14 Examples of Formative Assessment [+FAQs]

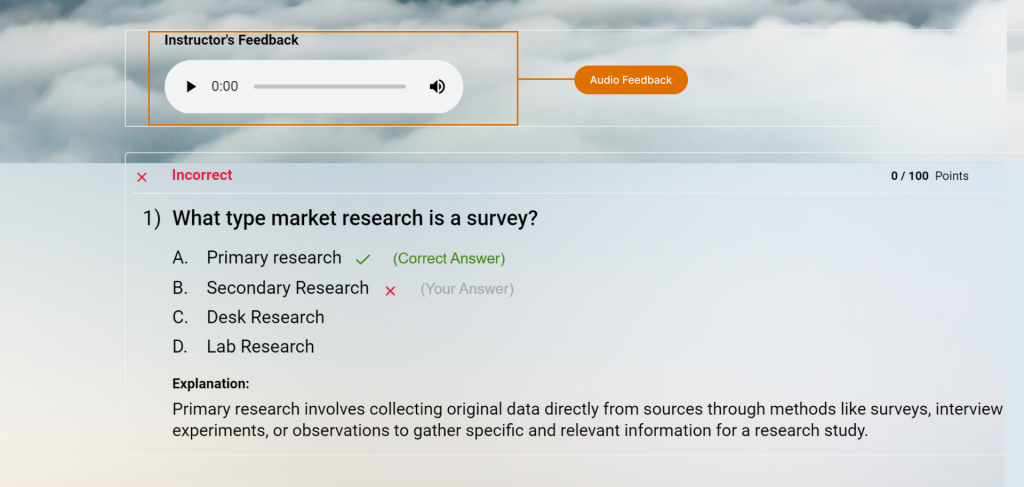

Traditional student assessment typically comes in the form of a test, pop quiz, or more thorough final exam. But as many teachers will tell you, these rarely tell the whole story or accurately determine just how well a student has learned a concept or lesson.

That’s why many teachers are utilizing formative assessments. While formative assessment is not necessarily a new tool, it is becoming increasingly popular amongst K-12 educators across all subject levels.

Curious? Read on to learn more about types of formative assessment and where you can access additional resources to help you incorporate this new evaluation style into your classroom.

What is Formative Assessment?

Online education glossary EdGlossary defines formative assessment as “a wide variety of methods that teachers use to conduct in-process evaluations of student comprehension, learning needs, and academic progress during a lesson, unit, or course.” They continue, “formative assessments help teachers identify concepts that students are struggling to understand, skills they are having difficulty acquiring, or learning standards they have not yet achieved so that adjustments can be made to lessons, instructional techniques, and academic support.”

The primary reason educators utilize formative assessment, and its primary goal, is to measure a student’s understanding while instruction is happening. Formative assessments allow teachers to collect lots of information about a student’s comprehension while they’re learning, which in turn allows them to make adjustments and improvements in the moment. And, the results speak for themselves — formative assessment has been proven to be highly effective in raising the level of student attainment, increasing equity of student outcomes, and improving students’ ability to learn, according to a study from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

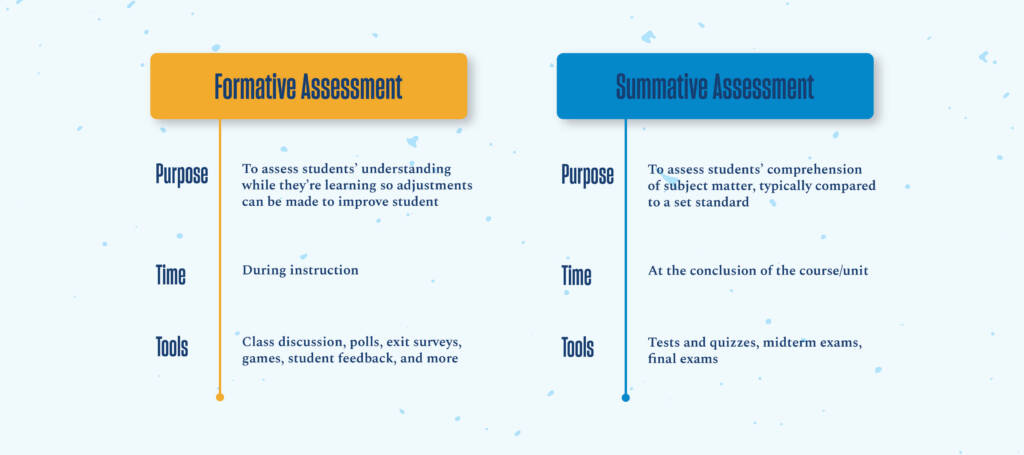

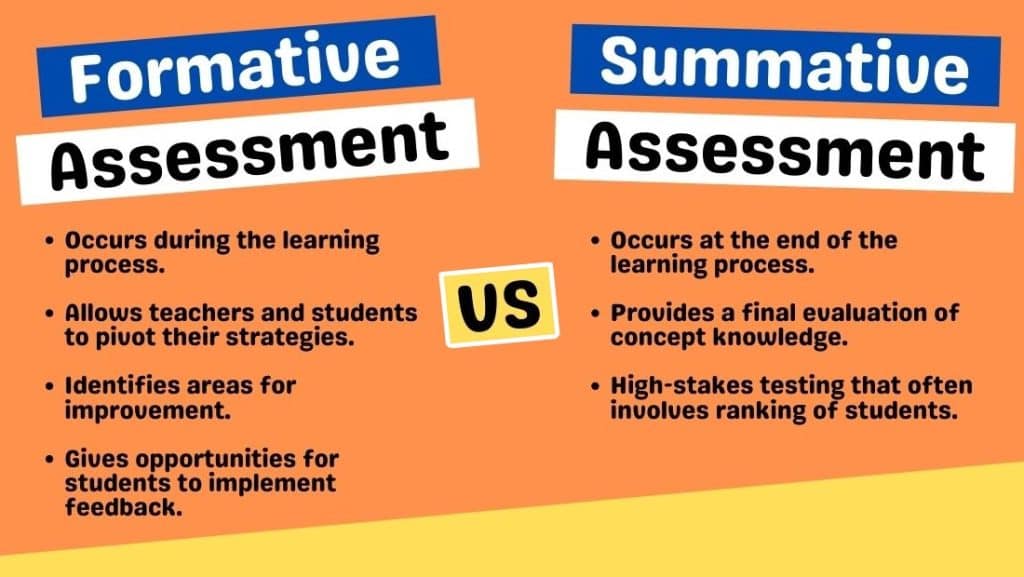

On the flipside of the assessment coin is summative assessments, which are what we typically use to evaluate student learning. Summative assessments are used after a specific instructional period, such as at the end of a unit, course, semester, or even school year. As learning and formative assessment expert Paul Black puts it, “when the cook tastes the soup, that’s formative assessment. When a customer tastes the soup, that’s summative assessment.”

14 Examples of Formative Assessment Tools & Strategies

There are many types of formative assessment tools and strategies available to teachers, and it’s even possible to come up with your own. However, here are some of the most popular and useful formative assessments being used today.

- Round Robin Charts

Students break out into small groups and are given a blank chart and writing utensils. In these groups, everyone answers an open-ended question about the current lesson. Beyond the question, students can also add any relevant knowledge they have about the topic to their chart. These charts then rotate from group to group, with each group adding their input. Once everyone has written on every chart, the class regroups and discusses the responses.

- Strategic Questioning

This formative assessment style is quite flexible and can be used in many different settings. You can ask individuals, groups, or the whole class high-level, open-ended questions that start with “why” or “how.” These questions have a two-fold purpose — to gauge how well students are grasping the lesson at hand and to spark a discussion about the topic.

- Three-Way Summaries

These written summaries of a lesson or subject ask students to complete three separate write-ups of varying lengths: short (10-15 words), medium (30-50 words), and long (75-100). These different lengths test students’ ability to condense everything they’ve learned into a concise statement, or elaborate with more detail. This will demonstrate to you, the teacher, just how much they have learned, and it will also identify any learning gaps.

- Think-Pair-Share

Think-pair-share asks students to write down their answers to a question posed by the teacher. When they’re done, they break off into pairs and share their answers and discuss. You can then move around the room, dropping in on discussions and getting an idea of how well students are understanding.

- 3-2-1 Countdown

This formative assessment tool can be written or oral and asks students to respond to three very simple prompts: Name three things you didn’t know before, name two things that surprised you about this topic, and name one you want to start doing with what you’ve learned. The exact questions are flexible and can be tailored to whatever unit or lesson you are teaching.

- Classroom Polls

This is a great participation tool to use mid-lesson. At any point, pose a poll question to students and ask them to respond by raising their hand. If you have the capability, you can also use online polling platforms and let students submit their answers on their Chromebooks, tablets, or other devices.

- Exit/Admission Tickets

Exit and admission tickets are quick written exercises that assess a student’s comprehension of a single day’s lesson. As the name suggests, exit tickets are short written summaries of what students learned in class that day, while admission tickets can be performed as short homework assignments that are handed in as students arrive to class.

- One-Minute Papers

This quick, formative assessment tool is most useful at the end of the day to get a complete picture of the classes’ learning that day. Put one minute on the clock and pose a question to students about the primary subject for the day. Typical questions might be:

- What was the main point?

- What questions do you still have?

- What was the most surprising thing you learned?

- What was the most confusing aspect and why?

- Creative Extension Projects

These types of assessments are likely already part of your evaluation strategy and include projects like posters and collage, skit performances, dioramas, keynote presentations, and more. Formative assessments like these allow students to use more creative parts of their skillset to demonstrate their understanding and comprehension and can be an opportunity for individual or group work.

Dipsticks — named after the quick and easy tool we use to check our car’s oil levels — refer to a number of fast, formative assessment tools. These are most effective immediately after giving students feedback and allowing them to practice said skills. Many of the assessments on this list fall into the dipstick categories, but additional options include writing a letter explaining the concepts covered or drawing a sketch to visually represent the topic.

- Quiz-Like Games and Polls

A majority of students enjoy games of some kind, and incorporating games that test a student’s recall and subject aptitude are a great way to make formative assessment more fun. These could be Jeopardy-like games that you can tailor around a specific topic, or even an online platform that leverages your own lessons. But no matter what game you choose, these are often a big hit with students.

- Interview-Based Assessments

Interview-based assessments are a great way to get first-hand insight into student comprehension of a subject. You can break out into one-on-one sessions with students, or allow them to conduct interviews in small groups. These should be quick, casual conversations that go over the biggest takeaways from your lesson. If you want to provide structure to student conversations, let them try the TAG feedback method — tell your peer something they did well, ask a thoughtful question, and give a positive suggestion.

- Self Assessment

Allow students to take the rubric you use to perform a self assessment of their knowledge or understanding of a topic. Not only will it allow them to reflect on their own work, but it will also very clearly demonstrate the gaps they need filled in. Self assessments should also allow students to highlight where they feel their strengths are so the feedback isn’t entirely negative.

- Participation Cards

Participation cards are a great tool you can use on-the-fly in the middle of a lesson to get a quick read on the entire classes’ level of understanding. Give each student three participation cards — “I agree,” “I disagree,” and “I don’t know how to respond” — and pose questions that they can then respond to with those cards. This will give you a quick gauge of what concepts need more coverage.

5 REASONS WHY CONTINUING EDUCATION MATTERS FOR EDUCATORS

The education industry is always changing and evolving, perhaps now more than ever. Learn how you can be prepared by downloading our eBook.

List of Formative Assessment Resources

There are many, many online formative assessment resources available to teachers. Here are just a few of the most widely-used and highly recommended formative assessment sites available.

- Arizona State Dept of Education

FAQs About Formative Assessment

The following frequently asked questions were sourced from the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD), a leading education professional organization of more than 100,000 superintendents, principals, teachers, and advocates.

Is formative assessment something new?

No and yes. The concept of measuring a student’s comprehension during lessons has existed for centuries. However, the concept of formative assessment as we understand it didn’t appear until approximately 40 years ago, and has progressively expanded into what it is today.

What makes something a formative assessment?

ASCD characterized formative assessment as “a way for teachers and students to gather evidence of learning, engage students in assessment, and use data to improve teaching and learning.” Their definition continues, “when you use an assessment instrument— a test, a quiz, an essay, or any other kind of classroom activity—analytically and diagnostically to measure the process of learning and then, in turn, to inform yourself or your students of progress and guide further learning, you are engaging in formative assessment. If you were to use the same instrument for the sole purpose of gathering data to report to a district or state or to determine a final grade, you would be engaging in summative assessment.”

Does formative assessment work in all content areas?

Absolutely, and it works across all grade levels. Nearly any content area — language arts, math, science, humanities, and even the arts or physical education — can utilize formative assessment in a positive way.

How can formative assessment support the curriculum?

Formative assessment supports curricula by providing real-time feedback on students’ knowledge levels and comprehension of the subject at hand. When teachers regularly utilize formative assessment tools, they can find gaps in student learning and customize lessons to fill those gaps. After term is over, teachers can use this feedback to reshape their curricula.

How can formative assessment be used to establish instructional priorities?

Because formative assessment supports curriculum development and updates, it thereby influences instructional priorities. Through student feedback and formative assessment, teachers are able to gather data about which instructional methods are most (and least) successful. This “data-driven” instruction should yield more positive learning outcomes for students.

Can formative assessment close achievement gaps?

Formative assessment is ideal because it identifies gaps in student knowledge while they’re learning. This allows teachers to make adjustments to close these gaps and help students more successfully master a new skill or topic.

How can I help my students understand formative assessment?

Formative assessment should be framed as a supportive learning tool; it’s a very different tactic than summative assessment strategies. To help students understand this new evaluation style, make sure you utilize it from the first day in the classroom. Introduce a small number of strategies and use them repeatedly so students become familiar with them. Eventually, these formative assessments will become second nature to teachers and students.

Before you tackle formative assessment, or any new teaching strategy for that matter, consider taking a continuing education course. At the University of San Diego School of Professional and Continuing Education, we offer over 500 courses for educators that can be completed entirely online, and many at your own pace. So no matter what your interests are, you can surely find a course — or even a certificate — that suits your needs.

Be Sure To Share This Article

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Your Salary

Browse over 500+ educator courses and numerous certificates to enhance your curriculum and earn credit toward salary advancement.

Related Posts

Formative Assessment of Teaching

What is formative assessment of teaching.

How do you know if your teaching is effective? How can you identify areas where your teaching can improve? What does it look like to assess teaching?

Formative Assessment

Formative assessment of teaching consists of different approaches to continuously evaluate your teaching. The insight gained from this assessment can support revising your teaching strategies, leading to better outcomes in student learning and experiences. Formative assessment can be contrasted with summative assessment, which is usually part of an evaluative decision-making process. The table below outlines some of the key differences between formative and summative assessment:

By participating in formative assessment, instructors connect with recent developments in the space of teaching and learning, as well as incorporate new ideas into their practice. Developments may include changes in the students we serve, changes in our understanding of effective teaching, and changes in expectations of the discipline and of higher education as a whole.

Formative assessment of teaching ultimately should guide instructors towards using more effective teaching practices. What does effectiveness mean in terms of teaching?

Effectiveness in Teaching

Effective teaching can be defined as teaching that leads to the intended outcomes in student learning and experiences. In this sense, there is no single perfect teaching approach. Effective teaching looks will depend on the stated goals for student learning and experiences. A course that aims to build student confidence in statistical analysis and a course that aims to develop student writing could use very different teaching strategies, and still both be effective at accomplishing their respective goals.

Assessing student learning and experiences is critical to determining if teaching is truly effective in its context. This assessment can be quite complex, but it is doable. In addition to measuring the impacts of your teaching, you may also consider evaluating your teaching as it aligns with best practices for evidence-based teaching especially in the disciplinary and course context or aligns with your intended teaching approach. The table below outlines these three approaches to assessing the effectiveness of your teaching:

What are some strategies that I might try?

There are multiple ways that instructors might begin to assess their teaching. The list below includes approaches that may be done solo, with colleagues, or with the input of students. Instructors may pursue one or more of these strategies at different points in time. With each possible strategy, we have included several examples of the strategy in practice from a variety of institutions and contexts.

Teaching Portfolios

Teaching portfolios are well-suited for formative assessment of teaching, as the portfolio format lends itself to documenting how your teaching has evolved over time. Instructors can use their teaching portfolios as a reflective practice to review past teaching experiences, what worked and what did not.

Teaching portfolios consist of various pieces of evidence about your teaching such as course syllabi, outlines, lesson plans, course evaluations, and more. Instructors curate these pieces of evidence into a collection, giving them the chance to highlight their own growth and focus as educators. While student input may be incorporated as part of the portfolio, instructors can contextualize and respond to student feedback, giving them the chance to tell their own teaching story from a more holistic perspective.

Teaching portfolios encourage self-reflection, especially with guided questions or rubrics to review your work. In addition, an instructor might consider sharing their entire teaching portfolio or selected materials for a single course with colleagues and engaging in a peer review discussion.

Examples and Resources:

Teaching Portfolio - Career Center

Developing a Statement of Teaching Philosophy and Teaching Portfolio - GSI Teaching & Resource Center

Self Assessment - UCLA Center for Education, Innovation, and Learning in the Sciences

Advancing Inclusion and Anti-Racism in the College Classroom Rubric and Guide

Course Design Equity and Inclusion Rubric

Teaching Demos or Peer Observation

Teaching demonstrations or peer classroom observation provide opportunities to get feedback on your teaching practice, including communication skills or classroom management.

Teaching demonstrations may be arranged as a simulated classroom environment in front of a live audience who take notes and then deliver summarized feedback. Alternatively, demonstrations may involve recording an instructor teaching to an empty room, and this recording can be subjected to later self-review or peer review. Evaluation of teaching demos will often focus on the mechanics of teaching especially for a lecture-based class, e.g. pacing of speech, organization of topics, clarity of explanations.

In contrast, instructors may invite a colleague to observe an actual class session to evaluate teaching in an authentic situation. This arrangement gives the observer a better sense of how the instructor interacts with students both individually or in groups, including their approach to answering questions or facilitating participation. The colleague may take general notes on what they observe or evaluate the instructor using a teaching rubric or other structured tool.

Peer Review of Course Instruction

Preparing for a Teaching Demonstration - UC Irvine Center for Educational Effectiveness

Based on Peer Feedback - UCLA Center for Education, Innovation, and Learning in the Sciences

Teaching Practices Equity and Inclusion Rubric

Classroom Observation Protocol for Undergraduate STEM (COPUS)

Student Learning Assessments

Student learning can vary widely across courses or even between academic terms. However, having a clear benchmark for the intended learning objectives and determining whether an instructor’s course as implemented helps students to reach that benchmark can be an invaluable piece of information to guide your teaching. The method for measuring student learning will depend on the stated learning objective, but a well-vetted instrument can provide the most reliable data.

Recommended steps and considerations for using student learning assessments to evaluate your teaching efficacy include:

Identify a small subset of course learning objectives to focus on, as it is more useful to accurately evaluate one objective vs. evaluating many objectives inaccurately.

Find a well-aligned and well-developed measure for each selected course learning objective, such as vetted exam questions, rubrics, or concept inventories.

If relevant, develop a prompt or assignment that will allow students to demonstrate the learning objective to then be evaluated against the measure.

Plan the timing of data collection to enable useful comparison and interpretation.

Do you want to compare how students perform at the start of your course compared to the same students at the end of your course?

Do you want to compare how the same students perform before and after a specific teaching activity?

Do you want to compare how students in one term perform compared to students in the next term, after changing your teaching approach?

Implement the assignment/prompt and evaluate a subset or all of the student work according to the measure.

Reflect on the results and compare student performance measures.

Are students learning as a result of your teaching activity and course design?

Are students learning to the degree that you intended?

Are students learning more when you change how you teach?

This process can be repeated as many times as needed or the process can be restarted to instead focus on a different course learning objective.

List of Concept Inventories (STEM)

Best Practices for Administering Concept Inventories (Physics)

AAC&U VALUE Rubrics

Rubric Bank | Assessment and Curriculum Support Center - University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

Rubrics - World Languages Resource Collection - Kennesaw State University

Student Surveys or Focus Groups

Surveys or focus groups are effective tools to better understand the student experience in your courses, as well as to solicit feedback on how courses can be improved. Hearing student voices is critical as students themselves can attest to how course activities made them feel, e.g. whether they perceive the learning environment to be inclusive, or what topics they find interesting.

Some considerations for using student surveys in your teaching include:

Surveys collect individual and anonymous input from as many students as possible.

Surveys can gather both quantitative and qualitative data.

Surveys that are anonymous avoid privileging certain voices over others.

Surveys can enable students to share about sensitive experiences that they may be reluctant to discuss publicly.

Surveys that are anonymous may lend to negative response bias.

Survey options at UC Berkeley include customized course evaluation questions or anonymous surveys on bCourses, Google Forms, or Qualtrics.

Some considerations for using student focus groups in your teaching include:

Focus groups leverage the power of group brainstorming to identify problems and imagine possible solutions.

Focus groups can gather both rich and nuanced qualitative data.

Focus groups with a skilled facilitator tend to have more moderated responses given the visibility of the discussion.

Focus groups take planning, preparation, and dedicated class time.

Focus group options at UC Berkeley include scheduling a Mid-semester Inquiry (MSI) to be facilitated by a CTL staff member.

Instructions for completing question customization for your evaluations as an instructor

Course Evaluations Question Bank

Student-Centered Evaluation Questions for Remote Learning

Based on Student Feedback - UCLA Center for Education, Innovation, and Learning in the Sciences

How Can Instructors Encourage Students to Complete Course Evaluations and Provide Informative Responses?

Student Views/Attitudes/Affective Instruments - ASBMB

Student Skills Inventories - ASBMB

How might I get started?

Self-assess your own course materials using one of the available rubrics listed above.

Schedule a teaching observation with CTL to get a colleague’s feedback on your teaching practices and notes on student engagement.

Schedule an MSI with CTL to gather directed student feedback with the support of a colleague.

Have more questions? Schedule a general consultation with CTL or send us your questions by email ( [email protected] )!

References:

Evaluating Teaching - UCSB Instructional Development

Documenting Teaching - UCSC Center for Innovations in Teaching and Learning

Other Forms of Evaluation - UCLA Center for Education, Innovation, and Learning in the Sciences

Evaluation Of Teaching Committee on Teaching, Academic Senate

Report of the Academic Council Teaching Evaluation Task Force

Teaching Quality Framework Initiative Resources - University of Colorado Boulder

Benchmarks for Teaching Effectiveness - University of Kansas Center for Teaching Excellence

Teaching Practices Instruments - ASBMB

Search form

- About Faculty Development and Support

- Programs and Funding Opportunities

Consultations, Observations, and Services

- Strategic Resources & Digital Publications

- Canvas @ Yale Support

- Learning Environments @ Yale

- Teaching Workshops

- Teaching Consultations and Classroom Observations

- Teaching Programs

- Spring Teaching Forum

- Written and Oral Communication Workshops and Panels

- Writing Resources & Tutorials

- About the Graduate Writing Laboratory

- Writing and Public Speaking Consultations

- Writing Workshops and Panels

- Writing Peer-Review Groups

- Writing Retreats and All Writes

- Online Writing Resources for Graduate Students

- About Teaching Development for Graduate and Professional School Students

- Teaching Programs and Grants

- Teaching Forums

- Resources for Graduate Student Teachers

- About Undergraduate Writing and Tutoring

- Academic Strategies Program

- The Writing Center

- STEM Tutoring & Programs

- Humanities & Social Sciences

- Center for Language Study

- Online Course Catalog

- Antiracist Pedagogy

- NECQL 2019: NorthEast Consortium for Quantitative Literacy XXII Meeting

- STEMinar Series

- Teaching in Context: Troubling Times

- Helmsley Postdoctoral Teaching Scholars

- Pedagogical Partners

- Instructional Materials

- Evaluation & Research

- STEM Education Job Opportunities

- Yale Connect

- Online Education Legal Statements

You are here

Formative and summative assessments.

Assessment allows both instructor and student to monitor progress towards achieving learning objectives, and can be approached in a variety of ways. Formative assessment refers to tools that identify misconceptions, struggles, and learning gaps along the way and assess how to close those gaps. It includes effective tools for helping to shape learning, and can even bolster students’ abilities to take ownership of their learning when they understand that the goal is to improve learning, not apply final marks (Trumbull and Lash, 2013). It can include students assessing themselves, peers, or even the instructor, through writing, quizzes, conversation, and more. In short, formative assessment occurs throughout a class or course, and seeks to improve student achievement of learning objectives through approaches that can support specific student needs (Theal and Franklin, 2010, p. 151).

In contrast, summative assessments evaluate student learning, knowledge, proficiency, or success at the conclusion of an instructional period, like a unit, course, or program. Summative assessments are almost always formally graded and often heavily weighted (though they do not need to be). Summative assessment can be used to great effect in conjunction and alignment with formative assessment, and instructors can consider a variety of ways to combine these approaches.

Examples of Formative and Summative Assessments

Both forms of assessment can vary across several dimensions (Trumbull and Lash, 2013):

- Informal / formal

- Immediate / delayed feedback

- Embedded in lesson plan / stand-alone

- Spontaneous / planned

- Individual / group

- Verbal / nonverbal

- Oral / written

- Graded / ungraded

- Open-ended response / closed/constrained response

- Teacher initiated/controlled / student initiated/controlled

- Teacher and student(s) / peers

- Process-oriented / product-oriented

- Brief / extended

- Scaffolded (teacher supported) / independently performed

Recommendations

Formative Assessment Ideally, formative assessment strategies improve teaching and learning simultaneously. Instructors can help students grow as learners by actively encouraging them to self-assess their own skills and knowledge retention, and by giving clear instructions and feedback. Seven principles (adapted from Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2007 with additions) can guide instructor strategies:

- Keep clear criteria for what defines good performance - Instructors can explain criteria for A-F graded papers, and encourage student discussion and reflection about these criteria (this can be accomplished though office hours, rubrics, post-grade peer review, or exam / assignment wrappers ). Instructors may also hold class-wide conversations on performance criteria at strategic moments throughout a term.

- Encourage students’ self-reflection - Instructors can ask students to utilize course criteria to evaluate their own or a peer’s work, and to share what kinds of feedback they find most valuable. In addition, instructors can ask students to describe the qualities of their best work, either through writing or group discussion.

- Give students detailed, actionable feedback - Instructors can consistently provide specific feedback tied to predefined criteria, with opportunities to revise or apply feedback before final submission. Feedback may be corrective and forward-looking, rather than just evaluative. Examples include comments on multiple paper drafts, criterion discussions during 1-on-1 conferences, and regular online quizzes.

- Encourage teacher and peer dialogue around learning - Instructors can invite students to discuss the formative learning process together. This practice primarily revolves around mid-semester feedback and small group feedback sessions , where students reflect on the course and instructors respond to student concerns. Students can also identify examples of feedback comments they found useful and explain how they helped. A particularly useful strategy, instructors can invite students to discuss learning goals and assignment criteria, and weave student hopes into the syllabus.

- Promote positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem - Students will be more motivated and engaged when they are assured that an instructor cares for their development. Instructors can allow for rewrites/resubmissions to signal that an assignment is designed to promote development of learning. These rewrites might utilize low-stakes assessments, or even automated online testing that is anonymous, and (if appropriate) allows for unlimited resubmissions.

- Provide opportunities to close the gap between current and desired performance - Related to the above, instructors can improve student motivation and engagement by making visible any opportunities to close gaps between current and desired performance. Examples include opportunities for resubmission, specific action points for writing or task-based assignments, and sharing study or process strategies that an instructor would use in order to succeed.

- Collect information which can be used to help shape teaching - Instructors can feel free to collect useful information from students in order to provide targeted feedback and instruction. Students can identify where they are having difficulties, either on an assignment or test, or in written submissions. This approach also promotes metacognition , as students are asked to think about their own learning. Poorvu Center staff can also perform a classroom observation or conduct a small group feedback session that can provide instructors with potential student struggles.

Instructors can find a variety of other formative assessment techniques through Angelo and Cross (1993), Classroom Assessment Techniques (list of techniques available here ).

Summative Assessment Because summative assessments are usually higher-stakes than formative assessments, it is especially important to ensure that the assessment aligns with the goals and expected outcomes of the instruction.

- Use a Rubric or Table of Specifications - Instructors can use a rubric to lay out expected performance criteria for a range of grades. Rubrics will describe what an ideal assignment looks like, and “summarize” expected performance at the beginning of term, providing students with a trajectory and sense of completion.

- Design Clear, Effective Questions - If designing essay questions, instructors can ensure that questions meet criteria while allowing students freedom to express their knowledge creatively and in ways that honor how they digested, constructed, or mastered meaning. Instructors can read about ways to design effective multiple choice questions .

- Assess Comprehensiveness - Effective summative assessments provide an opportunity for students to consider the totality of a course’s content, making broad connections, demonstrating synthesized skills, and exploring deeper concepts that drive or found a course’s ideas and content.

- Make Parameters Clear - When approaching a final assessment, instructors can ensure that parameters are well defined (length of assessment, depth of response, time and date, grading standards); knowledge assessed relates clearly to content covered in course; and students with disabilities are provided required space and support.

- Consider Blind Grading - Instructors may wish to know whose work they grade, in order to provide feedback that speaks to a student’s term-long trajectory. If instructors wish to provide truly unbiased summative assessment, they can also consider a variety of blind grading techniques .

Considerations for Online Assessments

Effectively implementing assessments in an online teaching environment can be particularly challenging. The Poorvu Center shares these recommendations .

Nicol, D.J. and Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006) Formative assessment and self‐regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education 31(2): 2-19.

Theall, M. and Franklin J.L. (2010). Assessing Teaching Practices and Effectiveness for Formative Purposes. In: A Guide to Faculty Development. KJ Gillespie and DL Robertson (Eds). Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA.

Trumbull, E., & Lash, A. (2013). Understanding formative assessment: Insights from learning theory and measurement theory. San Francisco: WestEd.

YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN

Instructional Enhancement Fund

The Instructional Enhancement Fund (IEF) awards grants of up to $500 to support the timely integration of new learning activities into an existing undergraduate or graduate course. All Yale instructors of record, including tenured and tenure-track faculty, clinical instructional faculty, lecturers, lectors, and part-time acting instructors (PTAIs), are eligible to apply. Award decisions are typically provided within two weeks to help instructors implement ideas for the current semester.

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning routinely supports members of the Yale community with individual instructional consultations and classroom observations.

Reserve a Room

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning partners with departments and groups on-campus throughout the year to share its space. Please review the reservation form and submit a request.

- Office of Curriculum, Assessment and Teaching Transformation >

- Teaching at UB >

- Course Development >

- Design Your Course >

- Designing Assessments >

Formative Assessment

Assessing student progress during learning to adjust and improve instruction.

On this page:

The importance of formative assessment.

Assessment is formative when:

- Evidence is gathered about student achievement or understanding.

- The information allows the instructor or learner to alter future instructional steps.

- It is done to improve learning outcomes (Black & Wiliam, 2009).

It is the use of the assessment that makes it formative. If evidence of student achievement is not used to adapt instruction or to give feedback to students to improve their learning, it is summative. Formative assessments are a natural part of the scaffolding process, and provide the following benefits:

Instructor Benefits

- Helps recognize student strengths and knowledge or skill gaps to determine level of scaffolding needed.

- Used to adapt instruction and reflect on instructional practices.

- Allows for opportunities to give feedback and guide learning.

Student Benefits

- Determines level of understanding or skill development.

- Identifies areas to review and study.

- Promotes self-regulating strategies.

- Allows for opportunities to receive feedback and guidance.

Therefore, use formative assessments to:

- Check for understanding.

- Gauge progress toward learning outcomes.

- Provide students with support and guidance.

- Pace instruction and adjust as needed.

Previous studies, and large meta-analyses that gather the findings from these studies have shown large effects on student learning gains, equivalent of 1 to 2 letter grades, when teachers use formative assessment (Black & Wiliam, 1998; 2006; Hattie, 2008). It should be noted that there are challenges to the accuracy of research on formative assessment, with the most notable criticisms being vague and often circular definitions of what constitutes formative assessment, poor research design of many studies, and no agreed upon methods or terminology for formative assessment (Dunn & Mulvenon, 2009; Kingston & Nash, 2011). These are issues related to how people have studied formative assessment and not formative assessment itself.

Using Formative Assessment in Your Course

Examples of formative assessment.

The following examples of assessment can be used formatively to assess student achievement and alter teaching and learning throughout your course.

Activities , assignments and assessments can all be utilized as formative approaches if they are used to give instructors and students feedback to alter teaching and learning. For feedback to your students to be effective it must be timely, relevant and caring.

Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs)

Classroom Assessment Techniques (Angelo and Cross, 1993) are formative assessments that are meant to be quick and flexible formative assessments. The following sites have compiled a variety of examples:

15 CATs suitable for use with large, lecture-style classes.

CATs to assess learners’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, self-awareness and reactions to instruction; List organized by level of Bloom’s taxonomy that the set of CATs target.

1-page chart with selected CATs examples – names, descriptions, amount of time (prep & in-class) required for each.

When you are done choosing or creating formative assessments continue:

or move on to:

Additional resources

Provides an overview of both assessment types.

Through research and analysis this article emphasizes the important of why formative assessments should be used.

Formative assessment techniques

20+ ideas for quick formative assessments to assess student learning.

An in-depth explanation and example(s) of 10 easy & quick-to-administer formative assessments.

Different formative assessment strategies that can be easily integrated into your course to check for student understanding.

Formative assessment examples in higher education.

Formative assessment strategies and techniques you can integrate into your course design.

Creative alternative assessments to build engagement in your course and check for student understanding.

CATs resources

What are CATs, benefits (to student and faculty), when, how, and how often to use, 10 in-depth examples.

Brief article establishing a conceptual model for the use of CATs in an online classroom.

What are CATs, why should you use them, examples.

Sample CAT to quickly do with your students after lesson that assesses confusing “muddy” points, unanswered questions and helpful/not helpful techniques, examples, etc.

Description, impacts (students & instructors), 7 characteristics of CATs, examples.

Example of a popular, broadly-applicable CAT – “exit tickets.”

For further information about active learning, see the following readings:

- Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers. Second Edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050102

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2006). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. London, England: Granada Learning.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 5–31.

- Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.). (2000). How people learn: brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Dunn, K. E., & Mulvenon, S. W. (2009). A critical review of research on formative assessment: The limited scientific evidence of the impact of formative assessment in education. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 14(7), 1–11.

- Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses . John Wiley & Sons.

- Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Karns, K., Hamlett, C. L., Katzaroff, M., & Dutka, S. (1997). Effects of task-focused goals on low-achieving students with and without learning disabilities. American Educational Research Journal , 34 (3), 513-543.

- Hattie, J. (2008). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kingston, N., & Nash, B. (2011). Formative assessment: A meta-analysis and a call for research. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 30(4), 28–37.

- Moss, C. M., & Brookhart, S. M. (2010). Advancing formative assessment in every classroom: A guide for instructional leaders. ASCD.

- Suskie, L. (2009). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Wiggins, G. (1998). Educative assessment. Designing assessments to inform and improve student performance. Jossey-Bass Publishers, 350 Sansome Street, San Francisco, CA 94104.

- Wiliam, D., & Thompson, M. (2017). Integrating assessment with learning: what will it take to make it work? In C. A. Dwyer (Ed.), The Future of Assessment: Shaping Teaching and Learning (pp. 53–82). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Global Perspectives on Higher Education pp 59–73 Cite as

Enhancing Learning Through Formative Assessment: Evidence-Based Strategies for Implementing Learner Reflection in Higher Education

- Li-Shih Huang 11 ,

- Raj Khatri 12 &

- Amjad Alhemaid 12

- First Online: 30 June 2023

226 Accesses

Part of the book series: Knowledge Studies in Higher Education ((KSHE,volume 11))

Reflection is irrefutably one of the key concepts of education theory, and its importance and benefits have been widely explored and recognized across disciplines. The ability of learners to reflect critically through control over their own learning and construct knowledge and of instructors to modify practices that promote transformative learning (Mezirow, Transformative dimensions of adult learning. Jossey-Bass, 1991) and support self-regulated, autonomous learners have been recognized as essential in higher education. However, a review of the literature from the past few decades shows that the learner-, situation-, and context-dependent nature of reflection remains obscure to most educators in both implementing reflective learning and assessing reflective thinking. The key challenge in using learner reflection for assessment for learning lies in measuring transformative learning, owing to a lack of “explicit and direct attention to the process of evaluating [it]” (Cranton & Hoggan, Handbook of transformative learning: Theory, research, and practice. Jossey-Bass, 2012, p. 531). Within the context of two institutions that prioritize integrating experiential learning (Kolb, Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall, 1984), where critical analysis and synthesis of observations and reflections derived from concrete learning experiences are central and fundamental, this chapter aims to connect insights from theory, research, and direct experience to practices instructors can use to inform their own teaching by addressing thorny issues pertaining to implementing and assessing reflection. These insights transcend any single task, course, or program in higher education.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Alhemaid, A. (forthcoming). Developing speaking strategies among adult English-as-an-additional-language learners in performing the IELTS speaking tasks, mediated by audio tape-recorded and video-stimulated individual verbal reflection . [Doctoral dissertation, University of Victoria].

Google Scholar

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives . Longman.

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E., Pintrich, P. R., et al. (2013). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives . (Abridged edition). Pearson Education.

Berry, V., Sheehan, S., & Munro, S. (2019). What does language assessment literacy mean to teachers? ELT Journal, 73 (2), 113–123.

Article Google Scholar

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 3 (1), 7–74.

Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Reflection: Turning experience into learning . Routledge Falmer.

Colley, B. M., Bilics, A. R., & Lerch, C. M. (2012). Reflection: A key component to thinking critically. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 3 (1), 1–19.

Coombe, C. (2018). An A to Z of second language assessment: How language teachers understand assessment concepts . The British Council.

Cowie, B., & Bell, B. (1999). A model of formative assessment in science education. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 6 (1), 32–42.

Cranton, P., & Hoggan, C. (2012). Evaluating transformative learning. In E. Taylor & P. Cranton (Eds.), Handbook of transformative learning: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 520–535). Jossey-Bass.

Efklides, A., & Misailidi, P. (2010). Trends and prospects in metacognition research . Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Ellis, S., & Davidi, I. (2005). After-event reviews: Drawing lessons from successful and failed experience. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90 , 857–871.

Fund, Z., Court, D., & Kramarski, B. (2002). Construction and application of an evaluative tool to assess reflection in teacher-training courses. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 27 (26), 485–499.

Galante, A. (2021). Translation as a pedagogical tool in multilingual classes: Engaging the learners’ plurilingual repertoire. In Á. Carreres, M. Noriega-Sánchez, & L. P. Gutiérrez (Eds.), Translation and plurilingual approaches to language teaching and learning: Challenges and possibilities (pp. 106–123). John Benjamins Publishing.

García, O. (2009). Education, multilingualism and translanguaging in the 21st century. In A. K. Mohanty, M. Panda, R. Phillipson, & T. Skutnabb-Kangas (Eds.), Multilingual education for social justice: Globalising the local (pp. 128–145). Orient Black Swan.

George Brown College. (2019). Imagining possibilities: Vision 2030 . Strategy 2022. https://www.georgebrown.ca/media/3281/view

Hatton, N., & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: Towards definition and implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11 (1), 33–49.

Huang, L.-S. (2010). Do different modalities of reflection matter? An exploration of adult second-language learners’ reported strategy use and oral language production. System: An International Journal of Educational Technology and Applied Linguistics, 38 (2), 245–261.

Huang, L.-S. (2012). Use of oral reflection in failitating graduate EAL students’ oral-language production and strategy use: An empirial action research study. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 6 (2), Article 27. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/ij-sotl/vol6/iss2/27/

Huang, L.-S. (2017). Three ideas for implementing learner reflection. Faculty Focus . https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-and-learning/three-ideas-implementing-learner-reflection/

Huang, L.-S. (2018). A call for critical dialogue: EAP assessment from the practitioner’s perspective in Canada. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 35 , 70–84.

Huang, L.-S. (2021). Improving learner reflection for TESOL: Pedagogical strategies to support reflective learning . Routledge.

Kember, D., McKay, J., Sinclair, K., & Wong, F. K. Y. (2008). A four-category scheme for coding and assessing the level of reflection in written work. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33 (4), 369–379.

Khatri, R. (2018). The efficacy of academic reading strategy instruction among adult English as an additional language students: A professional development opportunity through action research. TESL Canada Journal, 35 (2), 78–103.

Kind, S., Irwin, R., Grauer, K., & De Cosson, A. (2005). Medicine wheel imag(in)ings: Exploring holistic curriculum perspectives. Art Education, 58 (5), 33–38.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development . Prentice-Hall.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2017). Experiential learning theory as a guide for experiential educators in higher education. Experiential Learning & Teaching in Higher Education, 1 (1), 1–38.

Kreber, C., Klampfleitner, M., McCune, V., Bayne, S., & Knottenbelt, M. (2007). What do you mean by “authentic”? A comparative review of the literature on conceptions of authenticity in teaching. Adult Education Quarterly, 58 (1), 22–43.

Kulasegaram, K., & Rangachari, P. K. (2018). Beyond “formative”: Assessments to enrich student learning. Advances in Physiology Education, 42 (5), 5–14.

Lau, K. (2016). Assessing reflection in English enhancement courses: Teachers’ views and development of a holistic framework. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41 (6), 854–868.

Loone, A., Joy Cumming, van Der Kleij, F., & Harris, K. (2017). Reconceptualising the role of teachers as assessors: Teacher assessment identity. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice . https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2016.1268090

Looney, J. (Ed.). (2005). Formative assessment: Improving learning in secondary classrooms . Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning . Jossey-Bass.

Mittler, P. (1973). Assessment for learning in the mentally handicapped . Churchill Livingstone.

Nguyen, Q. D., Fernanandez, N., Karsenti, T., & Charlin, B. (2014). What is reflection? A conceptual analysis of major definitions and a proposal of a five-component model. Medical Education, 48 , 1176–1189.

OECD/CERI. (n.d.). Assessment for learning: Formative assessment . OECD/CERI International Conference, “Learning in the 21st Century: Research, Innovation and Policy.” https://www.oecd.org/site/educeri21st/40600533.pdf

Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research . Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00422/full

Parkes, K. A., & Kajder, S. (2010). Eliciting and assessing reflective practice: A case study in web 2.0 technologies. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 22 (2), 218–228.

Pavlovich, K., Collins, E., & Jones, G. (2009). Developing students’ skills in reflective practice: Design and assessment. Journal of Management Education, 33 (1), 37–58.

Peltier, J. W., Hay, A., & Drago, W. (2005). The reflective learning continuum: Reflection on reflection. Journal of Marketing Education, 27 , 250–263.

Poldner, E., Simons, P. R. J., Wijingaards, G., & van der Schaaf, M. F. (2012). Quantitative content analysis procedures to analyse students’ reflective essays: A methodological review of psychometric and edumetric aspects. Education Research Review, 7 (1), 19–37.

Shepard, L. A., Hammerness, K., Darling-Hammond, L., Rust, F., Snowden, J. B., Gordon, E., Gutierrez, C., & Pacheco, A. (2005). Assessment. In L. Darling-Hammond & J. Bransford (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 275–326). Jossey-Bass.

University of Victoria. (2018). A strategic framework for the University of Victoria: 2018–2023 . https://www.uvic.ca/strategicframework/assets/docs/strategic-framework-2018.pdf

Villarroel, V., Benavente, M., Chuecas, M. J., & Bruna, D. (2020). Experiential learning in higher education: A student-centered teaching method that improves perceived learning. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 17 (5), Article 8. https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol17/iss5/8

Wiliam, D. (2017). Embedded formative assessment (2nd ed.). Solution Tree.

Wium, A.-M., & du Plessis, S. (2016). The usefulness of a tool to assess reflection in a service-learning experience. AJHPE, 8 (2), 178–183.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Linguistics, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada

Li-Shih Huang

University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada

Raj Khatri & Amjad Alhemaid

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Li-Shih Huang .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Leadership Studies College of Professional Advancement, Mercer University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Jacqueline S. Stephen

Al Yamamah University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Georgios Kormpas

General Education, HCT - Dubai Men’s College, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Christine Coombe

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Huang, LS., Khatri, R., Alhemaid, A. (2023). Enhancing Learning Through Formative Assessment: Evidence-Based Strategies for Implementing Learner Reflection in Higher Education. In: Stephen, J.S., Kormpas, G., Coombe, C. (eds) Global Perspectives on Higher Education. Knowledge Studies in Higher Education, vol 11. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31646-3_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31646-3_5

Published : 30 June 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-31645-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-31646-3

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Our Mission

7 Smart, Fast Ways to Do Formative Assessment

Within these methods you’ll find close to 40 tools and tricks for finding out what your students know while they’re still learning.

Formative assessment—discovering what students know while they’re still in the process of learning it—can be tricky. Designing just the right assessment can feel high stakes—for teachers, not students—because we’re using it to figure out what comes next. Are we ready to move on? Do our students need a different path into the concepts? Or, more likely, which students are ready to move on and which need a different path?

When it comes to figuring out what our students really know, we have to look at more than one kind of information. A single data point—no matter how well designed the quiz, presentation, or problem behind it—isn’t enough information to help us plan the next step in our instruction.

Add to that the fact that different learning tasks are best measured in different ways, and we can see why we need a variety of formative assessment tools we can deploy quickly, seamlessly, and in a low-stakes way—all while not creating an unmanageable workload. That’s why it’s important to keep it simple: Formative assessments generally just need to be checked, not graded, as the point is to get a basic read on the progress of individuals, or the class as a whole.

7 Approaches to Formative Assessment

1. Entry and exit slips: Those marginal minutes at the beginning and end of class can provide some great opportunities to find out what kids remember. Start the class off with a quick question about the previous day’s work while students are getting settled—you can ask differentiated questions written out on chart paper or projected on the board, for example.

Exit slips can take lots of forms beyond the old-school pencil and scrap paper. Whether you’re assessing at the bottom of Bloom’s taxonomy or the top, you can use tools like Padlet or Poll Everywhere , or measure progress toward attainment or retention of essential content or standards with tools like Google Classroom’s Question tool , Google Forms with Flubaroo , and Edulastic , all of which make seeing what students know a snap.

A quick way to see the big picture if you use paper exit tickets is to sort the papers into three piles : Students got the point; they sort of got it; and they didn’t get it. The size of the stacks is your clue about what to do next.

No matter the tool, the key to keeping students engaged in the process of just-walked-in or almost-out-the-door formative assessment is the questions. Ask students to write for one minute on the most meaningful thing they learned. You can try prompts like:

- What are three things you learned, two things you’re still curious about, and one thing you don’t understand?

- How would you have done things differently today, if you had the choice?

- What I found interesting about this work was...

- Right now I’m feeling...

- Today was hard because...

Or skip the words completely and have students draw or circle emojis to represent their assessment of their understanding.

2. Low-stakes quizzes and polls: If you want to find out whether your students really know as much as you think they know, polls and quizzes created with Socrative or Quizlet or in-class games and tools like Quizalize , Kahoot , FlipQuiz, Gimkit , Plickers , and Flippity can help you get a better sense of how much they really understand. (Grading quizzes but assigning low point values is a great way to make sure students really try: The quizzes matter, but an individual low score can’t kill a student’s grade.) Kids in many classes are always logged in to these tools, so formative assessments can be done very quickly. Teachers can see each kid’s response, and determine both individually and in aggregate how students are doing.

Because you can design the questions yourself, you determine the level of complexity. Ask questions at the bottom of Bloom’s taxonomy and you’ll get insight into what facts, vocabulary terms, or processes kids remember. Ask more complicated questions (“What advice do you think Katniss Everdeen would offer Scout Finch if the two of them were talking at the end of chapter 3?”), and you’ll get more sophisticated insights.

3. Dipsticks: So-called alternative formative assessments are meant to be as easy and quick as checking the oil in your car, so they’re sometimes referred to as dipsticks . These can be things like asking students to:

- write a letter explaining a key idea to a friend,

- draw a sketch to visually represent new knowledge, or

- do a think, pair, share exercise with a partner.

Your own observations of students at work in class can provide valuable data as well, but they can be tricky to keep track of. Taking quick notes on a tablet or smartphone, or using a copy of your roster, is one approach. A focused observation form is more formal and can help you narrow your note-taking focus as you watch students work.

4. Interview assessments: If you want to dig a little deeper into students’ understanding of content, try discussion-based assessment methods. Casual chats with students in the classroom can help them feel at ease even as you get a sense of what they know, and you may find that five-minute interview assessments work really well. Five minutes per student would take quite a bit of time, but you don’t have to talk to every student about every project or lesson.

You can also shift some of this work to students using a peer-feedback process called TAG feedback (Tell your peer something they did well, Ask a thoughtful question, Give a positive suggestion). When you have students share the feedback they have for a peer, you gain insight into both students’ learning.

For more introverted students—or for more private assessments—use Flipgrid , Explain Everything , or Seesaw to have students record their answers to prompts and demonstrate what they can do.

5. Methods that incorporate art: Consider using visual art or photography or videography as an assessment tool. Whether students draw, create a collage, or sculpt, you may find that the assessment helps them synthesize their learning . Or think beyond the visual and have kids act out their understanding of the content. They can create a dance to model cell mitosis or act out stories like Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” to explore the subtext.

6. Misconceptions and errors: Sometimes it’s helpful to see if students understand why something is incorrect or why a concept is hard. Ask students to explain the “ muddiest point ” in the lesson—the place where things got confusing or particularly difficult or where they still lack clarity. Or do a misconception check : Present students with a common misunderstanding and ask them to apply previous knowledge to correct the mistake, or ask them to decide if a statement contains any mistakes at all, and then discuss their answers.

7. Self-assessment: Don’t forget to consult the experts—the kids. Often you can give your rubric to your students and have them spot their strengths and weaknesses.

You can use sticky notes to get a quick insight into what areas your kids think they need to work on. Ask them to pick their own trouble spot from three or four areas where you think the class as a whole needs work, and write those areas in separate columns on a whiteboard. Have you students answer on a sticky note and then put the note in the correct column—you can see the results at a glance.

Several self-assessments let the teacher see what every kid thinks very quickly. For example, you can use colored stacking cups that allow kids to flag that they’re all set (green cup), working through some confusion (yellow), or really confused and in need of help (red).

Similar strategies involve using participation cards for discussions (each student has three cards—“I agree,” “I disagree,” and “I don’t know how to respond”) and thumbs-up responses (instead of raising a hand, students hold a fist at their belly and put their thumb up when they’re ready to contribute). Students can instead use six hand gestures to silently signal that they agree, disagree, have something to add, and more. All of these strategies give teachers an unobtrusive way to see what students are thinking.

No matter which tools you select, make time to do your own reflection to ensure that you’re only assessing the content and not getting lost in the assessment fog . If a tool is too complicated, is not reliable or accessible, or takes up a disproportionate amount of time, it’s OK to put it aside and try something different.

Center for Teaching

Assessing student learning.

Forms and Purposes of Student Assessment

Assessment is more than grading, assessment plans, methods of student assessment, generative and reflective assessment, teaching guides related to student assessment, references and additional resources.

Student assessment is, arguably, the centerpiece of the teaching and learning process and therefore the subject of much discussion in the scholarship of teaching and learning. Without some method of obtaining and analyzing evidence of student learning, we can never know whether our teaching is making a difference. That is, teaching requires some process through which we can come to know whether students are developing the desired knowledge and skills, and therefore whether our instruction is effective. Learning assessment is like a magnifying glass we hold up to students’ learning to discern whether the teaching and learning process is functioning well or is in need of change.

To provide an overview of learning assessment, this teaching guide has several goals, 1) to define student learning assessment and why it is important, 2) to discuss several approaches that may help to guide and refine student assessment, 3) to address various methods of student assessment, including the test and the essay, and 4) to offer several resources for further research. In addition, you may find helfpul this five-part video series on assessment that was part of the Center for Teaching’s Online Course Design Institute.

What is student assessment and why is it Important?

In their handbook for course-based review and assessment, Martha L. A. Stassen et al. define assessment as “the systematic collection and analysis of information to improve student learning” (2001, p. 5). An intentional and thorough assessment of student learning is vital because it provides useful feedback to both instructors and students about the extent to which students are successfully meeting learning objectives. In their book Understanding by Design , Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe offer a framework for classroom instruction — “Backward Design”— that emphasizes the critical role of assessment. For Wiggins and McTighe, assessment enables instructors to determine the metrics of measurement for student understanding of and proficiency in course goals. Assessment provides the evidence needed to document and validate that meaningful learning has occurred (2005, p. 18). Their approach “encourages teachers and curriculum planners to first ‘think like an assessor’ before designing specific units and lessons, and thus to consider up front how they will determine if students have attained the desired understandings” (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005, p. 18). [1]

Not only does effective assessment provide us with valuable information to support student growth, but it also enables critically reflective teaching. Stephen Brookfield, in Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher, argues that critical reflection on one’s teaching is an essential part of developing as an educator and enhancing the learning experience of students (1995). Critical reflection on one’s teaching has a multitude of benefits for instructors, including the intentional and meaningful development of one’s teaching philosophy and practices. According to Brookfield, referencing higher education faculty, “A critically reflective teacher is much better placed to communicate to colleagues and students (as well as to herself) the rationale behind her practice. She works from a position of informed commitment” (Brookfield, 1995, p. 17). One important lens through which we may reflect on our teaching is our student evaluations and student learning assessments. This reflection allows educators to determine where their teaching has been effective in meeting learning goals and where it has not, allowing for improvements. Student assessment, then, both develop the rationale for pedagogical choices, and enables teachers to measure the effectiveness of their teaching.

The scholarship of teaching and learning discusses two general forms of assessment. The first, summative assessment , is one that is implemented at the end of the course of study, for example via comprehensive final exams or papers. Its primary purpose is to produce an evaluation that “sums up” student learning. Summative assessment is comprehensive in nature and is fundamentally concerned with learning outcomes. While summative assessment is often useful for communicating final evaluations of student achievement, it does so without providing opportunities for students to reflect on their progress, alter their learning, and demonstrate growth or improvement; nor does it allow instructors to modify their teaching strategies before student learning in a course has concluded (Maki, 2002).

The second form, formative assessment , involves the evaluation of student learning at intermediate points before any summative form. Its fundamental purpose is to help students during the learning process by enabling them to reflect on their challenges and growth so they may improve. By analyzing students’ performance through formative assessment and sharing the results with them, instructors help students to “understand their strengths and weaknesses and to reflect on how they need to improve over the course of their remaining studies” (Maki, 2002, p. 11). Pat Hutchings refers to as “assessment behind outcomes”: “the promise of assessment—mandated or otherwise—is improved student learning, and improvement requires attention not only to final results but also to how results occur. Assessment behind outcomes means looking more carefully at the process and conditions that lead to the learning we care about…” (Hutchings, 1992, p. 6, original emphasis). Formative assessment includes all manner of coursework with feedback, discussions between instructors and students, and end-of-unit examinations that provide an opportunity for students to identify important areas for necessary growth and development for themselves (Brown and Knight, 1994).

It is important to recognize that both summative and formative assessment indicate the purpose of assessment, not the method . Different methods of assessment (discussed below) can either be summative or formative depending on when and how the instructor implements them. Sally Brown and Peter Knight in Assessing Learners in Higher Education caution against a conflation of the method (e.g., an essay) with the goal (formative or summative): “Often the mistake is made of assuming that it is the method which is summative or formative, and not the purpose. This, we suggest, is a serious mistake because it turns the assessor’s attention away from the crucial issue of feedback” (1994, p. 17). If an instructor believes that a particular method is formative, but he or she does not take the requisite time or effort to provide extensive feedback to students, the assessment effectively functions as a summative assessment despite the instructor’s intentions (Brown and Knight, 1994). Indeed, feedback and discussion are critical factors that distinguish between formative and summative assessment; formative assessment is only as good as the feedback that accompanies it.

It is not uncommon to conflate assessment with grading, but this would be a mistake. Student assessment is more than just grading. Assessment links student performance to specific learning objectives in order to provide useful information to students and instructors about learning and teaching, respectively. Grading, on the other hand, according to Stassen et al. (2001) merely involves affixing a number or letter to an assignment, giving students only the most minimal indication of their performance relative to a set of criteria or to their peers: “Because grades don’t tell you about student performance on individual (or specific) learning goals or outcomes, they provide little information on the overall success of your course in helping students to attain the specific and distinct learning objectives of interest” (Stassen et al., 2001, p. 6). Grades are only the broadest of indicators of achievement or status, and as such do not provide very meaningful information about students’ learning of knowledge or skills, how they have developed, and what may yet improve. Unfortunately, despite the limited information grades provide students about their learning, grades do provide students with significant indicators of their status – their academic rank, their credits towards graduation, their post-graduation opportunities, their eligibility for grants and aid, etc. – which can distract students from the primary goal of assessment: learning. Indeed, shifting the focus of assessment away from grades and towards more meaningful understandings of intellectual growth can encourage students (as well as instructors and institutions) to attend to the primary goal of education.

Barbara Walvoord (2010) argues that assessment is more likely to be successful if there is a clear plan, whether one is assessing learning in a course or in an entire curriculum (see also Gelmon, Holland, and Spring, 2018). Without some intentional and careful plan, assessment can fall prey to unclear goals, vague criteria, limited communication of criteria or feedback, invalid or unreliable assessments, unfairness in student evaluations, or insufficient or even unmeasured learning. There are several steps in this planning process.

- Defining learning goals. An assessment plan usually begins with a clearly articulated set of learning goals.

- Defining assessment methods. Once goals are clear, an instructor must decide on what evidence – assignment(s) – will best reveal whether students are meeting the goals. We discuss several common methods below, but these need not be limited by anything but the learning goals and the teaching context.

- Developing the assessment. The next step would be to formulate clear formats, prompts, and performance criteria that ensure students can prepare effectively and provide valid, reliable evidence of their learning.

- Integrating assessment with other course elements. Then the remainder of the course design process can be completed. In both integrated (Fink 2013) and backward course design models (Wiggins & McTighe 2005), the primary assessment methods, once chosen, become the basis for other smaller reading and skill-building assignments as well as daily learning experiences such as lectures, discussions, and other activities that will prepare students for their best effort in the assessments.

- Communicate about the assessment. Once the course has begun, it is possible and necessary to communicate the assignment and its performance criteria to students. This communication may take many and preferably multiple forms to ensure student clarity and preparation, including assignment overviews in the syllabus, handouts with prompts and assessment criteria, rubrics with learning goals, model assignments (e.g., papers), in-class discussions, and collaborative decision-making about prompts or criteria, among others.

- Administer the assessment. Instructors then can implement the assessment at the appropriate time, collecting evidence of student learning – e.g., receiving papers or administering tests.

- Analyze the results. Analysis of the results can take various forms – from reading essays to computer-assisted test scoring – but always involves comparing student work to the performance criteria and the relevant scholarly research from the field(s).

- Communicate the results. Instructors then compose an assessment complete with areas of strength and improvement, and communicate it to students along with grades (if the assignment is graded), hopefully within a reasonable time frame. This also is the time to determine whether the assessment was valid and reliable, and if not, how to communicate this to students and adjust feedback and grades fairly. For instance, were the test or essay questions confusing, yielding invalid and unreliable assessments of student knowledge.

- Reflect and revise. Once the assessment is complete, instructors and students can develop learning plans for the remainder of the course so as to ensure improvements, and the assignment may be changed for future courses, as necessary.