- Biographies & Memoirs

- Professionals & Academics

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

| This item cannot be shipped to your selected delivery location. Please choose a different delivery location. |

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

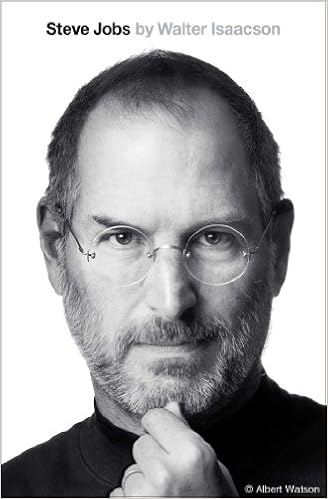

Steve Jobs Hardcover – Big Book, October 24, 2011

- Print length 656 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Simon & Schuster

- Publication date October 24, 2011

- Dimensions 6.13 x 2.2 x 9.25 inches

- ISBN-10 1451648537

- ISBN-13 978-1451648539

- Lexile measure 1080L

- See all details

More items to explore

From the Publisher

Editorial Reviews

Amazon.com review.

Amazon Exclusive: A Q&A with Walter Isaacson

Q: It's becoming well known that Jobs was able to create his Reality Distortion Field when it served him. Was it difficult for you to cut through the RDF and get beneath the narrative that he created? How did you do it?

Isaacson: Andy Hertzfeld, who worked with Steve on the original Macintosh team, said that even if you were aware of his Reality Distortion Field, you still got caught up in it. But that is why Steve was so successful: He willfully bent reality so that you became convinced you could do the impossible, so you did. I never felt he was intentionally misleading me, but I did try to check every story. I did more than a hundred interviews. And he urged me not just to hear his version, but to interview as many people as possible. It was one of his many odd contradictions: He could distort reality, yet he was also brutally honest most of the time. He impressed upon me the value of honesty, rather than trying to whitewash things.

Q: How were the interviews with Jobs conducted? Did you ask lots of questions, or did he just talk?

Isaacson: I asked very few questions. We would take long walks or drives, or sit in his garden, and I would raise a topic and let him expound on it. Even during the more formal sessions in his living room, I would just sit quietly and listen. He loved to tell stories, and he would get very emotional, especially when talking about people in his life whom he admired or disdained.

Q: He was a powerful man who could hold a grudge. Was it easy to get others to talk about Jobs willingly? Were they afraid to talk?

Isaacson: Everyone was eager to talk about Steve. They all had stories to tell, and they loved to tell them. Even those who told me about his rough manner put it in the context of how inspiring he could be.

Q: Jobs embraced the counterculture and Buddhism. Yet he was a billionaire businessman with his own jet. In what way did Jobs' contradictions contribute to his success?

Isaacson: Steve was filled with contradictions. He was a counterculture rebel who became a billionaire. He eschewed material objects yet made objects of desire. He talked, at times, about how he wrestled with these contradictions. His counterculture background combined with his love of electronics and business was key to the products he created. They combined artistry and technology.

Q: Jobs could be notoriously difficult. Did you wind up liking him in the end?

Isaacson: Yes, I liked him and was inspired by him. But I knew he could be unkind and rough. These things can go together. When my book first came out, some people skimmed it quickly and cherry-picked the examples of his being rude to people. But that was only half the story. Fortunately, as people read the whole book, they saw the theme of the narrative: He could be petulant and rough, but this was driven by his passion and pursuit of perfection. He liked people to stand up to him, and he said that brutal honesty was required to be part of his team. And the teams he built became extremely loyal and inspired.

Q: Do you believe he was a genius?

Isaacson: He was a genius at connecting art to technology, of making leaps based on intuition and imagination. He knew how to make emotional connections with those around him and with his customers.

Q: Did he have regrets?

Isaacson: He had some regrets, which he expressed in his interviews. For example, he said that he did not handle well the pregnancy of his first girlfriend. But he was deeply satisfied by the creativity he ingrained at Apple and the loyalty of both his close colleagues and his family.

Q: What do you think is his legacy?

Isaacson: His legacy is transforming seven industries: personal computers, animated movies, music, phones, tablet computing, digital publishing, and retail stores. His legacy is creating what became the most valuable company on earth, one that stood at the intersection of the humanities and technology, and is the company most likely still to be doing that a generation from now. His legacy, as he said in his "Think Different" ad, was reminding us that the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.

Photo credit: Patrice Gilbert Photography

About the Author

Excerpt. © reprinted by permission. all rights reserved., product details.

- Publisher : Simon & Schuster; 1st edition (October 24, 2011)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 656 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1451648537

- ISBN-13 : 978-1451648539

- Lexile measure : 1080L

- Item Weight : 2.16 pounds

- Dimensions : 6.13 x 2.2 x 9.25 inches

- #10 in Computers & Technology Industry

- #63 in Biographies of Business & Industrial Professionals

- #261 in Leadership & Motivation

Videos for this product

Click to play video

Book Review of Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson - BookThinkers

Nick Hutchison

Steve Jobs life journey is a must for every entrepreneur!

Merchant Video

Customer Review: There's many biography about Steve Jobs out there. But they couldn't match this.

About the author

Walter isaacson.

Walter Isaacson is writing a biography of Elon Musk. He is the author of The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race; Leonardo da Vinci; Steve Jobs; Einstein: His Life and Universe; Benjamin Franklin: An American Life; The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution; and Kissinger: A Biography. He is also the coauthor of The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made. He is a Professor of History at Tulane, has been CEO of the Aspen Institute, chairman of CNN, and editor of Time magazine.

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 78% 16% 4% 1% 1% 78%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 78% 16% 4% 1% 1% 16%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 78% 16% 4% 1% 1% 4%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 78% 16% 4% 1% 1% 1%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 78% 16% 4% 1% 1% 1%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Customers say

Customers find the book marvelous, engrossing, and fascinating. They also find it informative, objective, and a great case study of three companies. Readers describe the writing quality as easy to read, beautiful, and well-written. They mention the biography is rich and telling. They describe the storytelling as compelling, exciting, and entertaining. Readers praise the author's writing style as compelling and frank.

AI-generated from the text of customer reviews

Customers find the book marvelously engrossing, fascinating, and easy to read. They say it's full of stories and anecdotes. Readers also mention the book chronicles well and provides a journey of discovery.

"...I Jove it when you can bring really great design and simple capability to something that doesn't cost much," he said as he pointed out the clean..." Read more

"...It's a story worth reading . If for nothing else, read it to understand what it took to create the device on which you're reading this very review." Read more

"...of it - until the last few chapters - was very well written and interesting ...." Read more

"Book review by Richard L. Weaver II, Ph.D.This is a fascinating , if not riveting, story that is not only well-written and well-..." Read more

Customers find the book very informative and brilliant. They say it provides a great case study of three companies. Readers also mention the book is objective, even critical. They describe it as an intelligent, readable, and accurate story.

"... Intuition is a very powerful thing , more powerful than intellect, in my opinion. That's had a big impact on my work."..." Read more

"...The book offers a great case study of three companies: Apple, NeXT and Pixar...." Read more

"...more in the last few chapters, but most of the book seemed to be very objective , even critical...." Read more

"...bright, imaginative, creative, intelligent, educated, and knowledgeable , but the way he treated others, the way he thought about others who were not..." Read more

Customers find the book easy to read, well-written, and easy to follow. They say it's accessible and doesn't overtly technical in nature. Readers appreciate the carefully chosen and crafted words. They also mention the losing battle to cancer is described with gracious transparency.

"...but even so, most of it - until the last few chapters - was very well written and interesting...." Read more

"...This is a fascinating, if not riveting, story that is not only well-written and well-constructed (organized in a chronological manner), but it is..." Read more

"...Through Isaacson's insightful eyes and his carefully chosen and crafted words , I feel I have personally met a man that will be remembered as an..." Read more

Customers find the biography rich, telling, and surprisingly public. They say it's personal, introspective, and charismatic. Readers also mention the book is a vivid reminder of God's common grace.

"...Most importantly, this is a very personal book ...." Read more

"Walter Isaacson's Steve Jobs is a comprehensive, well-researched biography that does justice to the complexity of Jobs' life and legacy...." Read more

"... Great biography ." Read more

"...The biography is filled with interesting tidbits and should be at the top of everyone's reading list...." Read more

Customers find the storytelling compelling, exciting, and entertaining. They say it provides a look into an incredible life. Readers also mention the book is gripping and riveting.

"...While it could have benefited from tighter editing, it remains a compelling and insightful read...." Read more

"...This book didn't disappoint. It was both captivating , and offered meaningful insight into Steve Jobs and the history of Apple...." Read more

"...much for reading biographies, but this one is compelling, even exciting . As I write this review, it has been only 45 days since Steve Jobs died...." Read more

"...Steve Jobs" was a riveting , fast and easy read, utterly fascinating because Jobs' life, accomplishments and personality was so...." Read more

Customers find the author's writing style compelling, frank, and nice. They say it's an extraordinary biography of a creative genius. Readers also mention the narration of his own words is clear and helps capture the story.

"...Sure, he was incredibly bright, imaginative, creative , intelligent, educated, and knowledgeable, but the way he treated others, the way he thought..." Read more

" Loved the writing style and storytelling ...." Read more

"...(friends, foes, lovers, rivals, you name it), he has created a remarkably personal portrait -- one that brought me to tears on more occasions than I..." Read more

"...Walter Issacson's biography is highly readable and very compelling...." Read more

Customers find the book very honest, real, and compelling. They say it provides a compelling but realistic view of one of the greatest innovators of our time. Readers also mention the author writes with a measured yet realistic respect.

"...It is an honest , complete, and intimate conclusion that accurately and completely draws together many of the comments, reactions, and..." Read more

"...It was delightful and fascinating while feeling authentic and true to his character and the beginning of Apple. I learned a lot." Read more

"...I was impressed by the candidness of the interviews ...." Read more

"...She crafted what I consider to be the perfect, visceral , and emotional post-script to the Isaacson biography. It will bring you to tears...." Read more

Customers have mixed opinions about the pacing of the book. Some find it beguiling, eccentric, and cringe-worthy. Others say the book is incomplete, chaotic, and unprofessional. They also mention the language is flat, dull, and riddled with technical errors.

"...churning details how Steve Jobs was a disloyal, lying, backstabbing, vindictive , manipulative, vengeful, and all-around vile and damaged human being...." Read more

"...Instead, he was a genius. His imaginative leaps were instinctive, unexpected , and at times magical...." Read more

"...The last segment of the book - Apple II - I found to be rather dry , with a sort of hurried, factual quality to it..." Read more

"...express himself at the end was a beautiful, warm, and touching way to conclude the book . Just as Jobs was a true genius (very few measure up!),..." Read more

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Humanities ›

- History & Culture ›

- Inventions ›

- Computers & The Internet ›

Biography of Steve Jobs, Co-Founder of Apple Computers

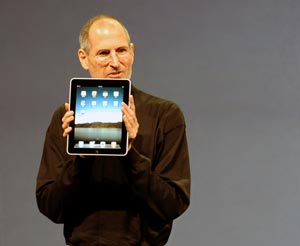

David Paul Morris / Stringer / Getty Images

- Computers & The Internet

- Famous Inventions

- Famous Inventors

- Patents & Trademarks

- Invention Timelines

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Out of Mom and Pop's Garage

Apple Corporation

Disney pixar, expanding apple.

Steve Jobs (February 24, 1955–October 5, 2011) is best remembered as the co-founder of Apple Computers . He teamed up with inventor Steve Wozniak to create one of the first ready-made PCs. Besides his legacy with Apple, Jobs was also a smart businessman who became a multimillionaire before the age of 30. In 1984, he founded NeXT computers. In 1986, he bought the computer graphics division of Lucasfilm Ltd. and started Pixar Animation Studios.

Fast Facts: Steve Jobs

- Known For : Co-founding Apple Computer Company and playing a pioneering role in the development of personal computing

- Also Known As : Steven Paul Jobs

- Born : February 24, 1955 in San Francisco, California

- Parents : Abdulfattah Jandali and Joanne Schieble (biological parents); Paul Jobs and Clara Hagopian (adoptive parents)

- Died : October 5, 2011 in Palo Alto, California

- Education : Reed College

- Awards and Honors : National Medal of Technology (with Steve Wozniak), Jefferson Award for Public Service, named the most powerful person in business by Fortune magazine, Inducted into the California Hall of Fame, inducted as a Disney Legend

- Spouse : Laurene Powell

- Children : Lisa (by Chrisann Brennan), Reed, Erin, Eve

- Notable Quote : "Of all the inventions of humans, the computer is going to rank near or at the top as history unfolds and we look back. It is the most awesome tool that we have ever invented. I feel incredibly lucky to be at exactly the right place in Silicon Valley, at exactly the right time, historically, where this invention has taken form."

Jobs was born on February 24, 1955, in San Francisco, California. The biological child of Abdulfattah Jandali and Joanne Schieble, he was later adopted by Paul Jobs and Clara Hagopian. During his high school years, Jobs worked summers at Hewlett-Packard. It was there that he first met and became partners with Steve Wozniak.

As an undergraduate, he studied physics, literature, and poetry at Reed College in Portland, Oregon. Formally, he only attended one semester there. However, he remained at Reed and crashed on friends' sofas and audited courses that included a calligraphy class, which he attributes as being the reason Apple computers had such elegant typefaces.

After leaving Oregon in 1974 to return to California, Jobs started working for Atari , an early pioneer in the manufacturing of personal computers. Jobs' close friend Wozniak was also working for Atari. The future founders of Apple teamed up to design games for Atari computers.

Jobs and Wozniak proved their skills as hackers by designing a telephone blue box. A blue box was an electronic device that simulated a telephone operator's dialing console and provided the user with free phone calls. Jobs spent plenty of time at Wozniak's Homebrew Computer Club, a haven for computer geeks and a source of invaluable information about the field of personal computers.

Out of Mom and Pop's Garage

By the late 1970s, Jobs and Wozniak had learned enough to try their hand at building personal computers. Using Jobs' family garage as a base of operation, the team produced 50 fully assembled computers that were sold to a local Mountain View electronics store called the Byte Shop. The sale encouraged the pair to start Apple Computer, Inc. on April 1, 1979.

The Apple Corporation was named after Jobs' favorite fruit. The Apple logo was a representation of the fruit with a bite taken out of it. The bite represented a play on words: bite and byte.

Jobs co-invented the Apple I and Apple II computers together with Wozniak, who was the main designer, and others. The Apple II is considered to be one of the first commercially successful lines of personal computers. In 1984, Wozniak, Jobs, and others co-invented the Apple Macintosh computer, the first successful home computer with a mouse-driven graphical user interface. It was, however, based on (or, according to some sources, stolen from) the Xerox Alto, a concept machine built at the Xerox PARC research facility. According to the Computer History Museum, the Alto included:

A mouse. Removable data storage. Networking. A visual user interface. Easy-to-use graphics software. “What You See Is What You Get” (WYSIWYG) printing, with printed documents matching what users saw on screen. E-mail. Alto for the first time combined these and other now-familiar elements in one small computer.

During the early 1980s, Jobs controlled the business side of the Apple Corporation. Steve Wozniak was in charge of the design side. However, a power struggle with the board of directors led to Jobs leaving Apple in 1985.

After leaving Apple, Jobs founded NeXT, a high-end computer company. Ironically, Apple bought NeXT in 1996 and Jobs returned to his old company to serve once more as its CEO from 1997 until his retirement in 2011.

The NeXT was an impressive workstation computer that sold poorly. The world's first web browser was created on a NeXT, and the technology in NeXT software was transferred to the Macintosh and the iPhone .

In 1986, Jobs bought "The Graphics Group" from Lucasfilm's computer graphics division for $10 million. The company was later renamed Pixar. At first, Jobs intended for Pixar to become a high-end graphics hardware developer, but that goal was never met. Pixar moved on to do what it now does best, which is make animated films. Jobs negotiated a deal to allow Pixar and Disney to collaborate on a number of animated projects that included the film "Toy Story." In 2006, Disney bought Pixar from Jobs.

After Jobs returned to Apple as its CEO in 1997, Apple Computers had a renaissance in product development with the iMac, iPod , iPhone, iPad, and more.

Before his death, Jobs was listed as the inventor and/or co-inventor on 342 United States patents, with technologies ranging from computer and portable devices to user interfaces, speakers, keyboards, power adapters, staircases, clasps, sleeves, lanyards, and packages. His last patent was issued for the Mac OS X Dock user interface and was granted the day before his death.

Steve Jobs died at his home in Palo Alto, California, on October 5, 2011. He had been ill for a long time with pancreatic cancer, which he had treated using alternative techniques. His family reported that his final words were, "Oh wow. Oh wow. Oh wow."

Steve Jobs was a true computer pioneer and entrepreneur whose impact is felt in almost every aspect of contemporary business, communication, and design. Jobs was absolutely dedicated to every detail of his products—according to some sources, he was obsessive—but the outcome can be seen in the sleek, user-friendly, future-facing designs of Apple products from the very start. It was Apple that placed the PC on every desk, provided digital tools for design and creativity, and pushed forward the ubiquitous smartphone which has, arguably, changed the ways in which humans think, create, and interact.

- Computer History Museum. " What Was The First PC? "

- Gladwell, Malcolm, and Malcolm Gladwell. “ The Real Genius of Steve Jobs .” The New Yorker , 19 June 2017.

- Levy, Steven. “ Steve Jobs .” Encyclopædia Britannica , 20 Feb. 2019.

- A History of Apple Computers

- Biography of Bill Gates, Co-Founder of Microsoft

- The Unusual History of Microsoft Windows

- History of Computer Memory

- The History of HTML and How It Revolutionized the Internet

- Who Invented Twitter

- Top 10 Authorized and Unauthorized Books About Bill Gates

- John Mauchly: Computer Pioneer

- The History of Google and How It Was Invented

- The History of the Internet

- The IBM 701

- The Inventor of Touch Screen Technology

- Doctor Ian Getting and the Global Positioning System (GPS)

- The History of the Integrated Circuit (Microchip)

- The Most Important Inventions of the 21st Century

- Jack Kilby, Father of the Microchip

Biography Online

Steve Jobs Biography

Steve Jobs was born in San Francisco, 1955, to two university students Joanne Schieble and Syrian-born John Jandali. They were both unmarried at the time, and Steven was given up for adoption.

Steven was adopted by Paul and Clara Jobs, whom he always considered to be his real parents. Steven’s father, Paul, encouraged him to experiment with electronics in their garage. This led to a lifelong interest in electronics and design.

Jobs attended a local school in California and later enrolled at Reed College, Portland, Oregon. His education was characterised by excellent test results and potential. But, he struggled with formal education and his teachers reported he was a handful to teach.

At Reed College, he attended a calligraphy course which fascinated him. He later said this course was instrumental in Apple’s multiple typefaces and proportionally spaced fonts.

Steve Jobs in India

In 1974, Jobs travelled with Daniel Kottke to India in search of spiritual enlightenment. They travelled to the Ashram of Neem Karoli Baba in Kainchi. During his several months in India, he became aware of Buddhist and Eastern spiritual philosophy. At this time, he also experimented with psychedelic drugs; he later commented that these counter-culture experiences were instrumental in giving him a wider perspective on life and business.

“Bill Gates‘d be a broader guy if he had dropped acid once or gone off to an ashram when he was younger.” – Steve Jobs, The New York Times, Creating Jobs, 1997

Job’s first real computer job came working for Atari computers. During his time at Atari, Jobs came to know Steve Wozniak well. Jobs greatly admired this computer technician, whom he had first met in 1971.

Steve Jobs and Apple

In 1976, Wozniak invented the first Apple I computer. Jobs, Wozniak and Ronald Wayne then set up Apple computers. In the very beginning, Apple computers were sold from Jobs parents’ garage.

Over the next few years, Apple computers expanded rapidly as the market for home computers began to become increasingly significant.

In 1984, Jobs designed the first Macintosh. It was the first commercially successful home computer to use a graphical user interface (based on Xerox Parc’s mouse driver interface.) This was an important milestone in home computing and the principle has become key in later home computers.

Despite the many innovative successes of Jobs at Apple, there was increased friction between Jobs and other workers at Apple. In 1985, removed from his managerial duties, Jobs resigned and left Apple. He later looked back on this incident and said that getting fired from Apple was one of the best things that happened to him – it helped him regain a sense of innovation and freedom, he couldn’t find work in a large company.

Life After Apple

Steve Jobs and Bill Gates. Photo Joi Ito

On leaving Apple, Jobs founded NeXT computers. This was never particularly successful, failing to gain mass sales. However, in the 1990s, NeXT software was used as a framework in WebObjects used in Apple Store and iTunes store. In 1996, Apple bought NeXT for $429 million.

Much more successful was Job’s foray into Pixar – a computer graphic film production company. Disney contracted Pixar to create films such as Toy Story, A Bug’s Life and Finding Nemo. These animation movies were highly successful and profitable – giving Jobs respect and success.

In 1996, the purchase of NeXT brought Jobs back to Apple. He was given the post of chief executive. At the time, Apple had fallen way behind rivals such as Microsoft, and Apple was struggling to even make a profit.

Return to Apple

Photo: Matt Buchanan

Jobs launched Apple in a new direction. With a certain degree of ruthlessness, some projects were summarily ended. Instead, Jobs promoted the development of a new wave of products which focused on accessibility, appealing design and innovate features.

The iPod was a revolutionary product in that it built on existing portable music devices and set the standard for portable digital music. In 2008, iTunes became the second biggest music retailer in the US, with over six billion song downloads and over 200 million iPods sold.

In 2007, Apple successfully entered the mobile phone market, with the iPhone. This used features of the iPod to offer a multi-functional and touchscreen device to become one of the best-selling electronic products. In 2010, he introduced the iPad – a revolutionary new style of tablet computers.

The design philosophy of Steve Jobs was to start with a fresh slate and imagine a new product that people would want to use. This contrasted with the alternative approach of trying to adapt current models to consumer feedback and focus groups. Job’s explains his philosophy of innovative design.

“But in the end, for something this complicated, it’s really hard to design products by focus groups. A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.”

– Steve Jobs, BusinessWeek (25 May 1998)

Apple has been rated No.1 in America’s most admired companies. Jobs management has been described as inspirational, although c-workers also state, Jobs could be a hard taskmaster and was temperamental. NeXT Cofounder Dan’l Lewin was quoted in Fortune as saying of that period, “The highs were unbelievable … But the lows were unimaginable.”

“My job is not to be easy on people. My jobs is to take these great people we have and to push them and make them even better.” – All About Steve Jobs [link]

Under Jobs, Apple managed to overtake Microsoft regarding share capitalization. Apple also gained a pre-eminent reputation for the development and introduction of groundbreaking technology. Interview in 2007, Jobs said:

“There’s an old Wayne Gretzky quote that I love. ‘I skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been.’ And we’ve always tried to do that at Apple. Since the very very beginning. And we always will.”

Despite, growing ill-health, Jobs continued working at Apple until August 2011, when he resigned.

“I was worth over $1,000,000 when I was 23, and over $10,000,000 when I was 24, and over $100,000,000 when I was 25, and it wasn’t that important because I never did it for the money.”

– Steve Jobs

Jobs earned only $1million as CEO of Apple. But, share options from Apple and Disney gave him an estimated fortune of $8.3billion.

Personal life

In 1991, he married Laurene Powell, together they had three children and lived in Palo Alto, California.

In 2003, he was diagnosed with Pancreatic Cancer. Over the next few years, Jobs struggled with health issues and was often forced to delegate the running of Apple to Tim Cook. In 2009, he underwent a liver transplant, but two years later serious health problems returned. He worked intermittently at Apple until August 2011, where he finally retired to concentrate on his deteriorating health. He died as a result of complications from his pancreatic cancer, suffering cardiac arrest on 5 October 2011 in Palo Alto, California.

In addition to his earlier interest in Eastern religions, Jobs expressed sentiments of agnosticism.

“ Sometimes I believe in God, sometimes I don’t. I think it’s 50-50 maybe. But ever since I’ve had cancer, I’ve been thinking about it more. And I find myself believing a bit more. I kind of – maybe it’s ’cause I want to believe in an afterlife. That when you die, it doesn’t just all disappear.”

Quote in Biography by Walter Isaacson.

Steve Jobs is buried in an unmarked grave at Alta Mesa Memorial Park, a nonsectarian cemetery in Palo Alto.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “Biography of Steve Jobs”, Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net. Published 25th Feb. 2012. Last updated 11th March 2019.

Steve Jobs: The Exclusive Biography

Steve Jobs: The Exclusive Biography at Amazon

Related pages

- Steve Jobs Quotes

- All About Steve Jobs

- Steve Jobs at BBC

This is beautiful. He’s one of my role models. RIP Jobs

- January 20, 2019 7:27 AM

This is very inspirational to all of us in the world today. He made the impossible the possible, he will always be remembered for his great work done. Congrats Steve you are an inspiration!

- January 16, 2019 5:29 PM

He made life easier for us all, nothing would be the way it is today without him.

- December 19, 2018 2:19 PM

Steve job amazing man

- October 27, 2018 7:01 AM

- By Rambharat

I agree 100%.

- December 05, 2018 9:13 PM

- By Roman Lopez

Very nice biography

- September 04, 2018 12:47 PM

Steve jobs! His lesson reminds alot,but Steve went to school ,through colleges he attained ajob that has resulted him into many champions in business and other s.now how can someone has no such gualification also leave such great impact.

- December 05, 2017 1:35 AM

- By Natanyakhu moses

- Born February 24 , 1955 · San Francisco, California, USA

- Died October 5 , 2011 · Palo Alto, California, USA (pancreatic cancer)

- Birth name Steven Paul Jobs

- Height 6′ 2″ (1.88 m)

- Steven Paul Jobs was born on 24 February 1955 in San Francisco, California, to students Abdul Fattah Jandali and Joanne Carole Schieble who were unmarried at the time and gave him up for adoption. He was taken in by a working class couple, Paul and Clara Jobs, and grew up with them in Mountain View, California. He attended Homestead High School in Cupertino California and went to Reed College in Portland Oregon in 1972 but dropped out after only one semester, staying on to "drop in" on courses that interested him. He took a job with video game manufacturer Atari to raise enough money for a trip to India and returned from there a Buddhist. Back in Cupertino he returned to Atari where his old friend Steve Wozniak was still working. Wozniak was building his own computer and in 1976 Jobs pre-sold 50 of the as-yet unmade computers to a local store and managed to buy the components on credit solely on the strength of the order, enabling them to build the Apple I without any funding at all. The Apple II followed in 1977 and the company Apple Computer was formed shortly afterwards. The Apple II was credited with starting the personal computer boom, its popularity prompting IBM to hurriedly develop their own PC. By the time production of the Apple II ended in 1993 it had sold over 6 million units. Inspired by a trip to Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), engineers from Apple began working on a commercial application for the graphical interface ideas they had seen there. The resulting machine, Lisa, was expensive and never achieved any level of commercial success, but in 1984 another Apple computer, using the same WIMP (Windows, Icons, Menus, Pointer) interface concept, was launched. An advert during the 1984 Super Bowl, directed by Ridley Scott introduced the Macintosh computer to the world (in fact, the advert had been shown on a local TV channel in Idaho on 31 December 1983 and in movie theaters during January 1984 before its famous "premiere" on 22 January during the Super Bowl). In 1985 Jobs was fired from Apple and immediately founded another computer company, NeXT. Its machines were not a commercial success but some of the technology was later used by Apple when Jobs eventually returned there. In the meantime, in 1986, Jobs bought The Computer Graphics Group from Lucasfilm. The group was responsible for making high-end computer graphics hardware but under its new name, Pixar, it began to produce innovative computer animations. Their first title under the Pixar name, Luxo Jr. (1986) won critical and popular acclaim and in 1991 Pixar signed an agreement with Disney, with whom it already had a relationship, to produce a series of feature films, beginning with Toy Story (1995) . In 1996 Apple bought NeXT and Jobs returned to Apple, becoming its CEO. With the help of British-born industrial designer Jonathan Ive , Jobs brought his own aesthetic philosophy back to the ailing company and began to turn its fortunes around with the release of the iMac in 1998. The company's MP3 player, the iPod, followed in 2001, with the iPhone launching in 2007 and the iPad in 2010. The company's software music player, iTunes, evolved into an online music (and eventually also movie and software application) store, helping to popularize the idea of "legally" downloading entertainment content. In 2003, Jobs was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and underwent surgery in 2004. Despite the success of this operation he became increasingly ill and received a liver transplant in 2009. He returned to work after a six month break but eventually resigned his position in August 2011 after another period of medical leave which began in January 2011. He died on 5 October 2011. - IMDb Mini Biography By: IMDb Editors

- Spouse Laurene Powell-Jobs (March 18, 1991 - October 5, 2011) (his death, 3 children)

- Children Lisa Brennan-Jobs Eve Jobs

- Relatives Mona Simpson (Sibling)

- Black turtleneck sweatshirt and blue jeans - he owned over a hundred

- CEO of Pixar Animation Studios

- Has a daughter, Lisa, from a previous relationship. She is the namesake of Apple's computer, the Lisa.

- When Apple Computer appointed its first Board of Directors, they insisted that all employees wear name badges with a number indicating the order in which they were hired. They assigned Steve Wozniak , who did all the engineering of the highly successful Apple II computer, the title Employee No. 1. Steve Jobs was officially Employee No. 2. He protested, but the board refused to change the badge assignments. Jobs offered a compromise: He would be Employee No. 0, since 0 comes before 1 on the mathematical model known as a number line.

- In Forbes Magazine's listing of the 400 Richest Americans in 2005, Steve Jobs came in at number 67 with a total worth of $3.3 Billion.

- CEO of Pixar Animation Studios - the creators of Toy Story (1995) , A Bug's Life (1998) , Toy Story 2 (1999) , Monsters, Inc. (2001) , and Finding Nemo (2003) - as well as various shorts, including Oscar-winning Tin Toy (1988) , Geri's Game (1997) , and For the Birds (2000) .

- [February 1985, interview in "Playboy" magazine] I don't think I've ever worked so hard on something, but working on Macintosh was the neatest experience of my life. Almost everyone who worked on it will say that. None of us wanted to release it at the end. It was as though we knew that once it was out of our hands, it wouldn't be ours anymore. When we finally presented it at the shareholders' meeting, everyone in the auditorium gave it a five-minute ovation. What was incredible to me was that I could see the Mac team in the first few rows. It was as though none of us could believe we'd actually finished it. Everyone started crying.

- [1985] I'll always stay connected with Apple. I hope that throughout my life I'll sort of have the thread of my life and then the thread of Apple weave in and out, like a tapestry. There may be a few years when I'm not there, but I'll always come back.

- [2003] There are downsides to everything; there are unintended consequences to everything. The most corrosive piece of technology that I've ever seen is called television--but then, again, television, at its best, is magnificent.

- [1998] A lot of times, people don't know what they want until you show it to them.

- Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn't really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while.

Contribute to this page

- Learn more about contributing

More from this person

- View agent, publicist, legal and company contact details on IMDbPro

More to explore

Recently viewed.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Author Interviews

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Jobs' Biography: Thoughts On Life, Death And Apple

Walter Isaacson's biography of Apple co-founder Steve Jobs was published Monday, less than three weeks after Job's death on Oct. 5.

When Steve Jobs was 6 years old, his young next door neighbor found out he was adopted. "That means your parents abandoned you and didn't want you," she told him.

Jobs ran into his home, where his adoptive parents reassured him that he was theirs and that they wanted him.

"[They said] 'You were special, we chose you out, you were chosen," says biographer Walter Isaacson. "And that helped give [Jobs] a sense of being special. ... For Steve Jobs, he felt throughout his life that he was on a journey — and he often said, 'The journey was the reward.' But that journey involved resolving conflicts about ... his role in this world: why he was here and what it was all about."

When Jobs died on Oct. 5 from complications of pancreatic cancer, many people felt a sense of personal loss for the Apple co-founder and former CEO. Jobs played a key role in the creation of the Macintosh, the iPod, iTunes, the iPhone, the iPad — innovative devices and technologies that people have integrated into their daily lives.

Buy Featured Book

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

Jobs detailed how he created those products — and how he rose through the world of Silicon Valley, competed with Google and Microsoft, and helped transform popular culture — in a series of extended interviews with Isaacson, the president of The Aspen Institute and the author of biographies of Albert Einstein and Benjamin Franklin. The two men met more than 40 times throughout 2009 and 2010, often in Jobs' living room. Isaacson also conducted more than 100 interviews with Jobs' colleagues, relatives, friends and adversaries.

His biography tells the story of how Jobs revolutionized the personal computer. It also tells Jobs' personal story — from his childhood growing up in Mountain View, Calif., to his lifelong interest in Zen Buddhism to his relationship with family and friends.

In his last meetings with Isaacson, Jobs shifted the conversation to his thoughts regarding religion and death.

"I remember sitting in the back garden on a sunny day [on a day when] he was feeling bad, and he talked about whether or not he believed in an afterlife," Isaacson tells Fresh Air 's Terry Gross. "He said, 'Sometimes I'm 50-50 on whether there's a God. It's the great mystery we never quite know. But I like to believe there's an afterlife. I like to believe the accumulated wisdom doesn't just disappear when you die, but somehow it endures."

Jobs paused for a second, remembers Isaacson.

"And then he says, 'But maybe it's just like an on/off switch and click — and you're gone.' And then he paused for another second and he smiled and said, 'Maybe that's why I didn't like putting on/off switches on Apple devices.' "

'The Depth Of The Simplicity'

Jobs' attention to detail on his creations was unrivaled, says Isaacson. Though he was a technologist and a businessman, he was also an artist and designer.

"[He] connected art with technology," explains Isaacson. "[In his products,] he obsessed over the color of the screws, over the finish of the screws — even the screws you couldn't see." Even with the original Macintosh, he made sure that the circuit board's chips were lined up properly and looked good. He made them go back and redo the circuit board. He made them find the right color, find the right curves on the screw. Even the curves on the machine — he wanted it to feel friendly.

That obsessiveness occasionally drove his Apple co-workers crazy — but it also made them fiercely loyal, says Isaacson.

More On Steve Jobs

Remembering Steve Jobs (1955-2011)

Steve, myself, and i-: the big story of a little prefix.

New Bio Quotes Jobs On God, Gates And Great Design

Steve Jobs: How Apple's CEO Helped Transform Popular Culture

Timeline: Steve Jobs, The Man At Apple's Core

All Tech Considered

Apple's secret is in our dna.

Remembrances

Apple visionary steve jobs dies at 56.

Steve Jobs: 'Computer Science Is A Liberal Art'

"It's one of the dichotomies about Jobs: He could be demanding and tough and irate. On the other hand, he got all A-players and they became fanatically loyal to him," says Isaacson. "Why? They realized they were producing, with other A-players, truly great products for an artist who was a perfectionist — and wasn't always the kindest person when they failed — but he was rallying them to do great stuff."

He relays one story about Jobs that shows, he says, how much he was able to connect great ideas and innovations together. In the early 1980s, Jobs visited Xerox PARC, a research company in Palo Alto that had invented the laser printer, object-oriented programming and the Ethernet. Jobs noticed that the computers running at PARC all featured graphics on their desktops that allowed users to click icons and folders. This was new at the time: Most computers used text prompts and a text interface.

"Steve Jobs made an arrangement with Xerox and he took that concept [of the graphical user interface] and he improved it a hundred-fold," says Isaacson. "He made it so you could drag and drop some of the folders; he invented the pull-down menus. ... So what he was able to do was to take a conception and turn it into a reality."

That's where Jobs' genius was, Isaacson says. Jobs insisted that the software and hardware on Apple products needed to be fully integrated for the best user experience. It was not a great business model at first.

"Microsoft, which licensed itself promiscuously to all sorts of manufacturers, ends up with 90 to 95 percent all the operating system market by the beginning of 2000," says Isaacson. "But in the long run, the end-to-end integration system works very well for Apple and for Steve Jobs. Because it allows him to create devices [like the iPod and iPad] that just work beautifully with the machines."

Isaacson says working with Jobs gave him an additional insight into the design of Jobs' products.

"I see the depth of the simplicity," he says. "[I appreciate] the intuitive nature of the design, and how he would repeatedly sit there with his design engineers and his user-interface software people, and say, 'No, no no, I want to make it simpler.' I also appreciate the beauty of the parts unseen. His father taught him that the back of a fence or the back of a chest of drawers should be as beautiful as the front because [he] would know the craftsmanship that went into it. So somehow, it comes through — the depth of the beauty of the design."

Jobs was a perfectionist with a famously mercurial temperament. He was an artist and a visionary who "could be demanding and tough and irate," says Isaacson.

Interview Highlights

On what Jobs thought of the Microsoft operating system

Isaacson: "When it first came out — I can't use the words on the air — but [Jobs thought it was] clunky and not beautiful and not aesthetic. But as always is the case with Microsoft, it improves. And eventually Microsoft made a graphical operating system — Windows — and each new version got better until it was a dominating operating system."

On the rivalry between Jobs and Bill Gates

Hear Steve Jobs On Fresh Air

Listen to steve jobs' 1996 conversation with terry gross.

Isaacson: "There are all sorts of lawsuits where Apple is trying to sue Microsoft for Windows, for trying to steal the look and feel. Apple loses most of the suits but they drag on and there's even a government investigation. By the time Steve Jobs comes back to Apple in 1997, the relationship is horrible. And when we say that Jobs and Gates had a rivalry, we also have to realize they had a collaboration and a partnership. It was typical of the digital age — both rivalry and partnership."

On the relationship between Jobs and Google

Isaacson: "I think there was an unnerving historic resonance for what had happened a couple of decades earlier [with Microsoft]. Suddenly you have Google taking the operating system of the iPhone and mobile devices and all of the touch-screen technologies and building upon it, and making it an open technology that various device makers could use. ... Steve Jobs felt very possessive about all of the look, the feel, the swipes, the multitouch gestures that you use — and was driven to absolute distraction when Android's operating system, developed by Google and used by hardware manufacturers, started doing the exact same thing. ... He was furious but that probably understates his feeling. He was really furious and he let Eric Schmidt, who was then the CEO of Google, know it."

Walter Isaacson is president and CEO of The Aspen Institute. His other books include Einstein: His Life and Universe; Benjamin Franklin : An American Life , and Kissinger: A Biography .

More With Walter Isaacson

Einstein: relatively speaking, a complicated life, walter isaacson on benjamin franklin.

On Jobs' adoptive parents

Isaacson: "When Steve got placed with [parents who were not college graduates], his biological mother initially balked at first but ... the Jobs family made a pledge that they would start a college fund and make sure that Steve went to college."

On approaching Isaacson to write his biography

Isaacson: "It was 2004 and he had broached the subject of doing a biography of him and I thought, 'Well, this guy's in the midst of an up-and-down career and he has maybe 20 years to go, so I said to him, 'I'd love to do a biography of you but let's wait 20 or so years until you retire.' Then off and on after 2004, we would be in touch. ...

"I finally talked to his wife, who was very good at understanding his legacy, and she said, 'If you're going to do a book on Steve, you can't just keep saying, 'I'll do it in 20 years or so.' You really ought to do it now.' This was 2009. Steve Jobs, that year, had had a liver transplant and I realized how sick he was. ... And so, that was when I realized that this was a very fascinating tale and this guy may or may not make it. I thought he was going to live much longer. But at the very least, he was facing the prospect of his mortality so it was time for him to be reflective and do a book."

On his final meeting with Jobs

Isaacson: "He was pretty sick. He was confined to the house. And he said to me, at the end of our long conversation, 'There will be things in this book I don't like, right?' And I said, 'Yes.' Partly because you can interview people right after a meeting they've had with Steve Jobs [and] you interview five people and get five different stories about what happened. ... People have different perceptions of who he is. ...

"He said, 'I'll make you this promise. I'm not going to read the book until next year, until after it comes out.' And it made me feel a grand emotion, of 'Oh! That's great. Steve is going to be alive for another year.' Because when you're around him, the power of his thinking really grabs you. I remember leaving his house and thinking, 'Oh, I'm so relieved. He'll be alive in a year. He just told me so.' Logically, I should have said, 'He doesn't know what ups and downs he's going to have with his health.' But I think that he always felt some miracle would come along because all of his life, miracles had come along."

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Steve Jobs summary

Steve Jobs , (born Feb. 24, 1955, San Francisco, Calif., U.S.—died Oct. 5, 2011, Palo Alto, Calif.), U.S. businessman. Adopted in infancy, he grew up in Cupertino, Calif. He dropped out of Reed College and went to work for Atari Corp. designing video games. In 1976 he cofounded (with Stephen Wozniak ) Apple Computer (incorporated in 1977; now Apple Inc. ). The first Apple computer, created when Jobs was only 21, changed the public’s idea of a computer from a huge machine for scientific use to a home appliance that could be used by anyone. Apple’s Macintosh computer, which appeared in 1984, introduced a graphical user interface and mouse technology that became the standard for all applications interfaces. In 1980 Apple became a public corporation, and Jobs became the company’s chairman. Management conflicts led him to leave Apple in 1985 to form NeXT Computer Inc., but he returned to Apple in 1996 and became CEO in 1997. The striking new iMac computer (1998) revived the company’s flagging fortunes. Under Jobs’s guidance, Apple became an industry leader and one of the most valuable companies in the world. Its other notable products include iTunes (2001), the iPod (2001), the iPhone (2007), and the iPad (2010). In 2003 Jobs was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and he subsequently took several medical leaves of absence. In 2011 he resigned as CEO of Apple but became chairman.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Steve Jobs (born February 24, 1955, San Francisco, California, U.S.—died October 5, 2011, Palo Alto, California) was the cofounder of Apple Computer, Inc. (now Apple Inc.), and a charismatic pioneer of the personal computer era.

Steven Paul Jobs (February 24, 1955 – October 5, 2011) was an American businessman, inventor, and investor best known for co-founding the technology company Apple Inc. Jobs was also the founder of NeXT and chairman and majority shareholder of Pixar.

4.7 24,965 ratings. Editors' pick Best Biographies & Memoirs. See all formats and editions. Walter Isaacson’s “enthralling” (The New Yorker) worldwide bestselling biography of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs.

Steve Jobs (February 24, 1955–October 5, 2011) is best remembered as the co-founder of Apple Computers. He teamed up with inventor Steve Wozniak to create one of the first ready-made PCs. Besides his legacy with Apple, Jobs was also a smart businessman who became a multimillionaire before the age of 30.

Steve Jobs (Feb 24, 1955 – October 5, 2011) was an American businessman and inventor who played a key role in the success of Apple computers and the development of revolutionary new technology such as the iPod, iPad and MacBook. Early Life.

Let's get back to Terry’s 2011 interview with Walter Isaacson, author of the best-selling biography of Steve Jobs. A new movie based on his book, with a screenplay by Aaron Sorkin, opens...

Steve Jobs. Producer: Toy Story. Steven Paul Jobs was born on 24 February 1955 in San Francisco, California, to students Abdul Fattah Jandali and Joanne Carole Schieble who were unmarried at the time and gave him up for adoption.

Walter Isaacson's biography of Apple co-founder Steve Jobs was published Monday, less than three weeks after Job's death on Oct. 5.

Steve Jobs, (born Feb. 24, 1955, San Francisco, Calif., U.S.—died Oct. 5, 2011, Palo Alto, Calif.), U.S. businessman. Adopted in infancy, he grew up in Cupertino, Calif. He dropped out of Reed College and went to work for Atari Corp. designing video games. In 1976 he cofounded (with Stephen Wozniak) Apple Computer (incorporated in 1977; now ...