- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Get New Issue Alerts

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences

From Girls’ Education to Gender-Transformative Education: Lessons from Different Nations

The examination of gender inequality in education around the globe reveals a multifaceted issue deeply intertwined with persistent challenges within education systems and society at large. Over the past three decades, girls’ education has often been portrayed as a panacea, touted as the solution to a wide array of societal problems, including issues as diverse as high fertility rates and global warming. This essay explores gender disparities in education, employing case studies from Latin America to elucidate the intricate dynamics of this global phenomenon and to illustrate the potential of gender-transformative approaches. Drawing upon two decades of empirical research and theoretical insights from the capability approach, I discuss the linkages between gender, education, and social transformation.

Erin Murphy-Graham is an Adjunct Professor in the School of Education at the University of California, Berkeley. She works with local partners from civil society in Honduras and Colombia on issues of education, empowerment, and gender, most recently on the design of Holistic Education for Youth (HEY!), an intervention to prevent adolescent pregnancy and child marriage. Her recent publications include the edited volume Life Skills Education for Youth: Critical Perspectives (with Joan DeJaeghere, 2022) .

Examining gender inequality in education globally brings to the surface many of the deeply rooted and persistent problems in education systems and society more broadly. For the last thirty years, girls’ education has been presented as the “answer to everything,” a cure-all for issues ranging from high fertility rates to global warming. 1 The importance of girls’ education first gained attention in economic discussions during the early 1990s, notably by Lawrence Summers. In his speeches and writings, he argued that education for girls and women might offer the highest return on investment available in the developing world. Since that time, girls’ education has become a global rallying cry for politicians such as Boris Johnson (who referred to girls’ education as the “silver bullet, the magic potion, the panacea . . . that can solve virtually every problem that afflicts humanity”) and celebrities like Lady Gaga, Priyanka Chopra Jonas, and Rihanna. 2 Movie theaters across the globe have shown full-length documentary films about the importance of girls’ education, including Girl Rising (2013) and He Named Me Malala (2015). More recently, girls’ education has been touted as a “powerful climate solution” capable of fighting the root drivers of climate change and cutting carbon emissions. 3 The importance of girls’ education has galvanized action among individuals, organizations, and governments that span a wide range of academic disciplines and political dispositions.

But while some were praising girls’ education as a strategy to improve health outcomes, reduce fertility rates, raise income, and improve democracy, feminist scholars such as Nelly Stromquist argued that the gender gap in education was the manifestation of gender inequality in society. Simply expanding educational access for girls and women would not address the underlying causes of their underrepresentation in education. 4 Getting girls into schools is a necessary first step, but schools often reflect and reinforce harmful social inequalities, including gender norms. An emphasis on empowering girls and women through education and other social interventions (such as small loans, vocational training) began to emerge in the mid-1990s. Education and empowerment of girls became and remain buzzwords, with little conceptual clarity as to what kind of education is empowering, in what context, and for what purpose.

Despite over thirty years of sustained advocacy among various stakeholders, including civil society, multilateral organizations, and networks of feminist scholars, significant gender gaps in education remain, particularly in secondary schooling. The promise of girls’ education as a panacea has not materialized. Looking strictly at gender parity in education—that an equal number of male and female children are enrolled in school—it would appear that girls’ education is a global development success story. But what are girls (and boys) learning in school? How is schooling changing or challenging the social norms that perpetuate inequalities and inequities? The attention to girls’ education sparked a deeper examination in the field of international education development and raised fundamental questions about how to transform educational systems to become more appropriate for today’s world. 5

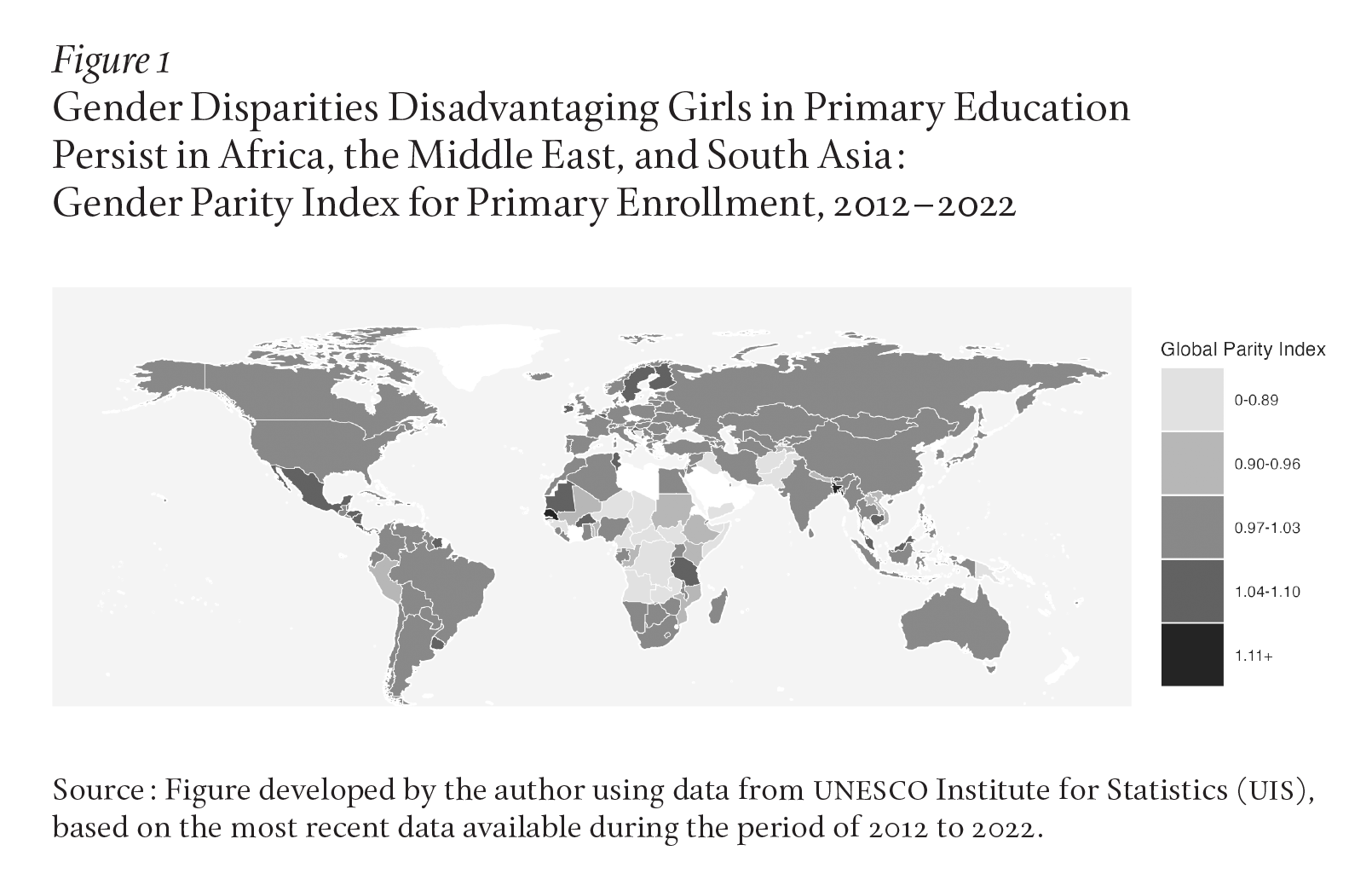

With the caveat that any brief review of international data is insufficient, it is a useful starting point for an exploration of gender and education around the globe. More girls participate in education and at higher levels than ever before. As Figure 1 illustrates, gender disparities continue to exist in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia, but many countries have equal participation in schooling at the primary level.

Significant historical turning points and international movements that have spurred this progress include the Education for all Movement (launched in 1990 and renewed in 2000) and the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women and resulting Beijing Platform for Action. These convenings and subsequent declarations promulgated a set of principles, policy orientations, and actions. Among these were the goals of providing universal access to, and ensuring the completion of, primary education for all girls and boys and eliminating gender disparities in education. The United Nations’ most recent international development goals, known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, adopted by UN member states in 2015) include a target (4.1) to, “By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes.” 6

In 2016, the gender review that accompanies UNESCO’s annual Global Education Monitoring Report found that by 2014, gender parity was achieved globally, on average, in primary, lower-secondary, and upper-secondary schools. 7 Key here (as the report points out) is that parity can wash away inequalities when comparing across countries or world regions. Parity is a statistical measure that provides a numerical value of female-to-male or girl-to-boy ratios. The problem is that in some countries and regions, girls are underrepresented in education, whereas in others, boys are underrepresented. Calculated as an average, these disadvantages are masked—and we have “global parity.”

By 2022, the language around gender parity had softened somewhat, with UNICEF’s launch of a website with the headline, “most countries have achieved gender parity in primary enrollment, but in many countries, disparities disadvantaging girls persist.” 8 There are two key concerns associated with using gender parity as an indicator of gender equality. First, it masks both female and male disadvantage in education. As captured by a recent UNESCO global report on boys’ disengagement from education, boys are more likely than girls to repeat primary grades in one hundred thirty countries, and more likely not to have an upper-secondary education in seventy-three countries (the report features in-depth case studies from Fiji, Kuwait, Lesotho, Peru, and the United Arab Emirates). 9 Second, parity in both educational enrollment (children currently enrolled in school) and attainment (highest grade completed) does not necessarily translate into parity in learning outcomes. In a study measuring gender equality in education from forty-three low- and middle-income countries, the authors explain that in some settings, increases in enrollment may have led to a deterioration in the quality of education and a lower proportion of young people with basic literacy and numeracy skills. 10

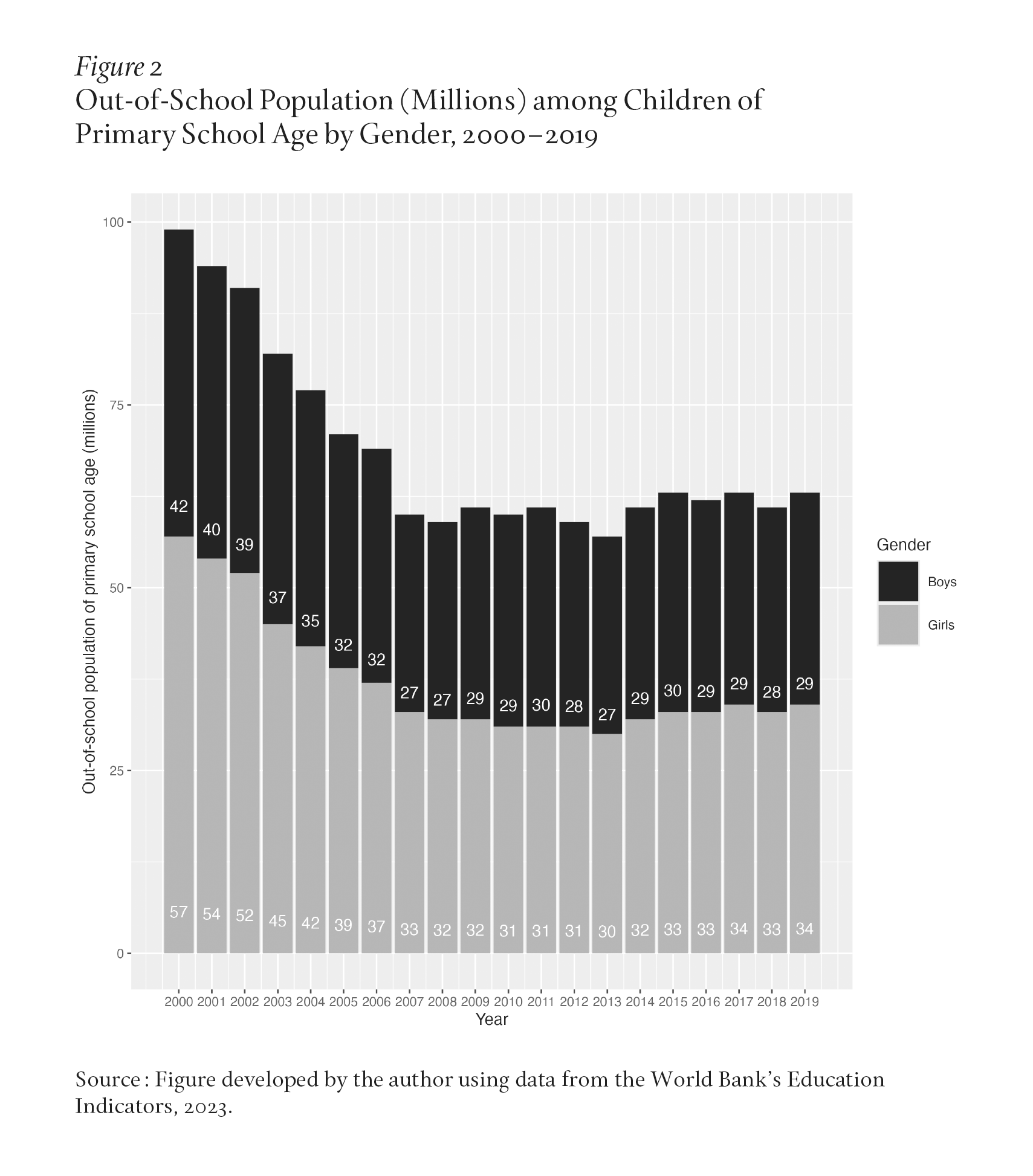

In addition to examining the flawed statistic of educational parity in enrollment, common indicators of gender inequality also include the number of children out of school, as well as the number who complete primary, lower-secondary, and upper-secondary education. According to data from the World Bank, the primary school completion rate for girls has reached 90 percent globally, with an equal number of boys and girls completing primary school in most countries. Between 2000 and 2018, the number of out-of-school girls of primary school age decreased globally from fifty-seven million to thirty-two million. 11 As of 2023, roughly thirty-two million girls of primary school age were still out of school, compared with twenty-seven million boys. So while a roughly equal number of girls and boys are enrolled in primary school (gender parity), this statistic misses the more than fifty million children that remain out of school, and that more girls are out of school than boys. 12 Figure 2 shows trends in the out-of-school population of primary school–aged children between 2000 and 2019.

With regard to primary school completion, in 2013, only 70 percent of children in low-income countries completed primary school, and only 14 percent completed secondary school. 13 Five years later, in 2018, estimates suggested that just 54.8 percent of children in low-income countries completed primary school. The COVID pandemic only added to the obstacles that children face in completing their primary education. 14

There is general agreement that achieving target 4.1 of the SDGs remains a “distant reality.” 15 Global estimates of the gender gap in out-of-school rates are not informative because they mask regional variation. Additionally, looking at a global average can be misleading because the female advantage in some world regions zeros out the female disadvantage in others. As of 2023, the largest gender gaps disadvantaging girls remained at each level of the education system in sub-Saharan Africa and in Northern Africa and Western Asia. Likewise, in low-income countries, enrollment rates for young women in lower-secondary education were still 5 percentage points below that of young men; at the upper-secondary level, the female disadvantage was 9 percentage points. And most low- and middle-income countries have low overall rates of enrollment and attainment, particularly in the lower- and upper-secondary levels.

What can we take away from this picture? First, gender gaps in education are a misleading indicator of progress. Second, for schools to not reflect or reproduce social inequalities but rather change the underlying roots of students’ gendered educational experiences, we need a more substantive understanding and recognition of what gender equality in education could or should entail across different contexts. The statistics help us see the symptoms of a much larger and more complex disease. Education, particularly gender-transformative education, could be leveraged as a process to heal and repair social systems that reflect patriarchy, colonialism, and racism. 16

In a recent article, Elaine Unterhalter, a world-renowned comparative and international education scholar, reviews four key ideas that have framed the formulation of girls schooling and gender equality in education. Her delineation of these four framings helps conceptualize what gender equality in education should (and should not) entail. She calls these framings “what works,” “what disorganizes,” “what matters,” and “what connects.” 17 As general categories, they are useful tools to help understand the range of perspectives, policies, and interventions that characterize the field of girls’ education.

“What works” is the approach consistent with the idea that girls’ education is a sound investment that has positive spillover effects in a variety of different domains (health, economic growth, civil society). It seeks to attain parity: an equal number of boys and girls enrolled in and completing school. This approach is concerned with girls’ education as something that “works” as an intermediary strategy to promote other desirable outcomes (such as poverty alleviation, improved child health and nutrition), as well as being a desirable outcome in and of itself. From this vantage point, policy and research have focused on interventions that increase the number of girls in school and the duration they stay there. These interventions might include reducing or abolishing school fees and/or providing girls with scholarships, reducing the distance to school, building toilets or latrines, providing school meals, and training teachers to improve their pedagogy. The what-works framing proposes largely technical solutions to address girls’ underrepresentation in education. The research methodology to test these approaches involves large-scale, randomized control trials to evaluate the effectiveness of a different combination of intervention characteristics. These research studies have helped us understand a great deal about certain kinds of barriers that girls face in attending school, particularly by providing clear and consistent findings that the costs associated with schooling are a huge deterrent for poor families. 18

A second framing, what Unterhalter calls “what disorganizes,” concerns policies and actors that undermine or distract from what works and what matters—and is related to how girls’ education has been identified as a panacea. 19 These are instances where girls’ education is co-opted to promote the interests of large corporations and organizations. An illustrative example of this approach, Nike Inc.’s Girl Effect, is documented extensively in Kathryn Moeller’s book The Girl Effect: Capitalism, Feminism, and the Corporate Politics of Development . 20 Corporations such as Nike, Coca Cola, and Unilever have used the narrative guise of girls’ education and empowerment to expand their markets, improve their reputations, and grow their workforce. But as Moeller points out, their instrumental logic shifts the burden of development onto girls and women without transforming the structural conditions that produce poverty. Their efforts sidestep the practices of harmful business and working conditions, promoting a logic wherein consumption is the goal of development. In one project Unterhalter tags as “disorganizing,” Coca Cola and the British Department for International Development sponsored a £17 million training program for girls who would ultimately “join the Coca Cola value chain.” 21 Corporate social-responsibility initiatives such as these have also been called “gender wash”: corporations clean up their image by using gender, girls’ empowerment, and education as a palatable marketing tool.

Recognizing the contradictions and problematic assumptions of “what disorganizes” in the field of girls’ education is important because it allows for a more profound questioning of “what matters.” A what-matters framing of girls’ education has a long history, as feminists have questioned the logic of “what works” for decades. However, as Unterhalter explains, this approach is supported by international organizations with less status and money, and uses different methods, including qualitative methods, that generate less respect in policy circles and more limited research funding. This makes it difficult to garner evidence that more wholistic, less technocratic approaches “work.” 22 A what-matters stance situates girls’ education in a wider, normative context linked to advancing human rights, gender equality, feminist advocacy, and ultimately a different vision of prosperity and well-being. Many writers and activists in this category emphasize girls’ voices and empowerment, the limitations of policy texts, and the need for a more comprehensive understanding of the cultural norms and practices connected with gender inequality across cultural contexts. Additionally, the meanings of “gender” and the questioning of gender binaries, heteronormativity, sexism, and patriarchy are considered from this stance.

Writers from this perspective, including myself, emphasize that girls’ education makes up one element of advancing gender equality. To transform social structures and society at large, processes of change must come from political, economic, social, and cultural domains. Education, no matter how empowering, cannot singularly address all of society’s ills. 23 A framework for human flourishing known as the “capability approach” also undergirds questions of what matters and serves as a lodestar for envisioning a more prosperous and just future. The capability approach, developed initially by philosophers Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen, captures aspects of people’s lives such as their education, health, and their political and religious freedoms, and shifts the discourse on education from one emphasizing human capital to one that focuses on human capabilities. 24 Informed by the capability approach, many feminist authors have called for educational reforms that reflect a more nuanced and complex theorization of the role of education in promoting social justice. 25

Informed by the capability approach, Unterhalter proposes the framing of “what connects” to bring together what matters and what works. A coupling of these perspectives aspires to build bonds between differentially positioned groups. “Connecting” means building “a coordinated, curated, or articulated form of exchange that emphasizes the morally responsive connections and forms of kinship bond between communities engaged with policy, practice, and research on girls’ education, gender equality, and women’s rights.” 26 It is not yet clear whether the what-connects framing will have traction as a policy idea or field of practice. It will require critical thinking, use of evidence, and a simultaneous focus on changing the systems of oppression and exclusion that characterize local and global communities.

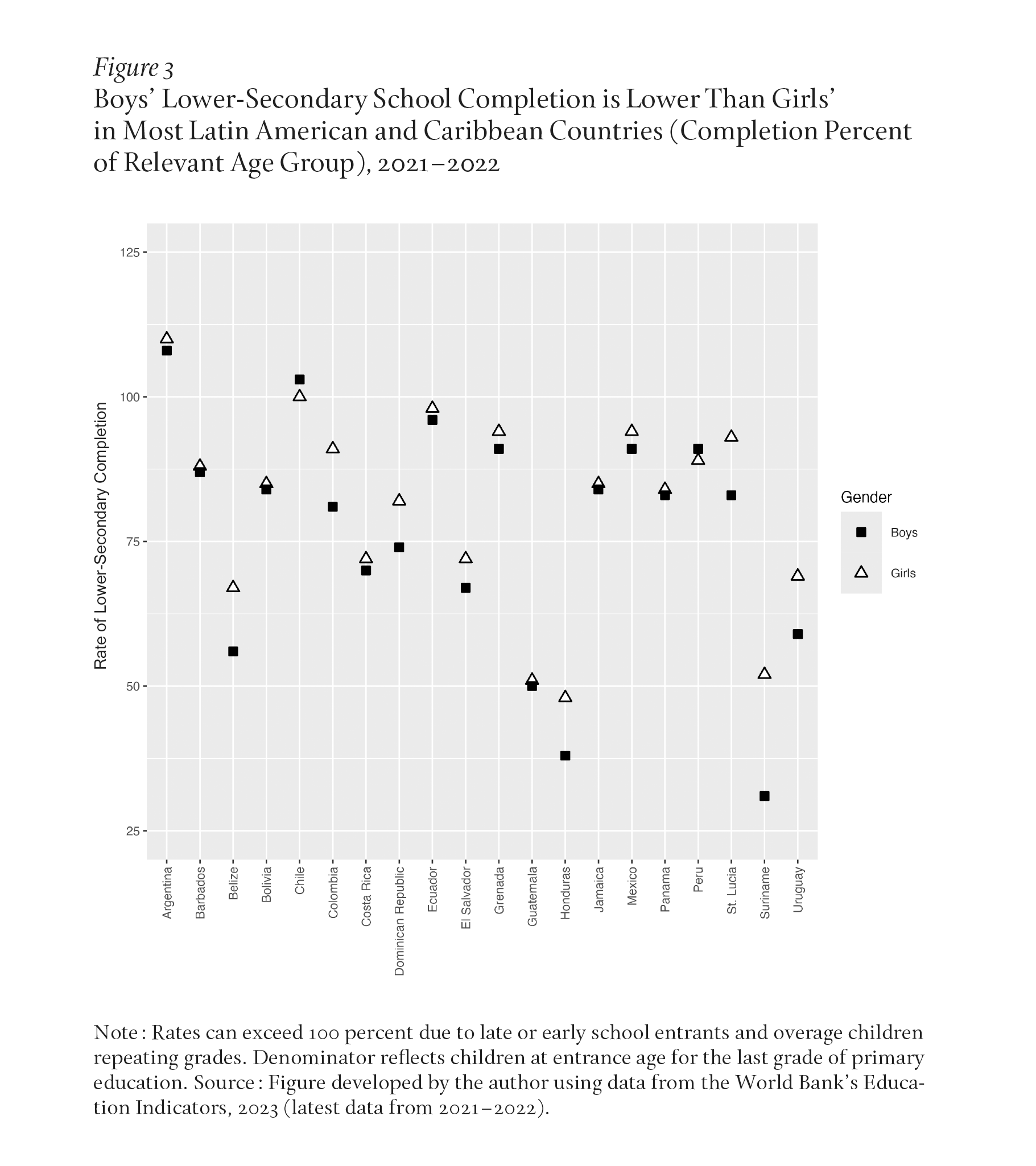

In Latin America, the need for a what-connects approach to gender and education is palpable. Framed differently, one might conclude that gender is not an important educational issue because countries have either reached gender parity or have a female advantage. An analysis of gender and education in Latin America allows us to ask important questions and restate a set of principles.

First, gender is not synonymous with girls and women, as it often appears in policy documents and statements about education in developing-country contexts. Gender refers to the socially constructed roles, behaviors, expressions, and identities of girls, women, boys, men, and nonbinary or gender diverse people. It is often categorized as male, female, or nonbinary. Gender is social and cultural. However, it is often used incorrectly as a synonym for the biological sex a person is assigned at birth. A simple google search for “gender and education” will result in scores of hits that immediately begin by discussing girls’ underrepresentation in education systems, and the need to promote girls’ education as a strategy to advance gender equality.

But in Latin America (and several other world regions or countries including North America, Australia, and the United Kingdom), girls outnumber and outperform boys. Policy experts in Latin America have called this a reverse gender gap. In Latin America, boys and young men are more likely to drop out of secondary and tertiary education. They have lower rates of enrollment and completion of secondary education than girls, starting at the lower-secondary level. At the university or tertiary level, men have lower enrollment rates than women in all countries of Latin America and the Caribbean. These patterns are referred to as one of the greatest gender-related challenges in the region. 27 Studies identify a number of factors at play, including boys prematurely joining the labor market in low-skill jobs, gender norms of masculinity that diminish the importance of education and emphasize that of male physical labor, and features of schooling that lead to low interest or low aspirations.

In addition to a reverse gender gap, overall participation rates in secondary education remain low, despite an increase in the availability of secondary schools over the past two decades. Both boys and girls might initially enroll in lower or upper high school, but a very small percentage go on to complete twelve years of schooling, as illustrated in Figure 3. Dropout from secondary school is a major challenge, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Estimates suggest that the likelihood of completing secondary school in Latin America prior to the pandemic was 52 percent, and just 32 percent post pandemic. 28 Latin America had the longest school closures of any region in the world during the pandemic, with schools remaining closed for one and a half years, on average.

In addition to (and as a partial explanation for) the very low secondary-school completion rates, Latin America has one of the highest rates of adolescent pregnancy globally. It is the only region of the world where adolescent pregnancies have not decreased. It also has comparatively high rates of early union or marriage (prior to age eighteen). One-in-four young women in Latin America were married before their eighteenth birthday. In rural areas, these rates tend to be higher, and age younger, with one-in-ten girls marrying before the age of fifteen. There are a number of hypotheses for why this is the case, including 1) conservative mobilization to block gender and sexuality education, 2) regressive policies and abortion bans, and 3) social norms that restrict adolescent dating and sexuality and thereby push girls to have clandestine relationships or elope with their boyfriends.

The experience in Latin America defies the underlying assumption that if more children and youth have access to secondary education, more girls will enroll, and society will reap the benefits of girls’ education. It also illustrates that a gender-girls’ perspective is problematic because addressing the reasons why girls are out of school will not automatically improve boys’ situation as well. While access to secondary schooling has expanded, dropout rates are soaring. The reasons for dropout are different for boys and girls, but a sense of disillusionment with the education system is widespread. It is only through the kinds of questions and research methods that connect a what-works with a what-matters perspective that we can gain a deeper understanding of what is happening in Latin America and what is needed to support systematic change.

Over the last two decades, I have been engaged in research partnerships that explore questions related to how education can empower youth and challenge harmful gender norms in Latin America. Much of my research has been in Honduras, a country that has faced challenges typical of many countries in the region, including stagnant and uneven economic growth, natural disasters, political corruption and instability, increased violence due to narco-trafficking and gang activity, and mass migration to the United States. Together with colleagues and students at the University of California, Berkeley, the Honduran National Pedagogical University, Wellesley College, and the Honduran civil society organization Asociación Bayan, I have conducted research to better understand how education can empower youth and what “quality” education means in rural contexts. We have also explored the process by which girls decide to enter into early marriage, and the extent to which they demonstrate agency in that process. And we have examined, using both qualitative and quantitative methods, why youth discontinue their studies, and the intersections between dropout and gender.

Beginning in 2008, our research team began a longitudinal study of rural Honduran youth. At the time of first data collection, research participants were just completing primary school (approximately twelve years old). We stayed in touch with these youth and conducted additional rounds of surveys and interviews one year, two years, and, in 2016, eight years later when they were young adults (approximately twenty years old). The longitudinal, mixed methods nature of our study allowed us to examine intersections between schooling, child marriage, and adolescent pregnancy, as well as decisions around school dropout. We found that household income in early adolescence predicts school discontinuation, early union, and early childbearing. Additionally, most girls had already discontinued their studies when they entered a union and/or became mothers (meaning that they did not drop out of school because they were pregnant or wanted to get married). The most common reasons for leaving school included a lack of financial resources and no longer wanting to be a student. Largely due to social norms and the responsibilities of childcare, only a small percentage of girls returned to school after becoming wives or mothers.

We also explored the data from surveys and in-depth qualitative interviews to determine the pervasiveness of traditional views on gender roles among Honduran youth, and how these norms are related to control of girls’ sexuality in rural areas of Honduras. We examined how these social norms converge with the biological, psychosocial, and cognitive changes experienced during adolescence and the social contexts in which adolescent girls’ lives are embedded. In Honduras and other countries in the region, formal or legal marriage is rare in rural communities; as such, we employ the term “early union.” While not legally binding, these relationships carry the cultural significance of marriage in rural communities, and individuals use the terms husband/wife and the verbs casarse (to marry) and unirse (to join together/unite) to characterize their roles and relationships.

Our interviews suggested that parents’ desire to control girls’ sexuality ironically can backfire and influence girls’ decision-making to enter a union. In particular, the belief that sex should only occur within the context of a union encourages girls to see marriage as the only way to be involved in a romantic relationship. While girls are expected to adhere to these expectations and live in restrictive environments that control their mobility, their socialization opportunities, and their sexuality, girls are simultaneously going through normal developmental processes of adolescence. More specifically, they are developing a greater sense of autonomy, experiencing an emerging interest in intimacy and sexual relationships, undergoing the physical and emotional changes that come with puberty, and developing sophisticated cognitive abilities connected to decision-making processes. The excessive protectiveness and the parental control of sexuality experienced by girls in rural areas of Honduras clash with the natural developmental changes that occur during adolescence, which ultimately influences their decision to enter early unions. Drawing upon these findings, we provide a rationale for why educational initiatives that explain and normalize the changes that occur during adolescence (particularly around attraction and intimacy) as well as challenge social norms and constructs that promote gender inequality should be a central component of child marriage education programming for adolescents, parents, and community members.

In addition to better understanding how early unions and pregnancy intersect with secondary school dropout, we also wanted to examine other issues related to gender. We were interested in why students were “no longer interested” in being students, despite having access to secondary school. Through statistical analysis and rich qualitative interview data, we discovered that dropout is patterned by schooling structures, such that more dropout occurs, for all adolescents, at the standard transition points (to lower-secondary school, to upper-secondary school, to tertiary school). We also observed that for both males and females, once a student drops out, they rarely return to school. Drawing from the capability approach, we used the concept of “conversion factors” to help explain our findings. Conversion factors refer to individuals’ ability to convert resources into “valued functionings,” to whether youth can reap the benefits of secondary education. We illustrate that, in the context of where these youth live, they have scarce opportunities to convert the resource of a high school diploma into a valued functioning, including a job. The youth we interviewed questioned whether education would lead to any change in their life trajectories, particularly in a context in which their future roles as wives and mothers (for girls) and breadwinners via agricultural or other manual labor (for boys) was all but certain. In particular, our findings regarding male school discontinuation provide further evidence that boys are distrustful of schooling as a guarantee of future employment and social mobility. The experience of Latin America shows that simply increasing the supply of schooling is not enough to address gender inequality in society.

Gender-transformative education has emerged as a way to frame how, in order to tap its transformative potential, education must go beyond closing gender gaps. Gender-transformative education is now a shared orientation among United Nations agencies, including UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) and UNGEI (United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative), as well as leading nongovernmental actors such as Plan International, the Population Council, CARE, and Girls not Brides. Gender-transformative education calls for “nothing less than a fundamental reset of how we approach education.” 29 A recent joint statement by Plan International, UNGEI, and UNICEF posits that education has transformative potential, but to unlock this potential, change is needed in the way we educate. This approach recognizes that gender norms are extremely challenging to address because they are entrenched in every aspect of society, and education systems reflect and can reinforce these norms. And these norms are also harmful for men and boys. Dismantling patriarchy requires a transformative approach, one that recognizes how gender discrimination often intersects with discrimination based on poverty, race, class, ethnicity, caste, language, migration or displacement status, HIV status, disability, gender identity, and sexual orientation. Gender-transformative education actively seeks ways to address inequalities and reduce harmful gender norms and practices. As the joint statement explains:

Gender transformative education is about inclusive, equitable, quality education (SDG 4, particularly target 4.7) and nurturing an environment for gender justice for children, adolescents and young people in all their diversity (SDG 5, particularly target 5.1). Gender Transformative Education would remove barriers to education and boost progress towards important social shifts, such as the reduction of gender-based violence and early marriage, the promotion of gender equality, and women’s and girls’ leadership and decision-making roles. . . . Gender transformative education completely transforms education systems by uprooting inequalities. Gender transformative education seeks to utilize all parts of an education system–from policies to pedagogies to community engagement–to transform stereotypes, attitudes, norms and practices by challenging power relations, rethinking gender norms and binaries, and raising critical consciousness about the root causes of inequality and systems of oppression. 30

This is the most ambitious approach to gender and education that has been articulated to date. It goes beyond “gender sensitive” and “gender responsive” approaches that do not call for change in the social structures that cause discrimination and inequality. A gender-transformative approach recognizes that education alone cannot shift gender norms and power relations, but that addressing the social structures that cause inequality and discrimination is needed. To do so, a number of actions are identified as essential, including transforming policies and political engagement, pedagogy and the curriculum, the school environment, participation of children and young people, community leadership, stakeholder engagement, and evidence-generation. This approach connects efforts to address gender inequality in education with the broader quest for social justice. To use Unterhalter’s framing, it connects what works with what matters. 31

While ambitious, gender-transformative education is attainable. A recent report on gender-transformative programs to address child, early, and forced marriage and unions in Latin America and the Caribbean includes case studies of five promising practices from the region. 32 These five practices were identified through a scoping survey about encouraging approaches in the region, to which one hundred five organizations responded. The cases profiled include in-school gender-transformative sexuality education programs and what is known as safe-space approaches (which are outside of formal school settings). One of the programs profiled in the report, Holistic Education for Youth (HEY!), emerged from our research-practice partnership in Honduras. Despite a resurgence in opposition to comprehensive sexuality education and gender-transformative approaches in the region, the HEY! program offers a glimmer of hope that gender-transformative education is possible. 33

HEY! works in tandem with the Sistema de Aprendizaje Tutorial (SAT) program, an innovative approach to lower- and upper-secondary school that operates in approximately one hundred twenty rural Honduran communities. Developed in Colombia by FUNDAEC (the Foundation for the Application and Teaching of Sciences), SAT was created in the early 1980s to promote development in the most disadvantaged rural areas of Colombia. In 1996, SAT began as a pilot program in Honduras, and was formally approved by the Honduran government as a formal education program (granting lower- and upper-secondary school degrees) in 2003. SAT has received several accolades, including inclusion as a “global solution” in the United Nations’ Generation Unlimited initiative for youth. The Brookings Institution, through its Millions Learning initiative, also included SAT as an example of innovative, quality education. 34 In Honduras, students study in the SAT program for six years, spanning grades 7–12 (lower- and upper-secondary school). In 2016, we launched the HEY! program to enhance the already extensive focus on gender inequality present in the SAT curriculum, providing additional lessons and a podcast for parents that explicitly address the causes and consequences of early marriage and union in Honduras, as well as content about sexual and reproductive health.

The additional content provided by HEY!, coupled with the existing SAT curriculum, make it a promising model of gender-transformative public education for other regions, which we document in our research. 35 The conceptual framework of SAT revolves around a few core beliefs: 1) the oneness of humanity, 2) that justice is integral to achieving human progress and is a capacity that must be developed in individuals, communities, and institutions, 3) that gender equality is essential to achieving human prosperity, 4) that knowledge has the power to raise humanity from its present condition, and 5) that social change–the transformation of human society–will not take place unless individuals and social structures evolve to reflect the aforementioned principles. Coupled with these core principles are a number of transformative features of the SAT program that contribute to increased awareness of the need for gender equality in students, and to a shift in how they think about gender relations in their everyday lives. In the SAT program, gender equality is not a one-off lesson, but is rather woven across the curriculum; gender is linked with the larger concept of justice; students engage in reflection, dialogue, and debate; teachers are given the opportunity to reflect critically on their understanding of gender in professional development sessions; and the curriculum emphasizes that gender transformation requires change among individuals and in social structures such as the family.

One example of many from the curriculum helps illustrate how this happens in practice. “Properties,” which is typically the first curricular unit studied by SAT students when they are in seventh grade, aims to “help young people advance in the capabilities that will enable them to describe the world they experience with increasing clarity.” 36 In a lesson on truthfulness, presented as an essential quality or “property” of a human being, the following is provided to students for their reflection and discussion:

There is more to truthfulness than not telling lies. We should, of course, always tell the truth as we know and understand it. But what benefit will come from such truthfulness if what we think to be the truth is, actually, false? Another aspect of truthfulness, then, is the intention and the will to seek the truth with an open mind. For many centuries people believed that the Earth was flat. Later it was proved that they were mistaken. Their belief did not agree with reality; it was an error. If the intention and the will to seek the truth had not existed, humanity would still be thinking that the Earth is flat.

Can you think of a few erroneous ideas that humanity needs to reject today? What about the idea that some race is superior or inferior to another? That men are superior to women? That it is acceptable for one group of people to oppress another group? That it is acceptable for a few to possess extreme wealth while many suffer from hunger? 37

The lesson is presented in such a way as to challenge SAT students to identify whether the assumption that men are superior to women is in fact a belief that they have been exposed to; whether they accept that such a belief is erroneous, and why; and where gender inequality is linked to other forms of oppression and injustice. Rather than simply list, in the various SAT books (or even an isolated book that might focus solely on gender), why men and women are equal, what the problems facing most women are, and what to do about it, SAT units instead require students to come back to these themes time and again, from different angles, repeatedly challenging students to reflect on what equality looks like in practice in their local reality, and what they can do to promote it. Additionally, SAT’s “tutorial” pedagogy fosters an environment of healthy discussion and dialogue among members of the class. 38

Through our research, we have documented how HEY! and SAT use culturally grounded, context-specific scenarios and ask questions at the beginning, middle, and end of each lesson to promote group discussion and invite students to analyze and reflect upon their individual and social realities as well as their roles in promoting social change. We have demonstrated that students who study in SAT also have higher academic achievement in standardized tests in Spanish and mathematics than a statistically equivalent set of peers who study in traditional secondary schools. In sum, our research, spanning two decades, documents innovative features of SAT, including its linkages to building trust, improving civic responsibility, empowering girls and women, and preventing early pregnancy and union. Taken together, these studies provide ample evidence that gender-transformative education is not a pipe dream.

Despite its potential, even gender-transformative education is not a panacea. Every school year, students in SAT drop out to migrate to the United States. Girls struggle to envision a future in which they have opportunities to work outside of their home, and they form unions with their boyfriends. Boys, not certain that their education will lead to improved employment prospects, prematurely begin working in manual labor. Even at its very best, an education system cannot change society without accompanying changes in other sectors, including the economy and politics. Education is potentially the most important long-term strategy to raise up individual and collective capacity for social change. Too often, quick fixes are touted as solutions to problems, solutions that might be important in the short term but are unlikely to result in deep and lasting change. Providing scholarships for girls is one example. While financial support might bring more girls into the education system, it does not address why they are underrepresented in the first place.

For genuine change to unfold, a different vision is needed, one not focused solely on equal numbers of boys and girls attending and graduating from schools. This vision draws on a notion of prosperity and feminism consistent with the work of the late bell hooks (and is also consistent with the capabilities approach). 39 This clear but transformative vision of feminism and human flourishing, articulated more than twenty years ago by hooks, should remain at the heart of our efforts to promote gender-transformative education around the globe:

Imagine living in a world where there is no domination, where females and males are not alike or even always equal, but where a vision of mutuality is the ethos shaping our interaction. Imagine living in a world where we can all be who we are, a world of peace and possibility. Feminist revolution alone will not create such a world; we need to end racism, class elitism, imperialism. But it will make it possible to be fully actualized . . . able to create beloved community, to live together, realizing our dreams of freedom and justice. 40

- 1 Elaine Unterhalter, “An Answer to Everything? Four Framings of Girls’ Schooling and Gender Equality in Education,” Comparative Education 59 (2) (2023): 145–168.

- 2 Boris Johnson as cited in ibid., 145; and Educate Girls, “ Ten Celebrities Campaigning for Girls’ Education ” (accessed August 28, 2023).

- 3 ClimateLinks, “ Why Is Girls’ Education Important for Climate Action? ” (accessed August 28, 2023); and Vanessa Nakate, “ Vanessa Nakate on How Girls’ Education Can Help Solve the Climate Crisis ,” The Economist , March 8, 2022.

- 4 Nelly P. Stromquist, “Romancing the State: Gender and Power in Education,” Comparative Education Review 39 (4) (1995): 423–454.

- 5 Lant Pritchett, The Rebirth of Education: Schooling Ain’t Learning (Center for Global Development, 2013).

- 6 See United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “ 4. Quality Education ” (accessed September 18, 2024).

- 7 Rosie Peppin Vaughan, “Gender Equality and Education in the Sustainable Development Goals,” background paper prepared for the 2016 Global Education Monitoring Report Education for People and Planet: Creating Sustainable Futures for All (UNESCO, 2016).

- 8 UNICEF, “ Education ,” June 2022 (accessed March 6, 2024).

- 9 UNESCO, Leave No Child Behind: Global Report on Boys’ Disengagement from Education (UNESCO, 2022).

- 10 Stephanie R. Psaki, Katharine J. McCarthy, and Barbara S. Mensch, “Measuring Gender Equality in Education: Lessons from Trends in 43 Countries,” Population and Development Review 44 (1) (2018): 117–142.

- 11 World Bank Group, “ Education Statistics–All Indicators ,” 2023.

- 13 Psaki, McCarthy, and Mensch, “Measuring Gender Equality in Education,” 119.

- 14 See United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “4. Quality Education.”

- 15 United Nations Commission on Population and Development, “ Population, Education, and Sustainable Development: Ten Key Messages .”

- 16 Plan International, “ Gender Transformative Education: Reimagining Education for a More Just and Inclusive World ” (accessed August 28, 2023).

- 17 Unterhalter, “An Answer to Everything,” 148.

- 18 See, for example, Erica K. Chuang, Barbara S. Mensch, Stephanie R. Psaki, et al., “PROTOCOL: Policies and Interventions to Remove Gender-Related Barriers to Girls’ School Participation and Learning in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review of the Evidence,” Campbell Systematic Review 15 (3) (2019): e1047.

- 19 Unterhalter, “An Answer to Everything.”

- 20 Kathryn Moeller, The Girl Effect: Capitalism, Feminism, and the Corporate Politics of Development (University of California Press, 2018).

- 21 Unterhalter, “An Answer to Everything,” 155.

- 22 See, for example, Ana Aguilera, Sarah Green, Margaret E. Greene, Chimaraoke Izugbara, and Erin Murphy-Graham, “Multidimensional Measures Are Key to Understanding Child, Early, and Forced Marriages and Unions,” Journal of Adolescent Health 70 (2) (2022): 345–346.

- 23 Erin Murphy-Graham, Opening Minds, Improving Lives: Education and Women’s Empowerment in Honduras (Vanderbilt University Press, 2012).

- 24 Melanie Walker, “A Capital or Capabilities Education Narrative in a World of Staggering Inequalities?” International Journal of Educational Development 32 (3) (2012): 384–393.

- 25 Joan D. Dejaeghere, “Reconceptualizing Educational Capabilities: A Relational Capability Theory for Redressing Inequalities,” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 21 (1) (2020): 17–35.

- 26 Unterhalter, “An Answer to Everything,” 157.

- 27 Ursula Casabonne and Daniela Maquera, Reducing School Dropout and Helping Boys at Risk (World Bank Group, 2023).

- 28 Nora Lustig, Guido Neidhöfer, and Mariano Tomassi, “ Back to the 1960s? Education May Be Latin America’s Most Lasting Scar from COVID-19 ,” Americas Quarterly , December 3, 2020 (accessed August 28, 2023).

- 29 Plan International, “Gender Transformative Education.”

- 31 Unterhalter, “An Answer to Everything.”

- 32 Child, Early and Forced Marriage and Unions (CEFMU) and Sexuality Working Group, Tackling the Taboo in Latin America and the Caribbean: Sexuality and Gender-Transformative Programmes to Address Child, Early and Forced Marriage and Unions–Report and Case Studies (Child, Early and Forced Marriage and Unions and Sexuality Working Group, 2022).

- 33 Flávia Biroli and Mariana Caminotti, “The Conservative Backlash Against Gender in Latin America,” Politics & Gender 16 (1) (2020).

- 34 Christina Kwauk and Jenny Perlman Robinson, Sistema de Aprendizaje Tutorial: Redefining Rural Secondary Education in Latin America (Center for Universal Education at Brookings, 2016.

- 35 Patrick J. McEwan, Erin Murphy-Graham, David Torres Irribarra, et al., “Improving Middle School Quality in Poor Countries: Evidence from the Honduran Sistema de Aprendizaje Tutorial,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 37 (1) (2015): 113–137; Catherine A. Honeyman, “Social Responsibility and Community Development: Lessons from the Sistema de Aprendizaje Tutorial in Honduras,” International Journal of Educational Development 30 (6) (2010): 599–613; Erin Murphy-Graham and Joseph Lample, “Learning to Trust: Examining the Connections Between Trust and Capabilities Friendly Pedagogy through Case Studies from Honduras and Uganda,” International Journal of Educational Development 36 (2014): 51–62; Erin Murphy-Graham, Alison K. Cohen, and Diana PachecoMontoya, “School Dropout, Child Marriage, and Early Pregnancy Among Adolescent Girls in Rural Honduras,” Comparative Education Review 64 (4) (2020): 703–724; Erin Murphy-Graham and Graciela Leal, “Child Marriage, Agency, and Schooling in Rural Honduras,” Comparative Education Review 59 (1) (2015): 24–49; Alice Y. Taylor, Erin Murphy-Graham, Julia Van Horn, et al., “Child Marriages and Unions in Latin America: Understanding the Roles of Agency and Social Norms,” Journal of Adolescent Health 64 (4) (2019): S45–S51; Diana Pacheco-Montoya, Erin Murphy-Graham, Enrique Eduardo Valencia López, and Alison K. Cohen, “Gender Norms, Control Over Girls’ Sexuality, and Child Marriage: A Honduran Case Study,” Journal of Adolescent Health 70 (3) (2022): S22–S27; and Diana Pacheco-Montoya and Erin Murphy-Graham, “Fostering Critical Thinking as a Life Skill to Prevent Child Marriage in Honduras: The Case of Holistic Education for Youth (HEY!),” in Life Skills Education for Youth: Critical Perspectives , ed. Joan DeJaeghere and Erin Murphy-Graham (Springer Nature, 2021).

- 36 FUNDAEC, “Properties” (curricular unit), 2005, Cali, Colombia.

- 38 Another example from the curriculum is a book students study during their first year (seventh grade) called Systems and Processes. Among its goals are for students to “act in the world with efficacy and promote constructive change” by “introducing words and concepts needed to speak about the many processes that continually unfold in the world and the systems in which they occur.” In the various lessons of the text, the human body is offered as an analogy for a well-functioning society, and the notion that even as the integrity of the body and its various subsystems (circulatory system, digestive system, and so on) are interdependent, “so too the health and well-being of society as a whole and that of the individuals within it that depend on one another.” In introducing the concept of a “system” so early in their studies, students can build the capacity to conceptualize and take actions toward the systemic transformations that are needed and consistent with a gender-transformative approach. See FUNDAEC, Systems and Processes (FUNDAEC, 2005), vii–viii.

- 39 For an overview of the life and literary work of bell hooks, see Poetry Foundation, “ bell hooks, 1952–2021 .”

- 40 bell hooks, Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics (South End Press, 2000), x.

How our education system undermines gender equity

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, and why culture change—not policy—may be the solution, joseph cimpian jc joseph cimpian associate professor of economics and education policy - new york university.

April 23, 2018

There are well-documented achievement and opportunity gaps by income and race/ethnicity. K-12 accountability policies often have a stated goal of reducing or eliminating those gaps, though with questionable effectiveness . Those same accountability policies require reporting academic proficiency by gender, but there are no explicit goals of reducing gender gaps and no “hard accountability” sanctions tied to gender-subgroup performance. We could ask, “Should gender be included more strongly in accountability policies?”

In this post, I’ll explain why I don’t think accountability policy interventions would produce real gender equity in the current system—a system that largely relies on existing state standardized tests of math and English language arts to gauge equity. I’ll argue that although much of the recent research on gender equity from kindergarten through postgraduate education uses math or STEM parity as a measure of equity, the overall picture related to gender equity is of an education system that devalues young women’s contributions and underestimates young women’s intellectual abilities more broadly.

In a sense, math and STEM outcomes simply afford insights into a deeper, more systemic problem. In order to improve access and equity across gender lines from kindergarten through the workforce, we need considerably more social-questioning and self-assessment of biases about women’s abilities.

As soon as girls enter school, they are underestimated

For over a decade now, I have studied gender achievement with my colleague Sarah Lubienski, a professor of math education at Indiana University-Bloomington. In a series of studies using data from both the 1998-99 and 2010-11 kindergarten cohorts of the nationally representative Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, we found that no average gender gap in math test scores existed when boys and girls entered kindergarten, but a gap of nearly 0.25 standard deviations developed in favor of the boys by around second or third grade.

For comparison purposes, the growth of the black-white math test score gap was virtually identical to the growth in the gender gap. Unlike levels and growth in race-based gaps, though, which have been largely attributed to a combination of differences in the schools attended by black and white students and to socio-economic differences, boys and girls for the most part attend the same schools and come from families of similar socio-economic status. This suggests that something may be occurring within schools that contributes to an advantage for boys in math.

Exploring deeper, we found that the beliefs that teachers have about student ability might contribute significantly to the gap. When faced with a boy and a girl of the same race and socio-economic status who performed equally well on math tests and whom the teacher rated equally well in behaving and engaging with school, the teacher rated the boy as more mathematically able —an alarming pattern that replicated in a separate data set collected over a decade later .

Another way of thinking of this is that in order for a girl to be rated as mathematically capable as her male classmate, she not only needed to perform as well as him on a psychometrically rigorous external test, but also be seen as working harder than him. Subsequent matching and instrumental variables analyses suggested that teachers’ underrating of girls from kindergarten through third grade accounts for about half of the gender achievement gap growth in math. In other words, if teachers didn’t think their female students were less capable, the gender gap in math might be substantially smaller.

An interaction that Sarah and I had with a teacher drove home the importance and real-world relevance of these results. About five years ago, while Sarah and I were faculty at the University of Illinois, we gathered a small group of elementary teachers together to help us think through these findings and how we could intervene on the notion that girls were innately less capable than boys. One of the teachers pulled a stack of papers out of her tote bag, and spreading them on the conference table, said, “Now, I don’t even understand why you’re looking at girls’ math achievement. These are my students’ standardized test scores, and there are absolutely no gender differences. See, the girls can do just as well as the boys if they work hard enough.” Then, without anyone reacting, it was as if a light bulb went on. She gasped and continued, “Oh my gosh, I just did exactly what you said teachers are doing,” which is attributing girls’ success in math to hard work while attributing boys’ success to innate ability. She concluded, “I see now why you’re studying this.”

Although this teacher did ultimately recognize her gender-based attribution, there are (at least) three important points worth noting. First, her default assumption was that girls needed to work harder in order to achieve comparably to boys in math, and this reflects an all-too-common pattern among elementary school teachers, across at least the past couple decades and in other cultural contexts . Second, it is not obvious how to get teachers to change that default assumption. Third, the evidence that she brought to the table was state standardized test scores, and these types of tests can reveal different (often null or smaller) gender achievement gaps than other measures.

On this last point, state standardized tests consistently show small or no differences between boys and girls in math achievement, which contrasts with somewhat larger gaps on NAEP and PISA , as well as with gaps at the top of the distribution on the ECLS , SAT Mathematics assessment, and the American Mathematics Competition . The reasons for these discrepancies are not entirely clear, but what is clear is that there is no reason to expect that “hardening” the role of gender in accountability policies that use existing state tests and current benchmarks will change the current state of gender gaps. Policymakers might consider implementing test measures similar to those where gaps have been noted and placing more emphasis on gains throughout the achievement distribution. However, I doubt that a more nuanced policy for assessing math gains would address the underlying problem of the year-after-year underestimation of girls’ abilities and various signals and beliefs that buttress boys’ confidence and devalue girls, all of which cumulatively contributes to any measured gaps.

More obstacles await women in higher education and beyond

Looking beyond K-12 education, there is mounting evidence at the college and postgraduate levels that cultural differences between academic disciplines may be driving women away from STEM fields, as well as away from some non-STEM fields (e.g., criminal justice, philosophy, and economics). In fact, although research and policy discussions often dichotomize academic fields and occupations as “STEM” and “non-STEM,” the emerging research on gender discrimination in higher education finds that the factors that drive women away from some fields cut across the STEM/non-STEM divide. Thus, while gender representation disparities between STEM and non-STEM fields may help draw attention to gender representation more broadly, reifying the STEM/non-STEM distinction and focusing on math may be counterproductive to understanding the underlying reasons for gender representation gaps across academic disciplines.

In a recent study , my colleagues and I examined how perceptions on college majors relate to who is entering those majors. We found that the dominant factor predicting the gender of college-major entrants is the degree of perceived discrimination against women. To reach this conclusion, we used two sources of data. First, we created and administered surveys to gather perceptions on how much math is required for a major, how much science is required, how creative a field is, how lucrative careers are in a field, how helpful the field is to society, and how difficult it is for a woman to succeed in the field. After creating factor scales on each of the six dimensions for each major, we mapped those ratings onto the second data source, the Education Longitudinal Study, which contains several prior achievement, demographic, and attitudinal measures on which we matched young men and women attending four-year colleges.

Among this nationally representative sample, we found that the degree to which a field was perceived to be math- or science-intensive had very little relation to student gender. However, fields that were perceived to discriminate against women were strongly predictive of the gender of the students in the field, whether or not we accounted for the other five traits of the college majors. In short, women are less likely to enter fields where they expect to encounter discrimination.

And what happens if a woman perseveres in obtaining a college degree in a field where she encounters discrimination and underestimation and wants to pursue a postgraduate degree in that field, and maybe eventually work in academia? The literature suggests additional obstacles await her. These obstacles may take the form of those in the field thinking she’s not brilliant like her male peers in graduate school, having her looks discussed on online job boards when she’s job-hunting, performing more service work if she becomes university faculty, and getting less credit for co-authored publications in some disciplines when she goes up for tenure.

Each of the examples here and throughout this post reflects a similar problem—education systems (and society) unjustifiably and systematically view women as less intellectually capable.

Societal changes are necessary

My argument that policy probably isn’t the solution is not intended to undercut the importance of affirmative action and grievance policies that have helped many individuals take appropriate legal recourse. Rather, I am arguing that those policies are certainly not enough, and that the typical K-12 policy mechanisms will likely have no real effect in improving equity for girls.

The obstacles that women face are largely societal and cultural. They act against women from the time they enter kindergarten—instilling in very young girls a belief they are less innately talented than their male peers—and persist into their work lives. Educational institutions—with undoubtedly many well-intentioned educators—are themselves complicit in reinforcing the hurdles. In order to dismantle these barriers, we likely need educators at all levels of education to examine their own biases and stereotypes.

Related Content

Michael Hansen, Diana Quintero

July 10, 2018

Jaymes Pyne

July 30, 2020

Tom Loveless

March 24, 2015

Education Access & Equity Higher Education K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Lucy Sorensen, Stephen Holt, Andrea M. Headley

November 19, 2024

Melissa Arnold Lyon

November 18, 2024

Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, Douglas R. Knecht

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Race and gender intersectionality and education.

- Venus E. Evans-Winters Venus E. Evans-Winters Illinois State University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1345

- Published online: 23 February 2021

When recognizing the cultural political agency of Black women and girls from diverse racial and ethnic, gender, sexual, and socioeconomic backgrounds and geographical locations, it is argued that intersectionality is a contributing factor in the mitigation of educational inequality. Intersectionality as an analytical framework helps education researchers, policymakers, and practitioners better understand how race and gender intersect to derive varying amounts of penalty and privilege. Race, class, and gender are emblematic of the three systems of oppression that most profoundly shape Black girls at the personal, community, and social structural levels of institutions. These three systems interlock to penalize some students in schools while privileging other students. The intent of theoretically framing and analyzing educational problems and issues from an intersectional perspective is to better comprehend how race and gender overlap to shape (a) educational policy and discourse, (b) relationships in schools, and (c) students’ identities and experiences in educational contexts. With Black girls at the center of analysis, educational theorists and activists may be able to better understand how politics of domination are organized along other axes such as ethnicity, language, sexuality, age, citizenship status, and religion within and across school sites. Intersectionality as a theoretical framework is informed by a variety of standpoint theories and emancipatory projects, including Afrocentrism, Black feminism and womanism, critical race theory, queer theory, radical Marxism, critical pedagogy, and grassroots’ organizing efforts led by Black, Indigenous, and other women of color throughout US history and across the diaspora.

- intersectionality

- Black girls

- girls of color

- Black feminism

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 21 November 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.41]

- 185.80.151.41

Character limit 500 /500

Discourses of Gender Inequality in Education

- First Online: 18 May 2022

Cite this chapter

- Joseph Zajda 36

Part of the book series: Globalisation, Comparative Education and Policy Research ((GCEP,volume 31))

672 Accesses

1 Citations

Adopting a feminist critical theory perspective, which tends to focus on economic, cultural, and social inequalities, affecting women, we can examine gender inequality in education globally, as yet another enduring dimension of social stratification and division of power, domination, and control. In many ways, it reflects the existing and entrenched ubiquitous patriarchy. Greater gender equality, according to OECD (2019a, b) is not just a ‘moral imperative, but is also key to the creation of stronger, more sustainable and more inclusive economies’. The OECD (2019a, b) Gender equality document has placed gender equality at the top of its policy agenda. The OECD suggests policy and strategies for combating gender inequalities in all spheres of social relations. Creating conditions and opportunities for gender equality is central to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. OECD’s work in support of the 2030 Agenda includes the updating and further development of the Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI):

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Aikens, M., et al. (2017). Race and gender differences in undergraduate research mentoring structures and research outcomes . Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313818166_Race_and_Gender_Differences_in_Un

Alan, S., Ertac, S., & Mumcu, I. (2018). Gender stereotypes in the classroom and effects on achievement. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 100 (5), 876–890.

Article Google Scholar

Bigler, R., Hayes, A., & Hamilton, V. (2013). The role of schools in the early socialization of gender differences. In R. E. Tremblay, M. Boivin, & R. Peters (Eds.), Encyclopedia on early childhood development (online). Retrieved from https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/gender-early-socialization/according-experts/role-s

Blackmore, J. (2015). Gender inequality and education: changing local/global relations in a ‘post colonial’ world and the implications for feminist research. In J. Zajda (Ed.), Second international handbook of globalisation, education and policy research . Springer.

Google Scholar

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design . Harvard University Press.

Chavous, T. M., Rivas-Drake, D., Smalls, C., Griffin, T., & Cogburn, C. (2008). Gender matters, too: The influences of school racial discrimination and racial identity on academic engagement outcomes among African American adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 44 (3), 637–654. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.637

Cvencek, D., Meltzoff, A., & Greenwald, A. (2011). Math–gender stereotypes in elementary school children. Child Development, 82 (3), 766–779.

DeLaney, E. (2018). Ethnic-racial identity and academic achievement: Examining mental health and racial discrimination as moderators among Black college students . M. Science thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University. Retrieved from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6758&context=etd

Dervin, F., & Zajda, J. (2022). Governance in education: Diversity and effectiveness . UNESCO.

Dorius, S. (2006). Rates, shares, gaps and Ginis: Are women catching up with men worldwide . Draft report. Pennsylvania State University.

Global education monitoring report. (2020). A new generation: 25 years of efforts for gender equality in education . United Nations.

Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102 (1), 4–27.

Hsieh, T.-y., Simpkins, S., & Eccles, J. (2021). Gender by racial/ethnic intersectionality in the patterns of adolescents’ math motivation and their math achievement and engagement. Contemporary Educational Psychology , 66 (1). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351445954_Gender_by_RacialEthnic_Intersectionality_in_the_Patterns_of_Adolescents'_Math_Motivation_and_Their_Math_Achievement_and

Human Development Report. (2020). Retrieved from https://hdr.undp.org/en/2020-report

Juan, M., Syed, M., & Azmitia, M. (2016). Intersectionality of race/ethnicity and gender among women of color and White women. Identity, 16 (4), 225–238.

Laursen, S., & Austin, A. (2021). Building gender equity in the academy: Institutional strategies for change . Johns Hopkins University Press.

Mohanty, C. T. (2006). Feminism without borders: Decolonizing theory, practicing solidarity . Duke University Press.

McLeod, J. (2017). Gender and schooling . Retrieved from https://juliemcleod.net/projects/gender-schooling/

Monkman, K. (2011). Framing gender, education and empowerment . Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.2304/rcie.2011.6.1.1

Monkman, K., & Webster, K. (2015). The transformative potential of global gender and education policy. In J. Zajda (Ed.), Second international handbook of globalisation, education and policy research. Springer.

Muntoni, F., Wagner, J., & Retelsdorf, J. (2020). Beware of stereotypes: Are classmates’ stereotypes associated with students’ reading outcomes? Retrieved from https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/cdev.13359

OECD. (2019a). Gender equality . Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/gender/Gender-

OECD. (2019b). Conceptual learning framework: Attitudes and values . OECD.

Page, E., & Jha, J. (Eds.). (2009). Exploring the bias: Gender and stereotyping in secondary schools . Commonwealth Secretariat.

Sadker, D., Sadker, M., & Zittleman, K. (2009). Still failing at fairness: How gender bias cheats girls and boys in schools and what we can do about it . Scribner.

Sekhar Pm, A., & Parameswari, J. (2019). Gender stereotype in education . Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344475448_Gender_Stereotype_in_Education

Smith, K. (2021). Gender stereotypes: Primary schools urged to tackle issue . Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/education-57256075

Spears Brown, C. (2019). Sexualized gender stereotypes predict girls’ academic self-efficacy and motivation across middle school . Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0165025419862361

Stromquist, N. (2007). The gender socialization process in schools: A cross-national comparison . Retrieved from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Gender-Socialization-Process-in-Schools%3A-A-Stromquist/21c8cab2ac260b0ce7e6a90a6968c0b670e8707a

Stromquist, N. (2017). The gender dimension in the World Bank’s perception . Retrieved from https://www.ei-ie.org/en/item/22262:wdr2018-reality-check-7-the-gender-dimension-in-the-world-banks-perception-by-nelly-stromquist

Stromquist, N., & Fischman, G. (2009). Introduction: From denouncing gender inequities to undoing gender in education: practices and programmes toward change in the social relations of gender. International Review of Education, 55 , 463–482.

UNICEF. (2018a). Gender equality: Global annual results report 2018 . UNICEF.

UNICEF. (2018b). Gender Action Plan 2018-2021 . UICEF.

UNICEF. (2021). Reimagining girls’ education solutions to keep girls learning in emergencies . UNICEF.

Unterhalter, E. et al. (2014). Girls’ education and gender equality . Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Elaine-Unterhalter/publication/263425162_Girls%27_education_and_gender_equality_Education_Rigorous_Literature_Review/links/00b4953ac89b1300ba000000/Girlseducation-and-gender-equality-Education-Rigorous-Literature-Review.pdf

Zajda, J. (Ed.). (2021a). 3rd international handbook of globalisation, education and policy research . Springer.

Zajda, J. (2021b). Globalisation and education reforms: Creating effective learning . Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Zajda, J. (2021c). Organizational and pedagogical leadership in the 21st century: Standards-driven and outcomes-defined imperatives. In A. Nir (Ed.), School leadership in the 21st century: Challenges and strategies . Nova Science Publishers.

Zajda, J., & Rust, V. (2021). Globalisation and comparative education . Springer.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Australian Catholic University, Faculty of Education & Arts, School of Education, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Joseph Zajda

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Zajda, J. (2022). Discourses of Gender Inequality in Education. In: Discourses of Globalisation and Education Reforms. Globalisation, Comparative Education and Policy Research, vol 31. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96075-9_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96075-9_4

Published : 18 May 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-96074-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-96075-9

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Require students to critically think about how power structures benefit from gender stereotypes and what people can do to resist them. Familiarize students with real individuals or characters who have non-gender-stereotypical professions or positively challenge gender stereotypes, such as male nurses and female scientists or men as caretakers.

Critical reflection on how to understand gender and education is evident in writings on African feminism (Decker and Baderoon Citation 2018; Kwachou Citation 2020), decoloniality (Frost Citation 2011; Bhambra Citation 2014), new materialism (Harding Citation 2017) and queer theory (Butler Citation 1990; Martino and Cumming-Potvin Citation 2018 ...

The examination of gender inequality in education around the globe reveals a multifaceted issue deeply intertwined with persistent challenges within education systems and society at large. Over the past three decades, girls’ education has often been portrayed as a panacea, touted as the solution to a wide array of societal problems, including issues as diverse as high fertility rates and ...

Joseph Cimpian explains the large-scale problems girls and women face in America's education system, and why policy alone can't fix them.

Gender equity in education stands as a cornerstone for fostering social empowerment and advancing towards a more inclusive society. This review delves into the challenges hindering gender...

This paper offers a critical examination of the nature of inequalities in relation to education and the pursuit of social justice. It argues that assessment of educational resources and measures such as school enrolment and educational achievement are limited in what they tell us about the injustices learners may experience.

How does race, class, and gender influence how education scholars perceive educational problems, which education issues are worth exploring, and who, according to scholars, should be protected in schools?

Based on the analytical framework developed by the OECD Strength through Diversity project, this paper provides an overview of gender stereotyping in education, with some illustrations of policies and practices in place across OECD countries, with a focus on curriculum arrangements, capacity-building strategies and school-level interventions in ...

Awareness of gender issues is the first step in overcoming gender discrimination; action is the next. This entry overviews gender issues in education, as a starting point for raising awareness.

Informed and data driven critical discussions surrounding gender inequality in education need to reflect the role of ideology, cultural and gender stereotypes, and defining dominant beliefs and values in a cross-cultural perspective.