Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 20 July 2021

Effectiveness of the flipped classroom model on students’ self-reported motivation and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

- José María Campillo-Ferrer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8570-3749 1 na1 &

- Pedro Miralles-Martínez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9143-2145 1 na1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 176 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

50 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

This study investigates the effects of the flipped classroom on Education students’ perceptions of their learning and motivation during the current pandemic. The sample consisted of 179 student teachers from the Faculty of Education of the University of Murcia in the academic year 2020–2021, in which the flipped classroom model was implemented. Identical surveys were administered and examined through both descriptive statistics and non-parametric tests. Statistically significant differences were found between pre-tests and post-tests with experienced students scoring higher on average in the latter. Most students had a positive perception about the flipped classroom, noting the advantage of practical in-class activities, as well as increased self-autonomy in learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Content validity of the Constructivist Learning in Higher Education Settings (CLHES) scale in the context of the flipped classroom in higher education

Turki Mesfer Alqahtani, Farrah Dina Yusop & Siti Hajar Halili

The implementation of a flipped classroom approach at a UK dental school

Rebecca S. L. Binnie & Stephen J. Bonsor

Nudge or not, university teachers have mixed feelings about online teaching

Sanchayan Banerjee, Beatriz Jambrina-Canseco, … Jenni Carr

Introduction

The increasing development of digital technologies and their application in education facilitates new learning ecologies that offer students new web-based learning opportunities and resources. This rapid spread of interactive technologies has facilitated the adoption of innovative approaches in higher education that help to promote collaborative learning, exploration, and research in online networked learning environments. It is in this context that alternative approaches to teacher-centered instruction have arisen and made a breakthrough in tertiary education.

In this line, the development of innovative student-centered approaches has encouraged teachers to rethink educational processes to shift the focus from them to the students, facilitate student participation, develop practical thinking, and improve digital skills (Wright, 2011 ).

Technology-driven models, such as the flipped classroom (FC), which provides students with direct access to video lectures, slides, and other teaching resources on online educational platforms, have gradually gained visibility and relevance (Bergmann and Sams, 2012 ). This discussion-oriented approach has accelerated well-structured independent learning, allowing teachers to provide feedback and assistance through innovative resources and learning management systems (LMS) in parallel with the implementation of collaborative problem-solving activities and group discussions in face-to-face lessons (López et al., 2016 ).

This is even more true at the present time due to the extreme circumstances. Undoubtedly, these technology-based approaches have become a greater priority during the COVID-19 pandemic as a consequence of the great disruption the virus is causing. In particular, the increasing restrictions recommended by the World Health Organization and other international institutions on disease control and prevention are profoundly affecting the ways in which we interact with each other, and the methods by which teachers teach and students learn and work (World Health Organization, 2020 ). Obviously, this completely changes the educational landscape, which includes not only teaching modes but also individual and collective practices on how to proceed (Dhawan, 2020 ; Fatani, 2020 ). This is particularly relevant for tertiary institutions such as universities or colleges, where a wide variety of classroom components, namely lectures, tutorials, or workshops, are being adapted to the global pandemic (Naw, 2020 ). In planning for the 2020-21 academic year, it was critical to consider certain constraints due to the evolution of the pandemic that has involved measures such as limiting classroom capacity and reducing face-to-face interactions. The restrictions introduced have even led to the suspension of classes and workshops in certain faculties or for specific groups of university students at some point during 2020 and 2021.

Regardless of the challenges, it is imperative that university programs continue to provide effective educational services (Tang et al., 2020 ). For this reason, a wide variety of mechanisms have been put in place to ensure that teaching is carried out on a regular basis. Academics in all areas of study have re-examined their teaching resources and found new options for engaging students in light of the current crisis. In these unfavorable conditions, innovative approaches based on distance conferencing technology and online tools play an important role at this time of great tension (Villa et al., 2020 ).

Several recent research papers have examined the intrinsic and extrinsic results of these teaching innovations, finding that these approaches can foster learning either in fully online or blended academic environments, even when it is mandatory to shift from one mode to another because of the present pandemic circumstances. Chick et al. ( 2020 ) offer several solutions to mitigate the risk of virus spread, including the FC model, teleconferencing, and online practice, with positive outcomes, as participants were satisfied with the format and were interested in continuing to learn without regularly attending face-to-face lectures. Comparative research was conducted by Latorre-Cosculluela et al. ( 2021 ), who concluded that participants were inclined to take a more active role in their own learning process by developing 21st-century skills (e.g., critical thinking or creativity) under the FC model rather than passively listening to direct instruction. In this regard, other studies highlighted the relevance of videos, recorded lectures, and group discussions, among other digital resources, to foster discussions, stimulate student learning and divert attention away from the current disruption caused by the pandemic (Agarwal and Kaushik, 2020 ; Guraya, 2020 ). As can be noted from the above-mentioned studies, the importance of increasing satisfaction and engagement during the unusual situation of COVID-19 is fundamental for educators to adopt strategic decisions to develop a culture of engagement among students. In this sense, Collado-Valero et al. ( 2021 ) identified a significant increase in the use of different online digital resources under the FC approach in a Spanish higher education context, mainly those related to video and audio resources, which provided a greater number of opportunities for students to share their learning experiences through a virtual space. Other research studies also confirm the distinctive rise of flipped learning, whereby students access information and have more opportunities to interact with each other, due to the wide range of possibilities for sharing opinions and ideas offered by these virtual scenarios. In particular, Colomo-Magaña et al. ( 2020 ) surveyed 123 trainee teachers who had been learning under the flipped-top classroom model during the 19/20 academic year. They concluded that the application of this flexible methodology promoted the development of oral skills and the improvement of learning abilities. They also highlighted time optimization as one of the benefits indicated by the participants in the survey. With the same purpose of contributing to the promotion of student learning achievement and engagement despite pandemic constraints, Smith and Boscak ( 2021 ) examined standard flipped classroom pedagogy, in which students were provided with self-learning educational resources, e.g., pre-class videos or case studies, together with interactive online lectures in which learning topics were revisited and discussed. They noted both the students’ satisfaction with the approach invested by the flexible and engaging material used and their subsequent confidence in the skills developed during the course. In parallel, Monzonís et al. ( 2020 ) examined the perceptions of pedagogy students who followed a flipped methodology during the COVID-19 crisis and found that most of them had improved their digital skills and increased their motivation thanks to this methodology. Despite these clear benefits for skills development and active participation of students, there are still some challenges that need to be addressed in more detail and that may be mainly related to teachers, students, or technological requirements. Authors such as Agung et al. ( 2020 ) highlighted some technology-based problems when they found that most students surveyed were not enthusiastic about online learning mainly due to lack of access to the internet and other technological resources, which may be revealing the problem of the digital divide. The abrupt shift towards e-learning since spring 2020 has had other tangible web-based limits, which have been indicated by similar studies, namely over-reliance on the proper functioning of technology or lack of personal contact in video conferences due to the marked contrast caused by the teaching-learning environment switch (Goksu and Duran, 2020 , Clark-Wilson et al., 2020 ). The challenges related to teachers may be related to their difficulties in dealing with emerging technology in such a short space of time. In this regard, ElSaheli-Elhage ( 2021 ) noted that some educators admitted that they are not digitally literate enough to cope with regular online teaching activities during the pandemic. In this respect, Cevikbas and Kaiser ( 2020 ) pointed out another drawback related to digital teaching, which is closely linked to the subject-specific content needed for effective flipped teaching. They highlighted the problems for teachers in identifying adapted learning materials that successfully meet the specific needs of their students or in creating their own lecture videos, slides, infographics, and other learning resources via online platforms. Regarding student-related challenges during the current crisis, some authors have identified students’ depressive symptoms and that signs of anxiety soar in online learning programs due to the perception of lagging behind academically under these unusual conditions (Islam et al., 2020 ). The influence of physical distance or the increase in response time when answering queries and providing academic assistance in asynchronous lessons may be other factors that cause these feelings of psychological unease (Ardan et al., 2020 ).

Therefore, further research and reflection are needed on the application of these innovative models and strategies in these new learning scenarios to improve understanding and adjust these web-based approaches according to the increasing and progressive demands and needs of the learners.

The aim of this research is to analyze the effect that the FC model had on the students’ perceptions of their learning process and progress and their levels of motivation. To achieve this aim, the following research objectives were defined:

RO1: To examine students’ views on the effects that the FC model had on their motivation levels at the beginning and end of the core unit during the pandemic period, and in particular:

To analyze their opinions on the impact this model had, as well as the variety of techniques and strategies used on their level of motivation according to the gender of the participants.

To examine their impressions of the effects of this model, as well as the variety of techniques and strategies used on their level of motivation according to their experience under this approach.

To analyze their impressions of the effects this model had, as well as the variety of techniques and strategies used on their level of motivation according to their level of digital competence under this approach.

RO2: To analyze their impressions of the learning achieved under a flipped methodology at the beginning and end of the core unit during the COVID-19 pandemic, and in particular:

To examine their impressions of the learning developed, as well as the variety of techniques and strategies used in the core unit according to the gender of the participants.

To analyze their impressions of the learning developed, as well as the variety of techniques and strategies used in the core unit according to their experience under this approach.

To analyze their perspectives on the learning developed, as well as the variety of techniques and strategies used in the core unit according to their level of digital competence under this approach.

A quasi-experimental design was adopted through pre-test and post-test questionnaires, which were prepared ad hoc to measure the extent to which the objectives set out in this research had been achieved.

A quantitative methodology was applied to examine university students’ perceptions of their learning process within this flipped model. Following the design of the pre-test and post-test, identical assessment measures were provided to participants before and after they had learned with this blended learning approach, to analyze comparative data, focusing on significant differences in learning perceptions at the end of the term.

Participants

The flipped experience was implemented in four groups in the core unit of Didactics of Social Sciences, which is compulsory for all second-year students of the Primary Education degree of the University of Murcia, Spain. In the study, the sample comprised 179 student teachers whose ages ranged from 19 to 39 years ( M = 20.02 and SD = 3.32). Most of the participants were women, (43 men (24.02%) and 136 women (75.98%), and only one of them had repeated the year (0.56%). Informed consent was obtained from all participants to conduct this study.

The main objective of the core unit was for students to acquire relevant knowledge and mastery of the skills required to be effective social science teachers, with emphasis on cultivating meaningful learning and using accessible resources to encourage reflection on their own learning process.

Correspondingly, students had to plan, carry out and evaluate innovative proposals for the teaching of social science contents together with a rationale for the approach selected and a detailed description of how to assess this content in Primary Education.

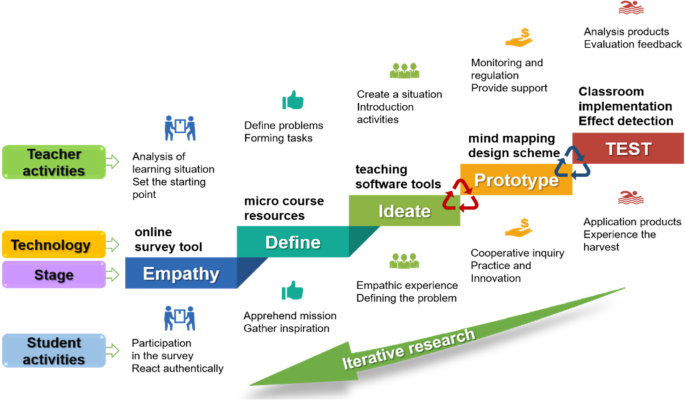

The strategies used in the flipped approach were based on the learning management system as an effective technology that can support learning and make it trackable and motivating.

The core unit was taught for four months in the first term of the 2020/2021 academic year (September-December) using a blended teaching model that combined classroom experiences and online course delivery in both synchronous and asynchronous classes sessions.

Synchronous class sessions were held on Fridays using the Zoom video conferencing platform, in which students were asked to watch videos, visit educational sites or search for information on current social science issues. Each week, students were provided with a Zoom link that they could use by logging in beforehand with their university credentials, thus ensuring the most secure access to online learning. The instantaneous sharing capability of this type of video conferencing allowed educators to work on course content through real-time presentations or to record and store them on the e-learning campus, so making them available to students throughout the term.

Asynchronous learning was promoted using innovative and interactive learning materials such as prerecorded video lectures or multimedia activities. The contents were regularly uploaded after finishing the preceding teaching units. Despite the flexibility of time frames, students had weekly deadlines to access the previously uploaded content and they had to log into their accounts on the learning platform and check what they were regularly assigned via hyperlinks.

In-class sessions were held on Wednesdays and encompassed a wide variety of practical tasks aimed at promoting numerous and various interactions in which students cooperated together and accomplished shared goals to demonstrate competence in simulated skills practice. Groups were divided into three subgroups to avoid risks and maximize students’ learning.

Subsequently, groups of university students were monitored until they finished the term, and information on their perceptions of the flipped experience was collected before and after applying this methodological proposal to gauge the impact of this program at the end of the period.

Data collection tools

Participants’ views on the adoption of this flipped approach were collected through an ad hoc questionnaire, the main purpose of which is to report on the implementation of a flipped approach by collecting data at two points in time from a sample of university students. Several advantages have been identified in the use of this technique in terms of reliability, objectivity, and representativeness (Cohen et al., 2017 ). Questionnaires are particularly valuable for data collection, as their quantifying nature and easy administration allow researchers to collect information from a large number of people. They are also considered quite reliable, as researchers do not need to be present when respondents fill it out, which means that if administered by different researchers, they should provide similar results. However, some limitations have been observed due to their impersonal nature, given the researcher’s detachment, or differences in interpretation that may distort respondents’ answers and undermine the validity of the information provided (Beiske, 2002 ; Waidi, 2016 ). The questionnaire was composed of thirty-six items divided into four main sections: self-perceived motivation, self-perceived acquisition of digital competencies, the effectiveness of this approach on students’ learning processes, and reported views on students’ learning of democratic education. The items were rated on a Likert scale of one to five points, where one is “very poor” and five is “excellent”, to value the degree of respondents’ agreement with the statements presented.

Procedure and data analysis

The data collected during the research were analyzed in Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) v.26.0. The degree of reliability and validity of the instrument was estimated prior to data analysis. The construct reliability was determined using Cronbach’s Alpha to estimate whether the instrument consisting of a multiple-question Likert scale was reliable. A Cronbach’s Alpha value equal to or higher than .70, which shows good internal consistency, is generally accepted in most social science research studies (González Alonso and Pazmiño Santacruz, 2015 ; Quansah, 2017 ). Regarding the questionnaire, positive results were obtained both overall ( α = 0.89) and in each of the sections: motivation, α = 0.86; learning processes, α = 0.83. The validity of the instrument was also tested using Bartlett’s test of sphericity and a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for each section of the questionnaire. In all the sections a significance level of 0.000 in Bartlett’s test of sphericity was achieved. After running the PCA, we obtained distribution in the first block of 2 dimensions, explaining 58,47% of the total variance, with a KMO of 0.906. In the second block, we obtained 2 dimensions, explaining 53.24%, with a KMO of 0.861.

As for the first objective, Table 1 shows descriptive statistics, consisting of two categories of measures: measures of central tendency (mean) and measures of variability (standard deviation).

In general, male students’ extrinsic motivation is higher than intrinsic motivation, while female students scored similarly on both types of self-perceived motivation. When contrasting the results between the pre-tests and post-tests, it is observed that male students scored higher in the post-tests with respect to their intrinsic self-perceived motivation, while female students scored lower in the post-tests for both types of self-perceived motivation. No significant differences were identified between pretests and posttests in this section.

As we can see in Table 2 , participants with previous experience with the FC model indicated higher self-perceived motivation than those with no experience. Also, student teachers with a high level of digital competence were more motivated to excel in class than those with a lower competence level. However, students with a lower level of digital competence showed more self-perceived intrinsic motivation to improve their future teaching practice than the other subgroups. Non-parametric tests were conducted to examine whether participants’ perceptions of their self-perceived motivation in relation to Flipped-Classroom-based learning differed statistically. Wilcoxon tests showed no significant differences between pre-tests and post-tests. However, Mann–Whitney U tests revealed significant differences between participants with prior experience in this approach and those without, with the former feeling more motivated than the latter to learn new active methodologies, link them to their future teaching practice, improve their autonomy or interact socially more effectively.

As shown in Table 3 , female students were more motivated by the resources and strategies implemented in the core unit compared to male students. Mann–Whitney U tests revealed significant differences between males and females in relation to small group activities, with female students rating this item significantly higher than the other subgroup.

Most of the items have a median between 3 and 4, which means that with these scores the participants indicated sufficient self-perceived motivation for this approach. The group with the lowest e-competence is the only group that gives a similar or higher score on all items in the post-test compared to the scores of the pre-test and the other groups (Table 4 ).

Regarding the second objective, the results in Table 5 show descriptive statistics, consisting of two categories of measures: measures of central tendency (mean) and measures of variability (standard deviation), as well as non-parametric results according to the gender of the participants.

With respect to the second objective, results indicate positive perceptions of their learning processes both before and after the implementation of this approach. However, male students scored lower in pre-tests but higher in posttests, particularly, with respect to learning interactions and self-evaluation. No significant differences were found between males and females in this objective.

As we can see in Table 6 , participants with no prior experience assigned a lower score to the items related to planning, managing, and assessing processes. In fact, non-parametric tests revealed significant differences in these items between respondents with and without experience with this approach. No significant differences were found between subgroups with different levels of e-competence.

The table below indicates men’s and women’s perceptions of the learning strategies and resources used (Table 7 ).

The results indicate that both men’s and women’s views on their learning are lower in the post-tests, although male students rated the quizzes, points, prizes, and the student portal more positively after the core unit. No significant differences were identified between the two subgroups.

In terms of their participation and involvement in the strategies presented to support their learning in the core unit, respondents rated practical classroom activities, small group work, quizzes, and rewards higher than the other options, with medians around 4 or higher. Significant differences were identified between the subgroups with and without prior experience, with the former rating videos, practical activities, quizzes, and small group tasks significantly higher than the latter. Similar differences were found between subgroups with different levels of e-proficiency, with students with higher e-proficiency scoring higher on the small group activities and computer tools.

Discussion and conclusions

This article examines student teachers’ self-perceived motivation and learning under the FC model during the pandemic in the academic year 20/21. The data obtained in this study showed a positive evaluation of the approach, both in reported motivation and perception of learning.

According to the results, participants felt sufficiently motivated both intrinsically and extrinsically, throughout the core unit, to learn new active methodologies and to improve their future teaching practice. Thus, this new and unexpected situation did not especially affect their interest in the FC model, and they were willing to participate and collaborate to do better in the future. As the comparative research shows (Latorre-Cosculluela et al., 2021 ), respondents were more willing to actively participate in the FC model than to be passive recipients of the information.

In addition, as other studies show (Aşıksoy and Özdamlı, 2016 ; Wanner and Palmer, 2015 ), the impressions expressed by respondents on the relevance of various strategies and techniques on their self-perceived motivation were quite good, with the Kahoot! quizzes being one of the best-valued resources. In this sense, it should be noted that the effectiveness of gamification and some related ludic elements such as points, levels, or prizes can provide fun and interaction, and thus increase motivation and promote student participation. Furthermore, as Fontana ( 2020 ) and Park and Kim ( 2021 ) point out, gamification can enhance social relationships through which students can share information, learn from each other and entertain themselves through these online platforms, which are even more significant during the pandemic period associated with social distancing and the need to protect oneself and others. Notwithstanding, as suggested by Mekler et al. ( 2017 ) the underlying motivational mechanisms should be the subject of further empirical research.

Regarding student teachers’ perceptions of their own learning, the data show their positive impressions, which are in line with other studies on the implementation of this approach (Foldness, 2016 ; Love et al., 2014 ). It seems obvious that participants were interested in understanding effective methodological shifts that support more flexible and active ways of learning under the current pandemic situation. According to the data, students’ attitudes towards flipped education, which has shifted from prioritizing traditional lecture-based lessons to more student-centered and autonomous learning methods, were receptive to this technology-based active learning approach. Students valued most positively the use of a wider range of online resources, the development of more frequent interactions, not only teacher-student but also peer-to-peer, and new ways of managing knowledge and content. Other research studies also agreed on the appropriateness of these alternative approaches during coronavirus disease because of their great deal of flexibility, their free access to online academic resources, and their interactive learning environments, among other reasons (Chick et al., 2020 ; Lapitan et al., 2021 ). In this sense, the use of a full set of IT tools, such as a modern LMS with a user-friendly interface and effective collaboration tools, would allow for flexible resource management, which favors the search, sharing, and application of knowledge among students (Basilaia and Kvavadze, 2020 ; Zainuddin and Perera, 2018 ).

It is worth highlighting the statistically significant differences identified in the dimensions of the study, especially regarding previous experience and e-competence. In the first case, students with prior experience valued the effects of this approach in improving their future teaching practice more highly than the rest of their peers, which means that they saw this innovation as an opportunity to explore, expand their knowledge and update their potential as future teachers significantly more than those without prior experience. Therefore, these results encourage the further implementation of these actions, task-based initiatives in higher education, so that students can gain more experience of what an FC model consists of and thus improve their motivation and learn to manage cognitive knowledge more effectively (Abeysekera and Dawson, 2015 ).

Regarding the e-competence variable, results from non-parametric tests showed that students with a higher level of e-competence perceived active in-class tasks as more intrinsically motivating than the rest of their peers, while students with a lower e-competence found that taking an FC approach constituted a more motivating means of improving their future teaching practice. These different perceptions may give learners a more immediate sense of progress if they are sufficiently e-competent within this model or in the future once they intensify their acquisition of digital skills. In any case, the FC model has proved that it enables students to easily understand their progression in the learning and development of innovative methodological proposals (Blau and Shamir-Inbal, 2017 ).

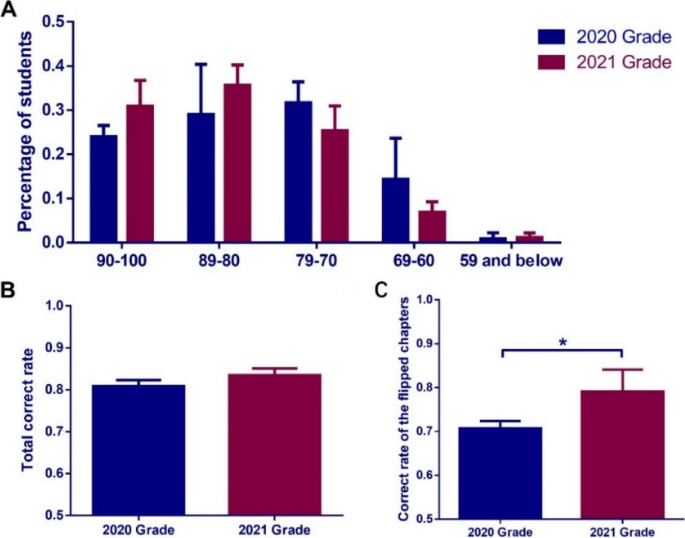

However, despite the students’ positive opinions, their impressions are not as optimistic as in other similar pre-pandemic studies conducted in the same context. The results in research conducted a year earlier (Gómez-Carrasco et al., 2020 ), in which students expressed more significant positive views on their self-perceived motivation, one point higher on average, may demonstrate that the consequences of pandemic-related restrictions are causing some unease among university students.

Furthermore, the findings of this research cannot be representative of current teaching and learning processes that drive student motivation, as the results are drawn from a single experience and it would be advisable for the analysis to be compared with actual learning outcomes and in more core units to gain a more complete understanding of the current outcomes and impacts of this model.

Therefore, there is a need for further study of these newly emerging e-learning scenarios due to the restrictions or lockdowns, as well as the complex set of interrelated factors affecting their implementation. In addition, further research is required to analyze the lower value items within this approach to customize them according to learners’ specific interests and needs.

Data availability

The datasets generated during this study are not publicly available because the identities of some participants are visible, undermining privacy protection, but they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abeysekera L, Dawson P (2015) Motivation and cognitive load in the flipped classroom: definition, rationale and a call for research. High Educ Res Dev 34(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2014.934336

Article Google Scholar

Agarwal S, Kaushik JS (2020) Student’s perception of online learning during COVID pandemic. Indian J Pediatr 87:554–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-020-03327-7

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Agung ASN, Surtikanti MW, Quinones CA (2020) Students’ perception of online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: a case study on the english students of STKIP Pamane Talino. SOSHUM 10(2):225–235. https://doi.org/10.31940/soshum.v10i2.1316

Ardan M, Rahman FF, Geroda GB (2020) The influence of physical distance to student anxiety on COVID-19, Indonesia. J Crit Rev 7(17):1126–1132

Google Scholar

Aşıksoy G, Özdamlı F (2016) Flipped classroom adapted to the ARCS model of motivation and applied to a physics course. Eurasia J Math Sci 12(6):1589–1603. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2016.1251a

Basilaia G, Kvavadze D (2020) Transition to online education in schools during a SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Georgia. Ped Res 5(4):1–9. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/7937

Beiske B (2002) Research methods: uses and limitations of questionnaires, interviews, and case studies. School of Management Generic Research Methods, Manchester

Bergmann J, Sams A (2012) Flip your classroom: reach every student in every class every day. International Society for Technology in Education, New York

Blau I, Shamir-Inbal T (2017) Re-designed flipped learning model in an academic course: the role of co-creation and co-regulation. Comput Educ 115:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.07.014

Cevikbas M, Kaiser G (2020) Flipped classroom as a reform-oriented approach to teaching mathematics. Zdm 52(7):1291–1305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-020-01191-5

Clark-Wilson A, Robutti O, Thomas M (2020) Teaching with digital technology. Zdm 52(7):1223–1242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-020-01196-0

Chick RC, Clifton GT, Peace KM, Propper BW, Hale DF, Alseidi AA, Vreeland TJ (2020) Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the Covid-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ 3:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018

Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K (2017) Research methods in education. Routledge, New York

Book Google Scholar

Collado-Valero J, Rodríguez-Infante G, Romero-González M, Gamboa-Ternero S, Navarro-Soria I, Lavigne-Cerván R (2021) Flipped classroom: active methodology for sustainable learning in higher education during social distancing due to COVID-19. Sustain 13(10):5336. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105336

Colomo-Magaña E, Soto-Varela R, Ruiz-Palmero J, Gómez-García M (2020) Percepción de estudiantes universitarios sobre la utilidad de la metodología del aula invertida. Educ Sci 10:275. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10100275

Dhawan S (2020) Online learning: a panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J Educ Technol Syst 49(1):5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239520934018

ElSaheli-Elhage R (2021) Access to students and parents and levels of preparedness of educators during the COVID-19 emergency transition to e-learning. Int J Stud Educ 3(2):61–69. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijonse.35

Fatani TH (2020) Student satisfaction with videoconferencing teaching quality during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med Educ 20(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02310-2

Foldnes N (2016) The flipped classroom and cooperative learning: evidence from a randomised experiment. Act Learn High Educ 17(1):39–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787415616726

Fontana MT (2020) Gamification of ChemDraw during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Investigating How a Serious, Educational-Game Tournament (Molecule Madness) impacts student wellness and organic chemistry skills while distance learning. J Chem Educ 97(9):3358–3368. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00722

Article CAS Google Scholar

Goksu DY, Duran V (2020) Flipped Clasroom Model in the Context of Distant Training. Res High Educ Sci 104–127. https://www.isres.org/books/chapters/Rhes2020-104-127_29-12-2020.pdf . Accessed 20 Feb 2021

Gómez-Carrasco CJ, Monteagudo-Fernández J, Moreno-Vera JR, Sainz-Gómez M (2020) Evaluation of a gamification and flipped-classroom program used in teacher training: Perception of learning and outcome. PLoS ONE 15(7):e0236083. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236083

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

González Alonso J, Pazmiño Santacruz M (2015) Cálculo e interpretación del Alfa de Cronbach para el caso de validación de la consistencia interna de un cuestionario, con dos posibles escalas tipo Likert. Rev Publ 2(1):62–67

Guraya S (2020) Combating the COVID-19 outbreak with a technology-driven e-flipped classroom model of educational transformation. J Taibah Univ Med Sci 15(4):253–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2020.07.006

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Islam MA, Barna SD, Raihan H, Khan MNA, Hossain MT (2020) Depression and anxiety among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: a web-based cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE 15(8):e0238162. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238162

Lapitan LD, Tiangco CE, Sumalinog DAG, Sabarillo NS, Diaz JM (2021) An effective blended online teaching and learning strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ Chem Eng 35:116–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ece.2021.01.012

Latorre-Cosculluela C, Suárez C, Quiroga S, Sobradiel-Sierra N, Lozano-Blasco R, Rodríguez-Martínez A (2021) Flipped Classroom model before and during COVID-19: Using technology to develop 21st century skills. ITSE. ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITSE-08-2020-0137

López D, García C, Bellot J, Formigós J, Maneau V (2016) Elaboración de material para la realización de experiencias de clase inversa (flipped classroom). In:Álvarez J, Grau S, Tortosa M (eds) Innovaciones metodológicas en docencia universitaria: resultados de investigación. Alicante, Spain, pp. 973–984

Love B, Hodge A, Grandgenett N, Swift AW (2014) Student learning and perceptions in a flipped linear algebra course. Int J Math Educ Sci Technol 45(3):317–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2013.822582

Mekler ED, Brühlmann F, Tuch AN, Opwis K (2017) Towards understanding the effects of individual gamification elements on intrinsic motivation and performance. Comput Hum Behav 71:525–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.048

Monzonís NC, Méndez VG, Ariza AC, Magaña EC (2020) Aula invertida en tiempos de COVID-19: una perspectiva transversal. IJERI 15:326–341. https://doi.org/10.46661/ijeri.5439

Naw N (2020) Designing a flipped classroom for Myanmar universities during COVID-19 crisis. Univ J ICT Multidiscip Iss Arts Sci Engineer Econ Educ 1:1–8

Park S, Kim S (2021) Is sustainable online learning possible with gamification?—The effect of gamified online learning on student learning. Sustain 13(8):4267

Quansah F (2017) The Use of cronbach alpha reliability estimate in research among students in public Universities In Ghana. Afr J Teach Educ 6(1):56–64. https://doi.org/10.21083/ajote.v6i1.3970

Smith E, Boscak A (2021) A virtual emergency: learning lessons from remote medical student education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg Radiol 28(3):445–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-020-01874-2

Tang T, Abuhmaid AM, Olaimat M, Oudat DM, Aldhaeebi M, Bamanger E (2020) Efficiency of flipped classroom with online-based teaching under COVID-19. Interact Learn Environ 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1817761

Villa FG, Litago JDU, Sánchez-Fdez A (2020) Perceptions and expectations in the university students from adaptation to the virtual teaching triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev Lat Comun Soc 78:99–119

Waidi AA (2016) Employment of questionnaire as tool for effective business research outcome: problems and challenges. Glob Econ Observer 4(1):136

Wanner T, Palmer E (2015) Personalising learning: exploring student and teacher perceptions about flexible learning and assessment in a flipped university course. Comput Educ 88:354–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.07.008

World Health Organization (2020) Critical preparedness, readiness and response actions for COVID-19. In: World Health Organization. Publications. Overview. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/critical-preparedness-readiness-and-response-actions-for-covid-19 . Accessed 5 Feb 2021

Wright GB (2011) Student-centered learning in higher education. Int J Teach Learn Higher Educ 23(1):92–97

Zainuddin Z, Perera CJ (2018) Supporting students’ self-directed learning in the flipped classroom through the LMS TES Blend Space. Horiz 26(4):281–290

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the “Spanish Ministry for Science, Innovation, and Universities. Secretary of State for Universities, Research, Development and Innovation”, grant number PGC2018-094491-B-C33, and “Seneca Foundation. Regional Agency for Science and Technology”, grant number 20874/PI/18. We would like to thank Stephen Hasler for his proofreading work. It was a pleasure to work with him.

Author information

These authors contributed equally: José María Campillo-Ferrer, Pedro Miralles-Martínez.

Authors and Affiliations

Faculty of Education, University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain

José María Campillo-Ferrer & Pedro Miralles-Martínez

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to José María Campillo-Ferrer .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Campillo-Ferrer, J.M., Miralles-Martínez, P. Effectiveness of the flipped classroom model on students’ self-reported motivation and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8 , 176 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00860-4

Download citation

Received : 10 April 2021

Accepted : 05 July 2021

Published : 20 July 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00860-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Distance learning: studying the efficiency of implementing flipped classroom technology in the educational system.

- Khaleel Al-Said

- Irina Krapotkina

- Nadezhda Maslennikova

Education and Information Technologies (2023)

Flipped Learning 4.0. An extended flipped classroom model with Education 4.0 and organisational learning processes

- María Luisa Sein-Echaluce

- Ángel Fidalgo-Blanco

- Francisco José García-Peñalvo

Universal Access in the Information Society (2022)

Medical student education through flipped learning and virtual rotations in radiation oncology during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross sectional research

- Tae Hyung Kim

- Jin Sung Kim

- Jee Suk Chang

Radiation Oncology (2021)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 24 August 2016

The flipped classroom: for active, effective and increased learning – especially for low achievers

- Jalal Nouri 1

International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education volume 13 , Article number: 33 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

110k Accesses

154 Citations

43 Altmetric

Metrics details

Higher education has been pressured to shift towards more flexible, effective, active, and student-centered teaching strategies that mitigate the limitations of traditional transmittal models of education. Lately, the flipped classroom model has been suggested to support this transition. However, research on the use of flipped classroom in higher education is in its infancy and little is known about student’s perceptions of learning through flipped classroom. This study examined students’ perceptions of flipped classroom education in a last year university course in research methods. A questionnaire was administered measuring students’ ( n = 240) perceptions of flipped classroom in general, video as a learning tool, and Moodle (Learning Management System) as a supporting tool within the frame of a flipped classroom model. The results revealed that a large majority of the students had a positive attitude towards flipped classroom, the use of video and Moodle, and that a positive attitude towards flipped classroom was strongly correlated to perceptions of increased motivation, engagement, increased learning, and effective learning. Low achievers significantly reported more positively as compared to high achievers with regards to attitudes towards the use of video as a learning tool, perceived increased learning, and perceived more effective learning.

Introduction

Teaching at the university level has been performed in a relatively similar manner during a long historical time and across cultures. As a central pillar, we find the traditional lecture with the professor, or the “sage on the stage” as put by King ( 1993 ), transmitting knowledge to receiving students. Nevertheless, over the past 30 years, university education and traditional lectures in particular have been strongly criticized. The main criticism has cast light on the following: students are passive in traditional lectures due to the lack of mechanisms that ensure intellectual engagement with the material, student’s attention wanes quickly, the pace of the lectures is not adapted to all learners needs and traditional lectures are not suited for teaching higher order skills such such as application and analysis (Cashin, 1985 ; Bonwell, 1996 ; Huxham, 2005 ; Young, Robinson, & Alberts, 2009 ). Consequently, various researchers and educators have advocated forms of lecturing based on an active learning philosophy, some involving novel technology mediated interactions (Beekes, 2006 ; Rosie, 2000 ), others without an explicit focus on technology such as the enhanced lecture of Bonwell ( 1996 ). However, despite the comprehensive critique, the traditional lecture continues to prevail as the predominant didactic strategy in higher education (Roehl, Reddy, & Shannon, 2013 ).

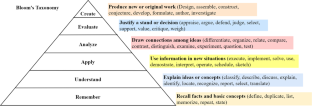

It is against such a background, and to high extent because of advancements in educational technology, increasing pressures on higher education have been witnessed that have spawned a push to flexible blended student-centered learning strategies that mitigate the limitations of the transmittal model of education (Betihavas, Bridgman, Kornhaber, & Cross, 2015 ). Accompanied with the shift to provide student-centered learning we have seen a surge of researchers and educators advocating flipped classroom curricula in higher education. The advocacy of the flipped classroom model is justifiable. Judging by its underlying theory and the conducted empirical studies, the flipped classroom model appears to address several challenges with traditional ways of lecturing and pave way for active learning strategies and for using classroom time for engaging in higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy (Krathwohl, 2002 ) such as application, analysis, and synthesis.

The flipped classroom model is based on the idea that traditional teaching is inverted in the sense that what is normally done in class is flipped or switched with that which is normally done by the students out of class. Thus, instead of students listening to a lecture in class and then going home to work on a set of assigned problems, they read course literature and assimilate lecture material through video at home and engage in teacher-guided problem-solving, analysis and discussions in class. Proponents of flipped classroom list numerous advantages of inverting teaching and learning in higher education according to the flipped classroom model: it allows students to learn in their own pace, it encourages students to actively engage with lecture material, it frees up actual class time for more effective, creative and active learning activities, teachers receive expanded opportunities to interact with and to assess students’ learning, and students take control and responsibility for their learning (Gilboy, Heinerichs, & Pazzaglia, 2015 ; Betihavas et al., 2015 ).

Despite that flipped classroom is a rather new phenomenon in higher education, some empirical research has been conducted. For instance, McLaughlin et al. ( 2013 ) and McLaughlin et al. ( 2014 ) analysis of pharmacy students’ experiences of flipped classroom courses revealed that students prefer learning content prior to class and using class time for applied learning, and that students who learned through a flipped classroom approach considered themselves more engaged than students attending traditional courses. Similar findings were obtained by Davies, Dean, and Ball ( 2013 ) who compared three different instructional strategies in an information systems spreadsheet course, and showed that students attending the flipped classroom course also were more satisfied with the learning environment compared to the other treatment groups. Several studies report that students enjoy being able to learn in their own pace and that they prefer flipped classroom over traditional approaches (Butt, 2014 ; Davies et al., 2013 ; Larson & Yamamoto, 2013 ; McLaughlin et al., 2014 ; Roach, 2014 ; Gilboy et al., 2015 ). In term of examinations of learning outcomes, Love, Hodge, Grandgenett, and Swift ( 2014 ) demonstrated higher exam grades for students using a flipped classroom approach as compared to students learning through traditional methods. Hung ( 2015 ) showed similar results for English language learners. Another study by Findlay-Thompson and Mombourquette ( 2014 ) comparing traditional teaching methods and the flipped classroom approach within the same business course showed no significant differences in academic outcomes.

However, empirical research on the flipped classroom model in higher education, and more detailed investigations of students’ perceptions of its use, is in its infancy and the need for further research is underlined by many (Bishop & Verleger, 2013 ; Uzunboylu & Karagozlu, 2015 ; Betihavas et al., 2015 ; Gilboy et al., 2015 ).

Research purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine how students perceive flipped classroom education in a university research methods course. Three particular aspects were considered, namely, (a) the student’s general experiences and attitudes of learning through flipped classroom, (b) the student’s experiences of using video lectures as a medium for learning, and (c) the student’s experiences of using a Learning Management System (LMS) in the frame of the flipped classroom model. Further, this study has also considered differences in experiences and attitudes of low and high achieving students.

This study is based on a quantitative analysis of a closed questionnaire addressing undergraduate students’ perceptions and experience of learning through flipped classroom in a course preparing students for the bachelor thesis with respect to scientific methodology and communication. The course was implemented during autumn 2015.

Participants

The participants were undergraduate students ( n = 240) at Stockholm University in Sweden taking the last year course Research methods and communication during autumn semester 2015. All of the students were enrolled in 8 different bachelor level programs at the department of Computer and Systems Sciences. The students, 76 females and 164 males, ranged in age from 20 to 43 years, with a mean age of 25.12 years (SD = 4.09). Out of the 240 students only 23 had a previous experience of flipped classroom. The number of students passing the course was 218. Table 1 presents an overview of student demographics and background questions. Low and high achievers among the students were determined by the student’s average grade during their studies. Here high achievers were defined as having average grades A to B while low achievers were defined as having average grades C to F.

Materials and procedure

Course structure.

The course focused on in this study prepares students for the bachelor thesis with respect to scientific methodology and communication. The learning objectives are on the one hand to facilitate students understanding of the fundamentals of research strategies, data-collection methods, and analysis methods, and on the other hand to familiarize students with application of qualitative and quantitative methods of analysis. Put differently, the course aimed at equipping students with conceptual knowledge (an understanding of scientific methods), and procedural knowledge (application of analysis methods and scientific writing). See Fig. 1 for the underlying pedagogical structure.

Pedagogical structure for students conceptual and procedural learning

The course was divided into three parts with three different examination tasks. The first part concerned gaining a theoretical understanding of the fundamentals of research strategies, data-collection methods, and analysis methods. The pedagogical structure for this part comprised of independent reading of course literature. Students reading of the course literature was supported by three longer video lectures (in average 60 min each), one traditional campus lecture (teacher presenting and summarizing the fundamentals of research strategies), and one interactive flipped classroom lecture in which the teacher presented examples of exam questions that students answered in real-time by using a digital response system (Socrative) via their own smart phones, tablets and computers. The response system provided an overview of the responses that allowed students to assess their knowledge and the teacher to provide formative feedback and elaborated explanations when needed. In addition, digital supervision was offered through a learning management system (Moodle). The examination for this part comprised of a multiple-choice digital exam in the learning management system.

The second part was a practical qualitative analysis project that students conducted in groups of two. The task of this project was to use a qualitative analysis method to analyze qualitative interview data and communicate the results in a report following scientific standards of qualitative data presentation. During this project the students were supported by five digital lectures (in average 35 min each), three flipped lectures on campus, and digital supervision through the learning management system. In the three flipped lectures on campus students worked with their projects and were scaffolded by several teachers that answered questions and provided feedback. When the teachers identified common misunderstandings or needs among the students, they provided elaborated explanations to the whole class. The examination of the second part comprised of a written group report.

The third part of the course was similar to the second part, comprising of a project with a focus on using quantitative methods to analyze a questionnaire and communicate the results according to scientific standards of quantitative result presentation. During this project the students were supported by seven video lectures (in average 30 min each), three flipped lectures in class with teachers scaffolding practical work, and digital supervision in the learning management system. The videos covered the theoretical fundamentals of descriptive and inferential statistics as well as how different statistical tests can be performed and interpreted in SPSS. The examination of the third part comprised of a written group report.

All video lectures made available to the students during the course were produced by teachers and researchers in a professional video studio at Stockholm University. The video lectures were specifically tailored for the course.

Survey measures and procedure

A questionnaire was developed consisting of 4 sections with 58 items to measure students’ perceptions of flipped classroom in general, video as a learning tool, and Moodle as a supporting system.

Section 1 (General information) consisted of 12 demographic and background items

Section 2 (Flipped Classroom Scale) consisted of 21 items measuring students’ experiences and attitudes of learning through flipped classroom

Section 3 (Video Scale) consisted of 16 items measuring students’ experiences of using video lectures as a medium for learning.

Section 4 (LMS scale) consisted of 9 items measuring students’ perceptions of the utility of Moodle in supporting their learning processes within the frame of flipped classroom pedagogy.

An exploratory factor analysis with principal component extraction was performed in an attempt to refine the instrument. After factor analysis, 8 items that did not load on any factors or highly cross-loaded on multiple factors were removed. Accordingly, the instrument used for the final analysis consisted of 17 items for the Flipped Classroom Scale, 13 items for the Video Scale, and 5 items for the LMS Scale. Overall, Cronbach’s alphas were .78 for the Flipped Classroom Scale, .82 for the Video Scale, and .84 for the LMS Scale. Students were asked to complete the questionnaire at the end of the course. The questionnaire was developed and administered through a web tool.

Students’ general perceptions of flipped classroom

The flipped classroom model proved to be appreciated by many students. Among the 240 respondents, 180 students expressed a positive attitude to flipped classroom after the course (75 %). The students most appreciated the use of video (M = 4.15, SD = 1.10), flexibility and mobility given by the flipped classroom model (M = 3.95, SD = 1.10), that learning can be done at own pace (M = 3.75, SD = 0.91), that learning processes are better supported (M = 3.54, SD = 1.13), and that non-traditional campus activities are meaningful (M = 3.40, SD = 1.13).

In terms of other characteristics of the learning process, to some extent the students appeared to agree that it is easier and more effective to learn with the flipped classroom approach (M = 3.17, SD = 1.03) and that they feel more motivated as learners (M = 2.95, SD = 1.13). Furthermore, many students perceived that they had to take more responsibility for their learning (M = 3.91, SD = 0.96) in a flipped classroom course.

Noteworthy, some students also felt themselves alone during their learning (M = 3.01, SD = 1.29). Table 2 shows the students’ experiences of flipped classroom after the course was completed.

The results of an analysis of the correlations between the measured variables, with a particular focus on attitudes towards flipped classroom and its effect on learning and motivation is presented in Table 3 . Students with positive attitudes towards flipped classroom more likely had positive attitudes towards video ( p < 0.01), experienced increased motivation ( p < 0.01), more effective learning ( p < 0.01), and increased learning ( p < 0.01). They also tended to agree that flipped classroom made them more active as learners ( p < 0.01) and take more responsibility for their learning ( p < 0.01).

The use of video as a learning tool

Using flipped classroom and in particular video as a tool for assimilating knowledge otherwise presented in traditional lectures proved to correlate strongly with perceived increased motivation, increased learning and effective learning. When analyzing the student’s experiences of using video as a learning tool in more detail a number of reasons for appreciating video stand out (see Table 4 for an overview). The students strongly agreed that it was useful for their learning to be able to pause (M = 4.52, SD = 0.85), rewind (M = 4.48, SD = 0.87) and fast-forward video (M = 4.04, SD = 1.36). They also agreed that the combination of video and non-traditional lectures was useful (M = 3.73, SD = 1.16) as well as being able to watch lectures in a mobile way (MD = 3.98, SD = 1.28).

The use of Moodle within the frame of flipped classroom

A learning management system (Moodle) was used during the course to support students’ learning processes within the frame of a flipped classroom model. As presented in Table 5 , the students appreciated this support (M = 4.22, SD = 0.86). In particular, they found it useful to be able to see other students’ questions posed in Moodle and the teachers answers to those questions (M = 4.39, SD = 0.94), and for general communication with teachers (M = 4.07, SD = 1.05). Interestingly, the LMS itself contributed to some student’s motivation to learn (M = 3.40, SD = 1.26).

Comparing low and high achievers

When comparing low and high achievers among the students in terms of attitudes towards flipped classroom, video and the effect on learning and motivation some interesting findings were obtained. The results of conducted independent sample t-tests showed no significant differences in positive attitudes to flipped classroom of low achievers (M = 3.37, SD = 0.74) and high achievers (M = 3.20, SD = 0.87), t(238) = 2.13, p > 0.05. Significant differences were however revealed with regards to attitudes towards the use of video of low achievers (M = 3.10, SD = 0.72) and high achievers (M = 2.67, SD = 1.02), t(238) = 3.17, p < 0.05.

Interestingly, the perception of increased learning also significantly differed between low achievers (M = 3.13, SD = 0.93) and high achievers (M = 2.71, SD = 1.23), t(238) = 2.40, p < 0.05. The tests likewise showed significant differences in perceived more effective learning of low achievers (M = 3.25, SD = 0.95) and high achievers (M = 2.80, SD = 1.32), t(238) = 2.46, p < 0.05. However, no significant differences could be identified between low achievers and high achievers in the other variables measured (see Table 6 ).

Conclusions

The calls for reforming traditional higher education teaching, and for transforming the sage on the stage into the guide on the side in order to pave way for student-centered active learning strategies have probably never been as loud as now. In this context, flipped classroom has been proposed to answer these calls. Several studies have demonstrated that flipped classroom as a teaching method may promote student engagement and a more active approach to learning in higher education. The findings from this study confirm the results of these studies and highlights additional advantages associated with the flipped classroom model.

The students in the study’s sample were found to generally appreciate the flipped classroom. The most commonly valued reasons for this was that the students appreciated learning through using video material, the opportunity to study in their own pace, flexibility and mobility brought about by accessible video lectures, and that learning is easier and more effective within the frame of the flipped classroom.

A correlation analysis further demonstrated significant strong correlations between students’ appreciation of the flipped classroom experience on the one hand, and attitudes towards video as a learning tool, increased motivation, increased learning, more effective learning and more active learning on the other hand.

Interestingly, independent sample t-tests showed significant differences between low and high achievers in that the low achievers tended to have more positive attitudes towards the use of video as a learning tool. Low achievers also to higher extent perceived increased and more effective learning through flipped classroom. A more detailed analysis of the students’ experiences of using video showed that the most valued aspects of video use was being able to pause and rewind the video lectures. Against this fact, it is not unreasonable to conclude that low achievers, who might find traditional lectures challenging and fast-paced (Young et al., 2009 ), experienced an empowerment using the flipped classroom model in terms of gaining more opportunities to reflect and learn in their own pace.

For all students in general, the results indicate that the reasons for students’ perceptions of increased and more effective learning are associated with: 1) the affordances of video lectures (the ability to reflect and learn in own pace); 2) more meaningful practice-oriented and teacher supervised classroom activities; and 3) more supported learning processes due to teacher and peer scaffolding in class and out of class through the use of Moodle.

Thus, as final remarks, considering the ineffectiveness of traditional lectures in retaining students’ attention and promoting active learning (Windschitl, 1999 ; Young et al., 2009 ) in higher education, the results of this study indicate that the flipped classroom model seem to offer promising ways to engage students in more effective, supportive, motivating and active learning, especially for low achievers and students that may struggle with traditional lectures. However, the results should be viewed in light of the limitations of this study. One such limitation is the non existence of a control group which limits the external validity of the results. Another limitation is connected to the fact that the majority of the student’s surveyed have not experienced flipped classroom before, thus the results may partly reflect the influence of a new approach of learning and teaching and not necessary the influence of the flipped classroom approach. It also should be noted that all results related to improved learning and effectiveness of learning is based on students self-declared perceptions and not on independent measures. Future studies on the effects of flipped classroom should address these limitations and in particular explore the extent to which the actual performance of students is or is not affected by the flipped classroom approach moving beyond just student perceptions.

Beekes, W. (2006). The “millionaire” method for encouraging participation. Active Learning in Higher Education, 7 (1), 25–36.

Article Google Scholar

Betihavas, V., Bridgman, H., Kornhaber, R., & Cross, M. (2015). The evidence for ‘flipping out’: A systematic review of the flipped classroom in nursing education. Nurse Education Today, 6 , 15–21.

Bishop, J. L., & Verleger, M. A. (2013). The flipped classroom: a survey of the research. In ASEE National Conference Proceedings, Atlanta, GA .

Google Scholar

Bonwell, C. C. (1996). Enhancing the lecture: revitalizing a traditional format. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 1996 (67), 31–44.

Butt, A. (2014). Student views on the use of a flipped classroom approach: evidence from Australia. Business Education & Accreditation, 6 (1), 33–43.

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Cashin, W. E. (1985). Improving lectures. Idea paper no. 14 . Manhattan: Kansas State University, Center for Faculty Evaluation and Development.

Davies, R. S., Dean, D. L., & Ball, N. (2013). Flipping the classroom and instructional technology integration in a college-level information systems spreadsheet course. Educational Technology Research and Development, 61 (4), 563–580.

Findlay-Thompson, S., & Mombourquette, P. (2014). Evaluation of a flipped classroom in an undergraduate business course. Business Education & Accreditation, 6 (1), 63–71.

Gilboy, M. B., Heinerichs, S., & Pazzaglia, G. (2015). Enhancing student engagement using the flipped classroom. Journal of nutrition education and behavior, 47 (1), 109–114.

Hung, H. (2015). Flipping the classroom for English language learners to foster active learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28 (1), 81–96.

Huxham, M. (2005). Learning in lectures Do ‘interactive windows’ help? Active learning in higher education, 6 (1), 17–31.

King, A. (1993). From sage on the stage to guide on the side. College teaching, 41 (1), 30–35.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom's taxonomy: an overview. Theory into practice, 41 (4), 212–218.

Larson, S., & Yamamoto, J. (2013). Flipping the college spreadsheet skills classroom: initial empirical results. Journal of Emerging Trends in Computing and Information Sciences, 4 (10), 751–758.

Love, B., Hodge, A., Grandgenett, N., & Swift, A. (2014). Student learning and perceptions in a flipped linear algebra course. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 45 (3), 317–324.

McLaughlin, J. E., Griffin, L. M., Esserman, D. A., Davidson, C. A., Glatt, D. M., Roth, M. T., …Mumper, R. J. (2013). Pharmacy student engagement, performance, and perception in a flipped satellite classroom. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education , 77 (9), 196.

McLaughlin, J. E., Roth, M. T., Glatt, D. M., Gharkholonarehe, N., Davidson, C. A., Griffin, L. M., …Mumper, R. J. (2014). The flipped classroom: a course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health professions school. Academic Medicine , 89 (2), 236–243.

Roach, T. (2014). Student perceptions toward flipped learning: new methods to increase interaction and active learning in economics. International Review of Economics Education, 17 , 74–84.

Roehl, A., Reddy, S. L., & Shannon, G. J. (2013). The flipped classroom: an opportunity to engage millennial students through active learning strategies. Journal of Family & Consumer Sciences, 105 (2), 44–49.

Rosie, A. (2000). “Deep learning”: a dialectical approach drawing on tutor-led web resources. Active Learning in Higher Education, 1 (1), 45–59.

Uzunboylu, H., & Karagozlu, D. (2015). Flipped classroom: a review of recent literature. World Journal on Educational Technology, 7 (2), 142–147.

Windschitl, M. (1999). Using small-group discussions in science lectures. College Teaching, 47 (1), 23–7.

Young, M. S., Robinson, S., & Alberts, P. (2009). Students pay attention! Combating the vigilance decrement to improve learning during lectures. Active Learning in Higher Education, 10 (1), 41–55.

Download references

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Computer and Systems sciences, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

Jalal Nouri

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jalal Nouri .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nouri, J. The flipped classroom: for active, effective and increased learning – especially for low achievers. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 13 , 33 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-016-0032-z

Download citation

Received : 27 February 2016

Accepted : 14 July 2016

Published : 24 August 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-016-0032-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Teaching/learning strategies

- Distributed learning environments

- Improving classroom teaching

- Interactive learning environments

- Post- secondary education

Flipped learning: What is it, and when is it effective?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, patricia roehling and patricia roehling professor emeritus of psychology - hope college @proehling carrie bredow carrie bredow associate professor of psychology - hope college @drb_hopeful.

September 28, 2021

Instructors are constantly on the lookout for more effective and innovative ways to teach. Over the last 18 months, this quest has become even more salient, as COVID-19 has shaken up the academic landscape and pushed teachers to experiment with new strategies for engaging their students. One innovative teaching method that may be particularly amenable to teaching during the pandemic is flipped learning. But does it work?

In this post, we discuss our new report summarizing the lessons from over 300 published studies on flipped learning. The findings suggest that, for many of us who work with students, flipped learning might be worth a try.

What is flipped learning?

Flipped learning is an increasingly popular pedagogy in secondary and higher education. Students in the flipped classroom view digitized or online lectures as pre-class homework, then spend in-class time engaged in active learning experiences such as discussions, peer teaching, presentations, projects, problem solving, computations, and group activities. In other words, this strategy “flips” the typical presentation of content, where class time is used for lectures and example problems, and homework consists of problem sets or group project work. (See Roehling, 2018 , for information on how to construct and implement flipped learning.)

Flipped learning is not simply a fad. There is theoretical support that it should promote student learning. According to constructivist theory, active learning enables students to create their own knowledge by building upon pre-existing cognitive frameworks, resulting in a deeper level of learning than occurs in more passive learning settings. Another theoretical advantage of flipped learning is that it allows students to incorporate foundational information into their long-term memory prior to class. This lightens the cognitive load during class, so that students can form new and deeper connections and develop more complex ideas. Finally, classroom activities in the flipped model can be intentionally designed to teach students valuable intra- and interpersonal skills.

Since 2012, the research literature on the effectiveness of flipped learning has grown exponentially. However, because these studies were conducted in many different contexts and published across a wide range of disciplines, a clear picture of whether and when flipped classrooms outperform their traditional lecture-based counterparts has been difficult to assemble.

To address this issue, we conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis of flipped pedagogies ; this review focused specifically on higher education contexts. For our meta-analysis, we combined data from 317 studies (51,437 participants) that compared the effectiveness of flipped and lecture-based courses taught by the same instructor.

We assembled all of these studies to examine the efficacy of flipped versus lecture-based learning for fostering a variety of outcomes in higher education. Specifically, we examined outcomes falling into three broad categories:

- Academics , including exams and assignments measuring foundational knowledge, higher-order thinking, and applied/professional skills;

- Intra-/interpersonal aptitudes , including student engagement and identification with the course or discipline, metacognitive skills, and interpersonal skills; and

- Satisfaction with the course and instruction as reported by students.

We also explored the extent to which factors related to educational context (e.g., discipline, geographic location) and course design (e.g., the use of quizzes to motivate pre-class preparation) may shape the effectiveness of flipped learning. Below, we outline some of the key takeaways of our meta-analytic synthesis.

Is flipped learning more effective than lecture-based learning?

Yes, it certainly can be. Students in flipped classrooms performed better than those in traditionally taught classes across all of the academic outcomes we examined. In addition to confirming that flipped learning has a positive impact on foundational knowledge (the most common outcome in prior reviews of the research), we found that flipped pedagogies had a modest positive effect on higher-order thinking. Flipped learning was particularly effective at helping students learn professional and academic skills.

Importantly, we also found that flipped learning is superior to lecture-based learning for fostering all intra-/interpersonal outcomes examined, including enhancing students’ interpersonal skills, improving their engagement with the content, and developing their metacognitive abilities like time management and learning strategies.

In which educational settings is flipped learning most effective?

Flipped learning was shown to be more effective than lecture-based learning across most disciplines. However, we found that flipped pedagogies produced the greatest academic and intra-/interpersonal benefits in language, technology, and health-science courses. Flipped learning may be a particularly good fit for these skills-based courses, because class time can be spent practicing and mastering these skills. Mathematics and engineering courses, on the other hand, demonstrated the smallest gains when implementing flipped pedagogies.