- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

- What Does Depression Feel Like?

- Identify Your Emotions

- Cope With Your Emotions

- When You Feel Lonely

- When You Feel Emotional

- When You Feel Unappreciated

- When You Feel a Loss of Interest

- When You Feel Irritable

- When You Feel Tired

- When You Feel Worthless

- When You Feel Anxious

- When You Feel Unhappy

- When You Feel Helpless

- When You Feel Hopeless

Healthy Coping Skills for Uncomfortable Emotions

Emotion-Focused and Problem-Focused Strategies

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

- Emotion-Focused Skills

Healthy Problem-Focused Coping Skills

- Unhealthy Coping Skills

Proactive Coping Skills

- Find What Works

- Next in Small Ways to Feel Better When You're Depressed Guide 10 Things to Do When You Feel Alone

Whether you’ve been dumped by your date or you’ve had a rough day at the office, having healthy coping skills can be key to getting through tough times. Coping skills help you tolerate, minimize, and deal with stressful situations in life.

Coping skills are the tactics that people use to deal with stressful situations. Managing your stress well can help you feel better physically and psychologically and impact your ability to perform your best.

But not all coping skills are created equal. Sometimes, it’s tempting to engage in strategies that will give quick relief but might create bigger problems for you down the road. It’s important to establish healthy coping skills that will help you reduce your emotional distress or rid yourself of the stressful situations you face. Examples of healthy coping skills include:

- Establishing and maintaining boundaries

- Practicing relaxation strategies such as deep breathing, meditation, and mindfulness

- Getting regular physical activity

- Making to-do lists and setting goals

This article explores coping skills that can help you manage stress and challenges. Learn more about how different strategies, including problem-focused and emotion-focused skills, can be most helpful.

Verywell / Emily Roberts

Problem-Based vs. Emotion-Based

The five main types of coping skills are: problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, religious coping, meaning-making, and social support.

Two of the main types of coping skills are problem-based coping and emotion-based coping. Understanding how they differ can help you determine the best coping strategy for you.

- Problem-based coping is helpful when you need to change your situation, perhaps by removing a stressful thing from your life. For example, if you’re in an unhealthy relationship, your anxiety and sadness might be best resolved by ending the relationship (as opposed to soothing your emotions).

- Emotion-based coping is helpful when you need to take care of your feelings when you either don’t want to change your situation or when circumstances are out of your control. For example, if you are grieving the loss of a loved one, it’d be important to take care of your feelings in a healthy way (since you can’t change the circumstance).

There isn’t always one best way to proceed. Instead, it’s up to you to decide which type of coping skill is likely to work best for you in your particular circumstance. The following are examples of stressful situations and how each approach could be used.

Reading Your Performance Review

You open your email to find your annual performance review. The review states that you are below average in several areas and you’re surprised by this because you thought you were performing well. You feel anxious and frustrated.

- Problem-focused coping : You go to the boss and talk about what you can do to improve your performance. You develop a clear plan that will help you do better and you start to feel more confident about your ability to succeed.

- Emotion-focused coping : You spend your lunch break reading a book to distract yourself from catastrophic predictions that you’re going to be fired. After work, you exercise and clean the house as a way to help you feel better so you can think about the situation more clearly.

Getting a Teenager to Clean

You have told your teenager he needs to clean his bedroom. But it’s been a week and clothes and trash seem to be piling up. Before heading out the door in the morning, you told him he has to clean his room after school "or else." You arrive home from work to find him playing videos in his messy room.

- Problem-focused coping : You sit your teenager down and tell him that he’s going to be grounded until his room is clean. You take away his electronics and put him on restriction. In the meantime, you shut the door to his room so you don’t have to look at the mess.

- Emotion-focused coping : You decide to run some bathwater because a hot bath always helps you feel better. You know a bath will help you calm down so you don’t yell at him or overreact.

Giving a Presentation

You’ve been invited to give a presentation in front of a large group. You were so flattered and surprised by the invitation that you agreed to do it. But as the event approaches, your anxiety skyrockets because you hate public speaking .

- Problem-focused coping : You decide to hire a public speaking coach to help you learn how to write a good speech and how to deliver it confidently. You practice giving your speech in front of a few friends and family members so you will feel better prepared to step on stage.

- Emotion-focused coping : You tell yourself that you can do this. You practice relaxation exercises whenever you start to panic. And you remind yourself that even if you’re nervous, no one else is even likely to notice.

Problem-based coping skills focus on changing the situation, while emotional-based coping skills are centered on changing how you feel. Knowing which approach is right for a specific situation can help you deal with stress more effectively.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares how to face uncomfortable emotions, featuring comedian Paul Gilmartin.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

Healthy Emotion-Focused Coping Skills

Whether you’re feeling lonely , nervous, sad, or angry , emotion-focused coping skills can help you deal with your feelings in a healthy way. Healthy coping strategies may soothe you, temporarily distract you, or help you tolerate your distress.

Sometimes it’s helpful to face your emotions head-on. For example, feeling sad after the death of a loved one can help you honor your loss.

So while it would be important to use coping skills to help relieve some of your distress, coping strategies shouldn’t be about constantly distracting you from reality.

Other times, coping skills may help you change your mood. If you’ve had a bad day at work, playing with your kids or watching a funny movie might cheer you up. Or, if you’re angry about something someone said, a healthy coping strategy might help you calm down before you say something you might regret.

Other examples of healthy ways to cope with emotions include:

- Care for yourself : Put on lotion that smells good, spend time in nature, take a bath, drink tea, or take care of your body in a way that makes you feel good such as painting your nails, doing your hair, putting on a face mask.

- Engage in a hobby : Do something you enjoy such as coloring, drawing, or listening to music .

- Exercise : Do yoga, go for a walk, take a hike, or engage in a recreational sport.

- Focus on a task : Clean the house (or a closet, drawer, or area), cook a meal, garden, or read a book.

- Practice mindfulness : List the things you feel grateful for, meditate , picture your "happy place," or look at pictures to remind you of the people, places, and things that bring joy.

- Use relaxation strategies : Play with a pet, practice breathing exercises, squeeze a stress ball, use a relaxation app, enjoy some aromatherapy, try progressive muscle relaxation , or write in a journal.

There are many ways you might decide to tackle a problem head-on and eliminate the source of your stress. In some cases, that may mean changing your behavior or creating a plan that helps you know what action you’re going to take.

In other situations, problem-focused coping may involve more drastic measures, like changing jobs or ending a relationship. Here are some examples of positive problem-focused coping skills:

- Ask for support from a friend or a professional.

- Create a to-do list.

- Engage in problem-solving.

- Establish healthy boundaries .

- Walk away and leave a situation that is causing you stress.

- Work on managing your time better.

Whether emotion-focused or problem-focused, healthy coping skills should help calm stress without avoiding the issue. The right coping skill often depends on the situation and your specific needs in the moment.

Unhealthy Coping Skills to Avoid

Just because a strategy helps you endure emotional pain, it doesn’t mean it’s healthy. Some coping skills could create bigger problems in your life. Here are some examples of unhealthy coping skills:

- Drinking alcohol or using drugs : Substances may temporarily numb your pain, but they won’t resolve your issues. Substances are likely to introduce new problems into your life. Alcohol, for example, is a depressant that can make you feel worse. Using substances to cope also puts you at risk for developing a substance use disorder and it may create health, legal, financial problems, and social problems.

- Overeating : Food is a common coping strategy. But, trying to "stuff your feelings" with food can lead to an unhealthy relationship with food and health issues. Sometimes people go to the other extreme and restrict their eating (because it makes them feel more in control) and clearly, that can be just as unhealthy.

- Sleeping too much : Whether you take a nap when you’re stressed out or you sleep late to avoid facing the day, sleeping offers a temporary escape from your problems. However, when you wake up, the problem will still be there.

- Venting to others : Talking about your problems so that you can gain support, develop a solution, or see a problem in a different way can be healthy. But studies show repeatedly venting to people about how bad your situation is or how terrible you feel is more likely to keep you stuck in a place of pain.

- Overspending : While many people say they enjoy retail therapy as a way to feel better, shopping can become unhealthy. Owning too many possessions can add stress to your life. Also, spending more than you can afford will only backfire in the end and cause more stress.

- Avoiding : Even “healthy” coping strategies can become unhealthy if you’re using them to avoid the problem. For example, if you are stressed about your financial situation, you might be tempted to spend time with friends or watch TV because that’s less anxiety-provoking than creating a budget. But if you never resolve your financial issues, your coping strategies are only masking the problem.

Unhealthy coping techniques—such as drinking or avoiding the problem—may offer some temporary relief, but they tend to make things worse in the long run. These unhealthy tactics can also lead to other problems that create more stress and make coping more difficult.

Coping skills are usually discussed as a reactive strategy: When you feel bad, you do something to cope. But, research shows that proactive coping strategies can effectively manage the future obstacles you’re likely to face.

For example, if you have worked hard to lose weight, proactive coping strategies could help you maintain your weight after your weight loss program has ended. You might plan for circumstances that might derail you—like the holiday season or dinner invitations from friends—to help you cope. You also might plan for how you will cope with emotions that previously caused you to snack, like boredom or loneliness.

Proactive coping can also help people deal with unexpected life changes, such as a major change in health. A 2014 study found that people who engaged with proactive coping were better able to deal with the changes they encountered after having a stroke.

Another study found that people who engaged in proactive coping were better equipped to manage their type 2 diabetes. Participants who planned ahead and set realistic goals enjoyed better psychological well-being.

So, if you are facing a stressful life event or you’ve undergone a major change, try planning ahead. Consider the skills you can use to cope with the challenges you’re likely to face. When you have a toolbox ready to go, you’ll know what to do. And that could help you to feel better equipped to face the challenges ahead.

Proactive coping has been found to be an effective way to help people deal with both predictable changes like a decline in income during retirement, as well as unpredictable life changes such as the onset of a chronic health condition.

Find What Works for You

The coping strategies that work for someone else might not work for you. Going for a walk might help your partner calm down. But you might find going for a walk when you’re angry causes you to think more about why you’re mad—and it fuels your angry feelings. So you might decide watching a funny video for a few minutes helps you relax.

You might find that certain coping strategies work best for specific issues or emotions. For example, engaging in a hobby may be an effective way to unwind after a long day at work. But, going for a walk in nature might be the best approach when you’re feeling sad.

When it comes to coping skills, there’s always room for improvement. So, assess what other tools and resources you can use and consider how you might continue to sharpen your skills in the future.

It's important to develop your own toolkit of coping skills that you’ll find useful. You may need to experiment with a variety of coping strategies to help you discover which ones work best for you.

A Word From Verywell

Healthy coping skills can help protect you from distress and face problems before they become more serious. By understanding the two main types of coping skills, you can better select strategies that are suited to different types of stress.

If you are struggling to practice healthy coping skills or find yourself relying on unhealthy ones instead, talking to a mental health professional can be helpful. A therapist can work with you to develop new skills that will serve your mental well-being for years to come.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

Aldwin CM, Yancura LA. Coping . In: Encyclopedia of Applied Psychology . Elsevier; 2004:507-510. doi:10.1016/B0-12-657410-3/00126-4

Byrd-Craven J, Geary DC, Rose AJ, Ponzi D. Co-ruminating increases stress hormone levels in women . Horm Behav . 2008;53(3):489-92. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.12.002

Drummond S, Brough P. Proactive coping and preventive coping: Evidence for two distinct constructs? . Personality and Individual Differences . 2016;92:123-127. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.029.

Tielemans NS, Visser-Meily JM, Schepers VP, Post MW, van Heugten CM. Proactive coping poststroke: Psychometric properties of the Utrecht Proactive Coping Competence Scale . Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(4):670-5. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2013.11.010

By Amy Morin, LCSW Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

E9: Problem Solving

Virtual Coach

Work step-by-step through the Emotion Regulation exercise with the virtual coach.

Introduction

In the previous exercises from Emotion Regulation , we worked on recognizing certain situations that are triggering and causing us to feel overwhelming emotions. This is helpful because once we know that certain situation can be potentially problematic for us, then we can also work on doing something before the situation happens again - a type of preparation. This is exactly what we are going to be working on in this exercise. Getting prepared beforehand can give us a sense of control over the triggering situation that is about to happen. We will go through four steps that are going to help you solve the problematic situation before it happens.

Instructions

Step one: behavior analysis.

Take your time and try to remember what usually causes you to feel ineffectively overwhelmed. Is it an event with your family, a work situation, your kids or your friends? Next, write down the emotion that you are usually experiencing. Maybe you feel intensively angry, rejected or abandoned, or depressed and anxious. Try to remember how the situation usually takes place and what your ongoing fleeting feelings and thoughts are while the situation is happening.

Example : Event : My husband criticizes my looks. He makes a subtle comment that I should lose weight and that I should dress differently. Main emotion : Anger Other emotions and thoughts during the event : At first, I low-key agree with him and I think how fat and ugly I look. I've always hated my body. Before my anger strikes I feel ashamed and sad.

Step Two: What Can I Change?

What out of the three elements from the previous step can you change? Bear in mind that the change that you can potentially make should eventually improve your emotional health and your immediate overwhelming emotion.

Sometimes it's impossible to change the external event , but we can work on our thoughts and how we talk to ourselves internally during the situation. Pick two things out of the elements in the previous step that you think are the most suitable for you to try to change.

In the previous example, the person cannot control what her husband says to her. What she can work on though, is the messages she directs towards herself about her appearance. At the same time, she will also work on the feelings of shame and sadness that are occurring during the event.

Step Three: Brainstorming Alternatives

Now that you have identified the two aspects that you can and would like to change, it's time to brainstorm for alternative ideas. If you chose to work on the occurring thoughts, what else can you say to yourself about the situation? What can you remind yourself of in order to objectify the all-or-nothing thinking or the generalizations you make? Perhaps you want to change the event and do something differently than what you usually does.

In the example we presented, the alternative and objective thoughts that the woman can remind herself of would be: - "He has no right to make such aggressive comments and body shame me." - "Even though his tone was seemingly polite, it is not okay to say things like that to your significant other. It's still passive aggressive." - "I don't have to look a certain way unless I want to. My body serves me in great ways and I am grateful that I am physically healthy." - "There are many great aspects about me, I am sociable and charming." - "This trend to be thin will probably have a cultural shift and it will change. It's just a societal pressure and conditioning and I really am smarter than that!"

Step Four: Put the Solution into Action

After you have brainstormed for ideas about what you can do to change the aspects that are changeable, choose what works best for you and try to put the solution into action. Actively decide and remind yourself to act the way you decided to next time you find yourself in the situation.

For example: "Now that I've straightened some of the incorrect ways in which I am thinking about my body, I want to try and remind myself more often of what I actually believe in. Maybe next time this happens I can communicate to my husband what my thoughts are in a polite way and not get angry and make mean comments to hurt him back. I will assertively put boundaries about what is acceptable and what is not."

Worksheet & Virtual Coach

Use the worksheet to help you prepare for situations that you expect to be difficult.

DBT Virtual Coach

Do the Mindfulness exercise with our new virtual coach.

How should I know which aspect of the situation should I work on changing? I am not sure which one is the most suitable.

Start with the things you have control over. For example, our thoughts and the resulting feelings are usually something we can work on (trying to straighten the cognitive distortions present). You can benefit from the exercise about cognitive vulnerability that we previously worked on in this module. Sometimes the way in which other people consistently behave is out of our control. That is not to say that we shouldn't try to communicate our boundaries. You can also work on changing the way you behave in and do something differently. For example you can walk out of a situation that is harmful to you (if possible).

I can't think of alternatives, my brainstorming session is a little dry.

You can try asking somebody you trust and you know has your back about ideas about the situation. If you regularly put yourself down with the way you think about yourself and the way you interpret the events around you, then you can try thinking about what advice you would give a friend of yours who is in the same situation. Remember that the potential solution to the problem should eventually improve the situation for you and help you with the overwhelming emotion you usually experience. For example, in the body-shaming example we presented, if the woman shamed herself into losing a lot of weight, she would still end up with negative emotions, so that would not be the best solution for her.

What if I can't remember to try the solution I've come up with next time I find myself in the problematic situation?

It is okay if you need some time to get used to implementing the solution. Quality change doesn't come with little effort. If you don't remember to implement the solution the first time, just remind yourself that that is totally fine, be patient and try it again next time. Maybe the first couple of times you won't end up with the emotion you would eventually like to feel, but remember that this is a skill and it can be learned through practice.

If you have any behavioral health questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare or mental health care provider. This article is supported by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from behavioral health societies and governmental agencies. However, it is not a substitute for professional behavioral health advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Comments about Problem Solving

Hey im here postpartum depression

Hi Jocelyn, I hope you were able to get the help you needed, Postpartum depression is not fun. I see this comment was from 2 months ago, baby must be getting big, and smiling by now.

"Going through all the DBT worksheets really helped me rethink the way I was approaching my life. Thank you!"

- Tillie S.

"Life changer! I struggled with depression and anxiety before I did this course. Do it!"

- Suzanne R.

"I started doing your worksheets a month ago. My therapist says they helped us make faster progress in our sessions."

- Eduardo D.

"Stick with it. It really works. Doing these exercises every day helped me get over a really bad spell of depression."

- Juliana D.

- MINDFULNESS

- INTERPERSONAL

Thank You for Subscribing!

Please click the verification link in the email we just sent you. This step confirms your opt-in to our subscriber list.

Your 26-week DBT course awaits!

Didn't receive the email? Check your spam or junk folder, and mark our email as 'Not Spam' to ensure you don't miss any future updates.

Get the DBT course. Free!

Get your full access to our 26-week DBT course. Lessons emailed to you twice a week.

Subscribe. Get the DBT course. Free!

- NeuroLaunch

Emotional Problems: Recognizing, Understanding, and Overcoming Mental Health Challenges

- Emotional Therapy

- NeuroLaunch editorial team

- October 18, 2024

- Leave a Comment

Table of Contents

From the depths of the human psyche, a tempest of emotions can surge, threatening to engulf even the most resilient among us in a maelstrom of mental anguish. This tumultuous sea of feelings, often referred to as emotional problems, can leave us feeling adrift and overwhelmed, struggling to find our bearings in the choppy waters of life.

Emotional problems are more than just fleeting moments of sadness or anxiety. They’re persistent disturbances in our psychological well-being that can significantly impact our daily lives. These issues can range from the subtle undercurrents of low-grade stress to the crushing waves of severe depression. And let’s face it, in today’s fast-paced, high-pressure world, it’s no wonder that so many of us find ourselves treading water in this emotional ocean.

The prevalence of emotional issues in our society is staggering. It’s like we’re all swimming in a vast pool of collective angst, with countless individuals silently struggling beneath the surface. According to recent studies, nearly one in five adults in the United States experiences some form of mental illness each year. That’s a lot of people trying to keep their heads above water!

But here’s the kicker: addressing these emotional problems isn’t just a nice-to-have; it’s absolutely crucial for our overall well-being. Imagine trying to build a sandcastle while the tide is coming in – that’s what it’s like trying to live a fulfilling life while ignoring our emotional health. It’s a Sisyphean task, doomed to failure.

The Many Faces of Emotional Turmoil

When it comes to emotional problems, there’s no one-size-fits-all description. These issues come in more flavors than a gourmet ice cream shop, each with its own unique blend of symptoms and challenges. Let’s take a whirlwind tour through some of the most common types of emotional problems that can turn our inner world upside down.

First up, we have anxiety disorders – the jittery, heart-racing, palm-sweating experiences that can make even the most mundane tasks feel like scaling Mount Everest. It’s like having an overactive alarm system in your brain, constantly screaming “Danger!” even when you’re just trying to order a coffee.

Then there’s depression and mood disorders, the heavy, gray clouds that can blot out the sun in our emotional sky. These conditions can drain the color from our world, leaving us feeling empty, hopeless, and about as energetic as a sloth on a lazy Sunday. Garden Variety Emotional Distress: Navigating Common Mental Health Challenges often includes milder forms of these mood disturbances, which, while less severe, can still significantly impact our daily lives.

Stress-related emotional issues are like the annoying background noise of modern life – always there, always grating on our nerves. It’s the constant hum of worry about work, relationships, finances, and that weird noise your car’s been making lately. Over time, this stress can wear us down like water eroding a rock, leaving us feeling frazzled and burnt out.

Anger management problems are the emotional equivalent of a volcano – sometimes dormant, but always with the potential to erupt spectacularly. These issues can turn even the mildest-mannered person into a fire-breathing dragon at the slightest provocation.

And let’s not forget about low self-esteem and self-worth issues. These are the sneaky saboteurs of our emotional well-being, whispering constant criticisms and undermining our confidence. It’s like having a personal rain cloud following you around, dampening your spirits wherever you go.

Spotting the Signs: When Emotions Go Rogue

Recognizing the signs and symptoms of emotional problems can be trickier than solving a Rubik’s cube blindfolded. Our emotions don’t come with warning labels or flashing neon signs. Instead, they often manifest in subtle ways that can be easy to miss or dismiss.

Physical symptoms are often the first clues that something’s amiss in our emotional world. Fatigue that no amount of coffee can cure, headaches that feel like a marching band is practicing in your skull, and sleep disturbances that leave you feeling like a zombie – these can all be red flags waving frantically in the breeze of our consciousness.

Behavioral changes are another tell-tale sign that our emotions are doing the cha-cha when they should be waltzing. Suddenly, the idea of socializing feels about as appealing as getting a root canal, and your usual patience has been replaced by a hair-trigger temper. It’s like your personality has been hijacked by a grumpy doppelganger.

Cognitive symptoms can turn your usually sharp mind into a foggy swamp. Concentrating becomes as challenging as herding cats, and your thoughts start to resemble a doom-and-gloom news channel, broadcasting negativity 24/7. It’s as if your brain has decided to take an extended vacation without your permission.

Emotional indicators are perhaps the most obvious signs, but they can still be tricky to pin down. Persistent sadness that clings to you like a wet blanket, mood swings that rival a rollercoaster, and a general feeling of “blah” that no amount of cute cat videos can shake – these are all potential signs that your emotional health needs some TLC.

The impact on daily functioning and relationships can be profound. Suddenly, getting out of bed feels like an Olympic sport, and maintaining friendships seems as complicated as quantum physics. It’s like trying to navigate life with a faulty GPS – you know where you want to go, but you keep ending up in all the wrong places.

The Perfect Storm: Factors Behind Emotional Turbulence

Understanding the factors that contribute to emotional problems is like trying to predict the weather – it’s a complex interplay of various elements, each influencing the others in subtle and not-so-subtle ways.

Genetic predisposition plays a role, like the underlying current in a river. Some of us may be more susceptible to certain emotional issues thanks to the genetic lottery. It’s not a guarantee, but it can stack the deck in favor of developing certain problems.

Environmental factors and life experiences are like the wind and waves shaping our emotional landscape. Traumatic events, chronic stress, and adverse childhood experiences can carve deep grooves in our psyche, creating patterns that can be hard to break. Emotional Issues and Bathroom Problems: The Hidden Connection highlights how even seemingly unrelated aspects of our lives can be intertwined with our emotional health.

Chronic stress and lifestyle factors are the daily grind that can wear down our emotional resilience. It’s like trying to run a marathon while wearing lead shoes – eventually, even the strongest among us will start to falter.

Neurochemical imbalances and brain function add another layer of complexity to the mix. Our brains are like incredibly sophisticated chemical factories, and when the production line gets out of whack, it can throw our entire emotional ecosystem off balance.

Charting a Course to Calmer Waters

Now that we’ve navigated the stormy seas of emotional problems, it’s time to plot a course towards calmer waters. Managing and overcoming these issues isn’t always easy, but with the right strategies and support, it’s absolutely possible to find your emotional equilibrium.

First and foremost, seeking professional help is like calling in a seasoned captain to guide your ship. Therapists, counselors, and psychiatrists are trained to navigate the treacherous waters of mental health, and they can provide invaluable support and guidance. Don’t be afraid to reach out – it’s a sign of strength, not weakness.

Developing healthy coping mechanisms is like building a sturdy lifeboat. These are the skills and techniques that can keep you afloat when emotional storms hit. Whether it’s practicing mindfulness, journaling, or engaging in creative pursuits, finding healthy ways to process and express your emotions is crucial.

Practicing self-care and stress management techniques is the emotional equivalent of regular ship maintenance. It’s about taking care of yourself on a daily basis to prevent small issues from turning into major problems. This might include things like regular exercise, getting enough sleep, and setting boundaries to protect your mental energy.

Building a strong support network is like assembling a crew for your emotional journey. Surrounding yourself with understanding friends, family members, or support groups can provide a lifeline when you’re feeling overwhelmed. Remember, we’re social creatures – we’re not meant to navigate life’s challenges alone.

Lifestyle changes can be like adjusting your sails to catch more favorable winds. This might involve reassessing your work-life balance, incorporating relaxation techniques into your daily routine, or making dietary changes to support your mental health. Small tweaks can often lead to significant improvements in your overall emotional well-being.

Navigating the Treatment Seas

When it comes to treating emotional problems, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. It’s more like a buffet of options, each with its own flavors and benefits. The key is finding the right combination that works for you.

Psychotherapy approaches are like different navigation techniques for your emotional journey. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) helps you chart a new course by changing negative thought patterns. Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) teaches you to navigate the choppy waters of intense emotions. Interpersonal therapy focuses on improving your relationships with others – because let’s face it, other people can be both our greatest source of joy and our biggest emotional challenges.

For some, medication options might be necessary, especially for severe emotional problems. It’s like adding a motor to your sailboat – sometimes you need that extra boost to get through particularly rough patches. Of course, medication should always be prescribed and monitored by a qualified healthcare professional.

Alternative and complementary therapies can be like the spices that add flavor to your emotional health regimen. These might include practices like acupuncture, meditation, or art therapy. While they may not be the main course, they can certainly enhance your overall treatment plan.

Support groups and peer counseling offer a chance to connect with others who are navigating similar emotional waters. It’s like joining a flotilla – you’re still steering your own ship, but you’ve got company on the journey. Sharing experiences and coping strategies can be incredibly empowering and validating.

Self-help resources and tools are like having a personal navigation system for your emotional health. Books, apps, and online resources can provide valuable insights and techniques for managing your emotions. Just remember, while these can be great supplements, they’re not substitutes for professional help when it’s needed.

Charting a Course for Emotional Well-being

As we sail towards the conclusion of our journey through the seas of emotional problems, it’s important to remember that early intervention is key. It’s like spotting a storm on the horizon – the sooner you take action, the better your chances of weathering it successfully.

We need to encourage a proactive approach to mental health. Regular emotional check-ins should be as normal as annual physical exams. After all, our minds deserve just as much care and attention as our bodies.

Reducing the stigma surrounding emotional issues is crucial. It’s time to toss outdated notions overboard and recognize that seeking help for mental health is a sign of strength, not weakness. Emotional Cutting: Understanding and Addressing a Form of Self-Harm is just one example of the complex issues that require compassion and understanding rather than judgment.

Empowering individuals to seek help and support is like giving everyone a map and compass for their emotional journey. Education, awareness, and accessible resources are all vital components in this effort.

Finally, let’s not forget the most important message of all – there is hope for recovery and improved emotional well-being. 5 Signs of Emotional Suffering: Recognizing and Addressing Mental Health Challenges can help you identify when you or a loved one might need support. Even in the darkest emotional storms, remember that calmer waters lie ahead.

The journey to emotional health may not always be smooth sailing, but with the right tools, support, and mindset, it’s a voyage well worth undertaking. After all, our emotional well-being is the wind in our sails, propelling us towards a life of fulfillment, connection, and joy.

So, dear reader, as you navigate your own emotional seas, remember that you’re not alone in this journey. Whether you’re dealing with Advanced Emotional Deterioration: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment Strategies or simply trying to maintain your day-to-day emotional balance, there are resources and support available.

Consider reaching out to an Emotional Psychologist: Experts in Understanding and Healing the Human Psyche for professional guidance. And remember, emotional health can impact all aspects of our lives, even in unexpected ways. For instance, Emotional ED: Navigating the Intersection of Emotions and Erectile Dysfunction explores how our emotional state can affect our physical well-being.

As we conclude this exploration of emotional problems, let’s set sail with hope in our hearts and determination in our spirits. The sea of emotions may be vast and sometimes turbulent, but with understanding, support, and the right tools, we can navigate it successfully. Here’s to smoother sailing and sunnier skies on your emotional journey!

References:

1. National Institute of Mental Health. (2021). Mental Illness. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness

2. American Psychological Association. (2020). Understanding psychotherapy and how it works. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/topics/psychotherapy

3. World Health Organization. (2022). Mental health: strengthening our response. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

4. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

5. Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

6. Linehan, M. M. (2014). DBT Skills Training Manual. Guilford Press.

7. Seligman, M. E. P. (2012). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. Free Press.

8. National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2022). Mental Health By the Numbers. Retrieved from https://www.nami.org/mhstats

9. Harvard Health Publishing. (2021). Understanding the stress response. Harvard Medical School.

10. Hari, J. (2018). Lost Connections: Uncovering the Real Causes of Depression – and the Unexpected Solutions. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Cookie Policy

About NeuroLaunch

- Copyright Notice

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise With Us

- Mental Health

10 Best Problem-Solving Therapy Worksheets & Activities

Cognitive science tells us that we regularly face not only well-defined problems but, importantly, many that are ill defined (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

Sometimes, we find ourselves unable to overcome our daily problems or the inevitable (though hopefully infrequent) life traumas we face.

Problem-Solving Therapy aims to reduce the incidence and impact of mental health disorders and improve wellbeing by helping clients face life’s difficulties (Dobson, 2011).

This article introduces Problem-Solving Therapy and offers techniques, activities, and worksheets that mental health professionals can use with clients.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is problem-solving therapy, 14 steps for problem-solving therapy, 3 best interventions and techniques, 7 activities and worksheets for your session, fascinating books on the topic, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

Problem-Solving Therapy assumes that mental disorders arise in response to ineffective or maladaptive coping. By adopting a more realistic and optimistic view of coping, individuals can understand the role of emotions and develop actions to reduce distress and maintain mental wellbeing (Nezu & Nezu, 2009).

“Problem-solving therapy (PST) is a psychosocial intervention, generally considered to be under a cognitive-behavioral umbrella” (Nezu, Nezu, & D’Zurilla, 2013, p. ix). It aims to encourage the client to cope better with day-to-day problems and traumatic events and reduce their impact on mental and physical wellbeing.

Clinical research, counseling, and health psychology have shown PST to be highly effective in clients of all ages, ranging from children to the elderly, across multiple clinical settings, including schizophrenia, stress, and anxiety disorders (Dobson, 2011).

Can it help with depression?

PST appears particularly helpful in treating clients with depression. A recent analysis of 30 studies found that PST was an effective treatment with a similar degree of success as other successful therapies targeting depression (Cuijpers, Wit, Kleiboer, Karyotaki, & Ebert, 2020).

Other studies confirm the value of PST and its effectiveness at treating depression in multiple age groups and its capacity to combine with other therapies, including drug treatments (Dobson, 2011).

The major concepts

Effective coping varies depending on the situation, and treatment typically focuses on improving the environment and reducing emotional distress (Dobson, 2011).

PST is based on two overlapping models:

Social problem-solving model

This model focuses on solving the problem “as it occurs in the natural social environment,” combined with a general coping strategy and a method of self-control (Dobson, 2011, p. 198).

The model includes three central concepts:

- Social problem-solving

- The problem

- The solution

The model is a “self-directed cognitive-behavioral process by which an individual, couple, or group attempts to identify or discover effective solutions for specific problems encountered in everyday living” (Dobson, 2011, p. 199).

Relational problem-solving model

The theory of PST is underpinned by a relational problem-solving model, whereby stress is viewed in terms of the relationships between three factors:

- Stressful life events

- Emotional distress and wellbeing

- Problem-solving coping

Therefore, when a significant adverse life event occurs, it may require “sweeping readjustments in a person’s life” (Dobson, 2011, p. 202).

- Enhance positive problem orientation

- Decrease negative orientation

- Foster ability to apply rational problem-solving skills

- Reduce the tendency to avoid problem-solving

- Minimize the tendency to be careless and impulsive

D’Zurilla’s and Nezu’s model includes (modified from Dobson, 2011):

- Initial structuring Establish a positive therapeutic relationship that encourages optimism and explains the PST approach.

- Assessment Formally and informally assess areas of stress in the client’s life and their problem-solving strengths and weaknesses.

- Obstacles to effective problem-solving Explore typically human challenges to problem-solving, such as multitasking and the negative impact of stress. Introduce tools that can help, such as making lists, visualization, and breaking complex problems down.

- Problem orientation – fostering self-efficacy Introduce the importance of a positive problem orientation, adopting tools, such as visualization, to promote self-efficacy.

- Problem orientation – recognizing problems Help clients recognize issues as they occur and use problem checklists to ‘normalize’ the experience.

- Problem orientation – seeing problems as challenges Encourage clients to break free of harmful and restricted ways of thinking while learning how to argue from another point of view.

- Problem orientation – use and control emotions Help clients understand the role of emotions in problem-solving, including using feelings to inform the process and managing disruptive emotions (such as cognitive reframing and relaxation exercises).

- Problem orientation – stop and think Teach clients how to reduce impulsive and avoidance tendencies (visualizing a stop sign or traffic light).

- Problem definition and formulation Encourage an understanding of the nature of problems and set realistic goals and objectives.

- Generation of alternatives Work with clients to help them recognize the wide range of potential solutions to each problem (for example, brainstorming).

- Decision-making Encourage better decision-making through an improved understanding of the consequences of decisions and the value and likelihood of different outcomes.

- Solution implementation and verification Foster the client’s ability to carry out a solution plan, monitor its outcome, evaluate its effectiveness, and use self-reinforcement to increase the chance of success.

- Guided practice Encourage the application of problem-solving skills across multiple domains and future stressful problems.

- Rapid problem-solving Teach clients how to apply problem-solving questions and guidelines quickly in any given situation.

Success in PST depends on the effectiveness of its implementation; using the right approach is crucial (Dobson, 2011).

Problem-solving therapy – Baycrest

The following interventions and techniques are helpful when implementing more effective problem-solving approaches in client’s lives.

First, it is essential to consider if PST is the best approach for the client, based on the problems they present.

Is PPT appropriate?

It is vital to consider whether PST is appropriate for the client’s situation. Therapists new to the approach may require additional guidance (Nezu et al., 2013).

Therapists should consider the following questions before beginning PST with a client (modified from Nezu et al., 2013):

- Has PST proven effective in the past for the problem? For example, research has shown success with depression, generalized anxiety, back pain, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and supporting caregivers (Nezu et al., 2013).

- Is PST acceptable to the client?

- Is the individual experiencing a significant mental or physical health problem?

All affirmative answers suggest that PST would be a helpful technique to apply in this instance.

Five problem-solving steps

The following five steps are valuable when working with clients to help them cope with and manage their environment (modified from Dobson, 2011).

Ask the client to consider the following points (forming the acronym ADAPT) when confronted by a problem:

- Attitude Aim to adopt a positive, optimistic attitude to the problem and problem-solving process.

- Define Obtain all required facts and details of potential obstacles to define the problem.

- Alternatives Identify various alternative solutions and actions to overcome the obstacle and achieve the problem-solving goal.

- Predict Predict each alternative’s positive and negative outcomes and choose the one most likely to achieve the goal and maximize the benefits.

- Try out Once selected, try out the solution and monitor its effectiveness while engaging in self-reinforcement.

If the client is not satisfied with their solution, they can return to step ‘A’ and find a more appropriate solution.

The New Low-Effort, High-Impact Wellbeing Program.

Wellbeing X© is a seven-session, science-based training template. It contains everything you need to position yourself as a wellbeing expert and deliver a scalable, high-impact program to help others develop sustainable wellbeing.

Positive self-statements

When dealing with clients facing negative self-beliefs, it can be helpful for them to use positive self-statements.

Use the following (or add new) self-statements to replace harmful, negative thinking (modified from Dobson, 2011):

- I can solve this problem; I’ve tackled similar ones before.

- I can cope with this.

- I just need to take a breath and relax.

- Once I start, it will be easier.

- It’s okay to look out for myself.

- I can get help if needed.

- Other people feel the same way I do.

- I’ll take one piece of the problem at a time.

- I can keep my fears in check.

- I don’t need to please everyone.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

PST practitioners have many different techniques available to support clients as they learn to tackle day-to-day or one-off trauma.

5 Worksheets and workbooks

Problem-solving self-monitoring form.

Ask the client to complete the following:

- Describe the problem you are facing.

- What is your goal?

- What have you tried so far to solve the problem?

- What was the outcome?

Reactions to Stress

It can be helpful for the client to recognize their own experiences of stress. Do they react angrily, withdraw, or give up (Dobson, 2011)?

The Reactions to Stress worksheet can be given to the client as homework to capture stressful events and their reactions. By recording how they felt, behaved, and thought, they can recognize repeating patterns.

What Are Your Unique Triggers?

Helping clients capture triggers for their stressful reactions can encourage emotional regulation.

When clients can identify triggers that may lead to a negative response, they can stop the experience or slow down their emotional reaction (Dobson, 2011).

The What Are Your Unique Triggers ? worksheet helps the client identify their triggers (e.g., conflict, relationships, physical environment, etc.).

Problem-Solving worksheet

Imagining an existing or potential problem and working through how to resolve it can be a powerful exercise for the client.

Use the Problem-Solving worksheet to state a problem and goal and consider the obstacles in the way. Then explore options for achieving the goal, along with their pros and cons, to assess the best action plan.

Getting the Facts

Clients can become better equipped to tackle problems and choose the right course of action by recognizing facts versus assumptions and gathering all the necessary information (Dobson, 2011).

Use the Getting the Facts worksheet to answer the following questions clearly and unambiguously:

- Who is involved?

- What did or did not happen, and how did it bother you?

- Where did it happen?

- When did it happen?

- Why did it happen?

- How did you respond?

2 Helpful Group Activities

While therapists can use the worksheets above in group situations, the following two interventions work particularly well with more than one person.

Generating Alternative Solutions and Better Decision-Making

A group setting can provide an ideal opportunity to share a problem and identify potential solutions arising from multiple perspectives.

Use the Generating Alternative Solutions and Better Decision-Making worksheet and ask the client to explain the situation or problem to the group and the obstacles in the way.

Once the approaches are captured and reviewed, the individual can share their decision-making process with the group if they want further feedback.

Visualization

Visualization can be performed with individuals or in a group setting to help clients solve problems in multiple ways, including (Dobson, 2011):

- Clarifying the problem by looking at it from multiple perspectives

- Rehearsing a solution in the mind to improve and get more practice

- Visualizing a ‘safe place’ for relaxation, slowing down, and stress management

Guided imagery is particularly valuable for encouraging the group to take a ‘mental vacation’ and let go of stress.

Ask the group to begin with slow, deep breathing that fills the entire diaphragm. Then ask them to visualize a favorite scene (real or imagined) that makes them feel relaxed, perhaps beside a gently flowing river, a summer meadow, or at the beach.

The more the senses are engaged, the more real the experience. Ask the group to think about what they can hear, see, touch, smell, and even taste.

Encourage them to experience the situation as fully as possible, immersing themselves and enjoying their place of safety.

Such feelings of relaxation may be able to help clients fall asleep, relieve stress, and become more ready to solve problems.

We have included three of our favorite books on the subject of Problem-Solving Therapy below.

1. Problem-Solving Therapy: A Treatment Manual – Arthur Nezu, Christine Maguth Nezu, and Thomas D’Zurilla

This is an incredibly valuable book for anyone wishing to understand the principles and practice behind PST.

Written by the co-developers of PST, the manual provides powerful toolkits to overcome cognitive overload, emotional dysregulation, and the barriers to practical problem-solving.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. Emotion-Centered Problem-Solving Therapy: Treatment Guidelines – Arthur Nezu and Christine Maguth Nezu

Another, more recent, book from the creators of PST, this text includes important advances in neuroscience underpinning the role of emotion in behavioral treatment.

Along with clinical examples, the book also includes crucial toolkits that form part of a stepped model for the application of PST.

3. Handbook of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies – Keith Dobson and David Dozois

This is the fourth edition of a hugely popular guide to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies and includes a valuable and insightful section on Problem-Solving Therapy.

This is an important book for students and more experienced therapists wishing to form a high-level and in-depth understanding of the tools and techniques available to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapists.

For even more tools to help strengthen your clients’ problem-solving skills, check out the following free worksheets from our blog.

- Case Formulation Worksheet This worksheet presents a four-step framework to help therapists and their clients come to a shared understanding of the client’s presenting problem.

- Understanding Your Default Problem-Solving Approach This worksheet poses a series of questions helping clients reflect on their typical cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses to problems.

- Social Problem Solving: Step by Step This worksheet presents a streamlined template to help clients define a problem, generate possible courses of action, and evaluate the effectiveness of an implemented solution.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others enhance their wellbeing, check out this signature collection of 17 validated positive psychology tools for practitioners. Use them to help others flourish and thrive.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

While we are born problem-solvers, facing an incredibly diverse set of challenges daily, we sometimes need support.

Problem-Solving Therapy aims to reduce stress and associated mental health disorders and improve wellbeing by improving our ability to cope. PST is valuable in diverse clinical settings, ranging from depression to schizophrenia, with research suggesting it as a highly effective treatment for teaching coping strategies and reducing emotional distress.

Many PST techniques are available to help improve clients’ positive outlook on obstacles while reducing avoidance of problem situations and the tendency to be careless and impulsive.

The PST model typically assesses the client’s strengths, weaknesses, and coping strategies when facing problems before encouraging a healthy experience of and relationship with problem-solving.

Why not use this article to explore the theory behind PST and try out some of our powerful tools and interventions with your clients to help them with their decision-making, coping, and problem-solving?

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Cuijpers, P., Wit, L., Kleiboer, A., Karyotaki, E., & Ebert, D. (2020). Problem-solving therapy for adult depression: An updated meta-analysis. European P sychiatry , 48 (1), 27–37.

- Dobson, K. S. (2011). Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Dobson, K. S., & Dozois, D. J. A. (2021). Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies (4th ed.). Guilford Press.

- Eysenck, M. W., & Keane, M. T. (2015). Cognitive psychology: A student’s handbook . Psychology Press.

- Nezu, A. M., & Nezu, C. M. (2009). Problem-solving therapy DVD . Retrieved September 13, 2021, from https://www.apa.org/pubs/videos/4310852

- Nezu, A. M., & Nezu, C. M. (2018). Emotion-centered problem-solving therapy: Treatment guidelines. Springer.

- Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & D’Zurilla, T. J. (2013). Problem-solving therapy: A treatment manual . Springer.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Thanks for your information given, it was helpful for me something new I learned

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

The Empty Chair Technique: How It Can Help Your Clients

Resolving ‘unfinished business’ is often an essential part of counseling. If left unresolved, it can contribute to depression, anxiety, and mental ill-health while damaging existing [...]

29 Best Group Therapy Activities for Supporting Adults

As humans, we are social creatures with personal histories based on the various groups that make up our lives. Childhood begins with a family of [...]

47 Free Therapy Resources to Help Kick-Start Your New Practice

Setting up a private practice in psychotherapy brings several challenges, including a considerable investment of time and money. You can reduce risks early on by [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (52)

- Coaching & Application (40)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (41)

- Emotional Intelligence (22)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (18)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (16)

- Mindfulness (40)

- Motivation & Goals (41)

- Optimism & Mindset (29)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (36)

- Positive Emotions (33)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Parenting (14)

- Positive Psychology (21)

- Positive Workplace (35)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (39)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (43)

- Therapy Exercises (38)

- Types of Therapy (55)

Save 60% for a limited time only →

[New!] Wellbeing X©. The low-effort, high-impact wellbeing program.

Emotions in Problem Solving

- First Online: 01 January 2015

Cite this chapter

- Markku S. Hannula 2

4262 Accesses

26 Citations

1 Altmetric

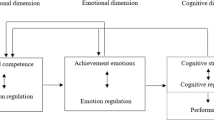

Emotions are important part of non-routine problem solving. A positive disposition to mathematics has a reciprocal relationship with achievement, both enhancing the other over time. In the process of solitary problem solving, emotions have a significant role in self-regulation, focusing attention and biasing cognitive processes. In social context, additional functions of emotions become apparent, such as interpersonal relations and social coordination of collaborative action. An illustrative case study presents the role of emotions in the problem solving process of one 10-year old Finnish student when he is solving an open problem of geometrical solids. The importance of emotions should be acknowledged also in teaching. Tasks should provide optimal challenge and feeling of control. The teacher can model the appropriate enthusiasm and emotion regulation. Joking and talking with a peer are important coping strategies for students.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Role of Social Emotions and Co-regulation of Learning During Complex Math Problem Solving

From perceived competence to emotion regulation: assessment of the effectiveness of an intervention among upper elementary students

Intertwinement of Rationality and Emotions in Mathematics Teaching: A Case Study

All names are pseudonyms

Curly brackets {} indicate observations and interpretations based on the video.

Square brackets [] indicate overlapping talk.

Ashcraft, M. H., & Krause, J. A. (2007). Working memory, math performance, and math anxiety. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 14 , 243–248.

Article Google Scholar

Bandura, A., & Schunk, D. H. (1981). Cultivating competence, self-efficacy and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41 (3), 586–598.

Buck, R. (1999). The biological affects: A typology. Psychological Review, 106 (2), 301–336.

Carlson, M., & Bloom, I. (2005). The cyclic nature of problem solving: an emergent multidimensional problem-solving framework. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 58 (1), 45–75.

Cobb, P., Yackel, E., & Wood, T. (1989). Young children’s emotional acts during mathematical problem solving. In D. B. McLeod & V. M. Adams (Eds.), Affect and mathematical problem solving: a new perspective (pp. 117–148). New York: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, I. (Eds.). (1992). Optimal experience: Psychological studies of flow in consciousness . Cambridge: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

Google Scholar

Damasio, A. R. (1999). The feeling of what happens . New York: Harcourt Brace and Company.

DeBellis, V. A., & Goldin, G. A. (2006). Affect and meta-affect in mathematical problem solving: A representational perspective. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 63 (2), 131–147.

De Corte, E., Depaepe, F., Op ’t Eynde, P. & Verschaffel. L. (2011). Students’ self-regulation of emotions in mathematics: an analysis of meta-emotional knowledge and skills. ZDM—The international Journal on Mathematics Education , 43 (4), 483–496.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82 (1), 405–432.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1971). Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. Journal of personality and social sychology , 17 (2), 124.

Ekman, P. (1972). Universals and cultural differences in facial expression of emotion. In J. K. Cole (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (pp. 207–283). Lincoln, USA: University of Nebraska Press.

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6 , 169–200.

Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., & Hager, J. C. (2002). Facial action coding system . Salt Lake City: A Human Face.

Else-Quest, N. M., Hyde, J. S., & Hejmadi, A. (2008). Mother and child emotions during mathematics homework. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 10 , 5–35.

Evans, J., Morgan, C., & Tsatsaroni, A. (2006). Discursive positioning and emotion in school mathematics practices. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 63 (2), 209–226.

Forgas, J. P. (2008). Affect and cognition. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3 (2), 94–101.

Freeman, K. E. (2004). The significance of motivational culture in schools serving african american adolescents: A goal theory approach. In P. R. Pintrich & M. L. Maehr (Eds.), Advannces in motivation and achievement (Vol. 13, pp. 65–95)., Motivating students, improving schools: The legacy of Carol Midgley The Netherlands: Elsevier Jai.

Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Lüdtke, O., Pekrun, R., & Sutton, R. E. (2009). Emotional Transmission in the Classroom: exploring the relationships between teacher and student enjoyment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101 (3), 705–716.

Fried, L. (2012). Teaching teachers about emotion regulation in the classroom. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36 (3), 117–127.

Friedel, J. M., Cortina, K. S., Turner, J. C., & Midgley, C. (2007). Achievement goals, efficacy beliefs and coping strategies in mathematics: The roles of perceived parent and teacher goal emphases. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32 , 434–458.

Goldin, G. A. (1988). Affective representation and mathematical problem solving. In M. J. Behr, C. B. Lacampagne, & M. M. Wheeler (Eds.), Proceedings of the 10th annual meeting of PME-NA (pp. 1–7). DeKalb: Northern Illinois University, Department of Mathematics.

Goldin, G. A. (2000). Affective pathways and representation in mathematical problem solving. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 2 (3), 209–219.

Goldin, G. A., Epstein, Y. M., Schorr, R. Y. & Warner, L. B. (2011) . Beliefs and engagement structures: behind the affective dimension of the mathematical learning. ZDM—The international Journal on Mathematics Education , 43 (4), 547–560.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2 , 271–299.

Hannula, M. S. (2003). Fictionalising experiences–—experiencing through fiction. For the Learning on Mathematics , 23 (3), 33–39.

Hannula, M. S. (2004). Affect in mathematical thinking and learning. Acta universitatis Turkuensis B 273. Finland: University of Turku.

Hannula, M. S. (2005). Shared cognitive intimacy and self-defence: Two socio-emotional processes in problem solving. Nordic studies on Mathematics Education, 1 , 25–41.

Hannula, M. S. (2006). Motivation in Mathematics: Goals reflected in emotions. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 63 (2), 165–178.

Hembree, R. (1990). The nature, effects, and relief of mathematics anxiety. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 21 , 33–46.

Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Faeth, M. (2010). The role of emotion and skilled intuition in learning. In D. Sousa (Ed.), Mind, brain, and education: Neuroscience implications for the classroom (pp. 67–81). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Kim, C. M., & Hodges, C. B. (2012). Effects of an emotion control treatment on academic emotions, motivation and achievement in an online mathematics course. Instructional Science, 40 , 173–192.

Lang, P. J. (1995). The emotion probe: Studies of motivation and attention. American Psychologist, 50 (5), 372–385.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation . Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lee, J. (2009). Universals and specifics of math self-concept, math self-efficacy, and math anxiety across 41 PISA 2003 participating countries. Learning and Individual Differences, 19 , 355–365.

Lehman, B., D’Mello, S., & Person, N. (2008). All alone with your emotions: An analysis of student emotions during effortful problem solving activities . Paper presented at the workshop on emotional and cognitive issues in ITS at the ninth international conference on intelligent tutoring systems. Accessed April 15, 2012 at http://141.225.218.248/web-cslwebroot/emotion/files/lehman-affectwkshp-its08.pdf .

Levenson, R. W., & Gottman, J. M. (1983). Marital interaction: Physiological linkage and affective exchange. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 45 , 587–597.

Linnenbrink, E. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (2004). Role of affect in cognitive processing in academic contexts. In D. Y. Dai & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Motivation, emotion, and cognition; Integrative perspectives on intellectual functioning and development (pp. 57–88). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ludmer, R., Dudai, Y., & Rubin, N. (2011). Uncovering camouflage: Amygdala activation predicts long-term memory of induced perceptual insight. Neuron, 69 (5), 1002–1014.

Ma, X. (1999). A meta-analysis of the relationship between anxiety toward mathematics and achievement in mathematics. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 30 , 520–541.

Ma, X., & Kishor, N. (1997a). Assessing the relationship between attitude toward mathematics and achievement in mathematics: A meta-analyses. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 28 (1), 26–47.

Ma, X., & Kishor, N. (1997b). Attitude toward self, social factors, and achievement in mathematics: A meta-analytic review. Educational Psychology Review, 9 , 89–120.

Ma, X., & Xu, J. (2004). Determining the Causal Ordering between Attitude toward Mathematics and Achievement in Mathematics. American Journal of Education, 110 (May), 256–280.

Malmivuori, M. L. (2006). Affect and self-regulation. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 63 (2), 149–164.

Mason, J., Burton, L., & Stacey, K. (1982). Thinking mathematically . New York: Addison Wesley.

McLeod, D. B. (1988). Affective issues in mathematical problem solving: Some theoretical considerations. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 19 , 134–141.

McLeod, D. B. (1992). Research on affect in mathematics education: A reconceptualization. In D. A.Grouws, (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Mathematics Learning and Teaching (pp. 575–596). New York: MacMillan.

Middleton, J. A., & Spanias, P. A. (1999). Motivation for achievement in mathematics: Findings, generalizations, and criticisms of the research. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 30 , 65–88.

Midgley, C., Kaplan, A., Middleton, M., Maehr, M. L., Urdan, T., Anderman, L. H., et al. (1998). The development and validation of scales assessing students’ achievement goal orientations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 23 , 113–131.

Minato, S., & Kamada, T. (1996). Results on research studies on Causal predominance between achievement and attitude in junior high school mathematics of Japan. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 27 , 96–99.

Murphy, P. K., & Alexander, P. A. (2000). A motivated exploration of motivation terminology. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 , 3–53.

Näveri, L., Pehkonen, E., Hannula, M.S., Laine, A. & Heinilä, L. (2011). Finnish elementary teachers’ espoused beliefs on mathematical problem solving. In: B. Rösken & M. Casper (Eds.), Current State of Research on Mathematical Beliefs XVII. Proceedings of the MAVI-17 Conference (pp. 161–171). University of Bochum: Germany.

Nett, U. E., Goetz, T., & Hall, N. C. (2011). Coping with boredom in school: An experience sampling perspective. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36 , 49–59.

Niemivirta, M. (2004). Habits of Mind and Academic Endeavors. The Correlates and Consequences of Achievement Goal Orientation. Department of Education, Research Report 196. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. Doctoral thesis.

Nohda, N. (2000). Teaching by open approach methods in Japanese mathematics classroom. In. T. Nakahara and M. Koyama (Eds.), Proceedings of 24th conference of the international group for the psychology of mathematics education (Vol. 1, pp. 39–53). Hiroshima, Japan: PME.

OECD. (2003). The PISA 2003 assessment framework—mathematics, reading, science and problem solving knowledge and skills . Paris: OECD.

Op ’t Eynde, P. & Hannula, M. S. (2006). The case study of Frank. Educational Studies in Mathematics 63 , 123–129.

Pekrun, R., & Stephens, E. J. (2010). Achievement emotions: A control value approach. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4 (4), 238–255.

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Daniels, L. M., Stupnisky, R. H., & Perry, R. P. (2010). Boredom in achievement settings: Exploring control-value antecedents and performance outcomes of a neglected emotion. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102 (3), 531–549.

Pintrich, P. R. (1994). Continuities and discontinuities: Future directions for research in educational psychology. Educational Psychologist, 29 , 137–148.

Polya, G. (1957). How to solve it: A new aspect of mathematical method . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Power, M., & Dalgleish, T. (1997). Cognition and emotion; from order to disorder . UK: Psychology Press.

Rubinsten, O., & Tannock, R. (2010). Mathematics anxiety in children with developmental dyscalculia. Behavioral and Brain Functions , 6 (46). http://www.behavioralandbrainfunctions.com/content/6/1/46 .

Schlöglmann, W. (2003). Can neuroscience help us better understand affective reactions in mathematics learning? In M. A. Mariotti (Ed.), Proceedings of Third Conference of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education, 28 February—3 March 20. Bellaria, Italia. Accessed April 10, 2012 at < http://ermeweb.free.fr/CERME3/Groups/TG2/TG2_schloeglmann_cerme3.pdf >.

Schoenfeld, A. H. (1985). Mathematical problem solving . San Diego: Academic Press.

Schoenfeld, A. H. (1992). Learning to think mathematically: Problem solving, metacognition, and sense-making in mathematics. In D. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook for research on mathematics teaching and learning (pp. 334–370). New York: MacMillan.

Schukajlow, S., Leiss, D., Pekrun, R., Blum, W., Müller, M., & Messner, R. (2011). Teaching methods for modelling problems and students’ task-specific enjoyment, value, interest and self-efficacy expectations. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 79 (2), 215–237.

Shmakov, P. & Hannula, M. S. (2010). Humour as means to make mathematics enjoyable. In V. Durand-Guerrier, S. Soury-Lavergne & F. Arzarello (Eds.), Proceedings of CERME 6, January 28th-February 1st 2009 (pp. 144–153). Lyon France: INRP 2010 <downloaded 15.6.2010: www.inrp.fr/editions/cerme6 >.

Vogel-Walcutt, J. J., Fiorella, L., Carper, T., & Schatz, S. (2012). The definition, assessment, and mitigation of state boredom within educational settings: A comprehensive review. Educational Psychology Review, 24 , 89–111.

Williams, G. (2002). Associations between mathematically insightful collaborative behaviour and positive affect. In A. D. Cockburn & E. Nardi (Eds.), Proceedings of 26th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education (Vol. 4, pp. 402–409). Norwich, UK: PME.

Williams, T., & Williams, K. (2010). Self-efficacy and performance in mathematics: Reciprocal determinism in 33 nations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102 (2), 453–466.

Download references

Acknowledgments

This research has been funded by Academy of Finland (project #135556).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.