Login Create an NNLM User Account

What Is Health Literacy?

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Healthy People 2030 initiative , health literacy involves the information and services that people need to make well-informed health decisions. There are many aspects of health literacy:

- Personal health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others. Examples of personal health literacy include understanding prescription drug instructions, understanding doctor’s directions and consent forms, and the ability to navigate the complex healthcare system.

- Organizational health literacy is the degree to which organizations equitably enable individuals to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others. Examples of organizational health literacy include simplifying the process to schedule appointments, using the Teach-Back method to ensure patient comprehension, and providing communications in the appropriate language, reading level and format.

- Digital health literacy, as defined by the World Health Organization , is the ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from electronic sources and apply the knowledge gained to addressing or solving a health problem. Examples of digital health literacy include accessing your electronic health record, communicating electronically with your health care team, ability to discern reliable online health information, and using health and wellness apps.

- Numeracy , also known as quantitative literacy, refers to a set of mathematical and advanced problem-solving skills that are necessary to succeed in a society increasingly driven by data, as defined by the National Association of Secondary School Principals . Examples of Numeracy include understanding nutrition information, interpreting blood sugar readings, taking correct dosage of medication (ex. take one capsule twice a day), evaluating treatment benefits and risks, and understanding insurance costs and coverage.

Who Has Limited Health Literacy Skills?

Nearly 9 out of 10 adults struggle with health literacy. Even people with high literacy skills may have low health literacy skills in certain situations. For example, someone who is stressed and sick when they’re accessing health information may have trouble remembering, understanding, and using that information.

Why Is Health Literacy Important?

Health literacy involves more than reading — it also includes specific skills, like calculating the right dose of a medicine, following directions for fasting before a surgery, or checking a nutrition label to make sure an item is safe for someone with a food allergy. People with low health literacy skills may have trouble doing these things.

People with low health literacy skills are more likely to:

- Have poor health outcomes, including hospital stays and emergency room visits

- Make medication errors

- Have trouble managing chronic diseases

- Skip preventive services, like flu shots

People with higher health literacy skills are more likely to make informed health decisions. That means they’re more likely to be healthy — and even to live longer.

How Can We Address Health Literacy?

Communicating clearly with people helps them find and understand health information. And when people understand health information, they can make well-informed health decisions.

We can also consider taking these steps to address health literacy:

- Ensure that people in the community can easily access the health information they need

- Create and provide plain language health materials in different languages

- Provide trainings to teach health professionals and others who provide health information about health literacy best practices

- Create clearinghouses of information about health literacy for health professionals

- Review health materials (like insurance forms and medication instructions) with community members to help make sure they understand the information — and what actions they need to take

You can find more information about Health Literacy in MedlinePlus . To find journal articles about Health Literacy, you can use the MEDLINE/PubMed health literacy search to retrieve citations to English language journal literature.

How does NNLM support Health Literacy?

Training. The Network of the National Library of Medicine offers training for those who provide health information to the public such as our On Demand Health Literacy Class . Many of our trainings support the understanding of health literacy and its effects on health while others help professionals gain needed skills to address health literacy in their communities.

Resources. NNLM creates and promotes resources that can support network members in improving the health literacy of their communities. These resources include:

- Clinical Conversations is a training program for clinicians about health literacy and related concepts. This program allows clinical trainers or managers to offer brief trainings embedded into existing meetings or trainings as a way to offer continuing education that does not take time out of already busy schedules.

- Project SHARE is a program developed by the University of Maryland Health Sciences and Human Services Library and funded by the National Library of Medicine. Project SHARE aims to build high school students' skills to reduce health disparities at the personal, family and community level. Module II of the curriculum focuses on health literacy.

- Digital Health Literacy Tools from NNLM and All of Us in partnership with the Public Library Association (PLA) and Wisconsin Health Literacy aim to reach people on the other side of the digital divide. These tools help people gain the digital literacy skills needed to access and evaluate health information online and to participate in the All of Us Research Program (All of Us).

- Evaluating Internet Health Information: A Tutorial from the National Library of Medicine and MedlinePlus teaches people how to evaluate a variety of sources on the internet to determine how to find reliable sources. This also teaches people how to make proactive decisions about their health.

Funding. NNLM’s Regional Medical Libraries offer grant funding in their respective regions. Funded projects often address health literacy by linking members of the community with quality health information resources and providing training on their use. Other projects address health literacy by offering training to information professionals, healthcare providers or other health professionals about how to support and address health literacy in their communities. Select projects are highlighted in the videos below. More information about funding, including additional previously funded projects is available on NNLM’s funding page.

Promotores de Salud (Tucson, AZ)

NLM Outreach - Wash and Learn (St Paul, MN)

Technology Outreach to Reduce Health Disparities and Stigma

Health Literacy Projects

Browse NNLM's past funded projects to gain inspiration for your health literacy project.

Health Literacy in Healthy People 2030

Health literacy is a central focus of Healthy People 2030. One of the initiative’s overarching goals demonstrates this focus: “Eliminate health disparities, achieve health equity, and attain health literacy to improve the health and well-being of all.”

Watch this video to learn more about health literacy:

Which Healthy People 2030 objectives are related to health literacy?

Six Healthy People objectives — developed by the Health Communication and Health Information Technology Workgroup — are related to health literacy:

- Increase the proportion of adults whose health care provider checked their understanding — HC/HIT‑01

- Decrease the proportion of adults who report poor communication with their health care provider — HC/HIT‑02

- Increase the proportion of adults whose health care providers involved them in decisions as much as they wanted — HC/HIT‑03

- Increase the proportion of people who say their online medical record is easy to understand — HC/HIT‑D10

- Increase the proportion of adults with limited English proficiency who say their providers explain things clearly — HC/HIT‑D11

- Increase the health literacy of the population — HC/HIT‑R01

How does Healthy People define health literacy?

Healthy People 2030 addresses both personal health literacy and organizational health literacy and provides the following definitions:

- Personal health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.

- Organizational health literacy is the degree to which organizations equitably enable individuals to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.

These definitions are a change from the health literacy definition used in Healthy People 2010 and Healthy People 2020: “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.” The new definitions:

- Emphasize people’s ability to use health information rather than just understand it

- Focus on the ability to make “well-informed” decisions rather than “appropriate” ones

- Incorporate a public health perspective

- Acknowledge that organizations have a responsibility to address health literacy

Learn more about the history of Healthy People’s health literacy definitions .

Personal health literacy

Healthy People 2030’s definition of personal health literacy is aligned with the concept that people’s health literacy can be assessed at a given point in time. Such a definition is important for conducting both population studies and research on interventions aimed at ensuring equal access to information and services for people with limited literacy skills.

The new definition — with its emphasis on the use of health information and its public health perspective — may also prompt new ways of studying and promoting personal health literacy. In addition, it encourages efforts to address the skills that help people move from understanding to action and from a focus on their own health to a focus on the health of their communities.

Organizational health literacy

By adopting a definition for organizational health literacy, Healthy People acknowledges that personal health literacy is contextual and that producers of health information and services have a role in improving health literacy. The definition also emphasizes organizations’ responsibility to equitably address health literacy, in line with Healthy People 2030’s overarching goals.

In addition, including a definition for organizational health literacy in Healthy People aligns with the HHS National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy .

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

Patient education and health literacy

Affiliations.

- 1 Research Group Lifestyle and Health, Utrecht University of Applied Sciences, Heidelberglaan 7, 3584 CS, Utrecht, The Netherlands. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Research Group Lifestyle and Health, Utrecht University of Applied Sciences, Heidelberglaan 7, 3584 CS, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- PMID: 30017902

- DOI: 10.1016/j.msksp.2018.06.004

Introduction: Patient education is a relatively new science within the field of health care. In the past it consisted mainly of the transfer of knowledge and mostly biomedically based advice. Research has shown this to not be effective and sometimes counterproductive. As health care has moved away from applying a traditional paternalistic approach of 'doctor knows best' to a patient-centred care approach, patient education must be tailored to meet persons' individual needs.

Purpose: The purpose of this master paper is to increase awareness of patients' health literacy levels. Health literacy is linked to literacy and entails people's knowledge, motivation and competences to access, understand, appraise and apply health information in order to make judgements and take decisions in everyday life concerning health care, disease prevention and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life during the life course. Many patients have low health literacy skills, and have difficulty with reading, writing, numeracy, communication, and, increasingly, the use of electronic technology, which impede access to and understanding of health care information.

Implications: Multiple professional organizations recommend using universal health literacy precautions to provide understandable and accessible information to all patients, regardless of their literacy or education levels. This includes avoiding medical jargon, breaking down information or instructions into small concrete steps, limiting the focus of a visit to three key points or tasks, and assessing for comprehension by using the teach back cycle. Printed information should be written at or below sixth-grade reading level. Visual aids can enhance patient understanding.

Keywords: Biopsychosocial; Health literacy; Patient centred care; Patient education.

Copyright © 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

- Aged, 80 and over

- Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice*

- Health Literacy*

- Middle Aged

- Patient Education as Topic / methods*

- Patient-Centered Care / methods*

- MEMBER DIRECTORY

- Member Login

- Publications

- Clinician Well-Being

- Culture of Health and Health Equity

- Fellowships and Leadership Programs

- Future of Nursing

- U.S. Health Policy and System Improvement

- Healthy Longevity

- Human Gene Editing

- U.S. Opioid Epidemic

- Staff Directory

- Opportunities

- Action Collaborative on Decarbonizing the U.S. Health Sector

- Climate Communities Network

- Communicating About Climate Change & Health

- Research and Innovation

- Culture of Health

- Fellowships

- Emerging Leaders in Health & Medicine

- Culture & Inclusiveness

- Digital Health

- Evidence Mobilization

- Value Incentives & Systems

- Substance Use & Opioid Crises

- Reproductive Health, Equity, & Society

- Credible Sources of Health Information

- Emerging Science, Technology, & Innovation

- Pandemic & Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Preparedness and Response

- Preventing Firearm-Related Injuries and Deaths

- Vital Directions for Health & Health Care

- NAM Perspectives

- All Publications

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- MEMBER HOME

Health Literacy and Health Education in Schools: Collaboration for Action

Introduction

This NAM Perspectives paper provides an overview of health education in schools and challenges encountered in enacting evidence-based health education; timely policy-related opportunities for strengthening school health education curricula, including incorporation of essential health literacy concepts and skills; and case studies demonstrating the successful integration of school health education and health literacy in chronic disease management. The authors of this manuscript conclude with a call to action to identify upstream, systems-level changes that will strengthen the integration of both health literacy and school health education to improve the health of future generations. The COVID-19 epidemic [10] dramatically demonstrates the need for children, as well as adults, to develop new and specific health knowledge and behaviors and calls for increased integration of health education with schools and communities.

Enhancing the education and health of school-age children is a critical issue for the continued well-being of our nation. The 2004 Institute of Medicine (IOM, now the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM]) report, Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion [27] noted the education system as one major pathway for improving health literacy by integrating health knowledge and skills into the existing curricula of kindergarten through 12th-grade classes. The NASEM Roundtable on Health Literacy has held multiple workshops and forums to “inform, inspire, and activate a wide variety of stakeholders to support the development, implementation, and sharing of evidence-based health literacy practices and policies” [37]. This paper strives to present current evidence and examples of how the collaboration between health education and health literacy disciplines can strengthen K–12 education, promote improved health, and foster dialogue among school officials, public health officials, teachers, parents, students, and other stakeholders.

This discussion also expands on a previous NAM Perspectives paper, which identified commonalities and differences in the fields of health education, health literacy, and health communication and called for collaboration across the disciplines to “engage learners in both formal and informal health educational settings across the life span” [1]. To improve overall health literacy, i.e., “the capacity of individuals to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” [42], it is important to start with youth, when life-long health habits are first being formed.

Another recent NAM Perspectives paper proposed the expansion of the definition of health literacy to include broader contextual factors, including issues that impact K–12 health education efforts like state rather than federal control of education priorities and administration, and subsequent state- or local-level laws that impact specific school policies and practices [39]. In addition to addressing individual needs and abilities, socio-ecological factors can impact a student’s health. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uses a four-level social-ecological model to describe “the complex interplay” of (1) individuals (biological and personal history factors), (2) relationships (close peers, family members), (3) community (settings such as neighborhoods, schools, after-school locations), and (4) societal factors (cultural norms, policies related to health and education, or inequalities between groups in societies) that put one at risk or prevent him/her from experiencing negative health outcomes [11]. Also worth examining are protective factors that help children and adolescents avoid behaviors that place them at risk for adverse health and educational outcomes (e.g., self-efficacy, self-esteem, parental support, adult mentors, and youth programs) [21,59].

Recognizing the influence of this larger social context on learning and health can help catalyze both individual and community-based solutions. For example, students with chronic illnesses such as asthma, which can affect their school attendance, can be educated about the impact of air quality or housing (e.g., mold, mites) in exacerbating their condition. Students in varied locations and at a range of ages continue, often with the guidance of adults, to take health-related social action. Various local, national, and international examples illustrate high schoolers taking social action related to health issues such as tobacco, gun safety, and climate change [18,21,57].

By employing a broad approach to K–12 education (i.e., using combined principles of health education and health literacy), the authors of this manuscript foresee a template for the integration of skills and abilities needed by both school health professionals and children and parents to increase health knowledge for a lifetime of improved health [1,29,31].

The right measurements to evaluate success and areas that need improvement must be clearly identifed because in all matters related to health education and health literacy, it is vital to document the linkages between informed decisions and actions. Often, individuals are presumed to be making informed decisions when actually broader socio-ecological factors are predominant behavioral influences (e.g., an individual who is overweight but has never learned about food labeling and lives in a community where there are no safe places to be physically active).

Health Education in Schools

Standardized and broadly adopted strategies for how health education is implemented in schools—and by whom and on what schedule—is a continuing challenge. Although the principles of health literacy are inherently important to any instruction in schools and in community settings, the most effective way to incorporate those principles in existing and differing systems becomes a key to successful health education for children and young people.

The concept of incorporating health education into the formal education system dates to the Renaissance. However, it did not emerge in the United States until several centuries later [26]. In the early 19th century, Horace Mann advocated for school-based health instruction, while William Alcott also underscored the contributions of health services and the school environment to children’s health and well-being [17]. Public health pioneer Lemuel Shattuck wrote in 1850 that “every child should be taught early in life, that to preserve his own life and his own health and the lives of others, is one of the most important and abiding duties” [43]. During this same time, Harvard University and other higher education institutions with teacher preparation programs began including hygiene (health) education in their curricula.

Despite such early historical recognition, in the mid-1960s, the School Health Education Study documented serious disarray in the organization and administration of school health education programs [45]. A renewed call to action, several decades later, introduced the concepts of comprehensive school health programs and school health education [26].

From 1998 through 2014, the CDC and other organizations began using the term “coordinated school health programs” to encompass eight components affecting children’s health in schools, including nutrition, health services, and health instruction. Unfortunately, the term was not broadly embraced by the educational sector, and in 2014, CDC and ASCD (formerly the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development) unveiled the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) framework [36]. This framework has ten components, including health education, which aims to ensure that each student is healthy, safe, engaged, supported, and challenged. Among the foundational tenets of the framework is ensuring that every student enters school healthy and, while there, learns about and practices a healthy lifestyle.

At its core, health education is defined as “any combination of planned learning experiences using evidence-based practices and/or sound theories that provide the opportunity to acquire knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed to adopt and maintain healthy behaviors” [3]. Included are a variety of physical, social, emotional, and other components focused on reducing health-risk behaviors and promoting healthy decision making. Health education curricula emphasize a skills-based approach to help students practice and advocate for their health needs, as well as the needs of their families and their communities. These skills help children and adolescents find and evaluate health information needed for making informed health decisions and ultimately provide the foundation of how to advocate for their own well-being throughout their lives.

In the last 40 years, many studies have documented the relationship between student health and academic outcomes [29,40,41]. Health-related problems can diminish a student’s motivation and ability to learn [4]. Complications with vision, hearing, asthma, occurrences of teen pregnancy, aggression and violence, lack of physical activity, and low cognitive and emotional ability can reduce academic success [4].

To date, there have been no long-term sequential studies of the impact of K–12 health education curricula on health literacy or health outcomes. However, research shows that students who participate in health education curricula in combination with other interventions as part of the coordinated school health model (i.e., physical activity, improved nutrition, and/or family engagement) have reduced rates of obesity and/ or improved health-promoting behaviors [25,30,34]. In addition, school health education has been shown to prevent tobacco and alcohol use and prevent dating aggression and violence. Teaching social and emotional skills improves the academic behaviors of students, increases motivation to do well in school, enhances performance on achievement tests and grades, and improves high school graduation rates.

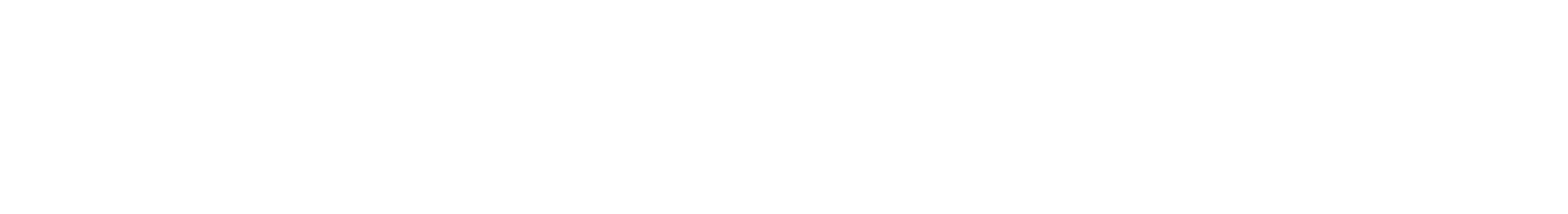

As with other content areas, it is up to the state and/or local government to determine what should be taught, under the 10th Amendment to the US Constitution [48]. However, both public and private organizations have produced seminal documents to help guide states and local governments in selecting health education curricula. First published in 1995 and updated in 2004, the National Health Education Standards (NHES) framework comprises eight health education foundations for what students in kindergarten through 12th grade should know and be able to do to promote personal, family, and community health (see Table 1 ) [12]. The NHES framework serves as a reference for school administrators, teachers, and others addressing health literacy in developing or selecting curricula, allotting instructional resources, and assessing student achievement and progress. The NHES framework contains written expectations for what students should know and be able to do by grades 2, 5, 8, and 12 to promote personal, family, and community health.

The Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH) model, which was first developed in the late 1980s with funds by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, serves to implement the NHES framework and was the largest school-based health promotion study ever conducted in the United States. CATCH has 25 years of continuous research and development of its programs [24] and aligns with the WSCC framework. Individualized programs like the CATCH model develop programming based on the NHES framework at the local level, so that local control still exists, but the mix and depth of topics can vary based on need and composition of the community.

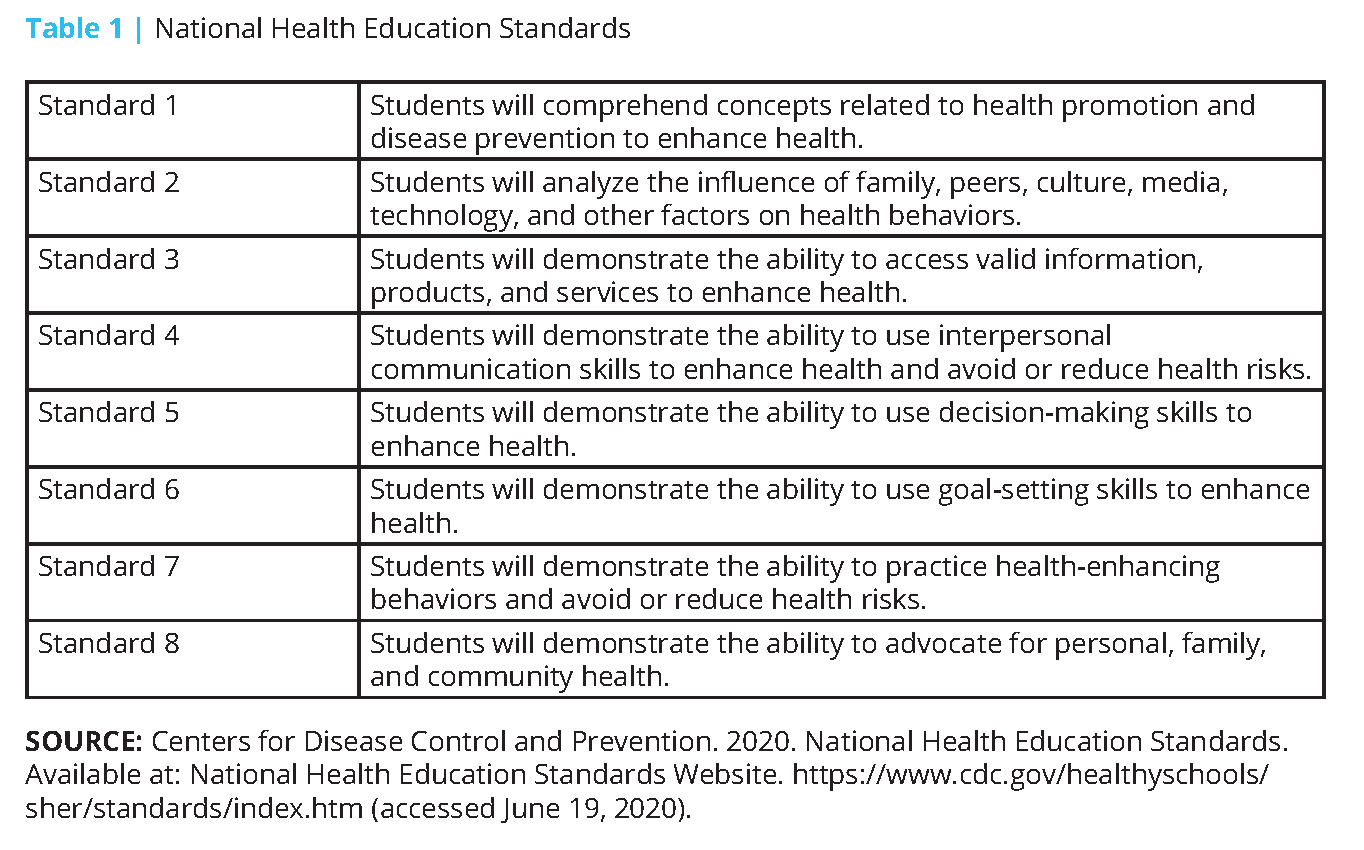

Based on reviews of effective programs and curricula and experts in the field of health education, CDC recommends that today’s state-of-the-art health education curricula emphasize four core elements: “Teaching functional health information (essential knowledge); shaping personal values and beliefs that support healthy behaviors; shaping group norms that value a healthy lifestyle; and developing the essential health skills necessary to adopt, practice, and maintain health enhancing behavior” [13]. In addition to the 15 characteristics presented in Box 1 , the CDC website has more detailed explanations and examples of how the statements could be put into practice in the classroom. For example, a curriculum that “builds personal competence, social competence, and self-efficacy by addressing skills” would be expected to guide students through a series of developmental steps that discuss the importance of the skill, its relevance, and relationship to other learned skills; present steps for developing the skill; model the skill; practice and rehearse the skill using real-life scenarios; and provide feedback and reinforcement.

In addition, CDC has developed a Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool [14] to help schools conduct an analysis of health education curricula based on the NHES framework and the Characteristics of an Effective Health Education Curriculum.

Despite CDC’s extensive efforts during the past 40 years to help schools implement effective school health education and other components of the broader school health program, the integration of health education into schools has continued to fall short in most US states and cities. According to the CDC’s 2016 School Health Profiles report, the percentage of schools that required any health education instruction for students in any of grades 6 through 12 declined. For example, 8 in 10 US school districts only required teaching about violence prevention in elementary schools and violence prevention plus tobacco use prevention in middle schools, while instruction in only seven health topics was required in most high schools [6].

Although 8 of every 10 districts required schools to follow either national, state, or district health education standards, just over a third assessed attainment of health standards at the elementary level while only half did so at the middle and high school levels [6]. No Child Left Behind legislation, enacted in 2002, emphasized testing of core subjects, such as reading, science, and math, which resulted in marginalization of other subjects, including health education [22,31]. Academic subjects that are not considered “core” are at risk of being eliminated as public school principals and administrators struggle to meet adequate yearly progress for core subjects, now required to maintain federal funding.

In addition to the quality and quantity of health education taught in schools, there are numerous problems related to those considered qualified to provide instruction [5,7]. Many school and university administrators lack an understanding of the distinction between health education and physical education (PE) [9,16,19] and consider PE teachers to be qualified to teach health education. Yet the two disciplines differ regarding national standards, student learning outcomes, instructional content and methods, and student assessment [5]. Kolbe notes that making gains in school health education will require more interdisciplinary collaboration in higher education (e.g., those training the public health workforce, the education workforce, school nurses, pediatricians) [29]. Yet faculty who train various school health professionals usually work within one university college, focus on one school health component, and affiliate with one national professional organization. In addition, Kolbe notes that health education teachers in today’s workforce often lack support and resources for in-service professional development.

Promising Opportunities for Strengthening School Health Education

Comprehensive health education can increase health literacy, which has been estimated to cost the nation $1.6 to $3.6 trillion dollars annually [54]. The National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) includes the goal to “Incorporate accurate, standards-based, and developmentally appropriate health and science information and curricula in childcare and education through the university level” [49].

HHS’s Healthy People Framework presents another significant opportunity for tracking health in education as well as health literacy. The Healthy People initiative launched officially in 1979 with the publication of Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention [50]. This national effort establishes 10-year goals and objectives to improve the health and well-being of people in the United States. Since its inception, Healthy People has undertaken extensive efforts to collect data, assess progress, and engage multi-stakeholder feedback to set objectives for the next ten years. The Healthy People 2020 objectives were self-described as having input from public health and prevention experts, a wide range of federal, state, and local government officials, a consortium of more than 2,000 organizations, and perhaps most importantly, the public” [51]. In addition to other childhood and adolescent objectives (e.g., nutrition, physical activity, vaccinations), Healthy People 2020 specified social determinants as a major topic for the first time. A leading health indicator for social determinants was “students graduating from high school within 4 years of starting 9th grade (AH-5.1)” [52]. The Secretary’s Advisory Committee report on the Healthy People 2030 objectives includes the goal to “eliminate health disparities, achieve health equity, and attain health literacy to improve the health and well-being of all” [53]. The national objectives are expected to be released in summer 2020 and will help catalyze “leadership, key constituents, and the public across multiple sectors to take action and design policies that improve the health and well-being of all” [53].

In terms of supports in federal legislation, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015 recognized health education as a distinct discipline for the first time and designated it as a “well-rounded” education subject [2,22]. According to Department of Education guidelines, each state must submit a plan that includes four academic indicators that include proficiency in math, English, and English-language proficiency. High schools also must use their graduation rates as their fourth indicator, while elementary and middle schools may use another academic indicator. In addition, states must specify at least one nonacademic indicator to measure school quality or school success, such as health education. Under the law, federal funding also is available for in-service instruction for teachers in well-rounded education subjects such as health education. These two items open additional pathways for both identifying existing or added programs and having the capacity to collect data.

While several states have chosen access to physical education, physical fitness, or school climate as their nonacademic indicators of school success, the majority (36 states and the District of Columbia) have elected to use chronic absenteeism [2]. Given the underlying causal connection between student health and chronic absenteeism, absenteeism as an indicator represents a significant opportunity to raise awareness of chronic health conditions or other issues (e.g., student social/emotional concerns around bullying, school safety) that contribute to absenteeism. It also represents a significant opportunity for schools to work with stakeholders to prevent and manage such health conditions through school health education and other WSCC strategies to improve school health. Educators are more likely to support comprehensive health education if they are made aware of its immediate benefits related to student learning (e.g., less disruptive behavior, improved attention) and maintaining safe social and emotional school climates [31].

In an assessment of how states are addressing WSCC, Child Trends reported that health education is either encouraged or required for all grades in all states’ laws, with nutrition (40 states) and personal health (44 states) as the most prominent topics [15]. However, the depth and breadth of such instruction in schools is not known, nor if health education is being taught by qualified teachers. In 25 states, laws address or otherwise incorporate the NHES as part of the state health education curriculum.

The authors’ review of state 2017–2018 ESSA plans, analyzed by the organization Cairn, showed nine states that have specifically identified health education as one of its required well-rounded subjects (Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Nevada, North Dakota, and Tennessee) [8]. Cairn recommends that most states include health education and physical education in state accountability systems, school report card indicators, school improvement plans, professional development plans, needs assessment tools, and/or prioritized funding under Title IV, Part A.

In 2019, representatives of the National Committee on the Future of School Health Education, sponsored by the Society for Public Health Education (SOPHE) and the American School Health Association (ASHA), published a dozen recommendations for strengthening school health education [5,31,55]. The recommendations addressed issues such as developing and adopting standardized measures of health literacy in children and including them in state accountability systems; changing policies, practices, and systems for quality school health education (e.g., establishing Director of School Health Education positions in all state and territory education agencies tasked with championing health education best practices, and holding schools accountable for improving student health and wellbeing); and strengthening certification, professional preparation, and ongoing professional development in health education for teachers at both the elementary and secondary levels. Recommendations also call for stronger alignment and coordination between the public health and education sectors. The committee is now moving ahead on prioritizing the recommendations and developing action steps to address them.

Integrating Youth Health Education and Health Literacy: Success Stories

Minnesota statewide model: integrating school health education and health literacy through broad partnership.

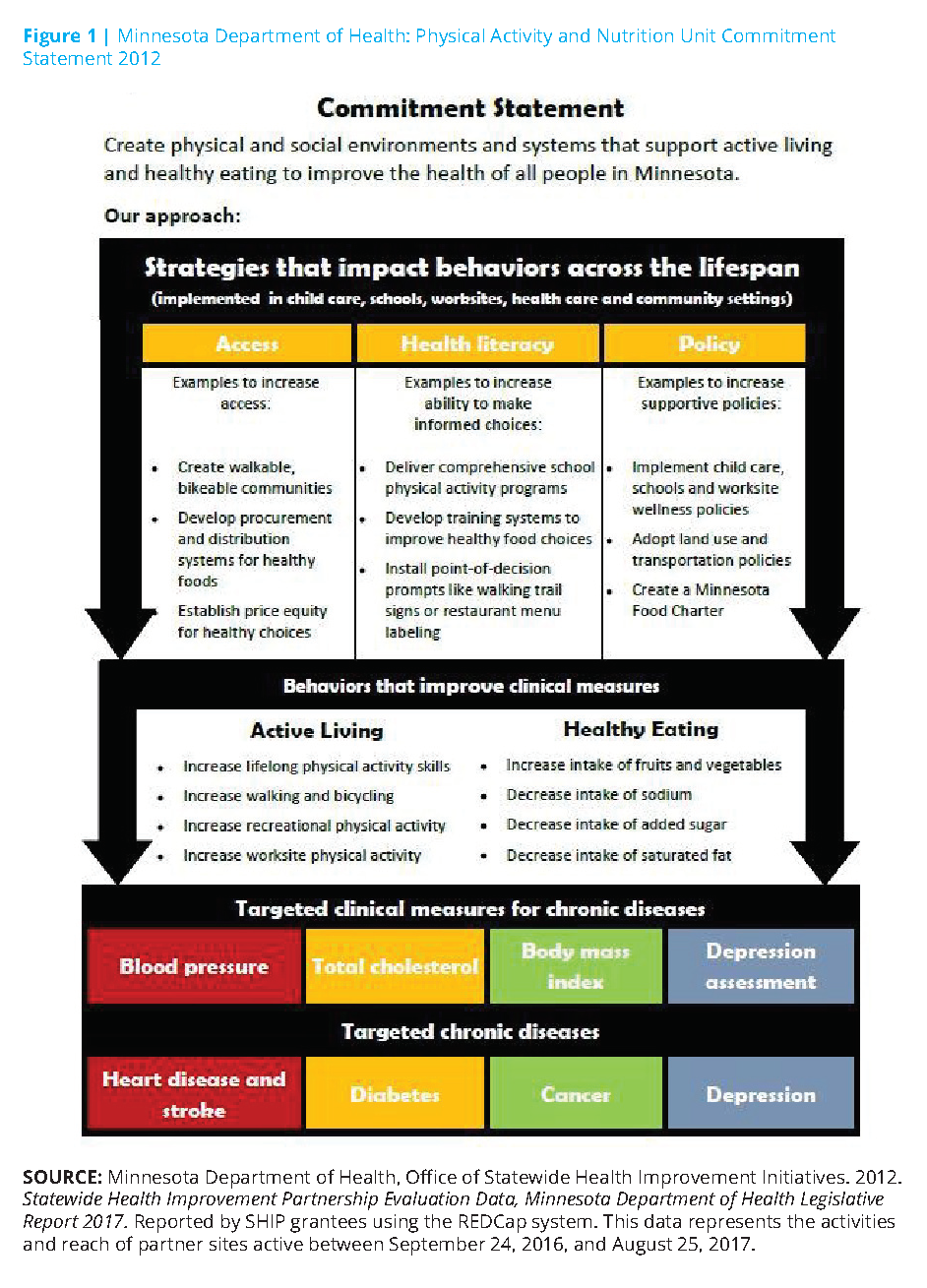

The Roundtable on Health Literacy held a workshop on health literacy and public health in 2014, with examples of how state health departments are addressing health literacy in their states [28]. One recent example of a strong collaboration between K–12 education and public health agencies is the Statewide Health Improvement Partnership (SHIP) within the Minnesota Department of Health’s Office of Statewide Health Initiative [35].

SHIP was created by a landmark 2008 Minnesota health reform law. The law was intended to improve the health of Minnesotans by reducing the risk factors that lead to chronic disease. The program funds grantees in all of the state’s 87 counties and 10 tribal nations to support the creation of locally driven policies, systems, and environmental changes to increase health equity, improve access to healthy foods, provide opportunities for physical activity, and ensure a tobacco-free environment [35]. Local public health agencies collaborate with partners including schools, childcare settings, workplaces, multiunit housing facilities, and health care centers through SHIP.

SHIP models the integration of (1) law, (2) policy, (3) goal-setting, and (4) resource building and forging some 2,000 collaborative partnerships and measuring outcomes. SHIP sets a helpful example for others attempting to create synergies across the intersections of state government, health education, local communities, and private organizations. The principles of health literacy are within these collaborations.

Grantees throughout the state have received technical assistance and training to improve school nutrition and physical activity strategies (see Figure 1 ). SHIP grantees and their local school partner sites set goals and adopt best practices for physical education and physical activity inside and outside the classroom. They improve access to healthy food environments through locally sourced produce, lunchrooms with healthier food options, and school-based agriculture. In 2017, SHIP grantees partnered with 995 local schools and accounted for 622 policy, systems, and environmental changes.

Minnesota has also undertaken a broad approach to health literacy by educating stakeholders and decision-makers (i.e., administrators, food service and other staff, students, community partners, and parents) about various health-related social and environmental issues to reduce students’ chronic disease risks.

SHIP grantees assist in either convening or organizing an established school health/wellness council that is required by USDA for each local education agency participating in the National School Lunch Program and/or School Breakfast Program [46,47]. A local school wellness policy is required to address the problem of childhood obesity by focusing on nutrition and physical activity. SHIP also requires schools to complete an assessment that aligns with the WSCC model and provides annual updates. Once the assessment is completed by a broad representation of stakeholders, SHIP grantees assist schools in prioritizing and working toward annual goals. The goal-setting and assessment and goal-setting cycle is continuous.

The Bigger Picture: A Case Study of Community Integration of Health Education and Health Literacy

Improving the health literacy of young people not only influences their personal health behaviors but also can influence the health actions of their peers, their families, and their communities. According to the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study funded by the CDC and the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases, from 2002 to 2012, the national rate of new diagnosed cases of Type 2 diabetes increased 4.8% [32]. Among youth ages 10-19, the rate of new diagnosed cases of Type 2 diabetes rose most sharply in Native Americans (8.9%) (although not generalizable to all Native American youth because of small sample size), compared to Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders (8.5%), non-Hispanic blacks (6.3%), Hispanics (3.1%), and non-Hispanic whites (0.6%).

Since 2011, Dean Schillinger, Professor of Medicine in Residence at the University of California San Francisco and Chief of the Diabetes Prevention and Control Program for the California Department of Public Health, has led a capacity-building effort to address Type 2 diabetes [23,28,44].

This initiative called The Bigger Picture (TBP) has mobilized collaborators to create resources by and for young adults focused on forestalling and, hopefully, reversing the distressing increase in pediatric Type 2 diabetes by exposing the environmental and social conditions that lead to its spread. Type 2 diabetes is increasingly affecting young people of color, and TBP is specifically developed by and directed to them.

TBP seeks to increase the number of well-informed young people who can participate in determining their own lifelong health behaviors and influencing those of their friends, families, communities, and their own children. The project aims to create a movement that changes the conversation about diabetes from blame-and-shame to the social drivers of the epidemic [23].

TPB is described by the team that created it as a “counter-marketing campaign using youth-created, spoken-word public services announcements to reframe the epidemic as a socio-environmental phenomenon requiring communal action, civic engagement, and norm change” [44]. The research team provides a description of questionnaire responses to nine of the public service announcements in the context of campaign messages, film genre and accompanying youth value, participant understanding of fi lm’s public health message, and the participant’s expression of the public health message. The investigators also correlate the responses with dimensions of health literacy such as conceptual foundations, functional health literacy, interactive health literacy, critical skills, and civic orientation.

One of the campaign partners, Youth Speaks, has created a toolkit to equip and empower students and communities to become change agents in their respective environments, raising their voices and joining the conversation about combating the spread of Type 2 diabetes [56].

In a discussion of qualitative evaluations of TBP and what low-income youth “see,” Schillinger et al. note that “TBP model is unique in how it nurtures and supports the talent, authenticity, and creativity of new health messengers: youth whose lived experience can be expressed in powerful ways” [44].

COVID-19: Health Crisis Affecting Children and their Families and a Need for Health Education and Health Literacy in K-12

In a recent op-ed, Rebecca Winthrop, co-director of the Center for Universal Education and Senior Fellow of Global and Economic Development of the Brookings Institution asked, “COVID-19 is a health crisis. So why is health education missing from school work?” [58] She notes that “helping sustain education amid crises in over 20 countries, I’ve learned that one of the first things you do, after finding creative ways to continue educational activities, is to incorporate life-saving health and safety messages.” Her call is impassioned for age-appropriate, immediately available resources on COVID-19 that can be easily incorporated into distance lesson plans for both children and families. Many organizations, such as Child Trends, are curating collections of such resources. Framing these materials using principles of health literacy and incorporating them into health education messages and resources may be an ideal model for incorporating new pathways for public health K–12 learning.

Call to Action for Collaboration

Strategic and dedicated efforts are needed to bridge health education and health literacy. These efforts would foster the expertise to provide students with the information needed to access and assess useful health information, and to develop the necessary skills for an emerging understanding of health.

Starting with students in school settings, learning to be health literate helps overcome the increased incidence of chronic diseases such as Type 2 diabetes, and imbues a sense of self-efficacy and empowerment through health education. It also sets the course for lifelong habits, skills, and decision making, which can also influence community health.

Pursuing institutional changes to reduce disparities and improve the health of future generations will require significant collaboration and quality improvement among leaders within health education and health literacy. Recommendations provided in previous reports such as IOM’s 1997 report, Schools and Health: Our Nation’s Investment [26]; the 2004 IOM report on Health Literacy [27]; and the 2010 National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy [49] should be revisited. More recently, a November 2019 Health Literacy Roundtable Workshop (1) explored the necessity of developing health literacy skills in youth, (2) examined the research on developmentally appropriate health literacy milestones and transitions and measuring health literacy in youth, (3) described programs and policies that represent best practices for developing health literacy skills in youth, and (4) explored potential collaborations across disciplines for developing health literacy skills in youth [38]. With its resulting report, the information provided in the workshop should provide additional insights into collaborations needed to reduce institutional barriers to youth health literacy and empowerment.

At the national level, representatives from public sector health and education levels (e.g., HHS’s Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC, Department of Education) can collaborate with school-based nongovernmental organizations (e.g., SOPHE, ASCD, ASHA, National Association of State Boards of Education, School Superintendents Association, Council of Chief State School Officers, Society of State Leaders of Health and Physical Education) to provide data and lead reform efforts. Leaders of higher education (e.g., Association of American Colleges and Universities, Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health) can join with philanthropies and educational scholars to pursue curricular reforms and needed research to further health education and health literacy as an integral component of higher education.

Among the approaches needed are (1) careful incorporation of key principles of leadership within systems; (2) the training and evaluation of professionals; (3) finding and sharing replicable, effective examples of constructive efforts; and (4) including young people in the development of information and materials to ensure their accessibility, appeal, and utility. Uniting the wisdom, passion, commitment, and vision of the leaders in health literacy and health education, we can forge a path to a healthier generation.

Join the conversation!

Download the graphics below and share them on social media!

- Allen, M., E. Auld, R. Logan, J. Henry Montes, and S. Rosen. 2017. Improving collaboration among health communication, health education, and health literacy. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201707c

- Alliance for a Healthier Generation. 2018. Every Student Succeeds Act Frequently Asked Questions. Available at: https://www.healthiergeneration.org/sites/default/files/documents/20180814/3beb1de8/ESSA-FAQ.pdf (accessed May 3, 2020).

- American Association for Health Education. 2012. Report of the 2011 Joint Committee on Health Education and Promotion Terminology. American Journal of Health Education 43:sup2, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2012.11008225

- Basch, C. E. 2011. Healthier students are better learners: A missing link in school reforms to close the achievement gap. Journal of School Health 81:593-598. Available at: https://healthyschoolscampaign.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/AMissing-Link-in-School-Reforms-to-Closethe-Achievement-Gap.pdf (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Birch, D. A., S. Goekler, M. E. Auld, D. K. Lohrmann, and A. Lyde. 2019. Quality assurance in teaching K–12 health education: Paving a new path forward. Health Promotion Practice 20(6):845-857. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919868167

- Brener, N. D., Z. Demissie, T. McManus, S. L. Shanklin, B. Queen, and L. Kann. 2017. School Health Profiles 2016: Characteristics of Health Programs Among Secondary Schools. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/profiles/pdf/2016/2016_Profiles_Report.pdf (accessed May 18, 2020).

- McCormack Brown, K. R. 2013. Health education in higher education: What is the future? American Journal of Health Education 44(5):245-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2013.807755

- Cairn. 2020. State ESSA Plans . Available at: http://www.cairnguidance.com/essa-plans/ (accessed May 3, 2020).

- Cardina, C. 2014. Academic majors and subject-area certifications of health education teachers in the United States, 2011-2012. Journal of Health Education Teaching 5(1):35-43. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1085288 (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/ (accessed June 17, 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2015. Principles of community engagement, 2nd ed. Atlanta, GA: CDC/ATSDR Committee on Community Engagement. Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/index.html (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2019a. National Health Education Standards Website. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/sher/standards/index.htm (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2019b. Characteristics of an Effective Health Education Curriculum Website. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/sher/characteristics/index.htm (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019c. Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool (HECAT). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/hecat/index.htm (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Child Trends. 2019. State statutes and regulations for healthy schools: Health education. Available at: https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/WSCC-State-Policy-Health-Education.pdf (accessed May 28, 2019).

- Cobb, R. S. 1981. Health Education…A separate and unique discipline. Journal of School Health 51(9):603-604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1981.tb02243.x.

- Cottrell, R. R., J. T. Girvan, J. F. McKenzie, and D. Seabert. 2018. Principles and Foundations of Health Promotion and Education, 7th ed. Pearson: New York.

- Dubb, S. 2019. Parkland Students Outline Gun Safety Vision in Comprehensive Plan. Nonprofit Quarterly. Available at: https://nonprofi tquarterly.org/parkland-students-outline-gun-safety-vision-in-comprehensive-plan/ (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Goodwin, S. C. 1993. Health and physical education—Agonists or antagonists? Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance 64(7):74-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.1993.1060679

- Gould, L., E. Mogford, and A. DeVoght. 2010. Successes and Challenges of Teaching the Social Determinants of Health in Secondary Schools: Case Examples in Seattle, Washington. Health Promotion Practice 11(3):26S-33S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839909360172

- Guhne, J. 2001. Students send magazines’ tobacco ads back to publishers in “Don’t Buy” effort. Baltimore Sun. Available at: https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-2001-04-12-0104120141-story.html (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Hampton, C., A. Alikhani, M. E. Auld, and V. White. 2017. Advocating for Health Education in Schools (Policy brief). Society for Public Health Education: Washington, DC. Available at: https://www.sophe.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/ESSAPolicy-Brief.pdf (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Hoffman, A. 2016. In San Francisco, the fight against diabetes gets personal: A local doctor tries to raise awareness about the social causes of Type 2 diabetes, in his community and others. CityLab. Available at: https://www.citylab.com/life/2014/11/in-san-francisco-the-fight-against-diabetes-getspersonal/382275/ (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Hoelscher, D. M., H. A. Feldman, C. C. Johnson, L. A. Lytle, S. K. Osganian, G. S. Parcel, S. H. Kelder, E. J. Stone, and P. R. Nader. 2004. School-based health education programs can be maintained over time: Results from the CATCH Institutionalization study. Preventive Medicine 38(5):594-606. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743503003311 (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Hoelscher, D. M., A. E. Springer, N. Ranjit, C. L. Perry, A. E. Evans, M. Stigler, and S. H. Kelder. 2010. Reductions in child obesity among disadvantaged school children with community involvement: The Travis County CATCH Trial. Obesity 18(1):36-44. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/oby.2009.430.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). 1997. Schools and Health: Our Nation’s Investment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/5153.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). 2004. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10883.

- Institute of Medicine. 2014. Implications of Health Literacy for Public Health: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18756.

- Kolbe, L. 2019. School health as both a strategy to improve both public health and education. Annual Review of Public Health 40:443-463. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043727.

- Luepker, R. V., C. L. Perry, S. M. McKinlay, P. R. Nader, G. S. Parcel, E. J. Stone, L. S. Webber, J. P. Elder, H. A. Feldman, C. C. Johnson, S. H. Kelder, M. Wu, P. Nader, J. Elder, T. McKenzie, K. Bachman, S. Broyles, E. Busch, S. Danna, T. Galati, K. Haye, C. Hayes, M. McGreevy, B. J. Williston, M. Zive, C. Perry, L. Lytle, R. Luepker, B. Davidann, P. Brothen, V. Dahlstrom, M. Dammen, S. Ehlinger, T. Greene, B. Hann, J. Heberle, T. Hoffl ander, C. Kelder, P. Kelliher, T. Kunz, B. Manning, D. McDuffi e, T. Morrow, M. Miller, J. Mrosala, G. Newman, M. Pusateri, M. Reinhardt, R. Sieving, J. Smisson, M. Smyth, P. Snyder, M. Staufacker, J. Traut, T. Wick, G. Parcel, S. Kelder, D. Montgomery, M. Nichaman, W. Taylor, K. Wambsgans Cook, E. Barrera, L. Berry, J. Carbonneau, K. Chemycz, P. Cribb, S. Evans, R. Gordon, J. Gwinn, S. Luton, B. Scaife, S. Sharkey, S. Snider, S. Spigner, K. Wilson, S. Woods, J. Wilmore, L. Webber, C. Johnson, T. Nicklas, V. Anthony, N. Baker, K. Barnwell, S. Belou, G. Berenson, S. Bonura, K. Bordelon, S. Cameron, A. Clesi, L. Crochet, A. Cunningham, D. Franklin, A. Haque, D. Harsha, J. Joy, S. M. Hunter, D. Kuras, P. Lambie, A. Layman, S. Little-Christian, S. Pedersen, J. Reeds-Epping, R. Rice, K. Romero, C. Pitcher-Smith, P. Strikmiller, M. White, S. McKinlay, S. Osganian, H. Feldman, H. Mitchell, S. Budman, P. Connell, M. Koehler, P. Mitchell, C. Kannler, G. Rennie, D. Sellers, M. Walsh, M. Yang, J. Dwyer, M. K. Ebzery, A. Garceau, L. Hewes, C. Hosmer, D. Raizman, L. Bausserman, E. Stone, M. Evans, J. Cutler, R. Lauer, T. Coates, W. Haskell, C. A. Johnson, R. Prineas, L. Van Horn, and J. Verter. 1996. Outcomes of a field trial to improve children’s dietary patterns and physical activity: The child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health. Journal of the American Medical Association 275(10):768-776. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1996.03530340032026

- Mann, M. J., and D. K. Lohrmann. 2019. Addressing challenges to the reliable, large-scale implementation of effective school health education. Health Promotion Practice 20(6):834-844. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919870196.

- Mayer-Davis, E. J., J. M. Lawrence, D. Dabelea, J. Divers, S. Isom, L. Dolan, G. Imperatore, B. Linder, S. Marcovina, D. J. Pettitt, C. Pihoker, and S. Saydah. 2017. Incidence trends of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes among youths, 2002-2012. New England Journal of Medicine 376(15):1419-1429. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1610187.

- Means, R. K. 1975. A History of Health Education. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger.

- Melnyk, B. M., D. Jacobson, S. Kelly, M. Belyea, G. Shaibi, L. Small, J. O’Haver, and F. F. Marsiglia. 2013. Promoting healthy lifestyles in adolescents: A randomized control trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 45(4):407-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.013

- Minnesota Department of Health. Office of Statewide Health Improvement Initiatives. 2012. Statewide Health Improvement Partnership Evaluation Data. Reported by SHIP grantees using the REDCap system.

- Morse L. L. and D. D. Allensworth. 2015. Placing students at the center: The Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child model. Journal of School Health 85:785-794. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12313.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Health and Medicine Division. Roundtable on Health Literacy. Available at: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/PublicHealth/HealthLiteracy.aspx#home (accessed May 3, 2020).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. Developing health literacy skills in youth and young adults. Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Pleasant, A., R. E. Rudd, C. O’Leary, M. K. Paasche-Orlow, M. P. Allen, W. Alvarado-Little, L. Myers, K. Parson, and S. Rosen. 2016. Considerations for a New Definition of Health Literacy. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201604a.

- Rasberry, C. N., G. F. Tiu, L. Kann, T. McManus, S. L. Michael, C. L. Merlo, S. M. Lee, M. K. Bohm, F. Annor, and K. A. Ethier. 2017. Health-related behaviors and academic achievement among high school students—United States, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 66(35):921-927. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6635a1

- Rasberry, C. N., S. Slade, D. K. Lohrmann, and R. F. Valois. 2015. Lessons learned from the Whole Child and Coordinated School Health Approaches. Journal of School Health 85(11):759-765. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12307.

- Ratzan, S. C., and R. M. Parker. 2000. Introduction. In National Library of Medicine current bibliographies in medicine: Health literacy . NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000-1, edited by C. R. Selden, M. Zorn, S. C. Ratzan, and R. M. Parker. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Shattuck, L. 1850. Report of the Sanitary Commission of Massachusetts. Sanitary Commission; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Reprinted from Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1948, p. 178.

- Schillinger, D., J. Tran, and S. Fine. 2018. Do low income youth of color see “The Bigger Picture” when discussing Type 2 diabetes: A qualitative evaluation of a public health literacy campaign. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15(5):840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050840

- Sliepcevich, E. M. 1968. The school health education study: A foundation for community health education. Journal of School Health 38:45-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1968.tb04941.x

- US Department of Agriculture. Food and Nutrition Service. 2020a. National School Lunch program. Available at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/nslp (accessed May 18, 2020).

- US Department of Agriculture. Food and Nutrition Service. 2020b. National Breakfast Program. Starting the school day right with a healthy breakfast. Available at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/sbp/schoolbreakfast-program (accessed May 18, 2020).

- US Department of Education. 2020. The Federal Role in Education. Available at: https://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/fed/role.html (accessed May 18, 2020).

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2010. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. Washington, DC. Available at: https://health.gov/our-work/health-literacy/national-action-planimprove-health-literacy (accessed May 18, 2020).

- US Department of Health, Education, & Welfare. 1979. Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. DHEW (PHS) Publ. No. 79-55071. Washington, DC: Public Health Service.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2010. Healthy People 2020. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/DefaultPressRelease_1.pdf (accessed May 3, 2020).

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2010. Healthy People 2020 Leading Health Indicator Topics: Social Determinants. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-healthindicators/2020-lhi-topics/Social-Determinants (accessed May 3, 2020).

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2017. Secretary’s Advisory Committee Report on Approaches to Healthy People 2030. Healthy People 2030 Draft Framework. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about-healthy-people/development-healthy-people-2030/draft-framework (accessed May 15, 2020).

- Vernon, J. A., A. Trujillo, S. Rosenbaum, and B. De-Buono. 2007. Low health literacy: Implications for national policy. Available at: http://www.gwumc.edu/sphhs/ departments/healthpolicy/chsrp/downloads/LowHealthLiteracyReport10_4_07.pdf (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Videto, D. M. and J. A. Dake. 2019. Promoting health literacy through defining and measuring quality school health education. Health Promotion Practice 20(6):824-833. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919870194.

- Youth Speaks. 2018. The Bigger Picture Toolkit. Available at: http://youthspeaks.org/wp-content/uploads/The%20Bigger%20Picture%20Tool%20Kit.pdf (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Weise, E. and J. Wilson. 2019. “The eyes of future generations are on you,” Thunberg tells UN Climate Summit. USA TODAY. Available at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2019/09/23/howdare-you-look-away-greta-thunberg-tells-un-climate-change-summit/2418058001 (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Winthrop, R. 2020. Covid-19 is a health crisis: So why is health education missing from school work? Available at: https://www.edsurge.com/news/2020-04-03-covid-19-is-a-health-crisis-sowhy-is-health-education-missing-from-schoolwork (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Zimmerman, M. A. 2013. Resiliency theory: A strengths-based approach to research and practice for adolescent health. Health Education & Behavior 40(4):381-383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198113493782

https://doi.org/10.31478/202007b

Suggested Citation

Auld, M. E., M. P. Allen, C. Hampton, J. H. Montes, C. Sherry, A. D. Mickalide, R. Logan, W. Alvarado-Little, and K. Parson. 2020. Health Literacy and Health Education in Schools: Collaboration for Action. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper. National Academy of Medicine. Washington, DC. https//doi.org/10.31478/202007b

Author Information

M. Elaine Auld, MPH, MCHES is Chief Executive Officer, Society for Public Health Education. Marin P. Allen, PhD, is Deputy Associate Director, Office of Communications and Public Liaison and Director of Public Information, Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (retired). Cicily Hampton, PhD, MPA, is Adjunct Assistant Research Professor, University of North Carolina at Charlotte. J. Henry Montes, MPH, is former Chair, Public Health Education and Promotion Section, American Public Health Association. Cherylee Sherry, MPH, MCHES is Healthy Systems Supervisor, Office of Statewide Health Improvement Initiatives, Minnesota Department of Health. Angela D. Mickalide, PhD, MCHES, is Vice President, Programs and Education, American College of Preventive Medicine. Robert A. Logan, PhD, is Senior Staff, U.S. National Library of Medicine (retired) and Professor emeritus, University of Missouri-Columbia. Wilma Alvarado-Little, MA, MSW, is Associate Commissioner, New York State Department of Health and Director, Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities Prevention. Kim Parson, BA, is Principal, KPCG LLC.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our gratitude to Melissa French and Alexis Wojtowicz for their support in the development of this paper.

Conflict-of-Interest Disclosures

Wilma Alvarado-Little has no relevant financial or nonfinancial relationships to disclose. She contributed to this article based on her experience in the field of health literacy and cultural competency and the opinions and conclusions of the article do not represent the official position of the New York State Department of Health. Cherylee Sherry discloses that she works for the Minnesota Department of Health in the Office of Statewide Health Improvement Initiatives which oversees the Statewide Health Improvement Partnership Program funded by the State of Minnesota.

Correspondence

Questions or comments about this manuscript should be directed to M. Elaine Auld at [email protected].

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily of the authors’ organizations, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies). The paper is intended to help inform and stimulate discussion. It is not a report of the NAM or the National Academies. Copyright by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Join Our Community

Sign up for nam email updates.

Texas A&M-McAllen Students Lead Mental Health-Focused Events In Rio Grande Valley Colonias

This spring, Texas A&M University Higher Education Center at McAllen (HECM) Public Health professor Dr. Krystal Flores-Chavez was awarded $5,000 from the HECM’s High Impact Teaching Grant to support a service-learning project for her Project Management in Public Health course.

She separated her students into two groups and awarded each team $2,500 to implement a “real world” project addressing mental health in a colonia in the Rio Grande Valley.

“I really wanted to create a fun, engaging course project where students could work collaboratively with community partners. The course uses high impact teaching methodologies in the form of service – learning pedagogy and collaborative projects. This type of learning is preferred as it provides students with the opportunity to actively apply concepts learned in the classroom to address a community identified need,” Flores-Chavez said. “Mental health was selected as the public health issue students would address based on information provided by focus groups conducted by the Texas A&M University Colonias Program . Their findings reflected residents’ desire for mental health services and increased awareness surrounding the issue.”

The teams collaborated with the Colonias Program and Puentes de Cristo to select the colonia community and launch their respective events. The organizations selected the South Tower Colonias in Alamo, Texas, and the La Piñata colonia in Donna, Texas, as the sites for the team projects.

Clean Environment + Happy, Healthy Minds

In early April, the Donna team invited students of all majors at the HECM to volunteer and help clean a colonia. Students united to help create a cleaner, greener environment by picking up trash, assisting with minor landscaping and distributing freshly potted plants to residents. Each student wore a white shirt with the message: “A clean environment promotes a happy and healthy mind.”

Then last weekend, the Alamo team invited the community to attend a free Mental Health Awareness Fair at the Alamo Community Resource Center and Park for free services from local clinics and non-profit organizations. The students also partnered with Denise Martinez, a doctoral student and community health worker from the Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station to prepare a mental health-themed game of loteria (Bingo) and prizes for participants. The organizations at the community event included Nuestra Clinica Del Valle, South Texas Health Systems Clinics, South Texas Health Systems Behavioral, South Texas Research Institute, HOPE Family Health Center, Mujeres Unidas/Women Together, Puentes De Cristo and the Texas A&M Colonias Program.

Lesly Mata ‘25, one of Flores-Chavez’s students, assisted her team with the planning process and gathering the necessary tools to make the community clean-up a success. “We got to see concepts from the course reflected in real life along the way,” Mata said. “It was a very rewarding and valuable experience helping transform the residents’ neighborhood.”

Adamari De La Cerda ‘25 was also determined to help her team provide valuable mental health resources to colonia residents at the Mental Health Awareness Fair. “My team and I started working with local stakeholders and ultimately decided that hosting a community fair along with a loteria would allow us to personally connect with community members,” said De La Cerda. “We understand how pursuing mental well-being is often stigmatized to be a sign of ‘weakness’ that often forces one to avoid any sort of help. Our goal was to spread awareness about the importance of preserving mental health and destigmatize negative perceptions by personally connecting with community members and offering resources.”

Despite the heavy lifting needed for such projects, it can truly be a fulfilling experience for all involved. “Implementing service learning in courses is often difficult and very time-consuming for both faculty and students. It involves several steps and takes a considerable amount of effort. However, it is incredibly rewarding to be able to witness the growth experienced by students as they navigate the course and challenges associated with developing a ‘real world’ project. Witnessing students gain confidence in their abilities as future public health professionals is one of my favorite aspects of being a professor,” Flores-Chavez said.

Related Stories

Texas A&M AgriLife Turfgrass Program Leads Through Innovation

From backyards to football fields and golf courses, science is reshaping the turfgrass experience.

How To Help Your Cat Breathe Easy With Feline Asthma

Wheezing is often a strong indication of asthma, but there are also other signs that can be used to help make a diagnosis.

Researchers Solve Mystery Of How Phages Disarm Bacteria

New Texas A&M AgriLife research that clarifies how bacteria-infecting viruses disarm pathogens could lead to new treatment methods for bacterial infections.

Recent Stories

Take Control Of Your Money During Financial Literacy Month

An instructor from Texas A&M’s Financial Planning Program says it’s more important than ever for young adults to manage their personal finances wisely. Here’s how.

Former President Of France Speaks At Texas A&M, Honors Bush School Professor

François Hollande delivered a talk on global security and terrorism before presenting Dr. Richard Golsan with one of France’s highest academic honors.

Subscribe to the Texas A&M Today newsletter for the latest news and stories every week.

eHealth Literacy

‹ View Table of Contents

Defining health literacy and eHealth literacy

Assessing health literacy in eHealth studies

Factors associated with use of eHealth

Understanding use of eHealth: Tailoring for success

An important role for health and communication professionals

According to Pew Research Center external icon , approximately 52% of American adults in 2000 said they used the Internet compared to 89% in early 2018; a trend that is likely to continue rising.

Yet individuals are not the only ones using the Internet more. Organizations have also mobilized the Internet to deliver health services. The World Health Organization pdf icon external icon (WHO) reports 58% of Member States surveyed reported they have an eHealth strategy, signaling a global movement. WHO defines electronic health (eHealth) services as the cost-effective and secure use of information communication technologies to support health and health-related fields. Examples include electronic communication between patients and providers, electronic medical records, patient portals, and personal health records. A category of eHealth is mobile health (mHealth) including phones, tablets, and computers to use applications (apps), wearable tracking devices, and texting services. The research referenced on this page may include mHealth when referring to eHealth.

As more people and health organizations use eHealth services and products, we need to understand how a person’s level of health literacy influences the interaction. Equally important is how health professionals and communication specialists can provide support.

In Healthy People 2030, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) updated the definition of health literacy to include personal health literacy as well as organizational health literacy. HHS provides the following definitions:

- Personal health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.

- Organizational health literacy is the degree to which organizations equitably enable individuals to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others

Norman and Skinner (2006) external icon define eHealth literacy as the ability to appraise health information from electronic sources and apply the knowledge gained to addressing or solving a health problem.

Readers are cautioned not to substitute eHealth literacy for health literacy as noted by Monkman and colleagues (2017) external icon . The authors analyzed participant responses (N=36) on the Newest Vital Sign to measure health literacy, and used the eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS) to assess eHealth literacy. Their findings suggest assessing health literacy and eHealth literacy separately.

In 2021, Sanders and colleagues published the results of a randomized controlled trial in which they examined the impact of a six-week, peer-led intervention on eHealth literacy, general health literacy, HIV-related health literacy, and numeracy among people living with HIV (PLWH). The investigators used the Electronic Health Literacy Scale to measure eHealth literacy, the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy to measure general health literacy, the Brief Estimate of Health Knowledge and Action-HIV to measure HIV-related health literacy, and the Newest Vital Sign to measure numeracy. At the end of the intervention and six months later, the intervention group had statistically significant improvements in eHealth literacy and HIV-related health literacy compared to the control group. Neither the control group nor the intervention group showed any statistically significant improvement in general health literacy or numeracy.

(For more on numeracy, see Numeracy Research Summaries and Understanding Literacy & Numeracy . Read more about health literacy and PLWH too.)

As more people and health organizations use eHealth services, we need to understand how a person’s level of health literacy influences the interaction.

Kim & Xie (2017) external icon conducted a literature review (N=74) to assess how people with limited health literacy use online health services. Only nine studies reported interventions focused on improving health literacy. The review indicates that six of those nine reported positive effects on knowledge, skills, and confidence using eHealth. Measures: Thirty-three studies reported measuring participants’ health literacy level. Five studies used the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA) and four studies used the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM). Eight of the 33 studies used the eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS), which as noted previously may not accurately capture health literacy but rather a sub-category—eHealth literacy. Recommendations: When designing websites, the authors suggest improving readability in web-based apps and mobile apps (sixth grade reading level or below), increasing content available for people with limited English proficiency, using plain language strategies such as shorter sentences, use of bullets, and incorporating more consistent design with icons and pictures.