Engaging Gifted Students in Solving Real Problems Creatively: Implementing the Real Engagement in Active Problem-Solving (REAPS) Teaching/Learning Model in Australasian and Pacific Rim Contexts

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 09 January 2021

- Cite this reference work entry

- C. June Maker 2 &

- Myra Wearne 3

Part of the book series: Springer International Handbooks of Education ((SIHE))

2107 Accesses

We believe that engaging students in solving problems they perceive as real and relevant in their lives, combined with differentiation, is an effective way to nurture giftedness and talent in all domains while also discovering hidden talents and providing a setting for developing all students’ strengths, interests, and passions. In this chapter, we describe a teaching model made up of three other evidence-based teaching models with a common goal of enhancing students’ ability to think creatively, critically, and collaboratively while learning essential content-related ideas and skills. We demonstrate the model’s comprehensiveness as a way to: differentiate the curriculum for all levels of learners and children with varied types of abilities, inclusive of gifted students; outline the guiding paradigms of thinking that led to its creation; give an overview of the evidence-based models that form the framework and methods of teaching that make up Real Engagement in Active Problem-Solving (REAPS); describe ways it has been implemented in Australasian and Pacific Rim contexts; provide examples from classrooms in Korea, Australia, China, and New Zealand; introduce a long-term, whole-school collaboration to improve the model and test its effectiveness; and summarise results of research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Alfaiz, F. S. (2019). The association between the fidelity of implementation of the Real Engagement in Active Problem Solving (REAPS) model and student gains in creative problem solving in science (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ.

Google Scholar

Alfaiz, F. S., Pease, R., Maker, C. J., & Zimmerman, R. (2017). Culturally responsive assessment of physical science skills and abilities: Development, field testing, and implementation. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Alfaiz, F. S., Pease, R., & Maker, C, J. (2019). Culturally responsive assessments of physical science skills and abilities: Development, field testing, and implementation. Manuscript submitted to the Journal of Advancee Academics. Department of Disability and Psychoeducational Studies, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA.

Alhusaini, A. A. (2016). The effects of duration of exposure to the REAPS model in developing students’ general creativity and creative problem solving in science (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ.

Alhusaini A. A., Maker, C. J., & Alamiri, F. Y. (2015). Adapting the REAPS model to develop students’ creativity in Saudi Arabia: An exploratory study . Unpublished manuscript, Jeddah University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Azano, A., Missett, T. C., Callahan, C. M., Oh, S., Brunner, M., Foster, L. H., & Moon, T. R. (2011). Exploring the relationship between fidelity of implementation and academic achievement in a third-grade gifted curriculum a mixed-methods study. Journal of Advanced Academics, 22 (5), 693–719. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X11424878

Beckett, G. H., Hemmings, H., Maltbie, C., Wright, K., Sherman, M., & Sersion, B. (2016). Urban high school student engagement through CincySTEM iTest projects. Journal of Science Education Technology, 25 , 995–1007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-016-9640-6

Article Google Scholar

Bransford, J., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school (Expanded ed.). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Chi, M. T. H., Feltovich, P., & Glaser, R. (1981). Categorization and representation of physics problems by experts and novices. Cognitive Sciences, 5 (2), 121–152. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog0502_2

Dai, D. Y., & Chen, F. (2013). Three paradigms of gifted education: In search of conceptual clarity in research and practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 57 (3), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986213490020

Delisle, J. R. (2012). Reaching those we teach: The five Cs of student engagement. Gifted Child Today, 35 (1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1076217511427513

Fredricks, J. A., Alfeld, C., & Eccles, J. (2010). Developing and fostering passion in academic and nonacademic domains. Gifted Child Quarterly, 54 (1), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986209352683

Gallagher, S. A. (1997). Problem-based learning: Where did it come from, what does it do, and where is it going? Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 20 (4), 332–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235329702000402

Gallagher, S. A. (2015). The role of problem based learning in developing creative expertise. Asia Pacific Education Review, 16 , 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-015-9367-8

Gallagher, S. A., & Gallagher, J. J. (2013). Using problem-based learning to explore unseen academic potential. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 7 (1), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1322

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gomez-Arizaga, M. P., Bahar, A. K., Maker, C. J., Zimmerman, R. H., & Pease, R. (2016). How does science learning occur in the classroom? Students’ perceptions of science instruction during implementation of the REAPS model. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science, and Technology Education, 12 (3), 431–455. Retrieved from https://www.ejmste.com/download/how-does-science-learning-occur-in-the-classroom-students-perceptions-of-science-instruction-during-4499.pdf

Jang, H., Kim, E., & Reeve, J. (2016). Why students become more engaged or disengaged during the semester: A self-determination theory dual-process model. Learning and Instruction, 43 , 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.002

Jo, S., & Ku, J. (2011). Problem based learning using real-time data in science education for the gifted. Gifted Education International, 27 (3), 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142941102700304

Lee, J.-S. (2014). The relationship between student engagement and academic performance: Is it a myth or reality? The Journal of Educational Research, 107 (3), 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2013.807491

Little, C. A. (2012). Curriculum as motivation for gifted students. Psychology in the Schools, 49 (7), 695–705. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21621

Maker, C. J. (2005). The DISCOVER project: Improving assessment and curriculum for diverse gifted learners (Senior scholars series monograph). Storrs, CT: National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented.

Maker, C. J. (2016). Recognizing and developing spiritual abilities through real-life problem solving. Gifted Education International, 32 (3), 271–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261429415602574

Maker, C. J., & Anuruthwong, U. (2003). The miracle of learning . Featured Speech presented at the World Conference on the Gifted and Talented, Adelaide, Australia.

Maker, C. J., Jo, S.-M., Alfaiz, F. S., & Alhusaini, A. A. (2017). The Test of Creative Problem Solving in Science: Construct and concurrent validity . Manuscript submitted to Creativity Research Journal. Department of Disability and Psychoeducational Studies, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA.

Maker, C. J., & Pease, R. (2017). What do effective teachers do when implementing the REAPS model to differentiate instruction in a general education classroom? Manuscript in preparation. Department of Disability and Psychoeducational Studies, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA.

Maker, C. J., & Schiever, S. W. (2005). Teaching/learning models in education of the gifted (3rd ed.). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Maker, C. J., & Schiever, S. W. (2010). Curriculum development and teaching strategies for gifted learners (3rd ed.). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Maker, C. J., Wu, I.-C., & Pease, R. (2017). The relationship between teachers’ fidelity of implementation of the Real Engagement in Active Problem Solving (REAPS) model and student gains in creative mathematical problem solving . Manuscript in preparation. Department of Disability and Psychoeducational Studies, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA

Maker, C. J., & Zimmerman, R. (2008). Problem solving in a complex world: Integrating DISCOVER, TASC and PBL in a teacher education project. Gifted Education International, 24 (2–3), 160–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142940802400305

Maker, C. J., Zimmerman, R., Alhusaini, A., & Pease, R. (2015a). Real Engagement in Active Problem Solving (REAPS): An evidence-based model that meets content, process, product, and learning environment principles recommended for gifted students. APEX: The New Zealand Journal of Gifted Education, 19 (1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.21307/apex-2015-006

Maker, C. J., Zimmerman, R., Gomez-Arizaga, M., Pease, R., & Burke, E. (2015b). Developing real-life problem solving: Integrating the DISCOVER problem matrix, problem based learning, and thinking actively in a social context. In H. Vidergor & R. Harris (Eds.), Applied practiced for educators of gifted and able learners . Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Martin, T. G., Martin, A. J., & Evans, P. (2017). Student engagement in the Caribbean region: Exploring its role in the motivation and achievement of Jamaican middle school students. School Psychology International, 38 (2), 184–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034316683765

New South Wales Department of Education. (2017). National disability data collection. Retrieved from https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/disability-learning-and-support/personalised-support-for-learning/national-disability-data-collection

New South Wales Education Standards Authority. (2012a). Differentiated programming. Retrieved from https://syllabus.nesa.nsw.edu.au/support-materials/differentiated-programming/

New South Wales Education Standards Authority. (2012b). Teacher accreditation teacher practice. Retrieved from http://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/portal/nesa/teacher-accreditation/proficient-teacher/evidence

New Zealand Ministry of Education. (2017). The Māori education strategy: Ka Hikitia – Accelerating 2013–2017. Retrieved from https://www.education.govt.nz/ministry-of-education/overall-strategies-and-policies/the-maori-education-strategy-ka-hikitia-accelerating-success-20132017/

Parsons, S. A., Malloy, J. A., Parsons, A. W., Peters-Burton, E. E., & Burrowbridge, S. C. (2016). Sixth-grade students’ engagement in academic tasks. The Journal of Educational Research, 111 (2), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2016.1246408

Pease, R., & Maker, C. J. (2017). Teachers’ perceptions of the Real Engagement in Active Problem Solving (REAPS) model . Manuscript in preparation.

Pease, R. & Maker, C. J. (2017). at the end of the reference, add the following: Department of Disability and Psychoeducational Studies, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA.

Reeve, J. (2012). A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 149–172). New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7

Chapter Google Scholar

Reinoso, J. (2011). Real-life problem solving: Examining the effects of alcohol within a community on the Navajo nation. Gifted Education International, 27 (3), 288–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142941102700306

Riley, T., Webber, M., & Sylva, K. (2017). Real Engagement in Active Problem Solving for Māori boys: A case study in a New Zealand secondary school. Gifted and Talented International, 32 (2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332276.2018.1522240

Shernoff, D. J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Schneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2003). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. School Psychology Quarterly, 18 (2), 158–176. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.18.2.158.21860

Smith, G. A. (2002). Place-based education: Learning to be where we are. Phi Delta Kappan, 83 (8), 584–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170208300806

Sternberg, R. J. (1997). Successful intelligence . New York, NY: Plume.

Sternberg, R. J. (1999). Intelligence as developing expertise. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 24 (4), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1998.0998

Tan, S., Erdimez, O., & Zimmerman, R. (2017). Concept mapping as a tool to develop and measure students’ understanding in science. Acta Didactica Naponcensia, 10 (2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.24193/adn.10.2.9

Urban, K., & Jellen, G. (1996). Test for creative thinking – Drawing production (TCT-DP) . Lisse, Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Wallace, B. (2008). The early seedbed of the growth of TASC: Thinking actively in a social context. Gifted Education International, 24 (2–3), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142940802400303

Wallace, B., Maker, C. J., Cave, D., & Chandler, S. (2004). Thinking skills and problem-solving: An inclusive approach . London, UK: David Fulton Publishers.

Watt, H. M. G., Carmichael, C., & Callingham, R. (2017). Students’ engagement profiles in mathematics according to learning environment dimensions: Developing an evidence base for best practice in mathematics education. School Psychology International, 38 (2), 166–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034316688373

Webber, M., & Macfarlane, A. (2017). The transformative role of tribal knowledge and genealogy in indigenous student success. In L. Smith & E. McKinley (Eds.), Indigenous handbook of education (pp. 1–25). Australia: Springer. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-981-10-1839-8_63-1

Webber, M., Riley, T., Sylva, K., & Scobie-Jennings, E. (2018). The Ruamano project: Raising expectations, realising community aspirations and recognising gifted potential in Māori boys. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education . Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2018.16

Wu, I.-C., Pease, R., & Maker, C. J. (2015). Students’ perceptions of Real Engagement in Active Problem Solving. Gifted and Talented International, 30 (1–2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332276.2015.1137462

Zhou, M., & Ren, J. (2017). A self-determination perspective on Chinese fifth-graders’ task disengagement. School Psychology International, 38 (2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034316684532

Zimmerman, R., Alfaiz, F. S., & Maker, C. J. (2017). Culturally responsive assessments of life science skills and abilities: Development, field testing, and implementation. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Zimmerman, R., & Maker, C. J. (2017). Students’ understanding of the complexity of concepts and their interrelationships in REAPS and comparison classrooms . Manuscript in preparation.

Zimmerman, R. H., Maker, C. J., Gomez-Arizaga, M. P., & Pease, R. (2011). The use of concept maps in facilitating problem solving in earth science. Gifted Educational International, 27 (3), 274–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142941102700305

Zimmerman, R. H., Maker, C. J., & Pease, R. (2017). Fidelity of implementation of the Real Engagement in Active Problem Solving (REAPS) model and student gains in understanding the complexity of concepts and their interrelationships. Manuscript in preparation.

Zimmerman, R. H., Maker, C. J., & Alfaiz, F.S. (2019). Culturally responsive assessments of life science abilities: Development, field testing, and implementation. Manuscript submitted to the Journal of Advanced Academics. Department of Disability and Psychoeducational Studies, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA.

Zimmerman, R. H. & Maker, C. J. (2017). add the following at the end of the reference: Department of Disability and Psychoeducational Studies, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA.

Zimmerman, R. H., Maker, C. J., & Pease, R. (2017). add the following at the end of the reference: Department of Disability and Psychoeducational Studies, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Disability and Psychoeducational Studies, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA

C. June Maker

NSW Department of Education, North Sydney Demonstration School, Waverton, NSW, Australia

Myra Wearne

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to C. June Maker .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

GERRIC, School of Education, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Susen R. Smith

Section Editor information

Faculty of Education, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

James J. Watters

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Maker, C.J., Wearne, M. (2021). Engaging Gifted Students in Solving Real Problems Creatively: Implementing the Real Engagement in Active Problem-Solving (REAPS) Teaching/Learning Model in Australasian and Pacific Rim Contexts. In: Smith, S.R. (eds) Handbook of Giftedness and Talent Development in the Asia-Pacific. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3041-4_40

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3041-4_40

Published : 09 January 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-13-3040-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-13-3041-4

eBook Packages : Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Gifted Lesson Plans: A List of Resources

Below are some of our community’s favorite educator books and websites on lesson plans listed in alphabetical order.*

- 20 Ideas for Teaching Gifted Kids in the Middle School & High School Receive some of the best ideas and lessons developed by master teachers in this book by Joel McIntosh. Both this and its sequel, 10 More Ideas for Teaching Gifted Kids in the Middle School & High School , feature ideas for starting mentorship programs, teaching history using scientific surveys, producing documentaries, and more. A Trip Around the World This book contains lesson plans, maps, facts, words and phrases, and activities are provided for 15 countries on six different continents helping students learn about countries and cultures around the world. Other curriculum areas are incorporated in the activities provided along with teaching notes, blackline maps, extension activities, a list of foreign words and phrases, and a bibliography of fiction and non-fiction books for each country to help to organize the study. Autonomous Learner Model Resource Book This book includes activities and strategies to support the development of autonomous learners. More than 40 activities are included, all geared to the emotional, social, cognitive, and physical development of students. Teachers may use these activities and strategies with the entire class, small groups, or with individuals who are ready to be independent, self-directed, lifelong learners. Challenging Units for Gifted Learners: Teaching the Way Gifted Students Think – Language Arts Challenging Units for Gifted Learners: Teaching the Way Gifted Students Think – Math These books are series designed to help teachers provide the stimulating curricula that will nurture this potential in school. Creating Effective Programs for Gifted Students With Learning Disabilities This book provides a road map for understanding assessment and programming for GTLD students in the era of Response to Intervention. The book helps educators understand the often frustrating experiences GTLD students face in the classroom and identify accommodations and adaptations that allow these bright students to demonstrate their gifts and compensate for their processing challenges. Through an examination of current research and case studies, the reader will be introduced to what must be considered when identifying and developing programming for this underserved population. Demystifying Differentiation in Middle School: Tools, Strategies and Activities to Use NOW A book designed for middle school teachers who are interested in curriculum differentiation. Offers detailed lessons in over 35 topics, such as language arts, math, science, and social studies, covering four different teaching strategies. Differentiated Activities and Assessments Using the Common Core Standards This book show educators how to use differentiated curriculum, differentiated instruction, and differentiated assessment with the Common Core State Standards. The book includes over 50 topics in language arts, math, social studies, science, and interdisciplinary topics. Differentiation That Really Works: Strategies From Real Teachers for Real Classrooms (Grades K-2) This book provides educators with time-saving teaching strategies and lesson ideas based on ease of implementation, ability to modify and inherent opportunities for differentiation. Through years of working with teachers the authors, Dr. Cheryll M. Adams and Dr. Rebecca L. Pierce, pass along four classroom components focused on including differentiated learning strategies, anchoring activities, classroom management, and differentiated assessment. The book also includes templates and sample lessons that can be used to develop customized materials, along with comments from teachers who have used the strategies. Five in a Row The three volumes of the Five in a Row curriculum provide 55 lesson plans covering social studies, language, art, applied math and science. Designed for a homeschool setting, these lessons would also be appropriate in a conventional school. Although the original Five in a Row was designed for children ages 4 to 8, families of profoundly gifted children will find these guides more appropriate for the preschool years. The accompanying Five in a Row website offers sample lessons, an online newsletter, and curriculum user discussion boards. I’m Not Just Gifted: Social-Emotional Curriculum for Guiding Gifted Children What traits and characteristics define successful people? Why do gifted children, in particular, need a strong affective curricula in order to maximize their potential? These questions and more are explored in this guide to helping gifted children in grades 4–7 as they navigate the complicated social and emotional aspects of their lives. Including lesson plans, worksheets, and connections to Common Core State Standards, this is a practical guide necessary for anyone serving and working with gifted children. Instructional Units for Gifted and Talented Learners The creative lessons covered in this book by master teachers cover all of the core academic areas for grades K-6. Lessons include standards-based objectives, interdisciplinary connections that can be explored and discussed and assessments strategies for each unit of instruction. Lessons From the Middle: High-End Learning for Middle School Students In addition to the 12 model lessons provided, this book from Sandra Kaplan and Michael Cannon, includes a step-by-step guide to developing lessons that emphasize depth and complexity. All of the materials focus on ways to align the middle school curriculum with established national standards and offer strategies to evaluate learner achievement. Order in the Court – A Mock Trial Simulation Order in the Court: A Mock Trial Simulation gives students the opportunity to conduct a trial based on a classic fairytale in order to develop their courtroom skills. After developing the necessary vocabulary, students participate in the trial of Ms. Petunia Pig v. Mr. B. B. Wolf. Students not only learn the concepts, but they also learn valuable teamwork and time management skills. Designed for students grades 6-8, the unit culminates in a full mock-trial enactment. Picturing Math This unique book uses picture books to teach elementary students math concepts. Author Colleen Kessler feels strongly that all students should be challenged to experience and learn new things every day. She covers problem solving, geometry, algebra, measurement and probability. Grades 2-4. Project-Based Learning for Gifted Students: A Handbook for the 21st-Century Classroom This book makes the case that project-based learning is ideal for the gifted classroom, focusing on student choice, teacher responsibility, and opportunities for differentiation. The book guides teachers to create a project-based learning environment in their own classroom, walking them step-by-step through topics and processes such as linking projects with standards, finding the right structure, and creating a practical classroom environment. Project-Based Learning for Gifted Students also provides helpful examples and lessons that all teachers can use to get started. Ready-to-Use Differentiation Strategies – Grades 6-8 Ready-to-Use Differentiation Strategies introduces various activities and strategies that can be implemented in any content area in grades 6–8. Each differentiation strategy encourages higher level thinking and intellectual risk taking while accommodating different learning styles. This book also provides templates that can be used to develop new lessons using each strategy. Designed for students grades 6-8, Ready-to-Use Differentiation Strategies provides an easy-to-use way to begin differentiating for all students in the classroom. Researching All Learners: Making Differentiation Work This book provides research-based strategies, instructional responses to the way students’ brains learn best, successful guidelines to effectively manage the learning environment, and a teaching palette of 40 strategies for differentiating instruction. Splash! Monitoring and Measurement Applications for Young Learners This book is a mathematics unit for high-ability learners in kindergarten and first grade focusing on concepts related to linear measurement, the creativity elements of fluency and flexibility, and the overarching, interdisciplinary concept of models. The unit consists of 13 lessons centered on the idea of designing a community pool. Students examine the question of why we measure, the importance of accuracy in measurement, and the various units and tools of measurement. STEM to STEAM Education for Gifted Students: Using Specific Communication Arts Lessons with Nanotechnology, Solar, Biomass, Robotics, & Other STEM Topics In this book, the authors present detailed lessons for integrating Eight STEM Education Areas with Communication Arts Lessons. These detailed lessons emphasize writing essays, descriptions and poems, and completing various exercises related to the following STEM Areas: Nanotechnology, Solar, Internet, Inventing, Music, Electric Vehicles, MOOCS, Biomass, and Robotics. The Appendices contain further information about the importance and promise of STEM Education. Super Smart Math – 180 Warm-Ups and Challenging Activities In Super Smart Math challenges, author Rebecca George helps students to think critcally while providing activities and problems that become increasingly difficult as the students progress through each section. Organized by mathematical topics for grades 5-8. The 10 Things All Future Mathematicians and Scientists Must Know (But Are Rarely Taught) Edward Zaccaro presents this book full of classroom lessons, readings and discussion starters. It reveals the things our future mathematicians and scientists must know in order to prevent tragedies such as the Challenger explosion and the failure of the Mars Orbiter. The NEW RtI: Response to Intelligence This book provides practical advise for instructors who are looking to successfully incorporate students of all skill levels into their classroom. The book advocates for gifted children while supporting the concept that all children on the learning continuum grow and continue to learn. Unicorns Are Real: A Right-Brained Approach to Learning This best-seller by Barbara Meister Vitale, provides sixty-five practical, easy-to-follow lessons to develop the much ignored right-brain tendencies of children. Her methods have been successfully demonstrated at workshops, in-service training sessions, and at several major educational conventions nationwide. Writing Instruction for Verbally Talented Youth: The Johns Hopkins Model The book by Ben Reynolds contains specific lesson plans, student assignments, and criteria and suggestions for evaluation of student work. The book contains the complete content of the first writing courses for verbally talented youth designed by the Center for Talented Youth at Johns Hopkins University in the early 1980’s. This course was designed originally for 7th grade students who scored 430 or above on the verbal section of the SAT. Writing Success Through Poetry Grades 4-8 will gain insight from this book offering practical questions to facilitate Socratic-style discussions and explorations of literary concepts found within poems. Author, Susan Lipson, provides 25 original poems as prompts for students to use as inspiration for their own poetry and prose.

Engineering the Future offers lessons, activities, and classroom strategies to assist educators in teaching young people STEM oriented content.

* Some links on this page go to Bookshop.org and are affiliate links. While these books are available from many retailers, all links that go to Bookshop.org help support the Davidson Institute’s mission and continuing work to support profoundly gifted students and their families.

Feel free to share your go-to gifted education resources in the comments below!

Share this post

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share via email

Diane Wiktorowski

Add a comment.

Please note, the Davidson Institute is a non-profit serving families with highly gifted children. We will not post comments that are considered soliciting, mention illicit topics, or share highly personal information.

Post Comment

Related Articles

What your therapist needs to know about giftedness.

Dr. Gail Post, a Clinical Psychologist with over 35 years of experience, discusses the cognitive, social and emotional impact of…

Barriers in Gifted Education: Working Together to Support Gifted Learners and Families

The mission of the Davidson Institute is to recognize, nurture and support profoundly intelligent young people and to provide opportunities…

Homeschooling Curriculum for the Gifted Child

In the article “Homeschooling Curriculum for the Gifted Child,” published by the Davidson Institute, author Sarah Boone offers an in-depth…

Gifted Homeschooling and Socializing

This article offers insights into the various ways parents can help their gifted children build social skills and meaningful relationships…

This is editable under form settings.

- Full Name *

- Email Address *

- Comment * Please note, the Davidson Institute is a non-profit serving families with highly gifted children. All comments will be submitted for approval before posting publicly. We will not post comments that are considered soliciting, mention illicit topics, or share highly personal information.

Suggest an update

Six Strategies for Challenging Gifted Learners

But first, the big picture, 1. offer the most difficult first, 2. pre-test for volunteers, 3. prepare to take it up, 4. speak to student interests, 5. enable gifted students to work together, 6. plan for tiered learning, "it's just good teaching".

Premium Resource

Amy Azzam is a freelance writer and former senior associate editor of Educational Leadership .

ASCD is a community dedicated to educators' professional growth and well-being.

Let us help you put your vision into action., related articles.

Saving the Ocean, One Student at a Time

Making Math More Relevant

Back On Track with Climate Science

Meeting Students Where They Are

Helping Students Give Back

To process a transaction with a purchase order please send to [email protected].

- Camp Invention (K-6th)

- Camp Invention Connect (K-6th)

- Refer a Friend Rewards Program

- Club Invention (1st-6th)

- Leaders-in-Training (7th-9th)

- Leadership Intern Program (High School & College Students)

- About the Educators

- FAQs for Parents

- Parent Resource Center

- Our Programs

- Find a Program

- Professional Development

- Resources for Educators

- FAQs for Educators

- Program Team Resource Center

- Plan Your Visit

- Inductee Search

- Nominate an Inventor

- Newest Inductees

- Induction Ceremony

- Our Inductees

- Apply for the Collegiate Inventors Competition

- CIC Judging

- Meet the Finalists

- Past CIC Winners

- FAQs for Collegiate Inventors

- Collegiate Inventors Competition

- Register for 2024 Camp

- Learning Resources

- Sponsor and Donate

3 Strategies for Supporting Gifted and Talented Students

While gifted and talented (G&T) students have many heightened skill sets and abilities, if not supported properly, they risk falling behind in school despite the lack of national attention compared to other student demographics.

One reason for this is the prevailing myth that G&T students should be able to excel on their own. According to the National Association for Gifted Children , the truth is that without proper support and guidance, these students can easily become bored and frustrated, leading to “low achievement, despondency, or unhealthy work habits.”

Below are three strategies you can implement in your classrooms to help G&T students reach their full potential.

1. Combat Perfectionism

While every student is different and has unique social and emotional needs, research shows that G&T students on average feel more isolated and are less sensitive to how their peers perceive them. Additionally, students may suffer from anxiety, social withdrawal, low self-esteem and excessive perfectionism . These negative emotions can feel magnified, especially if children feel like they are overwhelmed with expectations set by teachers or parents.

According to the Institute for Educational Advancement (IEA), a nonprofit organization that focuses on supporting the academic needs and opportunities of gifted children, around 20% of gifted children suffer from perfectionism to the point where it causes problems.

A few tips recommended by the IEA to address this include:

- Speaking to students honestly about your own mistakes and how these setbacks led to future success.

- Promoting the importance of the process as opposed to the outcome of a particular project.

- Help them find humor in mistakes and encourage them to not take mistakes so seriously.

- Encourage them to remove the idea of “being perfect” from their identity.

- Set limits and help them set boundaries on the amount of time they’re working on any one task or assignment.

2. Embrace Enrichment Opportunities

Incorporating enrichment opportunities has long represented a crucial cornerstone of effective G&T education. In a paper published in Education Sciences , researchers trace this national approach to as early as 1985, when researchers first began categorizing different types of enrichment based on their intended outcomes and use cases.

Today, there exist significantly more types of enrichment for students. As highlighted in the report, types that are of particular interest to G&T students include :

- Strength-Based Learning Opportunities This strategy considers students’ academic strengths, interests and learning preferences to create activities that are both naturally appealing and designed to further develop their natural strengths and interests.

- Critical/Creative Thinking and Problem Solving These learning opportunities are designed to provide students with opportunities to use critical and creative thinking and problem solving to interpret a challenge and then use open-ended thinking to produce multiple ideas and solutions.

- Differentiated Instruction (Curriculum Compacting) Targeted to Student Needs In this approach, instructional and curricular modifications are made to meet the needs of students on an individual level to ensure that instruction and content are more challenging and advanced, as needed.

3. Consider Invention Education

One effective way to implement the above enrichment styles is through invention education, a hands-on pedagogy that challenges students to solve real-world problems by building invention prototypes.

With this strategy, not only do G&T students have the opportunity to pursue solutions that most interest them, but because such projects are open-ended in nature, they invite students to develop their critical thinking and problem-solving skills. In this way, invention education allows for naturally occurring differentiated instruction, giving students full autonomy as to how they want to solve a given problem or challenge.

In Florida’s Pinellas County School District, district officials partnered with the National Inventors Hall of Fame ® to support their G&T students using our engaging invention education curricula. To learn more about their experience, we invite you to check out this blog !

Find More Education Strategies

Visit our blog for more ideas and resources you can use to support your students.

Related Articles

Bring 3 nostalgic memories to life this summer, acknowledging inductee contributions on armed forces day, 3 ways students benefit from hands-on learning.

- Summative Assessment Techniques: An Overview

- Understanding Curriculum Mapping

- Engaging Hands-on Activities and Experiments

- Life Science Lesson Plans for 9-12 Learners

- Classroom Management

- Behavior management techniques

- Classroom rules

- Classroom routines

- Classroom organization

- Assessment Strategies

- Summative assessment techniques

- Formative assessment techniques

- Portfolio assessment

- Performance-based assessment

- Teaching Strategies

- Active learning

- Inquiry-based learning

- Differentiated instruction

- Project-based learning

- Learning Theories

- Behaviorism

- Social Learning Theory

- Cognitivism

- Constructivism

- Critical Thinking Skills

- Analysis skills

- Creative thinking skills

- Problem-solving skills

- Evaluation skills

- Metacognition

- Metacognitive strategies

- Self-reflection and metacognition

- Goal setting and metacognition

- Teaching Methods and Techniques

- Direct instruction methods

- Indirect instruction methods

- Lesson Planning Strategies

- Lesson sequencing strategies

- Unit planning strategies

- Differentiated Instruction Strategies

- Differentiated instruction for English language learners

- Differentiated instruction for gifted students

- Standards and Benchmarks

- State science standards and benchmarks

- National science standards and benchmarks

- Curriculum Design

- Course design and alignment

- Backward design principles

- Curriculum mapping

- Instructional Materials

- Textbooks and digital resources

- Instructional software and apps

- Engaging Activities and Games

- Hands-on activities and experiments

- Cooperative learning games

- Learning Environment Design

- Classroom technology integration

- Classroom layout and design

- Instructional Strategies

- Collaborative learning strategies

- Problem-based learning strategies

- 9-12 Science Lesson Plans

- Life science lesson plans for 9-12 learners

- Earth science lesson plans for 9-12 learners

- Physical science lesson plans for 9-12 learners

- K-5 Science Lesson Plans

- Earth science lesson plans for K-5 learners

- Life science lesson plans for K-5 learners

- Physical science lesson plans for K-5 learners

- 6-8 Science Lesson Plans

- Earth science lesson plans for 6-8 learners

- Life science lesson plans for 6-8 learners

- Physical science lesson plans for 6-8 learners

- Science Instruction

- Differentiated Instruction Strategies for Gifted Students

This article covers everything you need to know about Differentiated Instruction Strategies for Gifted Students, including best practices and examples.

It enables teachers to identify the strengths and weaknesses of each student and to provide instruction that is tailored to the individual’s learning style and needs. Differentiated instruction is especially important for gifted students , as they often have unique learning needs that require specialized instruction. It is important to differentiate instruction for gifted students because they often possess a wide range of abilities, which require different levels of instructional support. For example, a gifted student may excel in math, but struggle with reading comprehension.

By differentiating instruction, teachers can ensure that all students receive an education that meets their individual needs. Differentiating instruction for gifted students involves providing instruction that is tailored to their unique abilities and needs. This can include increasing the level of complexity in assignments, providing additional opportunities for enrichment, and allowing students to work at their own pace. Additionally, teachers should create activities that challenge gifted students without overwhelming them, and provide opportunities for creative problem solving.

To effectively differentiate instruction for gifted students, teachers must first identify the needs of each student. This can be done by observing student behavior, assessing student work, and speaking with parents and other teachers. Once these needs have been identified, teachers can develop differentiated instruction plans that provide appropriate challenges and support for each student. When creating differentiated instruction plans, teachers should consider the student’s interests, strengths, and weaknesses.

For example, if a gifted student is highly advanced in math, the teacher could create an individualized plan that provides challenging math assignments while also providing additional support in weaker areas such as reading comprehension or writing skills. By providing individualized instruction plans for each student, teachers can ensure that all students are receiving the support they need to succeed. Differentiating instruction for gifted students also involves providing activities that challenge them without overwhelming them. This can be done by allowing students to work at their own pace and by providing enrichment activities that are tailored to their interests and abilities.

Differentiation Strategies for Gifted Students

Content differentiation, process differentiation, product differentiation, environment differentiation, curriculum-based differentiation, best practices for differentiated instruction for gifted students.

By understanding each student’s unique abilities and needs, teachers can create personalized learning experiences that will engage and challenge them. Teachers can assess each student’s current knowledge and areas of need in order to provide the most appropriate instruction for their individual needs. Providing flexible learning environments is also important for providing effective differentiated instruction for gifted students. Teachers can create a variety of learning experiences that will engage and challenge the students. This includes providing multiple pathways to demonstrate mastery of content, allowing choice in how they participate in activities, and offering a range of activities that vary in complexity.

Additionally, teachers can provide options for students to work independently or in small groups depending on their individual preferences. Allowing students to take ownership of their learning is another important component of differentiated instruction for gifted students. Teachers should give students the autonomy to explore their interests and take control of their own learning. This could include providing opportunities for student-led research projects, allowing students to choose the topics they would like to learn more about, and giving them time to explore their ideas through creative projects or activities. Finally, utilizing technology is an important part of providing effective differentiated instruction for gifted students. Technology can be used to provide engaging and meaningful learning experiences that meet the needs of each student.

Teachers can use technology to create personalized learning paths and interactive activities that will challenge and engage gifted students. Additionally, technology can be used to facilitate collaboration between students and allow them to share their ideas in a safe and engaging environment. By utilizing these best practices, teachers can provide effective differentiated instruction for gifted students. Through recognizing individual student needs, providing flexible learning environments, allowing students to take ownership of their learning, and utilizing technology, teachers can create personalized learning experiences that will engage and challenge gifted students. Examples of how these practices can be implemented in the classroom include providing multiple pathways to demonstrate mastery of content, allowing choice in how they participate in activities, offering a range of activities that vary in complexity, providing opportunities for student-led research projects, allowing students to choose the topics they would like to learn more about, and giving them time to explore their ideas through creative projects or activities. Differentiated instruction is an important strategy for ensuring that gifted students receive the appropriate level of academic challenge.

This article discussed a variety of strategies for differentiating instruction, such as tiered assignments, flexible grouping, and self-paced learning. It also explored best practices to ensure effective differentiated instruction, including providing clarity of expectations, providing choice within assignments, and allowing for individualized support. Finally, this article provided examples of how to implement differentiated instruction in the classroom. By applying these strategies and best practices, educators can create an optimal learning environment for gifted students. In conclusion, differentiated instruction is an effective way to provide gifted students with an appropriate level of challenge and support.

Educators should use the strategies discussed in this article to create an optimal learning environment for gifted students in their classrooms.

- specialized

Shahid Lakha

Shahid Lakha is a seasoned educational consultant with a rich history in the independent education sector and EdTech. With a solid background in Physics, Shahid has cultivated a career that spans tutoring, consulting, and entrepreneurship. As an Educational Consultant at Spires Online Tutoring since October 2016, he has been instrumental in fostering educational excellence in the online tutoring space. Shahid is also the founder and director of Specialist Science Tutors, a tutoring agency based in West London, where he has successfully managed various facets of the business, including marketing, web design, and client relationships. His dedication to education is further evidenced by his role as a self-employed tutor, where he has been teaching Maths, Physics, and Engineering to students up to university level since September 2011. Shahid holds a Master of Science in Photon Science from the University of Manchester and a Bachelor of Science in Physics from the University of Bath.

New Articles

- Instructional Software and Apps: A Comprehensive Overview

This article provides a comprehensive overview of instructional software and apps, outlining their features and benefits.

- Evaluation Skills: A Comprehensive Overview

This article provides an overview of evaluation skills, including what they are, why they are important, and how to develop them. It is written for anyone interested in improving their science learning and critical thinking skills.

- Understanding Cognitivism: A Learning Theory

Discover what cognitivism is, how it works and why it's an important learning theory

- Formative Assessment Techniques

Learn about the different formative assessment techniques, why they are important, and how to use them effectively in the classroom.

Leave Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

I agree that spam comments wont´t be published

- Behavior Management Techniques

- Behaviorism: A Comprehensive Overview

- Social Learning Theory Explained

- Active Learning: A Comprehensive Overview

- Inquiry-Based Learning: An Introduction to Teaching Strategies

- Analysis Skills: Understanding Critical Thinking and Science Learning

- Creative Thinking Skills

- Constructivism: Exploring the Theory of Learning

- Problem-solving Skills: A Comprehensive Overview

- Classroom Rules - A Comprehensive Overview

- Exploring Portfolio Assessment: An Introduction

Differentiated Instruction: A Comprehensive Overview

- Classroom Routines: A Comprehensive Overview

- Effective Classroom Organization Strategies for Science Teaching

- Project-Based Learning: An In-Depth Look

- Performance-Based Assessment: A Comprehensive Overview

- Understanding Direct Instruction Methods

- State Science Standards and Benchmarks

- Course Design and Alignment

- The Advantages of Textbooks and Digital Resources

- An Overview of Metacognitive Strategies

Backward Design Principles: Understanding Curriculum Design

- Engaging Cooperative Learning Games

- Integrating Technology into the Classroom

- Understanding Classroom Layout and Design

- Lesson Sequencing Strategies: A Comprehensive Overview

- Collaborative Learning Strategies

- Indirect Instruction Methods: A Comprehensive Overview

- Understanding National Science Standards and Benchmarks

- Exploring Problem-Based Learning Strategies

- Unit Planning Strategies

- Exploring Self-Reflection and Metacognition

- Exploring Goal Setting and Metacognition

- Earth Science Lesson Plans for K-5 Learners

- Differentiated Instruction for English Language Learners

Life Science Lesson Plans for K-5 Learners

- Earth Science Lesson Plans for 6-8 Learners

- Earth Science Lesson Plans for 9-12 Learners

- Life Science Lesson Plans for 6-8 Learners

- Physical Science Lesson Plans for 9-12 Learners

- Physical Science Lesson Plans for K-5 Learners

- Physical Science Lesson Plans for 6-8 Learners

Recent Posts

Which cookies do you want to accept?

Log-in from the menu to join our email list

welcome to solving fun

Solving fun shares.

A blog about games, education, parenting, and other crazy things that pop up in daily life.

- Hillary Miller

- Oct 4, 2023

Creative thinking, engagement, and perseverance: How puzzles directly support gifted students

Updated: Jan 26

Creative thinking sparks innovation and problem-solving. When coupled with perseverance, creativity becomes an unstoppable force. For gifted children, whose minds are brimming with potential, fostering creative thinking, engagement, and perseverance is paramount.

Gifted children are a unique group who possess exceptional cognitive abilities. These abilities can span various domains, such as mathematics, science, language, music, and the arts. Gifted children often exhibit an insatiable curiosity, a penchant for deep exploration, and a voracious appetite for learning.

The Significance of Creative Thinking, Engagement, and Perseverance

Creative Thinking ignites innovation. It enables children to approach problems from unconventional angles, generate new ideas, and connect seemingly unrelated concepts. Creative thinking is the bridge between knowledge and innovation, and it is vital for solving complex, real-world problems.

Engagement in learning is the driving force behind sustained interest and motivation. When children are engaged in their learning, they are more likely to invest time and effort, leading to deeper understanding and higher achievement. It fosters a love for learning that extends beyond the classroom.

Perseverance is the ability to persist in the face of challenges and setbacks. It is the fuel that keeps the creative engine running. For gifted children, who often encounter complex problems and high expectations, perseverance is a critical trait that leads to long-term success.

Puzzles, like those Solving Fun creates, are a applicative tool for nurturing creative thinking, engagement, and perseverance in gifted children. Here's why:

Cognitive Stimulation: Logic puzzles challenge the mind and promote creative problem-solving. They require solvers to use their critical thinking skills to deduce patterns and solutions, enhancing their cognitive abilities.

Versatility: Puzzles come in various levels of difficulty, allowing parents and educators to tailor the puzzles to a child's abilities. This adaptability ensures that the puzzles remain engaging and challenging.

Enjoyment and Engagement: Puzzles from Solving Fun are specifically designed to be interesting and engaging for various types of thinkers. When children find learning fun, they are more likely to be motivated and deeply engaged in the problem-solving process.

Perseverance Building: Logic and wordplay puzzles inherently require perseverance. They present challenges that may not have immediate solutions, teaching solvers the value of persistence and the satisfaction of overcoming obstacles; a lesson that generalizes to many different situations.

Incorporating Logic Puzzles into Gifted Education

To effectively harness the benefits of logic puzzles in your class and to promote perseverance, consider the following strategies:

Identify Interests: Recognize the areas of interest and strengths of the child. Select puzzles that align with their passions to foster engagement and perseverance.

Gradual Progression: Begin with puzzles of moderate difficulty and gradually increase complexity as the child's skills improve. This progression ensures that the child remains challenged and engaged, promoting perseverance.

Encourage Reflection: Encourage gifted children to reflect on their problem-solving strategies and creative thinking processes. This self-awareness promotes metacognition, which is valuable for lifelong learning and perseverance.

Celebrate Achievements and Effort: Celebrate both small and significant achievements. Praise the child's effort and perseverance in tackling challenging puzzles. Positive reinforcement encourages continued engagement and perseverance.

Creative thinking, engagement, and perseverance are the cornerstones of nurturing the potential of gifted children. Puzzles provide an exciting and effective means to enhance creative thinking skills, promote engagement, and build perseverance in these young minds. By fostering creative, engaged, and persistent learners, we empower gifted children to tackle future challenges, make meaningful contributions to society, and continue to push the boundaries of human knowledge and innovation.

For more strategies to help facilitate creative thinking, check out Solving Fun’s Solving Guide at www.solvingfun.com/solvingguide or contact us at [email protected].

- Parents/Educators Blog

Recent Posts

Puzzle Solving Benefits for Kids

How to Teach Perseverance: 8 Strategies for Kids That Give Up

Logic Puzzles for Gifted Students

Do you ever ask yourself “How can I challenge my gifted and talented students in math?”

Gifted and talented students make up approximately 10% of students in each class. As educators, it’s our responsibility to provide these students with challenging and engaging learning opportunities to help them reach their full potential!

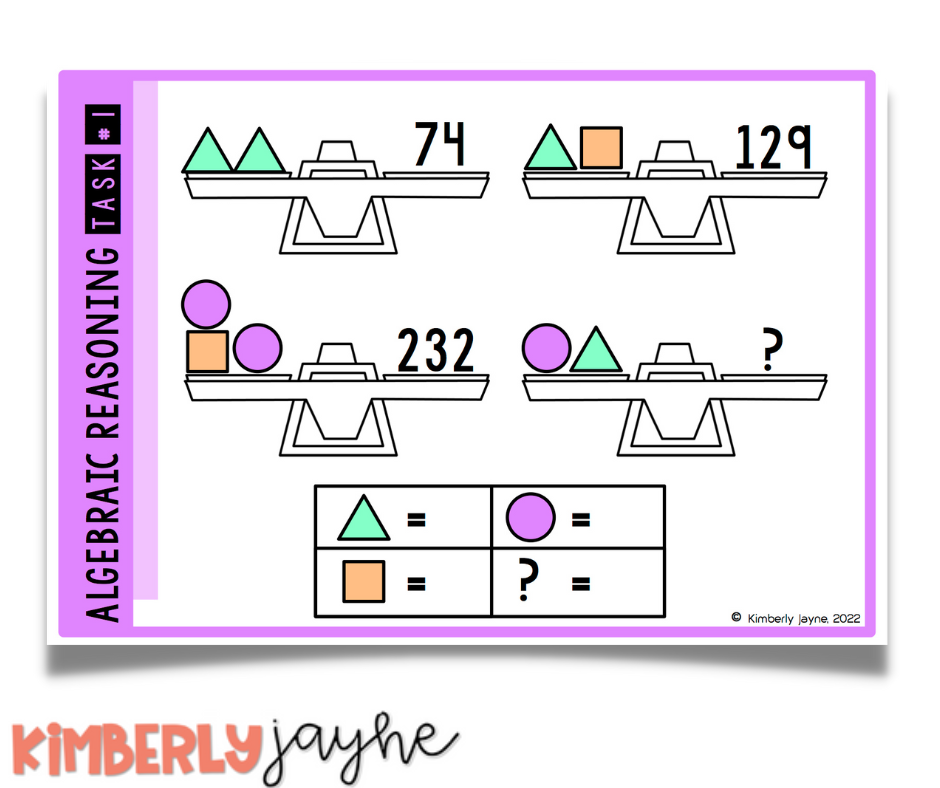

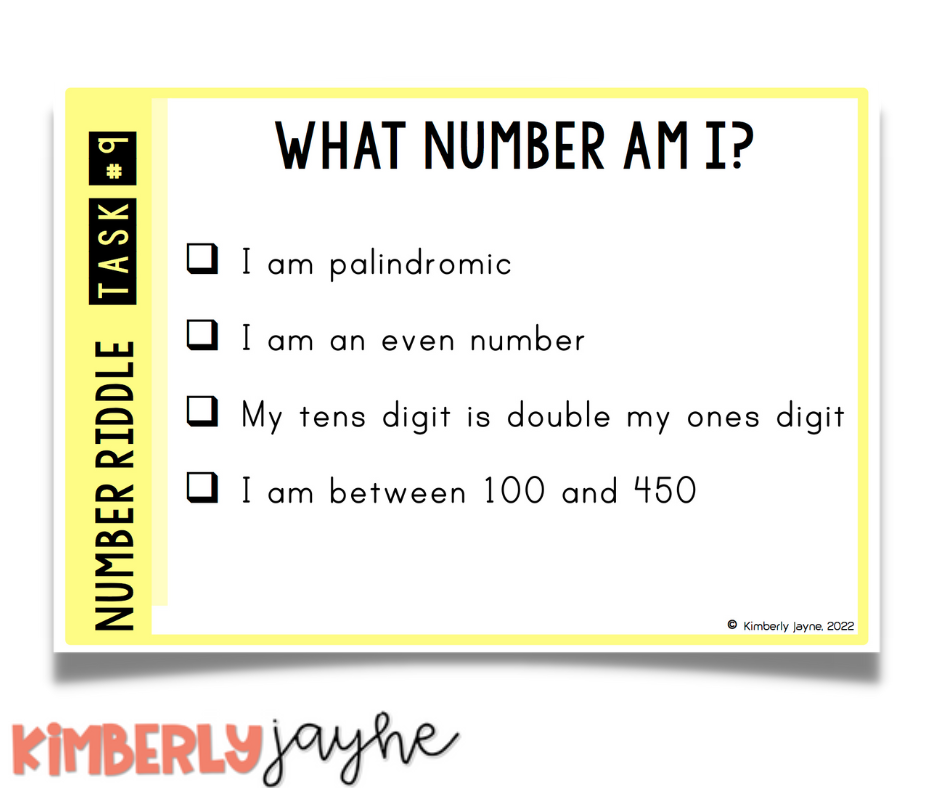

One way to challenge gifted and talented students is by incorporating math logic puzzles into the classroom. Math logic puzzles are fun and engaging challenges that require critical thinking, problem solving, reasoning, and logic skills. They come in many forms, including Sudoku, brain teasers, algebraic reasoning puzzles and more. These puzzles provide a great opportunity for gifted and talented students to develop their skills and to be challenged in a way that is both fun and rewarding.

Make sure you scroll to the end for some FREE logic puzzles for gifted and talented students to try in your classroom!

What are Logic Puzzles?

So, what’s the deal with math logic puzzles?

Alright, let’s break it down: math logic puzzles are basically fun little challenges that make you think critically and logically.

You might have done Sudoku, brain teasers or algebraic reasoning puzzles before. Those are all examples of math logic puzzles.

But why are these puzzles so great? Well, they’re like brain workouts, they help improve your critical thinking skills, problem solving abilities, and reasoning skills.

Plus, they’re just plain fun! There’s something satisfying about finally cracking a tricky puzzle after working on it for a while.

Not only are they fun, but the challenge of solving a logic puzzle produces dopamine in the brain. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that’s associated with feelings of pleasure and reward, and it’s released when we accomplish something challenging or exciting. This means that solving a puzzle makes you feel good!

This means that incorporating math logic puzzles into the classroom can increase engagement among gifted and talented students. When students are engaged in their learning, they’re more likely to participate, stay focused, and retain information. By providing challenging and fun math logic puzzles, you can help keep your gifted students engaged and motivated to learn.

How Can I Use Logic Puzzles?

Here are some tips for using math logic puzzles to challenge gifted and talented students in your classroom:

Warm-up: Include a problem in a whole class warm-up to help engage students in the math lesson and switch on students’ critical thinking skills.

Whole Class Lesson: When I first introduce logic puzzles to my students I do it in a whole class lesson. I display the full-sized version on my Interactive Whiteboard, and we work through each line together. I use lots of think aloud statements e.g. “We know that the llama equals 5 and the answer is 15, so what could the missing value be?”

Math Centres: I print out the task cards and have them ready to go for independent math centres. Having the different levels makes it so easy to give each group a level that not only challenges them, but also allows them to work independently.

Early Finishers: We’ve all had that student that finished their work super-fast and craves a challenge! These logic puzzles are perfect early finisher tasks that engage and challenge students in meaningful work.

Plenary: End a math lesson on operations using logic puzzles to review the lesson objectives and consolidate learning.

By incorporating math logic puzzles into your teaching practices, you can challenge and engage your gifted and talented students in a fun and meaningful way. Happy puzzling!

Examples of Math Logic Puzzles for Gifted and Talented Students

There are many types of math logic puzzles that can be used to challenge gifted and talented students . Here are some examples:

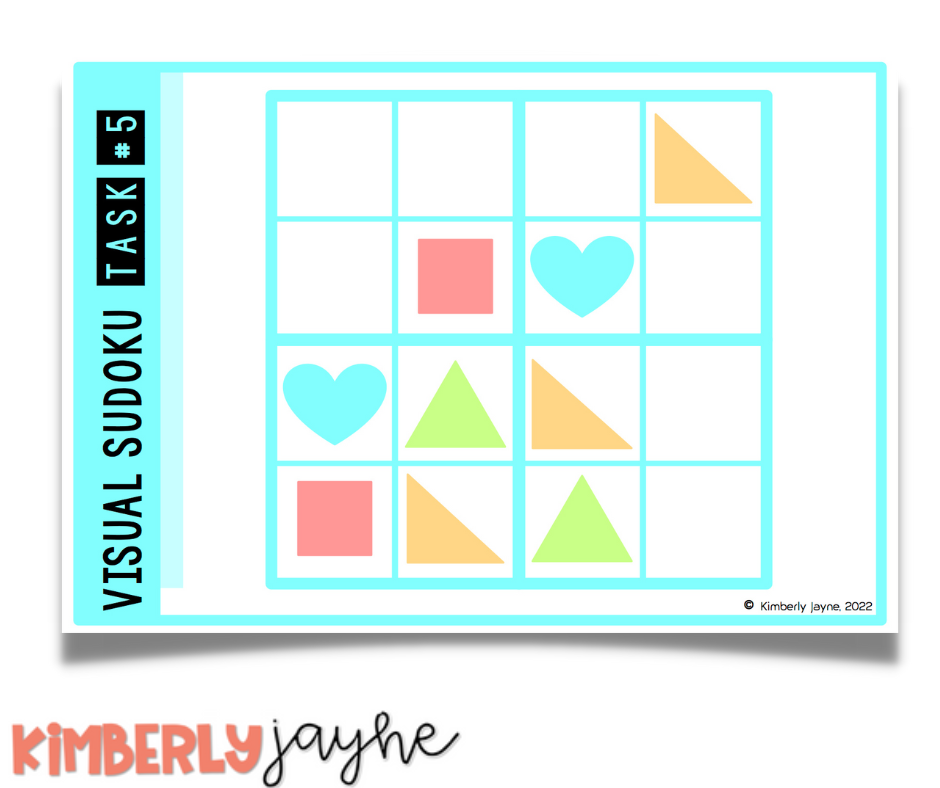

Sudoku: This classic number puzzle requires players to fill in a grid with numbers so that each row, column, and sub grid contains every number from 1 to 9. These can also be visual pictures rather than numbers.

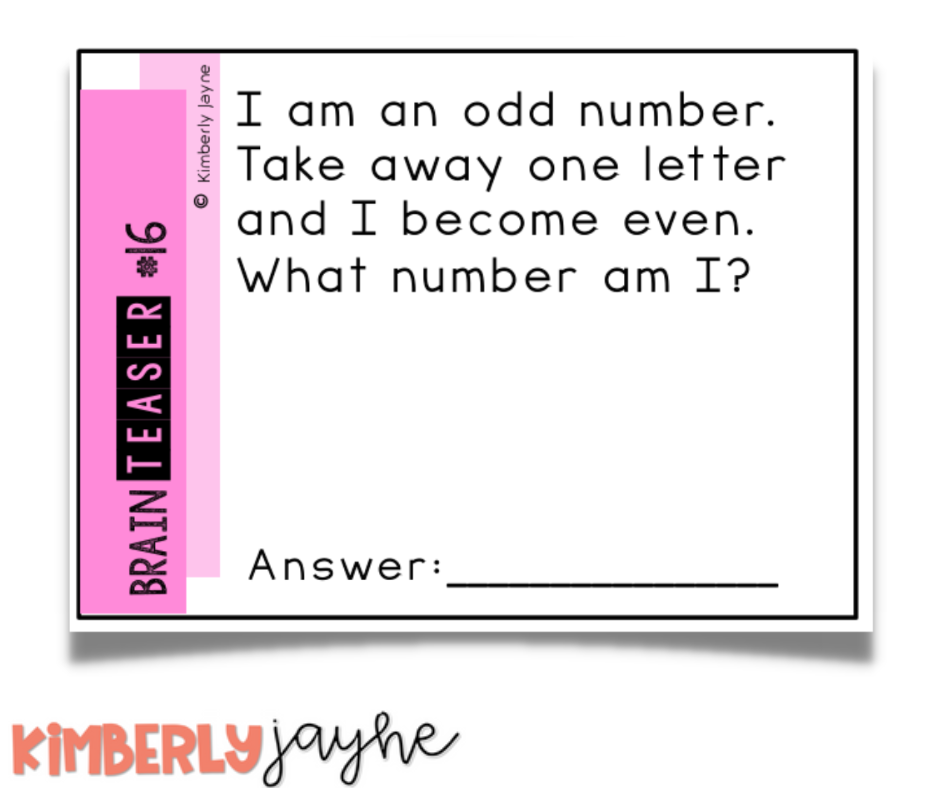

Brain teasers: These puzzles involve a question or statement that requires critical thinking and problem-solving to solve. For example, a riddle might ask “What is always in front of you but can’t be seen?” (Answer: the future).

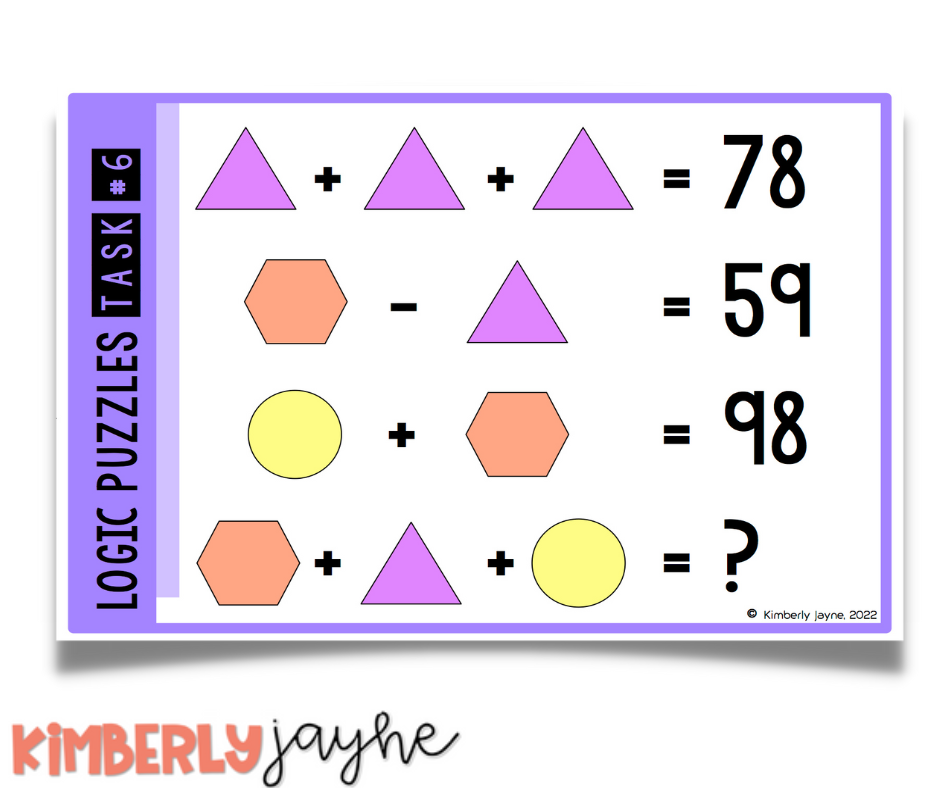

Arithmetic puzzles: These puzzles require players to use basic arithmetic operations to solve problems. For example, a puzzle might replace number using pictures and students need to determine the missing numbers in a sequence of equations using given information.

Algebraic reasoning puzzles: These puzzles require players to use algebraic concepts to solve problems. For example, a puzzle might ask students to determine the value of a variable based on an equation and a set of given conditions.

“What number am I?” riddles: These puzzles involve a set of clues that students use to determine a number that satisfies all of the given conditions. For example, a riddle might ask “I am a two-digit number. I am a multiple of 3. The sum of my digits is 9. What number am I?” (Answer: 27)

As a teacher, you can find many resources for logic puzzles that you can use in your classroom in my tpt store and on my website.

So there you have it! Math logic puzzles can be a great way to challenge and engage your gifted and talented students in the classroom. By using puzzles like Sudoku, brain teasers, algebraic reasoning puzzles, and more, you can help your students develop critical thinking and problem solving skills while also having a bit of fun with maths.

The best part? Research has shown that challenges like math logic puzzles can actually produce dopamine in the brain, which can boost motivation and engagement in the classroom.

You can find a heap of resources to support you to challenge you gifted students on my website

and TPT store .

If you want to try out some FREE logic puzzles you can grab them here.

So why not give it a try and see what your students think? They might just surprise you with their logic and problem solving skills.

Similar Posts

6 Myths About Gifted and Talented Students

Myth 1: Gifted students are good at everything! This simply isn’t true! When I asked my daughter’s pre-primary teacher if she thought she could be gifted (not a question I asked lightly) she said “no, because she isn’t good at everything.” Boy was she wrong! Formal assessment later showed her to be gifted. She has…

Unlocking Creativity: Lateral Thinking Activities for Gifted and Talented Learners

Do you find yourself pulling your hair out trying to think of ways to provide enrichment for your gifted and talented learners? Challenging gifted and talented students in a mainstream classroom can feel like a daunting task! I am going to show you how to can cater to your high ability students in the classroom…

Home > GRADSCHOOL > GRADSCHOOL_THESES > 1872

LSU Master's Theses

Problem solving strategies and metacognitive skills for gifted students in middle school.

etd-07092014-080739

Lorena Aguelo Java , Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow

Master of Natural Sciences (MNS)

Mathematics

Document Type

This study is conducted to investigate if the designed four-step method strategy (GEAR strategy adapted from Polya, 1973) in solving math problems has improved students’ performance scores and enhanced the metacognitive skills of gifted students. The respondents of this study include middle school gifted students who took math eight course in the school year 2013-2014 at Westdale Middle School in East Baton Rouge Parish School System. There are four classes of math eight gifted students who participated in the study. The classes were chosen randomly for experimental and controlled group and were equalized on the basis of the pre-test results of the Module 1 Edusoft Test and the Metacognitive Activities Inventory (MCAI) questionnaire form. During the 4-week period, the experimental group received GEAR strategy while the controlled group used any method they had learned in solving math word problems systematically or nonsystematical way. After the 4-week training period, the results of paired-sample t-test showed that the experimental group’s post-test scores on Module 2 Edusoft test have increased but not overwhelmingly, however, there is a significant difference of their MCAI post-test. The results imply that GEAR strategy does affect the metacognitive skills of middle school gifted students in problem solving and creates a marginal improvement on their classroom performance. This study provides the discussions, implications, and suggestions.

Document Availability at the Time of Submission

Release the entire work immediately for access worldwide.

Recommended Citation

Java, Lorena Aguelo, "Problem Solving Strategies and Metacognitive Skills for Gifted Students in Middle School" (2014). LSU Master's Theses . 1872. https://repository.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/1872

Committee Chair

Harhad, Ameziane

10.31390/gradschool_theses.1872

Since January 07, 2017

Included in

Applied Mathematics Commons

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

Author Corner

- Submit Thesis

SPONSORED BY

- LSU Libraries

- LSU Office of Research and Economic Development

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

- Open access

- Published: 11 May 2024

Nursing students’ stressors and coping strategies during their first clinical training: a qualitative study in the United Arab Emirates

- Jacqueline Maria Dias 1 ,

- Muhammad Arsyad Subu 1 ,

- Nabeel Al-Yateem 1 ,

- Fatma Refaat Ahmed 1 ,

- Syed Azizur Rahman 1 , 2 ,

- Mini Sara Abraham 1 ,

- Sareh Mirza Forootan 1 ,

- Farzaneh Ahmad Sarkhosh 1 &

- Fatemeh Javanbakh 1

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 322 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

257 Accesses

Metrics details

Understanding the stressors and coping strategies of nursing students in their first clinical training is important for improving student performance, helping students develop a professional identity and problem-solving skills, and improving the clinical teaching aspects of the curriculum in nursing programmes. While previous research have examined nurses’ sources of stress and coping styles in the Arab region, there is limited understanding of these stressors and coping strategies of nursing students within the UAE context thereby, highlighting the novelty and significance of the study.

A qualitative study was conducted using semi-structured interviews. Overall 30 students who were undergoing their first clinical placement in Year 2 at the University of Sharjah between May and June 2022 were recruited. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim and analyzed for themes.

During their first clinical training, nursing students are exposed to stress from different sources, including the clinical environment, unfriendly clinical tutors, feelings of disconnection, multiple expectations of clinical staff and patients, and gaps between the curriculum of theory classes and labatories skills and students’ clinical experiences. We extracted three main themes that described students’ stress and use of coping strategies during clinical training: (1) managing expectations; (2) theory-practice gap; and (3) learning to cope. Learning to cope, included two subthemes: positive coping strategies and negative coping strategies.

Conclusions

This qualitative study sheds light from the students viewpoint about the intricate interplay between managing expectations, theory practice gap and learning to cope. Therefore, it is imperative for nursing faculty, clinical agencies and curriculum planners to ensure maximum learning in the clinical by recognizing the significance of the stressors encountered and help students develop positive coping strategies to manage the clinical stressors encountered. Further research is required look at the perspective of clinical stressors from clinical tutors who supervise students during their first clinical practicum.

Peer Review reports

Nursing education programmes aim to provide students with high-quality clinical learning experiences to ensure that nurses can provide safe, direct care to patients [ 1 ]. The nursing baccalaureate programme at the University of Sharjah is a four year program with 137 credits. The programmes has both theoretical and clinical components withs nine clinical courses spread over the four years The first clinical practicum which forms the basis of the study takes place in year 2 semester 2.

Clinical practice experience is an indispensable component of nursing education and links what students learn in the classroom and in skills laboratories to real-life clinical settings [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. However, a gap exists between theory and practice as the curriculum in the classroom differs from nursing students’ experiences in the clinical nursing practicum [ 5 ]. Clinical nursing training places (or practicums, as they are commonly referred to), provide students with the necessary experiences to ensure that they become proficient in the delivery of patient care [ 6 ]. The clinical practicum takes place in an environment that combines numerous structural, psychological, emotional and organizational elements that influence student learning [ 7 ] and may affect the development of professional nursing competencies, such as compassion, communication and professional identity [ 8 ]. While clinical training is a major component of nursing education curricula, stress related to clinical training is common among students [ 9 ]. Furthermore, the nursing literature indicates that the first exposure to clinical learning is one of the most stressful experiences during undergraduate studies [ 8 , 10 ]. Thus, the clinical component of nursing education is considered more stressful than the theoretical component. Students often view clinical learning, where most learning takes place, as an unsupportive environment [ 11 ]. In addition, they note strained relationships between themselves and clinical preceptors and perceive that the negative attitudes of clinical staff produce stress [ 12 ].

The effects of stress on nursing students often involve a sense of uncertainty, uneasiness, or anxiety. The literature is replete with evidence that nursing students experience a variety of stressors during their clinical practicum, beginning with the first clinical rotation. Nursing is a complex profession that requires continuous interaction with a variety of individuals in a high-stress environment. Stress during clinical learning can have multiple negative consequences, including low academic achievement, elevated levels of burnout, and diminished personal well-being [ 13 , 14 ]. In addition, both theoretical and practical research has demonstrated that increased, continual exposure to stress leads to cognitive deficits, inability to concentrate, lack of memory or recall, misinterpretation of speech, and decreased learning capacity [ 15 ]. Furthermore, stress has been identified as a cause of attrition among nursing students [ 16 ].

Most sources of stress have been categorized as academic, clinical or personal. Each person copes with stress differently [ 17 ], and utilizes deliberate, planned, and psychological efforts to manage stressful demands [ 18 ]. Coping mechanisms are commonly termed adaptation strategies or coping skills. Labrague et al. [ 19 ] noted that students used critical coping strategies to handle stress and suggested that problem solving was the most common coping or adaptation mechanism used by nursing students. Nursing students’ coping strategies affect their physical and psychological well-being and the quality of nursing care they offer. Therefore, identifying the coping strategies that students use to manage stressors is important for early intervention [ 20 ].

Studies on nursing students’ coping strategies have been conducted in various countries. For example, Israeli nursing students were found to adopt a range of coping mechanisms, including talking to friends, engaging in sports, avoiding stress and sadness/misery, and consuming alcohol [ 21 ]. Other studies have examined stress levels among medical students in the Arab region. Chaabane et al. [ 15 ], conducted a systematic review of sudies in Arab countries, including Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, Pakistan, Oman, Palestine and Bahrain, and reported that stress during clinical practicums was prevalent, although it could not be determined whether this was limited to the initial clinical course or occurred throughout clinical training. Stressors highlighted during the clinical period in the systematic review included assignments and workload during clinical practice, a feeling that the requirements of clinical practice exceeded students’ physical and emotional endurance and that their involvement in patient care was limited due to lack of experience. Furthermore, stress can have a direct effect on clinical performance, leading to mental disorders. Tung et al. [ 22 ], reported that the prevalence of depression among nursing students in Arab countries is 28%, which is almost six times greater than the rest of the world [ 22 ]. On the other hand, Saifan et al. [ 5 ], explored the theory-practice gap in the United Arab Emirates and found that clinical stressors could be decreased by preparing students better for clinical education with qualified clinical faculty and supportive preceptors.

The purpose of this study was to identify the stressors experienced by undergraduate nursing students in the United Arab Emirates during their first clinical training and the basic adaptation approaches or coping strategies they used. Recognizing or understanding different coping processes can inform the implementation of corrective measures when students experience clinical stress. The findings of this study may provide valuable information for nursing programmes, nurse educators, and clinical administrators to establish adaptive strategies to reduce stress among students going clinical practicums, particularly stressors from their first clinical training in different healthcare settings.

A qualitative approach was adopted to understand clinical stressors and coping strategies from the perspective of nurses’ lived experience. Qualitative content analysis was employed to obtain rich and detailed information from our qualitative data. Qualitative approaches seek to understand the phenomenon under study from the perspectives of individuals with lived experience [ 23 ]. Qualitative content analysis is an interpretive technique that examines the similarities and differences between and within different areas of text while focusing on the subject [ 24 ]. It is used to examine communication patterns in a repeatable and systematic way [ 25 ] and yields rich and detailed information on the topic under investigation [ 23 ]. It is a method of systematically coding and categorizing information and comprises a process of comprehending, interpreting, and conceptualizing the key meanings from qualitative data [ 26 ].

Setting and participants

This study was conducted after the clinical rotations ended in April 2022, between May and June in the nursing programme at the College of Health Sciences, University of Sharjah, in the United Arab Emirates. The study population comprised undergraduate nursing students who were undergoing their first clinical training and were recruited using purposive sampling. The inclusion criteria for this study were second-year nursing students in the first semester of clinical training who could speak English, were willing to participate in this research, and had no previous clinical work experience. The final sample consisted of 30 students.

Research instrument

The research instrument was a semi structured interview guide. The interview questions were based on an in-depth review of related literature. An intensive search included key words in Google Scholar, PubMed like the terms “nursing clinical stressors”, “nursing students”, and “coping mechanisms”. Once the questions were created, they were validated by two other faculty members who had relevant experience in mental health. A pilot test was conducted with five students and based on their feedback the following research questions, which were addressed in the study.

How would you describe your clinical experiences during your first clinical rotations?

In what ways did you find the first clinical rotation to be stressful?

What factors hindered your clinical training?

How did you cope with the stressors you encountered in clinical training?

Which strategies helped you cope with the clinical stressors you encountered?

Data collection