Learn Japanese online

How to write sakubun.

Sakubun – writing (a paragraph, an essay, etc.), is an important part of teaching and learning Japanese. So Sakubun is considered a skill that is not easy to acquire for Japanese learners. In this post, Learn Japanese Daily will introduce to you the lesson: How to write Sakubun. Let’s start!

- 1.1 Sakubun meaning

- 1.2.1 How to write the title of Sakubun, your full name, school and class

- 1.2.2 The content of Sakubun

- 1.3 Japanese essay format

How to write Sakubun in Japanese

Sakubun meaning.

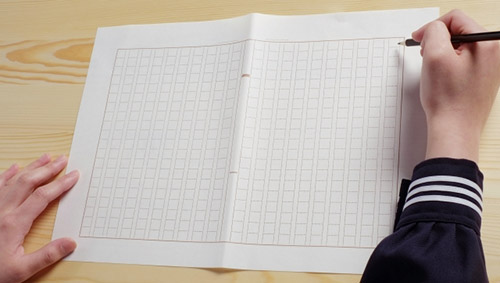

Sakubun (作文) is writing a paragraph, an essay, etc. in Japanese. When writing Sakubun, Japanese people will use a special type of paper called 原稿用紙 (Genkou youshi). This type of paper is divided into small squares for the sake of writing Sakubun easily. Genkou youshi is usually sold at 100 yen stores or at stationery stores in the schools.

How to use Genkou youshi (Japanese writing paper)

The most common 原稿用紙 (Genkou youshi) is the paper consisting of 20 lines on one side of that paper, and each line has 20 squares. So the total number of squares is 400.

There are rules when using Genkou youshi that writers need to know. The most basic way to use is to rotate the paper horizontally and write vertically from right to left. However, there are some Japanese language schools that allow students to to rotate the paper vertically and write horizontally from left to right. This post will guide you the first way (rotating the paper horizontally and writing vertically from right to left).

How to write the title of Sakubun, your full name, school and class

Before writing the content of Sakubun, you need to write your full name, your class and the title of Sakubun first.

Title: Write in the first line. Leave the first two or three squares blank (from top to bottom).

Full name: Write in the last squares in the second line, but you must leave the last square blank. There is one square between first name and last name.

School and class: It may or may not be written depending on the requirement. If you have to write, write in the second line (above the full name and there is one square between school – class and full name).

The content of Sakubun

– Leave the first square blank and start writing from the second square. When moving to the next paragraph, you also need to leave the first square blank and start writing from the second square.

– Commas, dots, question marks, exclamation points, and quotation marks are like a letter, so each of them is written in a single square. However, when these marks may appear at the beginning of a new line, you need to write them in the same square with the letter immediately preceding them in the old line (or write them in the margin at the bottom of the old line), in order to avoid these marks start a new line.

– For conversation sentences, dots and quotation marks are written in the same square. If the sentence is needed to be written in 2 or more lines, leave the first square blank and then write from the second square.

– Small letters such as っ、ゃ、ゅ、ょ are also written in a single square.

– The digits must be written in Kanji: 一, 二, 三, 万 v…v….

– If you need to write the numbers (0,1,2, etc.), write two numbers horizontally in the same square.

– With Alphabet letters, two lowercase letters can be written horizontally in the same square, and each capital letter can be written vertically in a single square.

Japanese essay format

You can write Sakubun according to the 4-part structure 起承転結, including: 起 – introduction, 承 – development, 転 – turn, 結 – conclusion.

Or you can write Sakubun according to the 3-part structure – 三段構成 (Sandan kousei), including: 序 – opening, 破 – body, 急 – conclusion.

To understand more about the way of writing as well as the structure of Sakubun, you can refer to some samples of Sakubun on different topics at category : Japanese essay .

Above is: How to write Sakubun. Hope this post can help you improve your writing skills. Wish you all good study!

Stay with us on :

- Japanese vocabulary on mathematics- math in japanese

- Chemistry terms in Japanese

You May Also Like

Write a paragraph about family in Japanese

Write a paragraph about Japan

Composition about friends in Japanese

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Apply the Essay Structure to Your Japanese Script

Introduction

*The target readers are those who will make a speech or presentation in Japanese.

Needless to say, “Introduction-Body-Conclusion” is one of the most well known methods for making essays and scripts in the world. One of its strengths is that you are able to logically express what you want to convey to your audience. However, this method is not actually that well known among Japanese people in comparison to other countries. In this article, you will learn how you can utilize the Introduction-Body-Conclusion structure for your Japanese script.

Introduction-Body-Conclusion for Your Japanese Script

Introduction part.

In this part, you are going to, quite literally, set up an introduction. Simply speaking, if you mention the following three points, you will cover the basics; what your topic is, why your audience is listening to you, and what you want your audience to do or feel throughout your script. In practice, it is better to get the audience’s attention by using interesting facts or information, or by asking a question.

今日 きょう は 私 わたし の 夢 ゆめ についてお 話 はな します。

I am going to talk about my dream today.

私 わたし の 夢 ゆめ は、 私 わたし の 地 じ 元 もと を 復興 ふっこう することです。

My dream is to revive my hometown.

私 わたし の 町 まち の 人口 じんこう はたった 2 に 万人 まんにん です。ですが、 高齢者 こうれいしゃ は 1万人 いちまんにん 以 い 上 じょう います。

The population of my hometown is just 20,000. However, the number of the elderly is over 10,000.

そして、さらにこの 高齢化 こうれいしゃ は 進 すす んでいくと 言 い われています。

And, it is said that this aging population will continue to grow.

今日 きょう の 私 わたし のスピーチで、 私 わたし たちを 応援 おうえん してくれる 人 ひと が 増 ふ えると 嬉 うれ しいです。

I will be happy if my speech today could increase the number of people who support us.

In this part, you are going to prove how your aim, argument and conclusion are reasonable by showing the evidence, the statistics, the analysis, etc. You should explain that objectively, not subjectively, because in the introduction and the conclusion you will share your own ideas and opinions. Also, you should order the information from the most general to the most specific.

日 に 本 ほん の 現在 げんざい の 人口 じんこう は 1億 いちおく 2 に 千万人 せんまんにん です。これが 1億人 いちおくにん まで 減 へ ります。

The current population of Japan is 120 million and it appears that it will continue to decrease to 100 million.

しかし、 日 に 本 ほん でも 人口 じんこう が 増 ふ え 続 つづ ける 都市 とし があります。それは 東京 とうきょう です。

However, there is a city whose population is increasing. That’s Tokyo.

日 に 本 ほん は 豊 ゆた かな 都市 とし と 貧 まず しい 町 まち に 別 わか れていきます。

Japan will be divided into one rich city and other poor towns.

若 わか い 人 ひと は 東京 とうきょう にどんどん 移 い 動 どう しています。

Younger people are moving to Tokyo.

ですが、 年配者 ねんぱいしゃ はそう 簡単 かんたん には 住 す む 場 ば 所 しょ を 変 か えられません。

Yet, the elderly cannot move as easily around a big city as younger people do.

多 た 少 しょう の 費 ひ 用 よう がかかりますが、 国 くに として 貧 まず しい 町 まち を 支 ささ えるか、 移 い 住 じゅう のサポートをする 必要 ひつよう があります。

Although it may cost them, the government has to help maintain the poor towns or support the elderly in moving somewhere else.

ただ、もしその 街 まち がもう 一 いち 度 ど 元 げん 気 き になれば、 全 すべ ての 問題 もんだい は 解決 かいけつ するでしょう。

If those towns were revived, all problems would be solved.

Conclusion Part

In this part, you are going to wrap up what you have been discussing and make your conclusion. That is to say, you are going to mention your topic, the background, and the reason why it is important again, which should be worded a little bit differently than earlier on in your speech, and then call for action or make your commitment for the future.

繰 く り 返 かえ しですが、 私 わたし の 夢 ゆめ は 地 じ 元 もと を 復興 ふっこう することです。

Again, my dream is to revive my hometown.

これは 私 わたし たちだけの 問題 もんだい ではありません。

This is not only a problem for us.

私 わたし の 町 まち が 元 げん 気 き になることは 他 ほか の 町 まち を 大 おお きく 勇 ゆう 気 き づけるはずです。

If my hometown is revived, it must also really inspire other towns

だから 私 わたし たちに 皆 みな さんの 力 ちから を 貸 か してください。

Thus, please give us a helping hand

皆 みな さんが 私 わたし の 町 まち に 観光 かんこう に 来 き てくれるだけで 状況 じょうきょう は 大 おお きく 変 か わります。

Even if you just go sightseeing in my hometown, it will make significant changes.

どうぞよろしくお 願 ねが いします。ありがとうございました。

Pros and Cons

The Introduction-Body-Conclusion structure is appropriate for explaining something and persuading someone to do something because of its logical structure. Thus, it is almost always used in academic and business situations. On the other hand, it is not appropriate for really making people think or playing to their feelings. If a person tries to use this approach for those purposes, it will not be as effective.

In regards to using this method for making a Japanese script for your speech, it is recommended that you use it only when your proposition has certain social values or factors to arouse sympathy. If not, you may look selfish because the Introduction-Body-Conclusion structure will work only for proving why you are right. On the other hand, people like to use it because its familiar to them. In that case, please try to put some humor into your Japanese script. That way, your audience will be engaged with a smile.

Recommended Link

Enhance Your Japanese Script: Ki-Sho-Ten-Ketsu Structure

Distinguish Your Japanese Script: Jyo-Ha-Kyu Structure

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- Privacy Policy

Transition Words and Phrases for Japanese Essays

June 9, 2020

By Alexis Papa

Are you having a hard time connecting between your ideas in your Japanese essay? In this article, we have listed useful transition words and phrases that you can use to help you let your ideas flow and have an organized essay.

Japanese Phrases for Giving Examples and Emphasis

For example,

がいこく、たとえばちゅうごくへいったことがありますか。 Gaikoku, tatoeba Chuugoku e itta koto ga arimasu ka?

Have you been abroad, for instance China?

たぶんちゅうごくへいったことがあります。 Tabun Chuugoku e itta koto ga arimasu.

I have probably been to China.

Japanese Essay Phrases: General Explaining

しけんにごうかくするのために、まじめにべんきょうしなきゃ。 Shiken ni goukaku suru no tame ni, majime ni benkyou shinakya.

In order to pass the exam, I must study.

あしたあめがふるそう。だから、かさをもってきて。 Ashita ame ga furu sou. Dakara, kasa wo motte kite.

It seems that it will rain tomorrow. So, bring an umbrella.

Showing Sequence

まず、あたらしいさくぶんのがいせつをしようとおもう。 Mazu, atarashii sakubun no gaisetsu wo shiyou to omou.

First, I am going to do an outline of my new essay.

つぎに、さくぶんをかきはじめます。 Tsugi ni, sakubun wo kaki hajimemasu.

Then, I will begin writing my essay.

Adding Supporting Statements

かれはブレーキをかけ、そしてくるまはとまった。 Kare wa bureki wo kake, soshite kuruma wa tomatta.

He put on the brakes and then the car stopped.

いえはかなりにみえたし、しかもねだんがてごろだった。 Ie wa kanari ni mieta shi, shikamo nedan ga tegoro datta.

The house looked good; moreover,the (selling) price was right.

Demonstrating Contrast

にほんごはむずかしいですが、おもしろいです。 Nihongo wa muzukashii desu ga, omoshiroi desu.

Although Japanese language is difficult, it is enjoyable.

にほんごはむずかしいです。でも、おもしろいです。 Nihongo wa muzukashii desu. Demo, omoshiroi desu.

Japanese language is difficult. Nevertheless, it is enjoyable.

にほんごはむずかしいです。しかし、おもしろいです。 Nihondo wa muzukashii desu. Shikashi, omoshiroi desu.

Japanese language is difficult. However, it is enjoyable.

にほんごはむずかしいですけれど、おもしろいです。 Nihongo wa muzakashii desu keredo, omoshiroi desu.

Japanese Essay Phrases for Summarizing

われわれはこのはなしはじつわだというけつろんにたっした。 Wareware wa kono hanashi wa jitsuwa da to iu ketsuron ni tasshita.

We have come to a conclusion that this is a true story.

Now that you have learned these Japanese transitional words and phrases, we hope that your Japanese essay writing has become easier. Leave a comment and write examples of sentences using these Japanese essay phrases!

Alexis Papa

Alexis is a Japanese language and culture enthusiast from the Philippines. She is a Japanese Studies graduate, and has worked as an ESL and Japanese instructor at a local language school. She enjoys her free time reading books and watching series.

Your Signature

Subscribe to our newsletter now!

LEARN JAPANESE WITH MY FREE LEARNING PACKAGE

- 300 Useful Japanese Adjectives E-book

- 100 Days of Japanese Words and Expressions E-book

Sign up below and get instant access to the free package!

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

StoryLearning

Learn A Language Through Stories

How To Write In Japanese – A Beginner’s Guide

Do you want to learn how to write in Japanese , but feel confused or intimidated by the script?

This post will break it all down for you, in a step-by-step guide to reading and writing skills this beautiful language.

I remember when I first started learning Japanese and how daunting the writing system seemed. I even wondered whether I could get away without learning the script altogether and just sticking with romaji (writing Japanese with the roman letters).

I’m glad I didn’t.

If you’re serious about learning Japanese, you have to get to grips with the script sooner or later. If you don’t, you won’t be able to read or write anything useful, and that’s no way to learn a language.

The good news is that it isn’t as hard as you think. And I’ve teamed up with my friend Luca Toma (who’s also a Japanese coach ) to bring you this comprehensive guide to reading and writing Japanese.

By the way, if you want to learn Japanese fast and have fun while doing it, my top recommendation is Japanese Uncovered which teaches you through StoryLearning®.

With Japanese Uncovered you’ll use my unique StoryLearning® method to learn Japanese naturally through story… not rules. It’s as fun as it is effective.

If you’re ready to get started, click here for a 7-day FREE trial.

If you have a friend who’s learning Japanese, you might like to share it with them. Now, let’s get stuck in…

One Language, Two Systems, Three Scripts

If you are a complete beginner, Japanese writing may appear just like Chinese.

But if you look at it more carefully you'll notice that it doesn’t just contain complex Chinese characters… there are lots of simpler ones too.

Take a look.

それでも、 日本人 の 食生活 も 急速 に 変化 してきています 。 ハンバーグ や カレーライス は 子供に人気 がありますし 、都会 では 、 イタリア 料理、東南 アジア 料理、多国籍料理 などを 出 す エスニック 料理店 がどんどん 増 えています 。

Nevertheless, the eating habits of Japanese people are also rapid ly chang ing . Hamburgers and curry rice are popular with children . In cities , ethnic restaurants serv ing Italian cuisine , Southeast Asian cuisine and multi-national cuisine keep increas ing more and more .

(Source: “Japan: Then and Now”, 2001, p. 62-63)

As you can see from this sample, within one Japanese text there are actually three different scripts intertwined. We’ve colour coded them to help you tell them apart.

(What’s really interesting is the different types of words – parts of speech – represented by each colour – it tells you a lot about what you use each of the three scripts for.)

Can you see the contrast between complex characters (orange) and simpler ones (blue and green)?

The complex characters are called kanji (漢字 lit. Chinese characters) and were borrowed from Chinese. They are what’s called a ‘logographic system' in which each symbol corresponds to a block of meaning (食 ‘to eat', 南 ‘south', 国 ‘country').

Each kanji also has its own pronunciation, which has to be learnt – you can’t “read” an unknown kanji like you could an unknown word in English.

Luckily, the other two sets of characters are simpler!

Those in blue above are called hiragana and those in green are called katakana . Katakana and hiragana are both examples of ‘syllabic systems', and unlike the kanji , each character corresponds to single sound. For example, そ= so, れ= re; イ= i, タ = ta.

Hiragana and katakana are a godsend for Japanese learners because the pronunciation isn’t a problem. If you see it, you can say it!

So, at this point, you’re probably wondering:

“What’s the point of using three different types of script? How could that have come about?”

In fact, all these scripts have a very specific role to play in a piece of Japanese writing, and you’ll find that they all work together in harmony in representing the Japanese language in a written form.

So let’s check them out in more detail.

First up, the two syllabic systems: hiragana and katakana (known collectively as kana ).

The ‘Kana' – One Symbol, One Sound

Both hiragana and katakana have a fixed number of symbols: 46 characters in each, to be precise.

Each of these corresponds to a combination of the 5 Japanese vowels (a, i, u, e o) and the 9 consonants (k, s, t, n, h, m, y, r, w).

(Source: Wikipedia Commons )

Hiragana (the blue characters in our sample text) are recognizable for their roundish shape and you’ll find them being used for three functions in Japanese writing:

1. Particles (used to indicate the grammatical function of a word)

は wa topic marker

が ga subject marker

を wo direct object marker

2. To change the meaning of verbs, adverbs or adjectives, which generally have a root written in kanji. (“Inflectional endings”)

急速 に kyuusoku ni rapid ly

増 えています fu ete imasu are increas ing

3. Native Japanese words not covered by the other two scripts

それでも soredemo nevertheless

どんどん dondon more and more

Katakana (the green characters in our sample text) are recognisable for their straight lines and sharp corners. They are generally reserved for:

1. Loanwords from other languages. See what you can spot!

ハンバーグ hanbaagu hamburger

カレーライス karee raisu curry rice

エスニック esunikku ethnic

2. Transcribing foreign names

イタリア itaria Italy

アジア ajia Asia

They are also used for emphasis (the equivalent of italics or underlining in English), and for scientific terms (plants, animals, minerals, etc.).

So where did hiragana and katakana come from?

In fact, they were both derived from kanji which had a particular pronunciation; Hiragana took from the Chinese cursive script (安 an →あ a), whereas katakana developed from single components of the regular Chinese script (阿 a →ア a ).

So that covers the origins the two kana scripts in Japanese, and how we use them.

Now let’s get on to the fun stuff… kanji !

The Kanji – One Symbol, One Meaning

Kanji – the most formidable hurdle for learners of Japanese!

We said earlier that kanji is a logographic system, in which each symbol corresponds to a “block of meaning”.

食 eating

生 life, birth

活 vivid, lively

“Block of meaning” is the best phrase, because one kanji is not necessarily a “word” on its own.

You might have to combine one kanji with another in order to make an actual word, and also to express more complex concepts:

生 + 活 = 生活 lifestyle

食 + 生活 = 食生活 eating habits

If that sounds complicated, remember that you see the same principle in other languages.

Think about the word ‘telephone' in English – you can break it down into two main components derived from Greek:

‘tele' (far) + ‘phone' (sound) = telephone

Neither of them are words in their own right.

So there are lots and lots of kanji , but in order to make more sense of them we can start by categorising them.

There are several categories of kanji , starting with the ‘pictographs' (象形文字 sh ōkei moji), which look like the objects they represent:

(Source: Wikipedia Commons )

In fact, there aren’t too many of these pictographs.

Around 90% of the kanji in fact come from six other categories, in which several basic elements (called ‘radicals') are combined to form new concepts.

For example:

人 (‘man' as a radical) + 木 (‘tree') = 休 (‘to rest')

These are known as 形声文字 keisei moji or ‘radical-phonetic compounds'.

You can think of these characters as being made up of two parts:

- A radical that tells you what category of word it is: animals, plants, metals, etc.)

- A second component that completes the character and give it its pronunciation (a sort of Japanese approximation from Chinese).

So that’s the story behind the kanji , but what are they used for in Japanese writing?

Typically, they are used to represent concrete concepts.

When you look at a piece of Japanese writing, you’ll see kanji being used for nouns, and in the stem of verbs, adjectives and adverbs.

Here are some of them from our sample text at the start of the article:

日本人 Japanese people 多国籍料理 multinational cuisine 東南 Southeast

Now, here’s the big question!

Once you’ve learnt to read or write a kanji , how do you pronounce it?

If you took the character from the original Chinese, it would usually only have one pronunciation.

However, by the time these characters leave China and reach Japan, they usually have two or sometimes even more pronunciations.

How or why does this happen?

Let's look at an example.

To say ‘mountain', the Chinese use the pictograph 山 which depicts a mountain with three peaks. The pronunciation of this character in Chinese is sh ā n (in the first tone).

Now, in Japanese the word for ‘mountain' is ‘yama'.

So in this case, the Japanese decided to borrow the character山from Chinese, but to pronounce it differently: yama .

However, this isn’t the end of the story!

The Japanese did decide to borrow the pronunciation from the original Chinese, but only to use it when that character is used in compound words.

So, in this case, when the character 山 is part of a compound word, it is pronounced as san/zan – clearly an approximation to the original Chinese pronunciation.

Here’s the kanji on its own:

山は… Yama wa… The mountain….

And here’s the kanji when it appears in compound words:

火山は… Ka zan wa The volcano…

富士山は… Fuji san wa… Mount Fuji….

To recap, every kanji has at least two pronunciations.

The first one (the so-called訓読み kun'yomi or ‘meaning reading') has an original Japanese pronunciation, and is used with one kanji on it’s own.

The second one (called音読み on'yomi or ‘sound-based reading') is used in compound words, and comes from the original Chinese.

Makes sense, right? 😉

In Japan, there’s an official number of kanji that are classified for “daily use” (常用漢字 joy ō kanji ) by the Japanese Ministry of Education – currently 2,136.

(Although remember that the number of actual words that you can form using these characters is much higher.)

So now… if you wanted to actually learn all these kanji , how should you go about it?

To answer this question, Luca’s going to give us an insight into how he did it.

How I Learnt Kanji

I started to learn kanji more than 10 years ago at a time when you couldn't find all the great resources that are available nowadays. I only had paper kanji dictionary and simple lists from my textbook.

What I did have, however, was the memory of a fantastic teacher.

I studied Chinese for two years in college, and this teacher taught us characters in two helpful ways:

- He would analyse them in terms of their radicals and other components

- He kept us motivated and interested in the process by using fascinating stories based on etymology (the origin of the characters)

Once I’d learnt to recognise the 214 radicals which make up all characters – the building blocks of Chinese characters – it was then much easier to go on and learn the characters and the words themselves.

It’s back to the earlier analogy of dividing the word ‘telephone' into tele and phone .

But here’s the thing – knowing the characters alone isn’t enough. There are too many, and they’re all very similar to one another.

If you want to get really good at the language, and really know how to read and how to write in Japanese, you need a higher-order strategy.

The number one strategy that I used to reach a near-native ability in reading and writing in Japanese was to learn the kanji within the context of dialogues or other texts .

I never studied them as individual characters or words.

Now, I could give you a few dozen ninja tricks for how to learn Japanese kanji. B ut the one secret that blows everything else out of the water and guarantees real success in the long-term, is extensive reading and massive exposure.

This is the foundation of the StoryLearning® method , where you immerse yourself in language through story.

In the meantime, there are a lot of resources both online and offline to learn kanji , each of which is based on a particular method or approach (from flashcards to mnemonic and so on).

The decision of which approach to use can be made easier by understanding the way you learn best.

Do you have a photographic memory or prefer working with images? Do you prefer to listen to audio? Or perhaps you prefer to write things by hands?

You can and should try more than one method, in order to figure out which works best for you.

( Note : You should get a copy of this excellent guide by John Fotheringham, which has all the resources you’ll ever need to learn kanji )

Summary Of How To Write In Japanese

So you’ve made it to the end!

See – I told you it wasn’t that bad! Let’s recap what we’ve covered.

Ordinary written Japanese employs a mixture of three scripts:

- Kanji, or Chinese characters, of which there are officially 2,136 in daily use (more in practice)

- 2 syllabic alphabets called hiragana and katakana, containing 42 symbols each

In special cases, such as children’s books or simplified materials for language learners, you might find everything written using only hiragana or katakana .

But apart from those materials, everything in Japanese is written by employing the three scripts together. And it’s the kanji which represent the cultural and linguistic challenge in the Japanese language.

If you want to become proficient in Japanese you have to learn all three!

Although it seems like a daunting task, remember that there are many people before you who have found themselves right at the beginning of their journey in learning Japanese.

And every journey begins with a single step.

So what are you waiting for?

The best place to start is to enrol in Japanese Uncovered . The course includes a series of lessons that teach you hiragana, katakana and kanji. It also includes an exciting Japanese story which comes in different formats (romaji, hiragana, kana and kanji) so you can practice reading Japanese, no matter what level you're at right now.

– – –

It’s been a pleasure for me to work on this article with Luca Toma, and I’ve learnt a lot in the process.

Now he didn’t ask me to write this, but if you’re serious about learning Japanese, you should consider hiring Luca as a coach. The reasons are many, and you can find out more on his website: JapaneseCoaching.it

Do you know anyone learning Japanese? Why not send them this article, or click here to send a tweet .

Language Courses

- Language Blog

- Testimonials

- Meet Our Team

- Media & Press

Download this article as a FREE PDF ?

What is your current level in Swedish?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Swedish tips…

Where shall I send the tips and your PDF?

We will protect your data in accordance with our data policy.

What is your current level in Danish?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Danish tips…

NOT INTERESTED?

What can we do better? If I could make something to help you right now, w hat would it be?

Which language are you learning?

What is your current level in [language] ?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] [language] tips, PLUS your free StoryLearning Kit…

Where shall I send them?

Download this article as a FREE PDF?

Great! Where shall I send my best online teaching tips and your PDF?

Download this article as a FREE PDF ?

What is your current level in Arabic?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Arabic tips…

FREE StoryLearning Kit!

Join my email newsletter and get FREE access to your StoryLearning Kit — discover how to learn languages through the power of story!

Download a FREE Story in Japanese!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Japanese and start learning Japanese quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

What is your current level in Japanese?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Japanese StoryLearning® Pack …

Where shall I send your download link?

Download Your FREE Natural Japanese Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Japanese Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Japanese grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Japanese Grammar Pack …

What is your current level in Portuguese?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Portuguese Grammar Pack …

What is your current level in German?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural German Grammar Pack …

Train as an Online Language Teacher and Earn from Home

The next cohort of my Certificate of Online Language Teaching will open soon. Join the waiting list, and we’ll notify you as soon as enrolment is open!

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Portuguese tips…

What is your current level in Turkish?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Turkish tips…

What is your current level in French?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the French Vocab Power Pack …

What is your current level in Italian?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Italian Vocab Power Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the German Vocab Power Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Japanese Vocab Power Pack …

Download Your FREE Japanese Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Japanese Vocab Power Pack and learn essential Japanese words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Download Your FREE German Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my German Vocab Power Pack and learn essential German words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Download Your FREE Italian Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Italian Vocab Power Pack and learn essential Italian words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Download Your FREE French Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my French Vocab Power Pack and learn essential French words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Portuguese StoryLearning® Pack …

What is your current level in Russian?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Russian Grammar Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Russian StoryLearning® Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Italian StoryLearning® Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Italian Grammar Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the French StoryLearning® Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural French Grammar Pack …

What is your current level in Spanish?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Spanish Vocab Power Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Spanish Grammar Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Spanish StoryLearning® Pack …

Where shall I send them?

What is your current level in Korean?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Korean tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Russian tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Japanese tips…

What is your current level in Chinese?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Chinese tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Spanish tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Italian tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] French tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] German tips…

Download Your FREE Natural Portuguese Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Portuguese Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Portuguese grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download Your FREE Natural Russian Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Russian Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Russian grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download Your FREE Natural German Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural German Grammar Pack and learn to internalise German grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download Your FREE Natural French Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural French Grammar Pack and learn to internalise French grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download Your FREE Natural Italian Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Italian Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Italian grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download a FREE Story in Portuguese!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Brazilian Portuguese and start learning Portuguese quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Download a FREE Story in Russian!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Russian and start learning Russian quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Download a FREE Story in German!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in German and start learning German quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the German StoryLearning® Pack …

Download a FREE Story in Italian!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Italian and start learning Italian quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Download a FREE Story in French!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in French and start learning French quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Download a FREE Story in Spanish!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Spanish and start learning Spanish quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

FREE Download:

The rules of language learning.

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Rules of Language Learning and discover 25 “rules” to learn a new language quickly and naturally through stories.

What can we do better ? If I could make something to help you right now, w hat would it be?

What is your current level in [language]?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] [language] tips…

Download Your FREE Spanish Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Spanish Vocab Power Pack and learn essential Spanish words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Download Your FREE Natural Spanish Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Spanish Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Spanish grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Free Step-By-Step Guide:

How to generate a full-time income from home with your English… even with ZERO previous teaching experience.

What is your current level in Thai?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Thai tips…

What is your current level in Cantonese?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Cantonese tips…

Steal My Method?

I’ve written some simple emails explaining the techniques I’ve used to learn 8 languages…

I want to be skipped!

I’m the lead capture, man!

Join 84,574 other language learners getting StoryLearning tips by email…

“After I started to use your ideas, I learn better, for longer, with more passion. Thanks for the life-change!” – Dallas Nesbit

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] [language] tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] [language] tips…

Join 122,238 other language learners getting StoryLearning tips by email…

Find the perfect language course for you.

Looking for world-class training material to help you make a breakthrough in your language learning?

Click ‘start now’ and complete this short survey to find the perfect course for you!

Do you like the idea of learning through story?

Do you want…?

- KU Libraries

- Subject & Course Guides

- Resource Guide for Japanese Language Students

Resource Guide for Japanese Language Students: Essays

- Short Stories

- Translated Foreign Literature

- Japanese and English

- Comics with Furigana

- Comics with no Furigana

- Picture Books

- Online Reading Materials

- Apps, Sites, Extensions, and Podcasts

- For Listening Practice: Read Aloud Picture Books

- For Listening Practice: Children's Literature

- For Listening Practice: Young Adults

- Japanese-Language Proficiency Test (JLPT)

- Japanese Research & Bibliographic Methods for Undergraduates

- Japan Studies This link opens in a new window

- Guidebooks for Academic and Business Writing

About This Page

This page introduces the variety of essays written by popular contemporary authors. Unless noted, all are in Japanese.

The author, さくらももこ, is known for writing a comic titled 『 ちびまる子ちゃん 』. The comic is based on her own childhood experiences and depicts the everyday life of a girl with a nickname of Chibi Maruko-chan. The author has been constantly writing casual and humorous essays, often recollecting her childhood memories. We have both the『 ちびまる子ちゃん 』 comic series and other essays by the author.

To see a sample text in a new tab, please click on the cover image or the title .

中島らも(1952-2004) started his career as a copyrigher but changed his path to become a prolific writer, publishing novels, essays, drama scripts and rakugo stories. He became popular with his "twisted sense of humour." He is also active in the music industry when he formed his own band. He received the 13th Eiji Yoshikawa New Author Prize with his 『今夜、すべてのバーで』 and Mystery Writers of Japan Aaward with 『 ガダラの豚 』.

東海林(しょうじ)さだお

東海林さだお(1937-) is a well-known cartoonist, but he is also famous for his essays on food. His writing style is light and humorous and tends to pay particular attention toward regular food, such as bananas, miso soup, and eggd in udon noodles, rather than talk about gourmet meals. (added 5/2/2014)

Collection of Essays: 天声人語 = Vox Populi, Vox Deli (Bilingual)

A collection of essays which appear on the front page of Asahi Shinbun . Each essay is approx. 600 words. KU has collections published around 2000. Seach KU Online catalog with call number AC145 .T46 for more details.

To see a sample text, please click on the cover image or the title .

Other Essays

Online Essay

- 村上さんのところ "Mr. Murakami's Place" -- Haruki Murakami's Advice Column Part of Haruki Murakami's official site. He answers questions sent to this site. He will also take questions in English. Questions will be accepted until Jan. 31, 2015.

Search from KU Collection

If you are looking for essays in Japanese available at KU, use this search box. If you know the author, search by last name, then first name, such as "Sakura, Momoko." Make sure to select "Author" in the search field option.:

- << Previous: Level 4

- Next: Short Stories >>

- Last Updated: Feb 1, 2024 11:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.ku.edu/c.php?g=95189

Unconventional language hacking tips from Benny the Irish polyglot; travelling the world to learn languages to fluency and beyond!

Looking for something? Use the search field below.

Home » Articles » How to Write in Japanese — A Beginner’s Guide to Japanese Writing

Full disclosure: This post contains affiliate links. ?

written by Caitlin Sacasas

Language: Japanese

Reading time: 13 minutes

Published: Apr 2, 2021

Updated: Oct 18, 2021

How to Write in Japanese — A Beginner’s Guide to Japanese Writing

Does the Japanese writing system intimidate you?

For most people, this seems like the hardest part of learning Japanese. How to write in Japanese is a bit more complex than some other languages. But there are ways to make it easier so you can master it!

Here at Fluent in 3 Months , we encourage actually speaking over intensive studying, reading, and listening. But writing is an active form of learning too, and crucial for Japanese. Japanese culture is deeply ingrained in its writing systems. If you can’t read or write it, you’ll struggle as you go along in your studies.

Some of the best Japanese textbooks expect you to master these writing systems… fast . For instance, the popular college textbook Genki , published by the Japan Times, expects you to master the basics in as little as a week. After that, they start to phase out the romanized versions of the word.

It’s also easy to mispronounce words when they’re romanized into English instead of the original writing system. If you have any experience learning how to write in Korean , then you know that romanization can vary and the way it reads isn’t often how it’s spoken.

Despite having three writing systems, there are benefits to it. Kanji, the “most difficult,” actually makes memorizing vocabulary easier!

So, learning to write in Japanese will go a long way in your language studies and help you to speak Japanese fast .

Why Does Japanese Have Three Writing Systems? A Brief Explainer

Japanese has three writing systems: hiragana, katakana, and kanji. The first two are collectively called kana and are the basics of writing in Japanese.

Writing Kana

If you think about English, we have two writing systems — print and cursive. Both print and cursive write out the same letters, but they look “sharp” and “curvy.” The same is true for kana. Hiragana is “curvy” and katakana is “sharp,” but they both represent the same Japanese alphabet (which is actually called a syllabary). They both represent sounds, or syllables, rather than single letters (except for vowels and “n”, hiragana ん or katakana ン). Hiragana and katakana serve two different purposes.

Hiragana is the most common, and the first taught to Japanese children. If this is all you learn, you would be understood (although you’d come across child-like). Hiragana is used for grammar functions, like changing conjugation or marking the subject of a sentence. Because of this, hiragana helps break up a sentence when combined with kanji. It makes it easier to tell where a word begins and ends, especially since Japanese doesn’t use spaces. It’s also used for furigana, which are small hiragana written next to kanji to help with the reading. You see furigana often in manga , Japanese comics, for younger audiences who haven’t yet learned to read all the kanji. (Or learners like us!)

Katakana serves to mark foreign words. When words from other languages are imported into Japanese, they’re often written in Japanese as close as possible to the original word. (Like how you can romanize Japanese into English, called romaji). For example, パン ( pan ) comes from Spanish, and means “bread.” Or from English, “smartphone” is スマートフォン ( suma-tofon ) or shortened, slang form スマホ ( sumaho ). Katakana can also be used to stylistically write a Japanese name, to write your own foreign name in Japanese, or to add emphasis to a word when writing.

Writing Kanji

Then there’s kanji. Kanji was imported from Chinese, and each character means a word, instead of a syllable or letter. 犬, read inu , means “dog.” And 食, read ta or shoku , means “food” or “to eat.” They combine with hiragana or other kanji to complete their meaning and define how you pronounce them.

So if you wanted to say “I’m eating,” you would say 食べます ( tabemasu ), where -bemasu completes the verb and puts it in grammatical tense using hiragana. If you wanted to say “Japanese food,” it would be 日本食 ( nipponshoku ), where it’s connected to other kanji.

If you didn’t have these three forms, it would make reading Japanese very difficult. The sentences would run together and it would be confusing. Like in this famous Japanese tongue twister: にわにはにわにわとりがいる, or romanized niwa ni wa niwa niwatori ga iru . But in kanji, it looks like 庭には二羽鶏がいる. The meaning? “There are chickens in the garden.” Thanks to the different writing systems, we know that the first niwa means garden, the second ni wa are the grammatical particles, the third niwa is to say there are at least two, and niwatori is “chickens.”

Japanese Pronunciation

Japanese has fewer sounds than English, and except for “r,” most of them are in the English language. So you should find most of the sounds easy to pick up!

Japanese has the same 5 vowels, but only 16 consonants. For the most part, all syllables consist of only a vowel, or a consonant plus a vowel. But there is the single “n,” and “sh,” “ts,” and “ch” sounds, as well as consonant + -ya/-yu/-yo sounds. I’ll explain this more in a minute.

Although Japanese has the same 5 vowel sounds, they only have one sound . Unlike English, there is no “long A” and “short A” sound. This makes it easy when reading kana because the sound never changes . So, once you learn how to write kana, you will always know how to pronounce it.

Here’s how the 5 vowels sound in Japanese:

- あ / ア: “ah” as in “latte”

- い / イ: “ee” as in “bee”

- う / ウ: “oo” as in “tooth”

- え / エ: “eh” as in “echo”

- お / オ: “oh” as in “open”

Even when combined with consonants, the sound of the vowel stays the same. Look at these examples:

- か / カ: “kah” as in “copy”

- ち / チ: “chi” as in “cheap”

- む / ム: “mu” as in “move”

- せ / セ: “se” as in “set”

- の / ノ: “no” as in “note”

Take a look at the entire syllabary chart:

Based on learning how to pronounce the vowels, can you pronounce the rest of the syllables? The hardest ones will be the R-row of sounds, “tsu,” “fu,” and “n.”

For “r” it sounds between an “r” and an “l” sound in English. Almost like the Spanish, actually. First, try saying “la, la, la.” Your tongue should push off of the back of your teeth to make this sound. Now say “rah, rah, rah.” Notice how your tongue pulls back to touch your back teeth. Now, say “dah, dah, dah.” That placement of your tongue to make the “d” sound is actually where you make the Japanese “r” sound. You gently push off of this spot on the roof of your mouth as you pull back your tongue like an English “r.”

“Tsu” blends together “t” and “s” in a way we don’t quite have in English. You push off the “t” sound, and should almost sound like the “s” is drawn out. The sound “fu” is so soft, and like a breath of air coming out. Think like a sigh, “phew.” It doesn’t sound like “who,” but a soft “f.” As for our lone consonant, “n” can sound like “n” or “m,” depending on the word.

Special Japanese Character Readings and How to Write Them

There are a few Japanese characters that combine with others to create more sounds. You’ll often see dakuten , which are double accent marks above the character on the right side ( ゙), and handakuten , which is a small circle on the right side ( ゚).

Here’s how dakuten affect the characters:

And handakuten are only used with the H-row characters, changing it from “h” to “p.” So か ( ka ) becomes が ( ga ), and ひ ( hi ) becomes either び ( bi ) or ぴ ( pi ).

A sokuon adds a small っ between two characters to double the consonant that follows it and make a “stop” in the word. In the saying いらっしゃいませ ( irasshaimase , “Welcome!”), the “rahs-shai” has a slight glottal pause where the “tsu” emphasizes the double “s.”

One of the special readings that tend to be mispronounced are the yoon characters. These characters add a small “y” row character to the other rows to blend the sounds together. These look like ちゃ ( cha ), きょ ( kyo ), and しゅ ( shu ). They’re added to the “i” column of kana characters.

An example of a common mispronunciation is “Tokyo.” It’s often said “Toh-key-yo,” but it’s actually only two syllables: “Toh-kyo.” The k and y are blended; there is no “ee” sound in the middle.

How to Read, Write, and Pronounce Kanji Characters

Here’s where things get tricky. Kanji, since it represents a whole word or idea, and combines with hiragana… It almost always has more than one way to read and pronounce it. And when it comes to writing them, they have a lot more to them.

Let’s start by breaking down the kanji a bit, shall we?

Most kanji consist of radicals, the basic elements or building blocks. For instance, 日 (“sun” or “day”) is a radical. So is 言 (“words” or “to say”) and 心 (“heart”). So when we see the kanji 曜, we see that “day” has been squished in this complex kanji. This kanji means “day of the week.” It’s in every weekday’s name: 月曜日 ( getsuyoubi , “Monday”), 火曜日 ( kayoubi , “Tuesday”), 水曜日 ( suiyoubi , “Wednesday”), etc.

When the kanji for “words” is mixed into another kanji, it usually has something to do with conversation or language. 日本語 ( nihongo ) is the word for “Japanese” and the final kanji 語 includes 言. And as for 心, it’s often in kanji related to expressing emotions and feelings, like 怒る ( okoru , “angry”) and 思う ( omou , “to think”).

In this way, some kanji make a lot of sense when we break them down like this. A good example is 妹 ( imouto ), the kanji for “little sister.” It’s made up of two radicals: 女, “woman,” and 未, “not yet.” She’s “not yet a woman,” because she’s your kid sister.

So why learn radicals? Because radicals make it easier to memorize, read, and write the kanji. By learning radicals, you can break the kanji down using mnemonics (like “not yet a woman” to remember imouto ). If you know each “part,” you’ll remember how to write it. 妹 has 7 strokes to it, but only 2 radicals. So instead of memorizing tons of tiny lines, memorize the parts.

As for pronouncing them, this is largely a memorization game. But here’s a pro-tip. Each kanji has “common” readings — often only one or two. Memorize how to read the kanji with common words that use them, and you’ll know how to read that kanji more often than not.

Japanese Writing: Stroke Order

So, I mentioned stroke order with kanji. But what is that? Stroke order is the proper sequence you use to write Japanese characters.

The rule of stroke order is you go from top to bottom, left to right.

This can still be confusing with some complex kanji, but again, radicals play a part here. You would break down each radical top left-most stroke to bottom right stroke, then move on to the next radical. A helpful resource is Jisho.org , which shows you how to properly write all the characters. Check out how to write the kanji for “kanji” as a perfect example of breaking down radicals.

When it comes to kana, stroke order still matters. Even though they’re simpler, proper stroke order makes your characters easier to read. And some characters rely on stroke order to tell them apart. Take シ and ツ:

[Shi and Tsu example]

If you didn’t use proper stroke order, these two katakana characters would look the same!

How to Memorize Japanese Kanji and Kana

When it comes to Japanese writing, practice makes perfect. Practice writing your sentences down in Japanese, every day. Practice filling in the kana syllabary chart for hiragana and katakana, until there are no blank boxes and you’ve got them all right.

Create mnemonics for both kanji and kana. Heisig’s method is one of the best ways to memorize how to write kanji with mnemonics. Using spaced repetition helps too, like Anki. Then you’re regularly seeing each character, and you can input your mnemonics into the note of the card so you have it as a reminder.

Another great way to practice is to write out words you already know. If you know mizu means “water,” then learn the kanji 水 and write it with the kanji every time from here on out. If you know the phrase おはようございます means “good morning,” practice writing in in kana every morning. That phrase alone gives you practice with 9 characters and two with dakuten! And try looking up loan words to practice katakana.

Tools to Help You with Japanese Writing

There are some fantastic resources out there to help you practice writing in Japanese. Here are a few to help you learn it fast:

- JapanesePod101 : Yes, JapanesePod101 is a podcast. But they often feature YouTube videos and have helpful PDFs that teach you kanji and kana! Plus, you’ll pick up all kinds of helpful cultural insights and grammar tips.

- LingQ : LingQ is chock full of reading material in Japanese, giving you plenty of exposure to kana, new kanji, and words. It uses spaced repetition to help you review.

- Skritter : Skritter is one of the best apps for Japanese writing. You can practice writing kanji on the app, and review them periodically so you don’t forget. It’s an incredible resource to keep up with your Japanese writing practice on the go.

- Scripts : From the creator of Drops, this app was designed specifically for learning languages with a different script from your own.

How to Type in Japanese

It’s actually quite simple to type in Japanese! On a PC, you can go to “Language Settings” and click “Add a preferred language.” Download Japanese — 日本語 — and make sure to move it below English. (Otherwise, it will change your laptop’s language to Japanese… Which can be an effective study tool , though!)

To start typing in Japanese, you would press the Windows key + space. Your keyboard will now be set to Japanese! You can type the romanized script, and it will show you the suggestions for kanji and kana. To easily change back and forth between Japanese and English, use the alt key + “~” key.

For Mac, you can go to “System Preferences”, then “Keyboard” and then click the “+” button to add and set Japanese. To toggle between languages, use the command key and space bar.

For mobile devices, it’s very similar. You’ll go to your settings, then language and input settings. Add the Japanese keyboard, and then you’ll be able to toggle back and forth when your typing from the keyboard!

Japanese Writing Isn’t Scary!

Japanese writing isn’t that bad. It does take practice, but it’s fun to write! It’s a beautiful script. So, don’t believe the old ideology that “three different writing systems will take thousands of hours to learn!” A different writing system shouldn’t scare you off. Each writing system has a purpose and makes sense once you start learning. They build on each other, so learning it gets easier as you go. Realistically, you could read a Japanese newspaper after only about two months of consistent studying and practice with kanji!

Caitlin Sacasas

Content Writer, Fluent in 3 Months

Caitlin is a copywriter, content strategist, and language learner. Besides languages, her passions are fitness, books, and Star Wars. Connect with her: Twitter | LinkedIn

Speaks: English, Japanese, Korean, Spanish

Have a 15-minute conversation in your new language after 90 days

Japanese Writing Lab #1: Basic self-introduction

In a recent post I announced I would be starting a new program on my blog called “Japanese Writing Lab” that aims to motivate people to practice writing in Japanese, provides feedback on their writing, and allows them to see posts of other Japanese learners. This article represents the first writing assignment of that program.

For this assignment, I’d like to focus on a very common, but important topic: self-introduction, known as 自己紹介 (jiko shoukai) in Japanese.

Self-introductions can range widely from formal to casual, and from very short (name only) to much longer. This time, I’d like everyone to focus on writing a basic self-introduction whose main purpose is to actually introduce yourself to me and others in the group. So while it is a writing exercise, it actually serves an important purpose as well. Try to keep it brief (a few sentences is fine) and stick more to written language as opposed to spoken language. For example, you would avoid using things like “あの。。。” which you might say if you actually spoke a self-introduction.

For those who are comfortable writing a self-introduction in Japanese, you can go ahead and get started. If you have written one recently, I suggest you try to write one again from scratch without referring to it unless you really get stuck.

Once you finish this writing assignment please post it via one of the two following methods:

- For those who have a blog (WordPress or anywhere else is fine): post it on your blog, and post a comment on this article including a link to your post. I also suggest adding a link on your post back to this article, so people who find your post can follow it to read other people’s submissions.

- For those who don’t have a blog: simply post it as a comment to this article with the text you’ve written. [Note: creating a blog is pretty easy and free on many sites, so if you have a few minutes I’d just consider just trying to create a blog]

I’ll be reading through the submitted assignments and will try to make constructive comments. I highly recommend for everyone submitting to read other people’s submissions.

For those who are not too familiar with how to write self-introductions in Japanese, here is a general template to help you get started (taken from this Japanese website). If you want to do your own research on how to write a self-introduction, that is fine as well. Feel free to omit any of the below categories, for example if you don’t want to discuss where you live.

Keep in mind that for a self-introduction in Japanese, it is usually best to use at minimum basic polite language, like ~です and ~ます, since you aren’t likely to be on very familiar terms with those you are speaking to.

General template for basic self-introduction

僕(私) の名前は [your name here] です。

- Place where you live (住所)

住所は[place where you live]というところです。

- Hobbies (趣味)

趣味は [one or more of your hobbies]です。

仕事は「your current job」をしています。

- Positive ending

[try to think of something positive to close with]

My submission

For each assignment I will give my submission as well, to help give you ideas. Feel free to send me questions or comments about my submission.

For this assignment I’ll keep things pretty simple and mostly follow the template I gave above, but in future assignments I’ll start using more advanced language and get more creative.

僕の名前はlocksleyuです。

住所はオレゴン州のポートランドですが、先週までは南フロリダに住んでいました。

趣味は色々ありますが、最近は日本の小説を読んだりチェスをやったりしています。

仕事はソフトウェア開発をしています。

このクラスで日本語の文章力を向上できたらいいと思います。

よろしくお願いします。

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

22 thoughts on “ Japanese Writing Lab #1: Basic self-introduction ”

Hi – I put together a WordPress site today so I could participate in this, and also to encourage me to write in Japanese.

Here’s my basic self introduction article: https://bokunojapanese.wordpress.com/2016/05/30/japanese-writing-lab-1-basic-self-introduction/

I tried once yesterday and once just now to post here and I am not seeing anything getting through. Are these comments moderated? Is there some other issue? I’m sick of retyping my introduction 🙁

The comments are moderated (that is the default setting of WordPress) but I check very often and approve pretty much all comments except for Spam. For some reason I didn’t see any of your comments from yesterday, only two from today.

I’ll read your other comment and respond now.

OK, this blog doesn’t seem to accept Japanese characters as comments (I just tried a third time).

I’m sorry that you are experiencing trouble. I’ll try to do my best help you out so we can get this solved (:

I have used Japanese before in comments. Let’s test now:

こんにちは [<- can you read this?] What happens when you try to write Japanese characters? Can you please make a post like this with some Japanese and some English so I can see what it looks like? Also, what browser/OS are you using? Can you try a variation of either? I am using Safari/Mac OS.

Thanks for the reply! Yeah, I’m reading that. The last three comments I have made that have included either all Japanese characters or a mix of Japanese and English have just…vanished. Like, I click “post” and the page refreshes but I don’t see my comment or even a “Your comment is pending” notification. I’m on Chrome on Mac OS, everything’s reasonably up to date.

Here’s a comment with English and hiragana only: こんにちは Thanks for helping me debug and sorry to be leaving so many comments on the blog ;_;

Here’s a comment with English, hiragana and kanji: こんいちは 漢字は難しいですが、大切です。

Everything looks great now, I can see all the characters fine (: I’m guessing that was just some temporary issue with WordPress.

You can go ahead and try to put your self-introduction now. Just make a backup copy in case it gets deleted again.

You’re not going to believe this, but it STILL isn’t posting. I was avoiding making a new blog because I thought it would be “more work” but now I’m thinking that would be simpler after all.

Thats so weird, I wonder why. Maybe if you make a longer comment it doesn’t like it?

I agree it will probably be easier at this point to create your own blog, and that will have other benefits for you in the future.

But if you still want to try and troubleshoot the original issue I can help…

The good news is that WordPress makes it really easy to set up a new blog these days. I guess in retrospect I should have done that to begin with. Thanks for your help trying to debug this issue! https://nihongonoheya.wordpress.com/2016/06/02/first-blog-post/

Great, glad you were able to make a blog so easily! Will check out your blog later today when I get more time.

Hi, I have been reading several of your articles with great interest. The first that lead me to you was your comments on ‘Hibana’ by Naoki Matayoshi. A friend of mine in Japan is reading this book and I was curious about its content. Your translation is amazing. To introduce myself I set up a site, above link, however it doesn’t really seem to be a blog as such, so I may need to change that later. Anyway it’s accepted the script ok so you should be able to read it. I hope to join in here to improve my Japanese. Thanks for your time, Sylvia

Thanks very much for the comment and feedback!

Also, I’m glad you are interested in joining my program. I checked out your site, but like you said it seems like it isn’t exactly a blog, so I am not sure if I will be able to comment. Without that, it will be hard for me to correct your writings (I found a few errors I wanted to point out).

If it’s not too much trouble, would you mind trying to create a blog on WordPress.com? It should be pretty easy and it’s free.

Hi, Thank you for your reply. I think I’ve sorted it OK. See link below, I’ve never done a blog before so this is new to me! https://kafuka97.wordpress.com/

I just copied what I wrote before, no changes. Many thanks, Sylvia

PS: I do have a website which I have sent a link to.

Hello! My name is Jheanelle, I just found your website today and I think I’ve already looked through have of it. Its amazing. I’m interested in doing the assignments but I don’t have a blog so I’ll post it in the comments section.

ジェネルと言います。今日本に住んで仕事にしています。私は英語の先生です。 色々な趣味があります。例えば、寝たり、韓国の番組を見たり、本を読んだりするのが好きです。 日本語もっと上手になりたいそしてこのブログを見つけて嬉しくなった

どうぞよろしくお願いします

Hello Jheanelle. I’m sorry for the late reply but your message was showing up in Spam on my blog for some reason.

Thanks for the submission. Right now I am sort of taking a break from the writing labs since I didn’t get too much response from my readers, but I will consider restarting them again at some point. There is a few others however I posted (up to #3 or #4, I think).

I hope your Japanese studies are going well.

One minor comment, in your sentence “今日本に住んで仕事にしています” I think maybe you could have said: “今日本で仕事をしています” or “今日本に住んでで仕事もしています”

These might sound a little better.

One more thing, I recommend watching Japanese dramas instead of Korean if you want to improve faster (:

Hello locksleyu, I just posted my self-introduction here: https://soreymikleo1421.wordpress.com/2021/05/21/japanese-writing-lab-1-basic-self-introduction/ Thank you in advance!

Thanks! I just posted a few comments.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Currently you have JavaScript disabled. In order to post comments, please make sure JavaScript and Cookies are enabled, and reload the page. Click here for instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Japanizing Your Computer Formatted papers for learning Japanese and "How to" directions 原稿用紙 (げんこうようし:Sakubun formatted paper) 400 (20X20) PDF format (better copy) and JPG format (click and drag to your desktop) 200 (20X10 1/2 page) PDF format and JPG format "How to" directions How to use 原稿用紙 (げんこうようし) ワープロフォーマット (よこがき: horizontal) ワープロフォーマット(たてがき: vertical) かな、漢字練習用紙 (かな、かんじれんしゅうようし:Kana and Kanji practice formatted paper) Kanji, reading, and meaning practice Kanji and reading practice (small) Kanji and reading practice (large) Kana and Kanji practice sheet (the page without spaces for furigana) Language Links Culture Links Radio/News Links Travel Links For Teachers Links Miscellaneous Links (scholarships, internships, jobs, etc) JOSHU Utilities

Formatting Japanese Writing

Formatting Japanese writing correctly is quite different to formatting English when hand writing. While modern Japanese is usually written from right to left as in English, it can also be written as in the traditional way which is right to left and top to bottom.

Formatting Japanese in such a way is quite formal and is used for written work such as homework, essays or letters to others.

As all Japanese characters fit perfectly inside a square, it helps formatting Japanese work like this using what’s called a Genko Yoshi which is a type of Japanese paper used for writing. It is printed with squares, typically 200 or 400 per sheet, with each square designed to accommodate a single Japanese character or punctuation mark.

Formatting Japanese using a Genko Yoshi

Below is a diagram outlining some of the different rules of formatting Japanese using a Genko Yoshi borrowed from this site.

1 . Title on the 1st line, first character in the 4th square.

2 . Author’s name on the 2nd line, with 1 square between the family name and the given name, and 1 empty square below.

3 . First sentence of the essay begins on the 3rd line, in the 2nd square. Each new paragraph begins on the 2nd square.

4 . Subheadings have 1 empty line before and after, and begin on the 3rd square of a new line.

5 . Punctuation marks normally occupy their own square, except when they will occur at the top of a line, in which case they share a square with the last character of the previous line.

Category: Resources • Writing

Tags: formatting • hiragana • japanese • language • learning • writing

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Article by: Duncan Sensei

Site Content

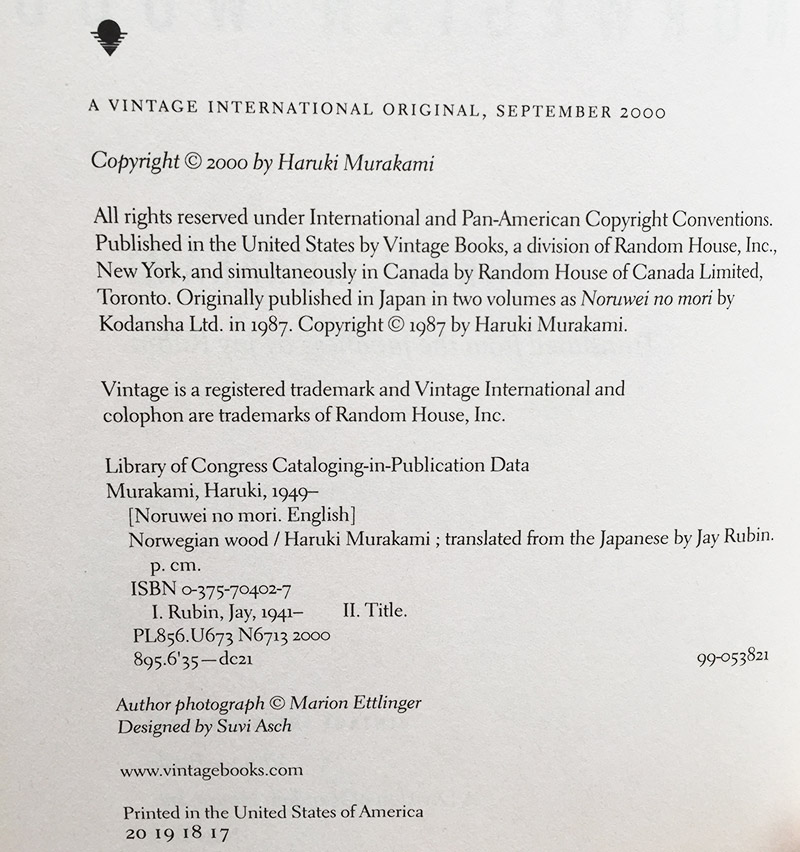

The columbia anthology of japanese essays.

Zuihitsu from the Tenth to the Twenty-First Century

Edited and translated by Steven D. Carter

Columbia University Press

Pub Date: October 2014

ISBN: 9780231167710

Format: Paperback

List Price: $45.00 £38.00

Shipping Options

Purchasing options are not available in this country.

ISBN: 9780231167703

Format: Hardcover

List Price: $135.00 £113.00

ISBN: 9780231537551

Format: E-book

List Price: $44.99 £38.00

- EPUB via the Columbia UP App

- PDF via the Columbia UP App

The focused ramble of the traditional Japanese essay format called zuihitsu (literally, 'following the brush') has appealed to writers of both genders, all ages, and every class in Japanese society. Highly personal, these essays contain dollops of philosophy, odd anecdotes, quiet reflection, and pronouncements on taste. In running alongside the main tracks of Japanese literature, this broad collection of zuihitsu brims with idiosyncratic interest. Liza Dalby, author of The Tale of Murasaki and East Wind Melts the Ice: A Memoir Through the Seasons

Savor a copy of The Columbia Anthology of Japanese Essays , and take a contemplative walk through the Japanese mind, full of poetic turns and pithy longings, ribald humor and lofty aspirations. Kris Kosaka, The Japan Times

Rich and highly enjoyable.... This evocative selection serves both as an excellent introduction to the genre for the English-speaking world and as a reminder that, no matter how distant or seemingly different the society, people's individual struggles, aspirations and aesthetics transcend their own times. Morgan Giles, Times Literary Supplement

Winner, 2016 2015-2016 Japan-United States Friendship Commission Prize for the Translation of Japanese Literature

About the Author

- Asian Fiction and Literature

- Asian Literature in Translation

- Asian Studies

- Asian Studies: Arts and Culture

- Asian Studies: Fiction and Literature

- Fiction and Literature

- Literary Studies

- Asian Studies: East Asian History

- History: East Asian History

2022 IEICE Society Conference

Online September 6-9, 2022

新しい生活様式の社会を支える電子情報通信

Writing your paper, paper example.

- Although basic style settings are incorporated in each template, these are just examples and you may use different style settings as long as you observe the basic format requirements, such as the paper size and margins.

- If you have a template you wish to recommend, we would appreciate receiving it. Please click here to send an email with your recommended template attached.

Writing your paper in electronic form

- Maximum file size The file size of pdf file for general session will be smaller than 500K and the size will be smaller than 1MB for the symposium session. Please be careful if the pdf file size over the above limits, it cannot be uploaded from the web site. You can submit only a single file. Do not compress your file or apply security settings to it. (Please refer to " How to make a PDF (Portable Document Format) file" to learn how to reduce the file size.)

- Page format Paper size: A4. Margins must not be smaller than the following. Top margin: 30 mm. Bottom margin: 27 mm. Left margin: 18 mm. Right margin: 18 mm. Inter-column spacing: 7 mm.

- All used fonts in the pdf file must be embedded. The submitted pdf file will be published in DVD-ROM available both for Windows and Macintosh. (Please select "High Quality" or "Press Quality" in job options when you make your PDF file.) In case that the fonts might not be embedded, they cannot be expressed properly under some machine environment.

- Permitted characters If you write your paper in Japanese, use only those characters covered by the JIS Second Level in order to avoid characters turning into meaningless symbols, depending on the type of computer used. In particular, if Macintosh users wish to use special symbols such as Roman numerals or numbers in circles, they should use the symbols listed in the JIS Codes.

- Colors There is no restriction on colors used for characters or in diagrams. However, since papers will be printed on a monochrome printer for use in paper copies, select colors that are clearly distinguishable when printed in monochrome.

- Resolution of photos and images The quality of photos and images may be degraded when a file containing them is converted to a PDF file. When you convert your file into a PDF file, you are recommended to select the highest quality that allows you to keep within the file size limitation.

- File type The PDF (Portable Document Format) file you submit must be such that it can be displayed and printed by anyone using Adobe Reader 7.0 or higher.

- Link PDF document must not contain link annotation(s).

- Filename The filename should be your "application number" with the extension ".pdf".

- Application and OS for making a PDF file There are no restrictions on the application used for making a PDF file. We recommend that you use WindowsXP or higher, or Macintosh 10.5 or higher, for the operating system.

- How to make a PDF file A PDF file is normally made using Acrobat 7.0 or higher (or an equivalent product). For information about how to make a PDF file, refer to the manual for Acrobat (or its equivalent), or click here (Japanese only) . Details of Acrobat are available at https://www.adobe.com/ .

- It is recommended that you use Acrobat Distiller to make a PDF file. In particular, if your file includes illustrations or other images, equations, or charts, do not use PDF Writer to make a PDF file.

- After you have made a PDF file on your computer, print it using a different computer to check if it is printed correctly. (Sometimes, characters in equations, table or diagrams turn into gibberish.)

- Deadline for submission of paper Your paper must arrive before 17:00 hours sharp, Wednesday, June 29, 2022 (17:00 hours, Japan time) .

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

An Introduction to Japanese Sentence Structure

So you’ve learned some Japanese vocabulary .

Now, how do you string it into coherent sentences?

You’ll need to learn about Japanese word order, correct particle usage and the omnipresent です (“desu”).

This quick introduction will help you figure out how to get started with Japanese sentence structure.

The Japanese Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) Structure

The japanese copula, です, past tense with でした, levels of formality of です, japanese verb placement, japanese verb categories, japanese verb negations, using verbs to express nuances, japanese post-positions, japanese particles, は (topic marker), が (subject marker), を (object marker), の (possession marker), に (time and movement marker), へ (direction and destination marker), で (location and means marker), も (similarity marker), と (noun connector), japanese adjective placement, い adjectives, な adjectives, modifying japanese adjectives, japanese question structure, inferred subjects in japanese, breaking japanese sentence structure rules, and one more thing....

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Japanese sentences follow an SOV format.

SOV means “subject-object-verb.” This means that the subject comes first, followed by object or objects, and the sentence ends with the verb. You’ll see lots of examples of this throughout this article.

Let’s look at an example:

ジンボはリンゴを食べる。 じんぼはりんごをたべる。 Jimbo — an apple — eats (Jimbo eats an apple.)

“Jimbo” is the subject, “eats” is the verb and “an apple” is the object. This sentence follows the SOV formula.

If you’ve ever heard someone speak Japanese, be it in real life or on TV, you’ve almost certainly come across the Japanese word です .

です is one of the most basic terms in the Japanese language, literally meaning “to be” or “is.” Many think of it as just a formality marker, but it serves all sorts of functions.

です is a copula, meaning that it connects the subject of the sentence with the predicate, thus creating a complete sentence. The most basic Japanese sentence structure is “A は B です” (A is B).

My name is Amanda. 私はアマンダ です 。 わたしはあまんだ です 。

He is American. 彼はアメリカ人 です 。 かれはあめりかじん です 。

です also serves to mark the end of a sentence , taking the place of a verb. Also, です never comes at the end of sentences that have verbs ending in ます.

Tom likes tea. トムさんはお茶が好き です 。 とむさんはおちゃがすき です 。

Tom drinks tea. トムさんはお茶を飲み ますです 。(Incorrect) トムさんはお茶を飲み ます 。(Correct) とむさんはおちゃをのみ ます

When describing something that happened in the past, です turns into でした .

The exam was easy. 試験は簡単 でした 。 しけんはかんたん でした。

Yesterday was my birthday. 昨日は私の誕生日 でした 。 きのうはわたしのたんじょうび でした。

As with many words in Japanese, です comes in different levels of formality : だ, です, である and でございます:

- です is the basic polite form and will be most useful in everyday conversation.

- だ is found in casual speech among friends or family.

- である is used in formal written Japanese, such as in newspapers.

- でございます is the most formal form, used when speaking to your superior or someone important.

If you’re at a loss for which form to use, just stick with です. The person you’re talking to will know you’re trying to be polite!