Open Access Theses and Dissertations

Thursday, April 18, 8:20am (EDT): Searching is temporarily offline. We apologize for the inconvenience and are working to bring searching back up as quickly as possible.

Advanced research and scholarship. Theses and dissertations, free to find, free to use.

Advanced search options

Browse by author name (“Author name starts with…”).

Find ETDs with:

Written in any language English Portuguese French German Spanish Swedish Lithuanian Dutch Italian Chinese Finnish Greek Published in any country US or Canada Argentina Australia Austria Belgium Bolivia Brazil Canada Chile China Colombia Czech Republic Denmark Estonia Finland France Germany Greece Hong Kong Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Ireland Italy Japan Latvia Lithuania Malaysia Mexico Netherlands New Zealand Norway Peru Portugal Russia Singapore South Africa South Korea Spain Sweden Switzerland Taiwan Thailand UK US Earliest date Latest date

Sorted by Relevance Author University Date

Only ETDs with Creative Commons licenses

Results per page: 30 60 100

October 3, 2022. OATD is dealing with a number of misbehaved crawlers and robots, and is currently taking some steps to minimize their impact on the system. This may require you to click through some security screen. Our apologies for any inconvenience.

Recent Additions

See all of this week’s new additions.

About OATD.org

OATD.org aims to be the best possible resource for finding open access graduate theses and dissertations published around the world. Metadata (information about the theses) comes from over 1100 colleges, universities, and research institutions . OATD currently indexes 7,241,108 theses and dissertations.

About OATD (our FAQ) .

Visual OATD.org

We’re happy to present several data visualizations to give an overall sense of the OATD.org collection by county of publication, language, and field of study.

You may also want to consult these sites to search for other theses:

- Google Scholar

- NDLTD , the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations. NDLTD provides information and a search engine for electronic theses and dissertations (ETDs), whether they are open access or not.

- Proquest Theses and Dissertations (PQDT), a database of dissertations and theses, whether they were published electronically or in print, and mostly available for purchase. Access to PQDT may be limited; consult your local library for access information.

Librarians/Admins

- EBSCOhost Collection Manager

- EBSCO Experience Manager

- EBSCO Connect

- Start your research

- EBSCO Mobile App

Clinical Decisions Users

- DynaMed Decisions

- Dynamic Health

- Waiting Rooms

- NoveList Blog

EBSCO Open Dissertations

EBSCO Open Dissertations makes electronic theses and dissertations (ETDs) more accessible to researchers worldwide. The free portal is designed to benefit universities and their students and make ETDs more discoverable.

Increasing Discovery & Usage of ETD Research

EBSCO Open Dissertations is a collaboration between EBSCO and BiblioLabs to increase traffic and discoverability of ETD research. You can join the movement and add your theses and dissertations to the database, making them freely available to researchers everywhere while increasing traffic to your institutional repository.

EBSCO Open Dissertations extends the work started in 2014, when EBSCO and the H.W. Wilson Foundation created American Doctoral Dissertations which contained indexing from the H.W. Wilson print publication, Doctoral Dissertations Accepted by American Universities, 1933-1955. In 2015, the H.W. Wilson Foundation agreed to support the expansion of the scope of the American Doctoral Dissertations database to include records for dissertations and theses from 1955 to the present.

How Does EBSCO Open Dissertations Work?

Your ETD metadata is harvested via OAI and integrated into EBSCO’s platform, where pointers send traffic to your IR.

EBSCO integrates this data into their current subscriber environments and makes the data available on the open web via opendissertations.org .

You might also be interested in:

Free Databases (all subjects): Dissertations

- Anthropology

- Theater Arts

- Criminal Justice

- Dissertations

- Ethnic Studies

- Free Online Journals

- Gerontology

- Kinesiology

- Library Science

- Political Science

- Encyclopedias

- Dictionaries

- Style and Citation Guides

- Engineering

- Environment

- Physics/Astronomy

- Science Education

- Statistical Sources

- Women's Studies

Dissertations and Theses

- EBSCO Open Dissertations

- Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations Provides free access to thousands of dissertation and thesis abstracts from universities around the world, and links to full text when freely available.

- << Previous: Criminal Justice

- Next: Economics >>

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2024 2:48 PM

- URL: https://csulb.libguides.com/freedatabases

“The only truly modern academic research engine”

Oa.mg is a search engine for academic papers, specialising in open access. we have over 250 million papers in our index..

All virtual services are available and some libraries are open for in-person use, while others remain closed through January 23, 2022. Learn more .

- Ask a Librarian

How can I find theses and dissertations?

- COVID-19 Spring 2020

- FAS General

- Harvard Map Collection

- Houghton Library

- How to Do Research in...

- 2 African American Studies

- 1 Anthropology

- 1 Art in Harvard Libraries

- 2 Asian Studies

- 1 Audio Books

- 1 Biography

- 4 Borrow Direct

- 13 Borrowing

- 1 Calendars

- 6 Citation of Sources

- 1 Citation Tools

- 1 Computer Science

- 5 Computers

- 4 contemporary legends

- 1 Copyright

- 3 Crimson Cash

- 9 Databases

- 2 Digital Collections

- 2 Distance Learning

- 28 E-Resources

- 1 Economics

- 5 Electronic Books

- 1 Employment

- 1 Equipment

- 1 Extension School

- 1 Foreign Study

- 2 Genealogy

- 3 Government

- 2 Government Documents

- 1 Harvard Depository

- 3 Harvard Studies

- 3 Harvard University Archives

- 32 Harvardiana

- 5 HOLLIS help

- 5 Interlibrary Loan

- 1 Internet access

- 1 Language Resource Center

- 2 Languages

- 9 Libraries

- 3 Library History

- 1 Library science

- 3 Library services

- 1 Library student

- 1 Literature

- 2 Manuscripts

- 2 Microfilm

- 17 miscellaneous

- 17 Newspapers

- 4 Off-Campus

- 1 Permissions

- 1 Phillips Reading Room

- 3 Photographs

- 1 Plagiarism

- 4 Primary Sources

- 12 Privileges

- 1 Public Libraries

- 2 Purchase requests

- 4 Quotations

- 2 Rare Books

- 4 Reference

- 1 Reproduction Request

- 22 Research Assistance

- 1 Safari Books Online

- 1 Scan & Deliver

- 4 Special Borrowers

- 2 Special Collections

- 5 Statistics

- 1 Study Abroad

- 3 Study spaces

- 1 Summer School

- 2 technology

- 5 Theses, Dissertations & Prize Winners

- 3 Web of Science

For Harvard theses, dissertations, and prize winning essays, see our How can I find a Harvard thesis or dissertation ? FAQ entry.

Beyond Harvard, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses G lobal database (this link requires HarvardKey login) i s a good place to start:

- lists dissertations and theses from most North American graduate schools (including Harvard) and many from universities in Great Britain and Ireland, 1716-present

- You can get full text from Proquest Dissertations and Theses through your own institutional library or you can often purchase directly from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Express.

Other sources:

Databases beyond ProQuest Dissertations & Theses:

Some out of copyright works (pre-1924) are available via large digital libraries. Search online for the title.

Networked Digital Library of Electronic Theses and Dissertations ' Global Search scans participating international libraries

The Center for Research Libraries ' Dissertations database includes many non-US theses.

WorldCat describes many masters' & PhD theses. Use "Advanced Search" and limit to subtype "thesis/dissertation." No full text; it just tells you what libraries have reported having copies.

There are several excellent guides out there with international search recommendations like University College London's Institute of Education Theses and Dissertations LibGuide .

Institutions:

At the institution where the work originated or the national library of the country (if outside the US):

Online institutional repositories (like Harvard's DASH ): If the work was produced after the school's repository was established, it may well be found here in full text.

Libraries: Check the library catalog. There's often a reproductions service ($) for material that hasn't been digitized, but each school has its own policies. Most schools have some kind of "ask a librarian" service where you can ask what to do next.

At your own institution (where applicable) or public library: While many institutions will not lend theses and dissertations or send copies through Interlibrary loan, your Interlibrary Loan department may be able to help you acquire or pay for reproductions.

- Current Harvard faculty, staff and students: Once you identify a reproduction source you can place a request with Harvard Library ILL (in the notes field, ask for help with funding).

For Harvard theses and dissertations, see " How can I find a Harvard thesis or dissertation? "

If you're having trouble locating or acquiring a copy of/access to a dissertation, try " Why can't I find this thesis or dissertation?"

- Ask a Librarian, including chat and email, will be suspended from 5:00 pm on Thursday, December 22, through Monday, January 2, for the holiday break. Any questions received during this period will be answered beginning Tuesday, January 2, 2024 .

- If If you're experiencing an ongoing technical issue when you attempt to access library materials with your HarvardKey during these times, please report it to Library Technology Services.

Monday-Thursday 9am-9pm

Friday-Saturday 9am-5pm

Sunday 12noon-7pm

Chat is intended for brief inquiries from the Harvard community.

Reach out to librarians and other reference specialists by email using our online form . We usually respond within 24 hours Monday through Friday.

Talk to a librarian for advice on defining your topic, developing your research strategy, and locating and using sources. Make an appointment now .

These services are intended primarily for Harvard University faculty, staff and students. If you are not affiliated with Harvard, please use these services only to request information about the Library and its collections.

- Email Us: [email protected]

- Call Us: 617-495-2411

- All Library Hours

- Library Guides

- Staff Login

Harvard Library Virtual Reference Policy Statement

Our chat reference and Research Appointment Request services are intended for Harvard affiliates. All others are welcome to submit questions using the form on this page.

We are happy to answer questions from all Harvard affiliates and from non-affiliates inquiring about the library's collections.

Unfortunately, we're unable to answer questions from the general public which are not directly related to Harvard Library services and collections.

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER COLUMN

- 07 July 2022

How to find, read and organize papers

- Maya Gosztyla 0

Maya Gosztyla is a PhD student in biomedical sciences at the University of California, San Diego.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

“I’ll read that later,” I told myself as I added yet another paper to my 100+ open browser tabs.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-01878-7

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged .

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Related Articles

- Research management

I’m worried I’ve been contacted by a predatory publisher — how do I find out?

Career Feature 15 MAY 24

How I fled bombed Aleppo to continue my career in science

Career Feature 08 MAY 24

Illuminating ‘the ugly side of science’: fresh incentives for reporting negative results

Japan can embrace open science — but flexible approaches are key

Correspondence 07 MAY 24

US funders to tighten oversight of controversial ‘gain of function’ research

News 07 MAY 24

France’s research mega-campus faces leadership crisis

News 03 MAY 24

Hunger on campus: why US PhD students are fighting over food

Career Feature 03 MAY 24

Senior Research Assistant in Human Immunology (wet lab)

Senior Research Scientist in Human Immunology, high-dimensional (40+) cytometry, ICS and automated robotic platforms.

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Boston University Atomic Lab

Postdoctoral Fellow in Systems Immunology (dry lab)

Postdoc in systems immunology with expertise in AI and data-driven approaches for deciphering human immune responses to vaccines and diseases.

Global Talent Recruitment of Xinjiang University in 2024

Recruitment involves disciplines that can contact the person in charge by phone.

Wulumuqi city, Ürümqi, Xinjiang Province, China

Xinjiang University

Tenure-Track Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Professor

Westlake Center for Genome Editing seeks exceptional scholars in the many areas.

Westlake Center for Genome Editing, Westlake University

Faculty Positions at SUSTech School of Medicine

SUSTech School of Medicine offers equal opportunities and welcome applicants from the world with all ethnic backgrounds.

Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

Southern University of Science and Technology, School of Medicine

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- TutorHome |

- IntranetHome |

- Contact the OU Contact the OU Contact the OU |

- Accessibility Accessibility

- StudentHome

- Help Centre

You are here

Library resources.

- Theses & dissertations

- Site Accessibility: Library Services

OU theses and dissertations

Online theses.

Are available via Open Research Online .

Print theses

Search for OU theses in the Library Search . To see only print theses click 'In the Walton Hall library' and refine your results to resource type 'Thesis'.

OU staff and research students can borrow a consultation copy of a thesis (if available). Please contact the Library helpdesk giving the author and title of the thesis.

UK theses and dissertations from EThOS

The Electronic Theses Online System (EThOS) offers free access to the full text of UK theses.

- EThOS offers a one stop online shop providing free access to UK theses

- EThOS digitizes theses on request into PDF format, this may require payment

- EThOS is managed by the British Library in partnership with a number of UK universities

- EThOS is open to all categories of library user

What does this mean to you as a library user?

When you need to access a PhD thesis from another UK based HE institution you should check EThOS to either download a thesis which has already been digitised or to request that a UK thesis be supplied to you.

- For all UK theses EThOS will be the first point of delivery. You can use the online ordering and tracking system direct from EThOS to manage your requests for UK PhD theses, including checking the status of your requests

- As readers you will deal directly with EThOS so will not need to fill in a document delivery request

- OU staff and research students will still be entitled to access non-UK based PhD theses by filling in a document delivery request

- In some cases where EThOS is unable to supply a UK thesis OU staff and research students will be able to access it by filling in a conventional document delivery request. The thesis will be supplied through direct loan

- The EThOS system is both faster and cheaper than the previous British Theses service which was based on microfilm

- The British Library no longer arranges interlibrary loans for UK PhD theses

- Interlibrary Loan procedures for other types of request from the British Library (articles and books for example) will remain the same

If you have any queries about using EThOS contact the Document Delivery Team ( [email protected] or the Library Helpdesk ).

Note 13/03/2024: The British Library is continuing to experience a major technology outage affecting its websites and other online systems, due to a Cyber attack. as a result access to ETHOS might not be possible until the issue is fixed.

- Selected resources for your study

- Explore Curated Resources

- Dictionaries, thesauri and encyclopaedias

- Biographies

- Conference papers

- Country information

- External libraries and catalogues

- Images and sound

- Legislation and official publications

- News sources

- Open Research collections

- Patents and standards

- Publicly available

- Statistics sources

- The Open University Archive

Related Help

- Finding and using books and theses

- Finding resources for your assignment

- I am having problems accessing a resource via Athens.

- Training and skills

- How do I do a literature search?

Using Library Search for your assignment

Monday, 24 June, 2024 - 19:30

Learn how to find specific resources and how to find information on a topic using Library Search.

Library Helpdesk

Chat to a Librarian - Available 24/7

Other ways to contact the Library Helpdesk

The Open University

- Study with us

- Supported distance learning

- Funding your studies

- International students

- Global reputation

- Apprenticeships

- Develop your workforce

- News & media

- Contact the OU

Undergraduate

- Arts and Humanities

- Art History

- Business and Management

- Combined Studies

- Computing and IT

- Counselling

- Creative Writing

- Criminology

- Early Years

- Electronic Engineering

- Engineering

- Environment

- Film and Media

- Health and Social Care

- Health and Wellbeing

- Health Sciences

- International Studies

- Mathematics

- Mental Health

- Nursing and Healthcare

- Religious Studies

- Social Sciences

- Social Work

- Software Engineering

- Sport and Fitness

Postgraduate

- Postgraduate study

- Research degrees

- Masters in Art History (MA)

- Masters in Computing (MSc)

- Masters in Creative Writing (MA)

- Masters degree in Education

- Masters in Engineering (MSc)

- Masters in English Literature (MA)

- Masters in History (MA)

- Master of Laws (LLM)

- Masters in Mathematics (MSc)

- Masters in Psychology (MSc)

- A to Z of Masters degrees

- Accessibility statement

- Conditions of use

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Manage cookie preferences

- Modern slavery act (pdf 149kb)

Follow us on Social media

- Student Policies and Regulations

- Student Charter

- System Status

- Contact the OU Contact the OU

- Modern Slavery Act (pdf 149kb)

© . . .

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Faculty of Arts & Sciences Libraries

Computer Science Library Research Guide

Find dissertations and theses.

- Get Started

- How to get the full-text

- What is Peer Review?

- Find Books in the SEC Library This link opens in a new window

- Find Conference Proceedings

- Find Patents This link opens in a new window

- Find Standards

- Find Technical Reports

- Find Videos

- Ask a Librarian This link opens in a new window

Engineering Librarian

How to search for Harvard dissertations

- DASH , Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard, is the university's central, open-access repository for the scholarly output of faculty and the broader research community at Harvard. Most Ph.D. dissertations submitted from March 2012 forward are available online in DASH.

- Check HOLLIS, the Library Catalog, and refine your results by using the Advanced Search and limiting Resource Type to Dissertations

- Search the database ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global Don't hesitate to Ask a Librarian for assistance.

How to search for Non-Harvard dissertations

Library Database:

- ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global

Free Resources:

- Many universities provide full-text access to their dissertations via a digital repository. If you know the title of a particular dissertation or thesis, try doing a Google search.

Related Sites

- Formatting Your Dissertation - GSAS

- Ph.D. Dissertation Submission - FAS

- Empowering Students Before you Sign that Contract! - Copyright at Harvard Library

Select Library Titles

- << Previous: Find Conference Proceedings

- Next: Find Patents >>

- Last Updated: Feb 27, 2024 1:52 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/cs

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a thesis statement + examples

What is a thesis statement?

Is a thesis statement a question, how do you write a good thesis statement, how do i know if my thesis statement is good, examples of thesis statements, helpful resources on how to write a thesis statement, frequently asked questions about writing a thesis statement, related articles.

A thesis statement is the main argument of your paper or thesis.

The thesis statement is one of the most important elements of any piece of academic writing . It is a brief statement of your paper’s main argument. Essentially, you are stating what you will be writing about.

You can see your thesis statement as an answer to a question. While it also contains the question, it should really give an answer to the question with new information and not just restate or reiterate it.

Your thesis statement is part of your introduction. Learn more about how to write a good thesis introduction in our introduction guide .

A thesis statement is not a question. A statement must be arguable and provable through evidence and analysis. While your thesis might stem from a research question, it should be in the form of a statement.

Tip: A thesis statement is typically 1-2 sentences. For a longer project like a thesis, the statement may be several sentences or a paragraph.

A good thesis statement needs to do the following:

- Condense the main idea of your thesis into one or two sentences.

- Answer your project’s main research question.

- Clearly state your position in relation to the topic .

- Make an argument that requires support or evidence.

Once you have written down a thesis statement, check if it fulfills the following criteria:

- Your statement needs to be provable by evidence. As an argument, a thesis statement needs to be debatable.

- Your statement needs to be precise. Do not give away too much information in the thesis statement and do not load it with unnecessary information.

- Your statement cannot say that one solution is simply right or simply wrong as a matter of fact. You should draw upon verified facts to persuade the reader of your solution, but you cannot just declare something as right or wrong.

As previously mentioned, your thesis statement should answer a question.

If the question is:

What do you think the City of New York should do to reduce traffic congestion?

A good thesis statement restates the question and answers it:

In this paper, I will argue that the City of New York should focus on providing exclusive lanes for public transport and adaptive traffic signals to reduce traffic congestion by the year 2035.

Here is another example. If the question is:

How can we end poverty?

A good thesis statement should give more than one solution to the problem in question:

In this paper, I will argue that introducing universal basic income can help reduce poverty and positively impact the way we work.

- The Writing Center of the University of North Carolina has a list of questions to ask to see if your thesis is strong .

A thesis statement is part of the introduction of your paper. It is usually found in the first or second paragraph to let the reader know your research purpose from the beginning.

In general, a thesis statement should have one or two sentences. But the length really depends on the overall length of your project. Take a look at our guide about the length of thesis statements for more insight on this topic.

Here is a list of Thesis Statement Examples that will help you understand better how to write them.

Every good essay should include a thesis statement as part of its introduction, no matter the academic level. Of course, if you are a high school student you are not expected to have the same type of thesis as a PhD student.

Here is a great YouTube tutorial showing How To Write An Essay: Thesis Statements .

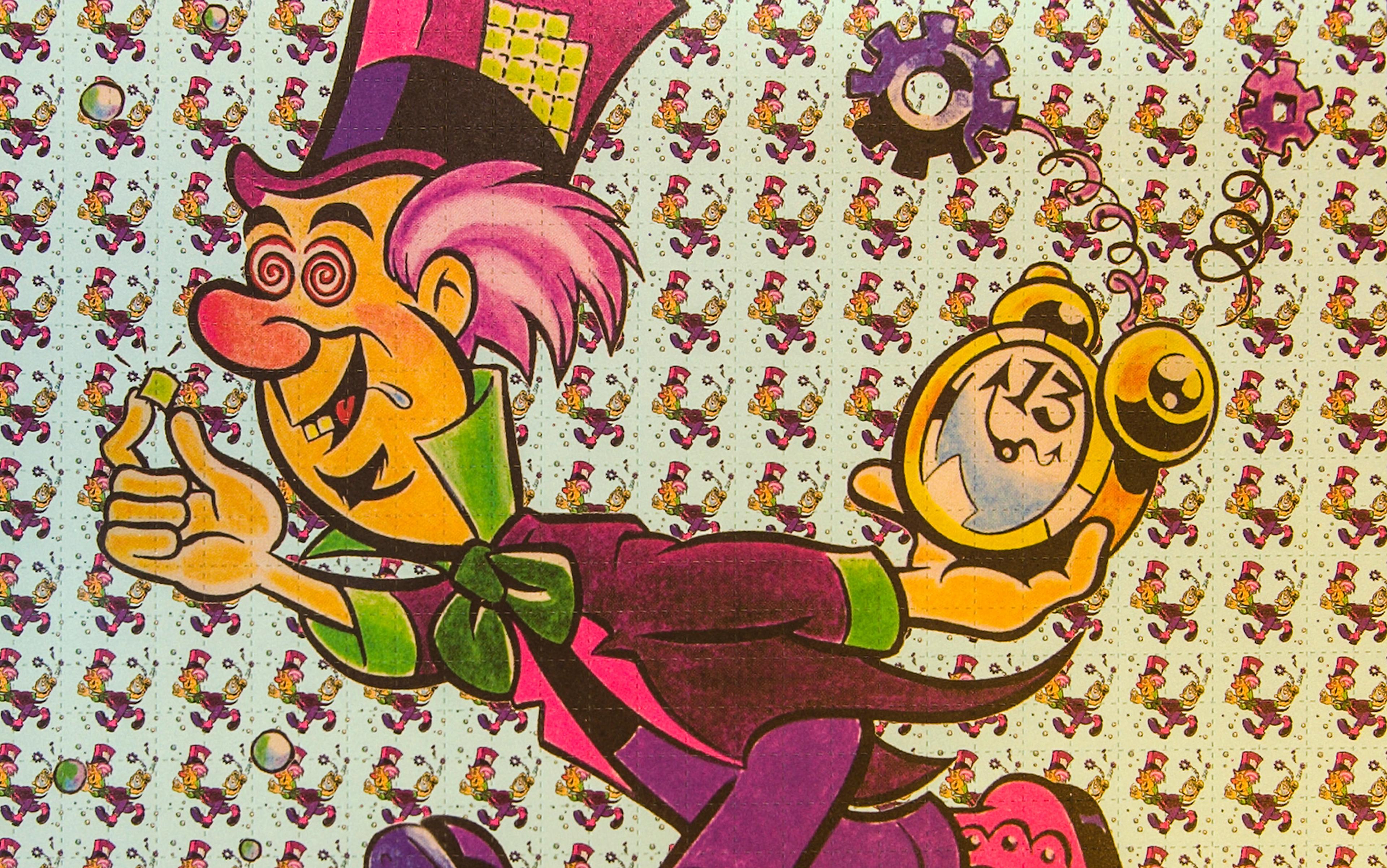

Courtesy the DEA . All other images supplied by the author.

How perforated squares of trippy blotter paper allowed outlaw chemists and wizard-alchemists to dose the world with LSD

by Erik Davis + BIO

First synthesised in 1938 but not tasted until 1943, acid is essentially a creature of the postwar era. As such, it enters the human world alongside an explosion in consumer advertising, the rapid development of electronic and digital media, new polymers, and a host of increasingly cybernetic approaches to the social challenges of control and communication.

For many of its early enthusiasts, acid was like a cosmic transistor radio. As the historian and curator Lars Bang Larsen writes: ‘Hallucinogenic drugs were often understood as new media in the counterculture: only machinic and cybernetic concepts seemed sufficient to address vibrations, intensities, micro-speeds, and other challenges to human perception that occur on the trip.’ LSD seemed to, as Timothy Leary suggested in 1966, ‘tune’ the dials of perception, altering the ratios of the senses, ‘turning on’ their associational pathways and gradients of intensity.

The actor and author Peter Coyote, who was a member of the visionary Diggers collective in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco during the 1960s, wrote that ingesting LSD ‘changed everything, dissolved the boundaries of self, and placed you at some unlocatable point in the midst of a new world, vast beyond imagining, stripped of language, where new skills of communication were required … [because] everything communicated in its own way.’

Similarly, Marshall McLuhan, the pop media prophet of the era, told Playboy that LSD mimes the ‘all-at-onceness and all-at-oneness’ of the new electronic media environment. All this set the stage for a kind of technical mysticism that pervaded LSD culture in the late 20th century, one that framed the drug and its physical manifestations with a luminous sense of immediacy. Alan Watts , commenting on the question of how often to take LSD, turned to another media metaphor, arguing that when you get the message, you hang up the phone. But what if the medium is the message?

O f course, the primary medium is the LSD molecule itself, known as LSD-25, the 25th variation of lysergic acid synthesised by the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann in 1938. But unlike macroscopic drugs such as cannabis, LSD is so small and so powerful that its consumption almost always requires an inert housing – water, tablets, sugar cubes, bits of string or pieces of paper – that transports the drug from manufacturer to tripper. In the law, this vehicle is described as the ‘carrier medium’, an object impregnated with drugs that can be sold, seized, presented as evidence, and dissolved into the hearts, minds and guts of consumers.

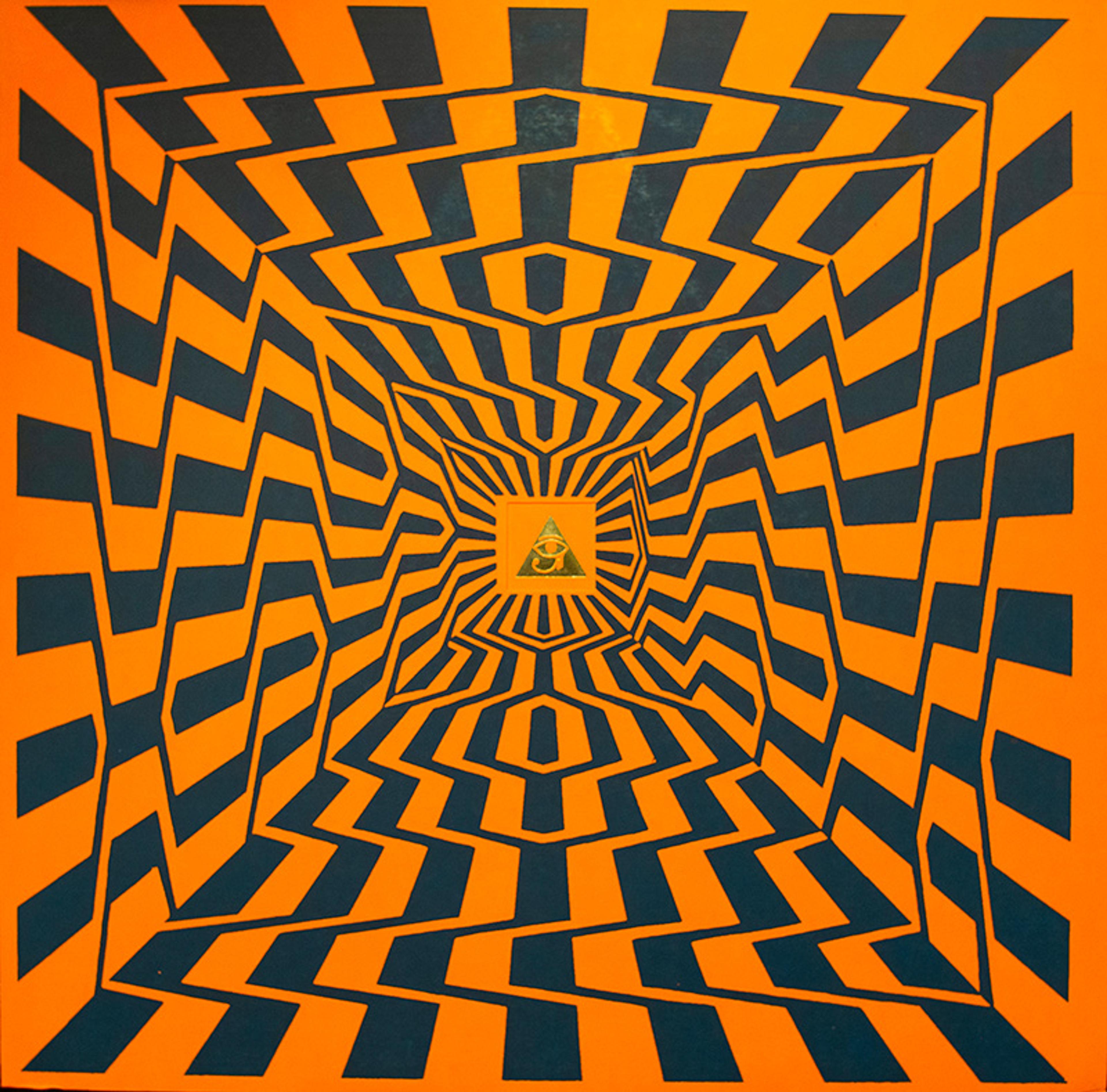

When you print images onto a paper carrier medium, you are adding another layer of mediation to an already loopy transmission. Hence, a meta-medium, a liminal genre of print culture that dissolves the boundaries between a postage stamp, a ticket, a bubble-gum card and the communion host. This makes what is known as blotter a central if barely recognised artefact of psychedelic print culture, alongside rock posters and underground newspapers and comix, but with the extra ouroboric weirdness that it is designed to be ingested, to disappear . Blotter is the most ephemeral of all psychedelic ephemera. It is produced to be eaten, to blur the divide between object and subject, dissolving material signs and molecules into a phenomenological upsurge of sensory, poetic and cognitive immediacy. It is also a medium whose story is tied to LSD’s spiritual decline in the 20th century.

During the blotter age, the quality of the molecule also improved significantly

The early history of LSD has often been framed within the underground as a kind of Edenic narrative. The first crystal versions of lysergic acid represent almost divine substances, praised for their purity , which then become debased by bad chemistry, venal commodification, and the wayward drift of druggy hedonism – a story that itself stands in for the dissipation of the revolutionary energies of the 1960s into the compromises of the 1970s and beyond. In their book Acid Dreams (1985), Martin Lee and Bruce Shlain give us this view, outlining a decline they claim was already well underway by the late 1960s:

So many people were getting high that the identification of drug use with the sharper forms of cultural and political deviance weakened considerably. Instead of being weapons in a generational war, marijuana and LSD often served as pleasure props, accoutrements of the good life that included water beds, tape decks, golden roach clips, and a host of leisure items. High-school kids were popping tabs of acid every weekend as if they were gum-drops. And much of the LSD was like candy – full of additives and impurities. The physical contamination of street acid symbolised what was happening throughout the culture.

This narrative arc is crucial to keep in mind as we unfold the story of blotter. Though LSD was sometimes passed around in the 1960s on actual blotting paper, sheets of perforated (‘perfed’) and printed LSD paper do not come to dominate the acid trade until the late 1970s, reaching a long golden age in the 1980s and ’90s. As such, the rise of blotter mirrors, mediates and challenges the mythopoetic story of LSD’s spiritual decline. For even as LSD lost the millennialist charge of the 1960s, it continued to foster spiritual discovery, social critique, tribal bonds and aesthetic enrichment. During the blotter age, the quality of the molecule also improved significantly, its white sculptured crystals sometimes reaching and maybe surpassing the purity levels of yore. Many of the people who produced and sold this material remained idealists, or at least pragmatic idealists, with a taste for beautiful craft and an outlaw humour reflected in the design of many blotters, which sometimes poked fun at the scene and ironically riffed on the fact that the paper sacraments also served as ‘commercial tokens’.

In these later years, many older LSD users continued to see blotter as a debased medium that bruised and degraded the holy molecule. The truth is that, properly cared for and kept from light and air, humble blotters can hold their punch for quite some time. This persistent potency also gives us a symbolic key for understanding the medium. Blotter hits are signs not of decline but of canny transformation, as idealism gives way to subversion, militancy to mutation, counterculture to subculture. Mediating the profane as much as the sacred, blotter became the central vehicle of LSD’s own weird drift through the post- hippie era.

A s far as we know, LSD’s visionary prowess first emerges in human history as a product of industrial semi-synthesis – an extractive capitalist apparatus that, depending on your characterisation of modern science, suggests at the very least a colonialist exploitation of the organic world as much as a crafted continuity with it. This is important: if LSD represents a sort of magic, it is a magic of the modern West, in all its horror and promethean glory. For all its alchemical resonance, it sprouts from the brow of industrial chemistry, an industry founded on artificial dyes and petroleum products, and it enlists shrinks and spies as some of its earliest shamans.

In 1938, as the now familiar story goes, the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann was working for the Sandoz corporation, a pharmaceutical manufacturer, experimenting with various modifications of lysergic acid. This was the precursor molecule for a number of naturally occurring alkaloids of the ergot fungus, some of which had already proved quite profitable for his employer. LSD-25 was only the 25th in a series of molecules he crafted, and nothing much came of the effort. Five years later, and following what he later described as a ‘peculiar presentiment’, Hofmann decided to resynthesise that unique material. As he neared the end of the process, he felt funny and went home, enjoying a stream of closed-eye visuals.

Returning to work the following Monday, 19 April, Hofmann decided to intentionally test the LSD-25 on himself to root out the weirdness of the previous week. Knowing the potential toxicity of ergot-related compounds, he showed great caution in restricting his initial dose to 250 micrograms (μg) – 750 μg shy of a single milligram (mg). Hofmann knew that the vast majority of drugs and toxins are active at a much higher number of milligrams per kilogram of body weight. For example, the standard dose of MDMA, at least according to the lay therapist Ann Shulgin and her husband, the chemist Alexander ‘Sasha’ Shulgin, and their therapist friends, is around 125 mg; over-the-counter ibuprofen pills start at 100 mg; and potassium cyanide gets lethal around 100 mg, which is 400 times greater than the dose of LSD Hofmann took. But even that smidgin was enough to send the good doctor on a bizarre bicycle ride as he headed home early with an assistant, an event now commemorated every 19 April as Bicycle Day.

LSD, like all psychoactive drugs, is shaped and inflected by the forms it takes in the world before it is ingested

Acid’s capacity to punch above its molecular weight would have a significant impact on the material history of the compound as well as the carrier media that shuttled it around the world and into the bodies of human beings. Because of its almost homeopathic potency, LSD has been distributed on and in an unusually diverse and creative range of media, including blotter’s tiny paper doses – even though they are rarely made of actual blotting paper. This is an unusual carrier medium for drugs, to say the least. A single square of typically sized blotter provides far too little surface area to absorb the amount of material required for most drugs to sufficiently tweak the nervous system. In this sense, acid shapes its own unique media.

The material manifestations of LSD’s carrier media are hardly incidental to the drug’s meaning and import. Even when it’s destined to dissolve and effectively disappear into human bodies, LSD, like all psychoactive drugs, is shaped and inflected by the forms it takes in the world before it is ingested. A bud of cannabis is not a block of hashish is not a chunk of shatter is not an Otterspace Watermelon Delta 8 gummy with 25 mg of THC. These differences go beyond methods of ingestion and metabolic dynamics; they speak to the sorts of meanings and performances that stage and frame the act of consuming things in the first place. In other words, the tangible materiality of psychoactive drugs – as economic, cultural and physical objects – is inevitably compounded with the effects themselves. The bodies of drugs matter .

Roland Barthes makes a similar point about food. While we can subdivide and analyse the things we eat in chemical or nutritional terms, food ‘is also, and at the same time, a system of communication, a body of images, a protocol of usages, situations, and behaviour.’ Food – this actual cannelloni, or paratha, or burrito – is inextricably embedded in matrixes of class, ecology, history, cultural identity and social life – and, in the modern world, of advertising and lifestyle as well. As Barthes puts it: ‘Food sums up and transmits a situation; it constitutes an information; it signifies.’ Psychoactive drugs, a cousin of food, are no different here. Their forms and histories inform, transmit and signify even before you take them.

A cid’s technical genesis as a purified and extraordinarily potent compound, as well as its lack of taste, colour and odour, powerfully shaped the molecule’s material manifestations. LSD is essentially too potent to consume in the ‘raw’ or unmixed form of a crystal powder (though plenty of folks have done so over the decades). When Sandoz began marketing LSD to psychiatrists under the trade name Delysid, they distributed the molecule in two primary forms: jars of sugar-coated tablets that contained 25 μg each, and 1 millilitre ampoules of distilled water containing 100 μg each, which could be swallowed or injected. Sandoz also distributed amber glass containers that held 25 mg (25,000 μg) of pure powder, though these were not, of course, intended for direct consumption. Later industrial sources for LSD, including companies such as Eli Lilly in the United States and Spofa in Czechoslovakia, produced similar formats.

The primary solution to the problems posed by LSD powder, as you might imagine, is water. A massive amount of LSD has been circulated over the decades in liquid form by pharmaceutical companies, major underground producers and low-level dealers and consumers, who might purchase a few hundred low-concentration drops in a small opaque vial or ‘Slim Jim’. Things get more interesting when that liquid later impregnates a further carrier medium, whose plastic possibilities began to flower even before the molecule was rendered illicit. In 1960, the British researcher Michael Hollingshead – who called himself, with some reason, the ‘man who turned on the world’ – got his hands on a gram of Sandoz powder. He mixed it with distilled water and confectioner’s sugar into a gelatinous paste he then transferred to a mayonnaise jar – the same container that served up Leary’s first harrowing dose. A few years later, when Leary and crew returned to the US from Zihuatanejo, Mexico, a stash of liquid LSD spilled in Richard Alpert’s suitcase, which meant that some of the pioneering psychonauts at the legendary Millbrook estate in upstate New York got high by sucking on Alpert’s underwear.

The most signature vernacular carrier for LSD liquid in the first years of the acid boom was the sugar cube. In his autobiography The Road of Excess (1998), the British wild man and Leary crony Brian Barritt describes dosing Tate & Lyle sugar cubes with an eye-dropper full of the acid he had purchased from the brilliant junkie writer Alexander Trocchi. ‘I didn’t know that it could be absorbed through my pores until Mr Cube began jiggling about and acting just like he was stoned out of his mind.’ Mr Cube was the Tate & Lyle logo, a cartoon sugar cube with hands and feet, whose visionary dance through Barritt’s sensorium reminds us that LSD not only unveiled modes of consciousness beyond quotidian modernity but could animate that banal commercial landscape into something mutant and goofy.

Once the tabs hit the street, the colours took on different phenomenological associations

The first well-known ‘brands’ of underground acid were produced by the brilliant and eccentric Augustus Owsley Stanley III, the scion of an illustrious Kentucky family who moved to the San Francisco Bay Area following a stint in the US Air Force. In late 1964, after figuring out how to make methamphetamine, Owsley started working on LSD with Melissa Cargill, a chemistry whiz at the University of California, Berkeley, who may well be responsible for their breakthrough methodology. We don’t know much about Cargill because Owsley played the impresario, earning a reputation for his finicky obsession with chemical purity. Indeed, Owsley’s crystal was reputed to be cleaner than the version made by Sandoz.

Owsley started distributing his acid, often for free, in the spring of 1965. He sifted his powder into gelatine capsules or passed it on as ‘Mother’s Milk’, a liquid that was tinted blue so that distributors could track which sugar cubes they had dosed. These methods were imprecise, and with a material as potent as LSD, careful dosage was key. Exposure to light, which degrades the molecule, was also an issue, as was the ease of counterfeiting capsules. While living in Los Angeles with the underground LSD chemist Tim Scully and the Grateful Dead, Owsley pursued greater quality control, and to that end fashioned 4,000 or so of the first LSD tablets. Using a simple machine to triturate the material, thoroughly mixing it with binders, he then made a paste and spread it on Bakelite sheets to press evenly into tablets. Owsley decided to dye his tabs a purplish blue in order to confuse the drug tests then used by the police, which turned contraband purple if LSD was present. These notoriously powerful tabs, whose 250 μg were chosen in honour of Hofmann’s initial dose, were often sold as Blue Cheer, which also happened to be the name of a popular detergent at the time – making Blue Cheer the first example of an underground LSD preparation that took shape in a parodic funhouse mirror held up to mainstream commodity culture. It would not be the last.

Perhaps Owsley’s most insightful contribution to the history of LSD’s material packaging, however, was a little unintentional experiment in social psychology he performed in 1966. Along with Scully and Cargill, Owsley whipped up a 10-gram batch of pure crystalline LSD powder and divided it into five equal piles, which were then dyed different colours before being buffed with lactose and calcium phosphate to make the powder suitable for tableting. Once the tabs hit the street, where they were often called ‘barrels’, the colours began to take on different phenomenological associations, despite the fact that the LSD was all demonstrably the same material. The red ones were, against type, supposed to be mellow, the greens speedy, and the blues a good blend of the two. According to Scully, one of the colours was even supposed to be particularly ‘spiritual’.

It’s impossible to know if the freaks on the street truly experienced this range of reactions, but given what we know about LSD, not to mention the psychology of brands and placebos, it certainly stands to reason. According to a well-known fMRI study performed at Houston’s Baylor College of Medicine in 2004, participants given a squirt of anonymous cola showed activity in different brain regions (particularly the hippocampus and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) when the brand name for the sugar water was announced; however, this shift registered with Coke but not Pepsi, suggesting a clear neural correlation to brand power. Things grow even more curious with placebos. Numerous studies have shown that the relative effectiveness of placebo pills varies depending on their colour and shape, factors that are of course taken into account in the design and marketing of pharmaceutical preparations.

Acid cranks these priming factors up to 11. In the words of the Czech-born psychiatrist Stanislav Grof, who oversaw more LSD sessions than any other psychiatrist, LSD is, in contrast to typical drugs, a ‘nonspecific amplifier’ rather than a mechanistic agent. And what generally gets amplified, according to Grof, is the psyche, which is highly sensitive to expectations, cultural narratives and external suggestions. This sensitivity undergirds the well-known psychedelic principle of ‘set and setting’, which, as the drug historian Ido Hartogsohn explains , divides the nonpharmacological agents of drug experience into ‘set (personality, preparation, expectation and intention of the person having the experience) and setting (the physical, social and cultural environment in which the experience takes place).’ Even before Leary made this phrase a psychedelic mantra, psychedelic researchers recognised that the mindset of the tripper, coupled with specific features and qualities of the trip room, played an often significant role in the experience.

The important point here is that blotter, like all carrier media, directly contributes to the set and setting. Given this psychic sensitivity to material and symbolic conditions, the physical packaging of LSD will impress itself to some degree upon the roiling incorporeal slipstream of the trip. Fat blue LSD tablets or plain sugar cubes or orange-coloured blotters are not ‘the same’ drug, even if their dosages and source material are identical. The printed images of blotter add a whole other dimension of priming through their sometimes-potent signs. With acid, again, the medium really is the message.

T he most likely candidate for the first printed blotter, Mr Natural is one of a number of LSD sheets that appeared in the 1970s and ’80s featuring R Crumb’s funny, free-thinking guru character. The Midwest Research Institute’s Drug Atlas includes an example seized in July 1971 – an orange four-way, costing $2.50 – that shows the disreputable saint pointing to the sky (identified somewhat confusingly in the Blotter Index as ‘Mr Natural #2’). ‘Sold as LSD,’ the Atlas reads; ‘reportedly gives a good experience.’

Though they may have been circulating in the UK since the 1960s, blotters formally appeared there by at least 1974, when the Freek Press at the Windsor Free Fest reported the presence of orange and white sheets. A year later, another blotter, this one ‘marked with a strawberry’ and ‘weak or strong depending on the strength of your head’, was gobbled at the Watchfield Free Festival. For the most part, however, blotter in these earlier years, whether in the US or the UK, rarely included any ‘marks’ at all. But soon, blotters would be covered in artwork, a psychedelic echo of modern art’s mutation from high abstraction to pop.

One of the most celebrated blotters of the era featured Mickey Mouse in his Fantasia guise as the Sorcerer’s Apprentice. These sharply designed four-colour sheets came perfed into 100 units, each featuring their own budding rodent wizard. This was charming enough, but if you bought a gram, you’d get a red lacquered box that was also affixed with an image of Mickey, now surrounded by 17 gold stars. Inside lay a bundle of 40 sheets wrapped in a container of gold foil affixed with another image of the mouse, this time accompanied by the word ‘Sandoz’ – alerting the discerning buyer that the batch was most likely made from LSD synthesised by the original Swiss sorcerers.

Blotters are pleasant to handle: potent graphic fetishes that feature the gentle crispness of a thin matzah

Blotter was and is cheap, rarely exceeding $2.50 a hit or so, which meant that it actually offered less of a markup per unit that either tablets or gels. What disposed distributors to blotter was volume, ease of production and concealment, and speed of dissemination. Sheets are easy to transport, easy to mail, and easy to hide. When the notorious pranksters in the Tibetan Ukrainian Mountain Troupe descended on British festivals in the 1980s, they smuggled in sheets of acid-impregnated green cartridge paper that, because it resembled gasket paper, was stashed in toolboxes and laminated on-site with illustrated fascia brought in separately. On the production side, blotter offered a number of advantages over tableting. Printing, and especially silk screening, used far less arcane and suspicious technology, and because the sheets were dipped after the fact – ‘asynchronously’, we would say today – blotter makers could maintain some distance from the patently criminal production and distribution of the molecule itself. Blotters also weighed considerably less than tablets, though one of the most common reasons given for blotter’s ascent – the passage of so-called carrier weight laws in the 1980s – doesn’t really hold water.

Illustrated blotter is also fun. Whether circulated on the scale of multiple sheets, sometimes called ‘pages’, or as hits or ‘10-strips’ swapped in a parking lot, blotters are pleasant to handle: potent graphic fetishes that feature the gentle crispness of a thin matzah. Like chocolate bars with their grid of grooves, blotter asks to be fondled, torn and crumbled, nibbled. But like coins or stamps or show flyers, it also has the feel of ephemera you might want to hold onto for a while. As a crucial but underrecognised vector of underground print culture, illustrated blotter not only promises individual transport, but affirms participation in a marginal and collective demimonde that was and is sustained partly through an ongoing publishing effort, one that relies on print’s capacity to build fanciful alternative worlds with mechanically reproduced signs. When Mr Natural waltzed across the first printed blotter, he offered the ironic cartoon promise that the acid revelation just keeps on truckin’, a promise you could participate in by eating the underground comix panel rather than just looking at it.

Both literally and figuratively, blotter serves as an avatar of LSD-25 (though it bears repeating that today’s black-market blotter is often dosed with other psychoactive molecules). This makes blotter a particularly interesting lens through which to view today’s much-hyped ‘ psychedelic renaissance ’. Over recent decades, a perfect storm of clinical researchers, psychotherapists, venture capitalists, journalists, wellness entrepreneurs and decriminalisation activists has radically transformed the medical, cultural and even legal profile of psychedelics in the US. This process is inconceivable without the historical catalyst of LSD, which is far and away the most influential psychedelic in modern postwar history, and one that remains widely available and widely consumed. But LSD has been largely marginalised in the contemporary discourse around the promise of psychedelics, a process that is reflected in the strange and even uncanny status of blotter art.

There remains something suspect about blotter, a stain that is both a blessing and a curse. As the blotter producer Matthew Rick, who started selling sheets as non-dipped ‘art’ collectables at festivals in 1998, puts it: ‘[B]lotter is the last underground art form that’s going to stay underground, simply because you’re creating something that looks like and functions like a felony.’ In other words, blotter is ontologically illicit; it is, as Rick says, ‘drug paraphernalia by its very existence’. So even as blotter continues to stoke and reflect consumer and collector desire in the 21st century, there is something irredeemably tainted about it, as if the perforations that define the form puncture whatever cultural legitimacy it might gain. ‘Pop culture can take the edge off of anything eventually, but you can’t take the edge off of this stuff,’ says Rick. ‘It doesn’t matter how far down the rabbit hole you go. Disney is just not going to make a blotter edition.’

This piece is from Blotter: The Untold Story of an Acid Medium (2024) by Erik Davis, published by MIT Press.

Design and fashion

Sitting on the art

Given its intimacy with the body and deep play on form and function, furniture is a ripely ambiguous artform of its own

Emma Crichton Miller

Learning to be happier

In order to help improve my students’ mental health, I offered a course on the science of happiness. It worked – but why?

The environment

We need to find a way for human societies to prosper while the planet heals. So far we can’t even think clearly about it

Ville Lähde

Archaeology

Why make art in the dark?

New research transports us back to the shadowy firelight of ancient caves, imagining the minds and feelings of the artists

Izzy Wisher

Stories and literature

Do liberal arts liberate?

In Jack London’s novel, Martin Eden personifies debates still raging over the role and purpose of education in American life

Politics and government

India and indigeneity

In a country of such extraordinary diversity, the UN definition of ‘indigenous’ does little more than fuel ethnic violence

Dikshit Sarma Bhagabati

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Book Review: Memoirist Lilly Dancyger’s penetrating essays explore the power of female friendships

This cover image released by Dial Press shows “First Love” by Lilly Dancyger. (Dial Press via AP)

- Copy Link copied

Who means more to you — your friends or your lovers? In a vivid, thoughtful and nuanced collection of essays, Lilly Dancyger explores the powerful role that female friendships played in her chaotic upbringing marked by her parents’ heroin use and her father’s untimely death when she was only 12.

“First Love: Essays on Friendship” begins with a beautiful paean to her cousin Sabina, who was raped and murdered at age 20 on her way home from a club. As little kids, their older relatives used to call them Snow White and Rose Red after the Grimm’s fairy tale, “two sisters who are not rivals or foils, but simply love each other.”

That simple, uncomplicated love would become the template for a series of subsequent relationships with girls and women that helped her survive her self-destructive adolescence and provided unconditional support as she scrambled to create a new identity as a “hypercompetent” writer, teacher and editor. “It’s true that I’ve never been satisfied with friendships that stay on the surface. That my friends are my family, my truest beloveds, each relationship a world of its own,” she writes in the title essay “First Love.”

The collection stands out not just for its elegant, unadorned writing but also for the way she effortlessly pivots between personal history and spot-on cultural criticism that both comments on and critiques the way that girls and women have been portrayed — and have portrayed themselves — in the media, including on online platforms like Tumblr and Instagram.

For instance, she examines the 1994 Peter Jackson film, “Heavenly Creatures,” based on the true story of two teenage girls who bludgeoned to death one of their mothers. And in the essay “Sad Girls,” about the suicide of a close friend, she analyzes the allure of self-destructive figures like Sylvia Plath and Janis Joplin to a certain type of teen, including herself, who wallows in sadness and wants to make sure “the world knew we were in pain.”

In the last essay, “On Murder Memoirs,” Dancyger considers the runaway popularity of true crime stories as she tries to explain her decision not to attend the trial of the man charged with killing her cousin — even though she was trained as a journalist and wrote a well-regarded book about her late father that relied on investigative reporting. “When I finally sat down to write about Sabina, the story that came out was not about murder at all,” she says. “It was a love story.”

Readers can be thankful that it did.

AP book reviews: https://apnews.com/hub/book-reviews

- Get Alma in Your Inbox

What Does It Feel Like To Be Jewish on Campus Right Now?

Nine jewish students, representing a wide range of perspectives, tell us how they've experienced this moment of campus protests surrounding the israel-hamas war..

For the students witnessing the protests, participating in the protests (or counter-protests), talking about the protests with friends and in classes, feeling fearful of the protests, feeling empowered by the protests, or simply trying to study for finals while all this happens around them, this moment is not just something to study in text books or pontificate about over coffee and the newspaper. This is their lived realities.

As a publication and online community that aims to highlight and amplify a diversity of young Jewish voices, we wanted to hear directly from people who were living on college campuses during this time.

And so, last week we put out a call on our platform asking students: What does it feel like to be Jewish on campus right now?

And wow, did we get responses! We anticipated receiving a few essays, and thought we might publish a handful of them. Instead, we received nearly 100 essays, and here, we are sharing nine of those with you. These essays are all written by Jewish students attending colleges in the United States. They represent a really wide range of perspectives and experiences. And we hope you’ll read all of them. Our goal is not to speak for every single student, but rather to allow each student featured here to speak for themselves. Perhaps you’ll see something that resonates for you; perhaps you’ll see something that makes you mad. Ideally, you’ll find something that sparks a moment of self-recognition or understanding where you didn’t expect it.

Read on to hear from nine college students about what it feels like to be Jewish on campus in 2024.

“I am looking for a community, but I do not fit anywhere.” — Molly Greenwold from Newton, MA; Barnard College, Class of 2026

“I have fought for both Zionist and anti-Zionist students to feel safe.” — Irene Raich from Fayetteville, Arkansas; Yale University, Class of 2027

“Living in fear on campus has become a daily battle.” — Kalie Fishman from Farmington Hills, MI; University of Michigan School of Social Work, Class of 2024

“I was arrested on the first night of Passover at the encampment on my college campus.” — Kira Carleton from Brooklyn, NY; NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, Master’s Student, Class of 2025

“Would people treat me differently if they knew I am Israeli?” — Yasmine Abouzaglo from Dallas, TX; Columbia University, Class of 2027

“I am not a Jew with trembling knees.” — Sophie Friedberg from Los Angeles, CA; University of Wisconsin-Madison, Class of 2024

“For the first time since October 7, I don’t feel so powerless.” — Adrien Braun; Trinity College, Class of 2026

“Maybe if I weren’t grieving the massacre of my community, I would feel differently.” — Devorah Klein from Kansas City, MO; University of Kansas, Class of 2024

“Most of the time, I stay silent.” — Gabriela Marquis from Spokane, WA; Gonzaga University, Class of 2024

For Tallulah Haddon, Filming ‘Tattooist of Auschwitz’ Was Strange and Spiritual

The multidisciplinary artist and actor chatted with hey alma about making queer jewish art, laughter as freedom and cannibalism..

This New Digital Series Is a Love Letter to Mexican-Jewish Culture

In "eitan explores: mexico city," celebrity chef eitan bernath reminds us that jewish food and flavor spans wherever jews are in the world..

Finding a Way To Make the Jewish Prayer for Healing Work for Me

As someone with a chronic illness, i used to struggle with the idea of refuah shleimah, or "complete healing." now, i've made peace with it..

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

You may also want to consult these sites to search for other theses: Google Scholar; NDLTD, the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations.NDLTD provides information and a search engine for electronic theses and dissertations (ETDs), whether they are open access or not. Proquest Theses and Dissertations (PQDT), a database of dissertations and theses, whether they were published ...

EBSCO Open Dissertations is a collaboration between EBSCO and BiblioLabs to increase traffic and discoverability of ETD research. You can join the movement and add your theses and dissertations to the database, making them freely available to researchers everywhere while increasing traffic to your institutional repository.

The Harvard University Archives' collection of theses, dissertations, and prize papers document the wide range of academic research undertaken by Harvard students over the course of the University's history.. Beyond their value as pieces of original research, these collections document the history of American higher education, chronicling both the growth of Harvard as a major research ...

Provides free access to thousands of dissertation and thesis abstracts from universities around the world, and links to full text when freely available. PQDT Open This link opens in a new window Proquest's portal to their Dissertations and Theses that are freely available on the web. See the database Dissertations and Theses for more options ...

Help you achieve your academic goals. Whether we're proofreading and editing, checking for plagiarism or AI content, generating citations, or writing useful Knowledge Base articles, our aim is to support students on their journey to become better academic writers. We believe that every student should have the right tools for academic success.

Free access to millions of research papers for everyone. OA.mg is a search engine for academic papers. Whether you are looking for a specific paper, or for research from a field, or all of an author's works - OA.mg is the place to find it. Universities and researchers funded by the public publish their research in papers, but where do we ...

Prize-Winning Thesis and Dissertation Examples. Published on September 9, 2022 by Tegan George.Revised on July 18, 2023. It can be difficult to know where to start when writing your thesis or dissertation.One way to come up with some ideas or maybe even combat writer's block is to check out previous work done by other students on a similar thesis or dissertation topic to yours.

Revised on April 16, 2024. A thesis is a type of research paper based on your original research. It is usually submitted as the final step of a master's program or a capstone to a bachelor's degree. Writing a thesis can be a daunting experience. Other than a dissertation, it is one of the longest pieces of writing students typically complete.

The Center for Research Libraries ' Dissertations database includes many non-US theses. WorldCat describes many masters' & PhD theses. Use "Advanced Search" and limit to subtype "thesis/dissertation." No full text; it just tells you what libraries have reported having copies. There are several excellent guides out there with international ...

Step 1: find. I used to find new papers by aimlessly scrolling through science Twitter. But because I often got distracted by irrelevant tweets, that wasn't very efficient. I also signed up for ...

Thesis. Your thesis is the central claim in your essay—your main insight or idea about your source or topic. Your thesis should appear early in an academic essay, followed by a logically constructed argument that supports this central claim. A strong thesis is arguable, which means a thoughtful reader could disagree with it and therefore ...

one or two sentence summary of the paper. deeper, more extensive outline of the main points of the paper, including for example assumptions made, arguments presented, data analyzed, and conclusions drawn. any limitations or extensions you see for the ideas in the paper. your opinion of the paper; primarily, the quality of the ideas and its ...

Keep your thesis prominent in your introduction. A good, standard place for your thesis statement is at the end of an introductory paragraph, especially in shorter (5-15 page) essays. Readers are used to finding theses there, so they automatically pay more attention when they read the last sentence of your introduction.

Over the last 80 years, ProQuest has built the world's most comprehensive and renowned dissertations program. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (PQDT Global), continues to grow its repository of 5 million graduate works each year, thanks to the continued contribution from the world's universities, creating an ever-growing resource of emerging research to fuel innovation and new insights.

Researchers must read papers for several reasons: to re-view them for a conference or a class, to keep current in their eld, or for a literature survey of a new eld. A typi-cal researcher will likely spend hundreds of hours every year reading papers. Learning to e ciently read a paper is a critical but rarely taught skill.

To help guide your reader, end your introduction with an outline of the structure of the thesis or dissertation to follow. Share a brief summary of each chapter, clearly showing how each contributes to your central aims. However, be careful to keep this overview concise: 1-2 sentences should be enough. Note.

Read a thesis. A good way to consolidate your knowledge about writing a thesis is to read a thesis. The Theses Library Guide provides information on locating and accessing theses produced by Monash University as well as other institutions. Have a look for recently completed theses in your discipline, or ask your supervisor to suggest some ...

The Electronic Theses Online System (EThOS) offers free access to the full text of UK theses. EThOS offers a one stop online shop providing free access to UK theses. EThOS digitizes theses on request into PDF format, this may require payment. EThOS is managed by the British Library in partnership with a number of UK universities.