- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

A Plus Topper

Improve your Grades

Discrimination Essay | Essay on Discrimination for Students and Children in English

February 13, 2024 by Prasanna

Discrimination Essay: According to the Oxford dictionary, discrimination is the practice of treating an individual or a particular group in society unfairly than others based on age, race, sex, religion, finance, etc.

Throughout history, we have seen discrimination tainting every society and nation. This essay examines and analyses the causes and effects of discrimination in various forms on an individual, society, or nation.

You can also find more Essay Writing articles on events, persons, sports, technology and many more.

Long and Short Essays on Discrimination for Students and Kids in English

We provide children and students with essay samples on a long essay of 500 words and a short essay of 150 words on the topic “Discrimination” for reference.

Long Essay on Discrimination 500 Words in English

Long Essay on Discrimination is usually given to classes 7, 8, 9, and 10.

Our world has always been parted into two groups: victims of discrimination and those who discriminate against the former. The definition of discrimination denies opportunity or equal rights to a specific group of people that may be differentiated based on their religion, skin colour, or gender.

However, discrimination could be confused with prejudice and stereotype. Stereotypes are mental images we have on a particular group of people because of their religion, culture, or gender. Prejudice stems from stereotypes. It’s the act of judging by popular stereotypes.

Discrimination Is a mix of both with the addition of oppression and unfair treatment towards the deemed ‘inferior’ group or individual. Keep in mind that prejudice is a result of attitude, and discrimination results from an action.

Human history is saturated with acts of discrimination. It takes different forms, and modern society is not an exception. It is at the stake of cultural history and has influenced many social, cultural, and economic occurrences that we see today.

One of the most common forms being discrimination based on the financial background of an individual. The world is divided. The oppressive rich and powerful one’s greed to earn more and frowns upon the one who doesn’t have it all while the poor struggles to survive.

When we come across racial discrimination or racism, globally, we see acts of violence and unfair treatment done against people of colour, usually against people who aren’t Caucasian or commonly termed ‘white’ in appearance.

You can now access more Essay Writing on this topic and many more.

This form of oppression started when European countries started colonizing lands outside Europe in the 1600s and claiming them to be superior. Sadly, racism is still prevalent in the modern world, where a person’s ethnicity derives them from equal rights and opportunities.

In the history of humanity, we have come across several gruesome acts of discrimination. One of them being the mass genocide of Jews living in Europe, led by the Nazis and their leader Hitler, during the 2nd world war. We still see acts of systemic racism in countries all across the group.

Sexism has also been a significant issue over the centuries. Women face discrimination and double standards in their homes and their workplaces. Here we see women being oppressed, abused, and mistreated by men. Sexism resides in every society worldwide, blocking women from attaining every other right that a man gets to enjoy.

We also see people getting discriminated against for their sexual orientation. Homophobia and transphobia are what every queer has to go through living in today’s society. They get judged, oppressed, threatened, and even illegalized just for being who they are.

Another form of discrimination that’s primarily affecting the world today is discrimination based on religion. Today’s world is so divided that one wrong act from a community will form a lousy rep around the group.

A country like India, which is constitutionally secular, is now fragmented because of fights struck against religious minorities. In America, after the 9/11 massacre struck, people developed this strange stereotype and hatred towards people who follow Islam, also known as Islamophobia.

To sum it up, discrimination forms a menace to society and the person who has to face such an adverse treatment as it is a straight denial of the equal worth of the victim. It is a violation of an individual’s identity.

Short Essay on Discrimination 150 Words in English

Short Essay on Discrimination is usually given to classes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Discrimination is as common and abundant as corruption in politics and pollution in the air. Every type of discrimination implicates the superiority of a specific group of people over another group of people.

In today’s world, we see several forms of discrimination: gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, age, education, finance, workplace hierarchy, disabilities, etc. All of these arises from prolonged superiority complex, ignorance, and indifference to people’s identity.

The world we live in now faces significant issues like racism, sexism, homophobia, and Islamophobia. All these issues pile up to build a society filled with injustice, inequality, and in general toxic.

We study all the gruesome and bloody acts and events that have stained humankind all because of discrimination in history. Nowadays, these acts of discrimination are getting recognized and being called out, but it’s far from getting eradicated.

The government should form laws to avoid it; parents and schools should educate children on equality. The fight against discrimination is a long and hard one, but we have to continue fighting this social evil.

10 Lines on Discrimination Essay in English

1. Discrimination is an act when a person is treated unequally and differently. 2. Stereotype and prejudice are not discrimination. They are a part of the discrimination spectrum. 3. Particular forms of discrimination are also punishable by law. 4. Discrimination is of many types—racism, sexism, homophobia, etc. 5. Two anti-discrimination movements around the world are- ‘Me Too’ movement (a feminist movement / a protest against sexism) and the ‘Black Lives Matter’ Movement (protest against racism and systemic racism. 6. On 1st March every year, the Zero Discrimination Day is celebrated. 7. On 1st March 2014, The United Nations, along with UNAIDS, celebrated this day for the first time. 8. This day generally focuses on no discrimination despite having different gender, sex, ethnicity, and physical disability. 9. Any form of discrimination violates human rights. 10. Acts of discrimination are deeply rooted in our society, and we have to get rid of it.

FAQ’s on Discrimination Essay

Question 1. What is Discrimination?

Answer: Discrimination is an act of making unjustified distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong.

Question 2. What are the four main types of discrimination?

Answer: There are four main types of discrimination– direct discrimination and indirect discrimination, harassment, and victimization.

Question 3. What is the cause of discrimination?

Answer: All forms of discrimination are prejudice based on identity concepts and the need to identify with a certain group. This can lead to division, hatred, and even the dehumanization of other people because they have different identities.

Question 4. What kind of discrimination is illegal?

Answer: Employers can’t discriminate based on race, colour, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, age (40 and older), disability, or national origin.

- Picture Dictionary

- English Speech

- English Slogans

- English Letter Writing

- English Essay Writing

- English Textbook Answers

- Types of Certificates

- ICSE Solutions

- Selina ICSE Solutions

- ML Aggarwal Solutions

- HSSLive Plus One

- HSSLive Plus Two

- Kerala SSLC

- Distance Education

Racism: A Cause and Effect Essay Sample

Talking about the widespread topic of racism, there is a need to involve an official word that is referred to in many essays. It states: Racism is the process by which systems, policies, and attitudes create inequitable opportunities and outcomes for people based on race. Racism is more than just prejudice in thought or action. It occurs when it – whether individual or institutional – is accompanied by the power to discriminate against, oppress, or limit the civil rights of others.

The essence of racism is in the interpretation of differences as natural, as well as in establishing the connection between difference and domination. Racism first interprets differences as “natural” and then links them to existing relations of domination. Groups that are higher than others in the hierarchy are thereby “natural” right of superiority. Describing racism with the help of the cause and effect of racism essay is a brilliant idea. Get sure of it yourself by reading further!

If you need more in-deep research on a similar subject, feel free to use Edusson’s professional custom essay writing help . Racism is a scourge that has been present in societies around the world since antiquity, and it is still present today. Despite many efforts to eradicate it, its effects still remain, which is why it is necessary to understand the cause and effects of racism in order to combat it. This can help you with homework if you’re writing a racism cause and effect essay, as understanding the causes of racism can help you determine the most effective solutions for its eradication.

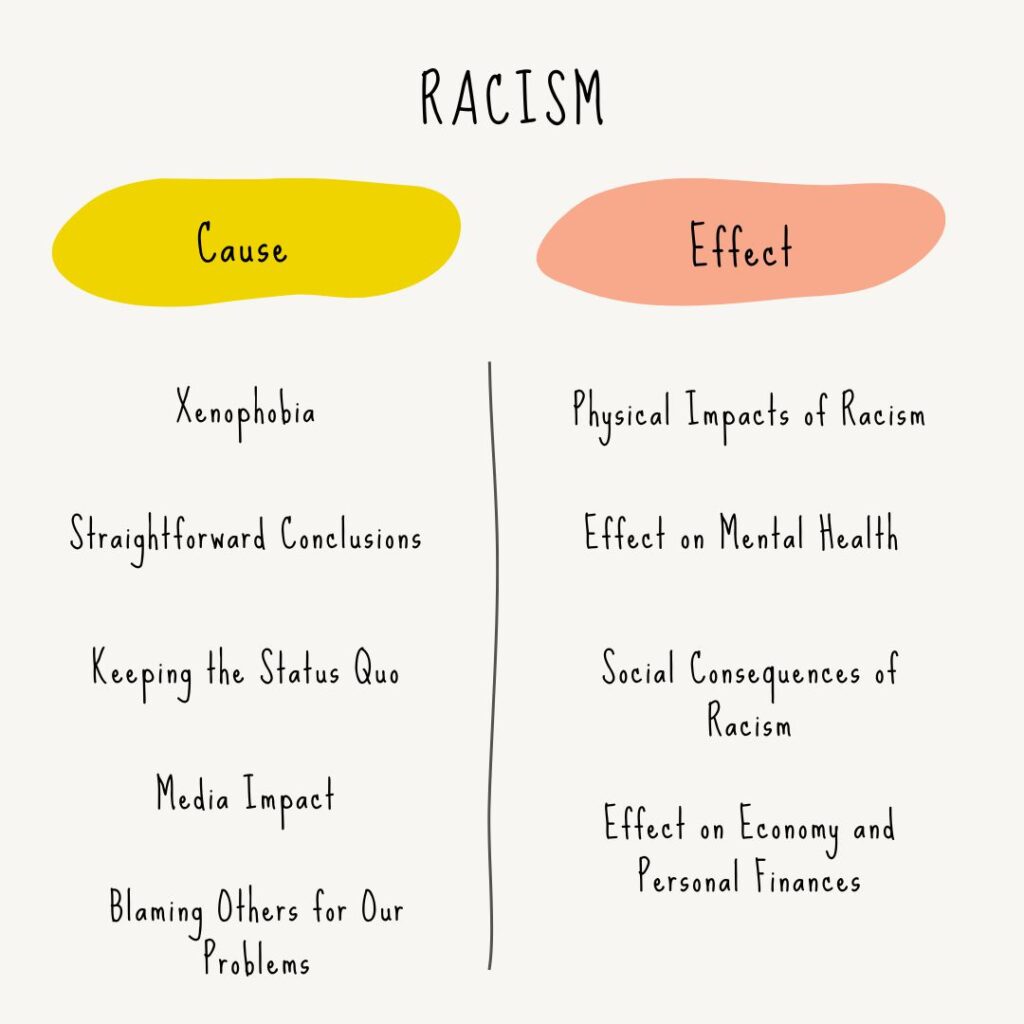

Cause and Effect of Racism

The phenomenon of modern racism is neither a recent invention of history nor purely European and was actively developing in the United States. As a form of xenophobia, racism has been inherent in people since ancient times. Racism has its own forms in different countries because of specific features: historical, cultural, and other factors. Use this cause and effect essay writing example to get information through the essays on how slavery causes racism, and racial discrimination in general: what causes racism, the effects of racism, and how African-Americans lives were neglected throughout history.

Cause 1 – Xenophobia

The leading cause of racism as a phenomenon is stated to be xenophobia. This topic is greatly researched in related books or different scientific essays and works. Racism is, to a large extent, xenophobia based on the visible difference in appearance. As a type of xenophobia, racism is an irrational but natural reaction of people to the foreign and unknown. However, racism is by no means exhausted by xenophobia alone. The level of rejection and intolerance in society directly depends on the development of a particular country. In the most developed countries, where the intellectual level of the population allows rejecting stupid superstitions about the differences between people, xenophobic attitudes are separate cases and take place as an exception.

Cause 2 – Straightforward Conclusions

Another cause of racial inequality is the destructive ability of many people to jump to quick conclusions, especially judging others because of their appearance, apparel, speech, and other visible traits. Mainly, it intensifies that because of the media representations of races, creating specific racial beliefs. Such cliches aren’t always harmful, like how Asian people are stereotyped as intelligent. But in the minds of undereducated people, quick judgments can play a bad thing and significantly influence how people are perceived.

Finished papers

Customer reviews

Cause 3 – Keeping the Status Quo

Keeping the status quo means, in simple words, the desire to keep the peace, avoid conflicts and clashes, and maintain law and order. Research from viral essays shows that when people believe in racial ideas, e.g., that blacks are inherently more violent and dangerous – they aren’t disturbed by police brutality or mass incarceration. “Keeping the peace” becomes more important than justice and equality.

Cause 4 – Media Impact

How modern media (TV, music industry, cinematography, etc.) describes race has a big influence on society’s race perception. As far as the media shows us our culture from an exaggerated point of view, it keeps racial stereotypes alive and well and therefore fuels racism. Racism cases appear in the media in a very subtle manner, without negative intent, but unfortunately, work the opposite. The most common thing for American society in this matter is representing a black person as a perpetrator of violent crimes or giving examples of stories related to theft and poverty. Such generalizations have a bad influence on society, as the perception of specific circles of people is formed according to the wrong representation.

Cause 5 – Blaming Others for Our Problems

Last but not least, the subjective reason for racism is that we blame others for our problems. When individuals feel mad or miserable, they often want to shift the problem to someone else’s shoulders and blame anyone but them for their problems. As a society, we act the same. Members of each race who look or behave differently from us are easy targets. You should have heard phrases like ‘Mexicans take all our workplaces’. This statement is absolutely false, though it sounds like a perfect justification for those who cannot find a job for a while and feel anger which translates to insecure people.

Writing essays on such a topic is challenging and demands a good understanding of a problem and statement of thought. If you like the structure of this article, check other cause and effect essay ideas to develop the skill of writing qualitative essays. The main part – the effects of racism – is ahead. Keep reading!

Racism and Its Effects

Racism and its effects can appear in different ways. There are many essays by the victims, who were either facing racism on a daily basis or had a frightening experience once in a lifetime. We have highlighted 5 effects of racism.

Physical Impacts of Racism

The physical threat is among the worst effects of racism. If an individual ever becomes a victim of racist aggression, he could have serious physical injuries that can end up with a disability, which in fact, is a common thing. This is a superior case of all the spectrum of racial issues today, because views, roles in society, or simply belonging to different races cannot be the causes of racism.

Effect on Mental Health

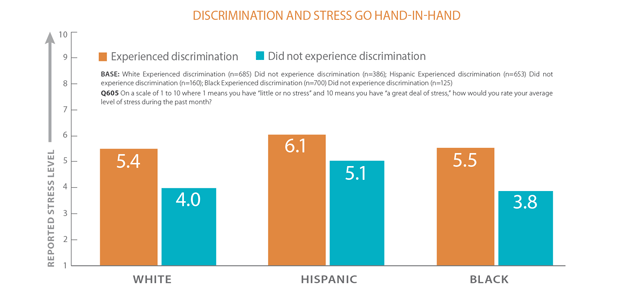

As we can see from the previous paragraph, racism can have a deeply no good effect on people’s mental health and health commonly. Experiencing discrimination can lead to feelings of humiliation when others make you feel like you are less worthy. Racism can sabotage people’s dignity, forcing them to adjust their usual behavior to the norms of another group of people who consider themselves better or higher. Such effects of racism lead from infrequent situations to changing whole daily routines ( for example, bypassing particular places or skipping activities, being afraid of leaving the house or traveling alone, changing clothes, etc. ). It can also lead to other emotional impacts such as distress, PTSD, insomnia, depression, fear, a sense of isolation, and a lack of trust in people.

When a person gets into a stressful situation, his body prepares to respond. The heart begins to beat faster, blood pressure rises, and breathing quickens as the body releases stress hormones. It is a natural way of preparing the body to deal with stress. But when a stressor, such as structural racism, never goes away, the body can remain in that tense state.

Social Consequences of Racism

Handling racism can lead to feeling inferior, isolated, of less worth, and even having questions about own existence in this world. Such an effect of racism – having less trust in other people – explains the reasons why African-Americans feel so insecure in any social circle where some whites belong too. So, if a person faces repeated harassment in any form, like skin color racism in schools, it can affect their social circles and add more challenges to it. Such an issue can prevent us from building a circle of friends or settling down for a family. Other effects of racism are institutional racism (where all of the ongoing advantages are given to white people) and housing discrimination can also create obstacles to free and healthy life in society.

Effect on Economy and Personal Finances

Discrimination has financial consequences too. It has been proved that people encountering racism tend to face obstacles to employment, fair payment levels, and discrimination when trying to access housing or financial help, especially with a child today. The same thing with discrimination from landlords and an issue with transportation. Many people who can be discriminated against by any visual sign tend to avoid public places or take walks to get places due to frequent incidents in transport, which affect their financial status too. Racial discrimination hurts those it affects. It also costs money. A recent study estimated the economic influence of racism at nearly $2 trillion a year in the United States alone.

How Does Racism Affect Families, Communities, and Society?

Racial belief can have a no good influence not only on a person who directly experienced it but also on his family, the community, or even the whole world. Racism cases lead to anxiety and stress spreading through the community every day, especially when there is no good response from the leaders or local people. And sometimes, even governmental structures stop defending the civil rights of African Americans in favor of other time-consuming questions. As a result, people in communities that have gotten used to being held together can become isolated and torn apart. Such a break of social bounds can more likely lead to criminal actions than racial differences.

To understand the white American racial theories, there should be solid essays review on the topic. And even after that, you will probably decide on the side of equal rights of all people independently on any features.

Racism has become one of the most burning social issues of our time, so it’s often the topic of discussion in educational institutions. As a result, more and more students have to write a college essay on racism, exploring its causes and effects. One of the most common sources of racism is a lack of understanding and communication between different cultural groups. To tackle this, it’s essential to have someone write a college essay that covers different perspectives on racism and helps to bridge the gap between different cultures and ethnic groups. To do this, many students find essay writers for hire to ensure their paper is well-written and engaging. Writing an essay about racism can be difficult, as there are many sensitive topics to address. It is important to be mindful when writing a racism cause and effect essay, as the writer must acknowledge all sides of the argument.

European Convention on Human Rights states: ‘The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in the Convention shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, color, language, religion, political or other opinions, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or another status.’ and these words seem to be right.

Related posts:

- The Great Gatsby (Analyze this Essay Online)

- Pollution Cause and Effect Essay Sample

- Essay Sample on How Can I Be a Good American

- The Power of Imaging: Why I am Passionate about Becoming a Sonographer

Improve your writing with our guides

Youth Culture Essay Prompt and Discussion

Why Should College Athletes Be Paid, Essay Sample

Reasons Why Minimum Wage Should Be Raised Essay: Benefits for Workers, Society, and The Economy

Get 15% off your first order with edusson.

Connect with a professional writer within minutes by placing your first order. No matter the subject, difficulty, academic level or document type, our writers have the skills to complete it.

100% privacy. No spam ever.

Main Causes of Discrimination

This essay will examine the root causes of discrimination in society. It will explore various factors such as societal norms, historical prejudices, lack of education, and fear of the unknown that contribute to discriminatory attitudes and behaviors. The piece will discuss how these causes manifest in different forms of discrimination like racial, gender, and age discrimination, and their impact on individuals and communities. PapersOwl showcases more free essays that are examples of Discrimination.

How it works

To the extent verifiable records appear, no general public or country has been insusceptible to discrimination, either as a victim or victimizer. Most of the causes of that discrimination and racism is given by fear of difference, through ignorance, and because people strive to show that they are stronger. Contemporary types of segregation go back to when European colonizers infiltrated and changed recently disengaged social orders and people groups. The more outrageous types of biased practices incorporate slavery, genocide, and prejudicial migration laws.

Less extraordinary types of preference and discrimination, however all things considered inescapable and onerous, incorporate social rejection at the institutional dimension, (in schools and hospitals), and the more unobtrusive structures drilled by the media. A few gatherings seem to experience the ill effects of increasingly diligent types of segregation, for example, Jews (as in hostile to Semitism) and the Roma (a.k.a. Vagabonds), paying little respect to time and place.

At the point when there is no understanding or tuning in to other people, or tolerating that it’s ok to appear as something else, at that point segregation and bias can end up set up. Discrimination originates from ignorance and fear. It is powered by the unknown and is immediately changed by anxiety. “None of us likes being in the dark and not knowing something. It can lead to us feeling uncomfortable, nervous or anxious. But prejudice and discrimination are not caused by what happens outside of us. They are caused by how we see things (usually incorrectly), and what we say to ourselves, commonly referred to as self-talk, thoughts or beliefs” (Discrimination from Ignorance p 4-5). But, when we enable ourselves to be vexed, restless or furious in light of the fact that we don’t know something or misjudge things about another person, we build up a mentality of segregation or partiality.

Another cause of discrimination is the impact media and developing technology have on society.

You will find that most people have a fear of difference “Prejudice is an antipathy towards another person based upon pre-existing belief or opinion, resulting from some form of social categorisation or membership of a particular group. It relies upon a stereotypical characterisation, or generalisation, of others, which is not grounded in evidence or experience”(Cantle, p1). biased perspectives are not founded on same decisions and are characteristically vile. Now and again, the perspectives held about the individuals from another gathering are so misrepresented and misinterpreted that they turn out to be relatively ludicrous. Be that as it may, it is anything but difficult to expel them as the result of insensible and shut personalities as they can frequently be a piece of a social framework which makes a various leveled arrange, defending segregation so as to safeguard the situation of the predominant gathering.

Cite this page

Main Causes of Discrimination. (2020, May 10). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/main-causes-of-discrimination/

"Main Causes of Discrimination." PapersOwl.com , 10 May 2020, https://papersowl.com/examples/main-causes-of-discrimination/

PapersOwl.com. (2020). Main Causes of Discrimination . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/main-causes-of-discrimination/ [Accessed: 5 Oct. 2024]

"Main Causes of Discrimination." PapersOwl.com, May 10, 2020. Accessed October 5, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/main-causes-of-discrimination/

"Main Causes of Discrimination," PapersOwl.com , 10-May-2020. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/main-causes-of-discrimination/. [Accessed: 5-Oct-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2020). Main Causes of Discrimination . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/main-causes-of-discrimination/ [Accessed: 5-Oct-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Discrimination and Prejudice — Discrimination

Essays on Discrimination

Discrimination is a pervasive issue that affects individuals and groups across various aspects of society. When writing an essay on discrimination, it's important to choose a topic that is not only relevant but also thought-provoking. The right topic can make your essay more engaging and relevant, while the wrong topic can make it feel stale and unoriginal. Here is a list of discrimination essay topics categorized by different aspects of discrimination.

When choosing a discrimination essay topic, consider your interests, personal experiences, and the current social and political climate. It is essential to select a topic that is relevant and meaningful to you, as it will make the writing process more enjoyable and authentic. Additionally, think about the audience you are writing for and aim to select a topic that will engage and educate them.

List of Discrimination Essay Topics

Racial discrimination.

- The impact of racial profiling on minority communities

- The role of media in perpetuating racial stereotypes

- Exploring the concept of white privilege

- Racial discrimination in the workplace

- Colorism within communities of color

Gender Discrimination

- The effects of gender discrimination on women's mental health

- The gender pay gap and its implications

- The portrayal of gender in the media

- Challenges faced by transgender individuals in society

- The intersectionality of gender and race in discrimination

Sexual Orientation Discrimination

- The impact of conversion therapy on LGBTQ+ individuals

- Discrimination against same-sex couples in adoption and parenting

- Homophobia and transphobia in sports

- The portrayal of LGBTQ+ individuals in popular culture

- The impact of religious beliefs on LGBTQ+ discrimination

Disability Discrimination

- Accessibility challenges faced by individuals with disabilities

- The stigmatization of mental health conditions

- The portrayal of disabilities in the media

- The impact of ableism in the workplace

- The intersectionality of race and disability in discrimination

Age Discrimination

- The discrimination faced by older adults in the workforce

- The portrayal of aging in popular culture

- Ageism in healthcare and medical treatment

- The impact of age discrimination on mental health

- Challenges faced by young individuals in a society focused on age

Writing about discrimination is an important task, as it helps raise awareness of various forms of discrimination and promotes understanding and equality. The topic you choose can help you address specific issues and explore different perspectives, making your essay more impactful and thought-provoking. Therefore, it is crucial to select a topic that resonates with you and has the potential to spark meaningful discussions.

These are just a few examples of discrimination essay topics to consider. When choosing a topic, remember to research and gather information from reputable sources to support your arguments. By selecting a compelling and relevant topic, you can create an impactful and thought-provoking essay that contributes to the ongoing dialogue on discrimination.

Alzheimer's Disease: a Student Perspective

The scholarship jacket: a symbol of inequality and discrimination, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Exploring Discourse Communities: a Student's Perspective

The history of discrimination in america, the hidden impact of internalized racism on psychology and society, the issue of employment discrimination in america, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Race Discrimination System in The Workplace

The discrimination and bigotry faced by the lgbtq society, racism and discrimination in the shining country - america, discrimination african-americans in i have a dream, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The Civil Rights Movement and African American Discriminations

Gender and racial discrimination on example of "hidden figures" & "the hate u give", the problem of hatred, racism, and discrimination in america, the root of racial discrimination in society, modern examples of discrimination and possible solutions, gender discrimination in society and its possible solutions, analysis of the problems faced by intersectional people, racism in the united states of america, rosa parks' fight for women's rights and social justice, the problem of women sexism in advertising, the role of stereotypes, racism, and hate nowadays, police brutality and partiality toward african americans, racial tendencies existing in our world and their impact on minorities, example of discrimsnation in the hate u give, gender and race based income inequality and its impacts on people, oppression of minorities in modern society, fight against affirmative action: pros and cons, the rising issue of discrimination against asian american, gender prejudice and discrimination in workplace, the discrimination of asian american on the government level.

Discrimination is the intended or accomplished differential treatment of persons or social groups for reasons of certain generalized traits.

People may be discriminated on the basis of age, caste, disability, language, name, nationality, race or ethnicity, region, religious beliefs, sex, sex characteristics, gender, and gender identity, sexual orientation. There is also reverse discrimination, which is a discrimination against members of a dominant or majority group, in favor of members of a minority or historically disadvantaged group.

Racism, sexism, anti-Semitism, homophobia, transphobia, or cissexism (discrimination against transgender persons), classism (discrimination based on social class), lookism (discrimination based on physical appearance), and ableism (discrimination based on disability).

Nearly half (45%) of African Americans experienced racial discrimination when trying to rent an apartment or buy a home. Nearly 1 in 5 Latinos have avoided medical care due to concern of being discriminated against or treated poorly. 34% of LGBTQ Americans say they that they or a friend have been verbally harassed while using the restroom. 41% of women report being discriminated against in equal pay and promotion opportunities.

Relevant topics

- Racial Profiling

- Illegal Immigration

- Gun Control

- I Have a Dream

- Gun Violence

- Death Penalty

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Bibliography

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

10 Causes of Gender Inequality

Over the years, the world has gotten closer to achieving gender equality. There is better representation of women in politics, more economic opportunities, and better healthcare in many places of the world. However, the World Economic Forum estimates it will take another century before true gender equality becomes a reality. What drives the gap between genders? Here are 10 causes of gender inequality:

#1. Uneven access to education

Around the world, women still have less access to education than men. ¼ of young women between 15-24 will not finish primary school . That group makes up 58% of the people not completing that basic education. Of all the illiterate people in the world, ⅔ are women. When girls are not educated on the same level as boys, it has a huge effect on their future and the kinds of opportunities they’ll get.

#2. Lack of employment equality

Only 6 countries in the world give women the same legal work rights as men. In fact, most economies give women only ¾ the rights of men. Studies show that if employment became a more even playing field, it has a positive domino effect on other areas prone to gender inequality.

#3. Job segregation

One of the causes for gender inequality within employment is the division of jobs. In most societies, there’s an inherent belief that men are simply better equipped to handle certain jobs. Most of the time, those are the jobs that pay the best. This discrimination results in lower income for women. Women also take on the primary responsibility for unpaid labor, so even as they participate in the paid workforce, they have extra work that never gets recognized financially.

#4. Lack of legal protections

According to research from the World Bank , over one billion women don’t have legal protection against domestic sexual violence or domestic economic violence. Both have a significant impact on women’s ability to thrive and live in freedom. In many countries, there’s also a lack of legal protections against harassment in the workplace, at school, and in public. These places become unsafe and without protection, women frequently have to make decisions that compromise and limit their goals.

#5. Lack of bodily autonomy

Many women around the world do not have authority over their own bodies or when they become parents. Accessing birth control is frequently very difficult. According to the World Health Organization , over 200 million women who don’t want to get pregnant are not using contraception. There are various reasons for this such as a lack of options, limited access, and cultural/religious opposition. On a global scale, about 40% of pregnancies are not planned and while 50% of them do end in abortion, 38% result in births. These mothers often become financially dependent on another person or the state, losing their freedom.

#6. Poor medical care

In addition to limited access to contraception, women overall receive lower-quality medical care than men. This is linked to other gender inequality reasons such as a lack of education and job opportunities, which results in more women being in poverty. They are less likely to be able to afford good healthcare. There’s also been less research into diseases that affect women more than men, such as autoimmune disorders and chronic pain conditions. Many women also experience discrimination and dismissal from their doctors, broadening the gender gap in healthcare quality.

#7. Lack of religious freedom

When religious freedom is attacked, women suffer the most. According to the World Economic Forum , when extremist ideologies (such as ISIS) come into a community and restrict religious freedom, gender inequality gets worse. In a study performed by Georgetown University and Brigham Young University, researchers were also able to connect religious intolerance with women’s ability to participate in the economy. When there’s more religious freedom, an economy becomes more stable thanks to women’s participation.

#8. Lack of political representation

Of all national parliaments at the beginning of 2019, only 24.3% of seats were filled by women. As of June of 2019, 11 Heads of State were women. Despite progress in this area over the years, women are still grossly underrepresented in government and the political process. This means that certain issues that female politicians tend to bring up – such as parental leave and childcare, pensions, gender equality laws and gender-based violence – are often neglected.

It would be impossible to talk about gender inequality without talking about racism. It affects what jobs women of color are able to get and how much they’re paid, as well as how they are viewed by legal and healthcare systems. Gender inequality and racism have been closely-linked for a long time. According to Sally Kitch, a professor and author, European settlers in Virginia decided what work could be taxed based on the race of the woman performing the work. African women’s work was “labor,” so it was taxable, while work performed by English women was “domestic” and not taxable. The pay gaps between white women and women of color continues that legacy of discrimination and contributes to gender inequality.

#10. Societal mindsets

It’s less tangible than some of the other causes on this list, but the overall mindset of a society has a significant impact on gender inequality. How society determines the differences and value of men vs. women plays a starring role in every arena, whether it’s employment or the legal system or healthcare. Beliefs about gender run deep and even though progress can be made through laws and structural changes, there’s often a pushback following times of major change. It’s also common for everyone (men and women) to ignore other areas of gender inequality when there’s progress, such as better representation for women in leadership . These types of mindsets prop up gender inequality and delay significant change.

Related: Take a free course on Gender Equality

You may also like

13 Ways Inequality Affects Society

15 Inspiring Quotes for Transgender Day of Visibility

Freedom of Expression 101: Definition, Examples, Limitations

15 Trusted Charities Addressing Child Poverty

12 Trusted Charities Advancing Women’s Rights

13 Facts about Child Labor

Environmental Racism 101: Definition, Examples, Ways to Take Action

11 Examples of Systemic Injustices in the US

Women’s Rights 101: History, Examples, Activists

What is Social Activism?

15 Inspiring Movies about Activism

15 Examples of Civil Disobedience

About the author, emmaline soken-huberty.

Emmaline Soken-Huberty is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. She started to become interested in human rights while attending college, eventually getting a concentration in human rights and humanitarianism. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and climate change are of special concern to her. In her spare time, she can be found reading or enjoying Oregon’s natural beauty with her husband and dog.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Sociology of Discrimination: Racial Discrimination in Employment, Housing, Credit, and Consumer Markets

Persistent racial inequality in employment, housing, and a wide range of other social domains has renewed interest in the possible role of discrimination. And yet, unlike in the pre–civil rights era, when racial prejudice and discrimination were overt and widespread, today discrimination is less readily identifiable, posing problems for social scientific conceptualization and measurement. This article reviews the relevant literature on discrimination, with an emphasis on racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit markets, and consumer interactions. We begin by defining discrimination and discussing relevant methods of measurement. We then provide an overview of major findings from studies of discrimination in each of the four domains; and, finally, we turn to a discussion of the individual, organizational, and structural mechanisms that may underlie contemporary forms of discrimination. This discussion seeks to orient readers to some of the key debates in the study of discrimination and to provide a roadmap for those interested in building upon this long and important line of research.

Persistent racial inequality in employment, housing, and other social domains has renewed interest in the possible role of discrimination. Contemporary forms of discrimination, however, are often subtle and covert, posing problems for social scientific conceptualization and measurement. This article reviews the relevant literature on racial discrimination, providing a roadmap for scholars who wish to build on this rich and important tradition. The charge for this article was a focus on racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit markets, and consumer interactions, but many of the arguments reviewed here may also extend to other domains (e.g., education, health care, the criminal justice system) and to other types of discrimination (e.g., gender, age, sexual orientation). We begin this discussion by defining discrimination and discussing methods for measuring discrimination. We then provide an overview of major findings from studies of discrimination in employment, housing, and credit and consumer markets. Finally, we turn to a discussion of the individual, organizational, and structural mechanisms that may underlie contemporary forms of discrimination.

WHAT IS DISCRIMINATION?

According to its most simple definition, racial discrimination refers to unequal treatment of persons or groups on the basis of their race or ethnicity. In defining racial discrimination, many scholars and legal advocates distinguish between differential treatment and disparate impact, creating a two-part definition: Differential treatment occurs when individuals are treated unequally because of their race. Disparate impact occurs when individuals are treated equally according to a given set of rules and procedures but when the latter are constructed in ways that favor members of one group over another ( Reskin 1998 , p. 32; National Research Council 2004 , pp. 39–40). The second component of this definition broadens its scope to include decisions and processes that may not themselves have any explicit racial content but that have the consequence of producing or reinforcing racial disadvantage. Beyond more conventional forms of individual discrimination, institutional processes such as these are important to consider in assessing how valued opportunities are structured by race.

A key feature of any definition of discrimination is its focus on behavior. Discrimination is distinct from racial prejudice (attitudes), racial stereotypes (beliefs), and racism (ideologies) that may also be associated with racial disadvantage (see Quillian 2006 ). Discrimination may be motivated by prejudice, stereotypes, or racism, but the definition of discrimination does not presume any unique underlying cause.

HOW CAN WE MEASURE DISCRIMINATION?

More than a century of social science interest in the question of discrimination has resulted in numerous techniques to isolate and identify its presence and to document its effects ( National Research Council 2004 ). Although no method is without its limitations, together these techniques provide a range of perspectives that can help to inform our understanding of whether, how, and to what degree discrimination matters in the lives of contemporary American racial minorities.

Perceptions of Discrimination

Numerous surveys have asked African Americans and other racial minorities about their experiences with discrimination in the workplace, in their search for housing, and in other everyday social settings ( Schuman et al. 2001 ). One startling conclusion from this line of research is the frequency with which discrimination is reported. A 2001 survey, for example, found that more than one-third of blacks and nearly 20% of Hispanics and Asians reported that they had personally been passed over for a job or promotion because of their race or ethnicity ( Schiller 2004 ). A 1997 Gallup poll found that nearly half of all black respondents reported having experienced discrimination at least once in one of five common situations in the past month ( Gallup Organ. 1997 ). Further, the frequency with which discrimination is reported does not decline among those higher in the social hierarchy; in fact, middle-class blacks are as likely to perceive discrimination as are working-class blacks, if not more ( Feagin & Sikes 1994 , Kessler et al. 1990 ). Patterns of perceived discrimination are important findings in their own right, as research shows that those who perceive high levels of discrimination are more likely to experience depression, anxiety, and other negative health outcomes ( Kessler et al. 1990 ). Furthermore, perceived discrimination may lead to diminished effort or performance in education or the labor market, which itself gives rise to negative outcomes ( Ogbu 1991 ; Steele 1997 ; Loury 2002 , pp. 26–33). What remains unclear from this line of research, however, is to what extent perceptions of discrimination correspond to some reliable depiction of reality. Because events may be misperceived or overlooked, perceptions of discrimination may over- or underestimate the actual incidence of discrimination.

Reports by Potential Discriminators

Another line of social science research focuses on the attitudes and actions of dominant groups for insights into when and how racial considerations come into play. In addition to the long tradition of survey research on racial attitudes and stereotypes among the general population (cf. Schuman et al. 2001 , Farley et al. 1994 ), a number of researchers have developed interview techniques aimed at gauging propensities toward discrimination among employers and other gatekeepers. Harry Holzer has conducted a number of employer surveys in which employers are asked a series of questions about “the last worker hired for a noncollege job,” thereby grounding employers’ responses in a concrete recent experience (e.g., Holzer 1996 ). In this format, race is asked about as only one incidental characteristic in a larger series of questions concerning this recent employee, thereby reducing the social desirability bias often triggered when the subject of race is highlighted. Likewise, by focusing on a completed action, the researcher is able to document revealed preferences rather than expressed ones and to examine the range of employer, job, and labor market characteristics that may be associated with hiring decisions.

A second prominent approach to investigating racial discrimination in employment has relied on in-depth, in-person interviews, which can be effective in eliciting candid discussions about sensitive hiring issues. Kirschenman & Neckerman (1991) , for example, describe employers’ blatant admission of their avoidance of young, inner-city black men in their search for workers. Attributing characteristics such as “lazy” and “unreliable” to this group, the employers included in their study were candid in their expressions of strong racial preferences in considering low wage workers (p. 213; see also Wilson 1996 , Moss & Tilly 2001 ). These in-depth studies have been invaluable in providing detailed accounts of what goes through the minds of employers—at least consciously— as they evaluate members of different groups. However, we must keep in mind that racial attitudes are not always predictive of corresponding behavior ( LaPiere 1934 , Allport 1954 , Pager & Quillian 2005 ). Indeed, Moss & Tilly (2001) report the puzzling finding that “businesses where a plurality of managers complained about black motivation are more likely to hire black men” (p. 151). Hiring decisions (as with decisions to rent a home or approve a mortgage) are influenced by a complex range of factors, racial attitudes being only one. Where understanding persistent racial prejudice and stereotypes is surely an important goal in and of itself, this approach will not necessarily reveal the extent of discrimination in action.

Statistical Analyses

Perhaps the most common approach to studying discrimination is by investigating inequality in outcomes between groups. Rather than focusing on the attitudes or perceptions of actors that may be correlated with acts of discrimination, this approach looks to the possible consequences of discrimination in the unequal distribution of employment, housing, or other social and economic resources. Using large-scale datasets, researchers can identify systematic disparities between groups and chart their direction over time. Important patterns can also be detected through detailed and systematic case studies of individual firms, which often provide a richer array of indicators with which to assess patterns of discrimination (e.g., Castilla 2008 , Petersen & Saporta 2004 , Fernandez & Friedrich 2007 ).

Discrimination in statistical models is often measured as the residual race gap in any outcome that remains after controlling for all other race-related influences. Differences may be identified through the main effect of race, suggesting a direct effect of race on an outcome of interest, or through an interaction between race and one or more human capital characteristics, suggesting differential returns to human capital investments on the basis of race ( Oaxaca 1973 ; National Research Council 2004 , chapter 7). The main liability of this approach is that it is difficult to effectively account for the multitude of factors relevant to unequal outcomes, leaving open the possibility that the disparities we attribute to discrimination may in fact be explained by some other unmeasured cause(s). In statistical analyses of labor market outcomes, for example, even after controlling for standard human capital variables (e.g., education, work experience), a whole host of employment-related characteristics typically remain unaccounted for. Characteristics such as reliability, motivation, interpersonal skills, and punctuality, for example, are each important to finding and keeping a job, but these are characteristics that are often difficult to capture with survey data (see, for example, Farkas & Vicknair 1996 , Farkas 2003 ). Complicating matters further, some potential control variables may themselves be endogenous to the process under investigation. Models estimating credit discrimination, for example, typically include controls for asset accumulation and credit history, which may themselves be in part the byproduct of discrimination ( Yinger 1998 , pp. 26–27). Likewise, controls for work experience or firm tenure may be endogenous to the process of employment discrimination if minorities are excluded from those opportunities necessary to building stable work histories (see Tomaskovic-Devey et al. 2005 ). While statistical models represent an extremely important approach to the study of race differentials, researchers should use caution in making causal interpretations of the indirect measures of discrimination derived from residual estimates. For a more detailed discussion of the challenges and possibilities of statistical approaches to measuring discrimination, see the National Research Council (2004 , chapter 7).

Experimental Approaches to Measuring Discrimination

Experimental approaches to measuring discrimination excel in exactly those areas in which statistical analyses flounder. Experiments allow researchers to measure causal effects more directly by presenting carefully constructed and controlled comparisons. In a laboratory experiment by Dovidio & Gaertner (2000) , for example, subjects (undergraduate psychology students) took part in a simulated hiring experiment in which they were asked to evaluate the application materials for black and white job applicants of varying qualification levels. When applicants were either highly qualified or poorly qualified for the position, there was no evidence of discrimination. When applicants had acceptable but ambiguous qualifications, however, participants were nearly 70% more likely to recommend the white applicant than the black applicant (see also Biernat & Kobrynowicz’s 1997 discussion of shifting standards). 1

Although laboratory experiments offer some of the strongest evidence of causal relationships, we do not know the extent to which their findings relate to the kinds of decisions made in their social contexts—to hire, to rent, to move, for example—that are most relevant to understanding the forms of discrimination that produce meaningful social disparities. Seeking to bring more realism to the investigation, some researchers have moved experiments out of the laboratory and into the field. Field experiments offer a direct measure of discrimination in real-world contexts. In these experiments, typically referred to as audit studies, researchers carefully select, match, and train individuals (called testers) to play the part of a job/apartment-seeker or consumer. By presenting equally qualified individuals who differ only by race or ethnicity, researchers can assess the degree to which racial considerations affect access to opportunities. Audit studies have documented strong evidence of discrimination in the context of employment (for a review, see Pager 2007a ), housing searches ( Yinger 1995 ), car sales ( Ayres & Siegelman 1995 ), applications for insurance ( Wissoker et al. 1998 ), home mortgages ( Turner & Skidmore 1999 ), the provision of medical care ( Schulman et al. 1999 ), and even in hailing taxis ( Ridley et al. 1989 ).

Although experimental methods are appealing in their ability to isolate causal effects, they nevertheless suffer from some important limitations. Critiques of the audit methodology have focused on questions of internal validity (e.g., experimenter effects, the problems of effective tester matching), generalizability (e.g., the use of overqualified testers, the limited sampling frame for the selection of firms to be audited), and the ethics of audit research (see Heckman 1998 , Pager 2007a for a more extensive discussion of these issues). In addition, audit studies are often costly and difficult to implement and can only be used for selective decision points (e.g., hiring decisions but not training, promotion, termination, etc.).

Studies of Law and Legal Records

Since the civil rights era, legal definitions and accounts of discrimination have been central to both popular and scholarly understandings of discrimination. Accordingly, an additional window into the dynamics of discrimination involves the use of legal records from formal discrimination claims. Whether derived from claims to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the courts, or state-level Fair Employment/Fair Housing Bureaus, official records documenting claims of discrimination can provide unique insight into the patterns of discrimination and antidiscrimination enforcement in particular contexts and over time.

Roscigno (2007) , for example, analyzed thousands of “serious claims” filed with the Civil Rights Commission of Ohio related to both employment and housing discrimination. These claims document a range of discriminatory behaviors, from harassment, to exclusion, to more subtle forms of racial bias. [See also Harris et al. (2005) for a similar research design focusing on federal court claims of consumer discrimination.] Although studies relying on formal discrimination claims necessarily overlook those incidents that go unnoticed or unreported, these records provide a rare opportunity to witness detailed descriptions of discrimination events across a wide range of social domains not typically observed in conventional research designs.

Other studies use discrimination claims, not to assess patterns of discrimination, but to investigate trends in the application of antidiscrimination law. Nielsen & Nelson (2005) provide an overview of research in this area, examining the pathways by which potential claims (or perceived discrimination) develop into formal legal action, or conversely the many points at which potential claims are deflected from legal action. Hirsh & Kornrich (2008) examine how characteristics of the workplace and institutional environment affect variation in the incidence of discrimination claims and their verification by EEOC investigators. Donohue & Siegelman (1991 , 2005 ) analyze discrimination claims from 1970 through 1997 to chart changes in the nature of antidiscrimination enforcement over time. The overall volume of discrimination claims increased substantially over this period, though the composition of claims shifted away from an emphasis on racial discrimination toward a greater emphasis on gender and disability discrimination. Likewise, the types of employment discrimination claims have shifted from an emphasis on hiring discrimination to an overwhelming emphasis on wrongful termination, and class action suits have become increasingly rare. The authors interpret these trends not as indicators of changes in the actual distribution of discrimination events, but rather as reflections of the changing legal environment in which discrimination cases are pursued (including, for example, changes to civil rights law and changes in the receptivity of the courts to various types of discrimination claims), which themselves may have implications for the expression of discrimination ( Donohue & Siegelman 1991 , 2005 ).

Finally, a number of researchers have exploited changes in civil rights and antidiscrimination laws as a source of exogenous variation through which to measure changes in discrimination (see Holzer & Ludwig 2003 ). Freeman (1973 , see table 6 therein), for example, investigates the effectiveness of federal EEO laws by comparing the black-white income gap before and after passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Heckman & Payner (1989) use microdata from textile plants in South Carolina to study the effects of race on employment between 1940 and 1980, concluding that federal antidiscrimination policy resulted in a significant improvement in black economic status between 1965 and 1975. More recent studies exploiting changes in the legal context include Kelly & Dobbin (1998) , who examine the effects of changing enforcement regimes on employers’ implementation of diversity initiatives; Kalev & Dobbin (2006) , who examine the relative impact of compliance reviews and lawsuits on the representation of women and minorities in management positions; and a volume edited by Skrentny (2001) , which examines many of the complex and unexpected facets related to the rise, expansion, and impact of affirmative action and diversity policies in the United States and internationally.

Although no research method is without flaws, careful consideration of the range of methods available helps to match one’s research question with the appropriate empirical strategy. Comparisons across studies can help to shed light on the relative strengths and weaknesses of existing methodological approaches (see National Research Council 2004 ). At the same time, one must keep in mind that the nature of discrimination may itself be a moving target, with the forms and patterns of discrimination shifting over time and across domains (see Massey 2005 , p. 148). These complexities challenge our traditional modes of operationalization and encourage us to continue to update and refine our measures to allow for an adequate accounting of contemporary forms of racial discrimination.

IS DISCRIMINATION STILL A PROBLEM?

Simple as it may be, one basic question that preoccupies the contemporary literature on discrimination centers around its continuing relevance. Whereas 50 years ago acts of discrimination were overt and widespread, today it is harder to assess the degree to which everyday experiences and opportunities may be shaped by ongoing forms of discrimination. Indeed, the majority of white Americans believe that a black person today has the same chance at getting a job as an equally qualified white person, and only a third believe that discrimination is an important explanation for why blacks do worse than whites in income, housing, and jobs ( Pager 2007a ). Academic literature has likewise questioned the relevance of discrimination for modern-day outcomes, with the rising importance of skill, structural changes in the economy, and other nonracial factors accounting for increasing amounts of variance in individual outcomes ( Heckman 1998 , Wilson 1978 ). Indeed, discrimination is not the only nor even the most important factor shaping contemporary opportunities. Nevertheless, it is important to understand when and how discrimination does play a role in the allocation of resources and opportunities. In the following discussion, we examine the evidence of discrimination in four domains: employment, housing, credit markets, and consumer markets. Although not an exhaustive review of the literature, this discussion aims to identify the major findings and debates within each of these areas of research.

Although there have been some remarkable gains in the labor force status of racial minorities, significant disparities remain. African Americans are twice as likely to be unemployed as whites (Hispanics are only marginally so), and the wages of both blacks and Hispanics continue to lag well behind those of whites (author’s analysis of Current Population Survey, 2006). A long line of research has examined the degree to which discrimination plays a role in shaping contemporary labor market disparities.

Experimental audit studies focusing on hiring decisions have consistently found strong evidence of racial discrimination, with estimates of white preference ranging from 50% to 240% ( Cross et al. 1989 , Turner et al. 1991 , Fix & Struyk 1993 , Bendick et al. 1994 ; see Pager 2007a for a review). For example, in a study by Bertrand & Mullainathan (2004) , the researchers mailed equivalent resumes to employers in Boston and Chicago using racially identifiable names to signal race (for example, names like Jamal and Lakisha signaled African Americans, while Brad and Emily were associated with whites). 2 White names triggered a callback rate that was 50% higher than that of equally qualified black applicants. Further, their study indicated that improving the qualifications of applicants benefited white applicants but not blacks, thus leading to a wider racial gap in response rates for those with higher skill.

Statistical studies of employment outcomes likewise reveal large racial disparities unaccounted for by observed human capital characteristics. Tomaskovic-Devey et al. (2005) present evidence from a fixed-effects model indicating that black men spend significantly more time searching for work, acquire less work experience, and experience less stable employment than do whites with otherwise equivalent characteristics. Wilson et al. (1995) find that, controlling for age, education, urban location, and occupation, black male high school graduates are 70% more likely to experience involuntary unemployment than whites with similar characteristics and that this disparity increases among those with higher levels of education. At more aggregate levels, research points to the persistence of occupational segregation, with racial minorities concentrated in jobs with lower levels of stability and authority and with fewer opportunities for advancement ( Parcel & Mueller 1983 , Smith 2002 ). Of course, these residual estimates cannot control for all relevant factors, such as motivation, effort, access to useful social networks, and other factors that may produce disparities in the absence of direct discrimination. Nevertheless, these estimates suggest that blacks and whites with observably similar human capital characteristics experience markedly different employment outcomes.

Unlike the cases of hiring and employment, research on wage disparities comes to more mixed conclusions. An audit study by Bendick et al. (1994) finds that, among those testers who were given job offers, whites were offered wages that were on average 15 cents/hour higher than their equally qualified black test partners; audit studies in general, however, provide limited information on wages, as many testers never make it to the wage setting stage of the employment process. Some statistical evidence comes to similar conclusions. Cancio et al. (1996) , for example, find that, controlling for parental background, education, work experience, tenure, and training, white men earn roughly 15% more than comparable blacks (white women earned 6% more than comparable black women). Farkas & Vicknair (1996) , however, using a different dataset, find that the addition of controls for cognitive ability eliminates the racial wage gap for young black and white full-time workers. According to the authors, these findings suggest that racial differences in labor market outcomes are due more to factors that precede labor market entry (e.g., skill acquisition) rather than discrimination within the labor market (see also Neal & Johnson 1996 ).

Overall, then, the literature points toward consistent evidence of discrimination in access to employment, but less consistent evidence of discrimination in wages. Differing methodologies and/or model specification may account for some of the divergent results. But there is also reason to believe that the processes affecting access to employment (e.g., the influence of first impressions, the absence of more reliable information on prospective employees, and minimal legal oversight) may be more subject to discriminatory decision making than those affecting wages. Further, the findings regarding employment and wages may be in part causally related, as barriers to labor market entry will lead to a more select sample of black wage earners, reducing measured racial disparities (e.g., Western & Pettit 2005 ). These findings point to the importance of modeling discrimination as a process rather than a single-point outcome, with disparities in premarket skills acquisition, barriers to labor market entry, and wage differentials each part of a larger employment trajectory and shaped to differing degrees by discrimination.

Residential segregation by race remains a salient feature of contemporary American cities. Indeed, African Americans were as segregated from whites in 1990 as they had been at the start of the twentieth century, and levels of segregation appear unaffected by rising socioeconomic status ( Massey & Denton 1993 ). Although segregation appears to have modestly decreased between 1980 and 2000 ( Logan et al. 2004 ), blacks (and to a lesser extent other minority groups) continue to experience patterns of residential placement markedly different from whites. The degree to which discrimination contributes to racial disparities in housing has been a major preoccupation of social scientists and federal housing agents ( Charles 2003 ).

The vast majority of the work on discrimination in housing utilizes experimental audit data. For example, between 2000 and 2002 the Department of Housing and Urban Development conducted an extensive series of audits measuring housing discrimination against blacks, Latinos, Asians, and Native Americans, including nearly 5500 paired tests in nearly 30 metropolitan areas [see Turner et al. (2002) , Turner & Ross (2003a) ; see also Hakken (1979) , Feins & Bratt (1983) , Yinger (1986) , Roychoudhury & Goodman (1992 , 1996 ) for additional, single-city audits of housing discrimination]. The study results reveal bias across multiple dimensions, with blacks experiencing consistent adverse treatment in roughly one in five housing searches and Hispanics experiencing consistent adverse treatment in roughly one out of four housing searches (both rental and sales). 3 Measured discrimination took the form of less information offered about units, fewer opportunities to view units, and, in the case of home buyers, less assistance with financing and steering into less wealthy communities and neighborhoods with a higher proportion of minority residents.

Generally, the results of the 2000 Housing Discrimination Study indicate that aggregate levels of discrimination against blacks declined modestly in both rentals and sales since 1989 (although levels of racial steering increased). Discrimination against Hispanics in housing sales declined, although Hispanics experienced increasing levels of discrimination in rental markets.

Other research using telephone audits further points to a gender and class dimension of racial discrimination in which black women and/or blacks who speak in a manner associated with a lower-class upbringing suffer greater discrimination than black men and/or those signaling a middle-class upbringing ( Massey & Lundy 2001 , Purnell et al. 1999 ). Context also matters in the distribution of discrimination events ( Fischer & Massey 2004 ). Turner & Ross (2005) report that segregation and class steering of blacks occurs most often when either the housing or the office of the real estate agent is in a predominantly white neighborhood. Multi-city audits likewise suggest that the incidence of discrimination varies substantially across metropolitan contexts ( Turner et al. 2002 ).

Moving beyond evidence of exclusionary treatment, Roscigno and colleagues (2007) provide evidence of the various forms of housing discrimination that can extend well beyond the point of purchase (or rental agreement). Examples from a sample of discrimination claims filed with the Civil Rights Commission of Ohio point to the failure of landlords to provide adequate maintenance for housing units, to harassment or physical threats by managers or neighbors, and to the unequal enforcement of a residential association’s rules.

Overall, the available evidence suggests that discrimination in rental and housing markets remains pervasive. Although there are some promising signs of change, the frequency with which racial minorities experience differential treatment in housing searches suggests that discrimination remains an important barrier to residential opportunities. The implications of these trends for other forms of inequality (health, employment, wealth, and inheritance) are discussed below.

Credit Markets

Whites possess roughly 12 times the wealth of African Americans; in fact, whites near the bottom of the income distribution possess more wealth than blacks near the top of the income distribution ( Oliver & Shapiro 1997 , p. 86). Given that home ownership is one of the most significant sources of wealth accumulation, patterns that affect the value and viability of home ownership will have an impact on wealth disparities overall. Accordingly, the majority of work on discrimination in credit markets focuses on the specific case of mortgages.

Available evidence suggests that blacks and Hispanics face higher rejection rates and less favorable terms in securing mortgages than do whites with similar credit characteristics ( Ross & Yinger 1999 ). Oliver & Shapiro (1997 , p. 142) report that blacks pay more than 0.5% higher interest rates on home mortgages than do whites and that this difference persists with controls for income level, date of purchase, and age of buyer.

The most prominent study of the effect of race on rejection rates for mortgage loans is by Munnell et al. (1996) , which uses 1991 Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data supplemented by data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, including individual applicants’ financial, employment, and property background variables that lenders use to calculate the applicants’ probability of default. Accounting for a range of variables linked to risk of default, cost of default, loan characteristics, and personal and neighborhood characteristics, they find that black and Hispanic applications were 82% more likely to be rejected than were those from similar whites. Critics argued that the study was flawed on the basis of the quality of the data collected ( Horne 1994 ), model specification problems ( Glennon & Stengel 1994 ), omitted variables ( Zandi 1993 , Liebowitz 1993 , Horne 1994 , Day & Liebowitz 1996 ), and endogenous explanatory variables (see Ross & Yinger 1999 for a full explication of the opposition), although rejoinders suggest that the race results are affected little by these modifications ( Ross & Yinger 1999 ; S.L. Ross & G.M.B. Tootell, unpublished manuscript).

Audit research corroborates evidence of mortgage discrimination, finding that black testers are less likely to receive a quote for a loan than are white testers and that they are given less time with the loan officer, are quoted higher interest rates, and are given less coaching and less information than are comparable white applicants (for a review, see Ross & Yinger 2002 ).

In addition to investigating the race of the applicant, researchers have investigated the extent to which the race of the neighborhood affects lending decisions, otherwise known as redlining. Although redlining is a well-documented factor in the origins of contemporary racial residential segregation (see Massey & Denton 1993 ), studies after the 1974 Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which outlawed redlining, and since the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act, which made illegal having a smaller pool of mortgage funds available in minority neighborhoods than in similar white neighborhoods, find little evidence of its persistence ( Benston & Horsky 1991 , Schafer & Ladd 1981 , Munnell et al. 1996 ). This conclusion depends in part, however, on one’s definition of neighborhood-based discrimination. Ross & Yinger (1999) distinguish between process-based and outcome-based redlining, with process-based redlining referring to “whether the probability that a loan application is denied is higher in minority neighborhoods than in white neighborhoods, all else equal” whereas outcome-based redlining refers to smaller amounts of mortgage funding available to minority neighborhoods relative to comparable white neighborhoods. Although evidence on both types of redlining is mixed, several studies indicate that, controlling for demand, poor and/or minority neighborhoods have reduced access to mortgage funding, particularly from mainstream lenders ( Phillips-Patrick & Rossi 1996 , Siskin & Cupingood 1996 ; see also Ladd 1998 for methodological issues in measuring redlining).

As a final concern, competition and deregulation of the banking industry have led to greater variability in conditions of loans, prompting the label of the “new inequality” in lending ( Williams et al. 2005 , Holloway 1998 ). Rather than focusing on rejection rates, these researchers focus on the terms and conditions of loans, in particular whether a loan is favorable or subprime ( Williams et al. 2005 , Apgar & Calder 2005 , Squires 2003 ). Immergluck & Wiles (1999) have called this the “dual-mortgage market” in which prime lending is given to higher income and white areas, while subprime and predatory lending is concentrated in lower-income and minority communities (see also Dymski 2006 , pp. 232–36). Williams et al. (2005) , examining changes between 1993 and 2000, find rapid gains in loans to under-served markets from specialized lenders: 78% of the increase in lending to minority neighborhoods was from subprime lenders, and 72% of the increase in refinance lending to blacks was from subprime lenders. Further, the authors find that “even at the highest income level, blacks are almost three times as likely to get their loans from a subprime lender as are others” (p. 197; see also Calem et al. 2004 ). Although the disproportionate rise of subprime lending in minority communities is not solely the result of discrimination, some evidence suggests that in certain cases explicit racial targeting may be at work. In two audit studies in which creditworthy testers approached sub-prime lenders, whites were more likely to be referred to the lenders’ prime borrowing division than were similar black applicants (see Williams et al. 2005 ). Further, subprime lenders quoted the black applicants very high rates, fees, and closing costs that were not correlated with risk ( Williams et al. 2005 ). 4

Not all evidence associated with credit market discrimination is bad news. Indeed, between 1989 and 2000 the number of mortgage loans to blacks and Hispanics nationwide increased 60%, compared with 16% for whites, suggesting that some convergence is taking place ( Turner et al. 2002 ). Nevertheless, the evidence indicates that blacks and Hispanics continue to face higher rejection rates and receive less favorable terms than whites of equal credit risk. At the time of this writing, the U.S. housing market is witnessing high rates of loan defaults and foreclosures, resulting in large part from the rise in unregulated subprime lending; the consequences of these trends for deepening racial inequalities have yet to be fully explored.

Consumer Markets