Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Writing Assignments

Kate Derrington; Cristy Bartlett; and Sarah Irvine

Introduction

Assignments are a common method of assessment at university and require careful planning and good quality research. Developing critical thinking and writing skills are also necessary to demonstrate your ability to understand and apply information about your topic. It is not uncommon to be unsure about the processes of writing assignments at university.

- You may be returning to study after a break

- You may have come from an exam based assessment system and never written an assignment before

- Maybe you have written assignments but would like to improve your processes and strategies

This chapter has a collection of resources that will provide you with the skills and strategies to understand assignment requirements and effectively plan, research, write and edit your assignments. It begins with an explanation of how to analyse an assignment task and start putting your ideas together. It continues by breaking down the components of academic writing and exploring the elements you will need to master in your written assignments. This is followed by a discussion of paraphrasing and synthesis, and how you can use these strategies to create a strong, written argument. The chapter concludes with useful checklists for editing and proofreading to help you get the best possible mark for your work.

Task Analysis and Deconstructing an Assignment

It is important that before you begin researching and writing your assignments you spend sufficient time understanding all the requirements. This will help make your research process more efficient and effective. Check your subject information such as task sheets, criteria sheets and any additional information that may be in your subject portal online. Seek clarification from your lecturer or tutor if you are still unsure about how to begin your assignments.

The task sheet typically provides key information about an assessment including the assignment question. It can be helpful to scan this document for topic, task and limiting words to ensure that you fully understand the concepts you are required to research, how to approach the assignment, and the scope of the task you have been set. These words can typically be found in your assignment question and are outlined in more detail in the two tables below (see Table 19.1 and Table 19.2 ).

Table 19.1 Parts of an Assignment Question

Make sure you have a clear understanding of what the task word requires you to address.

Table 19.2 Task words

The criteria sheet , also known as the marking sheet or rubric, is another important document to look at before you begin your assignment. The criteria sheet outlines how your assignment will be marked and should be used as a checklist to make sure you have included all the information required.

The task or criteria sheet will also include the:

- Word limit (or word count)

- Referencing style and research expectations

- Formatting requirements

Task analysis and criteria sheets are also discussed in the chapter Managing Assessments for a more detailed discussion on task analysis, criteria sheets, and marking rubrics.

Preparing your ideas

Brainstorm or concept map: List possible ideas to address each part of the assignment task based on what you already know about the topic from lectures and weekly readings.

Finding appropriate information: Learn how to find scholarly information for your assignments which is

See the chapter Working With Information for a more detailed explanation .

What is academic writing?

Academic writing tone and style.

Many of the assessment pieces you prepare will require an academic writing style. This is sometimes called ‘academic tone’ or ‘academic voice’. This section will help you to identify what is required when you are writing academically (see Table 19.3 ). The best way to understand what academic writing looks like, is to read broadly in your discipline area. Look at how your course readings, or scholarly sources, are written. This will help you identify the language of your discipline field, as well as how other writers structure their work.

Table 19.3 Comparison of academic and non-academic writing

Thesis statements.

Essays are a common form of assessment that you will likely encounter during your university studies. You should apply an academic tone and style when writing an essay, just as you would in in your other assessment pieces. One of the most important steps in writing an essay is constructing your thesis statement. A thesis statement tells the reader the purpose, argument or direction you will take to answer your assignment question. A thesis statement may not be relevant for some questions, if you are unsure check with your lecturer. The thesis statement:

- Directly relates to the task . Your thesis statement may even contain some of the key words or synonyms from the task description.

- Does more than restate the question.

- Is specific and uses precise language.

- Let’s your reader know your position or the main argument that you will support with evidence throughout your assignment.

- The subject is the key content area you will be covering.

- The contention is the position you are taking in relation to the chosen content.

Your thesis statement helps you to structure your essay. It plays a part in each key section: introduction, body and conclusion.

Planning your assignment structure

When planning and drafting assignments, it is important to consider the structure of your writing. Academic writing should have clear and logical structure and incorporate academic research to support your ideas. It can be hard to get started and at first you may feel nervous about the size of the task, this is normal. If you break your assignment into smaller pieces, it will seem more manageable as you can approach the task in sections. Refer to your brainstorm or plan. These ideas should guide your research and will also inform what you write in your draft. It is sometimes easier to draft your assignment using the 2-3-1 approach, that is, write the body paragraphs first followed by the conclusion and finally the introduction.

Writing introductions and conclusions

Clear and purposeful introductions and conclusions in assignments are fundamental to effective academic writing. Your introduction should tell the reader what is going to be covered and how you intend to approach this. Your conclusion should summarise your argument or discussion and signal to the reader that you have come to a conclusion with a final statement. These tips below are based on the requirements usually needed for an essay assignment, however, they can be applied to other assignment types.

Writing introductions

Most writing at university will require a strong and logically structured introduction. An effective introduction should provide some background or context for your assignment, clearly state your thesis and include the key points you will cover in the body of the essay in order to prove your thesis.

Usually, your introduction is approximately 10% of your total assignment word count. It is much easier to write your introduction once you have drafted your body paragraphs and conclusion, as you know what your assignment is going to be about. An effective introduction needs to inform your reader by establishing what the paper is about and provide four basic things:

- A brief background or overview of your assignment topic

- A thesis statement (see section above)

- An outline of your essay structure

- An indication of any parameters or scope that will/ will not be covered, e.g. From an Australian perspective.

The below example demonstrates the four different elements of an introductory paragraph.

1) Information technology is having significant effects on the communication of individuals and organisations in different professions. 2) This essay will discuss the impact of information technology on the communication of health professionals. 3) First, the provision of information technology for the educational needs of nurses will be discussed. 4) This will be followed by an explanation of the significant effects that information technology can have on the role of general practitioner in the area of public health. 5) Considerations will then be made regarding the lack of knowledge about the potential of computers among hospital administrators and nursing executives. 6) The final section will explore how information technology assists health professionals in the delivery of services in rural areas . 7) It will be argued that information technology has significant potential to improve health care and medical education, but health professionals are reluctant to use it.

1 Brief background/ overview | 2 Indicates the scope of what will be covered | 3-6 Outline of the main ideas (structure) | 7 The thesis statement

Note : The examples in this document are taken from the University of Canberra and used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 licence.

Writing conclusions

You should aim to end your assignments with a strong conclusion. Your conclusion should restate your thesis and summarise the key points you have used to prove this thesis. Finish with a key point as a final impactful statement. Similar to your introduction, your conclusion should be approximately 10% of the total assignment word length. If your assessment task asks you to make recommendations, you may need to allocate more words to the conclusion or add a separate recommendations section before the conclusion. Use the checklist below to check your conclusion is doing the right job.

Conclusion checklist

- Have you referred to the assignment question and restated your argument (or thesis statement), as outlined in the introduction?

- Have you pulled together all the threads of your essay into a logical ending and given it a sense of unity?

- Have you presented implications or recommendations in your conclusion? (if required by your task).

- Have you added to the overall quality and impact of your essay? This is your final statement about this topic; thus, a key take-away point can make a great impact on the reader.

- Remember, do not add any new material or direct quotes in your conclusion.

This below example demonstrates the different elements of a concluding paragraph.

1) It is evident, therefore, that not only do employees need to be trained for working in the Australian multicultural workplace, but managers also need to be trained. 2) Managers must ensure that effective in-house training programs are provided for migrant workers, so that they become more familiar with the English language, Australian communication norms and the Australian work culture. 3) In addition, Australian native English speakers need to be made aware of the differing cultural values of their workmates; particularly the different forms of non-verbal communication used by other cultures. 4) Furthermore, all employees must be provided with clear and detailed guidelines about company expectations. 5) Above all, in order to minimise communication problems and to maintain an atmosphere of tolerance, understanding and cooperation in the multicultural workplace, managers need to have an effective knowledge about their employees. This will help employers understand how their employee’s social conditioning affects their beliefs about work. It will develop their communication skills to develop confidence and self-esteem among diverse work groups. 6) The culturally diverse Australian workplace may never be completely free of communication problems, however, further studies to identify potential problems and solutions, as well as better training in cross cultural communication for managers and employees, should result in a much more understanding and cooperative environment.

1 Reference to thesis statement – In this essay the writer has taken the position that training is required for both employees and employers . | 2-5 Structure overview – Here the writer pulls together the main ideas in the essay. | 6 Final summary statement that is based on the evidence.

Note: The examples in this document are taken from the University of Canberra and used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 licence.

Writing paragraphs

Paragraph writing is a key skill that enables you to incorporate your academic research into your written work. Each paragraph should have its own clearly identified topic sentence or main idea which relates to the argument or point (thesis) you are developing. This idea should then be explained by additional sentences which you have paraphrased from good quality sources and referenced according to the recommended guidelines of your subject (see the chapter Working with Information ). Paragraphs are characterised by increasing specificity; that is, they move from the general to the specific, increasingly refining the reader’s understanding. A common structure for paragraphs in academic writing is as follows.

Topic Sentence

This is the main idea of the paragraph and should relate to the overall issue or purpose of your assignment is addressing. Often it will be expressed as an assertion or claim which supports the overall argument or purpose of your writing.

Explanation/ Elaboration

The main idea must have its meaning explained and elaborated upon. Think critically, do not just describe the idea.

These explanations must include evidence to support your main idea. This information should be paraphrased and referenced according to the appropriate referencing style of your course.

Concluding sentence (critical thinking)

This should explain why the topic of the paragraph is relevant to the assignment question and link to the following paragraph.

Use the checklist below to check your paragraphs are clear and well formed.

Paragraph checklist

- Does your paragraph have a clear main idea?

- Is everything in the paragraph related to this main idea?

- Is the main idea adequately developed and explained?

- Do your sentences run together smoothly?

- Have you included evidence to support your ideas?

- Have you concluded the paragraph by connecting it to your overall topic?

Writing sentences

Make sure all the sentences in your paragraphs make sense. Each sentence must contain a verb to be a complete sentence. Avoid sentence fragments . These are incomplete sentences or ideas that are unfinished and create confusion for your reader. Avoid also run on sentences . This happens when you join two ideas or clauses without using the appropriate punctuation. This also confuses your meaning (See the chapter English Language Foundations for examples and further explanation).

Use transitions (linking words and phrases) to connect your ideas between paragraphs and make your writing flow. The order that you structure the ideas in your assignment should reflect the structure you have outlined in your introduction. Refer to transition words table in the chapter English Language Foundations.

Paraphrasing and Synthesising

Paraphrasing and synthesising are powerful tools that you can use to support the main idea of a paragraph. It is likely that you will regularly use these skills at university to incorporate evidence into explanatory sentences and strengthen your essay. It is important to paraphrase and synthesise because:

- Paraphrasing is regarded more highly at university than direct quoting.

- Paraphrasing can also help you better understand the material.

- Paraphrasing and synthesising demonstrate you have understood what you have read through your ability to summarise and combine arguments from the literature using your own words.

What is paraphrasing?

Paraphrasing is changing the writing of another author into your words while retaining the original meaning. You must acknowledge the original author as the source of the information in your citation. Follow the steps in this table to help you build your skills in paraphrasing (see Table 19.4 ).

Table 19.4 Paraphrasing techniques

Example of paraphrasing.

Please note that these examples and in text citations are for instructional purposes only.

Original text

Health care professionals assist people often when they are at their most vulnerable . To provide the best care and understand their needs, workers must demonstrate good communication skills . They must develop patient trust and provide empathy to effectively work with patients who are experiencing a variety of situations including those who may be suffering from trauma or violence, physical or mental illness or substance abuse (French & Saunders, 2018).

Poor quality paraphrase example

This is a poor example of paraphrasing. Some synonyms have been used and the order of a few words changed within the sentences however the colours of the sentences indicate that the paragraph follows the same structure as the original text.

Health care sector workers are often responsible for vulnerable patients. To understand patients and deliver good service , they need to be excellent communicators . They must establish patient rapport and show empathy if they are to successfully care for patients from a variety of backgrounds and with different medical, psychological and social needs (French & Saunders, 2018).

A good quality paraphrase example

This example demonstrates a better quality paraphrase. The author has demonstrated more understanding of the overall concept in the text by using the keywords as the basis to reconstruct the paragraph. Note how the blocks of colour have been broken up to see how much the structure has changed from the original text.

Empathetic communication is a vital skill for health care workers. Professionals in these fields are often responsible for patients with complex medical, psychological and social needs. Empathetic communication assists in building rapport and gaining the necessary trust to assist these vulnerable patients by providing appropriate supportive care (French & Saunders, 2018).

The good quality paraphrase example demonstrates understanding of the overall concept in the text by using key words as the basis to reconstruct the paragraph. Note how the blocks of colour have been broken up, which indicates how much the structure has changed from the original text.

What is synthesising?

Synthesising means to bring together more than one source of information to strengthen your argument. Once you have learnt how to paraphrase the ideas of one source at a time, you can consider adding additional sources to support your argument. Synthesis demonstrates your understanding and ability to show connections between multiple pieces of evidence to support your ideas and is a more advanced academic thinking and writing skill.

Follow the steps in this table to improve your synthesis techniques (see Table 19.5 ).

Table 19.5 Synthesising techniques

Example of synthesis

There is a relationship between academic procrastination and mental health outcomes. Procrastination has been found to have a negative effect on students’ well-being (Balkis, & Duru, 2016). Yerdelen, McCaffrey, and Klassens’ (2016) research results suggested that there was a positive association between procrastination and anxiety. This was corroborated by Custer’s (2018) findings which indicated that students with higher levels of procrastination also reported greater levels of the anxiety. Therefore, it could be argued that procrastination is an ineffective learning strategy that leads to increased levels of distress.

Topic sentence | Statements using paraphrased evidence | Critical thinking (student voice) | Concluding statement – linking to topic sentence

This example demonstrates a simple synthesis. The author has developed a paragraph with one central theme and included explanatory sentences complete with in-text citations from multiple sources. Note how the blocks of colour have been used to illustrate the paragraph structure and synthesis (i.e., statements using paraphrased evidence from several sources). A more complex synthesis may include more than one citation per sentence.

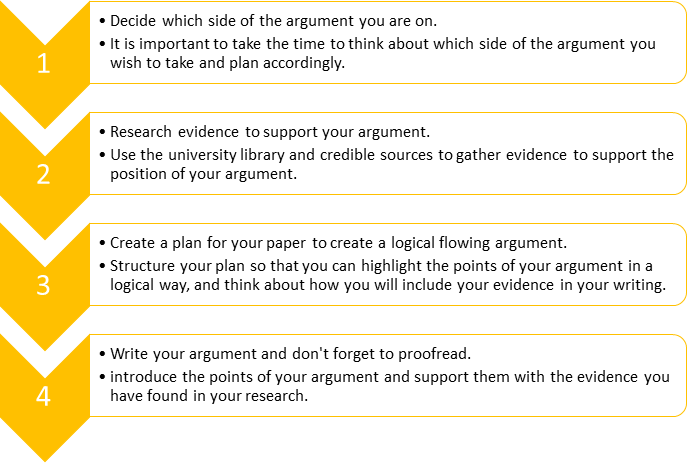

Creating an argument

What does this mean.

Throughout your university studies, you may be asked to ‘argue’ a particular point or position in your writing. You may already be familiar with the idea of an argument, which in general terms means to have a disagreement with someone. Similarly, in academic writing, if you are asked to create an argument, this means you are asked to have a position on a particular topic, and then justify your position using evidence.

What skills do you need to create an argument?

In order to create a good and effective argument, you need to be able to:

- Read critically to find evidence

- Plan your argument

- Think and write critically throughout your paper to enhance your argument

For tips on how to read and write critically, refer to the chapter Thinking for more information. A formula for developing a strong argument is presented below.

A formula for a good argument

What does an argument look like?

As can be seen from the figure above, including evidence is a key element of a good argument. While this may seem like a straightforward task, it can be difficult to think of wording to express your argument. The table below provides examples of how you can illustrate your argument in academic writing (see Table 19.6 ).

Table 19.6 Argument

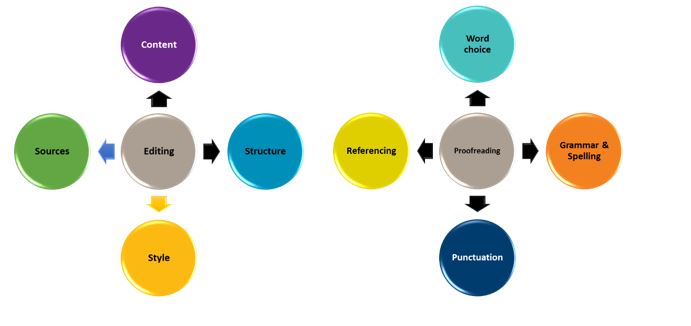

Editing and proofreading (reviewing).

Once you have finished writing your first draft it is recommended that you spend time revising your work. Proofreading and editing are two different stages of the revision process.

- Editing considers the overall focus or bigger picture of the assignment

- Proofreading considers the finer details

As can be seen in the figure above there are four main areas that you should review during the editing phase of the revision process. The main things to consider when editing include content, structure, style, and sources. It is important to check that all the content relates to the assignment task, the structure is appropriate for the purposes of the assignment, the writing is academic in style, and that sources have been adequately acknowledged. Use the checklist below when editing your work.

Editing checklist

- Have I answered the question accurately?

- Do I have enough credible, scholarly supporting evidence?

- Is my writing tone objective and formal enough or have I used emotive and informal language?

- Have I written in the third person not the first person?

- Do I have appropriate in-text citations for all my information?

- Have I included the full details for all my in-text citations in my reference list?

There are also several key things to look out for during the proofreading phase of the revision process. In this stage it is important to check your work for word choice, grammar and spelling, punctuation and referencing errors. It can be easy to mis-type words like ‘from’ and ‘form’ or mix up words like ‘trail’ and ‘trial’ when writing about research, apply American rather than Australian spelling, include unnecessary commas or incorrectly format your references list. The checklist below is a useful guide that you can use when proofreading your work.

Proofreading checklist

- Is my spelling and grammar accurate?

- Are they complete?

- Do they all make sense?

- Do they only contain only one idea?

- Do the different elements (subject, verb, nouns, pronouns) within my sentences agree?

- Are my sentences too long and complicated?

- Do they contain only one idea per sentence?

- Is my writing concise? Take out words that do not add meaning to your sentences.

- Have I used appropriate discipline specific language but avoided words I don’t know or understand that could possibly be out of context?

- Have I avoided discriminatory language and colloquial expressions (slang)?

- Is my referencing formatted correctly according to my assignment guidelines? (for more information on referencing refer to the Managing Assessment feedback section).

This chapter has examined the experience of writing assignments. It began by focusing on how to read and break down an assignment question, then highlighted the key components of essays. Next, it examined some techniques for paraphrasing and summarising, and how to build an argument. It concluded with a discussion on planning and structuring your assignment and giving it that essential polish with editing and proof-reading. Combining these skills and practising them, can greatly improve your success with this very common form of assessment.

- Academic writing requires clear and logical structure, critical thinking and the use of credible scholarly sources.

- A thesis statement is important as it tells the reader the position or argument you have adopted in your assignment. Not all assignments will require a thesis statement.

- Spending time analysing your task and planning your structure before you start to write your assignment is time well spent.

- Information you use in your assignment should come from credible scholarly sources such as textbooks and peer reviewed journals. This information needs to be paraphrased and referenced appropriately.

- Paraphrasing means putting something into your own words and synthesising means to bring together several ideas from sources.

- Creating an argument is a four step process and can be applied to all types of academic writing.

- Editing and proofreading are two separate processes.

Academic Skills Centre. (2013). Writing an introduction and conclusion . University of Canberra, accessed 13 August, 2013, http://www.canberra.edu.au/studyskills/writing/conclusions

Balkis, M., & Duru, E. (2016). Procrastination, self-regulation failure, academic life satisfaction, and affective well-being: underregulation or misregulation form. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 31 (3), 439-459.

Custer, N. (2018). Test anxiety and academic procrastination among prelicensure nursing students. Nursing education perspectives, 39 (3), 162-163.

Yerdelen, S., McCaffrey, A., & Klassen, R. M. (2016). Longitudinal examination of procrastination and anxiety, and their relation to self-efficacy for self-regulated learning: Latent growth curve modeling. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16 (1).

Writing Assignments Copyright © 2021 by Kate Derrington; Cristy Bartlett; and Sarah Irvine is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academic Writing: Structuring your assignment

- Academic Writing

- Planning your writing

- Structuring your assignment

- Critical Thinking & Writing

- Building an argument

- Reflective Writing

- Summarising, paraphrasing and quoting

Assignment Structure

The precise structure of written work at university may vary depending on the nature of different writing tasks (e.g., report, essay, dissertation, reflective account) and specific disciplinary requirements. For more information about different assignment types click here. It is therefore important to understand the type of task you are undertaking and to find out as much as you can about it.

This may involve reading assignment-specific guidance, familiarising yourself with the marking criteria and if necessary, seeking clarification from your tutor/lecturer before you begin planning and writing. That said, essays often share a similar introduction-main body-conclusion basic structure and this section explains the typical functions and features of these three elements.

Structure Elements

- Introduction

- Making your writing flow

Things to note...

- In many kinds of assignment, the introduction makes up 5—15% of the whole essay.

- Although an introduction is the first thing readers see, it may not be the first thing you write.

- Sometimes it may be helpful to leave the introduction until the end, after you have explored your topic more fully.

What information does the introduction contain?

Typically, the introduction…

- Begins by identifying broad topic / subject area, e.g., ‘Leadership styles have a significant impact on employee performance.’

- Focuses attention on the specific theme or problem, e.g., ‘Autocratic leadership is often characterised as...’

- Indicates the main issues and areas of controversy, e.g., ‘The strengths and limitations of autocratic leadership styles are often debated.’

- States your argument or thesis statement, outlining the main ideas you intend to cover, e.g., ‘This essay argues that autocratic leadership is essential in high-volume production environments because...’

- Indicates how your essay will be organised, e.g., ‘This essay will begin by considering...and will then explore...’

We can see in the diagram below how the introduction tends to move from general to specific, in other words from the overall context of the subject to the specifics of the topic itself.

The main body of your essay

- The middle section of your essay usually consists of 70—80% of your whole essay.

- It contains a series of paragraphs exploring key ideas and theories relating to the subject matter.

Paragraph structure

Properly constructed paragraphs are the foundations of a good essay because they help you to focus and clarify your argument as you write, and they help the reader to understand the topic by dividing it logically into sections. Paragraphs typically develop one main idea and tend to follow this pattern:

- They often begin with a Topic Sentence – this is a sentence that expresses the main idea of the paragraph.

- Sentences in the middle of the paragraph develop the topic sentences and may give definitions, examples, explanations, reasons, opposing views, references to literature, interpretations and summaries.

- Sometimes paragraphs have a concluding sentence which may consider how the topic sentence has been developed and/or provides a link to the next paragraph.

Paragraphs can vary significantly in length depending on the type and purpose of the text and may be between 150 and 250/300 words long. A useful way to remember the features of an effective paragraph is to memorise the PEEL acronym below.

P: Point (main point/topic) E: Evidence (examples and sources) E: Explanation (explain how evidence supports your argument) L: Link back to question and/or summarise key points

(Adapted from Godfrey, J (2013) How to Use Your Reading in your Essays . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan)

Once you reach the end of your essay, it is important to sum up your conclusions. In many kinds of essays, the conclusion makes up 5—10% of the whole piece of work and it tends to contain some (if not all) of the following features. It…

- Links back to the question and the thesis statement, e.g. ‘This paper has argued that...’

- Summarises the discussion (reminds the reader what you have demonstrated/proven), e.g., ‘This study has found that generally...’

- Discusses implications and indicates why your argument matters…how it affects the world/the discipline…and what needs to change, e.g., ‘An implication of this study is that...’

- Suggests where things might go next—e.g., perhaps more research needs to be done, e.g., ‘Further research could explore...’

It might also….

- State the limitations of the analysis of evidence, e.g., ‘In spite of its limitations, the study suggests that...’

- Give recommendations, e.g., ‘There is, therefore a definite need for...’

We can see from the diagram (below) how the conclusion tends to move from the specific conclusions of your essay back to the bigger picture or more general application of your ideas.

Writing at university needs to be clear and easy to understand, with all ideas presented logically and carefully tied together. When writing flows well, every element is connected and seems to move naturally from one item to the next.

Without these connections, writing can sometimes feel choppy or disconnected. Certain phrases help to establish the connections between ideas, and these are called transitional phrases, signposting or connecting words.

There are many ways of linking ideas and information—sometimes you might want to highlight a causal relationship between ideas or simply add new information. Here are some examples of linking phrases:

Source: adapted from: Shields, 2010, p.174

As well as establishing clear links between ideas in separate paragraphs, it is also important to show the reader how all your paragraphs fit together and form part of your overall argument. Here are some ways you could highlight links across your whole essay:

- At the end of a paragraph, you could link back to the question to make sure you have demonstrated the relevance of your paragraph to the topic

- You can also link forward and refer the reader to something you will talk about in the next paragraph or later in your essay, e.g. ‘The next section will explore the significance of…’, ‘This is a subject that will be explored later in the essay.’

- Other linking phrases might refer the reader back to something you have already mentioned e.g. ‘As seen in the previous section…’ or ‘Earlier in the essay this theory was explored…’

- You can also link to specific arguments by using phrases like ‘Despite the previous arguments, there are many reasons…’

Further Reading

- << Previous: Planning your writing

- Next: Critical Thinking & Writing >>

- Last Updated: Sep 4, 2024 4:33 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uos.ac.uk/academic-writing

➔ About the Library

➔ Meet the Team

➔ Customer Service Charter

➔ Library Policies & Regulations

➔ Privacy & Data Protection

Essential Links

➔ A-Z of eResources

➔ Frequently Asked Questions

➔Discover the Library

➔Referencing Help

➔ Print & Copy Services

➔ Service Updates

Library & Learning Services, University of Suffolk, Library Building, Long Street, Ipswich, IP4 1QJ

✉ Email Us: [email protected]

✆ Call Us: +44 (0)1473 3 38700

- Utility Menu

- Writing Center

- Writing Program

- Designing Essay Assignments

by Gordon Harvey

Students often do their best and hardest thinking, and feel the greatest sense of mastery and growth, in their writing. Courses and assignments should be planned with this in mind. Three principles are paramount:

1. Name what you want and imagine students doing it

However free students are to range and explore in a paper, the general kind of paper you’re inviting has common components, operations, and criteria of success, and you should make these explicit. Having satisfied yourself, as you should, that what you’re asking is doable, with dignity, by writers just learning the material, try to anticipate in your prompt or discussions of the assignment the following queries:

- What is the purpose of this? How am I going beyond what we have done, or applying it in a new area, or practicing a key academic skill or kind of work?

- To what audience should I imagine myself writing?

- What is the main task or tasks, in a nutshell? What does that key word (e.g., analyze, significance of, critique, explore, interesting, support) really mean in this context or this field?

- What will be most challenging in this and what qualities will most distinguish a good paper? Where should I put my energy? (Lists of possible questions for students to answer in a paper are often not sufficiently prioritized to be helpful.)

- What misconceptions might I have about what I’m to do? (How is this like or unlike other papers I may have written?) Are there too-easy approaches I might take or likely pitfalls? An ambitious goal or standard that I might think I’m expected to meet but am not?

- What form will evidence take in my paper (e.g., block quotations? paraphrase? graphs or charts?) How should I cite it? Should I use/cite material from lecture or section?

- Are there some broad options for structure, emphasis, or approach that I’ll likely be choosing among?

- How should I get started on this? What would be a helpful (or unhelpful) way to take notes, gather data, discover a question or idea? Should I do research?

2. Take time in class to prepare students to succeed at the paper

Resist the impulse to think of class meetings as time for “content” and of writing as work done outside class. Your students won’t have mastered the art of paper writing (if such a mastery is possible) and won’t know the particular disciplinary expectations or moves relevant to the material at hand. Take time in class to show them:

- discuss the assignment in class when you give it, so students can see that you take it seriously, so they can ask questions about it, so they can have it in mind during subsequent class discussions;

- introduce the analytic vocabulary of your assignment into class discussions, and take opportunities to note relevant moves made in discussion or good paper topics that arise;

- have students practice key tasks in class discussions, or in informal writing they do in before or after discussions;

- show examples of writing that illustrates components and criteria of the assignment and that inspires (class readings can sometimes serve as illustrations of a writing principle; so can short excerpts of writing—e.g., a sampling of introductions; and so can bad writing—e.g., a list of problematic thesis statements);

- the topics of originality and plagiarism (what the temptations might be, how to avoid risks) should at some point be addressed directly.

3. Build in process

Ideas develop over time, in a process of posing and revising and getting feedback and revising some more. Assignments should allow for this process in the following ways:

- smaller assignments should prepare for larger ones later;

- students should do some thinking and writing before they write a draft and get a response to it (even if only a response to a proposal or thesis statement sent by email, or described in class);

- for larger papers, students should write and get response (using the skills vocabulary of the assignment) to a draft—at least an “oral draft” (condensed for delivery to the class);

- if possible, meet with students individually about their writing: nothing inspires them more than feeling that you care about their work and development;

- let students reflect on their own writing, in brief cover letters attached to drafts and revisions (these may also ask students to perform certain checks on what they have written, before submitting);

- have clear and firm policies about late work that nonetheless allow for exception if students talk to you in advance.

- Pedagogy Workshops

- Responding to Student Writing

- Commenting Efficiently

- Vocabulary for Discussing Student Writing

- Guides to Teaching Writing

- HarvardWrites Instructor Toolkit

- Additional Resources for Teaching Fellows

NCI LIBRARY

Academic writing skills guide: structuring your assignment.

- Key Features of Academic Writing

- The Writing Process

- Understanding Assignments

- Brainstorming Techniques

- Planning Your Assignments

- Thesis Statements

- Writing Drafts

- Structuring Your Assignment

- How to Deal With Writer's Block

- Using Paragraphs

- Conclusions

- Introductions

- Revising & Editing

- Proofreading

- Grammar & Punctuation

- Reporting Verbs

- Signposting, Transitions & Linking Words/Phrases

- Using Lecturers' Feedback

Keep referring back to the question and assignment brief and make sure that your structure matches what you have been asked to do and check to see if you have appropriate and sufficient evidence to support all of your points. Plans can be structured/restructured at any time during the writing process.

Once you have decided on your key point(s), draw a line through any points that no longer seem to fit. This will mean you are eliminating some ideas and potentially letting go of one or two points that you wanted to make. However, this process is all about improving the relevance and coherence of your writing. Writing involves making choices, including the tough choice to sideline ideas that, however promising, do not fit into your main discussion.

Eventually, you will have a structure that is detailed enough for you to start writing. You will know which ideas go into each section and, ideally, each paragraph and in what order. You will also know which evidence for those ideas from your notes you will be using for each section and paragraph.

Once you have a map/framework of the proposed structure, this forms the skeleton of your assignment and if you have invested enough time and effort into researching and brainstorming your ideas beforehand, it should make it easier to flesh it out. Ultimately, you are aiming for a final draft where you can sum up each paragraph in a couple of words as each paragraph focuses on one main point or idea.

Communications from the Library: Please note all communications from the library, concerning renewal of books, overdue books and reservations will be sent to your NCI student email account.

- << Previous: Writing Drafts

- Next: How to Deal With Writer's Block >>

- Last Updated: Apr 23, 2024 1:31 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ncirl.ie/academic_writing_skills

- Accessibility Tools

- Current Students

- The University

- Student Services

- Centre for Academic Success

- The Academic Skills Lab

- Academic Writing

- Essay Structure

- How to structure your essay

- Swansea University DSA Assessment Centre

- Student Support Services

- Digital Skills

- Dissertation skills

- Why read your writing?

- Signposting

- Writing persuasively

- Tricks for sentence writing

- Common errors in structure and argument

- Grammar and Punctuation

- Academic Integrity

- Presentation Skills

- Study Skills

- Our Publications

- TurnItIn QuickMark Tool

- Welsh Provision

- Peer Assisted Study Sessions

- Peer Writing Advisors

- Academic Integrity Ambassadors

- Maths and Stats Advisors

- Inclusive Student Support Services

- Reaching Wider

A typical assignment has an introduction, a main body and a conclusion. The purpose of the introduction is to signpost everything that a reader can expect from the assignment. The main body is where this will be delivered, and the conclusion provides a summary of the main points, perhaps guiding us to further reading or investigation. It might be useful to visualise the final draft of your assignment using the diagram below.

The main body is framed by an introduction that sets out your argument and a conclusion that recaps your argument and restates your thesis. The paragraphs in the main body each take a step forward in order to progress the argument.

For more in-depth information on structuring each section, click on the tabs below.

.png)

Writing an introduction can be the most difficult part of your assignment because it is where you lay out everything you will cover in what follows. The purpose of an introduction is to clearly tell the reader about the main themes and concepts in your assignment, as well as how you are going to approach them. Key to academic writing are clarity and predictability so the introduction should act as a signpost, or an essay map; after reading the introduction, the reader should understand what your essay will be about, what you are going to say, and what conclusion you will reach. The structure we suggest below will help you include and organise the key information.

The 'funnel' introduction has three distinct sections, moving from general to specific information, and guides the reader through your main argument:

General or Contextual Information:

This is where you give the background information that relates to your assignment question. You can concentrate on the broad themes that you will establish, perhaps by giving some key facts (statistics, for example) that will act as a 'hook' to interest the reader. This section is about contextualising the information you are going to discuss in the next part of your introduction.

Definitions and Key Concepts:

This part of your introduction will orientate your reader. You will need to introduce the key concepts that form the basis of your argument and let the reader know how these are related to the themes you introduce in the first part of the introduction. It might be useful to think about this section of the introduction as signalling to the reader what steps you will take to discuss those themes.

Thesis Statement:

This section will form the end of your introduction and will provide the detailed 'essay map' for your reader. You will make the main claim of your essay in the thesis statement (that is, what is the main conclusion you will reach), and you will outline the steps you are going to take to reach that conclusion (that is, what is the development of your main argument).

A common question about introductions is 'how long should they be?'. There is not a simple answer; it will depend on the length of your assignment. As a guide, lots of departments suggest that you should aim for an introduction of around 10% of your overall word count. Similarly, although the funnel structure is comprised of three parts, this does not mean that your introduction will be split into three paragraphs. How you organise it will depend on the flow of your ideas and the length of your assignment.

The paragraphs in the main body of your assignment act as building blocks for your argument. This means that their structure is crucial for enabling your reader to follow that argument. Just as the overall structure of your assignment has a clear beginning, middle, and end, so does each paragraph. You will usually see this structure referred to as the 'topic sentence', the 'supporting sentences', and the 'summary sentence'.

Topic Sentences

The topic sentence (sometimes called the 'paragraph header') outlines what the reader can expect from the rest of the paragraph; that is, it introduces the argument you will be making and gives some indication of how you will make it. Another way to think about this is that the topic sentence tells the reader what the theme of the paragraph will be (the main idea that underpins the paragraph) and outlines the lens through which you are going to explore that theme (what you are going to say about your main idea).

It is useful for you to check that each of your topic sentences is linked in some way to the thesis statement contained in your introduction. Are you following the ideas you laid out in your thesis statement? By referring back to the thesis statement, you can make sure that your argument remains focused on answering the question (rather than drifting) and that you are covering the information you introduced at the beginning of the assignment. In some cases, the topic sentence may not introduce an argument. This occurs when the purpose of the paragraph is to provide background information or describe something. This is okay too, as long as the content of the paragraph is needed to support your thesis statement in some way.

Tip : The topic sentence may not be the first sentence in the paragraph if you include a linking sentence to your previous paragraph, but it should definitely be placed close to the start of the paragraph.

Supporting Sentences

The supporting sentences are where you put together your main argument. They develop the idea outlined in the topic sentence and contain your analysis of that idea. Your supporting sentences will usually contain your references to the literature in your discipline which you will use to build your own argument. You may also include facts and figures, counter arguments, and your judgements on how useful the literature is for your topic. The key to using supporting sentences to form a good paragraph lies in the 'Four Rs':

- Are the supporting sentences relevant ? Each of them should explore and develop the idea you have introduced in your topic sentence.

- Are they related ? Although you should not repeat the same idea throughout a paragraph, you do need to make sure that each of your supporting sentences is linked. This will help you provide multiple examples, counter arguments, and analysis of the theme of the paragraph. Think of each supporting sentence as a link in the chain of your argument.

- Are the supporting sentences in the right order ? You will need to make an active decision about the way you present the argument in the paragraph; for example, you might present your research chronologically, or perhaps you prefer to discuss the argument and then the counter argument (so grouping together the relevant pieces of information).

- And, of course, any ideas that are not your own need to be clearly referenced . Good referencing, according to the referencing style used by your department, is essential to academic integrity.

Summary Sentences

The summary sentence is important because it helps you tie together the arguments made in your supporting statements and comment on the point made in your topic sentence. This will be where you provide your reader with your judgement on the information contained in the paragraph. In that sense, the summary sentence is your conclusion for the particular point made in the paragraph – you will tell the reader why the point is important and perhaps give an indication of how it is linked to your overall thesis.

Tip : At the end of each paragraph, try asking yourself 'So What?': 'So what is the point of what I've said?'; 'so what is the conclusion I've reached based on the information included in the paragraph?'. This question will help you see whether you have been critical rather than simply descriptive.

The flow within and between paragraphs is important for a coherent structure. You can strengthen the flow by ensuring your argument proceeds logically and by using language that signals to the reader how your argument is progressing, and how you want them to interpret what you are saying:

Logical Order

Broadly following the structures outlined above will help you put together a logical paragraph structure. However, you also need to think about the flow of information in your assignment as a whole. Remember that each paragraph should make a point, discuss that point, and conclude the point before moving on to make a new point. This means that your assignment will be made up of chunks of information and it makes sense to organise those chunks in relation to each other.

Signalling Language

There are many words and phrases you can use to help your reader interpret information. If you focus on using effective transitions in your paragraphs, you will be able to better demonstrate your understanding of the relationship between the ideas you are discussing, and your writing will flow more easily. This is because your reader will be guided between points rather than having to make the links themselves. Below are some of the most common examples of transition words and phrases, though you can find many websites with further examples (university writing centres such as this one are usually reliable sources, though remember to use your judgement):

Tip : There are other techniques you can use to improve the flow of both your argument and style. Cohesive devices like pronouns, word families, and recap words help the reader. In addition, structured reasoning can support your argument. You can find a range of courses which explore these devices in detail by going to the website for the Centre for Academic Success .

.png)

The conclusion should be easy to write because you do not have to discuss any new information (in fact, you should not introduce any new points in this part of your assignment). In reality, though, it can be a struggle to decide what to include in your conclusion. Using the framework in the diagram can help you effectively bring your argument to a close. This is an inverse structure of your introduction: in the conclusion you are moving from specific information to broader information.

In the 'Restate' section of a conclusion, it is a good idea to remind the reader of your thesis statement. You can paraphrase your thesis statement in order to remind the reader of the central claim of the assignment and how you set out to demonstrate this claim.

You can then broaden the discussion to provide a 'Recap' of your main argument. This does not mean repeating yourself; rather, you will give a brief synopsis of each part of your main argument, with a reminder of how it links to your main claim. This will help consolidate your argument in the reader's mind and confirm that you have answered your own thesis.

Finally, the 'Suggest' section can help you place your work within the wider scholarship of your discipline. You might, for example, make suggestions for further research based on gaps you have identified.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

While there are different types of written assignments, most academic writing has a similar structure comprising of: Introduction—acts as a roadmap for the reader. Body—presents points to support your argument. Conclusion—summarises main points discussed.

Most writing at university will require a strong and logically structured introduction. An effective introduction should provide some background or context for your assignment, clearly state your thesis and include the key points you will cover in the body of the essay in order to prove your thesis.

Assignment Structure The precise structure of written work at university may vary depending on the nature of different writing tasks (e.g., report, essay, dissertation, reflective account) and specific disciplinary requirements.

• Are there some broad options for structure, emphasis, or approach that I’ll likely be choosing among? • How should I get started on this? What would be a helpful (or unhelpful) way to take notes, gather data, discover a question or idea? Should I do research? by Gordon Harvey What is the main task or tasks, in a nutshell? What does that key

Designing Essay Assignments. by Gordon Harvey. Students often do their best and hardest thinking, and feel the greatest sense of mastery and growth, in their writing. Courses and assignments should be planned with this in mind. Three principles are paramount: 1. Name what you want and imagine students doing it.

Think carefully about how to structure your assignment before you start to write. Having a well-structured plan will help you considerably in producing a cohesive assignment and will also allow you to write your assignment in stages since it will clearly map out the direction you should proceed in.

Verbs like analyze, compare, discuss, explain, make an argument, propose a solution, trace, or research can help you understand what you’re being asked to do with an assignment. Unless the instructor has specified otherwise, most of your paper assignments at Harvard will ask you to make an argument.

Plan your assignment structure. Before you start, it can help to create a basic assignment structure. This can be as detailed as you like but the basic structure should contain your introduction points, your key arguments and points, and your planned conclusion. Expert tip: Try writing out your plan on sticky notes.

But for many students, the most difficult part of structuring an essay is deciding how to organize information within the body. This article provides useful templates and tips to help you outline your essay, make decisions about your structure, and organize your text logically.

A typical assignment has an introduction, a main body and a conclusion. The purpose of the introduction is to signpost everything that a reader can expect from the assignment. The main body is where this will be delivered, and the conclusion provides a summary of the main points, perhaps guiding us to further reading or investigation.