Advantages and Disadvantages of Interview in Research

Approaching the Respondent- according to the Interviewer’s Manual, the introductory tasks of the interviewer are: tell the interviewer is and whom he or she represents; telling him about what the study is, in a way to stimulate his interest. The interviewer has also ensured at this stage that his answers are confidential; tell the respondent how he was chosen; use letters and clippings of surveys in order to show the importance of the study to the respondent. The interviewer must be adaptable, friendly, responsive, and should make the interviewer feel at ease to say anything, even if it is irrelevant.

Dealing with Refusal- there can be plenty of reasons for refusing for an interview, for example, a respondent may feel that surveys are a waste of time, or may express anti-government feeling. It is the interviewer’s job to determine the reason for the refusal of the interview and attempt to overcome it.

Conducting the Interview- the questions should be asked as worded for all respondents in order to avoid misinterpretation of the question. Clarification of the question should also be avoided for the same reason. However, the questions can be repeated in case of misunderstanding. The questions should be asked in the same order as mentioned in the questionnaire, as a particular question might not make sense if the questions before they are skipped. The interviewers must be very careful to be neutral before starting the interview so as not to lead the respondent, hence minimizing bias.

listing out the advantages of interview studies, which are noted below:

- It provides flexibility to the interviewers

- The interview has a better response rate than mailed questions, and the people who cannot read and write can also answer the questions.

- The interviewer can judge the non-verbal behavior of the respondent.

- The interviewer can decide the place for an interview in a private and silent place, unlike the ones conducted through emails which can have a completely different environment.

- The interviewer can control over the order of the question, as in the questionnaire, and can judge the spontaneity of the respondent as well.

There are certain disadvantages of interview studies as well which are:

- Conducting interview studies can be very costly as well as very time-consuming.

- An interview can cause biases. For example, the respondent’s answers can be affected by his reaction to the interviewer’s race, class, age or physical appearance.

- Interview studies provide less anonymity, which is a big concern for many respondents.

- There is a lack of accessibility to respondents (unlike conducting mailed questionnaire study) since the respondents can be in around any corner of the world or country.

INTERVIEW AS SOCIAL INTERACTION

The interview subjects to the same rules and regulations of other instances of social interaction. It is believed that conducting interview studies has possibilities for all sorts of bias, inconsistency, and inaccuracies and hence many researchers are critical of the surveys and interviews. T.R. William says that in certain societies there may be patterns of people saying one thing, but doing another. He also believes that the responses should be interpreted in context and two social contexts should not be compared to each other. Derek L. Phillips says that the survey method itself can manipulate the data, and show the results that actually does not exist in the population in real. Social research becomes very difficult due to the variability in human behavior and attitude. Other errors that can be caused in social research include-

- deliberate lying, because the respondent does not want to give a socially undesirable answer;

- unconscious mistakes, which mostly occurs when the respondent has socially undesirable traits that he does not want to accept;

- when the respondent accidentally misunderstands the question and responds incorrectly;

- when the respondent is unable to remember certain details.

Apart from the errors caused by the responder, there are also certain errors made by the interviewers that may include-

- errors made by altering the questionnaire, through changing some words or omitting certain questions;

- biased, irrelevant, inadequate or unnecessary probing;

- recording errors, or consciously making errors in recording.

Bailey, K. (1994). Interview Studies in Methods of social research. Simonand Schuster, 4th ed. The Free Press, New York NY 10020.Ch8. Pp.173-213.

Sociology Group

We believe in sharing knowledge with everyone and making a positive change in society through our work and contributions. If you are interested in joining us, please check our 'About' page for more information

The Interview Method In Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Interviews involve a conversation with a purpose, but have some distinct features compared to ordinary conversation, such as being scheduled in advance, having an asymmetry in outcome goals between interviewer and interviewee, and often following a question-answer format.

Interviews are different from questionnaires as they involve social interaction. Unlike questionnaire methods, researchers need training in interviewing (which costs money).

How Do Interviews Work?

Researchers can ask different types of questions, generating different types of data . For example, closed questions provide people with a fixed set of responses, whereas open questions allow people to express what they think in their own words.

The researcher will often record interviews, and the data will be written up as a transcript (a written account of interview questions and answers) which can be analyzed later.

It should be noted that interviews may not be the best method for researching sensitive topics (e.g., truancy in schools, discrimination, etc.) as people may feel more comfortable completing a questionnaire in private.

There are different types of interviews, with a key distinction being the extent of structure. Semi-structured is most common in psychology research. Unstructured interviews have a free-flowing style, while structured interviews involve preset questions asked in a particular order.

Structured Interview

A structured interview is a quantitative research method where the interviewer a set of prepared closed-ended questions in the form of an interview schedule, which he/she reads out exactly as worded.

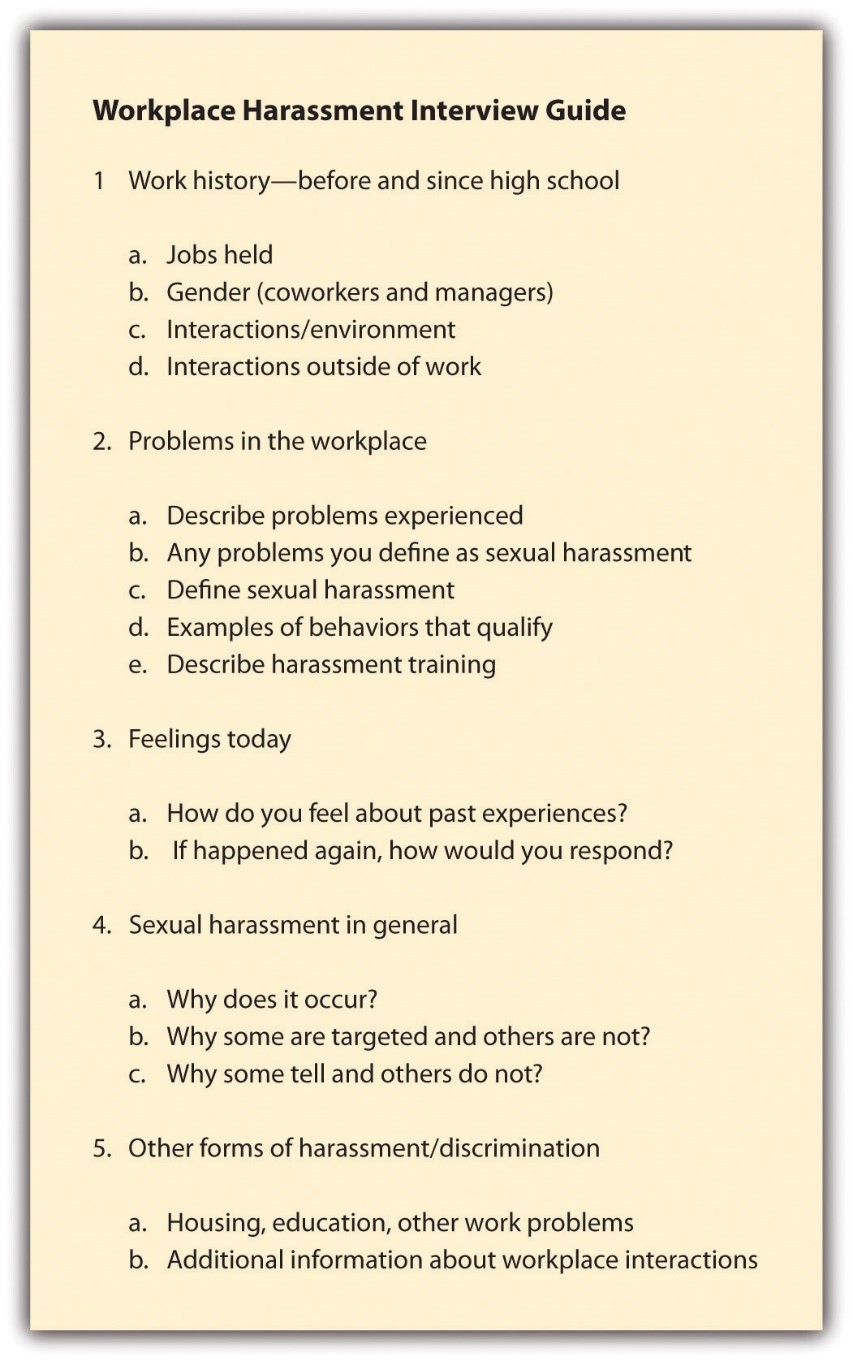

Interviews schedules have a standardized format, meaning the same questions are asked to each interviewee in the same order (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. An example of an interview schedule

The interviewer will not deviate from the interview schedule (except to clarify the meaning of the question) or probe beyond the answers received. Replies are recorded on a questionnaire, and the order and wording of questions, and sometimes the range of alternative answers, is preset by the researcher.

A structured interview is also known as a formal interview (like a job interview).

- Structured interviews are easy to replicate as a fixed set of closed questions are used, which are easy to quantify – this means it is easy to test for reliability .

- Structured interviews are fairly quick to conduct which means that many interviews can take place within a short amount of time. This means a large sample can be obtained, resulting in the findings being representative and having the ability to be generalized to a large population.

Limitations

- Structured interviews are not flexible. This means new questions cannot be asked impromptu (i.e., during the interview), as an interview schedule must be followed.

- The answers from structured interviews lack detail as only closed questions are asked, which generates quantitative data . This means a researcher won’t know why a person behaves a certain way.

Unstructured Interview

Unstructured interviews do not use any set questions, instead, the interviewer asks open-ended questions based on a specific research topic, and will try to let the interview flow like a natural conversation. The interviewer modifies his or her questions to suit the candidate’s specific experiences.

Unstructured interviews are sometimes referred to as ‘discovery interviews’ and are more like a ‘guided conservation’ than a strictly structured interview. They are sometimes called informal interviews.

Unstructured interviews are most useful in qualitative research to analyze attitudes and values. Though they rarely provide a valid basis for generalization, their main advantage is that they enable the researcher to probe social actors’ subjective points of view.

Interviewer Self-Disclosure

Interviewer self-disclosure involves the interviewer revealing personal information or opinions during the research interview. This may increase rapport but risks changing dynamics away from a focus on facilitating the interviewee’s account.

In unstructured interviews, the informal conversational style may deliberately include elements of interviewer self-disclosure, mirroring ordinary conversation dynamics.

Interviewer self-disclosure risks changing the dynamics away from facilitation of interviewee accounts. It should not be ruled out entirely but requires skillful handling informed by reflection.

- An informal interviewing style with some interviewer self-disclosure may increase rapport and participant openness. However, it also increases the chance of the participant converging opinions with the interviewer.

- Complete interviewer neutrality is unlikely. However, excessive informality and self-disclosure risk the interview becoming more of an ordinary conversation and producing consensus accounts.

- Overly personal disclosures could also be seen as irrelevant and intrusive by participants. They may invite increased intimacy on uncomfortable topics.

- The safest approach seems to be to avoid interviewer self-disclosures in most cases. Where an informal style is used, disclosures require careful judgment and substantial interviewing experience.

- If asked for personal opinions during an interview, the interviewer could highlight the defined roles and defer that discussion until after the interview.

- Unstructured interviews are more flexible as questions can be adapted and changed depending on the respondents’ answers. The interview can deviate from the interview schedule.

- Unstructured interviews generate qualitative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondent to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation.

- They also have increased validity because it gives the interviewer the opportunity to probe for a deeper understanding, ask for clarification & allow the interviewee to steer the direction of the interview, etc. Interviewers have the chance to clarify any questions of participants during the interview.

- It can be time-consuming to conduct an unstructured interview and analyze the qualitative data (using methods such as thematic analysis).

- Employing and training interviewers is expensive and not as cheap as collecting data via questionnaires . For example, certain skills may be needed by the interviewer. These include the ability to establish rapport and knowing when to probe.

- Interviews inevitably co-construct data through researchers’ agenda-setting and question-framing. Techniques like open questions provide only limited remedies.

Focus Group Interview

Focus group interview is a qualitative approach where a group of respondents are interviewed together, used to gain an in‐depth understanding of social issues.

This type of interview is often referred to as a focus group because the job of the interviewer ( or moderator ) is to bring the group to focus on the issue at hand. Initially, the goal was to reach a consensus among the group, but with the development of techniques for analyzing group qualitative data, there is less emphasis on consensus building.

The method aims to obtain data from a purposely selected group of individuals rather than from a statistically representative sample of a broader population.

The role of the interview moderator is to make sure the group interacts with each other and do not drift off-topic. Ideally, the moderator will be similar to the participants in terms of appearance, have adequate knowledge of the topic being discussed, and exercise mild unobtrusive control over dominant talkers and shy participants.

A researcher must be highly skilled to conduct a focus group interview. For example, the moderator may need certain skills, including the ability to establish rapport and know when to probe.

- Group interviews generate qualitative narrative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondents to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation. Qualitative data also includes observational data, such as body language and facial expressions.

- Group responses are helpful when you want to elicit perspectives on a collective experience, encourage diversity of thought, reduce researcher bias, and gather a wider range of contextualized views.

- They also have increased validity because some participants may feel more comfortable being with others as they are used to talking in groups in real life (i.e., it’s more natural).

- When participants have common experiences, focus groups allow them to build on each other’s comments to provide richer contextual data representing a wider range of views than individual interviews.

- Focus groups are a type of group interview method used in market research and consumer psychology that are cost – effective for gathering the views of consumers .

- The researcher must ensure that they keep all the interviewees” details confidential and respect their privacy. This is difficult when using a group interview. For example, the researcher cannot guarantee that the other people in the group will keep information private.

- Group interviews are less reliable as they use open questions and may deviate from the interview schedule, making them difficult to repeat.

- It is important to note that there are some potential pitfalls of focus groups, such as conformity, social desirability, and oppositional behavior, that can reduce the usefulness of the data collected.

For example, group interviews may sometimes lack validity as participants may lie to impress the other group members. They may conform to peer pressure and give false answers.

To avoid these pitfalls, the interviewer needs to have a good understanding of how people function in groups as well as how to lead the group in a productive discussion.

Semi-Structured Interview

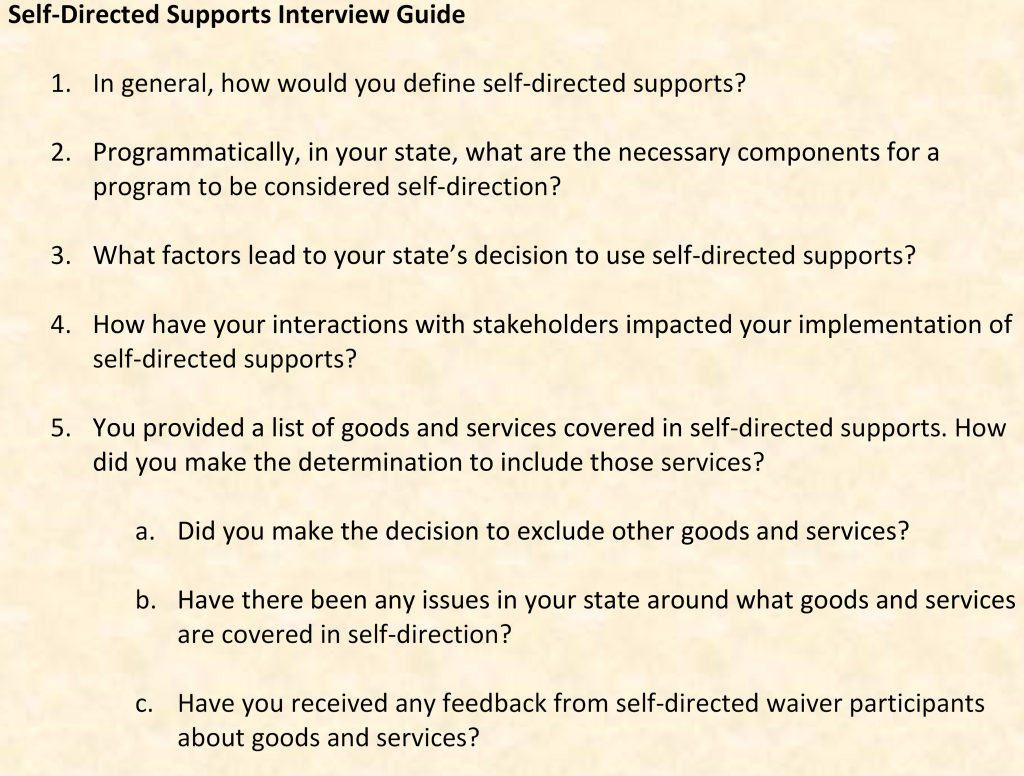

Semi-structured interviews lie between structured and unstructured interviews. The interviewer prepares a set of same questions to be answered by all interviewees. Additional questions might be asked during the interview to clarify or expand certain issues.

In semi-structured interviews, the interviewer has more freedom to digress and probe beyond the answers. The interview guide contains a list of questions and topics that need to be covered during the conversation, usually in a particular order.

Semi-structured interviews are most useful to address the ‘what’, ‘how’, and ‘why’ research questions. Both qualitative and quantitative analyses can be performed on data collected during semi-structured interviews.

- Semi-structured interviews allow respondents to answer more on their terms in an informal setting yet provide uniform information making them ideal for qualitative analysis.

- The flexible nature of semi-structured interviews allows ideas to be introduced and explored during the interview based on the respondents’ answers.

- Semi-structured interviews can provide reliable and comparable qualitative data. Allows the interviewer to probe answers, where the interviewee is asked to clarify or expand on the answers provided.

- The data generated remain fundamentally shaped by the interview context itself. Analysis rarely acknowledges this endemic co-construction.

- They are more time-consuming (to conduct, transcribe, and analyze) than structured interviews.

- The quality of findings is more dependent on the individual skills of the interviewer than in structured interviews. Skill is required to probe effectively while avoiding biasing responses.

The Interviewer Effect

Face-to-face interviews raise methodological problems. These stem from the fact that interviewers are themselves role players, and their perceived status may influence the replies of the respondents.

Because an interview is a social interaction, the interviewer’s appearance or behavior may influence the respondent’s answers. This is a problem as it can bias the results of the study and make them invalid.

For example, the gender, ethnicity, body language, age, and social status of the interview can all create an interviewer effect. If there is a perceived status disparity between the interviewer and the interviewee, the results of interviews have to be interpreted with care. This is pertinent for sensitive topics such as health.

For example, if a researcher was investigating sexism amongst males, would a female interview be preferable to a male? It is possible that if a female interviewer was used, male participants might lie (i.e., pretend they are not sexist) to impress the interviewer, thus creating an interviewer effect.

Flooding interviews with researcher’s agenda

The interactional nature of interviews means the researcher fundamentally shapes the discourse, rather than just neutrally collecting it. This shapes what is talked about and how participants can respond.

- The interviewer’s assumptions, interests, and categories don’t just shape the specific interview questions asked. They also shape the framing, task instructions, recruitment, and ongoing responses/prompts.

- This flooding of the interview interaction with the researcher’s agenda makes it very difficult to separate out what comes from the participant vs. what is aligned with the interviewer’s concerns.

- So the participant’s talk ends up being fundamentally shaped by the interviewer rather than being a more natural reflection of the participant’s own orientations or practices.

- This effect is hard to avoid because interviews inherently involve the researcher setting an agenda. But it does mean the talk extracted may say more about the interview process than the reality it is supposed to reflect.

Interview Design

First, you must choose whether to use a structured or non-structured interview.

Characteristics of Interviewers

Next, you must consider who will be the interviewer, and this will depend on what type of person is being interviewed. There are several variables to consider:

- Gender and age : This can greatly affect respondents’ answers, particularly on personal issues.

- Personal characteristics : Some people are easier to get on with than others. Also, the interviewer’s accent and appearance (e.g., clothing) can affect the rapport between the interviewer and interviewee.

- Language : The interviewer’s language should be appropriate to the vocabulary of the group of people being studied. For example, the researcher must change the questions’ language to match the respondents’ social background” age / educational level / social class/ethnicity, etc.

- Ethnicity : People may have difficulty interviewing people from different ethnic groups.

- Interviewer expertise should match research sensitivity – inexperienced students should avoid interviewing highly vulnerable groups.

Interview Location

The location of a research interview can influence the way in which the interviewer and interviewee relate and may exaggerate a power dynamic in one direction or another. It is usual to offer interviewees a choice of location as part of facilitating their comfort and encouraging participation.

However, the safety of the interviewer is an overriding consideration and, as mentioned, a minimal requirement should be that a responsible person knows where the interviewer has gone and when they are due back.

Remote Interviews

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated remote interviewing for research continuity. However online interview platforms provide increased flexibility even under normal conditions.

They enable access to participant groups across geographical distances without travel costs or arrangements. Online interviews can be efficiently scheduled to align with researcher and interviewee availability.

There are practical considerations in setting up remote interviews. Interviewees require access to internet and an online platform such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams or Skype through which to connect.

Certain modifications help build initial rapport in the remote format. Allowing time at the start of the interview for casual conversation while testing audio/video quality helps participants settle in. Minor delays can disrupt turn-taking flow, so alerting participants to speak slightly slower than usual minimizes accidental interruptions.

Keeping remote interviews under an hour avoids fatigue for stare at a screen. Seeking advanced ethical clearance for verbal consent at the interview start saves participant time. Adapting to the remote context shows care for interviewees and aids rich discussion.

However, it remains important to critically reflect on how removing in-person dynamics may shape the co-created data. Perhaps some nuances of trust and disclosure differ over video.

Vulnerable Groups

The interviewer must ensure that they take special care when interviewing vulnerable groups, such as children. For example, children have a limited attention span, so lengthy interviews should be avoided.

Developing an Interview Schedule

An interview schedule is a list of pre-planned, structured questions that have been prepared, to serve as a guide for interviewers, researchers and investigators in collecting information or data about a specific topic or issue.

- List the key themes or topics that must be covered to address your research questions. This will form the basic content.

- Organize the content logically, such as chronologically following the interviewee’s experiences. Place more sensitive topics later in the interview.

- Develop the list of content into actual questions and prompts. Carefully word each question – keep them open-ended, non-leading, and focused on examples.

- Add prompts to remind you to cover areas of interest.

- Pilot test the interview schedule to check it generates useful data and revise as needed.

- Be prepared to refine the schedule throughout data collection as you learn which questions work better.

- Practice skills like asking follow-up questions to get depth and detail. Stay flexible to depart from the schedule when needed.

- Keep questions brief and clear. Avoid multi-part questions that risk confusing interviewees.

- Listen actively during interviews to determine which pre-planned questions can be skipped based on information the participant has already provided.

The key is balancing preparation with the flexibility to adapt questions based on each interview interaction. With practice, you’ll gain skills to conduct productive interviews that obtain rich qualitative data.

The Power of Silence

Strategic use of silence is a key technique to generate interviewee-led data, but it requires judgment about appropriate timing and duration to maintain mutual understanding.

- Unlike ordinary conversation, the interviewer aims to facilitate the interviewee’s contribution without interrupting. This often means resisting the urge to speak at the end of the interviewee’s turn construction units (TCUs).

- Leaving a silence after a TCU encourages the interviewee to provide more material without being led by the interviewer. However, this simple technique requires confidence, as silence can feel socially awkward.

- Allowing longer silences (e.g. 24 seconds) later in interviews can work well, but early on even short silences may disrupt rapport if they cause misalignment between speakers.

- Silence also allows interviewees time to think before answering. Rushing to re-ask or amend questions can limit responses.

- Blunt backchannels like “mm hm” also avoid interrupting flow. Interruptions, especially to finish an interviewee’s turn, are problematic as they make the ownership of perspectives unclear.

- If interviewers incorrectly complete turns, an upside is it can produce extended interviewee narratives correcting the record. However, silence would have been better to let interviewees shape their own accounts.

Recording & Transcription

Design choices.

Design choices around recording and engaging closely with transcripts influence analytic insights, as well as practical feasibility. Weighing up relevant tradeoffs is key.

- Audio recording is standard, but video better captures contextual details, which is useful for some topics/analysis approaches. Participants may find video invasive for sensitive research.

- Digital formats enable the sharing of anonymized clips. Additional microphones reduce audio issues.

- Doing all transcription is time-consuming. Outsourcing can save researcher effort but needs confidentiality assurances. Always carefully check outsourced transcripts.

- Online platform auto-captioning can facilitate rapid analysis, but accuracy limitations mean full transcripts remain ideal. Software cleans up caption file formatting.

- Verbatim transcripts best capture nuanced meaning, but the level of detail needed depends on the analysis approach. Referring back to recordings is still advisable during analysis.

- Transcripts versus recordings highlight different interaction elements. Transcripts make overt disagreements clearer through the wording itself. Recordings better convey tone affiliativeness.

Transcribing Interviews & Focus Groups

Here are the steps for transcribing interviews:

- Play back audio/video files to develop an overall understanding of the interview

- Format the transcription document:

- Add line numbers

- Separate interviewer questions and interviewee responses

- Use formatting like bold, italics, etc. to highlight key passages

- Provide sentence-level clarity in the interviewee’s responses while preserving their authentic voice and word choices

- Break longer passages into smaller paragraphs to help with coding

- If translating the interview to another language, use qualified translators and back-translate where possible

- Select a notation system to indicate pauses, emphasis, laughter, interruptions, etc., and adapt it as needed for your data

- Insert screenshots, photos, or documents discussed in the interview at the relevant point in the transcript

- Read through multiple times, revising formatting and notations

- Double-check the accuracy of transcription against audio/videos

- De-identify transcript by removing identifying participant details

The goal is to produce a formatted written record of the verbal interview exchange that captures the meaning and highlights important passages ready for the coding process. Careful transcription is the vital first step in analysis.

Coding Transcripts

The goal of transcription and coding is to systematically transform interview responses into a set of codes and themes that capture key concepts, experiences and beliefs expressed by participants. Taking care with transcription and coding procedures enhances the validity of qualitative analysis .

- Read through the transcript multiple times to become immersed in the details

- Identify manifest/obvious codes and latent/underlying meaning codes

- Highlight insightful participant quotes that capture key concepts (in vivo codes)

- Create a codebook to organize and define codes with examples

- Use an iterative cycle of inductive (data-driven) coding and deductive (theory-driven) coding

- Refine codebook with clear definitions and examples as you code more transcripts

- Collaborate with other coders to establish the reliability of codes

Ethical Issues

Informed consent.

The participant information sheet must give potential interviewees a good idea of what is involved if taking part in the research.

This will include the general topics covered in the interview, where the interview might take place, how long it is expected to last, how it will be recorded, the ways in which participants’ anonymity will be managed, and incentives offered.

It might be considered good practice to consider true informed consent in interview research to require two distinguishable stages:

- Consent to undertake and record the interview and

- Consent to use the material in research after the interview has been conducted and the content known, or even after the interviewee has seen a copy of the transcript and has had a chance to remove sections, if desired.

Power and Vulnerability

- Early feminist views that sensitivity could equalize power differences are likely naive. The interviewer and interviewee inhabit different knowledge spheres and social categories, indicating structural disparities.

- Power fluctuates within interviews. Researchers rely on participation, yet interviewees control openness and can undermine data collection. Assumptions should be avoided.

- Interviews on sensitive topics may feel like quasi-counseling. Interviewers must refrain from dual roles, instead supplying support service details to all participants.

- Interviewees recruited for trauma experiences may reveal more than anticipated. While generating analytic insights, this risks leaving them feeling exposed.

- Ultimately, power balances resist reconciliation. But reflexively analyzing operations of power serves to qualify rather than nullify situtated qualitative accounts.

Some groups, like those with mental health issues, extreme views, or criminal backgrounds, risk being discredited – treated skeptically by researchers.

This creates tensions with qualitative approaches, often having an empathetic ethos seeking to center subjective perspectives. Analysis should balance openness to offered accounts with critically examining stakes and motivations behind them.

Potter, J., & Hepburn, A. (2005). Qualitative interviews in psychology: Problems and possibilities. Qualitative research in Psychology , 2 (4), 281-307.

Houtkoop-Steenstra, H. (2000). Interaction and the standardized survey interview: The living questionnaire . Cambridge University Press

Madill, A. (2011). Interaction in the semi-structured interview: A comparative analysis of the use of and response to indirect complaints. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 8 (4), 333–353.

Maryudi, A., & Fisher, M. (2020). The power in the interview: A practical guide for identifying the critical role of actor interests in environment research. Forest and Society, 4 (1), 142–150

O’Key, V., Hugh-Jones, S., & Madill, A. (2009). Recruiting and engaging with people in deprived locales: Interviewing families about their eating patterns. Social Psychological Review, 11 (20), 30–35.

Puchta, C., & Potter, J. (2004). Focus group practice . Sage.

Schaeffer, N. C. (1991). Conversation with a purpose— Or conversation? Interaction in the standardized interview. In P. P. Biemer, R. M. Groves, L. E. Lyberg, & N. A. Mathiowetz (Eds.), Measurement errors in surveys (pp. 367–391). Wiley.

Silverman, D. (1973). Interview talk: Bringing off a research instrument. Sociology, 7 (1), 31–48.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Published on March 10, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

An interview is a qualitative research method that relies on asking questions in order to collect data . Interviews involve two or more people, one of whom is the interviewer asking the questions.

There are several types of interviews, often differentiated by their level of structure.

- Structured interviews have predetermined questions asked in a predetermined order.

- Unstructured interviews are more free-flowing.

- Semi-structured interviews fall in between.

Interviews are commonly used in market research, social science, and ethnographic research .

Table of contents

What is a structured interview, what is a semi-structured interview, what is an unstructured interview, what is a focus group, examples of interview questions, advantages and disadvantages of interviews, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about types of interviews.

Structured interviews have predetermined questions in a set order. They are often closed-ended, featuring dichotomous (yes/no) or multiple-choice questions. While open-ended structured interviews exist, they are much less common. The types of questions asked make structured interviews a predominantly quantitative tool.

Asking set questions in a set order can help you see patterns among responses, and it allows you to easily compare responses between participants while keeping other factors constant. This can mitigate research biases and lead to higher reliability and validity. However, structured interviews can be overly formal, as well as limited in scope and flexibility.

- You feel very comfortable with your topic. This will help you formulate your questions most effectively.

- You have limited time or resources. Structured interviews are a bit more straightforward to analyze because of their closed-ended nature, and can be a doable undertaking for an individual.

- Your research question depends on holding environmental conditions between participants constant.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Semi-structured interviews are a blend of structured and unstructured interviews. While the interviewer has a general plan for what they want to ask, the questions do not have to follow a particular phrasing or order.

Semi-structured interviews are often open-ended, allowing for flexibility, but follow a predetermined thematic framework, giving a sense of order. For this reason, they are often considered “the best of both worlds.”

However, if the questions differ substantially between participants, it can be challenging to look for patterns, lessening the generalizability and validity of your results.

- You have prior interview experience. It’s easier than you think to accidentally ask a leading question when coming up with questions on the fly. Overall, spontaneous questions are much more difficult than they may seem.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. The answers you receive can help guide your future research.

An unstructured interview is the most flexible type of interview. The questions and the order in which they are asked are not set. Instead, the interview can proceed more spontaneously, based on the participant’s previous answers.

Unstructured interviews are by definition open-ended. This flexibility can help you gather detailed information on your topic, while still allowing you to observe patterns between participants.

However, so much flexibility means that they can be very challenging to conduct properly. You must be very careful not to ask leading questions, as biased responses can lead to lower reliability or even invalidate your research.

- You have a solid background in your research topic and have conducted interviews before.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking descriptive data that will deepen and contextualize your initial hypotheses.

- Your research necessitates forming a deeper connection with your participants, encouraging them to feel comfortable revealing their true opinions and emotions.

A focus group brings together a group of participants to answer questions on a topic of interest in a moderated setting. Focus groups are qualitative in nature and often study the group’s dynamic and body language in addition to their answers. Responses can guide future research on consumer products and services, human behavior, or controversial topics.

Focus groups can provide more nuanced and unfiltered feedback than individual interviews and are easier to organize than experiments or large surveys . However, their small size leads to low external validity and the temptation as a researcher to “cherry-pick” responses that fit your hypotheses.

- Your research focuses on the dynamics of group discussion or real-time responses to your topic.

- Your questions are complex and rooted in feelings, opinions, and perceptions that cannot be answered with a “yes” or “no.”

- Your topic is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking information that will help you uncover new questions or future research ideas.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Depending on the type of interview you are conducting, your questions will differ in style, phrasing, and intention. Structured interview questions are set and precise, while the other types of interviews allow for more open-endedness and flexibility.

Here are some examples.

- Semi-structured

- Unstructured

- Focus group

- Do you like dogs? Yes/No

- Do you associate dogs with feeling: happy; somewhat happy; neutral; somewhat unhappy; unhappy

- If yes, name one attribute of dogs that you like.

- If no, name one attribute of dogs that you don’t like.

- What feelings do dogs bring out in you?

- When you think more deeply about this, what experiences would you say your feelings are rooted in?

Interviews are a great research tool. They allow you to gather rich information and draw more detailed conclusions than other research methods, taking into consideration nonverbal cues, off-the-cuff reactions, and emotional responses.

However, they can also be time-consuming and deceptively challenging to conduct properly. Smaller sample sizes can cause their validity and reliability to suffer, and there is an inherent risk of interviewer effect arising from accidentally leading questions.

Here are some advantages and disadvantages of each type of interview that can help you decide if you’d like to utilize this research method.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, but other questions aren’t planned.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.

- Focus group interviews : The questions are presented to a group instead of one individual.

The interviewer effect is a type of bias that emerges when a characteristic of an interviewer (race, age, gender identity, etc.) influences the responses given by the interviewee.

There is a risk of an interviewer effect in all types of interviews , but it can be mitigated by writing really high-quality interview questions.

Social desirability bias is the tendency for interview participants to give responses that will be viewed favorably by the interviewer or other participants. It occurs in all types of interviews and surveys , but is most common in semi-structured interviews , unstructured interviews , and focus groups .

Social desirability bias can be mitigated by ensuring participants feel at ease and comfortable sharing their views. Make sure to pay attention to your own body language and any physical or verbal cues, such as nodding or widening your eyes.

This type of bias can also occur in observations if the participants know they’re being observed. They might alter their behavior accordingly.

A focus group is a research method that brings together a small group of people to answer questions in a moderated setting. The group is chosen due to predefined demographic traits, and the questions are designed to shed light on a topic of interest. It is one of 4 types of interviews .

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/interviews-research/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, unstructured interview | definition, guide & examples, structured interview | definition, guide & examples, semi-structured interview | definition, guide & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Search form

You are here.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Qualitative Interviews

As the preceding sections have suggested, qualitative interviews are an excellent way to gather detailed information. Whatever topic is of interest to the researcher employing this method can be explored in much more depth than with almost any other method. Not only are participants given the opportunity to elaborate in a way that is not possible with other methods such as survey research, but they also are able share information with researchers in their own words and from their own perspectives rather than being asked to fit those perspectives into the perhaps limited response options provided by the researcher. And because qualitative interviews are designed to elicit detailed information, they are especially useful when a researcher’s aim is to study social processes, or the “how” of various phenomena. Yet another, and sometimes overlooked, benefit of qualitative interviews that occurs in person is that researchers can make observations beyond those that a respondent is orally reporting. A respondent’s body language, and even her or his choice of time and location for the interview, might provide a researcher with useful data.

Of course, all these benefits do not come without some drawbacks. As with quantitative survey research, qualitative interviews rely on respondents’ ability to accurately and honestly recall whatever details about their lives, circumstances, thoughts, opinions, or behaviors that are being asked about. As Esterberg (2002) puts it, “If you want to know about what people actually do, rather than what they say they do, you should probably use observation [instead of interviews].” 1 Further, as you may have already guessed, qualitative interviewing is time intensive and can be quite expensive. Creating an interview guide, identifying a sample, and conducting interviews are just the beginning. Transcribing interviews is labor intensive—and that’s before coding even begins. It is also not uncommon to offer respondents some monetary incentive or thank-you for participating. Keep in mind that you are asking for more of participants’ time than if you’d simply mailed them a questionnaire containing closed-ended questions. Conducting qualitative interviews is not only labor intensive but also emotionally taxing. When I interviewed young workers about their sexual harassment experiences, I heard stories that were shocking, infuriating, and sad. Seeing and hearing the impact that harassment had had on respondents was difficult. Researchers embarking on a qualitative interview project should keep in mind their own abilities to hear stories that may be difficult to hear.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- In-depth interviews are semi-structured interviews where the researcher has topics and questions in mind to ask, but questions are open ended and flow according to how the participant responds to each.

- Interview guides can vary in format but should contain some outline of the topics you hope to cover during the course of an interview.

- NVivo and Atlasti are computer programs that qualitative researchers use to help them with organizing, sorting, and analyzing their data.

- Qualitative interviews allow respondents to share information in their own words and are useful for gathering detailed information and understanding social processes.

- Drawbacks of qualitative interviews include reliance on respondents’ accuracy and their intensity in terms of time, expense, and possible emotional strain.

- Based on a research question you have identified through earlier exercises in this text, write a few open-ended questions you could ask were you to conduct in-depth interviews on the topic. Now critique your questions. Are any of them yes/no questions? Are any of them leading?

- Read the open-ended questions you just created, and answer them as though you were an interview participant. Were your questions easy to answer or fairly difficult? How did you feel talking about the topics you asked yourself to discuss? How might respondents feel talking about them?

- 90747 reads

- Relevance, Balance, and Accessibility

- Different Sources of Knowledge

- Ontology and Epistemology KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- The Science of Sociology

- Specific Considerations for the Social Sciences KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Consuming Research and Living With Its Results

- Research as Employment Opportunity KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Design and Goals of This Text LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE

- Sociology at Three Different Levels KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Paradigms in Social Science

- Sociological Theories KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Inductive Approaches and Some Examples

- Deductive Approaches and Some Examples

- Complementary Approaches? KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Revisiting an Earlier Question LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE

- Human Research Versus Nonhuman Research

- A Historical Look at Research on Humans

- Institutional Review Boards KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Informed Consent

- Protection of Identities

- Disciplinary Considerations KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Ethics at Micro, Meso, and Macro Levels LEARNING OBJECTIVE KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Doing Science the Ethical Way

- Using Science the Ethical Way KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- How Do You Feel About Where You Already Are?

- What Do You Know About Where You Already Are? KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Is It Empirical? LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- What Is Sociology?

- What Is Not Sociology? KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Sociologists as Paparazzi?

- Some Specific Examples KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Feasibility

- Field Trip: Visit Your Library KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Exploration, Description, Explanation

- Idiographic or Nomothetic?

- Applied or Basic? KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Units of Analysis and Units of Observation

- Hypotheses KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Triangulation LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Searching for Literature

- Reviewing the Literature

- Additional Important Components KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- What Do Social Scientists Measure?

- How Do Social Scientists Measure? KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE

- Concepts and Conceptualization

- A Word of Caution About Conceptualization KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Putting It All Together KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE

- Reliability

- Validity KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Levels of Measurement

- Indexes, Scales, and Typologies KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Populations Versus Samples LEARNING OBJECTIVE KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Nonprobability Sampling

- Types of Nonprobability Samples KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Probability Sampling

- Types of Probability Samples KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Who Sampled, How Sampled, and for What Purpose? KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Survey Research: What Is It and When Should It Be Used? LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAY EXERCISE

- Strengths of Survey Method

- Weaknesses of Survey Method KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Administration KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Asking Effective Questions

- Response Options

- Designing Questionnaires KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- From Completed Questionnaires to Analyzable Data

- Identifying Patterns KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Interview Research: What Is It and When Should It Be Used? LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE

- Conducting Qualitative Interviews

- Analysis of Qualitative Interview Data

- Strengths and Weaknesses of Qualitative Interviews KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Conducting Quantitative Interviews

- Analysis of Quantitative Interview Data

- Strengths and Weaknesses of Quantitative Interviews KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Location, Location, Location

- Researcher-Respondent Relationship KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Field Research: What Is It and When to Use It? LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Strengths of Field Research

- Weaknesses of Field Research KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Choosing a Site

- Choosing a Role KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Writing in the Field

- Writing out of the Field KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE

- From Description to Analysis KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE

- Unobtrusive Research: What Is It and When to Use It? LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Strengths of Unobtrusive Research

- Weaknesses of Unobtrusive Research KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Content Analysis

- Indirect Measures

- Analysis of Unobtrusive Data Collected by You KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Analyzing Others’ Data LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Reliability in Unobtrusive Research LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE

- Focus Groups LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Experiments LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE

- Sharing It All: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

- Knowing Your Audience KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE

- Presenting Your Research LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Writing Up Research Results LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Disseminating Findings LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Reading Reports of Sociological Research LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Being a Responsible Consumer of Research LEARNING OBJECTIVE KEY TAKEAWAY EXERCISE

- Media Reports of Sociological Research LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Sociological Research: It’s Everywhere LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE

- Evaluation Research

- Market Research

- Policy and Other Government Research KEY TAKEAWAY EXERCISE

- Doing Research for a Cause LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE

- Public Sociology LEARNING OBJECTIVE KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Transferable Skills

- Understanding Yourself, Your Circumstances, and Your World KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES

- Back Matter

This action cannot be undo.

Choose a delete action Empty this page Remove this page and its subpages

Content is out of sync. You must reload the page to continue.

New page type Book Topic Interactive Learning Content

- Config Page

- Add Page Before

- Add Page After

- Delete Page

Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences pp 391–410 Cite as

Qualitative Interviewing

- Sally Nathan 2 ,

- Christy Newman 3 &

- Kari Lancaster 3

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 13 January 2019

3937 Accesses

20 Citations

8 Altmetric

Qualitative interviewing is a foundational method in qualitative research and is widely used in health research and the social sciences. Both qualitative semi-structured and in-depth unstructured interviews use verbal communication, mostly in face-to-face interactions, to collect data about the attitudes, beliefs, and experiences of participants. Interviews are an accessible, often affordable, and effective method to understand the socially situated world of research participants. The approach is typically informed by an interpretive framework where the data collected is not viewed as evidence of the truth or reality of a situation or experience but rather a context-bound subjective insight from the participants. The researcher needs to be open to new insights and to privilege the participant’s experience in data collection. The data from qualitative interviews is not generalizable, but its exploratory nature permits the collection of rich data which can answer questions about which little is already known. This chapter introduces the reader to qualitative interviewing, the range of traditions within which interviewing is utilized as a method, and highlights the advantages and some of the challenges and misconceptions in its application. The chapter also provides practical guidance on planning and conducting interview studies. Three case examples are presented to highlight the benefits and risks in the use of interviewing with different participants, providing situated insights as well as advice about how to go about learning to interview if you are a novice.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Baez B. Confidentiality in qualitative research: reflections on secrets, power and agency. Qual Res. 2002;2(1):35–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794102002001638 .

Article Google Scholar

Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. London: Sage Publications; 2013.

Google Scholar

Braun V, Clarke V, Gray D. Collecting qualitative data: a practical guide to textual, media and virtual techniques. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

Book Google Scholar

Bryman A. Social research methods. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016.

Crotty M. The foundations of social research: meaning and perspective in the research process. Australia: Allen & Unwin; 1998.

Davies MB. Doing a successful research project: using qualitative or quantitative methods. New York: Palgrave MacMillan; 2007.

Dickson-Swift V, James EL, Liamputtong P. Undertaking sensitive research in the health and social sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Foster M, Nathan S, Ferry M. The experience of drug-dependent adolescents in a therapeutic community. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(5):531–9.

Gillham B. The research interview. London: Continuum; 2000.

Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967.

Hesse-Biber SN, Leavy P. In-depth interview. In: The practice of qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2011. p. 119–47

Irvine A. Duration, dominance and depth in telephone and face-to-face interviews: a comparative exploration. Int J Qual Methods. 2011;10(3):202–20.

Johnson JM. In-depth interviewing. In: Gubrium JF, Holstein JA, editors. Handbook of interview research: context and method. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2001.

Kvale S. Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1996.

Kvale S. Doing interviews. London: Sage Publications; 2007.

Lancaster K. Confidentiality, anonymity and power relations in elite interviewing: conducting qualitative policy research in a politicised domain. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2017;20(1):93–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2015.1123555 .

Leavy P. Method meets art: arts-based research practice. New York: Guilford Publications; 2015.

Liamputtong P. Researching the vulnerable: a guide to sensitive research methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2007.

Liamputtong P. Qualitative research methods. 4th ed. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2013.

Mays N, Pope C. Quality in qualitative health research. In: Pope C, Mays N, editors. Qualitative research in health care. London: BMJ Books; 2000. p. 89–102.

McLellan E, MacQueen KM, Neidig JL. Beyond the qualitative interview: data preparation and transcription. Field Methods. 2003;15(1):63–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x02239573 .

Minichiello V, Aroni R, Hays T. In-depth interviewing: principles, techniques, analysis. 3rd ed. Sydney: Pearson Education Australia; 2008.

Morris ZS. The truth about interviewing elites. Politics. 2009;29(3):209–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.2009.01357.x .

Nathan S, Foster M, Ferry M. Peer and sexual relationships in the experience of drug-dependent adolescents in a therapeutic community. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011;30(4):419–27.

National Health and Medical Research Council. National statement on ethical conduct in human research. Canberra: Australian Government; 2007.

Neal S, McLaughlin E. Researching up? Interviews, emotionality and policy-making elites. J Soc Policy. 2009;38(04):689–707. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279409990018 .

O’Reilly M, Parker N. ‘Unsatisfactory saturation’: a critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qual Res. 2013;13(2):190–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112446106 .

Ostrander S. “Surely you're not in this just to be helpful”: access, rapport and interviews in three studies of elites. In: Hertz R, Imber J, editors. Studying elites using qualitative methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1995. p. 133–50.

Chapter Google Scholar

Patton M. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2015.

Punch KF. Introduction to social research: quantitative and qualitative approaches. London: Sage; 2005.

Rhodes T, Bernays S, Houmoller K. Parents who use drugs: accounting for damage and its limitation. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(8):1489–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.028 .

Riessman CK. Narrative analysis. London: Sage; 1993.

Ritchie J. Not everything can be reduced to numbers. In: Berglund C, editor. Health research. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2001. p. 149–73.

Rubin H, Rubin I. Qualitative interviewing: the art of hearing data. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2012.

Serry T, Liamputtong P. The in-depth interviewing method in health. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Research methods in health: foundations for evidence-based practice. 3rd ed. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2017. p. 67–83.

Silverman D. Doing qualitative research. 5th ed. London: Sage; 2017.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (coreq): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Public Health and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, UNSW, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Sally Nathan

Centre for Social Research in Health, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, UNSW, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Christy Newman & Kari Lancaster

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sally Nathan .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Pranee Liamputtong

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Nathan, S., Newman, C., Lancaster, K. (2019). Qualitative Interviewing. In: Liamputtong, P. (eds) Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_77

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_77

Published : 13 January 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-10-5250-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-10-5251-4

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Qualitative Data Collection & Analysis Methods

59 Strengths and Weaknesses of Qualitative Interviews

As the preceding sections have suggested, qualitative interviews are an excellent way to gather detailed information. Whatever topic is of interest to the researcher employing this method can be explored in much more depth than with almost any other method. Not only are participants given the opportunity to elaborate in a way that is not possible with other methods such as survey research, but they also are able share information with researchers in their own words and from their own perspectives rather than being asked to fit those perspectives into the perhaps limited response options provided by the researcher. And because qualitative interviews are designed to elicit detailed information, they are especially useful when a researcher’s aim is to study social processes, or the “how” of various phenomena. Yet another, and sometimes overlooked, benefit of qualitative interviews that occurs in person is that researchers can make observations beyond those that a respondent is orally reporting. A respondent’s body language, and even her or his choice of time and location for the interview, might provide a researcher with useful data.

Of course, all these benefits do not come without some drawbacks. As with quantitative survey research, qualitative interviews rely on respondents’ ability to accurately and honestly recall whatever details about their lives, circumstances, thoughts, opinions, or behaviours are being asked about. Further, as you may have already guessed, qualitative interviewing is time intensive and can be quite expensive. Creating an interview guide, identifying a sample, and conducting interviews are just the beginning. Transcribing interviews is labour intensive—and that is before coding even begins. It is also not uncommon to offer respondents some monetary incentive or thank-you for participating. Keep in mind that you are asking for more of the participants’ time than if you would have simply mailed them a questionnaire containing closed-ended questions. Conducting qualitative interviews is not only labour intensive but also emotionally taxing. Researchers embarking on a qualitative interview project, with a subject that is sensitive in nature, should keep in mind their own abilities to listen to stories that may be difficult to hear.

Text Attributions

- This chapter is an adaptation of Chapter 9.2 in Principles of Sociological Inquiry , which was adapted by the Saylor Academy without attribution to the original authors or publisher, as requested by the licensor. © Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License .

An Introduction to Research Methods in Sociology Copyright © 2019 by Valerie A. Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 05 October 2018

Interviews and focus groups in qualitative research: an update for the digital age

- P. Gill 1 &

- J. Baillie 2

British Dental Journal volume 225 , pages 668–672 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

25k Accesses

48 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

Highlights that qualitative research is used increasingly in dentistry. Interviews and focus groups remain the most common qualitative methods of data collection.

Suggests the advent of digital technologies has transformed how qualitative research can now be undertaken.

Suggests interviews and focus groups can offer significant, meaningful insight into participants' experiences, beliefs and perspectives, which can help to inform developments in dental practice.

Qualitative research is used increasingly in dentistry, due to its potential to provide meaningful, in-depth insights into participants' experiences, perspectives, beliefs and behaviours. These insights can subsequently help to inform developments in dental practice and further related research. The most common methods of data collection used in qualitative research are interviews and focus groups. While these are primarily conducted face-to-face, the ongoing evolution of digital technologies, such as video chat and online forums, has further transformed these methods of data collection. This paper therefore discusses interviews and focus groups in detail, outlines how they can be used in practice, how digital technologies can further inform the data collection process, and what these methods can offer dentistry.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Interviews in the social sciences

Eleanor Knott, Aliya Hamid Rao, … Chana Teeger

Professionalism in dentistry: deconstructing common terminology

Andrew Trathen, Sasha Scambler & Jennifer E. Gallagher

A review of technical and quality assessment considerations of audio-visual and web-conferencing focus groups in qualitative health research

Hiba Bawadi, Sara Elshami, … Banan Mukhalalati

Introduction

Traditionally, research in dentistry has primarily been quantitative in nature. 1 However, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in qualitative research within the profession, due to its potential to further inform developments in practice, policy, education and training. Consequently, in 2008, the British Dental Journal (BDJ) published a four paper qualitative research series, 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 to help increase awareness and understanding of this particular methodological approach.

Since the papers were originally published, two scoping reviews have demonstrated the ongoing proliferation in the use of qualitative research within the field of oral healthcare. 1 , 6 To date, the original four paper series continue to be well cited and two of the main papers remain widely accessed among the BDJ readership. 2 , 3 The potential value of well-conducted qualitative research to evidence-based practice is now also widely recognised by service providers, policy makers, funding bodies and those who commission, support and use healthcare research.

Besides increasing standalone use, qualitative methods are now also routinely incorporated into larger mixed method study designs, such as clinical trials, as they can offer additional, meaningful insights into complex problems that simply could not be provided by quantitative methods alone. Qualitative methods can also be used to further facilitate in-depth understanding of important aspects of clinical trial processes, such as recruitment. For example, Ellis et al . investigated why edentulous older patients, dissatisfied with conventional dentures, decline implant treatment, despite its established efficacy, and frequently refuse to participate in related randomised clinical trials, even when financial constraints are removed. 7 Through the use of focus groups in Canada and the UK, the authors found that fears of pain and potential complications, along with perceived embarrassment, exacerbated by age, are common reasons why older patients typically refuse dental implants. 7

The last decade has also seen further developments in qualitative research, due to the ongoing evolution of digital technologies. These developments have transformed how researchers can access and share information, communicate and collaborate, recruit and engage participants, collect and analyse data and disseminate and translate research findings. 8 Where appropriate, such technologies are therefore capable of extending and enhancing how qualitative research is undertaken. 9 For example, it is now possible to collect qualitative data via instant messaging, email or online/video chat, using appropriate online platforms.

These innovative approaches to research are therefore cost-effective, convenient, reduce geographical constraints and are often useful for accessing 'hard to reach' participants (for example, those who are immobile or socially isolated). 8 , 9 However, digital technologies are still relatively new and constantly evolving and therefore present a variety of pragmatic and methodological challenges. Furthermore, given their very nature, their use in many qualitative studies and/or with certain participant groups may be inappropriate and should therefore always be carefully considered. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a detailed explication regarding the use of digital technologies in qualitative research, insight is provided into how such technologies can be used to facilitate the data collection process in interviews and focus groups.

In light of such developments, it is perhaps therefore timely to update the main paper 3 of the original BDJ series. As with the previous publications, this paper has been purposely written in an accessible style, to enhance readability, particularly for those who are new to qualitative research. While the focus remains on the most common qualitative methods of data collection – interviews and focus groups – appropriate revisions have been made to provide a novel perspective, and should therefore be helpful to those who would like to know more about qualitative research. This paper specifically focuses on undertaking qualitative research with adult participants only.

Overview of qualitative research

Qualitative research is an approach that focuses on people and their experiences, behaviours and opinions. 10 , 11 The qualitative researcher seeks to answer questions of 'how' and 'why', providing detailed insight and understanding, 11 which quantitative methods cannot reach. 12 Within qualitative research, there are distinct methodologies influencing how the researcher approaches the research question, data collection and data analysis. 13 For example, phenomenological studies focus on the lived experience of individuals, explored through their description of the phenomenon. Ethnographic studies explore the culture of a group and typically involve the use of multiple methods to uncover the issues. 14

While methodology is the 'thinking tool', the methods are the 'doing tools'; 13 the ways in which data are collected and analysed. There are multiple qualitative data collection methods, including interviews, focus groups, observations, documentary analysis, participant diaries, photography and videography. Two of the most commonly used qualitative methods are interviews and focus groups, which are explored in this article. The data generated through these methods can be analysed in one of many ways, according to the methodological approach chosen. A common approach is thematic data analysis, involving the identification of themes and subthemes across the data set. Further information on approaches to qualitative data analysis has been discussed elsewhere. 1

Qualitative research is an evolving and adaptable approach, used by different disciplines for different purposes. Traditionally, qualitative data, specifically interviews, focus groups and observations, have been collected face-to-face with participants. In more recent years, digital technologies have contributed to the ongoing evolution of qualitative research. Digital technologies offer researchers different ways of recruiting participants and collecting data, and offer participants opportunities to be involved in research that is not necessarily face-to-face.

Research interviews are a fundamental qualitative research method 15 and are utilised across methodological approaches. Interviews enable the researcher to learn in depth about the perspectives, experiences, beliefs and motivations of the participant. 3 , 16 Examples include, exploring patients' perspectives of fear/anxiety triggers in dental treatment, 17 patients' experiences of oral health and diabetes, 18 and dental students' motivations for their choice of career. 19

Interviews may be structured, semi-structured or unstructured, 3 according to the purpose of the study, with less structured interviews facilitating a more in depth and flexible interviewing approach. 20 Structured interviews are similar to verbal questionnaires and are used if the researcher requires clarification on a topic; however they produce less in-depth data about a participant's experience. 3 Unstructured interviews may be used when little is known about a topic and involves the researcher asking an opening question; 3 the participant then leads the discussion. 20 Semi-structured interviews are commonly used in healthcare research, enabling the researcher to ask predetermined questions, 20 while ensuring the participant discusses issues they feel are important.

Interviews can be undertaken face-to-face or using digital methods when the researcher and participant are in different locations. Audio-recording the interview, with the consent of the participant, is essential for all interviews regardless of the medium as it enables accurate transcription; the process of turning the audio file into a word-for-word transcript. This transcript is the data, which the researcher then analyses according to the chosen approach.

Types of interview

Qualitative studies often utilise one-to-one, face-to-face interviews with research participants. This involves arranging a mutually convenient time and place to meet the participant, signing a consent form and audio-recording the interview. However, digital technologies have expanded the potential for interviews in research, enabling individuals to participate in qualitative research regardless of location.