- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

5 Unethical Medical Experiments Brought Out of the Shadows of History

Prisoners and other vulnerable populations often bore the brunt of unethical medical experimentation..

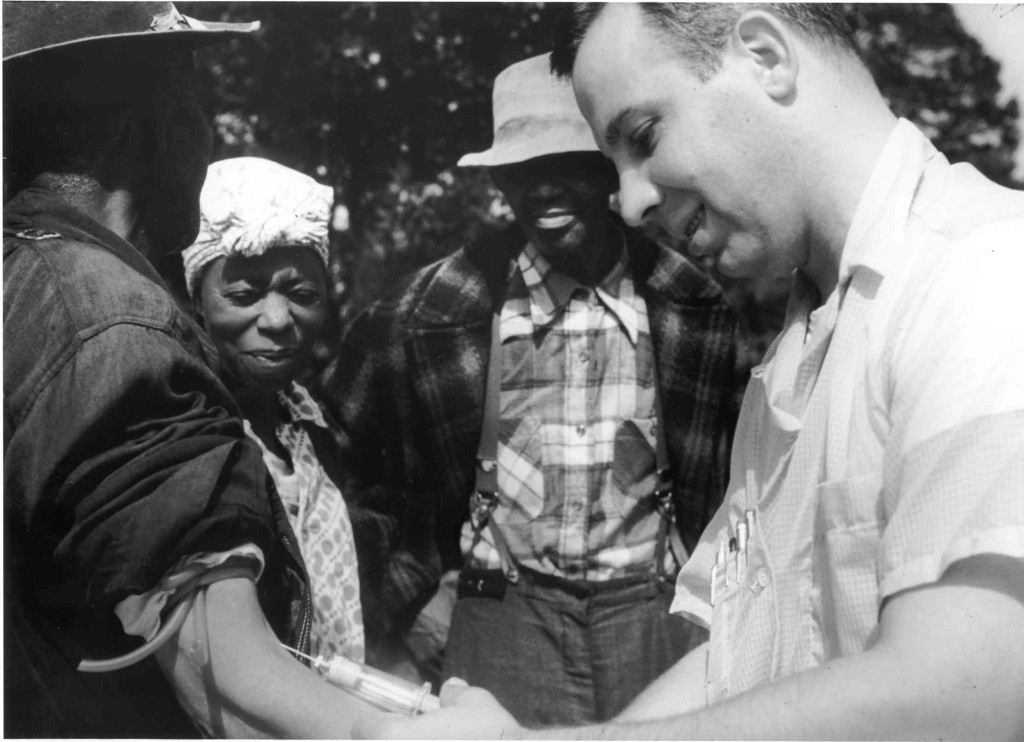

Most people are aware of some of the heinous medical experiments of the past that violated human rights. Participation in these studies was either forced or coerced under false pretenses. Some of the most notorious examples include the experiments by the Nazis, the Tuskegee syphilis study, the Stanford Prison Experiment, and the CIA’s LSD studies.

But there are many other lesser-known experiments on vulnerable populations that have flown under the radar. Study subjects often didn’t — or couldn’t — give consent. Sometimes they were lured into participating with a promise of improved health or a small amount of compensation. Other times, details about the experiment were disclosed but the extent of risks involved weren’t.

This perhaps isn’t surprising, as doctors who conducted these experiments were representative of prevailing attitudes at the time of their work. But unfortunately, even after informed consent was introduced in the 1950s , disregard for the rights of certain populations continued. Some of these researchers’ work did result in scientific advances — but they came at the expense of harmful and painful procedures on unknowing subjects.

Here are five medical experiments of the past that you probably haven’t heard about. They illustrate just how far the ethical and legal guidepost, which emphasizes respect for human dignity above all else, has moved.

The Prison Doctor Who Did Testicular Transplants

From 1913 to 1951, eugenicist Leo Stanley was the chief surgeon at San Quentin State Prison, California’s oldest correctional institution. After performing vasectomies on prisoners, whom he recruited through promises of improved health and vigor, Stanley turned his attention to the emerging field of endocrinology, which involves the study of certain glands and the hormones they regulate. He believed the effects of aging and decreased hormones contributed to criminality, weak morality, and poor physical attributes. Transplanting the testicles of younger men into those who were older would restore masculinity, he thought.

Stanley began by using the testicles of executed prisoners — but he ran into a supply shortage. He solved this by using the testicles of animals, including goats and deer. At first, he physically implanted the testicles directly into the inmates. But that had complications, so he switched to a new plan: He ground up the animal testicles into a paste, which he injected into prisoners’ abdomens. By the end of his time at San Quentin, Stanley did an estimated 10,000 testicular procedures .

The Oncologist Who Injected Cancer Cells Into Patients and Prisoners

During the 1950s and 1960s, Sloan-Kettering Institute oncologist Chester Southam conducted research to learn how people’s immune systems would react when exposed to cancer cells. In order to find out, he injected live HeLa cancer cells into patients, generally without their permission. When patient consent was given, details around the true nature of the experiment were often kept secret. Southam first experimented on terminally ill cancer patients, to whom he had easy access. The result of the injection was the growth of cancerous nodules , which led to metastasis in one person.

Next, Southam experimented on healthy subjects , which he felt would yield more accurate results. He recruited prisoners, and, perhaps not surprisingly, their healthier immune systems responded better than those of cancer patients. Eventually, Southam returned to infecting the sick and arranged to have patients at the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in Brooklyn, NY, injected with HeLa cells. But this time, there was resistance. Three doctors who were asked to participate in the experiment refused, resigned, and went public.

The scandalous newspaper headlines shocked the public, and legal proceedings were initiated against Southern. Some in the scientific and medical community condemned his experiments, while others supported him. Initially, Southam’s medical license was suspended for one year, but it was then reduced to a probation. His career continued to be illustrious, and he was subsequently elected president of the American Association for Cancer Research.

The Aptly Named ‘Monster Study’

Pioneering speech pathologist Wendell Johnson suffered from severe stuttering that began early in his childhood. His own experience motivated his focus on finding the cause, and hopefully a cure, for stuttering. He theorized that stuttering in children could be impacted by external factors, such as negative reinforcement. In 1939, under Johnson’s supervision, graduate student Mary Tudor conducted a stuttering experiment, using 22 children at an Iowa orphanage. Half received positive reinforcement. But the other half were ridiculed and criticized for their speech, whether or not they actually stuttered. This resulted in a worsening of speech issues for the children who were given negative feedback.

The study was never published due to the multitude of ethical violations. According to The Washington Post , Tudor was remorseful about the damage caused by the experiment and returned to the orphanage to help the children with their speech. Despite his ethical mistakes, the Wendell Johnson Speech and Hearing Clinic at the University of Iowa bears Johnson's name and is a nod to his contributions to the field.

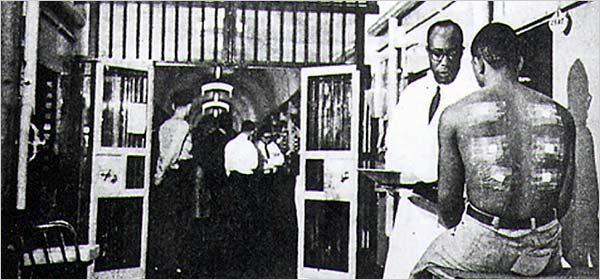

The Dermatologist Who Used Prisoners As Guinea Pigs

One of the biggest breakthroughs in dermatology was the invention of Retin-A, a cream that can treat sun damage, wrinkles, and other skin conditions. Its success led to fortune and fame for co-inventor Albert Kligman, a dermatologist at the University of Pennsylvania . But Kligman is also known for his nefarious dermatology experiments on prisoners that began in 1951 and continued for around 20 years. He conducted his research on behalf of companies including DuPont and Johnson & Johnson.

Kligman’s work often left prisoners with pain and scars as he used them as study subjects in wound healing and exposed them to deodorants, foot powders, and more for chemical and cosmetic companies. Dow once enlisted Kligman to study the effects of dioxin, a chemical in Agent Orange, on 75 inmates at Pennsylvania's Holmesburg Prison. The prisoners were paid a small amount for their participation but were not told about the potential side effects.

In the University of Pennsylvania’s journal, Almanac , Kligman’s obituary focused on his medical advancements, awards, and philanthropy. There was no acknowledgement of his prison experiments. However, it did mention that as a “giant in the field,” he “also experienced his fair share of controversy.”

The Endocrinologist Who Irradiated Prisoners

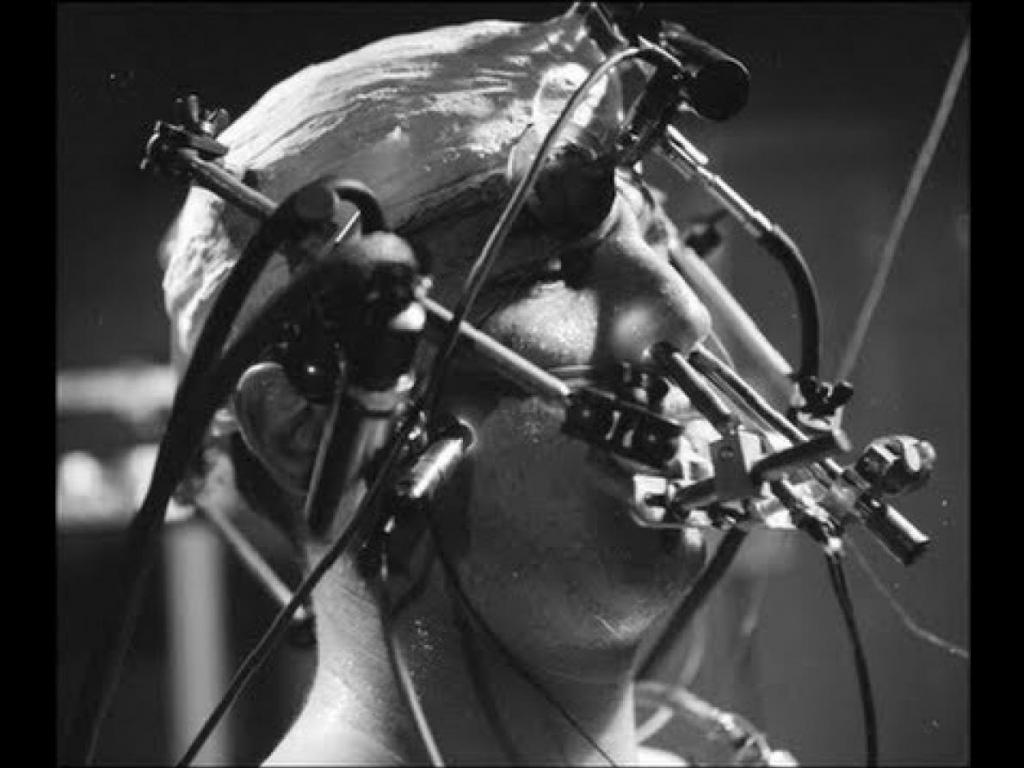

When the Atomic Energy Commission wanted to know how radiation affected male reproductive function, they looked to endocrinologist Carl Heller . In a study involving Oregon State Penitentiary prisoners between 1963 and 1973, Heller designed a contraption that would radiate their testicles at varying amounts to see what effect it had, particularly on sperm production. The prisoners also were subjected to repeated biopsies and were required to undergo vasectomies once the experiments concluded.

Although study participants were paid, it raised ethical issues about the potential coercive nature of financial compensation to prison populations. The prisoners were informed about the risks of skin burns, but likely were not told about the possibility of significant pain, inflammation, and the small risk of testicular cancer.

- personal health

- behavior & society

Already a subscriber?

Register or Log In

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

BREAKING: Angela Alsobrooks defeats self-funder David Trone in the Maryland Democratic Senate primary, NBC News projects

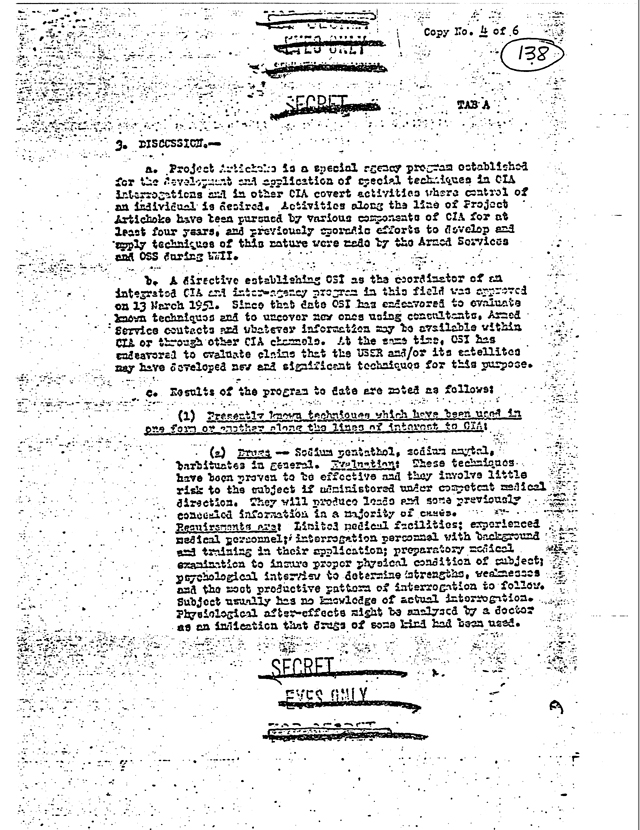

Ugly past of U.S. human experiments uncovered

Shocking as it may seem, U.S. government doctors once thought it was fine to experiment on disabled people and prison inmates. Such experiments included giving hepatitis to mental patients in Connecticut, squirting a pandemic flu virus up the noses of prisoners in Maryland, and injecting cancer cells into chronically ill people at a New York hospital.

Much of this horrific history is 40 to 80 years old, but it is the backdrop for a meeting in Washington this week by a presidential bioethics commission. The meeting was triggered by the government's apology last fall for federal doctors infecting prisoners and mental patients in Guatemala with syphilis 65 years ago.

U.S. officials also acknowledged there had been dozens of similar experiments in the United States — studies that often involved making healthy people sick.

An exhaustive review by The Associated Press of medical journal reports and decades-old press clippings found more than 40 such studies. At best, these were a search for lifesaving treatments; at worst, some amounted to curiosity-satisfying experiments that hurt people but provided no useful results.

Inevitably, they will be compared to the well-known Tuskegee syphilis study. In that episode, U.S. health officials tracked 600 black men in Alabama who already had syphilis but didn't give them adequate treatment even after penicillin became available.

These studies were worse in at least one respect — they violated the concept of "first do no harm," a fundamental medical principle that stretches back centuries.

"When you give somebody a disease — even by the standards of their time — you really cross the key ethical norm of the profession," said Arthur Caplan, director of the University of Pennsylvania's Center for Bioethics.

Attitude similar to Nazi experiments Some of these studies, mostly from the 1940s to the '60s, apparently were never covered by news media. Others were reported at the time, but the focus was on the promise of enduring new cures, while glossing over how test subjects were treated.

Attitudes about medical research were different then. Infectious diseases killed many more people years ago, and doctors worked urgently to invent and test cures. Many prominent researchers felt it was legitimate to experiment on people who did not have full rights in society — people like prisoners, mental patients, poor blacks. It was an attitude in some ways similar to that of Nazi doctors experimenting on Jews.

"There was definitely a sense — that we don't have today — that sacrifice for the nation was important," said Laura Stark, a Wesleyan University assistant professor of science in society, who is writing a book about past federal medical experiments.

The AP review of past research found:

- A federally funded study begun in 1942 injected experimental flu vaccine in male patients at a state insane asylum in Ypsilanti, Mich., then exposed them to flu several months later. It was co-authored by Dr. Jonas Salk, who a decade later would become famous as inventor of the polio vaccine.

Some of the men weren't able to describe their symptoms, raising serious questions about how well they understood what was being done to them. One newspaper account mentioned the test subjects were "senile and debilitated." Then it quickly moved on to the promising results.

- In federally funded studies in the 1940s, noted researcher Dr. W. Paul Havens Jr. exposed men to hepatitis in a series of experiments, including one using patients from mental institutions in Middletown and Norwich, Conn. Havens, a World Health Organization expert on viral diseases, was one of the first scientists to differentiate types of hepatitis and their causes.

A search of various news archives found no mention of the mental patients study, which made eight healthy men ill but broke no new ground in understanding the disease.

- Researchers in the mid-1940s studied the transmission of a deadly stomach bug by having young men swallow unfiltered stool suspension. The study was conducted at the New York State Vocational Institution, a reformatory prison in West Coxsackie. The point was to see how well the disease spread that way as compared to spraying the germs and having test subjects breathe it. Swallowing it was a more effective way to spread the disease, the researchers concluded. The study doesn't explain if the men were rewarded for this awful task.

- A University of Minnesota study in the late 1940s injected 11 public service employee volunteers with malaria, then starved them for five days. Some were also subjected to hard labor, and those men lost an average of 14 pounds. They were treated for malarial fevers with quinine sulfate. One of the authors was Ancel Keys, a noted dietary scientist who developed K-rations for the military and the Mediterranean diet for the public. But a search of various news archives found no mention of the study.

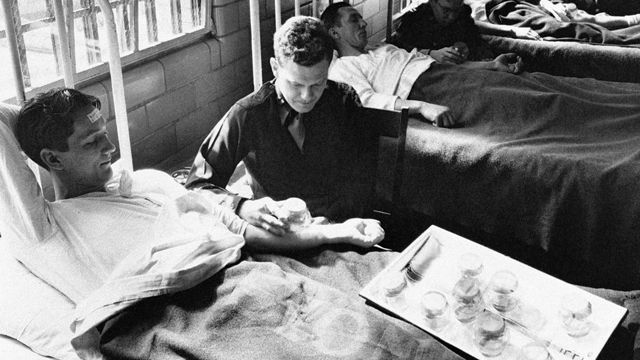

- For a study in 1957, when the Asian flu pandemic was spreading, federal researchers sprayed the virus in the noses of 23 inmates at Patuxent prison in Jessup, Md., to compare their reactions to those of 32 virus-exposed inmates who had been given a new vaccine.

- Government researchers in the 1950s tried to infect about two dozen volunteering prison inmates with gonorrhea using two different methods in an experiment at a federal penitentiary in Atlanta. The bacteria was pumped directly into the urinary tract through the penis, according to their paper.

The men quickly developed the disease, but the researchers noted this method wasn't comparable to how men normally got infected — by having sex with an infected partner. The men were later treated with antibiotics. The study was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, but there was no mention of it in various news archives.

Though people in the studies were usually described as volunteers, historians and ethicists have questioned how well these people understood what was to be done to them and why, or whether they were coerced.

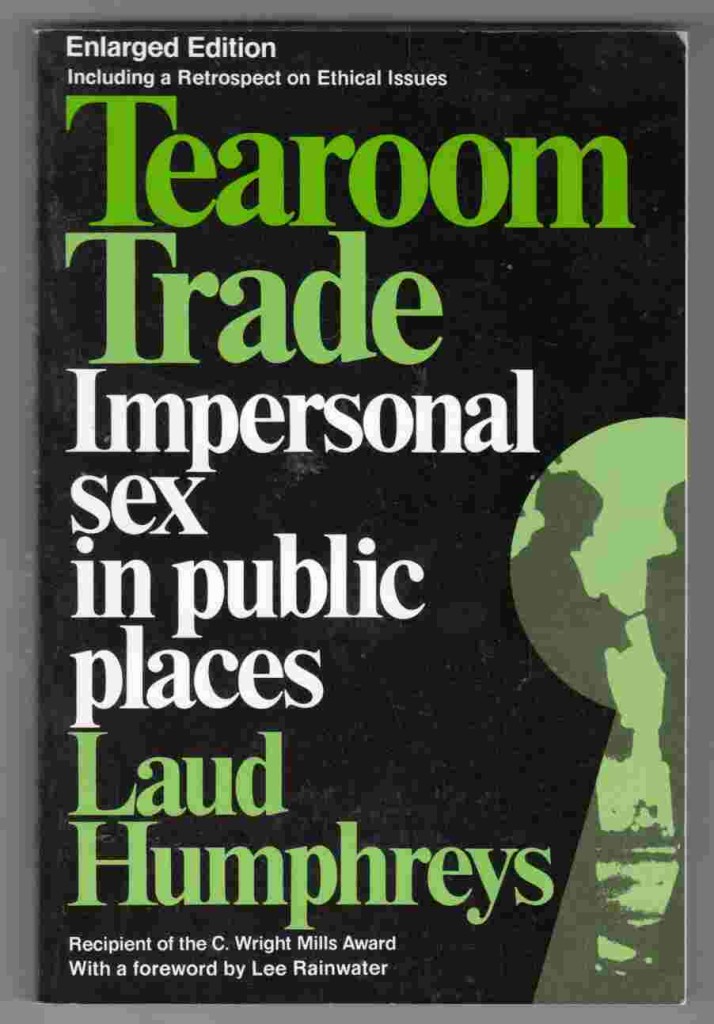

Victims for science Prisoners have long been victimized for the sake of science. In 1915, the U.S. government's Dr. Joseph Goldberger — today remembered as a public health hero — recruited Mississippi inmates to go on special rations to prove his theory that the painful illness pellagra was caused by a dietary deficiency. (The men were offered pardons for their participation.)

But studies using prisoners were uncommon in the first few decades of the 20th century, and usually performed by researchers considered eccentric even by the standards of the day. One was Dr. L.L. Stanley, resident physician at San Quentin prison in California, who around 1920 attempted to treat older, "devitalized men" by implanting in them testicles from livestock and from recently executed convicts.

Newspapers wrote about Stanley's experiments, but the lack of outrage is striking.

"Enter San Quentin penitentiary in the role of the Fountain of Youth — an institution where the years are made to roll back for men of failing mentality and vitality and where the spring is restored to the step, wit to the brain, vigor to the muscles and ambition to the spirit. All this has been done, is being done ... by a surgeon with a scalpel," began one rosy report published in November 1919 in The Washington Post.

Around the time of World War II, prisoners were enlisted to help the war effort by taking part in studies that could help the troops. For example, a series of malaria studies at Stateville Penitentiary in Illinois and two other prisons was designed to test antimalarial drugs that could help soldiers fighting in the Pacific.

It was at about this time that prosecution of Nazi doctors in 1947 led to the "Nuremberg Code," a set of international rules to protect human test subjects. Many U.S. doctors essentially ignored them, arguing that they applied to Nazi atrocities — not to American medicine.

The late 1940s and 1950s saw huge growth in the U.S. pharmaceutical and health care industries, accompanied by a boom in prisoner experiments funded by both the government and corporations. By the 1960s, at least half the states allowed prisoners to be used as medical guinea pigs.

But two studies in the 1960s proved to be turning points in the public's attitude toward the way test subjects were treated.

The first came to light in 1963. Researchers injected cancer cells into 19 old and debilitated patients at a Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in the New York borough of Brooklyn to see if their bodies would reject them.

The hospital director said the patients were not told they were being injected with cancer cells because there was no need — the cells were deemed harmless. But the experiment upset a lawyer named William Hyman who sat on the hospital's board of directors. The state investigated, and the hospital ultimately said any such experiments would require the patient's written consent.

At nearby Staten Island, from 1963 to 1966, a controversial medical study was conducted at the Willowbrook State School for children with mental retardation. The children were intentionally given hepatitis orally and by injection to see if they could then be cured with gamma globulin.

Those two studies — along with the Tuskegee experiment revealed in 1972 — proved to be a "holy trinity" that sparked extensive and critical media coverage and public disgust, said Susan Reverby, the Wellesley College historian who first discovered records of the syphilis study in Guatemala.

'My back is on fire!' By the early 1970s, even experiments involving prisoners were considered scandalous. In widely covered congressional hearings in 1973, pharmaceutical industry officials acknowledged they were using prisoners for testing because they were cheaper than chimpanzees.

Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia made extensive use of inmates for medical experiments. Some of the victims are still around to talk about it. Edward "Yusef" Anthony, featured in a book about the studies, says he agreed to have a layer of skin peeled off his back, which was coated with searing chemicals to test a drug. He did that for money to buy cigarettes in prison.

"I said 'Oh my God, my back is on fire! Take this ... off me!'" Anthony said in an interview with The Associated Press, as he recalled the beginning of weeks of intense itching and agonizing pain.

The government responded with reforms. Among them: The U.S. Bureau of Prisons in the mid-1970s effectively excluded all research by drug companies and other outside agencies within federal prisons.

As the supply of prisoners and mental patients dried up, researchers looked to other countries.

It made sense. Clinical trials could be done more cheaply and with fewer rules. And it was easy to find patients who were taking no medication, a factor that can complicate tests of other drugs.

Additional sets of ethical guidelines have been enacted, and few believe that another Guatemala study could happen today. "It's not that we're out infecting anybody with things," Caplan said.

Still, in the last 15 years, two international studies sparked outrage.

One was likened to Tuskegee. U.S.-funded doctors failed to give the AIDS drug AZT to all the HIV-infected pregnant women in a study in Uganda even though it would have protected their newborns. U.S. health officials argued the study would answer questions about AZT's use in the developing world.

The other study, by Pfizer Inc., gave an antibiotic named Trovan to children with meningitis in Nigeria, although there were doubts about its effectiveness for that disease. Critics blamed the experiment for the deaths of 11 children and the disabling of scores of others. Pfizer settled a lawsuit with Nigerian officials for $75 million but admitted no wrongdoing.

Last year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' inspector general reported that between 40 and 65 percent of clinical studies of federally regulated medical products were done in other countries in 2008, and that proportion probably has grown. The report also noted that U.S. regulators inspected fewer than 1 percent of foreign clinical trial sites.

Monitoring research is complicated, and rules that are too rigid could slow new drug development. But it's often hard to get information on international trials, sometimes because of missing records and a paucity of audits, said Dr. Kevin Schulman, a Duke University professor of medicine who has written on the ethics of international studies.

Syphilis study These issues were still being debated when, last October, the Guatemala study came to light.

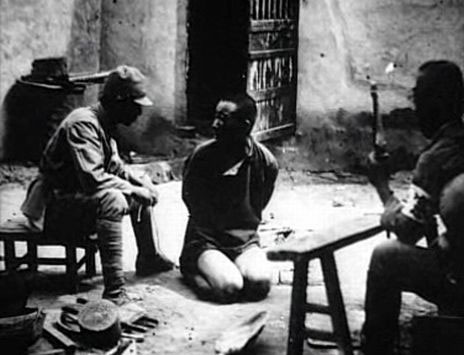

In the 1946-48 study, American scientists infected prisoners and patients in a mental hospital in Guatemala with syphilis, apparently to test whether penicillin could prevent some sexually transmitted disease. The study came up with no useful information and was hidden for decades.

Story: U.S. apologizes for Guatemala syphilis experiments

The Guatemala study nauseated ethicists on multiple levels. Beyond infecting patients with a terrible illness, it was clear that people in the study did not understand what was being done to them or were not able to give their consent. Indeed, though it happened at a time when scientists were quick to publish research that showed frank disinterest in the rights of study participants, this study was buried in file drawers.

"It was unusually unethical, even at the time," said Stark, the Wesleyan researcher.

"When the president was briefed on the details of the Guatemalan episode, one of his first questions was whether this sort of thing could still happen today," said Rick Weiss, a spokesman for the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

That it occurred overseas was an opening for the Obama administration to have the bioethics panel seek a new evaluation of international medical studies. The president also asked the Institute of Medicine to further probe the Guatemala study, but the IOM relinquished the assignment in November, after reporting its own conflict of interest: In the 1940s, five members of one of the IOM's sister organizations played prominent roles in federal syphilis research and had links to the Guatemala study.

So the bioethics commission gets both tasks. To focus on federally funded international studies, the commission has formed an international panel of about a dozen experts in ethics, science and clinical research. Regarding the look at the Guatemala study, the commission has hired 15 staff investigators and is working with additional historians and other consulting experts.

The panel is to send a report to Obama by September. Any further steps would be up to the administration.

Some experts say that given such a tight deadline, it would be a surprise if the commission produced substantive new information about past studies. "They face a really tough challenge," Caplan said.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Controversial and Unethical Psychology Experiments

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Shereen Lehman, MS, is a healthcare journalist and fact checker. She has co-authored two books for the popular Dummies Series (as Shereen Jegtvig).

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Shereen-Lehman-MS-1000-b8eb65ee2fd1437094f29996bd4f8baa.jpg)

There have been a number of famous psychology experiments that are considered controversial, inhumane, unethical, and even downright cruel—here are five examples. Thanks to ethical codes and institutional review boards, most of these experiments could never be performed today.

At a Glance

Some of the most controversial and unethical experiments in psychology include Harlow's monkey experiments, Milgram's obedience experiments, Zimbardo's prison experiment, Watson's Little Albert experiment, and Seligman's learned helplessness experiment.

These and other controversial experiments led to the formation of rules and guidelines for performing ethical and humane research studies.

Harlow's Pit of Despair

Psychologist Harry Harlow performed a series of experiments in the 1960s designed to explore the powerful effects that love and attachment have on normal development. In these experiments, Harlow isolated young rhesus monkeys, depriving them of their mothers and keeping them from interacting with other monkeys.

The experiments were often shockingly cruel, and the results were just as devastating.

The Experiment

The infant monkeys in some experiments were separated from their real mothers and then raised by "wire" mothers. One of the surrogate mothers was made purely of wire.

While it provided food, it offered no softness or comfort. The other surrogate mother was made of wire and cloth, offering some degree of comfort to the infant monkeys.

Harlow found that while the monkeys would go to the wire mother for nourishment, they preferred the soft, cloth mother for comfort.

Some of Harlow's experiments involved isolating the young monkey in what he termed a "pit of despair." This was essentially an isolation chamber. Young monkeys were placed in the isolation chambers for as long as 10 weeks.

Other monkeys were isolated for as long as a year. Within just a few days, the infant monkeys would begin huddling in the corner of the chamber, remaining motionless.

The Results

Harlow's distressing research resulted in monkeys with severe emotional and social disturbances. They lacked social skills and were unable to play with other monkeys.

They were also incapable of normal sexual behavior, so Harlow devised yet another horrifying device, which he referred to as a "rape rack." The isolated monkeys were tied down in a mating position to be bred.

Not surprisingly, the isolated monkeys also ended up being incapable of taking care of their offspring, neglecting and abusing their young.

Harlow's experiments were finally halted in 1985 when the American Psychological Association passed rules regarding treating people and animals in research.

Milgram's Shocking Obedience Experiments

Isabelle Adam/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

If someone told you to deliver a painful, possibly fatal shock to another human being, would you do it? The vast majority of us would say that we absolutely would never do such a thing, but one controversial psychology experiment challenged this basic assumption.

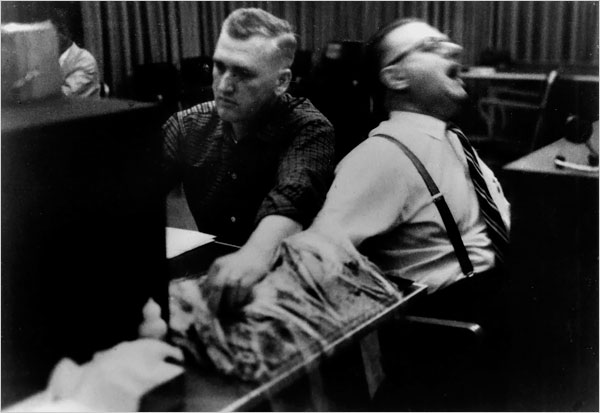

Social psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted a series of experiments to explore the nature of obedience . Milgram's premise was that people would often go to great, sometimes dangerous, or even immoral, lengths to obey an authority figure.

The Experiments

In Milgram's experiment, subjects were ordered to deliver increasingly strong electrical shocks to another person. While the person in question was simply an actor who was pretending, the subjects themselves fully believed that the other person was actually being shocked.

The voltage levels started out at 30 volts and increased in 15-volt increments up to a maximum of 450 volts. The switches were also labeled with phrases including "slight shock," "medium shock," and "danger: severe shock." The maximum shock level was simply labeled with an ominous "XXX."

The results of the experiment were nothing short of astonishing. Many participants were willing to deliver the maximum level of shock, even when the person pretending to be shocked was begging to be released or complaining of a heart condition.

Milgram's experiment revealed stunning information about the lengths that people are willing to go in order to obey, but it also caused considerable distress for the participants involved.

Zimbardo's Simulated Prison Experiment

Darrin Klimek / Getty Images

Psychologist Philip Zimbardo went to high school with Stanley Milgram and had an interest in how situational variables contribute to social behavior.

In his famous and controversial experiment, he set up a mock prison in the basement of the psychology department at Stanford University. Participants were then randomly assigned to be either prisoners or guards. Zimbardo himself served as the prison warden.

The researchers attempted to make a realistic situation, even "arresting" the prisoners and bringing them into the mock prison. Prisoners were placed in uniforms, while the guards were told that they needed to maintain control of the prison without resorting to force or violence.

When the prisoners began to ignore orders, the guards began to utilize tactics that included humiliation and solitary confinement to punish and control the prisoners.

While the experiment was originally scheduled to last two full weeks it had to be halted after just six days. Why? Because the prison guards had started abusing their authority and were treating the prisoners cruelly. The prisoners, on the other hand, started to display signs of anxiety and emotional distress.

It wasn't until a graduate student (and Zimbardo's future wife) Christina Maslach visited the mock prison that it became clear that the situation was out of control and had gone too far. Maslach was appalled at what was going on and voiced her distress. Zimbardo then decided to call off the experiment.

Zimbardo later suggested that "although we ended the study a week earlier than planned, we did not end it soon enough."

Watson and Rayner's Little Albert Experiment

If you have ever taken an Introduction to Psychology class, then you are probably at least a little familiar with Little Albert.

Behaviorist John Watson and his assistant Rosalie Rayner conditioned a boy to fear a white rat, and this fear even generalized to other white objects including stuffed toys and Watson's own beard.

Obviously, this type of experiment is considered very controversial today. Frightening an infant and purposely conditioning the child to be afraid is clearly unethical.

As the story goes, the boy and his mother moved away before Watson and Rayner could decondition the child, so many people have wondered if there might be a man out there with a mysterious phobia of furry white objects.

Controversy

Some researchers have suggested that the boy at the center of the study was actually a cognitively impaired boy who ended up dying of hydrocephalus when he was just six years old. If this is true, it makes Watson's study even more disturbing and controversial.

However, more recent evidence suggests that the real Little Albert was actually a boy named William Albert Barger.

Seligman's Look Into Learned Helplessness

During the late 1960s, psychologists Martin Seligman and Steven F. Maier conducted experiments that involved conditioning dogs to expect an electrical shock after hearing a tone. Seligman and Maier observed some unexpected results.

When initially placed in a shuttle box in which one side was electrified, the dogs would quickly jump over a low barrier to escape the shocks. Next, the dogs were strapped into a harness where the shocks were unavoidable.

After being conditioned to expect a shock that they could not escape, the dogs were once again placed in the shuttlebox. Instead of jumping over the low barrier to escape, the dogs made no efforts to escape the box.

Instead, they simply lay down, whined and whimpered. Since they had previously learned that no escape was possible, they made no effort to change their circumstances. The researchers called this behavior learned helplessness .

Seligman's work is considered controversial because of the mistreating the animals involved in the study.

Impact of Unethical Experiments in Psychology

Many of the psychology experiments performed in the past simply would not be possible today, thanks to ethical guidelines that direct how studies are performed and how participants are treated. While these controversial experiments are often disturbing, we can still learn some important things about human and animal behavior from their results.

Perhaps most importantly, some of these controversial experiments led directly to the formation of rules and guidelines for performing psychology studies.

Blum, Deborah. Love at Goon Park: Harry Harlow and the science of affection . New York: Basic Books; 2011.

Sperry L. Mental Health and Mental Disorders: an Encyclopedia of Conditions, Treatments, and Well-Being . Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC; 2016.

Marcus S. Obedience to Authority An Experimental View. By Stanley Milgram. illustrated . New York: Harper &. The New York Times.

Le Texier T. Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment . Am Psychol . 2019;74(7):823‐839. doi:10.1037/amp0000401

Fridlund AJ, Beck HP, Goldie WD, Irons G. Little Albert: A neurologically impaired child . Hist Psychol. 2012;15(4):302-27. doi:10.1037/a0026720

Powell RA, Digdon N, Harris B, Smithson C. Correcting the record on Watson, Rayner, and Little Albert: Albert Barger as "psychology's lost boy" . Am Psychol . 2014;69(6):600‐611. doi:10.1037/a0036854

Seligman ME. Learned helplessness . Annu Rev Med . 1972;23:407‐412. doi:10.1146/annurev.me.23.020172.002203

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

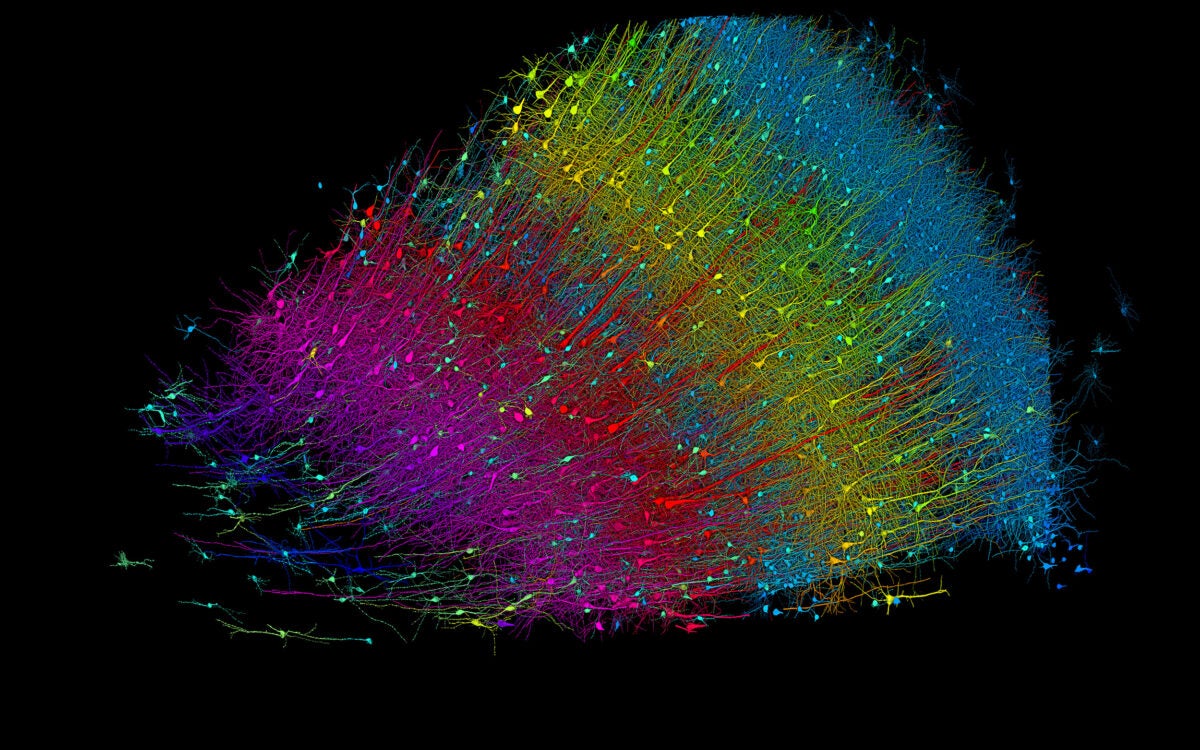

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

What is ‘original scholarship’ in the age of AI?

Complex questions, innovative approaches

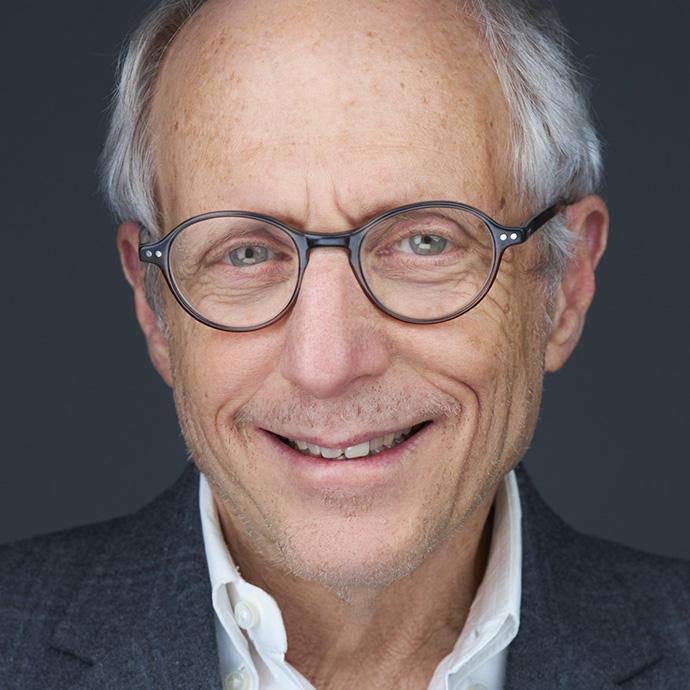

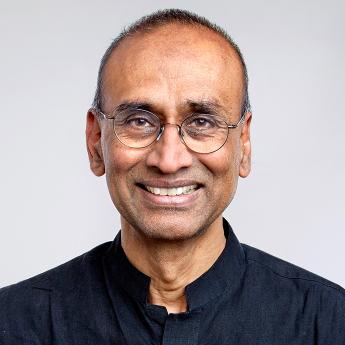

Harvard’s Gary King (pictured) is one in a cohort of researchers rebutting a consortium of 270 scientists known as the Open Science Collaboration, which made worldwide headlines last year when it claimed that it could not replicate the results of 100 published psychology studies.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Study that undercut psych research got it wrong

Peter Reuell

Harvard Staff Writer

Widely reported analysis that said much research couldn’t be reproduced is riddled with its own replication errors, researchers say

According to two Harvard professors and their collaborators, a widely reported study released last year that said more than half of all psychology studies cannot be replicated is itself wrong.

In an attempt to determine the “replicability” of psychological science, a consortium of 270 scientists known as the Open Science Collaboration (OSC) tried to reproduce the results of 100 published studies. More than half of them failed, creating sensational headlines worldwide about the “replication crisis” in psychology.

But an in-depth examination of the data by Daniel Gilbert , the Edgar Pierce Professor of Psychology at Harvard, Gary King , the Albert J. Weatherhead III University Professor at Harvard, Stephen Pettigrew, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Government at Harvard, and Timothy Wilson, the Sherrell J. Aston Professor of Psychology at the University of Virginia, has revealed that the OSC made some serious mistakes that make its pessimistic conclusion completely unwarranted.

The methods of many of the replication studies turn out to be remarkably different from the originals and, according to the four researchers, these “infidelities” had two important consequences.

First, the methods introduced statistical error into the data, which led the OSC to significantly underestimate how many of their replications should have failed by chance alone. When this error is taken into account, the number of failures in their data is no greater than one would expect if all 100 of the original findings had been true.

Second, Gilbert, King, Pettigrew, and Wilson discovered that the low-fidelity studies were four times more likely to fail than were the high-fidelity studies, suggesting that when replicators strayed from the original methods of conducting research, they caused their own studies to fail.

Finally, the OSC used a “low-powered” design. When the four researchers applied this design to a published data set that was known to have a high replication rate, it too showed a low replication rate, suggesting that the OSC’s design was destined from the start to underestimate the replicability of psychological science.

Individually, Gilbert and King said, each of these problems would be enough to cast doubt on the conclusion that most people have drawn from this study, but taken together, they completely repudiate it. The flaws are described in a commentary to be published Friday in Science.

Like most scientists who read the OSC’s article when it appeared, Gilbert, King, Pettigrew, and Wilson were shocked and chagrined. But when they began to scrutinize the methods and reanalyze the raw data, they immediately noticed problems, which started with how the replicators had selected the 100 original studies.

“If you want to estimate a parameter of a population,” said King, “then you either have to randomly sample from that population or make statistical corrections for the fact that you didn’t. The OSC did neither.”

‘Arbitrary list of sampling rules’

“What they did,” added Gilbert, “is create an idiosyncratic, arbitrary list of sampling rules that excluded the majority of psychology’s subfields from the sample, that excluded entire classes of studies whose methods are probably among the best in science from the sample, and so on. Then they proceeded to violate all of their own rules.

“Worse yet, they actually allowed some replicators to have a choice about which studies they would try to replicate. If they had used these same methods to sample people instead of studies, no reputable scientific journal would have published their findings. So the first thing we realized was that no matter what they found — good news or bad news — they never had any chance of estimating the reproducibility of psychological science, which is what the very title of their paper claims they did.”

“And that was just the beginning,” King said. “If you are going to replicate 100 studies, some will fail by chance alone. That’s basic sampling theory. So you have to use statistics to estimate how many of the studies are expected to fail by chance alone because otherwise the number that actually do fail is meaningless.”

According to King, the OSC did this, but made a critical error.

“When they did their calculations, they failed to consider the fact that their replication studies were not just new samples from the same population. They were often quite different from the originals in many ways, and those differences are a source of statistical error. So we did the calculation the right way and then applied it to their data. And guess what? The number of failures they observed was just about what you should expect to observe by chance alone — even if all 100 of the original findings were true. The failure of the replication studies to match the original studies was a failure of the replications, not of the originals.”

Gilbert noted that most people assume that a replication is a “replica”’ of the original study.

“Readers surely assumed that if a group of scientists did 100 replications, then they must have used the same methods to study the same populations. In this case, that assumption would be quite wrong. Replications always vary from originals in minor ways, of course. But if you read the reports carefully, as we did, you discover that many of the replication studies differed in truly astounding ways — ways that make it hard to understand how they could even be called replications.”

As an example, Gilbert described an original study that involved showing white students at Stanford University a video of four other Stanford students discussing admissions policies at their university. Three of those talking were white and one was black. During the discussion, a white student made offensive comments about affirmative action, and the researchers found that the observers looked significantly longer at the black student when they believed he could hear other comments than when they believed he could not.

“So how did they do the replication? With students at the University of Amsterdam!” Gilbert said. “They had Dutch students watch a video of Stanford students, speaking in English, about affirmative action policies at a university more than 5,000 miles away.”

In other words, unlike the participants in the original study, participants in the replication study watched students at a foreign university speaking in a foreign language about an issue of no relevance to them.

But according to Gilbert, that was not the most troubling part of the methodology.

Gilbert: ‘No one involved in this study was trying to deceive anyone. They just made mistakes, as scientists sometimes do.’

“If you dive deep into the data, you discover something else,” Gilbert said. “The replicators realized that doing this study in the Netherlands might have been a problem, so they wisely decided to run another version of it in the U.S. And when they did, they basically replicated the original result. And yet, when the OSC estimated the reproducibility of psychological science, they excluded the successful replication and included only the one from the University of Amsterdam that failed. So the public hears that ‘Yet another psychology study doesn’t replicate’ instead of ‘Yet another psychology study replicates just fine if you do it right, and not if you do it wrong,’ which isn’t a very exciting headline. Some of the replications were quite faithful to the originals, but anyone who carefully reads all the replication reports will find many more examples like this one.”

‘They introduce additional error’

“These infidelities were a problem for another reason,” King added, “namely, that they introduce additional error into the data set. That error can be calculated, and when we do, it turns out that the number of replication studies that actually failed is about what we should expect if every single one of the original findings had been true. Now, one could argue about how best to make this calculation, but the fact is that OSC didn’t make it at all. They simply ignored this potent source of error, and that caused them to draw the wrong conclusions from their data. That doesn’t mean that all 100 studies were true, of course, but it does mean that this article provides no evidence to the contrary.”

“So we now know that the infidelities created statistical noise,” said Gilbert, “but was that all they did? Or were the infidelities of a certain kind? In other words, did they just tend to change the original result, or did they tend to change it in a particular way?”

“To find out,” said King, “we needed a measure of how faithful each of the 100 replications was. Luckily, the OSC supplied it.”

Before each replication began, the OSC asked the original authors to examine the planned replication study and say whether they would endorse it as a faithful replication of their work, and about 70 percent did so.

“We used this as a rough index of fidelity, and when we did, we discovered something important: The low-fidelity replications were an astonishing four times more likely to fail,” King said. “What that suggests is that the infidelities did not just create random statistical noise — they actually biased the studies toward failure.”

In their “technical comment,” Gilbert, King, Pettigrew, and Wilson also note that the OSC used a “low-powered” design. They replicated each of the 100 studies once, using roughly the number of subjects used in the original studies. But according to King, this method artificially depresses the replication rate.

“To show how this happens, we took another published article that had examined the replicability of a group of classic psychology studies,” said King. “The authors of that paper had used a very high-powered design — they replicated each study with more than 30 times the original number of participants — and that high-powered design produced a very high replication rate. So we asked a simple question: What would have happened if these authors had used the low-powered design that was used by the OSC? The answer is that the replication rate would have been even lower than the replication rate found by the OSC.”

Despite uncovering serious problems with the landmark study, Gilbert and King emphasized that their critique does not suggest wrongdoing and is simply part of the normal process of scientific inquiry.

“Let’s be clear, Gilbert said. “No one involved in this study was trying to deceive anyone. They just made mistakes, as scientists sometimes do. Many of the OSC members are our friends, and the corresponding author, Brian Nosek, is actually a good friend who was both forthcoming and helpful to us as we wrote our critique. In fact, Brian is the one who suggested one of the methods we used for correcting the OSC’s error calculations. So this is not a personal attack, this is a scientific critique.

“We all care about the same things: doing science well and finding out what’s true. We were glad to see that in their response to our comment, the OSC quibbled about a number of minor issues but conceded the major one, which is that their paper does not provide evidence for the pessimistic conclusions that most people have drawn from it.”

“I think the big takeaway point here is that meta-science must obey the rules of science,” King said. “All the rules about sampling and calculating error and keeping experimenters blind to the hypothesis — all of those rules must apply whether you are studying people or studying the replicability of a science. Meta-science does not get a pass. It is not exempt. And those doing meta-science are not above the fray. They are part of the scientific process. If you violate the basic rules of science, you get the wrong answer, and that’s what happened here.”

“This [OSC] paper has had extraordinary impact,” Gilbert said. “It was Science magazine’s No. 3 ‘ Breakthrough of the Year’ across all fields of science. It led to changes in policy at many scientific journals, changes in priorities at funding agencies, and it seriously undermined public perceptions of psychology. So it is not enough now, in the sober light of retrospect, to say that mistakes were made. These mistakes had very serious repercussions. We hope the OSC will now work as hard to correct the public misperceptions of their findings as they did to produce the findings themselves.”

The OSC’s reply to “technical comments” by Gilbert and others, and Gilbert and others’ response to that reply, can be found here .

Share this article

You might like.

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

Symposium considers how technology is changing academia

Seven projects awarded Star-Friedman Challenge grants

Excited about new diet drug? This procedure seems better choice.

Study finds minimally invasive treatment more cost-effective over time, brings greater weight loss

How far has COVID set back students?

An economist, a policy expert, and a teacher explain why learning losses are worse than many parents realize

Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

12 reasons research goes wrong.

FIXING THE NUMBERS Massaging data, small sample sizes and other issues can affect the statistical analyses of studies and distort the results, and that's not all that can go wrong.

Justine Hirshfeld/ Science News

Share this:

By Tina Hesman Saey

January 13, 2015 at 2:23 pm

For more on reproducibility in science, see SN’s feature “ Is redoing scientific research the best way to find truth? “

Barriers to research replication are based largely in a scientific culture that pits researchers against each other in competition for scarce resources. Any or all of the factors below, plus others, may combine to skew results.

Pressure to publish

Research funds are tighter than ever and good positions are hard to come by. To get grants and jobs, scientists need to publish, preferably in big-name journals. That pressure may lead researchers to publish many low-quality studies instead of aiming for a smaller number of well-done studies. To convince administrators and grant reviewers of the worthiness of their work, scientists have to be cheerleaders for their research; they may not be as critical of their results as they should be.

Impact factor mania

For scientists, publishing in a top journal — such as Nature , Science or Cell — with high citation rates or “impact factors” is like winning a medal. Universities and funding agencies award jobs and money disproportionately to researchers who publish in these journals. Many researchers say the science in those journals isn’t better than studies published elsewhere, it’s just splashier and tends not to reflect the messy reality of real-world data. Mania linked to publishing in high-impact journals may encourage researchers to do just about anything to publish there, sacrificing the quality of their science as a result.

Tainted cultures

Experiments can get contaminated and cells and animals may not be as advertised. In hundreds of instances since the 1960s, researchers misidentified cells they were working with. Contamination led to the erroneous report that the XMRV virus causes chronic fatigue syndrome, and a recent report suggests that bacterial DNA in lab reagents can interfere with microbiome studies.

Do the wrong kinds of statistical analyses and results may be skewed. Some researchers accuse colleagues of “p-hacking,” massaging data to achieve particular statistical criteria. Small sample sizes and improper randomization of subjects or “blinding” of the researchers can also lead to statistical errors. Data-heavy studies require multiple convoluted steps to analyze, with lots of opportunity for error. Researchers can often find patterns in their mounds of data that have no biological meaning.

Sins of omission

To thwart their competition, some scientists may leave out important details. One study found that 54 percent of research papers fail to properly identify resources, such as the strain of animals or types of reagents or antibodies used in the experiments. Intentional or not, the result is the same: Other researchers can’t replicate the results.

Biology is messy

Variability among and between people, animals and cells means that researchers never get exactly the same answer twice. Unknown variables abound and make replicating in the life and social sciences extremely difficult.

Peer review doesn’t work

Peer reviewers are experts in their field who evaluate research manuscripts and determine whether the science is strong enough to be published in a journal. A sting conducted by Science found some journals that don’t bother with peer review, or use a rubber stamp review process. Another study found that peer reviewers aren’t very good at spotting errors in papers. A high-profile case of misconduct concerning stem cells revealed that even when reviewers do spot fatal flaws, journals sometimes ignore the recommendations and publish anyway ( SN: 12/27/14, p. 25 ).

Some scientists don’t share

Collecting data is hard work and some scientists see a competitive advantage to not sharing their raw data. But selfishness also makes it impossible to replicate many analyses, especially those involving expensive clinical trials or massive amounts of data.

Research never reported

Journals want new findings, not repeats or second-place finishers. That gives researchers little incentive to check previously published work or to try to publish those findings if they do. False findings go unchallenged and negative results — ones that show no evidence to support the scientist’s hypothesis — are rarely published. Some people fear that scientists may leave out important, correct results that don’t fit a given hypothesis and publish only experiments that do.

Poor training produces sloppy scientists

Some researchers complain that young scientists aren’t getting proper training to conduct rigorous work and to critically evaluate their own and others’ studies.

Mistakes happen

Scientists are human, and therefore, fallible. Of 423 papers retracted due to honest error between 1979 and 2011, more than half were pulled because of mistakes, such as measuring a drug incorrectly.

Researchers who make up data or manipulate it produce results no one can replicate. However, fraud is responsible for only a tiny fraction of results that can’t be replicated.

More Stories from Science News on Science & Society

A hidden danger lurks beneath Yellowstone

Online spaces may intensify teens’ uncertainty in social interactions

Want to see butterflies in your backyard? Try doing less yardwork

Ximena Velez-Liendo is saving Andean bears with honey

‘Flavorama’ guides readers through the complex landscape of flavor

Rain Bosworth studies how deaf children experience the world

Separating science fact from fiction in Netflix’s ‘3 Body Problem’

Language models may miss signs of depression in Black people’s Facebook posts

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

10 Psychological Experiments That Could Never Happen Today

By meredith danko | sep 20, 2013.

Nowadays, the American Psychological Association has a Code of Conduct in place when it comes to ethics in psychological experiments. Experimenters must adhere to various rules pertaining to everything from confidentiality to consent to overall beneficence. Review boards are in place to enforce these ethics. But the standards were not always so strict, which is how some of the most famous studies in psychology came about.

1. The Little Albert Experiment

At Johns Hopkins University in 1920, John B. Watson conducted a study of classical conditioning, a phenomenon that pairs a conditioned stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus until they produce the same result. This type of conditioning can create a response in a person or animal towards an object or sound that was previously neutral. Classical conditioning is commonly associated with Ivan Pavlov, who rang a bell every time he fed his dog until the mere sound of the bell caused his dog to salivate.

Watson tested classical conditioning on a 9-month-old baby he called Albert B. The young boy started the experiment loving animals, particularly a white rat. Watson started pairing the presence of the rat with the loud sound of a hammer hitting metal. Albert began to develop a fear of the white rat as well as most animals and furry objects. The experiment is considered particularly unethical today because Albert was never desensitized to the phobias that Watson produced in him. (The child died of an unrelated illness at age 6, so doctors were unable to determine if his phobias would have lasted into adulthood.)

2. Asch Conformity Experiments

Solomon Asch tested conformity at Swarthmore College in 1951 by putting a participant in a group of people whose task was to match line lengths. Each individual was expected to announce which of three lines was the closest in length to a reference line. But the participant was placed in a group of actors, who were all told to give the correct answer twice then switch to each saying the same incorrect answer. Asch wanted to see whether the participant would conform and start to give the wrong answer as well, knowing that he would otherwise be a single outlier.

Thirty-seven of the 50 participants agreed with the incorrect group despite physical evidence to the contrary. Asch used deception in his experiment without getting informed consent from his participants, so his study could not be replicated today.

3. The Bystander Effect

Some psychological experiments that were designed to test the bystander effect are considered unethical by today’s standards. In 1968, John Darley and Bibb Latané developed an interest in crime witnesses who did not take action. They were particularly intrigued by the murder of Kitty Genovese , a young woman whose murder was witnessed by many, but still not prevented.

The pair conducted a study at Columbia University in which they would give a participant a survey and leave him alone in a room to fill out the paper. Harmless smoke would start to seep into the room after a short amount of time. The study showed that the solo participant was much faster to report the smoke than participants who had the exact same experience, but were in a group.

The studies became progressively unethical by putting participants at risk of psychological harm. Darley and Latané played a recording of an actor pretending to have a seizure in the headphones of a person, who believed he or she was listening to an actual medical emergency that was taking place down the hall. Again, participants were much quicker to react when they thought they were the sole person who could hear the seizure.

4. The Milgram Experiment

Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram hoped to further understand how so many people came to participate in the cruel acts of the Holocaust. He theorized that people are generally inclined to obey authority figures, posing the question , “Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?” In 1961, he began to conduct experiments of obedience.

Participants were under the impression that they were part of a study of memory . Each trial had a pair divided into “teacher” and “learner,” but one person was an actor, so only one was a true participant. The drawing was rigged so that the participant always took the role of “teacher.” The two were moved into separate rooms and the “teacher” was given instructions. He or she pressed a button to shock the “learner” each time an incorrect answer was provided. These shocks would increase in voltage each time. Eventually, the actor would start to complain followed by more and more desperate screaming. Milgram learned that the majority of participants followed orders to continue delivering shocks despite the clear discomfort of the “learner.”

Had the shocks existed and been at the voltage they were labeled, the majority would have actually killed the “learner” in the next room. Having this fact revealed to the participant after the study concluded would be a clear example of psychological harm.

5. Harlow’s Monkey Experiments

In the 1950s, Harry Harlow of the University of Wisconsin tested infant dependency using rhesus monkeys in his experiments rather than human babies. The monkey was removed from its actual mother which was replaced with two “mothers,” one made of cloth and one made of wire. The cloth “mother” served no purpose other than its comforting feel whereas the wire “mother” fed the monkey through a bottle. The monkey spent the majority of his day next to the cloth “mother” and only around one hour a day next to the wire “mother,” despite the association between the wire model and food.

Harlow also used intimidation to prove that the monkey found the cloth “mother” to be superior. He would scare the infants and watch as the monkey ran towards the cloth model. Harlow also conducted experiments which isolated monkeys from other monkeys in order to show that those who did not learn to be part of the group at a young age were unable to assimilate and mate when they got older. Harlow’s experiments ceased in 1985 due to APA rules against the mistreatment of animals as well as humans . However, Department of Psychiatry Chair Ned H. Kalin, M.D. of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health has recently begun similar experiments that involve isolating infant monkeys and exposing them to frightening stimuli. He hopes to discover data on human anxiety, but is meeting with resistance from animal welfare organizations and the general public.

6. Learned Helplessness

The ethics of Martin Seligman’s experiments on learned helplessness would also be called into question today due to his mistreatment of animals. In 1965, Seligman and his team used dogs as subjects to test how one might perceive control. The group would place a dog on one side of a box that was divided in half by a low barrier. Then they would administer a shock, which was avoidable if the dog jumped over the barrier to the other half. Dogs quickly learned how to prevent themselves from being shocked.

Seligman’s group then harnessed a group of dogs and randomly administered shocks, which were completely unavoidable. The next day, these dogs were placed in the box with the barrier. Despite new circumstances that would have allowed them to escape the painful shocks, these dogs did not even try to jump over the barrier; they only cried and did not jump at all, demonstrating learned helplessness.

7. Robbers Cave Experiment

Muzafer Sherif conducted the Robbers Cave Experiment in the summer of 1954, testing group dynamics in the face of conflict. A group of preteen boys were brought to a summer camp, but they did not know that the counselors were actually psychological researchers. The boys were split into two groups, which were kept very separate. The groups only came into contact with each other when they were competing in sporting events or other activities.

The experimenters orchestrated increased tension between the two groups, particularly by keeping competitions close in points. Then, Sherif created problems, such as a water shortage, that would require both teams to unite and work together in order to achieve a goal. After a few of these, the groups became completely undivided and amicable.

Though the experiment seems simple and perhaps harmless, it would still be considered unethical today because Sherif used deception as the boys did not know they were participating in a psychological experiment. Sherif also did not have informed consent from participants.

8. The Monster Study

At the University of Iowa in 1939, Wendell Johnson and his team hoped to discover the cause of stuttering by attempting to turn orphans into stutterers. There were 22 young subjects, 12 of whom were non-stutterers. Half of the group experienced positive teaching whereas the other group dealt with negative reinforcement. The teachers continually told the latter group that they had stutters. No one in either group became stutterers at the end of the experiment, but those who received negative treatment did develop many of the self-esteem problems that stutterers often show. Perhaps Johnson’s interest in this phenomenon had to do with his own stutter as a child , but this study would never pass with a contemporary review board.

Johnson’s reputation as an unethical psychologist has not caused the University of Iowa to remove his name from its Speech and Hearing Clinic .

9. Blue Eyed versus Brown Eyed Students

Jane Elliott was not a psychologist, but she developed one of the most famously controversial exercises in 1968 by dividing students into a blue-eyed group and a brown-eyed group. Elliott was an elementary school teacher in Iowa, who was trying to give her students hands-on experience with discrimination the day after Martin Luther King Jr. was shot, but this exercise still has significance to psychology today. The famous exercise even transformed Elliott’s career into one centered around diversity training.

After dividing the class into groups, Elliott would cite phony scientific research claiming that one group was superior to the other. Throughout the day, the group would be treated as such. Elliott learned that it only took a day for the “superior” group to turn crueler and the “inferior” group to become more insecure. The blue eyed and brown eyed groups then switched so that all students endured the same prejudices.

Elliott’s exercise (which she repeated in 1969 and 1970) received plenty of public backlash, which is probably why it would not be replicated in a psychological experiment or classroom today. The main ethical concerns would be with deception and consent, though some of the original participants still regard the experiment as life-changing .

10. The Stanford Prison Experiment

In 1971, Philip Zimbardo of Stanford University conducted his famous prison experiment, which aimed to examine group behavior and the importance of roles. Zimbardo and his team picked a group of 24 male college students who were considered “healthy,” both physically and psychologically. The men had signed up to participate in a “ psychological study of prison life ,” which would pay them $15 per day. Half were randomly assigned to be prisoners and the other half were assigned to be prison guards. The experiment played out in the basement of the Stanford psychology department where Zimbardo’s team had created a makeshift prison. The experimenters went to great lengths to create a realistic experience for the prisoners, including fake arrests at the participants’ homes.

The prisoners were given a fairly standard introduction to prison life, which included being deloused and assigned an embarrassing uniform. The guards were given vague instructions that they should never be violent with the prisoners, but needed to stay in control. The first day passed without incident, but the prisoners rebelled on the second day by barricading themselves in their cells and ignoring the guards. This behavior shocked the guards and presumably led to the psychological abuse that followed. The guards started separating “good” and “bad” prisoners, and doled out punishments including push ups, solitary confinement, and public humiliation to rebellious prisoners.

Zimbardo explained , “In only a few days, our guards became sadistic and our prisoners became depressed and showed signs of extreme stress.” Two prisoners dropped out of the experiment; one eventually became a psychologist and a consultant for prisons . The experiment was originally supposed to last for two weeks, but it ended early when Zimbardo’s future wife, psychologist Christina Maslach, visited the experiment on the fifth day and told him , “I think it’s terrible what you’re doing to those boys.”

Despite the unethical experiment, Zimbardo is still a working psychologist today. He was even honored by the American Psychological Association with a Gold Medal Award for Life Achievement in the Science of Psychology in 2012 .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier Sponsored Documents

The victims of unethical human experiments and coerced research under National Socialism

Paul weindling.

1 Oxford Brookes University, History, Philosophy and Religion, Headington Campus, Oxford OX3 0BP, United Kingdom

Anna von Villiez

2 Independent Data Analyst

Aleksandra Loewenau

3 Oxford Brookes University, Centre for Medical Humanities, Department of History, Philosophy and Religion, Gypsy Lane, Oxford OX3 0BP, United Kingdom

4 University of Calgary, Cumming School of Medicine, 2500 University Drive NW, Calgary T2N 1N4, Canada

Nichola Farron

5 Independent Holocaust Historian

- • Human experiments were more extensive than often assumed with a minimum of 15,750 documented victims.

- • Experiments rapidly increased from 1942, reaching a high point in 1943 and sustained until the end of the war.

- • There were more victims who survived than were killed as part of or as a result of the experiments. Many survived with severe injuries.

- • Victims came from diverse nationalities with Poles (Jews and Roman Catholics) as the largest national cohort.

- • Body parts, especially from euthanasia killings, were often retained for research and teaching after 1945.

There has been no full evaluation of the numbers of victims of Nazi research, who the victims were, and of the frequency and types of experiments and research. This paper gives the first results of a comprehensive evidence-based evaluation of the different categories of victims. Human experiments were more extensive than often assumed with a minimum of 15,754 documented victims. Experiments rapidly increased from 1942, reaching a high point in 1943. The experiments remained at a high level of intensity despite imminent German defeat in 1945. There were more victims who survived than were killed as part of or as a result of the experiments, and the survivors often had severe injuries.

The coerced human experiments and research under National Socialism constitute a reference point in modern bioethics. 7 Yet discussions of consent and the need for safeguards for research subjects to date lack a firm basis in historical evidence. There has been no full evaluation of the numbers of victims of Nazi research, who the victims were, and of the frequency and types of experiments and research. The one partial estimate is restricted to experiments cited at the Nuremberg Medical Trial. This paper gives the first results of a comprehensive evidence-based evaluation of the different categories of victims. In 1945 liberated prisoners from German concentration camps began to collect evidence of the experiments.

The scientific intelligence officer John Thompson then pointed out not only that 90% of all medical research under National Socialism was criminal, but also the need to evaluate all criminal experiments under National Socialism, and not just those whose perpetrators were available for arrest and prosecution. 8 The Nuremberg Medical Trial of 1946–47 was necessarily selective as to who was available for prosecution, and since then only clusters of victims have been identified. 9 In the early 1980s Günther Schwarberg named a set of child victims: his reconstruction the life histories of the ‘twenty children’ killed after transport from Auschwitz for a tuberculosis immunisation experiment at Neuengamme concentration camp was exemplary. 10 The question arises whether what Schwarberg achieved in microcosm can be achieved for the totality of victims. Our aim is to identify not just clusters of victims but all victims of unethical medical research under National Socialism. The methodology is that of record linkage to reconstruct life histories of the total population of all such research victims. This allows one to place individual survivors and groups of victims within a wider context.

This project on the victims of Nazi medical research represents the fulfilment of Thompson's original scheme of a complete record of all coerced experiments and their victims. 11 Our project identifies for the first time the victims of Nazi coercive research, and reconstructs their life histories as far as possible. Biographical data found in many different archives and collections is linked to compile a full life history, and subjective narratives and administrative data are compared. Results are aggregated here as cohorts because of undertakings as regards anonymisation, given in order to gain access to key sources. All data is verifiable through the project database.

The criterion for unethical research is whether coercion by researchers was involved, or whether the location was coercive. The project has covered involuntary research in clinical contexts as psychiatric hospitals, incarceration in concentration camps and prisoner of war camps, the ‘euthanasia’ killings of psychiatric patients with subsequent retention of body parts for research, and executions of political victims, when body parts were sent to university anatomical institutes, and persons subjected to anthropological research in coercive and life threatening situations as ghettoes and concentration camps.

Without a reliable, evidence-based historical analysis, compensation for surviving victims has involved many problems. Victim numbers have been consistently underestimated from the first compensation scheme in 1951 when the assumption was of only few hundred survivors. 12 The assumption was that most experiments were fatal. This project's use of several thousand compensation records in countries where victims lived (as Poland) or migrated to (as Israel), or were collected by the United Nations or the German government has corrected this impression. The availability of person-related evidence from the International Tracing Service at Bad Arolsen further helps to determine whether a victim survived. Major repositories of documents like the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Yad Vashem archives, court records in war crimes proceedings, and oral history collections notably the Shoah Foundation have been consulted. Record linkage of named records is essential for the project, and shows how a single person could be the victim of research on multiple occasions. Father Leon Michałowski, born 22 March 1909 in Wąbrzeźno, was subjected to malaria in August 1942 and then to freezing experiments in October 1942 ( Figure 1 ).

Malaria card of Father Bruno Stachowski from Claus Schilling's research at Dachau. Approximately 1000 cards were kept back from destruction by the prisoner assistant Eugène Ost. International Tracing Service, source number 1079406301.

A further issue relates to the methods and organisation of the research. From the 1950s the experiments were viewed as ‘pseudo-science’, in effect marginalising them from mainstream science under National Socialism. For the purpose of this study, the experiments have been viewed as part of mainstream German medical research, as this renders rationales and supportive networks historically intelligible. It is clear that prestigious research institutions such as the Kaiser Wilhelm Society and funding agencies such as the German Research Fund were involved. 13 It has been argued more recently that some experiments were cutting edge science. 14 Another view is that the approach and methods were scientific albeit of varying quality. For the purpose of this study, the experiments have been viewed as part of mainstream German medical research, as this renders rationales and supportive networks intelligible.

Defining what constitutes research is problematic. For example, a listing of operations in a concentration camp may be nothing more than a clinical record, may have been undertaken by young surgeons seeking to improve their skills, or may indeed have involved research. As stated above, only confirmed data of research has been utilised in the project's category of a verified instance of unethical research. The only exception is the corpses sent to anatomical institutes for research purposes. 15 Separating these out often does not appear possible, but the project includes anatomical research on body parts and brains as separate categories.

The project has graded victim evidence into two categories, so that there should be a set of verifiable and proven victims established as incontestable evidence of having been a victim. The unexpectedly high numbers of identified experiment victims makes this necessary. The two categories are:

- 1. those who were identified as confirmed victims through a reliable source such as experimental records kept at the time.

- 2. those who have claimed to have been experimented on, but confirmation could not so far be obtained.

The project did not set out to adjudicate on the authenticity of victims’ claims. In Warsaw ca. 3600 compensation files of victims of human experiments were viewed, while there are a further 10,000 files representing claims deemed unsuccessful. It is sometimes unclear whether extensive injuries were retrospectively defined to have resulted from an experiment to meet the criteria of the compensation scheme offered by the Federal Republic of Germany in various forms since 1951, or whether experimentation had taken place in a hitherto unknown location. The project discounted claims of abuse when no experiment or research was involved, or when victims having misunderstood compensation schemes for experiments being about ‘experiences’. It is hoped that further research will provide confirmation of experiments in disputed locations like the concentration camps of Stutthof and Theresienstadt. 16 While Yugoslav victims were abused for experiments in German concentration camps, claims for experiments in the former Yugoslavia and Northern Norway have not so far been confirmed. The grading of victims’ claims into the verified and as yet unverified enable the project to establish verifiable minimum numbers, while indicating the possibility of higher numbers being confirmed by further research.

Project findings