English Compositions

Short Essay on Fairy Tales [100, 200, 400 Words] With PDF

We have all loved reading and listening to fairy tales since our childhood. In this lesson today, you will learn how to write essays on fairy tales that you may find relevant for your exam.

Short Essay on Fairy Tales in 100 WORDS

Fairy tales are the pleasures of childhood. There is almost no one who has not read a fairy tale. A fairy tale is a fantasy story that has humans, animals, birds, magicians, kings and queens, princes, and princesses. It also has fairies. The animals and birds in fairy tales can talk.

Fairy tales are stories of good and bad. These are very old stories and often have morals with them. As children, we all read lots of fairy tales. Our parents and grandparents tell us fairy tales. We love to listen to these stories. They are not real. Still, it makes our childhood happy. Cinderella, Snow White, and Rapunzel are some famous fairy tales.

Short Essay on Fairy Tales in 200 Words

Fairy tales are the source of joy and happiness. There is no one who does not love to read or listen to fairy tales. These stories have magic and fun in them. It has humans, animals, birds, kings, queens, princes, princesses, magicians, and also fairies.

These tales are the best moments of our childhood. We all have heard of it from our parents and grandparents. Even if we grow up, we still love to read the tales of childhood. It takes away our problems as we read them. The fairy tales are indeed magical.

Every country has its own fairy tales. In India, we have Panchatantra and thakurmar jhuli. We have enjoyed reading these stories. Also, these tales are available on television. So that becomes a treat for us. Fairy tales also have morals. We have read moral stories, like Aesop’s fables. There, the animals talk and teach us morals. As children, we learn how to be good.

Fairy tales also teach us about the good and bad. It is always about the fight between the good and bad. In the end the good wins. It shows us the truth of life. Fairy tales are very simple to read. So children can easily understand its meaning. They receive lots of happiness by reading fairy tales.

Short Essay on Fairy Tales in 400 Words

Fairy tales are the happiness of childhood. There is no child who has not read a fairy tale. We not only read those stories but also hear about them from our parents and grandparents. It not only gives us joy but also teaches us many things.

Fairy tales also have morals at the end. It helps to teach the children the good and bad. Fairy tales have humans, animals, birds, kings, queens, princes, princesses, magicians, ghosts and fairies. All of these appear beautiful to us in our childhood. Still the morals we learn to stay with us forever.

All of us want to be in a fairy tale. It is a place different from Earth. The lives of the people in a fairy tale are always pretty. So it enables us to imagine it in that way. Making the child’s life safe and innocent is important. So fairy stories play an important part. All children read fairy tales. It helps them to think better. From a little age, fairy tales help them to imagine. They can create more because of fairy tales.

Every country has its own fairy tales. Aesop’s fables are also a sort of fairy tale. The fables have morals in them. It is very important. Children must have moral lessons from a little age. It teaches them the good and bad. We all have read fairy tales like Cinderella, Snow White, and Rapunzel. These are the most famous stories. Nowadays, many films are made from children’s fairy tales.

All these have made the stories more famous. In India, the stories of Panchatantra and Thakumar Jhuli are famous fairy tales. We feel scared when the devil arrives, and wait for the brave prince to come and rescue the princess. We are amazed by the winged horses, unicorns talking birds, and animals. All these make the reading of the story more beautiful.

A Fairy tale has no fixed time. It all starts with ‘ once upon a time.’ So we never know when it took place. This is a trick. This makes the tale more beautiful and magical. Every fairy tale has many problems. But in the end, it gets resolved. So the children feel positive at the end of fairy tales.

They feel happy. A faith remains that all problems have their solutions. Thus a fairy tale has a solution to everything. Children are encouraged to read books. And fairytales are the important stories that every child reads and enjoys.

In this session above, I have tried to discuss everything about fairy tales that could be relevant to writing essays. Moreover, I have tried a very simple approach to writing these essays for a better understanding of all the students. If you still have any doubts regarding this session, kindly post that in the comment section below. If you want to read more such essays, keep browsing our website.

To get all the latest updates on our upcoming sessions, kindly join us on Telegram . Thank you for being with us. All the best for your exam.

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

“Cinderella” Fairy Tale, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 585

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Cinderella is a celebrated classic tale representing myth-like elements such as unfair domination of evil powers resulting into glorious victory of the good ones. Nowadays there exist thousands of versions of the story celebrated all over the world. At the core of the plot invariably lies a story of a fortunate young girl living in ill-fated conditions which eventually turn into amazing luck.

The Cinderella subject matter has probably been developed from the very classical antiquity. Eventually, number of various versions of the same story appeared in the medieval One Thousand and One Nights, while some of those originated in Japan. The initial European version of modern Cinderella is “La Gatta Cenerentola” or “The Hearth Cat” which was originally included into the book “Il Pentamerone” by the Italian fairy-tale collector Giambattista Basile in 1635. It is believed that this very edition had become the one from which later versions by the French author Charles Perrault and the German Brothers Grimm were derived from.

Celebrated version by Charles Perrault written in 1697 owes its incredible popularity to the author’s innovative additions to the plot meaning the pumpkin, the fairy-godmother and the notable glass slippers. Another legendary version was written by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in the 19th century. The original tale is named “Aschenputtel”. It differs from the one by Perrault by the absence of fairy-godmother character. Cinderella receives help from the wishing tree that grows on her mother’s grave instead. It also includes a number of rather frightening details such as Cinderella’s sisters’ cutting of parts of their feet in order to trick the prince, and their eyes being pecked out by some pigeons, which results in their being doomed to live the lives of blind beggars.

Presently the mere word “cinderella” means a lot. We usually call that way someone whose good qualities are unrecognized and not yet appreciated by others, as well as someone who all at once gets appreciation and respect, or achieves striking success after a period of insignificance and negligence. It seems like the story will never stop being popular. It keeps on having a significant impact on the modern culture worldwide. No need to mention how great a variety of media has already adopted its storyline elements, and we can only guess how many more others are going to follow.

Through the years of existence “Cinderella” fairy tale has acquired a legendary fame indeed. I do not know a single person unfamiliar with at least some versions of the Cinderella story. The creation of thousands of films, musicals, television shows and songs has been inspired by the lucky young woman’s story, as well as hundreds of books have borrowed its plot lines from the original fairy tale in order to get at least the tiniest part of the fame it has accumulated through centuries. This beautiful story, with some details being changed yet the core idea being immutable, has become an inalienable part of the popular culture. And whether we acknowledge this or not, it has had a particular impact on the formation of each human being’s personality in one or another way. Cinderella story is not as simple as it may seem, and it definitely has something worth considering when dealing with lifelike situation. Reading the fairy tale or watching one of its film adaptations has become an important part of experience we gain at the initial stages of life in order to be prepared for living life of success rather than a life marred by the lack of appreciation and recognition.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Exceptions to the Fruit of the Poison Tree Doctrine, Essay Example

Charter Schools Versus Public Schools, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Relatives, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 364

Voting as a Civic Responsibility, Essay Example

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

- How-To Guides

How to Write a Fairy Tale in 8 Steps (With Examples)

In this step-by-step guide, we will show you how to write a fairy tale in 8 easy steps with examples. From Cinderella to Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, these classic fairy tales have been told and retold by storytellers for hundreds of years. But what makes them so special? In today’s post, we’ll give you the tools to write your own fairy tale.

What is a fairy Tale?

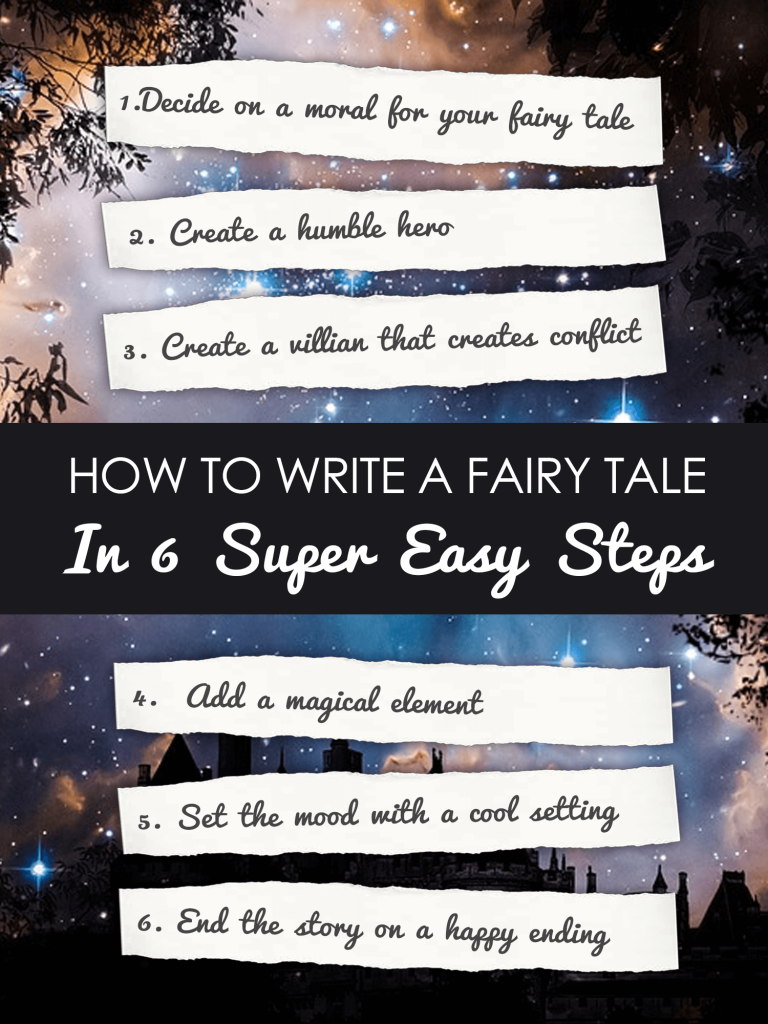

History of fairy tales, 1. decide on your fairy tale moral, 2. create your hero, 3. create your villain, 4. think about the magical element, 5. describe the setting, 6. write the opening paragraph, 7. write the middle section, 8. write a happy ending, fairy tale writing ideas, how do you start a fairy tale, what are the 5 elements of a fairy tale, what is the structure of a fairy tale, how long should a fairy tale be, what are some fairy tale writing techniques, bonus tips on writing fairy tales, write your own fairy tale now.

Fairy tales are stories that usually involve fairies, elves, witches, and other magical beings. These stories often feature heroes who overcome adversity and achieve their dreams. They are also called folktales and were originally told by word of mouth to entertain people.

The main character is often an orphan or someone who is facing great adversity, such as having no place to live or no food to eat. The character faces this adversity and then finds a way to overcome it. In the process, he/she usually overcomes greed, learns something new, and grows as a person. For example, Cinderella was forced to do all of her chores for her evil stepmother and stepsisters. But in the end, she overcomes her adversity and lives happily ever after with her true love.

This is what makes fairy tales so popular and relatable to people all over the world. We have all gone through hardships in our lives. A fairy tale is a story that shows us that we can come out of these situations much better than we were before.

How many fairy tales can you list? 5, 10, maybe 30? Throughout the ages, storytellers from around the world have created hundreds of fairy tales. No one knows the exact number of fairy tales out there. We just know the popular ones, like Cinderella, Jack and the Beanstalk, Snow White and Sleeping Beauty. You might even be surprised to learn that most fairy tales have their origin back in the 16th century. In fact, the first story of Cinderella was even told in 7 BC and was about a slave girl who marries the king of Egypt.

Even today fairy tales are a huge part of our lives. They teach us important morals, such as accepting others who are different or not talking to strangers and provide motivational tales of beating adversity and hardship. One of the most famous fairy tale writers out there is Hans Christian Andersen. Anderson has written no fewer than 3,381 works, including The Little Mermaid, The Ugly Duckling and The Emperor News Clothes.

To celebrate Hans Christian Andersen’s birthday on April 2 nd , we have created this tutorial on how to write a fairy tale in 8 steps. Now you can be the next fairy tale extraordinaire by writing your own fairy tales.

How To Write a Fairy Tale in 8 Steps

Now it’s your turn to write your own fairy tale. Don’t worry, it’s really easy when you follow these steps.

A moral is an important lesson your reader learns when they finish reading a story. In this step, you will want to make a list of morals or life lessons that you can base your fairytale around.

For example, the moral of Cinderella is to show kindness to everyone , no matter how they treat you. It is her kindness that wins the Prince over and helps her to live happily ever after.

Another great example is Beauty and the Beast. The moral of this story is that you cannot judge people by their appearances. A beast may be kind at heart, but still appear to be ugly. In other words, what you see is not always what you get. Other great examples of morals can be found in reading Aesop’s fables, just check out this post on the top 12 life lessons from Aesop’s Fables .

In the next step, you should write down a character description for your hero. This character description should include personality traits, likes and dislikes, as well as a physical description.

Some common traits of your hero or heroine could be kind, humble, innocent and kind-hearted. They must be someone that your reader could relate to and feel something for. Therefore it is a good idea to make your main character a normal, everyday person who could change throughout the story. Think about Jack in Jack and the Beanstalk or Snow White.

For example, you could have the character be a gentle giant who enjoys painting or playing music . Your character does not necessarily have to be human! You can create a sea creature or even an object as the hero of your fairy tale.

Now it’s time to write a character description for the main villain in your fairytale. A fairy tale without a villain would be pretty boring. Create an evil character to test your heroes’ abilities and cause them some pain. The villain in fairy tales is normally the source of conflict and is likely to stop your hero from achieving their goals. Some common villains include the Big Bad Wolf, Cinderella’s stepmother or the evil queen.

For example, if you were writing a fairy tale about a brave knight and his quest for love, then your villain might be an evil dragon that is intent on destroying all that is good and pure.

Magic is the best part of any fairy tale. It is the magical element that guides your hero and helps them get a happy ending. Think about the fairy godmother’s role in Cinderella or the Genie in Aladdin.

When creating your magical element, use the “What if” technique. What if the teapot could talk? What if the cat had magical powers? This is a useful technique to help you think outside the box and create some really magical elements for your fairy tale. And remember any everyday object can have magical powers in a fairy tale.

For example, think of a fork that has magical powers. The fork can be used as a magic wand to help you find lost objects.

Different settings can create different moods in your fairy tale. For example, a nice little cottage in a forest is the perfect place to create a cosy, warm feeling. While a gloomy castle might set the scene of a dark, gothic fairy tale.

Other examples of common settings in fairy tales include an enchanted forest or a royal palace. When choosing your setting you can also choose the time period of your fairy tale. Common fairy tales were set in the 18 th or 19 th century, but what if your fairy tale was set in the future?

In fairy tales, the opening sentence normally begins with ‘Once upon a time…’ or ‘There once was a…’ and then goes on to describe the main character and the setting in great detail. You should also ideally mention the adversity the main character is facing at this point.

For example in Cinderella, the opening sentence could be:

‘Cinderella’s father had died when she was very young leaving her an orphan. Her stepmother hated her and treated her like a slave. She had to work day and night making dresses for the family while her stepmother wore beautiful gowns and ate rich food. Cinderella felt so sad that she often wept herself to sleep.’

Here we get a brief description of Cinderella, along with information on the pain she is feeling or her adversity.

The middle of a fairy tale is where the biggest conflict happens. It is also the longest part of most fairy tales. In this section of the story, the main character has to face their greatest challenge and overcome it. They need to either find something or do something that will help them in the battle they are fighting. It is also the part of the story that usually has the most action and emotion in it.

For example in Cinderella, when Cinderella’s stepmother destroys the dress that Cinderella plans on wearing to the ball, she must find another way to achieve her goal. At this point, the fairy godmother appears to Cinderella to offer a helping hand. The fairy godmother transforms Cinderella into a beautiful woman so that she can attend the ball.

This scene contains lots of conflict and drama. There is also a sense of urgency because Cinderella needs to get dressed fast if she wants to be able to attend the ball.

The most important part of your fairy tale is a happy ending. All fairy tales end in happy endings, so what is yours? Think about how the conflict in the fairy tale is resolved or how the villain gets defeated. For example in Cinderella, the glass slippers fit her foot, or in The Ugly Duckling, the duck turns into a beautiful swan. Overall the reader is left with a sense of warmth and optimism that the hero has overcome adversity and that good always wins in the end.

To get you started on writing your very own fairy tale below is a list of some writing prompts:

- A young boy discovers a magic lamp in his backyard that brings him to a mysterious world of fairies, witches, and monsters.

- A little girl finds a magic ring that transports her to a strange new world. The ring belongs to a friendly wizard who has been captured by an evil magician.

- A young man travels into the forest to seek the help of a wise old wizard. He learns that the wizard is actually a powerful sorcerer who has been trapped in a spell for centuries.

- An old man’s life is changed forever when he is visited by a fairy godmother who gives him three wishes. The first wish is for him to be rich; the second is to win the heart of a beautiful princess; the third is to be reunited with his long-lost son.

- A young girl finds a book of spells that allows her to transform into any animal she chooses.

- A young boy becomes the victim of a cruel trick played upon him by two evil brothers. He is turned into a pig and is forced to work on their pig farm.

- A young girl with a unique talent is chosen to go on an adventure to find a powerful artefact that will help her family save their farm.

- A young man travels to a magical land where he meets a wise old wizard who helps him defeat a wicked king and restore peace to his kingdom.

- A young boy discovers a magical stone that allows him to travel through time. He travels back in time to visit his grandparents and see what life was like when they were children.

- A young boy befriends a talking cat who teaches him how to use magic to defeat the evil forces trying to take over his kingdom.

For more fairy tale inspiration, see our post on 110+ fairy tale writing prompts with a generator .

Common Questions

The most common way to start a fairy tale is with, “Once upon a time…”. You may also start a fairy tale with the lines, “Long, long ago…” or “There once was a…”. If you want to make your fairy tale sound more modern, you could begin with a question. For example, “Have you ever heard of the legend of the golden sword?” – This is especially great for when you are re-telling a famous fairy tale.

Every fairy tale has 5 elements that make them a fairy tale, these include:

- Hero/Heroine & Villain: Good versus evil is a common theme in fairy tales. Traditionally, this involves a kind-hearted hero against an evil character. Heroes in fairy tales don’t always need to be purely kind, they can have a dark side making your story more interesting to read.

- Magic: A fairytale with no magic, is no fairy tale at all! Think curses, magical spells and enchanted items. Magic can be the root of evil, and it can be the only saviour in a tough situation for your hero or heroine.

- Conflict & Resolution: Every story needs some sort of conflict. A challenge your hero must solve. The bigger the conflict the better. The key to good conflict in a fairy tale is to make the conflict feel impossible to solve. Until the last key moment, where your hero comes out on top.

- Moral/Lesson : The reason why fairy tales are so popular is because of the life lessons they can offer to readers. The most common lesson learned from most fairy tales is that being kind can beat any evil in the world, and no matter who you are, dreams do come true!

- A Happy Ending: The majority of fairy tales end with a traditional, “Happily ever after” ending. The hero overcomes their challenge and celebrates their win – The end. The princess marries her prince, the poor boy never feels poor again and the Queen never feels alone again. More modern fairytales are moving away from happy endings to ending on a cliffhanger or with a sad ending.

For general stories, you might be interested in this post on the five elements of stories explained with examples .

A basic fairy tale structure starts with an opening paragraph to describe the setting and the hero. This leads to the problem or conflicts the hero is facing. Where the hero will have to either go on a journey or become stronger in order to overcome this challenge. Finally, the challenge is solved and everyone lives happily ever after.

There is no exact amount of words for how long a fairy tale should be. It depends on your target audience and the plot of the fairy tale.

Some classic fairy tales, such as “The Three Little Pigs” or even “Red Riding Hood” are just a few paragraphs long. While modern adaptions of fairy tales like Cinderella or even Beauty and the Beast are much longer spanning around 50 pages. There are also fairy tale chapter books, such as The Enchanted Forest Chronicles series by Patricia C. Wrede which includes four chapter books in the series.

In general, a fairy tale should be of an appropriate length to effectively convey its themes and messages, without becoming tedious or losing the reader’s attention. Moreover, the length may vary depending on the age range of the target audience. Younger children tend to prefer shorter stories, whereas older children and adults can typically handle longer and more intricate tales.

Writing a good fairy-tale means using the right technique. Below are some writing techniques that many authors use to create magical fairy tales:

- Vivid Imagery: Fairy tales often use vivid and descriptive language to create rich and detailed imagery. This can help to transport the reader to the fantastical world of the story.

- Simple Language: Fairy tales are typically written in simple and straightforward language, making them accessible to a wide range of readers. This also allows the author to focus on the story and its themes, rather than complex language or sentence structure.

- Symbolism : Fairy tales often use symbolism to convey deeper meaning and add layers to the story. For example, a character might represent a particular virtue or vice, or an object might symbolize a particular theme or idea.

- Repetition: Many fairy tales use repetition, such as repeating phrases or events, to create a sense of rhythm and structure in the story. This can help to make the story more memorable and engaging for readers.

- Foreshadowing : Fairy tales often use foreshadowing, such as hinting at events that will occur later in the story, to create tension and build suspense. This can help to keep readers engaged and invested in the story.

- Transformation : Many fairy tales involve characters undergoing transformations, either physically or emotionally. These transformations can help to convey important themes and messages, such as the power of love or the importance of inner beauty.

Still, struggling to write a fairy tale? Here are some bonus tips to help you get writing.

- When lost for inspiration, try reading fairy tales from Hans Christian Andersen and Brother Grimm and then try re-telling these fairy tales in your own way.

- Keep it simple, use language that all age groups can understand and read and avoid using complicated and long sentences.

- Include words like, “Once upon a time” and “Happily ever after”.

- Things happen in threes or sevens – It’s a common fairy tale tradition. This could relate to characters, events or places. For example the seven dwarfs in snow white or the three little pigs.

- Send your hero on a quest or journey and show the changes to them relating to their behaviour and personality on the way.

- Common fairy tales follow the Good vs. Evil story plot.

- Villains or evil characters are punished for their acts and the hero is rewarded in some way.

- The challenge or obstacle your heroes faces must be impossible to overcome without the help of a magical character or some special abilities. For example, only true love could break the beast’s curse in Beauty and The Beast.

Need more help with writing a fairy tale? We recommend the book, Lessons from Grimm by Shona Slayton (Amazon Affiliate link), which you can purchase from Amazon. It is a must-have for all fairy tale writers and authors. This book offers a basic formula for writing your own fairy tale, along with practical tips to help you.

Another recommended book for fairy tale writing is, How to Write a Fractured Fairy Tale (Amazon Affiliate link). This illustrated guide is great for kids who want to write their own fairy tales. It provides guidance on outlining your story’s plot , character development , editing your fairy tale and even comes with a range of fun activities.

Now you know the essential steps to write a fairy tale it’s time for you to get writing! Best of all, you can even use our online story creator to write and publish your own stories!

Marty the wizard is the master of Imagine Forest. When he's not reading a ton of books or writing some of his own tales, he loves to be surrounded by the magical creatures that live in Imagine Forest. While living in his tree house he has devoted his time to helping children around the world with their writing skills and creativity.

Related Posts

Comments loading...

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Literature

Essay Samples on Fairy Tale

Beauty and the beast: the adaptation of the famous fairy tale.

The name of the play is “Beauty and the Beast.” It was executed at Disneyland Hollywood Studios, Bay Lake, Florida, USA on September 6, 2016. It is supervised and conducted, of course, because it is a play in Disneyland, by The Walt Disney Company. It...

- Beauty and The Beast

Beauty and the Beast: The Historical Relation of the Tale

Madame de Villeneuve’s The Story of The Beauty and The Beast is a fictional story. Set in France during the eighteenth century, in a town near the countryside. The story is told in third person point of view. Although it is fictional, many things can...

Prominent Trickster Tales In British Literature

A trickster is a recurrent figure in world folklore and literature. It is a cunning, deceitful, and mischievous character that upsets established hierarchies, conventions, and rules by playing tricks. Tricksters could be human, divine, or anthropomorphized characters possessing supernatural powers. Native American, African-American, and European...

- Canterbury Tales

- The Pardoner's Tale

Adverse Morality Of Fairy Tales And A False Perception Of Reality That Comes With Them

In Valerie Gribben’s essay, Practicing Medicine Can Be Grimm Work, Gribben recounts her experiences while working for a hospital. She explains that while she learned how to physically treat a wide range of ailments and conditions, she came to realize that she lacked any sort...

The Tale of the Fallen Angel: Losing Hope in God

Who knows the world at its core, knows what moves the rain and earth, has the face and mind of a god, but is a giant at his birth. Proud, Egoistic Loki knows what you envision in your petty little mind, he can work you...

- Fallen Angels

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

Traditional Fairy Tales Are More Relevant Than Modern Interpretations

How would you feel if you were replaced by a cheap clone and be considered less relevant in society? You wouldn’t? Traditional fairy tales are stories told to children for entertainment purposes, usually about magical beings, queens, kings, dragons and magical settings. Currently there has...

- Little Red Riding Hood

Different Interpretations of Famous Red Riding Hood

The fairy tale “Little Red Riding Hood” has been around for years, and throughout these years has been twisted into various interpretations. We of course have the ‘Red Riding Hood’ we all have familiarization with, by Charles Perrault, which tells the tale of a young...

The Essential Lessons from the Rapunzel Story

In addition to power and domesticity, power and misery are also interconnected throughout Rapunzel. Although wandering is mostly seen as a fear, which is negative and frightening because it lacks support from family, it can also be viewed as a positive experience. For instance, when...

- Gender Equality

Analyzing the Tale of Rapunzel by the Brothers Grimm From a Feminist Perspective

Analyzing the Tale of “Rapunzel” by the Brothers Grimm: A Feminist Perspective In this essay I aim to deconstruct the classic folk-tale, “Rapunzel/Rampion”, with specific attention to the Brothers Grimm iteration from their seventh version of the Kinder- und Hausmärchen. I am focusing particularly on...

- Empowerment

Alternation of Themes and Symbols in Fairy Tales: Analysis of Shrek

The End of Fairy Tales? How Shrek and Friends Have Changed Children’s Stories, written by James Poniewozik, provides criticism on how children are exposed to fairy tales in today’s society and how they are not being presented in the traditional storyline. In particular, Poniewozik uses...

Once Upon a Time: Pan’s Labyrinth as a Fairytale

Pan’s Labyrinth is one of Guillermo del Toro’s masterpieces. This contentious film juxtaposes the colorful world of fantasy and the harsh world of reality that is set in the aftermath of the Spanish civil war. Upon watching the film, viewers would argue whether the film...

- Pan's Labyrinth

The Evolution and Development of Classic Fairy Tales

Fairy tales have evolved over time: narratives that were originally full of harrowing violence have been adapted into bedtime stories. As time goes on, more and more versions of each tale appear, in print or else on film. But why do we bother using the...

Once Upon a Time: A Tale of the Disney ‘Child Actors’

When Disney transitioned from the movie medium to the television one, it incorporated new features to efficiently adapt itself to this new form. The newest and most evident element that was implemented was the constant use of the same young actors, dubbed as ‘child actors.’...

Literary Devices and Biblical Themes in Snow White

From an Archetypal perspective, Little Snow-White is a fairytale in which portrays different meanings and hidden messages through patterns, symbols, and characters. Repetition often occurs within this fairytale to draw attention and thought onto a certain aspect to create a main focus (focal point). By...

- Literary Devices

The False Depiction of Love in Fairy Tales

We are born in a world that feeds us fairytales. We grow up fantasizing about our prince charming, our fairytale love, and our happily ever after. The love stories we read keeps us entertained, though we probably know the truth. Love is not a fairytale....

- Types of Love

Analysis of Traditional Fairy Tale Elements in "Shrek"

Once upon a time an Ogre left his swamp to go save the princess. Oh wait, aren’t Ogre’s supposed to kill princesses? So, why didn’t the actual prince save the princess? Well, in the movie Shrek 2, it was a total reversal of the traditional...

Tim Burton and the Disturbing Depiction of Fairy-Tales in His Work

Tim Burton is an American director, who specialises in fantasy dramas that rely heavily on gothic styles and conventions and who has created an oeuvre that makes him one of the most famous directors in Hollywood today. This is the presentation of my research that...

- Gothic Literature

Depiction of Female Characters in Disney as per Cinderella

“And they all lived happily ever after”. Throughout a child's life, someone has once read to them a fairytale. Every word and every picture of fairytales usually play a magical image in a person's mind. While reading a fairytale it can open magical worlds, possibilities,...

The Alternative Beauty of Cinderella's Fairy Tale

Fairy tales function as a medium for spreading moral values in communities throughout history. For instance, one particularly popular story is “Cinderella” by Charles Perrault. It teaches children, in a plain manner, the importance of kind-heartedness through depicting the dramatic change of the fate of...

Fairy Tales In Modern World In "Once Upon A Time" TV Show

Once upon a time, there was a TV show on ABC based on fairy tales, but with a twist. This TV show was called “Once Upon a Time. ” These stories have been modified and mashed to create a sense of imagination and creativity to...

- Reality Television

Fairy Tales Are Very Fictional Giving False Hopes To Children

In the old time fairy tales were very popular because since there was no technology, it means no television, neither any network to use. Also, at that time many mothers have to find a way for their children to belief in something and be entertaining....

- Childhood Development

Comparative Analysis Of Angela Carter’s “The Tiger’s Bride” & Beaumont’s “Beauty & The Beast”

Throughout the decades, it is common for literature, especially children’s literature to have several different versions. This can be due to the fact that the meaning of the story changes to meet the current needs or messages of a culture. For instance, the classic fairytale...

Review Of "The Wife Of Bath Tales" By Geoffrey Chaucer

The Wife Of Bath Tales does indeed have a moral to its story and its moral teaches young girls how they should not to be treated and that they should be treated/showed equality and respect to the highest extent just like their male counterparts. It...

- Geoffrey Chaucer

- Literature Review

Best topics on Fairy Tale

1. Beauty and the Beast: The Adaptation of the Famous Fairy Tale

2. Beauty and the Beast: The Historical Relation of the Tale

3. Prominent Trickster Tales In British Literature

4. Adverse Morality Of Fairy Tales And A False Perception Of Reality That Comes With Them

5. The Tale of the Fallen Angel: Losing Hope in God

6. Traditional Fairy Tales Are More Relevant Than Modern Interpretations

7. Different Interpretations of Famous Red Riding Hood

8. The Essential Lessons from the Rapunzel Story

9. Analyzing the Tale of Rapunzel by the Brothers Grimm From a Feminist Perspective

10. Alternation of Themes and Symbols in Fairy Tales: Analysis of Shrek

11. Once Upon a Time: Pan’s Labyrinth as a Fairytale

12. The Evolution and Development of Classic Fairy Tales

13. Once Upon a Time: A Tale of the Disney ‘Child Actors’

14. Literary Devices and Biblical Themes in Snow White

15. The False Depiction of Love in Fairy Tales

- A Raisin in The Sun

- Hidden Intellectualism

- William Shakespeare

- Sonny's Blues

- American Literature

- A Christmas Carol

- A Thousand Splendid Suns

- Ernest Hemingway

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Essay on My Favourite Story Book Cinderella

Students are often asked to write an essay on My Favourite Story Book Cinderella in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on My Favourite Story Book Cinderella

Introduction.

Cinderella, my favourite storybook, is a classic tale of resilience and dreams coming true.

The story revolves around a kind and gentle girl, Cinderella, who lives with her wicked stepmother and stepsisters.

Cinderella, the protagonist, is a symbol of humility and kindness. The antagonists are her stepmother and stepsisters.

Life Lessons

The story teaches us that goodness always triumphs over evil, and dreams do come true.

Cinderella, with its magical and inspiring storyline, will always be my favourite storybook.

250 Words Essay on My Favourite Story Book Cinderella

Cinderella, a timeless classic, has been my favourite storybook since childhood. Its enchanting narrative, captivating characters, and underlying themes of resilience and hope have left an indelible impression on me.

The Enthralling Narrative

The story revolves around a young girl, Cinderella, subjected to harsh treatment by her stepmother and stepsisters. Despite her circumstances, she remains kindhearted and patient. The narrative’s magic lies in its transformative arc, where Cinderella’s life changes dramatically through an enchanted pumpkin, mice, and a fairy godmother.

Resilience Personified

Cinderella’s character is a testament to resilience. Her ability to maintain her kindness and optimism amidst adversity has always been inspiring. She teaches us that no matter how bleak the circumstances, one should never lose hope or compromise one’s goodness.

Symbolism and Themes

The story of Cinderella is replete with symbolism and themes that resonate even today. The glass slipper is a symbol of Cinderella’s true identity, which cannot be hidden or altered. The striking of midnight signifies the transient nature of materialistic allure. The story also underscores the themes of justice and karma, where the good is rewarded, and the wicked are punished.

Cinderella is more than just a fairy tale. It is a narrative that encourages its readers to remain hopeful and kind, even in the face of adversity. This storybook has greatly influenced my outlook towards life, making it my favourite. In essence, Cinderella is a beacon of hope, resilience, and the ultimate triumph of good over evil.

500 Words Essay on My Favourite Story Book Cinderella

“Cinderella,” a timeless classic, has been my favourite story book since childhood. The enchanting tale, brimming with hope, resilience, and magic, has been a source of inspiration, providing valuable life lessons that have shaped my perspective on various aspects of life.

“Cinderella” is not merely a fairy tale about a girl who becomes a princess. It is a profound narrative that explores themes of resilience, kindness, and the transformative power of hope. Cinderella, the protagonist, symbolizes the human spirit’s resilience in the face of adversity. Despite her harsh circumstances, she remains kind and hopeful, demonstrating that adversity should not define one’s character.

The story of Cinderella imparts crucial life lessons. It teaches us that kindness and humility are virtues that can overcome the harshest of adversities. Cinderella’s character embodies these virtues, and her story serves as a reminder that these qualities are often rewarded. The story also emphasizes the importance of hope. Cinderella’s unwavering hope, even in her dire circumstances, is a testament to the power of positive thinking and the belief in better days.

The Element of Magic

The element of magic in “Cinderella” is an essential component that adds charm and allure to the story. The fairy godmother, the magical transformation, and the iconic glass slipper serve as metaphors for the unexpected possibilities that life holds. They symbolize that magical transformations can occur in our lives when we least expect them, provided we remain hopeful and resilient.

Impact on Readers

“Cinderella” has a profound impact on its readers. It serves as a beacon of hope, teaching us to remain hopeful and resilient in the face of adversity. It encourages us to believe in the possibility of a better future, no matter how bleak the present may seem. This timeless fairy tale has the power to inspire and motivate, instilling values of kindness, humility, and resilience.

In conclusion, “Cinderella” is my favourite story book not just for its enchanting tale, but for the profound life lessons it imparts. It is a narrative of hope, resilience, and magic that continues to inspire readers of all ages. The story of Cinderella remains a timeless classic, reminding us of the transformative power of hope, the virtue of kindness, and the magic that lies in believing in oneself.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Cinderella

- Essay on Church

- Essay on Christianity

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Folktales (or folk tales) are stories passed down through generations, mainly by telling. Different kinds of folktales include fairy tales (or fairytales), tall tales, trickster tales, myths, and legends. You’ll find all of those here. (Other legends—shorter ones—can be found in a special section of their own.) If you are a publisher or other content acquirer, please see also Aaron’s Rights & Permissions .

Quackling: A Not-Too-Grimm Fairy Tale

After waiting in vain for the King to repay a loan, Quackling wants his money back. GENRE: Folktales CULTURE: France THEME: Benefits of friendship AGES: 3–9 LENGTH: 750 words

- About the Picture Book

- Aaron’s Extras

The Adventures of Mouse Deer: Favorite Folk Tales of Southeast Asia

Mouse Deer is small, and many animals want to eat him—but first they have to catch him! GENRE: Folktales, trickster tales CULTURE: Indonesian, Malaysian THEME: Wits vs. power AGES: 4–9 LENGTH: 1800 words (700+400+700)

- About the Early Reader

One‑Eye! Two‑Eyes! Three‑Eyes!: A Very Grimm Fairy Tale

Two‑Eyes is different from her sisters and others, because she has just two eyes. GENRE: Folktales CULTURE: German THEME: Being different AGES: 7–12 LENGTH: 1400 words

King o’ the Cats

Peter is notorious for telling wild stories—so who will believe him now, with his crazy claims about cats? GENRE: Folktales, tall tales, ghost stories CULTURE: British (English) THEME: Credibility AGES: 4–12 LENGTH: 1500 words

The Princess Mouse: A Tale of Finland

When a young man seeks a wife by way of family tradition, he finds himself engaged to a mouse. GENRE: Folktales CULTURE: Finnish THEME: Kindness, humility, integrity AGES: 4–12 LENGTH: 1800 words

The Baker’s Dozen: A Saint Nicholas Legend

Van Amsterdam, the baker, is as honest as he can be—but he may have something left to learn. GENRE: Legends, St. Nicholas tales CULTURE: American (Dutch colonial) THEME: Generosity AGES: 4–13 LENGTH: 900 words

The Sea King’s Daughter: A Russian Legend

A poor musician is invited to play in the Sea King’s palace, where he’s offered more than riches. GENRE: Legends, folktales, epic ballads CULTURE: Russian (medieval) THEME: Making choices; value of arts AGES: 7 and up LENGTH: 1600 words

Master Man: A Tall Tale of Nigeria

Shadusa thinks he’s the strongest man in the world—till he meets the real Master Man. GENRE: Tall tales, folktales CULTURE: West African, Nigerian THEME: Machismo AGES: 5 and up LENGTH: 1250 words

The Magic Brocade: A Tale of China

To save his mother’s life, a young man must retrieve her weaving from the fairies of Sun Palace. GENRE: Folktales CULTURE: Chinese THEME: Following dreams; creative process AGES: 4 and up LENGTH: 1700 words

The Princess and the God: A Tale of Ancient India

The princess Savitri must use all her wit and will to save her husband from the god of death. GENRE: Myths, folktales, legends CULTURE: Asian Indian (ancient), Hindu THEME: Heroines, determination AGES: 7 and up LENGTH: 1300 words

The Legend of Slappy Hooper: An American Tall Tale

Slappy is the world’s biggest, fastest, bestest sign painter, but he’s too good —his pictures keep coming to life. GENRE: Tall tales, folktales CULTURE: American THEME: Pursuit of excellence AGES: 5–12 LENGTH: 1300 words

The Crystal Heart: A Vietnamese Legend

The mandarin’s daughter did not really see the boatman who sang from the river, but she’s sure he’s her destined love. GENRE: Folktales CULTURE: Vietnamese THEME: Kindness, false imagining AGES: 7 and up LENGTH: 1500 words

Forty Fortunes: A Tale of Iran

When a young man’s wife makes him pose as a fortuneteller, his success is unpredictable. GENRE: Folktales CULTURE: Iranian (Persian), Middle Eastern THEME: Pretension AGES: 7 and up LENGTH: 1600 words

Master Maid: A Tale of Norway

When Leif goes to work for the troll, only the advice of a remarkable young woman can save him from his foolishness—if only he’ll listen! GENRE: Folktales, tall tales CULTURE: Norwegian THEME: Stubbornness, heroines AGES: 4 and up LENGTH: 2200 words

The Enchanted Storks: A Tale of Bagdad

The Calif and his Vizier try a spell that changes them into storks, then find they can’t change back. GENRE: Fairy tales, folktales CULTURE: Iraqi, Middle Eastern THEME: Recklessness AGES: 7 and up LENGTH: 2000 words

The Gifts of the Grasscutter: A Tale of India and Pakistan

Wali Dad, a humble grasscutter, never asked for wealth—so why can’t he give it away? GENRE: Folktales CULTURE: Asian Indian, Pakistani THEME: Generosity AGES: 4 and up LENGTH: 1500 words

The Story Spirits: A Tale of Korea

As a boy, Dong Chin never shared the stories he heard—and now, on his wedding day, the stories want revenge. GENRE: Folktales CULTURE: Korean THEME: Sharing stories AGES: 7–12 LENGTH: 1700 words

I Know What I Know: A Tale of Denmark

When his daughters all marry trolls, Ulf learns some new tricks from the husbands—or thinks he does. GENRE: Folktales CULTURE: Danish THEME: Lack of full knowledge AGES: 4–12 LENGTH: 700 words

The Gifts of Friday Eve: A Tale of Iran

Though a woodcutter’s luck could hardly be worse, help is closer than he knows. GENRE: Folktales, fables CULTURE: Iranian (Persian), Middle Eastern THEME: Thankfulness, sharing AGES: 5–12 LENGTH: 1200 words

When the Twins Went to War: A Fable of Far East Russia

The war-loving men of the Beldy clan are once more off to battle—but why are the wise young twins going with them? GENRE: Folktales, fables, legends CULTURE: Russian (Far East, native) THEME: Militarism AGES: 7–12 LENGTH: 1200 words

The Hidden One: A Native American Legend

The invisible hunter at the end of the village is sought as husband by every village maiden—but will Little Scarface even dare to try? GENRE: Folktales, Cinderella tales CULTURE: Native American, Canadian THEME: Self-esteem, heroines AGES: 7 and up LENGTH: 1200 words Translations — | German |

The Boy Who Drew Cats: A Tale of Japan

A boy gets in trouble when he can’t stop drawing cats. GENRE: Fairy tales CULTURE: Japanese THEME: Individuality; value of arts AGES: 4–10 LENGTH: 1000 words

How Frog Went to Heaven: A Tale of Angola

Frog helps a young man who wants to marry the Sky Maiden. GENRE: Folktales, myths CULTURE: African, Angolan THEME: Inventiveness, determination AGES: 3–9 LENGTH: 1000 words

The Four Puppets: A Tale of Burma

A young man seeking his fortune gets differing advice from four talking puppets. GENRE: Folktales, fairy tales CULTURE: Burmese, Buddhist THEME: Virtue AGES: 7 and up LENGTH: 1500 words

The Master of Masters: A Tale of Norway

Jesus and St. Peter meet an arrogant blacksmith. GENRE: Folktales, tall tales, Jesus tales CULTURE: Norwegian, Christian THEME: Boasting AGES: 7 and up LENGTH: 500 words

The Wings of the Butterfly: A Tale of the Amazon Rainforest

A native girl becomes lost in the forest, where she meets with magical creatures. GENRE: Folktales CULTURE: South American (native) THEME: Going beyond AGES: 7–12 LENGTH: 1700 words

Lars, My Lad!: A Tale of Sweden

A penniless duke finds a magic charm that controls an invisible helper. GENRE: Folktales CULTURE: Swedish THEME: Wealth vs. friendship AGES: 7 and up LENGTH: 2700 words

The Calabash Kids: A Tale of Tanzania

The prayers of a lonely woman are answered when her gourds change into children. GENRE: Folktales CULTURE: African, Tanzanian THEME: Name-calling AGES: 3–9 LENGTH: 1100 words

The Millionaire Miser: A Buddhist Fable

Sushil is so stingy, even a god takes notice. GENRE: Fables, folktales CULTURE: Asian Indian, Buddhist THEME: Stinginess AGES: 5–12 LENGTH: 1000 words

Too-too-moo and the Giant: A Tale of Indonesia

A village girl must feed a giant every day, or he’ll eat her instead. GENRE: Folktales CULTURE: Indonesian, Javanese THEME: Courage, heroines AGES: 5–9 LENGTH: 1000 words

The Lady of Stavoren: A Dutch Legend

A rich but selfish lady sends her sea captain fiancé in quest of the most precious thing in the world. For a briefer telling, see “ The Most Precious Thing in the World ” in the Legends . GENRE: Legends, folktales CULTURE: Dutch THEME: Excessive pride vs. love AGES: 7 and up LENGTH: 1100 words

Mop Top: A Tale of Norway

A wild princess must get back her sister’s head from a gang of troll girls. GENRE: Folktales, tall tales CULTURE: Norwegian THEME: Heroines AGES: 5–12 LENGTH: 1300 words

The Boy Who Wanted the Willies

Hans has never in his life been frightened—but a night in a haunted castle should finally give him his chance. GENRE: Folktales, tall tales, ghost stories CULTURE: German, European THEME: Fearlessness AGES: 5–12 LENGTH: 1300 words

The Wicked Girl: A Tale of Turkey

A lovely slave girl matches wits with a handsome but vengeful restaurant owner. GENRE: Folktales, trickster tales CULTURE: Turkish, Middle Eastern THEME: Heroines AGES: 9 and up LENGTH: 1150 words

Kings for Breakfast!: A Hindu Legend

King Vikram must rescue a magic goose from King Karan and discover the secret of his wealth. GENRE: Folktales, legends, tall tales CULTURE: Asian Indian, Hindu THEME: Generosity, self-sacrifice AGES: 5–12 LENGTH: 1300 words

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Fairy Tale — Gender Roles And Stereotypes in Cinderella

Gender Roles and Stereotypes in Cinderella

- Categories: Fairy Tale Social Justice

About this sample

Words: 562 |

Published: Mar 16, 2024

Words: 562 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1708 words

3 pages / 1321 words

3 pages / 1270 words

3 pages / 1323 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Fairy Tale

Bettelheim, Bruno. 'The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales.' Vintage, 2010.Perrault, Charles. 'Cinderella.' Translated by A. E. Johnson, 1920.Disney, Walt. 'Cinderella.' Walt Disney Pictures, [...]

In the realm of classic fairy tales, Cinderella undoubtedly reigns as one of the most beloved and enduring stories. However, the version presented by Jack Zipes in his essay, "Cinderella," challenges traditional interpretations [...]

Cinderella, a classic fairy tale loved by many, has been a staple in children's literature for generations. However, as society has evolved and become more aware of gender roles and stereotypes, many have begun to question the [...]

Ashputtel, also known as Cinderella, is a popular fairy tale that has been told and retold in various forms throughout history. One of the most well-known versions of this story was written by the Grimm Brothers, Jacob and [...]

The story of Sindbad the Sailor, found in “The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments” and filled with countless economic transactions, can be understood through the application of different economic models to reveal the motives and [...]

As a child coming of age in the mass-consumerist, technologically innovative, and media-influenced climate of the twentieth century, one’s exposure to fairy tales will have likely been informed by recurrent viewings of Disney [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Free Samples

- Premium Essays

- Editing Services Editing Proofreading Rewriting

- Extra Tools Essay Topic Generator Thesis Generator Citation Generator GPA Calculator Study Guides Donate Paper

- Essay Writing Help

- About Us About Us Testimonials FAQ

- Studentshare

- The Book Grimm Fairy Tales

The Book Grimm Fairy Tales - Essay Example

- Subject: Literature

- Type: Essay

- Level: College

- Pages: 2 (500 words)

- Downloads: 3

- Author: klingkennith

Extract of sample "The Book Grimm Fairy Tales"

- Cited: 0 times

- Copy Citation Citation is copied Copy Citation Citation is copied Copy Citation Citation is copied

CHECK THESE SAMPLES OF The Book Grimm Fairy Tales

Iron hans (children literature), evluation of narrative work of art, multicultural education and books that shaped the 20th century, association of grimms fairy tales with childhood, happy endings in childrens literature - hope, dreams, maturity, and gender, folklore of the human mind, taming the wild things for children, horror in childrens tales and stories.

- TERMS & CONDITIONS

- PRIVACY POLICY

- COOKIES POLICY

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Short Essay on Fairy Tales in 100 WORDS. Fairy tales are the pleasures of childhood. There is almost no one who has not read a fairy tale. A fairy tale is a fantasy story that has humans, animals, birds, magicians, kings and queens, princes, and princesses. It also has fairies. The animals and birds in fairy tales can talk. Fairy tales are ...

2 pages / 871 words. This essay is an evaluation of psychological interpretation of fairy and folklore tales looking at the topic of sibling's rivalry and oedipal period in Cinderella. There is a use of Freud Sigmund psychological theory to interpret.

Cinderella is a celebrated classic tale representing myth-like elements such as unfair domination of evil powers resulting into glorious victory of the good ones. Nowadays there exist thousands of versions of the story celebrated all over the world. At the core of the plot invariably lies a story of a fortunate young girl living in ill-fated ...

According to renowned child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, fairy tales help children make sense of the world around them and understand complex emotions. For example, the tale of "Cinderella" teaches perseverance and the importance of kindness, while "Little Red Riding Hood" warns against the dangers of trusting strangers.

2. Create your hero. In the next step, you should write down a character description for your hero. This character description should include personality traits, likes and dislikes, as well as a physical description. Some common traits of your hero or heroine could be kind, humble, innocent and kind-hearted.

Alternation of Themes and Symbols in Fairy Tales: Analysis of Shrek. 11. Once Upon a Time: Pan's Labyrinth as a Fairytale. 12. The Evolution and Development of Classic Fairy Tales. 13. Once Upon a Time: A Tale of the Disney 'Child Actors' 14. Literary Devices and Biblical Themes in Snow White. 15. The False Depiction of Love in Fairy ...

500 Words Essay on Cinderella Introduction to Cinderella. Cinderella, a renowned fairy tale, has been an integral part of our childhood, transcending generations and cultures. It is a narrative that has been adapted in various forms, from books to films, and continues to captivate audiences.

500 Words Essay on My Favourite Story Book Cinderella Introduction "Cinderella," a timeless classic, has been my favourite story book since childhood. The enchanting tale, brimming with hope, resilience, and magic, has been a source of inspiration, providing valuable life lessons that have shaped my perspective on various aspects of life.

Page 1 of 50 - About 500 essays. Decent Essays. Fairy Tale Fairy Tales. 1186 Words; ... However, the essay "Why Fairy Tales Matter: The Performative and the Transformative" by Maria Tatar proposes a different view, one deeper than therapeutic realms. She believes that children must read fairy tales because. 1981 Words;

Cinderella: Character Analysis. Cinderella is a classic fairy-tale character who has been portrayed in various forms of literature, film, and theater. The story of Cinderella revolves around a young girl who is mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters but ultimately finds her happily ever after with the help of a fairy godmother.

Paper Type: 500 Word Essay Examples. Most people grow up reading fairy tales and accustoming how such stories end - with the marriage of the beautiful princess and charming prince and the words "and they lived happily ever after." The perception of relationships among lovers, family members, and ordinary people in fairy tales is highly ...

Master Man: A Tall Tale of Nigeria. Shadusa thinks he's the strongest man in the world—till he meets the real Master Man. GENRE: Tall tales, folktales. CULTURE: West African, Nigerian. THEME: Machismo. AGES: 5 and up. LENGTH: 1250 words. About the Picture Book. Aaron's Extras.

Fairy Tale Story "The Bronze Ring" is an important fairy tale that makes the opening story of Andrew Lang's ic selection of popular fairy tales titled The Blue Fairy Book. Significantly, the main story of this fairy narrates how a gardener's son wins the hands of the princess of the kingdom, with the help of a bronze ring that he got as ...

Fairy tales have been an intrinsic part of human culture for centuries, transcending geographic boundaries and evolving through time. These stories, often characterized by fantastical elements, mythical creatures, and moral lessons, are far more than mere bedtime stories for children.

Get original essay. One of the most prominent gender roles depicted in Cinderella is the idea of women being passive and submissive. From the beginning of the story, Cinderella is portrayed as a meek and obedient character who endures the mistreatment of her stepfamily without protest. This perpetuates the stereotype of women as being passive ...

Tales. In the 17th century, fairy tales were miles apart from the versions we read and watch today. Endings would not always be as happy as we know them to be and there were far more complications, perversity and brutalities. For instance, in Sleeping Beauty, the girl is not kissed and awakened by her prince; rather, he rapes her and makes her ...

Your fairy tale should be between 300 and 500 words long; it can have similarities to other fairy tales (retelling "Rapunzel" with a different culture and system of magic, for example) but must be ...

The paper "The Book Grimm Fairy Tales" discusses that the brothers Grimm have been credited with introducing us to a number of fairytales. However, with the passage of ... Essay Topic Generator Thesis Generator Citation Generator GPA Calculator Study Guides Donate Paper. ... (500 words) Downloads: 3; Author: klingkennith ...

Fairy Tales. In all three fairy tales we have studied so far, there is a male "beast" figure included; the wolf in "Little Red Cap," the wildman in "Iron Hans," and finally Beast in "Beauty and the Beast." These "beats" have words such as wicked, wild, or even frightful to describe them. Although they are all such different stories ...

Page 1 of 50 - About 500 Essays Good Essays. fairy tales. 3580 Words; 15 Pages; fairy tales. Fairy tales have been part of children's culture for many years. They have been the favorite bed time stories and the doors to an alternate world of imagination. ... Fairy tales of the past were often full of macabre and gruesome twists and endings ...