“Girl, Woman, Other” Illuminates the Everyday Lives of Black British Women

Bernardine Evaristo’s Booker-winning novel is challenging the overall whiteness of the British canon

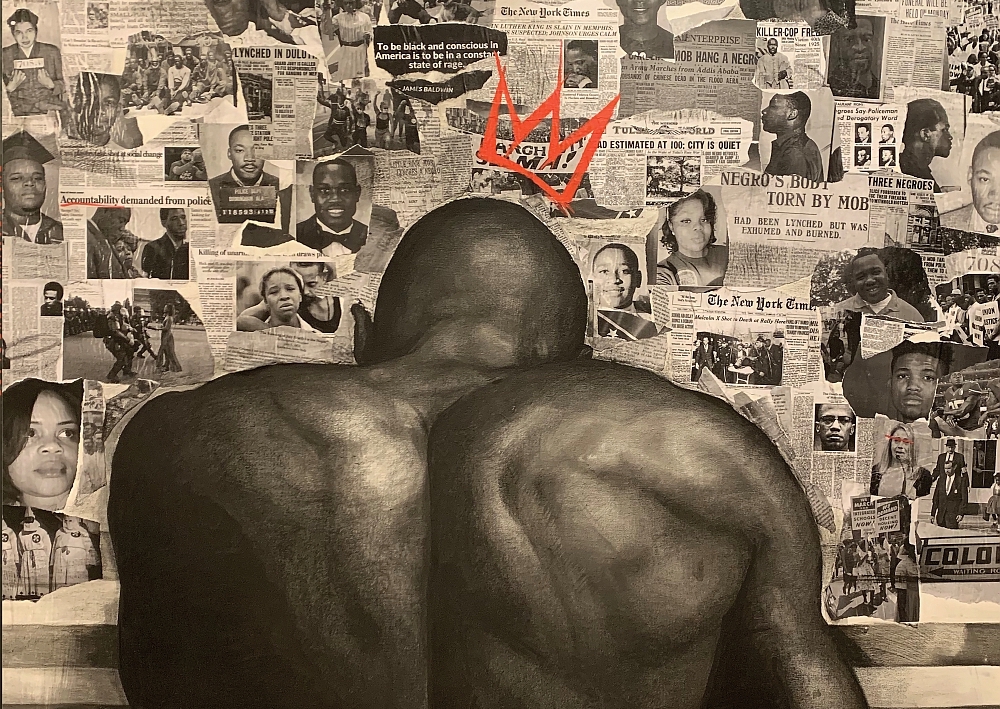

Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other depicts the complexities of identity through the interconnected stories of twelve Black British women, painting a portrait of the state of contemporary Britain that also examines the legacy of Britain’s colonial history in Africa and the Caribbean. Though Black women are not a monolith, there is something about the shared experience of a certain collection of people who identify together in gender-related experiences and the results of coming from places where colonialism—from the standpoint of the colonized and the colonizer—played an importance on how your skin color dictates how others treat you. For an African American woman who has read many British writers, reading Girl, Woman, Other was the first time I felt any affinity to such authors and their works.

It was not surprising to me that this book won the 2019 Booker Prize. Although what was surprising is that Bernardine Evaristo is the first Black woman to receive the literary honor. Professor of Creative Writing at Brunel University London, Evaristo has written eight books that cross multiple genres and styles. Evident in Girl, Woman, Othe r is Evaristo’s willingness to play with style, voice, and lyricism. I spoke with Evaristo with an “American Black woman interviews British Black woman” kind of vibe. We spoke about Girl, Woman, Other with the context of understanding it from and for a Black American reader, the similarities and differences between American and British Blackness and Black womanhood, specifically, and the depiction of such in literature.

Tyrese L Coleman: I loved this book so much and found it hard to put down. When I told a white woman I met that I would be interviewing you, she said to me that she was surprised you won the Booker Prize but when I read Girl, Woman, Other , I knew exactly why you won the Booker Prize. I also read where a BBC anchor referred to you as “another author ” when discussing the shared award with Margaret Atwood. Both incidents made me wonder whether or not you have noticed a racial and/or gender divide in the book’s criticism and, specifically, the reaction to you winning the award. If so, why do you think that is?

Bernardine Evaristo : I’m glad you enjoyed the novel so much. I’ve had very little feedback from individual American readers, mainly because the novel came out much later there. You don’t say whether the woman mentioned had read the novel or not—which makes a difference. People have opinions on the Booker Prize shortlists and winners without actually having read all the books. Or they’ve read one and decided that book is their favorite, without knowing anything about the competition. I’ve had incredibly positive responses from all kinds of readers to Girl, Woman, Other and since winning the Booker, the novel has gone out into the world to land in the laps of readers who wouldn’t usually read my work, even if they came across it. In the U.K. the main reading market is older and female, but since winning the prize my events have also been packed with men, often elderly men, some of whom have already read the book and loved it. I find this incredibly reassuring in the sense that they are responding to the humanity in my work and that they have encountered my twelve primarily Black British women and found them interesting and perhaps, even, relatable. We are all human beings, after all, with shared emotional drivers.

TLC: As an American who is slightly an anglophile (meaning, I watch a significant amount of British television and movies and am specifically obsessed with The Crown ), Girl, Woman, Other felt familiar to me. Not because of what I think I know about what it means to be English, but rather what I know about what it means to be a Black woman. I was drawn to those moments of knowing that feel unique to Black womanhood, such as Carole’s constant respectability performance as she is surrounded by white people daily, especially white men, and her struggle to outperform just to remain equal.

I find myself and I see other Black women always saying, “we aren’t a monolith,” but we do have shared and relatable experiences. What were you hoping to say about the shared experience of Black women?

BE : As Black women in the U.K. and U.S., we will share certain experiences in that we are living in societies where we are racialized and where women are also discriminated against. My novel explores many women, one of whom is non-binary, from multiple perspectives, and this includes experiences of queer and straight sexuality, different classes, occupations, family set-ups, and cultural backgrounds, migration histories, rural and metropolitan women, and women of every generation through to a nonagenarian, and so on. My aim was to create as many stories as I could about Black British women and in so doing to counteract our invisibility in literature to present my characters as complex, flawed, and very real beings. All of these areas lattice across the text, so that while the novel is specific to individual narratives, there are so many points of connection for the reader, especially for Black women readers, and women of color more generally.

TLC: What are some similarities and differences between American and British Blackness and Black womanhood as they are depicted in literature, specifically?

BE: I don’t claim to be an expert on this and I’d hate to generalize, but I can talk more widely about the differences between the U.K. Black experience and its American counterpart. The recorded history of Black Britain goes back to the Roman occupation of two thousand years ago (something I wrote about in my 2001 novel, The Emperor’s Babe and picks up in a big way from the 16th century, but we don’t have Black ancestry here with unbroken lineage beyond the 12th century.

I can count the number of Black British women novelists publishing today on two hands.

Most people of color in the U.K. arrived post-WWII so our lived history is very recent compared to America’s history of four hundred plus years of African Americans. We are also a small minority in terms of race in this country. There are about 2 million people of African descent here, as opposed to some 40 million in the U.S. This is reflected in our literature, with little of it and most of which was very male-dominated until the 90s, with Black women putting in rare appearances, most notably in the works of Nigerian novelist, Buchi Emecheta, who migrated to the U.K. in the 60s.

It’s really only in the past 20 years that we’ve seen more Black female presence in U.K. literature, but certainly not enough of it. I can count the number of Black British women novelists publishing today on two hands. The same can’t be said for the U.S. In the 90s young Black British women writers were writing similarly young protagonists in coming-of-age novels. Most of those writers disappeared. Since then we’ve had a few writers writing Black female protagonists who are still mainly young, also urban and contemporary. African American women’s fiction and literature—which so inspired my younger self—far outperforms our own production here in the U.K. in terms of the quantity of this work. One of my aims with Girl, Woman, Other was to break through these limitations. I think any wider comparison with the U.S. will require something of an academic thesis.

TLC: In your interview with the New York Times , you talk about writing about the African diaspora. Girl, Woman, Other , are stories about womxn whose parents or grandparents immigrated or worked in England in the 19th and 20th centuries. Dominique was the only character where it was mentioned that her ancestry could be traced back to slavery and Hattie’s lineage included slave traders, but otherwise, that part of the diaspora is not explored very much.

Coming from an American perspective where so much of our literature involves slavery, even when it is about other aspects of the diaspora, I am curious about your decision not to touch heavily upon the impact of slavery for Black British people—slavery in England and the slave trade outside of it involving the English.

BE: I’m not sure why my novel should draw more on the slave trade when it’s not a novel looking that deeply into British history. And if there’s one aspect of Black British history that continues to be mined in all media, it’s the transatlantic slave trade, to the extent that it alone is synonymous with our history, even though, as I said earlier, our history goes much deeper. My novel is about British women living in the 20th and 21st centuries, and it delves to some extent into their ancestry but it’s touch on slavery is light, as it should be. Britain was a major player in the transatlantic slave trade but there weren’t that many slaves living in the U.K., rather they were in the West Indies. Some of the women in my novel have Caribbean origins and some have direct African origins. Many, many writers continue to explore the slave trade and indeed my own 2008 novel, Blonde Roots , is all about slavery—a satirical inversion of this slave trade where Africans enslave Europeans. It’s very much an indictment of Britain’s involvement in the slave trade. My focus with Girl, Woman, Other was to explore so many more areas of our lives that go under the radar.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven't read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.

ARTICLE CONTINUES AFTER ADVERTISEMENT

Carmen Maria Machado’s Slightly Uncanny Retro Cheese Ball Is Exactly What You Need

Holiday party for one? Make this recipe from the Tables of Contents cookbook and eat the whole thing

Dec 22 - Carmen Maria Machado Read

More like this.

7 Poetry Collections About the Complexities of Black Womanhood

Amber McBride, author of "Thick with Trouble," recommends poems that explore the nuances of gender and race

Feb 16 - Amber McBride

7 Haunting Ghost Stories by Black Women Writers

In literature, we have used ghost stories to tell the things we are too scared to hear about

Apr 7 - Soraya Palmer

How Do You Exist In a World that Sees You As Monster or Ghost?

Christian J. Collier's poetry collection "The Gleaming of the Blade" uses horror to explore what it means to survive the South as a Black man

Mar 11 - Sam Risak

DON’T MISS OUT

Sign up for our newsletter to get submission announcements and stay on top of our best work.

- The Hypercritic Project

- Hypercritic for Companies

- Media coverage of Hypercritic’s work

- Meet the Hypercritics

- Collections

- Write To Us

Don’t miss a thing

Supported by

Copyright 2022 © All rights Reserved. Iscrizione registro stampa n. cronol. 4548/2020 del 11/03/2020 RG n. 6985/2020 al Tribunale di Torino. Use of Hypercritic constitutes acceptance of our Terms of Use , Privacy Policy , Cookie Policy

- Girl, Woman, Other | Intersectional feminism in modern Britain

Big - Little

Fast - Slow

Easy - Hard

Clean - Dirty

Original language

“Life is much easier for men, simply because women are much more complex,” states Bernardine Evaristo in her eclectic book Girl, Woman, Other . Indeed, complexity is the central theme of this novel that navigates through the lives of twelve individual black women. They are the representatives of what has come to be known as intersectional feminism in modern Britain. It’s a story that made Evaristo, born in London but of Nigerian descent, the first Afro-British woman to win the prestigious Booker Prize in 2019.

Modern language

Firstly, one thing that comes across about this novel is the unconventional use of punctuation . Full stops and commas are mostly absent. Moreover, paragraphs do not seem to follow any syntactical logic. It feels as if readers are experiencing a piece of poetry rather than prose. Thus, reading becomes a very smooth act: it is like floating amongst short stories .

A similar use of punctuation is not merely a stylistic choice. Evaristo’s protest against our contemporary patriarchal racialized society is made evident by eliminating conventional punctuation . The decision to do so is a manifesto of intersectional feminism in modern Britain. In fact, complex punctuation can be said to mirror the complexity of the women in the book. Taken to the extreme, the absence of punctuation offers women the freedom of self-expression. Such appears to be the thinking.

Modern women

Each of the twelve characters has a chapter. All women are unique in their own way. Readers meet unapologetic lesbian Amma (see Mr. Loverman for another queer story by Evaristo), and then they encounter Amma’s best friend, the uptight teacher Shirley. Then, there is divorcee Penelope and non-binary Morgan, and finally, successful finance trader Carole and LaTisha, a teen mom of three. Their life experiences, even though they share the common feature of being women, seem quite different and seemingly incompatible.

Yet what pools them together is not just their being women, but black women in post-colonial Britain. They are all facing tough socio-political struggles as a result of their race. This makes them a manifesto not simply of feminism but of intersectional feminism . “What does it mean to be a woman of color in today’s society? What is privilege? How can I get privilege?” are just some of the problematic questions Evaristo’s characters ask themselves.

Modern writers

The themes proposed by Evaristo team her up with some rising black women writers in the English-speaking world. One is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie , author of We should all be feminists and Americanah . In the latter, a young Nigerian woman learns to adapt to racialized American culture. On the other hand, Evaristo’s writing resembles Zadie Smith’s novels, the author of Swing Time . That is the story of two young women of color’s friendship in modern London.

A feeling of support and respect is also the red thread that unites Evaristo’s characters in Girl, Woman, Other . This is most remarkable in the final chapter, where all characters gather at Amma’s theatre premiere. They are girls, women, and others: weird, queer, and stunning.

Lovingly Related Records

The Handmaid's Tale | It’s all much more than fiction

Posted on 10 September, 2020

Camere Separate | The search for a balanced existence

Posted on 08 September, 2020

Americanah | From Nigeria to America and back

Posted on 05 July, 2022

Advertisement

Supported by

Books of The Times

‘Girl, Woman, Other,’ a Big, Busy Novel About New Ways of Living

By Dwight Garner

- Nov. 4, 2019

- Share full article

Bernardine Evaristo ’s eighth work of fiction, “Girl, Woman, Other,” shared the Booker Prize this year with Margaret Atwood’s “The Testaments,” a sequel to “The Handmaid’s Tale.” These novels are linked for posterity now, like conjoined siblings.

Was this split decision a dereliction of duty on the jury’s part or is more the merrier? Two Nobel Prizes in Literature were distributed this year as well, for a different reason. (The gold medal, diploma and check were withheld last year because of sexual harassment and corruption in the Academy.)

Perhaps this is a health-giving direction. Iris Murdoch, in 1967, wanted the Beatles to be jointly named Poet Laureate in England. After scanning the cable news most nights, I’d hardly be averse to voting for the cast of “Oklahoma!” for president in 2020.

“Girl, Woman, Other” is a big, busy novel with a large root system. The characters start to arrive (Amma, Yazz, Dominique, Carole, Bummi and LaTisha) and they keep arriving (Shirley, Winsome, Penelope, Megan/Morgan, Hattie and Grace). Everyone should be provided with a latte and a nametag.

We meet these characters’ friends and sometimes their families, too. Lorrie Moore has written that Ann Beattie’s fiction is a valentine to friendships. The same is true of Evaristo’s. This novel is a densely populated village where everyone leans on one another in order to scrape by.

[Bernardine Evaristo, the first black woman to win the Booker Prize, talks about her mission to write about the African diaspora .]

The primary character is probably Amma, a black lesbian playwright, now in her 50s, whose new play is being produced at the National Theater in London. Success has taken her out of range of some of her old anxieties about life, and put her in range of awkward new ones.

After a life spent on the margins, criticizing the center of the culture, is Amma selling out? If privilege is the original sin of wokeness, what happens when you accumulate privilege yourself?

This slice of the story is semi-autobiographical. Amma founds a theater company with a friend. Evaristo was co-founder, with two other women, of the Theater of Black Women in the early 1980s.

Amma’s story is followed by 11 others that drift back and forth in time. One character, Carole, attends Oxford (she complains about the “revolting Stone Age food”) and becomes an investment banker. Another, Hattie, is 93 and lives on a farm in Northern England. Still others are young and live in contemporary London.

This polyphonic novel, packed with interconnected stories, is similar in some ways to the monologues in Ntozake Shange’s “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf.” It may also remind some readers of Alison Bechdel’s warm and sophisticated comic strip “Dykes to Watch Out For.”

Like that comic, “Girl, Woman, Other” presents a landscape of abiding multicultural sensitivity. Evaristo’s dedication sets the tone: “For the sisters & the sistas & the sistahs & the sistren & the women & the womxn & the wimmin & the womyn & our brethren & our bredrin & our brothers & our bruvs & our men & our mandem & the LGBTQI+ members of the human family.”

This dedication will prompt many readers of my acquaintance to rush inside, and just as many others to flee in the opposite direction. A few, like squirrels on two-lane blacktop, will lose all composure and become roadkill.

A reason to stick around: Like Bechdel, Evaristo has a gift for appraising the lives of her characters with sympathy and grace while gently skewering some of their pretensions. When you are feeling your way into new ways of living, she understands, there must be room for error.

Carole keeps Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons” as her ringtone because she wants to appear classy, and repeats a morning mantra: “I am highly presentable, likable, clubbable, relatable, promotable and successful.”

Dominique dates an American woman named Nzinga, a “radical feminist separatist lesbian housebuilder” with epic dreadlocks and a “swamp-diva-voodoo-queen” vibe, only to discover that her real name is Cindy. Cindy is tough; she aims her cultural commentary as if into a spittoon. She’s even tougher on Dominique. Escape will be necessary.

“Girl, Woman, Other” is written in a hybrid form that falls somewhere between prose and poetry. Evaristo’s lines are long, like Walt Whitman’s or Allen Ginsberg’s, and there are no periods at the ends of them.

There’s a looseness to her tone that gives this novel its buoyancy. Evaristo’s wit helps, too. Yazz describes herself as “part ’90s Goth, part post-hip hop, part slutty ho, part alien.” We learn how useful a hijab can be when you want to have a hands-free cellphone conversation.

This looseness can detract as well. There is sometimes the sense that Evaristo loves all of her sentences a little bit but few of them quite enough. This essentially plotless novel grows longer, but it does not always appear to grow richer.

There comes a point in this narrative where you’d rather settle into the characters you’ve met than be introduced to still more new ones. You begin to feel you are always between terminals at a very large airport, your clothes and toiletries in a little wheelie suitcase behind you. It’s possible to admire this deeply humane novel while permitting your enthusiasm to remain under control.

A lot of human experience is packed into “Girl, Woman, Other.” Penelope, who hasn’t had sex in ages, thinks to herself: “It had been a long time since she’d been seen in a state of undress by anyone other than the matronly bra-fitter at Marks & Spencer.”

Dominique worries that her penchant for sleeping with blonde women means that she’s been brainwashed by a beauty ideal. Amma turns around in her mind the implied whiteness of a British accent.

Amma’s play opens at the National. Dominique greets her backstage and says, “afro-gynocentricism caused a femquake tonight.” The ground rattles further for another character when she gets the results of a mail-order DNA test.

Identity — artistic, cultural, familial — is slippery in “Girl, Woman, Other.” Yazz gets a surprise when she opens a drawer under her father’s bed. It’s a surprise she deserves. She thinks: “You never know people until you’ve been through their drawers / and computer history.”

Follow Dwight Garner on Twitter: @DwightGarner .

Girl, Woman, Other By Bernardine Evaristo 452 pages. Black Cat. $17, paper.

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

Aleksei Navalny’s Prison Diaries: In the Russian opposition leader’s posthumous memoir, compiled with help from his widow, Yulia Navalnaya, Navalny faced the fact that Vladimir Putin might succeed in silencing him .

Jeff VanderMeer’s Strangest Novel Yet: In an interview with The Times , the author — known for his blockbuster Southern Reach series — talked about his eerie new installment, “Absolution.”

Discovering a New Bram Stoker Story: The work by the author of “Dracula,” previously unknown to scholars, was found by a fan who was trawling through the archives at the National Library of Ireland.

The Book Review Podcast: Each week, top authors and critics talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book Reviews

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Class, Culture And Sexual Identity Take Center Stage In 'Girl, Woman, Other'

Maureen Corrigan

Bernardine Evaristo's nuanced and entertaining Booker Prize-winning novel is told from the point of view of 12 British women of color — all just a few degrees of separation apart from each other.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Girl, Woman, Other

40 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Chapter 5-Epilogue

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

When Carole begins to make friends with her upper-class peers at college, Bummi laments that Carole will “soon belong completely to them” (159). What does Bummi mean? What are her concerns?

Compare and contrast the mother-daughter relationships between Yazz and Amma, and Bummi and Carole . What do Amma and Bummi’s respective mothering styles say about their life experiences and personalities? How do these qualities affect Yazz and Carole?

What binds Yazz and her college mates together? How are they different and how are they similar? What common experiences have they had?

Plus, gain access to 8,450+ more expert-written Study Guides.

Including features:

Related Titles

By Bernardine Evaristo

Mr Loverman

Featured Collections

Audio Study Guides

View Collection

LGBTQ Literature

Popular Book Club Picks

Women's Studies

The website is currently undergoing maintenance. We appreciate your understanding!

Girl, Woman, Other

There is something very of this moment about Bernardine Evaristo’s Booker-prize-winning Girl, Woman, Other. It makes so many other books seem old-fashioned and out of touch. One wonders how Literature with a capital L so long got away with the narrowness of its representation. The book makes it seem strange that the richness and variety of experience embodied in and by the stories it chooses to tell hasn’t always been recognised as obviously valuable.

The stories told are of twelve people – as the dust jacket puts it – ‘mostly women, mostly black’ for whom Britain has, in one way or another, been a home. They vary hugely and span intergenerational connections and political divides to include the cantankerous 93-year-old Hattie who has spent her entire life on her farmstead near the Scottish border and voted for Brexit, to her great-grandchild Morgan née Megan, a Twitter influencer, whose gender identity Hattie can’t grasp, beyond it’s being somehow “non-binding”.

The book is exceptional in its capacity to extend almost equal empathy to the complex lives of all these characters. Certainly, some are more gripping than others, and what speaks to each reader will probably be related to how much of their own world and values they see represented there. With the enormous variety in characters, it’s clear that there will be political disagreements amongst them. Evaristo is able to confront these conversations not only with sensitivity, but also with a sense of humour – be it when a transsexual woman mansplains the difficulties of living in the patriarchy to someone who’s lived their whole life up to that point as a woman; or when a white working class country bumpkin quotes Roxanne Gay to argue against discrimination hierarchies at the ultra-hip London-raised Yazz, who considers herself the wokest millennial alive.

At the centre of the larger narrative that serves to connect the different life stories to each other is a play put on by Amma, (once-)radical-feminist lesbian thespian. The after-party brings together many of the cast-members readers have got to know throughout the course of the book, so that when we encounter them here, they are nuanced, textured characters. Amma’s story especially questions the compatibility of becoming successful in the ‘establishment’ and staying true to one’s ‘radical’ principles. These conversation are held up for scrutiny, yet while the book pokes fun at the individuals who people this artsy London theatre scene, its critical gaze isn’t quite as critical as it might be of the essential elitism of what is very much a scene .

Formally, Evaristo remains an innovator. She foregoes capitalisation and full stops in Girl, Woman, Other , for a free-flowing effect of run-on sentences. The verse-like quality of her writing gives it a gentle rhythm of its own, while the free indirect style that enters the different chapters lets each of the characters have a measure of their own say in the telling of their stories.

Evaristo’s storytelling is perhaps at its most compelling when she is unstitching the histories of colonialism and migration that brought these woman and their ancestors to Britain. It also addresses the shifting sands and the changing priorities of a migrant like Bummi, from Nigeria, who spent many years working as a cleaner, and her daughter Carole, born and raised in England, now a successful banker in the city. Enormously diverse as the experiences represented evidently are – and the characters are by no means flawless and are shown also to wrong each other – the pull of the book is towards togetherness, and its implicit argument is that more connects than divides us. Not only is it entirely worth reading, it might leave you feeling a touch optimistic.

Order the book here and support us! The work behind poco.lit. is done by us – Anna und Lucy. If you’d like to order this book and want to support us at the same time, you can do so from here and we will get a small commission – but the price you pay will be unaffected.

Support poco.lit. by becoming a Steady member .

You can support our work with a monthly or yearly subscription.

- Girl, Woman, Other

A ‘fusion fiction’ novel. Hamish Hamilton/ Penguin UK (May 2019) (Paperback March 2020) Black Cat/ Grove Atlantic USA (Nov. 2019)

Winner of the Booker Prize 2019 One of Barack Obama’s 19 Favourite Books of 2019 Roxane Gay’s Favourite Book of 2019 The 12th bestselling hardback fiction book in the UK 2019; one of two books on the list not categorised as mass market. The No 1 bestselling paperback book in the UK for 5 weeks (Summer 2020) & 44 weeks in the Top 10 overall

BUY FROM WATERSTONES BUY FROM HIVE.CO.UK – for 320 independent UK bookshops BUY FROM PENGUIN BUY FROM AMAZON.CO.UK And please do otherwise buy from your local independent bookshop – to support them.

Girl, Woman, Other follows the lives of twelve very different people in Britain, predominantly female and black. Aged 19 to 93, they span a variety of cultural backgrounds, sexualities, classes and occupations as they tell the stories of themselves, their families, friends and lovers, across the country and through the years. A Sunday Times Bestseller A Sunday Times Book of the Decade A Guardian book that defined the decade

A BOOK OF THE YEAR inc: V ogue (US) Times Literary Supplement Guardian New Statesman Evening Standard Kirkus Reviews The Irish News iNews paper NPR (National Public Radio USA) New Yorker 10 Best Books 2019 Washington Post 10 Best Books 2019 Financial Times Top 10 Fiction Books 2019 Entertainment Weekly Top 10 Books 2019 Washington Independent Review of Books 51 Favourite Books of 2019 Daily Telegraph 50 Best Books 2019 & Critics’ Pick TIME 100 Must-Read Books 2019 Elle 13 Best Feminist Books Yahoo! Lifestyle 25 Best Books 2019 Oprah Mag Best LGBT Books 2019 Red magazine 10 Best Books CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) 28 Best International Fiction 2019 Amazon Editors’ Pick of the Year and Apple Books Best of the Year Times (UK) Best Audio Book of 2019, read by Anna-Maria Nabirye Guardian : Best of Summer Books. June 2019 Sunday Times : Ultimate Summer Books. June 2019 Observer : Bookseller’s Choice. July 2019

‘It’s a triumphantly wide-ranging novel, told in a hybrid of prose and poetry…It’s also, to my mind, the strongest contender on the (Booker) shortlist. A big, bold, sexy book that cracks open a world that needs to be known…Evaristo’s job is to observe, broaden our minds and to be funny – often very funny indeed…’ Sunday Times

‘My money (though) is on Evaristo. Her book was the last of the shortlist I read, but it not only exceeded my expectations, it felt like a novel that did what all great novels do, dropping the reader into richly imagined lives, recognising that in the intimate presentation of the particular lies the universal, and making a convincing case that the best novels push the genre in exciting new directions.’ Observer Booker roundup

‘This is the pick of the Booker shortlist for me. It’s the only novel that had me enthralled and engaged throughout. Irish Times Booker roundup

‘Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo isn’t just my book of the year, it’s one of the most insightful and life-affirming books I’ve read in many a year. It comprises twelve beautifully interwoven stories of identity, race, womanhood, gender and sexuality, all rooted in the realities and complexities of modern Britain. The characters are vivid and authentic, the writing exquisite and it brims with humanity.’ Nicola Sturgeon, First Minister of Scotland ‘Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other …is a breathtaking symphony of black women’s voices, a clear-eyed survey of contemporary challenges that’s nevertheless wonderfully life-affirming… Together, all these women present a cross-section of Britain that feels godlike in its scope and insight…just as crucial to this novel’s triumph is Evaristo’s proprietary style, a long-breath, free-verse structure that sends her phrases cascading down the page. She’s formulated a literary mode somewhere between prose and poetry that enhances the rhythms of speech and narrative. It’s that rare experimental technique that sounds like a sophisticated affectation but in her hands feels instantly accommodating, entirely natural. It’s just the style needed to carry along all these women’s stories and then bring them to a perfectly calibrated moment of harmony — a grace note that rings ou t after the orchestral grandness of Girl, Woman, Other draws to a perfect close.’ The Washington Post

‘This wonderful novel is both a critique of the deadening limitations of language when deployed as a crude political instrument, and a celebration of its limitless possibilities. Rather like John Coltrane’s riff on My Favourite Things, Girl, Woman, Other soars away on multiple emotional trajectories before, in the final chapter, set during the after-party of Amma’s triumphant first night, coming back to land, with the characters finally all in the same room. Yet it remains tantalisingly open-ended, with the not-entirely resolved exchange between Amma and her old friend Dominique. You suspect Evaristo is wise enough to know that, after the celebration, amid all the joyous feelings of sisterly togetherness, the conversation must still go on.’ The Telegraph

‘So joyfully uncontained it can hardly pause for punctuation, this surprise Booker winners unfurls a fantastically panoramic survey of modern womanhood: radical lesbian separatists, sexually fluid millennials, mad housewives, middle-aged cleaning ladies, bankers and bloggers and teachers. Most of them are black or brown, but Girl truly reads like a rainbow — literary fiction written in pure, glorious Technicolor.’ Entertainment Weekly US

‘The intermingling stories of generations of black British women told in a gloriously rich and readable free verse, will surely be seen as a landmark in British fiction.’ Guardian

‘David Olusoga observes in his book Black and British , in much of history “black figures are mute”, particularly the voices of women, “silenced by a lack of written sources”. The wide-ranging fictional works of Bernardine Evaristo, however, have helped to fill this void. The Emperor’s Babe followed a Nubian teenage bride in AD 211; Blonde Roots inverted the transatlantic slave trade – now in Girl, Woman, Other , Evaristo adopts an even bigger canvas, with a sparkling new novel of interconnected stories….In Evaristo’s eighth book she continues to expand and enhance our literary canon. If you want to understand modern day Britain, this is the writer to read.’ New Statesman

‘The deserved joint winner of the Booker Prize . Evaristo’s beautfilly observed novel spans decades in its examination of black womanhood. iNews

‘Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other is one of the outstanding publications of 2019. This dazzling piece of experimental writing centres on 12 black British women…the novel’s non hierarchical form gives equal weight to a wide range of experiences…It is her distinct lyricism that makes Girl, Woman, Other unputdownable and such a joy to read. Times Higher Education

‘Bernardine Evaristo’s eighth work of fiction, which has been shortlisted for the Booker Prize, is one of those books that makes the reader ask “Where have you been all my life?” and rush out for the author’s backlist. Perhaps coming to a writer afresh when their talent is fully formed makes the effect all the more dramatic – if so, then the new readership Evaristo will justifiably gain from her shortlisting will be thrilled.’ Irish Times

I picked up Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl,Woman, Other one evening earlier this week thinking I’d get fifty pages in and save the rest for the weekend. Hours later, I realized it was 1 A.M. and that I needed to force myself to go to bed for work the next morning. Evaristo’s Booker Prize–winning novel is a compulsively readable exploration of twelve characters’s lives in contemporary Britain, the majority of them black and female. Much of the book converges around The Last Amazon of Dahomey , a play by Amma—whose chapter opens the novel—that is set to premiere at the National Theatre. Each chapter takes the voice of a different character, many of them connected to one another through blood or friendship, and as Evaristo moves closer to the premiere of the play, she explores questions of race, gender, sexuality, immigration, and what it means to be British. There’s something truly pleasurable to watching a virtuoso at work, and Evaristo’s ability to switch between voices, between places, and between moods brings to mind an extraordinary conductor and her orchestra. Paris Review

‘The lives of 12 very different, loosely connected black women are depicted in this marvellous novel that deliberately sets out to resist the notion that any one of their stories should be seen as representative of anything other than itself. Carole is a banker, Amma is gay and a playwright, LaTisha has two kids by the age of 19, but they and everyone else we meet sing off the page as they negotiate their own way of being through the prisms of race and gender. In prose that defies many of the rules of punctuation, and feels all the more immediate for it, Evaristo — who was born in Eltham to a white English mother and Nigerian father, and has now written eight books on the African diaspora — summons up a limitless canvas of black female experience that’s by turns funny, acutely observed and heart-snagging. Terrific. ‘ Metro

‘This fast-paced, rhythmically composed, heart-rending Booker Prize winner centralizes and gives voice to 12 unforgettable black British women characters who are often marginalized and silenced in Britain due to their race, gender, sexual orientation, and class.’ The Atlantic USA

‘This is a complex, yet easy-to-read, fierce novel about the lives of Black British women. Some love men, some love women, some love both. From a lesbian playwright to a nonbinary social media influencer, and many in between, Evaristo showcases the cross-section of their pains and triumphs. This award-winning writer juggles the many characters and fast-moving story pace with aplomb, keeping the reader laughing, shocked, and wholly engaged while rooting for all of these magnificent and unforgettable characters.’ San Francisco Bay Times

‘Prize-winning novels carry uncomfortable baggage. On the one hand, they have been anointed Important Works of Literature. On the other, that Importance (always capitalized) implies a formal inaccessibility, a lack of interest to the passing reader. Sometimes, the winners of major prizes pose genuine mysteries (not least, why they were chosen). Other times, as with Bernardine Evaristo’s receipt of the 2019 Booker Prize, such novels are genuinely accessible, charming, and urgent.’ New York Journal of Books

‘In this snapshot of Britain from 1905 to the present day that unites Newcastle with Cornwall, Evaristo tells the tales of 12 interconnected characters who are mostly women and mostly black. Ambitious, flowing and all-encompassing, she jumps from life to life weaving together personal tales and voices in an offbeat narrative that’ll leave your mind in an invigorated whirl. This is an exceptional book that unites poetry, social history, women’s voices and beyond. You have to order it right now in fact.’ Stylist mag azine

‘Spanning a century and following the intertwined lives of 12 people, this is a paean to what it means to be black, British and female. Evaristo’s prose hums with life as characters seem to step off the page fully formed. At turns funny and sad, tender and true, this book deserves to win awards.’ Red magazine

‘Three books recently published by great female writers should be on everyone’s holiday list. In Girl, Woman, Other, Bernardine Evaristo weaves together the stories of a range of women across continents. It’s a magnificent read from a writer with a gift for humanity.’ Observer – Summer Reads

‘This masterful novel is a choral love song to black womanhood.’ Elle magazine

‘ Beautiful, hilarious and moving homage to what it means to be black and British. Girl, Woman, Other celebrates the rich variety of black women across generations.’ Refinery 29

‘A magnificent chorus of black British voices..As she creates a space for immigrants and the children of immigrants to tell their stories, Evaristo explores a range of topics both contemporary and timeless. There is room for everyone to find a home in this extraordinary novel. Beautiful and necessary.’ Kirkus Reviews US

‘..the women , with all their flaws, mistakes and desires on show, bite back, with wit, force, fierceness and wisdom.’ The Times

‘Evaristo is known for narratives that weave through time and place with crackling originality. Girl, Woman, Other is no exception.’ Vogue

‘Evaristo’s eighth novel brims with vitality…Evaristo writes sensitively about how we raise children, how we pursue careers, how we grieve, how we love…The form she chooses here is breezily dismissive of convention. The flow of this prose-poetry hybrid feels absolutely right, with the pace and layout of words matched to the lilt and intonation of the characters’ voices…She captures the shared experience that make us, as she puts it in her dedication, “members of the human family.”‘ Financial Times

‘Superlatives pale in the shadow of the monumental achievement of Girl, Woman, Other . Few adjectives suffice…Evaristo’s verbal gymnastics do things language shouldn’t be able to do. It’s a Cirque du Soleil of fiction…Bernardine Evaristo is the writer of the year. Girl, Woman, Other is the book of the decade.’ Washington Independent Review of Books

‘This novel is a sure-footed triumph.’ India Times

‘Evaristo’s vital, joyous novel…daisy chains with warmth, wit and genuine depth of feeling across the span of recent black British history…Her writing is characterised by a dancing lightness throughout. It is often very funny…This lightness, this flux, is embedded in the pith of Evaristo’s prose. Her novel unspools down the page, stanza-like. Unconstrained by capitalisation or full stops, the story spills as – line by line – it slips from one voice to another…There is jeopardy and surprise in the way Evaristo propels the reader into empty space, before turning abruptly on the next beat – wrong-footing us in to laughter or a catch in the throat. The Spectator

‘In its disregard for conventional arrangements of paragraphs and cut-and-dried syntax, the novel offers an irresistible invitation to dive right in: to be with its people, to question your own choices, motivations and assumptions, to recognise the role you play in shaping the lives of others and of our body politic. The use of different Englishes and registers of English forms an inalienable part of the work”s innate musicality.’ The Spider’s House

Bernardine Evaristo’s vibrant and poetic novel Girl, Woman, Other follows the lives and struggles of twelve different characters. Mostly women, black and British, they tell the stories of their families, friends and lovers, across the country and through the years. This book is everything. Closer magazine

Magnificent novel of such grand scope and ambition. This is a novel about 12 women but it is also a sweeping history of the black British experience. The attention to detail, the structure, the syntax, it’s all brilliant and moving and truly represents what fiction at its finest. Roxane Gay, 5-star review on Goodreads and her Best Book of the Year

Girl, Woman, Other is majestic. I absolutely adored it. It’s soaked into my skin. It’s one of the favourite novels of my whole life. This is what I read for, to find books like this one. Russell T Davies, screenwriter, Doctor Who , Years and Years , A Very English Scandal, Queer as Folk

This is one of those truly important novels which show you your own culture and history in a revelatory new light and at the same time expand your sense of what the novel as a form is capable of – the two achievements being of course inseparable. Bernardine Evaristo combines, effortlessly, it seems, the compelling inventiveness of a great story-teller with the precision and economy of a poet – she has created a whole new form, which sweeps you irresistibly forward. The twelve women’s lives she recounts are woven without forcing into a magnificent structure, the whole thing shot through with wit, compassion and almost unnerving insight. It’s very funny, and very sexy. It seems to me a book to return to and to learn from – about the country we live in, and about the inexhaustible potential of the novel to give fresh accounts of it. Alan Hollinghurst, Booker Prizewinner

I’m an avid reader, so Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Wom an, Other caught my eye in the bookshop. It’s phenomenal. Even though the stories cover different eras and places, her ability to form such solid characters really spoke to me as a woman of colour. And because the stories were set in England, it felt really close to home. She tackles so many of the challenges that women face today but in a beautiful non-cliche way. She’s a professor at Brunel — that’s where I went to university – and I felt a moment of pride. Adwoa Aboah, model & activist, Guardian

Hilarious, heart-breaking & honest. Generations of women and the people they have loved and unloved – the complexities of race, sex, gender, politics, friendship, love, fear and regret. The complications of success, the difficulties of intimacy. I truly haven’t enjoyed reading a book in so long. Warsan Shire, author of Teaching My Grandmother How to Give Birth & poet-collaborator with Beyonce on Lemonade.

Bernardine Evaristo’s books are always exciting, always subversive, a reminder of the boundless possibilities of literature and the great worth in reaching for them. Her body of work is incredible. Diana Evans, author of Ordinary People

There is an astonishing uniqueness to Bernardine Evaristo’s writing, but especially showcased in Girl, Woman, Other. How she can speak through twelve different people and give them each such distinct and vibrant voices is astonishing. I loved it. So much. Candice Carty-Williams, author of Queenie

Once again, Bernardine Evaristo reminds us she is one of Britain’s best writers, an iconic and unique voice, filled with warmth, subtly and humanity. Girl, Woman, Other is an exceptional work, presenting an alternative history of Britain and a dissection of modern Britain that is witty, exhilarating and wise. Nikesh Shukla, author and editor of The Good Immigrant

Girl Woman Other is brilliant. I feel like a ghost walking in and out and in again on different people’s lives, different others. Some I feel close to, some I feel I must have met and some are so ‘other’ that I have to stretch myself to see them. Mind expanding. Philippa Perry, author of How to be a Parent

Bernardine Evaristo is one of those writers who should be read by everyone, everywhere. Her tales marry down-to-earth characters with engrossing storylines about the UK today. Elif Shafak, author of Three Daughters of Eve

Bernardine Evaristo is the most daring, ambitious, imaginative and innovative of writers, and Girl, Woman, Other is a fantastic novel that takes fiction and black women’s stories into new directions. Inua Ellams, author of The Half God of Rainfall

For a fresh and inspiring take on writing about the African diaspora, there’s nothing like a new book by Bernardine Evaristo. Somehow she does it every time! Margaret Busby, editor of Daughters of Africa

website © Bernardine Evaristo 2022 Cookie policy Admin login design: AERTA UK

- Look Again: Feminism

- Mr Loverman

- Blonde Roots

- Soul Tourists

- The Emperor’s Babe

- Island of Abraham

- Foreign editions ++

- International Tours

- Literary prize juries

- Essays & Criticism

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

Girl, Woman, Other

Bernardine evaristo.

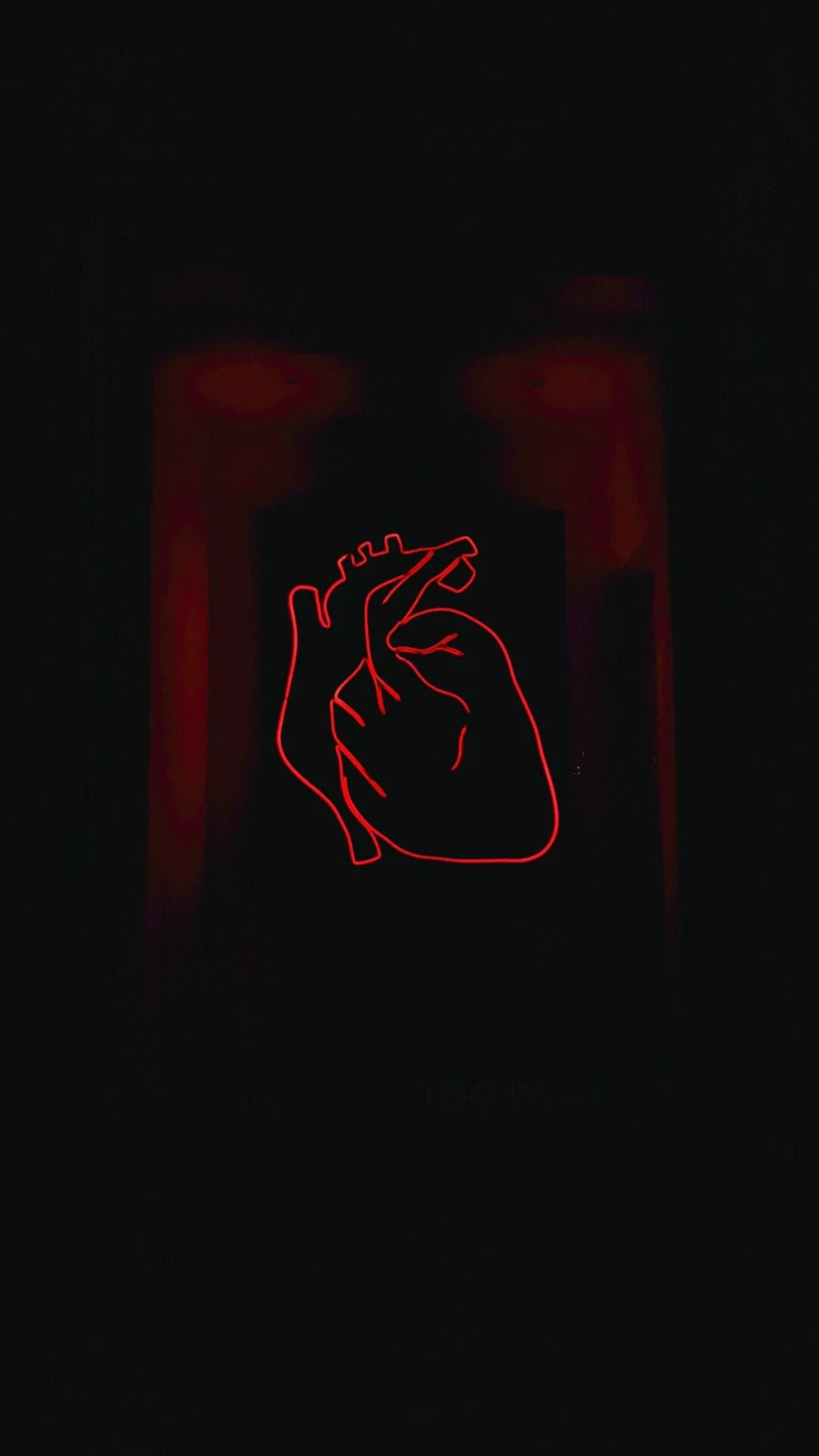

Love and sexuality run through the heart of the 12 narratives that make up Girl, Woman, Other , and each of the women’s stories explores the myriad ways that love intersects with racial and ethnic identity. The pressure to fall in love with someone from one’s own racial or ethnic group is present in many of the women’s lives. Carole’s mother, Bummi , is devastated when her daughter falls in love with a white, English man instead of a Nigerian. For Bummi, this decision threatens to further erode Carole’s Nigerian identity, which Carole has already suppressed in order to assimilate—the only clear path Carole saw to achieve success in a discriminatory English society. Amma is a radical, activist lesbian who is proud of her “multicultural hoedom,” but ends up with two white women life partners. Dominique always dated blondes in her 20s, which a girlfriend later suggests is a product of her internalized racism. Falling in love with someone white also means facing those lovers’ racist families. Carole’s husband, Freddy , is excited to see his parents’ reaction when he brings home a Black woman, as if she’s a token he’s entitled to use to make a political statement to his family. When Julie , descended from an Ethiopian great-grandfather and African American grandfather, marries a man from Malawi, her family is angry with her for “ruining” the family line which becomes “whiter with every generation.” This desire itself is one rooted in their internalized racism, born of the traumas of growing up amidst the racism of the English countryside. Almost all the women the book features have experienced colorism and have either been sexually objectified or ignored because of their race. In this way, the characters’ stories highlight the relationship between love, sexuality, and racial and cultural identities, as well as how living in a racist, Western society complicates interracial love and desire.

Love, Sexuality, and Race ThemeTracker

Love, Sexuality, and Race Quotes in Girl, Woman, Other

Yazz noticed that those ‘buns’ reciprocated Courtney’s attention, her creamy softness pouring ostentatiously over the top of her denim blouse

they stared at Courtney, not at Yazz, who wasn’t the one getting checked out as usual, and she usually got checked out a lot

not that she’s interested in the kind of male who belts their trousers underneath their bum

today it’s all about Courtney, who’s not even particularly hot and it’s like Yazz is invisible and her friend is an irresistible goddess

a white girl walking with a black girl is always seen as black-man-friendly

Yazz has been here before with other white mates

it makes her feel so

Nzinga had suggested that her relationship history of blonde girlfriends might be a sign of self-loathing; you have to ask yourself if you’ve been brainwashed by the white beauty ideal, sister, you have to work a lot harder on your black feminist politics, you know

Dominique wondered if she had a point, why did she go for stereotypical blondes? Amma had teased her about it without judging her, she herself was a product of various mixtures and often had partners of all colors

in contrast, Nzinga had grown up in the segregated South, although shouldn’t that make her pro-integration rather than against it?

Dominique wondered if she really was still being brainwashed by white society, and whether she really was failing at the identity she most cherished – the black feminist one

did me and Papa come to this country for a better life only to see our daughter giving up on her opportunities and end up distributing paper hand towels for tips in nightclub toilets or concert venues, as is the fate of too many of our countrywomen?

you must go back to this university in January and stop thinking everybody hates you without giving them a chance, did you even ask them? did you go up to them and say, excuse me, do you hate me?

you must find the people who will want to be your friends even if they are all white people

there is someone for everyone in this world

you must go back and fight the battles that are your British birthright, Carole, as a true Nigerian

Freddy arranged for Bummi to meet his parents in a London restaurant, which she was looking forward to

except he warned her that although they’d warmed to the idea of Carole, once they saw how classy, well-spoken and successful she was (most importantly for his mother, how slim and pretty, too)

they’re still old-fashioned snobs

Freddy’s father, Mark, looked uncomfortable, said little at the dinner, Carole sat there with a fake smile plastered on her face the whole time

Pamela, his mother, smiled at Bummi as if she was a famine victim, when she started explaining the meaning of hors d’oeuvres to her, Freddy told her to stop it, Mommy, just stop it

Ada Mae married Tommy, the first man who asked, grateful anyone would

she didn’t exactly have suitors lining up in Newcastle wanting to proudly introduce their black girlfriend to their parents in the nineteen-sixties

Tommy was on the ugly side, a face like a garden gnome, her and Slim joked, none too bright, either

Hattie suspected the lad didn’t have too many choices himself

a coalminer from young, he was apprenticed as a welder when the mines were shut down

he proved to be a good husband and really did love Ada Mae, in spite of her colour

as he told Hattie and Slim when he came to ask for her hand

lucky that Slim didn’t lay him out

there and then

Sonny’s experience was somewhat different, according to Ada Mae who reported back that women queued up round the block for him

they thought he was the next best thing to dating Johnny Mathis

he married Janet, a barmaid, whose parents objected

and told her to choose

they made love with the gas lamp dimmed

she was his expedition into Africa, he said, he was Dr Livingstone sailing downriver in Africa to discover her at the source of the Nile

Abyssinia, she corrected him

whatever you say, Gracie

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

- study guides

- lesson plans

- homework help

Girl, Woman, Other Summary & Study Guide

Girl, Woman, Other Summary & Study Guide Description

The following version of the book was used to create this study guide: Evaristo, Bernardine. Girl, Woman, Other. Black Cat, 2019. Amazon Kindle eBook.

It is the opening night of Amma's play, The Last Amazon of Dahomey, which is premiering at the National in London. This represents a big step in Amma's career as she enters the mainstream theater community after decades of making indie art on the fringe with her good friend Dominique. While Amma's identity as a black lesbian had previously limited her options in mainstream theater, the establishment now seems to be embracing her. That night, Amma's daughter Yazz, whom she co-parents with her gay friend Roland, is in the audience with her university friends. Yazz is studying to be a journalist and has formed a core group of friends with two other brown girls and one white girl from her dorm. The four students all have different experiences of privilege as it intersects with their various identities, including their economic, racial, religious, and educational backgrounds. The next section is about Amma's friend and Yazz's godmother Dominique. Many years ago, Dominique met and fell in love with a woman named Nzinga. Dominique moved to America with Nzinga where they lived in a separatist feminist community. The relationship quickly becomes emotionally and physically abusive, and it is several years before Dominique decides to leave Nzinga and build a new life for herself in California where she founds a Women's Arts Festival.

Carole is on her way to work in the City where she is Vice President at a bank. Despite her Oxford education, polished appearance and manners, and high-powered job, Carole still has to deal with microaggressions, racism, and sexism in the workplace. At 13, Carole was raped by a group of older boys and, after a year of depression, she decided she wanted a future different from the working-class community she grew up in. She turns to a teacher, Mrs. King, for help, and becomes an academic star, eventually going to Oxford where she picks up posh habits. Her mother, Bummi, is upset that Carole seems to have lost connection with her Nigerian roots after going to Oxford. She wants Carole to marry a Nigerian man and is very upset when her daughter announces her engagement to an Englishman. A widow who migrated to England from Nigeria, Bummi starts her own cleaning business and has a lesbian relationship after her husband's death. However, she cannot come to terms with a new sexual identity and eventually marries a man named Kofi. LaTisha is Carole's friend from school, who hosts the party where Carole is raped, though LaTisha does not know about this. LaTisha dropped out of high school and had three children by three different fathers before the age of twenty-one. Her third child was fathered by Trey, the man who led the group who raped Carole, who also forced himself on LaTisha. LaTisha now works as a supervisor at the supermarket and is determined to get further promoted. She is also taking online courses. LaTisha's father, who had left the family suddenly when she was a child, appears in their lives again without warning and LaTisha realizes that her youngest child, who seems to echo Trey's temperament, needs his grandfather in his life.

Shirley begins the chapter as a young teacher determined to make a difference, but she soon becomes disillusioned with teaching and comes to hate her job vehemently. In spite of this, she mentors young Carole and continues to select a handful of students of mentor each year. Years later, Shirley is resentful that Carole never thanked her or kept in touch. Shirley's mother Winsome hosts their extended family in Barbados, where she and her husband have retired. She tells Shirley's daughter Rachel about her life as a young immigrant mother in England who encountered a lot of racism, both personal and systemic. Winsome then privately reminiscences about the affair that she carried on with Shirley's husband Lennox for over a year before he ended things. To this day, Shirley has no idea about the relationship between her husband and her mother. Penelope was a colleague of Shirley's at the school before her retirement. Penelope is a white second-wave feminist but harbors prejudice and implicit bias against people of color. Penelope was adopted and knows nothing about her heritage. After two failed marriages, she lives alone and is very upset when her daughter announces that she is moving to Australia with her husband and children.

Megan has always been a tomboy who hated the dresses and dolls her mother gave her. After leaving home, Megan begins to learn about different forms of gender expression, particularly through online communities and with the help of a transwoman named Bibi whom she meets online. Megan eventually identifies as gender-free and changes her name to Morgan and her pronouns to "they/them." She also begins a romantic relationship with Bibi. Six years later, Morgan is a popular social media influencer and speaker on trans rights and gender diversity. She is very close with her great-grandmother GG, or Hattie, who she visits regularly on the family farm, Greenfields. Hattie is in her early nineties and has a large extended family of descends, most of whom are mixed-race and have different relationships to their heritage, preferring to identify as white. Never having known her mother's father, she does an Ancestry DNA test with Morgan's help to learn more. Hattie's biggest secret is that she had a child when she was fourteen and was forced to give the baby away. She has never told anyone and does not know what happened to the child. Hattie's mother Grace never knew her father, who was an Abyssinian sailor. Her mother died when she was a child and Grace was raised in a girl's home before going to work as a maid. Grace then met and married Joseph Rydendale and became the mistress of his family farm, Greenfields, which their daughter Hattie eventually inherits.

At the after-party for Amma's play, which is already a huge success, Yazz's father Roland reflects on his success as a public figure and academic. Unlike Amma, Roland embraced the establishment long ago, though he resents being defined by his race. Also at the party are Carole, whose husband got them tickets, and Shirley, who is an old friend of Amma's. The teacher and her former student have an awkward and somewhat embarrassing reunion before Carole thanks Shirley for her help in the past, thanks that Shirley claims not to want or need. Amma and Dominique spend much of the evening together discussing the play and current social issues, in particular, how feminism has changed since they were young. Dominique resents the commercialization of the movement but Amma thinks they should celebrate the fact that Feminism is spreading.

In the epilogue, Penelope is traveling north to meet her birth mother, whom she found after doing an Ancestry DNA test. She was shocked to discover that she is part African. It is revealed that her mother is Hattie, and Penelope is the baby she was forced to give up in secret. Penelope is forced to rethink her identity and some of her prejudice against people of color begins to fall away when she meets Hattie. The two women meet at Greenfields where they are both full of emotion and happy to be together.

Read more from the Study Guide

FOLLOW BOOKRAGS:

30 Shows to Watch If You Love 'Gilmore Girls'

You'll recognize quite a few faces from Stars Hollow.

Gilmore Girls is the ultimate comfort show : It’s set in a small town where it’s perpetually autumn and where quirky but kind neighbors abound; it contains just enough low-stakes, easily resolved drama to keep you entertained but not stressed out, and, of course, it centers around an idyllic mother-daughter relationship. Because of that cozy perfection, it can be tough to figure out where to go next when you’ve reached the end of the classic series and need to move on from Stars Hollow.

Thankfully, you don’t need to stray too far. There are plenty of shows like Gilmore Girls to watch next that capture the same pleasant vibes, pop culture-reference-heavy dialogue, and tangly relationships—of the family, friend, and romantic varieties. Here, find 30 TV series to watch if you're a Gilmore Girls fan and where to stream them until your inevitable next rewatch of the Alexis Bledel and Lauren Graham hit.

'Better Things' (2016–2022)

Compared to the gentle, idyllic vibe of Lorelai’s life in Stars Hollow, Better Things takes a much grittier view of single motherhood. Its five seasons follow Pamela Adlon’s Sam, a working actress in L.A. juggling raising her three daughters, dating around, and dealing with her own difficult mother—who lives right across the street.

'Buccaneers' (2023– )

In the same way that Gilmore Girls showcased ambitious women living their lives on their own terms, so does this Apple TV + series. Here, the pursuit of freedom is even more subversive for the five young women at its heart, since it takes place in stuffy 1870s London. Plus, in other echoes of GG , Buccaneers features a tangly love triangle and a very sweet relationship between Christina Hendricks’ Patti and her two daughters, Nan and Jinny, played by Kristine Froseth and Imogen Waterhouse.

'Bunheads' (2012–2013)

In the time between Gilmore Girls and The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel , Amy Sherman-Palladino created Bunheads. The show starred Sutton Foster as an ex-Vegas showgirl who settles down in a small town after getting married and a job teaching at her mother-in-law’s ballet school. Devastatingly, the show was canceled after just one season, but has gained a cult following in the years since—and for good reason: In addition to the delightfully quirky premise, it also featured plenty of GG alums, from Emily Gilmore herself (Kelly Bishop) as the mother-in-law, to Liza Weil, who you’ll know best as Paris Geller.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

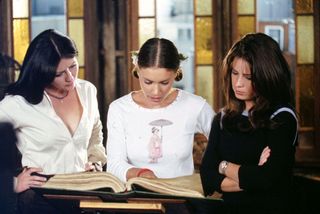

'Charmed' (1998–2006)

Just like Stars Hollow, it always feel like fall in the moody San Francisco of this turn-of-the-millennium classic. Charmed starts with a trio of sisters (played by Alyssa Milano, Shannen Doherty, and Holly Marie Combs) discovering that they’re the most powerful witches of all time and proceeding to face down a seemingly never-ending line of supernatural foes. Come for the complex sisterly relationships, stay for the glorious parade of Y2K looks.

'Crazy Ex-Girlfriend' (2015–2019)

Crazy Ex-Girlfriend is like if the neuroses, pop culture references, and whip-smart dialogue of Gilmore Girls were all cranked up several zany notches. It’s fun, funny, and full of original pop songs you won’t be able to get out of your head for weeks at a time.

'Derry Girls' (2018–2022)

Derry Girls may seem like a world away from Gilmore Girls —set in Northern Ireland in the ‘90s, during the Troubles—but its fast-talking, hilarious characters and powerful female relationships would surely fit in in Stars Hollow. The shows even share 50% of their titles!

'Ginny & Georgia' (2021– )

Ginny & Georgia isn’t an exact Gilmore Girls dupe, however, its basic premise is uncannily similar: The series begins when newly widowed Georgia (Brianne Howey)—who had her daughter Ginny (Antonia Gentry) when she was 15 and who’s no stranger to a perfectly timed pop culture reference—moves her family to a small New England town. In the series’ first episode, she even notes: “We’re like the Gilmore Girls but with bigger boobs!” Need we say more?

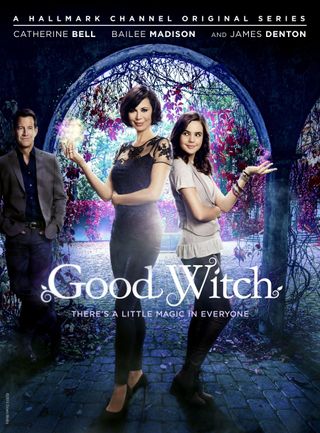

'The Good Witch' (2015–2021)

Based on a series of Hallmark movies, and set in the fictional small town of Middleton, this seven-season series stars Catherine Bell as the titular kind-hearted sorceress, Cassie Nightingale, and Bailee Madison as her daughter Grace, who has some magical powers of her own. Between her similarities to Cassie—a single mother to a teenage daughter and the manager of a local B&B—and her noted love of Bewitched , it’s safe to assume Lorelai Gilmore herself would be a huge fan of this show.

'Grace and Frankie' (2015–2022)

They may not be mother and daughter, but Grace and Frankie have a very Emily-Lorelei thing going on. After their husbands reveal their longtime love for one another, the two women end up moving in together, setting up a personality clash for the ages: between elegant, uptight Grace (Jane Fonda) and free-spirited Frankie (Lily Tomlin).

'Hacks' (2021– )

For a slightly different take on a complex mother-daughter(-like) relationship, you must tune into Hacks . It stars Hannah Einbinder as Ava, an up-and-coming comedy writer who takes a job writing for Deborah (Jean Smart), a standup comedy legend whose popularity is starting to wane. Despite their constant butting of heads, the duo form a tight-knit bond based on their shared sense of very dry humor. And, just like in Gilmore Girls , the central pair are surrounded by a web of wacky characters—though Hacks ’ Kayla (Megan Stalter) makes GG ’s oddballs seem bland.

'The Handmaid’s Tale' (2017– )

Okay, so a dystopian tale about a society in which women are forced to serve as nothing more than birthing machines, are prohibited from reading or holding their own bank accounts, and, overall, are relegated to the fringes of society doesn’t exactly conjure the same cozy feeling as Gilmore Girls . But Rory G. herself (Alexis Bledel) does appear throughout the series, with her work on season 1 earning her her first Emmy. Plus, like Gilmore Girls , The Handmaid's Tale is powered by relationships between women, so…close enough?

'Hart of Dixie' (2011–2015)

You might feel a major sense of déjà vu when watching Hart of Dixie. Its storylines, pacing, small-town setting, and overall vibe are eerily similar to Gilmore Girls, making it one of your best options when you’ve convinced yourself to take a break from Stars Hollow…but don't want to.

'Jane the Virgin' (2014–2019)

Jane the Virgin might as well be called Villanueva Girls , since it, like Gilmore Girls , revolves around a responsible, book-obsessed daughter, the fun-loving mother who had her as a teenager, and the strict grandmother who doesn’t always approve of her progeny’s antics. Though, unlike Gilmore Girls , it takes a hilariously over-the-top, telenovela-style approach to telling the three women’s stories.

'Kim’s Convenience' (2016–2021)

Another family-centric show, Kim’s Convenience is a sitcom about the Korean-Canadian Kim family, who run—you guessed it—a convenience store in Toronto. In addition to being both funny and very heartwarming, it’s also where Simu Liu got his start before becoming a Marvel superstar. The first season holds a rare 100% on Rotten Tomatoes—all of which adds to a must-watch series .

'The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel' (2017–2023)

“Life’s short, talk fast” has long been hailed as an unofficial tagline for Gilmore Girls and its screwball comedy-inspired, relentlessly fast-paced dialogue, as established by creator Amy Sherman-Palladino. She may have outdone even herself in that category when she created The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel over a decade later: It stars Rachel Brosnahan as the titular character, a 1950s housewife who decides to chart a new course as a standup comedian after her husband leaves her—and who could easily go toe-to-toe with Lorelai Gilmore in a speed-talking and wit competition.

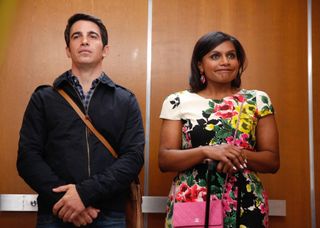

'The Mindy Project' (2012–2017)

Mindy Lahiri is like a Sliding Doors version of Lorelai Gilmore. They’re both intelligent, independent women who have great style, talk a mile a minute, and date a rotating cast of charming men who weave into and out of their lives—with both of their rosters led by grumpy but secretly sweet guys with whom they interact on a near-daily basis. Sold yet?

'Mike & Molly' (2010–2016)

She may have been largely absent from the Gilmore Girls reboot A Year in the Life , but Melissa McCarthy has stayed booked and busy since the show went off the air, giving us plenty more opportunities to revisit that Sookie St. James charm. She plays a similarly cheery character in Mike & Molly , a CBS sitcom that ran for six seasons and stars McCarthy and Billy Gardell as the titular characters, who meet in an Overeaters Anonymous meeting and promptly fall in love.

'Mom' (2013–2021)

If you’re after a complex mother-daughter relationship with plenty of comic relief, Mom is your show . It stars Anna Faris as Christy Plunkett. She moves to Napa to get her life together and reconnect with her estranged mother Bonnie, played by Allison Janney. Both mother and daughter are recovering addicts, and the core to repairing their relationship is their ritual of attending AA meetings together. The show strikes a near-perfect balance of exploring addiction and other serious issues with sensitivity and honesty, while also being hilarious.

'Never Have I Ever' (2020–2023)

This Mindy Kaling-created show is another take on the “multiple generations of women navigating their differences and finding common ground” plot. It centers around Maitreyi Ramakrishnan’s Devi, a high-achieving high school student, as she grapples with her grief over her father's death, her social standing and romantic pursuits, and her complicated relationship with her mother (Poorna Jagannathan).

'New Girl' (2011–2018)

The dearly beloved, extremely bingeable sitcom just might be the thing to fill that “fast-talking, tight-knit group of zany characters”-shaped hole in your heart. Plus, Jessica Day's (Zooey Deschanel) status as reigning queen of “adorkable” kitsch just might out-quirk Sookie and Kirk combined.

'Parenthood' (2010–2015)

After Gilmore Girls wrapped in 2007, Lauren Graham returned to TV just a few years later in another Lorelai-like role as Parenthood ’s Sarah Braverman, a single mother of two. The show—based on the 1989 film and 1990 series of the same name—follows three generations of the extended Braverman family and is filled with plenty of quirky characters, (usually) low-stakes drama and warm and fuzzy feelings of community.

'Parks and Recreation' (2009–2015)

Pawnee could absolutely give Stars Hollow a run for its money in the wacky department. Just like in Gilmore Girls , Parks and Recreation ’s core group of main characters is surrounded by a vast web of townspeople always ready to pop up when and where you least expect them, launch a truly ridiculous business venture, or take the weirdest stand possible at a local meeting.

'Riverdale' (2017–2023)

The town of Riverdale has the same cozy, always-autumnal small-town vibe as Stars Hollow, but it’s strange in its own, very unique way. In fact, the quirky characters of Gilmore Girls seem perfectly normal compared to the time travel, underground fight clubs, and haunted dolls of Riverdale —to name just a few of the unbelievably out-there plots that cropped up throughout its seven seasons.

'Schitt’s Creek' (2015–2020)

The Rosebud Motel may not be able to hold a candle to the Dragonfly Inn, but the Rose family’s motel does feature a staff of just as many eccentric characters as Lorelai Gilmore’s B&B. The same goes for the mother-daughter relationship between Moira and Alexis Rose (Catherine O'Hara and Annie Murphy )—they’re no Lorelai and Rory, but they occasionally have their moments.

'Sullivan’s Crossing' (2023– )

It’s nearly impossible to imagine Scott Patterson, a.k.a. Luke Danes, doing anything other than wearing flannels and being grumpy in a small town, and thankfully, we don’t have to. He fulfills a similar role in Sullivan’s Crossing as Sully, who finds himself repairing his estranged relationship with his neurosurgeon daughter (Morgan Kohan) when she unexpectedly returns to their rural Canadian town. Fun fact: The show is based on a series of books by Robyn Carr, who also wrote the books behind Virgin River , another very cozy Gilmore Girls follow-up.

'The Summer I Turned Pretty' (2022– )

If you think you have strong opinions on Rory’s boyfriends (Team Jess forever!), wait until you’ve plowed through this Amazon original based on Jenny Han's popular book series . You might be surprised at how powerfully you feel about whichever Fisher brother you’ve determined to be the best choice for Belly (played by Lola Tung). (The right answer is Jeremiah, obviously).

'Ted Lasso' (2020–2023)

One of the best things about Gilmore Girls is its innate kindness: Though the characters sometimes bicker and break apart, the show is never mean-spirited and typically leaves you happy. The same could be said of the hit comedy series Ted Lasso , which stars Jason Sudeikis as the relentlessly optimistic titular character. He plays an American football coach who accepts a job coaching a soccer team in the U.K., despite not knowing a thing about the sport.

'This Is Us' (2016–2022)

Keep a box of tissues close once you’ve hit play on This Is Us . The show’s six seasons jump back and forth in time, charting the complex, decades-long story of the Pearson family—led by Rebecca (Mandy Moore) and Jack (Jess Mariano himself, a.k.a. Milo Ventimiglia), with their three kids, Kate, Kevin, and Randall (played by Chrissy Metz, Justin Hartley, and Sterling K. Brown, respectively).

'Trying' (2020– )

This highly underrated British comedy is a perfect follow-up to the feel-good vibes of Gilmore Girls . It stars Esther Smith and Rafe Spall as Nikki and Jason, a couple struggling to conceive and turn instead to adoption, prompting three seasons’ worth of gentle chaos, hilarity, and sweet moments.

'Veronica Mars' (2004–2007)

Far from a feel-good mother-daughter dramedy, Veronica Mars follows its titular teen detective (Kristen Bell) as she solves mini-mysteries in each episode and unravels larger schemes throughout the course of each season. But now, on to the similarities: Like Gilmore Girls , it stars a precociously intelligent teenage girl (played by Kristen Bell) who’s unafraid to throw out an esoteric joke or pop culture reference that nobody else will get, it’s loaded with highly entertaining aughts fashion choices , and every episode starts with a theme song so catchy you won’t be able to resist singing along.

Andrea Park is a Chicago-based writer and reporter with a near-encyclopedic knowledge of the extended Kardashian-Jenner kingdom, early 2000s rom-coms and celebrity book club selections. She graduated from the Columbia School of Journalism in 2017 and has also written for W, Brides, Glamour, Women's Health, People and more.

"Most…told her what she already knew."

By Kristin Contino Published 24 October 24

She looks like a boss.

By Kelsey Stiegman Published 24 October 24

The sisters coordinated to celebrate Hailey Bieber's latest Rhode launch.

By Hanna Lustig Published 24 October 24

Here's when to tune in to the special episode.

By Quinci LeGardye Published 23 October 24

The 'SNL' alum opens up about playing the resident potions witch Jennifer Kale on the Disney+ hit.

The series centers on three hilarious therapists, played by Jason Segel, Jessica Williams, and Harrison Ford.

We're on the case of whether or not Mickey Haller and co. are coming back to Netflix.

By Quinci LeGardye Published 21 October 24

Nothing gets you ready for the spotlight like Shania Twain.

Grab some headphones and tune in.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published 21 October 24