Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

The 3 Popular Essay Formats: Which Should You Use?

General Education

Not sure which path your essay should follow? Formatting an essay may not be as interesting as choosing a topic to write about or carefully crafting elegant sentences, but it’s an extremely important part of creating a high-quality paper. In this article, we’ll explain essay formatting rules for three of the most popular essay styles: MLA, APA, and Chicago.

For each, we’ll do a high-level overview of what your essay’s structure and references should look like, then we include a comparison chart with nitty-gritty details for each style, such as which font you should use for each and whether they’re a proponent of the Oxford comma. We also include information on why essay formatting is important and what you should do if you’re not sure which style to use.

Why Is Your Essay Format Important?

Does it really matter which font size you use or exactly how you cite a source in your paper? It can! Style formats were developed as a way to standardize how pieces of writing and their works cited lists should look.

Why is this necessary? Imagine you’re a teacher, researcher, or publisher who reviews dozens of papers a week. If the papers didn’t follow the same formatting rules, you could waste a lot of time trying to figure out which sources were used, if certain information is a direct quote or paraphrased, even who the paper’s author is. Having essay formatting rules to follow makes things easier for everyone involved. Writers can follow a set of guidelines without trying to decide for themselves which formatting choices are best, and readers don’t need to go hunting for the information they’re trying to find.

Next, we’ll discuss the three most common style formats for essays.

MLA Essay Format

MLA style was designed by the Modern Language Association, and it has become the most popular college essay format for students writing papers for class. It was originally developed for students and researchers in the literature and language fields to have a standardized way of formatting their papers, but it is now used by people in all disciplines, particularly humanities. MLA is often the style teachers prefer their students to use because it has simple, clear rules to follow without extraneous inclusions often not needed for school papers. For example, unlike APA or Chicago styles, MLA doesn’t require a title page for a paper, only a header in the upper left-hand corner of the page.

MLA style doesn’t have any specific requirements for how to write your essay, but an MLA format essay will typically follow the standard essay format of an introduction (ending with a thesis statement), several body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

One of the nice things about creating your works cited for MLA is that all references are structured the same way, regardless of whether they’re a book, newspaper, etc. It’s the only essay format style that makes citing references this easy! Here is a guide on how to cite any source in MLA format. When typing up your works cited, here are a few MLA format essay rules to keep in mind:

- The works cited page should be the last paper of your paper.

- This page should still be double-spaced and include the running header of your last name and page number.

- It should begin with “Works Cited” at the top of the page, centered.

- Your works cited should be organized in alphabetical order, based on the first word of the citation.

APA Essay Format

APA stands for the American Psychological Association. This format type is most often used for research papers, specifically those in behavioral sciences (such as psychology and neuroscience) and social sciences (ranging from archeology to economics). Because APA is often used for more research-focused papers, they have a more specific format to follow compared to, say, MLA style.

All APA style papers begin with a title page, which contains the title of the paper (in capital letters), your name, and your institutional affiliation (if you’re a student, then this is simply the name of the school you attend). The APA recommends the title of your paper not be longer than 12 words.

After your title page, your paper begins with an abstract. The abstract is a single paragraph, typically between 150 to 250 words, that sums up your research. It should include the topic you’re researching, research questions, methods, results, analysis, and a conclusion that touches on the significance of the research. Many people find it easier to write the abstract last, after completing the paper.

After the abstract comes the paper itself. APA essay format recommends papers be short, direct, and make their point clearly and concisely. This isn’t the time to use flowery language or extraneous descriptions. Your paper should include all the sections mentioned in the abstract, each expanded upon.

Following the paper is the list of references used. Unlike MLA style, in APA essay format, every source type is referenced differently. So the rules for referencing a book are different from those for referencing a journal article are different from those referencing an interview. Here’s a guide for how to reference different source types in APA format . Your references should begin on a new page that says “REFERENCES” at the top, centered. The references should be listed in alphabetical order.

Chicago Essay Format

Chicago style (sometimes referred to as “Turabian style”) was developed by the University of Chicago Press and is typically the least-used by students of the three major essay style formats. The Chicago Manual of Style (currently on its 17th edition) contains within its 1000+ pages every rule you need to know for this style. This is a very comprehensive style, with a rule for everything. It’s most often used in history-related fields, although many people refer to The Chicago Manual of Style for help with a tricky citation or essay format question. Many book authors use this style as well.

Like APA, Chicago style begins with a title page, and it has very specific format rules for doing this which are laid out in the chart below. After the title page may come an abstract, depending on whether you’re writing a research paper or not. Then comes the essay itself. The essay can either follow the introduction → body → conclusion format of MLA or the different sections included in the APA section. Again, this depends on whether you’re writing a paper on research you conducted or not.

Unlike MLA or APA, Chicago style typically uses footnotes or endnotes instead of in-text or parenthetical citations. You’ll place the superscript number at the end of the sentence (for a footnote) or end of the page (for an endnote), then have an abbreviated source reference at the bottom of the page. The sources will then be fully referenced at the end of the paper, in the order of their footnote/endnote numbers. The reference page should be titled “Bibliography” if you used footnotes/endnotes or “References” if you used parenthetical author/date in-text citations.

Comparison Chart

Below is a chart comparing different formatting rules for APA, Chicago, and MLA styles.

How Should You Format Your Essay If Your Teacher Hasn’t Specified a Format?

What if your teacher hasn’t specified which essay format they want you to use? The easiest way to solve this problem is simply to ask your teacher which essay format they prefer. However, if you can’t get ahold of them or they don’t have a preference, we recommend following MLA format. It’s the most commonly-used essay style for students writing papers that aren’t based on their own research, and its formatting rules are general enough that a teacher of any subject shouldn’t have a problem with an MLA format essay. The fact that this style has one of the simplest sets of rules for citing sources is an added bonus!

What's Next?

Thinking about taking an AP English class? Read our guide on AP English classes to learn whether you should take AP English Language or AP English Literature (or both!)

Compound sentences are an importance sentence type to know. Read our guide on compound sentences for everything you need to know about compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences.

Need ideas for a research paper topic? Our guide to research paper topics has over 100 topics in ten categories so you can be sure to find the perfect topic for you.

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

College Application Essay Format Rules

The college application essay has become the most important part of applying to college. In this article, we will go over the best college essay format for getting into top schools, including how to structure the elements of a college admissions essay: margins, font, paragraphs, spacing, headers, and organization.

We will focus on commonly asked questions about the best college essay structure. Finally, we will go over essay formatting tips and examples.

Table of Contents

- General college essay formatting rules

- How to format a college admissions essay

- Sections of a college admissions essay

- College application essay format examples

General College Essay Format Rules

Before talking about how to format your college admission essays, we need to talk about general college essay formatting rules.

Pay attention to word count

It has been well-established that the most important rule of college application essays is to not go over the specific Application Essay word limit . The word limit for the Common Application essay is typically 500-650 words.

Not only may it be impossible to go over the word count (in the case of the Common Application essay , which uses text fields), but admissions officers often use software that will throw out any essay that breaks this rule. Following directions is a key indicator of being a successful student.

Refocusing on the essay prompt and eliminating unnecessary adverbs, filler words, and prepositional phrases will help improve your essay.

On the other hand, it is advisable to use almost every available word. The college essay application field is very competitive, so leaving extra words on the table puts you at a disadvantage. Include an example or anecdote near the end of your essay to meet the total word count.

Do not write a wall of text: use paragraphs

Here is a brutal truth: College admissions counselors only read the application essays that help them make a decision . Otherwise, they will not read the essay at all. The problem is that you do not know whether the rest of your application (transcripts, academic record, awards, etc.) will be competitive enough to get you accepted.

A very simple writing rule for your application essay (and for essay editing of any type) is to make your writing readable by adding line breaks and separate paragraphs.

Line breaks do not count toward word count, so they are a very easy way to organize your essay structure, ideas, and topics. Remember, college counselors, if you’re lucky, will spend 30 sec to 1 minute reading your essay. Give them every opportunity to understand your writing.

Do not include an essay title

Unless specifically required, do not use a title for your personal statement or essay. This is a waste of your word limit and is redundant since the essay prompt itself serves as the title.

Never use overly casual, colloquial, or text message-based formatting like this:

THIS IS A REALLY IMPORTANT POINT!. #collegeapplication #collegeessay.

Under no circumstances should you use emojis, all caps, symbols, hashtags, or slang in a college essay. Although technology, texting, and social media are continuing to transform how we use modern language (what a great topic for a college application essay!), admissions officers will view the use of these casual formatting elements as immature and inappropriate for such an important document.

How To Format A College Application Essay

There are many tips for writing college admissions essays . How you upload your college application essay depends on whether you will be cutting and pasting your essay into a text box in an online application form or attaching a formatted document.

Save and upload your college essay in the proper format

Check the application instructions if you’re not sure what you need to do. Currently, the Common Application requires you to copy and paste your essay into a text box.

There are three main formats when it comes to submitting your college essay or personal statement:

If submitting your application essay in a text box

For the Common Application, there is no need to attach a document since there is a dedicated input field. You still want to write your essay in a word processor or Google doc. Just make sure once you copy-paste your essay into the text box that your line breaks (paragraphs), indents, and formatting is retained.

- Formatting like bold , underline, and italics are often lost when copy-pasting into a text box.

- Double-check that you are under the word limit. Word counts may be different within the text box .

- Make sure that paragraphs and spacing are maintained; text input fields often undo indents and double-spacing .

- If possible, make sure the font is standardized. Text input boxes usually allow just one font .

If submitting your application essay as a document

When attaching a document, you must do more than just double-check the format of your admissions essay. You need to be proactive and make sure the structure is logical and will be attractive to readers.

Microsoft Word (.DOC) format

If you are submitting your application essay as a file upload, then you will likely submit a .doc or .docx file. The downside is that MS Word files are editable, and there are sometimes conflicts between different MS Word versions (2010 vs 2016 vs Office365). The upside is that Word can be opened by almost any text program.

This is a safe choice if maintaining the visual elements of your essay is important. Saving your essay as a PDF prevents any formatting issues that come with Microsoft Word, since older versions are sometimes incompatible with the newer formatting.

Although PDF viewing programs are commonly available, many older readers and Internet users (who will be your admissions officers) may not be ready to view PDFs.

- Use 1-inch margins . This is the default setting for Microsoft Word. However, students from Asia using programs like Hangul Word Processor will need to double-check.

- Use a standard serif font. These include Times New Roman, Courier, and Garamond. A serif font adds professionalism to your essay.

- Use standard 12-font size.

- Use 1.5- or double-spacing. Your application essay should be readable. Double spaces are not an issue as the essay should already fit on one page.

- Add a Header with your First Name, Last Name, university, and other required information.

- Clearly separate your paragraphs. By default, just press ‘ENTER’ twice.

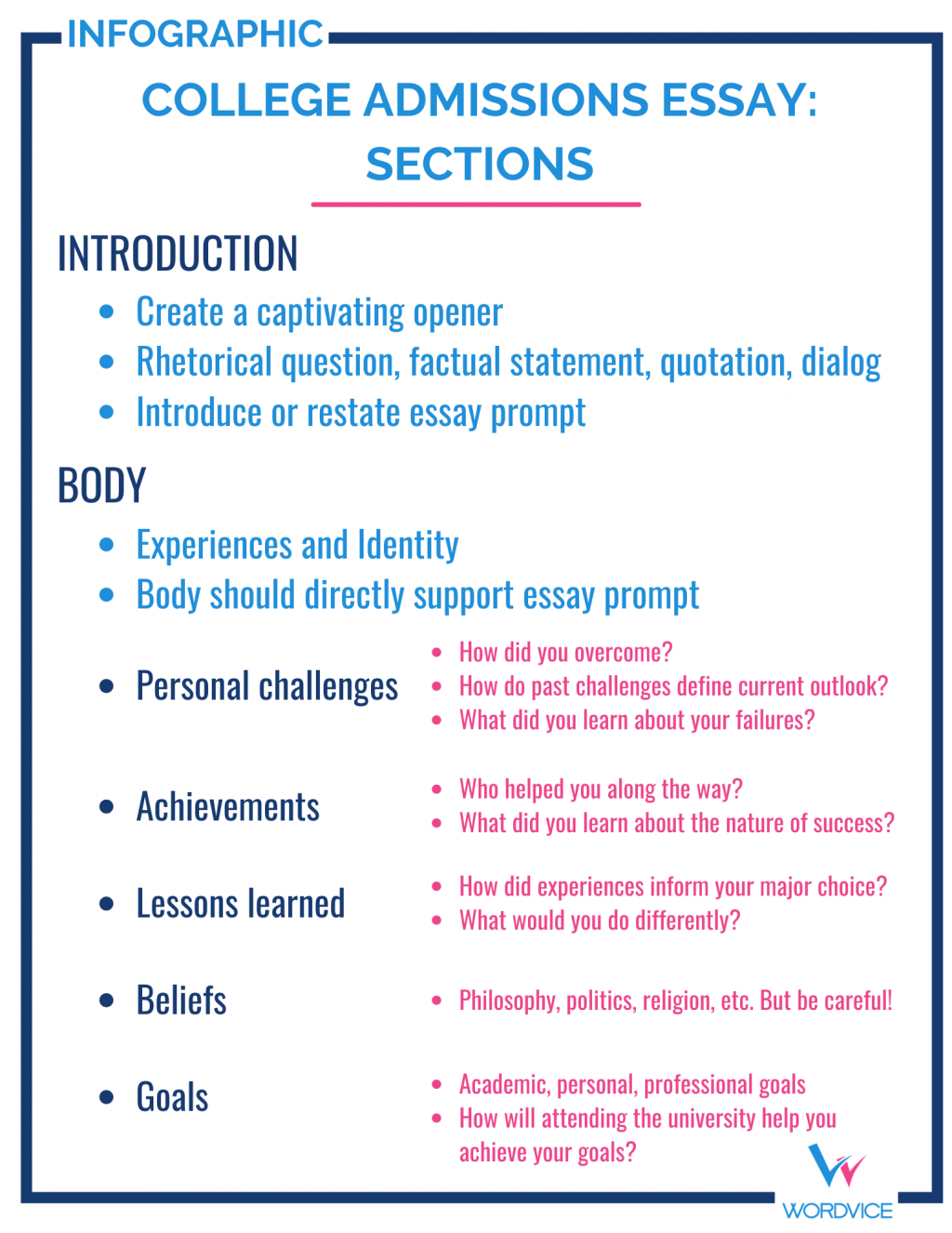

Sections Of A College Admissions Essay

University admissions protocols usually allow you to choose the format and style of your writing. Despite this, the general format of “Introduction-Body-Conclusion” is the most common structure. This is a common format you can use and adjust to your specific writing style.

College Application Essay Introduction

Typically, your first paragraph should introduce you or the topic that you will discuss. You must have a killer opener if you want the admissions committees to pay attention.

Essays that use rhetorical tools, factual statements, dialog, etc. are encouraged. There is room to be creative since many application essays specifically focus on past learning experiences.

College Application Essay Body

Clearly answering the essay prompt is the most important part of the essay body. Keep reading over the prompt and making sure everything in the body supports it.

Since personal statement essays are designed to show you are as a person and student, the essay body is also where you talk about your experiences and identity.

Make sure you include the following life experiences and how they relate to the essay prompt. Be sure to double-check that they relate back to the essay prompt. A college admissions essay is NOT an autobiography:

Personal challenges

- How did you overcome them?

- How or how much do past challenges define your current outlook or worldview?

- What did you learn about yourself when you failed?

Personal achievements and successes

- What people helped you along the way?

- What did you learn about the nature of success

Lessons learned

- In general, did your experiences inform your choice of university or major?

Personal beliefs

- Politics, philosophy, and religion may be included here, but be careful when discussing sensitive personal or political topics.

- Academic goals

- Personal goals

- Professional goals

- How will attending the university help you achieve these goals?

College Application Essay Conclusion

The conclusion section is a call to action directly aimed at the admissions officers. You must demonstrate why you are a great fit for the university, which means you should refer to specific programs, majors, or professors that guided or inspired you.

In this “why this school” part of the essay, you can also explain why the university is a great fit for your goals. Be straightforward and truthful, but express your interest in the school boldly.

College Application Essay Format Examples

Here are several formatting examples of successful college admission essays, along with comments from the essay editor.

Note: Actual sample essays edited by Wordvice professional editors . Personal info has been redacted for privacy. This is not a college essay template.

College Admission Essay Example 1

This essay asks the student to write about how normal life experiences can have huge effects on personal growth:

Common App Essay Prompt: Thoughtful Rides

The Florida turnpike is a very redundant and plain expressway; we do not have the scenic luxury of mountains, forests, or even deserts stretching endlessly into the distance. Instead, we are blessed with repetitive fields of grazing cows and countless billboards advertising local businesses. I have been subjected to these monotonous views three times a week, driving two hours every other day to Sunrise and back to my house in Miami, Florida—all to practice for my competitive soccer team in hopes of receiving a scholarship to play soccer at the next level.

The Introduction sets up a clear, visceral memory and communicates a key extracurricular activity.

When I first began these mini road trips, I would jam out to my country playlist and sing along with my favorite artists, and the trek would seem relatively short. However, after listening to “Beautiful Crazy” by Luke Combs for the 48th time in a week, the song became as repetitive as the landscape I was driving through. Changing genres did not help much either; everything I played seemed to morph into the same brain-numbing sound. Eventually, I decided to do what many peers in my generation fail to do: turn off the distractions, enjoy the silence, and immerse myself in my own thoughts. In the end, this seemingly simple decision led to a lot of personal growth and tranquility in my life.

The first part of the Body connects the student’s past experience with the essay prompt: personal growth and challenging assumptions.

Although I did not fully realize it at the time, these rides were the perfect opportunity to reflect on myself and the people around me. I quickly began noticing the different personalities surrounding me in the flow of traffic, and this simple act of noticing reminded me that I was not the only human on this planet that mattered. I was just as unimportant as the woman sitting in the car next to mine. Conversely, I also came to appreciate how a gesture as simple as letting another driver merge into your lane can impact a stranger’s day. Maybe the other driver is late for a work interview or rushing to the hospital because their newborn is running a high fever and by allowing them to advance in the row of cars, you made their day just a little less stressful. I realized that if I could improve someone else’s day from my car, I could definitely be a kinder person and take other people’s situations into consideration—because you never know if someone is having one of the worst days of their lives and their interaction with you could provide the motivation they need to keep going on .

This part uses two examples to support the writer’s answer to the essay prompt. It ends the paragraph with a clear statement.

Realizing I was not the only being in the universe that mattered was not the only insight I attained during these drives. Over and over, I asked myself why I had chosen to change soccer clubs, leaving Pinecrest, the team I had played on for 8 years with my best friends and that was only a 10-minute drive from my house, to play for a completely unfamiliar team that required significantly more travel. Eventually, I came to understand that I truly enjoy challenging myself and pushing past complacency . One of my main goals in life is to play and experience college soccer—that, and to eventually pursue a career as a doctor. Ultimately, leaving my comfort zone in Pinecrest, where mediocrity was celebrated, to join a team in Sunrise, where championships were expected and college offers were abundant, was a very positive decision in my life.

This part clearly tells how the experience shaped the writer as a person. The student’s personality can be directly attributed to this memory. It also importantly states personal and academic goals.

Even if I do not end up playing college soccer, I know now that I will never back down from any challenge in my life; I am committed to pushing myself past my comfort zone. These car rides have given me insight into how strong I truly am and how much impact I can have on other people’s lives.

The Conclusion restates the overall lesson learned.

College Admission Essay Example 2

The next essay asks the reader to use leadership roles or extracurricular activities and describe the experience, contribution, and what the student learned about themselves.

As I release the air from the blood-pressure monitor’s valve, I carefully track the gauge, listening for the faint “lub-dub” of Winnie’s heart. Checking off the “hypertensive” box on his medical chart when reading 150/95, I then escort Winnie to the blood sugar station. This was the typical procedure of a volunteer at the UConn Migrant Farm Worker Clinic. Our traveling medical clinic operated at night, visiting various Connecticut farms to provide healthcare for migrant workers. Filling out charts, taking blood pressure, and recording BMI were all standard procedures, but the relationships I built with farmers such as Winnie impacted me the most.

This Introduction is very impactful. It highlights the student’s professional expertise as a healthcare worker and her impact on marginalized communities. It also is written in the present tense to add impact.

While the clinic was canceled this year due to COVID-19, I still wanted to do something for them. During a PPE-drive meeting this July, Winnie recounted his family history. I noticed his eyebrows furrow with anxiety as he spoke about his family’s safety in Tierra Blanca, Mexico. I realized that Winnie lacked substantial information about his hometown, and fear-mongering headlines did nothing to assuage his fears. After days of searching, I discovered that his hometown, Guanajuato, reported fewer cases of COVID-19 in comparison with surrounding towns. I then created a color-coded map of his town, showing rates across the different districts. Winnie’s eyes softened, marveling at the map I made for him this August. I didn’t need to explain what he saw: Guanajuato, his home state, was pale yellow, the color I chose to mark the lowest level of cases. By making this map, I didn’t intend to give him new hope; I wanted to show him where hope was.

The student continues to tell the powerful story of one of her patients. This humbles and empowers the student, motivating her in the next paragraph.

This interaction fueled my commitment to search for hope in my journey of becoming a public health official. Working in public health policy, I hope to tackle complex world problems, such as economic and social barriers to healthcare and find creative methods of improving outcomes in queer and Latinx communities. I want to study the present and potential future intervention strategies in minority communities for addressing language barriers to information including language on posters and gendered language, and for instituting social and support services for community youth. These stepping stones will hopefully prepare me for conducting professional research for the Medical Organization for Latino Advancement. I aspire to be an active proponent of healthcare access and equity for marginalized groups, including queer communities. I first learned about the importance of recognizing minority identities in healthcare through my bisexual sister, Sophie, and her nonbinary friend, Gilligan. During discussions with her friends, I realized the importance of validating diverse gender expressions in all facets of my life.

Here, the past experience is directly connected to future academic and professional goals, which themselves are motivated by a desire to increase access among communities as well as personal family experiences. This is a strong case for why personal identity is so important.

My experiences with Winnie and my sister have empowered me to be creative, thoughtful, and brave while challenging the assumptions currently embedded in the “visual vocabulary” of both the art and science fields. I envision myself deconstructing hegemonic ideas of masculinity and femininity and surmounting the limitations of traditional perceptions of male and female bodies as it relates to existing healthcare practices. Through these subtle changes, I aim to make a large impact.

The Conclusion positions the student as an impactful leader and visionary. This is a powerful case for the admissions board to consider.

If you want to read more college admissions essay examples, check out our articles about successful college personal statements and the 2021-2022 Common App prompts and example essays .

Wordvice offers a full suite of proofreading and editing services . If you are a student applying to college and are having trouble with the best college admissions essay format, check out our application essay editing services (including personal statement editing ) and find out how much online proofreading costs .

Finally, don’t forget to receive common app essay editing and professional admissions editing for any other admissions documents for college, university, and post-doctoral programs.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Format and Structure Your College Essay

←What Is a College Application Theme and How Do You Come Up With One?

How to Write a Personal Statement That Wows Colleges→

Does your Common App essay actually stand out?

Your essay can be the difference between an acceptance and rejection — it allows you to stand out from the rest of applicants with similar profiles. Get a free peer review or review other students’ essays right now to understand the strength of your essay.

Submit or Review an Essay — for free!

College essays are an entirely new type of writing for high school seniors. For that reason, many students are confused about proper formatting and essay structure. Should you double-space or single-space? Do you need a title? What kind of narrative style is best-suited for your topic?

In this post, we’ll be going over proper college essay format, traditional and unconventional essay structures (plus sample essays!), and which structure might work best for you.

General College Essay Formatting Guidelines

How you format your essay will depend on whether you’re submitting in a text box, or attaching a document. We’ll go over the different best practices for both, but regardless of how you’re submitting, here are some general formatting tips:

- There’s no need for a title; it takes up unnecessary space and eats into your word count

- Stay within the word count as much as possible (+/- 10% of the upper limit). For further discussion on college essay length, see our post How Long Should Your College Essay Be?

- Indent or double space to separate paragraphs clearly

If you’re submitting in a text box:

- Avoid italics and bold, since formatting often doesn’t transfer over in text boxes

- Be careful with essays meant to be a certain shape (like a balloon); text boxes will likely not respect that formatting. Beyond that, this technique can also seem gimmicky, so proceed with caution

- Make sure that paragraphs are clearly separated, as text boxes can also undo indents and double spacing

If you’re attaching a document:

- Use a standard font and size like Times New Roman, 12 point

- Make your lines 1.5-spaced or double-spaced

- Use 1-inch margins

- Save as a PDF since it can’t be edited. This also prevents any formatting issues that come with Microsoft Word, since older versions are sometimes incompatible with the newer formatting

- Number each page with your last name in the header or footer (like “Smith 1”)

- Pay extra attention to any word limits, as you won’t be cut off automatically, unlike with most text boxes

Conventional College Essay Structures

Now that we’ve gone over the logistical aspects of your essay, let’s talk about how you should structure your writing. There are three traditional college essay structures. They are:

- In-the-moment narrative

- Narrative told over an extended period of time

- Series of anecdotes, or montage

Let’s go over what each one is exactly, and take a look at some real essays using these structures.

1. In-the-moment narrative

This is where you tell the story one moment at a time, sharing the events as they occur. In the moment narrative is a powerful essay format, as your reader experiences the events, your thoughts, and your emotions with you . This structure is ideal for a specific experience involving extensive internal dialogue, emotions, and reflections.

Here’s an example:

The morning of the Model United Nation conference, I walked into Committee feeling confident about my research. We were simulating the Nuremberg Trials – a series of post-World War II proceedings for war crimes – and my portfolio was of the Soviet Judge Major General Iona Nikitchenko. Until that day, the infamous Nazi regime had only been a chapter in my history textbook; however, the conference’s unveiling of each defendant’s crimes brought those horrors to life. The previous night, I had organized my research, proofread my position paper and gone over Judge Nikitchenko’s pertinent statements. I aimed to find the perfect balance between his stance and my own.

As I walked into committee anticipating a battle of wits, my director abruptly called out to me. “I’m afraid we’ve received a late confirmation from another delegate who will be representing Judge Nikitchenko. You, on the other hand, are now the defense attorney, Otto Stahmer.” Everyone around me buzzed around the room in excitement, coordinating with their allies and developing strategies against their enemies, oblivious to the bomb that had just dropped on me. I felt frozen in my tracks, and it seemed that only rage against the careless delegate who had confirmed her presence so late could pull me out of my trance. After having spent a month painstakingly crafting my verdicts and gathering evidence against the Nazis, I now needed to reverse my stance only three hours before the first session.

Gradually, anger gave way to utter panic. My research was fundamental to my performance, and without it, I knew I could add little to the Trials. But confident in my ability, my director optimistically recommended constructing an impromptu defense. Nervously, I began my research anew. Despite feeling hopeless, as I read through the prosecution’s arguments, I uncovered substantial loopholes. I noticed a lack of conclusive evidence against the defendants and certain inconsistencies in testimonies. My discovery energized me, inspiring me to revisit the historical overview in my conference “Background Guide” and to search the web for other relevant articles. Some Nazi prisoners had been treated as “guilty” before their court dates. While I had brushed this information under the carpet while developing my position as a judge, it now became the focus of my defense. I began scratching out a new argument, centered on the premise that the allied countries had violated the fundamental rule that, a defendant was “not guilty” until proven otherwise.

At the end of the three hours, I felt better prepared. The first session began, and with bravado, I raised my placard to speak. Microphone in hand, I turned to face my audience. “Greetings delegates. I, Otto Stahmer would like to…….” I suddenly blanked. Utter dread permeated my body as I tried to recall my thoughts in vain. “Defence Attorney, Stahmer we’ll come back to you,” my Committee Director broke the silence as I tottered back to my seat, flushed with embarrassment. Despite my shame, I was undeterred. I needed to vindicate my director’s faith in me. I pulled out my notes, refocused, and began outlining my arguments in a more clear and direct manner. Thereafter, I spoke articulately, confidently putting forth my points. I was overjoyed when Secretariat members congratulated me on my fine performance.

Going into the conference, I believed that preparation was the key to success. I wouldn’t say I disagree with that statement now, but I believe adaptability is equally important. My ability to problem-solve in the face of an unforeseen challenge proved advantageous in the art of diplomacy. Not only did this experience transform me into a confident and eloquent delegate at that conference, but it also helped me become a more flexible and creative thinker in a variety of other capacities. Now that I know I can adapt under pressure, I look forward to engaging in activities that will push me to be even quicker on my feet.

This essay is an excellent example of in-the-moment narration. The student openly shares their internal state with us — we feel their anger and panic upon the reversal of roles. We empathize with their emotions of “utter dread” and embarrassment when they’re unable to speak.

For in-the-moment essays, overloading on descriptions is a common mistake students make. This writer provides just the right amount of background and details to help us understand the situation, however, and balances out the actual event with reflection on the significance of this experience.

One main area of improvement is that the writer sometimes makes explicit statements that could be better illustrated through their thoughts, actions, and feelings. For instance, they say they “spoke articulately” after recovering from their initial inability to speak, and they also claim that adaptability has helped them in other situations. This is not as engaging as actual examples that convey the same meaning. Still, this essay overall is a strong example of in-the-moment narration, and gives us a relatable look into the writer’s life and personality.

2. Narrative told over an extended period of time

In this essay structure, you share a story that takes place across several different experiences. This narrative style is well-suited for any story arc with multiple parts. If you want to highlight your development over time, you might consider this structure.

When I was younger, I was adamant that no two foods on my plate touch. As a result, I often used a second plate to prevent such an atrocity. In many ways, I learned to separate different things this way from my older brothers, Nate and Rob. Growing up, I idolized both of them. Nate was a performer, and I insisted on arriving early to his shows to secure front row seats, refusing to budge during intermission for fear of missing anything. Rob was a three-sport athlete, and I attended his games religiously, waving worn-out foam cougar paws and cheering until my voice was hoarse. My brothers were my role models. However, while each was talented, neither was interested in the other’s passion. To me, they represented two contrasting ideals of what I could become: artist or athlete. I believed I had to choose.

And for a long time, I chose athlete. I played soccer, basketball, and lacrosse and viewed myself exclusively as an athlete, believing the arts were not for me. I conveniently overlooked that since the age of five, I had been composing stories for my family for Christmas, gifts that were as much for me as them, as I loved writing. So when in tenth grade, I had the option of taking a creative writing class, I was faced with a question: could I be an athlete and a writer? After much debate, I enrolled in the class, feeling both apprehensive and excited. When I arrived on the first day of school, my teacher, Ms. Jenkins, asked us to write down our expectations for the class. After a few minutes, eraser shavings stubbornly sunbathing on my now-smudged paper, I finally wrote, “I do not expect to become a published writer from this class. I just want this to be a place where I can write freely.”

Although the purpose of the class never changed for me, on the third “submission day,” – our time to submit writing to upcoming contests and literary magazines – I faced a predicament. For the first two submission days, I had passed the time editing earlier pieces, eventually (pretty quickly) resorting to screen snake when hopelessness made the words look like hieroglyphics. I must not have been as subtle as I thought, as on the third of these days, Ms. Jenkins approached me. After shifting from excuse to excuse as to why I did not submit my writing, I finally recognized the real reason I had withheld my work: I was scared. I did not want to be different, and I did not want to challenge not only others’ perceptions of me, but also my own. I yielded to Ms. Jenkin’s pleas and sent one of my pieces to an upcoming contest.

By the time the letter came, I had already forgotten about the contest. When the flimsy white envelope arrived in the mail, I was shocked and ecstatic to learn that I had received 2nd place in a nationwide writing competition. The next morning, however, I discovered Ms. Jenkins would make an announcement to the whole school exposing me as a poet. I decided to own this identity and embrace my friends’ jokes and playful digs, and over time, they have learned to accept and respect this part of me. I have since seen more boys at my school identifying themselves as writers or artists.

I no longer see myself as an athlete and a poet independently, but rather I see these two aspects forming a single inseparable identity – me. Despite their apparent differences, these two disciplines are quite similar, as each requires creativity and devotion. I am still a poet when I am lacing up my cleats for soccer practice and still an athlete when I am building metaphors in the back of my mind – and I have realized ice cream and gummy bears taste pretty good together.

The timeline of this essay spans from the writer’s childhood all the way to sophomore year, but we only see key moments along this journey. First, we get context for why the writer thought he had to choose one identity: his older brothers had very distinct interests. Then, we learn about the student’s 10th grade creative writing class, writing contest, and results of the contest. Finally, the essay covers the writers’ embarrassment of his identity as a poet, to gradual acceptance and pride in that identity.

This essay is a great example of a narrative told over an extended period of time. It’s highly personal and reflective, as the piece shares the writer’s conflicting feelings, and takes care to get to the root of those feelings. Furthermore, the overarching story is that of a personal transformation and development, so it’s well-suited to this essay structure.

3. Series of anecdotes, or montage

This essay structure allows you to focus on the most important experiences of a single storyline, or it lets you feature multiple (not necessarily related) stories that highlight your personality. Montage is a structure where you piece together separate scenes to form a whole story. This technique is most commonly associated with film. Just envision your favorite movie—it likely is a montage of various scenes that may not even be chronological.

Night had robbed the academy of its daytime colors, yet there was comfort in the dim lights that cast shadows of our advances against the bare studio walls. Silhouettes of roundhouse kicks, spin crescent kicks, uppercuts and the occasional butterfly kick danced while we sparred. She approached me, eyes narrowed with the trace of a smirk challenging me. “Ready spar!” Her arm began an upward trajectory targeting my shoulder, a common first move. I sidestepped — only to almost collide with another flying fist. Pivoting my right foot, I snapped my left leg, aiming my heel at her midsection. The center judge raised one finger.

There was no time to celebrate, not in the traditional sense at least. Master Pollard gave a brief command greeted with a unanimous “Yes, sir” and the thud of 20 hands dropping-down-and-giving-him-30, while the “winners” celebrated their victory with laps as usual.

Three years ago, seven-thirty in the evening meant I was a warrior. It meant standing up straighter, pushing a little harder, “Yes, sir” and “Yes, ma’am”, celebrating birthdays by breaking boards, never pointing your toes, and familiarity. Three years later, seven-thirty in the morning meant I was nervous.

The room is uncomfortably large. The sprung floor soaks up the checkerboard of sunlight piercing through the colonial windows. The mirrored walls further illuminate the studio and I feel the light scrutinizing my sorry attempts at a pas de bourrée , while capturing the organic fluidity of the dancers around me. “ Chassé en croix, grand battement, pique, pirouette.” I follow the graceful limbs of the woman in front of me, her legs floating ribbons, as she executes what seems to be a perfect ronds de jambes. Each movement remains a negotiation. With admirable patience, Ms. Tan casts me a sympathetic glance.

There is no time to wallow in the misery that is my right foot. Taekwondo calls for dorsiflexion; pointed toes are synonymous with broken toes. My thoughts drag me into a flashback of the usual response to this painful mistake: “You might as well grab a tutu and head to the ballet studio next door.” Well, here I am Master Pollard, unfortunately still following your orders to never point my toes, but no longer feeling the satisfaction that comes with being a third degree black belt with 5 years of experience quite literally under her belt. It’s like being a white belt again — just in a leotard and ballet slippers.

But the appetite for new beginnings that brought me here doesn’t falter. It is only reinforced by the classical rendition of “Dancing Queen” that floods the room and the ghost of familiarity that reassures me that this new beginning does not and will not erase the past. After years spent at the top, it’s hard to start over. But surrendering what you are only leads you to what you may become. In Taekwondo, we started each class reciting the tenets: honor, courtesy, integrity, perseverance, self-control, courage, humility, and knowledge, and I have never felt that I embodied those traits more so than when I started ballet.

The thing about change is that it eventually stops making things so different. After nine different schools, four different countries, three different continents, fluency in Tamil, Norwegian, and English, there are more blurred lines than there are clear fragments. My life has not been a tactfully executed, gold medal-worthy Taekwondo form with each movement defined, nor has it been a series of frappés performed by a prima ballerina with each extension identical and precise, but thankfully it has been like the dynamics of a spinning back kick, fluid, and like my chances of landing a pirouette, unpredictable.

This essay takes a few different anecdotes and weaves them into a coherent narrative about the writer’s penchant for novel experiences. We’re plunged into her universe, in the middle of her Taekwondo spar, three years before the present day. She then transitions into a scene in a ballet studio, present day. By switching from past tense to present tense, the writer clearly demarcates this shift in time.

The parallel use of the spoken phrase “Point” in the essay ties these two experiences together. The writer also employs a flashback to Master Pollard’s remark about “grabbing a tutu” and her habit of dorsiflexing her toes, which further cements the connection between these anecdotes.

While some of the descriptions are a little wordy, the piece is well-executed overall, and is a stellar example of the montage structure. The two anecdotes are seamlessly intertwined, and they both clearly illustrate the student’s determination, dedication, reflectiveness, and adaptability. The writer also concludes the essay with a larger reflection on her life, many moves, and multiple languages.

Unconventional College Essay Structures

Unconventional essay structures are any that don’t fit into the categories above. These tend to be higher risk, as it’s easier to turn off the admissions officer, but they’re also higher reward if executed correctly.

There are endless possibilities for unconventional structures, but most fall under one of two categories:

1. Playing with essay format

Instead of choosing a traditional narrative format, you might take a more creative route to showcase your interests, writing your essay:

- As a movie script

- With a creative visual format (such as creating a visual pattern with the spaces between your sentences forming a picture)

- As a two-sided Lincoln-Douglas debate

- As a legal brief

- Using song lyrics

2. Linguistic techniques

You could also play with the actual language and sentence structure of your essay, writing it:

- In iambic pentameter

- Partially in your mother tongue

- In code or a programming language

These linguistic techniques are often hybrid, where you write some of the essay with the linguistic variation, then write more of an explanation in English.

Under no circumstances should you feel pressured to use an unconventional structure. Trying to force something unconventional will only hurt your chances. That being said, if a creative structure comes naturally to you, suits your personality, and works with the content of your essay — go for that structure!

←What is a College Application Theme and How Do You Come Up With One?

Want help with your college essays to improve your admissions chances? Sign up for your free CollegeVine account and get access to our essay guides and courses. You can also get your essay peer-reviewed and improve your own writing skills by reviewing other students’ essays.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Our Services

College Admissions Counseling

UK University Admissions Counseling

EU University Admissions Counseling

College Athletic Recruitment

Crimson Rise: College Prep for Middle Schoolers

Indigo Research: Online Research Opportunities for High Schoolers

Delta Institute: Work Experience Programs For High Schoolers

Graduate School Admissions Counseling

Private Boarding & Day School Admissions

Essay Review

Financial Aid & Merit Scholarships

Our Leaders and Counselors

Our Student Success

Crimson Student Alumni

Our Results

Our Reviews

Our Scholarships

Careers at Crimson

University Profiles

US College Admissions Calculator

GPA Calculator

Practice Standardized Tests

SAT Practice Test

ACT Practice Tests

Personal Essay Topic Generator

eBooks and Infographics

Crimson YouTube Channel

Summer Apply - Best Summer Programs

Top of the Class Podcast

ACCEPTED! Book by Jamie Beaton

Crimson Global Academy

+1 (646) 419-3178

Go back to all articles

How To Format & Structure Your College Application Essay

/f/64062/1200x630/0e6a407858/college-essay-format.jpg)

Part I: What Is a College Essay?

Part II: College Essay Formats

Choosing the Best Format

Part III: Structure

Part IV: Revising With a Rubric

Part V: Nuts & Bolts Formatting

This blog post provides a comprehensive guide to college essay formats and structures, covering the purpose of the essay in admissions, the differences between personal narratives and personal essays, and a variety of both common and creative essay structures. It also includes a concise rubric for evaluating essays and practical tips on formatting and submitting your final draft. Whether you’re just starting your essay or refining your final version, your essay is a crucial application component. The principles and insights in this post will position you to write the kind of essays submitted by top applicants.

Crafting a compelling college essay is a critical part of the admissions process, but it can also be one of the most daunting. Understanding the different formats and structures available can help you tell your story in a way that resonates with admissions officers.

Whether you're writing a personal narrative , personal essay , or a reflective essay , this guide will walk you through the key elements to consider, offering practical tips and creative strategies to help your essay stand out.

First, it's important to understand that the essays you write in high school differ from what you have to write in your college application essays . Whether you’re writing the Common App Essay , Supplemental Essays, or UCAS Personal Statement , it's crucial that you prepare ahead of time to do your absolute best. Read ahead for guidelines on how to format and structure a college application essay and what mistakes to avoid.

Interested in learning more? Attend one of our free events

How to get into top non-ivies like stanford, duke, mit, & more.

Friday, November 8, 2024 1:00 AM CUT

Learn from a Former Duke Admissions Officer about what goes into a successful application for the most selective colleges in the country!

REGISTER NOW

Part I. What Is a College Essay?

A college essay introduces you to your prospective college or university.

It’s common for these essays to have a prescribed length between 200 and 600 words .

The college essay is a pillar of most applications because it offers a glimpse into who you are as a person and helps admissions officers gauge your potential fit in a college community.

Your choice of format and structure will also be guided by the specific prompt you’re writing to and how you approach the prompt, based on your own unique personal circumstances and the college context.

The Format Is Not Familiar to Many Students; But It's Not Counter-intuitive Either

Many students have little experience or formal teaching for this kind of writing format, and have had little opportunity to experiment with it and get feedback.

Shifting gears away from what many US students learn about writing a 5-Paragraph Essay or any similar form of expository essay, let's put the college essay writing format into a more familiar perspective.

Imagine you’ve decided to (or been asked to) write a brief memoir of your life.

Or, imagine you’re asked to develop and write a thoughtful personal reflection about a favorite activity, book, or influential event in your life.

Do these examples make writing a college essay feel a bit more approachable? I hope so!

We all have a story to tell that can help strangers know us better.

We all have a capacity for sharing our reflections on formative and memorable personal experiences or big life questions or concepts.

And when we do that, we’re sharing in much the same way we share in a college essay.

Navigating College Essays Prompts

For some students, the prompt can be both helpful and intimidating:

- It narrows the focus of your essay, providing some clear direction, but also setting an expectation about what the reader wants to learn about you.

- It often leaves you lots of latitude for interpreting it how you want to.

- It leaves you to choose, develop, and share the most relevant personal thoughts and experiences.

- It can offer quite a bit of latitude for how you format and structure the final essay.

Here is an example of an actual college essay prompt from Yale :

Reflect on your membership in a community to which you feel connected. Why is this community meaningful to you? You may define community however you like.

Prompts Typically Probe Your Personal Experiences and Thoughts

This kind of essay isn’t about information and facts, or your resume! You're going to need to write about yourself, through the lens of your own feelings, thoughts, perceptions, and experiences. This can involve some uncomfortable honesty, candor, and vulnerability, and a level of subjectivity that's foreign to most academic writing you're used to!

To drive this point home, note that the words you/your appear five times in the prompt from Yale!

Also, the prompt even tells you that “community” can be defined however you like . That's nice freedom... BUT, you're left with the challenge of making a coherent essay out of your thoughts and reflections.

Decoding College Essay Prompts

While the general purpose of a college essay is to introduce yourself to admissions officers or help school leaders gauge your "fit" with their school, you’ll want to decode the essay prompt for more nuanced clarity on the purpose of your essay.

For most college essay prompts, “decoding” is very straightforward, but it’s still important:

- Helping you think about the purpose of your essay in more specific terms

- Guiding your editorial choices, in terms of what you want to share, highlight, and emphasize

Use the specific admissions context to guide decoding.

Using the example above, it’s clear Yale wants to get a sense of how you’ll thrive in a very social learning environment: from interactions with a study group, to collaborating in a school club, orchestra, or athletic team, or thriving in the the larger campus community…

One can go a step further, putting the prompt (and the essay you’ll write) into a larger context . Yale no doubt understands its role in preparing students for future leadership. High-level, innovative leadership requires a well-honed ability to navigate complex community and public/private interactions, collaborations, and even rivalries.

In the end, your essay will focus on what’s real and authentic for you personally, but decoding the prompt in its larger admissions context can help you decide what content is most relevant.

Key Takeaways for Writing to College Essay Prompts:

- Understand what prompts are: A prompt provides a question or statement that highlights something the admissions officers want you to reveal about yourself, but also allows for a fair amount of subjectivity and personal voice, style, and creativity.

- Decode the prompt and brainstorm relevant content: Think about the underlying purpose and context for the prompt and essay — make sure the content is responsive, but also personalized, being genuine and authentic.

- Leverage the prompt as a catalyst to say something important, insightful, and compelling about your personality, character, and/or aspirations, values, and commitments.

What’s the Difference Between a College Essay and a Personal Statement ?

Good question!

In some contexts, or when used loosely, the two terms may periodically be used interchangeably.

But in most contexts, personal statements are different from college essays , even if both are used for admissions.

1. Personal Statement

- A personal statement is common when you apply for a scholarship, or a school wants you to clarify your interest and motivation for applying to a specific major. And personal statements are prevalent in the UK admissions process.

- It tends to be more factual and less personal than a college essay (a bit more like a resume).

If you use the UCAS platform to apply to a UK school, you’ll be asked to write a clear and concise “personal statement” under 4,000 characters that includes the following type of personal information:

- Personal skills and achievements

- Work experience and future plans

- Positions of responsibility held, or have held, both in and out of school

- Details of jobs, placements, work experience, or voluntary work, particularly if it's relevant to the course

- How the applicant has prepared for their chosen area of study

- Why they enjoy and are good at the subject

- A good level of academic terminology and experience

As you can see, a personal statement is autobiographical but in a more matter of fact way , making it less subjective and less intimate in terms of sharing about identity, nuanced thoughts, and formative personal experiences.

A personal statement requires time and effort, but the task is more straightforward, based on resume-type information, qualifications, and academic or professional goals.

A college essay has a prescribed focus, but it’s also asking you to share values, reflections, and ideas, and speak to your personality, attributes, and aspirations. This makes your approach more open-ended, and it’s a big departure from more practical forms of business communication or academic writing.

Part II: The Format of a College Essay

In this section will delve more deeply into the general format of a college essay, with a closer look at the two most relevant formats for this kind of writing task:

- Personal Essay & Reflective Essay

- Personal Narrative

A college essay will typically have the overall format (structure, voice, and perspective) of a personal essay/reflective essay OR personal narrative .

Features of a Personal Essay Format

A personal essay is a reflective piece of writing that explores a specific theme or topic from the author's life. Rather than following a story arc, a personal essay delves into events, influences, personality traits, or beliefs and reflections related to a larger personal theme.

Features of a Personal or Reflective Essay Format:

- Topical Structure : Organized around a central theme or topic, rather than following a chronological narrative. The essay often explores different facets of the theme through various examples or reflections.

- Analytical Approach : Focuses on analyzing and reflecting on personal experiences, thoughts, or ideas. The writing is introspective and seeks to draw broader insights or conclusions from personal events.

- Logical Flow : Maintains a clear, logical progression of ideas, often following the structure of an introduction, body, and conclusion. Each paragraph or section builds on the previous one to support the essay's main theme or argument.

- Reflective Tone : Emphasizes the writer's internal thought process and personal growth. The tone is often contemplative, exploring how specific experiences or ideas have shaped the writer's perspective.

- Less Dialogue, More Reflection : Unlike a narrative, a personal essay rarely includes dialogue or detailed storytelling. Instead, it focuses on the writer's reflections, insights, and the connections they make between their experiences and the essay's theme.

- Unified Theme : The essay revolves around a single, cohesive theme or message. All examples and reflections are tied back to this central idea, creating a sense of unity and purpose throughout the essay.

- Purposeful Conclusion : Ends with a thoughtful conclusion that ties together the reflections and insights, often leaving the reader with a lasting impression or a broader understanding of the theme.

A reflective essay format is similar to a personal essay format, but making a distinction may be helpful.

Some college essay prompts will ask students to share their introspective views of a big idea or concept. This aligns with a reflective essay format , for most circumstances.

With less focus on life events and experiences than a personal essay, a reflective essay focuses on a writer's inner thoughts : this format is ideally suited for sharing thoughts and ideas, revealing how you make mental connections between influences, experiences, and thoughts, and spotlighting evolving ideas and perspectives that shape your identity or academic interests.

Features of a Personal Narrative Format

A personal narrative is a story about a specific experience or event from the author's life, focusing on a particular moment or series of events and the emotions and lessons associated with it.

Features of a Personal Narrative Format:

- Storytelling Elements : Utilizes writing techniques and elements commonly found in novels and short stories, such as character development, plot, and setting.

- Descriptive Details : Includes vivid descriptions that evoke the setting, characters, and atmosphere, helping the reader visualize and connect with the story.

- Dialogue and Inner Thoughts : May incorporate dialogue and inner thoughts to reveal character emotions, intentions, and relationships, making the narrative more dynamic and engaging.

- Chronological Order : Often unfolds in chronological order, recounting events as they happened. This can be over an extended period or within a single moment, depending on the story's focus.

- Sensory Details : Enriches the narrative with sensory details — sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures — that immerse the reader in the experience.

- Suspense and Conflict : Includes elements of suspense, conflict, or intrigue that engage the reader and drive the narrative forward, often creating anticipation for the reader about a resolution or revelation.

- Focused on a Specific Event or Experience : Centers around a particular event or moment in the author’s life, exploring the emotions, lessons, and impacts associated with it.

Depending on the prompt and the content and themes that you most want to recount and share, a college essay may use one of the formats above exclusively, but oftentimes a college essay will be made more effective by integrating features from one or more of these college essay formats.

A Note on the Unconventional “Third-Person” Personal Essay

There can always be creative exceptions to what’s most common…

One such example is using the third-person voice instead of the first-person voice.

While personal essays are typically written in the first person, some applicants choose to take an unconventional approach by writing about themselves from an external perspective.

This method involves observing oneself as if under a microscope, adopting a tone that is intentionally dispassionate, objective, and impersonal — even though the essay is deeply personal. In this style, the writer may even refer to themselves in the third person (using "he," "she," or sometimes their own name) instead of the usual first person ("I").

This approach can offer a unique angle and a distinctive narrative voice, though it requires some artistry to maintain clarity and a strong connection with the reader.

Choosing a Dominant Format: Personal Essay vs. Personal Narrative

When choosing the best format for a college essay, you’ll want to start with brainstorming and ideation.

Your final choice of format and perspective will depend on the prompt in particular, and how you envision responding to the prompt.

What kind of information is the prompt asking you to share about yourself?

- If a prompt asks an applicant to delve into their “life story” so to speak, most writers will find a narrative format a natural choice.

- If a prompt asks the applicant to share their thoughts about a core value or concept shaping their academic goals and interests, the writer will probably find a reflective essay format is best.

- Another writer, however, may have a gripping life experience, or set of experiences, that shaped a core value in their life, so they may want to share these experiences using narrative features within a larger essay structure.

As you can see, both narrative features and analytical essay features can be effective for a college essay.

When deciding which formats are best for your essay, you’ll want to consider both the prompt itself and the kind of content you want to share based on your personal circumstances.

Showing, Not Telling

Whether you choose a narrative or essay format, the purpose of a college essay is to introduce yourself in a very personal way, including expressing some personal, intellectual, and emotional honesty, authenticity, and vulnerability, rather than just listing autobiographical data, as on a resume.

Doing this effectively can also make an essay more memorable, leaving a stronger impact on the reader (which is a challenge when top schools have so many applicants).

Showing, not telling is an effective strategy to create a stronger bond between writer and reader, and to cultivate empathy and intimacy.

Tips and Techniques for Showing, Not Telling

- Use Anecdotes : Share personal stories that reveal key aspects of your personality, character, or perspectives in a narrative style.

- Use an Authentic First-Person Voice : Write in a way that allows the reader to hear your unique voice and thoughts, rather than adopting an academic tone.

- Cultivate Empathy : Aim to make the reader feel as if they are walking in your shoes, getting to know you as they would a character in a novel.

- Show Authenticity and Vulnerability : Include your thought process, doubts, and the evolution of your beliefs or values, reflecting personal growth and individuality.

- Incorporate Introspection : Enrich your narrative with insights into your inner thoughts, impressions, and changing understandings.

- Embrace Subjectivity : Share candid, fun, and interesting details about yourself using your authentic voice.

- Use Vivid Descriptions : Depict scenes, people, or settings with sensory details, dialogue, and inner thoughts to show rather than tell.

Key Takeaways for the College Essay Format

- Understanding the Context : The "college essay" here refers to the personal essays you write for college applications, not the academic essays you'll write in college classes.

- Format Flexibility : This type of essay is not a 5-paragraph academic or expository essay. It typically takes the form of a personal essay or personal narrative.

- Choosing the Right Format : Select a format—personal essay or personal narrative—that best suits the prompt and the story or message you want to convey. Align your format with the content you wish to highlight.

- Showing vs. Telling : Focus on "showing" through vivid descriptions, anecdotes, and introspection. However, a more reflective essay may emphasize ideas and concepts over storytelling.

Key Do’s and Don’ts

- Use an Authentic Voice : Let your true personality and perspective shine through.

- Engage the Reader : Share insights that reveal compelling personal qualities or traits.

- Show, Don’t Tell : Use vivid descriptions, candid reflections, and personal stories to illustrate your points.

- Be Introspective : Reflect on your experiences and share your thought process, showing authenticity and vulnerability.

- Make a Positive Impression : Highlight your strengths while being honest and humble.

- Always Get Outside Input: Always have a trusted peer and trusted adult, a skilled admissions counselor if possible, give you input before you spend too much time on an essay or submit a final version of an essay.

- Don't Overshare: You want to help schools know you, and you want to make a memorable impression, but a college application is not an arena for sharing overly personal or overly sensitive details about your life. Be sincere and genuine but remain discreet and professional overall.

- Avoid Boasting : Refrain from listing achievements or writing a resume in essay form.

- Don’t Repeat Application Information : Avoid discussing grades or activities already covered in other parts of your application. Use your essay to add depth and insight beyond the facts.

We’ve done a deep dive into the format, perspective, and kinds of writing elements to use in a college essay. But when it comes time to put it together — to outline, compose, and organize — you’ll often find you really don’t have a lot of room in a college essay. this makes it imperative to work within a well defined structure that fits your prompt and the content you're sharing.

In Part III, below, you'll learn crucial tips for structuring an essay so it's memorable and makes its mark on readers. You'll also discover just how many kinds of creative structures you can choose from!

Red Flags To Avoid On Your College Essay

Top 5 Common App Personal Essay Red Flags

Part III: The Structure of a College Essay

First, let’s take a look at how to structure the beginning, middle, and end of a college essay to make it as effective as possible.

Start Your Essay With a Strong Hook

You’ll want an effective hook to give your essay a strong start, and set the stage for making a bigger impact on your reader, helping your essay, and application, stand out!

A creative and imaginative hook is one that announces a larger, unifying theme and also creates some form of invitation or tension, drawing the reader in, so almost without realizing it, they need to read the next part and can't wait to find out more…

One caution here: don’t create a “hook” because you think it’s necessary to show you’re a “good writer.” That’s not really the point.

- The hook should be one hundred percent authentic to what you’re revealing or introducing about yourself

- The hook should bring to the foreground a compelling theme, question, doubt, emotion, or conflict (to be explored and potentially also resolved later in the essay or narrative)

- The hook gets the college essay off to a strong start, so the reader forgets the pile of essays on their desk, being drawn into your story, or your dilemma, or your thoughts…

- Instead of thinking about an “introduction” to your essay, as in a 5-Paragraph Essay, imagine you’re skipping the introduction— the preliminaries — altogether. Go straight to the heart of the matter instead. This is like grabbing the reader by the shirt, or like shooting a gun to start a race!

Create intrigue, suspense, or curiosity…

Since a hook can take so many forms and needs to be so integral to your essay, there’s no fixed recipe to offer.

That said, one way to gauge the power of a hook is by the measure of intrigue, emotion, and curiosity it sparks in the reader .

Here are examples for inspiration:

When I read Frederick Douglass’ account of learning how to read while enslaved, there was one detail that I couldn’t forget, one I’ve been thinking about in my own life over and over again…

My brother died when I was only thirteen and while I look whole on the outside, I sometimes think if people really could see me it would be like I was missing a leg or confined to a wheelchair, it’s just that it’s not physical, but the loss doesn't go away and makes me feel different. And it's become part of who I am.

My stepfather doesn’t believe college is worth it and doesn’t approve of my decision to go to college, let alone go to a really selective one. One week in my junior year the conflict took a turn for the worse, but what happened eventually helped me understand why my motivation to study political science is different from the interest others have in fixing laws and making the country better.

As you can see, each hook has most or all of these features:

- Spotlights a dominant question, emotion, or conflict

- Leaves something crucial unsaid (for the time being), sparking intrigue, suspense, and curiosity

- Announces a central theme , such as an idea or concept shaping my worldview; a key insight into my own sense of self and identity; a compelling conflict that ended up shaping my academic interests...

- Cultivates intimacy and a bond with the reader , immediately conveying honesty, authenticity, and a dose of vulnerability.

With an effective hook your essay comes out of the gate like a racehorse, beginning with the very first sentence! Most likely your reader won’t put down your essay to go to the concession stand either. Instead, they'll keep reading and really start to care about your story and your educational aspirations and future!

The Middle Phase: A Body of Ideas, Experiences, Impressions…

The middle phase is all the stuff you need to share to add depth and conviction to your writing and core themes, while also maintaining the reader’s engagement. It will also help you personalize your essay, as you share inner thoughts or recount real personal experiences.

Here are some strategies you may find helpful as you develop your ideas for this section of your essay.

Note: you may need to ignore what's not relevant or less relevant based on the structure, content, or approach you're using.

1. Develop Your Narrative or Argument

- Build on the Introduction : Expand on the themes, ideas, or experiences introduced at the beginning. This helps create a sense of continuity and deepens the reader's understanding of your perspective.

- Include Specific Examples : Use concrete examples, anecdotes, or details to illustrate your points. Specificity adds credibility and helps the reader connect with your experiences on a personal level.

- Show, Don’t Just Tell : Use descriptive language and sensory details to create vivid images that allow the reader to experience the story alongside you. This technique makes your writing more engaging and impactful.

2. Maintain a Clear Structure

- Use a Well-defined and Well-aligned Structure : Be clear on the structure you’re using and how it aligns with your content. You have lots of structures to choose from (as you’ll see in a moment), so don’t get stuck thinking about your college essay like it’s a 5-Paragraph Essay; it’s not. Clear organization helps the reader follow your train of thought, but some essays will be great with more creative, less linear structures, to create strong sensory impressions or elicit emotional responses from the reader.

- Develop Key Themes : Reinforce your main themes or ideas throughout the middle section. Repeated references to these themes emphasize their importance and help create a unified narrative.

3. Show Growth and Reflection

- Explore Personal Growth : Use the middle section to delve into how your experiences have shaped you. Reflect on challenges you’ve faced, lessons you’ve learned, and how you’ve changed over time.