The Writing Process

The Writing Process Explained

Understanding the writing process provides a student with a straightforward step-by-step procedure that they can follow. It means they can replicate the process no matter what type of nonfiction text they are asked to produce.

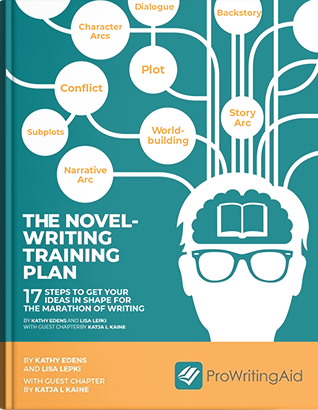

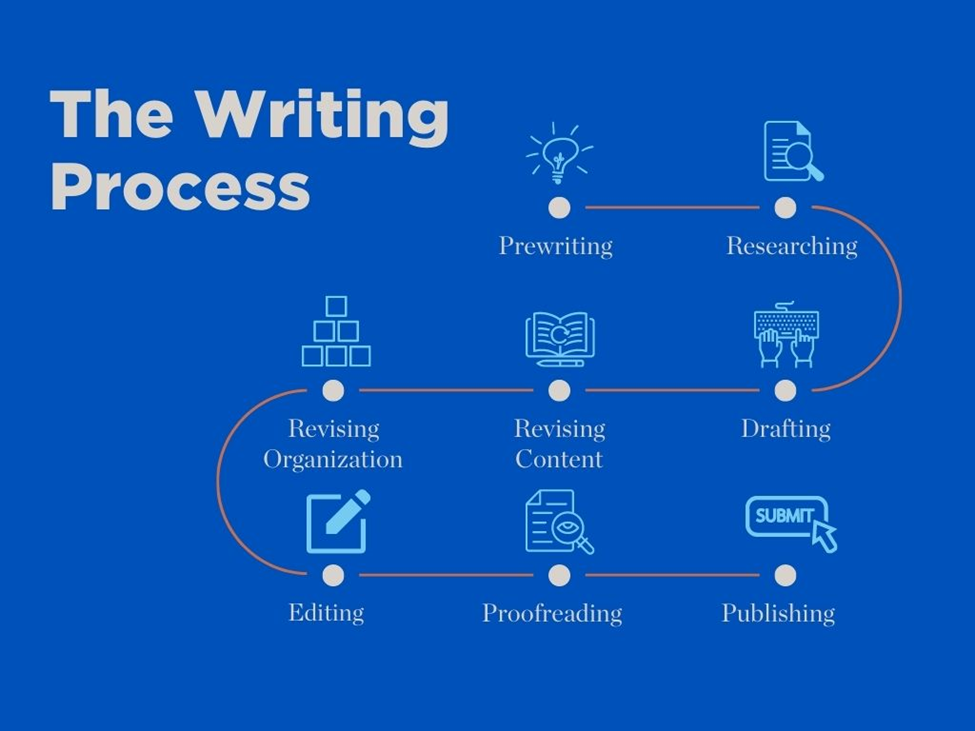

In this article, we’ll look at the 5 step writing process that guides students from prewriting to submitting their polished work quickly and easily.

While explaining each stage of the process in detail, we’ll suggest some activities you can use with your students to help them successfully complete each stage.

THE STAGES OF THE WRITING PROCESS

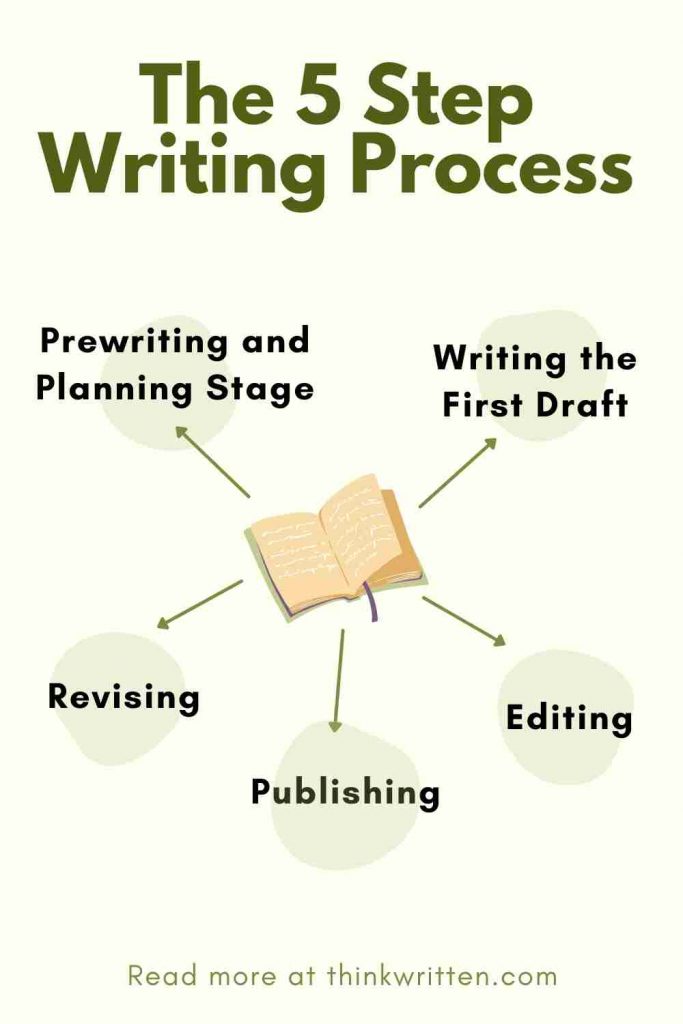

The five steps of the writing process are made up of the following stages:

- Pre-writing: In this stage, students brainstorm ideas, plan content, and gather the necessary information to ensure their thinking is organized logically.

- Drafting: Students construct ideas in basic sentences and paragraphs without getting caught up with perfection. It is in this stage that the pre-writing process becomes refined and shaped.

- Revising: This is where students revise their draft and make changes to improve the content, organization, and overall structure. Any obvious spelling and grammatical errors might also be improved at this stage.

- Editing: It is in this stage where students make the shift from improving the structure of their writing to focusing on enhancing the written quality of sentences and paragraphs through improving word choice, punctuation, and capitalization, and all spelling and grammatical errors are corrected. Ensure students know this is their final opportunity to alter their writing, which will play a significant role in the assessment process.

- Submitting / Publishing: Students can share their writing with the world, their teachers, friends, and family through various platforms and tools.

Be aware that this list is not a definitive linear process, and it may be advisable to revisit some of these steps in some cases as students learn the craft of writing over time.

Daily Quick Writes For All Text Types

Our FUN DAILY QUICK WRITE TASKS will teach your students the fundamentals of CREATIVE WRITING across all text types. Packed with 52 ENGAGING ACTIVITIES

STAGE ONE: THE WRITING PROCESS

GET READY TO WRITE

The prewriting stage covers anything the student does before they begin to draft their text. It includes many things such as thinking, brainstorming, discussing ideas with others, sketching outlines, gathering information through interviewing people, assessing data, and researching in the library and online.

The intention at the prewriting stage is to collect the raw material that will fuel the writing process. This involves the student doing 3 things:

- Understanding the conventions of the text type

- Gathering up facts, opinions, ideas, data, vocabulary, etc through research and discussion

- Organizing resources and planning out the writing process.

By the time students have finished the pre-writing stage, they will want to have completed at least one of these tasks depending upon the text type they are writing.

- Choose a topic: Ensure your students select a topic that is interesting and relevant to them.

- Brainstorm ideas: Once they have a topic, brainstorm and write their ideas down, considering what they already know about the topic and what they need to research further. Students might want to use brainstorming techniques such as mind mapping, free writing, or listing.

- Research: This one is crucial for informational and nonfiction writing. Students may need to research to gather more information and use reliable sources such as books, academic journals, and credible websites.

- Organize your ideas: This can be challenging for younger students, but once they have a collection of ideas and information, help them to organize them logically by creating an outline, using headings and subheadings, or grouping related ideas.

- Develop a thesis statement: This one is only for an academic research paper and should clearly state your paper’s main idea or argument. It should be specific and debatable.

Before beginning the research and planning parts of the process, the student must take some time to consider the demands of the text type or genre they are asked to write, as this will influence how they research and plan.

PREWRITING TEACHING ACTIVITY

As with any stage in the writing process, students will benefit immensely from seeing the teacher modelling activities to support that stage.

In this activity, you can model your approach to the prewriting stage for students to emulate. Eventually, they will develop their own specific approach, but for now, having a clear model to follow will serve them well.

Starting with an essay title written in the center of the whiteboard, brainstorm ideas as a class and write these ideas branching from the title to create a mind map.

From there, you can help students identify areas for further research and help them to create graphic organizers to record their ideas.

Explain to the students that while idea generation is an integral part of the prewriting stage, generating ideas is also important throughout all the other stages of the writing process.

STAGE TWO: THE WRITING PROCESS

PUT YOUR IDEAS ON PAPER

Drafting is when the student begins to corral the unruly fruits of the prewriting stage into orderly sentences and paragraphs.

When their writing is based on solid research and planning, it will be much easier for the student to manage. A poorly executed first stage can see pencils stuck at the starting line and persistent complaints of ‘writer’s block’ from the students.

However, do encourage your students not to get too attached to any ideas they may have generated in Stage 1. Writing is thinking too and your students need to leave room for their creativity to express itself at all stages of the process.

The most important thing about this stage is for the student to keep moving. A text is written word-by-word, much as a bricklayer builds a wall by laying brick upon brick.

Instill in your students that they shouldn’t get too hung up on stuff like spelling and grammar in these early stages.

Likewise, they shouldn’t overthink things. The trick here is to get the ideas down fast – everything else can be polished up later.

DRAFTING TEACHING ACTIVITY

As mentioned in the previous activity, writing is a very complex process and modeling goes a long way to helping ensure our students’ success.

Sometimes our students do an excellent job in the prewriting stage with understanding the text purpose, the research, and the planning, only to fall flat when it comes to beginning to write an actual draft.

Often, students require some clear modeling by the teacher to help them transition effectively from Stage 1 to Stage 2.

One way to do this for your class is to take the sketches, notes, and ideas one of the students has produced in Stage 1, and use them to model writing a draft. This can be done as a whole class shared writing activity.

Doing this will help your students understand how to take their raw material and connect their ideas and transition between them in the form of an essay.

STAGE THREE: THE WRITING PROCESS

POLISH YOUR THINKING

In Stage two, the emphasis for the student was on getting their ideas out quickly and onto the paper.

Stage three focuses on refining the work completed earlier with the reader now firmly at the forefront of the writer’s mind.

To revise, the student needs to cast a critical eye over their work and ask themselves questions like:

- Would a reader be able to read this text and make sense of it all?

- Have I included enough detail to help the reader clearly visualize my subject?

- Is my writing concise and as accurate as possible?

- Are my ideas supported by evidence and written in a convincing manner?

- Have I written in a way that is suitable for my intended audience?

- Is it written in an interesting way?

- Are the connections between ideas made explicit?

- Does it fulfill the criteria of the specific text type?

- Is the text organized effectively?

The questions above represent the primary areas students should focus on at this stage of the writing process.

Students shouldn’t slip over into editing/proofreading mode just yet. Let the more minor, surface-level imperfections wait until the next stage.

REVISING TEACHING ACTIVITY

When developing their understanding of the revising process, it can be extremely helpful for students to have a revision checklist to work from.

It’s also a great idea to develop the revision checklist as part of a discussion activity around what this stage of the writing process is about.

Things to look out for when revising include content, voice, general fluency, transitions, use of evidence, clarity and coherence, and word choice.

It can also be a good idea for students to partner up into pairs and go through each other’s work together. As the old saying goes, ‘two heads are better than one’ and, in the early days at least, this will help students to use each other as sounding boards when making decisions on the revision process.

STAGE FOUR: THE WRITING PROCESS

CHECK YOUR WRITING

Editing is not a different thing than writing, it is itself an essential part of the writing process.

During the editing stage, students should keep an eagle eye out for conventional mistakes such as double spacing between words, spelling errors, and grammar and punctuation mistakes.

While there are inbuilt spelling and grammar checkers in many of the most popular word processing programs, it is worth creating opportunities for students to practice their editing skills without the crutch of such technology on occasion.

Students should also take a last look over the conventions of the text type they are writing.

Are the relevant headings and subheadings in place? Are bold words and captions in the right place? Is there consistency across the fonts used? Have diagrams been labelled correctly?

Editing can be a demanding process. There are lots of moving parts in it, and it often helps students to break things down into smaller, more manageable chunks.

Focused edits allow the student the opportunity to have a separate read-through to edit for each of the different editing points.

For example, the first run-through might look at structural elements such as the specific structural conventions of the text type concerned. Subsequent run-throughs could look at capitalization, grammar, punctuation , the indenting of paragraphs, formatting, spelling, etc.

Sometimes students find it hard to gain the necessary perspective to edit their work well. They’re simply too close to it, and it can be difficult for them to see what is on the paper rather than see what they think they have put down.

One good way to help students gain the necessary distance from their work is to have the student read their work out loud as they edit it.

Reading their work out loud forces the student to slow down the reading process and it forces them to pay more attention to what’s written on the page, rather than what’s in their head.

It’s always helpful to get feedback from someone else. If time permits, get your students to ask a friend or other teacher to review their work and provide feedback. They may catch errors or offer suggestions your students haven’t considered.

All this gives the student a little more valuable time to catch the mistakes and other flaws in their work.

WRITING CHECKLISTS FOR ALL TEXT TYPES

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (92 Reviews)

EDITING TEACHING ACTIVITY

Students must have a firm understanding of what they’re looking to correct in the editing process to edit effectively. One effective way to ensure this understanding is to have them compile an Editing Checklist for use when they’re engaged in the editing process.

The Editing Checklist can be compiled as a whole-class shared writing activity. The teacher can scribe the students’ suggestions for inclusion on the checklist onto the whiteboard. This can then be typed up and printed off by all the students.

A fun and productive use of the checklist is for the students to use it in ‘editing pairs’.

Each student is assigned an editing partner during the editing stage of a writing task. Each student goes through their partner’s, work using the checklist as a guide, and then gives feedback to the other partner. The partner, in turn, uses the feedback in the final edit of their work.

STAGE FIVE: THE WRITING PROCESS

HAND IN YOUR WRITING

Now, it’s time for our students’ final part of the writing process. This is when they hand in their work to their teacher – aka you !

At this point, students should have one final reread of their work to ensure it’s as close to their intentions as possible, and then, finally, they can submit their work.

Giving the work over to an audience, whether that audience comes in the form of a teacher marking an assignment, publishing work in print or online, or making a presentation to classmates, can be daunting. It’s important that students learn to see the act of submitting their work as a positive thing.

Though this is the final stage of the writing process, students should be helped to see it for all it is. It is another step in the journey towards becoming a highly-skilled writer. It’s a further opportunity for the student to get valuable feedback on where their skills are currently at and a signpost to help them to improve their work in the future.

When the feedback comes, whether that’s in the form of teacher comments, grades, reviews, etc it should be absorbed by the student as a positive part of this improvement process.

Submitting TEACHING Activity

This activity is as much for the teacher as it is for the student.

Sometimes, our students think of feedback as a passive thing. The teacher makes some comments either in writing or orally and the student listens and carries on largely as before. We must help our students to recognize feedback as an opportunity for growth.

Feedback should be seen as a dialogue that helps our students to take control of their own learning.

For this to be the case, students need to engage with the feedback they’ve been given, to take constructive criticisms on board, and to use these as a springboard to take action.

One way to help students to do this lies in the way we format our feedback to our students. A useful format in this vein is the simple 2 Stars and a Wish . This format involves giving feedback that notes two specific areas of the work that the student did well and one that needs improvement. This area for improvement will provide a clear focus for the student to improve in the future. This principle of constructive criticism should inform all feedback.

It’s also helpful to encourage students to process detailed feedback by noting specific areas to focus on. This will give them some concrete targets to improve their writing in the future.

VIDEO TUTORIAL ON THE WRITING PROCESS

And there we have it. A straightforward and replicable process for our students to follow to complete almost any writing task.

But, of course, the real writing process is the ongoing one whereby our students improve their writing skills sentence-by-sentence and word-by-word over a whole lifetime.

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES RELATED TO THE WRITING PROCESS

7 Evergreen Writing Activities for Elementary Students

Text Types and Different Styles of Writing: The Complete Guide

Top 5 Essay Writing Tips

7 ways to write great Characters and Settings | Story Elements

6 Simple Writing Lessons Students Will Love

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

The Beginner's Guide to Writing an Essay | Steps & Examples

An academic essay is a focused piece of writing that develops an idea or argument using evidence, analysis, and interpretation.

There are many types of essays you might write as a student. The content and length of an essay depends on your level, subject of study, and course requirements. However, most essays at university level are argumentative — they aim to persuade the reader of a particular position or perspective on a topic.

The essay writing process consists of three main stages:

- Preparation: Decide on your topic, do your research, and create an essay outline.

- Writing : Set out your argument in the introduction, develop it with evidence in the main body, and wrap it up with a conclusion.

- Revision: Check your essay on the content, organization, grammar, spelling, and formatting of your essay.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Essay writing process, preparation for writing an essay, writing the introduction, writing the main body, writing the conclusion, essay checklist, lecture slides, frequently asked questions about writing an essay.

The writing process of preparation, writing, and revisions applies to every essay or paper, but the time and effort spent on each stage depends on the type of essay .

For example, if you’ve been assigned a five-paragraph expository essay for a high school class, you’ll probably spend the most time on the writing stage; for a college-level argumentative essay , on the other hand, you’ll need to spend more time researching your topic and developing an original argument before you start writing.

| 1. Preparation | 2. Writing | 3. Revision |

|---|---|---|

| , organized into Write the | or use a for language errors |

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Before you start writing, you should make sure you have a clear idea of what you want to say and how you’re going to say it. There are a few key steps you can follow to make sure you’re prepared:

- Understand your assignment: What is the goal of this essay? What is the length and deadline of the assignment? Is there anything you need to clarify with your teacher or professor?

- Define a topic: If you’re allowed to choose your own topic , try to pick something that you already know a bit about and that will hold your interest.

- Do your research: Read primary and secondary sources and take notes to help you work out your position and angle on the topic. You’ll use these as evidence for your points.

- Come up with a thesis: The thesis is the central point or argument that you want to make. A clear thesis is essential for a focused essay—you should keep referring back to it as you write.

- Create an outline: Map out the rough structure of your essay in an outline . This makes it easier to start writing and keeps you on track as you go.

Once you’ve got a clear idea of what you want to discuss, in what order, and what evidence you’ll use, you’re ready to start writing.

The introduction sets the tone for your essay. It should grab the reader’s interest and inform them of what to expect. The introduction generally comprises 10–20% of the text.

1. Hook your reader

The first sentence of the introduction should pique your reader’s interest and curiosity. This sentence is sometimes called the hook. It might be an intriguing question, a surprising fact, or a bold statement emphasizing the relevance of the topic.

Let’s say we’re writing an essay about the development of Braille (the raised-dot reading and writing system used by visually impaired people). Our hook can make a strong statement about the topic:

The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability.

2. Provide background on your topic

Next, it’s important to give context that will help your reader understand your argument. This might involve providing background information, giving an overview of important academic work or debates on the topic, and explaining difficult terms. Don’t provide too much detail in the introduction—you can elaborate in the body of your essay.

3. Present the thesis statement

Next, you should formulate your thesis statement— the central argument you’re going to make. The thesis statement provides focus and signals your position on the topic. It is usually one or two sentences long. The thesis statement for our essay on Braille could look like this:

As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness.

4. Map the structure

In longer essays, you can end the introduction by briefly describing what will be covered in each part of the essay. This guides the reader through your structure and gives a preview of how your argument will develop.

The invention of Braille marked a major turning point in the history of disability. The writing system of raised dots used by blind and visually impaired people was developed by Louis Braille in nineteenth-century France. In a society that did not value disabled people in general, blindness was particularly stigmatized, and lack of access to reading and writing was a significant barrier to social participation. The idea of tactile reading was not entirely new, but existing methods based on sighted systems were difficult to learn and use. As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness. This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people’s social and cultural lives.

Write your essay introduction

The body of your essay is where you make arguments supporting your thesis, provide evidence, and develop your ideas. Its purpose is to present, interpret, and analyze the information and sources you have gathered to support your argument.

Length of the body text

The length of the body depends on the type of essay. On average, the body comprises 60–80% of your essay. For a high school essay, this could be just three paragraphs, but for a graduate school essay of 6,000 words, the body could take up 8–10 pages.

Paragraph structure

To give your essay a clear structure , it is important to organize it into paragraphs . Each paragraph should be centered around one main point or idea.

That idea is introduced in a topic sentence . The topic sentence should generally lead on from the previous paragraph and introduce the point to be made in this paragraph. Transition words can be used to create clear connections between sentences.

After the topic sentence, present evidence such as data, examples, or quotes from relevant sources. Be sure to interpret and explain the evidence, and show how it helps develop your overall argument.

Lack of access to reading and writing put blind people at a serious disadvantage in nineteenth-century society. Text was one of the primary methods through which people engaged with culture, communicated with others, and accessed information; without a well-developed reading system that did not rely on sight, blind people were excluded from social participation (Weygand, 2009). While disabled people in general suffered from discrimination, blindness was widely viewed as the worst disability, and it was commonly believed that blind people were incapable of pursuing a profession or improving themselves through culture (Weygand, 2009). This demonstrates the importance of reading and writing to social status at the time: without access to text, it was considered impossible to fully participate in society. Blind people were excluded from the sighted world, but also entirely dependent on sighted people for information and education.

See the full essay example

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

The conclusion is the final paragraph of an essay. It should generally take up no more than 10–15% of the text . A strong essay conclusion :

- Returns to your thesis

- Ties together your main points

- Shows why your argument matters

A great conclusion should finish with a memorable or impactful sentence that leaves the reader with a strong final impression.

What not to include in a conclusion

To make your essay’s conclusion as strong as possible, there are a few things you should avoid. The most common mistakes are:

- Including new arguments or evidence

- Undermining your arguments (e.g. “This is just one approach of many”)

- Using concluding phrases like “To sum up…” or “In conclusion…”

Braille paved the way for dramatic cultural changes in the way blind people were treated and the opportunities available to them. Louis Braille’s innovation was to reimagine existing reading systems from a blind perspective, and the success of this invention required sighted teachers to adapt to their students’ reality instead of the other way around. In this sense, Braille helped drive broader social changes in the status of blindness. New accessibility tools provide practical advantages to those who need them, but they can also change the perspectives and attitudes of those who do not.

Write your essay conclusion

Checklist: Essay

My essay follows the requirements of the assignment (topic and length ).

My introduction sparks the reader’s interest and provides any necessary background information on the topic.

My introduction contains a thesis statement that states the focus and position of the essay.

I use paragraphs to structure the essay.

I use topic sentences to introduce each paragraph.

Each paragraph has a single focus and a clear connection to the thesis statement.

I make clear transitions between paragraphs and ideas.

My conclusion doesn’t just repeat my points, but draws connections between arguments.

I don’t introduce new arguments or evidence in the conclusion.

I have given an in-text citation for every quote or piece of information I got from another source.

I have included a reference page at the end of my essay, listing full details of all my sources.

My citations and references are correctly formatted according to the required citation style .

My essay has an interesting and informative title.

I have followed all formatting guidelines (e.g. font, page numbers, line spacing).

Your essay meets all the most important requirements. Our editors can give it a final check to help you submit with confidence.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

An essay is a focused piece of writing that explains, argues, describes, or narrates.

In high school, you may have to write many different types of essays to develop your writing skills.

Academic essays at college level are usually argumentative : you develop a clear thesis about your topic and make a case for your position using evidence, analysis and interpretation.

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

Your essay introduction should include three main things, in this order:

- An opening hook to catch the reader’s attention.

- Relevant background information that the reader needs to know.

- A thesis statement that presents your main point or argument.

The length of each part depends on the length and complexity of your essay .

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.

- It gives the reader a concise summary of your main point.

Without a clear thesis statement, an essay can end up rambling and unfocused, leaving your reader unsure of exactly what you want to say.

A topic sentence is a sentence that expresses the main point of a paragraph . Everything else in the paragraph should relate to the topic sentence.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- How long is an essay? Guidelines for different types of essay

- How to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples

- How to conclude an essay | Interactive example

More interesting articles

- Checklist for academic essays | Is your essay ready to submit?

- Comparing and contrasting in an essay | Tips & examples

- Example of a great essay | Explanations, tips & tricks

- Generate topic ideas for an essay or paper | Tips & techniques

- How to revise an essay in 3 simple steps

- How to structure an essay: Templates and tips

- How to write a descriptive essay | Example & tips

- How to write a literary analysis essay | A step-by-step guide

- How to write a narrative essay | Example & tips

- How to write a rhetorical analysis | Key concepts & examples

- How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

- How to write an argumentative essay | Examples & tips

- How to write an essay outline | Guidelines & examples

- How to write an expository essay

- How to write the body of an essay | Drafting & redrafting

- Kinds of argumentative academic essays and their purposes

- Organizational tips for academic essays

- The four main types of essay | Quick guide with examples

- Transition sentences | Tips & examples for clear writing

What is your plagiarism score?

ThinkWritten

The 5 Step Writing Process Every Writer Should Know

Learn the 5 Step Writing Process to help you become a better writer: planning, writing, revising, editing and finally publishing your work.

We may receive a commission when you make a purchase from one of our links for products and services we recommend. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for support!

Sharing is caring!

When it comes to the writing process, there are 5 steps that you need to know as a writer. It’s not as simple as just slapping down some words onto a page – there is a method that just straight up works.

In today’s post we are going to break down the 5 steps of the writing process so you can learn how to write more efficiently and share your words with the world.

Introduction to the 5 Steps of Writing

Everything is a process, from how you make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich to assembling a low-earth orbit space telescope.

The key thing, as any project manager or business analyst will tell you, is to define the core parts of the process and establish what is called the Critical Path – the series of steps that must be completed, one before the other, and the order in which they have to proceed.

When it comes to writing, the same order of operations has to be followed, from the shortest flash fiction to the longest epic saga, to produce a fully realized text.

The five steps of the writing process are Planning, Writing the first draft, Revising, Editing and Proofreading, and Publishing.

Let’s make this a nice and neat bulleted list for those of you who just want your fast facts about the 5 step writing process:

- Prewriting and Planning: The prep work you do before you write.

- Writing : The stage where you write your first rough draft.

- Revising: This is where you make structural changes to your work and make sure your story is solid with no inconsistencies or holes in the plot.

- Editing and Proofreading : This is where we get down to the nitty gritty of grammar, spelling and style.

- Publishing: The final step when you release your work into the wild for the world to read.

Each of these steps can be broken down into several parts, which we will cover in the paragraphs that follow.

Now, some of you may be thinking “Bill, this is nonsense. My process is organic; just goes with the flow, man.” And that’s fine. This article isn’t for you. You can go and be James Joyce putting out seven words a day and then wonder what order they’re supposed to go in.

The rest of us will go be writers and command our work in a manner that actually, you know – WORKS.

If you’re serious about finding a writing process that will make you a more efficient writer and help you turn out your best work, keep reading.

Strap in. This is going to be a long ride.

Step 1: Planning and Prewriting

You know the saying: “Those who fail to plan, plan to fail.” If I had a nickel for every time I heard my father say this phrase, I could have gotten through grad school without the loans.

As obvious as it is, it is still very true. It is one of those lessons that transcends disciplines, and is as easily applicable in the arts as it is the sciences. When we talk about planning for the written word, there are a few things it usually implies.

Here are some things you need to do in order to make sure you are maximizing the planning step of the writing process:

Preparation of Self and Space

You have to be ready mentally to dive into your writing, which means you need to plan a space and a schedule during which you will pursue your craft.

This can be anywhere or any time that you choose, but, for the best results, it needs to be consistent. Same place, same time, and for the same amount of time every day.

Free yourself from as many distractions as possible – that means no TV droning on in the background; no exceptions. No news, no game shows, no dramas, no nothing.

You need some kind of noise? Music is a great friend for that. Depending on what I am working on, I have a few playlists I work with.

When I am writing for my own nefarious purposes (read: working on my fantasy/sci-fi/horror fiction), I usually stick with a lot of metal music – Metallica, Amon Amarth, Sabaton, Blind Guardian, Lacuna Coil, and Pantera are a few favorites.

If I’m working on something more on the noir end of the spectrum, I’ll play some B.B. King or John Lee Hooker.

As I’m working on this article, I am listening to some Classic Rock favorites (AC/DC, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones).

Music helps me to set the mood for writing and guides my brain into the right groove. And since I typically know what I will be writing about, I can tailor that experience to improve my focus.

You could also do a million times worse than shutting off the internet to your computer (if that is how you are doing your writing) and leaving your cellphone in a drawer on the other side of the room. The rest of the world can wait.

You didn’t come into this space to play Candy Crush or surf social media. You’re here to work, Writer. The games and drama of people on the internet will be there when you’re done; I promise.

If you struggle with distraction while writing, see our post on 12 Tips for Distraction Free Writing for some ideas on how to get your work done in half the time.

Also, make sure your writing space is comfortable. Seriously, get an ergonomic office chair for writers – it’s worth the splurge!

Gabrylly Ergonomic Mesh Office Chair, High Back Desk Chair - Adjustable Headrest with Flip-Up Arms, Tilt Function, Lumbar Support and PU Wheels, Swivel Computer Task Chair, Grey

Preparation of material.

So. What are you going to write about? Do you know? Do you have an idea of where it is going and how long it will take to get there? Do you have a list of settings? Chapter summaries? Character profiles? Relevant research?

Oh, did you think we weren’t working?

A lot of what goes into good writing is preparing for what you are about to write.

Yes, there are writers out there that don’t necessarily need a legal pad full of notes to write a story, and you may not either, depending on what story you are going to tell.

But if you are going to write a tale of high seas adventure and can’t tell port (left) from starboard (right) or fore (front) from aft (rear) or what does it actually mean to be amidships (the middle of a ship, either laterally or longitudinally), your results are going to be less than stellar.

When it comes to characters and settings, it’s okay to go into this process with just a general idea of what the main characters are like. Of course, this isn’t a bad time to ask yourself some important character development questions either.

During this phase of the 5 step writing process, you’ll discover other less central characters and more facts about your protagonist /antagonist/ deuteragonists and the world they inhabit as you tell their stories.

You don’t need to know everything – that would be boring – but you need to take some time to figure out what you need to know.

For example – I like to occasionally write detective stories. I have never personally been a detective.

I studied law and evidentiary standards and trial procedure in undergrad while working the pre-law track of my English degree. There were bits and pieces I knew, and some gaps that I had erroneously filled with television police procedural nonsense (another reason to shoot your set – it’s making you think you know things you don’t know!), and the rest I filled in with research.

I picked through crime scene manuals, forensic science books, books on criminal profiling and common investigative techniques, and pored over books of case law concerning the kinds of crimes my detective was going to be investigating.

I actually have a large journal with over a hundred pages of notes and observations, drawings of the fictional crime scenes, and so on for a story I was working on some time ago. ( Learn how to create and use a writers notebook here !}

And this is where the caveat is introduced – don’t spend so much time researching that you forget to write the story.

Knowing what you need to know will get you where you need to be. You don’t have to become a detective to write compelling fiction in that genre. And what if you write it and it’s wrong? We’ll get to that later in the writing process.

Step 2: Writing the First Draft

Our second step of the writing process is what all of us as writers love: actually writing.

Putting words to paper is one of the most satisfying feelings I have ever experienced. Seeing all that lovely white space disappear behind rows and rows of text; feeling a story progress through the layers of development into a fully fledged narrative; watching my characters learn and grow as they surmount challenges or face the heartache of failure.

This is where the magic happens; it’s where the story begins to reveal itself. And like everything else, there are some guidelines to follow. Here are some things to remember when writing in Step 2 of the writing process:

Stay Focused

The story is in charge. You need to let the story dictate what you are going to do.

And as I have said before, try to keep to a schedule that works for you.

Some of you are morning people. I am not. I do my best work in the evening after my daughter has gone to bed. My wife will unwind in the living room with a movie or one of her favorite television shows, and I will take my laptop to the next room over to put myself in the zone.

I don’t shut the door, but you should keep your space as closed to the outside world as possible. That can mean putting on some really good headphones to listen to music or just cancel out external noises, but you need to eliminate as many distractions as possible.

Your goal when you start writing is to produce a complete First Draft of your story, and to that end you should do your level best to get straight through it.

Of course, distractions don’t just come from outside the writing environment. Sometimes they come from inside as well.

Don’t Edit While You Write

You will be tempted to reread your entire work up to that point and revel in its greatness. Don’t, because…

You will be tempted to tweak a passage that you now find lacks the force you thought it had. Don’t, because…

You will be tempted to rethink an entire plot line and potentially scrap an entire chapter of work. Don’t, because…

You will start to question the worthiness of how you have presented the story and then the story itself.

As we talk about in our article on How to Write 2,500 Words a Day , you don’t ever want to go back and start editing or tweaking in this stage of the writing process.

Here is what you need to remember : The First Draft is not the whole story. It is not where the creative process ends. It is important, though, because it is the first step in making your written work what you want it to be.

It doesn’t need to be done perfect; it just needs to be done.

With regard to us as writers, it is very easy to get sucked into the world of “what ifs” and lose our pathway to the end of the story.

Like the dwarves in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, we get lost in Mirkwood, unable to envision an end to our perilous journey; unable even to remember why we were on this journey in the first place. Keep above the trees, my friend, and keep yourself pointed at the goal.

Stay Organized

One way to help keep your eye on the prize is to be sure to keep notes concerning your characters and settings, and also to make little synopses of chapters as you go.

The temptation to reread your own material is going to be very real, so if something happens where you break your schedule and you need a refresher of where you were last, you can refer back to your notes and journal entries to find your bearings.

Personally, I use Microsoft OneNote to keep track of my notes and journal entries while writing. It’s free, which is my favorite price for everything, and it lets you create a structure for your notes that makes sense.

Keeping separate sections for settings, character details, chapter synopses, and personal thoughts at the end of each writing session (which I will wholly ignore once put down until we get to the next step in the process) will give you a quickly searchable reference guide to your own work later on.

Any similar tool will work, or, in lieu of a digital work space, a good five subject notebook will help to keep you organized. I like the idea of working longhand, and often do, but my handwriting is at its worst when my brain is at its fastest, and so for me it makes sense to keep it digital.

Step 3: Revision

So, you have officially completed the first draft of your manuscript. Congratulations! Great job! It is time to celebrate! Once you are done it’s time to take that completed work and…wait.

At this stage in the writing process, you need to wait .

Depending on the size of the manuscript you’ve produced, which will depend on what you are writing about and the format, you will want to sit on that bit of glory for a minute before you dig into the next phase.

How long? A day to three weeks would be ideal, with the shorter works (essays, flash fiction, etc) requiring the least amount of time to wait. Your Great American Novels require the longer period.

What you do during this waiting period is up to you – some may prefer to dig in and start on another work, others might take some time to read a few pieces in your market.

But what you are not allowed to do is anything related to the manuscript you just finished, including writing about the piece or reading any of your notes. Stuff it in a drawer and pretend it doesn’t exist.

You see, the third stage of the writing process is the revision process. It’s at this time where we will start working with the story again and going through any possible holes in the plot.

You cannot possibly do this well when the work is still fresh in your mind. You need to give it some space so you can clear your head and approach it with an unbiased mind.

The key here is to give the piece enough time to ferment that when you finally return to it, you do so with fresh eyes and a kind of separation from the piece.

The revision process of writing requires you to be objective, and that isn’t always possible when it comes to your darling text.

This is your baby, after all, and, like with children, it will be hard for you to see it in a light other than positive (or extremely negative) without first putting a wedge of objectivity between you and it.

Once the waiting period is over, you’re ready to really get into revising. Here’s some things to remember:

Read Straight Through Your Work Without Making Changes First

Yes. You read that right as well.

Once your prescribed cool-down time has been reached, it is time to crack the sarcophagus on that manuscript and take a gander.

As best as you are able, get through the whole thing in one sitting. Take notes (on a separate document, referencing page and paragraph numbers).

By now, you should be distanced well enough from the work to be able to put it under the microscope and extract those things that don’t belong, but also hook onto those things that really shine and think of ways to enhance them.

Like with writing your first draft, it is important to power through it. Don’t make the changes yet, just get a good idea of what needs done.

Kill Your Darlings

Once you’ve read through, it is time for the hard part. Taking stuff out.

When you write your first draft, you are telling the story to yourself. When you go through to make revisions, your job is to remove all the things that are not the story.

Places where you tell instead of show , or where you maybe are showing off a little too much with you research, or a sentence/paragraph/dialog/chapter that makes no sense in relation to the rest of the work, need to be removed.

You are going to run across some stunning prose in your journey of revision, not all of which belongs to the story. And that is where it gets difficult.

Your initial feeling might be to shoe-horn it in somehow, or just to leave it because “It’s just so good!” You have to fight this urge. The story doesn’t exist as a means for you to show off. The story is in charge – don’t forget that!

Add What’s Necessary

You are also going to come across some parts of your work that might need some additional build-out – more description, sharpening details, putting in something you realized you forgot on the first draft that is vital to the story.

It is also a chance to highlight some of the naturally occurring symbolism in your narrative (don’t go forcing symbolism, though; it never works the way you want it to) and add a little flourish here and there.

Remove Inconsistencies, Redundancies, and Unnecessaries

There is a good little equation to remember when revising:

This is the basic formula we’re looking for. If the first draft of your text is 50,000 words, you should strive to reduce that to 45,000 through the process of revision.

That does not mean removing chunks of narrative indiscriminately. On the contrary.

As I mentioned earlier, our job during revision is to remove everything that is not the story, and that means removing things that don’t fit or otherwise don’t need to be there.

While Revising, there are three basic things to look for:

Inconsistencies:

this is the biggest problem and the reason why you should take notes as you write concerning your settings and characters.

If a room in chapter one has a curio cabinet full of geological trinkets, but is full of Beanie Babies in chapter seven, that is an inconsistency that the reader is going to notice.

If a change like that is going to happen, there needs to be a reason, and it needs to further the story. Otherwise, cut it out.

The same is true if you read your protagonist acting in a way that is completely out of character for them – or any character doing so.

A lot of the connection you have with the reader depends on suspension of disbelief – which is not going to happen if your morally rigid main character does something suddenly of ambiguous moral distinction.

Redundancies:

Did your character tell the same piece of back story twice? Did you repeat something else in a specific scene? Do you have two bars in the same town with the same name? Change it or get rid of it. Duplication makes your story less interesting.

Unnecessaries:

This is anything else that is not the story or in service to the story. Get rid of it. Even if the prose is brilliant, or it showcases your amazing research, or it was fun to write.

Don’t Go Alone

This is also the time when you can start introducing your work to other readers. In fact, I would encourage it. Find a colleague or two you can trust to be honest in their assessment and let them read your work.

Seek their feedback and, if it makes sense, implement it. You ostensibly wrote your manuscript with the intent to share it with others – test your readership and see what comes back your way.

The only rule is this – you aren’t allowed to ask about it until after they are done reading. Don’t be so needy. Give them some space.

If possible, join a writer’s group . They are going to be far more objective and unbiased that family members or friends.

Step 4: Editing and Proofreading Your Final Draft

The third step of the writing process is editing and proofreading.

“Bill, isn’t proofreading and editing the same thing as revising?”

First, revising is the process by which a writer examines their work as a whole object – the completed narrative. You will go through several passes of revision before you come to this final step in the process of creating your completed work.

Only once you are totally satisfied with the story as a whole being, that is when you need to make one last pass through your work to tighten every screw.

Proofreading is the third step of the writing process where we start worrying about things like grammar, spelling and punctuation. Your story should be solid at this point – now we’re just making sure it is legible.

Here is the difference between revising and editing , just to be clear we’re on the same page.

Here are some tips for the proofreading and editing stage of the process:

Proofreading is the phase of the process where you go over your work with a fine-toothed comb. You are no longer reading to make sure things make sense. You’ve done enough of that.

This is the mechanical inspection of your work to make sure that you’re using the proper versions of you’re/your/yore, or/oar/ore, their/there/they’re, etc.

Because this part of the process requires you to stop thinking in terms of the story, you need to take measures to slow your pace significantly to avoid reading for pleasures and missing some error.

If the piece is short enough, this isn’t a problem. If you’ve written a novel or novella, however, then it becomes more difficult.

When I have done revision and proofreading for other people’s manuscripts, I will do a single quick read-through of the entire work to get a feel for the writer’s voice. Then I do the editing by reading the work backwards to keep my brain from engaging with the story on too intimate a basis. This trick can work for you as well.

Have Your Toolkit Handy

It takes a special kind of person to remember all the grammatical and linguistic rules for any language, English or otherwise. That said, it is a good idea to have some resources available to help with this process: a dictionary, a thesaurus, and a style manual.

Your Dictionary

![what are the five stages of essay writing [Paperback Oxford English Dictionary] [By: oxford university press] [January, 2012]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41INyanbMsL._SS520_.jpg)

[Paperback Oxford English Dictionary] [By: oxford university press] [January, 2012]

A dictionary is an obvious choice, and my recommendation is the Oxford English Dictionary (the American desk reference, not this 20 volume set that I would love to own if I had the space and the budget).

The Oxford English Dictionary, Volume 1-20, (20 Volume Set)

You need to know how to spell words and what they mean so that you are using them properly.

If you describe someone as solipsistic, but don’t know that it can mean someone who is very self-centered, or the philosophical concept that only the self can be known, then you could either use it out of context or just plain incorrectly.

Yes, spellcheck is a thing, but it’s not always accurate. Software developers will ensure that the most commonly used words are in the database, but it’s up to you to fill in the blank spots.

A thesaurus is another excellent tool to have, and once more I turn to Oxford with their Writer’s Thesaurus , which gives example sentences for words and synonyms, plus assistance on picking the right word for a given situation.

Oxford American Writer's Thesaurus

The reason you need a thesaurus during the proofreading phase is to eliminate a few more of those redundancies we mentioned earlier.

Nothing is more distracting when reading than a writer who uses the same word over and over again. If you find yourself doing this, take a gander at the thesaurus and use an alternate word.

A Style Manual

A style manual is just a reference for the rules of grammar. In my eye, there can be none better than Strunk and White’s Elements of Style .

The Elements of Style, Fourth Edition

I was introduced to this little book (and it is small) in 10th grade and dismissed it until I started taking writing seriously in my early 20s.

It is by far the most succinct, comprehensive references on English grammar ever to be set down.

I have read through style manuals of many kinds – MLA, AP, Chicago, APA – and had to use all of them. But I always come back to Elements in the end, and save the others for how to cite my references.

These tools will serve you very well in the proofreading stage of the writing process. Don’t be tempted to solely rely on your word processing software to catch every mistake.

Consider an Editor at This Stage

An editor is someone who can help you with the proofreading process. It is very easy for us to overlook our mistakes in our writing. Having a professional set of eyes on your work may make all the difference in whether your manuscript is accepted .

Step 4: Publishing Your Work

Congratulations! You have finished planning, writing, rewriting, and editing your work. You are ready for the final stage of the writing process, which is publishing your work.

Your test readers have given you rave reviews and lots of constructive criticism. Being the wise author that you are, you have taken this to heart and used their feedback to make your work even better. So how do you get your work in front of other people?

There are two main types of publishing to consider, which are traditional publishing and self publishing. For detailed information on how to publish your work, check out our post on How to Publish a Book that outlines everything you need to do step by step in detail.

When publishing, you need to think about what you wrote and where it will best meet your target audience. If you are publishing on your own blog, it’s as simple as just hitting the “Publish” button once the work is ready to release in the wild.

Of course, most of us want to reach a wider scope of an audience than just our blog readers. This is where we have to consider the pros and cons between traditional publishing and self publishing.

Traditional Publishing

The standard way is to shop your manuscript around to publishers that service your genre. Get a copy of Writer’s Marketplace and sift through the columns of publishers and literary agents to find your best matches.

The current versions of Marketplace will usually give some insight into whether or not a publisher is willing to work with new authors (assuming this is your first time around the publishing track), as well as how they accept entries.

If you are set in getting your work seen in print or you want to publish with established websites that have an entire editorial staff, you are going to need to consider the traditional publishing route.

Note that the major publishing houses will not take any type of unsolicited manuscript and require you work directly with an agent who submits your work on your behalf.

When you submit your manuscript , never send the whole thing. Follow the directions the publisher specifies!

Usually this means you will send only a few sample chapters, typically the first three. If they like your work, they’ll ask to read the whole thing.

If they make an offer, be sure to have a good look at anything requiring your signature.

Small journals may only make you sign a release to allow them to publish the work, and throw in a rider that allows you to keep overall publishing rights.

Bigger publishing houses, dealing with bigger texts will likely have much more complicated contracts requiring you to hire some kind of representation, be it a literary agent or a lawyer.

I would recommend the former if you are going to shop around a big manuscript as they will have a better understanding of the market and the publishers themselves.

Self Publishing

Of course, self publishing is a very popular option nowadays as well. You get none of the hassle of working with a professional publisher, but also none of the marketing and coverage that they provide.

There are many advantages to self publishing if you already have an audience and platform. If you have a site like this one where you are getting hundreds of thousands of visitors a month, you probably don’t have to rely too much on any marketing a traditional publisher might provide.

Amazon will let you publish your work electronically, should you choose, and there are a host of hard-bound self-publishing firms out there now as well.

Just remember, what you save in hassle, you lose in selling assistance, access to larger markets and marketing, and you have to foot the bill yourself.

One thing that is very important is you do not confuse self publishing with vanity publishers. Vanity publishers are very predatory in nature and often prey on very mediocre at best authors who simply just want to see their name in print. The costs can be outrageous with them, so do your homework!

Depending on your goal for your work, self publishing can be a great way to get started, and if your work sells well on Amazon under the self-publishing banner, it could still get picked up for wider distribution by another, larger publisher. The sky is the limit!

I hope this article on the 5 steps of the writing process is helpful for you. I know this is a lot to take in all at once but it will be worth it when you slow down and have a method to keep you on track and get your work read by others.

Do you have any questions or comments about the 5 step writing process? Share your thoughts in the comments section below!

Bill comes from a mishmash of writing experiences, having covered topics ranging from defining thematic periodicity of heroic medieval literature to technical manuals on troubleshooting mobile smart device operating systems. He holds graduate degrees in literature and business administration, is an avid fan of table-top and post-to-play online role playing games, serves as a mentor on the D&D DMs Only Facebook group, and dabbles in writing fantasy fiction and passable poetry when he isn’t busy either with work or being a husband and father.

Similar Posts

5 Signs of a Strong Novel Plot

10 Tips for Writing a Novel

Allusion Examples and Why You Need Allusion in Your Writing

How to Write a Short Story

What is a Deuteragonist?

Character Development: How to Write Strong Characters in Your Novel

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

From Draft to Done: A Full Breakdown of the Writing Process

By Micah McGuire

So you’ve decided to write a story and hope to publish it. For write-to-publish newbies, you might want to know what you’re getting into, especially if you’re working on a large project like a novel. It’s natural to wonder: how many drafts will it take before my story is ready to publish?

Unfortunately, you’re more likely to answer “how many licks does it take to get to the center of a Tootsie pop?” before knowing how many drafts you’ll need before publication. Here’s why.

A rose by any other name: What’s in a draft?

The biggest problem with breaking down the writing process from first to last draft can be linked back to one little detail:

How do you define a draft?

There are as many ways to define the word “draft” as there are writers. Which means every writer’s version of “the writing process” will look different. It’s impossible to say: “oh, writing a novel will take five drafts.”

Because the definition of “draft” can vary so much, it’s useful to think about drafting on a spectrum:

- The fewest drafts: Only rewrites count

- Middle-of-the-road: The fiction patching method

- The most drafts: Every change counts

Keep reading for more on how this draft spectrum works.

Only rewrites count

The minimalist take on drafting. By this definition, only full rewrites of a piece count as a true draft. Which means when saving a manuscript to a file, you wouldn’t alter the file name until you completely rewrite that chapter, section, or piece.

The advantage here lies in simplicity: you have fewer files to juggle since you’re saving to the same file over and over. But you may risk losing details from earlier drafts because of the repeat saves. Plus, for larger projects like novels, you need to divide your manuscript into parts and have a file system in place to keep track of your revisions.

The fiction patching method

While this started as more of a joke between writers on social media, it’s a great middle-of-the-road way to think about drafting. It takes cues from software versioning , noting that not every change means a new draft. Smaller changes are like patches (the version’s third number) and rewrites might be closer to updates (the second number) rather than a new version release/new draft (the first number).

So draft names might look like this:

- Draft 0.1: Outline

- Draft 1.0: Rough Draft

- Draft 1.5: Rough draft with some rewrites

- Draft 2.0: Rough draft fully rewritten with feedback from critique partners

- Draft 2.0.1: Rewritten rough draft with a minor tweak (or “patch”) to the protagonist’s motivation

Here, you can always revisit an older version to review details you want to re-emphasize in rewrites. But, it’s easy to end up with dozens if not hundreds of files and you’ll have to decide what constitutes a “patch,” an update and a brand new release ahead of time to stay consistent with naming.

Every change counts

Taken to its extreme, this approach to drafting may seem silly. Why would anyone count every change as a new draft? But most writers favor a less extreme version of this approach. It’s how we end up with draft names like “Final draft” and “Final draft I swear,” and “No really this is the last draft.”

Fortunately, this means you’ll never lose a detail again and you have complete control over naming conventions. However, you can end up with hundreds of files in a blink. And, if you’re not careful with what you name each file, it may take some detective work to figure out which one is the most recent version.

So, where do you fall on the drafting spectrum? Keeping it in mind can help you estimate the number of drafts you might need before publishing your story.

From outline to finished product: the writing process

Now that you have a better understanding of what the word “draft” means to you, you can look at the writing process with fresh eyes.

While it’s impossible to say how many drafts a manuscript takes, it is possible to break the writing process down into stages . We can define the process in 5 stages:

- The rough draft

- Content edits

- Proofreading

Try not to think of this as a step-by-step process. It’s more like a series of loops as each one of these stages may require multiple revision rounds. Sometimes, the process can feel like one step forward and two steps back, but each round will strengthen your manuscript.

Let’s look at each stage.

1. Outlining

2. the rough draft, 3. content edits, 4. line edits, 5. proofreading.

We couldn’t talk about the writing process without touching on outlining. Planners, applaud and cheer as much as you’d like—just make sure not to upset your color-coded highlighter sets.

Pantsers, resist the urge to skip this. It still applies to you, even if you think it doesn’t.

Like a draft, there are thousands of ways to define the term “outline.” But whether you fall on the planner detailed scene-by-scene index card method or the pantser “I know the ending. How I get there is up to the characters” end of the spectrum, you need some form of an outline.

The point of an outline is to ensure your writing produces a story with a plot. Otherwise, you risk writing pages and pages in which your characters run around and do things but never advance the plot.

So at the bare minimum, an outline requires you know:

- Who your protagonist is

- Who your antagonist is

- Why the protagonist and antagonist have a problem with each other (otherwise known as your central conflict)

- Where the story starts

- Where the story ends

Pantsers, breathe a sigh of relief: you don’t have to answer any of these questions in detail for it to count as an outline. You just need to know where you’re starting and where you’re going. You don’t even need to use a pen and paper— try these three fun outlining methods .

Spend as much or as little time on this stage as you’d like.

But once your outline is complete, you can move onto what most of us think of as the “real” writing: drafting.

This is the most crucial aspect of writing a story. Fortunately, it’s also the one stage that’s impossible to get wrong.

There’s one goal to a rough draft: get the story out of your head and onto a page in a somewhat comprehensible form. That’s the only focus. So if you’re writing, you’re succeeding.

Most writers face perfectionist paralysis in the rough draft stage. We think that because the writing doesn’t match what we see it in our heads, it’s bad. Or the story’s going to be bad. Or we’re bad writers.

If you’re in the analysis paralysis camp, invoke Anne Lamott’s “Sh*tty First Drafts” rule . To quote the late great Terry Pratchett, “the first draft is you telling yourself the story.”

So don’t judge it. Or better yet, accept that it’s bad. Cringe, wince, make faces. Just get it down on the page. Because you can’t edit a story that’s floating around in your head.

So you’ve finished your rough draft. Take a moment to celebrate! Your story is out of your head and onto the page.

Next up: editing.

Writers usually see editing as a terrifying mountain or a fun challenge. But there’s no denying it’s a monumental job, no matter how long or short your story is.

Because the scope of editing can be overwhelming, it’s easiest to break the process up into steps. Those steps are:

Here’s a breakdown of each.

A content edit is just what it sounds like: a pass editing the content and story of your work. This is the place to catch plot holes, character inconsistencies, and scenes that are a bit of a slog. For some, it’s easier to think of this as a “rewriting” round rather than an “editing” round since you’re making large-scale changes.

Sometimes, content edits are obvious on a read-through of a rough draft. Yet the longer you’ve worked on a piece, the harder it is to spot those editing opportunities.

Self-editing

Each draft you write marks progress in your writing abilities. When you read back over the first few scenes you wrote, you’ll be amazed at how far you’ve come. This is why the self-edit is so important. You need to apply your newfound skills and perspective to your manuscript so that it’s the best it can be before you open it up for feedback.

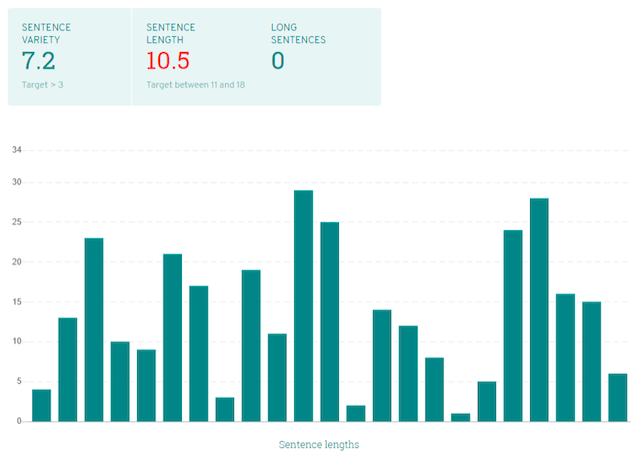

The first step is to use an editing software like ProWritingAid to help you spot issues with overly long sentences, awkward constructions, unruly dialogue tags, and pacing. Using an editing tool at this stage helps you to get the most out of any human beta-readers and editors you may reach out to down the line.

Some reports give you the tools to visualise your draft at a glance to see where you need to focus. The Sentence Length Report shows you all of your sentences in a handy bar chart so you can cut long, winding sentences down to size. This will help keep your ideas clear and avoid any readability issues.

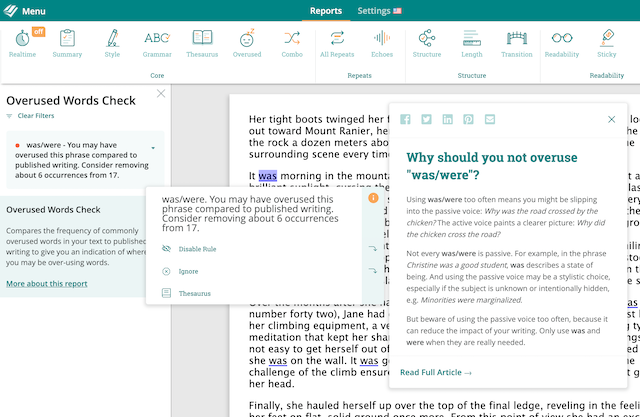

Other reports let you get to work directly on your manuscript, like the Overused Words Report. This report highlights words that are often overused in published writing. These are words like could , just , and feel that point to vagueness or telling rather than showing.

The report lets you pick out these words and change them to make sure your description is doing the work it needs to to immerse your readers.

Learn how to approach the self-edit, and how ProWritingAid can help .

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Deb-Nov2015-5895870e3df78caebc88766f.jpg)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Table of contents. Step 1: Prewriting. Step 2: Planning and outlining. Step 3: Writing a first draft. Step 4: Redrafting and revising. Step 5: Editing and proofreading. Other interesting articles. Frequently asked questions about the writing process.

Editing and revising. Once you have a completed rough draft, the next step in the writing process is to shape it into a final draft. This is known asediting. As you move through the writing process,you'll employ different kinds of editing. At this stage, you're content editing, line editing, and copy editing.

Sometimes ideas do not flow easily, and the essay that you originally start out to write is not the essay that you end up writing. Often the stages proceed erratically and overlap; the important thing is to keep writing and improving until a final product is achieved. The more that you write, the better you will become as a writer.

Understanding how and why you write the way you do allows you to treat your writing like the job it is, while allowing your creativity to run wild. Every writer works in a different way. Some writers work straight through from beginning to end. Others work in pieces they arrange later, while others work from sentence to sentence.

THE STAGES OF THE WRITING PROCESS. The five steps of the writing process are made up of the following stages: Pre-writing: In this stage, students brainstorm ideas, plan content, and gather the necessary information to ensure their thinking is organized logically. Drafting: Students construct ideas in basic sentences and paragraphs without ...

The Writing Process. These OWL resources will help you with the writing process: pre-writing (invention), developing research questions and outlines, composing thesis statements, and proofreading. While the writing process may be different for each person and for each particular assignment, the resources contained in this section follow the ...

Essay writing process. The writing process of preparation, writing, and revisions applies to every essay or paper, but the time and effort spent on each stage depends on the type of essay.. For example, if you've been assigned a five-paragraph expository essay for a high school class, you'll probably spend the most time on the writing stage; for a college-level argumentative essay, on the ...

The writing process looks different for everyone, but there are... Do you get overwhelmed or simply don't know where to start when it comes to academic writing? The writing process looks different ...

When it comes to writing, the same order of operations has to be followed, from the shortest flash fiction to the longest epic saga, to produce a fully realized text. The five steps of the writing process are Planning, Writing the first draft, Revising, Editing and Proofreading, and Publishing. Let's make this a nice and neat bulleted list ...

Writing is a process, not the end product! There's a lot more to a successful assignment than writing out the words. Reading, thinking, planning, and editing are also vital parts of the process. These steps take you through the whole writing process: before, during and after: 1. Read the assignment instructions thoroughly.

Draft 1.0: Rough Draft. Draft 1.5: Rough draft with some rewrites. Draft 2.0: Rough draft fully rewritten with feedback from critique partners. Draft 2.0.1: Rewritten rough draft with a minor tweak (or "patch") to the protagonist's motivation.

Step 1: Prewriting. Think and Decide. Make sure you understand your assignment. See Research Papers or Essays. Decide on a topic to write about. See Prewriting Strategies and Narrow your Topic. Consider who will read your work. See Audience and Voice. Brainstorm ideas about the subject and how those ideas can be organized.

In other words, you start with the endpoint in mind. You look at your writing project the way your audience would. And you keep its purpose foremost at every step. From planning, we move to the next fun stage. 2. Drafting (or Writing the First Draft) There's a reason we don't just call this the "rough draft," anymore.

Resources for Writers: The Writing Process. Writing is a process that involves at least four distinct steps: prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing. It is known as a recursive process. While you are revising, you might have to return to the prewriting step to develop and expand your ideas.

Anything you write will benefit from learning these simple parts of an essay: Here are five steps to make it happen: ThoughtCo is part of the Dotdash Meredith publishing family. Every essay--regardless of its topic--should include a title, purpose/thesis, introduction, body, and conclusion.

In other words, if the end goal is a five-paragraph essay, prewriting is every step that comes before actually writing five paragraphs. Prewriting is sometimes called the planning stage ...

prompt on your own. You'd be surprised how often someone comes to the Writing Center to ask for help on a paper before reading the prompt. Once they do read the prompt, they often find that it answers many of their questions. When you read the assignment prompt, you should do the following: • Look for action verbs.

Usually, writers start with choosing topics and brainstorming, and then they may outline their papers, and compose sentences and paragraphs to make a rough draft. After they make a rough draft, writers may begin revising their work by adding more sentences, or removing sentences. Writers may then edit their rough draft by changing words and ...

While no guide can help you find what situations will work best for you to write, there are steps in the writing process that promote a cleaner, better final draft. The general steps are: discovery\investigation, prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing. Discovery/Investigation Prewriting Drafting Revising Editing Formatting, Inner-text ...

An essay is a written composition that presents and supports a particular idea, argument, or point of view. It's a way to express your thoughts, share information, and persuade others to see things from your perspective. Essays come in various forms, such as argumentative, persuasive, expository, and descriptive, each serving a unique purpose.

Writing a good essay is a multi-stage process ... The research stage should take up more than half of the total time available. But remember, these are just general guidelines. You may need to adjust your approach to suit particular assignments and/or your tutors' expectations.

Basic essay structure: the 3 main parts of an essay. Almost every single essay that's ever been written follows the same basic structure: Introduction. Body paragraphs. Conclusion. This structure has stood the test of time for one simple reason: It works. It clearly presents the writer's position, supports that position with relevant ...

The writing process takes time, but makes the act of writing the essay less stressful. The amount of time you spend on each part will vary depending on the length and complexity of your project. You know your limitations, so give yourself plenty of time to complete each part. It looks like Sarah put in the hard work and followed the writing ...