- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Qualitative data analysis and the use of theory.

- Carol Grbich Carol Grbich Flinders University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.554

- Published online: 23 May 2019

The role of theory in qualitative data analysis is continually shifting and offers researchers many choices. The dynamic and inclusive nature of qualitative research has encouraged the entry of a number of interested disciplines into the field. These discipline groups have introduced new theoretical practices that have influenced and diversified methodological approaches. To add to these, broader shifts in chronological theoretical orientations in qualitative research can be seen in the four waves of paradigmatic change; the first wave showed a developing concern with the limitations of researcher objectivity, and empirical observation of evidence based data, leading to the second wave with its focus on realities - mutually constructed by researcher and researched, participant subjectivity, and the remedying of societal inequalities and mal-distributed power. The third wave was prompted by the advent of Postmodernism and Post- structuralism with their emphasis on chaos, complexity, intertextuality and multiple realities; and most recently the fourth wave brought a focus on visual images, performance, both an active researcher and an interactive audience, and the crossing of the theoretical divide between social science and classical physics. The methods and methodological changes, which have evolved from these paradigm shifts, can be seen to have followed a similar pattern of change. The researcher now has multiple paradigms, co-methodologies, diverse methods and a variety of theoretical choices, to consider. This continuum of change has shifted the field of qualitative research dramatically from limited choices to multiple options, requiring clarification of researcher decisions and transparency of process. However, there still remains the difficult question of the role that theory will now play in such a high level of complex design and critical researcher reflexivity.

- qualitative research

- data analysis

- methodologies

Theory and Qualitative Data Analysis

Researchers new to qualitative research, and particularly those coming from the quantitative tradition, have often expressed frustration at the need for what appears to be an additional and perhaps unnecessary process—that of the theoretical interpretation of their carefully designed, collected, and analyzed data. The justifications for this process have tended to fall into one of two areas: the need to lift data to a broader interpretation beyond the Monty Pythonesque “this is my theory and it’s my very own,” to illumination of findings from another perspective—by placing the data in its relevant discipline field for comparison with previous theoretical data interpretations, while possibly adding something original to the field.

“Theory” is broadly seen as a set of assumptions or propositions, developed from observation or investigation of perceived realties, that attempt to provide an explanation of relationships or phenomena. The framing of data via theoretical imposition can occur at different levels. At the lowest level, various concepts such as “role,” “power,” “socialization,” “evaluation,” or “learning styles” refer to limited aspects of social organization and are usually applied to a specific group of people.

At a more complex level, theories of the Middle Range, identified by Robert Merton to link theory and practice, are used to build theory from empirical data. These tend to be discipline specific and incorporate concepts plus variables such as “gender,” “race,” or “class.” Concepts and variables are then combined into meaningful statements, which can be applied to more diverse social groups. For example, in education an investigation of student performance could emphasize such concepts as “safety,” “zero bullying,” “communication,” and “tolerance,” with variables such as “race” and “gender” to lead to a statement that good microsystems and a focus on individual needs are necessary for optimal student performance.

The third and most complex level uses the established or grand theories such as those of Sigmund Freud’s stages of children’s development, Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, or Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems, which have been widely accepted as meaningful across a number of disciplines and provide abstract explanations of the uniformity of aspects of social organization, social behavior, and social change.

The trend in qualitative research regarding the application of chosen levels of theory has been generally either toward theory direction/verification or theory generation, although the two are often intertwined. In the first, a relevant existing theory is chosen early and acts as a point of critical comparison for the data to be collected. This approach requires the researcher to think theoretically as s/he designs the study, collects data, and collates it into analytical groupings. The danger of theory direction is that an over focus on a chosen theoretical orientation may limit what the researcher can access or “see” in the data, but on the upside, this approach can also enable the generation of new theoretical aspects, as it is rare that findings will fall precisely within the implications of existing statements. Theory generation is a much looser approach and involves either one or a range of relevant levels of theory being identified at any point in the research process, and from which, in conjunction with data findings, some new combination or distillation can enhance interpretation.

The question of whether a well-designed study should negate the need for theoretical interpretation has been minimally debated. Mehdi and Mansor ( 2010 ) identified three trends in the literature on this topic: that theory in qualitative research relates to integrated methodology and epistemology; that theory is a separate and additional element to any methodological underpinnings; and that theory has no solid relationship with qualitative research. No clear agreement on any of these is evident. Overall, there appears to be general acceptance that the process of using theory, albeit etically (imposed) or emically (integrated), enhances outcomes, and moves research away from being a-theoretical or unilluminated by other ideas. However, regarding praxis, a closer look at the issue of the use of theory and data may be in order. Theoretical interpretation, as currently practiced, has limits. To begin with, the playing field is not level. In the grounded theory tradition, Glaser and Strauss ( 1967 ) were initially clear that in order to prevent undue influence on design and interpretation, the researcher should avoid reviewing the literature on a topic until after some data collection and analysis had been undertaken. The presumption that most researchers would already be well versed in theory/ies and would have a broad spectrum to draw on in order to facilitate the constant comparative process from which data-based concepts could be generated was found to be incorrect. Glaser ( 1978 ) suggested this lack could be improved at the conceptual level via personal and professional reflexivity.

This issue became even more of a problem with the advent of practice-led disciplines such as education and health into the field of qualitative research. These groups had not been widely exposed to the theories of the traditional social sciences such as sociology, psychology, and philosophy, although in education they would have been familiar with John Dewey’s concept of “pragmatism” linking learning with hands-on activity, and were more used to developing and using models of practice for comparison with current realities. By the mid- 20th century , Education was more established in research and had moved toward the use of middle range theories and the late 20th-century grand theorists: Michel Foucault, with his emphasis on power and knowledge control, and Jurgen Habermas, with his focus on pragmatism, communication, and knowledge management.

In addition to addictive identification with particular levels of theory and discipline-preferred theories and methods, activity across qualitative research seems to fall between two extremes. At one end it involves separate processes of data collection and analysis before searching for a theoretical framework within which to discuss the findings—often choosing a framework that has gained traction in a specific discipline. This “best/most acceptable fit” approach often adds little to the relevant field beyond repetition and appears somewhat forced. At the other extreme there are those who weave methods, methodologies, data, and theory throughout the whole research process, actively critiquing and modifying it as they go, usually with the outcome of creating some new direction for both theory and practice. The majority of qualitative research practice, however, tends to fall somewhere between these two.

The final aspect of framing data lies in the impact of researchers themselves, and the early- 21st-century emphasis is on exposing relevant personal frames, particularly those of culture, gender, socioeconomic class, life experiences such as education, work, and socialization, and the researcher’s own values and beliefs. The twin purposes of this exposure are to create researcher awareness and encourage accountability for their impact on the data, as well as allowing the reader to assess the value of research outcomes in terms of potential researcher bias or prejudice. This critical reflexivity is supposed to be undertaken at all stages of the research but it is not always clear that it has occurred.

Paradigms: From Interactionism to Performativity

It appears that there are potentially five sources of theory: that which is generally available and can be sourced from different disciplines; that which is imbedded in the chosen paradigm/s; that which underpins particular methodologies; that which the researcher brings, and that which the researched incorporate within their stories. Of these, the paradigm/s chosen are probably the most influential in terms of researcher position and design. The variety of the sets of assumptions, beliefs, and researcher practices that comprise the theoretical paradigms, perspectives, or broad world views available to researchers, and within which they are expected to locate their individual position and their research approach, has shifted dramatically since the 1930s. The changes have been distinct and identifiable, with their roots located in the societal shifts prompted by political, social, and economic change.

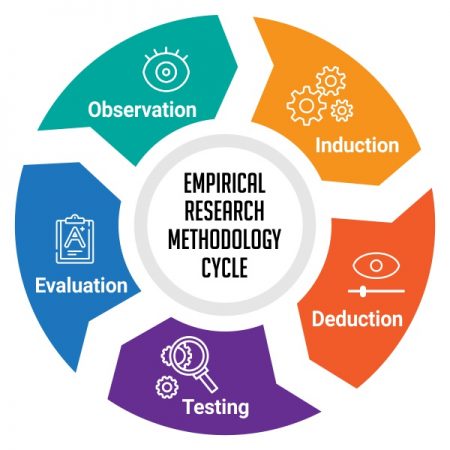

The First Wave

The Positivist paradigm dominated research, largely unquestioned, prior to the early 20th century . It emphasized the distancing of the researcher from his/her subjects; researcher objectivity; a focus on objective, cause–effect, evidence-based data derived from empirical observation of external realities; experimental quantitative methods involving testing hypotheses; and the provision of finite answers and unassailable future predictions. From the 1930s, concerns about the limitations of findings and the veracity of research outcomes, together with improved communication and exposure to the worldviews of other cultures, led to the advent of the realist/post-positivist paradigm. Post-positivism, or critical realism, recognized that certainty in proving the truth of a hypothesis was unachievable and that outcomes were probably limited to falsification (Popper, 1963 ), that true objectivity was unattainable and that the researcher was most likely to impact on or to contaminate data, that both qualitative and quantitative approaches were valuable, and that methodological pluralism was desirable.

The Second Wave

Alongside the worldwide political shifts toward “people power” in the 1960s and 1970s, two other paradigms emerged. The first, the Interpretivist/Constructivist, focused on the social situations in which we as humans develop and how our construction of knowledge occurs through interactions with others in these contexts. This paradigm also emphasized the gaining of an understanding of the subjective views or experiences of the participants being researched, and recognized the impact of the researcher on researcher–researched mutually constructed realities. Here, theory generation is the preferred outcome to explain the what, how, and why of the findings. This usually involves the development of a conceptual model, forged from both the data gained and from the application/integration of relevant theory, to provide explanations for and interpretations of findings, together with a new perspective for the field/discipline.

The second paradigm, termed the Critical/Emancipatory, focused on locating, critiquing, and changing inequalities in society. The identification of the location of systemic power discrepancies or systematic power misuse in situations involving gender, sexuality, class, and race is expected to be followed by moves to right any oppression discovered. Here, the use of theory has been focused more on predetermined concept application for “fit.” This is because the very strong notion of problematic societal structures and power inappropriately wielded have been the dominant underpinnings.

In both the Interpretive and Critical paradigms, researcher position shifted from the elevated and distant position of positivism, to one of becoming equal with those being researched, and the notion of researcher framing emerged to cover this shift and help us—the readers—to “see” (and judge) the researcher and her/his processes of data management more clearly.

The Third Wave

In the 1980s, the next wave of paradigmatic options—postmodernism and poststructuralism—emerged. Postmodernism, with its overarching cultural implications, and poststructuralism, with its focus on language, severely challenged the construction, limitations, and claims to veracity of all knowledge and in particular the use of theory derived from siloed disciplines and confined research methods. Regardless of whether the postmodern/poststructural label is attached to grounded theory, ethnography, phenomenology, action, or evaluative designs, one general aspect that prevails is a focus on language. Language has become viewed as dubious, with notions of “slippage”—the multiple meanings of individual words, and “difference”—the difference and deferral of textual meaning (Derrida, 1970 , 1972 ), adding complexity. Double coding, irony, and juxtaposition are encouraged to further identify meaning, and to uncover aspects of social organization and behavior that have been previously marginalized or made invisible by existing discourses and discursive practices. Texts are seen as complex constructions, and intertextuality is favored, resulting in multiply constructed texts. The world is viewed as chaotic and unknowable; individuals are no longer seen as two dimensional—they are viewed as multifaceted with multiple realities. Complex “truths” are perceived as limited by time and context, requiring multiple data sets and many voices to illuminate them, and small-scale focused local research is seen as desirable. The role of researcher also changed: the politics of position and self-reflexivity dominate and the researcher needs to clearly expose past influences and formerly hidden aspects of his/her life. S/he inhabits the position of an offstage or decentered facilitator, presenting data for the reader to judge.

Theory is used mainly at the conceptual level with no particular approach being privileged. The researcher has become a “bricoleur” (Levi-Strauss, 1962 ) or handyman, using whatever methods or theories that are within reach, to adapt, craft, and meld technological skills with mythical intellectual reflection in order to create unique perspectives on the topic. Transitional interpretations dominate, awaiting further challenges and deconstruction by the next researcher in the field.

The need for multifaceted data sets in the 1990s led inevitably to a search for other research structures, and mixed and multiple methods have become topical. In crossing the divide between qualitative and quantitative approaches, the former initially developed its own sub-paradigms: pragmatist (complimentary communication and shared meanings) and transformative/emancipatory (inequalities in race, class, gender, and disability, to be righted). An increasing focus on multiple methods led to the advent of dialectics (multiple paradigm use) and critical realism (the acceptance of divergent results) (Shannon-Baker, 2016 ). The dilemmas of theory use raised by these changes include whether to segregate data sets and try to explain disparate outcomes in terms of diversity using different theories; whether to integrate them through a homogeneous “smoothing” process—one theory fits all, in order to promote a singular interpretation; or whether to let the strongest paradigm—in terms of data—dominate the theoretical findings.

The Fourth Wave

During the early 21st century , as the third wave was becoming firmly established, the Performative paradigm emerged. The incorporation of fine art–based courses into universities has challenged the prescribed rules of the doctoral thesis, initially resulting in a debate—with echoes of Glaser and Strauss—as to whether theory, if used initially, is too directive, thereby potentially contaminating the performance, or whether theory application should be an outcome to enhance performances, or even whether academic guidelines regarding theory use need to be changed to accommodate these disciplines (Bolt, 2004 ; Freeman, 2010 ; Riley & Hunter, 2009 ). Performativity is seen in terms of “effect,” a notion derived from John Austin’s ( 1962 ) assertion that words and speech utterances do not just act as descriptors of content, they have social force and impact on reality. Following this, a productive work is seen as capable of transforming reality (Bolt, 2016 ). The issue most heard here is the problem of how to judge this form of research when traditional guidelines of dependability, transformability, and trustworthiness appear to be irrelevant. Barbara Bolt suggests that drawing on Austin’s ( 1962 ) terms “locutionary” (semantic meaning), “illocutionary” (force), and “perlocutionary” (effect achieved on receivers), together with the mapping of these effects in material, effective, and discursive domains, may be useful, despite the fact that mapping transformation may be difficult to track in the short term.

During the second decade of the 21st century , however, discussions relating to the use of theory have increased dramatically in academic performative research and a variety of theoreticians are now cited apart from John Austin. These include Maurice Merleu-Ponty ( 1945 and the spatiality of lived events; Jacques Derrida ( 1982 ) on iterability, simultaneous sameness, and difference; Giles Deleuze and Felix Guatarri ( 1987 ) on rituals of material objects and transformative potential; Jean-Francois Lyotard ( 1988 ) on plurality of micro narratives, “affect,” and its silent disruption of discourse; and Bruno Latour ( 2005 ) with regard to actor network theory—where theory is used to engage with rather than to explain the world in a reflective political manner.

In performative doctoral theses, qualitative theory and methods are being creatively challenged. For example, from the discipline of theater and performance Lee Miller and Joanne/Bob Whalley ( 2010 ) disrupt the notion of usual spaces for sincere events by taking their six-hour-long performance Partly Cloudy, Chance of Rain , involving a public reaffirmation of their marriage vows, out of the usual habitats to a service station on a highway. The performance involves a choir, a band, a pianist, 20 performers dressed as brides and grooms, photographers, a TV crew, an Anglican priest, plus 50 guests. The theories applied to this event include an exploration of Marc Auge’s ( 1992 ) conception of the “non-place”; Mikhail Bakhtin’s ( 1992 ) concepts of “dialogism” (many voices) together with “heteroglossia” (juxtaposition of many voices in a dialogue); and Ludwig Wittgenstein’s ( 1953 ) discussion of the “duck rabbit”—once the rabbit is seen (participatory experience) the duck (audience) is always infected by its presence. This couple further challenged the guidelines of traditional doctoral theses by successfully negotiating two doctoral awards for a joint piece of research

A more formal example of a doctoral thesis (Reik, 2014 ) using traditional qualitative approaches has examined at school level the clash of paradigms of performative creative styles of teaching with the neoliberalist focus on testing, curriculum standardization, and student outcomes.

Leah Mercer ( 2012 ), an academic in performative studies, used the performative paradigm in her doctoral thesis to challenge and breach not only the methodological but also the theoretical silos of the quantitative–qualitative divide. The physics project is an original work using live performances of personal storytelling with video and web streaming to depict the memories, preoccupations, and the formative relationship of two women, an Australian and an American, living in contemporary mediatized society. Using scientific theory, Mercer explores personal identity by reframing the principles of contemporary physics (quantum mechanics and uncertainty principle) as aesthetic principles (uncertainty and light) with the physics of space (self), time (memory), light (inspiration), and complementarity (the reconciliation of opposites) to illuminate these experiences.

The performative paradigm has also shifted the focus on the reader, developed in postmodernism, to a broader group—an active audience. Multi-methods have been increased to include symbolic imagery, in particular visual images, as well as sound and live action. The researcher’s role here is often that of performer within a cultural frame, creating and investigating multiple realities and providing the link between the text/script and the audience/public. Theory is either minimized to the level of concepts or used to break through the silos of different disciplines to integrate and reconcile aspects from long-lasting theoretical divides.

In these chronological lines of paradigm shifts, changes in researcher position and changes in the application of theory can clearly be seen. The researcher has moved out of the shadows and into the mainstream; her/his role has shifted from an authoritarian collector and presenter of finite “truths” to a creator and often performer of multiple and disparate data images for the audience to respond to. Theory options have shifted from direction and generation within existing perspectives to creative amalgamations of concepts from disciplines previously rarely combined.

Methodologies: From Anthropology to Fine Arts

It would be a simple matter if all the researcher had to contend with was siting oneself in a particular paradigm/s. Unfortunately, not only have paradigms shifted in terms of researcher position and theoretical usage but so also have methodological choices and research design. One of the most popular methodologies, ethnography, with its roots in classical anthropology and its fieldwork-based observations of action and interaction in cultural contexts, can illustrate the process of methodological change following paradigm shift. If a researcher indicates that he/she has undertaken an ethnographic study, the reader will be most likely to query “which form?”: classical?, critical?, auto?, visual?, ethno drama?, cyber/net?, or performative? The following examples from this methodology should indicate how paradigm shifts have resulted in increasing complexity of design, methods, and interpretive options.

In c lassical ethnography the greatest borrowing is from traditional anthropology in terms of process and tools, and this can be seen with the inclusion of initial time spent in the setting to learn the language of the culture and to generally “bathe” oneself in the environment, often with minimal data collection. This process is supposed to help increase researcher understanding of the culture and minimize the problem of “othering” (treating as a different species/alien). Then a fairly lengthy amount of time is usually spent in the cultural setting either as an observer or as a participant observer to collect as much data as is relevant to answer the research question. This is followed by a return to post-check whether the findings previously gathered have stood the test of time. The analytical toolkit can involve domain analysis, freelists, pilesorts, triads and taxonomies, frame and social network, and event analysis. Truncated mini-ethnographies became more common as time became an issue, but these can still involve years of managing descriptive data, often collected by several participating researchers as seen in Douglas, Rasmussen, and Flanagan’s ( 1977 ) study of the culture of a nudist beach. Shorter versions undertaken by one researcher, for example Sohn ( 2015 ), have explored strategies of teacher and student learning in a science classroom. Theoretical interpretation can be by conceptual application for testing, such as Margaret Mead’s ( 1931 ) testing of the concept of “adolescence”—derived from American culture—in Samoan culture, or, more generally, by concept generation. The latter can be seen in David Rozenhan’s ( 1973 ) investigation of the experience of a group of researcher pseudo-patients admitted to hospitals for the mentally ill in the United States. The main concepts generated were labeling, powerlessness, and depersonalization.

De-colonial ethnography recognizes the “othering” frames of colonial and postcolonial research and takes a position that past colonial supremacy over Third World countries persists in political, economic, educational, and social constructions. Decolonizing requires a critical examination of language, attitudes, and research methods. Kakal Battacharya ( 2016 ) has exposed the micro-discourses of the continuing manifestation of colonial power in a parallel narrative written by a South Asian woman and a white American male. Concepts of colonialism and patriarchy, displayed through the discourses exposed, provide a theoretical critique.

Within critical ethnography , with its focus on power location and alleviation of oppression, Dale Spender ( 1980 ) used structured and timed observations of the styles, quality, and quantity of interaction between staff and students in a range of English classrooms. The theory-directive methodological frames of feminism and gender inequality were applied to identify and expose the lesser time and lesser quality of interaction that teachers had with female students in comparison with that assigned to male students. Widespread distribution of these results alerted education authorities and led to change, in some environments, toward introducing single-sex classrooms for certain topics. This was seen as progress toward alleviating oppressive behaviors. This approach has produced many excellent educational studies, including Peter Willis ( 1977 ) on the preparation of working-class kids for working-class jobs; Michele Fine ( 1991 ) on African American and Latino students who dropped out of a New York high school; Angela Valenzuela ( 1999 ) on emigrant and other under-achievers in American schools; Lisa Patel ( 2013 ) on inclusion and exclusion of immigrants into education; and Jean Anyon ( 1981 ) on social stratification of identical curriculum knowledge in different classrooms

A less concept-driven and more descriptive approach to critical ethnography was emphasized by Phil Carspecken’s hermeneutic approach ( 1996 ), which triggered a move toward data-generated theoretical concepts that could then be used to challenge mainstream theoretical positions.

Post-critical ethnography emphasizes power and ideology and the social practices that contribute to oppression, in particular objectivity, positionality, representation and reflexivity, and critical insufficiency or “antipower.”

Responsibility is shifted to the researcher for the world they create and critique when they interpret their research contexts (Noblit, Flores, & Murillo, 2004 ).

Autoethnography emerged from the postmodern paradigm, with its search for different “truths” and different relationships with readers, and prompted an emphasis on personal experience and documentation of the self in a particular cultural context (Ellis, 2004 ). In order to achieve this, the researcher has to inhabit the dual positions of being the focus of activities, feelings, and emotions experienced in the setting while at the same time being positioned distantly—observing and recording the behaviors of the self in that culture. Well-developed skills of critical reflexivity are required. The rejection of the power-laden discourses/grand theories of the past and the emphasis on transitional explanations has resulted in minimal theorizing and an emphasis on data display, the reader, and the reader’s response. Open presentations of data can be seen in the form of narrative storytelling, or re-presentations in the form of fiction, dramatic performances, and poetry. Carolyn Ellis ( 2004 ) has argued that “story is theory and theory is story” and our “making sense of stories” involves contributing to a broader understanding of human existence. Application/generation of concepts may also occur, and the term “Critical Autoethnography” has been used (Hughes & Pennington, 2017 ), particularly where experiences of race, class, or gender inequality are being experienced. Jennifer Potter ( 2015 ) used the concept “whiteness of silence” to introduce a critical race element into her autoethnographic experience of black–white racial hatred experiences within a university class on African American communication in which she was a student.

Visual ethnography uses a variety of tools, including photography, sketches, movies, social media, the Web and virtual reality, body art, clothing, painting, and sculpture, to demonstrate and track culture. This approach has been available for some time both as a methodology in its own right and as a method of data collection. An example of this approach, which mixes classical and visual ethnography, is Philippe Bourgois and Jeff Schonberg’s 12-year study of two dozen homeless heroin injectors and crack smokers living under a freeway overpass in San Francisco ( 2009 ). Their data comprised extensive black and white photos, dialogue, taped conversations, and fieldwork observation notes. The themes of violence, race relations, family trauma, power relations, and suffering were theoretically interpreted through reworked notions of “power” that incorporated Pierre Bourdieu’s ( 1977 , 1999 ) concepts of “symbolic violence”—linking observed practices to social domination, and “habitus”—an individual’s personal disposition comprising unique feelings and actions grounded in biography and history; Karl Marx’s “lumpen” from “lumpenproletariat” ( 1848 ), the residual class—the vagrants and beggars together with criminal elements that lie beneath the labor force; and Michel Foucault’s “biopower” ( 1978 , 2008 )—the techniques of subjugation used by the state on the population, and “governmentality” ( 1991 )—where individuals are disciplined through institutions and the “knowledge–power” nexus. The ideas of these three theorists were used to create and weave a theory of “lumpen abuse” to interpret the lives of the participants.

Ethno Drama involves transforming the results from an ethnographic study into a performance to be shared, for example the educational experiences of children and youth (Gabriel & Lester, 2013 ). The performance medium can vary from a film (Woo, 2008 ), an article presented in dramatic form (Carter, 2014 ), or more usually a play script to be staged for an audience in a theater (Ethno Theater). One of the main purposes is to provide a hearing space for voices that have been marginalized or previously silenced. These voices and their contexts can be presented by research participants, actors, or the research team, and are often directed at professionals from the field. Audience-based meetings to devise recommendations for further action may follow a performance. Because of the focus on inequality, critical theory has been the major theoretical orientation for this approach. The structure of the presentation invites audiences to identify situations of oppression, in the hope that this will inform them sufficiently to enable modification of their own practices or to be part of the development of recommendations for future change.

Lesnick and Humphrie ( 2018 ) explored the views of identity of LGBTQ+ youth between 14 and 24 years of age via interviews and online questionnaires, the transcriptions of which were woven into a script that was performed by actors presenting stories not congruent with their own racial/gender scripts in order to challenge audience expectations and labels. The research group encouraged the schools where they performed to structure discussion groups to follow the school-located performances. The scripts and discussions revealed and were lightly interpreted through concepts of homelessness, racism, and “oppression Olympics”—the way oppressed people sometimes view one another in competition rather than in solidarity. These issues were found to be relevant to both school and online communities. Support for these young people was discovered to be mostly from virtual sources, being provided by dialogues within Facebook groups.

Cyber/net or/virtual ethnographies involve the study of online communities within particular cultures. Problems which have emerged from the practice of this approach include; discovery of the researcher lurking without permission on sites, gaining prior permission which often disturbs the threads of interaction, gaining permission post–data collection but having many furious people decline participation, the “facelessness” of individuals who may have uncheckable multiple personas, and trying to make sense of very disparate data in incomplete and non-chronological order.. There has been acceptance that online and offline situations can influence each other. Dibbell ( 1993 ) demonstrated that online sexual violence toward another user’s avatar in a text-based “living room” reduced the violated person to tears as she posted pleas for the violator to be removed from the site. Theoretical interpretation at the conceptual level is common; Michel Foucault’s concept of heterotopia ( 1967 , 1984 ) was used to explain such spatio-temporal prisons as online rooms. Heterotropic spaces are seen as having the capacity to reflect and distort real and imagined experiences.

Poststructural ethnography tracks the instability of concepts both culturally and linguistically. This can be demonstrated in the deconstruction of language in education (Lather, 2001 ), particularly the contradictions and paradoxes of sexism, gender, and racism both in texts and in the classroom. These discourses are implicated in relations of power that are dynamic and within which resistance can be observed. Poststructuralism accepts that texts are multiple, as are the personas of those who created them, and that talk such as that which occurs in a classroom can be linked with knowledge control. Walter Humes ( 2000 ) discovered that the educational management discourses of “community,” “leadership,” and “participation” could be disguised by such terms as “learning communities” and “transformational leadership.” He analyzed the results with a conceptual framework derived from management theory and policy studies and linked the findings with political power.

Performative ethnography , from the post-postmodern paradigm, integrates the performances of art and theater with the focus on culture of ethnography (Denzin, 2003 ). A collaborative performance ethnography (van Katwyk & Seko, 2017 ) used a poem re-presenting themes from a previous research study on youth self-harming to form the basis of the creation of a performative dance piece. This process enabled the researcher participants to explore less dominant ways of knowing through co-learning and through the discovery of self-vulnerability. The research was driven by a social justice-derived concern that Foucault’s notion of “sovereignty” was being implemented through a web of relations that commodified and limited knowledge, and sanctioned the exploitation of individuals and communities.

This exploration of the diversity in ethnographic methods, methodologies, and interpretive strategies would be repeated in a similar trek through the interpretive, critical, postmodern, and post-postmodern approaches currently available for undertaking the various versions of grounded theory, phenomenology, feminist research, evaluation, action, or performative research.

Implications of Changes for the Researcher

The onus is now less on finding the “right” (or most familiar in a field) research approaches and following them meticulously, and much more on researchers making their own individual decisions as to which aspects of which methodologies, methods and theoretical explanations will best answer their research question. Ideally this should not be constrained by the state of the discipline they are part of; it should be equally as easy for a fine arts researcher to carry out a classical ethnography with a detailed theoretical interpretation derived from a grand theorist/s as it would be for a researcher in law to undertake a performative study with the minimum of conceptual insights and the maximum of visual and theoretical performances. Unfortunately, the reality is that trends within disciplines dictate publication access, thereby reinforcing the prevailing boundaries of knowledge.

However, the current diversity of choice has indeed shifted the field of qualitative research dramatically away from the position it was in several decades ago. The moves toward visual and performative displays may challenge certain disciplines but these approaches have now become well entrenched in others, and in qualitative research publishing. The creativity of the performative paradigm in daring to scale the siloed and well-protected boundaries of science in order to combine theoretical physics with the theories of social science, and to re-present data in a variety of newer ways from fiction to poetry to researcher performances, is exciting.

Given that theoretical as well as methodological and methods’ domains are now wide open to researchers to pick and choose from, two important aspects—justification and transparency of process—have become essential elements in the process of convincing the reader.

Justification incorporates the why of decision-making. Why was the research question chosen? Why was the particular paradigm, or paradigms, chosen best for the question? Why were the methodology and methods chosen most appropriate for both the paradigm/s and research question/s? And why were the concepts used the most appropriate and illuminating for the study?

Transparency of process not only requires that the researcher clarifies who they are in the field with relation to the research question and the participants chosen, but demands an assessment of what impact their background and personal and professional frames have had on research decisions at all stages from topic choice to theoretical analysis. Problems faced in the research process and how they were managed or overcome also requires exposition as does the chronology of decisions made and changed at all points of the research process.

Now to the issue of theory and the question of “where to?” This brief walk through the paradigmatic, methodological, and theoretical changes has demonstrated a significant move from the use of confined paradigms with limited methodological options to the availability of multiple paradigms, co-methodologies, and methods of many shades, for the researcher to select among Regarding theory use, there has been a clear move away from grand and middle range theories toward the application of individual concepts drawn from a variety of established and minor theoreticians and disciplines, which can be amalgamated into transitory explanations. The examples of theoretical interpretation presented in this article, in my view, very considerably extend, frame, and often shed new light on the themes that have been drawn out via analytical processes. Well-argued theory at any level is a great enhancer, lifting data to heights of illumination and comparison, but it could equally be argued that in the presence of critical researcher reflexivity, complex, layered, longitudinal, and well-justified design, meticulous analysis, and monitored audience response, it may no longer be essential.

Bibliography

- Eco, U. (1979). The role of the reader . Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Gadamer, H. (1989). Truth and method ( J. Weinheimer & D. Marshall , Trans.). NY: Crossroad.

- Grbich, C. (2004). New approaches in social Research . London, U.K.: SAGE.

- Grbich, C. (2013). Qualitative data analysis: An introduction . London, U.K.: SAGE.

- Lincoln, Y. , & Denzin, N. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies: Contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln , Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Lyotard, J. (1983). Answering the question: What is post modernism? In E. Hassan & S. Hassan (Eds.), Innovation and renovation . Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Pink, S. (2012). Advances in visual methodology . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Riley, S. , & Hunter, L. (Eds.). (2009). Mapping landscapes for performance as research . London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tinkler, P. (2011). Using photography in social and historic research . New Dehli, India: SAGE.

- Vis, F. , & Thelwall, M. (2012). Researching social media . New Dehli, India: SAGE.

- Von Hantelmann, D. (2010). How to do things with art . Zurich, Switzerland: JRP Ringier.

- Anyon, J. (1981). Social class and school knowledge . Curriculum Inquiry , 11 (1), 3–42.

- Auge, M. (1992). Non-Places: An introduction to supermodernity ( John Howe ). London, U.K.: Verso.

- Augé, M. (1995). Non-places: An introduction to anthropology of supermodernity . London, U.K.: Verso.

- Austin, J. (1962). How to do things with words [The William James Lectures, 1955]. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

- Bakhtin, M. (1992). The dialogic imagination: Four essays . Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Battacharya, K. , & Gillen, N. (2016). Power, race and higher education: A cross-cultural parallel narrative . Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense.

- Bolt, B. (2004). Art beyond representation: The performative power of the image . London, U.K.: I.B Tauris.

- Bolt, B. (2016). Artistic research: A performative paradigm? Parse. #3 Repetitions and Reneges . Gothenburg, Sweden: University of Gothenburg.

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice . Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1999) The Weight of the world: Social suffering in contemporary society . Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Press.

- Bourgois, P. , & Schonberg, J. (2009). Righteous dopefiend: Homelessness, addiction, and poverty in urban America . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Carspecken, P. (1996). Critical ethnography in educational research . New York: Routledge.

- Carter, M. (2014). The teacher monologues: Exploring the identities and experiences of artist-teachers . Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense.

- Deleuze, G. , & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia ( B. Massumi , Trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Denzin, N. (2003). Performance ethnography : Critical pedagogy and the politics of culture . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Derrida, J. (1970). Structure, sign and play in the discourse of human sciences lecture presented at johns hopkins university , October 21, 1966.

- Derrida, J. (1972). Margins of philosophy: Plato to footnotes ( A. Bass , Trans.). Sussex, U.K.: Brighton and Harvester Press.

- Derrida, J. (1982). Sending: On representation . Social Research , 49 (2), 294–326.

- Dewey, J. (1998). The essential Dewey ( L. Hickman & T. Alexander , Eds.). (2 vols.) Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Dibbell, J. (1993). A rape in cyberspace from chapter 1 of My Tiny Life . Published in The Village Voice .

- Douglas, J. , Rasmussen, P. , & Fanagan, C. (1977). The nude beach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Ellis, C. (2004). The ethnographic I: A methodological novel about autoethnography . Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira.

- Fine, M. (1991). Framing dropouts: Notes on the politics of an urban high school . New York, NY: SUNY Press.

- Foucault, M. (1967, 1984). Des espaces autres (J. Miscowiec, Trans.). [ Of other spaces: Utopias and heterotropias]. Archtecture/Mouvement/Continuite , October.

- Foucault, M. (1978). Security, territory, population. Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–1978 ( A. Davidson , Ed.). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Foucault, M. (1991). Studies in governmentality: Two lectures by and an interview with Michel Foucault ( G. Burchell , C. Gordon , & and P. Miller , Eds.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Foucault, M. (2008). The birth of biopolitics . Lectures at the Collège de France 1978–1979 ( M. Senellart , Ed, Trans.; G. Burchell , Trans.). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. (First published as Naissance de la Biopolitique 2004).

- Freeman, J. (2010). Blood, sweat and theory: Research through practice in performance . Faringdon, U.K.: Libri.

- Freud, S. (1953–1974). The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud ( J. Strachey , Trans. and Ed.) (24 Vols). London, U.K.: Hogarth and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

- Gabriel, R. , & Lester, J. (2013). Performances of research: Critical issues in K–12 education . New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Glaser, B. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the theory of grounded theory . Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. , & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . London: Aldine.

- Hughes, S. , & Pennington, J. (2017). Autoethnography: Process, product and possibility for critical social research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Humes, W. (2000). The discourses of educational management . Journal of Educational Enquiry , 1 (1).

- Lather, P. (2001). Postmodernism, post-structuralism and post(critical) ethnography: Of ruins, aporias and angels. In P. Atkinson , A. Coffey , S. Delamont , J. Lofland , & L. Lofland (Eds.), Handbook of ethnography . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor–network theory . Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

- Lesnick, E. , & Humphrie, J. (2018). Amplifying youth voices through ethnodrama research . Washington, DC: National Association of Independent Schools.

- Levi-Strauss, C. (1962). The savage mind ( La pensee sauvage) ( G. Weidenfield & Nicholson Ltd. , Trans.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lyotard, J. (1988). Peregrinations: Law, form, event . The Wellek Library lectures at the University of California, Irvine. New York, NY.: Columbia University Press.

- Marx, K. , & Engels, F. (1848). The Communist Manifesto ( S. Moore , Trans.).

- Mead, M. (1931). The life of a Samoan girl: ALL TRUE. The record of actual adventures that have happened to ten women of today . New York, NY.: Brewer, Warren and Putnam.

- Mehdi, T. , & Mansor, A. (2010). A General perspective on the role of theory in qualitative research . Journal of International Social Research , 3 (11).

- Mercer, L. (2012). The Physics Project. In L. Mercer , J. Robson , & D. Fenton (Eds.), Live research: Methods of practice led inquiry in research . Nerang: Queensland, Ladyfinger.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945). Phénoménologie de la Perception . Paris, France: Editions Gallimard.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (2005). Phenomenology of perception ( D. Landes , Trans.). London, U.K.: Routledge.

- Merton, R. (1968). Social theory and social structure . New York, NY: Free Press.

- Miller, L. , & Whalley, J. (2010). Case Study 11: Partly cloudy, chance of rain. In J. Freeman (Ed.), Blood, sweat and theory: Research through practice in performance . Faringdon, U.K.: Libri.

- Noblit, G. , Flores, S. , & Nurillo, E. (2004). Postcritical ethnography: Reinscribing critique . New York: Hampton Press.

- Patel, L. (2013). Youth held at the border: Immigration, education and the politics of inclusion . New York, NY: Columbia University Teacher’s College Press.

- Piaget, J. (1936). Origins of intelligence in the child . London, U.K.: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Popper, K. (1963). Science: Conjectures and refutations. Online lecture transcript .

- Potter, J. (2015). The whiteness of silence: A critical autoethnographic tale of a strategic rhetoric . Qualitative Report , 20 (9), 7.

- Reik, R. (2014). Arts education in a culture of performativity: A case study of what is valued in one Queensland school community . (Doctoral dissertation), Griffith University, Brisbane.

- Riley, S. R. , & Hunter, L. (Eds.). (2009). Mapping landscapes for performance as research . London, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rosenhan, D. (1973). On being sane in insane places . Science , 17 (January), 250–258.

- Shannon-Baker, P. (2016). Making paradigms meaningful in mixed methods research . Journal of Mixed Methods Research , 10 (4).

- Sohn, L. (2015). Ethnographic case study of a high school science classroom: Strategies in STEM education . (Doctoral dissertation). Texas A&M University, Corpus Christi, Texas.

- Spender, D. (1980). Talking in class. In D. Spender & E. Sarah (Eds.), Leaming to lose: Sexism and education . London, U.K.: Women’s Press.

- Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling: U.S.–Mexican youth and the politics of caring . Albany: SUNY.

- van Katwyk, T. , & Seko, Y. (2017). Knowing through improvisational dance: A collaborative autoethnography . Forum: Qualitative Social Research , 18 (2), 1.

- Willis, P. (1977). Learning to labour . New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical investigations ( G. Anscombe , Trans.). Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell.

- Woo, Y. (2008). Engaging new audiences: Translating research into popular media. Educational Researcher , 37 (6), 321–329.

Related Articles

- Autoethnography

- Risky Truth-Making in Qualitative Inquiry

- Ethnography and Education

- Qualitative Design Research Methods

- Qualitative Approaches to Studying Marginalized Communities

- Arts Education Research

- Poststructural Temporalities in School Ethnography

- Détournement as a Qualitative Method

- Ethnographies of Education and Anthropological Knowledge Production

- Network Ethnography as an Approach for the Study of New Governance Structures in Education

- Black Feminist Thought and Qualitative Research in Education

- Poetic Approaches to Qualitative Data Analysis

- Performance-Based Ethnography

- Complexity Theory as a Guide to Qualitative Methodology in Teacher Education

- Observing Schools and Classrooms

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 23 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

Character limit 500 /500

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

5 Philosophical Approaches to Qualitative Research

Renée Spencer, School of Social Work, Boston University

Julia M. Pryce, School of Social Work, Loyola University, Chicago

Jill Walsh, Department of Sociology, Boston University

- Published: 04 August 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter reviews some of the major overarching philosophical approaches to qualitative inquiry and includes some historical background for each. Taking a “big picture” view, the chapter discusses post-positivism, constructivism, critical theory, feminism, and queer theory and offers a brief history of these approaches; considers the ontological, epistemological, and axiological assumptions on which they rest; and details some of their distinguishing features. In the last section, attention is turned to the future, identifying three overarching, interrelated, and contested issues with which the field is being confronted and will be compelled to address as it moves forward: retaining the rich diversity that has defined the field, the articulation of recognizable standards for qualitative research, and the commensurability of differing approaches.