Helen Keller Biography

- Helen Keller Early Childhood

- Meeting Anne Sullivan

- Helen Keller's First Words

- Education and Literary Career

- Political and Social Activism

- Worldwide Celebrity

Where Was Helen Keller Born?

Helen Adams Keller was born a healthy child in Tuscumbia, Alabama, on June 27, 1880. Her parents were Kate Adams Keller and Colonel Arthur Keller .

On her father's side she was descended from Colonel Alexander Spottswood, a colonial governor of Virginia, and on her mother's side, she was related to a number of prominent New England families. Helen's father, Arthur Keller, was a captain in the Confederate army. The family lost most of its wealth during the Civil War and lived modestly.

After the war, Captain Keller edited a local newspaper, the North Alabamian, and in 1885, under the Cleveland administration, he was appointed Marshal of North Alabama.

At the age of 19 months, Helen became deaf and blind as a result of an unknown illness, perhaps rubella or scarlet fever. As Helen grew from infancy into childhood, she became wild and unruly.

When Did Helen Keller Meet Anne Sullivan?

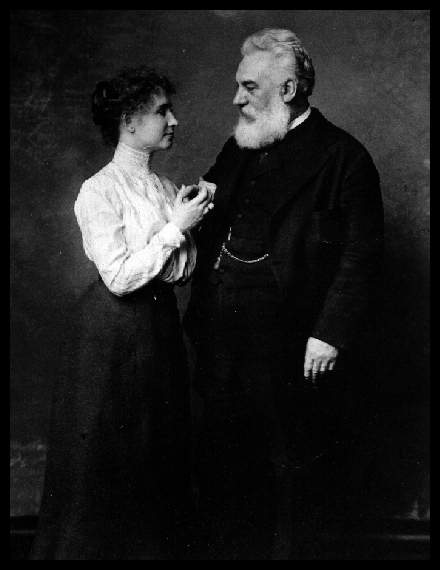

As she so often remarked as an adult, her life changed on March 3, 1887. On that day, Anne Mansfield Sullivan came to Tuscumbia to be her teacher.

She was just 14 years older than her pupil Helen, and she too suffered from serious vision problems. Anne underwent many botched operations at a young age before her sight was partially restored.

Anne's success with Helen remains an extraordinary and remarkable story and is best known to people because of the film The Miracle Worker. The film correctly depicted Helen as an unruly, spoiled—but very bright—child who tyrannized the household with her temper tantrums.

Anne believed that the key to reaching Helen was to teach her obedience and love. She saw the need to discipline, but not crush, the spirit of her young charge. As a result, within a week of her arrival, she had gained permission to remove Helen from the main house and live alone with her in the nearby cottage. They remained there for two weeks.

Anne began her task of teaching Helen by manually signing into the child's hand. Anne had brought a doll that the children at Perkins had made for her to take to Helen. By spelling "d-o-l-l" into the child's hand, she hoped to teach her to connect objects with letters.

Helen quickly learned to form the letters correctly and in the correct order, but did not know she was spelling a word, or even that words existed. In the days that followed, she learned to spell a great many more words in this uncomprehending way.

What Were Helen Keller's First Words?

On April 5, 1887, less than a month after her arrival in Tuscumbia, Anne sought to resolve the confusion her pupil was having between the nouns "mug" and "milk," which Helen confused with the verb "drink."

Anne took Helen to the water pump outside and put Helen's hand under the spout. As the cool water gushed over one hand, she spelled into the other hand the word "w-a-t-e-r" first slowly, then rapidly. Suddenly, the signals had meaning in Helen's mind. She knew that "water" meant the wonderful cool substance flowing over her hand.

Quickly, she stopped and touched the earth and demanded its letter name and by nightfall she had learned 30 words.

Helen quickly proceeded to master the alphabet, both manual and in raised print for blind readers, and gained facility in reading and writing. In Helen's handwriting, many round letters look square, but you can easily read everything.

In 1890, when she was just 10, she expressed a desire to learn to speak; Anne took Helen to see Sarah Fuller at the Horace Mann School for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing in Boston. Fuller gave Helen 11 lessons, after which Anne taught Helen.

Throughout her life, however, Helen remained dissatisfied with her spoken voice, which was hard to understand.

Helen's extraordinary abilities and her teacher's unique skills were noticed by Alexander Graham Bell and Mark Twain, two giants of American culture. Twain declared, "The two most interesting characters of the 19th century are Napoleon and Helen Keller."

The closeness of Helen and Anne's relationship led to accusations that Helen's ideas were not her own. Famously, at the age of 11, Helen was accused of plagiarism. Both Bell and Twain, who were friends and supporters of Helen and Anne, flew to the defense of both pupil and teacher and mocked their detractors. Read a letter from Mark Twain to Helen lamenting "that 'plagiarism' farce."

Helen Keller's Education and Literary Career

From a very young age, Helen was determined to go to college. In 1898, she entered the Cambridge School for Young Ladies to prepare for Radcliffe College. She entered Radcliffe in the fall of 1900 and received a Bachelor of Arts degree cum laude in 1904, the first deafblind person to do so.

The achievement was as much Anne's as it was Helen's. Anne's eyes suffered immensely from reading everything that she then signed into her pupil's hand. Anne continued to labor by her pupil's side until her death in 1936, at which time Polly Thomson took over the task. Polly had joined Helen and Anne in 1914 as a secretary.

While still a student at Radcliffe, Helen began a writing career that was to continue throughout her life. In 1903, her autobiography, The Story of My Life , was published. This had appeared in serial form the previous year in Ladies' Home Journal magazine.

Her autobiography has been translated into 50 languages and remains in print to this day. Helen's other published works include Optimism , an essay; The World I Live In; The Song of the Stone Wall ; Out of the Dark; My Religion; Midstream—My Later Life; Peace at Eventide; Helen Keller in Scotland; Helen Keller's Journal; Let Us Have Faith; Teacher, Anne Sullivan Macy; and The Open Door . In addition, she was a frequent contributor to magazines and newspapers.

The Helen Keller Archives contain over 475 speeches and essays that she wrote on topics such as faith, blindness prevention, birth control, the rise of fascism in Europe, and atomic energy. Helen used a braille typewriter to prepare her manuscripts and then copied them on a regular typewriter.

Helen Keller's Political and Social Activism

Helen saw herself as a writer first—her passport listed her profession as "author." It was through the medium of the typewritten word that Helen communicated with Americans and ultimately with thousands across the globe.

From an early age, she championed the rights of the underdog and used her skills as a writer to speak truth to power. A pacifist, she protested U.S. involvement in World War I. A committed socialist, she took up the cause of workers' rights. She was also a tireless advocate for women's suffrage and an early member of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Helen's ideals found their purest, most lasting expression in her work for the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) . Helen joined AFB in 1924 and worked for the organization for over 40 years.

The foundation provided her with a global platform to advocate for the needs of people with vision loss and she wasted no opportunity. As a result of her travels across the United States, state commissions for the blind were created, rehabilitation centers were built, and education was made accessible to those with vision loss.

Helen's optimism and courage were keenly felt at a personal level on many occasions, but perhaps never more so than during her visits to veteran's hospitals for soldiers returning from duty during World War II.

Helen was very proud of her assistance in the formation in 1946 of a special service for deaf-blind persons. Her message of faith and strength through adversity resonated with those returning from war injured and maimed.

Helen Keller was as interested in the welfare of blind persons in other countries as she was for those in her own country; conditions in poor and war-ravaged nations were of particular concern.

Helen's ability to empathize with the individual citizen in need as well as her ability to work with world leaders to shape global policy on vision loss made her a supremely effective ambassador for disabled persons worldwide. Her active participation in this area began as early as 1915, when the Permanent Blind War Relief Fund, later called the American Braille Press, was founded. She was a member of its first board of directors.

In 1946, when the American Braille Press became the American Foundation for Overseas Blind (now Helen Keller International), Helen was appointed counselor on international relations. It was then that she began her globe-circling tours on behalf of those with vision loss.

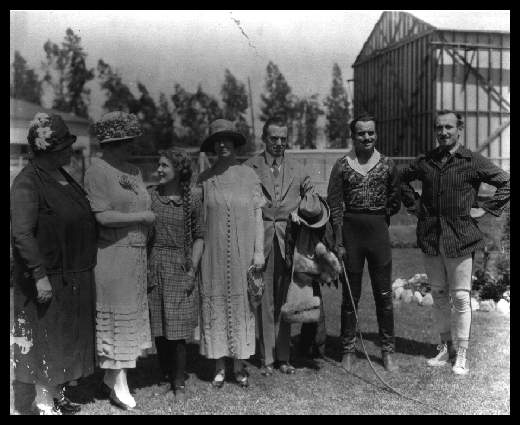

Helen Keller's Worldwide Celebrity

During seven trips between 1946 and 1957, she visited 35 countries on five continents. She met with world leaders such as Winston Churchill, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Golda Meir.

In 1948, she was sent to Japan as America's first Goodwill Ambassador by General Douglas MacArthur. Her visit was a huge success; up to two million Japanese came out to see her and her appearance drew considerable attention to the plight of Japan's blind and disabled population.

In 1955, when she was 75 years old, she embarked on one of her longest and most grueling journeys: a 40,000-mile, five-month-long tour through Asia.

Wherever she traveled, she brought encouragement to millions of blind people, and many of the efforts to improve conditions for those with vision loss outside the United States can be traced directly to her visits.

Helen was famous from the age of 8 until her death in 1968. Her wide range of political, cultural, and intellectual interests and activities ensured that she knew people in all spheres of life.

She counted leading personalities of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries among her friends and acquaintances. These included Eleanor Roosevelt, Will Rogers, Albert Einstein, Emma Goldman, Eugene Debs, Charlie Chaplin, John F. Kennedy, Andrew Carnegie, Henry Ford, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Katharine Cornell, and Jo Davidson to name but a few.

She was honored around the globe and garnered many awards. She received honorary doctoral degrees from Temple and Harvard Universities in the United States; Glasgow and Berlin Universities in Europe; Delhi University in India; and Witwatersrand University in South Africa. She also received an honorary Academy Award in 1955 as the inspiration for the documentary about her life, Helen Keller in Her Story.

Helen Keller's Later Life

Helen suffered a stroke in 1960, and from 1961 onwards, she lived quietly at Arcan Ridge, her home in Westport, Connecticut, one of the four main places she lived during her lifetime. (The others were Tuscumbia, Alabama; Wrentham, Massachusetts; and Forest Hills, New York).

She made her last major public appearance in 1961 at a Washington, D.C., Lions Clubs International Foundation meeting. At that meeting, she received the Lions Humanitarian Award for her lifetime of service to humanity and for providing the inspiration for the adoption by Lions Clubs International Foundation of their sight conservation and aid to blind programs.

During that visit to Washington, she also called on President John F. Kennedy at the White House. President Kennedy was just one in a long line of presidents Helen had met. In her lifetime, she had met all of the presidents since Grover Cleveland.

Helen Keller died on June 1, 1968, at Arcan Ridge, a few weeks short of her 88th birthday. Her ashes were placed next to her companions, Anne Sullivan Macy and Polly Thomson, in St. Joseph's Chapel of Washington Cathedral.

Senator Lister Hill of Alabama gave a eulogy during the public memorial service. He said, "She will live on, one of the few, the immortal names not born to die. Her spirit will endure as long as man can read and stories can be told of the woman who showed the world there are no boundaries to courage and faith."

IMAGES

VIDEO