1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

Welcome to 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology , an ever-growing set of over 190 original 1000-word essays on philosophical questions, theories, figures, and arguments.

All of our essays are available in audio format; many of our essays are available as videos .

Newest Essays

Here are our newest essays :

- Robert Nozick’s “Wilt Chamberlain” Argument for Libertarianism by Daniel Weltman

- Artificial Intelligence: Ethics, Society, and the Environment and Artificial Intelligence: The Possibility of Artificial Minds by Thomas Metcalf

- Pyrrhonian Skepticism: Suspending Judgment by Lewis Ross

- Moral Education: Teaching Students to Become Better People by Dominik Balg

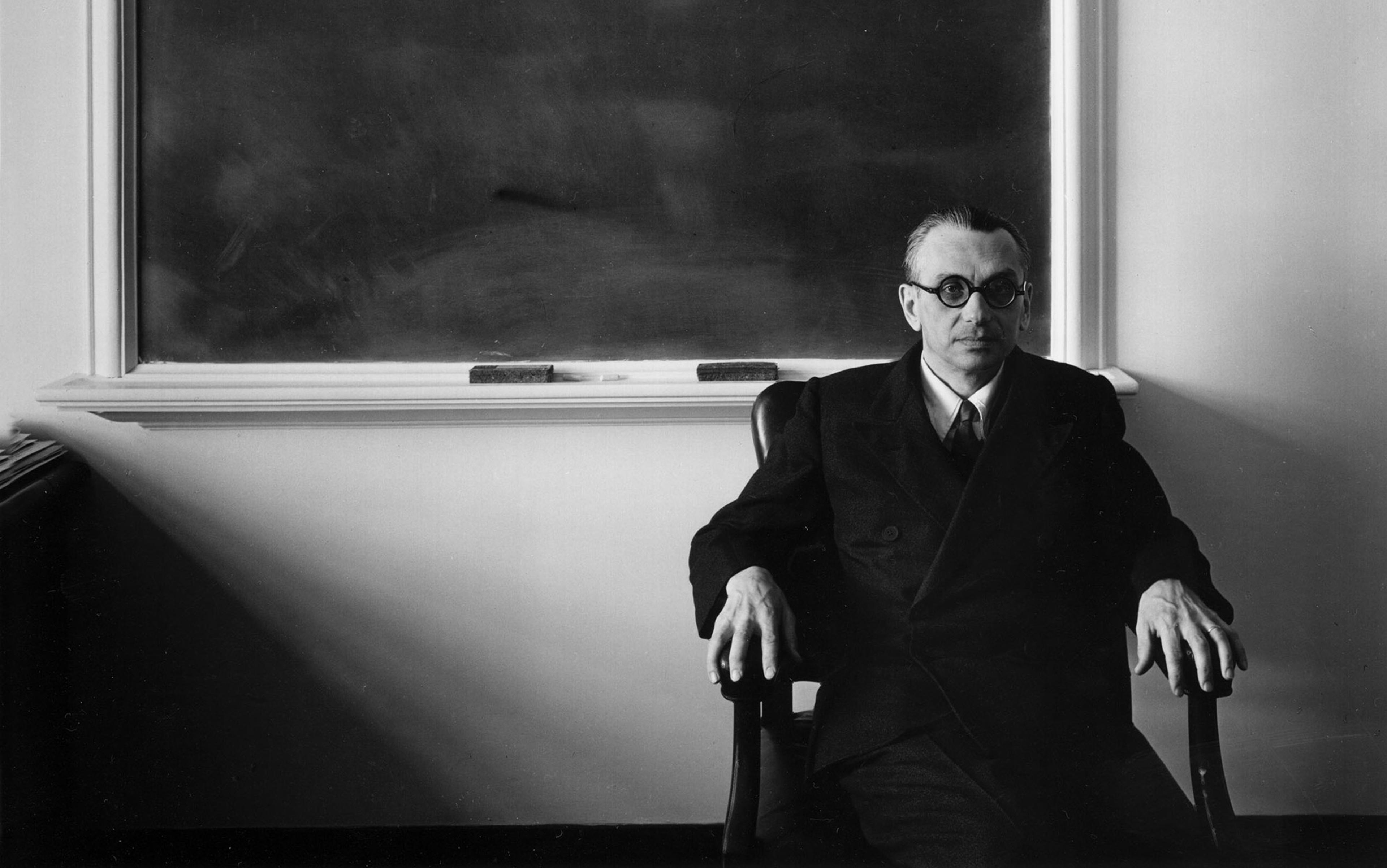

- Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems by Jon Charry

- Objects and their Parts: The Problem of Material Composition by Jeremy Skrzypek

- The Mind-Body Problem: What Are Minds? by Jacob Berger

- Seemings: Justifying Beliefs Based on How Things Seem by Kaj André Zeller

- Form and Matter: Hylomorphism by Jeremy W. Skrzypek

- Kant’s Theory of the Sublime by Matthew Sanderson

- Philosophy of Color by Tiina Carita Rosenqvist

- On Karl Marx’s Slogan “From Each According to their Ability, To Each According to their Need” by Sam Badger

We publish new essays frequently, so please check back for updates. Also follow us on Facebook , Twitter / X , and Instagram , and subscribe by email on this page to receive notifications of new essays.

Essay Categories

We have essays in these categories:

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Africana Philosophy

- Buddhist Philosophy

- Chinese Philosophy

- Epistemology, or Theory of Knowledge

- Historical Philosophy

- Islamic Philosophy

- Logic and Reasoning

- Metaphilosophy, or Philosophy of Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Phenomenology and Existentialism

- Philosophy of Education

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Mind and Language

- Philosophy of Race

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Sex and Gender

- Social and Political Philosophy

New categories are added as the project expands.

New to Philosophy?

You might begin with these essays:

- What is Philosophy? by Thomas Metcalf

- Critical Thinking: What is it to be a Critical Thinker? by Carolina Flores

- Arguments: Why Do You Believe What You Believe? by Thomas Metcalf

- Is it Wrong to Believe Without Sufficient Evidence? W.K. Clifford’s “The Ethics of Belief” by Spencer Case

Popular Essays

Some of our most popular essays include:

- Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am” by Charles Miceli and Descartes’ Meditations by Marc Bobro

- Marx’s Conception of Alienation by Dan Lowe

- John Rawls’ ‘A Theory of Justice’ by Ben Davies

- The Ethics of Abortion by Nathan Nobis

- Aristotle’s Defense of Slavery by Dan Lowe

- “God is Dead”: Nietzsche and the Death of God by Justin Remhof

- Philosophy and Its Contrast with Science : Comparing Philosophical and Scientific Understanding by Thomas Metcalf

- Happiness: What is it to be Happy? by Kiki Berk

- Pascal’s Wager: A Pragmatic Argument for Belief in God by Liz Jackson

- The African Ethic of Ubuntu by Thaddeus Metz

A complete list of all our essays is here .

Student Resources

We have resources for students , including essays on How to Read Philosophy and How to Write a Philosophical Essay by the Editors of 1000-Word Philosophy .

Instructor Resources

We have resources to help i nstructors develop courses and course modules using our essays.

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook , Twitter / X , and Instagram and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at 1000WordPhilosophy.com

Share this:.

The 25 Most Influential Philosophers of All Time–A Philosophy Study Starter

Whether you’re majoring in philosophy, beginning your personal journey to better understand the universe, or you just have some humanities credits to fulfill, this is a great place to start. Logically speaking (which is an important way to speak within the context of philosophy), the most influential philosophers in history are responsible for the most influential ideas in history. These are the thinkers who put forth notions that still inform our understanding of the human condition today—groundbreaking, illuminating, ingenious (and frequently debunked) notions about reasoning, reality, spirituality, consciousness, dreams, social organization, human behavior, logic, and even love.

The list here is a portal to the history of human thought, a window into everything and nothing all at once. And yet, this is by no means a comprehensive discussion. The number of individuals who have impacted the course of human history through their insight, intuition, and intellect is far too great to quantify. And ideas expressed just by those included here fill untold volumes of writing. But based on our findings, this is the top tier of thinkers, those who paved the way for all which came after, who laid the foundation for so much of what we hold to be true, who in essence created the field of study we call philosophy.

What follows is a list of the The 25 Most Influential Philosophers of all time based on the period of history between 1000 BCE and 2000 CE. This is a bird’s eye view of philosophy, an overview from the very top, but by no means a comprehensive nor probing dive into any one area. That’s why we call this a Study Starter. We just get the ball rolling. The rest is up to you...

Influence Rankings

The InfluenceRanking engine calculates a numerical influence score for people, institutions, and disciplinary programs. It performs this calculation by drawing from Wikipedia/data, Crossref, and an ever-growing body of data reflecting academic achievement and merit.

The InfluenceRanking engine measures the influence of a given person in a given discipline, as well as in important related subdisciplines. Influence can also be measured within a specific set of time parameters. For instance, it is said that Greek thinker Pythagoras coined the term philosophy in the 6th Century BC. This, therefore, seems an appropriate starting point for the period under investigation. Accordingly, our ranking of the 25 Most Influential Philosophers of All Time uses the time parameters of 1000 BC to 2000 CE.

A Note On Diversity

We concede from the outset that this ranking list reflects a problem, not specifically with our algorithm, but with the human history of influence. What follows is a list composed entirely of men, most of them European, descendent from European ancestry, or famous for proliferating European ideas. Absent are the great women who have altered the course of human history by way of their ideas and actions. Also limited in appearance are the brilliant thinkers from Arabic or African antiquity, from Eastern traditions of thought, or from more recent centuries where the greatest minds were set to work on advancing civil rights.

- Top Influential Black Philosophers

This is not because we have overlooked these thinkers, nor because their contributions don’t warrant inclusion in such a list. Rather, this is a direct reflection of the enormous scope of time accounted for in our ranking. Across the vast majority of the 3000 years represented here, social, racial, and gender inequality have been very real and very consequential realities. Moreover, our rankings are limited to those thinkers whose work has enjoyed extensive translation in the English-speaking world.

Because our influence rankings measure the raw permeation of citations, writing, and ideas originating with each of these thinkers, the rigid prejudices that have persisted throughout history are also reflected on our list. This is not an endorsement of those prejudices-merely a faithful reporting on a subject which is inherently reflective of those prejudices.

Happily, when one distills a more current period of history in the philosophy discipline, one can see just how much the field of thought has evolved today, such that a meaningful number of women, people of color, and people of non-European origin are represented. This denotes a clear evolution in an academic field that, for all of its insight and illumination, also has a deep-seated history of Eurocentrism.

For a look at the philosophers with the greatest influence on the field today, check out:

- Top Influential Philosophers Today

With this limitation acknowledged, we bring you...

The Most Influential Philosophers of All Time

What follows is a list, in order, of the most influential philosophers who ever lived. Most of the names below will be familiar, though you might find a few surprises.

Other information provided below includes a condensed Wikipedia bio for each philosopher, their Key Contributions to the discipline, and Selected Works. You can also click on the profile link for each philosopher to see where they rank in specific philosophy subdisciplines, such as logic, ethics, and metaphysics.

1. Socrates (470 BC–399 BC)/ Plato (429 BC–347 BC)

*Socrates and Plato are inseparable from one another in the history of thought and are therefore inseparable in our ranking.

Socrates was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy, and as being the first moral philosopher of the Western ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, he made no writings, and is known chiefly through the accounts of classical writers writing after his lifetime, particularly his students Plato and Xenophon. Other sources include the contemporaneous Antisthenes, Aristippus, and Aeschines of Sphettos. Aristophanes, a playwright, is the main contemporary author to have written plays mentioning Socrates during Socrates’ lifetime, though a fragment of Ion of Chios’ Travel Journal provides important information about Socrates’ youth.

The most influential of Socrates’ students, Plato was an Athenian philosopher during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He was the founder of the Platonist school of thought, and the Academy, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. He is widely considered as one of the most important and influential individuals in human history, and the pivotal figure in the history of Ancient Greek and Western philosophy, along with his teacher, Socrates, and his most famous student, Aristotle.

Plato has also often been cited as one of the founders of Western religion and spirituality. The so-called neoplatonism of philosophers such as Plotinus and Porphyry greatly influenced Christianity through Church Fathers such as Augustine. Alfred North Whitehead once noted: “the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.” Unlike the work of nearly all of his contemporaries, Plato’s entire body of work is believed to have survived intact for over 2,400 years. Although their popularity has fluctuated, Plato’s works have consistently been read and studied.

Key Contributions from Socrates

- Socratic Dialogue

- Socratic Questioning

- Socratic Method

Key Contributions from Plato

- Theory of Forms

- Theory of Soul

Selected Works

*There is limited consensus about the exact publication date for each of these works. Dates below should be seen as approximations.

**Though Socrates is widely considered the father of the Western philosophical tradition, he authored no texts during his lifetime. His influence was felt in his lifetime through his dialogues with prominent pupils. Therefore, he is best read through the works of his most influential students:

- Apology of Socrates (c. 399 BC)

- The Phaedo (c. 399 BC)

- Crito (c. 399 BC)

- Symposium (c. 385-370 BC)

- The Republic (c. 375 BC)

- The Sophist (c. 360 BC)

- Timaeus (c. 360 BC)

- Symposium (c. 422 BC)

- Apology of Socrates to the Jury (c. 399 BC)

- Memorabilia (c. 371 BC)

- Oeconomicus (c. 362 BC)

Find out where Socrates among philosophy’s major branches and subdisciplines.

Find out where Plato among philosophy’s major branches and subdisciplines.

2. Aristotle (384 BC–322 BC)

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Lyceum, the Peripatetic school of philosophy, and the Aristotelian tradition. His writings cover many subjects including physics, biology, zoology, metaphysics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, poetry, theatre, music, rhetoric, psychology, linguistics, economics, politics, and government.

Aristotle provided a complex synthesis of the various philosophies existing prior to him. It was above all from his teachings that the West inherited its intellectual lexicon, as well as problems and methods of inquiry. As a result, his philosophy has exerted a unique influence on almost every form of knowledge in the West and it continues to be a subject of contemporary philosophical discussion.

Key Contributions

- Aristotelianism

- Peripatetic school

- On the Soul (c. 350 BC)

- Nicomachean Ethics (c. 340 BC)

- Metaphysics (c. 335-323 BC)*

- Rhetoric (c. 322 BC)

Find out where this influencer ranks among philosophy’s major branches and subdisciplines.

3. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804)

Immanuel Kant was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Kant’s comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics have made him one of the most influential figures in modern Western philosophy. In his doctrine of transcendental idealism, Kant argued that space and time are mere “forms of intuition” which structure all experience, and therefore that while “things-in-themselves” exist and contribute to experience, they are nonetheless distinct from the objects of experience. From this it follows that the objects of experience are mere “appearances”, and that the nature of things as they are in themselves is consequently unknowable to us.

In an attempt to counter the skepticism he found in the writings of philosopher David Hume, he wrote the Critique of Pure Reason (1781/1787), one of his most well-known works. In it, he developed his theory of experience to answer the question of whether synthetic a priori knowledge is possible, which would in turn make it possible to determine the limits of metaphysical inquiry. Kant drew a parallel to the Copernican revolution in his proposal that the objects of the senses must conform to our spatial and temporal forms of intuition, and that we can consequently have a priori cognition of the objects of the senses. Kant believed that reason is also the source of morality, and that aesthetics arise from a faculty of disinterested judgment. Kant’s views continue to have a major influence on contemporary philosophy, especially the fields of epistemology, ethics, political theory, and post-modern aesthetics.

- Categorical Imperative

- Kantian Ethics

- Practical Reason

- Transcendental Idealism

- Universal Natural History (1755)

- Critique of Practical Reason (1788)

- Critique of Judgment (1790)

- Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason (1793)

- Metaphysics of Morals (1797)

4. René Descartes (1596–1650)

René Descartes was a French philosopher, mathematician, and scientist. A native of the Kingdom of France, he spent about 20 years of his life in the Dutch Republic after serving for a while in the Dutch States Army of Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange and the Stadtholder of the United Provinces. One of the most notable intellectual figures of the Dutch Golden Age, Descartes is also widely regarded as one of the founders of modern philosophy.

Many elements of Descartes’s philosophy have precedents in late Aristotelianism, the revived Stoicism of the 16th century, or in earlier philosophers like Augustine. In his natural philosophy, he differed from the schools on two major points: first, he rejected the splitting of corporeal substance into matter and form; second, he rejected any appeal to final ends, divine or natural, in explaining natural phenomena. In his theology, he insists on the absolute freedom of God’s act of creation. Refusing to accept the authority of previous philosophers, Descartes frequently set his views apart from the philosophers who preceded him. In the opening section of the Passions of the Soul , an early modern treatise on emotions, Descartes goes so far as to assert that he will write on this topic “as if no one had written on these matters before.” His best known philosophical statement is ” cogito, ergo sum ″ (“I think, therefore I am”; French: Je pense, donc je suis ), found in Discourse on the Method (1637; in French and Latin) and Principles of Philosophy (1644, in Latin).

Descartes has often been called the father of modern philosophy, and is largely seen as responsible for the increased attention given to epistemology in the 17th century.

- Cogito, Ergo Sum

- Cartesian Doubt

- Cartesian Coordinate System

- Cartesian Dualism

- Discourse on the Method (1637)

- Meditations on First Philosophy (1641)

- Principles of Philosophy (1644)

- Passions of the Soul (1649)

5. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900)

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a German philosopher, cultural critic, composer, poet, and philologist whose work has exerted a profound influence on modern intellectual history. He began his career as a classical philologist before turning to philosophy. He became the youngest person ever to hold the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in 1869 at the age of 24. Nietzsche resigned in 1879 due to health problems that plagued him most of his life; he completed much of his core writing in the following decade. In 1889, at age 44, he suffered a collapse and afterward a complete loss of his mental faculties. He lived his remaining years in the care of his mother until her death in 1897 and then with his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche.

Nietzsche’s writing spans philosophical polemics, poetry, cultural criticism, and fiction while displaying a fondness for aphorism and irony. Prominent elements of his philosophy include his radical critique of truth in favor of perspectivism; a genealogical critique of religion and Christian morality and related theory of master-slave morality; the aesthetic affirmation of life in response to both the “death of God” and the profound crisis of nihilism; the notion of Apollonian and Dionysian forces; and a characterization of the human subject as the expression of competing wills, collectively understood as the will to power. He also developed influential concepts such as the Übermensch and the doctrine of eternal return. In his later work, he became increasingly preoccupied with the creative powers of the individual to overcome cultural and moral mores in pursuit of new values and aesthetic health. His body of work touched a wide range of topics, including art, philology, history, religion, tragedy, culture, and science, and drew inspiration from figures such as Socrates, Zoroaster, Arthur Schopenhauer, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Richard Wagner and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

- Master-slave Morality

- God is Dead

- Human, All Too Human (1878)

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883)

- Beyond Good and Evil (1886)

- On the Genealogy of Morality (1887)

- Ecce Homo (1888; published in 1908)

6. Karl Marx (1818–1883)

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist and socialist revolutionary. Born in Trier, Germany, Marx studied law and philosophy at university. He married Jenny von Westphalen in 1843. Due to his political publications, Marx became stateless and lived in exile with his wife and children in London for decades, where he continued to develop his thought in collaboration with German thinker Friedrich Engels and publish his writings, researching in the reading room of the British Museum.

His best-known titles are the 1848 pamphlet The Communist Manifesto and the three-volume Das Kapital . Marx’s political and philosophical thought had enormous influence on subsequent intellectual, economic and political history. His name has been used as an adjective, a noun and a school of social theory.

- Economic Determinism

- Historical Materialism

- Marxist Dialectic

- Marxist Philosophy of Nature

- Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right (1843)

- Wage Labour and Capital (1847)

- Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848)

- Das Kapital, Vol. 1 (1867)

7. Avicenna (980–1037)

Ibn Sina, also known as Abu Ali Sina , Pur Sina , and often known in the West as Avicenna , was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, thinkers and writers of the Islamic Golden Age, and the father of early modern medicine. Sajjad H. Rizvi has called Avicenna “arguably the most influential philosopher of the pre-modern era”. He was a Muslim Peripatetic philosopher influenced by Aristotelian philosophy. Of the 450 works he is believed to have written, around 240 have survived, including 150 on philosophy and 40 on medicine.

His most famous works are The Book of Healing , a philosophical and scientific encyclopedia, and The Canon of Medicine , a medical encyclopedia which became a standard medical text at many medieval universities and remained in use as late as 1650. Besides philosophy and medicine, Avicenna’s corpus includes writings on astronomy, alchemy, geography and geology, psychology, Islamic theology, logic, mathematics, physics and works of poetry.

- Islamic Metaphysics

- Proof of the Truthful

- Floating Man

- The Canon of Medicine (1025)

- The Book of Healing (1027)

- Al Nijat (Published 1913)

8. David Hume (1711–1776)

David Hume was a Scottish Enlightenment philosopher, historian, economist, librarian and essayist, who is best known today for his highly influential system of philosophical empiricism, skepticism, and naturalism. Beginning with A Treatise of Human Nature , Hume strove to create a naturalistic science of man that examined the psychological basis of human nature. Hume argued against the existence of innate ideas, positing that all human knowledge derives solely from experience. This places him with Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and George Berkeley, as a British Empiricist.

- Bundle Theory

- Association of Ideas

- Hume’s Fork

- A Treatise of Human Nature (1740)

- An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals (1751)

- An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1758)

- Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779; posthumously)

9. Martin Heidegger (1889–1976)

Martin Heidegger was a German philosopher and a seminal thinker in the Continental tradition of philosophy. He is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. In Heidegger’s fundamental text Being and Time (1927), “Dasein” is introduced as a term for the specific type of being that humans possess.[15] Dasein has been translated as “being there”. Heidegger believes that Dasein already has a “pre-ontological” and non-abstract understanding that shapes how it lives. This mode of being he terms “being-in-the-world”.

Commentators have noted that Dasein and “being-in-the-world” are unitary concepts in contrast with the “subject/object” view of rationalist philosophy since at least René Descartes. Heidegger uses an analysis of Dasein to approach the question of the meaning of being, which Heidegger scholar Michael Wheeler describes as “concerned with what makes beings intelligible as beings”. Heidegger’s later work includes criticism of the view, common in the Western tradition, that all of nature is a “standing reserve” on call, as if it were a part of industrial inventory. Heidegger was a member and supporter of the Nazi Party. There is controversy as to the relationship between his philosophy and his Nazism.

*Indeed, because of Heidegger’s connection to Nazism, we consider his inclusion on this list controversial. However, his performance using our Ranking Analytics made this inclusion unavoidable. For more on the sometimes overlapping phenomena of influence and infamy, take a look at our discussion on the undeniable influence of terror mastermind Osama bin Laden .

- Heideggerian terminology

- Ontological Difference

- Being and Time (1927)

- Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics (1929)

- Introduction to Metaphysics (1935)

- The Principle of Reason (1955-56)

- Identity and Difference (1955-57)

10. Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951)

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein was an Austrian-British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. He is considered by some to be the greatest philosopher of the 20th century. From 1929 to 1947, Wittgenstein taught at the University of Cambridge. In spite of his position, during his entire life only one book of his philosophy was published, the relatively slim 75-page Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung (Logical-Philosophical Treatise) (1921) which appeared, together with an English translation, in 1922 under the Latin title Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus .

His only other published works were an article, “Some Remarks on Logical Form” (1929), a book review, and a children’s dictionary. His voluminous manuscripts were edited and published posthumously. The first and best-known of this posthumous series is the 1953 book Philosophical Investigations . A survey among American university and college teachers ranked the Investigations as the most important book of 20th-century philosophy, standing out as “the one crossover masterpiece in twentieth-century philosophy, appealing across diverse specializations and philosophical orientations.”

- Family Resemblance

- Form of Life

- Language-Game

- Wittgenstein’s Ladder

- Tractatus Logico-Philosphicus (1921)

- Some Remarks on Logical Form (1929)

- Philosophical Investigations (1953)

- Lectures and Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Belief (1967)

11. John Locke (1632–1704)

John Locke was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the “Father of Liberalism”. Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Sir Francis Bacon, Locke is equally important to social contract theory. His work greatly affected the development of epistemology and political philosophy. His writings influenced Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, many Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, as well as the American Revolutionaries. His contributions to classical republicanism and liberal theory are reflected in the United States Declaration of Independence.

- Natural Rights

- Lockean Proviso

- Consent of the Governed

- Consciousness

- Social Contract

- A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689)

- An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689)

- Two Treatises of Government (1690)

- Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693)

12. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831)

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was a German philosopher and an important figure in German idealism. He is considered one of the fundamental figures of modern Western philosophy, with his influence extending to the entire range of contemporary philosophical issues, from aesthetics to ontology to politics, both in the analytic and continental tradition. Hegel’s principal achievement was his development of a distinctive articulation of idealism, sometimes termed absolute idealism , in which the dualisms of, for instance, mind and nature and subject and object are overcome.

- Hegelian Dialectic

- Master-slave Dialectic

- Phenomenology of Spirit (1807)

- Science of Logic (1812-1816)

- Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1816)

- Elements of the Philosophy of Right (1820)

13. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274)

Thomas Aquinas was an Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, Catholic priest, and Doctor of the Church. An immensely influential philosopher, theologian, and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism, he is also known within the latter as the and the . The name Aquinas identifies his ancestral origins in the county of Aquino in present-day Lazio, Italy. He was the foremost classical proponent of natural theology and the father of Thomism; of which he argued that reason is found in God. His influence on Western thought is considerable, and much of modern philosophy developed or opposed his ideas, particularly in the areas of ethics, natural law, metaphysics, and political theory.

- Scholasticism

- Theological Intellectualism

- Moderate Realism

- Summa contra Gentiles (1259-1265)

- Summa Theologiae (1265-1274)

14. Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855)

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard was a Danish philosopher, theologian, poet, social critic and religious author who is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher. He wrote critical texts on organized religion, Christendom, morality, ethics, psychology, and the philosophy of religion, displaying a fondness for metaphor, irony and parables. Much of his philosophical work deals with the issues of how one lives as a “single individual”, giving priority to concrete human reality over abstract thinking and highlighting the importance of personal choice and commitment. He was against literary critics who defined idealist intellectuals and philosophers of his time, and thought that Swedenborg, Hegel, Fichte, Schelling, Schlegel and Hans Christian Andersen were all “understood” far too quickly by “scholars”.

- Existentialism

- Leap of Faith

- On The Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates (1841)

- Fear and Trembling (1843)

- Either/Or (1843)

- The Sickness Unto Death (1849)

15. Edmund Husserl (1859–1938)

Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl was a German philosopher who established the school of phenomenology. In his early work, he elaborated critiques of historicism and of psychologism in logic based on analyses of intentionality. In his mature work, he sought to develop a systematic foundational science based on the so-called phenomenological reduction. Arguing that transcendental consciousness sets the limits of all possible knowledge, Husserl redefined phenomenology as a transcendental-idealist philosophy. Husserl’s thought profoundly influenced 20th-century philosophy, and he remains a notable figure in contemporary philosophy and beyond.

- Phenomenology

- Formal Ontology

- Theory of Moments

- Philosophy of Arithmetic (1891)

- Logical Investigations (1900)

- Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Present Phenomenological Philosophy (1913)

- Cartesian Meditations (1931)

16. Bertrand Russell (1872–1970)

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell was a British polymath. As an academic, he worked in philosophy, mathematics, and logic. His work has had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, artificial intelligence, cognitive science, computer science and various areas of analytic philosophy, especially logic, philosophy of mathematics, philosophy of language, epistemology and metaphysics. Russell was also a public intellectual, historian, social critic, political activist, and Nobel laureate.

- Analytic Philosophy

- Axiom of Reducibility

- Automated Reasoning

- Mathematical Beauty

- The Principles of Mathematics (1903)

- On Denoting (1905)

- Principia Mathematica (1910)

- Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy (1919)

17. Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980)

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary critic. He was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism and phenomenology, and one of the leading figures in 20th-century French philosophy and Marxism. His work has also influenced sociology, critical theory, post-colonial theory, and literary studies, and continues to influence these disciplines.

- Existence Precedes Essence

- Being-in-itself

- Nausea (1938)

- Being and Nothingness (1943)

- No Exit (1944)

- Existentialism and Humanism (1946)

18. Jacques Derrida (1930–2004)

Jacques Derrida was an Algerian-born French philosopher best known for developing a form of semiotic analysis known as deconstruction, which he discussed in numerous texts, and developed in the context of phenomenology. He is one of the major figures associated with post-structuralism and postmodern philosophy.

- Deconstruction

- Phallogocentrism

- Speech and Phenomena (1967)

- Of Grammatology (1967)

- Writing and Difference (1967)

- Margins of Philosophy (1972)

19. Michel Foucault (1926–1984)

Paul-Michel Foucault was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, social theorist, and literary critic. Foucault’s theories primarily address the relationship between power and knowledge, and how they are used as a form of social control through societal institutions. Though often cited as a structuralist and postmodernist, Foucault rejected these labels. His thought has influenced academics, especially those working in communication studies, anthropology, psychology, sociology, criminology, cultural studies, literary theory, feminism, Marxism and critical theory.

- Disciplinary institution

- Foucauldian discourse analysis

- Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (1961)

- The Birth of the Clinic: An Archeology of Medical Perception (1963)

- The Order of Things: An Archeology of the Human Sciences (1966)

- The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969)

20. Averroes (1126–1198)

Ibn Rushd (full name in Arabic: أبو الوليد محمد ابن احمد ابن رشد, romanized: Abū l-Walīd Muḥammad Ibn ʾAḥmad Ibn Rušd;) often Latinized as Averroes was a Muslim Andalusian polymath and jurist of Berber descent who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, mathematics, Islamic jurisprudence and law, and linguistics. The author of more than 100 books and treatises, his philosophical works include numerous commentaries on Aristotle, for which he was known in the western world as The Commentator and Father of Rationalism . Ibn Rushd also served as a chief judge and a court physician for the Almohad Caliphate. Averroes was a strong proponent of Aristotelianism; he attempted to restore what he considered the original teachings of Aristotle and opposed the Neoplatonist tendencies of earlier Muslim thinkers, such as Al-Farabi and Avicenna.

- Unity of the Intellect

- Aristotelianism in the Islamic philosophical tradition

- Philosophy within a Muslim Religious Tradition

- The General Principles of Medicine (c. 1162)

- Decisive Treatise on the Agreement Between Religious Law and Philosophy (c. 1178-1180)

- Examination of the Methods of Proof Concerning the Doctrines of Religion (c. 1179-1180)

- The Incoherence of the Incoherence (c. 1179-1180)

21. John Stuart Mill (1806–1873)

John Stuart Mill , usually cited as J. S. Mill, was an English philosopher, political economist, and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to social theory, political theory, and political economy. Dubbed “the most influential English-speaking philosopher of the nineteenth century”, he conceived of liberty as justifying the freedom of the individual in opposition to unlimited state and social control.

- Utilitarianism

- Liberal Feminism

- Mill’s Methods

- A System of Logic (1843)

- On Liberty (1859)

- Utilitarianism (1863)

- The Subjection of Women (1869)

22. William James (1842–1910)

William James was an American philosopher and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States. James is considered to be a leading thinker of the late nineteenth century, one of the most influential philosophers of the United States, and the “Father of American psychology”. Along with Charles Sanders Peirce, James established the philosophical school known as pragmatism, and is also cited as one of the founders of functional psychology. A Review of General Psychology analysis, published in 2002, ranked James as the 14th most eminent psychologist of the 20th century. A survey published in American Psychologist in 1991 ranked James’s reputation in second place, after Wilhelm Wundt, who is widely regarded as the founder of experimental psychology. James also developed the philosophical perspective known as radical empiricism.

- The Will to Believe

- Pragmatic Theory of Truth

- Radical Empiricism

- Stream of Consciousness

- The Principles of Psychology (1890)

- The Will To Believe, and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy (1897)

- The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature (1902)

- Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking (1907)

23. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716)

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was a prominent German polymath and one of the most important logicians, mathematicians and natural philosophers of the Enlightenment. As a representative of the seventeenth-century tradition of rationalism, Leibniz developed, as his most prominent accomplishment, the ideas of differential and integral calculus, independently of Isaac Newton’s contemporaneous developments. Mathematical works have consistently favored Leibniz’s notation as the conventional expression of calculus. It was only in the 20th century that Leibniz’s law of continuity and transcendental law of homogeneity found mathematical implementation.

- The Product Rule

- Law of Continuity

- Best of All Possible Worlds

- Meditations on Knowledge, Truth, and Ideas (1864)

- Discourse on Metaphysics (1686)

- New Essays on Human Understanding (1704)

- The Theodicy (1710)

- Monadology (1714)

24. Gottlob Frege (1848–1925)

- Frege’s Propositional Calculus

- Principle of Compositionality

- Context Principle

- Begriffsschrift (1879)

- The Foundations of Arithmetic (1884)

- Basic Laws of Arithmetic (1893-1903)

25. John Dewey (1859–1952)

John Dewey was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He is regarded as one of the most prominent American scholars in the first half of the twentieth century. The overriding theme of Dewey’s works was his profound belief in democracy, be it in politics, education, or communication and journalism. As Dewey himself stated in 1888, while still at the University of Michigan, “Democracy and the one, ultimate, ethical ideal of humanity are to my mind synonymous.” Dewey was one of the primary figures associated with the philosophy of pragmatism and is considered one of the fathers of functional psychology.

- Instrumentalism

- Functional Psychology

- Progressive Education

- Occupational Psychosis

- Psychology (1887)

- Leibniz’s New Essays Concerning the Human Understanding (1888)

- Ethics (1908)

- Democracy and Education (1916)

- Art as Experience (1934)

And if this bird’s eye view of the philosophy discipline has sparked your interest, consider diving a little deeper with a look at:

- The 25 Most Influential Philosophy Books

- How to Major in Philosophy

- What Can I do With a Master’s in Philosophy?

Find additional study resources with a look at our study guides for students at every stage of the educational journey.

Or get valuable study tips, advice on adjusting to campus life, and much more at our student resource homepage .

Guide to the classics: Michel de Montaigne’s Essays

Associate Professor in Philosophy, Deakin University

Disclosure statement

Matthew Sharpe is part of an ARC funded project on modern reinventions of the ancient idea of "philosophy as a way of life", in which Montaigne is a central figure.

Deakin University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

When Michel de Montaigne retired to his family estate in 1572, aged 38, he tells us that he wanted to write his famous Essays as a distraction for his idle mind . He neither wanted nor expected people beyond his circle of friends to be too interested.

His Essays’ preface almost warns us off:

Reader, you have here an honest book; … in writing it, I have proposed to myself no other than a domestic and private end. I have had no consideration at all either to your service or to my glory … Thus, reader, I myself am the matter of my book: there’s no reason that you should employ your leisure upon so frivolous and vain a subject. Therefore farewell.

The ensuing, free-ranging essays, although steeped in classical poetry, history and philosophy, are unquestionably something new in the history of Western thought. They were almost scandalous for their day.

No one before Montaigne in the Western canon had thought to devote pages to subjects as diverse and seemingly insignificant as “Of Smells”, “Of the Custom of Wearing Clothes”, “Of Posting” (letters, that is), “Of Thumbs” or “Of Sleep” — let alone reflections on the unruliness of the male appendage , a subject which repeatedly concerned him.

French philosopher Jacques Rancière has recently argued that modernism began with the opening up of the mundane, private and ordinary to artistic treatment. Modern art no longer restricts its subject matters to classical myths, biblical tales, the battles and dealings of Princes and prelates.

If Rancière is right, it could be said that Montaigne’s 107 Essays, each between several hundred words and (in one case) several hundred pages, came close to inventing modernism in the late 16th century.

Montaigne frequently apologises for writing so much about himself. He is only a second rate politician and one-time Mayor of Bourdeaux, after all. With an almost Socratic irony , he tells us most about his own habits of writing in the essays titled “Of Presumption”, “Of Giving the Lie”, “Of Vanity”, and “Of Repentance”.

But the message of this latter essay is, quite simply, that non, je ne regrette rien , as a more recent French icon sang:

Were I to live my life over again, I should live it just as I have lived it; I neither complain of the past, nor do I fear the future; and if I am not much deceived, I am the same within that I am without … I have seen the grass, the blossom, and the fruit, and now see the withering; happily, however, because naturally.

Montaigne’s persistence in assembling his extraordinary dossier of stories, arguments, asides and observations on nearly everything under the sun (from how to parley with an enemy to whether women should be so demure in matters of sex , has been celebrated by admirers in nearly every generation.

Within a decade of his death, his Essays had left their mark on Bacon and Shakespeare. He was a hero to the enlighteners Montesquieu and Diderot. Voltaire celebrated Montaigne - a man educated only by his own reading, his father and his childhood tutors – as “the least methodical of all philosophers, but the wisest and most amiable”. Nietzsche claimed that the very existence of Montaigne’s Essays added to the joy of living in this world.

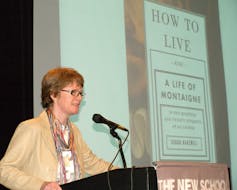

More recently, Sarah Bakewell’s charming engagement with Montaigne, How to Live or a Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (2010) made the best-sellers’ lists. Even today’s initiatives in teaching philosophy in schools can look back to Montaigne (and his “ On the Education of Children ”) as a patron saint or sage .

So what are these Essays, which Montaigne protested were indistinguishable from their author? (“ My book and I go hand in hand together ”).

It’s a good question.

Anyone who tries to read the Essays systematically soon finds themselves overwhelmed by the sheer wealth of examples, anecdotes, digressions and curios Montaigne assembles for our delectation, often without more than the hint of a reason why.

To open the book is to venture into a world in which fortune consistently defies expectations; our senses are as uncertain as our understanding is prone to error; opposites turn out very often to be conjoined (“ the most universal quality is diversity ”); even vice can lead to virtue. Many titles seem to have no direct relation to their contents. Nearly everything our author says in one place is qualified, if not overturned, elsewhere.

Without pretending to untangle all of the knots of this “ book with a wild and desultory plan ”, let me tug here on a couple of Montaigne’s threads to invite and assist new readers to find their own way.

Philosophy (and writing) as a way of life

Some scholars argued that Montaigne began writing his essays as a want-to-be Stoic , hardening himself against the horrors of the French civil and religious wars , and his grief at the loss of his best friend Étienne de La Boétie through dysentery.

Certainly, for Montaigne, as for ancient thinkers led by his favourites, Plutarch and the Roman Stoic Seneca, philosophy was not solely about constructing theoretical systems, writing books and articles. It was what one more recent admirer of Montaigne has called “ a way of life ”.

Montaigne has little time for forms of pedantry that value learning as a means to insulate scholars from the world, rather than opening out onto it. He writes :

Either our reason mocks us or it ought to have no other aim but our contentment.

We are great fools . ‘He has passed over his life in idleness,’ we say: ‘I have done nothing today.’ What? have you not lived? that is not only the fundamental, but the most illustrious of all your occupations.

One feature of the Essays is, accordingly, Montaigne’s fascination with the daily doings of men like Socrates and Cato the Younger ; two of those figures revered amongst the ancients as wise men or “ sages ”.

Their wisdom, he suggests , was chiefly evident in the lives they led (neither wrote a thing). In particular, it was proven by the nobility each showed in facing their deaths. Socrates consented serenely to taking hemlock, having been sentenced unjustly to death by the Athenians. Cato stabbed himself to death after having meditated upon Socrates’ example , in order not to cede to Julius Caesar’s coup d’état .

To achieve such “philosophic” constancy, Montaigne saw, requires a good deal more than book learning . Indeed, everything about our passions and, above all, our imagination , speaks against achieving that perfect tranquillity the classical thinkers saw as the highest philosophical goal.

We discharge our hopes and fears, very often, on the wrong objects, Montaigne notes , in an observation that anticipates the thinking of Freud and modern psychology. Always, these emotions dwell on things we cannot presently change. Sometimes, they inhibit our ability to see and deal in a supple way with the changing demands of life.

Philosophy, in this classical view, involves a retraining of our ways of thinking, seeing and being in the world. Montaigne’s earlier essay “ To philosophise is to learn how to die ” is perhaps the clearest exemplar of his indebtedness to this ancient idea of philosophy.

Yet there is a strong sense in which all of the Essays are a form of what one 20th century author has dubbed “ self-writing ”: an ethical exercise to “strengthen and enlighten” Montaigne’s own judgement, as much as that of we readers:

And though nobody should read me, have I wasted time in entertaining myself so many idle hours in so pleasing and useful thoughts? … I have no more made my book than my book has made me: it is a book consubstantial with the author, of a peculiar design, a parcel of my life …

As for the seeming disorder of the product, and Montaigne’s frequent claims that he is playing the fool , this is arguably one more feature of the Essays that reflects his Socratic irony. Montaigne wants to leave us with some work to do and scope to find our own paths through the labyrinth of his thoughts, or alternatively, to bobble about on their diverting surfaces .

A free-thinking sceptic

Yet Montaigne’s Essays, for all of their classicism and their idiosyncracies, are rightly numbered as one of the founding texts of modern thought . Their author keeps his own prerogatives, even as he bows deferentially before the altars of ancient heroes like Socrates, Cato, Alexander the Great or the Theban general Epaminondas .

There is a good deal of the Christian, Augustinian legacy in Montaigne’s makeup. And of all the philosophers, he most frequently echoes ancient sceptics like Pyrrho or Carneades who argued that we can know almost nothing with certainty. This is especially true concerning the “ultimate questions” the Catholics and Huguenots of Montaigne’s day were bloodily contesting.

Writing in a time of cruel sectarian violence , Montaigne is unconvinced by the ageless claim that having a dogmatic faith is necessary or especially effective in assisting people to love their neighbours :

Between ourselves, I have ever observed supercelestial opinions and subterranean manners to be of singular accord …

This scepticism applies as much to the pagan ideal of a perfected philosophical sage as it does to theological speculations.

Socrates’ constancy before death, Montaigne concludes, was simply too demanding for most people, almost superhuman . As for Cato’s proud suicide, Montaigne takes liberty to doubt whether it was as much the product of Stoic tranquility, as of a singular turn of mind that could take pleasure in such extreme virtue .

Indeed when it comes to his essays “ Of Moderation ” or “ Of Virtue ”, Montaigne quietly breaks the ancient mold. Instead of celebrating the feats of the world’s Catos or Alexanders, here he lists example after example of people moved by their sense of transcendent self-righteousness to acts of murderous or suicidal excess.

Even virtue can become vicious, these essays imply, unless we know how to moderate our own presumptions.

Of cannibals and cruelties

If there is one form of argument Montaigne uses most often, it is the sceptical argument drawing on the disagreement amongst even the wisest authorities.

If human beings could know if, say, the soul was immortal, with or without the body, or dissolved when we die … then the wisest people would all have come to the same conclusions by now, the argument goes. Yet even the “most knowing” authorities disagree about such things, Montaigne delights in showing us .

The existence of such “ an infinite confusion ” of opinions and customs ceases to be the problem, for Montaigne. It points the way to a new kind of solution, and could in fact enlighten us.

Documenting such manifold differences between customs and opinions is, for him, an education in humility :

Manners and opinions contrary to mine do not so much displease as instruct me; nor so much make me proud as they humble me.

His essay “ Of Cannibals ” for instance, presents all of the different aspects of American Indian culture, as known to Montaigne through travellers’ reports then filtering back into Europe. For the most part, he finds these “savages’” society ethically equal, if not far superior, to that of war-torn France’s — a perspective that Voltaire and Rousseau would echo nearly 200 years later.

We are horrified at the prospect of eating our ancestors. Yet Montaigne imagines that from the Indians’ perspective, Western practices of cremating our deceased, or burying their bodies to be devoured by the worms must seem every bit as callous.

And while we are at it, Montaigne adds that consuming people after they are dead seems a good deal less cruel and inhumane than torturing folk we don’t even know are guilty of any crime whilst they are still alive …

A gay and sociable wisdom

“So what is left then?”, the reader might ask, as Montaigne undermines one presumption after another, and piles up exceptions like they had become the only rule.

A very great deal , is the answer. With metaphysics, theology, and the feats of godlike sages all under a “ suspension of judgment ”, we become witnesses as we read the Essays to a key document in the modern revaluation and valorization of everyday life.

There is, for instance, Montaigne’s scandalously demotic habit of interlacing words, stories and actions from his neighbours, the local peasants (and peasant women) with examples from the greats of Christian and pagan history. As he writes :

I have known in my time a hundred artisans, a hundred labourers, wiser and more happy than the rectors of the university, and whom I had much rather have resembled.

By the end of the Essays, Montaigne has begun openly to suggest that, if tranquillity, constancy, bravery, and honour are the goals the wise hold up for us, they can all be seen in much greater abundance amongst the salt of the earth than amongst the rich and famous:

I propose a life ordinary and without lustre: ‘tis all one … To enter a breach, conduct an embassy, govern a people, are actions of renown; to … laugh, sell, pay, love, hate, and gently and justly converse with our own families and with ourselves … not to give our selves the lie, that is rarer, more difficult and less remarkable …

And so we arrive with these last Essays at a sentiment better known today from another philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, the author of A Gay Science (1882) .

Montaigne’s closing essays repeat the avowal that: “ I love a gay and civil wisdom … .” But in contrast to his later Germanic admirer, the music here is less Wagner or Beethoven than it is Mozart (as it were), and Montaigne’s spirit much less agonised than gently serene.

It was Voltaire, again, who said that life is a tragedy for those who feel, and a comedy for those who think. Montaigne adopts and admires the comic perspective . As he writes in “Of Experience”:

It is not of much use to go upon stilts , for, when upon stilts, we must still walk with our legs; and when seated upon the most elevated throne in the world, we are still perched on our own bums.

- Classic literature

- Michel de Montaigne

Research Fellow Virology

Integrated Management of Invasive Pampas Grass for Enhanced Land Rehabilitation

Economics Editor

Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Strategy and Services)

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.) numbers among the greatest philosophers of all time. Judged solely in terms of his philosophical influence, only Plato is his peer: Aristotle’s works shaped centuries of philosophy from Late Antiquity through the Renaissance, and even today continue to be studied with keen, non-antiquarian interest. A prodigious researcher and writer, Aristotle left a great body of work, perhaps numbering as many as two-hundred treatises, from which approximately thirty-one survive. [ 1 ] His extant writings span a wide range of disciplines, from logic, metaphysics and philosophy of mind, through ethics, political theory, aesthetics and rhetoric, and into such primarily non-philosophical fields as empirical biology, where he excelled at detailed plant and animal observation and description. In all these areas, Aristotle’s theories have provided illumination, met with resistance, sparked debate, and generally stimulated the sustained interest of an abiding readership.

Because of its wide range and its remoteness in time, Aristotle’s philosophy defies easy encapsulation. The long history of interpretation and appropriation of Aristotelian texts and themes—spanning over two millennia and comprising philosophers working within a variety of religious and secular traditions—has rendered even basic points of interpretation controversial. The set of entries on Aristotle in this site addresses this situation by proceeding in three tiers. First, the present, general entry offers a brief account of Aristotle’s life and characterizes his central philosophical commitments, highlighting his most distinctive methods and most influential achievements. [ 2 ] Second are General Topics , which offer detailed introductions to the main areas of Aristotle’s philosophical activity. Finally, there follow Special Topics , which investigate in greater detail more narrowly focused issues, especially those of central concern in recent Aristotelian scholarship.

1. Aristotle’s Life

2. the aristotelian corpus: character and primary divisions, 3. phainomena and the endoxic method, 4.2 science, 4.3 dialectic, 5. essentialism and homonymy, 6. category theory, 7. the four causal account of explanatory adequacy, 8. hylomorphism, 9. aristotelian teleology, 10. substance, 11. living beings, 12. happiness and political association, 13. rhetoric and the arts, 14. aristotle’s legacy, a. translations, b. translations with commentaries, c. general works, d. bibliography of works cited, other internet resources, related entries.

Born in 384 B.C.E. in the Macedonian region of northeastern Greece in the small city of Stagira (whence the moniker ‘the Stagirite’, which one still occasionally encounters in Aristotelian scholarship), Aristotle was sent to Athens at about the age of seventeen to study in Plato’s Academy, then a pre-eminent place of learning in the Greek world. Once in Athens, Aristotle remained associated with the Academy until Plato’s death in 347, at which time he left for Assos, in Asia Minor, on the northwest coast of present-day Turkey. There he continued the philosophical activity he had begun in the Academy, but in all likelihood also began to expand his researches into marine biology. He remained at Assos for approximately three years, when, evidently upon the death of his host Hermeias, a friend and former Academic who had been the ruler of Assos, Aristotle moved to the nearby coastal island of Lesbos. There he continued his philosophical and empirical researches for an additional two years, working in conjunction with Theophrastus, a native of Lesbos who was also reported in antiquity to have been associated with Plato’s Academy. While in Lesbos, Aristotle married Pythias, the niece of Hermeias, with whom he had a daughter, also named Pythias.

In 343, upon the request of Philip, the king of Macedon, Aristotle left Lesbos for Pella, the Macedonian capital, in order to tutor the king’s thirteen-year-old son, Alexander—the boy who was eventually to become Alexander the Great. Although speculation concerning Aristotle’s influence upon the developing Alexander has proven irresistible to historians, in fact little concrete is known about their interaction. On the balance, it seems reasonable to conclude that some tuition took place, but that it lasted only two or three years, when Alexander was aged from thirteen to fifteen. By fifteen, Alexander was apparently already serving as a deputy military commander for his father, a circumstance undermining, if inconclusively, the judgment of those historians who conjecture a longer period of tuition. Be that as it may, some suppose that their association lasted as long as eight years.

It is difficult to rule out that possibility decisively, since little is known about the period of Aristotle’s life from 341–335. He evidently remained a further five years in Stagira or Macedon before returning to Athens for the second and final time, in 335. In Athens, Aristotle set up his own school in a public exercise area dedicated to the god Apollo Lykeios, whence its name, the Lyceum . Those affiliated with Aristotle’s school later came to be called Peripatetics , probably because of the existence of an ambulatory ( peripatos ) on the school’s property adjacent to the exercise ground. Members of the Lyceum conducted research into a wide range of subjects, all of which were of interest to Aristotle himself: botany, biology, logic, music, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, cosmology, physics, the history of philosophy, metaphysics, psychology, ethics, theology, rhetoric, political history, government and political theory, and the arts. In all these areas, the Lyceum collected manuscripts, thereby, according to some ancient accounts, assembling the first great library of antiquity.

During this period, Aristotle’s wife, Pythias, died and he developed a new relationship with Herpyllis, perhaps like him a native of Stagira, though her origins are disputed, as is the question of her exact relationship to Aristotle. Some suppose that she was merely his slave; others infer from the provisions of Aristotle’s will that she was a freed woman and likely his wife at the time of his death. In any event, they had children together, including a son, Nicomachus, named for Aristotle’s father and after whom his Nicomachean Ethics is presumably named.

After thirteen years in Athens, Aristotle once again found cause to retire from the city, in 323. Probably his departure was occasioned by a resurgence of the always-simmering anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens, which was free to come to the boil after Alexander succumbed to disease in Babylon during that same year. Because of his connections to Macedon, Aristotle reasonably feared for his safety and left Athens, remarking, as an oft-repeated ancient tale would tell it, that he saw no reason to permit Athens to sin twice against philosophy. He withdrew directly to Chalcis, on Euboea, an island off the Attic coast, and died there of natural causes the following year, in 322. [ 3 ]

Aristotle’s writings tend to present formidable difficulties to his novice readers. To begin, he makes heavy use of unexplained technical terminology, and his sentence structure can at times prove frustrating. Further, on occasion a chapter or even a full treatise coming down to us under his name appears haphazardly organized, if organized at all; indeed, in several cases, scholars dispute whether a continuous treatise currently arranged under a single title was ever intended by Aristotle to be published in its present form or was rather stitched together by some later editor employing whatever principles of organization he deemed suitable. [ 4 ] This helps explain why students who turn to Aristotle after first being introduced to the supple and mellifluous prose on display in Plato’s dialogues often find the experience frustrating. Aristotle’s prose requires some acclimatization.

All the more puzzling, then, is Cicero’s observation that if Plato’s prose was silver, Aristotle’s was a flowing river of gold ( Ac. Pr. 38.119, cf. Top . 1.3, De or. 1.2.49). Cicero was arguably the greatest prose stylist of Latin and was also without question an accomplished and fair-minded critic of the prose styles of others writing in both Latin and Greek. We must assume, then, that Cicero had before him works of Aristotle other than those we possess. In fact, we know that Aristotle wrote dialogues, presumably while still in the Academy, and in their few surviving remnants we are afforded a glimpse of the style Cicero describes. In most of what we possess, unfortunately, we find work of a much less polished character. Rather, Aristotle’s extant works read like what they very probably are: lecture notes, drafts first written and then reworked, ongoing records of continuing investigations, and, generally speaking, in-house compilations intended not for a general audience but for an inner circle of auditors. These are to be contrasted with the “exoteric” writings Aristotle sometimes mentions, his more graceful compositions intended for a wider audience ( Pol. 1278b30; EE 1217b22, 1218b34). Unfortunately, then, we are left for the most part, though certainly not entirely, with unfinished works in progress rather than with finished and polished productions. Still, many of those who persist with Aristotle come to appreciate the unembellished directness of his style.

More importantly, the unvarnished condition of Aristotle’s surviving treatises does not hamper our ability to come to grips with their philosophical content. His thirty-one surviving works (that is, those contained in the “Corpus Aristotelicum” of our medieval manuscripts that are judged to be authentic) all contain recognizably Aristotelian doctrine; and most of these contain theses whose basic purport is clear, even where matters of detail and nuance are subject to exegetical controversy.

These works may be categorized in terms of the intuitive organizational principles preferred by Aristotle. He refers to the branches of learning as “sciences” ( epistêmai ), best regarded as organized bodies of learning completed for presentation rather than as ongoing records of empirical researches. Moreover, again in his terminology, natural sciences such as physics are but one branch of theoretical science , which comprises both empirical and non-empirical pursuits. He distinguishes theoretical science from more practically oriented studies, some of which concern human conduct and others of which focus on the productive crafts. Thus, the Aristotelian sciences divide into three: (i) theoretical, (ii) practical, and (iii) productive. The principles of division are straightforward: theoretical science seeks knowledge for its own sake; practical science concerns conduct and goodness in action, both individual and societal; and productive science aims at the creation of beautiful or useful objects ( Top . 145a15–16; Phys . 192b8–12; DC 298a27–32, DA 403a27–b2; Met. 1025b25, 1026a18–19, 1064a16–19, b1–3; EN 1139a26–28, 1141b29–32).

(i) The theoretical sciences include prominently what Aristotle calls first philosophy , or metaphysics as we now call it, but also mathematics , and physics , or natural philosophy. Physics studies the natural universe as a whole, and tends in Aristotle’s hands to concentrate on conceptual puzzles pertaining to nature rather than on empirical research; but it reaches further, so that it includes also a theory of causal explanation and finally even a proof of an unmoved mover thought to be the first and final cause of all motion. Many of the puzzles of primary concern to Aristotle have proven perennially attractive to philosophers, mathematicians, and theoretically inclined natural scientists. They include, as a small sample, Zeno’s paradoxes of motion, puzzles about time, the nature of place, and difficulties encountered in thought about the infinite.

Natural philosophy also incorporates the special sciences, including biology, botany, and astronomical theory. Most contemporary critics think that Aristotle treats psychology as a sub-branch of natural philosophy, because he regards the soul ( psuchê ) as the basic principle of life, including all animal and plant life. In fact, however, the evidence for this conclusion is inconclusive at best. It is instructive to note that earlier periods of Aristotelian scholarship thought this controversial, so that, for instance, even something as innocuous-sounding as the question of the proper home of psychology in Aristotle’s division of the sciences ignited a multi-decade debate in the Renaissance. [ 5 ]

(ii) Practical sciences are less contentious, at least as regards their range. These deal with conduct and action, both individual and societal. Practical science thus contrasts with theoretical science, which seeks knowledge for its own sake, and, less obviously, with the productive sciences, which deal with the creation of products external to sciences themselves. Both politics and ethics fall under this branch.

(iii) Finally, then, the productive sciences are mainly crafts aimed at the production of artefacts, or of human productions more broadly construed. The productive sciences include, among others, ship-building, agriculture, and medicine, but also the arts of music, theatre, and dance. Another form of productive science is rhetoric, which treats the principles of speech-making appropriate to various forensic and persuasive settings, including centrally political assemblies.

Significantly, Aristotle’s tri-fold division of the sciences makes no mention of logic. Although he did not use the word ‘logic’ in our sense of the term, Aristotle in fact developed the first formalized system of logic and valid inference. In Aristotle’s framework—although he is nowhere explicit about this—logic belongs to no one science, but rather formulates the principles of correct argumentation suitable to all areas of inquiry in common. It systematizes the principles licensing acceptable inference, and helps to highlight at an abstract level seductive patterns of incorrect inference to be avoided by anyone with a primary interest in truth. So, alongside his more technical work in logic and logical theory, Aristotle investigates informal styles of argumentation and seeks to expose common patterns of fallacious reasoning.

Aristotle’s investigations into logic and the forms of argumentation make up part of the group of works coming down to us from the Middle Ages under the heading the Organon ( organon = tool in Greek). Although not so characterized in these terms by Aristotle, the name is apt, so long as it is borne in mind that intellectual inquiry requires a broad range of tools. Thus, in addition to logic and argumentation (treated primarily in the Prior Analytics and Topics ), the works included in the Organon deal with category theory, the doctrine of propositions and terms, the structure of scientific theory, and to some extent the basic principles of epistemology.

When we slot Aristotle’s most important surviving authentic works into this scheme, we end up with the following basic divisions of his major writings:

- Categories ( Cat .)

- De Interpretatione ( DI ) [ On Interpretation ]

- Prior Analytics ( APr )

- Posterior Analytics ( APo )

- Topics ( Top .)

- Sophistical Refutations ( SE )

- Physics ( Phys .)

- Generation and Corruption ( Gen. et Corr .)

- De Caelo ( DC ) [ On the Heavens ]

- Metaphysics ( Met .)

- De Anima ( DA ) [ On the Soul ]

- Parva Naturalia ( PN ) [ Brief Natural Treatises ]

- History of Animals ( HA )

- Parts of Animals ( PA )

- Movement of Animals ( MA )

- Meteorology ( Meteor .)

- Progression of Animals ( IA )

- Generation of Animals ( GA )

- Nicomachean Ethics ( EN )

- Eudemian Ethics ( EE )

- Magna Moralia ( MM ) [ Great Ethics ]

- Politics ( Pol .)

- Rhetoric ( Rhet .)

- Poetics ( Poet .)

The titles in this list are those in most common use today in English-language scholarship, followed by standard abbreviations in parentheses. For no discernible reason, Latin titles are customarily employed in some cases, English in others. Where Latin titles are in general use, English equivalents are given in square brackets.

Aristotle’s basic approach to philosophy is best grasped initially by way of contrast. Whereas Descartes seeks to place philosophy and science on firm foundations by subjecting all knowledge claims to a searing methodological doubt, Aristotle begins with the conviction that our perceptual and cognitive faculties are basically dependable, that they for the most part put us into direct contact with the features and divisions of our world, and that we need not dally with sceptical postures before engaging in substantive philosophy. Accordingly, he proceeds in all areas of inquiry in the manner of a modern-day natural scientist, who takes it for granted that progress follows the assiduous application of a well-trained mind and so, when presented with a problem, simply goes to work. When he goes to work, Aristotle begins by considering how the world appears, reflecting on the puzzles those appearances throw up, and reviewing what has been said about those puzzles to date. These methods comprise his twin appeals to phainomena and the endoxic method.

These two methods reflect in different ways Aristotle’s deepest motivations for doing philosophy in the first place. “Human beings began to do philosophy,” he says, “even as they do now, because of wonder, at first because they wondered about the strange things right in front of them, and then later, advancing little by little, because they came to find greater things puzzling” ( Met. 982b12). Human beings philosophize, according to Aristotle, because they find aspects of their experience puzzling. The sorts of puzzles we encounter in thinking about the universe and our place within it— aporiai , in Aristotle’s terminology—tax our understanding and induce us to philosophize.

According to Aristotle, it behooves us to begin philosophizing by laying out the phainomena , the appearances , or, more fully, things appearing to be the case , and then also collecting the endoxa , the credible opinions handed down regarding matters we find puzzling. As a typical example, in a passage of his Nicomachean Ethics , Aristotle confronts a puzzle of human conduct, the fact that we are apparently sometimes akratic or weak-willed. When introducing this puzzle, Aristotle pauses to reflect upon a precept governing his approach to many areas of inquiry:

As in other cases, we must set out the appearances ( phainomena ) and run through all the puzzles regarding them. In this way we must prove the credible opinions ( endoxa ) about these sorts of experiences—ideally, all the credible opinions, but if not all, then most of them, those which are the most important. For if the objections are answered and the credible opinions remain, we shall have an adequate proof. ( EN 1145b2–7)

Scholars dispute concerning the degree to which Aristotle regards himself as beholden to the credible opinions ( endoxa ) he recounts and the basic appearances ( phainomena ) to which he appeals. [ 6 ] Of course, since the endoxa will sometimes conflict with one another, often precisely because the phainomena generate aporiai , or puzzles, it is not always possible to respect them in their entirety. So, as a group they must be re-interpreted and systematized, and, where that does not suffice, some must be rejected outright. It is in any case abundantly clear that Aristotle is willing to abandon some or all of the endoxa and phainomena whenever science or philosophy demands that he do so ( Met. 1073b36, 1074b6; PA 644b5; EN 1145b2–30).

Still, his attitude towards phainomena does betray a preference to conserve as many appearances as is practicable in a given domain—not because the appearances are unassailably accurate, but rather because, as he supposes, appearances tend to track the truth. We are outfitted with sense organs and powers of mind so structured as to put us into contact with the world and thus to provide us with data regarding its basic constituents and divisions. While our faculties are not infallible, neither are they systematically deceptive or misdirecting. Since philosophy’s aim is truth and much of what appears to us proves upon analysis to be correct, phainomena provide both an impetus to philosophize and a check on some of its more extravagant impulses.

Of course, it is not always clear what constitutes a phainomenon ; still less is it clear which phainomenon is to be respected in the face of bona fide disagreement. This is in part why Aristotle endorses his second and related methodological precept, that we ought to begin philosophical discussions by collecting the most stable and entrenched opinions regarding the topic of inquiry handed down to us by our predecessors. Aristotle’s term for these privileged views, endoxa , is variously rendered as ‘reputable opinions’, ‘credible opinions’, ‘entrenched beliefs’, ‘credible beliefs’, or ‘common beliefs’. Each of these translations captures at least part of what Aristotle intends with this word, but it is important to appreciate that it is a fairly technical term for him. An endoxon is the sort of opinion we spontaneously regard as reputable or worthy of respect, even if upon reflection we may come to question its veracity. (Aristotle appropriates this term from ordinary Greek, in which an endoxos is a notable or honourable man, a man of high repute whom we would spontaneously respect—though we might, of course, upon closer inspection, find cause to criticize him.) As he explains his use of the term, endoxa are widely shared opinions, often ultimately issuing from those we esteem most: ‘ Endoxa are those opinions accepted by everyone, or by the majority, or by the wise—and among the wise, by all or most of them, or by those who are the most notable and having the highest reputation’ ( Top. 100b21–23). Endoxa play a special role in Aristotelian philosophy in part because they form a significant sub-class of phainomena ( EN 1154b3–8): because they are the privileged opinions we find ourselves unreflectively endorsing and reaffirming after some reflection, they themselves come to qualify as appearances to be preserved where possible.