- Essay Samples

- College Essay

- Writing Tools

- Writing guide

Creative samples from the experts

↑ Return to Essay Samples

Research Essay: Influence of Electronic Media on Print Media

Electronic media such as the Internet, e-books and tablet readers may be having an effect on the print media sector. This essay finds out if there is any validity to this argument.

Digital media does seem to have had an impact on the modern world, both affecting the online world and the offline business sectors, as well as world markets. It has certainly affected the communications sector and so it is plausible that it has affected print media too. (G5lo, 2013).

Since the year 2003, the amount of printed material in use for recreational purposes has gone down whilst the use of TV and other electronic media has gone up. This may indicate that digital media is having a direct influence on print media. (Wala, 2009).

Children are being encouraged towards digital media because there is more of it and because it is easier for parents when trying to entertain children. This means that children will grow to love digital media whilst ignoring print media. This is going to affect the print media sector in the long run. (Farnia, 2012).

Print media is easier to use and read which may be why it has not sunk out of our society completely. But, the read availability, convenience and price of digital media means that it may soon replace print media permanently. (Withers, 2012).

Studying may always rely on reading material, which begs the question of whether print media is going to fall from existence completely. It would appear that the transition from print media to digital media has been a lot slower in the academic world. And yet, it is conceivable that print media will be replaced by more convenient tablet devices in the future. (Ezeji, 2012).

Data does suggest that digital media is having an influence on the popularity of printed media, and that children are going to grow up to be fond of digital media. Print media is easier to read, but that is just one benefit of print media, where digital media has many benefits.

The evidence points towards the fact that digital media is influencing print media. But, the sliding popularity of print media may be more to do with social factors such as children are reading less. On the other hand, the benefits of digital media do seem to significantly outweigh the benefits of printed media.

Even though the reasons for the decline of print media popularity are unclear, it cannot be argued that digital media is rising. It may be rising as it replaces printed media, or it may be pushing printed media out of the arena. The two factors may be completely unrelated, but given the evidence provided on this essay, and the subsequent analysis and evaluation, I conclude that digital media is influencing print media.

Ezeji, E.C. (2012). Influence of Electronic Media on Reading Ability of School Children. Library Philosophy and Practice 2012. 1 (1), pp.1-114

Farnia (2012). Print and electronic media feeding us with information. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.essayforum.com/writing-feedback-3/print-electronic-media-feeding-us-information-37965/. [Last Accessed 22nd August 2013].

G5lo (2013). Impact of Electronic Media on the Society. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.g5lo.org.uk/index.php/8-communication/2-impact-of-electronic-media-on-the-society. [Last Accessed 22nd August 2013].

Wala, N, P. (2009). Electronic Media Stealing the Print Media’s Share! . [ONLINE] Available at: http://propakistani.pk/2009/01/30/electronic-media-stealing-the-print-media-share/. [Last Accessed 22nd August 2013].

Withers, J. (2012). Print Media Vs. Electronic Media. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.ehow.com/about_5548825_print-media-vs-electronic-media.html. [Last Accessed 22nd August 2013].

Follow Us on Social Media

Get more free essays

Send via email

Most useful resources for students:.

- Free Essays Download

- Writing Tools List

- Proofreading Services

- Universities Rating

Contributors Bio

Find more useful services for students

Free plagiarism check, professional editing, online tutoring, free grammar check.

Essay on Print Media and Electronic Media

Students are often asked to write an essay on Print Media and Electronic Media in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Print Media and Electronic Media

Print media.

Print media is a form of communication that uses printed materials, such as newspapers, magazines, and books. It has been around for centuries and has played a vital role in keeping people informed and entertained. Print media is typically more formal than electronic media and is often used for in-depth analysis and reporting.

Electronic Media

Electronic media is a form of communication that uses electronic devices, such as television, radio, and the internet. It is a relatively new form of communication, but it has quickly become one of the most popular ways to share information. Electronic media is often more immediate and interactive than print media and is often used for breaking news and entertainment.

Print media and electronic media have both advantages and disadvantages. Print media is often more reliable and in-depth, while electronic media is often more immediate and interactive. Ultimately, the best type of media for a particular purpose depends on the individual’s needs and preferences.

250 Words Essay on Print Media and Electronic Media

Print media: the traditional powerhouse of information.

Print media has ruled the realm of information dissemination for centuries. From newspapers and magazines to books and journals, printed words have shaped and molded public opinion, communicated news, and disseminated knowledge. Print media’s enduring strength lies in its tangible nature, enabling people to hold, feel, and interact with the information in a deeply personal way.

Electronic Media: The Modern Marvel of Instant Connectivity

Convergence: the intertwining of two worlds.

As technology continues to advance, print media and electronic media are increasingly converging, creating a dynamic and interconnected information landscape. Newspapers and magazines have established strong online presences, extending their reach beyond the printed page. Conversely, electronic media outlets often create print publications, blurring the lines between the two mediums.

Impact on Society: Shaping Our Understanding of the World

Both print media and electronic media wield immense influence on society, shaping our perceptions, opinions, and behaviors. They inform us about current events, educate us on a myriad of topics, and entertain us in countless ways. The accessibility and immediacy of electronic media have made it a dominant force in shaping public opinion, often influencing political discourse and societal attitudes.

Conclusion: A Symbiotic Relationship

Print media and electronic media, while seemingly distinct, are intricately intertwined. They complement each other, providing diverse avenues for information dissemination and consumption. The future of media lies in the harmonious coexistence of these two powerful forces, each playing a vital role in informing, educating, and entertaining the world.

500 Words Essay on Print Media and Electronic Media

Print media: the traditional powerhouse.

The world of information and communication has undergone a remarkable transformation over the years, with print media playing a pivotal role in shaping societies for centuries. Print media encompasses a wide range of formats, including newspapers, magazines, journals, and books. These mediums have served as primary sources of information, entertainment, and education for generations.

Newspapers, with their daily updates, have kept people informed about current events, local happenings, and global issues. Magazines, covering diverse topics from fashion and lifestyle to science and technology, have catered to a wide range of interests and provided in-depth analysis and perspectives. Journals, academic and scholarly publications, have advanced knowledge and research across various disciplines. Books, the timeless companions, have transported readers to different worlds, enriched their imaginations, and expanded their horizons.

Electronic Media: The Digital Revolution

Television, with its ability to broadcast live events and produce captivating shows, has become a ubiquitous household fixture. Radio, despite the rise of other media, has maintained its popularity, reaching audiences with news, music, and talk shows. The internet, with its boundless connectivity and accessibility, has revolutionized the way people communicate, learn, and access information. Social media platforms, connecting people across geographical boundaries, have become powerful tools for sharing news, opinions, and experiences.

Convergence: The Blending of Print and Electronic

The distinction between print and electronic media has gradually blurred over time, leading to the emergence of convergence. Convergence refers to the integration of different media platforms and technologies to create new and innovative ways of delivering information and entertainment.

Impact on Society: A Changing Landscape

The evolution of print and electronic media has profoundly impacted society in numerous ways. Access to information has become more widespread, breaking down geographical and cultural barriers. News and information can now reach remote areas and marginalized communities, empowering individuals with knowledge and enabling them to participate in public discourse.

Electronic media has also revolutionized the way people learn and consume entertainment. Online courses, educational videos, and interactive games have made learning more accessible and engaging. Streaming services and online platforms offer a vast selection of movies, TV shows, music, and other forms of entertainment, catering to diverse tastes and preferences.

The Future of Media: Embracing Innovation

Innovation will play a crucial role in shaping the future of media. Emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and augmented reality, have the potential to transform the way people consume and interact with information and entertainment. Media companies and content creators are constantly exploring new possibilities and experimenting with innovative formats to captivate audiences and deliver compelling experiences.

In conclusion, print and electronic media, with their unique strengths and characteristics, have played a profound role in informing, educating, and entertaining societies. As technology continues to advance and media landscapes evolve, the convergence of these mediums will likely lead to even more transformative and immersive experiences, shaping the way people engage with the world around them.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

The Impact of Media on Society Cause and Effect Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Role of media in the society, impact of media on society, works cited.

Media is one of the world’s power and force that can not be undermined. Media has a remarkable control in almost every aspect of our lives; in politics, social and cultural or economic welfares. Perhaps the best analysis of the impact that media has played in the society is through first acknowledging its role in information flow and circulation.

It is would be unjust to overlook the importance of information to the society. Information is the significant to the society in the sense that, all that happens in the society must be channeled and communicated among the society’s habitats. Without media, the habitats or else the population will be left clueless on what is happening or what is ought to happen.

From another perspective, the society benefits from the media in a number of ways and as well it derives a lot of misfortunes from the society. However, regardless of the impact that is made by media on the society, the media remains to be one of the strongest forces that influence the pillars of the society. This essay paper highlights the impacts that media has continued to assert on the society either in a positive or in a negative manner.

The most common role that media has played in the society has been; to inform people, to educate people and sometimes to offer leisure or entertainment. The role of media in the society is stretched back in the ancient traditions when, there were approaches on which media role in the society was perceived. Some of these approaches included a positive approach, critical approach, production approach, technological approach, information approach and finally a post colonial approach.

A positivist approach assumed that media’s role in the society was to achieve predetermined objectives of the society, usually from a beneficial perspective. The critical approach assumes that media is pertinent can be used in struggle for power and other issues in the society that were preceded by a spark of a new or old ideology.

The production approach is that media plays a greater role in society by providing a new experience of reality to the masses by providing an avenue of new perceptions and visions. The information approach assumes that the key role of media in the society is to provide information channels for the benefit of the society (Fourie178).

With the above roles being achieved in one of the most remarkable means over centuries, media has some solid impacts that have been imprinted on the society. Some of these impacts and effects are to remain for ever as long as media existence will remain while others require control and monitoring due to their negative effects on the society. The best approach to look at this is by first describing the positive impacts that media has had on the society (Fourie 25).

The development of media and advancement of mass media is such positive impact that media has accomplished in recent times. It has been proven that mass communication has influenced social foundation and governments to means that only can be termed pro-social (Preiss 485). An example of such can be use of mass media in campaigns to eradicate HIV and AIDS in the society.

Mass communication through media avenues such as the internet, television and radio has seen great co-operation of government, government agencies, non-government organizations, private corporations and the public in what is seen as key society players in mutual efforts towards constructing better society. In this context, media has contributed to awareness, education of the society and better governance of the society.

Were it not for media, the worlds most historical moments would probably be forgotten today especially in the manner they reshape our contemporary society in matters regarding politics, economics and culture (Fourie 58).

However, media has had its shortcomings that have negative influence on the society. These negatives if not counterchecked or controlled will continue to ruin the values and morals of a society that once treasured morality and value of information.

These negative impacts include: media has contributed to immense exposure of violence and antisocial acts from media program that are aimed at entertaining the public. Media roles in the society have been reversed by merely assuming a role of society visibility thus controlling the society rather than being controlled by society.

Media has continued to use biased tactics to attract society attention and thus having a negative impact on the society’s culture due to stereotyping of other cultures. Media has continued to target vulnerable groups in the society such as children and youths be exposing them to pornographic materials that has sexual immorality consequence on the society’s young generations.

It is through such shortcomings that the cognitive behavior’s which shape the moral fiber of the society gets threatened by media (Berger 106). However, regardless of the impacts of the media on the society, the future of the media will evolve with time and its role in the society will unlikely fade.

Berger, Arthur. Media and society: a critical perspective . Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. 2007.

Fourie, Pieter. Media studies: media history, media and society . Cape Town: Juta and company ltd. 2008.

Preiss, Raymond. Mass media effects research: advances through meta-analysis . New York: Routledge. 2007.

- Role of Media in Society

- ESPN Sports Media Social Response

- Technology and Communication Connection: Benefits and Shortcomings

- Wolves and Deforestation: Thinking Like a Mountain

- Managing Farm Dams to Support Waterbird Breeding

- Media and Celebrity Influence on Society

- Fowle’s Psychological Analysis of Advertisement

- Fight Club - Analysis of Consumerism

- Sidney Lumet and His Concerns

- War Perception: The Price of Human Lives

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, July 31). The Impact of Media on Society. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-media-on-society/

"The Impact of Media on Society." IvyPanda , 31 July 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-media-on-society/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'The Impact of Media on Society'. 31 July.

IvyPanda . 2018. "The Impact of Media on Society." July 31, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-media-on-society/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Impact of Media on Society." July 31, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-media-on-society/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Impact of Media on Society." July 31, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-media-on-society/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Dialogues Clin Neurosci

- v.22(2); 2020 Jun

Language: English | Spanish | French

The impact of digital technology use on adolescent well-being

El impacto del empleo de la tecnología digital en el bienestar de los adolescents, impact de l’usage des technologies numériques sur le bien-être de l’adolescent, tobias dienlin.

School of Communication, University of Hohenheim, Germany

Niklas Johannes

Institute of Neuroscience and Psychology, University of Glasgow, UK

This review provides an overview of the literature regarding digital technology use and adolescent well-being. Overall, findings imply that the general effects are on the negative end of the spectrum but very small. Effects differ depending on the type of use: whereas procrastination and passive use are related to more negative effects, social and active use are related to more positive effects. Digital technology use has stronger effects on short-term markers of hedonic well-being (eg, negative affect) than long-term measures of eudaimonic well-being (eg, life satisfaction). Although adolescents are more vulnerable, effects are comparable for both adolescents and adults. It appears that both low and excessive use are related to decreased well-being, whereas moderate use is related to increased well-being. The current research still has many limitations: High-quality studies with large-scale samples, objective measures of digital technology use, and experience sampling of well-being are missing.

Esta revisión entrega una panorámica de la literatura acerca del empleo de la tecnología digital y el bienestar de los adolescentes. En general, los resultados traducen que los efectos globales son negativos, aunque muy insignificantes. Los efectos difieren según el tipo de empleo: la procastinación y el empleo pasivo están relacionados con efectos más negativos; en cambio, el empleo social y activo se asocia con efectos más positivos. El empleo de la tecnología digital tiene efectos más potentes en los indicadores de corto plazo del bienestar hedónico (como los afectos negativos) que las mediciones a largo plazo del bienestar eudaimónico (como la satisfacción con la vida). Aunque los adolescentes son más vulnerables, los efectos son comparables para adolescentes y adultos. Parece que tanto el empleo reducido como el excesivo están relacionados con una disminución del bienestar, mientras que el empleo moderado se vincula con un mayor bienestar. La investigación actual todavía tiene muchas limitaciones: faltan estudios de alta calidad con muestras numerosas, mediciones objetivas del empleo de tecnología digital y muestras de experiencia de bienestar.

Nous proposons ici une revue de la littérature sur la pratique des technologies numériques et le bien-être de l’adolescent. Les données générales sont en faveur d’un effet négatif mais qui reste négligeable. L’usage définit la nature de l’effet : la procrastination et la passivité sont associées à un effet plus négatif alors qu’une pratique active et tournée vers la socialisation s’associe à un effet plus positif. Les effets sont plus importants sur les marqueurs à court terme du bien-être hédonique (comme les affects négatifs) que sur ceux à long terme du bien-être eudémonique (épanouissement personnel) ; ils sont comparables chez les adultes et les adolescents, même si ces derniers sont plus fragiles. Une utilisation excessive ou à l’inverse insuffisante semble diminuer le bien-être, alors qu’une pratique modérée l’augmenterait. Cependant, la recherche actuelle manque encore d’études de qualité élevée à grande échelle, de mesures objectives de la pratique des technologies numériques et d’expérience d’échantillonnage du bien-être.

With each new technology come concerns about its potential impact on (young) people’s well-being. 1 In recent years, both scholars and the public have voiced concerns about the rise of digital technology, with a focus on smartphones and social media. 2 To ascertain whether or not these concerns are justified, this review provides an overview of the literature regarding digital technology use and adolescent well-being.

Digital technology use and well-being are broad and complex concepts. To understand how technology use might affect well-being, we first define and describe both concepts. Furthermore, adolescence is a distinct stage of life. To obtain a better picture of the context in which potential effects unfold, we then examine the psychological development of adolescents. Afterward, we present current empirical findings about the relation between digital technology use and adolescent well-being. Because the empirical evidence is mixed, we then formulate six implications in order to provide some general guidelines, and end with a brief conclusion.

Digital technology use

Digital technology use is an umbrella term that encompasses various devices, services, and types of use. Most adolescent digital technology use nowadays takes place on mobile devices. 3 , 4 Offering the functions and affordances of several other media, smartphones play a pivotal role in adolescent media use and are thus considered a “metamedium.” 5 Smartphones and other digital devices can host a vast range of different services. A representative survey of teens in the US showed that the most commonly used digital services are YouTube (85%), closely followed by the social media Instagram (72%), and Snapchat (69%). Notably, there exist two different types of social media: social networking sites such as Instagram or TikTok and instant messengers such as WhatsApp or Signal.

All devices and services offer different functionalities and affordances, which result in different types of use . 6 When on social media, adolescents can chat with others, post, like, or share. Such uses are generally considered active . In contrast, adolescents can also engage in passive use, merely lurking and watching the content of others. The binary distinction between active and passive use does not yet address whether behavior is considered as procrastination or goal-directed. 7 , 8 For example, chatting with others can be considered procrastination if it means delaying work on a more important task. Observing, but not interacting with others’ content can be considered to be goal-directed if the goal is to stay up to date with the lives of friends. Finally, there is another important distinction between different types of use: whether use is social or nonsocial. 9 Social use captures all kinds of active interpersonal communication, such as chatting and texting, but also liking photos or sharing posts. Nonsocial use includes (specific types of) reading and playing, but also listening to music or watching videos.

When conceptualizing and measuring these different types of digital technology use, there are several challenges. Collapsing all digital behaviors into a single predictor of well-being will inevitably decrease precision, both conceptually and empirically. Conceptually, subsuming all these activities and types of use under one umbrella term fails to acknowledge that they serve different functions and show different effects. 10 Understanding digital technology use as a general behavior neglects the many forms such behavior can take. Therefore, when asking about the impact of digital technology use on adolescent well-being, we need to be aware that digital technology use is not a monolithic concept.

Empirically, a lack of validated measures of technology use adds to this imprecision. 11 Most work relies on self-reports of technology use. Self-reports, however, have been shown to be imprecise and of low validity because they correlate poorly with objective measures of technology use. 12 In the case of smartphones, self-reported duration of use correlated moderately, at best, with objectively logged use. 13 These findings are mirrored when comparing self-reports of general internet use with objectively measured use. 14 Taken together, in addition to losing precision by subsuming all types of technology use under one behavioral category, the measurement of this category contributes to a lack of precision. To gain precision, it is necessary that we look at effects for different types of use, ideally objectively measured.

Well-being

Well-being is a subcategory of mental health. Mental health is generally considered to consist of two parts: negative and positive mental health. 15 Negative mental health includes subclinical negative mental health, such as stress or negative affect, and psychopathology, such as depression or schizophrenia. 16 Positive mental health is a synonym for well-being; it comprises hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being. 17 Whereas hedonic well-being is affective, focusing on emotions, pleasure, or need satisfaction, eudaimonic well-being is cognitive, addressing meaning, self-esteem, or fulfillment.

Somewhat surprisingly, worldwide mental health problems have not increased in recent decades. 18 Similarly, levels of general life satisfaction remained stable during the last 20 years. 19 , 20 Worth noting, the increase in mental health problems that has been reported 21 could merely reflect increased awareness of psychosocial problems. 22 , 23 In other words, an increase in diagnoses might not mean an increase in psychopathology.

Which part of mental health is the most likely to be affected by digital technology use? Empirically, eudaimonic well-being, such as life satisfaction, is stable. Although some researchers maintain that 40% of happiness is volatile and therefore malleable, 24 more recent investigations argued that the influences of potentially stabilizing factors such as genes and life circumstances are substantially larger. 25 These results are aligned with the so-called set-point hypothesis, which posits that life satisfaction varies around a fixed level, showing much interpersonal but little intrapersonal variance. 26 The hypothesis has repeatedly found support in empirical studies, which demonstrate the stability of life satisfaction measures. 27 , 28 Consequently, digital technology use is not likely to be a strong predictor of eudaimonic well-being. In contrast, hedonic well-being such as positive and negative affect is volatile and subject to substantial fluctuations. 17 Therefore, digital technology use might well be a driver of hedonic well-being: Watching entertaining content can make us laugh and raise our spirits, while reading hostile comments makes us angry and causes bad mood. In sum, life satisfaction is stable, and technology use is more likely to affect temporary measures of hedonic well-being instead of more robust eudaimonic well-being. If this is the case, we should expect small to medium-sized effects on short-term affect, but small to negligible effects on both long-term affect and life satisfaction.

Adolescents

Adolescence is defined as “the time between puberty and adult independence,” 29 during which adolescents actively develop their personalities. Compared with adults, adolescents are more open-minded, more social-oriented, less agreeable, and less conscientious 30 ; more impulsive and less capable of inhibiting behavior 31 ; more risk-taking and sensation seeking 29 ; and derive larger parts of their well-being and life satisfaction from other peers. 32 During adolescence, general levels of life satisfaction and self-esteem drop and are often at their all-time lowest. 33 , 34 At the same time, media use increases and reaches a first peak in late adolescence. 3 Analyzing the development of several well-being-related variables across the last two decades, the answers of 46 817 European adolescents and young adults show that, whereas overall internet use has risen strongly, both life satisfaction and health problems remained stable. 19 Hence, although adolescence is a critical life stage with substantial intrapersonal fluctuations related to well-being, the current generation does not seem to do better or worse than those before.

Does adolescent development make them particularly susceptible to the influence of digital technology? Several scholars argue that combining the naturally occurring trends of low self-esteem, a spike in technology use, and higher suggestibility into a causal narrative can take the form of a foregone conclusion. 35 For one, although adolescents are in a phase of development, there might be more similarities between adolescents and adults than differences. 30 Concerns about the effects of a new technology on an allegedly vulnerable group has historically often taken the form of paternalization. 36 For example, and maybe in contrast to popular opinion, adolescents already possess much media literacy or privacy literacy. 3

This has two implications. First, asking what technology does to adolescents ascribes an unduly passive role to adolescents, putting them in the place of simply responding to technology stimuli. Recent theoretical developments challenge such a one-directional perspective and advise to rather ask what adolescents do with digital technology , including their type of use. 37 Second, in order to understand the effects of digital technology use on well-being, it might not be necessary to focus on adolescents. It is likely that similar effects can be found for both adolescents and adults. True, in light of the generally decreased life satisfaction and the generally increased suggestibility, results might be more pronounced for adolescents; however, it seems implausible that they are fundamentally different. When assessing how technology might affect adolescents compared with adults, we can think of adolescents as “canaries in the coalmine.” 38 If digital technology is indeed harmful, it will affect people from all ages, but adolescents are potentially more vulnerable.

Effects

What is the effect of digital technology use on well-being? If we ask US adolescents directly, 31% are of the opinion that the effects are mostly positive, 45% estimate the effects to be neither positive nor negative, and 24% believe that effects are mostly negative. 4 Teens who considered the effects to be positive stated that social media help (i) connect with friend; (ii) obtain information; and (c) find like-minded people. 4 Those who considered the effects to be negative explained that social media increase the risks of (i) bullying; (ii) neglecting face-to-face contacts; (iii) obtaining unrealistic impressions of other people’s lives. 4

Myriad studies lend empirical support to adolescents’ mixed feelings, reporting a wide range of positive, 39 neutral, 40 or negative 41 relations between specific measures of digital technology use and well-being. Aligned with these mixed results of individual studies, several meta-analyses support the lack of a clear effect. 42 In an analysis of 43 studies on the effects of online technology use on adolescent mental well-being, Best et al 43 found that “[t]he majority of studies reported either mixed or no effect(s) of online social technologies on adolescent wellbeing.” Analyzing eleven studies on the relation between social media use and depressive symptoms, McCrae et al 44 report a small positive relationship. Similarly, Lissak 45 reports positive relations between excessive screen time and insufficient sleep, physiological stress, mind wandering, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)-related behavior, nonadaptive/negative thinking styles, decreased life satisfaction, and potential health risks in adulthood. On the basis of 12 articles, Wu et al 46 find that “the use of [i]nternet technology leads to an increased sense of connectedness to friend[s] and school, while at the same time increasing levels of anxiety and loneliness among adolescents.” Relatedly, meta-analyses on the relation between social media use and adolescent academic performance find no or negligible effects. 47

It is important to note that the overall quality of the literature these meta-analyses rely upon has been criticized. 48 This is problematic because low quality of individual studies biases meta-analyses. 49 To achieve higher quality, scholars have called for more large-scale studies using longitudinal designs, objective measures of digital technology use that differentiate types of use, experience sampling measures of well-being (ie, in-the-moment measures of well-being; also known as ambulant assessment or in situ assessment), and a statistical separation of between-person variance and within-person variance. 50 In addition, much research cannot be reproduced because the data and the analysis scripts are not shared. 51 In what follows, we look at studies that implemented some of these suggestions.

Longitudinal studies generally find a complex pattern of effects. In an 8 year study of 500 adolescents in the US, time spent on social media was positively related to anxiety and depression on the between-person level. 52 At the within-person level, these relationships disappeared. The study concludes that those who use social media more often might also be those with lower mental health; however, there does not seem to be a causal link between the two. A study on 1157 Croatians in late adolescence supports these findings. Over a period of 3 years, changes in social media use and life satisfaction were unrelated, speaking to the stability of life satisfaction. 40 In a sample of 1749 Australian adolescents, Houghton et al 53 distinguished between screen activities (eg, web browsing or gaming) and found overall low within-person relations between total screen time and depressive symptoms. Out of all activities, only web surfing was a significant within-person predictor of depressive symptoms. However, the authors argue that this effect might not survive corrections for multiple testing. Combining a longitudinal design with experience sampling in a sample of 388 US adolescents, Jensen et al 54 did not find a between-person association between baseline technology use and mental health. Interestingly, they only observed few and small within-person effects. Heffer et al 55 found no relation between screen use and depressive symptoms in 594 Canadian adolescents over 2 years. These results emphasize the growing need for more robust and transparent methods and analysis. In large adolescent samples from the UK and the US, a specification curve analysis, which provides an overview of many different plausible analyses, found small, negligible relations between screen use and well-being, both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. 56 Employing a similar analytical approach, Orben, Dienlin, and Przybylski 57 found small negative between-person relations between social media use and life satisfaction in a large UK sample of adolescents over 7 years. However, there was no robust within-person effect. Similarly, negligible effect sizes between adolescent screen use and well-being are found in cross-sectional data sets representative of the population in the UK and US. 58 In analyzing the potential effects of social media abstinence on well-being, two large-scale studies using adult samples found small positive effects of abstinence on well-being. 59 , 60 Two studies with smaller and mostly student samples instead found mixed 61 or no effects of abstinence on well-being. 62

The aforementioned studies often relied on composite measures of screen use, possibly explaining the overall small effects. In contrast, work distinguishing between different types of use shows that active use likely has different effects than passive use. Specifically, active use may contribute to making meaningful social connections, whereas passive use does not. 9 For example, meaningful social interactions have been shown to increase social gratification in adults, 63 , 64 whereas passive media use or media use as procrastination has been negatively related to well-being. 6 , 8 This distinction should also apply to adolescents. 6 The first evidence for this proposition already exists. In a large sample of Icelandic adolescents, passive social media use was positively related to anxiety and depressive symptoms; the opposite was the case for active use. 65

Furthermore, longitudinal work so far relies on self-reports of media use. Self-reported media use has been shown to be inaccurate compared with objectively measured use. 14 Unfortunately, there is little work employing objective measures to test whether the results of longitudinal studies using self-reports hold up when objective use is examined. The limited existing evidence suggests that effects remain small. In a convenience sample of adults, only phone use at night negatively predicted well-being. 66 Another study that combined objective measures of social smartphone applications with experience sampling in young adults found a weak negative relation between objective use and well-being. 67

Effects might also not be linear. Whereas both low and high levels of internet use have been shown to be associated with slightly decreased life satisfaction, moderate use has been shown to be related to slightly increased life satisfaction. 10 , 35 , 68 However, evidence for this position is mixed; other empirical studies did not find this pattern of effects. 53 , 54

Taken together, do the positive or the negative effects prevail? The literature implies that the relationship between technology use and adolescent well-being is more complicated than an overall negative linear effect. In line with meta-analyses on adults, effects of digital technology use in general are mostly neutral to small. In their meta-review of 34 meta-analyses and systematic reviews, Meier and Reinecke 42 summarize that “[f]indings suggest an overall (very) small negative association between using SNS [social networking sites], the most researched CMC [computer mediated communication] application, and mental health.” In conclusion, the current literature is mostly ambivalent, although slightly emphasizing the negative effects of digital tech use.

Implications

Although there are several conflicting positions and research findings, some general implications emerge:

1. The general effects of digital technology use on well-being are likely in the negative spectrum, but very small—potentially too small to matter.

2. No screen time is created equal; different uses will lead to different effects.

3. Digital technology use is more likely to affect short-term positive or negative affect than long-term life satisfaction.

4. The dose makes the poison; it appears that both low and excessive use are related to decreased well-being, whereas moderate use is related to increased well-being.

5. Adolescents are likely more vulnerable to effects of digital technology use on well-being, but it is important not to patronize adolescents—effects are comparable and adolescents not powerless.

6. The current empirical research has several limitations: high-quality studies with large-scale samples, objective measures of digital technology use, and experience sampling of well-being are still missing.

Conclusion

Despite almost 30 years of research on digital technology, there is still no coherent empirical evidence as to whether digital technology hampers or fosters well-being. Most likely, general effects are small at best and probably in the negative spectrum. As soon as we take other factors into account, this conclusion does not hold up. Active use that aims to establish meaningful social connections can have positive effects. Passive use likely has negative effects. Both might follow a nonlinear trend. However, research showing causal effects of general digital technology use on well-being is scarce. In light of these limitations, several scholars argue that technology use has a mediating role69: already existing problems increase maladapted technology use, which then decreases life satisfaction. Extreme digital technology use is more likely to be a symptom of an underlying sociopsychological problem than vice versa. In sum, when assessing the effects of technology use on adolescent well-being, one of the best answers is that it’s complicated.

This lack of evidence is not surprising, because there is no consensus on central definitions, measures, and methods. 42 Specifically, digital technology use is an umbrella term that encompasses many different behaviors. Furthermore, it is theoretically unclear as to why adolescents in particular should be susceptible to the effects of technology and what forms of well-being are candidates for effects. At the same time, little research adopts longitudinal designs, differentiates different types of technology use, or measures technology use objectively. Much work in the field has also been criticized for a lack of transparency and rigor. 51 Last, research (including this review) is strongly biased toward a Western perspective. In other cultures, adolescents use markedly different services (such as WeChat or Renren, etc). Although we assume most effects to be comparable, problems seem to differ somewhat. For example, online gaming addiction is more prevalent in Asian than Western cultures. 70

Adults have always criticized the younger generation, and media (novels, rock music, comic books, or computer games) have often been one of the culprits. 1 Media panics are cyclical, and we should refrain from simply blaming the unknown and the novel. 1 In view of the public debate, we should rather emphasize that digital technology is not good or bad per se. Digital technology does not “happen” to individuals. Individuals, instead, actively use technology, often with much competence. 3 The current evidence suggests that typical digital technology use will not harm a typical adolescent. That is not to say there are no individual cases and scenarios in which effects might be negative and large. Let’s be wary, but not alarmist.

Acknowledgments

Both authors declare no conflicts of interest. Both authors contributed equally to this manuscript. Tobias Dienlin receives funding from the Volkswagen Foundation. We would like to thank Amy Orben for valuable feedback and comments

What’s Next? How Digital Media Shapes Our Society

By John McDonald

September 1, 2021

A summary of Professor Leah A. Lievrouw’s most recent book, which explores the rapidly changing role communication plays at the center of human experience and endeavor.

UCLA Information Studies Professor Leah A. Lievrouw’s first academic job was at Rutgers University in the late 1980s. One day, a colleague, a media effects researcher, was talking with her in her office and said, “Well, you know this new media stuff, it’s kind of interesting, but really it’s just a fad, isn’t it?”

That “new media stuff” has been the centerpiece of Lievrouw’s research ever since and today is central to many of the economic, social, political and policy challenges that confront the globe.

“My interest is in new technologies, communication information technologies and social change, and how change happens for good and ill. It’s really a sociological take. I’m more interested in what’s going on at the whole society or whole community level,” Lievrouw said. Professor Lievrouw joined the UCLA Department of Information Studies in 1995 and in 2005 co-edited “The Handbook of New Media” (Sage Publications), with Sonia Livingston of the London School of Economics. The book became a central resource for study of the field and is still used in classrooms and cited in research.

“It was really a big comprehensive survey with leading people in the field who were working on this research, right across various sub-fields and different topics,” Lievrouw said. “For a long time and in some circles still it is kind of the definitive capture of what the field was like and what the issues were at the moment.”

With changes in technology and communication rapidly occurring with ever larger impact, Lievrouw and her colleagues began talking about not just an update, but a whole new book.

Lievrouw decided to move forward and eventually linked up with Brian Loader, a professor at the University of York in the United Kingdom and editor-in-chief of the journal Information, Communication and Society, to serve as co-editor.

The book draws together the work of scholars from across the globe to examine the forces that shape our digital social lives and further our understanding of the sociocultural impact of digital media.

Routledge Handbook of Digital Media and Communication

“As of this writing, as the world undergoes breakdowns in social, institutional, and technological systems across every domain of human affairs in the wake of a biological and public health crisis of unprecedented scale and scope, such a framework for understanding communicative action, technology, and social forms has never been so apt or so urgently needed.” – Routledge Publishing

Mirroring the approach of the earlier “Handbook of Social Media,” the book is organized into a three-part framework exploring the artifacts or devices, the practices and institutional arrangements that are central to digital media, and draws the connections across the three elements.

The book explores topics such as the power of algorithms, digital currency, gaming culture, surveillance, social networking, and connective mobilization. As described in the introduction by Routledge, the “Handbook delivers a comprehensive, authoritative overview of the state of new media scholarship and its most important future directions that will shape and animate current debates.”

“I really like that again this seems to be a pretty definitive state-of-the-art kind of look at what is going on with these technologies,” Lievrouw said. “This has perhaps a more critical edge than we had 20 years ago, because we have begun to see the downsides of digital media as well as all the upsides that everyone had such hopes about. What makes me really happy is that this volume kind of pulls back a bit and takes a bigger stock of the issues and challenges. We have a few chapters that I think are just really definitive, written by some of the very best people on the planet. We were very lucky to recruit such a terrific lineup of people.”

Professor Lievrouw refers to a series of essays on critical topics in the book by leading experts such as Paul Dourish exploring Ubiquity or the everywhereness of digital media; Veronica Barrasi, writing about youth, algorithms, and political data; and Julie Cohen, writing about the nature of property in a world driven by social media and more.

“In her chapter, Cohen asks, what’s the nature of property? Every aspect of our behavior or of our beliefs is constantly kind of being pulled away from us, appropriated and owned by outfits like Google and like Facebook. They now consider this their proprietary information, and we’ve not had that before in the world really, certainly not on this scale. I think that’s worth exploring,” Lievrouw said.

Timing is everything, and the new book is emerging at a time of particular relevance and questioning about digital media.

“The book has happened to come out at a moment when there’s so much skepticism, and so much worry,” Professor Lievrouw said. “What’s interesting is that the worry is in the scholarly community too and has been for a little while.

“We’re in that moment where we are having to look, not only at the most egregious and outrageous behaviors, opinions, and disinformation, and all the kinds of things that have come out from under the rocks. And the system itself is rather mature at this point, so the question becomes, ‘Where is it going to go? What do we do next? Is it just more incursion, more data, more surveillance, more circulation of stuff?’ And we are doing it without editing, without gatekeepers. And we should never forget about the impact of places like Facebook, Google, Amazon. “It has changed social structure.

It has changed cultural practices. It has changed our perception of the world fundamentally. And I think it’s not just the technology that did this, it’s the way we built it.

“I think we are entering a period of reckoning about these technologies, the whole complex of people involved in the building and operation of platforms and different kinds of applications, especially data gathering. Data has come to the center of the economics of this thing in a way that it hasn’t before. This is a good moment to reassess what works, what has been emancipatory, what has been enabling for people, how the diffusion of these technologies, and the adaptation of their use, is impacting different places and different cultures all over the world.

“Every thoughtful researcher in this area I know is turning this over in their head, saying, ‘How did we get to this point? What happened here?’ I think what this book can help us understand not only where we are right now, but also to think about what could be next, and what can we do to repair this. Right now, I don’t think anybody has a solid answer for that. If they do, it’s an answer they don’t like.”

Excerpt from Introduction

No longer new, digital media and communication technologies—and their associated infrastructures, practices, and cultural forms—have become woven into the very social fabric of contemporary human life. Despite the cautiously optimistic accounts of the potential of the Internet to foster stronger democratic governance, enable connective forms of mobilization, stimulate social capital (community, social, or crisis informatics), restructure education and learning, support remote health care, or facilitate networked flexible organization, the actual development of digital media and communication has been far more problematic. Indeed, recent commentary has been more pessimistic about the disruptive impact of digital media and communication upon our everyday lives. The promise of personal emancipation and free access to unlimited digital resources has, some argue, led us to sleepwalk into a world of unremitting surveillance, gross disparities in wealth, precarious employment opportunities, a deepening crisis in democracy, and an opaque global network of financial channels and transnational corporations with unaccountable monopoly power.

A critical appraisal of the current state of play of the digital world is thus timely, indeed overdue, and required if we are to examine these assertions and concerns clearly. There is no preordained technological pathway that digital media must follow or are following. A measure of these changes is the inadequacy of many familiar concepts— such as commons, public sphere, social capital, class, and others—to capture contemporary power relations or to explain transitions from “mass society” to networked sociality—or from mass to personalized consumption. Even the strategies of resistance to these transitions draw upon traditional appeals to unionization, democratic accountability, mass mobilization, state regulation, and the like, all part of the legacy of earlier capitalist and political forms.

How then to examine the current digitalscape? Internet-based and data-driven systems, applications, platforms, and affordances now play a pivotal role in every domain of social life. Under the rubric of new media research, computer-mediated communication, social media or Internet studies, media sociology, or media anthropology, research and scholarship in the area have moved from the fringe to the theoretical and empirical center of many disciplines, spawning a whole generation of new journals and publishers’ lists. Within communication research and scholarship itself, digital technologies and their consequences have become central topics in every area of the discipline—indeed, they have helped blur some of the most enduring boundaries dividing many of the field’s traditional specializations. Meanwhile, the ubiquity, adaptability, responsiveness, and networked structure of online communication, the advantages of which—participation, convenience, engagement, connectedness, community—were often celebrated in earlier studies, have also introduced troubling new risks, including pervasive surveillance, monopolization, vigilantism, cyberwar, worker displacement, intolerance, disinformation, and social separatism.

Technology infrastructure has several defining features that make it a distinctive object of study. Infrastructures are embedded; transparent (support tasks invisibly); have reach or scope beyond a single context; learned as part of membership in a social or cultural group; are linked to existing practices and routines; embody standards; are built on an existing, installed base; and, perhaps most critically, ordinarily become “visible” or apparent to users only when they break down: when “the server is down, the bridge washes out, there is a power blackout.” As of this writing, as the world undergoes breakdowns in social, institutional, and technological systems across every domain of human affairs in the wake of a biological and public health crisis of unprecedented scale and scope, such a framework for understanding communicative action, technology, and social forms has never been so apt or so urgently needed.

Two cross-cutting themes had come to characterize the quality and processes of mediated communication over the prior two decades. The first is a broad shift from the mass and toward the network as the defining structure and dominant logic of communication technologies, systems, relations, and practices; the second is the growing enclosure of those technologies, relations, and practices by private ownership and state security interests. These two features of digital media and communication have joined to create socio-technical conditions for communication today that would have been unrecognizable even to early new media scholars of the 1970s and 1980s, to say nothing of the communication researchers before them specializing in classical media effects research, political economy of media, interpersonal and group process, political communication, global/comparative communication research, or organizational communication, for example.

This collection of essays reveals an extraordinarily faceted, nuanced picture of communication and communication studies, today. For example, the opening part, “Artifacts,” richly portrays the infrastructural qualities of digital media tools and systems. Stephen C. Slota, Aubrey Slaughter, and Geoffrey C. Bowker’s piece on “occult” infrastructures of communication expands and elaborates on the infrastructure studies perspective. Paul Dourish provides an incisive discussion on the nature and meaning of ubiquity for designers and users of digital systems. Essays on big data and algorithms (Taina Bucher), mobile devices and communicative gestures (Lee Humphreys and Larissa Hjorth), digital embodiment and financial infrastructures (Kaitlyn Wauthier and Radhika Gajjala), interfaces and affordances (Matt Ratto, Curtis McCord, Dawn Walker, and Gabby Resch), hacking (Finn Brunton), and digital records and memory (David Beer) demonstrate how computation and data generation/capture have transfigured both the material features and the human experience of engagement with media technologies and systems. The second part, “Practices,” shifts focus from devices, tools, and systems to the communicative practices of the people who use them. Digital media and communication today have fostered what some writers have called datafication—capturing and rendering all aspects of communicative action, expression, and meaning into quantified data that are often traded in markets and used to make countless decisions about, and to intercede in, people’s experiences. Systems that allow people to make and share meaning are also configured by private-sector firms and state security actors to capture and enclose human communication and information.

This dynamic is played out in routine monitoring and surveillance (an essay by Mark Andrejevic), in the construction and practice of personal identity (Mary Chayko), in family routines and relationships (Nancy Jennings), in political participation (Brian Loader and Veronica Barassi), in our closest relationships and sociality (Irina Shklovski), in education and new literacies (Antero Garcia), in the increasing precarity of “information work” (Leah Lievrouw and Brittany Paris), and in what Walter Lippmann famously called the “picture of reality” portrayed in the news (Stuart Allan, Chris Peters, and Holly Steel). Many suggest that the erosion of boundaries between public and private, true and false, and ourselves and others is increasingly taken for granted, with mediated communication as likely to create a destabilizing, chronic sense of disruption and displacement as it is to promote deliberation, cohesion, or solidarities.

The broader social, organizational, and institutional arrangements that shape and regulate the tools and the practices of digital communication and information, and which themselves are continuously reformed, are explored in the third part. Nick Couldry starts with an overview of mediatization, the growing centrality of media in what he calls the “institutionalization of the social” and the establishment of social order, at every level from microscale interaction to the jockeying among nation-states. There are essays that present evidence of the instability, uncertainty, and delegitimation associated with digital media; reflections on globalization; a survey of governance and regulation; a revisitation of political economy; and the trenchant reconsideration of the notion of property. Elena Pavan and Donatella della Porta examine the role of digital media in social movements while Keith Hampton and Barry Wellman argue that digital technologies may, in fact, help reinforce people’s senses of community and belonging both online and offline. Shiv Ganesh and Cynthia Stohl show that while much past research was focused on the “fluidity” or formlessness of organization afforded by “digital ubiquity,” in fact contemporary organizing is a more subtle process comprising “opposing tendencies and human activities, of both form and formlessness.”

Taken together, the contributions present a complex, interwoven technical, social/cultural, and institutional fabric of society, which nonetheless seems to be showing signs of wear, or perhaps even breakdown in response to systemic environmental and institutional crises. As digital media and communication technologies have become routine, even banal—convenience, immediacy, connectedness—they are increasingly accompanied by a growing recognition of their negative externalities—monopoly and suppressed competition, ethical and leadership failures, and technological lock-in instead of genuine, path breaking innovation. The promise and possibility of new media and digitally mediated communication are increasingly tempered with sober assessments of risk, conflict, and exploitation.

This scenario may seem pessimistic, but perhaps one way to view the current state of digital media and communication studies is that it has matured, or reached a moment of consolidation, in which the visionary enthusiasms and forecasts of earlier decades have grown into a more developed or skeptical perspective. Digital media platforms and systems have diffused across the globe into cultural, political, and economic contexts and among diverse populations that often challenge the assumptions and expectations that were built into the early networks. The systems themselves, and their ownership and operations, have stabilized and become routinized, much as utilities and earlier media systems have done before, so they are more likely to resist root-and-branch change. They are as likely to reinforce and sustain patterns of knowledge and power as they are to “disrupt” them.

In another decade we might expect to find that the devices, practices, and institutional arrangements will have become even more integrated into common activities, places, and experiences, and culture will be unremarkable, embedded, woven into cultural practices, standardized, and invisible or transparent, just as satellite transmissions and undersea cables, or content streaming and social media platforms, are to us today. These socio-technical qualities will pose new kinds of challenges for communication researchers and scholars, but they also herald possibilities for a fuller, deeper understanding of the role communication plays at the center of human experience and endeavor.

This article is part of the UCLA Ed&IS Magazine Summer 2021 Issue. To read the full issue click here .

© 2024 Regents of the University of California

- Accessibility

- Report Misconduct

- Privacy & Terms of Use

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 21 February 2018

Media use and brain development during adolescence

- Eveline A. Crone 1 &

- Elly A. Konijn 2

Nature Communications volume 9 , Article number: 588 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

194k Accesses

252 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cognitive neuroscience

The current generation of adolescents grows up in a media-saturated world. However, it is unclear how media influences the maturational trajectories of brain regions involved in social interactions. Here we review the neural development in adolescence and show how neuroscience can provide a deeper understanding of developmental sensitivities related to adolescents’ media use. We argue that adolescents are highly sensitive to acceptance and rejection through social media, and that their heightened emotional sensitivity and protracted development of reflective processing and cognitive control may make them specifically reactive to emotion-arousing media. This review illustrates how neuroscience may help understand the mutual influence of media and peers on adolescents’ well-being and opinion formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mechanisms linking social media use to adolescent mental health vulnerability

Diverse adolescents’ transcendent thinking predicts young adult psychosocial outcomes via brain network development

Long-term impact of digital media on brain development in children

Introduction.

Media play a tremendously important role in the lives of today’s youth, who grow up with tablets and smartphones, and do not remember a time before the internet, and are hence called ‘digital natives’ 1 , 2 . The current generation of the adolescents lives in a media-saturated world, where media is used not only for entertainment purposes, such as listening to music or watching movies, but is also used increasingly for communicating with peers via WhatsApp, Instagram, SnapChat, Facebook, etc. Taken together, these media-related activities comprise roughly 6–9 h of an American youth’s day, excluding home- and schoolwork ( https://www.commonsensemedia.org/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-tweens-and-teens-infographic ) 3 , 4 . Social media enable people to share information, ideas or opinions, messages, images and videos. Today, all kinds of media formats are constantly available through portable mobile devices such as smartphones and have become an integrated part of adolescents’ social life 5 .

Adolescence, which is defined as the transition period between childhood and adulthood (approximately ages 10–22 years, although age bins differ between cultures), is a developmental stage in which parental influence decreases and peers become more important 6 . Being accepted or rejected by peers is highly salient in adolescence, also there is a strong need to fit into the peer group and they are highly influenced by their peers 7 . Therefore, it is imperative that we understand how adolescents process media content and peers’ feedback provided on such platforms. Adolescents’ social lives in particular seem to occur for a large part through smartphones that are filled with friends with whom they are constantly connected (cf. “A day not wired is a day not lived” 5 , 8 ). This is where they monitor their peer status, check peers’ feedback, rejection and acceptance messages, and encounter peers as (idealized) images 9 on screens 5 , 8 , 10 . Likely, this plays an important role in adolescent development, and we therefore focus primarily on adolescents’ social media use 11 . Most media research to date is based on correlational and self-report data, and would be strengthened by integrating experimental paradigms and more objectively assessed behavioral, emotional, and neural consequences of experimentally induced media use.

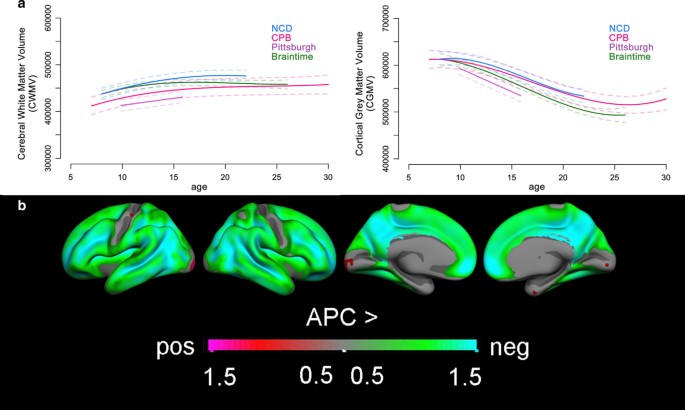

Recently, cognitive neuroscience studies have used structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine how the adolescent brain changes over the course of the adolescent years 6 . The results of several studies demonstrate that cognitive and socio-affective development in adolescence is accompanied by extensive changes in the structure and function of the adolescent brain 6 . Structurally, white matter connections increase, allowing for more successful communication between different areas of the brain 12 . The maturation of these connections is related to behavioral control, for example, connections between the prefrontal cortex and the subcortical striatum mediate age-related improvements in the ability to wait for a reward 13 . In addition to these changes in white matter connections, neurons in the brain grow in number between conception and childhood, with greatest synaptic density in early childhood. This increase in synaptic density co-occurs with synaptic pruning, and pruning rates increase in adolescence, resulting in a decrease in synaptic density in late childhood and adolescence 14 . Structural MRI research revealed that the peak in grey matter volume probably occurs before the age of 10 years, but dynamic non-linear changes in grey matter volume continue over the whole period of adolescence, and the timing is region-specific 15 . Interestingly, changes in grey matter volume are observed most extensively in brain regions that are important for social understanding and communication such as the medial prefrontal cortex, superior temporal cortex and temporal parietal junction 16 . Figure 1 displays the extensive changes in the human cortex during adolescence.

Longitudinal changes in brain structure across adolescence (ages 8–30). a Consistent patterns of change across four independent longitudinal samples (391 participants, 852 scans), with increases in cerebral white matter volume and decreases in cortical grey matter volume (adapted from Mills et al., 2016, NeuroImage 105 ). b Of the two main components of cortical volume, surface area and thickness, thinning across ages 8 to 25 years is the main contributor to volume reduction across adolescence, here displayed in the Braintime sample (209 participants, 418 scans). Displayed are regional differences in annual percentage change (APC) across the whole brain, the more the color changes in the direction of green to blue, the larger the annual decrease in volume (adapted from Tamnes et al., 2017, J Neuroscience 15 )

Given that brain regions involved in many social aspects of life are undergoing such extensive changes during adolescence, it is likely that social influences—which also occur through the use of social media as the internet connects adolescents to many people at once—are particularly potent at this age in coalescence with their media use. Also, subcortical brain regions undergo pronounced changes during adolescence 17 . There is evidence that the density of grey matter volume in the amygdala, a structure associated with emotional processing, is related to larger offline social networks 18 , as well as larger online social networks 19 , 20 . This suggests an important interplay between actual social experiences, both offline and online, and brain development.

This review brings together research on media use among adolescents with neural development during adolescence. We will specifically focus on the following three aspects of media exposure of interest to adolescent development 21 : (1) social acceptance or rejection, (2) peer influence on self-image and self-perception, and (3) the role of emotions in media use. Finally, we discuss new perspectives on how the interplay between media exposure and sensitive periods in brain development may make some individuals more susceptible to the consequences of media use than others.

Being accepted or rejected online

Experiencing acceptance or rejection when communicating via digital media is an impactful social experience. Extensive research, including large meta-analyses, has demonstrated that social rejection in a computerized environment can be experienced similarly as face-to-face rejection and bullying, although the prevalence of cyberbullying is generally lower 22 , 23 (and studies vary widely: prevalence rates depend on how cyberbullying is defined and measured). In all, cyberbullying peaks during adolescence 24 and large overlap has been found between victims and bullies. In part, this overlap could be explained by victimized adolescents seeking exposure to antisocial and risk behavior media content 25 . The next subsections will describe recent discoveries in neuroscience on the neural responses to online rejection and acceptance.

Neural responses to online social rejection

The emotional and neural effects of being socially excluded have been well captured by research involving the Cyberball Paradigm 26 ( https://cyberball.wikispaces.com/ ). Cyberball is a virtual ball-toss game in which the study participant tosses a ball with two simulated players (so-called confederates) via a screen. After a round of fair play, the confederates, who only throw the ball to each other, exclude the participant in the rejection condition. This results in pronounced negative effects on the participants’ feeling to belong, ostracism, sense of control, and self-esteem 26 . Even though the paradigm was not designed to study online rejection as it occurs today on social media, the findings of prior Cyberball studies may provide an important starting point for understanding the processes involved in online rejection. In fact, inspired by Cyberball, a Social Media Ostracism paradigm has recently been developed by applying a Facebook format to study the effects of online social exclusion 27 .

Using functional MRI (fMRI), researchers have observed increased activity in the orbitofrontal cortex and insula after participants experienced exclusion, possibly signaling increased arousal and negative affect 28 . In addition, stronger activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is observed in adolescents and young adults with a history of being socially excluded 29 , maltreated 30 , or insecure attachment, whereas spending more time with friends reduced ACC response in adolescents to social exclusion 31 . This may possibly protect adolescents against the negative influence of ostracism or cyberbullying, although all these studies are correlational. Therefore, it remains to be determined whether environment influences brain development or vice versa. Moreover, ACC and insula activity have also been explained as signaling a highly significant event because the same regions are also active when participants experience inclusion 32 . Furthermore, studies with adolescents observed specific activity in the ventral striatum 33 , and in the subgenual ACC when adolescents were excluded in the online Cyberball computer game 34 , 35 , the latter region is often implicated in depression 36 . Thus, being rejected was associated with activity in brain regions that are also activated when experiencing salient emotions 37 , 38 . These studies may indicate a specific window of sensitivity to social rejection in adolescence, which may be associated with the enhanced activity of striatum and subgenual ACC in adolescence 33 , 36 .

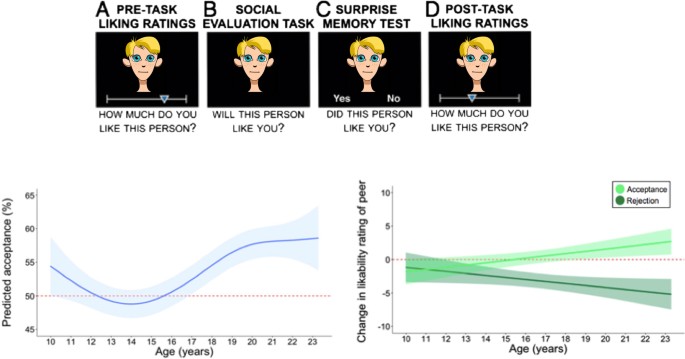

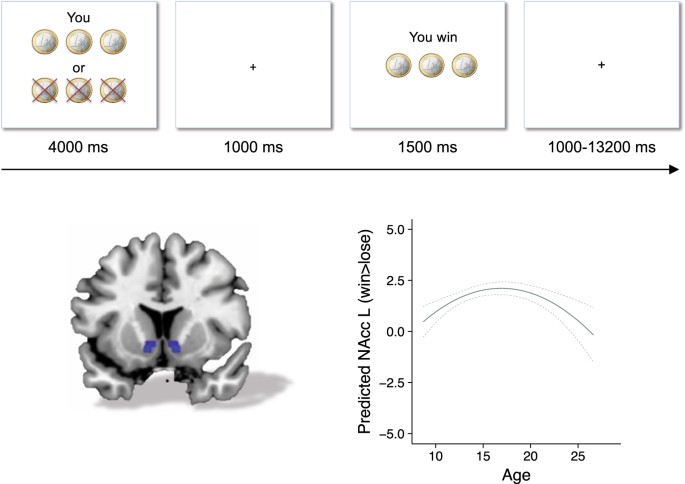

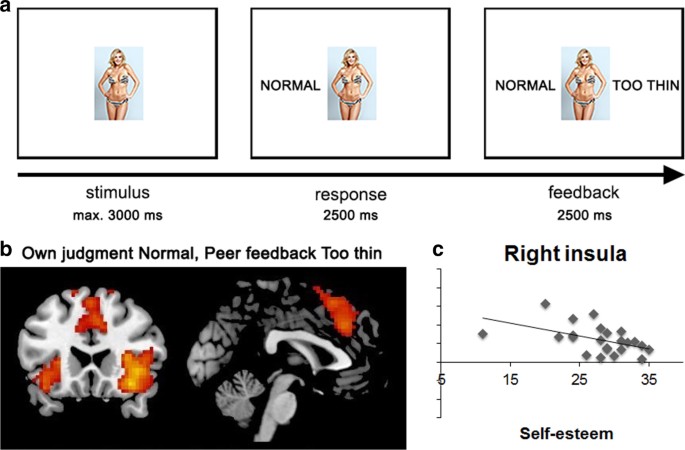

Social rejection has also been studied using task paradigms that mirror online communication more specifically. In the social judgment paradigm, participants enter a chat room, where others can judge their profile pictures based on first impression 39 . This can result in being rejected or accepted by others in a way that is directly comparable to social media environments where individuals connect based on first impression (for example,’liking’ on Instagram). A developmental behavioral study (participants between 10 and 23 years) showed that young adults expected to be accepted more than adolescents. Moreover, these adults, relative to adolescents, adjusted their evaluations of others more based on whether others accepted or rejected them, possibly indicating self-protecting biases 40 (Fig. 2 ). Neuroimaging studies revealed that, being rejected based only on one’s profile pictures resulted in increased activity in the medial frontal cortex, in both adults 41 and children 42 , and studies in adolescents showed enhanced pupil dilation, a response to greater cognitive load and emotional intensity, to rejection 43 .