- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

Introduction, general overviews.

- Semiotic Analysis

- Text Mining

- Discourse Analysis

- Classical Content Analysis

- Schema Analysis

- Latent Content Analysis

- Manifest Content Analysis

- Keywords-in-context

- Constant Comparison Analysis

- Membership Categorization Analysis

- Narrative Analysis

- Conversation Analysis

- Ethnographic Decision Model Analysis

- Critical Discourse Analysis

- Frame or Framing Analysis

- Social Semiotic Analysis

- Domain Analysis

- Taxonomic Analysis

- Componential Analysis

- Theme Analysis

- Dialogical Narrative Analysis

- Qualitative Comparative Analysis

- Multimodal Discourse Analysis (MDA)

- Dimensional Analysis

- Framework Analysis

- Secondary Data Analysis

- Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA)

- Consensual Qualitative Research

- Situational Analysis

- Micro-Interlocutor Analysis

- Rhetorical Analysis

- Systematic Data Integration

- Nonverbal Communication Analysis

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Action Research in Education

- Grounded Theory

- Literature Reviews

- Mixed Methods Research

- Narrative Research in Education

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Context of Postgraduate Programs

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Gender, Power, and Politics in the Academy

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- Non-Formal & Informal Environmental Education

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques by Anthony J. Onwuegbuzie , Magdalena Denham LAST REVIEWED: 05 August 2020 LAST MODIFIED: 30 June 2014 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0078

Qualitative research can be traced back to ancient times; however, the use of qualitative methods began to be formalized in certain disciplines (e.g., sociology, anthropology) only in the 19th century. Broadly speaking, qualitative research involves an in-depth examination of human experiences and human behavior, with the goal of obtaining insights into everyday experiences and meaning attached to these experiences of individuals (via qualitative methodologies such as biography, autobiography, life history, oral history, autoethnography, case study) and groups (via qualitative methodologies such as phenomenology, ethnography, grounded theory), which, optimally, can lead to understanding the meaning of behaviors from the study participant’s/group’s perspective. Qualitative researchers tend to investigate not just what, where , and when , but more importantly the why and how of events, experiences, and behaviors. Thus, qualitative researchers are much more likely to study smaller but focused samples than large samples. In general, qualitative research studies primarily involve the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data (i.e., information) that naturally occur. Of these steps, the analysis of data arguably represents one of the most difficult steps—if not the most difficult step—of the qualitative research process because it involves a systematic exploration of meaning and the achievement of verstehen (i.e., understanding). More specifically, qualitative data analysis is a process that comprises multiple phases, and from which findings are extracted or emerge. These phases include examining, cleaning, organizing, reducing, exploring, describing, explaining, displaying, interrogating, categorizing, pattern finding, transforming, correlating, consolidating, comparing, integrating, synthesizing, and interpreting data, in ways that allow researchers to see patterns, to identify categories and themes, to develop typologies, to discover relationships, to cultivate explanations, to extract interpretations, to develop critiques, to generate or to advance theories, and/or the like, with the goal of meaning making. A criticism of qualitative data analysis is that because it typically involves examination of data extracted from small, nonrandom samples, findings stemming from any qualitative analysis usually are not generalizable beyond the local research participants. However, what is a limitation for one purpose (i.e., generalization of findings to the population the sample was drawn from), is a strength for another purpose. Specifically, the examination of relatively small samples allows qualitative researchers to collect (maximally) rich data (e.g., via in-depth interviews, focus groups, observations, images, nonverbal communication). This, in turn, makes it more likely that as a result of the qualitative data analysis, verstehen will be achieved.

The analysis of data represents the most important and difficult step in the qualitative research process. Therefore, the purpose of this entry is to document the history and development of qualitative analytical approaches. In particular, described here are thirty-four formal qualitative data-analysis approaches that were identified from an exhaustive search of the literature. This OBO entry not only extends the work of Onwuegbuzie, et al. 2011 —which identified twenty-three analysis approaches—but by adding numerous other qualitative data analysis approaches, it also extends these works by documenting the origin of each analysis approach, mapping it onto the nine moments described in Denzin and Lincoln 2011 and outlining the sources of qualitative data that it can analyze. With respect to the latter, see Leech and Onwuegbuzie 2008 with typology wherein the following four major sources of qualitative data prevail: talk, observations, images, and documents. Specifically, talk represents data that are extracted directly from the voices of the participants using data collection techniques such as individual interviews and focus groups. Observations involve the collection of data by systematically watching or perceiving one or more events, interactions, or nonverbal communication to address or to inform the research question(s). Images represent still (e.g., drawings, photographs) or moving (e.g., videos) visual data that are observed or perceived. Documents represent the collection of text that exists either in printed or digital form. As Miles and Huberman 1994 declared: “The strengths of qualitative data rest on the competence with which their analysis is carried out” (p. 10). By only being aware of a few qualitative data-analysis approaches, a qualitative researcher might make the data fit the analysis rather than select the most appropriate data-analysis approach given the underlying research elements such as the research question, researcher’s lens, and sampling and design characteristics. In contrast, by being aware of the array of qualitative data-analysis approaches, as well as how and when to conduct them, a qualitative researcher is in a better position not only to conduct analyses that have integrity but also to conduct analyses that emerge as findings emerge. Thus, qualitative researchers likely would put themselves in a better position for making meaning if they adopt a constructivist approach to qualitative data analysis. However, this can only occur if they have an awareness of multiple ways of analyzing qualitative data. This goal helps to establish the significance of the current work in this field.

Denzin, Norman K., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. 2011. Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In Sage handbook of qualitative research . 4th ed. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, 1–25. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

The authors document the history of qualitative research. This history spans nine moments, starting with they call the “traditional” moment and continuing through to the ninth moment, which they call the “fractured future,” which is the present moment.

Leech, Nancy L., and Anthony J. Onwuegbuzie. 2008. Qualitative data analysis: A compendium of techniques and a framework for selection for school psychology research and beyond. School Psychology Quarterly 23:587–604.

DOI: 10.1037/1045-3830.23.4.587

The authors describe the following eighteen qualitative analysis techniques: method of constant comparison analysis, keywords-in-context, word count, classical content analysis, domain analysis, taxonomic analysis, componential analysis, conversation analysis, discourse analysis, secondary analysis, membership categorization analysis, narrative analysis, qualitative comparative analysis, semiotics, manifest content analysis, latent content analysis, text mining, and micro-interlocutor analysis.

Miles, Matthew B., and A. Michael Huberman. 1994. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook . 2d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

In this groundbreaking book, the authors conceptualize and describe nineteen within-case analyses (i.e., partially ordered display, time-ordered display, role-ordered display, and conceptually ordered display) and eighteen cross-case analyses (i.e., partially ordered display, case-ordered display, time-ordered display, and conceptually ordered display. Thus, this work is the most comprehensive guidebook to qualitative analysis to date.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J., Nancy L. Leech, and Kathleen M. T. Collins. 2011. Toward a new era for conducting mixed analyses: The role of quantitative dominant and qualitative dominant crossover mixed analyses. In The Sage handbook of innovation in social research methods . Edited by Malcolm Williams and Paul W. Vogt, 353–384. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

In this book chapter, the authors introduce a unified framework for combining qualitative analysis and quantitative analysis—which they call a mixed analysis—regardless of whether the researcher is oriented toward quantitative research or mixed research.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Research

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Learning Strategies

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Native American Studies

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Politics of Education

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Program Evaluation

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Response to Intervention

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Science Education

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-sex Education

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Science and Education Research

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development

- Teacher Unions and Associations

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Technologies, Teaching, and Learning in Higher Education

- Technology Education in Early Childhood

- Technology, Educational

- Technology-based Assessment

- The Bologna Process

- The Regulation of Standards in Higher Education

- Theories of Educational Leadership

- Three Conceptions of Literacy: Media, Narrative, and Gamin...

- Tracking and Detracking

- Traditions of Quality Improvement in Education

- Transformative Learning

- Transitions in Early Childhood Education

- Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities in the Unite...

- Understanding the Psycho-Social Dimensions of Schools and ...

- University Faculty Roles and Responsibilities in the Unite...

- Using Ethnography in Educational Research

- Value of Higher Education for Students and Other Stakehold...

- Virtual Learning Environments

- Vocational and Technical Education

- Wellness and Well-Being in Education

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Young Children and Spirituality

- Young Children's Learning Dispositions

- Young Children's Working Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|195.158.225.230]

- 195.158.225.230

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

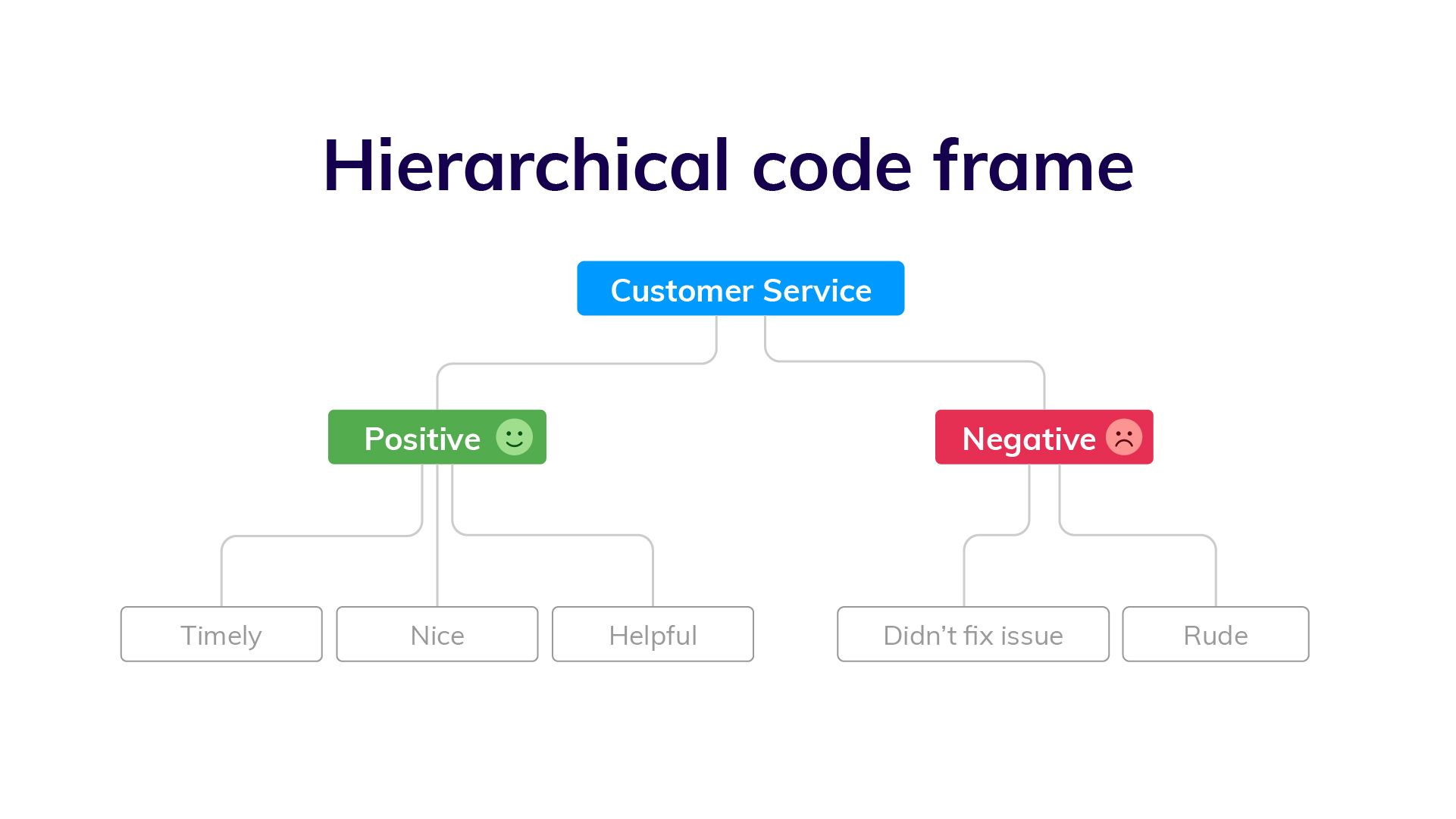

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

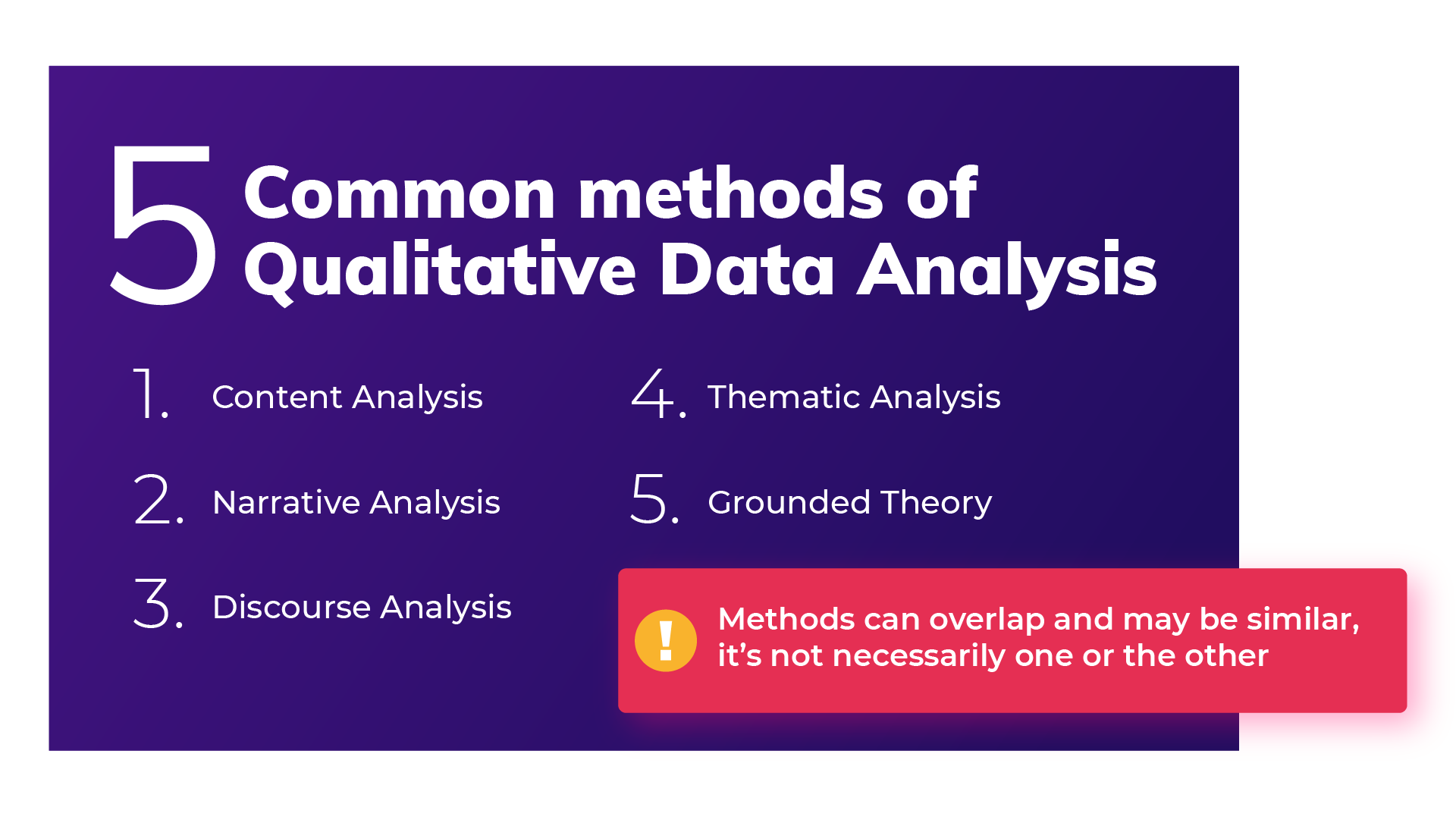

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 13, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Using Qualitative Data in Education For Better Student Outcomes

Qualitative data in education is a powerful tool that can be used to enhance instructional practices and improve student outcomes. By understanding and effectively utilizing qualitative data, educators can gain valuable insights into their students’ experiences, perceptions, and needs.

In this article, we’ll uncover the importance of qualitative data in education, discuss different techniques for gathering and analyzing data, and provide strategies for applying this knowledge to make data-informed decisions to benefit students.

- What is Qualitative Data in Education?

- The Importance of Qualitative Data in Education

- Gathering Qualitative Data in the Classroom

- Analyzing Qualitative Data for Educational Insights

- Tools for Qualitative Data Analysis

- Applying Qualitative Data to Improve Student Outcomes

- Overcoming Challenges in Using Qualitative Data

1. What is Qualitative Data in Education?

When it comes to understanding qualitative data in education, it’s important to have a clear definition. Qualitative data encompasses a wide range of information that is gathered through various methods, including observations, interviews, focus groups, and written documents. These methods include observing students in their natural learning environments, conducting interviews to gather their perspectives, engaging in focus groups to explore shared experiences, and analyzing written documents such as essays or reflective journals.

By using these methods, educators can gather rich and detailed information about students’ experiences, allowing them to gain insights into their thoughts, emotions, and motivations. This type of data is often subjective in nature, as it is influenced by the unique perspectives and interpretations of the individuals involved.

2. The Importance of Qualitative Data in Education

Qualitative data plays a crucial role in education as it provides insights into complex phenomena that quantitative data alone cannot capture. While quantitative data can provide information about student performance and achievement, it does not provide a complete picture of the factors that influence these outcomes.

Read next: A guide to the different types of data in education

By gathering qualitative data, teachers can gain a holistic understanding of their students’ learning environments. They can uncover factors that may influence their academic performance, such as classroom dynamics, instructional approaches, and socio-cultural factors. For example, qualitative data can reveal how students’ cultural backgrounds impact their learning experiences and how their interactions with peers and teachers shape their attitudes towards education.

Moreover, qualitative data allows educators to explore the why and how behind students’ behaviors, attitudes, and outcomes. It enables them to identify patterns, themes, and trends that can guide instructional practices, curriculum development, and overall school improvement strategies.

By analyzing qualitative data, educators can gain valuable insights into the effectiveness of their teaching methods and make informed decisions to enhance student learning. They can also use this data to tailor their instruction to meet the diverse needs of their students, ensuring that every learner has the opportunity to succeed.

3. Gathering Qualitative Data in the Classroom

Gathering qualitative data in the classroom involves using various methods to collect and document students’ experiences and perspectives. By employing a range of techniques, educators can gather a rich and diverse set of qualitative data that represents various dimensions of students’ educational journey.

Qualitative data in education can take different forms, including:

- Written reflections

- Classroom observations

- Focus groups, and

- Student work samples.

Each type of data collection method offers unique insights into students’ thoughts, feelings, and attitudes. For example, interviews can provide in-depth information about individual students’ experiences and perceptions. Educators can sit down with students one-on-one and ask open-ended questions to delve into their thoughts and emotions regarding their learning experiences. This method allows for a deeper understanding of the student’s perspective and allows them to express their thoughts freely.

Focus groups, on the other hand, allow for group discussions and the exploration of shared perspectives and experiences. Educators can gather a small group of students and facilitate a conversation around a specific topic or theme. This method encourages students to share their thoughts and engage in meaningful dialogue with their peers, providing valuable insights into their collective experiences.

By employing these techniques, educators can engage students directly in the data collection process, offering them the opportunity to have their voices heard. This participatory approach not only promotes student engagement but also provides a more accurate representation of their experiences and perspectives.

4. Analyzing Qualitative Data for Educational Insights

Once qualitative data has been collected, the next step is to analyze it to derive meaningful insights. Analyzing qualitative data involves a systematic and rigorous examination of the gathered information to identify patterns, themes, and trends.

Qualitative data analysis is a crucial step in the research process, as it allows educators to gain a deeper understanding of the experiences, perspectives, and behaviors of their students. By analyzing qualitative data, educators can uncover valuable insights that can inform their teaching practices and decision-making processes.

The process of qualitative data analysis typically involves several key steps. These include transcribing interviews or observations, identifying codes or themes, categorizing data, and interpreting the findings.

Transcribing interviews or observations is an essential step in qualitative data analysis. It involves converting audio or video recordings into written text, ensuring that every detail and nuance is captured accurately. This transcription process allows educators to review and analyze the data more effectively.

Identifying codes or themes is another crucial aspect of qualitative data analysis. Codes are labels or tags that are assigned to specific segments of data, representing concepts or ideas that emerge from the analysis. By identifying codes, educators can organize the data and make it more manageable for further analysis.

Categorizing data is the process of grouping similar codes or themes together. This step helps educators identify patterns and connections within the data. By categorizing data, educators can gain a holistic view of the information and draw meaningful conclusions.

Interpreting the findings is the final step in qualitative data analysis. It involves making sense of the data and extracting meaningful insights. Educators need to critically analyze the data, considering the context, participants’ perspectives, and their own experiences and knowledge. By interpreting the findings, educators can generate valuable knowledge that can be applied to their teaching practices.

5. Tools for Qualitative Data Analysis

There are various software tools available that can facilitate the analysis of qualitative data. These tools provide features for coding, organizing, and visualizing data, making the analysis process more efficient and manageable.

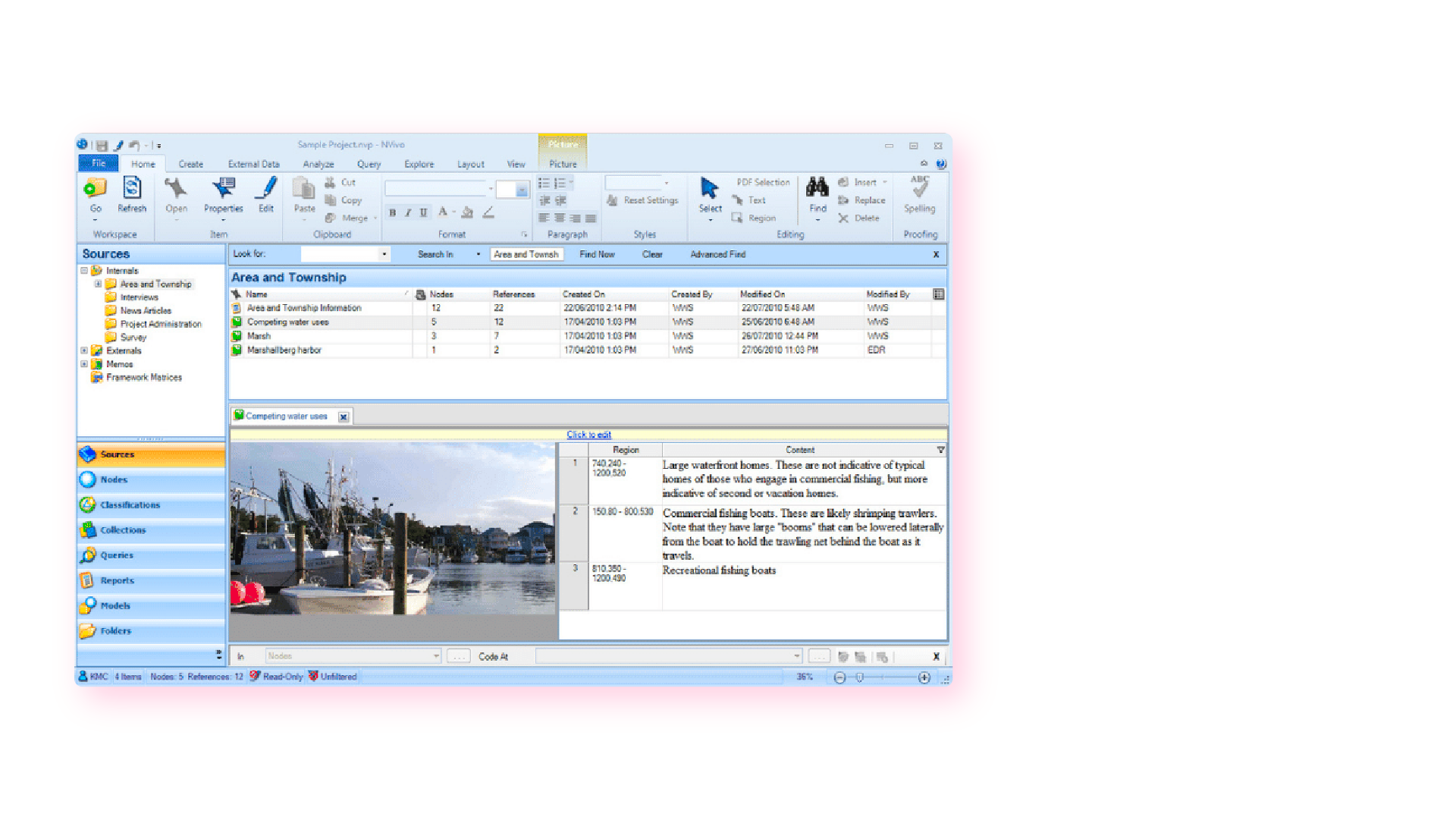

One popular qualitative data analysis software is NVivo. NVivo offers a range of features that allow educators to organize and analyze their qualitative data effectively. It provides tools for coding, annotating, and visualizing data, making it easier to identify patterns and themes. NVivo also allows for collaboration, enabling educators to work together on analyzing the data and deriving insights.

Another widely used software for qualitative data analysis is ATLAS.ti. ATLAS.ti provides a comprehensive set of tools for coding, organizing, and analyzing qualitative data. It allows educators to create networks and visual representations of their data, helping them to identify relationships and connections. ATLAS.ti also offers advanced text search capabilities, making it easier to locate specific information within the data.

Overall, the availability of these software tools has revolutionized the process of qualitative data analysis. Educators now have access to powerful and user-friendly tools that can enhance their ability to analyze and derive insights from qualitative data. By utilizing these tools, educators can make more informed decisions and improve their teaching practices based on a deeper understanding of their students’ experiences and perspectives.

6. Applying Qualitative Data to Improve Student Outcomes

Using qualitative data effectively can lead to tangible improvements in student outcomes. By applying insights gained from qualitative data analysis, educators can tailor their instructional practices and interventions to better support students’ needs.

Strategies for Data-Informed Decision Making

Data-informed decision making involves using qualitative data as a basis for making informed choices about teaching strategies, curriculum development, and student support services. Educators can use qualitative data to identify areas for improvement, monitor student progress, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions or instructional approaches.

For example, qualitative data might highlight areas where students are experiencing difficulties or disengagement. Based on this information, educators can implement targeted interventions or adapt teaching methods to better meet students’ needs.

Read next: How student data can improve your teaching strategy

Monitoring and Evaluating the Impact of Data-Driven Changes

Once changes have been implemented based on qualitative data findings, it is essential to monitor and evaluate their impact. Ongoing assessment ensures that interventions are effective and responsive to students’ needs.

Regularly reviewing the outcomes of data-driven changes allows educators to gather additional qualitative data to inform and refine their practices. This cyclical process of data collection, analysis, implementation, and evaluation enables continuous improvement and better student outcomes.

7. Overcoming Challenges in Using Qualitative Data

While qualitative data can provide valuable insights, there are challenges to consider when collecting and analyzing this type of data in education. By addressing these obstacles, educators can maximize the benefits of using qualitative data.

One common challenge is ensuring data reliability and validity. To address this, educators should use established research methodologies, such as triangulation, where multiple methods and data sources are used to support or validate findings. Additionally, educators may face time constraints and limited resources when collecting qualitative data. Planning and prioritizing data collection activities, as well as leveraging technology tools for data analysis, can help overcome these challenges.

When working with qualitative data, it is essential to prioritize ethical considerations. Educators must obtain informed consent from participants, protect their privacy and confidentiality , and ensure that the data is used only for educational purposes. By nurturing a culture of ethical data use, educators can build trust with their students and maintain the integrity of their research and decision-making processes.

Final Thoughts

In summary, qualitative data in education is a valuable resource that can enhance and improve student outcomes. Understanding qualitative data, employing effective data collection techniques, and analyzing the gathered information can provide educators with insights into students’ experiences and needs.

While qualitative data provides rich, in-depth insights into student experiences and needs, it’s essential to visualize and interpret this information for maximum impact. Our Inno™ Starter Kits are designed precisely for this purpose. By offering educators a comprehensive platform to easily plug in and showcase qualitative student data, the kits empower you to derive actionable strategies for enhanced student outcomes. Don’t just gather data—transform it into meaningful change with Inno™ Starter Kits.

Thank you for sharing!

You may also be interested in

Why interactive data visualization is the key to better student outcomes.

Discover the power of interactive data visualization for student data with this in-depth guide.

by Innovare | Dec 4, 2023 | Data in K-12 Schools

Data in K-12 Schools

What is Data in Education? The Ultimate Guide

Discover the power of data in education with our comprehensive guide.

by Innovare | Sep 18, 2023 | Data in K-12 Schools

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. See our Privacy Policy to learn more. Accept

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Surveys Academic

Examples of Qualitative Data in Education: How to Use

The phrase “Examples of Qualitative Data in Education” reveals rich and detailed knowledge in the field of education, where understanding fuels creativity and insights drive advancement. While quantitative data frequently grabs the spotlight, its qualitative counterpart is just as important for understanding how complicated learning environments work.

In this blog, we will delve into the significance of qualitative data in education and provide a range of examples showcasing its applications in fostering educational excellence.

What is qualitative data?

Qualitative data is a type of data that is open to interpretation and can be used in a variety of ways- both as a measure of quality and as the basis for analysis.

It describes the way things are and tells you why something is happening, rather than what is happening (for example, if a student isn’t doing well in math, qualitative data would tell you their reasons for this), rather than describing its characteristics or how much of it there is.

Qualitative data is not numerical and does not have a set meaning, which makes it difficult to analyze. Understanding how to use qualitative data collection in education effectively can be crucial for educational institutions.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Interview

Using qualitative data in educational settings

Qualitative data provides insight into the learning experience that cannot always be expressed through numbers. It allows you to better understand how students learn by asking open-ended questions and listening carefully to their answers.

When you use qualitative data, you can investigate particular areas of concern for your organization and formulate action plans as needed. Also, qualitative data addresses a number of the shortcomings of quantitative research.

For instance, quantitative data can indicate that a particular school district’s test scores have outperformed those of other regional school districts but cannot explain why this is the case.

Examples of qualitative data in education

Here are some examples of qualitative data in education:

Field observations

Teachers and administrators could observe the classroom during different times of day, at different points during the year, or when a special event is happening.

Documentary research

School organizations can spend time looking closely at their current documents to learn more about students.

Focus groups

Conducting focus group discussions with students, teachers, or parents can provide qualitative insights into their perceptions, experiences, and opinions related to educational practices and policies.

Student portfolios

Reviewing student portfolios that showcase their work, assignments, and projects over time offers qualitative data on their progress, growth, and learning journey.

Peer review and feedback

Encouraging students to provide peer reviews and feedback on each other’s work generates qualitative data on their ability to critically assess and provide constructive input.

Learning diaries

Similar to journals, learning diaries encourage students to document their daily experiences, challenges, and triumphs, offering qualitative insights into their engagement and progress.

Parent-teacher conferences

Conversations during parent-teacher conferences provide qualitative data about a student’s strengths, weaknesses, and overall development from both home and school perspectives.

Online discussion forums

Analyzing interactions on online platforms where students and educators discuss topics related to coursework offers qualitative insights into their understanding, questions, and collaboration and is one of the best examples of qualitative data in education.

Classroom artifacts

Examining classroom artifacts like bulletin boards, student artwork, and project displays provides qualitative data on the learning environment, student creativity, and the integration of various subjects.

Audio and video recordings

Recording classroom discussions, presentations, or group activities captures qualitative data on communication skills, collaboration, and the depth of student understanding.

Student surveys with open-ended questions

Incorporating open-ended questions into student surveys enables them to express their thoughts, opinions, and suggestions in their own words, yielding qualitative data that complements quantitative results.

Teacher reflective journals

Teachers maintaining reflective journals about their teaching experiences, challenges, and innovative approaches generate qualitative data on professional growth and instructional strategies.

Student interviews

One-on-one interviews with students are one of the most common examples of qualitative data in education. It can provide qualitative insights into their learning experiences, interests, and motivations, helping educators tailor instruction to individual needs.

How can a survey tool help with qualitative data analysis in education?

A survey tool is a useful research tool that can help with qualitative data analysis in education. Qualitative data is best analyzed through close inspection and asking questions to understand the root causes of phenomena, but this is a time-consuming process.

A well-designed survey questionnaire can simplify the qualitative analysis by giving you insight into what most concerns your group and helping you to prioritize your responses.

Key steps to using a survey tool: In order to successfully use a survey tool, you’ll need to:

Define your goal

What are you trying to accomplish? If you don’t know where you want the findings of your Qualitative research project to lead, it will be difficult for people to provide feedback and difficult for you to analyze the results.

Choose your qualitative research method

What are your options? How will people be invited to give feedback, and where will this feedback come from? Identifying how participants/respondents/users will be asked about their experiences is an important first step.

Design survey questions

Craft thoughtful and relevant survey questions that align with your research goals. Ensure a mix of closed-ended questions to gather quantitative data and open-ended questions to gather qualitative insights.

Use clear and concise language to avoid ambiguity, and consider using skip logic or branching to tailor the survey experience based on participants’ responses. Well-designed questions will make the data analysis process smoother.

Distribute and collect responses

Utilize the survey tool to distribute the survey to your target audience, whether it’s students, teachers, parents, or administrators. You can use various distribution channels such as email, social media, or school websites.

Track the responses as they come in and monitor the data collection process. Keep the survey open for an appropriate amount of time to ensure a diverse range of responses.

Analyze qualitative data

Once you’ve collected a sufficient number of responses, begin the qualitative data analysis process. Start by categorizing and coding open-ended responses. Look for recurring themes, patterns, and trends within the qualitative data.

You can use tools like thematic analysis to identify key themes that emerge from participants’ responses. Software like NVivo or even Excel can help organize and analyze qualitative data effectively.

Triangulate with quantitative data

If your survey included closed-ended questions with quantitative responses (e.g., Likert scales), you can enrich your analysis by comparing qualitative insights with quantitative data. This triangulation can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research topic.

For example, if participants express negative sentiments about a particular aspect of education, you can cross-reference this sentiment with the corresponding quantitative rating to see if there’s a correlation.

LEARN ABOUT: Steps in Qualitative Research

Methods to analyze qualitative data

Qualitative research methods form the cornerstone of understanding human experiences, utilizing an array of data collection methods to delve into the nuances of perspectives. From interviews and focus groups to ethnographic studies and content analysis, these qualitative methods harmonize to reveal the intricate tapestry of human narratives.

Now, we will unveil how these methods converge, creating a symphony of insights that deepen our comprehension of the human condition.

Content analysis

The content of the data is analyzed by scrutinizing and interpreting texts, pictures, video, audio, and other materials. This involves looking at the words in a document, for example, and deciding their meaning.

Grounded theory

To create a grounded theory, you study what is happening in a particular situation and try to formulate a theory about why it happens. This process often begins with an initial assumption or question, which will be tested out over time. For example: “How do we know when this analysis process is finished?”

Phenomenology

Phenomenology looks at experiences from the perspective of those who experience them. It tries to understand what these experiences mean to people rather than the events themselves. This is relevant for understanding students’ learning experiences in an educational setting.

Framework analysis

Framework analysis is a conversation with participants and then using the content of that discussion to analyze the data. It could involve asking individuals, “What was the knowledge you gained from this project?” and then anonymizing their answers in order to avoid starting your article with personal stories.

Discourse analysis

Discourse analysis looks at how individuals use language and what the implications of those uses are. This can be helpful in a classroom setting where students use their voices to express themselves about their learning process within the walls of academia.

Interpretative phenomenological analysis

Interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) helps you understand that qualitative data is a type of open-ended and interpretable data that can be used in various ways. Whether you’re trying to learn more about your customer’s experiences or the educational process, qualitative analysis will help get insights into what’s important for your project.

Learn more about academic surveys here

Learn more about academic research services for students here

Qualitative data in education is a treasure trove of insights that empowers educators and administrators to create holistic learning experiences.

By leveraging methods such as interviews, observations, and reflections, educational institutions can gain a deeper understanding of student needs, teaching strategies, and program effectiveness. The fusion of quantitative and qualitative data enriches decision-making processes and paves the way for continuous improvement in education.

If you want help analyzing the qualitative aspects of your research projects, we’re here to provide assistance with our survey tool ! Let us know if there are any other information needs, and we’ll work on providing an answer as soon as possible.

FREE TRIAL LEARN MORE

MORE LIKE THIS

Top 13 A/B Testing Software for Optimizing Your Website

Apr 12, 2024

21 Best Contact Center Experience Software in 2024

Government Customer Experience: Impact on Government Service

Apr 11, 2024

Employee Engagement App: Top 11 For Workforce Improvement

Apr 10, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Korean J Med Educ

- v.29(2); 2017 Jun

The qualitative orientation in medical education research

Qualitative research is very important in educational research as it addresses the “how” and “why” research questions and enables deeper understanding of experiences, phenomena and context. Qualitative research allows you to ask questions that cannot be easily put into numbers to understand human experience. Getting at the everyday realities of some social phenomenon and studying important questions as they are really practiced helps extend knowledge and understanding. To do so, you need to understand the philosophical stance of qualitative research and work from this to develop the research question, study design, data collection methods and data analysis. In this article, I provide an overview of the assumptions underlying qualitative research and the role of the researcher in the qualitative process. I then go on to discuss the type of research objectives which are common in qualitative research, then introduce the main qualitative designs, data collection tools, and finally the basics of qualitative analysis. I introduce the criteria by which you can judge the quality of qualitative research. Many classic references are cited in this article, and I urge you to seek out some of these further reading to inform your qualitative research program.

Introduction

When we speak of “quantitative” or “qualitative” methodologies, we are in the final analysis speaking about an interrelated set of assumptions about the social world which are philosophical, ideological, and epistemological. They encompass more than just data collection methodologies [ 1 ].

It is easy to assume that the differences between quantitative and qualitative research are solely about how data is collected—the randomized controlled trial versus ethnographic fieldwork, the cohort study versus the semi-structured interview. However, quantitative and qualitative approaches make different assumptions about the world [ 2 ], about how science should be conducted, and about what constitutes legitimate problems, solutions and criteria of “proof” [ 3 ].

Why is it important to understand differences in assumptions, or philosophies, of research? Why not just go ahead and do a survey or carry out some interviews? First, the assumptions behind the research tools you choose provide guidance for conducting your research. They indicate whether you should be an objective observer or whether you have a contributory role in the research process. They guide whether or not you must slavishly ask each person in a study the same questions or whether your questions can evolve as the study progresses. Second, you may wish to submit your work as a dissertation or as a research paper to be considered for publication in a journal. If so, the chances are that examiners, editors, and reviewers might have knowledge of different research philosophies from yours and may be unwilling to accept the legitimacy of your approach unless you can make its assumptions clear. Third, each research paradigm has its own norms and standards, its accepted ways of doing things. You need to “do things right”. Finally, understanding the theoretical assumptions of the research approach helps you recognize what the data collection and analysis methods you are working with do well and what they do less well, and lets you design your research to take full advantage of their strengths and compensate for their weaknesses.

In this short article, I will introduce the assumptions of qualitative research and their implications for research questions, study design, methods and tools, and analysis and interpretation. Readers who wish a comparison between qualitative and quantitative approaches may find Cleland [ 4 ] useful.

Ontology and epistemology

We start with a consideration of the ontology (assumptions about the nature of reality) and epistemology (assumptions about the nature of knowledge) of qualitative research.

Qualitative research approaches are used to understand everyday human experience in all its complexity and in all its natural settings [ 5 ]. To do this, qualitative research conforms to notions that reality is socially constructed and that inquiry is unavoidably value-laden [ 6 ]. The first of these, reality is socially constructed, means reality cannot be measured directly—it exists as perceived by people and by the observer. In other words, reality is relative and multiple, perceived through socially constructed and subjective interpretations [ 7 ]. For example, what I see as an exciting event may be seen as a threat by other people. What is considered a cultural ritual in my country may be thought of as quite bizarre elsewhere. Qualitative research is concerned with how the social world is interpreted, understood, experienced, or constructed. Mann and MacLeod [ 8 ] provide a very good overview of social constructivism which is a excellent starting point for understanding this.

The idea of people seeing things in diverse ways also holds true in research process, hence inquiry being valued-laden. Different people have different views of the same thing depending on their upbringing and other experiences, their training, and professional background. Someone who has been trained as a social scientist may “see” things differently from someone who has been medically trained. A woman may see things differently to a man. A more experienced researcher will see things differently from a novice. A qualitative researcher will have very different views of the nature of “evidence” than a quantitative researcher. All these viewpoints are valid. Moreover, different researchers can study the same topic and try to find solutions to the same challenges using different study designs—and hence come up with different interpretations and different recommendations. For example, if your position is that learning is about individual, cognitive, and acquisitive processes, then you are likely to research the use of simulation training in surgery in terms of the effectiveness and efficacy of training related to mastery of technical skills [ 9 , 10 ]. However, if your stance is that learning is inherently a social activity, one which involves interactions between people or groups of people, then you will look to see how the relationships between faculty members, participants and activities during a simulation, and the wider social and cultural context, influence learning [ 11 , 12 ].

Whether researchers are explicit about it or not, ontological and epistemological assumptions will underpin how they study aspects of teaching and learning. Differences in these assumptions shape not only study design, but also what emerges as data, how this data can be analysed and even the conclusions that can be drawn and recommendations that can be made from the study. This is referred to as worldview, defined by Creswell [ 13 ] as “a general orientation about the world and the nature of research that a researcher holds.” McMillan [ 14 ] gives a very good explanation of the importance of this phenomenon in relation to medical education research. There is increasing expectation that researchers make their worldview explicit in research papers.

The research objective

Given the underlying premise that reality is socially constructed, qualitative research focuses on answering “how” and “why” questions, of understanding a phenomena or a context. For example, “Our study aimed to answer the research question: why do assessors fail to report underperformance in medical students? [ 15 ]”, “The aim of this work was to investigate how widening participation policy is translated and interpreted for implementation at the level of the individual medical school [ 4 ].”

Common verbs in qualitative research questions are identify, explore, describe, understand, and explain. If your research question includes words like test or measure or compare in your objectives, these are more appropriate for quantitative methods, as they are better suited to these types of aims. Bezuidenhout and van Schalkwyk [ 16 ] provide a good guide to developing and refining your research question. Lingard [ 17 ]’s notion of joining the conversation and the problem-gap-hook heuristic are also very useful in terms of thinking about your question and setting it out in the introduction to a paper in such a way as to interest journal editors and readers.

Do not think formulating a research question is easy. Maxwell [ 18 ] gives a good overview of some of the potential issues including being too general, making assumptions about the nature of the issue/problem and using questions which focus the study on difference rather than process. Developing relevant, focused, answerable research questions takes time and generating good questions requires that you pay attention not just to the questions themselves but to their connections with all the other components of the study (the conceptual lens/theory, the methods) [ 18 ].

Theory can be applied to qualitative studies at different times during the research process, from the selection of the research phenomenon to the write-up of the results. The application of theory at different points can be described as follows [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]: (1) Theory frames the study questions, develops the philosophical underpinnings of the study, and makes assumptions to justify or rationalize the methodological approach. (2) Qualitative investigations relate the target phenomenon to the theory. (3) Theory provides a comparative context or framework for data analysis and interpretation. (4) Theory provides triangulation of study findings.

Schwartz-Barcott et al. [ 20 ] characterized those processes as theoretical selectivity (the linking of selected concepts with existing theories), theoretical integration (the incorporation and testing of selected concepts within a particular theoretical perspective), and theory creation (the generation of relational statements and the development of a new theory). Thus, theory can be the outcome of the research project as well as the starting point [ 22 ].

However, the emerging qualitative researcher may wish a little more direction on how to use theory in practice. I direct you to two papers: Reeves et al. [ 23 ] and Bordage [ 24 ]. These authors clearly explain the utility of theory, or conceptual frameworks, in qualitative research, how theory can give researchers different “lenses” through which to look at complicated problems and social issues, focusing their attention on different aspects of the data and providing a framework within which to conduct their analysis. Bordage [ 24 ] states that “conceptual frameworks represent ways of thinking about a problem or a study, or ways of representing how complex things work the way they do. Different frameworks will emphasise different variables and outcomes.” He presents an example in his paper and illustrates how different lens highlight or emphasise different aspects of the data. Other authors suggest that two theories are potentially better than one in exploring complex social issues [ 25 ]. There is an example of this in one of my papers, where we used the theories of Bourdieu [ 26 ] and Engestrom [ 27 , 28 ] nested within an overarching framework of complexity theory [ 29 ] to help us understand learning at a surgical bootcamp. However, I suggest that for focused studies and emerging educational researchers, one theoretical framework or lens is probably sufficient.

So how to identify an appropriate theory, and when to use it? It is crucially important to read widely, to explore lots of theories, from disciplines such as (but not only) education, psychology, sociology, and economics, to see what theory is available and what may be suitable for your study. Carefully consider any theory, check its assumptions [ 30 ] are congruent with your approach, question, and context before final selection [ 31 ] before deciding which theory to use. The time you spend exploring theory will be time well spent in terms not just of interpreting a specific data set but also to broadening your knowledge. The second question, when to use it, depends on the nature of the study, but generally the use of theory in qualitative research tends to be inductive; that is, building explanations from the ground up, based on what is discovered. This typically means that theory is brought in at the analysis stage, as a lens to interpret data.

In the qualitative approach, the activities of collecting and analyzing data, developing and modifying theory, and elaborating or refocusing the research questions, are usually going on more or less simultaneously, each influencing all of the others for a useful model of qualitative research design [ 18 ]. The researcher may need to reconsider or modify any design decision during the study in response to new developments. In this way, qualitative research design is less linear than quantitative research, which is much more step-wise and fixed.

This is not the same as no structure or plan. Most qualitative projects are pre-structured at least in terms of the equivalent of a research protocol, setting out what you are doing (aims and objectives), why (why is this important), and how (theoretical underpinning, design, methods, and analysis). I have provided a brief overview of common approaches to qualitative research design below and direct you to the numerous excellent textbooks which go into this in more detail [ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ].

There are five basic categories of qualitative research design: ethnography, narrative, phenomenological, grounded theory, and case study [ 13 , 32 ].

2. Ethnography

In ethnography, you immerse yourself in the target participants’ environment to understand the goals, cultures, challenges, motivations, and themes that emerge. Ethnography has its roots in cultural anthropology where researchers immerse themselves within a culture, often for years. Through multiple data collection approaches—observations, interviews and documentary data, ethnographic research offers a qualitative approach with the potential to yield detailed and comprehensive accounts of different social phenomenon (actions, behavior, interactions, and beliefs). Rather than relying on interviews or surveys, you experience the environment first hand, and sometimes as a “participant observer” which gives opportunity to gather empirical insights into social practices which are normally “hidden” from the public gaze. Reeves et al. [ 36 ] give an excellent guide to ethnography in medical education which is essential reading if you are interested in using this approach.

3. Narrative

The narrative approach weaves together a sequence of events, usually from just one or two individuals to form a cohesive story. You conduct in-depth interviews, read documents, and look for themes; in other words, how does an individual story illustrate the larger life influences that created it. Often interviews are conducted over weeks, months, or even years, but the final narrative does not need to be in chronological order. Rather it can be presented as a story (or narrative) with themes, and can reconcile conflicting stories and highlight tensions and challenges which can be opportunities for innovation.

4. Phenomenology

Phenomenology is concerned with the study of experience from the perspective of the individual, “bracketing” taken-for-granted assumptions and usual ways of perceiving. Phenomenological approaches emphasise the importance of personal perspective and interpretation. As such they are powerful for understanding subjective experience, gaining insights into people’s motivations and actions, and cutting through the clutter of taken-for-granted assumptions and conventional wisdom.

Phenomenological approaches can be applied to single cases or to selected samples. A variety of methods can be used in phenomenologically-based research, including interviews, conversations, participant observation, action research, focus meetings, and analysis of personal texts. Beware though—phenomenological research generates a large quantity data for analysis.

The phenomenological approach is used in medical education research and there are some good articles which will familiarise you with this approach [ 37 , 38 ].

5. Grounded theory

Whereas a phenomenological study looks to describe the essence of an activity or event, grounded theory looks to provide an explanation or theory behind the events. Its main thrust is to generate theories regarding social phenomena: that is, to develop higher level understanding that is “grounded” in, or derived from, a systematic analysis of data [ 39 ]. Grounded theory is appropriate when the study of social interactions or experiences aims to explain a process, not to test or verify an existing theory. Rather, the theory emerges through a close and careful analysis of the data.