The Law of Demand (With Diagram)

In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Introduction to the Law of Demand 2. Assumptions of the Law of Demand 3. Exceptions.

Introduction to the Law of Demand :

The law of demand expresses a relationship between the quantity demanded and its price. It may be defined in Marshall’s words as “the amount demanded increases with a fall in price, and diminishes with a rise in price”. Thus it expresses an inverse relation between price and demand. The law refers to the direction in which quantity demanded changes with a change in price.

On the figure, it is represented by the slope of the demand curve which is normally negative throughout its length. The inverse price- demand relationship is based on other things remaining equal. This phrase points towards certain important assumptions on which this law is based.

Assumptions of the Law of Demand:

These assumptions are:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(i) There is no change in the tastes and preferences of the consumer;

(ii) The income of the consumer remains constant;

(iii) There is no change in customs;

(iv) The commodity to be used should not confer distinction on the consumer;

(v) There should not be any substitutes of the commodity;

(vi) There should not be any change in the prices of other products;

(vii) There should not be any possibility of change in the price of the product being used;

(viii) There should not be any change in the quality of the product; and

(ix) The habits of the consumers should remain unchanged. Given these conditions, the law of demand operates. If there is change even in one of these conditions, it will stop operating.

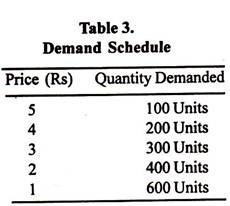

Given these assumptions, the law of demand is explained in terms of Table 3 and Figure 7.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

7.10: The Law of Demand

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 45365

Learning Objectives

- Explain the law of demand

- Explain a demand curve

Demand describes the amount of goods or services that consumers want to (and are able to) pay to purchase that good or service. Before learning more about the details of demand, watch this video to get a basic understanding about what it is and its importance to understanding economic behavior.

You can view the transcript for “Episode 11 – Demand” (opens in new window).

The law of demand states that, other things being equal,

- More of a good will be bought the lower its price

- Less of a good will be bought the higher its price

Ceteris paribus means “other things being equal.”

Demand for Goods and Services

Economists use the term demand to refer to the amount of some good or service consumers are willing and able to purchase at each price. Demand is based on needs and wants—a consumer may be able to differentiate between a need and a want, but from an economist’s perspective, they are the same thing. Demand is also based on ability to pay. If you can’t pay for it, you have no effective demand.

What a buyer pays for a unit of the specific good or service is called the price . The total number of units purchased at that price is called the quantity demanded . A rise in the price of a good or service almost always decreases the quantity of that good or service demanded. Conversely, a fall in price will increase the quantity demanded. When the price of a gallon of gasoline goes up, for example, people look for ways to reduce their consumption by combining several errands, commuting by carpool or mass transit, or taking weekend or vacation trips closer to home. Economists call this inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded the law of demand . The law of demand assumes that all other variables that affect demand are held constant.

An example from the market for gasoline can be shown in the form of a table or a graph. A table that shows the quantity demanded at each price, such as Table \(\PageIndex{1}\), is called a demand schedule . Price in this case is measured in dollars per gallon of gasoline. The quantity demanded is measured in millions of gallons over some time period (for example, per day or per year) and over some geographic area (like a state or a country).

A demand curve shows the relationship between price and quantity demanded on a graph like Figure 1, below, with quantity on the horizontal axis and the price per gallon on the vertical axis. Note that this is an exception to the normal rule in mathematics that the independent variable (x) goes on the horizontal axis and the dependent variable (y) goes on the vertical. Economics is different from math! Note also that each point on the demand curve comes from one row in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\). For example, the upper most point on the demand curve corresponds to the last row in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\), while the lower most point corresponds to the first row.

The demand schedule (Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)) shows that as price rises, quantity demanded decreases, and vice versa. These points can then be graphed, and the line connecting them is the demand curve (shown by line D in the graph, above). The downward slope of the demand curve again illustrates the law of demand—the inverse relationship between prices and quantity demanded.

The demand schedule shown by Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) and the demand curve shown by the graph in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) are two ways of describing the same relationship between price and quantity demanded.

Demand curves will look somewhat different for each product. They may appear relatively steep or flat, or they may be straight or curved. Nearly all demand curves share the fundamental similarity that they slope down from left to right. In this way, demand curves embody the law of demand: As the price increases, the quantity demanded decreases, and conversely, as the price decreases, the quantity demanded increases.

Practice Questions

https://assessments.lumenlearning.co...essments/14272

https://assessments.lumenlearning.co...essments/14273

Demand vs. Quantity Demanded

In economic terminology, demand is not the same as quantity demanded . When economists talk about demand, they mean the relationship between a range of prices and the quantities demanded at those prices, as illustrated by a demand curve or a demand schedule. When economists talk about quantity demanded, they mean only a certain point on the demand curve, or one quantity on the demand schedule. In short, demand refers to the curve and quantity demanded refers to the (specific) point on the curve.

Change in Demand vs. Change in Quantity Demanded

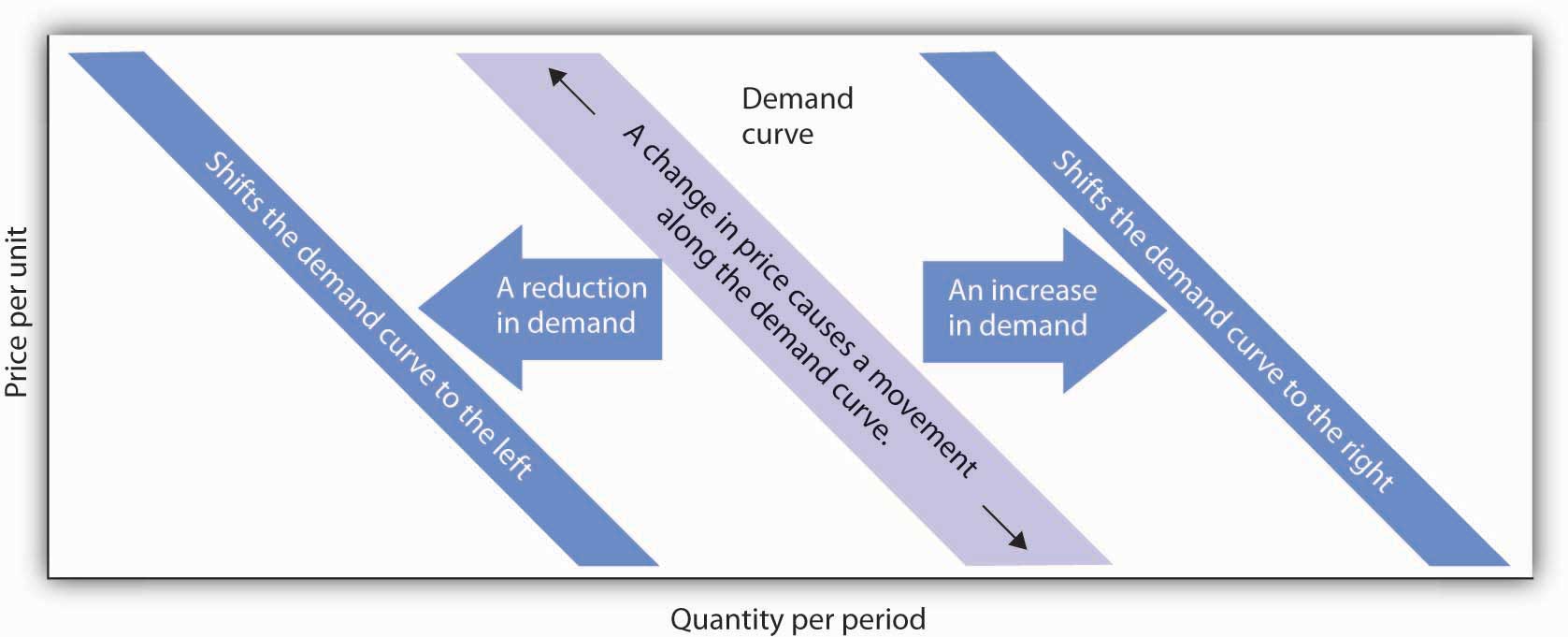

It’s hard to overstate the importance of understanding the difference between shifts in curves and movements along curves. Remember, when we talk about changes in demand or supply, we do not mean the same thing as changes in quantity demanded or quantity supplied .

A change in demand refers to a shift in the entire demand curve, which is caused by a variety of factors (preferences, income, prices of substitutes and complements, expectations, population, etc.). In this case, the entire demand curve moves left or right.

A change in quantity demanded refers to a movement along the demand curve, which is caused only by a change in price. In this case, the demand curve doesn’t move; rather, we move along the existing demand curve.

Contributors and Attributions

- Revision and adaptation. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Principles of Microeconomics Chapter 3.1. Authored by : OpenStax College. Provided by : Rice University. Located at : http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:24/Microeconomics . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at cnx.org/content/col11627/latest

- Presto. Authored by : michaelgoodin. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/michaelgoodin/6395014081/ . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- Episode 11: Demand. Authored by : Dr. Mary J. McGlasson. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uXlZIn6W7Ew&feature=youtu.be . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- Episode 12: Change in Demand vs Change in Quantity Demanded. Authored by : Dr. Mary J. McGlasson. Located at : https://youtu.be/aTSwcXJ700c . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is the Law of Demand?

Understanding the law of demand, demand vs. quantity demanded, factors affecting demand, law of supply.

- Frequently Asked Questions

The Bottom Line

- Guide to Microeconomics

What Is the Law of Demand in Economics, and How Does It Work?

Adam Hayes, Ph.D., CFA, is a financial writer with 15+ years Wall Street experience as a derivatives trader. Besides his extensive derivative trading expertise, Adam is an expert in economics and behavioral finance. Adam received his master's in economics from The New School for Social Research and his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in sociology. He is a CFA charterholder as well as holding FINRA Series 7, 55 & 63 licenses. He currently researches and teaches economic sociology and the social studies of finance at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/adam_hayes-5bfc262a46e0fb005118b414.jpg)

Katrina Ávila Munichiello is an experienced editor, writer, fact-checker, and proofreader with more than fourteen years of experience working with print and online publications.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/KatrinaAvilaMunichiellophoto-9d116d50f0874b61887d2d214d440889.jpg)

The law of demand is one of the most fundamental concepts in economics. It works with the law of supply to explain how market economies allocate resources and determine the prices of goods and services that we observe in everyday transactions.

The law of demand states that the quantity purchased varies inversely with price. In other words, the higher the price, the lower the quantity demanded. This occurs because of diminishing marginal utility . That is, consumers use the first units of an economic good they purchase to serve their most urgent needs first, then they use each additional unit of the good to serve successively lower-valued ends.

Key Takeaways

- The law of demand is a fundamental principle of economics that states that at a higher price, consumers will demand a lower quantity of a good.

- Demand is derived from the law of diminishing marginal utility, the fact that consumers use economic goods to satisfy their most urgent needs first.

- A market demand curve expresses the sum of quantity demanded at each price across all consumers in the market.

- Changes in price can be reflected in movement along a demand curve, but by themselves, they don't increase or decrease demand.

- The shape and magnitude of demand shifts in response to changes in consumer preferences, incomes, or related economic goods, not usually to changes in price.

Economics involves the study of how people use limited means to satisfy unlimited wants. The law of demand focuses on those unlimited wants. Naturally, people prioritize more urgent wants and needs over less urgent ones in their economic behavior, and this carries over into how people choose among the limited means available to them.

For any economic good, the first unit of that good that a consumer gets their hands on will tend to be used to satisfy the most urgent need the consumer has that that good can satisfy.

For example, consider a castaway on a desert island who obtains a six-pack of bottled fresh water that washes up onshore. The first bottle will be used to satisfy the castaway’s most urgently felt need, which is most likely drinking water to avoid dying of thirst.

The second bottle might be used for bathing to stave off disease, an urgent but less immediate need. The third bottle could be used for a less urgent need, such as boiling some fish to have a hot meal, and on down to the last bottle, which the castaway uses for a relatively low priority, such as watering a small potted plant to feel less alone on the island.

Because each additional bottle of water is used for a successively less highly valued want or need by our castaway, we can say that the castaway values each additional bottle less than the one before.

The more units of a good that consumers buy, the less they are willing to pay in terms of price.

Similarly, when consumers purchase goods on the market, each additional unit of any given good or service that they buy will be put to a less valued use than the one before, so we can say that they value each additional unit less and less. Because they value each additional unit of the good less , they aren't willing to pay as much for it.

By adding up all the units of a good that consumers are willing to buy at any given price, we can describe a market demand curve , which is always sloping downward, like the one shown in the chart below. Each point on the curve (A, B, C) reflects the quantity demanded (Q) at a given price (P). At point A, for example, the quantity demanded is low (Q1) and the price is high (P1). At higher prices, consumers demand less of the good, and at lower prices, they demand more.

In economic thinking, it is important to understand the difference between the phenomenon of demand and the quantity demanded. In the chart above, the term “demand” refers to the light blue line plotted through A, B, and C.

It expresses the relationship between the urgency of consumer wants and the number of units of the economic good at hand. A change in demand means a shift of the position or shape of this curve; it reflects a change in the underlying pattern of consumer wants and needs vis-à-vis the means available to satisfy them.

On the other hand, the term “quantity demanded” refers to a point along the horizontal axis. Changes in the quantity demanded strictly reflect changes in the price, without implying any change in the pattern of consumer preferences.

Changes in quantity demanded just mean movement along the demand curve itself because of a change in price. These two ideas are often conflated, but this is a common error—rising (or falling) prices don't decrease (or increase) demand; they change the quantity demanded .

So what does change demand? The shape and position of the demand curve can be affected by several factors. Rising incomes tend to increase demand for normal economic goods, as people are willing to spend more. The availability of close substitute products that compete with a given economic good will tend to reduce demand for that good because they can satisfy the same kinds of consumer wants and needs.

Conversely, the availability of closely complementary goods will tend to increase demand for an economic good because the use of two goods together can be even more valuable to consumers than using them separately, like peanut butter and jelly.

Other factors such as future expectations, changes in background environmental conditions, or changes in the actual or perceived quality of a good can change the demand curve because they alter the pattern of consumer preferences for how the good can be used and how urgently it is needed.

Supply is the total amount of a specific good or service that is available to consumers at a certain price point. As the supply of a product fluctuates, so does the demand, which directly affects the price of the product.

The law of supply, then, is a microeconomic law stating that, all other factors being equal, as the price of a good or service rises, the quantity that suppliers offer will rise in turn (and vice versa). When demand exceeds the available supply, the price of a product typically will rise. Conversely, should the supply of an item increase while the demand remains the same, the price will go down.

What is a Simple Explanation of the Law of Demand?

The law of demand tells us that if more people want to buy something, given a limited supply, the price of that thing will be bid higher. Likewise, the higher the price of a good, the lower the quantity that will be purchased by consumers.

Why Is the Law of Demand Important?

Together with the law of supply, the law of demand helps us understand why things are priced at the level that they are, and to identify opportunities to buy what are perceived to be underpriced (or sell overpriced) products, assets, or securities . For instance, a firm may boost production in response to rising prices that have been spurred by a surge in demand.

Can the Law of Demand Be Broken?

Yes. In certain cases, an increase in demand doesn't affect prices in ways predicted by the law of demand. For instance, so-called Veblen goods are things for which demand increases as their price rises, as they are perceived as status symbols. Similarly, demand for Giffen goods (which, in contrast to Veblen goods, aren't luxury items) rises when the price goes up and falls when the price falls. Examples of Giffen goods can include bread, rice, and wheat. These tend to be common necessities and essential items with few good substitutes at the same price levels.

The law of demand posits that the price of an item and the quantity demanded have an inverse relationship. Essentially, it tells us that people will buy more of something when its price falls and vice versa. When graphed, the law of demand appears as a line sloping downward.

This law is a fundamental principle of economics. It helps to set prices, understand why things are priced as they are, and identify items that may be over- or underpriced.

University of Southern Philippines Foundation. " Law of Demand ," Page 1.

Econlib. " Demand ."

University of Pittsburgh. " Supply and Demand ," Page 1.

University of Pittsburgh. " Supply and Demand ," Page 3.

- A Practical Guide to Microeconomics 1 of 39

- Economists' Assumptions in Their Economic Models 2 of 39

- 5 Nobel Prize-Winning Economic Theories You Should Know About 3 of 39

- Positive vs. Normative Economics: What's the Difference? 4 of 39

- 5 Factors That Influence Competition in Microeconomics 5 of 39

- How Does Government Policy Impact Microeconomics? 6 of 39

- Microeconomics vs. Macroeconomics: What’s the Difference? 7 of 39

- How Do I Differentiate Between Micro and Macro Economics? 8 of 39

- Microeconomics vs. Macroeconomics Investments 9 of 39

- Introduction to Supply and Demand 10 of 39

- Is Demand or Supply More Important to the Economy? 11 of 39

- Demand: How It Works Plus Economic Determinants and the Demand Curve 12 of 39

- What Is the Law of Demand in Economics, and How Does It Work? 13 of 39

- Demand Curves: What Are They, Types, and Example 14 of 39

- Supply 15 of 39

- The Law of Supply Explained, With the Curve, Types, and Examples 16 of 39

- Supply Curve: Definition, How It Works, and Example 17 of 39

- Elasticity: What It Means in Economics, Formula, and Examples 18 of 39

- Price Elasticity of Demand: Meaning, Types, and Factors That Impact It 19 of 39

- Elasticity vs. Inelasticity of Demand: What's the Difference? 20 of 39

- What Is Inelastic? Definition, Calculation, and Examples of Goods 21 of 39

- What Affects Demand Elasticity for Goods and Services? 22 of 39

- What Factors Influence a Change in Demand Elasticity? 23 of 39

- Utility in Economics Explained: Types and Measurement 24 of 39

- Utility in Microeconomics: Origins, Types, and Uses 25 of 39

- Utility Function Definition, Example, and Calculation 26 of 39

- Definition of Total Utility in Economics, With Example 27 of 39

- Marginal Utilities: Definition, Types, Examples, and History 28 of 39

- What Is the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility? With Example 29 of 39

- What Does the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility Explain? 30 of 39

- Economic Equilibrium 31 of 39

- What Is the Income Effect? Its Meaning and Example 32 of 39

- Indifference Curves in Economics: What Do They Explain? 33 of 39

- Consumer Surplus Definition, Measurement, and Example 34 of 39

- What Is Comparative Advantage? 35 of 39

- What Are Economies of Scale? 36 of 39

- Perfect Competition: Examples and How It Works 37 of 39

- What Is the Invisible Hand in Economics? 38 of 39

- Market Failure: What It Is in Economics, Common Types, and Causes 39 of 39

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/DemandCurve-4197946-Final-64b129da426e4213a0911a47bb9a3bfa.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

3.1 Demand, Supply, and Equilibrium in Markets for Goods and Services

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain demand, quantity demanded, and the law of demand

- Explain supply, quantity supplied, and the law of supply

- Identify a demand curve and a supply curve

- Explain equilibrium, equilibrium price, and equilibrium quantity

First let’s first focus on what economists mean by demand, what they mean by supply, and then how demand and supply interact in a market.

Demand for Goods and Services

Economists use the term demand to refer to the amount of some good or service consumers are willing and able to purchase at each price. Demand is fundamentally based on needs and wants—if you have no need or want for something, you won't buy it. While a consumer may be able to differentiate between a need and a want, from an economist’s perspective they are the same thing. Demand is also based on ability to pay. If you cannot pay for it, you have no effective demand. By this definition, a person who does not have a drivers license has no effective demand for a car.

What a buyer pays for a unit of the specific good or service is called price . The total number of units that consumers would purchase at that price is called the quantity demanded . A rise in price of a good or service almost always decreases the quantity demanded of that good or service. Conversely, a fall in price will increase the quantity demanded. When the price of a gallon of gasoline increases, for example, people look for ways to reduce their consumption by combining several errands, commuting by carpool or mass transit, or taking weekend or vacation trips closer to home. Economists call this inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded the law of demand . The law of demand assumes that all other variables that affect demand (which we explain in the next module) are held constant.

We can show an example from the market for gasoline in a table or a graph. Economists call a table that shows the quantity demanded at each price, such as Table 3.1 , a demand schedule . In this case we measure price in dollars per gallon of gasoline. We measure the quantity demanded in millions of gallons over some time period (for example, per day or per year) and over some geographic area (like a state or a country). A demand curve shows the relationship between price and quantity demanded on a graph like Figure 3.2 , with quantity on the horizontal axis and the price per gallon on the vertical axis. (Note that this is an exception to the normal rule in mathematics that the independent variable (x) goes on the horizontal axis and the dependent variable (y) goes on the vertical axis. While economists often use math, they are different disciplines.)

Table 3.1 shows the demand schedule and the graph in Figure 3.2 shows the demand curve. These are two ways to describe the same relationship between price and quantity demanded.

Demand curves will appear somewhat different for each product. They may appear relatively steep or flat, or they may be straight or curved. Nearly all demand curves share the fundamental similarity that they slope down from left to right. Demand curves embody the law of demand: As the price increases, the quantity demanded decreases, and conversely, as the price decreases, the quantity demanded increases.

Confused about these different types of demand? Read the next Clear It Up feature.

Clear It Up

Is demand the same as quantity demanded.

In economic terminology, demand is not the same as quantity demanded. When economists talk about demand, they mean the relationship between a range of prices and the quantities demanded at those prices, as illustrated by a demand curve or a demand schedule. When economists talk about quantity demanded, they mean only a certain point on the demand curve, or one quantity on the demand schedule. In short, demand refers to the curve and quantity demanded refers to a (specific) point on the curve.

Supply of Goods and Services

When economists talk about supply , they mean the amount of some good or service a producer is willing to supply at each price. Price is what the producer receives for selling one unit of a good or service . A rise in price almost always leads to an increase in the quantity supplied of that good or service, while a fall in price will decrease the quantity supplied. When the price of gasoline rises, for example, it encourages profit-seeking firms to take several actions: expand exploration for oil reserves; drill for more oil; invest in more pipelines and oil tankers to bring the oil to plants for refining into gasoline; build new oil refineries; purchase additional pipelines and trucks to ship the gasoline to gas stations; and open more gas stations or keep existing gas stations open longer hours. Economists call this positive relationship between price and quantity supplied—that a higher price leads to a higher quantity supplied and a lower price leads to a lower quantity supplied—the law of supply . The law of supply assumes that all other variables that affect supply (to be explained in the next module) are held constant.

Still unsure about the different types of supply? See the following Clear It Up feature.

Is supply the same as quantity supplied?

In economic terminology, supply is not the same as quantity supplied. When economists refer to supply, they mean the relationship between a range of prices and the quantities supplied at those prices, a relationship that we can illustrate with a supply curve or a supply schedule. When economists refer to quantity supplied, they mean only a certain point on the supply curve, or one quantity on the supply schedule. In short, supply refers to the curve and quantity supplied refers to a (specific) point on the curve.

Figure 3.3 illustrates the law of supply, again using the market for gasoline as an example. Like demand, we can illustrate supply using a table or a graph. A supply schedule is a table, like Table 3.2 , that shows the quantity supplied at a range of different prices. Again, we measure price in dollars per gallon of gasoline and we measure quantity supplied in millions of gallons. A supply curve is a graphic illustration of the relationship between price, shown on the vertical axis, and quantity, shown on the horizontal axis. The supply schedule and the supply curve are just two different ways of showing the same information. Notice that the horizontal and vertical axes on the graph for the supply curve are the same as for the demand curve.

The shape of supply curves will vary somewhat according to the product: steeper, flatter, straighter, or curved. Nearly all supply curves, however, share a basic similarity: they slope up from left to right and illustrate the law of supply: as the price rises, say, from $1.00 per gallon to $2.20 per gallon, the quantity supplied increases from 500 gallons to 720 gallons. Conversely, as the price falls, the quantity supplied decreases.

Equilibrium—Where Demand and Supply Intersect

Because the graphs for demand and supply curves both have price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis, the demand curve and supply curve for a particular good or service can appear on the same graph. Together, demand and supply determine the price and the quantity that will be bought and sold in a market.

Figure 3.4 illustrates the interaction of demand and supply in the market for gasoline. The demand curve (D) is identical to Figure 3.2 . The supply curve (S) is identical to Figure 3.3 . Table 3.3 contains the same information in tabular form.

Remember this: When two lines on a diagram cross, this intersection usually means something. The point where the supply curve (S) and the demand curve (D) cross, designated by point E in Figure 3.4 , is called the equilibrium . The equilibrium price is the only price where the plans of consumers and the plans of producers agree—that is, where the amount of the product consumers want to buy (quantity demanded) is equal to the amount producers want to sell (quantity supplied). Economists call this common quantity the equilibrium quantity . At any other price, the quantity demanded does not equal the quantity supplied, so the market is not in equilibrium at that price.

In Figure 3.4 , the equilibrium price is $1.40 per gallon of gasoline and the equilibrium quantity is 600 million gallons. If you had only the demand and supply schedules, and not the graph, you could find the equilibrium by looking for the price level on the tables where the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied are equal.

The word “equilibrium” means “balance.” If a market is at its equilibrium price and quantity, then it has no reason to move away from that point. However, if a market is not at equilibrium, then economic pressures arise to move the market toward the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity.

Imagine, for example, that the price of a gallon of gasoline was above the equilibrium price—that is, instead of $1.40 per gallon, the price is $1.80 per gallon. The dashed horizontal line at the price of $1.80 in Figure 3.4 illustrates this above-equilibrium price. At this higher price, the quantity demanded drops from 600 to 500. This decline in quantity reflects how consumers react to the higher price by finding ways to use less gasoline.

Moreover, at this higher price of $1.80, the quantity of gasoline supplied rises from 600 to 680, as the higher price makes it more profitable for gasoline producers to expand their output. Now, consider how quantity demanded and quantity supplied are related at this above-equilibrium price. Quantity demanded has fallen to 500 gallons, while quantity supplied has risen to 680 gallons. In fact, at any above-equilibrium price, the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded. We call this an excess supply or a surplus .

With a surplus, gasoline accumulates at gas stations, in tanker trucks, in pipelines, and at oil refineries. This accumulation puts pressure on gasoline sellers. If a surplus remains unsold, those firms involved in making and selling gasoline are not receiving enough cash to pay their workers and to cover their expenses. In this situation, some producers and sellers will want to cut prices, because it is better to sell at a lower price than not to sell at all. Once some sellers start cutting prices, others will follow to avoid losing sales. These price reductions in turn will stimulate a higher quantity demanded. Therefore, if the price is above the equilibrium level, incentives built into the structure of demand and supply will create pressures for the price to fall toward the equilibrium.

Now suppose that the price is below its equilibrium level at $1.20 per gallon, as the dashed horizontal line at this price in Figure 3.4 shows. At this lower price, the quantity demanded increases from 600 to 700 as drivers take longer trips, spend more minutes warming up the car in the driveway in wintertime, stop sharing rides to work, and buy larger cars that get fewer miles to the gallon. However, the below-equilibrium price reduces gasoline producers’ incentives to produce and sell gasoline, and the quantity supplied falls from 600 to 550.

When the price is below equilibrium, there is excess demand , or a shortage —that is, at the given price the quantity demanded, which has been stimulated by the lower price, now exceeds the quantity supplied, which has been depressed by the lower price. In this situation, eager gasoline buyers mob the gas stations, only to find many stations running short of fuel. Oil companies and gas stations recognize that they have an opportunity to make higher profits by selling what gasoline they have at a higher price. As a result, the price rises toward the equilibrium level. Read Demand, Supply, and Efficiency for more discussion on the importance of the demand and supply model.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Steven A. Greenlaw, David Shapiro, Daniel MacDonald

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Economics 3e

- Publication date: Dec 14, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/3-1-demand-supply-and-equilibrium-in-markets-for-goods-and-services

© Jan 23, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Law of Demand – Definition, Explanation

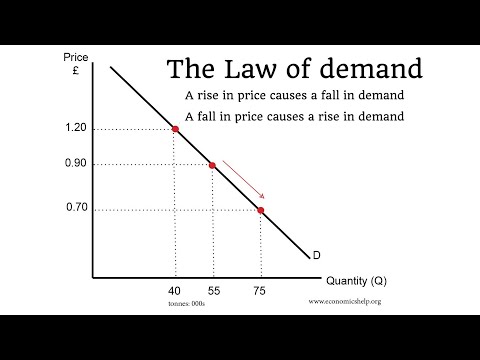

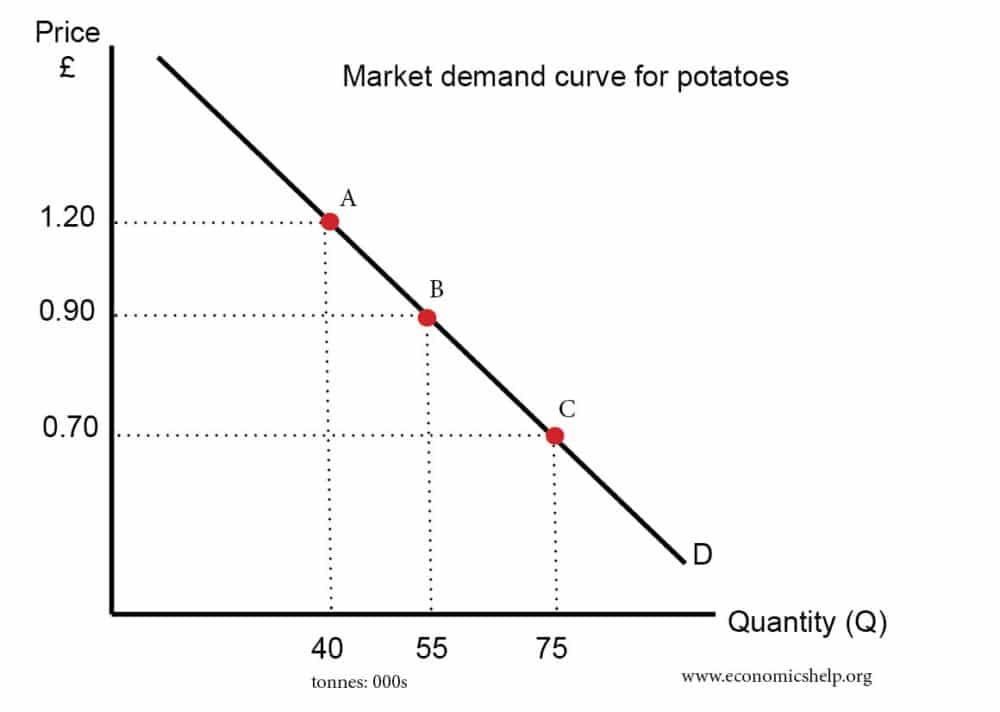

The law of demand states that ceteris paribus (other things being equal)

- If the price of good rises, then the quantity demanded will fall

- If the price of a good falls, then the quantity demand will rise.

At point (A) Price is £1.20 and the quantity demand is 40,000 tonnes. When the price falls to £0.90, the quantity demanded rises to 55,000 tonnes (point B)

If the price fell to £0.70, demand would rise to 75,000.

What explains the law of demand?

There are two factors that explain the inverse relationship between price and quantity demand.

1. Income effect . If prices rise, people will feel poorer after purchasing the more expensive goods. They will have less disposable income and so cannot afford to buy as much. If you have an income of £100, then an increase in the price of goods, your real income is effectively falling.

2. Substitution effect . If the price of one good rise, consumers will be encouraged to buy alternative goods which are now relatively cheaper than they were. For example, if the price of potatoes rises, it will encourage consumers to buy rice instead.

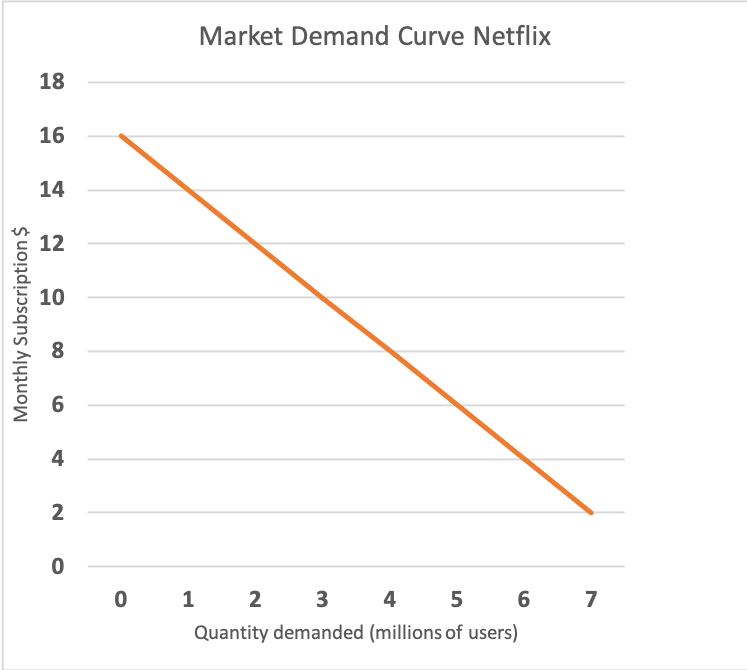

Demand Schedule

A demand schedule is a table showing the different quantities of a good that consumers are willing and able to buy at various prices for a particular period.

This is the market demand schedule for Netflix subscriptions

Demand Curve

A demand curve can be for an individual consumer or the whole market (market demand curve)

Exceptions to the law of demand

Giffen Good . This is good where a higher price causes an increase in demand (reversing the usual law of demand). The increase in demand is due to the income effect of the higher price outweighing the substitution effect. The idea is that if you are very poor and the price of your basic foodstuff (e.g. rice) increases, then you can’t afford the more expensive alternative food (meat) therefore, you end up buying more rice because it is the only thing you can afford. These goods are very rare and require a society with very low income and limited consumer choices.

Veblen good/ostentatious good . This is where if the price rises, then some people may want to buy more because the higher price makes the good appear more attractive. For example, if designer clothing becomes more expensive than for some individuals, the higher price makes it more expensive. However, whilst individual demand curves may be upward sloping. The market demand curve is unlikely to be. Because although it may be more desirable not everyone can afford it. In fact, the super-rich wants to buy more – precisely because it is exclusive.

Nobody buys the cheapest. Another possibility is that in restaurants, the most popular wine is the second cheapest. This is due to the behavioural choices of consumers. When going out to a restaurant, people don’t like to buy the cheapest wine because it suggests you don’t care about giving diners a good meal. Therefore, often the second cheapest wine often sells more because people think they are getting better quality. Therefore, if you increase the price of the cheapest wine, its demand may actually rise.

Perfectly inelastic . If demand is perfectly inelastic, then an increase in the price has no effect on reducing demand. This may be good like salt, which is very cheap but essential.

Perfectly elastic . Demand is infinite at a certain price, therefore reducing the price will not change the quantity demanded.

- Factors affecting demand

- Shift in Demand and Movement along the Demand Curve

2 thoughts on “Law of Demand – Definition, Explanation”

What is in indepth example of the law of demand?

Comments are closed.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Learning Objectives

- Define the quantity demanded of a good or service and illustrate it using a demand schedule and a demand curve.

- Distinguish between the following pairs of concepts: demand and quantity demanded, demand schedule and demand curve, movement along and shift in a demand curve.

- Identify demand shifters and determine whether a change in a demand shifter causes the demand curve to shift to the right or to the left.

How many pizzas will people eat this year? How many doctor visits will people make? How many houses will people buy?

Each good or service has its own special characteristics that determine the quantity people are willing and able to consume. One is the price of the good or service itself. Other independent variables that are important determinants of demand include consumer preferences, prices of related goods and services, income, demographic characteristics such as population size, and buyer expectations. The number of pizzas people will purchase, for example, depends very much on whether they like pizza. It also depends on the prices for alternatives such as hamburgers or spaghetti. The number of doctor visits is likely to vary with income—people with higher incomes are likely to see a doctor more often than people with lower incomes. The demands for pizza, for doctor visits, and for housing are certainly affected by the age distribution of the population and its size.

While different variables play different roles in influencing the demands for different goods and services, economists pay special attention to one: the price of the good or service. Given the values of all the other variables that affect demand, a higher price tends to reduce the quantity people demand, and a lower price tends to increase it. A medium pizza typically sells for $5 to $10. Suppose the price were $30. Chances are, you would buy fewer pizzas at that price than you do now. Suppose pizzas typically sold for $2 each. At that price, people would be likely to buy more pizzas than they do now.

We will discuss first how price affects the quantity demanded of a good or service and then how other variables affect demand.

Price and the Demand Curve

Because people will purchase different quantities of a good or service at different prices, economists must be careful when speaking of the “demand” for something. They have therefore developed some specific terms for expressing the general concept of demand.

The quantity demanded of a good or service is the quantity buyers are willing and able to buy at a particular price during a particular period, all other things unchanged. (As we learned, we can substitute the Latin phrase “ceteris paribus” for “all other things unchanged.”) Suppose, for example, that 100,000 movie tickets are sold each month in a particular town at a price of $8 per ticket. That quantity—100,000—is the quantity of movie admissions demanded per month at a price of $8. If the price were $12, we would expect the quantity demanded to be less. If it were $4, we would expect the quantity demanded to be greater. The quantity demanded at each price would be different if other things that might affect it, such as the population of the town, were to change. That is why we add the qualifier that other things have not changed to the definition of quantity demanded.

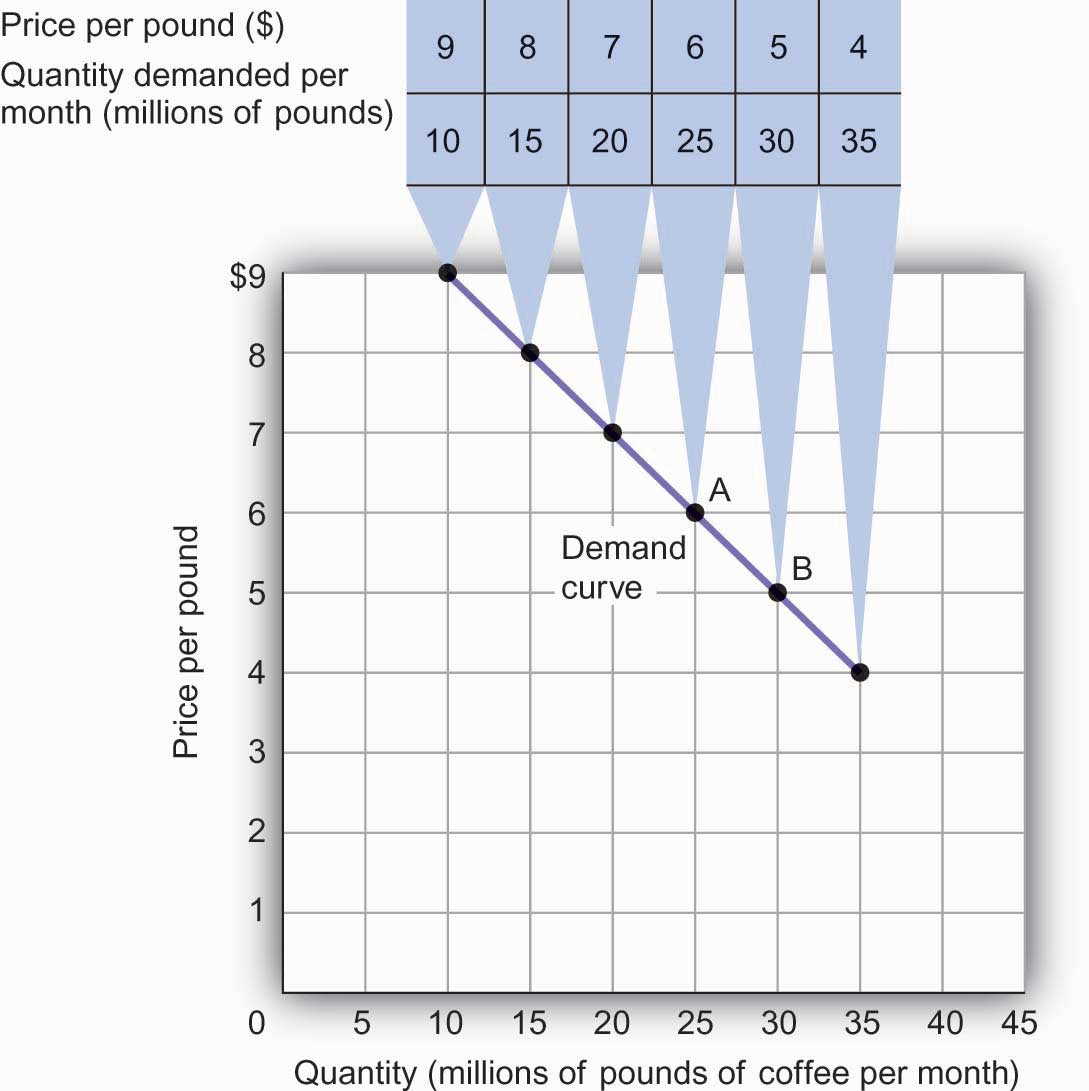

A demand schedule is a table that shows the quantities of a good or service demanded at different prices during a particular period, all other things unchanged. To introduce the concept of a demand schedule, let us consider the demand for coffee in the United States. We will ignore differences among types of coffee beans and roasts, and speak simply of coffee. The table in Figure 3.1 “A Demand Schedule and a Demand Curve” shows quantities of coffee that will be demanded each month at prices ranging from $9 to $4 per pound; the table is a demand schedule. We see that the higher the price, the lower the quantity demanded.

Figure 3.1 A Demand Schedule and a Demand Curve

The table is a demand schedule; it shows quantities of coffee demanded per month in the United States at particular prices, all other things unchanged. These data are then plotted on the demand curve. At point A on the curve, 25 million pounds of coffee per month are demanded at a price of $6 per pound. At point B, 30 million pounds of coffee per month are demanded at a price of $5 per pound.

The information given in a demand schedule can be presented with a demand curve , which is a graphical representation of a demand schedule. A demand curve thus shows the relationship between the price and quantity demanded of a good or service during a particular period, all other things unchanged. The demand curve in Figure 3.1 “A Demand Schedule and a Demand Curve” shows the prices and quantities of coffee demanded that are given in the demand schedule. At point A, for example, we see that 25 million pounds of coffee per month are demanded at a price of $6 per pound. By convention, economists graph price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis.

Price alone does not determine the quantity of coffee or any other good that people buy. To isolate the effect of changes in price on the quantity of a good or service demanded, however, we show the quantity demanded at each price, assuming that those other variables remain unchanged. We do the same thing in drawing a graph of the relationship between any two variables; we assume that the values of other variables that may affect the variables shown in the graph (such as income or population) remain unchanged for the period under consideration.

A change in price, with no change in any of the other variables that affect demand, results in a movement along the demand curve. For example, if the price of coffee falls from $6 to $5 per pound, consumption rises from 25 million pounds to 30 million pounds per month. That is a movement from point A to point B along the demand curve in Figure 3.1 “A Demand Schedule and a Demand Curve” . A movement along a demand curve that results from a change in price is called a change in quantity demanded . Note that a change in quantity demanded is not a change or shift in the demand curve; it is a movement along the demand curve.

The negative slope of the demand curve in Figure 3.1 “A Demand Schedule and a Demand Curve” suggests a key behavioral relationship of economics. All other things unchanged, the law of demand holds that, for virtually all goods and services, a higher price leads to a reduction in quantity demanded and a lower price leads to an increase in quantity demanded.

The law of demand is called a law because the results of countless studies are consistent with it. Undoubtedly, you have observed one manifestation of the law. When a store finds itself with an overstock of some item, such as running shoes or tomatoes, and needs to sell these items quickly, what does it do? It typically has a sale, expecting that a lower price will increase the quantity demanded. In general, we expect the law of demand to hold. Given the values of other variables that influence demand, a higher price reduces the quantity demanded. A lower price increases the quantity demanded. Demand curves, in short, slope downward.

Changes in Demand

Of course, price alone does not determine the quantity of a good or service that people consume. Coffee consumption, for example, will be affected by such variables as income and population. Preferences also play a role. The story at the beginning of the chapter illustrates as much. Starbucks “turned people on” to coffee. We also expect other prices to affect coffee consumption. People often eat doughnuts or bagels with their coffee, so a reduction in the price of doughnuts or bagels might induce people to drink more coffee. An alternative to coffee is tea, so a reduction in the price of tea might result in the consumption of more tea and less coffee. Thus, a change in any one of the variables held constant in constructing a demand schedule will change the quantities demanded at each price. The result will be a shift in the entire demand curve rather than a movement along the demand curve. A shift in a demand curve is called a change in demand .

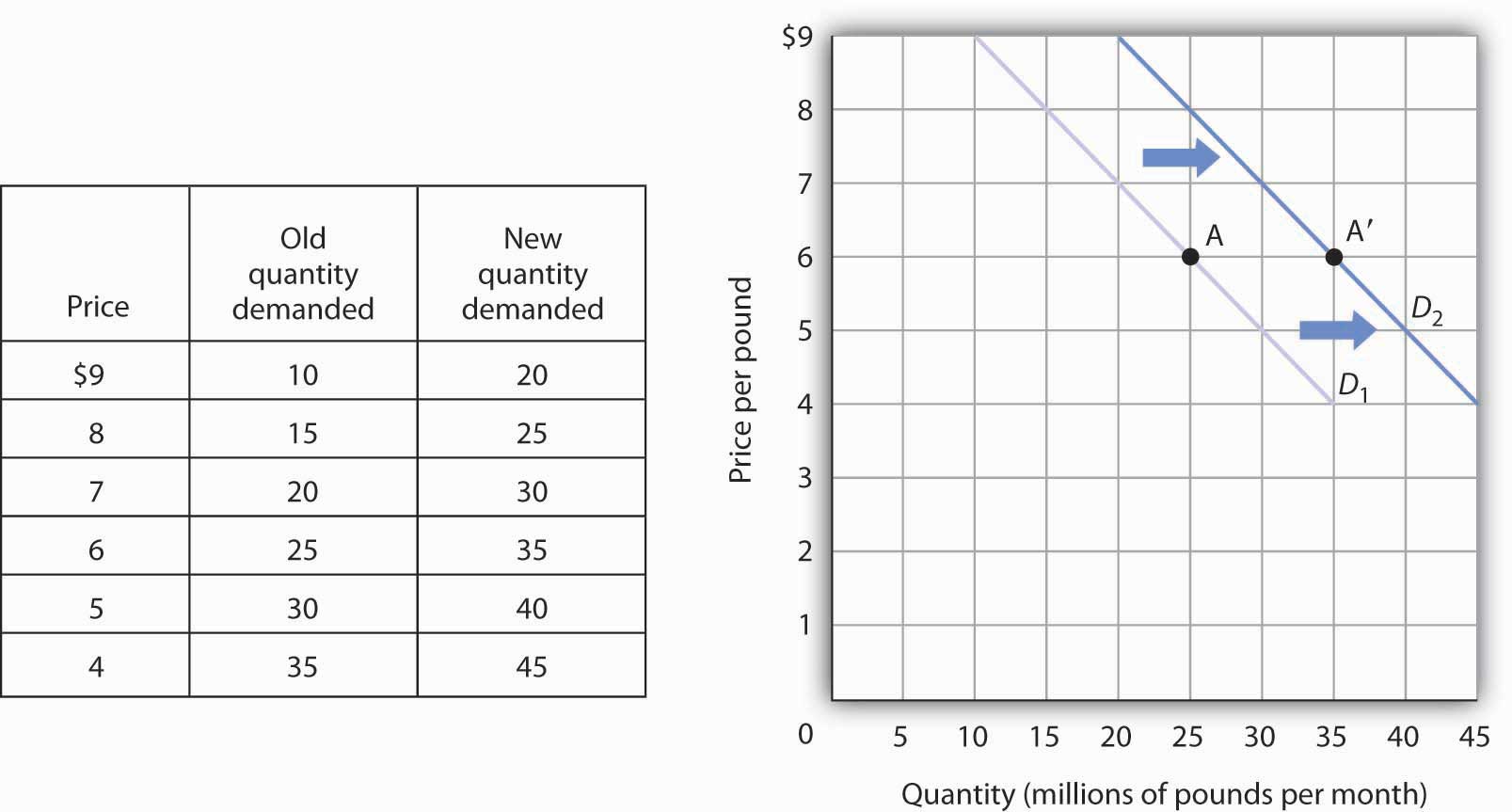

Suppose, for example, that something happens to increase the quantity of coffee demanded at each price. Several events could produce such a change: an increase in incomes, an increase in population, or an increase in the price of tea would each be likely to increase the quantity of coffee demanded at each price. Any such change produces a new demand schedule. Figure 3.2 “An Increase in Demand” shows such a change in the demand schedule for coffee. We see that the quantity of coffee demanded per month is greater at each price than before. We show that graphically as a shift in the demand curve. The original curve, labeled D 1 , shifts to the right to D 2 . At a price of $6 per pound, for example, the quantity demanded rises from 25 million pounds per month (point A) to 35 million pounds per month (point A′).

Figure 3.2 An Increase in Demand

An increase in the quantity of a good or service demanded at each price is shown as an increase in demand. Here, the original demand curve D 1 shifts to D 2 . Point A on D 1 corresponds to a price of $6 per pound and a quantity demanded of 25 million pounds of coffee per month. On the new demand curve D 2 , the quantity demanded at this price rises to 35 million pounds of coffee per month (point A′).

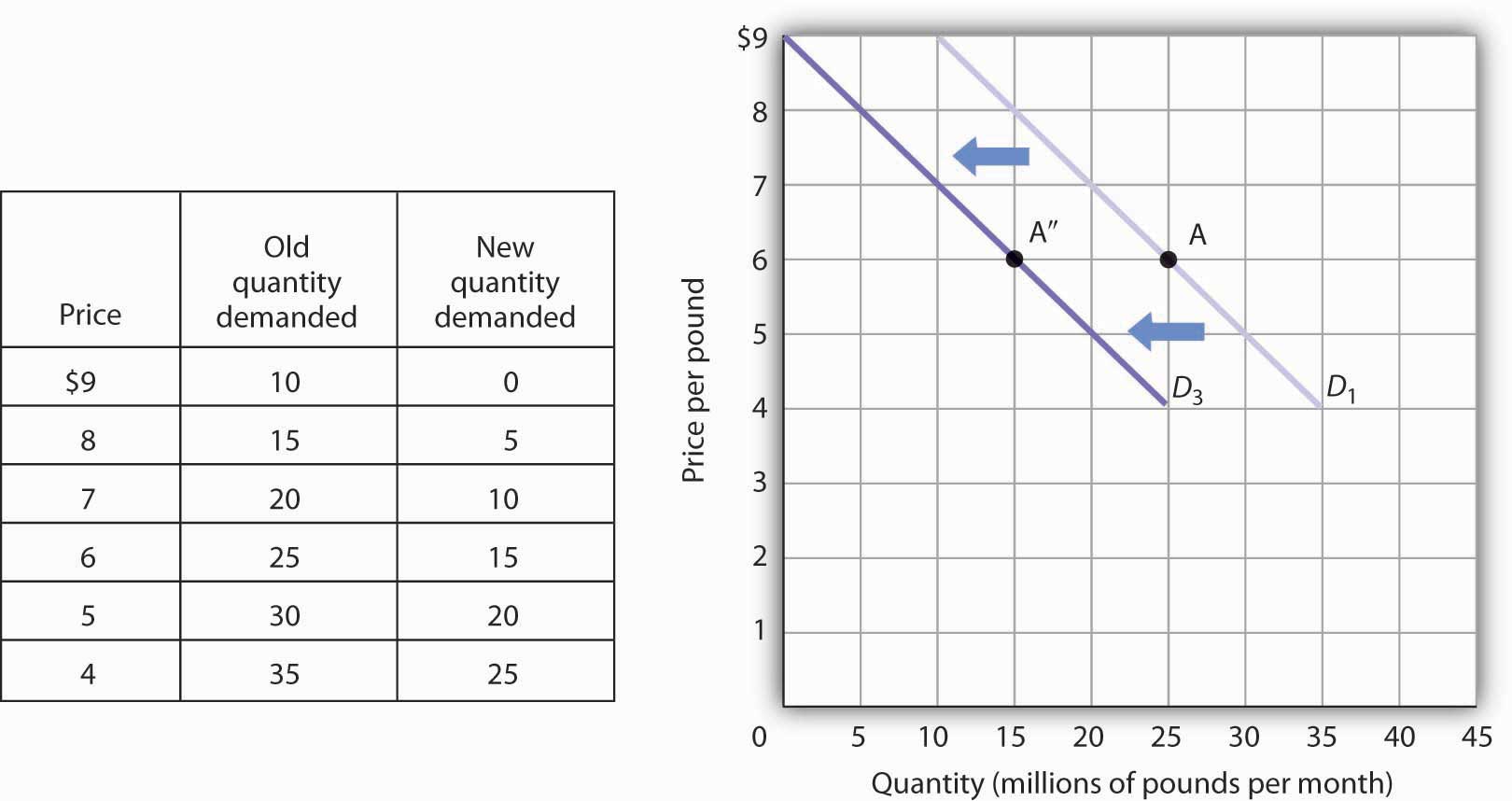

Just as demand can increase, it can decrease. In the case of coffee, demand might fall as a result of events such as a reduction in population, a reduction in the price of tea, or a change in preferences. For example, a definitive finding that the caffeine in coffee contributes to heart disease, which is currently being debated in the scientific community, could change preferences and reduce the demand for coffee.

A reduction in the demand for coffee is illustrated in Figure 3.3 “A Reduction in Demand” . The demand schedule shows that less coffee is demanded at each price than in Figure 3.1 “A Demand Schedule and a Demand Curve” . The result is a shift in demand from the original curve D 1 to D 3 . The quantity of coffee demanded at a price of $6 per pound falls from 25 million pounds per month (point A) to 15 million pounds per month (point A″). Note, again, that a change in quantity demanded, ceteris paribus, refers to a movement along the demand curve, while a change in demand refers to a shift in the demand curve.

Figure 3.3 A Reduction in Demand

A reduction in demand occurs when the quantities of a good or service demanded fall at each price. Here, the demand schedule shows a lower quantity of coffee demanded at each price than we had in Figure 3.1 “A Demand Schedule and a Demand Curve” . The reduction shifts the demand curve for coffee to D 3 from D 1 . The quantity demanded at a price of $6 per pound, for example, falls from 25 million pounds per month (point A) to 15 million pounds of coffee per month (point A″).

A variable that can change the quantity of a good or service demanded at each price is called a demand shifter . When these other variables change, the all-other-things-unchanged conditions behind the original demand curve no longer hold. Although different goods and services will have different demand shifters, the demand shifters are likely to include (1) consumer preferences, (2) the prices of related goods and services, (3) income, (4) demographic characteristics, and (5) buyer expectations. Next we look at each of these.

Preferences

Changes in preferences of buyers can have important consequences for demand. We have already seen how Starbucks supposedly increased the demand for coffee. Another example is reduced demand for cigarettes caused by concern about the effect of smoking on health. A change in preferences that makes one good or service more popular will shift the demand curve to the right. A change that makes it less popular will shift the demand curve to the left.

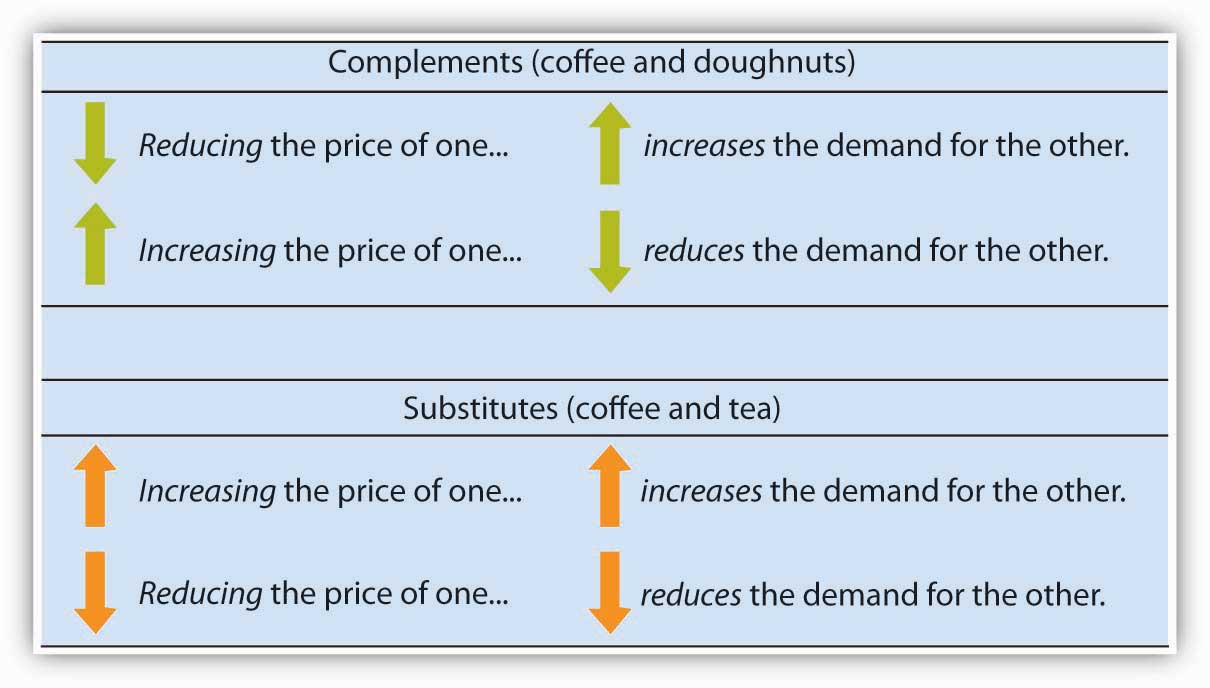

Prices of Related Goods and Services

Suppose the price of doughnuts were to fall. Many people who drink coffee enjoy dunking doughnuts in their coffee; the lower price of doughnuts might therefore increase the demand for coffee, shifting the demand curve for coffee to the right. A lower price for tea, however, would be likely to reduce coffee demand, shifting the demand curve for coffee to the left.

In general, if a reduction in the price of one good increases the demand for another, the two goods are called complements . If a reduction in the price of one good reduces the demand for another, the two goods are called substitutes . These definitions hold in reverse as well: two goods are complements if an increase in the price of one reduces the demand for the other, and they are substitutes if an increase in the price of one increases the demand for the other. Doughnuts and coffee are complements; tea and coffee are substitutes.

Complementary goods are goods used in conjunction with one another. Tennis rackets and tennis balls, eggs and bacon, and stationery and postage stamps are complementary goods. Substitute goods are goods used instead of one another. iPODs, for example, are likely to be substitutes for CD players. Breakfast cereal is a substitute for eggs. A file attachment to an e-mail is a substitute for both a fax machine and postage stamps.

As incomes rise, people increase their consumption of many goods and services, and as incomes fall, their consumption of these goods and services falls. For example, an increase in income is likely to raise the demand for gasoline, ski trips, new cars, and jewelry. There are, however, goods and services for which consumption falls as income rises—and rises as income falls. As incomes rise, for example, people tend to consume more fresh fruit but less canned fruit.

A good for which demand increases when income increases is called a normal good . A good for which demand decreases when income increases is called an inferior good . An increase in income shifts the demand curve for fresh fruit (a normal good) to the right; it shifts the demand curve for canned fruit (an inferior good) to the left.

Demographic Characteristics

The number of buyers affects the total quantity of a good or service that will be bought; in general, the greater the population, the greater the demand. Other demographic characteristics can affect demand as well. As the share of the population over age 65 increases, the demand for medical services, ocean cruises, and motor homes increases. The birth rate in the United States fell sharply between 1955 and 1975 but has gradually increased since then. That increase has raised the demand for such things as infant supplies, elementary school teachers, soccer coaches, in-line skates, and college education. Demand can thus shift as a result of changes in both the number and characteristics of buyers.

Buyer Expectations

The consumption of goods that can be easily stored, or whose consumption can be postponed, is strongly affected by buyer expectations. The expectation of newer TV technologies, such as high-definition TV, could slow down sales of regular TVs. If people expect gasoline prices to rise tomorrow, they will fill up their tanks today to try to beat the price increase. The same will be true for goods such as automobiles and washing machines: an expectation of higher prices in the future will lead to more purchases today. If the price of a good is expected to fall, however, people are likely to reduce their purchases today and await tomorrow’s lower prices. The expectation that computer prices will fall, for example, can reduce current demand.

It is crucial to distinguish between a change in quantity demanded, which is a movement along the demand curve caused by a change in price, and a change in demand, which implies a shift of the demand curve itself. A change in demand is caused by a change in a demand shifter. An increase in demand is a shift of the demand curve to the right. A decrease in demand is a shift in the demand curve to the left. This drawing of a demand curve highlights the difference.

Key Takeaways

- The quantity demanded of a good or service is the quantity buyers are willing and able to buy at a particular price during a particular period, all other things unchanged.

- A demand schedule is a table that shows the quantities of a good or service demanded at different prices during a particular period, all other things unchanged.

- A demand curve shows graphically the quantities of a good or service demanded at different prices during a particular period, all other things unchanged.

- All other things unchanged, the law of demand holds that, for virtually all goods and services, a higher price induces a reduction in quantity demanded and a lower price induces an increase in quantity demanded.

- A change in the price of a good or service causes a change in the quantity demanded—a movement along the demand curve.

- A change in a demand shifter causes a change in demand, which is shown as a shift of the demand curve. Demand shifters include preferences, the prices of related goods and services, income, demographic characteristics, and buyer expectations.

- Two goods are substitutes if an increase in the price of one causes an increase in the demand for the other. Two goods are complements if an increase in the price of one causes a decrease in the demand for the other.

- A good is a normal good if an increase in income causes an increase in demand. A good is an inferior good if an increase in income causes a decrease in demand.

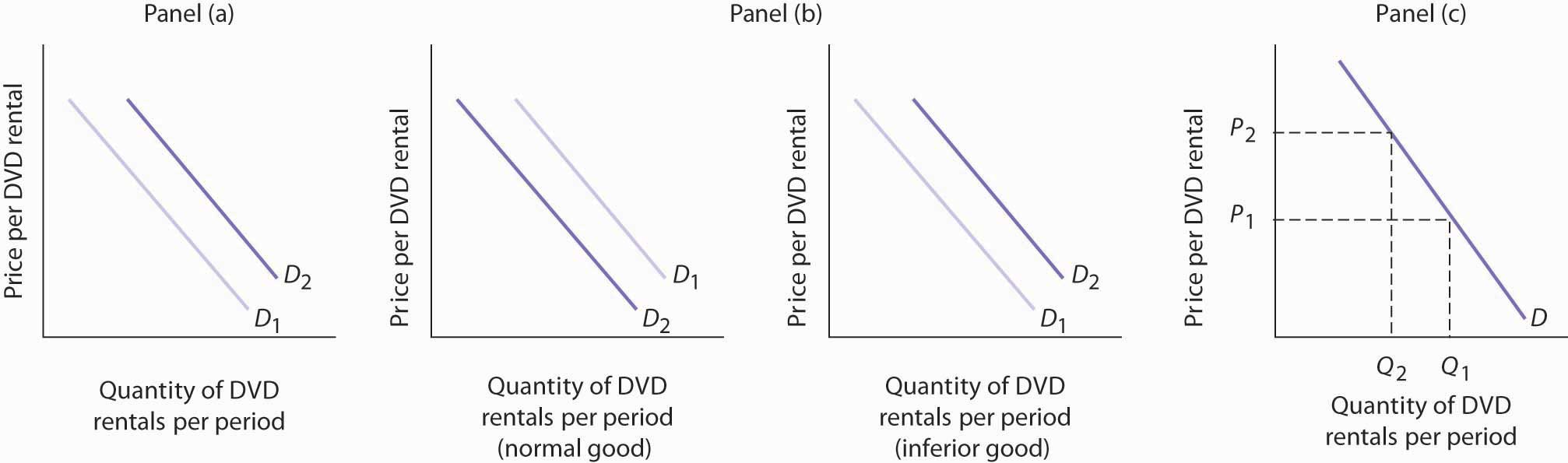

All other things unchanged, what happens to the demand curve for DVD rentals if there is (a) an increase in the price of movie theater tickets, (b) a decrease in family income, or (c) an increase in the price of DVD rentals? In answering this and other “Try It!” problems in this chapter, draw and carefully label a set of axes. On the horizontal axis of your graph, show the quantity of DVD rentals. It is necessary to specify the time period to which your quantity pertains (e.g., “per period,” “per week,” or “per year”). On the vertical axis show the price per DVD rental. Since you do not have specific data on prices and quantities demanded, make a “free-hand” drawing of the curve or curves you are asked to examine. Focus on the general shape and position of the curve(s) before and after events occur. Draw new curve(s) to show what happens in each of the circumstances given. The curves could shift to the left or to the right, or stay where they are.

Case in Point: Solving Campus Parking Problems Without Adding More Parking Spaces

Alden Jewell – The Parking Lot – CC BY 2.0.

Unless you attend a “virtual” campus, chances are you have engaged in more than one conversation about how hard it is to find a place to park on campus. Indeed, according to Clark Kerr, a former president of the University of California system, a university is best understood as a group of people “held together by a common grievance over parking.”

Clearly, the demand for campus parking spaces has grown substantially over the past few decades. In surveys conducted by Daniel Kenney, Ricardo Dumont, and Ginger Kenney, who work for the campus design company Sasaki and Associates, it was found that 7 out of 10 students own their own cars. They have interviewed “many students who confessed to driving from their dormitories to classes that were a five-minute walk away,” and they argue that the deterioration of college environments is largely attributable to the increased use of cars on campus and that colleges could better service their missions by not adding more parking spaces.

Since few universities charge enough for parking to even cover the cost of building and maintaining parking lots, the rest is paid for by all students as part of tuition. Their research shows that “for every 1,000 parking spaces, the median institution loses almost $400,000 a year for surface parking, and more than $1,200,000 for structural parking.” Fear of a backlash from students and their parents, as well as from faculty and staff, seems to explain why campus administrators do not simply raise the price of parking on campus.

While Kenney and his colleagues do advocate raising parking fees, if not all at once then over time, they also suggest some subtler, and perhaps politically more palatable, measures—in particular, shifting the demand for parking spaces to the left by lowering the prices of substitutes.

Two examples they noted were at the University of Washington and the University of Colorado at Boulder. At the University of Washington, car poolers may park for free. This innovation has reduced purchases of single-occupancy parking permits by 32% over a decade. According to University of Washington assistant director of transportation services Peter Dewey, “Without vigorously managing our parking and providing commuter alternatives, the university would have been faced with adding approximately 3,600 parking spaces, at a cost of over $100 million…The university has created opportunities to make capital investments in buildings supporting education instead of structures for cars.” At the University of Colorado, free public transit has increased use of buses and light rail from 300,000 to 2 million trips per year over the last decade. The increased use of mass transit has allowed the university to avoid constructing nearly 2,000 parking spaces, which has saved about $3.6 million annually.

Sources: Daniel R. Kenney, “How to Solve Campus Parking Problems Without Adding More Parking,” The Chronicle of Higher Education , March 26, 2004, Section B, pp. B22-B23.

Answer to Try It! Problem

Since going to the movies is a substitute for watching a DVD at home, an increase in the price of going to the movies should cause more people to switch from going to the movies to staying at home and renting DVDs. Thus, the demand curve for DVD rentals will shift to the right when the price of movie theater tickets increases [Panel (a)].

A decrease in family income will cause the demand curve to shift to the left if DVD rentals are a normal good but to the right if DVD rentals are an inferior good. The latter may be the case for some families, since staying at home and watching DVDs is a cheaper form of entertainment than taking the family to the movies. For most others, however, DVD rentals are probably a normal good [Panel (b)].

An increase in the price of DVD rentals does not shift the demand curve for DVD rentals at all; rather, an increase in price, say from P 1 to P 2 , is a movement upward to the left along the demand curve. At a higher price, people will rent fewer DVDs, say Q 2 instead of Q 1 , ceteris paribus [Panel (c)].

Principles of Economics Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- US & World Economies

- Economic Theory

What Is the Law of Demand?

The Balance / Julie Bang

The law of demand states that all other things being equal, the quantity bought of a good or service is a function of price.

Key Takeaways

- The law of demand affirms the inverse relationship between price and demand. People will buy less of something when its price rises; they'll buy more when its price falls

- The law of demand assumes that all determinants of demand, except price, remain unchanged.

- Demand can be visually represented by a demand curve within a graph called the demand schedule.

- Aside from price, factors that affect demand are consumer income, preferences, expectations, and prices of related commodities. The number of buyers can also affect demand.

- The law of demand can be seen in U.S. monetary policy.

Definition and Examples of the Law of Demand

According to the law of demand, the quantity bought of a good or service is a function of price—with all other things being equal. As long as nothing else changes, people will buy less of something when its price rises. They'll buy more when its price falls.

This relationship holds true as long as "all other things remain equal." That part is so important that economists use a Latin term to describe it: ceteris paribus .

The law of demand can help us understand why things are priced the way they are. For example, retailers use the law of demand every time they offer a sale. In the short term, all other things are equal. Sales are very successful in driving demand. Shoppers respond immediately to the advertised price drop. It works especially well during massive holiday sales, such as Black Friday and Cyber Monday.

How the Law of Demand Works

There are two main ways to visualize the law of demand: the demand schedule and the demand curve.

The demand schedule tells you the exact quantity that will be purchased at any given price. The demand curve plots those numbers on a chart. The quantity is on the horizontal or x-axis , and the price is on the vertical or y-axis .

If the amount bought changes a lot when the price does, then it's called elastic demand . An example of this could be something like buying ice cream. If the price rises too high for your preference, you could easily purchase a different dessert instead.

If the quantity doesn't change much when the price does, that's called inelastic demand . An example of this is gasoline. You need to buy enough to get to work, regardless of the price.

The factors that determine the level of demand are called "determinants." These are also part of the "all other things" that need to be equal under ceteris paribus . The determinants of demand are the prices of related goods or services, income, tastes or preferences, and expectations.

For aggregate demand, the number of buyers in the market is also a determinant.

If the other determinants change, then consumers will buy more or less of the product even though the price remains the same. That's called a shift in the demand curve.

The Law of Demand and the Business Cycle

Politicians and central bankers understand the law of demand very well. The Federal Reserve operates with a dual mandate to prevent inflation while reducing unemployment.

During the expansion phase of the business cycle, the Fed tries to reduce demand for all goods and services by raising the price of everything. It does this with contractionary monetary policy. It raised the fed funds rate, which increases interest rates on loans and mortgages.

That has the same effect as raising prices—first on loans, then on everything bought with loans, and finally everything else.

Of course, when prices go up, so does inflation. But that's not always a bad thing. The Fed has a 2% inflation target for the core inflation rate. The nation's central bank wants that level of mild inflation. It sets an expectation that prices will increase by 2% a year. Demand increases because people know that things will only cost more next year. They may as well buy it now, ceteris paribus .

During a recession or the contraction phase of the business cycle, policymakers have a worse problem. They've got to stimulate demand when workers are losing jobs and homes and have less income and wealth. Expansionary monetary policy lowers interest rates, thereby reducing the price of everything. If the recession is bad enough, it doesn't reduce the price enough to offset the lower income.

In that case, expansionary fiscal policy is needed. During periods of high unemployment, the government may extend unemployment benefits and cut taxes. As a result, the deficit increases because the government's tax revenue falls. Once confidence and demand are restored, the deficit should shrink as tax receipts increase.

The Library of Economics and Liberty. " Demand ." Accessed June 24, 2021.

Saylor Academy. " ECON101: Principles of Microeconomics ." Accessed June 24, 2021.

Corporate Finance Institute. " What Is a Demand Curve? " Accessed June 24, 2021.

Lumen Learning. " Reading: Examples of Elastic and Inelastic Demand ." Accessed June 24, 2021.

California State University (Northridge). " Understand How Various Factors Shift Supply or Demand and Understand the Consequences for Equilibrium Price and Quantity ," Pages 1-2. Accessed June 24, 2021.

University of Wisconsin-Madison. " Supply and Demand ." Accessed June 24, 2021.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. " Stable Prices, Stable Economy: Keeping Inflation in Check Must Be No. 1 Goal of Monetary Policymakers ." Accessed June 24, 2021.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. " Making Sense of the Federal Reserve ." Accessed June 24, 2021.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. " The Fed’s Inflation Target: Why 2 Percent? " Accessed June 24, 2021.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. " A Closer Look at Open Market Operations ." Accessed June 24, 2021.

Federal Reserve. " What Is the Difference Between Monetary Policy and Fiscal Policy, and How Are They Related? ” Accessed June 24, 2021.

Washington State Employment Security Department. " Benefits Extensions ." Accessed June 24, 2021.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Microeconomics

Course: microeconomics > unit 2, law of supply.

- Change in supply versus change in quantity supplied

- Factors affecting supply

- What factors change supply?

- Lesson summary: Supply and its determinants

- Supply and the law of supply

- The law of supply states that a higher price leads to a higher quantity supplied and that a lower price leads to a lower quantity supplied.

- Supply curves and supply schedules are tools used to summarize the relationship between supply and price.

Supply of goods and services

Supply schedule and supply curve.

- A supply schedule is a table that shows the quantity supplied at each price.

- A supply curve is a graph that shows the quantity supplied at each price. Sometimes the supply curve is called a supply schedule because it is a graphical representation of the supply schedule.

The difference between supply and quantity supplied

Attribution:, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Law of demand assignment. This demand curve demonstrates the law of demand. The law of demand states that as the price of a good rises, the quantity demanded of that good will__________. As the price of a good falls, the quantity demanded of that good will_________. Click the card to flip 👆.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like The chart compares the price of graphic T-shirts to the quantity demanded. This chart shows the link between, The vertical axis of a demand curve shows, The point where supply and demand meet and prices are set is called and more.

Transcript. The law of demand states that when the price of a product goes up, the quantity demanded will go down - and vice versa. It's an intuitive concept that tends to hold true in most situations (though there are exceptions). The law of demand is a foundational principle in microeconomics, helping us understand how buyers and sellers ...

In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Introduction to the Law of Demand 2. Assumptions of the Law of Demand 3. Exceptions. Introduction to the Law of Demand: The law of demand expresses a relationship between the quantity demanded and its price. It may be defined in Marshall's words as "the amount demanded increases with a fall in price, and diminishes with a rise in price". Thus it ...

Demand curves will be somewhat different for each product. They may appear relatively steep or flat, and they may be straight or curved. Nearly all demand curves share the fundamental similarity that they slope down from left to right, embodying the law of demand: As the price increases, the quantity demanded decreases, and, conversely, as the price decreases, the quantity demanded increases.

Demand and the law of demand. Emily is a rational consumer who gets utility from socks and music lessons, and she considers both of these goods normal goods. Her marginal utility from socks is 50 utils and the price of socks is $ 5 per pair. Her marginal utility from music lessons is 600 utils and the price of music lessons is $ 60.

The demand schedule (Table 7.10.1 7.10. 1) shows that as price rises, quantity demanded decreases, and vice versa. These points can then be graphed, and the line connecting them is the demand curve (shown by line D in the graph, above). The downward slope of the demand curve again illustrates the law of demand—the inverse relationship between ...

Law Of Demand: The law of demand is a microeconomic law that states, all other factors being equal, as the price of a good or service increases, consumer demand for the good or service will ...

The downward slope of the demand curve again illustrates the law of demand—the inverse relationship between prices and quantity demanded. Demand curves will appear somewhat different for each product. They may appear relatively steep or flat, or they may be straight or curved. Nearly all demand curves share the fundamental similarity that ...

The demand curve is a graph showing the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity demanded. A demand curve can be for an individual consumer or the whole market (market demand curve) Exceptions to the law of demand. Giffen Good. This is good where a higher price causes an increase in demand (reversing the usual law of demand).

Demand represents the buyers in a market. Demand is a description of all quantities of a good or service that a buyer would be willing to purchase at all prices. According to the law of demand, this relationship is always negative: the response to an increase in price is a decrease in the quantity demanded.

The law of demand states that the quantity demanded of a good shows an inverse relationship with the price of a good when other factors are held constant ( cetris peribus ). It means that as the price increases, demand decreases. The law of demand is a fundamental principle in macroeconomics. It is used together with the law of supply to ...

The law of demand is represented by a graph called the demand curve, with quantity demanded on the x-axis and price on the y-axis. Demand curves are downward sloping by definition of the law of demand. The law of demand also works together with the law of supply to determine the efficient allocation of resources in an economy through the ...

Market demand as the sum of individual demand. (Opens a modal) Substitution and income effects and the law of demand. (Opens a modal) Price of related products and demand. (Opens a modal) Change in expected future prices and demand. (Opens a modal) Changes in income, population, or preferences.

The Law of Demand Demand has three components demonstrated by consumers: want, ability to pay, and willingness to pay. Demand is determined by which and what quantity of particular goods and services consumers want, have the ability to afford, and are willing to buy at a particular time. As prices rise for a particular good or service, demand goes

A demand curve thus shows the relationship between the price and quantity demanded of a good or service during a particular period, all other things unchanged. The demand curve in Figure 3.1 "A Demand Schedule and a Demand Curve" shows the prices and quantities of coffee demanded that are given in the demand schedule. At point A, for ...

Definition. The law of demand states that all other things being equal, the quantity bought of a good or service is a function of price. The law of demand affirms the inverse relationship between price and demand. People will buy less of something when its price rises; they'll buy more when its price falls. The law of demand assumes that all ...

Key points. The law of supply states that a higher price leads to a higher quantity supplied and that a lower price leads to a lower quantity supplied. Supply curves and supply schedules are tools used to summarize the relationship between supply and price.