Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

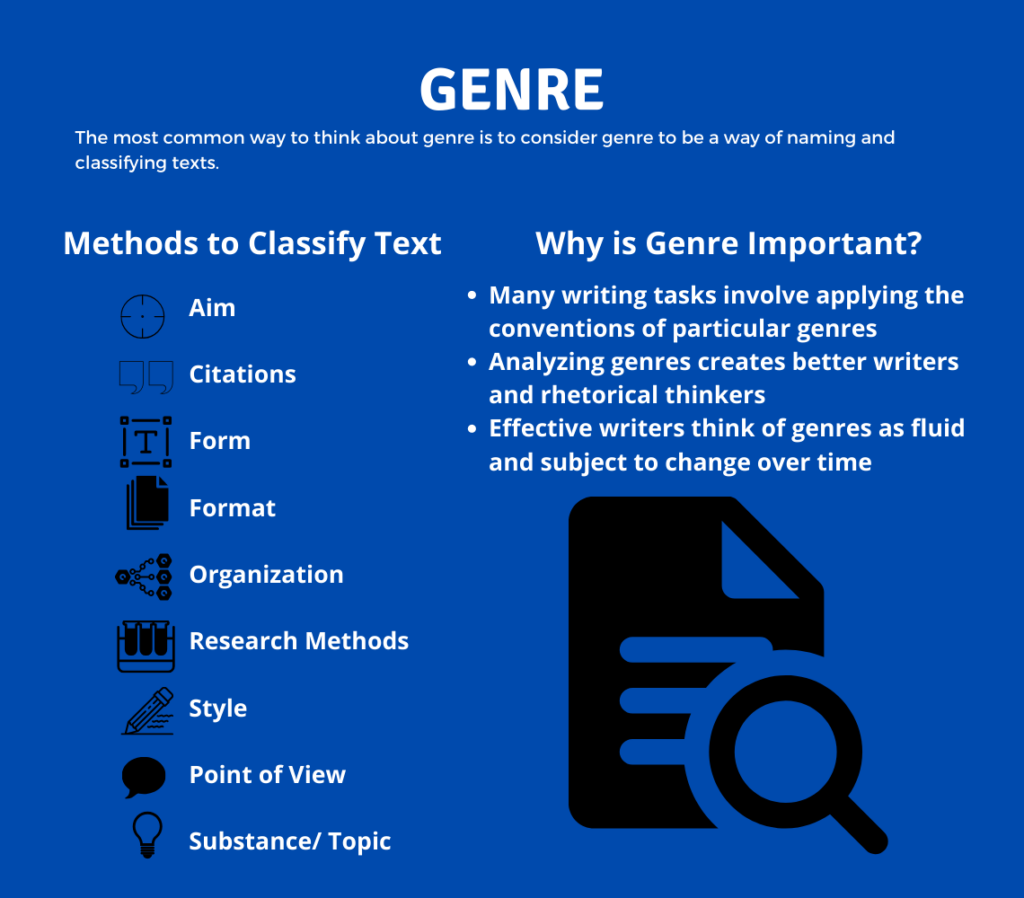

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions about what constitutes a knowledge claim or authoritative research method; the discourse conventions of a particular discourse community . This article reviews research and theory on 6 different definitions of genre, explains how to engage in genre analysis, and explores when during the writing process authors should consider genre conventions. Develop your genre knowledge so you can discern which genres are appropriate to use—and when you need to remix genres to ensure your communications are both clear and persuasive.

Genre Definition

G enre may refer to

- by the aim of discourse

- by discourse conventions

- by discourse communities

- by a type of technology

- a social construct

- the situated actions of writers and readers

- the situated practices and epistemological assumptions of discourse communities

- a form of literacy .

Related Concepts: Deductive Order, Deductive Reasoning, Deductive Writing ; Interpretation ; Literacy ; Mode of Discourse ; Organizational Schema; Rhetorical Analysis ; Rhetorical Reasoning ; Voice ; Tone ; Persona

Genre Knowledge – What You Need to Know about Genre

Genre plays a foundational role in meaning-making activities, including interpretation , reading , writing, and speaking.

In order to communicate with clarity , writers and speakers need to understand the expectations of their audiences regarding the appropriate content, style, design, citation style, and medium. Genres facilitate communication between writers and readers, authors and audiences, and writers/speakers and readers/listeners. Genre and genre knowledge increase the likelihood of clarity in communications .

Writers use their knowledge of genre to jumpstart composing: a genre presumes a formula for how to organize a document, how to develop and present a research question , how to substantiate claims–and more. For writers, genres are an efficient way to respond to recurring situations . Rather than reinvent the wheel every time, writers save time by considering how others have responded in the same or a similar situation . Genres are like big Lego chunks that can be re-used to start a new Lego creation that is similar to past Lego creations you’ve created.

In turn, readers use genres to more quickly scan information . Because they know the formula, because they share with the author as members of a discourse community a common language, common topoi , archive , canonical texts , and expectations about what to say and how to say it in, they can skip through a document and grab the highlights.

Six Definitions of Genre

1. genre refers to a naming and categorization scheme for sorting types of writing.

“… [L]et me define “genres” as types of writing produced every day in our culture, types of writing that make possible certain kinds of learning and social interaction.” (Cooper 1999, p. 25)

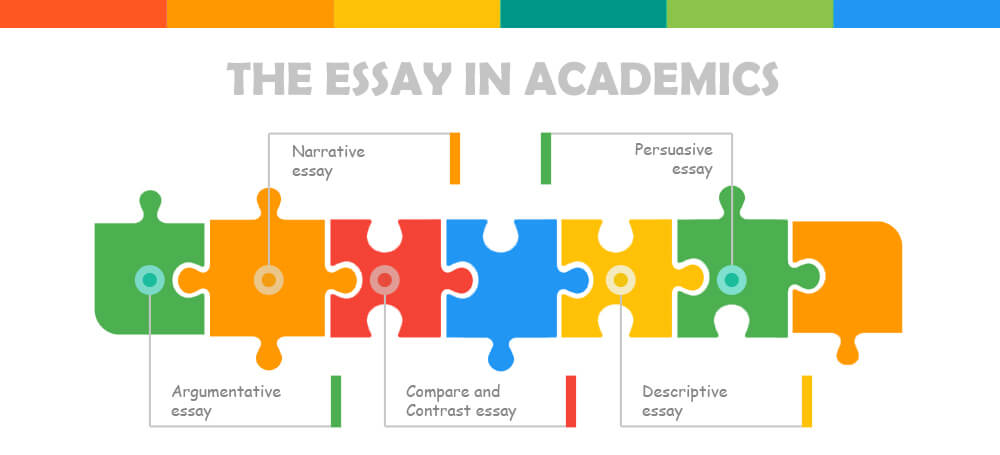

G enre refers to types of writing, art, and musical compositions. For instance

- alphabetical texts may be categorized as Expository Writing, Descriptive Writing, Persuasive Writing, or Narrative Writing .

- movies may be categorized as Action & Adventure, Children & Family Movies, Comedies, Documentaries, Dramas.

- music may be categorized as Artist, Album, Country, New Age, Jazz, and so on.

There are many different ways to define and sort genres. For instance, genres may defined based on their content, organization, and style. Or, genres may be defined and categorized based on

- Examples: Drama, Fable, Fairy Tale, etc.

- Move 1 Establish a territory

- Move 2 Establish a niche

- Move 3 Occupy the niche (Swales and Feak 2004)

- A research article written for a scientific audience most likely uses some for of an “IMRAC structure”–i.e., an introduction, methods, results, and conclusion

- An article in the sciences and social sciences would use APA style for citations

- by the type of technology used by the sender and the receiver of the information.

2. Genre is a Social Construct

“Genres are conventions, and that means they are social – socially defined and socially learned.” (Bomer 1995:112) “… [A] genre is a socially standard strategy, embodied in a typical form of discourse, that has evolved for responding to a recurring type of rhetorical situation.” (Coe and Freedman 1998, p. 137)

Genre is more than a way to sort types of texts by discourse aim or some other classification scheme: Genres are social, cultural, rhetorical constructs. For example,

- writers draw on their expectations about what they believe their readers will know about a genre–how it’s structured ( what it’s formula is! ) and when it’s socially useful.

- readers draw on their past experiences as readers and as members of particular discourse communities. They hold expectations about the appropriate use of particular textual patterns in specific situations.

Or, consider this example: in the social situation of seeking a job, an applicant knows from the archive , the culture, the conversations about job seeking , that they are expected to create a letter of application and a résumé . More than that, they know the point of view they are to take as well as the tone –and more.

Writers and readers develop textual expectations tacitly — by reading and speaking with others — and formally: by studying genres in school. Students are inculcated in textual practices of particular disciplines (e.g., engineering or biology) as part of their academic and professional training.

3. Genres Reflect the Situated Actions of Writers and Readers

“a rhetorically sound definition of genre must be centered not on the substance or the form of discourse but on the action it is used to accomplish” (Miller 1984, p. 151)

Carolyn Miller (1984) extends this social view of genre in her article Genre as Social Action by operationalizing genre from a rhetorical perspective. Miller asserts genres are the embodiment of situated actions. In her rhetorical model of genre, Miller theorizes

- writers enter a rhetorical situation guided by aims (e.g., to persuade users to support a proposal ). The writer assesses the rhetorical situation (e.g., considers audience , purpose , voice , style ) to more fully understand the situation and the motives of stakeholders.

- For instance, a researcher could dip into a research study seeking empirical support for a claim . A graphic designer could open a magazine looking for layout ideas.

4. Genres Embody the Situated Practices and Values of Discourse Communities

“Genre not only allows the scholar to report her research, but its conventions and constraints also give structure to the actual investigations she is reporting” (Joliffe 1996, p. 283).

The textual practices of discourse communities reflect the epistemological assumptions of practitioners regarding what constitutes an appropriate rhetorical stance , research method , or knowledge claim . For instance, a scientist doesn’t insert their subjective opinions into the methods section of a lab report because they understand their audience expect them to follow empirical methods and an academic writing prose style

Academic documents, business documents, legal briefs, medical records—these sorts of texts are grounded in the situated practices of members of particular discourse communities . Practitioners — e.g., scientists in a research lab, accountants in an accountancy firm, or engineers in an engineering firm— share assumptions, conventions, and values about how documents should be researched, written, and shared. Discourse communities develop unique ways of communicating with one another. Their daily work, their situated practices, reflect their assumptions about what constitutes knowledge , appropriate research methods, or authoritative sources . Genres reflect the values of communities . They provide a roadmap to rhetors for how to engage with community members in expected ways. (For more on this, see Research ).

5. Genre Knowledge Constitutes a Form of Literacy

Genres are created in the forge of recurring rhetorical situations . Particular exigencies call for particular genres . Applying for a job? Well, then, a résumé and cover letter are called for. Trying to report on an experiment in organic chemistry? Well, then a lab report is due. Thus, being able to recognize which genre is called for by a particular exigency, a particular call to write , is a form of literacy : If you’re unfamiliar with a genre and your reader’s expectations for that genre, then you may as well be from mars.

Genre Analysis – How to Engage in Genre Analysis

When we enter a rhetorical situation , guided by a sense of purpose like an explorer clutching a compass, we invariably compare the present situation to past situations. We reflect on whether we have read the work of other writers who have also addressed the same or somewhat equivalent rhetorical situation , the topic, we’re facing. If you have a proposal due, for instance, it helps to look at some samples of past proposals–particularly if you can access proposals funded by the organization from whom you are seeking support.

For genre theorists, these are acts of typification –a moment where we typify a situation: “What recurs is not a material situation (a real, objective, factual event) but our construal of a type” (Miller 157).

In other words, genres are conceptual tools, ways we relate situated actions to recurring rhetorical situations. When first entering a situation, we assess whether this is a recurring rhetorical situation and whether past responses will work equally well for this new situation—or if we’ll need to tweak our response, our text, a bit. For instance, if applying for a job, you might look at previous drafts of job application letters

Genres are like prefabricated Lego pieces that we can use to jumpstart a new Lego masterpiece.

We abbreviate the experiences of our lives by creating idealized versions–i.e., metatexts that capture the gist of those experiences. Or, we access the archive , or our memory of the archive, and seek exemplars — canonical texts , the works of others who addressed similar exigencies , similar rhetorical situations.

To make this less abstract, let’s consider what might go through the mind of a writer who wants to write a New Year’s party invitation. If the writer were an American, they might reflect on the ritual ball drop in Times Square in New York City. They might recall past texts associated with New Year’s celebrations (party invitations, menus, greeting cards, party hats, songs, and resolutions) as well as rituals (fireworks, champagne, or a New Year’s kiss). They might even conduct an internet search for New Year’s Eve party invitations or download a party template from Google Docs or Microsoft Word. Over time, that writer’s sense of the ideal New Year’s party invitation becomes typified —a condensation of the texts and rituals and stories.

Because we tend to have unique experiences and because we have different personalities, motives, and aims , our sense of an ideal New Year’s Eve invitation might be somewhat different from those of our friends and family—or even the broader society. Rather than assuming it’s a good time to go out and party and dance, you may think it’s a good time to stay home and meditate. After all, as writers, we experience events, texts and rituals subjectively and uniquely. Thus, we don’t all have the same ideas about what should happen at a New Year’s party or even what the best party invite should look like. Still, when we sit down to write a party invitation for New Year’s Eve, this is a reoccurring situation for us, and we cannot help but be influenced by all of the past invitations we’ve received, what our friends and loved ones have recommended, and what we see online for party invite templates (if we engage in strategic searching).

Sample Genre Analysis

Below are some sample questions and perspectives you may consider when engaging in Genre Analysis.

1. When During Composing Should I Engage in Genre Analysis?

Early in the writing process — during prewriting — you are wise to identify the genre your audience expects you to follow. Then, engage in strategic searching to identify exemplars and canonical texts that typify the genre.

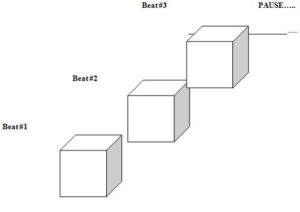

Next, you might begin your first draft by outlining the sections of discourse associated with the genre you’re writing in. For example, if you are writing an Aristotelian argument for a school paper, you might jumpstart your first draft by listing the rhetorical moves associated with Aristotelian argument as your subject headings:

- Introduce the Topic

- Introduce Claims

- Appeal to Ethos & Persona to Establish an Appropriate Tone

- Appeal to Emotions

- Appeal to Logic

- Present Counterarguments

- Search for a Compromise and Call for a Higher Interest

- Speculate About Implications in Conclusions

That said, it’s important to note that some people prefer not to think about genre at all during drafting. Research in writing studies has found that there is no single, ideal writing process . Instead, our personalities, rhetorical stance , openness to information , rhetorical situation (e.g., contextual factors such as time available and access to information )–and more — influence how we compose.

You may not want to think much about genre when

- You’re the type of writer who needs to write your way to meaning. For you, writing is rewriting

- Your audience may have specific expectations in mind that you haven’t addressed. You may be unfamiliar with how other writers have addressed that situation in the past. You may lack access to the information you need to research how others typically respond to the rhetorical situation you are facing

In summary, thinking about genre and reading the works of other writers addressing similar rhetorical situations will probably help you jumpstart a writing project. However, at the end of the day, only you can decide how to work with genres of discourse.

Coe, R., & Freedman, A. (1998). Genre theory: Australian and North American approaches. In M. L. Kennedy (ed), Theorizing composition: A critical sourcebook of theory and scholarship in contemporary composition studies (p p. 136-147). Greenwood Press.

Joliffe, D. A. (1996). Genre. In T. Enos (ed), Encyclopedia of rhetoric and composition: Communication from ancient times to the information age (pp . 279-284). Garland Publishing.

Miller, R. (1984). Genre as social action. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 70 , 151-167.

Swales, J., & C. Feak (2004). Academic writing for graduate students: Essential tasks and skills . University of Michigan Press

Related Articles:

Annotated bibliography.

Argument - Argumentation

Autobiography, conclusions - how to write compelling conclusions, cover letter, letter of transmittal.

Dialogue - The Difficulty of Speaking

Executive summary, formal reports, infographics, instructions & processes.

Introductions

Presentations, problem definition, progress reports, recommendation reports, research proposal, research protocol.

Reviews and Recommendations

Subjects & concepts, team charter, suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Joseph M. Moxley

Argument is an iterative process that informs humankind’s search for meaning. Learn about different types of argumentation (Aristotelian Argument; Rogerian Argument; Toulmin Argument) so you can identify the best way...

- Jennifer Janechek

- David Kranes

- Angela Eward-Mangione , Katherine McGee

- Joseph M. Moxley , Julie Staggers

Lorem Ipsum has been the industry’s standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

Definition of Genre

Genre originates from the French word meaning kind or type. As a literary device, genre refers to a form, class, or type of literary work. The primary genres in literature are poetry, drama / play , essay , short story , and novel . The term genre is used quite often to denote literary sub-classifications or specific types of literature such as comedy , tragedy , epic poetry, thriller , science fiction , romance , etc.

It’s important to note that, as a literary device, the genre is closely tied to the expectations of readers. This is especially true for literary sub-classifications. For example, Jane Austen ’s work is classified by most as part of the romance fiction genre, as demonstrated by this quote from her novel Sense and Sensibility :

When I fall in love, it will be forever.

Though Austen’s work is more complex than most formulaic romance novels, readers of Austen’s work have a set of expectations that it will feature a love story of some kind. If a reader found space aliens or graphic violence in a Jane Austen novel, this would undoubtedly violate their expectations of the romantic fiction genre.

Difference Between Style and Genre

Although both seem similar, the style is different from the genre. In simple terms, style means the characters or features of the work of a single person or individual. However, the genre is the classification of those words into broader categories such as modernist, postmodernist or short fiction and novels, and so on. Genres also have sub-genre, but the style does not have sub-styles. Style usually have further features and characteristics.

Common Examples of Genre

Genres could be divided into four major categories which also have further sub-categories. The four major categories are given below.

- Poetry: It could be categorized into further sub-categories such as epic, lyrical poetry, odes , sonnets , quatrains , free verse poems, etc.

- Fiction : It could be categorized into further sub-categories such as short stories, novels, skits, postmodern fiction, modern fiction, formal fiction, and so on.

- Prose : It could be further categorized into sub-genres or sub-categories such as essays, narrative essays, descriptive essays, autobiography , biographical writings, and so on.

- Drama: It could be categorized into tragedy, comedy, romantic comedy, absurd theatre, modern play, and so on.

Common Examples of Fiction Genre

In terms of literature, fiction refers to the prose of short stories, novellas , and novels in which the story originates from the writer’s imagination. These fictional literary forms are often categorized by genre, each of which features a particular style, tone , and storytelling devices and elements.

Here are some common examples of genre fiction and their characteristics:

- Literary Fiction : a work with artistic value and literary merit.

- Thriller : features dark, mysterious, and suspenseful plots.

- Horror : intended to scare and shock the reader while eliciting a sense of terror or dread; may feature scary entities such as ghosts, zombies, evil spirits, etc.

- Mystery : generally features a detective solving a case with a suspenseful plot and slowly revealing information for the reader to piece together.

- Romance : features a love story or romantic relationship; generally lighthearted, optimistic, and emotionally satisfying.

- Historical : plot takes place in the past with balanced realism and creativity; can feature actual historical figures, events, and settings.

- Western : generally features cowboys, settlers, or outlaws of the American Old West with themes of the frontier.

- Bildungsroman : story of a character passing from youth to adulthood with psychological and/or moral growth; the character becomes “educated” through loss, a journey, conflict , and maturation.

- Science Fiction : speculative stories derived and/or inspired by natural and social sciences; generally features futuristic civilizations, time travel, or space exploration.

- Dystopian : sub-genre of science fiction in which the story portrays a setting that may appear utopian but has a darker, underlying presence that is problematic.

- Fantasy : speculative stories with imaginary characters in imaginary settings; can be inspired by mythology or folklore and generally include magical elements.

- Magical Realism : realistic depiction of a story with magical elements that are accepted as “normal” in the universe of the story.

- Realism : depiction of real settings, people, and plots as a means of approaching the truth of everyday life and laws of nature.

Examples of Writers Associated with Specific Genre Fiction

Writers are often associated with a specific genre of fictional literature when they achieve critical acclaim, public notoriety, and/or commercial success with readers for a particular work or series of works. Of course, this association doesn’t limit the writer to that particular genre of fiction. However, being paired with a certain type of literature can last for an author’s entire career and beyond.

Here are some examples of writers that have become associated with specific fiction genre:

- Stephen King: horror

- Ray Bradbury : science fiction

- Jackie Collins: romance

- Toni Morrison: black feminism

- John le Carré: espionage

- Philippa Gregory: historical fiction

- Jacqueline Woodson: racial identity fiction

- Philip Pullman: fantasy

- Flannery O’Connor: Southern Gothic

- Shel Silverstein: children’s poetry

- Jonathan Swift : satire

- Larry McMurtry: western

- Virginia Woolf: feminism

- Raymond Chandler: detective fiction

- Colson Whitehead: Afrofuturism

- Gabriel García Márquez : magical realism

- Madeleine L’Engle: children’s fantasy fiction

- Agatha Christie : mystery

- John Green : young adult fiction

- Margaret Atwood: dystopian

Famous Examples of Genre in Other Art Forms

Most art forms feature genre as a means of identifying, differentiating, and categorizing the many forms and styles within a particular type of art. Though there are many crossovers when it comes to genre and no finite boundaries, most artistic works within a particular genre feature shared patterns , characteristics, and conventions.

Here are some famous examples of genres in other art forms:

- Music : rock, country, hip hop, folk, classical, heavy metal, jazz, blues

- Visual Art : portrait, landscape, still life, classical, modern, impressionism, expressionism

- Drama : comedy, tragedy, tragicomedy , melodrama , performance, musical theater, illusion

- Cinema : action, horror, drama, romantic comedy, western, adventure , musical, documentary, short, biopic, fantasy, superhero, sports

Examples of Genre in Literature

As a literary device, the genre is like an implied social contract between writers and their readers. This does not mean that writers must abide by all conventions associated with a specific genre. However, there are organizational patterns within a genre that readers tend to expect. Genre expectations allow readers to feel familiar with the literary work and help them to organize the information presented by the writer. In addition, keeping with genre conventions can establish a writer’s relationship with their readers and a framework for their literature.

Here are some examples of genres in literature and the conventions they represent:

Example 1: Macbeth by William Shakespeare

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow , Creeps in this petty pace from day to day To the last syllable of recorded time, And all our yesterdays have lighted fools The way to dusty death. Out, out , brief candle! Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player That struts and frets his hour upon the stage And then is heard no more: it is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing.

The formal genre of this well-known literary work is Shakespearean drama or play. Macbeth can be sub-categorized as a literary tragedy in that the play features the elements of a classical tragic work. For example, Macbeth’s character aligns with the traits and path of a tragic hero –a protagonist whose tragic flaw brings about his downfall from power to ruin. This tragic arc of the protagonist often results in catharsis (emotional release) and potential empathy among readers and members of the audience .

In addition to featuring classical characteristics and conventions of the tragic genre, Shakespeare’s play also resonates with modern readers and audiences as a tragedy. In this passage, one of Macbeth’s soliloquies , his disillusionment, and suffering is made clear in that, for all his attempts and reprehensible actions at gaining power, his life has come to nothing. Macbeth realizes that death is inevitable, and no amount of power can change that truth. As Macbeth’s character confronts his mortality and the virtual meaninglessness of his life, readers and audiences are called to do the same. Without affirmation or positive resolution , Macbeth’s words are as tragic for readers and audiences as they are for his own character.

Like M a cbeth , Shakespeare’s tragedies are as currently relevant as they were when they were written. The themes of power, ambition, death, love, and fate incorporated in his tragic literary works are universal and timeless. This allows tragedy as a genre to remain relatable to modern and future readers and audiences.

Example 2: The Color Purple by Alice Walker

All my life I had to fight. I had to fight my daddy . I had to fight my brothers. I had to fight my cousins and my uncles. A girl child ain’t safe in a family of men. But I never thought I’d have to fight in my own house. She let out her breath. I loves Harpo, she say. God knows I do. But I’ll kill him dead before I let him beat me.

The formal genre of this literary work is novel. Walker’s novel can be sub-categorized within many fictional genres. This passage represents and validates its sub-classification within the genre of feminist fiction. Sofia’s character, at the outset, is assertive as a black woman who has been systematically marginalized in her community and family, and she expresses her independence from the dominance and control of men. Sofia is a foil character for Celie, the protagonist, who often submits to the power, control, and brutality of her husband. The juxtaposition of these characters indicates the limited options and harsh consequences faced by women with feminist ideals in the novel.

Unfortunately, Sofia’s determination to fight for herself leads her to be beaten close to death and sent to prison when she asserts herself in front of the white mayor’s wife. However, Sofia’s strong feminist traits have a significant impact on the other characters in the novel, and though she is not able to alter the systemic racism and subjugation she faces as a black woman, she does maintain her dignity as a feminist character in the novel.

Example 3: A Word to Husbands by Ogden Nash

To keep your marriage brimming With love in the loving cup, Whenever you’re wrong, admit it; Whenever you’re right, shut up.

The formal genre of this literary work is poetry. Nash’s poem would be sub-categorized within the genre of humor . The poet’s message to what is presumably his fellow husbands is witty, clear, and direct–through the wording and message of the last poetic line may be unexpected for many readers. In addition, the structure of the poem sets up the “punchline” at the end. The piece begins with poetic wording that appears to romanticize love and marriage, which makes the contrasting “base” language of the final line a satisfying surprise and ironic twist for the reader. The poet’s tone is humorous and light-hearted which also appeals to the characteristics and conventions of this genre.

Synonyms of Genre

Genre doesn’t have direct synonyms . A few close meanings are category, class, group, classification, grouping, head, heading, list, set, listing, and categorization. Some other words such as species, variety, family, school, and division also fall in the category of its synonyms.

Post navigation

What is a Genre? Definition, Examples of Genres in Literature

Home » The Writer’s Dictionary » What is a Genre? Definition, Examples of Genres in Literature

Genre definition: Genre is the organization and classification of writing.

What is Genre in Literature?

What does genre mean? Genre is the organization of literature into categories based on the type of writing the piece exemplifies through its content, form, or style.

Example of Literary Genre

The poem “My Papa’s Waltz” by Theodore Roethke fits under the genre of poetry because its written with lines that meter and rhythm and is divided into stanzas.

It does not follow the traditional sentence-paragraph format that is seen in other genres

Types of Literary Genre

There are a few different types of genre in literature. Let’s examine a few of them.

Poetry : Poetry is a major literary genre that can take many forms. Some common characteristics that poetry shares are that it is written in lines that have meter and rhythm. These lines are put together to form stanza in contrast to other writings that utilize sentences that are divided into paragraphs. Poetry often relies heavily on figurative language such as metaphors and similes in order to convey meanings and create images for the reader.

- “Sonnet 18” is a poem by William Shakespeare that falls within this category of literature. It is a structured poem that consists of 14 lines that follow a meter (iambic pentameter) and a rhyme scheme that is consist with Shakespearean Sonnets.

Drama : This literary genre is often also referred to as a play and is performed in front of an audience. Dramas are written through dialogue and include stage directions for the actors to follow.

- The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde would be considered a drama because it is written through dialogue in the form of a script that includes stage directions to aid the actors in the performance of the play.

Prose : Prose is a type of writing that is written through the use of sentences. These sentences are combined to form paragraphs. This type of writing is broad and includes both fiction and non-fiction.

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee is an example of fictional prose. It is written in complete sentences and divided through paragraphs.

Fiction : Fiction is a type of prose that is not real. Authors have the freedom to create a story based on characters or events that are products of their imaginations. While fiction can be based on true events, the stories they tell are imaginative in nature.

Like poetry, this genre also uses figurative language; however, it is more structural in nature and more closely follows grammatical conventions. Fiction often follows Freytag’s plot pyramid that includes an exposition, inciting incident, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution, and dénouement.

- The novel Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut is an example of a fictional story about the main character’s experience with his self-acclaimed ability to time travel.

Nonfiction : Nonfiction is another type of prose that is factual rather than imaginative in nature. Because it is more factual and less imaginative, it may use less figurative language. Nonfiction varies however from piece to piece. It may tell a story through a memoir or it could be strictly factual in nature like a history textbook.

- The memoir Night by Elie Wiesel is a memoir telling the story of Wiesel’s experience as a young Jewish boy during the Holocaust.

The Function of Genre

Genre is important in order to be able to organize writings based on their form, content, and style.

For example, this allows readers to discern whether or not the events being written about in a piece are factual or imaginative. Genre also distinguishes the purpose of the piece and the way in which it is to be delivered. In other words, plays are meant to be performed and speeches are meant to be delivered orally whereas novels and memoirs are meant to be read.

Summary: What Are Literary Genres?

Define genre in literature: Genre is the classification and organization of literary works into the following categories: poetry, drama, prose, fiction, and nonfiction. The works are divided based on their form, content, and style. While there are subcategories to each of these genres, these are the main categories in which literature is divided.

Final Example:

The short story “The Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allan Poe is a fictional short story that is written in prose. It fits under the prose category because it is written using complete sentences that follow conventional grammar rules that are then formed into paragraphs.

The story is also identified as fictional because it is an imagined story that follows the plot structure.

- Campus Library Info.

- ARC Homepage

- Library Resources

- Articles & Databases

- Books & Ebooks

Baker College Research Guides

- Research Guides

- General Education

COM 1010: Composition and Critical Thinking I

- Understanding Genre and Genre Analysis

- The Writing Process

- Essay Organization Help

- Understanding Memoir

- What is a Book Cover (Not an Infographic)?

- Understanding PowerPoint and Presentations

- Understanding Summary

- What is a Response?

- Structuring Sides of a Topic

- Locating Sources

- What is an Annotated Bibliography?

- What is a Peer Review?

- Understanding Images

- What is Literacy?

- What is an Autobiography?

- Shifting Genres

Understanding What is Meant by the Word "Genre"

What do we mean by genre? This means a type of writing, i.e., an essay, a poem, a recipe, an email, a tweet. These are all different types (or categories) of writing, and each one has its own format, type of words, tone, and so on. Analyzing a type of writing (or genre) is considered a genre analysis project. A genre analysis grants students the means to think critically about how a particular form of communication functions as well as a means to evaluate it.

Every genre (type of writing/writing style) has a set of conventions that allow that particular genre to be unique. These conventions include the following components:

- Tone: tone of voice, i.e. serious, humorous, scholarly, informal.

- Diction : word usage - formal or informal, i.e. “disoriented” (formal) versus “spaced out” (informal or colloquial).

- Content : what is being discussed/demonstrated in the piece? What information is included or needs to be included?

- Style / Format (the way it looks): long or short sentences? Bulleted list? Paragraphs? Short-hand? Abbreviations? Does punctuation and grammar matter? How detailed do you need to be? Single-spaced or double-spaced? Can pictures / should pictures be included? How long does it need to be / should be? What kind of organizational requirements are there?

- Expected Medium of Genre : where does the genre appear? Where is it created? i.e. can be it be online (digital) or does it need to be in print (computer paper, magazine, etc)? Where does this genre occur? i.e. flyers (mostly) occur in the hallways of our school, and letters of recommendation (mostly) occur in professors’ offices.

- Genre creates an expectation in the minds of its audience and may fail or succeed depending on if that expectation is met or not.

- Many genres have built-in audiences and corresponding publications that support them, such as magazines and websites.

- The goal of the piece that is written, i.e. a newspaper entry is meant to inform and/or persuade, and a movie script is meant to entertain.

- Basically, each genre has a specific task or a specific goal that it is created to attain.

- Understanding Genre

- Understanding the Rhetorical Situation

To understand genre, one has to first understand the rhetorical situation of the communication.

Below are some additional resources to assist you in this process:

- Reading and Writing for College

Genre Analysis

Genre analysis: A tool used to create genre awareness and understand the conventions of new writing situations and contexts. This a llows you to make effective communication choices and approach your audience and rhetorical situation appropriately

Basically, when we say "genre analysis," that is a fancy way of saying that we are going to look at similar pieces of communication - for example a handful of business memos - and determine the following:

- Tone: What was the overall tone of voice in the samples of that genre (piece of writing)?

- Diction : What was the overall type of writing in the three samples of that genre (piece of writing)? Formal or informal?

- Content : What types(s) of information is shared in those pieces of writing?

- Style / Format (the way it looks): Do the pieces of communication contain long or short sentences? Bulleted list? Paragraphs? Abbreviations? Does punctuation and grammar matter? How detailed do you need to be in that type of writing style? Single-spaced or double-spaced? Are pictures included? If so, why? How long does it need to be / should be? What kind of organizational requirements are there?

- Expected Medium of Genre : Where did the pieces appear? Were they online? Where? Were they in a printed, physical context? If so, what?

- Audience: What audience is this piece of writing trying to reach?

- Purpose : What is the goal of the piece of writing? What is its purpose? Example: the goal of the piece that is written, i.e. a newspaper entry is meant to inform and/or persuade, and a movie script is meant to entertain.

In other words, we are analyzing the genre to determine what are some commonalities of that piece of communication.

For additional help, see the following resource for Questions to Ask When Completing a Genre Analysis .

- << Previous: The Writing Process

- Next: Essay Organization Help >>

- Last Updated: Feb 23, 2024 2:08 PM

- URL: https://guides.baker.edu/com1010

- Search this Guide Search

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write Within a Genre

I. What is a Genre?

A genre is a category of literature identified by form, content, and style. Genres allow literary critics and students to classify compositions within the larger canon of literature. Genre (pronounced ˈzhän-rə) is derived from the French phrase genre meaning “kind” or “type.”

II. Types and Examples of Genres

Literature could be divided into countless genres and subgenres, but there are three main genres which preside over most subgenres. Here are the main genres in literature:

As poetry has evolved, it has taken on numerous forms, but in general poetry is the genre of literature which has some form of meter or rhyme with focus based on syllable counts, musicality, and division of lines (lineation). Unlike prose which runs from one end of the page to the other, poetry is typically written in lines and blocks of lines known as stanzas .

Here is an excerpt from Maya Angelou’s “Still I Rise”:

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom?

‘Cause I walk like I’ve got oil wells

Pumping in my living room.

Just like moons and like suns,

With the certainty of tides,

Just like hopes springing high,

Still I’ll rise.

Prose encompasses any literary text which is not arranged in a poetic form. Put simply, prose is whatever is not poetry. Prose includes novels, short stories, journals, letters, fiction and nonfiction, among others. This article is an example of prose.

Drama is a text which has been written with the intention of being performed for an audience. Dramas range from plays to improvisations on stage. Popular dramas include Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet , Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun , and Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire.

III. The Importance of Using Genres

Genres give writers a specific type of literature to work within. They allow writers to specialize in one genre or to dabble in others. Students in creative writing may focus in a variety of genres from poetry to prose to nonfiction to playwriting. Genres allow us to classify literature, to deem what is appropriate for a certain type of literature, and to judge the merit of literature based on its genre. In general, genre is a classifying tool which allows us to compare and contrast works within the same genre and to study how works broaden or challenge certain genre-based constraints. New genres like media (writing for television, film, websites, radios, billboards, etc.) and the graphic novel (comic books) are expanding what we consider literature today.

IV. Genres in Literature

The three main genres in literature are prose, poetry, and drama, but there are many more subgenres, or genres within genres. Here are a few examples of other genres in literature:

Maus: A Survivor’s Tale by Art Spiegelman

Maus is an example of a literary genre called the graphic novel, sometimes better known as the comic book. In Maus , Spiegelman tells the story of the Holocaust using animal characters .

Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson

THE FIRST TEN LIES THEY TELL YOU IN HIGH SCHOOL 1. We are here to help you. 2. You will have time to get to your class before the bell rings. 3. The dress code will be enforced. 4. No smoking is allowed on school grounds. 5. Our football team will win the championship this year. 6. We expect more of you here. 7. Guidance counselors are always available to listen. 8. Your schedule was created with you in mind. 9. Your locker combination is private. 10.These will be the years you look back on fondly. TEN MORE LIES THEY TELL YOU IN HIGH SCHOOL 1. You will use algebra in your adult lives. 2.Driving to school is a privilege that can be taken away. 3. Students must stay on campus during lunch. 4. The new text books will arrive any day now. 5. Colleges care more about you than your SAT scores. 6. We are enforcing the dress code. 7. We will figure out how to turn off the heat soon. 8. Our bus drivers are highly trained professionals. 9. There is nothing wrong with summer school. 10. We want to hear what you have to say.

Speak is an example of young adult fiction, another subgenre of prose. YA fiction appeals to young adults from the ages of twelve to eighteen with coming-of-age stories about various subjects from high school struggles to family conflict to relationships.

There are numerous genres in literature, including poetry and prose, fiction and nonfiction, short stories and novels, dramas, fables , fairytales, legends , biographies, and reference books. The list goes on with countless genres and subgenres categorizing literature in numerous ways based on numerous characteristics and styles of writing.

V. Genres in Pop Culture

Genres are not limited to literature. There are genres of movies, television shows, and songs as well. Here are a few examples of genres in pop culture.

![meaning of genre essay The Notebook Movie Trailer [HD]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/FC6biTjEyZw/0.jpg)

Nicholas Sparks’ The Notebook is considered by many to be the quintessential example of the romance genre in both fiction books and movies. Other movie genres include drama, comedy, romantic comedy, sci-fi, animated, and fantasy.

The are a lot of musical genres. The following are some of the most popular genres:

- Hip hop music

- Classical period

- Country music

- Classical music

- Popular music

- Rhythm and blues

- Heavy metal

- Electronic dance music

- Alternative rock

- Instrumental

VI. Related Terms: Style vs. Genre

Often, an aspect of what allows us to define a genre is the specific style of the writing. The mystery genre purposely uses suspense and withholding certain information from the reader. Different subgenres of poetry are written in different styles: haikus tend to be peaceful or playful, sonnets are often romantic, and free verse is free to hop styles with or without rhyme, with or without line breaks. The difference between style and genre is that genre is an overarching type of literature, whereas style can be considered an aspect of a genre or even of a specific writer’s voice. Here is an example of style versus genre:

We have no idea what’s going on! Who knows? Who could possibly know? Who murdered Mr. Brown?! Everyone is panicking! No one knows what to do! This is insane!

The style of this writing is choppy, overly dramatic, and panicked.

This story investigates the murder of Mr. Brown, who was found dead in the library.

The genre, on the other hand, is the murder mystery.

VII. In Closing

Genres allow us to divide various types of literature, music, movies, and other art forms into classifiable groups. Beyond the classical genres of prose, poetry, and drama in literature, there are numerous subgenres ranging from fantasy to nonfiction.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Literary Devices

Literary devices, terms, and elements, definition of genre.

A genre is any stylistic category in literature that follows specific conventions. Examples of genre in literature include historical fiction, satire , zombie romantic comedies (zom-rom-com), and so on. Many stories fit into more than one genre. The conventions that works follow to be a part of a certain genre change over time, and many genres appear and disappear throughout the ages.

The word genre comes from French, in which it means “kind” or “sort.” Originally, the word came from the Greek word γένος ( génos ) in which it has the same meaning. The Ancient Greeks created the definition of genre in order to classify their literature into the three categories of prose , poetry, and performance. From this early classification, more genres arose, such as the split between comedy and tragedy .

Types of Genre

There is wide proliferation of genre examples in the field of literature. Genre can be split by tone, content, length of novel, and literary technique. Note that genre is not defined by age (children’s literature, young adult, etc), nor by format (graphic novel, picture book, novel). Here is a short and non-exhaustive list of different genre examples in literature:

Common Examples of Genre

Genre is a term used in many different forms of entertainment, including movies, music, and television. Here is a list of different genres in film with examples of each genre:

- Romantic comedy : Love, Actually; When Harry Met Sally; Pretty Woman

- Musical : West Side Story; Hello, Dolly!; Fiddler on the Roof

- Crime : The Godfather; Goodfellas; Pulp Fiction

- Horror : Scream; I Know What You Did Last Summer; Saw

- War : Saving Private Ryan; Platoon; Schindler’s List

- Western : The Great Train Robbery; True Grit; The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

- Documentary : An Inconvenient Truth; The Cove; Super Size Me

Significance of Genre in Literature

Genre conventions began to be defined in Ancient Greece to classify the theme of each work of literature. Greek playwrights agreed that some speech patterns were more suited to tragedy, while others were better for comedies, and indeed the themes of plays were divided by genre as well. In fact, genre was so important in Ancient Greek drama that actors were allowed only to perform only in one genre. Comedic actors did not perform in tragedies, and tragic actors did not perform in comedies.

Since the time of Ancient Greece the variety of genre examples has widened considerably, so that no list could be all-encompassing. There are many subcategories of each drama as well. For example, in the genre of science fiction we could find stories classified as apocalyptic ( War of the Worlds ), space opera ( Star Wars ), future noir ( Blade Runner ) and techno-thriller ( The Hunt for Red October ), to name just a few. Every work of literature can fit into a genre, and more than one genre can often be applied to a work. Genre shapes the reader’s expectations for that work, while authors also usually try to play with and push against the conventions in new ways.

Examples of Genre in Literature

PRINCE: A glooming peace this morning with it brings; The sun, for sorrow, will not show his head: Go hence, to have more talk of these sad things: Some shall be pardon’d, and some punished: For never was a story of more woe Than this of Juliet and her Romeo.

( Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare)

William Shakespeare’s plays are split into three genres: comedy, tragedy, and history. Each type of play had its own conventions. In Shakespeare’s tragedies, such as Romeo and Juliet , always end with the death of one or more characters. Comedies, on the other hand, end with one or more marriages. There was also frequent cross-dressing in Shakespearean comedies for humorous purposes, which was not a part of his tragedies. There are also more examples of foolish characters in Shakespeare’s comedies, whereas in his tragedies and histories this stereotypical character was not as prevalent.

At that time Macondo was a village of twenty adobe houses, built on the bank of a river of clear water that ran along a bed of polished stones, which were white and enormous, like prehistoric eggs. The world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point.

( One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez)

Gabriel García Márquez’s novel One Hundred Years of Solitude is an example of the genre of magical realism. This is a genre that was created in the mid-20th century in Latin America, and involves supernatural events and characters. García Márquez sets up the expectations of this example of genre by showing that the fictive world in which the action takes place is different from the normal world, and has magical elements to it. The above paragraph shows that the village of Macondo is prelapsarian (e.g., before “Original Sin”) and thus there is a supernatural quality to the setting .

Now we walk along the same street, in red pairs, and no man shouts obscenities at us, speaks to us, touches us. No one whistles. There is more than one kind of freedom, said Aunt Lydia. Freedom to and freedom from. In the days of anarchy, it was freedom to. Now you are being given freedom from. Don’t underrate it.

( The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood)

Margaret Atwood’s novel The Handmaid’s Tale is an example of narrative that can be described with more than one genre. It can be called a dystopian thriller, feminist science fiction, or post-apocalyptic. There are obvious indications that things are quite different in this world than in the modern United States, as the social norms have changed. However, there is a chilling dystopian aspect to it, as the character of Aunt Lydia notes that women now are free from men (yet they are enslaved in other ways).

As someone who had spent his life exploring the hidden interconnectivity of disparate emblems and ideologies, Langdon viewed the world as a web of profoundly intertwined histories and events. The connections may be invisible, he often preached to his symbology classes at Harvard, but they are always there, buried just beneath the surface.

( The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown)

Dan Brown’s popular novel The Da Vinci Code includes some aspects of mystery and thriller. The protagonist of the novel, Robert Langdon, is supposed to be a “symbologist” at Harvard University, and uses the study of ancient symbols, especially in religion, to solve a modern-day mystery. Many thrillers, such as The Da Vinci Code , put an emphasis on plot over character development and using twists in the narrative to keep the readers excited.

“But this is touching, Severus,” said Dumbledore seriously. “Have you grown to care for the boy, after all?” “For him?” shouted Snape. “Expecto Patronum!” From the tip of his wand burst the silver doe: She landed on the office floor, bounded once across the office, and soared out of the window.

( Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by J.K. Rowling)

J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series is an example of the fantasy genre. It is categorized as young adult fiction, but again, this is not the genre of the novel. Indeed, while it is suggested as a good series for young adults and children, people of all ages enjoy these novels. The fantasy genre is represented by many different aspects of the series. In the above excerpt we can see fantastical and magical elements such as the use of spells and wands. J.K. Rowling also uses other conventions of the fantasy genre, such as the fight between good and evil, epic quests, and an alternate world in which different rules are possible.

Test Your Knowledge of Genre

1. Which of the following statements is the best genre definition? A. A category of literature that follows certain conventions. B. A way of classifying the appropriate age range of a work of literature. C. A system of differentiating literature from film and music.

2. Which of the following labels is an example of genre in literature? A. Young adult novel B. Graphic novel C. True crime thriller

3. Which of the following events usually concludes a Shakespearean comedy? A. One or more deaths B. One or more weddings C. A humorous epilogue

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

What are Genres?

Key Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Describe the concept of genre.

- Recognize differences across genres.

- Understand the concept of corollary genres.

- Identify and differentiate between writing genres and their particular conventions.

Introduction to Genres

Welcome to the genre chapter! At this point you might be asking yourself, “What exactly is a genre?” Or you might be thinking, “I have an idea of what genre means, but I’m not sure what genres do and why that’s important to writing.” Well, regardless of how confident you feel or don’t feel about your knowledge of genre, you’re probably more familiar with genre than you might think.

First off, a genre is a way to classify media, texts, documents, films, and many other written or artistic forms of expression. Think about a movie that you really enjoy watching and why. Is it because of the plot or story? The characters? The organization, structure, or dynamic visual effects? Is it because you can relate to it fairly easily? Or because it brings you comfort or feelings of nostalgia? There are numerous reasons why we might enjoy a certain type of movie, and many of us develop a predilection for films that share similar characteristics. In other words, we tend to prefer certain genres of movies. As Aristotle would proclaim, we humans are creatures of classification: Genres help us organize, enjoy, and compose texts or other forms of media more effectively and efficiently.

Now, think back to that movie you really enjoy watching. What classification, or genre, would you assign it to? Rom-com, horror, action? None of the above? Let’s say you chose 50 First Dates as your movie you enjoy watching. What would we classify this movie as? Probably a rom-com right? Why, though? What makes it rom-com? For one, there’s a romantic plot about love. The writers of the rom-com also sprinkled in some humor and a few barriers the lovers have to overcome before they can actually win each others’ affections. There are also the romance elements: wooing, tokens of appreciation, playing hard to get, exchanging saliva, and more. We can see here that certain movies have certain characteristics or traits that earn them a specific classification.

What happens, though, when we come across a genre that doesn’t quite fit the bill? How do we feel when the genre excludes or bends standard expectations or characteristics? Are we disappointed, upset, or intrigued? Why? Well, audiences have certain expectations for particular genres. When these expectations are not met, the audience reacts to or reads a text differently, which impacts the success of the work either positively or negatively. Thus genre classifications require conventions or defining characteristics that meet and/ or surpass an audience’s standard expectations. By understanding these conventions in terms of audience and other aspects of the rhetorical situation, we can more easily navigate, analyze, and use genres, especially when we want to use them to compose our own work.

A genre is a particular kind of text created for a particular audience and purpose, often with certain identifying features. However, genres are more than categories. According to the Writing Commons, “Genres reflect shared textual expectations between readers and writers. Genre reflects the histories, activities, and values of communities of practitioners” (“Genre and Medium”). As we see through these movie examples above, genres can reflect community values as much as they create and sustain communities. Genres “provide a roadmap to rhetors for how to engage with community members in socially acceptable ways” (“Genre and Medium”).

Genres of writing include, for example, a research article; a short story; a movie review; an email; a business report; a press release; and a diary entry. You’ll be asked to produce writing in different genres for different purposes (public, academic, and professional) throughout your writing career. Rather than try to predict which genres you’ll encounter, this chapter will provide you with tools to identify the key features and characteristics of writing genres. After reading through this chapter and completing the activities, you will be able to recognize different writing genres, understand the concept of corollary genres, and determine the expectations for writing genres you’ll encounter in your life.

Reading and Writing in College Copyright © 2021 by Jackie Hoermann-Elliott and TWU FYC Team is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Module 3: Critical Reading

What is genre, learning objectives.

Differentiate between the goals and purposes of various genres of texts

Like movies and books, music is often grouped by genre. How many musical genres can you name?

One important way to empower yourself as a reader (and also a writer) is to learn how to understand genres . The word “genre” (pronounced “john-ruh” with a soft j, like “zhaan-ruh”) comes from the French and roughly means type, kind, category, or class (in keeping with the fact that it’s related to the Latin word genus , which you might recognize from biology). You’re probably already familiar with the term in connection with movies, which are grouped into various genres: horror, Western, drama, romantic comedy, documentary, and so on. Music, as well, has genres: you’ve probably heard of hip-hop, jazz, pop, rap, and rock… but how about glitch hop, vaporwave, lowercase, or pirate metal? Genres can be quite broad, like popular music or instrumental music, or very specific, like soukous or vegan straight edge.

Have you ever watched a movie where you have no idea what the genre is? It can be pretty disconcerting. You don’t know whether you should get ready to laugh, cry, or scream. Similarly, when you go to read something, it can be helpful to know something about the genre in advance. Your approach will change depending on whether you’re reading a research paper, a blog post, a novel, or a grocery list. Each of the four types of writing just named represents a genre (type, category). You can probably think of many more, from biographies to self-help books to cookbooks. (This brings up an important point: “Genre” can refer to the overall form of a text, such as a novel or a textbook, or it can refer to a specific subcategory of that form, such as a mystery novel or a math textbook. Here, we’re more concerned with the first of these, genre-as-form.)

Genres help us communicate better both as readers and as writers. As a reader, you can understand text more easily by developing genre awareness . For example, when you pick up a biography, you know it’s going to tell the life story of a real person, so you approach it with a different set of expectations than you would a novel, which tells a fictional story. If you mistook a biography for a novel, you’d fundamentally misconstrue what you were reading. On the writer’s end, genre awareness helps to plan, organize, and craft the text better, because each genre embodies a set of rules and guidelines for fulfilling a specific purpose and meeting readers’ expectations.

Not incidentally, that’s also your best working definition as we move forward: A genre represents a pattern or set of rules that a given text follows in order to communicate its message effectively to its intended audience . When you read any written text, the aspects of rhetoric that you may have learned about in previous composition classes—purpose, audience, context, and so on—lead you to approach the reading with a certain set of expectations. The concept of genre encompasses these things and provides the added benefit of a pattern or “recipe” for you to follow.

The first step to enjoying this benefit is simply to become more genre-aware. Learn to recognize that virtually everything you read follows the rules of a certain genre. Use this recognition to approach and attack your reading more enjoyably and intelligently.

The Goals and Purposes of Different Academic Genres

The key to understanding a genre is first to understand its purpose. Each genre sets out to accomplish something specific. For example, as mentioned above, the purpose of any biography is to tell someone’s life story. You have to understand this at the outset to understand what you’re reading.

You’ll improve your success as a college student if you understand the goals and purposes of the genres that you’re most likely to encounter in the college setting. These include textbooks, scholarly articles, reference works, journalism, and works of literature. Each of these displays typical features that are related to its primary purpose.

A Note about Academic Genres

When thinking about genres, remember two things about the reading and writing that you’ll do in this class, and also in the entirety of your college career.

First, academic writing forms of its own subset of genres. In a composition class, you may read texts belonging to any or all of the genres you’ve been learning about here. You may also write texts in a variety of genres, including genres that have been developed mainly for classroom learning purposes, such as the five-paragraph essay, the informative research paper, and the persuasive research paper. As you learned in the first section of this module, there’s also an entire world of professional academic/scholarly writing. Student academic writing and professional scholarly writing both follow their own sets of genre recipes for producing writing with specific characteristics to fulfill specific purposes within the educational context.

Second, academic writing is not intrinsically more intelligent, more important, or otherwise “better” than other types of writing. Rather, it’s just one subset of genres among many. It’s a collection of genres that are useful within their intended contexts, for their given purposes. And as with any genre, to be successful in academic ones, it’s simply the case that you need to become familiar with their rules and patterns (such as the use of an academic citation format — MLA, APA, Chicago style, or another — when writing a research paper or scholarly article).

- Video: Understanding genre awareness. Provided by : CAES HKU. Located at : https://youtu.be/Daut5e0kWBo . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Image: Textbooks. Authored by : Logan Ingalls. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/cStoi . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Enyclopedia Britannica International Chinese Edition. Authored by : Hawyih. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Enyclopedia_Britannica_International_Chinese_Edition.jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Polish sci-fi and fantasy books. Authored by : Piotrus. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Polish_sci_fi_fantasy_books.JPG . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cairo newsstand. Authored by : flyvancity. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2010_newsstand_Cairo_4508283265.jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- More and More Genres. Authored by : lukatoyboy. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/4ACv8C . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- What is Genre?. Authored by : Matt Cardin. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- University Writing Center

- The Writing Mine

How To: Genre Analysis

Although most of us think of music styles when we hear the word “genre,” the word simply means category of items that share the same characteristics, usually in the arts. In this context, however, we are talking about types of texts. Texts can be written, visual, or oral.

For instance, a written genre would be blogs, such as this one, books, or news articles. A visual genre would be cartoons, videos, or posters. An oral genre would be podcasts, speeches, or songs. Each of these genres communicates differently because each genre has different rules.

A genre analysis is an essay where you dissect texts to understand how they are working to communicate their message. This will help you understand that each genre has different requirements and limitations that we, as writers, must be aware of when using that genre to communicate.

Sections of a genre analysis

Like all other essays, a genre analysis has an introduction, body, and conclusion.

In your introduction, you introduce the topic and the texts you’ll be analyzing.

In your body, you do your analysis. This should be your longest section.

In your conclusion, you do a short summary of everything you talked about and include any closing thoughts, such as whether you think the text accomplished its purpose and why.

Content

All professors ask for different things, so make sure to look at their instructions. These are some areas that will help you analyze your text and that you might want to touch base on in your essay (most professors ask for them):

1. Purpose of the text

What did the creator of the text want to achieve with it? Why was the text created? Did something prompt the creator to make the text?

Sometimes, the texts themselves answer these questions. Other times, we get that through clues like the language they use, the platforms the creator chose to spread their text, and so on. Make sure to include in your essay what features of the text led you to your answer.

If we take this blog post as an example, we can say that its purpose is to inform students like you about what a genre analysis is and the content it requires. You probably figured this out through the language I’m using and the information I’m choosing to include.

2. Intended audience

Who is the creator of the text trying to reach? How did you figure that out?

The audience can be as specific as a small group of people interested in a very niche topic or as broad as people curious about a common topic.

With this blog, for example, I’m trying to reach students, particularly UTEP students who have this assignment and are trying to understand it. My causal and informative tone, as well as the fact that the blog is posted on UTEP’s Writing Center blog, probably gave this away.

3. Structure

How is the text organized? How does that help the creator achieve the text’s purpose?

You need to know the information at the top of this blog post to understand what comes after, so this blog post is organized in order of complexity.

4. Genre conventions

Is the text following the usual characteristics of the genre? How is this helping or impeding the text to achieve its purpose?

Like most blogs, this one is using simple language, short paragraphs, and illustrations. My use of all these elements is helping me be clear and specific so you can understand your assignment.

5. Connection

Do the ideas in the text come from somewhere else? Can the reader or consumer interact with the text? Is the text inviting that interaction?

Most of the time, when the ideas come from another source, the text will make that clear by mentioning the text. In terms of interaction possible with the text, think about if it would be easy for you to say something back to the text.

For instance, if you wanted to ask a question about this blog post, you could type it in our comment section. I might not explicitly say that many ideas in this blog come from the guidelines your professor gives you for this assignment, but you probably gathered that because I mention that these areas are things most professors are looking for.

Hopefully, this information helps you tackle your assignment with a clearer idea of what your professor is looking for. Make sure to address any other areas the professor is asking you to.

If you still have questions or want to make sure you are on the right path, come visit us at the University Writing Center.

Connect With Us

The University of Texas at El Paso University Writing Center Library 227 500 W University El Paso, Texas 79902

E: [email protected] P: (915) 747-5112

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Genre Analysis & Reverse Outlining

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This vidcast explains two tools that writers can use as they revise their documents: genre analysis and reverse outlining. Genre analysis involves looking at model texts to gain an understanding of how a particular document might be composed. Reverse outlining helps writers look at their organization throughout a document by looking at what sections are doing as well as what they are saying. Several handouts provide additional explanation of both topics and explain how to create a database of sentence templates to do particular kinds of rhetorical work.

Note: Closed-captioning and a full transcript are available for this vidcast.

Genre Analysis (PDF)

Genre analysis is a way of examining a type or style of writing in order to better understand the conventions, expectations, purpose, and target audience for that genre. This handout briefly outlines some steps for two approaches to genre analysis: (1) the global vs. local approach, which analyzes what a style of writing is doing on a large and small scale, and (2) the reverse outlining approach, which analyzes what a style of writing is both saying and doing at the paragraph level in relation to an overarching purpose.

Questions for Genre Analysis (PDF)

This handout contains questions that are intended to help guide writers working with model texts. It is recommended for use in conjunction with the Genre Analysis (PDF) linked in the preceeding section. The questions range from global rhetorical concerns to sentence structure and voice.

Organization & the CARS Model

This resource provides strategies for revising introductions. The CARS Model ensures that writers adequately put their research into a wider context, address what's missing in the surrounding scholarship in relation to the topic at hand, and explain how their writing seeks to address those gaps.

Reverse Outlining

Reverse outlining is a strategy that helps writers distill main ideas into short, clear statements.This tool is especially helpful for refocusing an argument and the overall organization of a text. This resource explains the steps for creating a reverse outline so that writers are empowered to revise their own work.

Creating a Database of Templates (PDF)

Scholarly writing features many sentences that follow a particular form, pattern, or template, such as when it indicates a gap in research or makes a counter-claim. This handout outlines how one can learn to write within a discipline by creating a database of template-sentences in their field.

Florida State University

FSU | Writing Resources

Writing Resources

The English Department

- College Composition

Genre Knowledge: Linking Movies and Music to Genres of Writing

- Genre Scavenger Hunt

Genre and Rhetorical Situation: Choosing an appropriate Genre

- Genre and Reflection Exercise: Using Reflection to Understand Genre

Comparing Digital Genres: Facebook, Twitter, and Text Messaging

Purpose of Exercise: This exercise helps students understand that writers use genre to reach a variety of different audiences (themselves, friends, peers, instructors, employers, parents, and more) with lots of different expectations. To reach an audience effectively, writers need to be flexible -- they need to be able to analyze and make decisions about how to approach any writing situation. Developing genre knowledge prepares students to assess the writing situations they’ll encounter in college and beyond.

Description: Students work in small groups to identify conventions of various movie genres and discuss audience expectations. Each group presents the conventions of their genre to the class, and class discussion allows for identification of similarities/differences/connections between genres. The discussion shifts to genres of music, where conventions are identified but also the “blurriness” of genres is discussed. All this discussion about the familiar – movies and music – gets students to identify what a genre is, how we might define it or at least qualify it, and finally what an audience expects from a particular genre. Students have some confidence about the concept of genre for the next step, the discussion of the less familiar writing genres. In groups, students identify conventions of various genres of writing – the academic essay, a text message, a newsletter, a poster, a web site, a lab report, an obituary, a magazine article – and report back. The class then discusses what these genres include, how they might be defined, and what audiences expect from each genre.

Suggested Time: 30-50 for exercise; plus 20 minutes suggested for journal writing which can be assigned in–class or as homework

Procedure: Divide students into small groups. Assign each group a movie genre (horror, romantic comedy, drama, action, thriller, comedy, documentary, or other). Have students answer the following questions:

- Genre: What are the conventions of your group’s movie genre?

- Audience: Who goes to/rents/watches this type of movie?

- Audience Expectation: What does an audience expect to experience/feel/learn/see from this genre?

- Evidence: Provide 3 examples of movies that fit this type and explain why they fit.

Move to class discussion – ask each group to present their genre while you note their points on the board; once all groups are done, engage in class discussion to add more conventions or expectations, draw connections between genres, and allow students to come up with genres and conventions you did not originally assign.