Essays Moral, Political, Literary (LF ed.)

- David Hume (author)

- Eugene F. Miller (editor)

This edition of Hume’s much neglected philosophical essays contains the thirty-nine essays included in Essays, Moral, and Literary , that made up Volume I of the 1777 posthumous Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects . It also includes ten essays that were withdrawn or left unpublished by Hume for various reasons. The two most important were deemed too controversial for the religious climate of his time.

- EBook PDF This text-based PDF or EBook was created from the HTML version of this book and is part of the Portable Library of Liberty.

- Facsimile PDF This is a facsimile or image-based PDF made from scans of the original book.

Essays Moral, Political, Literary, edited and with a Foreword, Notes, and Glossary by Eugene F. Miller, with an appendix of variant readings from the 1889 edition by T.H. Green and T.H. Grose, revised edition (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund 1987).

The copyright to this edition, in both print and electronic forms, is held by Liberty Fund, Inc.

- Philosophy, Psychology, and Religion

Related Collections:

- Political Theory

- Classics of Liberty

- Books Published by Liberty Fund

Related People

Politics & Liberty

Critical Responses

Paul Guyer engages Immanuel Kant’s responses to David Hume’s work—Kant critiques Hume while also being influenced by his metaphysical claims.

Connected Readings

Dennis C. Rasmussen

Rasmussen’s book covers the fascinating personal and ideological relationship between David Hume and Adam Smith.

Dennis Rasmussen and Russ Roberts

EconTalk Podcast

Political Scientist Dennis Rasmussen of Tufts University and author of The Infidel and the Professor talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about his book–the intellectual and personal connections between two of the greatest thinkers of all time, David Hume and Adam Smith.

Hume, a famous historian in his time, wrote of the transition in English history from a government of will to a government of law.

Liberty Matters

Nicholas Capaldi, Daniel B. Klein, Andrew Sabl, and Mark E. Yellin

This Liberty Matters forum outlines David Hume’s ambitious “Project” with a list of 8 “theses”, the last of which states that “Liberty is the Central Theme.” Given its unique history, England was able to preserve and elaborate this insight in large part because of its inherent disposition to…

Laurence L. Bongie

Laurence Bongie’s book explores Hume’s early conception of skepticism, predating that of Edmund Burke’s conservative work.

Liberty Classic

Max Skjönsberg

Hume was a quintessential eighteenth-century man of letters, as evidenced by his Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary.

- Liberty Fund

- Adam Smith Works

- Law & Liberty

- Browse by Author

- Browse by Topic

- Browse by Date

- Search EconLog

- Latest Episodes

- Browse by Guest

- Browse by Category

- Browse Extras

- Search EconTalk

- Latest Articles

- Liberty Classics

- Search Articles

- Books by Date

- Books by Author

- Search Books

- Browse by Title

- Biographies

- Search Encyclopedia

- #ECONLIBREADS

- College Topics

- High School Topics

- Subscribe to QuickPicks

- Search Guides

- Search Videos

- Library of Law & Liberty

- Home /

ECONLIB Books

Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary

By david hume.

DAVID HUME’S greatness was recognized in his own time, as it is today, but the writings that made Hume famous are not, by and large, the same ones that support his reputation now. Leaving aside his Enquiries, which were widely read then as now, Hume is known today chiefly through his Treatise of Human Nature and his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. The Treatise was scarcely read at all during Hume’s lifetime, however, and the Dialogues was not published until after his death. Conversely, most readers today pay little attention to Hume’s various books of essays and to his History of England, but these are the works that were read avidly by his contemporaries. If one is to get a balanced view of Hume’s thought, it is necessary to study both groups of writings. If we should neglect the essays or the History, then our view of Hume’s aims and achievements is likely to be as incomplete as that of his contemporaries who failed to read the Treatise or the Dialogues. … [From the Foreword by Eugene F. Miller]

Translator/Editor

Eugene F. Miller, ed.

First Pub. Date

Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, Inc. Liberty Fund, Inc.

Publication date details: Part I: 1742. Part II ( Political Discourses): 1752. Combined: 1777. Includes Political Discourses (1752), "My Own Life," by David Hume, and a letter by Adam Smith.

Portions of this edited edition are under copyright. Picture of David Hume courtesy of The Warren J. Samuels Portrait Collection at Duke University.

Table of Contents

- Foreword, by Eugene F. Miller

- Editors Note, by Eugene F. Miller

- Note to the Revised Edition

My Own Life, by David Hume

- Letter from Adam Smith, L.L.D. to William Strahan, Esq.

- Part I, Essay I, OF THE DELICACY OF TASTE AND PASSION

- Part I, Essay II, OF THE LIBERTY OF THE PRESS

- Part I, Essay III, THAT POLITICS MAY BE REDUCED TO A SCIENCE

- Part I, Essay IV, OF THE FIRST PRINCIPLES OF GOVERNMENT

- Part I, Essay V, OF THE ORIGIN OF GOVERNMENT

- Part I, Essay VI, OF THE INDEPENDENCY OF PARLIAMENT

- Part I, Essay VII, WHETHER THE BRITISH GOVERNMENT INCLINES MORE TO ABSOLUTE MONARCHY, OR TO A REPUBLIC

- Part I, Essay VIII, OF PARTIES IN GENERAL

- Part I, Essay IX, OF THE PARTIES OF GREAT BRITAIN

- Part I, Essay X, OF SUPERSTITION AND ENTHUSIASM

- Part I, Essay XI, OF THE DIGNITY OR MEANNESS OF HUMAN NATURE

- Part I, Essay XII, OF CIVIL LIBERTY

- Part I, Essay XIII, OF ELOQUENCE

- Part I, Essay XIV, OF THE RISE AND PROGRESS OF THE ARTS AND SCIENCES

- Part I, Essay XV, THE EPICUREAN

- Part I, Essay XVI, THE STOIC

- Part I, Essay XVII, THE PLATONIST

- Part I, Essay XVIII, THE SCEPTIC

- Part I, Essay XIX, OF POLYGAMY AND DIVORCES

- Part I, Essay XX, OF SIMPLICITY AND REFINEMENT IN WRITING

- Part I, Essay XXI, OF NATIONAL CHARACTERS

- Part I, Essay XXII, OF TRAGEDY

- Part I, Essay XXIII, OF THE STANDARD OF TASTE

- Part II, Essay I, OF COMMERCE

- Part II, Essay II, OF REFINEMENT IN THE ARTS

- Part II, Essay III, OF MONEY

- Part II, Essay IV, OF INTEREST

- Part II, Essay V, OF THE BALANCE OF TRADE

- Part II, Essay VI, OF THE JEALOUSY OF TRADE

- Part II, Essay VII, OF THE BALANCE OF POWER

- Part II, Essay VIII, OF TAXES

- Part II, Essay IX, OF PUBLIC CREDIT

- Part II, Essay X, OF SOME REMARKABLE CUSTOMS

- Part II, Essay XI, OF THE POPULOUSNESS OF ANCIENT NATIONS

- Part II, Essay XII, OF THE ORIGINAL CONTRACT

- Part II, Essay XIII, OF PASSIVE OBEDIENCE

- Part II, Essay XIV, OF THE COALITION OF PARTIES

- Part II, Essay XV, OF THE PROTESTANT SUCCESSION

- Part II, Essay XVI, IDEA OF A PERFECT COMMONWEALTH

- Part III, Essay I, OF ESSAY-WRITING

- Part III, Essay II, OF MORAL PREJUDICES

- Part III, Essay III, OF THE MIDDLE STATION OF LIFE

- Part III, Essay IV, OF IMPUDENCE AND MODESTY

- Part III, Essay V, OF LOVE AND MARRIAGE

- Part III, Essay VI, OF THE STUDY OF HISTORY

- Part III, Essay VII, OF AVARICE

- Part III, Essay VIII, A CHARACTER OF SIR ROBERT WALPOLE

- Part III, Essay IX, OF SUICIDE

- Part III, Essay X, OF THE IMMORTALITY OF THE SOUL

- Variant Readings

by Eugene F. Miller

DAVID HUME’S greatness was recognized in his own time, as it is today, but the writings that made Hume famous are not, by and large, the same ones that support his reputation now. Leaving aside his Enquiries, *1 which were widely read then as now, Hume is known today chiefly through his Treatise of Human Nature *2 and his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. *3 The Treatise was scarcely read at all during Hume’s lifetime, however, and the Dialogues was not published until after his death. Conversely, most readers today pay little attention to Hume’s various books of essays and to his History of England, *4 but these are the works that were read avidly by his contemporaries. If one is to get a balanced view of Hume’s thought, it is necessary to study both groups of writings. If we should neglect the essays or the History, then our view of Hume’s aims and achievements is likely to be as incomplete as that of his contemporaries who failed to read the Treatise or the Dialogues.

The preparation and revision of his essays occupied Hume throughout his adult life. In his late twenties, after completing three books of the Treatise, Hume began to publish essays on moral and political themes. His Essays, Moral and Political was brought out late in 1741 by Alexander Kincaid, Edinburgh’s leading publisher. *5 A second volume of essays appeared under the same title early in 1742, *6 and later that year, a “Second Edition, Corrected” of the first volume was issued. In 1748, three additional essays appeared in a small volume published in Edinburgh and London. *7 That volume is noteworthy as the first of Hume’s works to bear his name and also as the beginning of his association with Andrew Millar as his chief London publisher. These three essays were incorporated into the “Third Edition, Corrected” of Essays, Moral and Political, which Millar and Kincaid published in the same year. In 1752, Hume issued a large number of new essays under the title Political Discourses, a work so successful that a second edition was published before the year was out, and a third in 1754. *8

Early in the 1750s, Hume drew together his various essays, along with other of his writings, in a collection entitled Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects. Volume 1 (1753) of this collection contains the Essays, Moral and Political and Volume 4 (1753-54) contains the Political Discourses. The two Enquiries are reprinted in Volumes 2 and 3. Hume retained the title Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects for subsequent editions of his collected works, but he varied the format and contents somewhat. A new, one-volume edition appeared under this title in 1758, and other four-volume editions in 1760 and 1770. Two-volume editions appeared in 1764, 1767, 1768, 1772, and 1777. The 1758 edition, for the first time, grouped the essays under the heading “Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary” and divided them into Parts I and II. Several new essays, as well as other writings, were added to this collection along the way. *9

As we see, the essays were by no means of casual interest to Hume. He worked on them continually from about 1740 until his death, in 1776. There are thirty-nine essays in the posthumous, 1777, edition of Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary (Volume 1 of Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects ). Nineteen of these date back to the two original volumes of Essays, Moral and Political (1741-42). By 1777, these essays from the original volumes would have gone through eleven editions. Twenty essays were added along the way, eight were deleted, and two would await posthumous publication. Hume’s practice throughout his life was to supervise carefully the publication of his writings and to correct them for new editions. Though gravely ill in 1776, Hume made arrangements for the posthumous publication of his manuscripts, including the suppressed essays “Of Suicide” and “Of the Immortality of the Soul,” and he prepared for his publisher, William Strahan, the corrections for new editions of both his History of England and his Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects. When Adam Smith visited Hume on August 8, 1776, a little more than two weeks before the philosopher’s death on August 25, he found Hume still at work on corrections to the Essays and Treatises. Hume had earlier been reading Lucian’s Dialogues of the Dead, and he speculated in jocular fashion with Smith on excuses that he might give to Charon for not entering his boat. One possibility was to say to him: “Good Charon, I have been correcting my works for a new edition. Allow me a little time, that I may see how the Public receives the alterations.” *10

Hume’s essays were received warmly in Britain, on the Continent, where numerous translations into French, German, and Italian appeared, and in America. In his brief autobiography, My own Life, *11 Hume speaks of his great satisfaction with the public’s reception of the essays. The favorable response to the first volume of Essays, Moral and Political made him forget entirely his earlier disappointment over the public’s indifference to his Treatise of Human Nature, and he was pleased that Political Discourses was received well from the outset both at home and abroad. When Hume accompanied the Earl of Hertford to Paris in 1763 for a stay of twenty-six months as Secretary of the British Embassy and finally as Chargé d’Affaires, he discovered that his fame there surpassed anything he might have expected. He was loaded with civilities “from men and women of all ranks and stations.” Fame was not the only benefit that Hume enjoyed from his publications. By the 1760s, “the copy-money given me by the booksellers, much exceeded any thing formerly known in England; I was become not only independent, but opulent.”

Hume’s essays continued to be read widely for more than a century after his death. Jessop lists sixteen editions or reprintings of Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects that appeared between 1777 and 1894. *12 (More than fifty editions or reprintings of the History are listed for the same period.) The Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary were included as Volume 3 of The Philosophical Works of David Hume (Edinburgh, 1825; reprinted in 1826 and 1854) and again as Volume 3 of a later edition by T. H. Green and T. H. Grose, also entitled The Philosophical Works of David Hume (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1874-75; vol. 3, reprinted in 1882, 1889, 1898, 1907, and 1912). Some separate editions of the Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary were published as well, including the one by “The World’s Classics” (London, 1903; reprinted in 1904).

These bibliographical details are important because they show how highly the essays were regarded by Hume himself and by many others up to the present century. Over the past seventy years, however, the essays have been overshadowed, just as the History has been, by other of Hume’s writings. Although some recent studies have drawn attention once again to the importance of Hume’s Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary, *13 the work itself has long been difficult to locate in a convenient edition. Some of the essays have been included in various collections, *14 but, leaving aside the present edition, no complete edition of the Essays has appeared since the early part of the century, save for a reprinting of the 1903 World’s Classics edition *15 and expensive reproductions of Green and Grose’s four-volume set of the Philosophical Works. In publishing this new edition of the Essays —along with its publication, in six volumes, of the History of England *16 —Liberty Fund has made a neglected side of Hume’s thought accessible once again to the modern reader.

Many years after Hume’s death, his close friend John Home wrote a sketch of Hume’s character, in the course of which he observed: “His Essays are at once popular and philosophical, and contain a rare and happy union of profound Science and fine writing.” *17 This observation indicates why Hume’s essays were held in such high esteem by his contemporaries and why they continue to deserve our attention today. The essays are elegant and entertaining in style, but thoroughly philosophical in temper and content. They elaborate those sciences—morals, politics, and criticism—for which the Treatise of Human Nature lays a foundation. It was not simply a desire for fame that led Hume to abandon the Treatise and seek a wider audience for his thought. He acted in the belief that commerce between men of letters and men of the world worked to the benefit of both. Hume thought that philosophy itself was a great loser when it remained shut up in colleges and cells and secluded from the world and good company. Hume’s essays do not mark an abandonment of philosophy, as some have maintained, *18 but rather an attempt to improve it by having it address the concerns of common life.

Eugene F. Miller is Professor of Political Science at the University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia

Editor’s Note

Part I, Essay I

Hume Texts Online

Essays, moral, political, and literary, part 1 (1741, 1777).

- Of the Delicacy of Taste and Passion (1741, 1777)

- Of the Liberty of the Press (1741, 1777)

- That Politics may be reduced to a Science (1741, 1777)

- Of the First Principles of Government (1741, 1777)

- Of the Origin of Government (1777)

- Of the Independency of Parliament (1741, 1777)

- Whether the British Government inclines more to Absolute Monarchy, or to a Republic (1741, 1777)

- Of Parties in General (1741, 1777)

- Of the Parties of Great Britain (1741, 1777)

- Of Superstition and Enthusiasm (1741, 1777)

- Of the Dignity or Meanness of Human Nature (1741, 1777)

- Of Civil Liberty (1741, 1777)

- Of Eloquence (1742, 1777)

- Of the Rise and Progress of the Arts and Sciences (1742, 1777)

- The Epicurean (1742, 1777)

- The Stoic (1742, 1777)

- The Platonist (1742, 1777)

- The Sceptic (1742, 1777)

- Of Polygamy and Divorces (1742, 1777)

- Of Simplicity and Refinement in Writing (1742, 1777)

- Of National Characters (1748, 1777)

- Of Tragedy (1757, 1777)

- Of the Standard of Taste (1757, 1777)

Essays Moral, Political, Literary

No related resources

Introduction

These are two essays excerpted from a larger work in which David Hume covers much ground discussing everything from the arts, to philosophy, to practical politics, religion, and economics. The essays were published in several parts throughout the 1740s and 1750s, culminating in a 1758 edition that first grouped the essays together under their current title, Essays, Moral, Political, Literary (Original title: Political Discourses ), with Hume continuing to add essays until he died in 1776. Unlike A Treatise of Human Nature, these essays were very popular with Hume’s contemporary readers.

The two pieces chosen here are from his political economic writings. Hume is responding to a philosophy common in the time of empire—mercantilism. This economic policy was used by France, Portugal, Britain, and as Alexander Hamilton’s “Report on Manufactures” shows (Document 14), also the United States. Thomas Mun describes the philosophy in detail, but the idea was that countries should export more than they import to obtain an overbalance of trade. In talking about the jealousy of trade and the balance of trade, Hume discusses what we today call “economic nationalism.”

These essays, in particular “Of the Balance of Trade” and two others, “Of Interest” and “Of Money,” were influential for Adam Smith (Documents 9-12), and he referred to them in lectures to students on jurisprudence. Benjamin Franklin called Hume’s essay “Of the Jealousy of Trade [Commerce]” “excellent,” and Hume told Franklin that he was America’s “first philosopher” and “first great man of letters.” (see Hanley 2002 in recommended readings).

It is very usual, in nations ignorant of the nature of commerce, to prohibit the exportation of commodities, and to preserve among themselves whatever they think valuable and useful. They do not consider, that, in this prohibition, they act directly contrary to their intention; and that the more is exported of any commodity, the more will be raised at home, of which they themselves will always have the first offer.

It is well known to the learned, that the ancient laws of Athens rendered the exportation of figs criminal; that being supposed a species of fruit so excellent in Attica, that the Athenians deemed it too delicious for the palate of any foreigner. And in this ridiculous prohibition they were so much in earnest, that informers were thence called sycophants among them, from two Greek words, which signify figs and discoverer. There are proofs in many old acts of parliament of the same ignorance in the nature of commerce, particularly in the reign of Edward III. And to this day, in France, the exportation of corn is almost always prohibited; in order, as they say, to prevent famines; though it is evident, that nothing contributes more to the frequent famines, which so much distress that fertile country.

The same jealous fear, with regard to money, has also prevailed among several nations; and it required both reason and experience to convince any people, that these prohibitions serve to no other purpose than to raise the exchange against them, and produce a still greater exportation.

These errors, one may say, are gross and palpable: But there still prevails, even in nations well acquainted with commerce, a strong jealousy with regard to the balance of trade, and a fear, that all their gold and silver may be leaving them. This seems to me, almost in every case, a groundless apprehension; and I should as soon dread, that all our springs and rivers should be exhausted, as that money should abandon a kingdom where there are people and industry. Let us carefully preserve these latter advantages; and we need never be apprehensive of losing the former.

It is easy to observe, that all calculations concerning the balance of trade are founded on very uncertain facts and suppositions. The custom-house books are allowed to be an insufficient ground of reasoning; nor is the rate of exchange much better; unless we consider it with all nations, and know also the proportions of the several sums remitted; which one may safely pronounce impossible. Every man, who has ever reasoned on this subject, has always proved his theory, whatever it was, by facts and calculations, and by an enumeration of all the commodities sent to all foreign kingdoms…

Nothing can be more entertaining on this head than Dr. Swift; [1] an author so quick in discerning the mistakes and absurdities of others. He says, in his short view of the state of Ireland, that the whole cash of that kingdom formerly amounted but to 500,000 l.; that out of this the Irish remitted every year a neat million to England, and had scarcely any other source from which they could compensate themselves, and little other foreign trade than the importation of French wines, for which they paid ready money. The consequence of this situation, which must be owned to be disadvantageous, was, that, in a course of three years, the current money of Ireland, from 500,000 l. was reduced to less than two. And at present, I suppose, in a course of 30 years it is absolutely nothing. Yet I know not how, that opinion of the advance of riches in Ireland, which gave the Doctor so much indignation, seems still to continue, and gain ground with everybody.

In short, this apprehension of the wrong balance of trade, appears of such a nature, that it discovers itself, wherever one is out of humor with the ministry, or is in low spirits; and as it can never be refuted by a particular detail of all the exports, which counterbalance the imports, it may here be proper to form a general argument, that may prove the impossibility of this event, as long as we preserve our people and our industry.

Suppose four-fifths of all the money in Great Britain to be annihilated in one night, and the nation reduced to the same condition, with regard to specie, as in the reigns of the Harrys and Edwards, what would be the consequence? Must not the price of all labor and commodities sink in proportion, and everything be sold as cheap as they were in those ages? What nation could then dispute with us in any foreign market, or pretend to navigate or to sell manufactures at the same price, which to us would afford sufficient profit? In how little time, therefore, must this bring back the money which we had lost, and raise us to the level of all the neighboring nations? Where, after we have arrived, we immediately lose the advantage of the cheapness of labor and commodities; and the farther flowing in of money is stopped by our fulness and repletion.

Again, suppose, that all the money of Great Britain were multiplied fivefold in a night, must not the contrary effect follow? Must not all labor and commodities rise to such an exorbitant height, that no neighboring nations could afford to buy from us; while their commodities, on the other hand, became comparatively so cheap, that, in spite of all the laws which could be formed, they would be run in upon us, and our money flow out; till we fall to a level with foreigners, and lose that great superiority of riches, which had laid us under such disadvantages?

Now, it is evident, that the same causes, which would correct these exorbitant inequalities, were they to happen miraculously, must prevent their happening in the common course of nature, and must forever, in all neighboring nations, preserve money nearly proportionable to the art and industry of each nation. All water, wherever it communicates, remains always at a level. Ask naturalists the reason; they tell you, that, were it to be raised in any one place, the superior gravity of that part not being balanced, must depress it, till it meet a counterpoise; and that the same cause, which redresses the inequality when it happens, must forever prevent it, without some violent external operation. . . .

Can one imagine, that it had ever been possible, by any laws, or even by any art or industry, to have kept all the money in Spain, which the galleons have brought from the Indies? Or that all commodities could be sold in France for a tenth of the price which they would yield on the other side of the Pyrenees, without finding their way thither, and draining from that immense treasure? What other reason, indeed, is there, why all nations, at present, gain in their trade with Spain and Portugal; but because it is impossible to heap up money, more than any fluid, beyond its proper level? The sovereigns of these countries have shown, that they wanted not inclination to keep their gold and silver to themselves, had it been in any degree practicable.

But as any body of water may be raised above the level of the surrounding element, if the former has no communication with the latter; so in money, if the communication be cut off, by any material or physical impediment, (for all laws alone are ineffectual) there may, in such a case, be a very great inequality of money. Thus the immense distance of China, together with the monopolies of our India companies, obstructing the communication, preserve in Europe the gold and silver, especially the latter, in much greater plenty than they are found in that kingdom. But, notwithstanding this great obstruction, the force of the causes abovementioned is still evident. The skill and ingenuity of Europe in general surpasses perhaps that of China, with regard to manual arts and manufactures; yet are we never able to trade thither without great disadvantage. And were it not for the continual recruits, which we receive from America, money would soon sink in Europe, and rise in China, till it came nearly to a level in both places. Nor can any reasonable man doubt, but that industrious nation, were they as near us as Poland or Barbary, would drain us of the overplus of our specie, and draw to themselves a larger share of the West Indian treasures. We need not have recourse to a physical attraction, in order to explain the necessity of this operation. There is a moral attraction, arising from the interests and passions of men, which is full as potent and infallible.

How is the balance kept in the provinces of every kingdom among themselves, but by the force of this principle, which makes it impossible for money to lose its level, and either to rise or sink beyond the proportion of the labor and commodities which are in each province?… It was a common apprehension in England, before the union, as we learn from L’abbe du Bos, [2] that Scotland would soon drain them of their treasure, were an open trade allowed; and on the other side the Tweed a contrary apprehension prevailed: With what justice in both, time has shown.

What happens in small portions of mankind, must take place in greater. The provinces of the Roman empire, no doubt, kept their balance with each other, and with Italy, independent of the legislature; as much as the several counties of Great Britain, or the several parishes of each county. And any man who travels over Europe at this day, may see, by the prices of commodities, that money, in spite of the absurd jealousy of princes and states, has brought itself nearly to a level; and that the difference between one kingdom and another is not greater in this respect, than it is often between different provinces of the same kingdom. Men naturally flock to capital cities, sea-ports, and navigable rivers. There we find more men, more industry, more commodities, and consequently more money; but still the latter difference holds proportion with the former, and the level is preserved.

Our jealousy and our hatred of France are without bounds; and the former sentiment, at least, must be acknowledged reasonable and well-grounded. These passions have occasioned innumerable barriers and obstructions upon commerce, where we are accused of being commonly the aggressors. But what have we gained by the bargain? We lost the French market for our woolen manufactures, and transferred the commerce of wine to Spain and Portugal, where we buy worse liquor at a higher price. There are few Englishmen who would not think their country absolutely ruined, were French wines sold in England so cheap and in such abundance as to supplant, in some measure, all ale, and home-brewed liquors: But would we lay aside prejudice, it would not be difficult to prove, that nothing could be more innocent, perhaps advantageous. Each new acre of vineyard planted in France, in order to supply England with wine, would make it requisite for the French to take the produce of an English acre, sown in wheat or barley, in order to subsist themselves; and it is evident, that we should thereby get command of the better commodity.

From these principles we may learn what judgment we ought to form of those numberless bars, obstructions, and imposts, which all nations of Europe, and none more than England, have put upon trade; from an exorbitant desire of amassing money, which never will heap up beyond its level, while it circulates; or from an ill-grounded apprehension of losing their specie, which never will sink below it. Could anything scatter our riches, it would be such impolitic contrivances. But this general ill effect, however, results from them, that they deprive neighboring nations of that free communication and exchange which the Author of the world has intended, by giving them soils, climates, and geniuses, so different from each other.

Our modern politics embrace the only method of banishing money, the using of paper-credit; they reject the only method of amassing it, the practice of hoarding; and they adopt a hundred contrivances, which serve to no purpose but to check industry, and rob ourselves and our neighbors of the common benefits of art and nature.

All taxes, however, upon foreign commodities, are not to be regarded as prejudicial or useless, but those only which are founded on the jealousy above-mentioned. A tax on German linen encourages home manufactures, and thereby multiplies our people and industry. A tax on brandy increases the sale of rum, and supports our southern colonies. And as it is necessary, that imposts should be levied, for the support of government, it may be thought more convenient to lay them on foreign commodities, which can easily be intercepted at the port, and subjected to the impost. We ought, however, always to remember the maxim of Dr. Swift, That, in the arithmetic of the customs, two and two make not four, but often make only one. It can scarcely be doubted, but if the duties on wine were lowered to a third, they would yield much more to the government than at present: Our people might thereby afford to drink commonly a better and more wholesome liquor; and no prejudice would ensue to the balance of trade, of which we are so jealous. The manufacture of ale beyond the agriculture is but inconsiderable, and gives employment to few hands. The transport of wine and corn would not be much inferior.

But are there not frequent instances, you will say, of states and kingdoms, which were formerly rich and opulent, and are now poor and beggarly? Has not the money left them, with which they formerly abounded? I answer, If they lose their trade, industry, and people, they cannot expect to keep their gold and silver: For these precious metals will hold proportion to the former advantages. When Lisbon and Amsterdam got the East-India trade from Venice and Genoa, they also got the profits and money which arose from it. Where the seat of government is transferred, where expensive armies are maintained at a distance, where great funds are possessed by foreigners; there naturally follows from these causes a diminution of the specie. But these, we may observe, are violent and forcible methods of carrying away money, and are in time commonly attended with the transport of people and industry. But where these remain, and the drain is not continued, the money always finds its way back again, by a hundred canals, of which we have no notion or suspicion. . . .

In short, a government has great reason to preserve with care its people and its manufactures. Its money, it may safely trust to the course of human affairs, without fear or jealousy. Or if it ever give attention to this latter circumstance, it ought only to be so far as it affects the former.

ESSAY VI: OF THE JEALOUSY OF TRADE

Having endeavored to remove one species of ill-founded jealousy, which is so prevalent among commercial nations, it may not be amiss to mention another, which seems equally groundless. Nothing is more usual, among states which have made some advances in commerce, than to look on the progress of their neighbors with a suspicious eye, to consider all trading states as their rivals, and to suppose that it is impossible for any of them to flourish, but at their expense. In opposition to this narrow and malignant opinion, I will venture to assert, that the increase of riches and commerce in any one nation, instead of hurting, commonly promotes the riches and commerce of all its neighbors; and that a state can scarcely carry its trade and industry very far, where all the surrounding states are buried in ignorance, sloth, and barbarism.

It is obvious, that the domestic industry of a people cannot be hurt by the greatest prosperity of their neighbors; and as this branch of commerce is undoubtedly the most important in any extensive kingdom, we are so far removed from all reason of jealousy. But I go farther, and observe, that where an open communication is preserved among nations, it is impossible but the domestic industry of every one must receive an increase from the improvements of the others. Compare the situation of Great Britain at present, with what it was two centuries ago. All the arts both of agriculture and manufactures were then extremely rude and imperfect. Every improvement, which we have since made, has arisen from our imitation of foreigners; and we ought so far to esteem it happy, that they had previously made advances in arts and ingenuity. But this intercourse is still upheld to our great advantage: Notwithstanding the advanced state of our manufactures, we daily adopt, in every art, the inventions and improvements of our neighbors. The commodity is first imported from abroad, to our great discontent, while we imagine that it drains us of our money: Afterwards, the art itself is gradually imported, to our visible advantage: Yet we continue still to repine, that our neighbors should possess any art, industry, and invention; forgetting that, had they not first instructed us, we should have been at present barbarians; and did they not still continue their instructions, the arts must fall into a state of languor, and lose that emulation and novelty, which contribute so much to their advancement.

The increase of domestic industry lays the foundation of foreign commerce. Where a great number of commodities are raised and perfected for the home-market, there will always be found some which can be exported with advantage. But if our neighbors have no art or cultivation, they cannot take them; because they will have nothing to give in exchange. In this respect, states are in the same condition as individuals. A single man can scarcely be industrious, where all his fellow-citizens are idle. The riches of the several members of a community contribute to increase my riches, whatever profession I may follow. They consume the produce of my industry, and afford me the produce of theirs in return.

Nor needs any state entertain apprehensions, that their neighbors will improve to such a degree in every art and manufacture, as to have no demand from them. Nature, by giving a diversity of geniuses, climates, and soils, to different nations, has secured their mutual intercourse and commerce, as long as they all remain industrious and civilized. Nay, the more the arts increase in any state, the more will be its demands from its industrious neighbors. The inhabitants, having become opulent and skillful, desire to have every commodity in the utmost perfection; and as they have plenty of commodities to give in exchange, they make large importations from every foreign country. The industry of the nations, from whom they import, receives encouragement: Their own is also increased, by the sale of the commodities which they give in exchange.

But what if a nation has any staple commodity, such as the woolen manufacture is in England? Must not the interfering of our neighbors in that manufacture be a loss to us? I answer, that, when any commodity is denominated the staple of a kingdom, it is supposed that this kingdom has some peculiar and natural advantages for raising the commodity; and if, notwithstanding these advantages, they lose such a manufacture, they ought to blame their own idleness, or bad government, not the industry of their neighbors. It ought also to be considered, that, by the increase of industry among the neighboring nations, the consumption of every particular species of commodity is also increased; and though foreign manufactures interfere with them in the market, the demand for their product may still continue, or even increase. And should it diminish, ought the consequence to be esteemed so fatal? If the spirit of industry be preserved, it may easily be diverted from one branch to another; and the manufacturers of wool, for instance, be employed in linen, silk, iron, or any other commodities, for which there appears to be a demand. We need not apprehend, that all the objects of industry will be exhausted, or that our manufacturers, while they remain on an equal footing with those of our neighbors, will be in danger of wanting employment. The emulation among rival nations serves rather to keep industry alive in all of them: And any people is happier who possess a variety of manufactures, than if they enjoyed one single great manufacture, in which they are all employed. Their situation is less precarious; and they will feel less sensibly those revolutions and uncertainties, to which every particular branch of commerce will always be exposed.

The only commercial state, that ought to dread the improvements and industry of their neighbors, is such a one as the Dutch, who enjoying no extent of land, nor possessing any number of native commodities, flourish only by their being the brokers, and factors, and carriers of others. Such a people may naturally apprehend, that, as soon as the neighboring states come to know and pursue their interest, they will take into their own hands the management of their affairs, and deprive their brokers of that profit, which they formerly reaped from it. But though this consequence may naturally be dreaded, it is very long before it takes place; and by art and industry it may be warded off for many generations, if not wholly eluded. The advantage of superior stocks and correspondence is so great, that it is not easily overcome; and as all the transactions increase by the increase of industry in the neighboring states, even a people whose commerce stands on this precarious basis, may at first reap a considerable profit from the flourishing condition of their neighbors. The Dutch, having mortgaged all their revenues, make not such a figure in political transactions as formerly; but their commerce is surely equal to what it was in the middle of the last century, when they were reckoned among the great powers of Europe.

Were our narrow and malignant politics to meet with success, we should reduce all our neighboring nations to the same state of sloth and ignorance that prevails in Morocco and the coast of Barbary. But what would be the consequence? They could send us no commodities: They could take none from us: Our domestic commerce itself would languish for want of emulation, example, and instruction: And we ourselves should soon fall into the same abject condition, to which we had reduced them. I shall therefore venture to acknowledge, that, not only as a man, but as a British subject, I pray for the flourishing commerce of Germany, Spain, Italy, and even France itself. I am at least certain, that Great Britain, and all those nations, would flourish more, did their sovereigns and ministers adopt such enlarged and benevolent sentiments towards each other.

- 1. Hume refers here to Jonathan Swift (1667-1745), an Irish satirist who is famous for writing Gulliver’s Travels.

- 2. Jean-Baptiste DuBos (1670-1742) was a French author and a member of the French Academy who interacted with many French Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire, Montesquieu (Document 6), and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Document 7).

Second Discourse

Principles of law and polity, applied to the government of the british colonies in america, see our list of programs.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Check out our collection of primary source readers

Our Core Document Collection allows students to read history in the words of those who made it. Available in hard copy and for download.

- Essays: Moral, Political, and Literary

In this Book

- Published by: Liberty Fund

Table of Contents

- Title Page, Copyright

- pp. xi-xviii

- EDITOR'S NOTE

- pp. xix-xxvii

- Note to the Revised Edition

- pp. xxviii-30

- MY OWN LIFE

- pp. xxxi-xli

- LETTER FROM ADAM SMITH, LL.D. TO WILLIAM STRAHAN, ESQ

- pp. xliii-xlix

- pp. 111-137

- pp. 138-145

- pp. 146-154

- pp. 155-158

- ESSAY XVIII

- pp. 159-180

- pp. 181-190

- pp. 191-196

- pp. 197-215

- pp. 216-225

- ESSAY XXIII

- pp. 226-249

- pp. 251-304

- pp. 253-267

- pp. 268-280

- pp. 281-294

- pp. 295-307

- pp. 308-326

- pp. 327-331

- pp. 332-341

- pp. 342-348

- pp. 349-365

- pp. 366-376

- pp. 377-464

- pp. 465-487

- pp. 488-492

- pp. 493-501

- pp. 502-511

- pp. 512-529

- ESSAYS WITHDRAWN AND UNPUBLISHED

- pp. 531-584

- pp. 533-537

- pp. 538-544

- pp. 545-551

- pp. 552-556

- pp. 557-562

- pp. 563-568

- pp. 569-573

- pp. 574-576

- pp. 577-589

- pp. 590-598

- VARIANT READINGS

- pp. 599-602

- VARIANT READINGS TO PART I

- pp. 603-630

- VARIANT READINGS TO PART II

- pp. 631-647

- VARIANT READINGS TO ESSAYS WITHDRAWN AND UNPUBLISHED

- pp. 648-700

- pp. 649-659

- pp. 661-683

Additional Information

Project muse mission.

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

David Hume: Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary

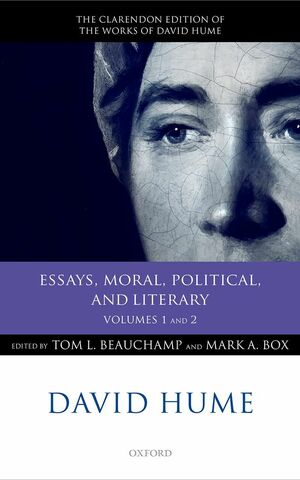

David Hume, David Hume: Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary , 2 Vols., Tom L. Beauchamp and Mark A. Box (eds.), Clarendon Press, 2021, 1200pp., $230.00 (hbk), ISBN 9780198847090.

Reviewed by Paul Russell, Lund University

Looking across the distance of time to admire David Hume’s contributions and achievements, we are presented not with a single peak but with a range of towering peaks. From the perspective of contemporary philosophy, it is Hume’s first and lengthiest work, A Treatise of Human Nature , published in 1739–40, that dominates the horizon. There are, nevertheless, other peaks standing nearby. This includes both the Enquiries , on human understanding (1748) and on morals (1751) respectively, in which Hume “recasts” his Treatise . It also includes Hume’s posthumously published Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779). Although these works are generally regarded as containing the core of Hume’s philosophy, they are by no means his only great works. There is also Hume’s History of England , published in six volumes between 1754 and 1762—a work that did much to advance Hume’s reputation among his own contemporaries. To this we might add Hume’s Dissertation on the Passions and his Natural History of Religion , which were first published along with two other essays in 1757. With all these works in view it is easy to understand why many readers may overlook or neglect another set of works that stand beside them, namely Hume’s various Essays , which were published between 1741 and 1777. No account of Hume’s achievements is complete without a proper appreciation of his Essays .

In his autobiographical essay “My Own Life” Hume, famously, confesses that “love of literary fame” was his “ruling passion”. Some commentators—most notably John Herman Randall—have used these remarks to suggest that Hume, for all his considerable philosophical ability, was motivated by nothing better than fame and money (1962, 631). The striking change of style and content found in Hume’s Essays , which clearly aim at a wider and more popular audience, could be construed in these unflattering terms but few would now accept this account. There is, nevertheless, no denying that the disappointing reception of the Treatise encouraged Hume to radically rethink and revise his writings and the audience that he aimed to reach. From the beginning, Hume was well aware of the “common prejudice” against “metaphysics” and “abstruse philosophy” (T, Intro 3). At the beginning of Book III of the Treatise , which was published in late 1740, Hume admits that the “abstruse philosophy” contained in the Treatise is unlikely to be well received “in an age, wherein the greatest part of men seem agreed to convert reading into an amusement, and to reject every thing that requires any considerable degree of attention to be comprehended” (T, 3.1.1). Shortly after these remarks went into print, Hume published the first edition of his Essays .

In “Of Essay Writing”—an early essay that was withdrawn after publication in 1742—Hume laments that learning has been “shut up in the Colleges and Cells, and secluded from the World and Good Company” (ESY, I, 3). It was Hume’s aim to bridge this gap between “the learned and conversible World”—something that his Treatise had clearly failed to do. In the opening remarks to his first Enquiry Hume returns to this theme concerning the schism between the “learned world” and “common life”. There are, he notes, “two different species of philosophy”, the “easy and obvious” and “the abstruse” (EU; 1. 2–3). The Treatise , evidently, falls heavily on the side of “the abstruse” and “abstract” philosophy, hence its lack of influence and success. In contrast with this, the easy philosophy is engaged with common life and has some prospect of being able to influence both our sentiments and our conduct. It does not follow from this, however, that we should altogether abandon the abstruse philosophy. On the contrary, the abstruse philosophy ensures that all our reasonings concerning human life are sufficiently exact and precise. What is required, therefore, is some middle ground or balance to be struck between these two different species of philosophy (EU, 1. 5–12). If the vulnerability of abstruse philosophy is that it is rendered dull and irrelevant, the vulnerability of the easy philosophy is that it becomes “shallow” and has nothing new to say to us. “An author”, Hume notes elsewhere, “is little to be valued, who tells us nothing but what we can learn from every coffee-house conversation” (ESY, 1, 199).

Finding the right balance between these two species of philosophy is something Hume aims at in his Essays , a number of which were directed primarily at readers of Addison, Steele, and Swift, rather than those of Descartes, Locke and Clarke. Hume was not always able to strike that balance to his own satisfaction. This no doubt explains why he subsequently withdrew a number of his earlier essays on the grounds that they were too “frivolous” and “trivial” (LET, I, 112; I, 168). Perhaps the best known of the early essays that Hume retained is a set of four essays devoted to describing the philosophical characters of four sects of philosophy: the Epicurean, Stoic, Platonic, and Sceptic. These essays show how each of these philosophical characters aim to achieve happiness. Whatever the relative merits of these essays may be, the adjustments that Hume made proved immediately successful and his Essays were “favourably received”. This change in his fortune continued with the publication of the Political Discourses in 1752, which Hume describes as “the only work of [his] that was successful on the first publication” and as being “well received abroad and at home” (1985, xxxvi). The major focus of attention in the Political Discourses is economics, which occupies more than half of the dozen essays contained. Other important essays in this volume include “Of the Populousness of Ancient Nations” and “Idea of a Perfect Commonwealth”, which is indicative of the wide range of Hume’s interests and concerns, and which suggest links with several of his earlier essays relating to politics, history, and other topics of that kind.

With regard to the contemporary value and interest of Hume’s Essays , views about this will vary, depending on the reader and their own individual concerns. In his Advertisement to the 1741 edition of the Essays , Hume advises his readers “not [to] look for any Connexion among these Essays, but [to] consider each of them as a Work apart” (ESY, I, 529). For this reason many readers will come to Hume’s essays with a view to selecting particular essays and ignoring others. Some may focus on his studies relating to economics and commerce, others will focus on the essays concerned with politics and history, and so on. Nor is there any reason to suppose that all the essays are of (equal) value or worth, as plainly Hume’s own assessment and attitude suggests that is not the case. Nevertheless, in the final analysis it is clear that, however uneven these essays may be in quality, there is a range and substance to the whole that justifies our continued interest in this collection, irrespective of their relevance to Hume’s other works and contributions.

Perhaps the most obvious source of contemporary interest in Hume’s Essays is that, both individually and collectively, they shed a great deal of light on Hume’s other works, including the Treatise , the Enquiries, and the Dialogues . Any serious student of Hume’s views on morality, for example, will want to examine his views in “Of the Standard of Taste”. Those who are interested in Hume’s writings relating to religion will need to consider his essay “Of Superstition and Enthusiasm”. Similarly, Hume’s essays on liberty, the original contract, and the idea of a perfect commonwealth are obviously of direct relevance to his views about justice and politics as presented in the Treatise and the Enquiries . It may be argued, in light of this, that despite their stylistic differences and manner of presentation, there are important themes and concerns that not only hold the various essays together but also connect them with the whole corpus of Hume’s writings.

The range and plurality of Hume’s interests and investigations is not evidence of a disjointed and fragmented mind or intellect. On the contrary, the methods and approach that Hume applies to the various topics and subjects he takes up display his commitment to a core philosophical outlook. That outlook has itself several dimensions, including a commitment to a naturalistic understanding of human nature and the various forms of historical and cultural life that it gives rise to. It also reflects a modest optimism about our ability to make sense of our own existence and to free ourselves from forms of illusion, ignorance, and oppression that can only make us miserable. Most importantly, Hume’s Essays manifest a particular form of Enlightenment confidence that we can come to understand ourselves, and improve our condition, without relying on the falsehoods and fantasies of superstition. Each essay, however focused it may be, reflects this underlying philosophical attitude and aspiration, which runs throughout all of Hume’s writings.

The history of Hume’s Essays , and how they evolved and expanded over a period of several decades, is clearly a complex matter. Hume produced nearly fifty essays that were published in eleven editions between 1741 and 1777 (the exact number may vary, depending on what is included or counted). Throughout this process some essays were added, and others deleted. This whole process culminated in the final 1777 edition of Essays, Moral, Political and Literary (Volume I of Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects ), which Hume carefully edited and corrected before he died in 1776. For that edition, eight earlier essays were withdrawn and twenty were added to the original twenty-seven that were published in two volumes in 1741–2. This left the 1777 edition with a total of thirty-nine essays. Two of the Four Dissertations that Hume published in 1757 were included (“Of Tragedy” and “Of the Standard of Taste”), and two were not included (“The Natural History of Religion” and “On the Passions”). [1] Also not included were two essays printed in 1755, in a collection titled Five Dissertations , but were then “suppressed”. [2] These are Hume’s posthumously published essays “Of Suicide” and “Of the Immortality of the Soul”, which were published together under the title Two Essays in London in 1777 without the author’s name or that of the publisher on the title-page. All this makes it clear enough that the editors of any contemporary edition of Hume’s Essays are presented with a large and difficult task when deciding how to select, arrange, and present this material.

The new two volume edition of Hume’s Essays, Moral, Political and Literary , edited by Tom Beauchamp and Mark Box, is the first critical edition. [3] What primarily distinguishes a critical edition is that it collates the copy-text with all other editions and provides a complete record of variations in the texts. Beauchamp and Box provide readers with detailed, informative notes and annotations that describe the variations and revisions that have been made to the Essays published within Hume’s lifetime. They also provide a table that catalogues the contents of the various editions from 1741 to 1771 and several helpful appendixes relating to their publication. The final text of the essays has been carefully edited and annotated. The second volume contains the editors’ extensive annotations, which are both informed and illuminating. All the editorial work has been done with enormous attention to detail and precision.

Beauchamp and Box’s critical edition of Hume’s Essays is the most recent addition to “The Clarendon Edition of the Works of David Hume”. Prior to this edition, Beauchamp has also edited three other works by Hume for the Clarendon Edition: An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (2000); An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals (1998); and A Dissertation on the Passions and The Natural History of Religion (2007). All of these works have been edited and annotated to the same very high standard. Taken together, this is a significant and substantial contribution to Hume scholarship. The only major (philosophical) works by Hume that are not included in the Clarendon Edition, at this time, are Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion and his two “suppressed” essays, on suicide and immortality. Hopefully this gap will be filled in the not too distant future and, when published, will live up to the high standard that Beauchamp and Box have set with the critical edition of Hume’s Essays.

David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature , edited by D.F. Norton and M. Norton. 2 Vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007). Abbreviated as T . This edition includes Hume’s Abstract of a Treatise of Human Nature and his A Letter from a Gentleman to his friend in Edinburgh (1745).

David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding , edited by T. Beauchamp (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000). Abbreviated as EU .

David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, edited by T. Beauchamp (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998).

David Hume, A Dissertation on the Passions / The Natural History of Religion, edited by T. Beauchamp (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007).

David Hume, Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary, edited by T. Beauchamp and M. Box, 2 Vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2021). Abbreviated as ESY.

David Hume, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion and Other Writings , edited by D. Coleman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

David Hume, My Own Life ; first published in 1777, reprinted in David Hume, Essays, Moral, Political and Literary , rev. ed., Eugene F. Miller ed. (Indianapolis: Liberty Classics, 1985), xxxi–xli.

David Hume, Letters of David Hume, edited by J.Y.T. Greig, 2 Vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1932). Abbreviated as LET .

Ernest Mossner, The Life of David Hume, 2 nd ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980).

John H. Randall, The Career of Philosophy; Vol. 1, From the Middle Ages to the Enlightenment (New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1962).

[1] “The Natural History of Religion” and “On the Passions” were published in Vol. II of Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects (Edinburgh, 1777), along with Hume’s two Enquiries .

[2] Details about this are provided in Mossner (1980), Chap. 24.

[3] Prior to the publication of the critical edition of Hume’s Essays the most complete and comprehensive edition was Eugene Miller’s 1985 edition (Indianapolis: Liberty Classics). Miller’s edition includes Hume’s “suppressed” essays on suicide and immortality, which are not included in Beauchamp and Box’s critical edition. Miller’s edition also includes Hume’s “My Own Life”, which is also omitted by Beauchamp and Box (and is not included in any other volume of the Clarendon Edition of Hume’s Works). Miller’s edition remains a useful and reliable edition for the general reader.

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Essays, moral, political, and literary

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

2,908 Views

2 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by Unknown on February 19, 2008

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- Politics & Social Sciences

- Politics & Government

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $7.99 $7.99 FREE delivery: Wednesday, May 1 on orders over $35.00 shipped by Amazon. Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $7.19

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Essays: Moral, Political and Literary Paperback – December 16, 2015

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 74 pages

- Language English

- Publication date December 16, 2015

- Dimensions 6 x 0.17 x 9 inches

- ISBN-10 1522781463

- ISBN-13 978-1522781462

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may deliver to you quickly

Product details

- Publisher : CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (December 16, 2015)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 74 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1522781463

- ISBN-13 : 978-1522781462

- Item Weight : 4 ounces

- Dimensions : 6 x 0.17 x 9 inches

- #12,848 in History & Theory of Politics

About the author

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Essays Moral, Political, Literary (LF ed.) This edition of Hume's much neglected philosophical essays contains the thirty-nine essays included in Essays, Moral, and Literary, that made up Volume I of the 1777 posthumous Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects. It also includes ten essays that were withdrawn or left unpublished by Hume for ...

Essays, moral, political, and literary by Hume, David, 1711-1776, author. Publication date 1987 Topics ... This edition contains the thirty-nine essays included in Essays, Moral, and Literary, that made up Volume I of the 1777 posthumous Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects. It also includes ten essays that were withdrawn or left ...

Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary (1758) is a two-volume compilation of essays by David Hume. [1] Part I includes the essays from Essays, Moral and Political, [2] plus two essays from Four Dissertations. The content of this part largely covers political and aesthetic issues. Part II includes the essays from Political Discourses, [3] most ...

Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary were published as well, including the one by "The World's Classics" (London, 1903; reprinted in 1904). These bibliographical details are important because they show how highly the essays were regarded by Hume himself and by many others up to the present century. Over the past seventy years, however ...

The Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary were included as Volume 3 of The Philosophical Works of David Hume (Edinburgh, 1825; reprinted in 1826 and 1854) and again as Volume 3 of a later edition by T. H. Green and T. H. Grose, also entitled The Philosophical

Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary, Part 1 (1741, 1777) Full Text; Of the Delicacy of Taste and Passion (1741, 1777) Of the Liberty of the Press (1741, 1777) That Politics may be reduced to a Science (1741, 1777) Of the First Principles of Government (1741, 1777) Of the Origin of Government (1777) Of the Independency of Parliament (1741, 1777)

Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary (1758) is a two volume compilation of essays by David Hume. Part I includes the essays from Essays, Moral and Political, plus two essays from Four Dissertations. The content of this part largely covers political and aesthetic issues. Part II includes the essays from Political Discourses, most of which develop economic themes.

As part of the tried and true model of informal essay writing, Hume began publishing his Essays: Moral, Political and Literary in 1741. The majority of these finely honed treatises fall into three distinct areas: political theory, economic theory and aesthetic theory. Interestingly, Hume's was motivated to produce a collection of informal essays given the poor public reception of his more ...

Yet a major part of this definitive collection, the Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary (a volume of near 600 pages, covering three decades of Hume's career as a philosopher) has been largely ignored. The volume has rarely been in print, and the last critical edition was published in 1874-75. With this splendid, but inexpensive, new critical ...

The essays were published in several parts throughout the 1740s and 1750s, culminating in a 1758 edition that first grouped the essays together under their current title, Essays, Moral, Political, Literary (Original title: Political Discourses ), with Hume continuing to add essays until he died in 1776. Unlike A Treatise of Human Nature, these ...

Essays, moral, political and literary by Hume, David, 1711-1776; Green, Thomas Hill, 1836-1882; Grose, Thomas Hodge, 1845-1906. Publication date 1889 Topics Ethics, Modern -- 18th century, Social ethics -- Early works to 1800, Political science -- Early works to 1800 Publisher London : Longmans, Green

This edition contains the thirty-nine essays included in Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary that made up Volume I of the 1777 posthumous Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects. It also includes ten essays that were withdrawn or left unpublished by Hume for various reasons.Eugene F. Miller was Professor of Political Science at the University of Georgia from 1967 until his retirement in 2003.

Essays: Moral, Political, and Literary. This edition contains the thirty-nine essays included in Essays, Moral, and Literary, that made up Volume I of the 1777 posthumous Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects. It also includes ten essays that were withdrawn or left unpublished by Hume for various reasons.

This edition contains the thirty-nine essays included in Essays, Moral, and Literary, that made up Volume I of the 1777 posthumous Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects. It also includes ten essays that were withdrawn or left unpublished by Hume for various reasons. The two most important were deemed too controversial for the religious climate of his time. This revised edition reflects ...

The new two volume edition of Hume's Essays, Moral, Political and Literary, edited by Tom Beauchamp and Mark Box, is the first critical edition. What primarily distinguishes a critical edition is that it collates the copy-text with all other editions and provides a complete record of variations in the texts.

Other articles where Essays, Moral and Political is discussed: David Hume: Early life and works: " But his next venture, Essays, Moral and Political (1741-42), won some success. Perhaps encouraged by this, he became a candidate for the chair of moral philosophy at Edinburgh in 1744. Objectors alleged heresy and even atheism, pointing to the Treatise as evidence (Hume's Autobiography ...

Essays, moral, political, and literary by Hume, David, 1711-1776; Miller, Eugene F., 1935-Publication date 1987 Topics Ethics, Modern, Social ethics, Political science ... Based on the 1777 ed. originally published as v. 1 of Essays and treatises on several subjects Includes bibliographical references and index Addeddate 2008-02-19 12:57:58

This is the first critical edition ever produced of Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary by David Hume, who is widely widely considered to be the most important British philosopher and an author celebrated for his moral, political, historical, and literary works. The editors' Introduction is primarily historical and written for advanced students and scholars from many disciplines.

Page 118 - Political writers have established it as a maxim, that in contriving any system of government, and fixing the several checks and controls of the constitution, every man ought to be supposed a knave, and to have no other end, in all his actions, than private interest.

Essays: Moral, Political and Literary. Paperback - December 16, 2015. David Hume (7 May 1711- 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist, known especially for his philosophical empiricism and skepticism. He is regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of Western philosophy and the ...

Essays: Moral, Political, and Literary, Volume 1 David Hume Full view - 1889. Essays: Moral, Political and Literary David Hume Limited preview - 2007. Essays: Moral, Political and Literary David Hume Limited preview - 2006.