives Policy Evaluation ."

Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit. “ Climate Economics - Costs and Benefits .”

Economics Help. " Scarcity in Economics ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/economics-source-67f961336a45429f890f74eb2d90cf0d.png)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

One of the defining features of economics is scarcity, which deals with how people satisfy unlimited wants and needs with limited resources. Scarcity affects the monetary value people place on goods and services and how governments and private firms decide to distribute resources.

Conservation, Earth Science, Social Studies

Water Truck in India.

Getting clean potable water in the hotter months of the year is a challenge for many New Delhi residents as the population grows and the clean water supply shrinks. Water trucks arrive to tens or even hundreds of people waiting for their daily supply of c

Photograph by Hindustan Times

Scarcity is one of the key concepts of economics . It means that the demand for a good or service is greater than the availability of the good or service. Therefore, scarcity can limit the choices available to the consumers who ultimately make up the economy . Scarcity is important for understanding how goods and services are valued. Things that are scarce, like gold, diamonds, or certain kinds of knowledge, are more valuable for being scarce because sellers of these goods and services can set higher prices. These sellers know that because more people want their good or service than there are goods and services available, they can find buyers at a higher cost.

Scarcity of goods and services is an important variable for economic models because it can affect the decisions made by consumers. For some people, the scarcity of a good or service means they cannot afford it. The economy of any place is made up of these choices by individuals and companies about what they can produce and afford.

The goods and services of any country are limited, which can lead to scarcity . Countries have different resources available to produce goods and services. These resources can be workers, government and private company investment, or raw materials (like trees or coal). Certain limits of scarcity can be balanced by taking resources from one area and using them somewhere else. Sellers like private companies or governments decide how the available resources are spread out. This is done by trying to strike a balance between what consumers need or want, what the government needs, and what will be an efficient use of resources to maximize profits . Countries also import resources from other countries, and export resources from their own.

Scarcity can be created on purpose. For example, governments control the printing of money, a valuable good. But, paper, cotton, and labor are all widely available across the world, so the things required to make money are not themselves scarce. If governments print too much money, the value of their money decreases, because it has become less scarce. When the supply of money in an economy is too high, it can lead to inflation . Inflation means the amount of money needed to buy a good or service increases—therefore money becomes less valuable, and the same amount of money can buy less over time than it could in the past. It is therefore in a country’s best interest to keep its paper money supply relatively scarce. However, sometimes inflation can help an economy . When money is less scarce, people can spend more, which triggers a rise in production. Low inflation can help an economy grow.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Manager

Program specialists, specialist, content production, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- Liberty Fund

- Adam Smith Works

- Law & Liberty

- Browse by Author

- Browse by Topic

- Browse by Date

- Search EconLog

- Latest Episodes

- Browse by Guest

- Browse by Category

- Browse Extras

- Search EconTalk

- Latest Articles

- Liberty Classics

- Search Articles

- Books by Date

- Books by Author

- Search Books

- Browse by Title

- Biographies

- Search Encyclopedia

- #ECONLIBREADS

- College Topics

- High School Topics

- Subscribe to QuickPicks

- Search Guides

- Search Videos

- Library of Law & Liberty

- Home /

ECONLIB Guides

Introduction

In economics, scarcity refers to limitations–limited goods or services, limited time, or limited abilities to achieve the desired ends. Life would be so much easier if everything were free! Why can’t I get what I want when I want it? Why does everything cost so much and take so much effort? Can’t the government, or at least the college or local town, or if not that, my parents just give it to me–or at least make a law so that if I want to buy pizza, there is a pizza shop nearby that has to sell me pizza at a dollar a slice?

That you can’t have everything you want the moment you want it is a fact of life. Figuring out how individuals, families, communities, and countries might best handle this to their benefit is fundamental to what economics is about.

You are probably used to thinking of natural resources such as titanium, oil, coal, gold, and diamonds as scarce. In fact, they are sometimes called “scarce resources” just to re-emphasize their limited availability. Everyone agrees natural resources are scarce because they take a lot of effort, money, time, or other resources to get, or because there seems to be a finite amount available.

But what constitutes a lot of effort, money, time, or other resources? Does it matter if something is finite if we can easily substitute something else? It all depends on your circumstances. Most people don’t think of water as scarce, but if you live in a desert, water is scarce. If you are a teenager or in college, iPhones or the hottest sneakers or the recognition of your peers or a person of interest are as scarce–as difficult to acquire–as gold. If you are running out of space on your hard drive but you can substitute cloud computing, is storage space scarce?

In fact, economists view everything people want, strive for, or can’t achieve effortlessly as scarce. For example,

Every time you turn on the tap and get fresh water, that fresh water is part of what economists deem as scarce. Instead of paying your water bill, you could instead hike down to the local river and fill your water bottle in the local stream or creek, as did your forbears only 100 years ago. That would involve your time, and even in the most pure of natural circumstances your worry about whether deer might have polluted the stream or creek with bacteria. Not to mention if you want to shower in clean water or water the summer vegetables you want to grow with clean water. The air we breathe and the sun that shines on us is free. But if the air we breathe or the sunlight we bask in are not as perfect or fresh or unpolluted as we envision, are you personally willing to pay more to make it so? If we make sweeping governmental, regulatory changes, are we sure that those changes are not major changes that might affect our friends or others on the earth badly? Or that won’t come back to bite us, even making pollution worse? Time is scarce. Every minute you spend reading this is a minute you could alternatively spend reading a novel, catching a baseball game, talking to your friends or family, or working at a soup kitchen. Every time you have to give up something to enjoy what you want, the thing you want is scarce.

Since to an economist, everything people desire or demand is probably scarce, your next question may be how you can analyze the costs and benefits . Or you may want to know how to supply those desirable goods and services. You may want to ask more about productive resources , including natural resources . If you are intrigued by why diamonds–which seem so frivolous–cost so much more than water–which seems so essential, you might want to skip to margins and thinking at the margin .

Definitions and Basics

Natural Resource , from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

The earth’s natural resources are finite, which means that if we use them continuously, we will eventually exhaust them….

In the News and Examples

They Clapped: Can Price-Gouging Laws Prohibit Scarcity? , by Michael Munger. Econlib, January 8, 2007. See also associated podcast,

Munger on Price Gouging , on EconTalk.

Hurricane “Fran” smashed into the North Carolina coastline at Cape Fear at about 8:30 pm, 5 September 1996. It was a category 3, with 120 mph winds, and enormous rain bands. It ran nearly due north, hitting the state capital of Raleigh about 3 am, and moving north and east out of the state by morning…. There were no generators, ice, or chain saws to be had, none. But that means that anyone who brought these commodities into the crippled city, and charged less than infinity, would be doing us a service….

Chris Anderson on Free , EconTalk podcast. May 12, 2008.

Chris Anderson talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about his next book project based on the idea that many delightful things in the world are increasingly free–internet-based email with infinite storage, on-line encyclopedias and even podcasts, to name just a few. Why is this trend happening? Is it restricted to the internet? Is there really any such thing as a free lunch? Is free a penny cheaper than a penny or a lot cheaper than that? The conversation also covers whether economics has anything to say about free….

Richard McKenzie on Prices , EconTalk podcast. June 23, 2008.

Richard McKenzie of the University California, Irvine and the author of Why Popcorn Costs So Much at the Movies and Other Pricing Puzzles, talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about a wide range of pricing puzzles. They discuss why Southern California experiences frequent water crises, why price falls after Christmas, why popcorn seems so expensive at the movies, and the economics of price discrimination….

Diane Coyle on the Soulful Science , EconTalk podcast.

Diane Coyle talks with host Russ Roberts about the ideas in her new book, The Soulful Science: What Economists Really Do and Why it Matters. The discussions starts with the issue of growth–measurement issues and what economists have learned and have yet to learn about why some nations grow faster than others and some don’t grow at all. Subsequent topics include happiness research, the politics and economics of inequality, the role of math in economics, and policy areas where economics has made the greatest contribution….

Daniel Botkin on Nature, the Environment and Global Warming , EconTalk podcast.

Daniel Botkin, ecologist and author, talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about how we think about our role as humans in the natural world, the dynamic nature of environmental reality and the implications for how we react to global warming….

A Little History: Primary Sources and References

Lionel Robbins , biography, from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

Robbins’ most famous book was An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science , one of the best-written prose pieces in economics. That book contains three main thoughts. First is Robbins’ famous all-encompassing definition of economics that is still used to define the subject today: “Economics is the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between given ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.”…

Who coined the phrase “the dismal science”? See The Secret History of the Dismal Science: Economics, Religion, and Race in the 19th Century , by David M. Levy and Sandra J. Peart. Econlib, January 22, 2001.

Everyone knows that economics is the dismal science. And almost everyone knows that it was given this description by Thomas Carlyle, who was inspired to coin the phrase by T. R. Malthus’s gloomy prediction that population would always grow faster than food, dooming mankind to unending poverty and hardship. While this story is well-known, it is also wrong, so wrong that it is hard to imagine a story that is farther from the truth. At the most trivial level, Carlyle’s target was not Malthus, but economists such as John Stuart Mill, who argued that it was institutions, not race, that explained why some nations were rich and others poor….

Advanced Resources

Is Economics All About Scarcity? , by Arnold Kling. Blog discussion on EconLog, January 17, 2007.

… I am two-handed on this issue. On the one hand, just because food, say, has become more abundant does not mean that we can ignore scarcity. At any moment in time, for a given state of know-how, the conventional definition of economics as dealing with the allocation of scarce resources among competing ends applies. On the other hand, some of the most interesting economic observations concern relative abundance. Look at our standard of living compared to 100 years ago. Look at South Korea compared with North Korea. Robert Lucas famously said that “The consequences for human welfare involved in questions like these are simply staggering: Once one starts to think about them it is hard to think of anything else.”…

Related Topics

Incentives Cost-Benefit Analysis Efficiency Productive Resources Property Rights What is Economics?

Introduction to Choice in a World of Scarcity

Chapter objectives.

In this chapter, you will learn about:

- How Individuals Make Choices Based on Their Budget Constraint

- The Production Possibilities Frontier and Social Choices

- Confronting Objections to the Economic Approach

Bring It Home

Choices ... to what degree.

Does your level of education impact earning? Let’s look at some data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). In 2020, among full-time wage and salary workers, median weekly earnings for those with a master’s degree were $1,545. Multiply this average by 52 weeks, and you get average annual earnings of $80,340. Compare that to the median weekly earnings for full-time workers aged 25 and over with just a bachelor’s degree: $1,305 weekly and $67,860 a year. What about those with no higher than a high school diploma in 2020? They earn an average of just $781 weekly and $40,612 over 12 months. In other words, data from the BLS indicates that receiving a bachelor’s degree boosts earnings by 67% over what workers would have earned if they only obtained a high school diploma, and a master’s degree yields average earnings that are nearly double those of workers with a high school diploma.

Given these statistics, we might expect many people to choose to go to college and at least earn a bachelor’s degree. Assuming that people want to improve their material well-being, it seems like they would make those choices that provide them with the greatest opportunity to consume goods and services. As it turns out, the analysis is not nearly as simple as this. In fact, in 2019, the BLS reported that while just over 90% of the population aged 25 and over in the United States had a high school diploma, only 36% of those aged 25 and over had a bachelor's or higher degree, and only 13.5% had earned a master's or higher degree.

This brings us to the subject of this chapter: why people make the choices they make and how economists explain those choices.

You will learn quickly when you examine the relationship between economics and scarcity that choices involve tradeoffs. Every choice has a cost.

In 1968, the Rolling Stones recorded “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” Economists chuckled, because they had been singing a similar tune for decades. English economist Lionel Robbins (1898–1984), in his Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science in 1932, described not always getting what you want in this way:

The time at our disposal is limited. There are only twenty-four hours in the day. We have to choose between the different uses to which they may be put. ... Everywhere we turn, if we choose one thing we must relinquish others which, in different circumstances, we would wish not to have relinquished. Scarcity of means to satisfy given ends is an almost ubiquitous condition of human nature.

Because people live in a world of scarcity, they cannot have all the time, money, possessions, and experiences they wish. Neither can society.

This chapter will continue our discussion of scarcity and the economic way of thinking by first introducing three critical concepts: opportunity cost, marginal decision making, and diminishing returns. Later, it will consider whether the economic way of thinking accurately describes either how we make choices and how we should make them.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Steven A. Greenlaw, David Shapiro, Daniel MacDonald

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Economics 3e

- Publication date: Dec 14, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/2-introduction-to-choice-in-a-world-of-scarcity

© Jan 23, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Scarcity in today´s consumer markets: scoping the research landscape by author keywords

- Open access

- Published: 29 September 2022

- Volume 74 , pages 93–120, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Haoye Sun 1 &

- Thorsten Teichert ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2044-742X 1

5423 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

Scarcity refers to not having enough of what one needs. This phenomenon has shaped individuals´ life since ancient times, nowadays ranging from daily-life scarcity cues in shopping scenarios to the planet’s resources scarcity to meet the world´s consumer demand. Because of this ubiquity of scarcity, the topic has been attracting attention from scholars and practitioners in different areas. Studies regarding scarcity were conducted across disciplines, based on different assumptions, and focused on distinct study subjects. A lack of mainstream about this topic hindered the convergence of core ideas among different schools of thought. In this article, we take an integrative socio-economic perspective to join diverse findings on scarcity affecting consumer markets, identify topic-specific research questions still to be answered, and provide suggestions for future and integrative research opportunities. A systematic review based on author keywords from 855 publications analyzing scarcity affecting business-consumer interactions serves as a database. Exploratory factor analyses based on author keywords identify shared patterns within and linkages across discourses stemming from various disciplines and theories. Results differentiate distinct research foci in the consumer behavior, socio-political, and other disciplinary research realms. A mapping of these research themes identifies the scarcity-related interplay among consumers, producers, and other stakeholders. Findings point out research directions for future studies at both the research realm level and the interdisciplinary level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Tighter nets for smaller fishes? Mapping the development of statistical practices in consumer research between 2008 and 2020

Antonia Krefeld-Schwalb & Benjamin Scheibehenne

Research on country-of-origin perceptions: review, critical assessment, and the path forward

Saeed Samiee, Leonidas C. Leonidou, … Bilge Aykol

The effects of scarcity on consumer decision journeys

Rebecca Hamilton, Debora Thompson, … Meng Zhu

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Scarcity refers to basic limitations in economic transactions resulting from the gap between resource availability and individuals’ needs (Cannon et al. 2019 ). The notion of “resource” covers a wide range of forms, including commodities, services, profits, energy, water, time, etc. (Goldsmith et al. 2021 ; Hamilton et al. 2019 ). It is undeniable that nowadays more individuals in the world have enough material, emotional as well as spiritual resources to satisfy their living needs and development desires. However, even in times of material abundance in the Western hemisphere, scarcity is not an outdated topic for researchers and practitioners. If we look back on our online/offline shopping experience, scarcity appeals such as “limited edition”, “last chance”, and “max 2 products per consumer” will always pop into our minds. Global events also remind us of the universality of scarcity and its impact on consumers and society (Hamilton et al. 2019 ). Economic development and even recovery after the 2007–2009 global financial crisis are constrained because of the unbalance between consumers´ resource demands and the scarcity of resources supply (Brown et al. 2014 ). Recently, the Covid-19 pandemic has led to the manifestations of various and unexpected forms of scarcity in consumer markets (Hamilton 2021 ), such as the scarcity of grocery products (Omar et al. 2021 ), water scarcity (Boretti 2020 ), as well as the scarcity of operational resources and capabilities (Shaheen et al. 2022 ). The scarcity of the above-mentioned resources jointly builds up a society with scarcity and even puts people in a scarcity mindset. All those examples highlight the ubiquity and multiformity of scarcity, making this concept an umbrella framework for socio-economic limitations in today´s consumer markets.

Scarcity causes difficult trade-off situations for consumers, marketers, and policy makers: how to effectively allocate the scarce resources to meet needs (Shi et al. 2020 ). Scarcity is thereby a fundamental proposition of classic economic theory, which states that economic actors need to treat resources as limited. As a basic economic problem, scarcity attracts researchers to optimize resource planning using mathematical and modeling methods; this provides strategic orientations. Meanwhile, psychologists suggest that scarcity is not a ubiquitous manifestation in reality but a situated phenomenon perceived by economic actors. More specifically, psychological studies show that individuals tend to think and behave differently based on the perceived scarcity of resources (O’Donnell et al. 2021 ; Shah et al. 2015 ); this creates business opportunities (Shi et al. 2020 ). The concept of scarcity has been linked to a wide range of socio-economic research subjects in consumer markets, such as consumer responses (Hamilton et al. 2019 ), revenue management (Heo et al. 2013 ), supply chain management (Fleischmann et al. 2020 ), sustainable consumption (Waris and Hameed 2020 ), corporate strategy (Zhou et al. 2007 ), and policy-making (Quesnel et al. 2019 ). Such an advance in scientific knowledge across a wide variety of disciplines generally motivates the need for evaluation studies assessing interdisciplinary scientific research (Wagner et al. 2011 ).

The general understanding of scarcity is that the phenomenon contains different dimensions based on different resource conditions (Datta and Mullainathan 2014 ; Fan et al. 2019 ). In a recent publication focused on product scarcity, Shi et al. ( 2020 ) recognized a variety of scarcity phenomena, including: physical product scarcity, service product scarcity, natural resources scarcity, the scarcity of managerial resources, as well as the scarcity of psychological resources. There is however a lack of studies that capture individuals’ experiences of scarcity across multiple domains (De Sousa et al. ( 2018 ). Even review studies so far aggregated empirical findings about single scarcity dimensions, e.g. on the impact of product scarcity on consumer responses (Hamilton et al. 2019 ; Shi et al. 2020 ), on supply chain management in the era of natural resource scarcity (Kalaitzi et al. 2018 ), as well as on scarcity of time and mental resources in the healthy diet field (Jabs and Devine 2006 ).

We argue a broader perspective is needed to investigate multiple as well as interdisciplinary dimensions of scarcity and their linkages. Focused studies cannot offer a comprehensive framework that captures various aspects of scarcity with all-embracing breadth, let alone can they reveal interconnections of scarcity dimensions and their core concepts across research themes and disciplines. From the perspective of knowledge integration, critical questions can better be answered from a more holistic perspective, and the diffusion of discoveries can be more widely promoted across different research fields (Aboelela et al. 2007 ). Accordingly, the current paper seeks to link different dimensions of scarcity in consumer markets to provide a systematic review regarding the socio-economics of the umbrella concept of scarcity. Specifically, this paper aims (1) to identify the main existing research streams in the field of socio-economics that address the scarcity of different resource types in consumer markets; (2) to integrate the main findings of these research streams, and categorize them into underlying research realms; (3) to point out future research directions for each research realm; (4) to sketch possibilities of transferring ideas and methods across the identified research realms.

2 Methodology

Informetrics provides a set of tools to systematically analyze research and its development over time (Kuntner and Teichert 2016 ; Wagner et al. 2011 ). It uses meta-information provided within academic publications to gain insights at an aggregate level of research fields. Typically, co-citation analyses are conducted to map the research landscape of a scientific discipline (Acedo and Casillas 2005 ; Frerichs and Teichert 2021 ). This approach bases on the idea that single publications are built upon each other, such that joint references indicate an overlap of underlying research topics. This mode of analysis works well within a scientific discipline, where there are shared protagonists and idea-providers that are jointly been cited by following articles. However, co-citation analysis can fail in mapping an interdisciplinary landscape. Here, the same topic can be addressed from complementary angles, while referring to different protagonists' works. Thus, a lack of co-citations need not imply different topics but may hint at divergent lenses applied in its analysis.

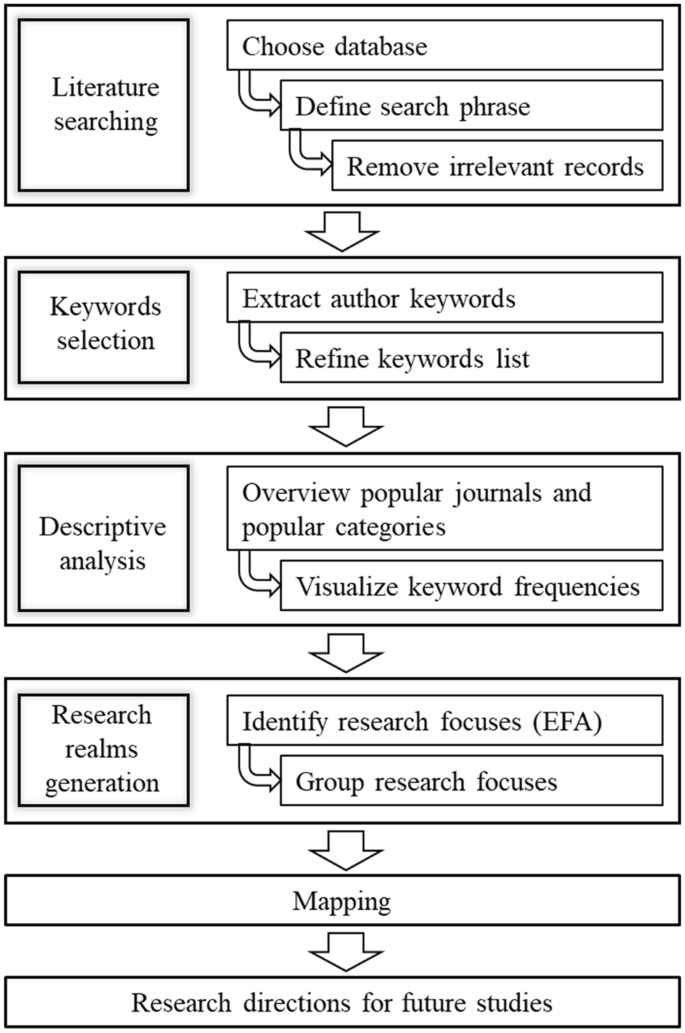

Given the highly heterogeneous and interdisciplinary nature of the scarcity discourse, our paper deviates from common co-citation analysis and instead carries out an informetric analysis based on author keywords. Author keywords refer to the list of topic-specific words hand-picked by the authors to describe the articles´ issues (Lu et al. 2021 ). These keywords are generally chosen such that they provide general information about the papers´ topics that are been investigated. This holds as author keywords determine the publication success, the paper’s attractiveness to potential readers, and even its dissemination to certain fields. Therefore, authors mostly include informative, most relevant, and refined words with standardized academic expression as keywords (Uddin and Khan 2016 ). As important entities of meta-data, author keywords play a significant role in bibliographic analysis to clarify scientific knowledge structures, identify subject hotspots, and detect research trends (Lu et al. 2021 , 2020 ). Thus, in this paper, we identify research streams based on author keywords. Figure 1 shows the framework of the paper.

Research framework of the current study

2.1 Data collection

Following standard practice in scientometric research (Chen et al. 2019 ; Shi et al. 2020 ), the internationally leading database of Web of Science (WoS) is used to capture the relevant literature. WoS is known to index the influential literature in different fields, thus is regarded as the high-quality database WOS for bibliometric analysis (Shi et al. 2020 ). Both the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and the Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) were selected as they jointly represent an especially broad spectrum of the international literature in social sciences (Wörfel 2019 ). Following the procedure applied by previous articles executing author keywords analyses (Farooq et al. 2018 ; Keramatfar and Amirkhani 2019 ), we separated an article search phase from its analysis phase.

In the search phase, a search term was broadly defined to identify relevant articles using based on topics (referred to in either article title, author keywords, or abstract). As stated in the first section, scarcity has been related to various resources in different disciplines. In this paper, we aim to extract the dominant resource types from the existing literature on resource scarcity in each discipline. Thus, we didn’t include the expressions that specify the resource types (e.g., financial dissatisfaction, time pressure, budget contraction, etc.) in our search term. Instead, the noun “scarcity” was used as an elementary search phrase as it constitutes the shared terminological expression used in academic articles (Shi et al. 2020 ). This search phrase was combined by AND-conditions with additional search phrases relating the topic to issues of consumer markets instead of an engineering or technical angle. For this purpose, we added a second group of search phrases relevant to the perspective of consumers (i.e. consumer* OR customer*). Note that consumers in the service sector of tourism are often labelled by different nouns (Shi et al. 2020 ; Suri et al. 2007 ), thus we added tourist-related synonyms “OR tourist* OR traveler* OR traveller* OR visitor*” into the second part of the search term.

To rule out the irrelevant and increase the data quality, the search results were restricted to peer-reviewed publications with the document types as “article”, and language as “English” (Frerichs and Teichert 2021 ). In particular, irrelevant articles with the expressions of “scarcity of research/ data/ study” were excluded by applying the additional exclusion criteria “NOT scarcity of NEAR/1 research”, “NOT scarcity of NEAR/1 data”, and “NOT scarcity of NEAR/1 stud*”. The refined hit list was exported in August 2021, consisting of 855 articles about scarcity research with the micro-level socio-economic background.

2.2 Data analysis

The data analysis part contains multiple stages. As a first step, descriptive statistics inform about the scope of selected articles and the author keywords used. By doing so, we obtain an initial picture of the interdisciplinary fields and their respective research focuses. Subsequently, a factor analysis is performed to narrow down the overwhelming information derived from hundreds of author keywords to a limited set of underlying research streams. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) based on author keywords was carried out using the software IBM SPSS Statistics 25. EFA is an established method used to analyze interdependencies among multitudes of variables (i.e., author keywords in our paper) and to derive factors that can capture most of the information of the original variables.

These factors were interpreted as single research streams as follows. Factor loadings (FL) of single keywords inform about the keyword´s usage in a single research stream, i.e. how representative a keyword is for an identified factor (Kuntner & Teichert, 2016 ). Thus, research streams were characterized by their specific combinations of keywords. To further describe the factors, representative articles were identified based on their usage of these keywords. For each factor, the articles with an especially high absolute and relative number of referenced keywords were identified. A manual inspection of these articles served to describe exemplary works located within the research stream. Joining this bottom-up perspective of referencing individual publications with the top-down perspective of keyword statistics helped us contextualize author keywords and describe their common underlying research streams.

3.1 Descriptive analysis

The identified 855 articles were published in a huge amount of 500 different journals, distributed across 100 Web of Science Categories. Table 1 illustrates the Top 10 research categories and journals. This confirms a high interdisciplinary, but also reveals a highly dispersed discourse, as few journals contain more than ten publications related to the research topic. Further descriptive analysis across categories indicated that leading journals in environmental sciences (such as Water Research, Journal of Cleaner Production) and business & management (such as Journal of Consumer Psychology, Journal of Business Research) fields have been paying constant attention to scarcity research.

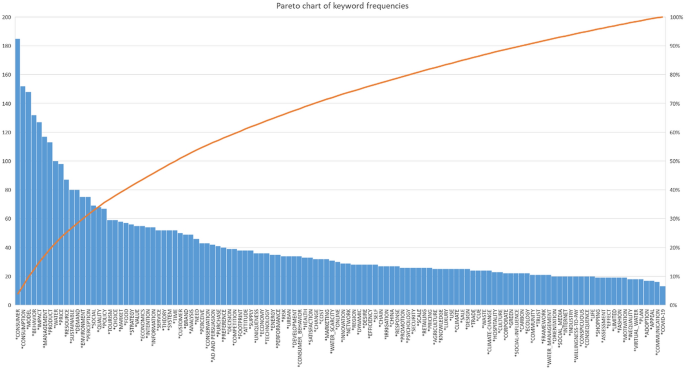

This particular breadth of research works is further illustrated by an analysis of keywords used by the 855 articles. A total of 120 different keywords were identified after word-stemming and cleaning. These keywords also exhibit a high dispersion, as visualized by the low concavity of the Pareto chart in Fig. 2 . No single keywords can be identified that are shared across the articles. Even the search-inherent concepts of “consumer” and “consumption” were referenced as author keywords only by a minority of identified articles (22% or 18%), suggesting a more distinct publication focus. Together, this initial inspection of publication metadata shows that standard differentiations by research categories (e.g. environmental sciences versus business & management) are insufficient to characterize the entire socio-economic discourse on consumer market scarcity. Thus, a sophisticated approach of statistical categorization is needed to systematically structure the research field.

Pareto chart of keyword frequencies

3.2 Overview on factor analysis results

A factor analysis is executed to group keywords together based on their co-occurrences. Keywords within one factor are then more likely to co-occur than keywords of different factors. Thus, the keywords assigned to each factor (based on their factor loadings) manifest the key contents of this single research stream. For example, the first factor that captures 18% of the keyword co-occurrence variance is characterized by keywords such as “uniqueness, desire, limited, luxury, social” which indicates purchase-enhancing product scarcity cues. These initial impressions are validated in the following sections by an in-depth analysis of publications belonging to this factor.

Ten factors were extracted by factor analysis to explain 50.03% of the variance in total. Eigenvalue and variance explanation of each factor are presented on the right-hand side of Table 2 . Consistent with previous studies in socio-economics (Nooteboom et al. 1997 ), a cut-off point at the FL value of 0.3 was applied to relate single keywords to their research streams. Table 2 shows the representative keywords under each factor (Table S1 provides the complete list of keywords in each factor). Factor numbers indicate the relative prominence of the identified research stream, measured by factors´ explained variance.

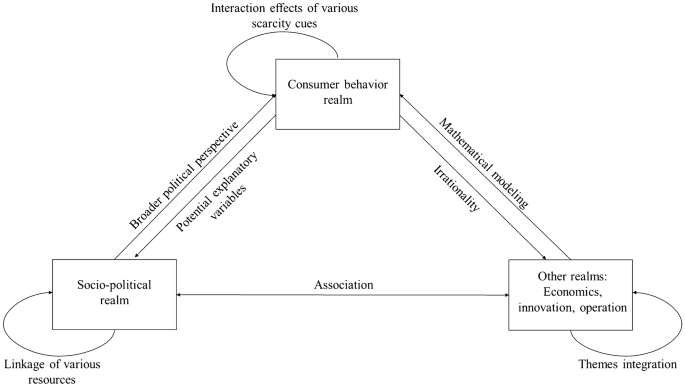

To reduce reading complexity, the ten identified research streams are grouped into three overarching realms (subheaders in Table 2 ). This grouping is based on a robust analysis of between-factor linkages. Hereto, pairwise correlations between keywords belonging to each two different factors are calculated. In Table 3 , the negative correlation coefficients indicate that the more author keywords belong to one factor, the less likely they belong to other factors. In other words, the correlation coefficients reflect the possibility of coexistence of articles´ factor belongingness. According to the results shown in Table 3 , we grouped the factors with the smallest conflicts (i.e., with the correlation coefficients near zero), resulting in three main research realms (marked with green lines in Table 3 ). This grouping of research streams (factors) into three overarching research realms is used in the following to arrange the discussion of single research streams. Please note that we nonetheless keep the factor numberings from factor1 to factor10 based on their decreased variance explained.

3.3 Consumer behavior research realm: a two-sided view and scarcity

Studies in consumer behavior often assume that consumers have adequate resources to purchase the products that can meet their consumption goals (Hamilton et al. 2019 ). However, many consumers experience a scarcity of products/services and/or a scarcity of process resources needed to conduct purchase behaviors (e.g., money and time) (Wang et al. 2021a , b ). Intuitively, experiencing insufficiency of what one wants to get is detrimental (Huijsmans et al. 2019 ), since a failed purchase caused by scarcity restricts consumers’ desire satisfaction (Biraglia et al. 2021 ). Interestingly, scarcity has also been found to increase consumers’ expectations for scarce products/services, and consequently prompt consumption (Aggarwal et al. 2011 ; Urbina et al. 2021 ). These findings seem to contradict each other at first glance, but their inconsistencies can be reconciled by consumers’ attributions of scarcity (Peterson et al. 2020 ).

In the consumer behavior research realm, we will talk about product scarcity and service scarcity in the retailing and service industries, respectively. Moreover, we will provide an in-depth understanding of the positive and negative effects of scarcity cues on consumer responses, and further explain the underlying mechanism for the two opposite effects.

3.3.1 Research stream (F1) on “purchase-enhancing product scarcity cues”

Scarcity cues in this research stream relate to the positive effects of the restricted availability of products or services. Such scarcity cues have been found to positively affect consumer responses, including shaping positive attitudes towards scarce products/brands, purchase intention, and willingness to pay/purchase. Following this line, previous studies confirmed a persuasive effect of scarcity appeals on consumer behaviors (Stock and Balachander 2005 ). Moreover, scarcity cues motivate non-rational consumer responses, such as luxury experiences seeking and impulsive purchases. That is because scarcity cues can lead to the conclusion of the rarity and uniqueness of products or brands (Chae et al. 2020 ). Limited-edition products can also address consumers’ desire for uniqueness (Urbina et al. 2021 ), since consuming unique products is an effective means to express consumers’ uniqueness (Bennett and Kottasz 2013 ). More importantly, scarcity serves as a differentiator of social class and social status (Bozkurt and Gligor 2019 ). Accordingly, consumers’ social-related characteristics (e.g., power state, social rejection vs. acceptance, social pressure, wealth) can moderate their reactions to scarcity cues (Bozkurt and Gligor 2019 ; Kim 2018 ; Song et al. 2021 ).

3.3.2 Research stream (F3) on “dysfunctional effects of product scarcity on consumer behavior”

This research stream complements the effects analysis of product scarcity on consumer behavior by addressing its possible negative effects. In general, scarcity messages provide urgency information to consumers, which consequently leads to a shorter deliberation and higher purchase amount, higher evaluation, as well as greater satisfaction with the scarce products (Aggarwal et al. 2011 ). Therefore, one could say scarcity is a “powerful weapon” in marketing. However, scarcity can be accompanied by “darkness” (e.g., negative affect or stress) (Huijsmans et al. 2019 ), and can even lead to negative perceptions of the scarce products and their sellers (Brannon and Brock 2001 ). As a spontaneous reaction, scarcity messages can cause negative physiological reactions. For instance, Book et al. ( 2001 ) observed the connection between scarcity promotions and testosterone levels, which indicates consumers’ aggressive reactions (Kristofferson et al. 2017 ).

Scarcity information may also cause a negative image of scarce products or their sellers. When consumers attribute the products’ scarcity information to “demand”, they tend to perceive the products to be unique (Urbina et al. 2021 ) and of better quality (Parker and Lehmann 2011 ). However, scarcity messages can also be interpreted as supply-side problems (e.g., stock-out), that evoke negative consequences, for example, lower ratings of the sellers, choice shift, as well as cancelation of purchases (Anderson et al. 2006 ; Sloot et al. 2005 ).

In summary, the framing of a product-related scarcity message can evoke completely different psychological processing and behavioral responses. Recent empirical studies provide interesting insights in this regard. Compared with supply-driven scarcity messages, such as “out-of-stock” and “unavailable”, demand-driven scarcity messages (e.g., “sold out”) lead to few negative responses to products and sellers (Kim and Lennon 2011 ; Peterson et al. 2020 ). Nevertheless, when consumers attribute scarcity as the result of accidental or non-market forces, neither positive nor negative effects on consumers’ responses are observed (Parker and Lehmann 2011 ).

3.3.3 Research stream (F5) on “scarcity issues in the (broader) consumption context”

In the previous sections, we summarized findings regarding how product scarcity influences consumers’ responses (i.e., attitudes, intentions, and behavior). Another research stream investigates consumers’ responses when facing scarcity in the broader consumption context. Two distinct themes were addressed under this umbrella, time and resource scarcity. A long tradition of research investigated causal relationships between time scarcity and impulsive and dysfunctional consumer behavior. Specifically, time pressure was found to trigger consumers’ impulsiveness, which increases their likelihood of eating ready-to-eat food without thinking about the nutritional ingredient and the following health consequences (Celnik et al. 2012 ; Machín et al. 2018 ; Sarmugam and Worsley 2015 ). More recently, the scarcity of resources (e.g., water, fuel) attracted more attention from researchers. A series of studies tried to shed light on consumers’ purchasing intention/behavior of sustainable products. In these studies, ecological knowledge and awareness of scarcity are found to be the main drivers of green consumption (Waris and Hameed 2020 ).

3.3.4 Research stream (F6) on “managing scarcity in the service industries”

Previous research streams have already covered different dimensions of scarcity based on different resource conditions in retailing. The research stream identified by factor 6 discusses the concept of scarcity in the service industry. Research addresses both positive effects of scarcity on consumer perceptions as well as negative supply-side scarcity effects.

Similar to retailing context, scarcity information may also act as a cue driving consumption in the service industry. The scarcity of specific service offerings, which is regarded as the manifestation of rarity, is confirmed to have a positive impact on customer satisfaction (Moulard et al. 2021 ). As an example, Kovács et al. ( 2014 ) report higher valuations when services were offered by distinctive independent restaurants instead of standardized chain restaurants.

Service industries have their specific characteristics (Le et al. 2019 ). Unlike product industries with relatively predictable demand and considerable capacity flexibility, service industries face the issue of step-fixed physical capacity (at least over the short term), together with highly unpredictable time-variable demand patterns. This leads to e.g. a surplus seating capacity during low hours and insufficient seating capacity during peak hours (McGill and Van Ryzin 1999 ). Service providers balance fluctuating demand and revenues by employing revenue management (RM) tools, such as dynamic pricing strategy and the control of the length of staying strategy (Heo et al. 2013 ; Lee et al. 2021 ). However, customers’ attributions of scarcity may lead to different reactions to various RM tools, and further influence customer satisfaction. When scarcity is attributed to high demand, customers enhance price appreciation. As a result, they are more likely to accept the dynamic pricing strategy. However, when scarcity is caused by “control of the length of staying strategy”, customers feel disrespected (Lee et al. 2021 ), which consequently leads to low customer satisfaction (Guillet and Mohammed 2015 ; Lindenmeier and Tscheulin 2008 ).

3.4 Socio-political research realm: resource scarcity in the water-energy-food security nexus

Scarcity in consumer markets is addressed in the socio-political research realm from the perspective of scarce material resources. Given the growing societal demand for physical resources, the whole world is facing an intractable scarcity issue (Steffen et al. 2015 ), that is, the recourse demand is going beyond the planetary boundaries, equity, and inclusivity (Rockström et al. 2009 ). Research works pursue a science-based paradigm to resolve the conflicts between human beings’ development needs and the planet’s resource scarcity. Specifically, the water-energy-food (WEF) security nexus emphasizes the scarcity of water, energy, and food resources, together with their intricate interrelationships (Hoff 2011 ). Researchers take a series of socio-political perspectives (such as political economy, environmental sustainability, and human development), to highlight their independencies and synergies of water, energy, and food resource sectors (Obersteiner et al. 2016 ; White et al. 2018 ). By doing so, scholars aim to optimize policy planning that negotiates the trade-off between global societal development and the ecosystem’s resilience maintenance. This section focuses on the natural resources scarcity dimension, and discusses each sector of the water-energy-food (WEF) security nexus, together with the identified interdependencies among the three sectors.

3.4.1 Research stream (F2) on “managing water scarcity”

Water is a scarce natural resource that is closely related to climate change and the future of human beings (Molden and Sakthivadivel 1999 ). Given the important role of water and its scarcity, researchers focus on water conservation strategies, so as to optimize water supply portfolios (Fraga et al. 2017 ). Well-known strategies such as financial incentives and political mandates fail to encourage water conservation in water-consumption scenarios (Zeff et al. 2020 ). Therefore, researchers aim to provide solutions for water management from the supply-side and demand-side.

Among different strategies for dealing with water scarcity, irrigation attracts significant attention from previous studies. Note that irrigation water is demanded not only in the agricultural sector (Pérez Blanco and Thaler 2014 ), but also in the urban sector (Hof and Blázquez-Salom 2015 ; Quesnel and Ajami 2019 ). Large landscape irrigation (with non-residential purposes) also accounts for a significant volume of water consumption (Morales and Heaney 2016 ). As a result, non-residential irrigation consumers become the research focus of recent publications. Quesnel and Ajami ( 2019 ) carried out a study in this regard. In this study, they investigate the dynamic water demand for non-residential irrigation consumers in the drought region; and find that policies help prompt long-term (e.g., yearly) water conservation behavior, but short-term (e.g., weekly) actions cannot be explained by political practices. Relatedly, Quesnel et al. ( 2019 ) compare the water use behavior of consumers with potable vs. recycled water. Results reveal that potable and recycled water consumers show the same demand pattern despite the different policies and pricing tactics.

3.4.2 Research stream (F4) on “footprint as a flow indicator of scarce resources”

Measuring resources consumption is the first step to guarantee appropriate utilization of the “planet’s assets”, so that the issue of resources scarcity can be alleviated (Qiang and Jian 2020 ). Taking water consumption as an example, scholars find that the final products only contain a limited fraction of water compared to the total volume of water used for the whole production process (namely, virtual water) (Allan 1997 ). With analogy to water consumption, the application of the “virtual” concept is expanded to various resources which are used for products and services production (White et al. 2018 ). To track both direct and indirect resources consumption, the notion of the footprint is introduced. Footprint assesses the total volume of a resource that is consumed during the production process of the goods and services consumed by various groups: individuals, households, companies, regions, or countries; within its spatial boundaries and embodied within its imports (Daniels et al. 2011 ). Using the input–output analysis, scholars calculate a variety of footprints, including water (Weinzettel and Pfister 2019 ), energy (Wang et al. 2020 , 2019 ; Yu et al. 2018 ), and food (White et al. 2018 ) embodied at the international (Weinzettel and Pfister 2019 ), domestic (Wang et al. 2019 ), and (multi) regional levels (Wang et al. 2020 ; White et al. 2018 ). Based on the findings, decision-makers can formulate policies to rationally exploit, trade, and transport natural resources.

3.4.3 Research stream (F10) on “scarcity and food security"

Food security as a multidimensional concept relates to different types of scarcity. Food security includes three dimensions: availability (ability to provide an adequate supply of food), accessibility (ability to acquire enough food), and utilization (ability to absorb nutrients contained in the food that is eaten) (FAO, 1996), which are linked to supply-side food scarcity, scarcity of food access, and scarce nutrition support, respectively. Similarly, Beer ( 2013 ) categorizes the multiple dimensions of food security into two types. The first one is production-oriented food security, referring to the quantum of food available to people. While the second type is consumption-oriented security, representing the concerns about food access, health, and equity. Following the same line, risk management addresses the whole process from food production to food consumption.

Some studies specifically identified the risks of phosphorus scarcity to different stakeholders along the entire supply chain, ranging from environmental and management risks faced by food producers and traders to market-related risks encountered by food consumers (Cordell and Neset 2014 ; Cordell et al. 2015 ). Beer ( 2013 ) discusses the risk derived from uncertainty, scarcity, and value conflict in terms of both food production and food consumption. Other studies focus on only one sub-dimension of food security. For example, Wang et al. ( 2021a , b ) explored the combined impact of risk perception and the access dimension of food security status on food consumption behavior during the Covid-19 pandemic. In sum, all these works address food-related scarcity issues to specific aspects along the supply chain of food production, distribution, and consumption.

3.5 Other research realms

In previous sessions, we had a close look at the two main research realms of scarcity-related studies, namely, the consumer behavior research realm, and the socio-political research realm. Although the above-mentioned research realms can cover the majority of research topics, other dimensions of scarcity in consumer markets are also addressed from various other research realms, which can be summarized into three perspectives: economics, innovation, and operations management.

3.5.1 Competition effects of scarcity (F7)

The scarcity of managerial resources and capabilities leads to the competing interests of stakeholders in a business network (Greenley and Foxall 1996 ; Zhou et al. 2007 ). Studies talk about the conflicts between different stakeholders, and guide corporates to allocate scarce resources and managerial capabilities efficiently (Greenley and Foxall 1996 ). They emphasize the role of strategizing to address scarcity issues in competitive settings. Zhou et al. ( 2007 ) suggest that competitor-orientation strategies may improve performance in economically developing markets with scarce resources. Likewise, Crabbé et al. ( 2013 ) indicate that the economic crisis the companies are confronted with might hinder the investment in sustainable solutions, while the intention to meet customer demands drives companies to develop sustainable innovations of products and services.

3.5.2 Innovation effects of scarcity (F8)

Technological innovation offers various scarcity-related benefits, for example, fastening the production process, increasing the quality of the products, and lowering the manufacturing cost. Advances in technology have influenced and continue to play a role in solving scarcity issues in many industries (Shankar et al. 2021 ), such as the agriculture industry (Aubert et al. 2012 ), the retail industry (Kurnia et al. 2015 ), and the IT industry (Ghosh et al. 2019 ). When it comes to the retail industry, novel technology adoption has facilitated dramatic shifts in business models, whereby e.g. personnel shortages can be overcome by chatbots (Syed et al. 2020 ). Therefore, retail researchers focus especially on technology adoption in the subfield of e-commerce (Kurnia et al. 2015 ).

However, the scarcity of social resources may impede the adoption of innovative technologies even in cases of their objective superiority. For instance, the adoption of advanced agricultural technologies leads to higher productivity as well as less pollution, thus is identified as one of the most effective solutions to severe food shortages and environmental protection issues (Aubert et al. 2012 ). However, factors such as lack of information and/or scarcity of knowledge are recognized to cause the low adoption rate and the inefficiency of new technologies diffusion (Legesse et al. 2019 ). Given the heterogeneity in different industries, various factors are detected to hinder the new technology adoption. However, trust is the common factor that boosts technology acceptance in the industries we reviewed.

3.5.3 Optimization models of scarcity (F9)

Last but not last, Factor 9 focuses on studies in the field of operations research, aiming to provide solutions to a variety of scarcity issues in production processes. Findings from mathematical modeling can guide decision-makers to improve the operational performance of the entire supply chain.

In this topic, studies take the operational perspective to optimize the performance of supply chain processes, including supply, storage, distribution, and consumption. They focus on different scare scenarios, such as supply scarcity (Fleischmann et al. 2020 ), capacity scarcity (Koch 2017 ), financial resources scarcity (Totare and Pandit 2010 ), and the scarcity of demand–supply balance (i.e., oversupply or shortage) (Orjuela Castro et al. 2021 ). Using various model optimization methods, researchers aim to maximize economic profitability, improve consumer services and enhance the efficiency of the logistics network.

4 Discussion and conclusion

Scarcity refers to situations where material or immaterial resources are not sufficient for needs satisfaction. In the last decades, scholars have investigated different facets of scarcity in different socio-economic areas, including (but not limited to) economics, politics, and social psychology (Fan et al. 2019 ). These studies in various disciplinary studies result in fruitful but rather fragmented work under the topic of scarcity (Shi et al. 2020 ). To connect disciplinary research areas and further facilitate knowledge exchange, the current paper provides a systematic review of the scarcity literature. Using exploratory factor analysis, we identified distinct research streams, which could be allotted into three prominent research realms.

The current paper captured various dimensions of scarcity in consumer markets, including the product/service scarcity in the consumer behavior research realm, the natural resources scarcity in the socio-political research realm, as well as the scarcity of managerial resources and social resources in other research realms (see Table 4 for details). Despite addressing various scarcity dimensions, studies in every research stream only focus on single scarcity dimensions, and are mainly located in single research categories.