Best Nursing Research Topics for Students

What is a nursing research paper.

- What They Include

- Choosing a Topic

- Best Nursing Research Topics

- Research Paper Writing Tips

Writing a research paper is a massive task that involves careful organization, critical analysis, and a lot of time. Some nursing students are natural writers, while others struggle to select a nursing research topic, let alone write about it.

If you're a nursing student who dreads writing research papers, this article may help ease your anxiety. We'll cover everything you need to know about writing nursing school research papers and the top topics for nursing research.

Continue reading to make your paper-writing jitters a thing of the past.

A nursing research paper is a work of academic writing composed by a nurse or nursing student. The paper may present information on a specific topic or answer a question.

During LPN/LVN and RN programs, most papers you write focus on learning to use research databases, evaluate appropriate resources, and format your writing with APA style. You'll then synthesize your research information to answer a question or analyze a topic.

BSN , MSN , Ph.D., and DNP programs also write nursing research papers. Students in these programs may also participate in conducting original research studies.

Writing papers during your academic program improves and develops many skills, including the ability to:

- Select nursing topics for research

- Conduct effective research

- Analyze published academic literature

- Format and cite sources

- Synthesize data

- Organize and articulate findings

About Nursing Research Papers

When do nursing students write research papers.

You may need to write a research paper for any of the nursing courses you take. Research papers help develop critical thinking and communication skills. They allow you to learn how to conduct research and critically review publications.

That said, not every class will require in-depth, 10-20-page papers. The more advanced your degree path, the more you can expect to write and conduct research. If you're in an associate or bachelor's program, you'll probably write a few papers each semester or term.

Do Nursing Students Conduct Original Research?

Most of the time, you won't be designing, conducting, and evaluating new research. Instead, your projects will focus on learning the research process and the scientific method. You'll achieve these objectives by evaluating existing nursing literature and sources and defending a thesis.

However, many nursing faculty members do conduct original research. So, you may get opportunities to participate in, and publish, research articles.

Example Research Project Scenario:

In your maternal child nursing class, the professor assigns the class a research paper regarding developmentally appropriate nursing interventions for the pediatric population. While that may sound specific, you have almost endless opportunities to narrow down the focus of your writing.

You could choose pain intervention measures in toddlers. Conversely, you can research the effects of prolonged hospitalization on adolescents' social-emotional development.

What Does a Nursing Research Paper Include?

Your professor should provide a thorough guideline of the scope of the paper. In general, an undergraduate nursing research paper will consist of:

Introduction : A brief overview of the research question/thesis statement your paper will discuss. You can include why the topic is relevant.

Body : This section presents your research findings and allows you to synthesize the information and data you collected. You'll have a chance to articulate your evaluation and answer your research question. The length of this section depends on your assignment.

Conclusion : A brief review of the information and analysis you presented throughout the body of the paper. This section is a recap of your paper and another chance to reassert your thesis.

The best advice is to follow your instructor's rubric and guidelines. Remember to ask for help whenever needed, and avoid overcomplicating the assignment!

How to Choose a Nursing Research Topic

The sheer volume of prospective nursing research topics can become overwhelming for students. Additionally, you may get the misconception that all the 'good' research ideas are exhausted. However, a personal approach may help you narrow down a research topic and find a unique angle.

Writing your research paper about a topic you value or connect with makes the task easier. Additionally, you should consider the material's breadth. Topics with plenty of existing literature will make developing a research question and thesis smoother.

Finally, feel free to shift gears if necessary, especially if you're still early in the research process. If you start down one path and have trouble finding published information, ask your professor if you can choose another topic.

The Best Research Topics for Nursing Students

You have endless subject choices for nursing research papers. This non-exhaustive list just scratches the surface of some of the best nursing research topics.

1. Clinical Nursing Research Topics

- Analyze the use of telehealth/virtual nursing to reduce inpatient nurse duties.

- Discuss the impact of evidence-based respiratory interventions on patient outcomes in critical care settings.

- Explore the effectiveness of pain management protocols in pediatric patients.

2. Community Health Nursing Research Topics

- Assess the impact of nurse-led diabetes education in Type II Diabetics.

- Analyze the relationship between socioeconomic status and access to healthcare services.

3. Nurse Education Research Topics

- Review the effectiveness of simulation-based learning to improve nursing students' clinical skills.

- Identify methods that best prepare pre-licensure students for clinical practice.

- Investigate factors that influence nurses to pursue advanced degrees.

- Evaluate education methods that enhance cultural competence among nurses.

- Describe the role of mindfulness interventions in reducing stress and burnout among nurses.

4. Mental Health Nursing Research Topics

- Explore patient outcomes related to nurse staffing levels in acute behavioral health settings.

- Assess the effectiveness of mental health education among emergency room nurses .

- Explore de-escalation techniques that result in improved patient outcomes.

- Review the effectiveness of therapeutic communication in improving patient outcomes.

5. Pediatric Nursing Research Topics

- Assess the impact of parental involvement in pediatric asthma treatment adherence.

- Explore challenges related to chronic illness management in pediatric patients.

- Review the role of play therapy and other therapeutic interventions that alleviate anxiety among hospitalized children.

6. The Nursing Profession Research Topics

- Analyze the effects of short staffing on nurse burnout .

- Evaluate factors that facilitate resiliency among nursing professionals.

- Examine predictors of nurse dissatisfaction and burnout.

- Posit how nursing theories influence modern nursing practice.

Tips for Writing a Nursing Research Paper

The best nursing research advice we can provide is to follow your professor's rubric and instructions. However, here are a few study tips for nursing students to make paper writing less painful:

Avoid procrastination: Everyone says it, but few follow this advice. You can significantly lower your stress levels if you avoid procrastinating and start working on your project immediately.

Plan Ahead: Break down the writing process into smaller sections, especially if it seems overwhelming. Give yourself time for each step in the process.

Research: Use your resources and ask for help from the librarian or instructor. The rest should come together quickly once you find high-quality studies to analyze.

Outline: Create an outline to help you organize your thoughts. Then, you can plug in information throughout the research process.

Clear Language: Use plain language as much as possible to get your point across. Jargon is inevitable when writing academic nursing papers, but keep it to a minimum.

Cite Properly: Accurately cite all sources using the appropriate citation style. Nursing research papers will almost always implement APA style. Check out the resources below for some excellent reference management options.

Revise and Edit: Once you finish your first draft, put it away for one to two hours or, preferably, a whole day. Once you've placed some space between you and your paper, read through and edit for clarity, coherence, and grammatical errors. Reading your essay out loud is an excellent way to check for the 'flow' of the paper.

Helpful Nursing Research Writing Resources:

Purdue OWL (Online writing lab) has a robust APA guide covering everything you need about APA style and rules.

Grammarly helps you edit grammar, spelling, and punctuation. Upgrading to a paid plan will get you plagiarism detection, formatting, and engagement suggestions. This tool is excellent to help you simplify complicated sentences.

Mendeley is a free reference management software. It stores, organizes, and cites references. It has a Microsoft plug-in that inserts and correctly formats APA citations.

Don't let nursing research papers scare you away from starting nursing school or furthering your education. Their purpose is to develop skills you'll need to be an effective nurse: critical thinking, communication, and the ability to review published information critically.

Choose a great topic and follow your teacher's instructions; you'll finish that paper in no time.

Joleen Sams is a certified Family Nurse Practitioner based in the Kansas City metro area. During her 10-year RN career, Joleen worked in NICU, inpatient pediatrics, and regulatory compliance. Since graduating with her MSN-FNP in 2019, she has worked in urgent care and nursing administration. Connect with Joleen on LinkedIn or see more of her writing on her website.

Plus, get exclusive access to discounts for nurses, stay informed on the latest nurse news, and learn how to take the next steps in your career.

By clicking “Join Now”, you agree to receive email newsletters and special offers from Nurse.org. We will not sell or distribute your email address to any third party, and you may unsubscribe at any time by using the unsubscribe link, found at the bottom of every email.

150 Qualitative and Quantitative Nursing Research Topics for Students

Do not be lazy to spend some time researching and brainstorming. You can either lookup for the popular nursing research topics on social media networks or news or ask a professional writer online to take care of your assignment. What you should not do for sure is refuse to complete any of your course projects. You need every single task to be done if you wish to earn the highest score by the end of a semester.

In this article, we will share 150 excellent nursing research topics with you. Choose one of them or come up with your own idea based on our tips, and you’ll succeed for sure!

Table of Contents

Selecting the Top Ideas for Your Essays in Healthcare & Medicine

Would you like to learn how to pick research paper topics for nursing students? We will share some tips before offering lists of ideas.

Start with the preliminary research. You can get inspired on various websites offering ideas for students as well as academic help. Gather with your classmates and brainstorm by putting down different themes that you can cover. You should take your interests into consideration, but still, remember that ideas must relate to your lessons recently covered in class. You have to highlight keywords and main phrases to use in your text.

Before deciding on one of the numerous nursing school research topics, you should consult your tutor. Make sure that he or she approves the idea. Start writing only after that.

50 Popular Nursing Research Topics

Are you here to find the most popular research topics? They change with each new year as the innovations and technologies move on. We have collected the top discussed themes in healthcare for you.

- Problems Encountered by the Spouses of the Patients with Dyslexia

- Ethics in Geriatrics

- Checklist for the Delivery Room Behavior

- Parkinson Disease: Causes and Development

- Exercises Used to Improve Mental Health

- Effective Tips for Antenatal Treatment

- Syndrome of the Restless Legs: How to Treat It

- Behavior Assessment in Pediatric Primary Care

- Why Can Mother’s Health Be under the Threat During the Child Birth?

- Recommendations for Creating Strong Nursing Communities

- Alzheimer’s Disease and Proper Treatment

- Pre-Term Labor Threats

- Music Therapy and Lactation

- Influence of Ageism on Mental Health

- Newborn Resuscitation Practices

- Effective Therapy for Bladder Cancer

- Approaches to Improving Emotional Health of Nurses

- Skin-to-skin Contact by mothers and Its Consequences

- Does a Nurse Have a Right to Prescribe Drugs?

- Research on Atrial Fibrillation

- Pros & Cons of Water Birth

- Prevention Measures for Those Who Have to Contact Infectious Diseases

- Stroke Disease and Ways to Cure It

- The Role of Governmental Policies on the Hiring of Healthcare Professionals

- Demands for the Critical Care

- Joint Issue Research in Elderly Population

- Why Should Nurses and Healthcare Workers Cooperate?

- The Role of Good Leadership Skills in Nursing Profession

- How to Minimize the Threat of Cardiovascular Problems

- What Should a Nurse Do When an Elderly Refuses to Eat?

- Main Reasons for the Depression to Occur

- Methods Used to Detect an Abused Elderly Patient

- Treatment and Prevention of Acne and Other Skin Problems

- Consequences of the So-Called “Cold Therapy”

- End-of-Life Care Interventions That Work

- Risk factors for Osteoporosis in Female Population

- Alcohol Addiction and How to Get Rid of It

- Emerging Ethical Problems in Pain Management

- Psychiatric Patient Ethics

- How to Teach Female Population about Menopause Management

- Reasons for Aged Patients to Use Alcohol in Nursing Homes

- Family Engagement in Primary Healthcare

- Do the Race and Gender of a Patient Play a Role in Pain Management?

- PTSD in the Veterans of the United States Army

- How to Prepare a Nurse for Primary Healthcare

- The Correlation between Teen Aggression and Video Games

- Outcomes of Abdominal Massage in Critically Sick Population

- Developing an Effective Weight Loss Program: Case Study

- Comparing and Contrasting Public Health Nursing Models in Various Regions

- Mirror Therapy for Stroke Patients Who Are Partially Paralyzed

50 Interesting Nursing Research Topics

Do you wish to impress the target audience? Are you looking for the most interesting nursing research topics? It is important to consider time and recently covered themes. People tend to consider a topic an interesting one only if it is relevant. We have prepared the list of curious ideas for your project.

- Reasons for Hypertensive Diseases

- Self-Care Management and Sickle Cell Grown-Up Patients

- Schizophrenia Symptoms, Treatment, and Diagnostics

- Acute Coronary Syndrome Care

- Getting Ready with Caesarean Section

- What Are Some of the Cold and Cough Medicines?

- Why Do Patients Suffer from Anxiety Disorders?

- Use of the Forbidden Substances in Medicine

- How to Make Wise and Safe Medical Decisions

- CV Imaging Procedure

- Complementary vs. Alternative Therapy

- Can Some Types of Grains Prevent Cardiovascular Diseases?

- Restrictions of Medical Contracts

- How to Cope with High Levels of Stress

- Legal Threats with Non-English Patients

- The Basics of Palliative Care

- Clinical Cardiology Innovations

- How to Reduce Body Temperature in Household Conditions

- What Causes Type II Diabetes?

- Ways to Control Blood Pressure at Home

- Dental/Oral Health in the US

- Is There a Gender Bias in Nursing Profession?

- Gyno Education for the Young Girls

- Bipolar Disorder and Its Main Symptoms

- Methods Used to Recover after Physical Traumas

- The Principles of Sports Medicine

- The Gap between Female and Male Healthcare Professionals

- Increasing the Efficiency of Asthma Management in Educational Establishments

- Different Roles of Clinical Nurses

- Case Study: Successful Treatment of Migraine

- In-depth Analysis of the Ovarian Disorder

- Distant Intensive Treatment Until Questions

- Proper Treatment of Sleep Disorders

- How to Overcome Stressful Situations during Night Shifts

- Effective Methods to Prevent Breast Cancer

- Future of Healthcare & Medicine (Based on Modern Innovations)

- Approaches to Treating Insomnia

- Reproductive Endocrinology

- Diversity in the Field of Medicine

- Issues Associated with Menopause

- Causes and Effects of the Vaginal Atrophy

- Is Child’s Health Insurance a Right or a Privilege?

- Best Practices for Nursing Practitioners

- What Does the Phenomenon of Phantom Pains Stand for?

- Ethical Aspects of Infertility

- Protocol for Headache Treatment

- Moral Aspects of Euthanasia

- Treatment of Homeless People

- Why Should Healthcare System Be Made Free Everywhere in the World?

- Pain Restrictions Evaluation

50 Good Nursing Research Topics

Here is one more list of the nursing topics for research paper. We hope that at least one of these ideas will inspire you or give a clue.

- Advantages of Pet Therapy in Kids with the Autism Disorder

- Contemporary Approaches to Vaccinating Teenagers

- eHealth: The Effectiveness of Telecare and eCare

- Burn-Out in the Nursing Profession: Effective Ways to Handle Stress

- Healing of Bone Injuries

- Providing Spiritual Care: Does It Make Sense?

- Rheumatoid Arthritis: Opioid Usage

- Symptoms in ER That Cannot Be Explained by Medicine

- Contemporary Neonatal Practices

- Disorders with the Sexual Heath of an Average Woman

- Typical Causes of Headache

- Top Measures Used to Prevent Pregnancy

- Strategies Used by Government to Finance Healthcare System

- The Possible Consequences of Abortion for Women

- Evaluation of Childbirth Efficacy

- Quality Evaluation Techniques in Healthcare & Medicine

- Maternal Practices in Urban Areas

- Childcare Services Integration in Primary Medicine

- Rules for Pregnant Women Who Suffer from Obesity

- Mental Causes of Anorexia Nervosa

- Self-Instruction Kits

- Post-Natal Period Recommendations

- Midwifery Continuous Treatment & Care

- Case Study: Analyzing Positive Birth Experience

- Issues Related to the Gestational Weight Gain

- The Importance of Healthy Nutrition and Hydration

- What Are the Obligations of Every Nurse in Any Situation?

- Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment of ADHD

- Management of Disease and Prevention Methods

- The Importance of Kid and Teen Vaccination

- Termination of Pregnancy: Risks for Female Health

- Obligations of Every Pharmacist

- How to Prevent Child Obesity

- How to Stick to the Safe Sex Culture

- What Are the Main Symptoms of Autism?

- Ethics of the Healthcare Sales Promotion Campaigns

- Pros and Cons of Telemedicine

- Ethics in Pediatric Care

- Therapies Used to Treat Speech Disorders

- Medical Uniform Code Principles

- Psychological Sides of Infant Treatment

- Reasons for Seizures to Happen in Young Adolescents

- Healthcare Home Service and Self-Medicine

- How to Deal with Various Types of Eating Disorders

- Treatment of Patients in Prison

- Patient Security and Human Factors

- Bad Habits and Illnesses Impacted by Social Media and Pop Culture

- Apology Legislation and Regulations

- Antibiotic Resistance in Small Kids

- Nursing Marijuana Management & Control

You should also know that there are qualitative and quantitative nursing research topics. If you decide to base your study on numbers and figures, you should think about the second category. In quantitative research papers, writers must provide statistical data and interpret it to defend a thesis statement or find a solution to the existing problem.

Keep in mind that you can always count on the help of our professional essay writers. They will come up with the good nursing research topics and even compose the whole paper for you if you want.

15% OFF Your first order!

Aviable for the first 1000 subscribers, hurry up!

You might also like:

Why You Should Read a Data Gathering Procedure Example

What Is Culture and What Are Some Popular Culture Essay Topics?

Money-back guarantee

24/7 support hotline

Safe & secure online payment

Introduction to qualitative nursing research

This type of research can reveal important information that quantitative research can’t.

- Qualitative research is valuable because it approaches a phenomenon, such as a clinical problem, about which little is known by trying to understand its many facets.

- Most qualitative research is emergent, holistic, detailed, and uses many strategies to collect data.

- Qualitative research generates evidence and helps nurses determine patient preferences.

Research 101: Descriptive statistics

Differentiating research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement

How to appraise quantitative research articles

All nurses are expected to understand and apply evidence to their professional practice. Some of the evidence should be in the form of research, which fills gaps in knowledge, developing and expanding on current understanding. Both quantitative and qualitative research methods inform nursing practice, but quantitative research tends to be more emphasized. In addition, many nurses don’t feel comfortable conducting or evaluating qualitative research. But once you understand qualitative research, you can more easily apply it to your nursing practice.

What is qualitative research?

Defining qualitative research can be challenging. In fact, some authors suggest that providing a simple definition is contrary to the method’s philosophy. Qualitative research approaches a phenomenon, such as a clinical problem, from a place of unknowing and attempts to understand its many facets. This makes qualitative research particularly useful when little is known about a phenomenon because the research helps identify key concepts and constructs. Qualitative research sets the foundation for future quantitative or qualitative research. Qualitative research also can stand alone without quantitative research.

Although qualitative research is diverse, certain characteristics—holism, subjectivity, intersubjectivity, and situated contexts—guide its methodology. This type of research stresses the importance of studying each individual as a holistic system (holism) influenced by surroundings (situated contexts); each person develops his or her own subjective world (subjectivity) that’s influenced by interactions with others (intersubjectivity) and surroundings (situated contexts). Think of it this way: Each person experiences and interprets the world differently based on many factors, including his or her history and interactions. The truth is a composite of realities.

Qualitative research designs

Because qualitative research explores diverse topics and examines phenomena where little is known, designs and methodologies vary. Despite this variation, most qualitative research designs are emergent and holistic. In addition, they require merging data collection strategies and an intensely involved researcher. (See Research design characteristics .)

Although qualitative research designs are emergent, advanced planning and careful consideration should include identifying a phenomenon of interest, selecting a research design, indicating broad data collection strategies and opportunities to enhance study quality, and considering and/or setting aside (bracketing) personal biases, views, and assumptions.

Many qualitative research designs are used in nursing. Most originated in other disciplines, while some claim no link to a particular disciplinary tradition. Designs that aren’t linked to a discipline, such as descriptive designs, may borrow techniques from other methodologies; some authors don’t consider them to be rigorous (high-quality and trustworthy). (See Common qualitative research designs .)

Sampling approaches

Sampling approaches depend on the qualitative research design selected. However, in general, qualitative samples are small, nonrandom, emergently selected, and intensely studied. Qualitative research sampling is concerned with accurately representing and discovering meaning in experience, rather than generalizability. For this reason, researchers tend to look for participants or informants who are considered “information rich” because they maximize understanding by representing varying demographics and/or ranges of experiences. As a study progresses, researchers look for participants who confirm, challenge, modify, or enrich understanding of the phenomenon of interest. Many authors argue that the concepts and constructs discovered in qualitative research transcend a particular study, however, and find applicability to others. For example, consider a qualitative study about the lived experience of minority nursing faculty and the incivility they endure. The concepts learned in this study may transcend nursing or minority faculty members and also apply to other populations, such as foreign-born students, nurses, or faculty.

Qualitative nursing research can take many forms. The design you choose will depend on the question you’re trying to answer.

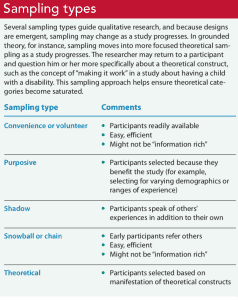

A sample size is estimated before a qualitative study begins, but the final sample size depends on the study scope, data quality, sensitivity of the research topic or phenomenon of interest, and researchers’ skills. For example, a study with a narrow scope, skilled researchers, and a nonsensitive topic likely will require a smaller sample. Data saturation frequently is a key consideration in final sample size. When no new insights or information are obtained, data saturation is attained and sampling stops, although researchers may analyze one or two more cases to be certain. (See Sampling types .)

Some controversy exists around the concept of saturation in qualitative nursing research. Thorne argues that saturation is a concept appropriate for grounded theory studies and not other study types. She suggests that “information power” is perhaps more appropriate terminology for qualitative nursing research sampling and sample size.

Data collection and analysis

Researchers are guided by their study design when choosing data collection and analysis methods. Common types of data collection include interviews (unstructured, semistructured, focus groups); observations of people, environments, or contexts; documents; records; artifacts; photographs; or journals. When collecting data, researchers must be mindful of gaining participant trust while also guarding against too much emotional involvement, ensuring comprehensive data collection and analysis, conducting appropriate data management, and engaging in reflexivity.

Data usually are recorded in detailed notes, memos, and audio or visual recordings, which frequently are transcribed verbatim and analyzed manually or using software programs, such as ATLAS.ti, HyperRESEARCH, MAXQDA, or NVivo. Analyzing qualitative data is complex work. Researchers act as reductionists, distilling enormous amounts of data into concise yet rich and valuable knowledge. They code or identify themes, translating abstract ideas into meaningful information. The good news is that qualitative research typically is easy to understand because it’s reported in stories told in everyday language.

Evaluating a qualitative study

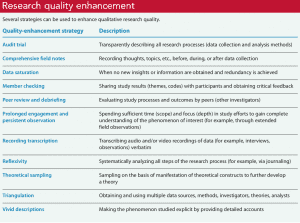

Evaluating qualitative research studies can be challenging. Many terms—rigor, validity, integrity, and trustworthiness—can describe study quality, but in the end you want to know whether the study’s findings accurately and comprehensively represent the phenomenon of interest. Many researchers identify a quality framework when discussing quality-enhancement strategies. Example frameworks include:

- Trustworthiness criteria framework, which enhances credibility, dependability, confirmability, transferability, and authenticity

- Validity in qualitative research framework, which enhances credibility, authenticity, criticality, integrity, explicitness, vividness, creativity, thoroughness, congruence, and sensitivity.

With all frameworks, many strategies can be used to help meet identified criteria and enhance quality. (See Research quality enhancement ). And considering the study as a whole is important to evaluating its quality and rigor. For example, when looking for evidence of rigor, look for a clear and concise report title that describes the research topic and design and an abstract that summarizes key points (background, purpose, methods, results, conclusions).

Application to nursing practice

Qualitative research not only generates evidence but also can help nurses determine patient preferences. Without qualitative research, we can’t truly understand others, including their interpretations, meanings, needs, and wants. Qualitative research isn’t generalizable in the traditional sense, but it helps nurses open their minds to others’ experiences. For example, nurses can protect patient autonomy by understanding them and not reducing them to universal protocols or plans. As Munhall states, “Each person we encounter help[s] us discover what is best for [him or her]. The other person, not us, is truly the expert knower of [him- or herself].” Qualitative nursing research helps us understand the complexity and many facets of a problem and gives us insights as we encourage others’ voices and searches for meaning.

When paired with clinical judgment and other evidence, qualitative research helps us implement evidence-based practice successfully. For example, a phenomenological inquiry into the lived experience of disaster workers might help expose strengths and weaknesses of individuals, populations, and systems, providing areas of focused intervention. Or a phenomenological study of the lived experience of critical-care patients might expose factors (such dark rooms or no visible clocks) that contribute to delirium.

Successful implementation

Qualitative nursing research guides understanding in practice and sets the foundation for future quantitative and qualitative research. Knowing how to conduct and evaluate qualitative research can help nurses implement evidence-based practice successfully.

When evaluating a qualitative study, you should consider it as a whole. The following questions to consider when examining study quality and evidence of rigor are adapted from the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.

Jennifer Chicca is a PhD candidate at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania in Indiana, Pennsylvania, and a part-time faculty member at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Amankwaa L. Creating protocols for trustworthiness in qualitative research. J Cult Divers. 2016;23(3):121-7.

Cuthbert CA, Moules N. The application of qualitative research findings to oncology nursing practice. Oncol Nurs Forum . 2014;41(6):683-5.

Guba E, Lincoln Y. Competing paradigms in qualitative research . In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.;1994: 105-17.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1985.

Munhall PL. Nursing Research: A Qualitative Perspective . 5th ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2012.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 1: Philosophies. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(1):26-33.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 2: Methodology. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(2):71-7.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 3: Methods. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(3):114-21.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med . 2014;89(9):1245-51.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice . 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

Thorne S. Saturation in qualitative nursing studies: Untangling the misleading message around saturation in qualitative nursing studies. Nurse Auth Ed. 2020;30(1):5. naepub.com/reporting-research/2020-30-1-5

Whittemore R, Chase SK, Mandle CL. Validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Res . 2001;11(4):522-37.

Williams B. Understanding qualitative research. Am Nurse Today . 2015;10(7):40-2.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post Comment

NurseLine Newsletter

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Hidden Referrer

*By submitting your e-mail, you are opting in to receiving information from Healthcom Media and Affiliates. The details, including your email address/mobile number, may be used to keep you informed about future products and services.

Test Your Knowledge

Recent posts.

Nearly 100 measles cases reported in the first quarter, CDC says

Infections after surgery are more likely due to bacteria already on your skin than from microbes in the hospital − new research

Honoring our veterans

Supporting the multi-generational nursing workforce

Vital practitioners

From data to action

Many travel nurses opt for temporary assignments because of the autonomy and opportunities − not just the big boost in pay

Effective clinical learning for nursing students

Nurse safety in the era of open notes

Collaboration: The key to patient care success

Health workers fear it’s profits before protection as CDC revisits airborne transmission

Why COVID-19 patients who could most benefit from Paxlovid still aren’t getting it

Human touch

Leadership style matters

My old stethoscope

- Renew Books

- pennwest.edu

CNUR 465/466: Topics in Nursing Research

- Books & eBooks

- Journals & Databases

- Web Resources

- Media Resources

- Quantitative Research

- Qualitative Research

- Data Collection

- Presenting Research

- Evidence-Based Practice

- Citing Sources in APA

- Help This link opens in a new window

What is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is research that seeks to provide understanding of human experience , perceptions, motivations, intentions, and behaviors based on description and observation , utilizing a naturalistic interpretative approach to a subject and its contextual setting. Observations in qualitative research are described in words .

Qualitative research starts with a situation the researcher can observe. One of the goals of qualitative research design is that participants are comfortable with the researcher and can be honest and forthcoming, allowing the researcher to make robust observations. Some examples of qualitative research methods include open-ended interviews, focus groups, and participant observation.

Adapted from Finding Quantitative or Qualitative Nursing Research Articles (Simmons University)

Types of Qualitative Research

The following are the most common types of qualitative research methods:

Case Study - Describes in-depth the experience of one person, family, group, community, or institution. Data is collected through direct observation and interaction with the subject.

Ethnography - Describes a culture's characteristics. The researcher identifies the culture, variables, and review literature, then collects data through immersion into the culture, informants, direct observation, and interaction with subjects.

Grounded Theory - The purpose of this research is theory development. Grounded theory is used in discovering what problems exist in a social scene and how persons handle them. It involves formulation, testing, and redevelopment of propositions until a theory is developed. Data is collected through interview, observation, record review, or a combination.

Historical Research - Used to describe and examine events of the past to understand the present and anticipate potential future effects. An idea is formulated after reading related literature, followed by the development of a research question and an inventory of sources. The researcher clarifies the validity and reliability of data from primary sources, then develops a research outline and collects data.

Phenomenology - Describes experiences as they are lived. The researcher examines the uniqueness of individuals' lived situations and develops research questions from these observations. There is no clearly defined method of data collection to avoid limiting the creativity of the researcher.

Adapted from Qualitative Research Designs

Selected eBooks (Qualitative Designs and Methods Series)

Video Resources

An Introduction to Qualitative Research (1 hour, 20 mins) From Academic Videos Online, this video presented by Jaime Dyce covers six areas: an introduction to qualitative research, qualitative data collection, qualitative data analysis, qualitative research in action, writing a qualitative research report, and ethics.

Fundamentals of Qualitative Research Methods: What is Qualitative Research? (YouTube) Qualitative research is a strategy for systematic collection, organization, and interpretation of phenomena that are difficulty to measure quantitatively. Dr. Leslie Curry from Yale University leads us through six modules covering essential topics in qualitative research, including what is qualitative research and how to use the most common methods, in-depth interviews and focus groups.

- << Previous: Quantitative Research

- Next: Data Collection >>

Nursing Research Guide

- General Search Strategies

- Searching by Author & Theory

- Searching for Qualitative Studies

- Searching for Systematic Reviews & Controlled Trials

- Health Data & Statistics

- Tutorials & Help

- SoN and APA (7th Ed.)

- NSC 890: PICOT Searches

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research in Nursing approaches a clinical question from a place of unknowing in an attempt to understand the complexity, depth, and richness of a particular situation from the perspective of the person or persons impacted by the situation (i.e., the subjects of the study).

Study subjects may include the patient(s), the patient's caregivers, the patient's family members, etc. Qualitative research may also include information gleaned from the investigator's or researcher's observations.

While typically more subjective than quantitative research (which focuses on measurements and numbers), qualitative research still employs a systematic approach.

Qualitative research is generally preferred over quantitative research (which on measurements and numbers) when the clinical question centers around life experiences or meaning.

Adapted from:

- Wilson, B., Austria, M.J., & Casucci, T. (2021 March 21). Understanding Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches

- Chicca, J. (2020 June 5). Introduction to qualitative nursing research. American Nurse Journal.

Where can I find qualitative research?

Qualitative research can be found in numerous databases. Some good starting options are:

- CINAHL Ultimate Journal articles and eBooks in nursing and allied health.

- MEDLINE (EBSCOhost Web) Journal articles in medicine, life sciences, health care, and biomedical research.

- APA PsycINFO Articles from journals, newspapers, and magazines, along with eBooks in nearly every social science subject area.

- PubMed Citation search of journal articles and books in health and life sciences.

How can I find qualitative research?

Cinahl and/or medline.

- Start at the Advanced Search screen.

- Add a search term that represents the topic you are interested in into one (or more) of the search boxes.

- Scroll down until you see the Limit your results section.

- Qualitative - High Sensitivity (broadest category/broad search)

- Qualitative - High Specificity (narrowest category/specific search)

- Qualitative - Best Balance (somewhere in between)

- Select or click the search button.

APA PsycINFO

- Start at the Advanced Search screen.

- Use the Methodology menu to select Qualitative .

- Use the drop-down menu next the Enter search term box to set the search to MeSH Terms

- Qualitative Research

- Nursing Methodology Research

How can I use keywords to search for qualitative research?

Try adding adding a keyword that might specifically identify qualitative research. You could add the term qualitative to your search and/or your could add different types of qualitative research according to your specific needs and/or research assignment.

For example, consider the following types of qualitative research in light of the types of questions a researcher might be trying to answer with each qualitative research type:

- Clinical question: What happens to the quality of nursing practice when we implement a peer-mentoring system?

- Clinical question: How is patient autonomy promoted by a unit?

- Clinical question: What is the nursing role in end-of-life decisions?

- Clinical question: What discourses are used in nursing practice and how do they shape practice?

- Clinical question: How does Filipino culture influence childbirth experiences?

- Clinical question: What are the immediate underlying psychological and environmental causes of incivility in nursing?

- Clinical question: How does the basic social process of role transition happen within the context of advanced practice nursing transitions?

- Clinical question: When and why did nurses become researchers?

- Clinical question: How does one live with a diagnosis of scleroderma?

- Clinical question: What is the lived experience of nurses who were admitted as patients on their home practice units?

Adapted from: Chicca, J. (2020 June 5). Introduction to qualitative nursing research . American Nurse Journal.

Need more help?

Finding relevant qualitative research can be both difficult and time consuming. Once you conduct a search, you will need to review your search results and look at individual articles, their subject terms, and abstracts to determine if they are truly qualitative research articles. And that's a determination that only you can make.

If you still need help after trying the search strategies and tips suggested on this research guide, we encourage you to schedule an in-person or Zoom research appointment . Health Services librarian Rachel Riffe-Albright is a great bet, but any librarian would be happy to help!

Additonal resources on qualitative research

The following are research guides created by other academic libraries. While you likely will not have access to any of their linked resources, the tips and tricks shared may be useful to you as you search for qualitative research:

- What is Qualitative Research? from UTA Libraries at University of Texas Arlington

- Finding Qualitative Research Articles from Ashland University Library

- Finding Qualitative Research Articles from the Health Sciences Library at University of Washington

- Advanced Search Guide: Qualitative and Quantitative Studies from Southern Connecticut State University Library

- Finding Qualitative and Quantitative Studies in CINAHL from Southern Connecticut State University Library

- << Previous: Searching by Author & Theory

- Next: Searching for Systematic Reviews & Controlled Trials >>

- Last Updated: Apr 22, 2024 2:39 PM

- URL: https://libguides.eku.edu/nursing

EO/AA Statement | Privacy Statement | 103 Libraries Complex Crabbe Library Richmond, KY 40475 | (859) 622-1790 ©

Library Research Guides - University of Wisconsin Ebling Library

Uw-madison libraries research guides.

- Course Guides

- Subject Guides

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Research Guides

- Nursing Resources

- Types of Research within Qualitative and Quantitative

Nursing Resources : Types of Research within Qualitative and Quantitative

- Definitions of

- Professional Organizations

- Nursing Informatics

- Nursing Related Apps

- EBP Resources

- PICO-Clinical Question

- Types of PICO Question (D, T, P, E)

- Secondary & Guidelines

- Bedside--Point of Care

- Pre-processed Evidence

- Measurement Tools, Surveys, Scales

- Types of Studies

- Table of Evidence

- Qualitative vs Quantitative

- Cohort vs Case studies

- Independent Variable VS Dependent Variable

- Sampling Methods and Statistics

- Systematic Reviews

- Review vs Systematic Review vs ETC...

- Standard, Guideline, Protocol, Policy

- Additional Guidelines Sources

- Peer Reviewed Articles

- Conducting a Literature Review

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- Writing a Research Paper or Poster

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Levels of Evidence (I-VII)

- Reliability

- Validity Threats

- Threats to Validity of Research Designs

- Nursing Theory

- Nursing Models

- PRISMA, RevMan, & GRADEPro

- ORCiD & NIH Submission System

- Understanding Predatory Journals

- Nursing Scope & Standards of Practice, 4th Ed

- Distance Ed & Scholarships

- Assess A Quantitative Study?

- Assess A Qualitative Study?

- Find Health Statistics?

- Choose A Citation Manager?

- Find Instruments, Measurements, and Tools

- Write a CV for a DNP or PhD?

- Find information about graduate programs?

- Learn more about Predatory Journals

- Get writing help?

- Choose a Citation Manager?

- Other questions you may have

- Search the Databases?

- Get Grad School information?

Aspects of Quantative (Empirical) Research

♦ Statement of purpose—what was studied and why.

♦ Description of the methodology (experimental group, control group, variables, test conditions, test subjects, etc.).

♦ Results (usually numeric in form presented in tables or graphs, often with statistical analysis).

♦ Conclusions drawn from the results.

♦ Footnotes, a bibliography, author credentials.

Hint: the abstract (summary) of an article is the first place to check for most of the above features. The abstract appears both in the database you search and at the top of the actual article.

Types of Quantitative Research

There are four (4) main types of quantitative designs: descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental.

samples.jbpub.com/9780763780586/80586_CH03_Keele.pdf

Types of Qualitative Research

http://wilderdom.com/OEcourses/PROFLIT/Class6Qualitative1.htm

- << Previous: Qualitative vs Quantitative

- Next: Cohort vs Case studies >>

- Last Updated: Mar 19, 2024 10:39 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.wisc.edu/nursing

- Library Basics

- Searching Databases

- Finding Full Text

- Overview Quantitative vs Qualitative

- Steps for Conducting a Literature Review

- Organizing a Literature Review

- Synthesizing Information for a Literature Review

- NoodleTools

Qualitative and Quantitative Research

In general, quantitative research seeks to understand the causal or correlational relationship between variables through testing hypotheses, whereas qualitative research seeks to understand a phenomenon within a real-world context through the use of interviews and observation. Both types of research are valid, and certain research topics are better suited to one approach or the other. However, it is important to understand the differences between qualitative and quantitative research so that you will be able to conduct an informed critique and analysis of any articles that you read, because you will understand the different advantages, disadvantages, and influencing factors for each approach.

The table below illustrates the main differences between qualitative and quantitative research. Be aware that these are generalizations, and that not every research study or article will fit neatly into these categories.

Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and integrative reviews are not exactly designs, but they synthesize, analyze, and compare the results from many research studies and are somewhat quantitative in nature. However, they are not truly quantitative or qualitative studies.

References:

LoBiondo-Wood, G., & Haber, J. (2010). Nursing research: Methods and critical appraisal for evidence-based practice (7 th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier

Mertens, D. M. (2010). Research and evaluation in education and psychology (3 rd ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE

Quick Overview

This 2-minute video provides a simplified overview of the primary distinctions between quantitative and qualitative research.

- << Previous: Finding Full Text

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 11:37 AM

- URL: https://stevenson.libguides.com/NURS520

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 14 June 2021

Nurses in the lead: a qualitative study on the development of distinct nursing roles in daily nursing practice

- Jannine van Schothorst–van Roekel 1 ,

- Anne Marie J.W.M. Weggelaar-Jansen 1 ,

- Carina C.G.J.M. Hilders 1 ,

- Antoinette A. De Bont 1 &

- Iris Wallenburg 1

BMC Nursing volume 20 , Article number: 97 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Transitions in healthcare delivery, such as the rapidly growing numbers of older people and increasing social and healthcare needs, combined with nursing shortages has sparked renewed interest in differentiations in nursing staff and skill mix. Policy attempts to implement new competency frameworks and job profiles often fails for not serving existing nursing practices. This study is aimed to understand how licensed vocational nurses (VNs) and nurses with a Bachelor of Science degree (BNs) shape distinct nursing roles in daily practice.

A qualitative study was conducted in four wards (neurology, oncology, pneumatology and surgery) of a Dutch teaching hospital. Various ethnographic methods were used: shadowing nurses in daily practice (65h), observations and participation in relevant meetings (n=56), informal conversations (up to 15 h), 22 semi-structured interviews and member-checking with four focus groups (19 nurses in total). Data was analyzed using thematic analysis.

Hospital nurses developed new role distinctions in a series of small-change experiments, based on action and appraisal. Our findings show that: (1) this developmental approach incorporated the nurses’ invisible work; (2) nurses’ roles evolved through the accumulation of small changes that included embedding the new routines in organizational structures; (3) the experimental approach supported the professionalization of nurses, enabling them to translate national legislation into hospital policies and supporting the nurses’ (bottom-up) evolution of practices. The new roles required the special knowledge and skills of Bachelor-trained nurses to support healthcare quality improvement and connect the patients’ needs to organizational capacity.

Conclusions

Conducting small-change experiments, anchored by action and appraisal rather than by design , clarified the distinctions between vocational and Bachelor-trained nurses. The process stimulated personal leadership and boosted the responsibility nurses feel for their own development and the nursing profession in general. This study indicates that experimental nursing role development provides opportunities for nursing professionalization and gives nurses, managers and policymakers the opportunity of a ‘two-way-window’ in nursing role development, aligning policy initiatives with daily nursing practices.

Peer Review reports

The aging population and mounting social and healthcare needs are challenging both healthcare delivery and the financial sustainability of healthcare systems [ 1 , 2 ]. Nurses play an important role in facing these contemporary challenges [ 3 , 4 ]. However, nursing shortages increase the workload which, in turn, boosts resignation numbers of nurses [ 5 , 6 ]. Research shows that nurses resign because they feel undervalued and have insufficient control over their professional practice and organization [ 7 , 8 ]. This issue has sparked renewed interest in nursing role development [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. A role can be defined by the activities assumed by one person, based on knowledge, modulated by professional norms, a legislative framework, the scope of practice and a social system [ 12 , 9 ].

New nursing roles usually arise through task specialization [ 13 , 14 ] and the development of advanced nursing roles [ 15 , 16 ]. Increasing attention is drawn to role distinction within nursing teams by differentiating the staff and skill mix to meet the challenges of nursing shortages, quality of care and low job satisfaction [ 17 , 18 ]. The staff and skill mix include the roles of enrolled nurses, registered nurses, and nurse assistants [ 19 , 20 ]. Studies on differentiation in staff and skill mix reveal that several countries struggle with the composition of nursing teams [ 21 , 22 , 23 ].

Role distinctions between licensed vocational-trained nurses (VNs) and Bachelor of Science-trained nurses (BNs) has been heavily debated since the introduction of the higher nurse education in the early 1970s, not only in the Netherlands [ 24 , 25 ] but also in Australia [ 26 , 27 ], Singapore [ 20 ] and the United States of America [ 28 , 29 ]. Current debates have focused on the difficulty of designing distinct nursing roles. For example, Gardner et al., revealed that registered nursing roles are not well defined and that job profiles focus on direct patient care [ 30 ]. Even when distinct nursing roles are described, there are no proper guidelines on how these roles should be differentiated and integrated into daily practice. Although the value of differentiating nursing roles has been recognized, it is still not clear how this should be done or how new nursing roles should be embedded in daily nursing practice. Furthermore, the consequences of these roles on nursing work has been insufficiently investigated [ 31 ].

This study reports on a study of nursing teams developing new roles in daily nursing hospital practice. In 2010, the Dutch Ministry of Health announced a law amendment (the Individual Health Care Professions Act) to formalize the distinction between VNs and BNs. The law amendment made a distinction in responsibilities regarding complexity of care, coordination of care, and quality improvement. Professional roles are usually developed top-down at policy level, through competency frameworks and job profiles that are subsequently implemented in nursing practice. In the Dutch case, a national expert committee made two distinct job profiles [ 32 ]. Instead of prescribing role implementation, however, healthcare organizations were granted the opportunity to develop these new nursing roles in practice, aiming for a more practice-based approach to reforming the nursing workforce. This study investigates a Dutch teaching hospital that used an experimental development process in which the nurses developed role distinctions by ‘doing and appraising’. This iterative process evolved in small changes [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ], based on nurses’ thorough knowledge of professional practices [ 37 ] and leadership role [ 38 , 39 , 40 ].

According to Abbott, the constitution of a new role is a competitive action, as it always leads to negotiation of new openings for one profession and/or degradation of adjacent professions [ 41 ]. Additionally, role differentiation requires negotiation between different professionals, which always takes place in the background of historical professionalization processes and vested interests resulting in power-related issues [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Recent studies have described the differentiation of nursing roles to other professionals, such as nurse practitioners and nurse assistants, but have focused on evaluating shifts in nursing tasks and roles [ 31 ]. Limited research has been conducted on differentiating between the different roles of registered nurses and the involvement of nurses themselves in developing new nursing roles. An ethnographic study was conducted to shed light on the nurses’ work of seeking openings and negotiating roles and responsibilities and the consequences of role distinctions, against a background of historically shaped relationships and patterns.

The study aimed to understand the formulation of nursing role distinctions between different educational levels in a development process involving experimental action (doing) and appraisal.

We conducted an ethnographic case study. This design was commonly used in nursing studies in researching changing professional practices [ 45 , 46 ]. The researchers gained detailed insights into the nurses’ actions and into the finetuning of their new roles in daily practice, including the meanings, beliefs and values nurses give to their roles [ 47 , 48 ]. This study complied with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist.

Setting and participants

Our study took place in a purposefully selected Dutch teaching hospital (481 beds, 2,600 employees including 800 nurses). Historically, nurses in Dutch hospitals have vocational training. The introduction of higher nursing education in 1972 prompted debates about distinguishing between vocational-trained nurses (VNs) and bachelor-trained nurses (BNs). For a long time, VNs resisted a role distinction, arguing that their work experience rendered them equally capable to take care of patients and deal with complex needs. As a result, VNs and BNs carry out the same duties and bear equal responsibility. To experiment with role distinctions in daily practice, the hospital management and project team selected a convenience but representative sample of wards. Two general (neurology and surgery) and two specific care (oncology and pneumatology) wards were selected as they represent the different compositions of nursing educational levels (VN, BN and additional specialized training). The demographic profile for the nursing teams is shown in Table 1 . The project team, comprising nursing policy staff, coaches and HR staff ( N = 7), supported the four (nursing) teams of the wards in their experimental development process (131 nurses; 32 % BNs and 68 % VNs, including seven senior nurses with an organizational role). We also studied the interactions between nurses and team managers ( N = 4), and the CEO ( N = 1) in the meetings.

Data collection

Data was collected between July 2017 and January 2019. A broad selection of respondents was made based on the different roles they performed. Respondents were personally approached by the first author, after close consultation with the team managers. Four qualitative research methods were used iteratively combining collection and analysis, as is common in ethnographic studies [ 45 ] (see Table 2 ).

Shadowing nurses (i.e. observations and questioning nurses about their work) on shift (65 h in total) was conducted to observe behavior in detail in the nurses’ organizational and social setting [ 49 , 50 ], both in existing practices and in the messy fragmented process of developing distinct nursing roles. The notes taken during shadowing were worked up in thick descriptions [ 46 ].

Observation and participation in four types of meetings. The first and second authors attended: (1) kick-off meetings for the nursing teams ( n = 2); (2) bi-monthly meetings ( n = 10) between BNs and the project team to share experiences and reflect on the challenges, successes and failures; and (3) project group meetings at which the nursing role developmental processes was discussed ( n = 20). Additionally, the first author observed nurses in ward meetings discussing the nursing role distinctions in daily practice ( n = 15). Minutes and detailed notes also produced thick descriptions [ 51 ]. This fieldwork provided a clear understanding of the experimental development process and how the respondents made sense of the challenges/problems, the chosen solutions and the changes to their work routines and organizational structures. During the fieldwork, informal conversations took place with nurses, nursing managers, project group members and the CEO (app. 15 h), which enabled us to reflect on the daily experiences and thus gain in-depth insights into practices and their meanings. The notes taken during the conversations were also written up in the thick description reports, shortly after, to ensure data validity [ 52 ]. These were completed with organizational documents, such as policy documents, activity plans, communication bulletins, formal minutes and in-house presentations.

Semi-structured interviews lasting 60–90 min were held by the first author with 22 respondents: the CEO ( n = 1), middle managers ( n = 4), VNs ( n = 6), BNs ( n = 9, including four senior nurses), paramedics ( n = 2) using a predefined topic list based on the shadowing, observations and informal conversations findings. In the interviews, questions were asked about task distinctions, different stakeholder roles (i.e., nurses, managers, project group), experimental approach, and added value of the different roles and how they influence other roles. General open questions were asked, including: “How do you distinguish between tasks in daily practice?”. As the conversation proceeded, the researcher asked more specific questions about what role differentiation meant to the respondent and their opinions and feelings. For example: “what does differentiation mean for you as a professional?”, and “what does it mean for you daily work?”, and “what does role distinction mean for collaboration in your team?” The interviews were tape-recorded (with permission), transcribed verbatim and anonymized.

The fieldwork period ended with four focus groups held by the first author on each of the four nursing wards ( N = 19 nurses in total: nine BNs, eight VNs, and two senior nurses). The groups discussed the findings, such as (nurses’ perceptions on) the emergence of role distinctions, the consequences of these role distinctions for nursing, experimenting as a strategy, the elements of a supportive environment and leadership. Questions were discussed like: “which distinctions are made between VN and BN roles?”, and “what does it mean for VNs, BNs and senior nurses?”. During these meetings, statements were also used to provoke opinions and discussion, e.g., “The role of the manager in developing distinct nursing roles is…”. With permission, all focus groups were audio recorded and the recordings were transcribed verbatim. The focus groups also served for member-checking and enriched data collection, together with the reflection meetings, in which the researchers reflected with the leader and a member of the project group members on program, progress, roles of actors and project outcomes. Finally, the researchers shared a report of the findings with all participants to check the credibility of the analysis.

Data analysis

Data collection and inductive thematic analysis took place iteratively [ 45 , 53 ]. The first author coded the data (i.e. observation reports, interview and focus group transcripts), basing the codes on the research question and theoretical notions on nursing role development and distinctions. In the next step, the research team discussed the codes until consensus was reached. Next, the first author did the thematic coding, based on actions and interactions in the nursing teams, the organizational consequences of their experimental development process, and relevant opinions that steered the development of nurse role distinctions (see Additional file ). Iteratively, the research team developed preliminary findings, which were fed back to the respondents to validate our analysis and deepen our insights [ 54 ]. After the analysis of the additional data gained in these validating discussions, codes were organized and re-organized until we had a coherent view.

Ethnography acknowledges the influence of the researcher, whose own (expert) knowledge, beliefs and values form part of the research process [ 48 ]. The first author was involved in the teams and meetings as an observer-as-participant, to gain in-depth insight, but remained research-oriented [ 55 ]. The focus was on the study of nursing actions, routines and accounts, asking questions to obtain insights into underlying assumptions, which the whole research group discussed to prevent ‘going native’ [ 56 , 57 ]. Rigor was further ensured by triangulating the various data resources (i.e. participants and research methods), purposefully gathered over time to secure consistency of findings and until saturation on a specific topic was reached [ 54 ]. The meetings in which the researchers shared the preliminary findings enabled nurses to make explicit their understanding of what works and why, how they perceived the nursing role distinctions and their views on experimental development processes.

Ethical considerations

All participants received verbal and written information, ensuring that they understood the study goals and role of the researcher [ 48 ]. Participants were informed about their voluntary participation and their right to end their contribution to the study. All gave informed consent. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Erasmus Medical Ethical Assessment Committee in Rotterdam (MEC-2019-0215), which also assessed the compliance with GDPR.

Our findings reveal how nurses gradually shaped new nursing role distinctions in an experimental process of action and appraisal and how the new BN nursing roles became embedded in new nursing routines, organizational routines and structures. Three empirical appeared from the systematic coding: (1) distinction based on complexity of care; (2) organizing hospital care; and (3) evidence-based practices (EBP) in quality improvement work.

Distinction based on complexity of care

Initially, nurses distinguished the VN and BN roles based on the complexity of patient care, as stated in national job profiles [ 32 ]. BNs were supposed to take care of clinically complex patients, rather than VNs, although both VNs and BNs had been equally taking care of every patient category. To distinguish between highly and less complex patient care, nurses developed a complexity measurement tool. This tool enabled classification of the predictability of care, patient’s degree of self-reliance, care intensity, technical nursing procedures and involvement of other disciplines. However, in practice, BNs questioned the validity of assessing a patient’s care complexity, because the assessments of different nurses often led to different outcomes. Furthermore, allocating complex patient care to BNs impacted negatively on the nurses’ job satisfaction, organizational routines and ultimately the quality of care. VNs experienced the shift of complex patient care to BNs as a diminution of their professional expertise. They continuously stressed their competencies and questioned the assigned levels of complexity, aiming to prevent losses to their professional tasks:

‘Now we’re only allowed to take care of COPD patients and people with pneumonia, so no more young boys with a pneumothorax drain. Suddenly we are not allowed to do that. (…) So, your [professional] world is getting smaller. We don’t like that at all. So, we said: We used to be competent, so why aren’t we anymore?’ (Interview VN1, in-service trained nurse).

In discussing complexity of care, both VNs and BNs (re)discovered the competencies VNs possess in providing complex daily care. BNs acknowledged the contestability of the distinction between VN and BN roles related to patient care complexity, as the next quote shows:

‘Complexity, they always make such a fuss about it. (…) At a given moment you’re an expert in just one certain area; try then to stand out on your ward. (…) When I go to GE [gastroenterology] I think how complex care is in here! (…) But it’s also the other way around, when I’m the expert and know what to expect after an angioplasty, or a bypass, or a laparoscopic cholecystectomy (…) When I’ve mastered it, then I no longer think it’s complex, because I know what to expect!’ (Interview BN1, 19-07-2017).

This quote illustrates how complexity was shaped through clinical experience. What complex care is , is influenced by the years of doing nursing work and hence is individual and remains invisible. It is not formally valued [ 58 ] because it is not included in the BN-VN competency model. This caused dissatisfaction and feelings of demotion among VNs. The distinction in complexities of care was also problematic for BNs. Following the complexity tool, recently graduated BNs were supposed to look after highly complex patients. However, they often felt insecure and needed the support of more experienced (VN) colleagues – which the VNs perceived as a recognition of their added value and evidence of the failure of the complexity tool to guide division of tasks. Also, mundane issues like holidays, sickness or pregnancy leave further complicated the use of the complexity tool as a way of allocating patients, as it decreased flexibility in taking over and swapping shifts, causing dissatisfaction with the work schedule and leading to problems in the continuity of care during evening, night and weekend shifts. Hence, the complexity tool disturbed the flexibility in organizing the ward and held possible consequences for the quality and safety of care (e.g. inexperienced BNs providing complex care), Ultimately, the complexity tool upset traditional teamwork, in which nurses more implicitly complemented each other’s competencies and ability to ‘get the work done’ [ 59 ]. As a result, role distinction based on ‘quantifiable’ complexity of care was abolished. Attention shifted to the development of an organizational and quality-enhancing role, seeking to highlight the added value of BNs – which we will elaborate on in the next section.

Organizing hospital care

Nurses increasingly fulfill a coordinating role in healthcare, making connections across occupational, departmental and organizational boundaries, and ‘mediating’ individual patient needs, which Allen describes as organizing work [ 49 ]. Attempting to make a valuable distinction between nursing roles, BNs adopted coordinating management tasks at the ward level, taking over this task from senior nurses and team managers. BNs sought to connect the coordinating management tasks with their clinical role and expertise. An example is bed management, which involves comparing a ward’s bed capacity with nursing staff capacity [ 1 , 60 ]. At first, BNs accompanied middle managers to the hospital bed review meeting to discuss and assess patient transfers. On the wards where this coordination task used to be assigned to senior nurses, the process of transferring this task to BNs was complicated. Senior nurses were reluctant to hand over coordinating tasks as this might undermine their position in the near future. Initially, BNs were hesitant to take over this task, but found a strategy to overcome their uncertainty. This is reflected in the next excerpt from fieldnotes:

Senior nurse: ‘First we have to figure out if it will work, don’t we? I mean, all three of us [middle manager, senior nurse, BN] can’t just turn up at the bed review meeting, can we? The BN has to know what to do first, otherwise she won’t be able to coordinate properly. We can’t just do it.’ BN: ‘I think we should keep things small, just start doing it, step by step. (…) If we don’t try it out, we don’t know if it works.’ (Field notes, 24-05-2018).

This excerpt shows that nurses gradually developed new roles as a series of matching tasks. Trying out and evaluating each step of development in the process overcame the uncertainty and discomfort all parties held [ 61 ]. Moreover, carrying out the new tasks made the role distinctions become apparent. The coordinating role in bed management, for instance, became increasingly embedded in the new BN nursing role. Experimenting with coordination allowed BNs prove their added value [ 62 ] and contributed to overall hospital performance as it combined daily working routines with their ability to manage bed occupancy, patient flow, staffing issues and workload. This was not an easy task. The next quote shows the complexity of creating room for this organizing role:

The BNs decide to let the VNs help coordinate the daily care, as some VNs want to do this task. One BN explains: ‘It’s very hard to say, you’re not allowed.’ The middle manager looks surprised and says that daily coordination is a chance to draw a clear distinction and further shape the role of BNs. The project group leader replies: ‘Being a BN means that you dare to make a difference [in distinctive roles]. We’re all newbies in this field, but we can use our shared knowledge. You can derive support from this task for your new role.’ (Field notes, 09-01-2018).

This excerpt reveals the BNs’ thinking on crafting their organizational role, turning down the VNs wishes to bear equal responsibility for coordinating tasks. Taking up this role touched on nurse identity as BNs had to overcome the delicate issue of equity [ 63 ], which has long been a core element of the Dutch nursing profession. Taking over an organization role caused discomfort among BNs, but at the same time provided legitimation for a role distinction.

Legitimation for this task was also gained from external sources, as the law amendment and the expert committee’s job descriptions both mentioned coordinating tasks. However, taking over coordinating tasks and having an organizing role in hospital care was not done as an ‘implementation’; rather it required a process of actively crafting and carving out this new role. We observed BNs choosing not to disclose that they were experimenting with taking over the coordinating tasks as they anticipated a lack of support from VNs:

BN: ‘We shouldn’t tell the VNs everything. We just need this time to give shape to our new role. And we all know who [of the colleagues] won’t agree with it. In my opinion, we’d be better off hinting at it at lunchtime, for example, to figure out what colleagues think about it. And then go on as usual.’ (Field notes, 12-06-2018).

BNs stayed ‘under the radar’, not talking explicitly about their fragile new role to protect the small coordination tasks they had already gained. By deliberately keeping the evaluation of their new task to themselves, they protected the transition they had set into motion. Thus, nurses collected small changes in their daily routines, developing a new role distinction step by step. Changes to single tasks accumulated in a new role distinction between BNs, VNs and senior nurses, and gave BNs a more hybrid nursing management role.

Evidence-based practices in quality improvement work

Quality improvement appeared to be another key concern in the development of the new BN role. Quality improvement work used to be carried out by groups of senior nurses, middle managers and quality advisory staff. Not involved in daily routines, the working group focused on nursing procedures (e.g. changing infusion system and wound treatment protocols). In taking on this new role BNs tried different ways of incorporating EBP in their routines, an aspect that had long been neglected in the Netherlands. As a first step, BNs rearranged the routines of the working group. For example, a team of BNs conducted a quality improvement investigation of a patient’s formal’s complaint:

Twenty-two patients registered a pain score of seven or higher and were still discharged. The question for BNs was: how and why did this bad care happen? The BNs used electronic patient record to study data on the relations between pain, medication and treatment. Their investigation concluded: nurses do not always follow the protocols for high pain scores. Their improvement plan covered standard medication policy, clinical lessons on pain management and revisions to the patient information folder. One BN said: ‘I really loved investigating this improvement.’ (Field notes, 28-05-2018).

This fieldnote shows the joy quality improvement work can bring. During interviews, nurses said that it had given them a better grip on the outcome of nursing work. BNs felt the need to enhance their quality improvement tasks with their EBP skills, e.g. using clinical reasoning in bedside teaching, formulating and answering research questions in clinical lessons and in multi-disciplinary patient rounds to render nursing work more evidence based. The BNs blended EBP-related education into shift handovers and ward meetings, to show VNs the value of doing EBP [ 64 ]. In doing so, they integrated and fostered an EBP infrastructure of care provision, reflecting a new sense of professionalism and responsibility for quality of care.