- Human Editing

- Free AI Essay Writer

- AI Outline Generator

- AI Paragraph Generator

- Paragraph Expander

- Essay Expander

- Literature Review Generator

- Research Paper Generator

- Thesis Generator

- Paraphrasing tool

- AI Rewording Tool

- AI Sentence Rewriter

- AI Rephraser

- AI Paragraph Rewriter

- Summarizing Tool

- AI Content Shortener

- Plagiarism Checker

- AI Detector

- AI Essay Checker

- Citation Generator

- Reference Finder

- Book Citation Generator

- Legal Citation Generator

- Journal Citation Generator

- Reference Citation Generator

- Scientific Citation Generator

- Source Citation Generator

- Website Citation Generator

- URL Citation Generator

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- AI Writing Guides

- AI Detection Guides

- Citation Guides

- Grammar Guides

- Paraphrasing Guides

- Plagiarism Guides

- Summary Writing Guides

- STEM Guides

- Humanities Guides

- Language Learning Guides

- Coding Guides

- Top Lists and Recommendations

- AI Detectors

- AI Writing Services

- Coding Homework Help

- Citation Generators

- Editing Websites

- Essay Writing Websites

- Language Learning Websites

- Math Solvers

- Paraphrasers

- Plagiarism Checkers

- Reference Finders

- Spell Checkers

- Summarizers

- Tutoring Websites

Most Popular

11 days ago

Why Congress Cares About Media Literacy and You Should Too

How educators can reinvent teaching and learning with ai, plagiarism vs copyright.

12 days ago

Who vs Whom

Top 20 best books on american history, what does essay mean in spanish.

In the world of language learning, understanding the meaning of words across different languages is a fascinating endeavor. One such word that often captures the attention of language enthusiasts is “essay.” In this guide, we will explore what the word “essay” means in Spanish, its cultural significance, and provide valuable insights for those interested in writing essays in Spanish.

Unveiling the Translation: The Meaning of “Essay” in Spanish

When we try to find the Spanish translation for the English word “essay,” we come across the term “ensayo.” The word “ensayo” carries the essence of an essay, representing a written composition that presents a coherent argument or explores a specific topic. It is a versatile term used in various contexts, such as academic, literary, and even journalistic writing. If you’re interested in diving deeper into Spanish or other languages, online language tutoring services can be a valuable resource. They provide personalized guidance to help you understand the usage in different contexts.

Exploring Cultural Nuances: The Cultural Impact of “Essay” in Spanish

Language is deeply intertwined with culture, and understanding the cultural implications of a word is crucial for effective communication. In the context of Spanish, the word “ensayo” holds significance beyond its literal meaning. It reflects the rich literary traditions and academic rigor associated with the Spanish language.

In Spanish literature, essays play a vital role in expressing thoughts, analyzing complex ideas, and offering critical perspectives. Renowned Spanish and Latin American writers have contributed significantly to the genre, showcasing the power of essays as a means of cultural expression.

Writing Essays in Spanish: Tips and Techniques

If you are interested in writing essays in Spanish, here are some valuable tips and techniques to enhance your skills.

Understand the Structure

Just like in English, Spanish essays follow a specific structure. Start with an introduction that sets the context and thesis statement, followed by body paragraphs that present arguments or discuss different aspects of the topic. Finally, conclude with a concise summary that reinforces your main points.

Embrace Language Nuances

Spanish is known for its richness and expressive nature. Incorporate idiomatic expressions, figurative language, and varied vocabulary to add depth and flair to your essays. This will not only showcase your language proficiency but also engage your readers.

Research and Refer to Established Writers

To improve your Spanish essay writing skills, immerse yourself in the works of established Spanish and Latin American writers. Reading essays by renowned authors such as Octavio Paz, Jorge Luis Borges, or Gabriel García Márquez can provide valuable insights into the art of essay writing in Spanish.

In conclusion, the Spanish translation of the English word “essay” is “ensayo.” However, it is essential to understand that “ensayo” encompasses a broader cultural and literary significance in the Spanish language. It represents a means of expressing thoughts, analyzing ideas, and contributing to the rich tapestry of Spanish literature.

For those venturing into the realm of writing essays in Spanish, embracing the structural conventions, incorporating language nuances, and seeking inspiration from established writers will pave the way for success. So, embark on your Spanish essay writing journey with confidence and let your words resonate within the vibrant world of Spanish language and culture.

Remember, whether you are exploring literary essays, academic papers, or personal reflections, the beauty of essays lies in their ability to capture the essence of thoughts and ideas, transcending linguistic boundaries.

Are there any synonyms for the word ‘essay’ in the Spanish language?

In Spanish, there are a few synonyms that can be used interchangeably with the word “ensayo,” which is the most common translation for “essay.” Some synonyms for “ensayo” include “redacción” (composition), “prosa” (prose), and “artículo” (article). These synonyms may have slight variations in their usage and connotations, but they generally convey the idea of a written composition or discourse.

What are the common contexts where the word ‘essay’ is used in Spanish?

The word “ensayo” finds its usage in various contexts in the Spanish language. Here are some common contexts where the word “ensayo” is commonly used:

- Academic Writing: In the academic sphere, “ensayo” refers to an essay or a written composition assigned as part of coursework or academic assessments. It involves presenting arguments, analyzing topics, and expressing ideas in a structured manner.

- Literary Essays: Spanish literature has a rich tradition of literary essays. Renowned writers use “ensayo” to explore and analyze various literary works, authors, or literary theories. These essays delve into critical interpretations and provide insights into the literary landscape.

- Journalistic Writing: Journalists often employ “ensayo” to write opinion pieces or in-depth analyses on current events, social issues, or cultural phenomena. These essays offer a subjective perspective, providing readers with thoughtful reflections and commentary.

- Personal Reflections: Individuals may also write personal essays or reflections on topics of interest or experiences. These essays allow individuals to share their thoughts, feelings, and insights, offering a glimpse into their personal perspectives.

Are there any cultural implications associated with the Spanish word for ‘essay’?

Yes, there are cultural implications associated with the Spanish word for “essay,” which is “ensayo.” In Spanish-speaking cultures, essays are highly regarded as a form of intellectual expression and critical thinking. They serve as a platform for writers to convey their ideas, opinions, and reflections on a wide range of subjects.

The cultural implications of “ensayo” extend to the realm of literature, where renowned Spanish and Latin American authors have made significant contributions through their essays. These essays often explore cultural identities, social issues, historical events, and philosophical concepts, reflecting the cultural richness and intellectual depth of Spanish-speaking communities.

Moreover, the tradition of essay writing in Spanish fosters a deep appreciation for language, literature, and the exploration of ideas. It encourages individuals to engage in thoughtful analysis, promotes intellectual discourse, and contributes to the cultural and intellectual heritage of Spanish-speaking societies.

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

More from Spanish Guides

Te quiero vs. Te amo

Nov 25 2023

Learning about Parts of the Body in Spanish

Nov 24 2023

What Does Compa Mean?

Remember Me

What is your profession ? Student Teacher Writer Other

Forgotten Password?

Username or Email

Translations dictionary

or esse [ es -ey] or [ ey -sey]

What does ese mean?

Ese , amigo , hombre . Or, in English slang, dude , bro , homey . Ese is a Mexican-Spanish slang term of address for a fellow man.

Related words

Where does ese come from.

Ese originates in Mexican Spanish. Ese literally means “that” or “that one,” and likely extended to “fellow man” as shortened from expressions like ese vato , “that guy.”

There are some more elaborate (though less probable) theories behind ese . One goes that a notorious Mexican gang, the Sureños (“Southerners”), made their way from Mexico City to Southern California in the 1960s. Ese is the Spanish name for letter S , which is how the gang members referred to each other. Or so the story goes.

Ese is recorded in English for a “fellow Hispanic man” in the 1960s. It became more a general term of address by the 1980s, though ese remains closely associated (and even stereotyped) with Chicano culture in the US.

Ese is notably found in the Chicano poetry of José Antonio Burciaga and Cheech & Chong comedy routines (Cheech Marin is Mexican-American.)

White confusion over ese was memorably parodied in a 2007 episode of the TV show South Park . On it, the boys think they can get some Mexican men to write their essays , but them men write letters home to their eses .

Examples of ese

Who uses ese?

For Mexican and Mexican-American Spanish speakers, ese has the force of “dude,” “brother,” or “man,” i.e., a close and trusted friend or compatriot .

I needa kick it wit my ese's its been a minute — al (@a1anxs) February 1, 2019

It’s often used as friendly and familiar term of address…

Always a good time with my ese. 😎 pic.twitter.com/xxM4YroWDV — | Y | G | (@yg_monroe) January 12, 2019

…but it can also be more aggressively and forcefully.

Cypress Hill 2018: Who you tryin' ta mess with, ese? Don't you know I'm seeking professional help for my deep rooted emotional problemsssssss?!? — JAY. (@GoonLeDouche) June 30, 2018

“You’d have to be crazy to swipe left.” Who you tryna get crazy with, ese? Don’t you know I’m loco? Sorry, always wanted to say that. Anyway, swipe left. Might actually be crazy. — Why I Swiped Left (@LeftyMcSwiper) December 17, 2018

Ese is associated with Mexican and Chicano American culture, where it can refer to and be used by both men and women. The term is also specifically associated with Mexican-American gang culture.

What's up ese? pic.twitter.com/0vAQxZZ6SO — AlesiAkiraKitsune© (@AlesiAkira) January 21, 2019

It is often considered appropriative for people outside those cultures to use ese , especially since some non-Mexican people may use ese in ways that mock Mexicans and Mexican-American culture.

This is not meant to be a formal definition of ese like most terms we define on Dictionary.com, but is rather an informal word summary that hopefully touches upon the key aspects of the meaning and usage of ese that will help our users expand their word mastery.

- By clicking "Sign Up", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy policies.

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other categories

- Famous People

- Fictional Characters

- Gender & Sexuality

- Historical & Current Events

- Pop Culture

- Tech & Science

- Translations

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Translation of essay – English-Spanish dictionary

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- I want to finish off this essay before I go to bed .

- His essay was full of spelling errors .

- Have you given that essay in yet ?

- Have you handed in your history essay yet ?

- I'd like to discuss the first point in your essay.

(Translation of essay from the Cambridge English-Spanish Dictionary © Cambridge University Press)

Translation of essay | GLOBAL English–Spanish Dictionary

(Translation of essay from the GLOBAL English-Spanish Dictionary © 2020 K Dictionaries Ltd)

Examples of essay

Translations of essay.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

pitch-perfect

singing each musical note perfectly, at exactly the right pitch (= level)

Alike and analogous (Talking about similarities, Part 1)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English–Spanish Noun Verb

- GLOBAL English–Spanish Noun

- Translations

- All translations

Add essay to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

How to Say “Essay” in Spanish: A Comprehensive Guide

Are you looking to expand your Spanish vocabulary and express yourself more fluently? Learning how to say “essay” in Spanish is a vital step in becoming a proficient Spanish speaker and writer. In this guide, we will explore both formal and informal ways to express this term, while also providing you with useful tips, examples, and regional variations. Let’s dive in!

Formal Ways to Say “Essay” in Spanish

When it comes to a formal context, such as educational or professional settings, you can use the following terms:

The most common and widely accepted translation for “essay” in Spanish is “ensayo.” This term applies to both academic essays and literary compositions and is commonly used across Spanish-speaking regions. For example:

El profesor nos pidió que escribiéramos un ensayo sobre la importancia de la educación. (The professor asked us to write an essay about the importance of education.)

Another formal term that can be used interchangeably with “ensayo” is “trabajo.” This translation is more commonly used in academic contexts, particularly when referring to written assignments. For instance:

El estudiante está trabajando en su último trabajo de historia. (The student is working on his/her final essay for history.)

Informal Ways to Say “Essay” in Spanish

When speaking with friends or in more casual contexts, you may prefer to use the following alternatives:

1. Redacción

“Redacción” is a common term used to refer to essays in a more informal setting. It is often used when discussing written compositions without the strict academic connotations. Here’s an example:

Ayer tuve que hacer una redacción sobre mis vacaciones de verano. (Yesterday, I had to write an essay about my summer vacation.)

2. Ensayito

For a diminutive and more affectionate term, you can use “ensayito.” This variation is akin to saying “little essay” in English, adding a touch of informality and endearment to your speech. Here’s an example:

Juanita siempre escribe unos ensayitos muy interesantes. (Juanita always writes very interesting little essays.)

Regional Variations

While the terms mentioned above are widely understood across Spanish-speaking regions, it’s worth noting that variations may exist. Here are a few examples of regional alternatives:

1. Composición (Latin America)

In Latin America, especially in countries like Mexico and Colombia, “composición” is commonly used instead of “ensayo” or “trabajo” when referring to essays. For example:

Hoy tengo que entregar una composición sobre la historia del arte. (Today, I have to submit an essay about art history.)

2. Tarea (Spain)

In Spain, “tarea” is frequently used to refer to written assignments, including essays. Keep in mind that “tarea” has a broader meaning and can also encompass other types of homework or tasks. Here’s an example:

La profesora nos asignó una tarea sobre el cambio climático. (The teacher assigned us an essay on climate change.)

Tips for Writing an Essay in Spanish

Whether you are a Spanish learner or a native speaker looking to improve your writing skills, these tips will help you craft a compelling essay:

1. Use a Variety of Vocabulary

Avoid repetitive language by incorporating different synonyms, idiomatic expressions, and specialized terms relevant to the topic. This will showcase your command of the language and make your essay more engaging to read.

2. Structure Your Essay Properly

An essay should have a clear introduction, body paragraphs with supporting evidence or arguments, and a conclusion. Make sure to organize your thoughts and ideas coherently to ensure a logical flow throughout your essay.

3. Proofread and Edit

Take the time to proofread your essay for grammar, spelling, and punctuation mistakes. Consider asking a native Spanish speaker or a trusted language professional to review your work and provide feedback.

4. Read Essays by Native Spanish Writers

Reading essays written by native Spanish speakers can expose you to a range of writing styles, vocabulary, and grammatical structures. This exposure will help you develop a better understanding of what makes a well-written essay in Spanish.

Congratulations! You now have a comprehensive understanding of how to say “essay” in Spanish. Remember to consider the context and formality of the situation to choose the most appropriate term. Use the formal terms “ensayo” or “trabajo” when in professional or academic environments, and opt for “redacción” or “ensayito” in informal conversations with friends. Don’t forget to keep practicing your writing skills and explore different vocabulary to create compelling essays. ¡Buena suerte!

Related Posts

How to Say a Little Spanish in Spanish: A Comprehensive Guide

Are you interested in learning how to express the idea of "a little Spanish" in the Spanish language? Whether you're a beginner or an intermediate learner, this guide will provide you with various ways to convey this concept in both formal and informal settings. Throughout this article, we'll explore tips, examples, and even some regional variations, if necessary. So, let's dive in and enhance your Spanish language skills!

How to Say "A Spanish Book" in Spanish: A Comprehensive Guide

Bienvenidos! If you're looking to learn different ways to say "a Spanish book" in Spanish, you've come to the right place. Whether you want to express it formally or informally, this guide will provide you with various options to choose from. We'll also touch upon regional variations, but only when necessary. Let's dive in!

How to Say a Spanish Restaurant in Spanish

Welcome to our guide on how to say a Spanish restaurant in Spanish! Whether you are traveling to a Spanish-speaking country or simply want to expand your language skills, knowing how to describe a Spanish restaurant will certainly come in handy. In this guide, we will cover both formal and informal ways to refer to a Spanish restaurant, as well as provide tips, examples, and regional variations. So, let's dive in!

How to Say "Does Anyone Speak Spanish?" in Spanish: Formal and Informal Ways

Learning how to ask if someone speaks Spanish in Spanish is a useful phrase to have in your arsenal when traveling to a Spanish-speaking country or simply trying to communicate with Spanish speakers. In this guide, we will explore both formal and informal ways to ask, as well as provide you with some helpful tips and examples.

How to Say "Are You Spanish" in Spanish

Greetings! If you're interested in learning how to ask someone if they are Spanish in the Spanish language, you've come to the right place. In this comprehensive guide, we will cover both the formal and informal ways of asking this question. While regional variations exist, we will focus on the more universally understood phrases. Let's dive in!

How to Say "Are You Spanish?" in Spanish

Greetings! If you're interested in learning how to ask someone if they are Spanish in Spanish, you've come to the right place. In this guide, we'll explore both the formal and informal ways to ask this question, along with some regional variations. Whether you're planning a trip to a Spanish-speaking country or simply expanding your language skills, these phrases will come in handy. So, without further ado, let's delve into the fascinating world of the Spanish language!

How to Say Broken Spanish in Spanish: A Comprehensive Guide

Are you looking to learn how to say "broken Spanish" in Spanish? Whether you want to express your limitations in Spanish or simply describe language skills in a more nuanced way, this guide will provide you with various formal and informal phrases to convey the idea of "broken Spanish." We'll also discuss regional variations when necessary to help you develop a comprehensive understanding. Let's get started!

How to Say "Can You Speak Spanish?" in Spanish

If you're planning to visit a Spanish-speaking country or want to engage in a conversation with a Spanish speaker, it can be useful to know how to ask if someone can speak Spanish. In this guide, we'll explore the different ways to say "Can you speak Spanish?" in Spanish, both formally and informally. We'll also include some regional variations, if necessary. Let's dive in!

Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Arabic Cantonese Chinese Dutch English Farsi Filipino French German Greek Hawaiian Hebrew Hindi Irish Italian Japan Japanese Korean Latin Mandarin Mexican Navajo Norwegian Polish Portuguese Punjabi Romanian Russian Sanskrit Sign Language Spanish Swahili Swedish Tagalog Tamil Thai Turkish Ukrainian Urdu Vietnamese

- Privacy Policy

- 1.1.1 Pronunciation

- 1.3 References

- 1.4 Anagrams

- 2.1 Pronunciation

- 2.2.1 Declension

- 2.2.2 See also

- 3.1 Etymology

- 3.2 Pronoun

- 3.3 Adjective

- 3.4 Related terms

- 4.1 Etymology

- 4.2.1 Declension

- 4.2.2 See also

- 5.1 Etymology

- 5.2 Pronunciation

- 5.3 Determiner

- 5.4 Further reading

- 6.2 References

- 7.1 Participle

- 8.1.1 Alternative forms

- 8.1.2.1 Synonyms

- 8.1.2.2 Descendants

- 8.1.3 References

- 8.2.1 Adjective

- 9.1 Pronunciation

- 10.1 Alternative forms

- 10.2 Etymology

- 10.3.1 Derived terms

- 10.3.2 Related terms

- 10.4 References

- 11.1 Pronunciation

- 13.1 Pronunciation

- 13.2.1 Noun

- 13.3.1 Determiner

- 13.3.2 Interjection

- 13.3.3.1 Usage notes

- 13.3.3.2 Derived terms

- 13.3.4 See also

- 13.4 Further reading

- 14.1 Etymology

- 14.2 Pronunciation

- 14.4 Further reading

- 15.1.1 Pronunciation

- 15.1.2 Noun

- 15.2.1 Pronunciation

- 15.2.2 Noun

- 15.3.1 Pronunciation

- 15.3.2.1 Derived terms

- 15.4.1 Pronunciation

- 15.4.2 Noun

- 15.5.1 Pronunciation

- 15.5.2 Noun

- 15.6.1 Pronunciation

- 15.6.2 Noun

English [ edit ]

Etymology 1 [ edit ].

From Mexican Spanish ése ( “ dude ” ) .

Pronunciation [ edit ]

- ( General American ) IPA ( key ) : /ˈɛˌseɪ/

- Rhymes: -ɛseɪ

- Homophone : essay

Noun [ edit ]

ese ( plural eses )

- ( US ) dude , man . ( Usually used vocatively ).

Etymology 2 [ edit ]

- Obsolete spelling of ease

References [ edit ]

- “ ese ”, in Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary , Springfield, Mass.: G. & C. Merriam , 1913, →OCLC .

Anagrams [ edit ]

- SEE , See , ees , see

Basque [ edit ]

- IPA ( key ) : /es̺e/ , [e̞.s̺e̞]

ese inan

- The name of the Latin-script letter S .

Declension [ edit ]

See also [ edit ].

- ( Latin-script letter names ) a , be , ze , de , e , efe , ge , hatxe , i , jota , ka , ele , eme , ene , eñe , o , pe , ku , erre , ese , te , u , uve , uve bikoitz , ixa , i greko , zeta

Chuukese [ edit ]

Etymology [ edit ].

e- + -se

Pronoun [ edit ]

- he , she , it does not

Adjective [ edit ]

- he, she, it is not

- he, she, it was not

Related terms [ edit ]

Estonian [ edit ].

Allegedly coined ex nihilo by Johannes Aavik in the 20th century, but compare Finnish esine .

ese ( genitive eseme , partitive eset )

- object , thing , item

Galician [ edit ]

From Old Galician-Portuguese [Term?] , from Latin [Term?] .

- IPA ( key ) : /ˈesɪ/

Determiner [ edit ]

ese m ( feminine singular esa , masculine plural eses , feminine plural esas , neuter iso )

Further reading [ edit ]

- “ ese ” in Dicionario da Real Academia Galega , Royal Galician Academy .

Karitiâna [ edit ]

- Number and the mass/count distinction in Karitiana

Latin [ edit ]

Participle [ edit ].

- vocative masculine singular of ēsus

Middle English [ edit ]

Borrowed from Old French aise , eise .

Alternative forms [ edit ]

- eyse , eise , ase , ayse , aise , yese

- Physical comfort , or that which is conducive thereto.

- Material prosperity ; profit .

- Good health .

- 1370-90 , William Langland , Piers Plowman For if hevene be on this erthe, and ese to any soule, It is in cloistre or in scole. (please add an English translation of this quotation)

- Enjoyment , pleasure , delight .

- Ease , facility .

- c. 1225 , “Feorðe dale: fondunges”, in Ancrene Ƿiſſe (MS. Corpus Christi 402) [1] , Herefordshire , published c. 1235 , folio 78, verso; republished at Cambridge : Parker Library on the Web , 2018 January: [ … ] hƿen þe delit i þe luſt iſ igan ſe ouerforð · þet ter nere nan ƿiðſeggunge ȝef þer ƿere eiſe to fulle þe dede · [ … ] when the delight taken in the craving has gone so far that there will be no denying it if there's any way whatsoever to do it.

- The mitigation or alleviation of discomfort , burden or suffering .

- ( law ) The right to utilize the property of a neighbour for certain ends; easement .

Synonyms [ edit ]

- ( comfort ) : esynesse

- ( ease ) : facilite

Descendants [ edit ]

- “ ese, n. ”, in MED Online , Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan , 2007, retrieved 6 August 2018 .

- Alternative form of eise

Northern Paiute [ edit ]

- IPA ( key ) : /isi/ or IPA ( key ) : /iʃi/

- light brown - gray

Norwegian Nynorsk [ edit ]

- esa ( a-infinitive )

- ( non-standard since 2012 ) æsa , æse

From Germanic , ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European root *yes- ( “ to well, seethe, foam, ferment ” ) . Compare Icelandic æsa , from Proto-Germanic *jōsijaną .

Verb [ edit ]

ese ( present tense esar , past tense esa , past participle esa , passive infinitive esast , present participle esande , imperative ese / es )

- ( intransitive ) to swell , seethe , ferment

- ( intransitive , by extension ) to grow larger

- ( impersonal ) to devolve , be stirred , riled up Synonym: ulme

Derived terms [ edit ]

- ( with particle ) : ese opp ; ese ut

- jest , jester

- “ese” in The Nynorsk Dictionary .

Old English [ edit ]

- IPA ( key ) : /ˈeː.se/ , [ˈeː.ze]

- dative singular of ōs

Pohnpeian [ edit ]

- ( transitive ) to know

Spanish [ edit ]

- IPA ( key ) : /ˈese/ [ˈe.se]

- Rhymes: -ese

- Syllabification: e‧se

ese f ( plural eses )

Inherited from Latin ipse .

ese m sg ( plural esos , feminine esa , feminine plural esas )

- ( demonstrative ) that Synonym: ( poetic or archaic ) aquese

Interjection [ edit ]

- ( Mexico , informal ) hello

ese m ( feminine esa , neuter eso , masculine plural esos , feminine plural esas , neuter plural esos )

- ( demonstrative ) Alternative spelling of ése

Usage notes [ edit ]

- The unaccented form can function as a pronoun if it can be unambiguously deduced as such from context.

- esa es otra

- ni por esas

- Not used with con ; conmigo , contigo , and consigo are used instead, respectively

- Like other masculine Spanish words, masculine Spanish pronouns can be used when the gender of the subject is unknown or when the subject is plural and of mixed gender.

- Treated as if it were third-person for purposes of conjugation and reflexivity

- If le or les precedes lo , la , los , or las in a clause, it is replaced with se (e.g., Se lo dije instead of Le lo dije )

- Depending on the implicit gender of the object being referred to

- Used primarily in Spain

- Used only in rare circumstances

- “ ese ”, in Diccionario de la lengua española , Vigésima tercera edición , Real Academia Española, 2014

Tagalog [ edit ]

From Spanish ese , the Spanish name of the letter S / s .

- Hyphenation: e‧se

- IPA ( key ) : /ˈʔese/ , [ˈʔɛ.sɛ]

ese ( Baybayin spelling ᜁᜐᜒ )

- ( historical ) The name of the Latin-script letter S / s , in the Abecedario . Synonyms: ( in the Filipino alphabet ) es , ( in the Abakada alphabet ) sa

- “ ese ”, in Pambansang Diksiyonaryo | Diksiyonaryo.ph , Manila, 2018

Yoruba [ edit ]

- IPA ( key ) : /ē.sé/

- ( rare ) hippopotamus Synonym: erinmi

- IPA ( key ) : /è.sē/

- ( rare ) cat Synonyms: ológbò , ológìní , músù irọ́ ni, ẹ̀yìn èse kì í kanlẹ̀ ― It is impossible, a cat can never land on its back

Etymology 3 [ edit ]

From è- ( “ nominalizing prefix ” ) + sè ( “ To dye, to paint ” ) .

IPA ( key ) : /è.sè/

- dye ; ( in particular ) purple dye ó sè é ní èsè ― She dyed it purple

- elésè-àlùkò ( “ purple ” )

- èsè-àtúfà ( “ Pergularia daemia ” )

Etymology 4 [ edit ]

Etymology 5 [ edit ].

IPA ( key ) : /ē.sè/

- ( rare ) shea butter Synonym: òrí

Etymology 6 [ edit ]

- ( Ijebu ) yellow yam , dioscorea cayenensis Synonym: àgọ́ndọ̀n-ọ́n ( Ìjẹ̀bú )

- ( Ijebu , by extension ) yellow

- English terms borrowed from Mexican Spanish

- English terms derived from Mexican Spanish

- English 2-syllable words

- English terms with IPA pronunciation

- English terms with audio links

- Rhymes:English/ɛseɪ

- Rhymes:English/ɛseɪ/2 syllables

- English terms with homophones

- English lemmas

- English nouns

- English countable nouns

- English palindromes

- American English

- English obsolete forms

- English terms of address

- Basque terms with IPA pronunciation

- Basque lemmas

- Basque nouns

- Basque palindromes

- Basque inanimate nouns

- eu:Latin letter names

- Chuukese terms prefixed with e-

- Chuukese terms suffixed with -se

- Chuukese lemmas

- Chuukese pronouns

- Chuukese palindromes

- Chuukese adjectives

- Estonian terms coined by Johannes Aavik

- Estonian coinages

- Estonian lemmas

- Estonian nouns

- Estonian palindromes

- Estonian ase-type nominals

- Galician terms inherited from Old Galician-Portuguese

- Galician terms derived from Old Galician-Portuguese

- Galician terms inherited from Latin

- Galician terms derived from Latin

- Galician terms with IPA pronunciation

- Galician terms with audio links

- Galician lemmas

- Galician determiners

- Galician palindromes

- Karitiâna lemmas

- Karitiâna nouns

- Karitiâna palindromes

- Latin non-lemma forms

- Latin participle forms

- Latin palindromes

- Middle English terms borrowed from Old French

- Middle English terms derived from Old French

- Middle English lemmas

- Middle English nouns

- Middle English palindromes

- Middle English terms with quotations

- Middle English adjectives

- Northern Paiute terms with IPA pronunciation

- Northern Paiute lemmas

- Northern Paiute nouns

- Northern Paiute palindromes

- Norwegian Nynorsk terms derived from Proto-Indo-European

- Norwegian Nynorsk terms derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *yes-

- Norwegian Nynorsk terms derived from Germanic languages

- Norwegian Nynorsk lemmas

- Norwegian Nynorsk verbs

- Norwegian Nynorsk palindromes

- Norwegian Nynorsk weak verbs

- Norwegian Nynorsk intransitive verbs

- Norwegian Nynorsk impersonal verbs

- Old English terms with IPA pronunciation

- Old English non-lemma forms

- Old English noun forms

- Old English palindromes

- Pohnpeian lemmas

- Pohnpeian verbs

- Pohnpeian palindromes

- Pohnpeian transitive verbs

- Spanish 2-syllable words

- Spanish terms with IPA pronunciation

- Rhymes:Spanish/ese

- Rhymes:Spanish/ese/2 syllables

- Spanish lemmas

- Spanish nouns

- Spanish countable nouns

- Spanish palindromes

- Spanish feminine nouns

- es:Latin letter names

- Spanish terms inherited from Latin

- Spanish terms derived from Latin

- Spanish determiners

- Spanish interjections

- Mexican Spanish

- Spanish informal terms

- Spanish pronouns

- Tagalog terms borrowed from Spanish

- Tagalog terms derived from Spanish

- Tagalog 2-syllable words

- Tagalog terms with IPA pronunciation

- Tagalog lemmas

- Tagalog nouns

- Tagalog terms with Baybayin script

- Tagalog palindromes

- Tagalog terms with historical senses

- tl:Latin letter names

- Yoruba terms with IPA pronunciation

- Yoruba lemmas

- Yoruba nouns

- Yoruba palindromes

- Yoruba terms with rare senses

- Yoruba terms with usage examples

- Yoruba terms prefixed with e-

- Ijẹbu Yoruba

- English entries with language name categories using raw markup

- Old Galician-Portuguese term requests

- Latin term requests

- Requests for translations of Middle English quotations

- Northern Paiute entries with topic categories using raw markup

- Tagalog terms with missing Baybayin script entries

- Tagalog terms without tl-pr template

- Pages using lite templates

- Yoruba entries with topic categories using raw markup

- Entries using missing taxonomic name (species)

Navigation menu

Mexican Slang 101: Master Spanish Slang Used in Mexico

Mexican slang, often called "Mexican Spanish slang" or "Mexican colloquial language," is rich and diverse. It's important to note that slang can vary across different regions of Mexico, and some expressions may not be universally understood.

In this article, we'll explore the meanings behind phrases like "cholo" and "no mames," providing you with real-life examples that you're sure to encounter. Mexican slang adds a unique flair to conversations, reflecting the country's rich cultural culture (and sometimes funny).

However, it's essential to approach it with care, as some expressions can be perceived as impolite or offensive in specific contexts. This guide, featuring three examples for each term, aims to equip you with the knowledge to navigate Mexico with a better understanding of its colorful and diverse linguistic landscape. ¡Vámonos!

Mexican Slang that expresses emotions, reactions, or feelings

- Neta: Truth, really.

¿Neta no sabías? (You really didn't know?)

Neta que yo si te amo (For real that I love you)

¿Es neta? (Is it true?)

- Padre: Cool, great.

Esa fiesta estuvo bien padre. (That party was really cool.)

Que padre es tu ropa de hoy (Your outfit today is great)

¡Que padre estuvo el viaje! (The trip whas really cool!)

- Chido or Chida: Cool, awesome.

Esa película estuvo bien chida (That movie was really cool.)

El lugar está chido (The place is awesome)

Oye y qué tal el concierto, ¿Chido? (Hey and how was the concert, Cool?)

- ¡Aguas!: Watch out, be careful.

Aguas con ese perro. (Watch out for that dog.)

¡Aguas, se aproxima una tormenta! (Alert, a storm is approaching!)

¡Aguas! Me gané la lotería. (No way! I won the lottery.)

- Mande: What, or excuse me, you can use it when you didn't hear what someone said.

¿Mande? (What?)

Mande, no te escuché. (What? I didn't hear you.)

Mande, ¿Podrías repetir por favor? (Excuse me, Could you repeat please?)

- No Mames: Literally, it means "Don't suck" or "Don't suck it." However, it can express disbelief, surprise, or frustration, like saying "No way!" or "Are you kidding me?".

Remember that "mames" is derived from a vulgar expression, so while "no mames" itself is not vulgar, it is a colloquial phrase and may not be appropriate in all settings.

¡No Mames Guey! (No kidding, bro!)

¡No mames! ¿En serio ganamos el partido? (No way! Did we really win the game?)

No mames, ¿crees que voy a caer en esa trampa? (Come on, do you really think I'll fall for that trick?)

- Chale: this is an expression of disappointment or disapproval.

Chale, no tengo dinero. (Darn, I don't have money.)

Chale, no deberías haber hecho eso. (Dude, you shouldn't have done that.)

Chale, olvidé mi celular en casa. (Ugh, I forgot my phone at home.)

- Machín: Very, a lot, or intensely.

Está machín caliente hoy. (It's very hot today.)

¡Esa película estuvo machín buena! (That movie was extremely good!)

Ese coche es machín caro. (That car is extremely expensive.)

- Chingón or Chingona: Awesome, excellent, or cool.

¡Esa película estuvo bien chingona! (That movie was really awesome!)

¿Fuiste al museo? Está chingón (Did you went to the museum?, is excellent )

Tu nuevo celular es muy chingón (Your new cellphone is really cool)

- Está cañón: It's tough or difficult.

Hacer ejercicio todos los días está cañón. (Exercising every day is tough.)

Los tiquetes están muy caros, está cañon viajar así (The tickets arevery expensive, is really difficult to travel like that)

Estudiar para el examen final está cañón. (Studying for the final exam is tough.)

Mexican Slang that describes people

- Cuate: Friend, buddy.

Voy a salir con mis cuates. (I'm going out with my buddies.)

Este cuate está bien elegante (This buddy is very elegant)

Estoy muy orgulloso de mi cuate (I’m very proud of my friend)

- Chismoso o Chismosa: Gossipy, someone who likes to gossip.

No seas chismoso. (Don't be so gossipy.)

La señora de la esquina es bien chismosa (The lady at the corner is really gossipy)

A veces, me gusta ser chismoso (Sometimes I like to be gossipy)

- Güey: Dude, guy. Depending on context, it can be used affectionately or as an insult.

¡Ay güey, qué onda! (Hey dude, what's up!)

¡No mames, güey, me asustaste! (Dude, seriously, you scared me!)

Vamos al cine, güey. (Let's go to the movies, buddy.)

- Naco or naca: Used to describe someone as low-class or lacking sophistication. However, it can be offensive, so use it with caution.

No seas naco. (Don't be tacky/low-class.)

Viste con ropa muy naca. (You dress in very tacky clothes.)

No seas naco, comportate mejor. (Don't be tacky, behave better.)

- Jefa or Jefe: Mom,Dad or boss.

Mi jefa no me dejó salir ayer. (My mom didn't let me go out yesterday.)

Vamos a salir, ¿te apuntas, jefe? (We're going out, are you coming, buddy?)

Tú eres el jefe aquí. (You're the boss here.)

- Cholo: it often refers to someone associated with a particular subculture characterized by a distinctive style, including baggy clothing, tattoos, and a certain attitude.

Mira a ese cholo con los tatuajes. (Look at that guy with the tattoos, he looks like a cholo.)

El barrio está lleno de cholos. (The neighborhood is full of cholos.)

¿Qué onda, cholo? ¿Cómo estás? (What's up, dude? How are you?)

- Cafre: Someone rough, rude, or uncouth.

Ese tipo es un cafre. (That guy is rude.)

Es tan cafre, siempre interrumpiendo a los demás. (He's so rude, always interrupting others.)

¡Deja de ser tan cafre, no puedes hablar así! (Stop being so rough, you can't speak like that!)

- Cuateco: Describe someone or something as elegant, stylish, or sophisticated.

Hoy quiero vestirme bien cuateco para la reunión. (Today, I want to dress stylishly for the meeting.)

Siempre ha tenido un estilo cuateco, incluso en la universidad. (He/she has always had a sophisticated style, even in college.)

A ella le encanta lucir un look cuateco en eventos importantes. (She loves showcasing a stylish look at important events.)

Mexican Slang that are actions or situations

- Chamba: Job or work.

Estoy buscando chamba. (I'm looking for a job.)

Esta es mi primera chamba. (This is my first job)

Mañana tengo mucha chamba en la oficina. (Tomorrow, I have a lot of work at the office.)

- Bronca: Problem or trouble.

Tuve una bronca en el trabajo. (I had a problem at work.)

Hubo una bronca en el bar anoche. (There was a problem at the bar last night.)

Tuve una bronca con el coche esta mañana. (I had a problem with the car this morning.)

- Pedo: Having a problem, trouble, or situation - Or being really drunk.

No hay pedo. (No problem.)

Tuve un pedo en el trabajo. (I had a problem at work.)

Estaba muy pedo anoche. (I was very drunk last night.)

- Cotorreo: Hanging out or having a good time.

Vamos a echar cotorreo. (Let's go have some fun.)

La fiesta estuvo llena de cotorreo. (The party was full of fun.)

Siempre hay buen cotorreo en ese bar. (There's always a good time at that bar.)

- Chingar: This word can have various meanings depending on the context, including to bother, annoy, or work hard.

No me chingues, estoy ocupado. (Don't bother me, I'm busy.)

Hay que chingarle para tener éxito. (You have to work hard to be successful.)

Está lloviendo a chingar. (It's raining like crazy.)

- Aguantar vara: To endure or tolerate a difficult situation.

Hay que aguantar vara en el trabajo. (We have to endure a lot at work.)

En el ejército, aprendí a aguantar vara. (In the army, I learned to endure hardships.)

Esta semana ha sido difícil, pero hay que aguantar vara. (This week has been tough, but we have to endure it.

- Peda: Party or getting drunk.

Vamos a echar la peda este sábado. (Let's party this Saturday.)

La peda estuvo increíble. (The party was amazing.)

¿Te unes a la peda esta noche? (Do you want to join the party tonight?)

Mexican Slang to describe things

- Chela: Beer.

Voy por unas chelas. (I'm going for some beers.)

Esta noche vamos a comprar chelas. (Tonight, we're going to buy some beers.)

¿Quieres una chela? (Do you want a beer?)

- Varo: Money or cash.

No tengo varo para salir hoy. (I don't have money to go out today.)

Vamos a echar varo entre todos para la cena. (Let's all pitch in money for dinner.)

Me costó una flor de varo arreglar el coche. (It cost me a lot of money to fix the car.)

- Chacharita: Trinket or small item, often used to describe something cute.

Compré unas chacharitas en el mercado. (I bought some cute trinkets at the market.)

Siempre me gusta comprar chacharitas cuando voy de vacaciones. (I always like to buy trinkets when I go on vacation.)

Le regalé unas chacharitas que encontré en la feria. (I gave her some charming trinkets I found at the fair.)

- Chirris: Small, insignificant things or items.

No olvides recoger tus chirris antes de irte. (Don't forget to pick up your small things before leaving.)

Voy a ordenar los chirris en mi escritorio. (I will tidy up the small items on my desk.)

Antes de salir, recoge los chirris que dejaste en la sala. (Before leaving, pick up the small things you left in the living room.)

- Chunche: Thingamajig, gadget, or any unspecified object.

¿Dónde dejé el chunche ese? (Where did I leave that thing?)

Estoy buscando el chunche que necesito para arreglar la lámpara. (I'm looking for the thingamajig I need to fix the lamp.)

Vamos a guardar todos los chunches en la caja. (Let's put away all the miscellaneous items in the box.)

Mexican Slang emerges as a valuable tool for those seeking a deeper connection with the vibrant culture of Mexico. With expressions tailored to every emotion, description of people, daily actions, and things, learning Mexican Slang becomes essential to understanding conversations and situations.

For travelers, it serves as a linguistic compass, offering insights into Mexican communication and facilitating a more immersive experience. Knowing these expressions is not just about mastering words; it's about understanding the heartbeat of the culture, connecting with locals on a personal level, and enriching the overall experience.

As part of learning Spanish, for example, exploring Mexican Slang is not merely an academic exercise; it's an invitation to delve into the dynamic and practical side of the language. It's about embracing the diversity of expressions that mirror real-life scenarios and foster a genuine connection with the people and places encountered during the learning process.

So, whether you're a language enthusiast, a traveler, or someone on a quest for cultural understanding, delving into Mexican Slang is a practical and enriching step toward mastering the art of communication in Spanish. ¡Hasta luego! (Until next time!)

What makes Mexican Slang unique?

Mexican Slang is a vibrant and dynamic language aspect that reflects Mexico's rich cultural tapestry. It incorporates regional influences, historical context, and a blend of indigenous and Spanish elements, making it a unique and colorful form of expression.

How do Mexicans use slang to express emotions?

Mexican Slang offers a nuanced way to express emotions, from joy and excitement to frustration and disbelief. Phrases like "¡No mames!" convey strong reactions, while "¡Qué chido!" expresses enthusiasm and approval in a distinctly Mexican way.

Are there regional variations in Mexican Slang?

Yes, Mexican Slang can vary regionally, with different areas adopting their own unique expressions and idioms. Local influences, historical factors, and cultural diversity contribute to Mexico's rich tapestry of slang.

Is it appropriate to use Mexican Slang in formal settings?

While Mexican Slang adds flair to casual conversations, using it with caution in formal settings is essential. In professional or formal contexts, sticking to standard Spanish is advisable to ensure clarity and respect.

How can non-Spanish speakers learn and understand Mexican Slang?

Learning Mexican Slang involves immersing oneself in the language, culture, and daily interactions. Conversing with native speakers, watching Mexican movies or TV shows, and exploring regional expressions can help non-Spanish speakers grasp the nuances of Mexican Slang.

Related Articles

How to Learn Spanish Fast: The Complete Guide for Beginners

¡Hola!: Learn How to Say Hello in Spanish

Telling Time in Spanish: A Complete Guide for Beginners

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Mexican Slang: 90+ Spanish Slang Words and Expressions to Sound Like a Local (with Audio and a Quiz)

Looking to have a huge head start when you travel to Mexico?

You’ve gotta learn the slang.

In this post, I’m going to give you a brief introduction to the country’s unique version of Spanish—and by the time we’re done, you’ll be better prepared to navigate a slang-filled conversation with Mexicans!

The Most Common Mexican Slang Words and Expressions

1. ¡qué padre — cool, 2. me vale madre — i don’t care, 3. poca madre — really cool, 4. fresa — preppy.

- 5. ¡Aguas! — Watch out!

6. En el bote — In jail

7. estar crudo — to be hungover, 8. ¡a huevo — **** yeah, 9. chilango — someone from mexico city, 10. te crees muy muy — you think you’re something special, 11. ese — dude, 12. metiche — busybody, 13. pocho / pocha — a mexican who’s left mexico, 14. naco — tacky, 15. cholo — mexican gangster, 16. güey — dude, 17. carnal — close friend, 18. ¿neta — really.

- 19. Eso que ni que — I agree

20. Ahorita — Right now

21. ni modo — whatever, 22. no hay tos — no problem, 23. sale — okay, sure, 24. coda / codo — someone who’s cheap, 25. tener feria — to have money/change, 26. buena onda — good vibes, 27. ¿qué onda — what’s up, 28. ¡viva méxico — long live mexico.

- 29. Pendejo — Jerk

- 30. Cabrón — Mean, not very smart, awesome

- 31. Pedo — Drunk, problem

- 32. Pinche — Ugly, cheap

33. Verga — Male genitalia

34. chingar — to f***, 35. ¡no manches / ¡no mames — no way, don’t mess with me, 36. está cañón — difficult, 37. chido — nice, cool, 38. chulo / chula — good-looking person, 39. ¿a poco — really, 40. ¡órale — right on, 41. chela — beer, 42. la tira — the cops, 43. ¿mande — what, 44. suave — cool, 45. gacho — mean, 46. ándale — hurry up, 47. chale — give me a break, 48. chamba / chambear — work, 49. bronca — problem, 50. paro — favor, 51. chido / chida — cool, 52. padre — awesome, 53. chingón — badass, 54. chamba — job, 55. vato — guy, 56. morro — kid, 57. jefa / jefe — mom/dad, 58. vieja / viejo — girlfriend, wife/boyfriend, husband, 59. carnalito — little brother, 60. chiquitín — little one, 61. chavito / chavita — young guy/young girl, 62. camión — bus, 63. chulear — to show off, 64. chingar — to bother, 65. estrenar — to wear or use something for the first time, 66. guacala — yuck, 67. huevón — lazy person, 68. jato — car, 69. mamacita — attractive woman, 70. pisto — money, 71. ¿que pex — what’s up, 72. rola — song, 73. ¿sapbe — what’s up , 74. valedor — friend, 75. vato loco — crazy guy, 76. wacha — look / watch, 77. ¡ya nos cargó el payaso — we’re in trouble, 78. cuate — buddy, 79. jeta — face, 80. madrazo — a strong hit, 81. nalga — buttocks, 82. ñero — dark-skinned person, 83. pacheco — drunk, 84. pirata — fake, 85. relajo — mess, 86. riata — belt, 87. sobres — okay, got it, 88. tapado — conceited, 89. troca — truck, 90. zarape — blanket or shawl, what you need to know about mexican spanish, resources for learning more mexican slang, quick guide to mexican slang, na’atik language and culture institute, why you should learn mexican slang, mexican slang quiz: test yourself.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Mexican slang could be a language of its own.

Just a word of warning: some terms on this list may be considered rude and should be used with caution.

This phrase’s literal translation, “How father!”, doesn’t make much sense at all, but it can be understood to mean “cool!” or “awesome!”

¡Conseguí entradas para Daddy Yankee! (I got tickets for Daddy Yankee!)

¡ Qué padre , güey! (Awesome, dude!)

This phrase is used to say “I don’t care.” It’s not quite a curse, but it can be considered offensive in more formal situations.

If used with the word que (that), remember you need to use the subjunctive .

Me vale madre lo que haga con su vida. (I don’t care what he does with his life).

Literally translated as “little mother,” this phrase is used to describe something really cool.

Once again, this phrase can be considered offensive (and is mostly used among groups of young men).

Esta canción está poca madre . (This song is really cool).

Literally a “strawberry,” a fresa is not something you want to be.

Somewhat similar to the word “preppy” in the United States , a fresa is a young person from a wealthy family who’s self-centered, superficial and materialistic.

Ella es una fresa. (She’s preppy/rich/stuck up).

5. ¡Aguas! — Watch out!

This phrase is used throughout Mexico to mean “be careful!” or “look out!”

Literally meaning “waters,” it’s possible that this usage evolved from housewives throwing buckets of water to clean the sidewalks in front of their homes.

¡Aguas! El piso está mojado. (Be careful! The floor’s wet).

The word bote means “can” (as in a can of soda).

However, when a Mexican says someone is “en el bote,” they mean someone is “in the slammer,” “in jail.”

Adrián no puede venir, ¡está en el bote ! (Adrian can’t come, he’s in jail!)

Estar crudo means “to be raw,” as in food that hasn’t been cooked.

However, if someone in Mexico tells you they’re crudo, it means they’re hungover because they’ve drunk too much alcohol.

Estoy muy crudo hoy. (I’m really hungover today).

Huevos (eggs) are often used to denote a specific part of the male anatomy —you can probably guess which—and they’re also used in a wide variety of slang phrases.

¡A huevo! is a vulgar way to show excitement or approval. Think “eff yeah!” without the self-censorship.

¡Ganamos el partido! (We won the game!)

¡A huevo! Me alegra. (**** yeah! I’m glad)

This slang term means something, usually a person, who comes from Mexico City.

Calling someone a chilango is saying that they’re representative of the culture of the city.

¿Eres chilango ? (Are you from Mexico City?)

This literally means “you think you’re very very” but the slang meaning is more of “you think you’re something special,” or “you think you’re all that.”

Often, this is used to power down someone who’s boastful or thinks they’re better than anyone else.

Te crees muy muy desde que conseguiste ese trabajo. (You think you’re all that since you got that job).

Supposedly, in the 1960s members of a Mexican gang called the Sureños (“Southerners”) used to call each other “ese” (after the first letter of the gang’s name).

However, in the ’80s, the word ese started to be used to refer to men in general, meaning something like “dude” or “dawg”.

It’s also possible ese originated from expressions like ese vato (“that guy”), and from that, the word ese started to be used to refer to a man.

“¿Qué pedo, ese ?” “What up, dawg?”

Metiche is a slang word for someone who loves to get the scoop on everyone’s everything.

Some people would refer to this sort of person as a busybody!

¿De qué hablaste con tu amiga? (What did you talk about with your friend?)

Nada, ¡no seas tan metiche ! (Nothing, don’t be such a busybody!)

This Mexican slang term refers to a Mexican who’s left Mexico or someone who’s perhaps forgotten their Mexican roots or heritage.

It can be used as just an observatory expression, but also as a derogatory slang word used to point out that someone’s at fault for not remembering their heritage.

Mis primos pochos vienen a visitar este fin de semana. (My pocho cousins are coming to visit this weekend).

Naco is a word used to describe someone or something poorly educated and bad-mannered.

The closest American equivalent would be “tacky” or “ghetto.”

The word has its origins in insulting indigenous and poor people, so be careful with this word!

Me parece un poco naco . (It seems a bit tacky).

Although the word cholo can have several meanings, it often refers to Mexican gangsters, especially Mexican American teens and youngsters who are in a street gang.

Vi unos cholos en la esquina. (I saw some gang members on the corner).

This one is pronounced like the English word “way” and it’s one of the most quintessential Mexican slang words.

Originally used to mean “a stupid person,” the word eventually morphed into a term of endearment similar to the English “dude.”

¡Apúrate, güey ! (Hurry up, dude!)

Carnal comes from Spanish carne (meat).

It’s perhaps for this reason that carnal is used to describe a close friend who’s like a sibling to you, carne de tu carne or flesh of your flesh.

Allí está mi carnala Laura . (There’s my close friend Laura).

“Truth?” or “really?” is what someone’s saying when they use this little word.

This popular conversational interjection is used to fill a lull in the chatter or to give someone the opportunity to come clean on an exaggeration.

Oftentimes, though, it’s just said to express agreement with the last comment in a conversation or to clarify something.

¿ Neta ? Pero ¿qué pasó? (Really? But what happened?)

19. Eso que ni que — I agree

Don’t try to translate this literally—just know that this convenient phrase means that you’re in agreement with whatever’s being discussed.

Es muy bueno para bailar. (He’s really good at dancing).

Sí, baila mejor que todos, eso que ni que . (Yes, he dances better than everyone, no doubt about it).

This translates as “little now” but the small word means right now, or at this very moment.

¡Tenemos que irnos ahorita ! (We have to leave right now!)

Ni modo , which can be literally translated as “not way” or “either way,” is possibly one of the most popular Mexican expressions.

It’s generally used to say “eh, whatever” or “it is what it is.”

Ni modo can also be used with que (that) and a present subjunctive to say you can’t do something at the moment or there’s no way you’d do it.

It’s like saying “there’s no way” or “are you nuts?” in English.

Ni modo , hay mejores chicas/chicos en el mundo. (Oh well, there are better girls/guys in the world)

Ni modo que conteste, güey. (There’s no way I’m answering, man).

No hay tos literally means “there’s no cough,” but it’s used to say “no problem” or “don’t worry about it.”

Lo siento, me olvidé mi billetera. ¿Tienes plata? (Sorry, I forgot my wallet. Do you have cash?)

No, pero no hay tos , comamos en la casa. (No, but no problem, let’s eat at home).

Sale means “okay,” “sure,” “yeah” or “let’s do it,” so it’s normally used in situations when someone suggests doing something and you agree.

It can also be used as a question tag when you want someone’s opinion or to see if they’re on the same page as you.

¿Vamos al concierto? (Shall we go to the concert?)

Sale , pero tendrás que prestarme lana. (Sure, but you’ll have to lend me some money.)

Codo literally means “elbow” in English but Mexican slang has turned it into a term used to describe someone who’s cheap.

It can be applied to either gender, so pay attention to the -a or -o ending of this descriptive noun.

¡Ese codo ni pagó la cena! (That cheapskate didn’t even pay for dinner!)

Feria means “fair” so the literal translation of this expression is “to have or be fair.”

However, feria also refers to coins when it’s used in Mexico. So, the phrase basically means “to have money” or “to have pocket change.”

¿Tienes feria ? (Do you have money?).

Buena onda literally translates to “good wave” but it’s used to indicate that there are good vibes or a good energy present.

Tienes buena onda . (You give off good vibes).

This slangy Mexican expression translates to “what wave?” but is a cool way to ask “what’s up?”

It’s another feel-good, casual conversational expression that really adds a lot of good feelings to any chat.

¿ Qué onda ? ¿Cómo has estado? (What’s up? How have you been?)

¡Viva México! literally means “long live Mexico!”

It’s the unifying phrase that says the country should grow, prosper and see happy times for its citizens and visitors.

It’s often shortened to “¡viva!” which means the same as the full phrase .

¡Ganamos el mundial! ¡ Viva México ! (We won the world cup! Long live Mexico!)

29. P endejo — Jerk

Pendejo is one of those magical words that appear in almost every Spanish variety but have a different meaning depending on where you are.

In Mexico, it has a rather rude meaning: “unpleasant or stupid person,” “jerk.”

No me hables, pendejo . (Don’t talk to me, jerk).

30. C abrón — Mean, not very smart, awesome

While technically cabrón means “big [male] goat,” it has plenty of other meanings.

Used as a rude word its meaning is quite similar to pendejo, but cabrón is higher in the rudeness scale: meaning unpleasant, mean or not very bright.

But change the tone a bit and you might, instead, be saying someone is awesome!

The word can even be used in place of the f-bomb, very often following bien— very, to mean you’re really awesome at doing something.

Soy bien cabrón jugando a Minecraft. (I’m friggin’ awesome at playing Minecraft).

31. P edo — Drunk, problem

A pedo is a fart, literally.

This word has lots of different meanings, depending on how you say it and the situation:

- Estar pedo — to be drunk

- Peda — drinking session

- Ser buen pedo — to give off good vibes

- Ser mal pedo — to be unfriendly or hostile

- ¿Qué pedo? — what’s up?

- Pedo — problem or argument

- Ponerse al pedo — to want a fight, or to have an attitude of defiance

- ¿Qué pedo contigo, cabrón? (What’s your problem, man?)

Here’s Mexican actress Salma Hayek explaining qué pedo and other Mexican slang:

32. P inche — Ugly, cheap

The word pinche may sound quite unproblematic for many Spanish speakers because it literally means “kitchen helper.”

However, when in Mexico, this word goes rogue and acquires a couple of interesting meanings.

It can mean “ugly,” “substandard,” “poor” or “cheap,” but it can also be used as an a ll-purpose enhancer, much like the meaner cousin of “hecking” is used in English.

Eres un pinche loco . (You’re effing crazy).

Originally, the verga was the horizontal beam from which a ship’s sails were hung, but this word has come to mean a man’s schlong in Spanish nowadays.

You can also use this word as a standalone exclamation with the meaning of the f-bomb.

Here are a few more uses of the word:

- Creerse verga — to think you’re all that

- Valer verga — to be worthless

- Irse a la verga — a “lovely” way of telling someone to eff off

- Tus palabras me valen verga . (Your words mean nothing to me).

Chingar means “to do the deed.” It’s Mexico’s version of the f-word. Simple.

Chingar is a word that’s prevalent in Mexican culture in its various forms and meanings.

¡Deja de chingar ! (Stop f***ing around!)

These two phrases are essentially one and the same, hence why they’re grouped together.

Literally meaning “don’t stain!” and “don’t suck,” these are used to say “no way! You’re kidding me!” or “don’t mess with me!”

No manches is totally benign, but no mames is considered vulgar and can potentially be offensive.

¡No manches! ¿Pensé que habían terminado? (No way! I thought they had broken up?)

Here are actors Eva Longoria and Michael Peña explaining no manches and other Mexican slang words:

When you say that something is está cañón (literally, “it’s cannon”), you’re saying “it’s hard/difficult.”

Some believe that the phrase arose as a more polite euphemism for está cabrón.

As a Spaniard, I find this meaning quite funny, because estar cañón means “to be very attractive” in Castilian Spanish.

El examen estuvo bien cañón . (The exam was very difficult).

This word is simply a fun way to say “nice” or “cool” in Mexican Spanish.

Despite its status as slang, it’s not vulgar or offensive in the least—so have fun with it!

It can be used as both a standalone exclamation (¡qué chido! — cool!) or as an adjective.

Tienes un carro bien chido. (You have a really cool car).

When it comes to Mexico, chulo is used as an adjective to refer to people you find hot, good-looking or pretty.

You can also use it to refer to things with the meaning of “cute,” however if you travel to Spain, don’t use this word to refer to people—since a chulo is “a pimp.”

¿Viste ese chulo en la panadería? (Did you see that hot guy in the bakery?)

There’s no way to translate this one literally, it just comes back as nonsense. Mexicans, however, use it to say “really?” when they’re feeling incredulous.

Ale dijo que ganó la lotería! (Alex said that he won the lottery!)

¿ A poco ? ¿Lo crees? (Really? Do you believe him?)

This exclamation basically means “right on!” or in some situations is used as a message of approval like “let’s do it!”

Órale is another Mexican slang word that’s considered inoffensive and is appropriate for almost any social situation.

It can be said quickly and excitedly or offered up with a long, drawn-out “o” sound.

Creo que te puedo ganar. (I think I can beat you).

¡Órale! A ver. (Bring it on! Let’s see).

Simple enough, chela is a Mexican slang word for beer.

In other parts of Latin America, chela is a woman who’s blond (usually with fair skin and blue eyes).

No one is quite sure if there’s a link between the two, and it seems unclear how the word came to mean “beer” in the first place.

¿Quieres tomar unas chelas ? (Do you want to have a few beers?)

A tira is a “strip,” but when you use it as a Mexican slang word, you mean the cops.

¡Aguas! ¡Ahí viene la tira ! (Watch out! The fuzz are coming!)

This is used in Mexico in place of ¿qué? or ¿cómo? to respond when someone says your name.

Luis, ¿estás allí? (Luis, are you there?)

¿ Mande ? ¿Me llamaste? (What? Did you call me?)

Technically, suave translates to “soft,” but suave is a way to say “cool.”

¡Ese mural es suave ! (That mural is cool!)

This literally means “slouch,” but it’s used to say something is mean or ugly .

Enrique es gacho . (Enrique is mean.)

Andar means “to walk,” so ándale is a shortened version of the verb combined with the suffix “- le ,” a sort of grammatical placeholder that adds no meaning to the word.

Use this to tell someone to hurry up .

¡ Ándale ! Necesitamos estar ahi a las 8. (Hurry up! We need to be there at 8.)

Chale doesn’t really have a clear literal translation, but it’s most often used to show your annoyance.

It’s similar to the English “give me a break.”

Su coche tardará dos semanas en arreglarse. (Your car will take two weeks to fix.)

¡Chale! (Give me a break!)

Chamba and chambear mean “work” and “to work,” respectively.

No me gusta mi chamba. (I don’t like my job.)

The word bronca means “problem,” and it’s used in expressions like no hay bronca (“no problem”) and tengo broncotas (“I’m in big trouble”).

Mi familia tiene broncas con mi hermano. (My family has problems with my brother.)

Though the official word for “favor” in Spanish is the cognate favor, paro is another way of referring to a favor in Mexico.

Hazme el paro means “do me a favor.”

Puedes hacerme el paro ? (Can you do me a favor?)

Though “cool” in Spanish is commonly expressed as genial , chido is a colloquial way of describing something as cool or awesome in Mexican slang.

Esa película estuvo bien chida . (That movie was really cool!)

Similar to chido , padre is another slang term used to convey that something is awesome or great.

¡La fiesta estuvo bien padre ! (The party was really awesome!)

Chingón is an informal term used to describe something or someone as extraordinary, impressive, or badass.

¡Ese tatuaje está bien chingón ! (That tattoo is really badass!)

Chamba is a slang term used to refer to work or a job.

Tengo mucha chamba esta semana . (I have a lot of work this week.)

Vato is a slang term for a guy or dude.

Ese vato es muy amable . (That guy is very friendly.)

Morro is an informal term for a young boy.

Mi hermanito es un buen morro . (My little brother is a good kid.)

Jefa and jefo, which both mean “boss” are just informal terms for “mom” and “dad.”

Mi jefa siempre cocina delicioso . (My mom always cooks deliciously.)

Vieja and viejo , which technically mean “old,” are similar to the English saying of “old man,” referring to a boyfriend, or “old lady,” referring to one’s girlfriend or wife.

Salí con mi vieja al cine . (I went to the movies with my girlfriend.)

Carnalito is a diminutive form of carnal , referring to a younger brother.

Mi carnalito siempre quiere jugar . (My little brother always wants to play.)

Chiquitín is an affectionate term for someone small or younger.

¡Hola, chiquitín ! ¿Cómo estás? (Hi, little one! How are you?)

These are affectionate slang terms for a young man or young woman.

Ese chavito es muy talentoso . (That young guy is very talented.)

Camión which literally means “truck,” is a colloquial term for a bus.

Voy a tomar el camión a la escuela . (I’m going to take the bus to school.)

Chulear literally means “to pimp,” but in Mexico, it’s a verb used to describe showing off or flaunting something.

Deja de chulear tu nuevo auto . (Stop showing off your new car.)

Here’s a great explanation of chulear (in Spanish):

Chingar is a versatile verb with various meanings, but it can be used to express annoyance or bother.

No me chingues , estoy ocupado . (Don’t bother me; I’m busy.)

Estrenar is a verb used when someone wears or uses something for the first time.

Voy a estrenar mis zapatos nuevos hoy .

This expression is an informal way to express disgust or dislike, similar to saying “yuck” in English.

¡ Guacala ! Esta comida no tiene buen sabor . (Yuck! This food doesn’t taste good.)

Used to describe someone who is lazy, this term is derived from the word huevo, meaning “egg,” which is associated with laziness.

Mi amigo es muy huevón , siempre está descansando . (My friend is very lazy, he’s always resting.)

While the standard term for “car” is coche , jato is a slang word used in Mexico to refer to a car or automobile.

Vamos en mi jato al cine esta noche . (Let’s go to the movies in my car tonight.)

Used as a term of endearment, mamacita refers to an attractive or beautiful woman.

¡Ay, mamacita , estás muy guapa hoy! (Oh, beautiful, you look very pretty today!)

This slang term is used to refer to money, similar to saying “cash” in English.

Necesito un poco de pisto para el transporte . (I need some cash for transportation.)

An informal and colloquial way of asking “what’s up?” or “what’s going on?”

¿ Qué pex, cómo estás? (What’s up, how are you?)

Used to refer to a song or piece of music, rola is a common slang term in Mexican Spanish.

Esta rola es mi favorita. (This song is my favorite.)

An alternative and informal way of asking “what’s up?”

Sapbe , nos vemos en el centro . (What’s up, see you downtown.)

Literally meaning “brave,” this slang term simply means “good friend.”

Mi valedor siempre está allí para ayudarme . (My friend is always there to help me.)

Describes someone as a crazy or wild guy, often used in a lighthearted or affectionate manner.

Mi amigo es un vato loco , siempre hace cosas divertidas . (My friend is a crazy guy, always doing funny things.)

Wacha , which is taken from the English “watch,” is an informal and colloquial way of saying “look” or “watch.”

Wacha esa película, está buenísima . (Look at that movie, it’s really good.)

This expression is used to convey that a difficult or troublesome situation has arisen. It literally means “the clown has already killed us.”

Se nos olvidaron las entradas, ya nos cargó el payaso . (We forgot the tickets, we’re in trouble.)

An informal term used to refer to a friend or buddy, indicating camaraderie.

Ese cuate siempre me ayuda cuando lo necesito . (That buddy always helps me when I need it.)

Used to refer to someone’s face, especially when expressing a negative emotion. It’s just like the English “mug.”

No me gusta su jeta , siempre está enojado . (I don’t like his face, he’s always angry.)

This slang term is used to describe a strong hit or punch.

Le di un madrazo al balón y entró en la portería . (I gave the ball a strong hit and it went into the goal.)

This slang term, literally “cheek,” is used informally to refer to this part of the body.

Le dieron un golpe en la nalga . (They gave him a hit on the buttocks.)

Although “dark-skinned person” is a direct translation, ñero is a colloquial term used in some regions to describe someone with a dark complexion. Be careful not to offend with this one.

No importa si eres ñero o güero, todos somos iguales . (It doesn’t matter if you’re dark-skinned or fair-skinned, we are all equal.)

Pacheco is often used in Mexico to describe someone who is intoxicated or inebriated.

No puedo hablar con él cuando está pacheco . (I can’t talk to him when he’s drunk.)

Go deeper into pacheco here:

Literally meaning “pirate,” this term is often used in Mexican slang to describe counterfeit or knockoff items.

No compres ese reloj, es pirata . (Don’t buy that watch, it’s fake.)

This literally means “relax,” but in Mexican slang, it means a mess, or a chaotic or disorderly situation.

No quiero más relajo en casa . (I don’t want more mess in the house.)

This slang term for a belt is often used in casual or regional contexts.

Me apreté la riata para que no se me cayera el pantalón . (I tightened the belt so my pants wouldn’t fall.)

Literally meaning “envelopes,” this term means “I got it,” a casual way of expressing understanding or acknowledgment.

—¿Vamos al cine mañana? —¡ Sobres ! (Are we going to the movies tomorrow? – Okay, got it!)

While “covered” is the direct translation, tapado is a slang term used in some regions to describe someone who is arrogant or full of themselves.

No me gusta hablar con él, está muy tapado . (I don’t like talking to him, he’s very conceited.)

Instead of the standard camión , troca is commonly used in Mexico to refer to a pickup truck or a large vehicle.

Vamos a cargar la troca con las cosas para la mudanza . (Let’s load the truck with the things for the move.)

Zarape specifically refers to a colorful Mexican blanket or shawl often used for warmth or decoration.

Me envolví en el zarape porque hacía frío . (I wrapped myself in the blanket because it was cold.)

Check out this video to hear some of these Mexican slang words in context:

Here’s some good things to know about Mexican Spanish:

- In Mexican Spanish, the pronoun t ú is used for the second-person familiar form. Mexicans don’t use v os .

- The pronoun vosotros isn’t used in Mexican Spanish. Mexicans use ustedes even in informal settings.

- Mexican Spanish features more loanwords from English than other national dialects. You will hear a lot more English words in Mexican Spanish than other dialects.

This is a compact volume filled with definitions, example sentences, online links and lots of relevant information about Mexican Spanish.

There are more than 500 words and phrases included in this book.

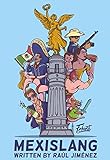

“Mexislang” is the end result of a blog that was intended to teach readers about Mexican slang.

It offers insight into the history of slang expressions and tips for how to use each word or phrase.

The option to stay with Mexican families to immerse in the language is a great way to learn about culture—including slang!

But if you’re not up for traveling, courses are also available in online one-on-one or small group format.

Online classes focus on grammar and conversational skills, so you’re sure to pick up plenty of slang along the way.

Also, they have a fantastic blog that’s both informative and entertaining.

Like with English, Spanish is spoken differently depending on the country—in fact, you could argue that Spanish differs even more than English!

In order to understand and be understood in Mexican Spanish, it’s pretty essential that you learn some common Mexican slang.

If you’re not convinced, here are some reasons you might want to learn the lingo:

- To avoid awkward situations. Don’t count on every Spanish word being transferable from place to place—something that is perfectly polite in Spanish from Spain could be considered rude in Mexican Spanish.