- Open access

- Published: 08 July 2020

A critical interpretive synthesis of the roles of midwives in health systems

- Cristina A. Mattison ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7210-0690 1 ,

- John N. Lavis 2 ,

- Michael G. Wilson 2 ,

- Eileen K. Hutton 1 &

- Michelle L. Dion 3

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 18 , Article number: 77 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

9348 Accesses

17 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

Midwives’ roles in sexual and reproductive health and rights continues to evolve. Understanding the profession’s role and how midwives can be integrated into health systems is essential in creating evidence-informed policies. Our objective was to develop a theoretical framework of how political system factors and health systems arrangements influence the roles of midwives within the health system.

A critical interpretive synthesis was used to develop the theoretical framework. A range of electronic bibliographic databases (CINAHL, EMBASE, Global Health database, HealthSTAR, Health Systems Evidence, MEDLINE and Web of Science) was searched through to 14 May 2020 as were policy and health systems-related and midwifery organisation websites. A coding structure was created to guide the data extraction.

A total of 4533 unique documents were retrieved through electronic searches, of which 4132 were excluded using explicit criteria, leaving 401 potentially relevant records, in addition to the 29 records that were purposively sampled through grey literature. A total of 100 documents were included in the critical interpretive synthesis. The resulting theoretical framework identified the range of political and health system components that can work together to facilitate the integration of midwifery into health systems or act as barriers that restrict the roles of the profession.

Conclusions

Any changes to the roles of midwives in health systems need to take into account the political system where decisions about their integration will be made as well as the nature of the health system in which they are being integrated. The theoretical framework, which can be thought of as a heuristic, identifies the core contextual factors that governments can use to best leverage their position when working to improve sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Midwives’ roles in sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) continue to evolve and an understanding of the profession’s role in health systems is essential in creating evidence-informed policies. Countries across all income levels face challenges with providing high-quality SRHR and achieving effective coverage [ 1 ]. National or sub-national SRHR policies often do not include the midwifery workforce or account for the professions’ role in the provision of high-quality care [ 1 ]. The lack of conceptual clarity regarding the drivers of midwives’ roles within health systems, ranging from their regulation and scope of practice to their involvement in care, has resulted in significant variability both within and across countries on how the profession is integrated into health systems.

Research on midwifery care has demonstrated that the profession delivers high-quality SRHR services [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Care provided by midwives who are trained, licensed and regulated according to international standards is associated with improved health outcomes [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. While midwifery care is associated with positive outcomes, it is an area that is under-researched [ 8 ]. This is particularly true in relation to how political and health system factors influence the profession’s role in health systems. As such, the roles of midwives in health systems are not clearly understood, which continues to challenge the profession’s ability to work effectively in collaborative and interprofessional settings.

Midwifery research is often dichotomised by the development status of the jurisdiction of focus — high-income countries (HICs) compared to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In HICs in general, midwives’ roles are focused on primary care to low-risk pregnant people through pregnancy, labour and a limited post-partum period [ 9 ]. In comparison, in LMICs, midwives’ scope of practice can be broader and extends to many aspects of SRHR [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. International organisations (e.g. WHO, United Nations Population Fund and the International Confederation of Midwives) support an expanded approach to midwifery roles to include provision of a range of SRHR services (e.g. health counselling and education, prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission, prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections, and provision of safe abortion where legal) [ 4 , 14 ].

Arguably one of the most crucial components of a health system is its health workforce, as highlighted by WHO’s framework of ‘building blocks’ to support health systems strengthening (service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, access to essential medicines, financing and governance) [ 15 ]. While midwifery is recognised as key to SRHR, there is a global shortage of the midwifery workforce [ 2 , 4 ]. Midwives who are educated and regulated according to international standards can provide 87% of a population’s essential SRHR, yet only 36% of the midwifery workforce is made up of such fully trained midwives, with a range of other health workers also delivering midwifery services [ 4 ]. The latter has been made possible by the range of roles that non-midwife health workers play in providing midwifery services [ 4 , 16 ].

The lack of understanding of the roles of midwifery in health systems has led to significant disparities within and across countries. A better understanding of the roles of midwives within the health system is desirable as they are a key component in the delivery of safe and effective SRHR and could possibly improve the cost-effectiveness of the delivery of these services [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. There is growing recognition that, to strengthen health systems, decisions must be based on the best available research evidence [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Using the available research evidence to understand the roles of midwives across health systems, as well as the political and health system drivers, will yield important insights with the aim of adding to the evidence base that policy-makers can draw from.

The present study asks — across health systems, what are the factors that influence the roles of midwives within the health system? We present a theoretical framework to explain how political and health system factors influence the roles of midwives within the health system. It defines the political system as consisting of three main components, namely institutions, interests and ideas [ 24 ]. ‘Health system arrangements’ are made up of governance, financial and delivery arrangements, and implementation strategies [ 25 ]. Given the lack of theoretical development in the area, this paper, through a critical interpretive synthesis of the available literature, identifies the factors that act as barriers or facilitators to the roles of midwives.

A critical interpretive synthesis was used to develop the theoretical framework, which is an inductive approach to literature analysis. The approach uses conventional systematic review processes while incorporating qualitative inquiries to examine both the empirical and non-empirical literature [ 22 ]. Critical interpretive syntheses are best suited to developing theoretical frameworks that draw on a wide range of relevant sources and are particularly useful when there is a diverse body of literature that is not clearly defined, as is the case with literature related to the roles of midwives in health systems. Conventional systematic reviews have well formulated research questions at the outset, while a critical interpretive synthesis employs a compass question, which is highly iterative and responsive to the findings generated in the review process [ 26 ].

Literature search

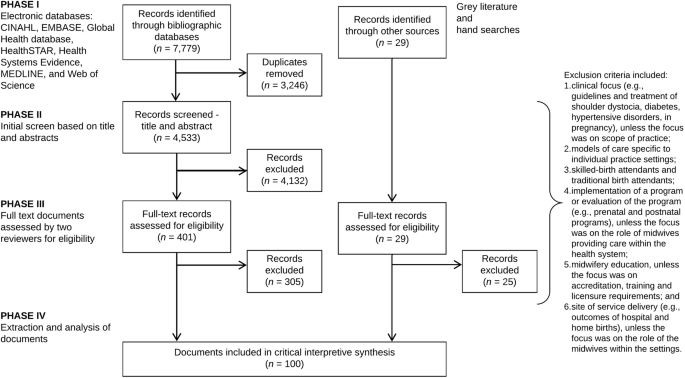

The selection of the literature was carried out in phases (Fig. 1 ). The first phase consisted of a systematic search of electronic bibliographic databases. The searches were executed in consultation with a librarian, who provided guidance on developing keywords (along with Boolean operators) and MeSH (Medical Subject Heading), refining the search strategy, identifying additional databases and executing the searches. We searched the following electronic databases through to 14 May 2020: CINAHL, EMBASE, Global Health database, HealthSTAR, Health Systems Evidence, MEDLINE and Web of Science. The search strategy was first developed in the MEDLINE database, using keywords and MeSH. Similar search strings were used across databases, with minor adjustments made to ensure search optimisation. The searches in MEDLINE included midwi* AND (roles OR scope), midwi* AND delivery of health care (MeSH), midwi* AND patient satisfaction (MeSH), midwi* AND quality of health care (MeSH), and midwi* AND standards (MeSH).

Literature search and study selection flow diagram

The second phase, complementary to the bibliographic database search, was a search of policy and health systems-related SRHR and midwifery organisation websites for relevant documents (e.g. World Health Assembly resolutions and United Nations Population Fund’s State of the World’s Midwifery reports). In addition, hand searches of reference lists from key publications were used to identify further relevant literature (e.g. 2014 Lancet Series on Midwifery). The final step in the literature search process was a purposive search to identify literature to fill the conceptual gaps that emerged.

Article selection

For inclusion, the documents had to relate specifically to trained midwives, with leeway in terms of title (e.g. certified nurse-midwives and certified midwives in the United States). Articles were included, that in addition to providing insight into the compass question, also (1) incorporated a range of perspectives across different countries; (2) integrated different concepts into one document; and (3) included perspectives on the compass question from other disciplines (e.g. geographic information system and other techniques to map the distribution of the midwifery workforce). In order to incorporate a broad range of documents, there were no limits placed on the searches such as regarding language or publication year.

An explicit set of exclusion criteria were developed by the research team to remove the documents that were not relevant to the aims of the study and did not link to the compass question. Exclusion criteria included documents (1) with a clinical focus (e.g. clinical guidelines, pharmacology, diagnostics, devices, surgery and/or treatment of shoulder dystocia, diabetes, hypertensive disorders, in pregnancy), unless the focus was on scope of practice (e.g. midwives working in expanded scopes); (2) focused on models of care that were specific to individual practices or hospitals and included those that were related to health system approaches; (3) relating to unskilled workers providing SRHR (e.g. traditional birth attendants); (4) focused on implementation of a programme or evaluation of the programme (e.g. prenatal and postnatal programmes), unless the focus was on the roles of midwives providing care within the health system; (5) focused on midwifery education, unless the focus was on accreditation, training and licensure requirements; and (6) focused on site of service delivery (e.g. outcomes of hospital and home births), unless the focus was on the roles of midwives within the different practice settings.

Once the series of searches were completed, an Endnote database was created to store and manage the results. All the duplicates were removed from the database and an initial review of the titles and abstracts was performed for each entry by the principal investigator (CAM) and records were classified as ‘possibly include’ or ‘exclude’. In the first stage of screening, records were marked as ‘possibly include’ if they provided insight into the study’s compass question. Full-text copies of the remaining records were retrieved and uploaded to Covidence, an online tool for systematic reviews, for final screening [ 27 ].

The last stage of screening involved two phases and consisted of full-text review by three reviewers (CAM, TD and KMB). Using Covidence, each reviewer examined the records independently to assess inclusion. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved. The reviewers prioritised the inclusion of empirical articles where possible, including empirical qualitative studies, which are the types of articles most likely to address political and health system components.

Data analysis and synthesis

A coding structure was created to guide the data extraction. The areas of expertise of the authors (health systems and policy, clinical practice and political science) informed the selection of frameworks guiding the data extraction. The political system factors were informed through the 3i framework, which is a broad typology that recognises the complex interplay among institutions, interests, and ideas and provides a way of organising the many factors that can influence policy choices [ 24 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]. Institutions are made up of government structures (e.g. federal versus unitary government), policy legacies (e.g. the roles of past policies) and policy networks (e.g. relationships between actors around a policy issue). Interests can include a range of actors who may face (concentrated or diffuse) benefits and costs with particular courses of action, whereas ideas relate to peoples’ beliefs (including those based on research evidence) and values.

‘Health system arrangements’ were informed through an established taxonomy developed by the McMaster Health Forum that includes (1) governance arrangements (e.g. policy authority, organisational authority and professional authority); (2) financial arrangements (e.g. how systems are financed and health professionals remunerated); (3) delivery arrangements (e.g. how care meets consumers’ needs, who provides the care and where it is provided); and (4) implementation strategy (consumer- or provider-targeted strategies) [ 25 ]. The components of the framework for quality maternal and newborn care (practice categories, organisation of care, values, philosophy and health professionals) were incorporated into the health system arrangements coding structure to yield insights specific to midwifery care [ 3 ].

In addition to the frameworks that guided data extraction, further data was collected on publication year, study design and jurisdiction(s) of focus. A data extraction form was developed based on all of the concepts covered in the frameworks as well as the additional descriptive items.

The critical interpretive synthesis was conducted on the high value articles — those that yielded the most insight into the compass question. The reviewers prioritised the inclusion of empirical articles that were conceptually rich or integrated different concepts, filled disciplinary gaps, captured a breadth of perspectives across different countries or applied approaches outside of health. The articles were read by the principal investigator (CAM) and one- or two-page detailed summaries were created for each article. The summaries were coded using the qualitative software NVivo for Mac, which facilitates the organisation and coding of the data [ 31 ]. Coding was informed by the three key frameworks guiding the analysis and outlined above: 3i framework, ‘health system arrangements’ and components of the framework for quality maternal and newborn care.

Three steps were involved in the analysis for the critical interpretive synthesis. First, the summaries of the articles were coded based on the coding structure outlined in the data extraction form. Using a constant comparative method, emerging data were compared to previously collected data to find similarities and differences [ 32 , 33 ]. The approach included observations on the terms and concepts used to describe midwifery within the health system as well as relationships between the concepts. For example, how the role of midwives within the health system is influenced by policy legacies (i.e. institutions), which is related to problems with collaborative/interprofessional environments (i.e. delivery arrangements, skill mix and interprofessional teams). Second, all the data collected under each code was reviewed and more detailed notes of the concepts that emerged were included in the analysis. Lastly, themes were created for the concepts that emerged throughout the analysis.

Completeness of the findings was ensured through ongoing consultation with members of the research team. Central concepts and emerging themes of the study were discussed as a team and applied to current scholarship within the field of health systems and policy.

Search results and article selection

A total of 7779 records were identified through the searches of electronic bibliographic databases. Once duplicates were removed ( n = 3246), the remaining records ( n = 4533) were screened based on title, abstract and the explicit set of exclusion criteria outlined above, leaving 401 potentially relevant records. In addition to the electronic database search, 29 records were purposively sampled for inclusion through grey literature and hand searches. The remaining 401 documents from the electronic database searches and 29 documents from the grey literature and hand searches were assessed by the reviewers (CAM, TD and KMB) for inclusion using the full text. A total of 100 documents were included in the critical interpretive synthesis (Fig. 1 ).

Over three-quarters (79%) of the documents were published after 2010, with no documents published prior to 2000. Of the 100 documents, the majority were primary research ( n = 78), which were mostly qualitative research ( n = 24) and observational studies ( n = 24), followed by the ‘other’ category ( n = 18) (e.g. geographic information systems research), systematic reviews ( n = 15) and mixed methods ( n = 4), while 1 was a randomised control trial. The remaining documents were categorised as non-research ( n = 22), meaning that the approaches taken in the documents were either not systematic or that the methods were not reported transparently. Of the non-research documents, 8 were theoretical papers, 7 were reviews (non-systematic), 4 were ‘other’ (e.g. World Health Assembly resolutions, toolkits, etc.), and the remaining 3 were editorials. Forty-one of the documents focused on LMIC settings, followed by 35 on HIC settings, and 24 focused on both HIC and LMIC settings.

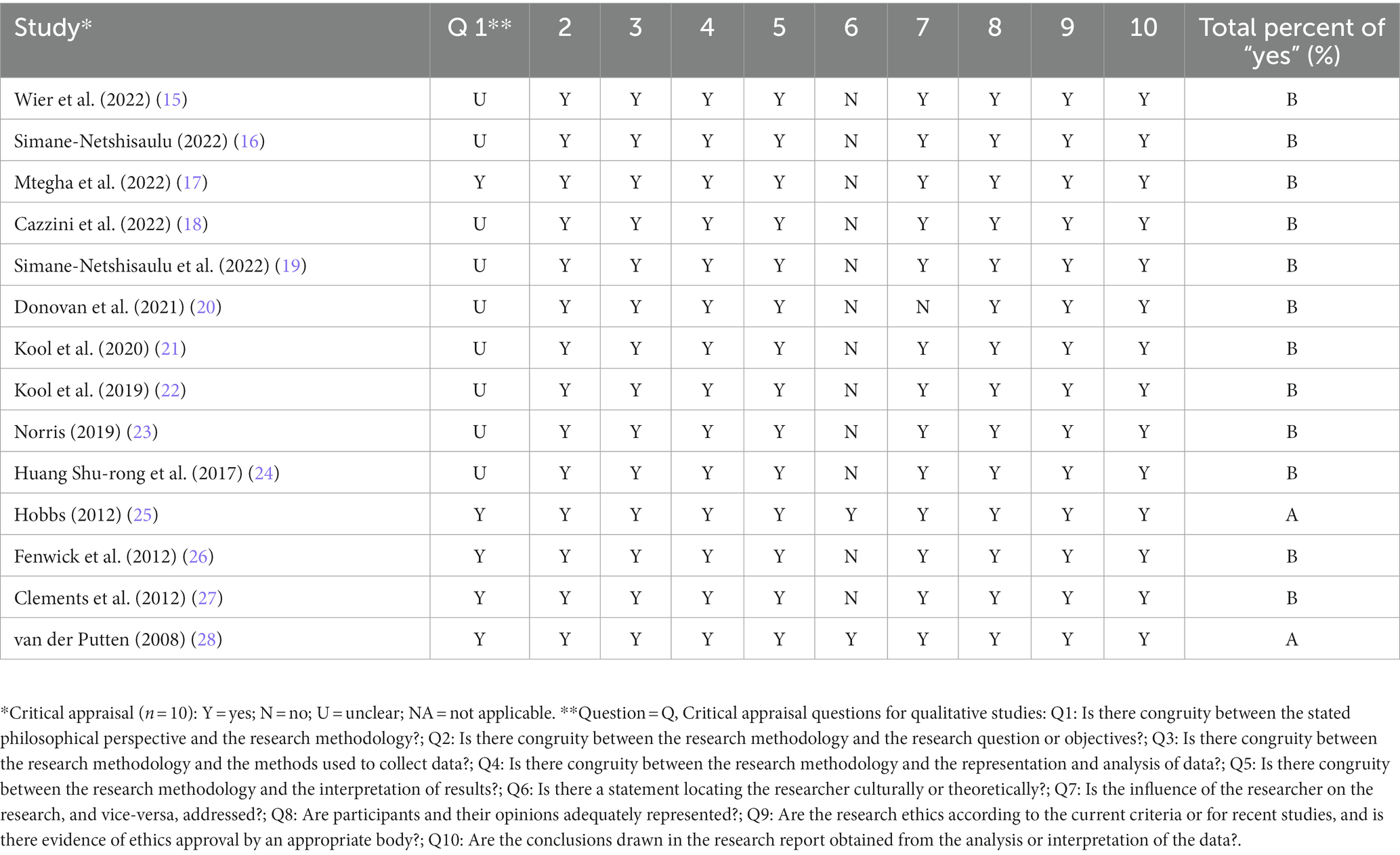

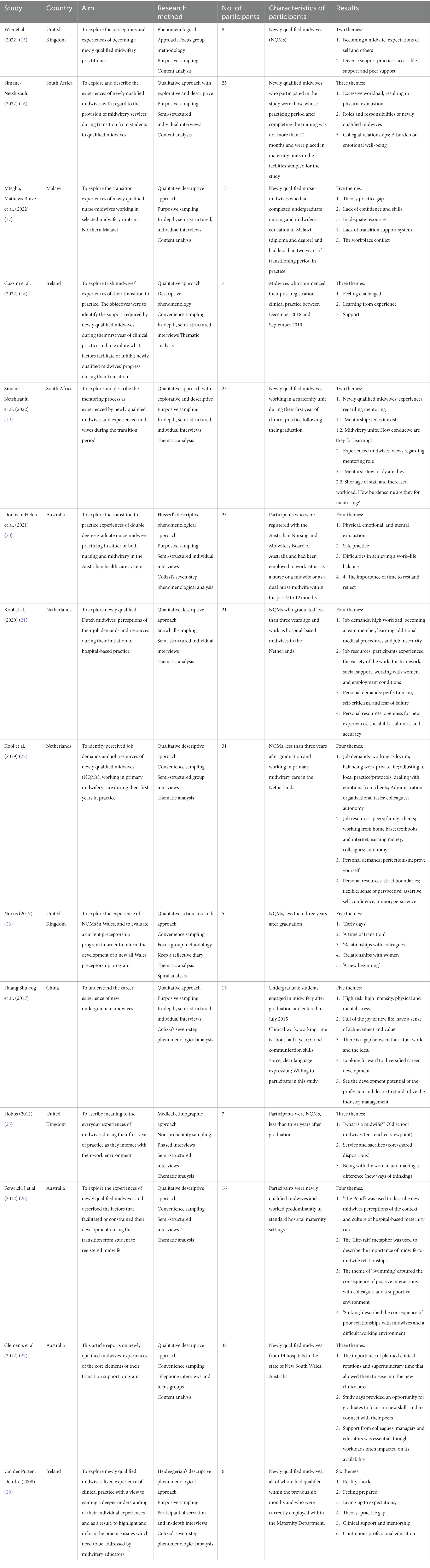

The results of the critical interpretive synthesis focused on the political and health system factors that influenced the roles of midwives within health systems. Table 1 focuses on the political system factors that emerged from the analysis and presents the relevant themes, relationships with other factors, and key examples from the literature of the factors that acted as either barriers or facilitators to the roles of midwives within the health system. Similarly, Table 2 focuses on the health system factors and presents the relevant themes, relationships with other factors, and key examples from the literature on the ‘health system arrangements’ that either acted as barriers or facilitators to the roles of midwives.

Three main findings emerged from the analysis on political system factors. First, within institutions, the effects of past policies regarding the value of midwives created interpretive effects, shaping the way midwifery care is organised in the health system. The legacies of these policies created barriers, which include SRHR policies that reinforced structural gender inequalities as well as, in a medical model, payment systems privileging physician-provided and hospital-based services [ 11 , 13 , 34 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 65 ].

Second, interest groups played an important role in either supporting or opposing the integration of midwifery in the health system. These groups can have direct or indirect influence and policies that provide concentrated benefits and diffuse costs for groups are more likely to move forward [ 24 ]. Interest groups advanced the integration of midwifery in the health system by (1) creating partnerships to improve SRHR [ 45 , 67 ]; (2) promoting regulation and accreditation (e.g. accreditation requirements, setting standards, policies and guidelines) [ 63 , 68 , 69 , 70 ]; (3) capacity-building including midwifery research [ 71 , 72 ]; (4) policy leadership and decision-making [ 43 ]; and (5) lobbying governments and advocacy [ 73 , 74 ]. Strong leadership from midwifery professional associations engaged in policy dialogue and decision-making has helped advance agendas related to universal health coverage and meeting health-related United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [ 8 , 63 , 66 , 71 , 90 ].

Third, the most relevant themes related to ideas that emerged from the analysis pertained to societal values regarding gender (women’s roles within society) as well as the medical model (historical medicalisation of the birth process and associated growth of physician-provided and hospital-based care). We recognise the importance of gender-inclusive language but have use the term ‘women’ in this publication to reflect how gender is referenced in the documents reviewed. Barriers created by societal values included (1) social construction of gender and the status of midwives in a given jurisdiction often reflected the value placed on women within society (i.e. ‘gender penalty’) [ 8 , 11 , 41 , 43 , 46 , 48 , 61 , 71 ]; (2) some cultures and beliefs did not allow women to receive care from men, yet there were few health professionals who were women due to lack of educational opportunities and societal values that restrict women from participating in the paid labour force [ 45 ]; and (3) health system priorities and shifting societal values favoured the medical model [ 41 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 75 , 78 , 99 , 100 , 101 ]. Examples of facilitators included Nordic health systems that value non-medical models and women-dominated professional groups [ 37 ], which respect the right to informed choice [ 86 ].

Within health system factors, the main themes that emerged from the literature are presented according to ‘health system arrangements’. First, within governance arrangements, regulation and accreditation mechanisms to support midwifery education programmes and institutional capacities were central to how midwives are integrated into health systems [ 63 , 70 , 93 , 107 ]. The lack of legislation to support regulatory activities [ 34 , 43 , 48 , 58 , 71 , 82 , 87 , 93 , 94 ] limited recognition and scope [ 38 , 87 ] and the ability for midwives to practice as an autonomous profession [ 80 ]. Globally, there was a general lack of knowledge regarding the International Confederation of Midwives’ Global Standards for Midwifery Education, which was a barrier to the provision of quality midwifery education [ 53 , 66 , 87 , 107 , 108 ]. Within financial arrangements, the literature focused primarily on how systems are financed, on the inclusion of midwifery services within financing systems and on the remuneration of midwives that is reflective of scope of practice [ 1 , 2 , 6 , 10 , 13 , 35 , 38 , 39 , 43 , 50 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 61 , 69 , 73 , 74 , 76 , 80 , 84 , 95 , 101 , 104 , 109 , 115 ]. Lastly, the main themes relating to delivery arrangements focused on (1) accessing midwifery care ranging from availability and timely access to workforce supply, distribution and retention; (2) by whom care is provided (e.g. task-sharing and interprofessional teams); and (3) where care is provided (e.g. hospital-based, integration of services and continuity of care) [ 3 , 4 , 6 , 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 48 , 50 , 51 , 54 , 55 , 58 , 59 , 61 , 62 , 69 , 73 , 74 , 76 , 77 , 79 , 86 , 94 , 96 , 97 , 99 , 100 , 104 , 105 , 110 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 120 , 121 , 122 ].

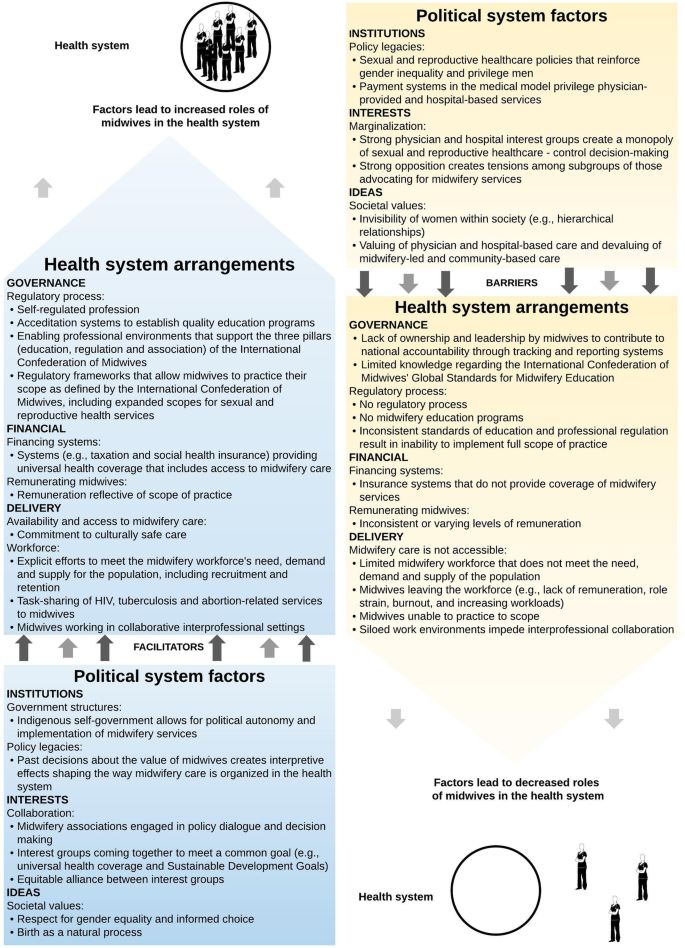

Theoretical framework

Figure 2 brings together the main findings from the critical interpretive synthesis and presents a theoretical framework, which can be thought of as a heuristic that can be used to map the key elements that influence midwives’ roles in a particular political and health system. The factors presented in the framework are not weighted but rather present the range of variables influencing the level of integration of the profession. The cumulative effects of the barriers presented on the right-hand side of the framework lead to health systems where the profession is disempowered and midwives exist on the margins with very limited capacity. Some of the variables and examples presented in the framework have context specificity to reflect findings from the critical interpretive synthesis (e.g. self-regulated profession, Indigenous self-government, Nordic maternity care systems, and payment systems privileging physician-provided and hospital-based services in some contexts).

Theoretical framework of the political and health system factors that influence the roles of midwives within the health system

Principal findings

Similar to the concept of WHO’s health system ‘building blocks’, the political system factors presented in the theoretical framework form the bottom building block or the foundation for the ‘health system arrangements’, acting as either a barrier or facilitator. For example, favourable institutional factors (e.g. policy legacies that value midwifery as a profession), interests (e.g. collaborative interest groups coming together to reach a common goal) and ideas (e.g. societal values centring on gender equality and birth as a natural process) act as enablers to ‘health system arrangements’ that build on each other to support the integration of midwifery. Together, supportive political and health system factors lead to health systems where midwives practice to scope (i.e. trained, licensed and regulated according to international standards, working in collaborative/interprofessional settings with an established workforce). On the other hand, health systems that have many political and health system challenges will in turn have a limited midwifery workforce where midwives lack an institutional voice and representation in SRHR decision-making. Significant barriers limit the options available to the midwifery workforce and is most often reflected in siloed work settings with midwives working in the periphery of the health system.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The main strength of the study is the use of a critical interpretive synthesis. This is a relatively new systematic review methodology, which combines a rigorous systematic review of electronic bibliographic databases with iterative and purposive sampling of the literature to fill conceptual gaps. The approach incorporated a range of documents (empirical and non-empirical), which broadened the scope of the literature used to inform the theoretical framework.

The main limitation of the critical interpretive synthesis was that the search strategy may not have fully covered the diverse terminology used to refer to midwifery. However, the principal investigator (CAM) consulted with a librarian and team members to ensure that the search strategy was as inclusive as possible, which is also reflected by the high proportion of articles that were later excluded during the screening process. Meanwhile, the majority of articles retrieved from the searches were published after 2000, which could be related to the release of the Millennium Development Goals and subsequent Sustainable Development Goals, and the wider attention given to SRHR on global agendas.

Implications for policy and practice

Any changes to the roles of midwifery in health systems needs to take into account the political system where decisions about their integration will be made as well as the nature of the health system in which they are being integrated. The theoretical framework is a tool that helps to inform such changes by identifying the drivers of midwives’ roles that facilitate or constrain such integration. The study results have implications for policy-makers as, firstly, the theoretical framework can be used to conduct an assessment of the factors in order to strengthen the profession by identifying the facilitators that can be leveraged as well as the barriers that can be addressed to support change. For example, Sweden has favourable political system conditions (e.g. policy legacies of professionalisation of midwives dating back to the eighteenth century and an equitable alliance between midwifery and physician groups), which is reflected in the health system arrangements where midwives are the primary health professionals for low-risk pregnant people. In contrast, the United States has policy legacies of payment systems valuing physician-provided and hospital-based care, strong physician and hospital interest groups have created a monopoly over sexual and reproductive health services, and existing tensions within the profession between nurse midwives and midwives.

Moving forward, an implication for practice is that changes to further enhance the role of midwives would require different types of policy levers. In looking at growing midwifery in LMICs, governments can use the tool to understand how to best influence the integration of the profession. This information will provide valuable experience and understanding of the contextual factors so that governments can best leverage their position when working with bilateral and multilateral funders to improve SRHR. Conversely, in the example of the United States, the framework presented helps to explain why midwives play such a small role in sexual and reproductive health service delivery in the United States. The tool highlights that funding and regulatory levers would need to be pulled; yet, strong policy legacies and entrenched interests present significant barriers. Change would require spending political capital to modify existing structures within the health system.

While research evidence on the role of midwives in the provision of high-quality SRHR has increased and the 2014 Lancet Series on Midwifery was key to raising the profile of midwifery research, significant gaps in the literature persist. Structural gender inequalities are reflected in the low status of midwifery in some contexts, which leads to poor political and health systems supports to invest in quality midwifery care [ 43 ]. Our findings show that the research evidence related to the roles of midwives within health systems is relatively saturated in terms of delivery arrangements yet surprisingly little is known about governance and financial arrangements and about implementation strategies, which are key to effectively integrating midwifery and pushing the field forward in meaningful ways.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and summarised in Tables 1 and 2 .

Abbreviations

High-income countries

Low- and middle-income countries

- Sexual and reproductive health and rights

ten Hoope-Bender P, de Bernis L, Campbell J, Downe S, Fauveau V, Fogstad H, et al. Improvement of maternal and newborn health through midwifery. Lancet. 2014;384(9949):1226–35.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Homer CS, Friberg IK, Dias MA, ten Hoope-Bender P, Sandall J, Speciale AM, et al. The projected effect of scaling up midwifery. Lancet. 2014;384(9948):1146–57.

Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, Campbell J, Channon AA, Cheung NF, et al. Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet. 2014;384(9948):1129–45.

UNFPA. The State of the World’s Midwifery 2014. Geneva: United Nations Population Fund; 2014.

Google Scholar

Hutton EK, Cappelletti A, Reitsma AH, Simioni J, Horne J, McGregor C, et al. Outcomes associated with planned place of birth among women with low-risk pregnancies. CMAJ. 2016;188(5):E80–90.

Malott AM, Davis BM, McDonald H, Hutton E. Midwifery care in eight industrialized countries: how does Canadian midwifery compare? J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31(10):974–9.

Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:CD004667.

Renfrew MJ, Ateva E, Dennis-Antwi JA, Davis D, Dixon L, Johnson P, et al. Midwifery is a vital solution-what is holding back global progress? Birth. 2019;46(3):396–9.

Malott AM, Kaufman K, Thorpe J, Saxell L, Becker G, Paulette L, et al. Models of organization of maternity care by midwives in Canada: a descriptive review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34(10):961–70.

Bartlett L, Weissman E, Gubin R, Patton-Molitors R, Friberg IK. The impact and cost of scaling up midwifery and obstetrics in 58 low- and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98550.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Fauveau V, Sherratt DR, de Bernis L. Human resources for maternal health: multi-purpose or specialists? Hum Resour Health. 2008;6:21.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Holcombe SJ, Berhe A, Cherie A. Personal beliefs and professional responsibilities: Ethiopian midwives’ attitudes toward providing abortion services after legal reform. Stud Fam Plan. 2015;46(1):73–95.

Article Google Scholar

Liljestrand J, Sambath MR. Socio-economic improvements and health system strengthening of maternity care are contributing to maternal mortality reduction in Cambodia. Reprod Health Matters. 2012;20(39):62–72.

ICM. International definition of the midwife. The Hague: International Confederation of Midwives; 2017. https://www.internationalmidwives.org/assets/files/definitions-files/2018/06/eng-definition_of_the_midwife-2017.pdf .

World Health Organization. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Geneva: WHO; 2020. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/WHO_MBHSS_2010_full_web.pdf .

Lopes SC, Titulaer P, Bokosi M, Homer CS, ten Hoope-Bender P. The involvement of midwives associations in policy and planning about the midwifery workforce: a global survey. Midwifery. 2015;31(11):1096–103.

Janssen PA, Mitton C, Aghajanian J. Costs of planned home vs. hospital birth in British Columbia attended by registered midwives and physicians. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133524.

Reinharz D, Blais R, Fraser WD, Contandriopoulos A-P. Cost-effectiveness of midwifery services vs. medical services in Quebec. Can J Public Health. 2000;91(1):I12.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Schroeder E, Petrou S, Patel N, Hollowell J, Puddicombe D, Redshaw M, et al. Cost effectiveness of alternative planned places of birth in woman at low risk of complications: evidence from the Birthplace in England national prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e2292.

Lavis J, Davies H, Oxman A, Denis JL, Golden-Biddle K, Ferlie E. Towards systematic reviews that inform health care management and policy-making. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(Suppl 1):35–48.

Lavis JN, Guindon GE, Cameron D, Boupha B, Dejman M, Osei EJ, et al. Bridging the gaps between research, policy and practice in low- and middle-income countries: a survey of researchers. CMAJ. 2010;182(9):E350–61.

Moat KA, Lavis JN, Abelson J. How contexts and issues influence the use of policy-relevant research syntheses: a critical interpretive synthesis. Milbank Q. 2013;91(3):604–48.

Wilson MG, Moat KA, Lavis JN. The global stock of research evidence relevant to health systems policymaking. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:32.

Lazar H, Lavis JN, Forest P-G, Church J. Paradigm freeze: why it is so hard to reform health care in Canada. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press; 2013.

Lavis JN, Wilson MG, Moat KA, Hammill AC, Boyko JA, Grimshaw JM, et al. Developing and refining the methods for a ‘one-stop shop’for research evidence about health systems. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:10.

Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur A, Harvey J, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:35.

Covidence. About us Australia: Covidence; 2017. https://www.covidence.org/about-us .

Hall PA. The role of interests, institutions, and ideas in the comparative political economy of the industrialized nations. In: Comparative politics: rationality, culture, and structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. p. 174–207.

Oliver MJ, Pemberton H. Learning and change in 20th-century British economic policy. Governance. 2004;17(3):415–41.

Walsh JI. When do ideas matter? Explaining the successes and failures of Thatcherite ideas. Comp Political Stud. 2000;33(4):483–516.

QSR International. NVivo for Mac Australia: QSR International; 2017. http://www.qsrinternational.com/product/nvivo-mac .

Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. London: Sage; 2014.

Glaser BG, Strauss A. The discovery of ground theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1967.

Van Wagner V, Epoo B, Nastapoka J, Harney E. Reclaiming birth, health, and community: Midwifery in the Inuit villages of Nunavik, Canada. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007;52(4):384–91.

Epoo B, Stonier J, Wagner VV, Harney E. Learning midwifery in Nunavik: community-based education for Inuit midwives. J Indigenous Wellbeing. 2012;10(3):283–99.

Wagner V, Osepchook C, Harney E, Crosbie C, Tulugak M. Remote midwifery in Nunavik, Quebec, Canada: outcomes of perinatal care for the Inuulitsivik Health Centre, 2000-2007. Birth Issue Perinat Care. 2012;39(3):230–7.

Wrede S, Benoit C, Einarsdottir T. Equity and dignity in maternity care provision in Canada, Finland and Iceland. Can J Public Health. 2008;99:S16–21.

DeMaria LM, Campero L, Vidler M, Walker D. Non-physician providers of obstetric care in Mexico: perspectives of physicians, obstetric nurses and professional midwives. Hum Resour Health. 2012;10:6.

Van Lerberghe W, Matthews Z, Achadi E, Ancona C, Campbell J, Channon A, et al. Country experience with strengthening of health systems and deployment of midwives in countries with high maternal mortality. Lancet. 2014;384(9949):1215–25.

Bogren M, Erlandsson K. Opportunities, challenges and strategies when building a midwifery profession. Findings from a qualitative study in Bangladesh and Nepal. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2018;16:45–9.

Temmar F, Vissandjee B, Hatem M, Apale A, Kobluk D. Midwives in Morocco: seeking recognition as skilled partners in women-centred maternity care. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14(27):83–90.

Betron ML, McClair TL, Currie S, Banerjee J. Expanding the agenda for addressing mistreatment in maternity care: a mapping review and gender analysis. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):143.

Filby A, McConville F, Portela A. What prevents quality midwifery care? A systematic mapping of barriers in low and middle income countries from the provider perspective. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0153391.

Witter S, Namakula J, Wurie H, Chirwa Y, So S, Vong S, et al. The gendered health workforce: mixed methods analysis from four fragile and post-conflict contexts. Health Policy Plann. 2017;32(Suppl. 5):v52–62.

Turkmani S, Currie S, Mungia J, Assefi N, Rahmanzai AJ, Azfar P, et al. ‘Midwives are the backbone of our health system’: lessons from Afghanistan to guide expansion of midwifery in challenging settings. Midwifery. 2013;29(10):1166–72.

Beek K, McFadden A, Dawson A. The role and scope of practice of midwives in humanitarian settings: a systematic review and content analysis. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17:5.

Devane D, Murphy-Lawless J, Begley CM. Childbirth policies and practices in Ireland and the journey towards midwifery-led care. Midwifery. 2007;23(1):92–101.

Brodie P. Addressing the barriers to midwifery--Australian midwives speaking out. Aust J Midwifery. 2002;15(3):5–14.

Christiaens W, Nieuwenhuijze MJ, de Vries R. Trends in the medicalisation of childbirth in Flanders and the Netherlands. Midwifery. 2013;29(1):e1–8.

Goodman S. Piercing the veil: the marginalization of midwives in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(3):610–21.

Kennedy HP, Rousseau AL, Low LK. An exploratory metasynthesis of midwifery practice in the United States. Midwifery. 2003;19(3):203–14.

Mattison CA, Lavis JN, Hutton EK, Dion ML, Wilson MG. Understanding the conditions that influence the roles of midwives in Ontario, Canada’s health system: an embedded single-case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):197.

Barger MK, Hackley B, Bharj KK, Luyben A, Thompson JB. Knowledge and use of the ICM global standards for midwifery education. Midwifery. 2019;79:102534.

James S, O'Brien B, Bourret K, Kango N, Gafvels K, Paradis-Pastori J. Meeting the needs of Nunavut families: a community-based midwifery education program. Circumpolar special issue: human health at the ends of the earth. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(2):1355.

PubMed Google Scholar

Kildea S, Kruske S, Barclay L, Tracy S. ‘Closing the gap’: how maternity services can contribute to reducing poor maternal infant health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(3):1383.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kreiner M. Delivering diversity: newly regulated midwifery returns to Manitoba, Canada, one community at a time. J Midwifery Women Health. 2009;54(1):e1–e10.

National Aboriginal Health Organization. Midwifery and aboriginal midwifery in Canada. Ottawa: National Aboriginal Health Organization; 2004.

Skye AD. Aboriginal midwifery: a model for change. Int J Indigenous Health. 2010;6(1):28–37.

Mavalankar D, Raman PS, Vora K. Midwives of India: missing in action. Midwifery. 2011;27(5):700–6.

Munabi-Babigumira S, Nabudere H, Asiimwe D, Fretheim A, Sandberg K. Implementing the skilled birth attendance strategy in Uganda: a policy analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:655.

Day-Stirk F, Fauveau V. The state of the world’s midwifery: making the invisible visible. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2012;119:S39–41.

Hogberg U. The decline in maternal mortality in Sweden: the role of community midwifery. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(8):1312–20.

ten Hoope-Bender P, Lopes STC, Nove A, Michel-Schuldt M, Moyo NT, Bokosi M, et al. Midwifery 2030: a woman’s pathway to health. What does this mean? Midwifery. 2016;32:1–6.

Shakibazadeh E, Namadian M, Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Rashidian A, Pileggi VN, et al. Respectful care during childbirth in health facilities globally: a qualitative evidence synthesis. BJOG. 2018;125(8):932–42.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Oliver K, Parolin Z. Assessing the policy and practice impact of an international policy initiative: the state of the world’s midwifery 2014. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):499.

World Health Organization. Nursing and Midwifery in the history of the World Health Organization 1948–2017. Geneva: WHO; 2017.

Spies LA, Garner SL, Faucher MA, Hastings-Tolsma M, Riley C, Millenbruch J, et al. A model for upscaling global partnerships and building nurse and midwifery capacity. Int Nurs Rev. 2017;64(3):331–44.

Chamberlain J, McDonagh R, Lalonde A, Arulkumaran S. The role of professional associations in reducing maternal mortality worldwide. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003;83(1):94–102.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Haththotuwa R, Senanayake L, Senarath U, Attygalle D. Models of care that have reduced maternal mortality and morbidity in Sri Lanka. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;119(Suppl 1):S45–9.

de Bernis L. Implementation of midwifery school accreditation mechanisms in Ivory Coast, Mali and Chad. Sante Publique. 2018;30:57–63.

Homer CSE, Castro Lopes S, Nove A, Michel-Schuldt M, McConville F, Moyo NT, et al. Barriers to and strategies for addressing the availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of the sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn and adolescent health workforce: addressing the post-2015 agenda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):55.

Nabirye RC, Kinengyere AA, Edwards G. Nursing and midwifery research output in Africa: a review of the literature. Int J Childbirth. 2018;8(4):236–41.

Koblinsky M, Matthews Z, Hussein J, Mavalankar D, Mridha MK, Anwar I, et al. Going to scale with professional skilled care... third in a series of five articles. Lancet. 2006;368(9544):1377–86.

World Health Organization. Munich declaration – nurses and midwives: a force for health. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2000;16(4):207–8.

Vedam S, Stoll K, MacDorman M, Declercq E, Cramer R, Cheyney M, et al. Mapping integration of midwives across the United States: impact on access, equity, and outcomes. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192523.

Downe S, Finlayson K, Fleming A. Creating a collaborative culture in maternity care. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55(3):250–4.

College of Midwives of Ontario. The Midwifery Scope of Practice: The College of Midwives of Ontario Submission to the Health Professions Regulatory Advisory Council. Toronto: College of Midwives of Ontario; 2008.

Hoope-Bender P, Renfrew MJ. Midwifery – a vital path to quality maternal and newborn care: the story of the Lancet series on midwifery. Midwifery. 2014;30(11):1105–6.

Scholmerich VL, Posthumus AG, Ghorashi H, Waelput AJ, Groenewegen P, Denktas S. Improving interprofessional coordination in Dutch midwifery and obstetrics: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:145.

Peterson C. Midwifery and the crowning of health care reform. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55(1):5–8.

Bogren MU, Berg M, Edgren L, Ev T, Wigert H. Shaping the midwifery profession in Nepal - uncovering actors’ connections using a Complex Adaptive Systems framework. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2016;10:48–55.

Bogren MU, van Teijlingen E, Berg M. Where midwives are not yet recognised: a feasibility study of professional midwives in Nepal. Midwifery. 2013;29(10):1103–9.

Klopper HC, Madigan E, Vlasich C, Albien A, Ricciardi R, Catrambone C, et al. Advancement of global health: recommendations from the Global Advisory Panel on the Future of Nursing & Midwifery (GAPFON (R)). J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(2):741–8.

Binfa L, Pantoja L, Ortiz J, Gurovich M, Cavada G. Assessment of the implementation of the model of integrated and humanised midwifery health services in Santiago, Chile. Midwifery. 2013;29(10):1151–7.

Bergevin Y, Fauveau V, McKinnon B. Towards ending preventable maternal deaths by 2035. Semin Reprod Med. 2015;33(1):23–9.

Donnay F. Maternal survival in developing countries: what has been done, what can be achieved in the next decade. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2000;70(1):89–97.

Castro Lopes S, Nove A, Hoope-Bender P, Bernis LD, Bokosi M, Moyo NT, et al. A descriptive analysis of midwifery education, regulation and association in 73 countries: the baseline for a post-2015 pathway. Hum Resour Health. 2016;14:37.

Bvumbwe T, Mtshali N. Nursing education challenges and solutions in Sub Saharan Africa: an integrative review. BMC Nurs. 2018;17:3.

Yalahow A, Hassan M, Foster AM. Training reproductive health professionals in a post-conflict environment: exploring medical, nursing, and midwifery education in Mogadishu, Somaila. Reprod Health Matters. 2017;25(51):114–23.

Ajuebor O, McCarthy C, Li Y, Al-Blooshi SM, Makhanya N, Cometto G. Are the global strategic directions for strengthening nursing and midwifery 2016–2020 being implemented in countries? Findings from a cross-sectional analysis. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17:54.

Nagle C, McDonald S, Morrow J, Kruger G, Cramer R, Couch S, et al. Informing the development midwifery standards for practice: a literature review for policy development. Midwifery. 2019;76:8–20.

Sandwell R, Bonser D, Hebert E, Kilroy K, Leshabari S, Mwanga F, et al. Stronger together: midwifery twinning between Tanzania and Canada. Glob Health. 2018;14(1):123.

West F, Homer C, Dawson A. Building midwifery educator capacity in teaching in low and lower-middle income countries. A review of the literature. Midwifery. 2016;33:12–23.

Colvin CJ, de Heer J, Winterton L, Mellenkamp M, Glenton C, Noyes J, et al. A systematic review of qualitative evidence on barriers and facilitators to the implementation of task-shifting in midwifery services. Midwifery. 2013;29(10):1211–21.

Sidebotham M, Fenwick J, Rath S, Gamble J. Midwives’ perceptions of their role within the context of maternity service reform: an appreciative inquiry. Women Birth. 2015;28(2):112–20.

McCarthy CF, Voss J, Verani AR, Vidot P, Salmon ME, Riley PL. Nursing and midwifery regulation and HIV scale-up: Establishing a baseline in East, Central and Southern Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18051.

Jenkins GL. Burning bridges: policy, practice, and the destruction of midwifery in rural Costa Rica. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(9):1893–909.

Fullerton J, Severino R, Brogan K, Thompson J. The International Confederation of Midwives’ study of essential competencies of midwifery practice. Midwifery. 2003;19(3):174–90.

Amelink-Verburg MP, Buitendijk SE. Pregnancy and labour in the Dutch maternity care system: what is normal? The role division between midwives and obstetricians. J Midwifery Women Health. 2010;55(3):216–25.

Homer CSE, Passant L, Brodie PM, Kildea S, Leap N, Pincombe J, et al. The role of the midwife in Australia: views of women and midwives. Midwifery. 2009;25(6):673–81.

Spendlove Z. Risk and boundary work in contemporary maternity care: tensions and consequences. Health Risk Soc. 2018;20(1–2):63–80.

Summer A, Walker D, Guendelman S. A review of the forces influencing maternal health policies in post-war Guatemala. World Med Health Policy. 2019;11(1):59–82.

Summer A, Walker D. Recommendations for sustainable midwifery in Guatemala. World Med Health Policy. 2018;10(4):356–80.

Kopacz L, Pawelec M, Pietras J, Karmowski A, Palczynski B, Karmowski M, et al. The Polish way to better midwifery or commercialization of maternity services? Adv Clin Exp Med. 2011;20(4):513–20.

Biro MA. What has public health got to do with midwifery? Midwives’ role in securing better health outcomes for mothers and babies. Women Birth. 2011;24(1):17–23.

Homer CSE, Passant L, Kildea S, Pincombe J, Thorogood C, Leap N, et al. The development of national competency standards for the midwife in Australia. Midwifery. 2007;23(4):350–60.

Luyben A, Barger M, Avery M, Bharj KK, O'Connell R, Fleming V, et al. Exploring global recognition of quality midwifery education: vision or fiction? Women Birth. 2017;30(3):184–92.

Zhu X, Yao JS, Lu JY, Pang RY, Lu H. Midwifery policy in contemporary and modern China: from the past to the future. Midwifery. 2018;66:97–102.

McNeill J, Lynn F, Alderdice F. Public health interventions in midwifery: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:955.

Mainey L, O'Mullan C, Reid-Searl K, Taylor A, Baird K. The role of nurses and midwives in the provision of abortion care: a scoping review. J Clinical Nurs. 2020;29(9–10):1513–26.

Fullerton J, Butler MM, Aman C, Reid T, Dowler M. Abortion-related care and the role of the midwife: a global perspective. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:751–62.

Massot E, Epaulard O. Midwives’ perceptions of vaccines and their role as vaccinators: the emergence of a new immunization corps. Vaccine. 2018;36(34):5204–9.

Van Hoover C, Holt L. Midwifing the end of life: expanding the scope of modern midwifery practice to reclaim palliative care. J Midwifery Women Health. 2016;61(3):306–14.

Alayande A, Mamman-Daura F, Adedeji O, Muhammad AZ. Midwives as drivers of reproductive health commodity security in Kaduna State, Nigeria. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21(3):207–12.

Ir P, Korachais C, Chheng K, Horemans D, Van Damme W, Meessen B. Boosting facility deliveries with results-based financing: a mixed-methods evaluation of the government midwifery incentive scheme in Cambodia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:170.

King TL, Laros RK, Parer JT. Interprofessional collaborative practice in obstetrics and midwifery. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2012;39(3):411–22.

Arias MG, Nove A, Michel-Schuldt M, Bernis L. Current and future availability of and need for human resources for sexual, reproductive, maternal and newborn health in 41 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):69.

Suleiman-Martos N, Albendin-Garcia L, Gomez-Urquiza JL, Vargas-Roman K, Ramirez-Baena L, Ortega-Campos E, et al. Prevalence and predictors of burnout in midwives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(2):641.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Nove A. The quality of midwifery education in six French-speaking sub-Saharan African countries. Sante Publique. 2018;30:45–55.

Renner RM, Brahmi D, Kapp N. Who can provide effective and safe termination of pregnancy care? A systematic review. BJOG. 2013;120(1):23–31.

Miyake S, Speakman EM, Currie S, Howard N. Community midwifery initiatives in fragile and conflict-affected countries: a scoping review of approaches from recruitment to retention. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(1):21–33.

Sami S, Amsalu R, Dimiti A, Jackson D, Kenyi S, Meyers J, et al. Understanding health systems to improve community and facility level newborn care among displaced populations in South Sudan: a mixed methods case study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):325.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kirsty Bourret and Tomasso D’Ovidio for their assistance with assessing documents for eligibility and inclusion in the review.

There are no sources of funding to declare for this research.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, McMaster Midwifery Research Centre, 1280 Main St. West, HSC-4H26, Hamilton, ON, L8S 4K1, Canada

Cristina A. Mattison & Eileen K. Hutton

McMaster Health Forum, 1280 Main St West, MML-417, Hamilton, ON, L8S 4L6, Canada

John N. Lavis & Michael G. Wilson

Department of Political Science, McMaster University, 1280 Main St. West, KTH-533, Hamilton, ON, L8S 4M4, Canada

Michelle L. Dion

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

CAM conceived the study design with her supervisor, JNL, and was responsible for all data collection and analysis. JNL, EKH, MGW and MLD provided content expertise (health systems and health policy, clinical practice and political science) to inform the selection of frameworks guiding the data extraction. All authors contributed to the development of the conceptual framework and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cristina A. Mattison .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mattison, C.A., Lavis, J.N., Wilson, M.G. et al. A critical interpretive synthesis of the roles of midwives in health systems. Health Res Policy Sys 18 , 77 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00590-0

Download citation

Received : 27 January 2020

Accepted : 14 June 2020

Published : 08 July 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00590-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Political systems

- Health systems

- Critical interpretive synthesis

Health Research Policy and Systems

ISSN: 1478-4505

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Strengthening Midwifery Research

- First Online: 06 January 2021

Cite this chapter

- Joy Kemp 4 ,

- Gaynor D. Maclean 5 &

- Nester Moyo 6

747 Accesses

1 Citations

Considering research as an integral part of midwifery education and an indispensable tool in evidence-based practice provides the starting point in this chapter. Network theory is considered prior to exploring midwifery research networks and other initiatives in this context. Examples of initiatives to promote research through universities and professional associations are provided. Priority areas for midwifery research are explored, and the importance of high-quality research is considered in the context of providing evidence upon which safe practice can be based. The chapter concludes by considering the place of midwifery research in the wider context of health care and its significance in the development of the profession of midwifery.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Additional Resources for Reflection and Further Study

Visit the website of the Lugina Africa Midwives Research Network (LAMRN) at: http://lamrn.org/ Examine the ambitions and achievements of this network and consider how such a network may be replicated in other regions.

Explore the website of the Journal of Asian Midwifery (JAM) at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/jam/ Reflect on the aims and scope of the journal and consider its role in promoting midwifery research and enhancing evidence-based practice.

Readers may wish to compare and contrast the activities of the two structures described above and consider what strengths could be gleaned from both in order to establish a wider network for undertaking and disseminating midwifery research.

Google Scholar

World Health Organization (2019) Setting the research agenda: read about the current and ongoing research priorities in maternal, newborn and adolescent health at: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/research/en/ . Recent research publications are regularly updated here too.

Soltani H, Low LK, Duxbury A et al (2016) Global midwifery research priorities: an international survey. Int J Childbirth 6(1):5–18 Consider these in the context of your own practice and experience

Article Google Scholar

In the context of global research priorities, explore what the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Group are doing to address stillbirth and perinatal mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa: https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/stillbirth-prevention-africa/ . Accessed 23 Oct 2019.

Abuya T et al (2015) Exploring the prevalence of disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. PLoS One 10(4):e0123606. Accessed 3 Oct 2019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123606

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

African Journal of Midwifery (2017) African J Midwifery & Women’s Health. MA Healthcare. http://www.magonlinelibrary.com/toc/ajmw/current . Accessed 12 Mar 2020

American College of Nurse-Midwives (2019) Midwifery Research Interest Groups. American College of Nurse Midwives. http://www.midwife.org/Midwifery-Research-Interest-Groups . Accessed 15 Oct 2019

Australian College of Midwives (2019) Research and innovation: Australian College of Midwives: https://www.midwives.org.au/interest-group/research-and-innovation . Accessed 15 Oct 2019

Azmoud E, Aradmehr M, Dehghani F (2018) Midwives’ attitude and barriers of evidence based practice in maternity care. Malay J Med Sci 25(3):120–128. https://doi.org/10.21315/mjms2018.25.3.12

Barnes S (2019) Empowered midwives could save lives. New Security Beat, Wilson Center, Environmental Change and Security. https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2019/08/empowered-midwives-save-lives/ . Accessed 16 Oct 2019

Begeley C, Mccarron M, Huntley-Moore S et al (2014) Successful research capacity building in academic nursing and midwifery in Ireland: an exemplar. Nurse Educ Today 34(5):754–760

Bogdan-Lovis E, Sousa A (2006) The contextual influence of professional culture: certified nurse-midwives’ knowledge of and reliance on evidence-based practice. Soc Sci Med 62(11):2681–2693

Bogren M, Doraiswamy S, Erlandsson K (2017) Building a new generation of midwifery faculty members in Bangladesh. J Asian Midwives 4(2):52–58

Bonilla H, Ortiz-Llorens BM et al (2018) Implementation of a programme to develop research projects in a school of midwifery in Santiago. Chile Midwifery 64:60–62

Bowser D, Hill K (2010) Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth: report of a landscape analysis. USAID-TRAction Project, University Research Corporation, LLC, and Harvard School of Public Health, Bethesda, MD. http://www.tractionproject.org/sites/default/files/Respectful_Care_at_Birth_9-20-101_Final.pdf

Brucker M, Schwarz B (2002) Fact or fiction? International Confederation of Midwives Triennial Conference Proceedings. Austria, Vienna

Burrowes S, Holcombe SJ, Jara D et al (2017) Midwives’ and patients’ perspectives on disrespect and abuse during labor and delivery care in Ethiopia: a qualitative study. BMC Preg Childbirth Open Access 17:263. https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-017-1442-1 . Accessed 8 Oct 2019

Directorate General of Nursing and Midwifery (2017) National Guidelines for Midwives, Directorate General of Nursing and Midwifery, Bangladesh. http://dgnm.gov.bd/cmsfiles/files/SOP%20for%20Midwives.pdf . Accessed 23 Oct 2019

Doctoral Midwifery Research Society (2020) DMRS background and membership. https://www.doctoralmidwiferysociety.org/ . Accessed 3 Jun 2020

Einstein A, Shaw GB (2009) Einstein on cosmic religion: and other opinions and other aphorisms. Dover, New York

European Midwives Associations (2019) EU Research. European Midwives Association. http://www.europeanmidwives.com/eu/eu-research . Accessed 15 Oct 2019

Forss K, Maclean G (2007) Evaluation of the Africa midwives research network. A study commissioned by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. Sida, Stockholm

Forss K, Birungi H, Saasa O (2000) Sector wide approaches: from principles to practice. A study commissioned by the Department of Foreign Affairs, Dublin, Ireland. Final report 13/11/2000 Andante – tools for thinking AB. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/252177958_Sector_wide_approaches_from_principles_to_practice . Accessed 26 Oct 2019

Glacken M, Chaney D (2004) Perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing research findings in the Irish practice setting. J Clin Nurs 13(6):731–740. Accessed 3 Jun 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00941.x

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Goyet S, Sauvegrain P, Schantz C et al (2018) State of midwifery research in France. Midwifery 64(101–109):2018

Granovetter M (1973) The strength of weak ties. Am J Sociol 78:1360–1380

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC et al (1995) Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: IX. A Method for Grading Health Care Recommendations. JAMA 274(22):18001804. Accessed 16 Oct 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03530220066035

Hommelstad J, Ruland CM (2004) Norwegian nurses’ perceived barriers and facilitators to research use. Assoc Perioper Reg Nurs J 79(3):621–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-2092(06)60914-9

Hunter B (2013) Implementing research evidence into practice some reflections on the challenges. Evid Based Midwifery 11(3):76–80

International Confederation of Midwives (2014) Basic and ongoing education for midwives: position statement. strengthening midwifery globally: PS2008_001 V2014. International Confederation of Midwives, The Hague. https://www.internationalmidwives.org/assets/files/statement-files/2019/06/basic-and-ongoing-education-for-midwives-eng-letterhead.pdf . Accessed 15 Oct 2019

International Confederation of Midwives (2018) Research Standing Committee: https://www.internationalmidwives.org/our-work/research/research-standing-committee.html [last accessed 09.11.2020]

International Confederation of Midwives (2019) Research: Midwifery led research. International Confederation of Midwives, The Hague. https://www.internationalmidwives.org/our-work/research/ . Accessed 23 Oct 2019

Iribarren S, Larsen B, Santos F et al (2018) Clinical nursing and midwifery research in Latin American and Caribbean countries: a scoping review. Int J Nurs Pract 24(2):e12623. Accessed 18 Oct 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12623

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kajermo KN, Boström A-M, Thompson DS et al (2010) The BARRIERS scale—the barriers to research utilization scale: a systematic review. Implement Sci 32(5):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-32

Kennedy HP, Cheyney M, Dahlen H et al (2018) Asking different questions: research priorities to improve the quality of care for every woman, every child. Lancet Glob Health. Revised May 2018. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/birt.12361 . Accessed 28 May 2020

Khammarnia M, Haj Mohammadi M, Amani Z et al (2015) Barriers to implementation of evidence-based practice in Zahedan teaching hospitals, Iran, 2014. Nurs Res Pract:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/357140

Kolfenbach M, Birdsall K (2015) (2015) international cooperation: strengthening midwifery in Central Asia. J Asian Midwives 2(2):57–61

Koninklijke Nederlandse Organisatie van Verloskundigen (KNOV) (2013) Midwifery Research Network, Dutch Midwives Association. https://www.knov.nl/vakkennis-en-wetenschap/tekstpagina/117-2/midwifery-research-network/hoofdstuk/45/midwifery-research-network/ . Accessed 15 Oct 2019

Laisser R, Chimwaza A, Omoni G et al (2019) Crisis: an educational game to reduce mortality and morbidity. Afr J Midwifery Women Health 13:1–6. https://doi.org/10.12968/AJMW.2018.0025

Lavender T, Omoni G, Laisser et al (2019) Evaluation of an educational board game to improve use of the partograph in sub-Saharan Africa: a quasi-experimental study. Sex Reprod Healthc (20) 54–59

Lugina African Midwives Research Network (2019) The Lugina Africa Midwives Research Network. http://lamrn.org/ . Accessed 4 Jun 2020

Luyben A, Winjen H, Oblasser C et al (2013) The current state of development of midwifery and midwifery research in four European countries. Midwifery 29(5):417–424. Accessed 1 Jun 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2012.10.008

Maclean GD, Forss K (2010) An evaluation of the Africa midwives research network. Midwifery 26:e1–e8

Maclean G, Laisser R (2020) The use of educational games in midwifery. Afr J Midwifery Women Health 14(91):1–10

Mills J, Yates K, Harrison H et al (2016) Using a community of inquiry framework to teach a nursing and midwifery research subject: an evaluative study. Nurse Educ Today 43:34–39

Munro J, Spiby H (2001) Evidence into practice for midwifery-led care: part 2. Br J Midwifery 9:771–774

Munro J, Spiby H (2010) The nature and use of evidence in midwifery care: evidence-based midwifery. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242188203_1_The_Nature_and_Use_of_Evidence_in_Midwifery_Care . Accessed 28 May 2020

Muoni T (2014) Decision-making, intuition and the midwife: understanding heuristics. BJM 20(1). Published Online: 16 Aug 2013. Accessed 26 Oct 2019. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2012.20.1.52

Nanda G, Switlick K, Lule E (2005) Accelerating progress towards achieving the MDG to improve maternal health: a collection of promising approaches. Health, Nutrition & Population Discussion Paper. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, Washington, DC, p 20433

National Institute of Health Research (2020) Stillbirth prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. The National Institute of Health Research and University of Manchester. https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/stillbirth-prevention-africa/ . Accessed 4 Jun 2020

Ndwiga C, Maingi G, Serwanga J et al (2017) Exploring provider perspectives on respectful maternity care in Kenya: “Work with what you have”. Reprod Health 14:99. Accessed 8 Oct 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0364-8

New Zealand College of Midwives (2019) Research: New Zealand College of Midwives. https://www.midwife.org.nz/midwives/research/ . Accessed 15 Oct 2019

Nohria N, Eccles RG (eds) (1992) Networks and organisations: structure, form and action. Harvard Business School Press, Boston

Olsson A, Adolfsson A (2011) Midwife’s experiences of using intuition as a motivating element in conveying assurance and care. Health 3:453–461. Accessed 26 Oct 2019. https://doi.org/10.4236/health.2011.37075

Perrow C (1986) Complex organisations: a critical essay. Random House, New York

Piore MJ (1990) Fragments of a cognitive theory of technological change and organizational behaviour. In: Nohria N, Eccles RG (eds) Networks and organisations: structure, form and action. Harvard Business School Press, Boston

Porter ME (1990) The competitive advantages of nations. Free Press, New York

Book Google Scholar

Renfrew MJ (1997) The development of evidence-based practice. Br J Midwifery 5(2):100–104

Royal College of Midwives (2019) Evidence-based midwifery. Royal College of Midwives publications. https://www.rcm.org.uk/publications . Accessed 26 Oct 2019

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA et al (1996) Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. Editorial: BMJ. Accessed 16 Oct 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71

Siwha J, Roth C (2004) Evidence-based practice. Ch 4. In: Henderson C, Macdonald S (eds) Mayes Midwifery. Bailliėre Tindall, Edinburgh

Soltani H, Low LK, Schuiling KD et al (2016) Global midwifery research priorities: an international survey. Int J Childbirth 6(1):5–1

Sun C, Larson E (2015) Clinical nursing and midwifery research in African countries: a scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud 52(5):1011–1016

Sun C, Dohrn J, Klopper H et al (2015) Clinical nursing and midwifery research priorities in eastern and southern African countries: results from a Delphi survey. Nurs Res 64(6):466–475

Sweileh WM, Al-Jabi SW, Zyoud SH et al (2019) Nursing and midwifery research activity in Arab countries from 1950 to 2017. [Review]. BMC Health Serv Res 19(1):340. Accessed 18 Oct 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4178-y

The Partnership for Maternal Newborn & Child Health (2011) A Global Review of the Key Interventions Related to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (RMNCH). Geneva, Switzerland: PMNCH.

United Nations Population Fund (2014) State of the world’s midwifery: a universal pathway to women’s health. A United Nations publication, New York

van Wagner V (2017) Midwives using research: evidence-based practice and evidence-informed midwifery. Chapter 12. In: Comprehensive midwifery: the role of the midwife in health care practice, education and research. Press Books, Open Library. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/cmroleofmidwifery/chapter/midwives-using-research-evidence-based-practice-evidence-informed-midwifery/ . Accessed 28 May 2020

Wickham S (2000) Evidence-informed midwifery 3: evaluating midwifery evidence. Midwifery Today Autumn:45–46

World Health Organization (2016a) WHO and partners call for better working conditions for midwives. World Health Organization, Geneva. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/13-10-2016-who-and-partners-call-for-better-working-conditions-for-midwives . Accessed 16 Oct 2019

World Health Organization (2016b) Midwives’ voices, midwives’ realities. Findings from a global consultation on providing quality midwifery care. Originally published under ISBN 978 92 4 151054 7. World Health Organization, Geneva. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250376/9789241510547-eng.pdf;jsessionid=6F7EFCDDC808DE4828446A6FF8B7844B?sequence=1 . Accessed 4 Jun 2020

World Health Organization (2018a) Midwives are essential to the provision of quality of care in all settings, globally. World Health Organization, Geneva. International Day of the Midwife 2018: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/midwives-are-essential-to-the-provision-of-quality-of-care-in-all-settings-globally . Accessed 16 Oct 2019

World Health Organization (2018b) World Health Organization Collaborating Centres: fact sheet. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/about-us/factsheetwhocc2018.pdf?sfvrsn=8c7166ee_2 . Accessed 3 Jun 2020

World Health Organization (2019a) Maternal mental health. Sexual and reproductive health. World Health Organization, Geneva. https://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/maternal_mental_health/en/ . Accessed 12 Apr 2019

World Health Organization (2019b) Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020. World Health Organization, Geneva. https://www.who.int/mental_health/action_plan_2013/en/ . Accessed 12 Apr 2019

World Health Organization (2020) World Health Organization news-room fact sheet: nursing and midwifery. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nursing-and-midwifery . Accessed 3 Jun 2020

Yahui HC, Swaminathan N (2017) Knowledge, attitudes, and barriers towards evidence-based practice among physiotherapists in Malaysia. Hong Kong Physiother J 37:10–18

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Global Professional Advisor, The Royal College of Midwives, London, UK

Maternal and Newborn Health, Department of Interprofessional Health, Swansea University, Swansea, UK

Gaynor D. Maclean

Global Midwifery Advisor, The Hague, Zuid-Holland, The Netherlands

Nester Moyo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joy Kemp .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Kemp, J., Maclean, G.D., Moyo, N. (2021). Strengthening Midwifery Research. In: Global Midwifery: Principles, Policy and Practice. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46765-4_12

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46765-4_12

Published : 06 January 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-46764-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-46765-4

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 18 June 2019

Investigating midwives’ barriers and facilitators to multiple health promotion practice behaviours: a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework

- Julie M. McLellan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4902-2254 1 ,

- Ronan E. O’Carroll 1 ,

- Helen Cheyne 2 &

- Stephan U. Dombrowski 3

Implementation Science volume 14 , Article number: 64 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

27 Citations

26 Altmetric

Metrics details

In addition to their more traditional clinical role, midwives are expected to perform various health promotion practice behaviours (HePPBes) such as informing pregnant women about the benefits of physical activity during pregnancy and asking women about their alcohol consumption. There is evidence to suggest several barriers exist to performing HePPBes. The aim of the study was to investigate the barriers and facilitators midwives perceive to undertaking HePPBes.

The research compromised of two studies.

Study 1: midwives based in a community setting ( N = 11) took part in semi-structured interviews underpinned by the theoretical domains framework (TDF). Interviews were analysed using a direct content analysis approach to identify important barriers or facilitators to undertaking HePPBes.

Study 2: midwives ( N = 505) completed an online questionnaire assessing views on their HePPBes including free text responses ( n = 61) which were coded into TDF domains. Study 2 confirmed and supplemented the barriers and facilitators identified in study 1.