About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Get Involved

- Reading Materials

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

The Knowledge Economy

We define the knowledge economy as production and services based on knowledge-intensive activities that contribute to an accelerated pace of technical and scientific advance, as well as rapid obsolescence. The key component of a knowledge economy is a greater reliance on intellectual capabilities than on physical inputs or natural resources. We provide evidence drawn from patent data to document an upsurge in knowledge production and show that this expansion is driven by the emergence of new industries. We then review the contentious literature that assesses whether recent technological advances have raised productivity. We examine the debate over whether new forms of work that embody technological change have generated more worker autonomy or greater managerial control. Finally, we assess the distributional consequences of a knowledge-based economy with respect to growing inequality in wages and high-quality jobs.

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

Organizations in the knowledge economy. An investigation of knowledge-intensive work practices across 28 European countries

Journal of Advances in Management Research

ISSN : 0972-7981

Article publication date: 10 May 2022

Issue publication date: 24 January 2023

This paper aims to investigate whether the shift towards the knowledge economy (e.g. an increasing reliance in knowledge in the production of goods and services) is related to the work practices of organizations (aimed at the provision of autonomy, investments in training and the use of technology).

Design/methodology/approach

The analyses are based on data about over 20,000 companies in 28 European countries. National level indicators of knowledge intensity are related to the work practices of these organizations. Multilevel analysis is applied to test hypotheses.

The results show that there is a strong and positive relationship between the knowledge intensity of the economy and the use of knowledge intense work practices.

Originality/value

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first papers to test whether knowledge intensity at the national level is related to the work practices of organizations.

- Organizational design

- Knowledge management

- Diffusion of innovation

- Knowledge economy

Koster, F. (2023), "Organizations in the knowledge economy. An investigation of knowledge-intensive work practices across 28 European countries", Journal of Advances in Management Research , Vol. 20 No. 1, pp. 140-159. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAMR-05-2021-0176

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Ferry Koster

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

The shift toward the knowledge economy is believed to move organizations toward more flexibility, decentralization and autonomy ( Alvesson, 2004 ; Powell and Snellman, 2004 ; Foss, 2005 ; Makani and Marche, 2010 ; Khadir-Poggi and Keating, 2013 ; Lee, 2015 ; Ullah and Narain, 2020 ; Valeri, 2021 ). A basic assumption in these studies is that structures and practices of organizations are affected by the environment in which they operate ( Neef, 1999 ; Ferreira et al ., 2018 ). While prior studies generated important insights, there are several ways to improve our understanding of the link between the knowledge economy and organizational practices. The present article aims to close three gaps in the current literature.

First, much of the research provides indirect evidence by focusing on the connection between the knowledge economy and work, rather than on the practices of organizations. For example, previous studies investigating how factors such as globalization and technological change affect labor demand ( Wood, 1987 ; Burris, 1998 ; Cerny, 1999 ; Martinaitis et al ., 2020 ) focus on tasks and jobs of workers ( Aoyama and Castells, 2002 ; Fernández-Macías, 2012 ; Sakamoto et al ., 2018 ; Kalleberg and Mouw, 2018 ). Other studies do center on organizations and the role of decentralization, adaptation and innovation in knowledge intense economies ( Switzer, 2008 ; Hodgson, 2016 ), but they remain largely theoretical. The present study fills this void by analyzing three knowledge-intensive work practices (KIWPs), namely (1) decentralized decision making (producing knowledge), (2) organizational learning practices (developing and distributing knowledge) and (3) the use of technology (applying knowledge). These work practices are derived from three approaches to organizations, namely the dynamic capabilities approach, organizational learning theories and models of technology adoption and diffusion.

Secondly, it is necessary to think about the knowledge economy in the sense of the degree of knowledge intensity of the economy, instead of stating that modern organizations operate in a knowledge economy ( Powell and Snellman, 2004 ; Manville and Ober, 2003 ; Nurunnabi, 2017 ). In this study, innovation is the independent rather than the dependent variable, which is common in innovation research (e.g. Crossan and Apaydin, 2010 ; Koster, 2021 ). In the present study, innovations serve as the starting point and the question is whether this creates an environment to which organizations adapt. Hence, the analyses relate to organizational mechanisms, such as learning and dynamic capabilities, emphasizing how organizations change their structures and processes to remain competitive ( Felin and Powell, 2016 ; Kapoor and Aggarwal, 2020 ). This leads to a more fine-grained understanding of how the knowledge economy affects organizations.

Finally, investigating how knowledge intensification of the economy relates to the work practices of organizations requires comparative research of organizations operating in different environments. Since knowledge intensification of the economy is a macro level factor, cross national research is required. Therefore, empirical research is conducted connecting the economy and the practices of organizations operating in different countries . Hence, this study answers to the call in the literature for more organizational research across countries ( Greenwood et al ., 2014 ).

To date, these three conditions are not met in a single study. Instead, there are studies of knowledge-intensive organizations and about the knowledge economy. But there is very little connection between them, while this is needed to show how the knowledge economy relates to the management of organizations. Gaining insights in the relationship between knowledge intensification of the economy and the work practices of organizations also has practical value for managers and consultants. Most and for all, this research helps organizations identifying which practices matter if they aim to increase their knowledge intensity. Furthermore, considering that economies vary in their level of knowledge intensity, research showing that knowledge intensification relates to organizational practices enables learning across organizations. For organizations in less knowledge intense economies, this information can help them to prepare them for the future (considering that economies move in the direction of increased knowledge intensity) and for organizations in the more knowledge intense economies it provides a benchmark to assess whether their current practices fit their environment.

Data of 20,672 companies in 28 countries gathered through the fourth European Company Survey (ECS), which was held in 2019, are combined with country level data about the knowledge intensity of the economy. These national level data (the European Innovation Scoreboard: EIS) are constructed by the European Commission (2020) . This article is structured as follows. In the next section, the link between knowledge intensity of the economy and knowledge intense work practices is further theorized and explored. The theoretical section results in the general hypothesis that organizations use more knowledge intense work practices if they operate in a knowledge economy, which is then tested using a multilevel regression analysis. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed in the closing section.

Work practices in the knowledge economy

The term knowledge economy is often used, but not always clearly defined. Powell and Snellman (2004) are an exception as their overview of studies into the knowledge economy starts with a clear definition, namely: the production of services and goods based on “knowledge-intensive activities” and a “greater reliance on intellectual capabilities” (p. 201). Technological changes and innovations underlie this shift in production processes. Although it is generally accepted that economies tend to move in the direction of a knowledge economy, there is some debate about the way in which it proceeds. The two sides of this debate focus on different aspects of the relationship between technology and economy. There are those believing that economies are entering a completely new phase that can be termed a “new economy”. These authors tend to argue that there is an abrupt break with the old economy because of technological change (see for example Schwab, 2016 ). Such conceptualizations of the economy view it as a series of distinguishable periods. However, historically it has happened too often that such breaks were announced, while afterward they turned out to be gradual changes and much of the economy stayed the same. This change-within-stability position is therefore taken by many researchers ( Boyd and Holton, 2018 ). A different position is taken by those arguing that one should look at the outcomes of these changes to conclude whether economies are entering a new era. This position is for example reflected by the well-known “productivity paradox” as well as by the theoretical argument that technological change is far less deterministic than is often assumed ( Burris, 1998 ; Swedberg, 2005 ; Boyd and Holton, 2018 ; Brynjolfsson et al ., 2018 ).

In other words, several researchers point out that technological change is not automatically visible in organizations, work practices, or productivity. Nevertheless, that technological change takes place is not disputed. In other words, while we are not entering a completely new economic reality disrupting the old economy, it is acknowledged that changes occur. For these changes to be visible, technologies need to be applied and used by workers and organizations to be effective ( Foster and Rosenzweig, 2010 ; Wensing and Krol, 2019 ). Conceptualizing the knowledge economy in terms of varying levels of knowledge intensity rather than dichotomously (stating that an economy is either a knowledge economy or not) is more accurate. It is a matter of degree.

The more knowledge intense the economy, the stronger the emphasis is on the producing, diffusing and applying knowledge ( Adler, 2001 ; Powell and Snellman, 2004 ). These knowledge-intensive activities are sometimes termed “knowledge work”. Nevertheless, the term needs further clarification as it refers to different aspects. Different conceptualizations can be found across the literature ( Kelloway and Barling, 2000 ). A large share of research regards knowledge work as work that is performed by a specific group and focuses on professions and occupations (e.g. Adler et al ., 2008 ; Paton, 2013 ). Other researchers emphasize the importance of personal characteristics and activities, such as creativity and individual learning, that enable workers to thrive in the knowledge economy. And still others argue that knowledge works implies specific behaviors like creating and sharing knowledge and information ( Kelloway and Barling, 2000 ). Without a doubt, occupations, persons, activities and organizational behavior are important aspects of knowledge work. Nevertheless, it overlooks the organizational side of the knowledge economy. That is, it does not include the mechanisms that are necessary for an organization to function in a knowledge-intensive environment. At the same time, it is through these organizational mechanisms that the knowledge economy affects the content of work, which then in turn leads to changes in the occupational structure and demand different kinds of activities and behavior in the workplace. The literature on knowledge-intensive organizations provides insights in some of the mechanisms and work practices that are central to such organizations stimulating and enabling the production, diffusion and use of knowledge ( Pyöriä, 2005 ).

Due to technological changes, the economic landscape reflects a system of economic opportunities based on connections and information ( Carlsson, 2004 ). This economic landscape is characterized by increasing knowledge intensity, a stronger focus on the adaptability of organizations as they operate in an economic system that is more dynamic due to the use of technology and the need to process information inside and outside organizations. The next question is what the implications are for the organization of work.

While there is some debate how to analyze knowledge work (and whether it refers to work in specific sectors or occupation or should be viewed as a kind of work behavior), when focusing on the characteristics of this work, the following stand out. Pyöriä (2005) distinguishes two ideal types of work, namely “traditional” and “knowledge” work. Knowledge work (1) puts more emphasis on professionalism, self-management and job and task circulation compared to traditional work; (2) is less standardized than traditional work; and (3) requires more learning (both in terms of formal education and on-the-job learning) compared to traditional work. Instead of focusing on the extremes of these types, it is also possible to interpret them as relative positions on a continuum from traditional to knowledge work. Again, it is not an either/or situations, but a matter of degree whether an organization has these knowledge work characteristics. In the next section, it is hypothesized how organizational practices relate to knowledge intensification.

Explaining KIWPs

Several organizational theories explain why organizations would apply certain practices in more knowledge intense economies. The main explanations are provided by theories concerning dynamic capabilities, organizational learning and the use of technology. Each of these set of theories focuses on different aspects of knowledge processes that are central to the knowledge economy.

From this it follows that it is expected that the more knowledge intense the economic environment is, the more organizations rely on decentralization.

From this it follows that it is expected that the more knowledge intense the economic environment is, the more organizations rely on formal and informal learning.

From this it follows that it is expected that the more knowledge intense the economic environment is, the more organizations have technology-related work practices.

Hence, the overall prediction is that it is expected that the more knowledge intense the economic environment is, the more organizations have KIWPs.

Figure 1 presents the research model that was developed in the previous sections. On top, there are the national level factors that are hypothesized to be related to the knowledge-intensive work practices that reside at the organizational level. Besides that, the figure acknowledges that knowledge intensity is not the only explanation of KIWPs and that there may be other factors at the organizational and the national level that also explain them.

Data and methods

Data from different sources are combined to conduct the analyses. Data at the organizational level are available through the ECS 2019 (ECS; Van Houten and Russo, 2020 ). The data for this survey are collected by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound) and the European Center for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop). This fourth edition of the ECS contains information about 21,869 establishments in 28 European countries (27 EU (European Union) member states and the UK). These company level data are combined with data at the national level. These national level data provide the possibility to investigate the impact of the knowledge intensity of the economy on KIWPs. Besides that, several control variables at the national level are included in the analyses. These national level data are accessed through Eurostat. The national level data are available for all 28 countries. There are, however, some missing values in the ECS; a total of 1,197 companies did not provide responses to the dependent variable in this study. These companies are excluded, and the analyses are carried out on the remaining 20,672 companies.

Knowledge-intensive work practices (KIWPs)

For how many employees in this establishment does their job include finding solutions to unfamiliar problems they are confronted with? Your best estimate is good enough. [ Unfamiliair problems ].

For how many employees in this establishment do their job include independently organizing their own time and scheduling their own tasks? Your best estimate is good enough. [ Scheduling ].

How many employees in this establishment are in jobs that require continuous training? Your best estimate is good enough. [ Continuous training ].

In 2018, how many employees in this establishment participated in training sessions on the establishment premises or at other locations during paid working time? Your best estimate is good enough. [ Participation in training ].

In 2018, how many employees in this establishment have received on-the-job training or other forms of direct instruction in the workplace from more experienced colleagues? Your best estimate is good enough. [ On-the-job training ].

How many employees in this establishment use personal computers or laptops to carry out their daily tasks? Your best estimate is good enough. [ Computers ].

Respondent are asked to indicate on a seven-point scale for each of these questions to how many of the employees it applies. The categories of these items are as follows: none at all, less than 20%, 20–39%, 40–59%, 60–79%, 80–99% and all.

Since these are separate items in the questionnaire, there is the possibility that they measure aspects of organizations that are unrelated. To assess whether the items measure a construct that can be labeled KIWPs, a reliability analysis is performed. This analysis shows that the items have a Cronbach's alpha of 0.71. Therefore, it is concluded that the items can be combined into a single scale. This scale is created by adding the scores on the items. These scores are divided by six. Hence the final scale also runs from 1 to 7.

Knowledge intensity economy

a. Human resources (educational level)

b. Attractive research systems (international competitiveness)

c. Innovation-friendly environment (opportunities)

a. Finance and support (financial resources)

b. Firm investments (knowledge investments)

a. Innovators (number of innovators)

b. Linkages (collaboration)

c. Intellectual assets (property rights)

a. Employments impacts (knowledge intense employment)

b. Sales impacts (exports and sales)

For detailed information about the dimensions and the underlying indicators, see the EIS 2020 methodology report ( European Commission, 2020 ). The indicators are measured with Eurostat data. Following an extensive procedure, these data are transformed to calculate an index: The Innovation Index that runs from 0–1 in theory. The Innovation Index is used as an indicator for measuring the knowledge economy. Powell and Snellman (2004 , p. 202) mention different approaches to measuring the knowledge economy, such as a focus on “stock of knowledge” (e.g. human, organizational and intellectual capital) or “activities” (e.g. R&D efforts, investments in information and communication technology). The advantage of the Innovation Index is that it does not have a narrow focus and integrates these approaches into a single measure. Hence, it includes several dimensions that are generally assumed to be central to the knowledge economy.

Control variables

At the national level, the analyses of knowledge-intensive work practices are controlled for GDP per capita in purchasing power standards (GDP pps) and the level of unemployment. Both statistics are taken from the Eurostat database. GDP pps expressed in relative terms, with a score of 100 as the EU average. The variable has a minimum of 53 and a maximum of 260 (the values are divided by 10). The level of unemployment is indicated with the percentage of the labor force without work and lies between 2 and 19%.

At the level of the establishments, several control variables are included. Three variables measure the use of technology by these establishments by asking whether they use it or not. Hence, these variables are dummy variables, with a 0 indicating that these technologies are not present and a 1 that they are. The variable robots are measured with the question “Robots are programmable machines that are capable of carrying out a complex series of actions automatically, which may include the interaction with people. Does this establishment use robots?”, the variable IT production is measured with the question “Does this establishment use data analytics (Data analytics refers to the use of digital tools for analysing data collected at this establishment or from other sources) to improve the processes of production or service delivery, and the variable IT monitoring is measured with the question “Does this establishment use data analytics to monitor employee performance?”. The variable hierarchical levels is measured with the question “… how many hierarchical levels do you have in this establishment?”. Then there are three questions measured on a 7-point scale (none at all, less than 20%, 20–39%, 40–59%, 60–79%, 80–99%, and all) about the employees in the establishment. The variable % managers is measured with the question “How many people that work in this establishment are managers? Your best estimate is good enough”, the variable % permanent employees is measured with the question “How many employees in this establishment have an open-ended contract? Your best estimate is good enough”, and the variable % part-time is measured with the question “How many employees in this establishment work part-time (part time refers to working less than 35 h per week)? Your best estimate is good enough”. The final variable organizational size is measured by asking the question “Approximately how many people work in this establishment?”. The variable organizational size has three categories, namely: 10–49, 50–249 and 250 and more.

Table 1 provides the summary statistics for all variables included in this study. As this table shows, the most common of the six KIWPs relates to the use of PCs and laptops and on-the-job-training. Secondly, there is considerable variation in the measure of knowledge intensity of the economy. Robots are used in 12% of the companies and IT systems for production and monitoring are applied more often (49 and 32% respectively). Finally, it is worth noting that organizations of different sizes and from all economic sectors are represented. Regarding organizational size, Table 1 shows that most organizations are small (with 10–49 workers).

The dataset has a hierarchical structure: companies are nested in countries. The overall expectation is that the knowledge economy at the country level is related to the knowledge intensity of the work practices that these companies apply. To get an accurate estimation it is necessary to take account of this nested structure of the data. Therefore, multilevel models ( Snijders and Bosker, 2011 ; Bickel, 2007 ) are estimated. Such models enable to distinguish variance at different levels, in this case the country level and the company level. To assess these models, several statistics are computed. The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) indicate how much of the variance resides at these two levels. The ICC provides information about the extent to which there is country level variance that can be explained by adding variables at that level. The next step in multilevel modeling is to investigate what happens to these variances after adding these variables. By adding company and country level variables, the ICC becomes smaller if they explain national level variation in KIWPs. Furthermore, by focusing on the variances at the two levels and by examining how they change after the additional variables are included, it is possible to assess how much of that variance is explained at the country level as well as at the company level. The fit of the multilevel models is investigated with likelihood ratio tests ( Peugh, 2010 ; Snijders and Bosker, 2011 ; Hox et al ., 2017 ). This test does not provide enough information to assess the fit of the model. However, by comparing the likelihood tests between the models, allows to test whether the difference between the models is statistically significant. The difference is called the deviance and is tested with a chi-squared test (with the number of parameters that are tested as the degrees of freedom) ( Snijders and Bosker, 2011 ).

For the present analyses, several steps are taken to test the hypotheses. First, the focus is on the composite measure of KIWPs (based on the results of the scale analysis). To get a baseline against which the consecutive models are compares, a so-called empty model is estimated. This empty model does not include explanatory variables and provides that variances at the country and the company level. Then a model is estimated with the control variables at the country level and the company level. The third model also includes the indicator for the knowledge economy (the Innovation Index). Besides testing the significance of these explanatory variables, it is also investigated whether it leads to an improvement of the model if these variables are added. Furthermore, it is assessed how much of the variance at the two levels is explained. Next to that, several other models are estimated, namely models with the separate KIWPs (six in total) and models in which the sub-dimensions of the Innovation Index are investigated separately. The models are structured using the same procedure as the models with the composite measure as the dependent variable. These additional tests serve as sensitivity analyses to see how robust the initial models are if other specifications are chosen.

Based on the country averages of the KIWPs (presented in Table 2 ), it can be concluded that the use of these practices is more common in Sweden, the UK and Finland and that companies in Romania, Bulgaria and Lithuania make less use of these practices. On a scale from 1–7, the average use in Sweden is 4.6 and 2.6 in Romania. Focusing on their scores on the Innovation Index, Sweden and Romania also have the highest and the lowest scores (0.71 and 0.16, respectively). To get a first impression of how the knowledge economy relates to the use of KIWPs, the correlation between the Innovation Index and the country level mean of the use of KIWPs is calculated. This analysis shows that there is a positive and statistically significant associated between them ( r = 0.78). Figure 2 shows this relationship. Clearly, there is a positive association between the innovation index and the use of KIWPs at the aggregate level. The next question is whether this association also holds in a multilevel framework controlling for factors at the national level and the level of the companies. To investigate this, several multilevel regression models are calculated.

Table 3 presents the results of the multilevel analysis with the composite measure of KIWPs as the dependent variable. Starting with the control variables, the following insights are gained. At the national level, GDP pps is positively related to the use of KIWPs. Furthermore, several characteristics at the company level explain the use of KIWPs. Notably, companies relying on robots and the two kinds of data analytics positively relate to the use of KIWPs. These practices are also more often applied in companies with more managers, more permanent workers, more fulltime workers and in smaller companies. Finally, it turns out that there are sectoral differences. The results show that KIWPs are particularly used by companies in three sectors: financial and insurance activities, professional, scientific and technical activities, and information and communication. Overall, these results emphasize the role of knowledge intensity at the organizational level in explaining KIWPs.

The final model presented in Table 3 also includes the knowledge economy indicator (the Innovation Index). Regarding the control variables, adding this indicator does not change the results for the company level variables, whereas the effect of GDP disappears. The latter finding suggests that higher GDP results in more knowledge intensity of the economy. Furthermore, there is a significant and positive relationship between the Innovation Index at the national level and the use of KIWPs, thus supporting the overall hypothesis that the knowledge economy is positively related with the knowledge intense work practices of organizations.

Looking at the explanatory contribution of the different models, the following is concluded. First, based on the empty model (the model without explanatory variables), Table 3 shows that 12% of the variance in KIWPs can be attributed to the national level. The other 88% is due to variance at the company level. Secondly, adding the control variables at the company and the country level reduces the variance at both levels. At the company level the reduction is 23% and at the country level the reduction is 31%. Finally, in the third model shown in Table 3 which includes the knowledge economy, the share of country level variances drops to 3% (implying a change of 75% in the intraclass correlation coefficient). Then, comparing the variance at the national level in the final model with that of the empty model, the Innovation Index reduces it with 80%. Put differently, besides having a positive and statistically significant impact, the Innovation Index explains a large share of the country level variance in KIWPs.

Before stating the overall hypothesis ( Hypothesis 4 ), three sub-hypotheses about the knowledge economy were formulated, namely that the knowledge economy would be related to decentralization, (formal and informal) learning and the use of technology. The models presented in Tables 4 and 5 , test these hypotheses, using information about unfamiliar problems and scheduling to indicate decentralization, variables measuring continuous learning, participation in training and on-the-job training as indicators for training, and the use of computers to indicator technology-use. The results of these models are in line with the three separate hypotheses: The Innovation Index is positively related with each of these indicators. Hence it is concluded that Hypothesis 1 – 3 also find empirical support.

Regarding the extent to which these indicators are explained by the knowledge economy, it turns out that the reduction in country level variance is the strongest in the use of work practices related to decentralization (71 and 53% for scheduling and unfamiliar problems, respectively) and that the reduction in continuous learning is the lowest (21%). All in all, the empirical results are in line with the four research hypotheses formulated in the theoretical section.

Finally, models are estimated with the four sub-dimensions of the Innovation Index (framework conditions, investments, innovation activities and impacts), as the explanatory variables (these models are not reported to save space, but they are available upon request). These variables are investigated separately. The analyses show that each of these dimensions positively relates to KIWPs, with the indicator measuring framework conditions, which include human resources, attractiveness of the research system and innovation-friendliness of the environment, leading to the largest reduction of variance at the country level (compared to the empty model, the country level variance is reduced with 75%) and impacts, in terms of employment and sales, having the lowest reduction in country level variance (a reduction of 56%). Hence, while there is some variation in the impact across the different indicators of KIWPs on the one hand and the sub-dimensions of the Innovation Index, these additional analyses indicate the outcomes remain if the focus is on these separate indicators. It should also be noted that the strongest results if composite indicators are used: an overall indicator of the knowledge economy with a summary score for KIWPs leads to the strongest (in terms of explained variance) models.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper focuses on how the knowledge management practices of organizations relate to the structure of the economy in which they operate. The analysis of a representative sample of companies in 28 European countries leads to the overall conclusion that the more knowledge intense an economy is, the more likely it is that organizations apply knowledge intense work practices. This insight has several implications. First, it shows that developments external to organizations has consequences for the way they are structured, in this case: that the economic conditions that organizations deal with are transferred into the way they manage their knowledge. Whereas this is often assumed, researching organizational structures in a cross-national comparative perspective is not a common practice in organizational studies. Hence, empirically, this link is not often established. Secondly, the implication of this finding is that the knowledge intensity of the economy is associated with the knowledge intensity of the work practices for all organizations in an economy. This in turn provides evidence for the discussion about how to understand the knowledge intensification of the economy and whether this concentrated in certain sector of the economy or whether it means that it affects all organizations. Based on the empirical results of this paper, the conclusion is in favor of the latter; the knowledge economy impacts all organizations.

Regarding the application of knowledge-intensive work practices, the following is concluded. Most and for all, the analyses show that organizations apply these practices in unison rather than as separate and isolated means of governing knowledge. This finding was mainly corroborated with the empirical result that these practices are positively related with each other and form a sufficiently reliable scale. Besides that, the finding that the knowledge intensity of the economy equally affects the underlying indicators, further strengthens the idea that organizations apply these practices as a bundle rather than focusing on each of these practices individually. This, then has implication for theories concerning the knowledge management of organizations. As was explained in the theory section, there are at least three theoretical approaches the enable to link the knowledge economy with the knowledge management practices of organizations, namely the dynamic capabilities approach, organizational learning theory and theories concerning the use of technology in organizations. Since each of these theories focuses on a specific part of these practices and establishing that these practices are applied in unison, it can be argued that integrating them is necessary to get a full theoretical account of organizations and their management in the knowledge economy. In other words, dynamic capabilities, organizational learning and the use of technology are all part of it. The present analysis provides the step toward an integrated model based on these three theoretical approaches. It should be noted, it was possible to link the chosen practices to these approaches, but that this is not to say that these are the only practices or theoretical notions that matter for understanding organizations in the knowledge economy. Nevertheless, since other practices could not be satisfactory covered in this analysis, this asks for additional research.

Additional research is needed in the following directions to overcome the empirical shortcomings of this paper (e.g. a reliance on cross-sectional data and analyzing secondary data). This first route to be explored relates to a move toward the knowledge economy. An underlying assumption in the literature is that economies are moving in the direction of increasing knowledge intensity. That this is the case is not disputed here. However, even though the current analysis points in the direction of changes in the structure and governance of organizations due to the spread to the knowledge economy, the cross-sectional data do not allow causal statements. Hence, longitudinal data are needed for future research to assess whether changes in the economy also translates into changes in organizations and their knowledge management. What is crucial in this respect is that the indicators for the knowledge economy as well as indicators for the knowledge intensity of the work practices are available for a sufficiently long period of time. One of the drawbacks may be that the focus will be somewhat narrower as this relaxes the possibility of constructing a longitudinal dataset. The second direction for future research means taking a different approach, namely a further advancement of the measurement of KIWPs. In this paper, it was possible to construct a scale based on secondary data enabling the assessment of the work practices. The next step is to strengthen this measurement. There are two points that need attention to achieve that. To begin, the indicators used here can be taken as the starting point to create an improved scale measuring KIWPs that are derived from the three theoretical approaches (dynamic capabilities, organizational learning and the use of technology). To develop these indicators, it is additionally required to assess whether the three theoretical approaches suffice for that purpose or that other theoretical approaches are necessary to include as well. The resulting measure should be richer in terms of content (covering KIWPs more broadly) as well as its theoretical base (and the possibility to generate an integrated model of these work practices). A third direction for future research concerns the fit between the environment and organizational practices. Whereas literature suggests that external fit should enhance organizational performance, it is still an open question whether this holds in the case of knowledge intensity of the economy.

Finally, some practical implications can be distilled from this paper. The first is that knowledge-intensive organizations and organizations in which knowledge intensity is increasing, are advised to look at the way in which they structure and govern their organization. Since autonomy, learning and technology are central feature of knowledge intense organizations, they could consider whether their practices are in place. In addition to that, it makes sense to have these work practices in bundles. Therefore, it makes sense to see whether autonomy, learning and technology are governed consistently in the organization. And, finally, as the results show that the economic environment matters for these practices, it is advised to have mechanisms to scan external development that are relevant for their KIWPs. The present study provides concrete ideas how to do that. Managers and consultants can use the measures of knowledge intensity and KIWPs to assess organizations. For example, they can ask the question whether the organization provides sufficient training to their workers, given the knowledge intensity of the environment in which it operates.

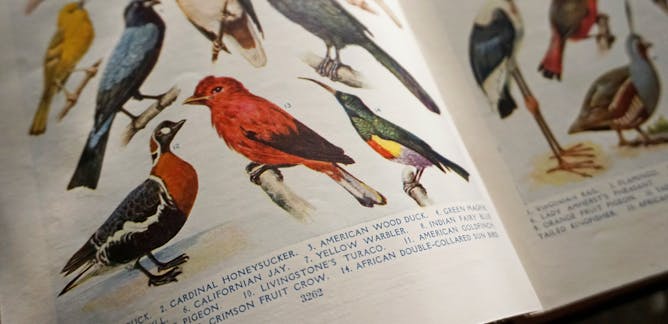

Research model

Correlation between Innovation Index and national mean of KIWPs

Descriptive statistics

Note(s): (a) Compared to the empty model

Source(s): European Company Survey (ECS) 2019, Eurostat, and European Innovation Scoreboard (EIS) 2020

20,672 establishments in 28 countries

Adler , P.S. ( 2001 ), “ Market, hierarchy, and trust: the knowledge economy and the future of capitalism ”, Organization Science , Vol. 12 No. 2 , pp. 215 - 234 .

Adler , P.S. , Kwon , S.W. and Heckscher , C. ( 2008 ), “ Perspective—professional work: the emergence of collaborative community ”, Organization Science , Vol. 19 No. 2 , pp. 359 - 376 .

Alvesson , M. ( 2004 ), Knowledge Work and Knowledge-Intensive Firms , OUP , Oxford .

Antonacopoulou , E.P. ( 2006 ), “ The relationship between individual and organizational learning: new evidence from managerial learning practices ”, Management Learning , Vol. 37 No. 4 , pp. 455 - 473 .

Aoyama , Y. and Castells , M. ( 2002 ), “ An empirical assessment of the informational society: employment and occupational structures of G-7 countries, 1920-2000 ”, International Labour Review , Vol. 141 , p. 123 .

Argote , L. ( 2011 ), “ Organizational learning research: past, present and future ”, Management Learning , Vol. 42 No. 4 , pp. 439 - 446 .

Argote , L. and Miron-Spektor , E. ( 2011 ), “ Organizational learning: from experience to knowledge ”, Organization Science , Vol. 22 No. 5 , pp. 1123 - 1137 .

Bahar , D. ( 2019 ), “ Measuring knowledge intensity in manufacturing industries: a new approach ”, Applied Economics Letters , Vol. 26 No. 3 , pp. 187 - 190 .

Barney , J. ( 1991 ), “ Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage ”, Journal of Management , Vol. 17 No. 1 , pp. 99 - 120 .

Baskerville , R. and Dulipovici , A. ( 2006 ), “ The theoretical foundations of knowledge management ”, Knowledge Management Research and Practice , Vol. 4 No. 2 , pp. 83 - 105 .

Berg , S.A. and Chyung , S.Y. ( 2008 ), “ Factors that influence informal learning in the workplace ”, Journal of Workplace Learning , Vol. 20 No. 4 , pp. 229 - 244 .

Berta , W. , Cranley , L. , Dearing , J.W. , Dogherty , E.J. , Squires , J.E. and Estabrooks , C.A. ( 2015 ), “ Why (we think) facilitation works: insights from organizational learning theory ”, Implementation Science , Vol. 10 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 13 .

Bickel , R. ( 2007 ), Multilevel Analysis for Applied Research: It's Just Regression! , Guilford Press , New York .

Bishop , J.H. ( 1996 ), What We Know about Employer-Provided Training: A Review of the Literature , CAHRS , Ithaca .

Boyd , R. and Holton , R.J. ( 2018 ), “ Technology, innovation, employment and power: does robotics and artificial intelligence really mean social transformation? ”, Journal of Sociology , Vol. 54 No. 3 , pp. 331 - 345 .

Brynjolfsson , E. , Rock , D. and Syverson , C. ( 2018 ), “ Artificial intelligence and the modern productivity paradox: a clash of expectations and statistics ”, in Agrawal , A. , Gans , J. and Goldfarb , A. (Eds), The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda , University of Chicago Press , Chicago , pp. 23 - 57 .

Burris , B.H. ( 1998 ), “ Computerization of the workplace ”, Annual Review of Sociology , Vol. 24 , pp. 141 - 157 .

Calantone , R.J. , Cavusgil , S.T. and Zhao , Y. ( 2002 ), “ Learning orientation, firm innovation capability, and firm performance ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 31 No. 6 , pp. 515 - 524 .

Carlsson , B. ( 2004 ), “ The digital economy: what is new and what is not? ”, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics , Vol. 15 No. 3 , pp. 245 - 264 .

Cerny , P.G. ( 1999 ), “ Globalization and the erosion of democracy ”, European Journal of Political Research , Vol. 36 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 26 .

Crossan , M.M. and Apaydin , M. ( 2010 ), “ A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: a systematic review of the literature ”, Journal of Management Studies , Vol. 47 No. 6 , pp. 1154 - 1191 .

Davis , F.D. ( 1986 ), A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results , MIT , Cambridge .

European Commission ( 2020 ), “ EIS 2020 methodology report ”, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/41861 .

Felin , T. and Powell , T.C. ( 2016 ), “ Designing organizations for dynamic capabilities ”, California Management Review , Vol. 58 No. 4 , pp. 78 - 96 .

Fernández-Macías , E. ( 2012 ), “ Job polarization in Europe? Changes in the employment structure and job quality, 1995-2007 ”, Work and Occupations , Vol. 39 No. 2 , pp. 157 - 182 .

Ferreira , J. , Mueller , J. and Papa , A. ( 2018 ), “ Strategic knowledge management: theory, practice and future challenges ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 24 No. 2 , pp. 121 - 126 .

Foss , N.J. ( 2005 ), Strategy, Economic Organization, and the Knowledge Economy: The Coordination of Firms and Resources , Oxford University Press , Oxford .

Foster , A.D. and Rosenzweig , M.R. ( 2010 ), “ Microeconomics of technology adoption ”, Annual Review of Economy , Vol. 2 No. 1 , pp. 395 - 424 .

Grandori , A. ( 2016 ), “ Knowledge intensive work and the (re) emergence of democratic governance ”, Academy of Management Perspectives , Vol. 30 No. 2 , pp. 167 - 181 .

Greenwood , R. , Hinings , C.R. and Whetten , D. ( 2014 ), “ Rethinking institutions and organizations ”, Journal of Management Studies , Vol. 51 No. 7 , pp. 1206 - 1220 .

Hodgson , G.M. ( 2016 ), “ The future of work in the twenty-first century ”, Journal of Economic Issues , Vol. 50 No. 1 , pp. 197 - 216 .

Hox , J.J. , Moerbeek , M. and Van de Schoot , R. ( 2017 ), Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications , Routledge , New York/London .

Jacobs , R.L. ( 2017 ), “ Knowledge work and human resource development ”, Human Resource Development Review , Vol. 16 No. 2 , pp. 176 - 202 .

Jiménez-Jiménez , D. and Sanz-Valle , R. ( 2011 ), “ Innovation, organizational learning, and performance ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 64 No. 4 , pp. 408 - 417 .

Kalleberg , A.L. and Mouw , T. ( 2018 ), “ Occupations, organizations, and intragenerational career mobility ”, Annual Review of Sociology , Vol. 44 , pp. 283 - 303 .

Kapoor , M. and Aggarwal , V. ( 2020 ), “ Tracing the economics behind dynamic capabilities theory ”, International Journal of Innovation Science , Vol. 12 No. 2 , pp. 187 - 201 .

Kelloway , E.K. and Barling , J. ( 2000 ), “ Knowledge work as organizational behavior ”, International Journal of Management Reviews , Vol. 2 No. 3 , pp. 287 - 304 .

Khadir-Poggi , Y. and Keating , M. ( 2013 ), “ Understanding knowledge intensive organisations within knowledge-based economies: biases and challenges ”, International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development , Vol. 4 No. 1 , pp. 64 - 78 .

Koster , F. ( 2021 ), “ Organisational antecedents of innovation performance: an analysis across 32 European countries ”, International Journal of Innovation Management , Vol. 25 No. 4 , 2150037 , doi: 10.1142/S1363919621500377 .

Koster , F. and Benda , L. ( 2020 ), “ Explaining employer provided training ”, Journal of Social Policy Research , Vol. 66 No. 3 , pp. 237 - 260 .

Lee , J. ( 2015 ) (Ed.), The Impact of ICT on Work , Springer , Singapore .

Levitt , B. and March , J.G. ( 1988 ), “ Organizational learning ”, Annual Review of Sociology , Vol. 14 No. 1 , pp. 319 - 338 .

Makani , J. and Marche , S. ( 2010 ), “ Towards a typology of knowledge-intensive organizations: determinant factors ”, Knowledge Management Research and Practice , Vol. 8 No. 3 , pp. 265 - 277 .

Manville , B. and Ober , J. ( 2003 ), “ Beyond empowerment: building a company of citizens ”, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 81 No. 1 , pp. 48 - 53 .

Martinaitis , Ž. , Christenko , A. and Antanavičius , J. ( 2020 ), “ Upskilling, deskilling or polarisation? Evidence on change in skills in Europe ”, Work, Employment and Society , Online ready , doi: 10.1177/0950017020937934 .

Neef , D. ( 1999 ), “ Making the case for knowledge management: the bigger picture ”, Management Decision , Vol. 37 No. 1 , pp. 72 - 78 .

Nurunnabi , M. ( 2017 ), “ Transformation from an oil-based economy to a knowledge-based economy in Saudi Arabia: the direction of Saudi vision 2030 ”, Journal of the Knowledge Economy , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 536 - 564 .

Obeso , M. , Hernández-Linares , R. , López-Fernández , M.C. and Serrano-Bedia , A.M. ( 2020 ), “ Knowledge management processes and organizational performance: the mediating role of organizational learning ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 24 No. 8 , pp. 1859 - 1880 .

Paton , S. ( 2013 ), “ Introducing Taylor to the knowledge economy ”, Employee Relations , Vol. 35 No. 1 , pp. 20 - 38 .

Peugh , J.L. ( 2010 ), “ A practical guide to multilevel modeling ”, Journal of School Psychology , Vol. 48 No. 1 , pp. 85 - 112 .

Powell , W.W. and Snellman , K. ( 2004 ), “ The knowledge economy ”, Annual Review of Sociology , Vol. 30 , pp. 199 - 220 .

Pyöriä , P. ( 2005 ), “ The concept of knowledge work revisited ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 9 No. 3 , pp. 116 - 127 .

Sakamoto , A. , Kim , C. and Tamborini , C.R. ( 2018 ), “ Changes in occupations, jobs, and skill polarization ”, in Hoffman , B.J. , Shoss , M.K. and Wegman , L.A. (Eds), The Cambridge Handbook on the Changing Nature of Work , Cambridge University Press , Cambridge , pp. 133 - 153 .

Schwab , K. ( 2016 ), The Fourth Industrial Revolution , Crown Publishing , New York .

Snijders , T.A. and Bosker , R.J. ( 2011 ), Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling , Sage , London .

Struik , M.H.L. , Koster , F. , Schuit , A.J. , Nugteren , R. , Veldwijk , J. and Lambooij , M.S. ( 2014 ), “ The preferences of users of electronic medical records in hospitals: quantifying the relative importance of barriers and facilitators of an innovation ”, Implementation Science , Vol. 9 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 11 .

Swedberg , R. ( 2005 ), “ Towards an economic sociology of capitalism ”, L'Année Sociologique , Vol. 55 No. 2 , pp. 419 - 449 .

Switzer , C. ( 2008 ), “ Time for change: empowering organizations to succeed in the knowledge economy ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 12 No. 2 , pp. 18 - 28 .

Teece , D.J. ( 2007 ), “ Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance ”, Strategic Management Journal , Vol. 28 No. 13 , pp. 1319 - 1350 .

Teece , D.J. ( 2014 ), “ The foundations of enterprise performance: dynamic and ordinary capabilities in an (economic) theory of firms ”, Academy of Management Perspectives , Vol. 28 No. 4 , pp. 328 - 352 .

Ullah , I. and Narain , R. ( 2020 ), “ Achieving mass customization capability: the roles of flexible manufacturing competence and workforce management practices ”, Journal of Advances in Management Research , Vol. 18 No. 2 , pp. 273 - 296 .

Valeri , M. ( 2021 ), Organizational Studies: Implications for the Strategic Management , Springer Nature , Cham .

Van Houten , G. and Russo , G. ( 2020 ), European Company Survey 2019: Workplace Practices Unlocking Employee Potential , Eurofound , Dublin .

Wensing , M. and Grol , R. ( 2019 ), “ Knowledge translation in health: how implementation science could contribute more ”, BMC Medicine , Vol. 17 No. 1 , p. 88 .

Wood , S. ( 1987 ), “ The deskilling debate, new technology and work organization ”, Acta Sociologica , Vol. 30 No. 1 , pp. 3 - 24 .

Wu , Y. ( 2015 ), “ Organizational structure and product choice in knowledge intensive firms ”, Management Science , Vol. 61 No. 8 , pp. 1830 - 1848 .

Young-Hyman , T. ( 2017 ), “ Cooperating without co-laboring: how formal organizational power moderates cross-functional interaction in project teams ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 62 No. 1 , pp. 179 - 214 .

Zack , M.H. ( 1999 ), “ Managing codified knowledge ”, Sloan Management Review , Vol. 40 No. 4 , pp. 45 - 58 .

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Articles on Knowledge economy

Displaying all articles.

Encyclopedia Britannica once published a catalogue of humanity’s ‘102 Great Ideas’ – and it created more questions than answers

Mike Ryder , Lancaster University

Jobs deficit drives army of daily commuters out of Western Sydney

Phillip O'Neill , Western Sydney University

As big cities get even bigger, some residents are being left behind

Sajeda Tuli , University of Canberra and Shakil Bin Kashem , University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Digital training can help supervisors lift PhD output

Jan Botha , Stellenbosch University ; Gabriele Vilyte , Stellenbosch University , and Miné de Klerk , Stellenbosch University

New creatives are remaking Canberra’s city centre, but at a social cost

Richard Hu , University of Canberra and Sajeda Tuli , University of Canberra

What it takes for Indonesia to create, share and use knowledge to grow its economy

Arnaldo Pellini , Tampere University

How the SKA telescope is boosting South Africa’s knowledge economy

Nishana Bhogal , University of Cape Town

Science in Africa: homegrown solutions and talent must come first

Alan Christoffels , University of the Western Cape

Why big projects like the Adani coal mine won’t transform regional Queensland

John Cole , University of Southern Queensland

Why openness, not technology alone, must be the heart of the digital economy

Rufus Pollock , University of Cambridge

The Knowledge City Index: Sydney takes top spot but Canberra punches above its weight

Lawrence Pratchett , University of Canberra ; Michael James Walsh , University of Canberra ; Richard Hu , University of Canberra , and Sajeda Tuli , University of Canberra

How access to knowledge can help universal health coverage become a reality

Stevan Bruijns , University of Cape Town

From ‘white flight’ to ‘bright flight’ – the looming risk for our growing cities

Jason Twill , University of Technology Sydney

When ‘innovation’ fails to fix our finances

Usman W. Chohan , UNSW Sydney

Queensland’s budget puts it back on track to be a smart state

Chris Salisbury , The University of Queensland

Budget week reveals an appetite for government but not to govern

Travers McLeod , The University of Melbourne

Measuring the value of science: it’s not always about the money

Rod Lamberts , Australian National University

The East-West Link is dead – a victory for 21st-century thinking

Peter Newman , Curtin University

African Americans place a great value in postsecondary education

Kinder Institute

Related Topics

- Cities & Policy

- Developing a knowledge economy

- Global perspectives

- Knowledge workers

- South Africa

- Tony Abbott

- Urban planning

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Operations Manager

Senior Education Technologist

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Top contributors.

Fulbright Scholar, Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis, University of Canberra

Professor, University of Canberra

Pro Vice-Chancellor (Engagement), University of Southern Queensland

Honorary Fellow in the School of Social and Political Sciences, The University of Melbourne

Innovation Fellow and Senior Lecturer, School of Architecture, University of Technology Sydney

Professor, Centre for Research on Evaluation, Science and Technology (CREST), Stellenbosch University

Director, Centre for Western Sydney, Western Sydney University

Lecturer, The University of Queensland

Associate Professor in Social Sciences, University of Canberra

Economist, UNSW Sydney

Dean of Business, Government and Law, University of Canberra

Senior lecturer in the Division of Emergency Medicine, University of Cape Town

Member of EduKnow Research Group at the University of Tampere (Finland), Tampere University

Associate Fellow, University of Cambridge

Senior Lecturer: Entrepreneurship Stellenbosch Business School, University of Cape Town

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- Open access

- Published: 20 January 2022

The role of knowledge economy in Asian business

- Shumaila Zeb 1

Future Business Journal volume 8 , Article number: 1 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

5241 Accesses

8 Citations

Metrics details

The study examines the role of the knowledge economy (KE) in Asian businesses in 45 countries for 2000–2019. KE indicators include education, economic incentives, innovation, institutional regime, and information and communication technology. The business indicators used in the study are starting, doing, and closing business. The empirical analysis is carried out by applying principal component analysis (PCA) and instrument variable panel fixed effects estimator. The results proved that the KE indicators are essential to improve businesses in Asia. They help the economies to boost their business sector and help to fight against poverty and unemployment.

Introduction

For the last two decades, economies of the world have been striving to evolve themselves to become knowledge-based economies (KBE). KBE relies less on traditional sources like land, labor, and capital for asset creation, wealth maximization, and economic prosperity [ 6 , 7 ]. In today’s world, the formation of new knowledge, research and development (R&D) to promote innovation and technological advancements to achieve prosperity is the key to success [ 47 , 66 ]. Similarly, the governments’ economic incentive based on new knowledge creation stimulates economic development, favors entrepreneurship, and increases employment opportunities in the economy. These existing trends, based on the creation and dissemination of new knowledge, are welcomed in developing and emerging economies. These are considered as the backbone of a KBE [ 65 ]. Similarly, knowledge economy (KE) is an expression used in developed economies to explain critical factors of knowledge creation and its usage as a means of production to gain competitive advantage and enhance efficiency and productivity.

KE and KBE’s roots are originated from different economic theories. Like, Neo classical economics and idea of increase returns to scale led toward knowledge-based economy. Different theories like endogenous growth theory (Romer 1990), organizational theory [ 62 ], and the theory of transaction cost [ 38 ] laid foundation of knowledge-based economy. Indeed, knowledge is nowadays considered as a driving force for enhancing productivity, promoting economic development, and increasing economic performance. KE does not only refer to employing new means for the production of goods and services but it also requires a complete novel paradigm. This new paradigm involves innovation, new technology, and high skilled human force in every sector of the economy.

Innovation is considered as one of the potential determinants of economic growth and prosperity in the developed world. It is one of the important pillars of KE. However, it is observed that the capacity of innovation remains less in most Asian and African economies [ 19 ] and [ 5 ]. Globalization is another critical factor, which also plays an essential role in the KBE. The globalization of new technology creates more opportunities for development and growth in the developing and emerging economies [ 48 ]. However, the situation is a bit different in certain economies including Asian economies. They need to invest more in human capital and infrastructure to accommodate and sustain high technology-oriented ventures and industries. Therefore, developing countries need to cooperate more with the developed world to increase their competitiveness and international trade goals [ 32 , 39 , 65 ].

In the light of the above, there are various studies on the relevance of KBE and KE. Several studies have been conducted on the relevance of human capital. Examples of these studies include Schultz [ 58 ] and the creation of growth models by Romer [ 55 ] and Lucas [ 41 ] made knowledge and human capital significant factors for growth. The roots of KE go back to the industrial revolution from the 1760s to the 1850s, when technological innovation boosted economic expansion [ 36 ]. Traditionally, there was more dependence on labor and capital as the primary sources of economic growth and development. However, the past two decades witnessed the vital role of KE in developed and developing economies [ 10 ]. No doubt, Asian countries are self-sufficient in the labor force [ 43 ]. However, now trends have changed due to technological advancements in producing goods and services. Asian economies contribute significantly in the GDP of the world. As per the income distribution, few Asian economies are at middle-income levels. Therefore, the Asian economies need to develop a KBE culture to enter into high-income levels like other developed countries. They must devise policies to improve their information infrastructure, communication and information, and human capital to become successful KBE [ 52 , 52 ].