Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

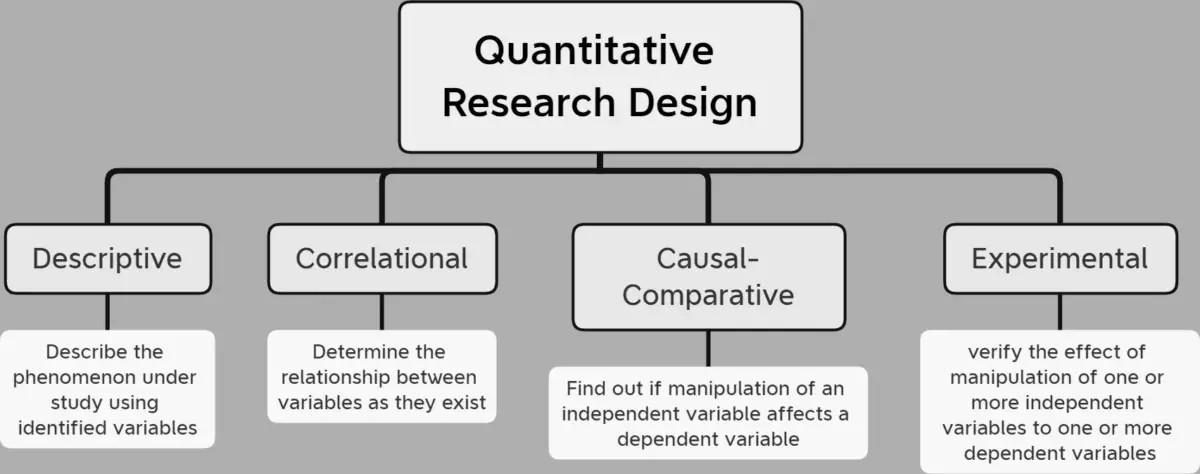

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

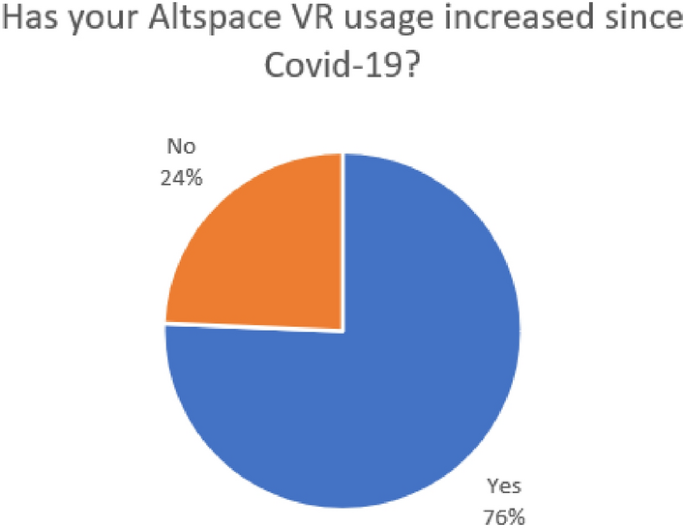

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Quantitative Research

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 13 January 2019

- Cite this reference work entry

- Leigh A. Wilson 2 , 3

4341 Accesses

4 Citations

Quantitative research methods are concerned with the planning, design, and implementation of strategies to collect and analyze data. Descartes, the seventeenth-century philosopher, suggested that how the results are achieved is often more important than the results themselves, as the journey taken along the research path is a journey of discovery. High-quality quantitative research is characterized by the attention given to the methods and the reliability of the tools used to collect the data. The ability to critique research in a systematic way is an essential component of a health professional’s role in order to deliver high quality, evidence-based healthcare. This chapter is intended to provide a simple overview of the way new researchers and health practitioners can understand and employ quantitative methods. The chapter offers practical, realistic guidance in a learner-friendly way and uses a logical sequence to understand the process of hypothesis development, study design, data collection and handling, and finally data analysis and interpretation.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Babbie ER. The practice of social research. 14th ed. Belmont: Wadsworth Cengage; 2016.

Google Scholar

Descartes. Cited in Halverston, W. (1976). In: A concise introduction to philosophy, 3rd ed. New York: Random House; 1637.

Doll R, Hill AB. The mortality of doctors in relation to their smoking habits. BMJ. 1954;328(7455):1529–33. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1529 .

Article Google Scholar

Liamputtong P. Research methods in health: foundations for evidence-based practice. 3rd ed. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2017.

McNabb DE. Research methods in public administration and nonprofit management: quantitative and qualitative approaches. 2nd ed. New York: Armonk; 2007.

Merriam-Webster. Dictionary. http://www.merriam-webster.com . Accessed 20th December 2017.

Olesen Larsen P, von Ins M. The rate of growth in scientific publication and the decline in coverage provided by Science Citation Index. Scientometrics. 2010;84(3):575–603.

Pannucci CJ, Wilkins EG. Identifying and avoiding bias in research. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(2):619–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181de24bc .

Petrie A, Sabin C. Medical statistics at a glance. 2nd ed. London: Blackwell Publishing; 2005.

Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Pearson Publishing; 2009.

Sheehan J. Aspects of research methodology. Nurse Educ Today. 1986;6:193–203.

Wilson LA, Black DA. Health, science research and research methods. Sydney: McGraw Hill; 2013.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Leigh A. Wilson

Faculty of Health Science, Discipline of Behavioural and Social Sciences in Health, University of Sydney, Lidcombe, NSW, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Leigh A. Wilson .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Pranee Liamputtong

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Wilson, L.A. (2019). Quantitative Research. In: Liamputtong, P. (eds) Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_54

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_54

Published : 13 January 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-10-5250-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-10-5251-4

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Research Design 101

Everything You Need To Get Started (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewers: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | April 2023

Navigating the world of research can be daunting, especially if you’re a first-time researcher. One concept you’re bound to run into fairly early in your research journey is that of “ research design ”. Here, we’ll guide you through the basics using practical examples , so that you can approach your research with confidence.

Overview: Research Design 101

What is research design.

- Research design types for quantitative studies

- Video explainer : quantitative research design

- Research design types for qualitative studies

- Video explainer : qualitative research design

- How to choose a research design

- Key takeaways

Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project , from its conception to the final data analysis. A good research design serves as the blueprint for how you, as the researcher, will collect and analyse data while ensuring consistency, reliability and validity throughout your study.

Understanding different types of research designs is essential as helps ensure that your approach is suitable given your research aims, objectives and questions , as well as the resources you have available to you. Without a clear big-picture view of how you’ll design your research, you run the risk of potentially making misaligned choices in terms of your methodology – especially your sampling , data collection and data analysis decisions.

The problem with defining research design…

One of the reasons students struggle with a clear definition of research design is because the term is used very loosely across the internet, and even within academia.

Some sources claim that the three research design types are qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods , which isn’t quite accurate (these just refer to the type of data that you’ll collect and analyse). Other sources state that research design refers to the sum of all your design choices, suggesting it’s more like a research methodology . Others run off on other less common tangents. No wonder there’s confusion!

In this article, we’ll clear up the confusion. We’ll explain the most common research design types for both qualitative and quantitative research projects, whether that is for a full dissertation or thesis, or a smaller research paper or article.

Research Design: Quantitative Studies

Quantitative research involves collecting and analysing data in a numerical form. Broadly speaking, there are four types of quantitative research designs: descriptive , correlational , experimental , and quasi-experimental .

Descriptive Research Design

As the name suggests, descriptive research design focuses on describing existing conditions, behaviours, or characteristics by systematically gathering information without manipulating any variables. In other words, there is no intervention on the researcher’s part – only data collection.

For example, if you’re studying smartphone addiction among adolescents in your community, you could deploy a survey to a sample of teens asking them to rate their agreement with certain statements that relate to smartphone addiction. The collected data would then provide insight regarding how widespread the issue may be – in other words, it would describe the situation.

The key defining attribute of this type of research design is that it purely describes the situation . In other words, descriptive research design does not explore potential relationships between different variables or the causes that may underlie those relationships. Therefore, descriptive research is useful for generating insight into a research problem by describing its characteristics . By doing so, it can provide valuable insights and is often used as a precursor to other research design types.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational design is a popular choice for researchers aiming to identify and measure the relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them . In other words, this type of research design is useful when you want to know whether a change in one thing tends to be accompanied by a change in another thing.

For example, if you wanted to explore the relationship between exercise frequency and overall health, you could use a correlational design to help you achieve this. In this case, you might gather data on participants’ exercise habits, as well as records of their health indicators like blood pressure, heart rate, or body mass index. Thereafter, you’d use a statistical test to assess whether there’s a relationship between the two variables (exercise frequency and health).

As you can see, correlational research design is useful when you want to explore potential relationships between variables that cannot be manipulated or controlled for ethical, practical, or logistical reasons. It is particularly helpful in terms of developing predictions , and given that it doesn’t involve the manipulation of variables, it can be implemented at a large scale more easily than experimental designs (which will look at next).

That said, it’s important to keep in mind that correlational research design has limitations – most notably that it cannot be used to establish causality . In other words, correlation does not equal causation . To establish causality, you’ll need to move into the realm of experimental design, coming up next…

Need a helping hand?

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research design is used to determine if there is a causal relationship between two or more variables . With this type of research design, you, as the researcher, manipulate one variable (the independent variable) while controlling others (dependent variables). Doing so allows you to observe the effect of the former on the latter and draw conclusions about potential causality.

For example, if you wanted to measure if/how different types of fertiliser affect plant growth, you could set up several groups of plants, with each group receiving a different type of fertiliser, as well as one with no fertiliser at all. You could then measure how much each plant group grew (on average) over time and compare the results from the different groups to see which fertiliser was most effective.

Overall, experimental research design provides researchers with a powerful way to identify and measure causal relationships (and the direction of causality) between variables. However, developing a rigorous experimental design can be challenging as it’s not always easy to control all the variables in a study. This often results in smaller sample sizes , which can reduce the statistical power and generalisability of the results.

Moreover, experimental research design requires random assignment . This means that the researcher needs to assign participants to different groups or conditions in a way that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group (note that this is not the same as random sampling ). Doing so helps reduce the potential for bias and confounding variables . This need for random assignment can lead to ethics-related issues . For example, withholding a potentially beneficial medical treatment from a control group may be considered unethical in certain situations.

Quasi-Experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is used when the research aims involve identifying causal relations , but one cannot (or doesn’t want to) randomly assign participants to different groups (for practical or ethical reasons). Instead, with a quasi-experimental research design, the researcher relies on existing groups or pre-existing conditions to form groups for comparison.

For example, if you were studying the effects of a new teaching method on student achievement in a particular school district, you may be unable to randomly assign students to either group and instead have to choose classes or schools that already use different teaching methods. This way, you still achieve separate groups, without having to assign participants to specific groups yourself.

Naturally, quasi-experimental research designs have limitations when compared to experimental designs. Given that participant assignment is not random, it’s more difficult to confidently establish causality between variables, and, as a researcher, you have less control over other variables that may impact findings.

All that said, quasi-experimental designs can still be valuable in research contexts where random assignment is not possible and can often be undertaken on a much larger scale than experimental research, thus increasing the statistical power of the results. What’s important is that you, as the researcher, understand the limitations of the design and conduct your quasi-experiment as rigorously as possible, paying careful attention to any potential confounding variables .

Research Design: Qualitative Studies

There are many different research design types when it comes to qualitative studies, but here we’ll narrow our focus to explore the “Big 4”. Specifically, we’ll look at phenomenological design, grounded theory design, ethnographic design, and case study design.

Phenomenological Research Design

Phenomenological design involves exploring the meaning of lived experiences and how they are perceived by individuals. This type of research design seeks to understand people’s perspectives , emotions, and behaviours in specific situations. Here, the aim for researchers is to uncover the essence of human experience without making any assumptions or imposing preconceived ideas on their subjects.

For example, you could adopt a phenomenological design to study why cancer survivors have such varied perceptions of their lives after overcoming their disease. This could be achieved by interviewing survivors and then analysing the data using a qualitative analysis method such as thematic analysis to identify commonalities and differences.

Phenomenological research design typically involves in-depth interviews or open-ended questionnaires to collect rich, detailed data about participants’ subjective experiences. This richness is one of the key strengths of phenomenological research design but, naturally, it also has limitations. These include potential biases in data collection and interpretation and the lack of generalisability of findings to broader populations.

Grounded Theory Research Design

Grounded theory (also referred to as “GT”) aims to develop theories by continuously and iteratively analysing and comparing data collected from a relatively large number of participants in a study. It takes an inductive (bottom-up) approach, with a focus on letting the data “speak for itself”, without being influenced by preexisting theories or the researcher’s preconceptions.

As an example, let’s assume your research aims involved understanding how people cope with chronic pain from a specific medical condition, with a view to developing a theory around this. In this case, grounded theory design would allow you to explore this concept thoroughly without preconceptions about what coping mechanisms might exist. You may find that some patients prefer cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) while others prefer to rely on herbal remedies. Based on multiple, iterative rounds of analysis, you could then develop a theory in this regard, derived directly from the data (as opposed to other preexisting theories and models).

Grounded theory typically involves collecting data through interviews or observations and then analysing it to identify patterns and themes that emerge from the data. These emerging ideas are then validated by collecting more data until a saturation point is reached (i.e., no new information can be squeezed from the data). From that base, a theory can then be developed .

As you can see, grounded theory is ideally suited to studies where the research aims involve theory generation , especially in under-researched areas. Keep in mind though that this type of research design can be quite time-intensive , given the need for multiple rounds of data collection and analysis.

Ethnographic Research Design

Ethnographic design involves observing and studying a culture-sharing group of people in their natural setting to gain insight into their behaviours, beliefs, and values. The focus here is on observing participants in their natural environment (as opposed to a controlled environment). This typically involves the researcher spending an extended period of time with the participants in their environment, carefully observing and taking field notes .

All of this is not to say that ethnographic research design relies purely on observation. On the contrary, this design typically also involves in-depth interviews to explore participants’ views, beliefs, etc. However, unobtrusive observation is a core component of the ethnographic approach.

As an example, an ethnographer may study how different communities celebrate traditional festivals or how individuals from different generations interact with technology differently. This may involve a lengthy period of observation, combined with in-depth interviews to further explore specific areas of interest that emerge as a result of the observations that the researcher has made.

As you can probably imagine, ethnographic research design has the ability to provide rich, contextually embedded insights into the socio-cultural dynamics of human behaviour within a natural, uncontrived setting. Naturally, however, it does come with its own set of challenges, including researcher bias (since the researcher can become quite immersed in the group), participant confidentiality and, predictably, ethical complexities . All of these need to be carefully managed if you choose to adopt this type of research design.

Case Study Design

With case study research design, you, as the researcher, investigate a single individual (or a single group of individuals) to gain an in-depth understanding of their experiences, behaviours or outcomes. Unlike other research designs that are aimed at larger sample sizes, case studies offer a deep dive into the specific circumstances surrounding a person, group of people, event or phenomenon, generally within a bounded setting or context .

As an example, a case study design could be used to explore the factors influencing the success of a specific small business. This would involve diving deeply into the organisation to explore and understand what makes it tick – from marketing to HR to finance. In terms of data collection, this could include interviews with staff and management, review of policy documents and financial statements, surveying customers, etc.

While the above example is focused squarely on one organisation, it’s worth noting that case study research designs can have different variation s, including single-case, multiple-case and longitudinal designs. As you can see in the example, a single-case design involves intensely examining a single entity to understand its unique characteristics and complexities. Conversely, in a multiple-case design , multiple cases are compared and contrasted to identify patterns and commonalities. Lastly, in a longitudinal case design , a single case or multiple cases are studied over an extended period of time to understand how factors develop over time.

As you can see, a case study research design is particularly useful where a deep and contextualised understanding of a specific phenomenon or issue is desired. However, this strength is also its weakness. In other words, you can’t generalise the findings from a case study to the broader population. So, keep this in mind if you’re considering going the case study route.

How To Choose A Research Design

Having worked through all of these potential research designs, you’d be forgiven for feeling a little overwhelmed and wondering, “ But how do I decide which research design to use? ”. While we could write an entire post covering that alone, here are a few factors to consider that will help you choose a suitable research design for your study.

Data type: The first determining factor is naturally the type of data you plan to be collecting – i.e., qualitative or quantitative. This may sound obvious, but we have to be clear about this – don’t try to use a quantitative research design on qualitative data (or vice versa)!

Research aim(s) and question(s): As with all methodological decisions, your research aim and research questions will heavily influence your research design. For example, if your research aims involve developing a theory from qualitative data, grounded theory would be a strong option. Similarly, if your research aims involve identifying and measuring relationships between variables, one of the experimental designs would likely be a better option.

Time: It’s essential that you consider any time constraints you have, as this will impact the type of research design you can choose. For example, if you’ve only got a month to complete your project, a lengthy design such as ethnography wouldn’t be a good fit.

Resources: Take into account the resources realistically available to you, as these need to factor into your research design choice. For example, if you require highly specialised lab equipment to execute an experimental design, you need to be sure that you’ll have access to that before you make a decision.

Keep in mind that when it comes to research, it’s important to manage your risks and play as conservatively as possible. If your entire project relies on you achieving a huge sample, having access to niche equipment or holding interviews with very difficult-to-reach participants, you’re creating risks that could kill your project. So, be sure to think through your choices carefully and make sure that you have backup plans for any existential risks. Remember that a relatively simple methodology executed well generally will typically earn better marks than a highly-complex methodology executed poorly.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. Let’s recap by looking at the key takeaways:

- Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project, from its conception to the final analysis of data.

- Research designs for quantitative studies include descriptive , correlational , experimental and quasi-experimenta l designs.

- Research designs for qualitative studies include phenomenological , grounded theory , ethnographic and case study designs.

- When choosing a research design, you need to consider a variety of factors, including the type of data you’ll be working with, your research aims and questions, your time and the resources available to you.

If you need a helping hand with your research design (or any other aspect of your research), check out our private coaching services .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

10 Comments

Is there any blog article explaining more on Case study research design? Is there a Case study write-up template? Thank you.

Thanks this was quite valuable to clarify such an important concept.

Thanks for this simplified explanations. it is quite very helpful.

This was really helpful. thanks

Thank you for your explanation. I think case study research design and the use of secondary data in researches needs to be talked about more in your videos and articles because there a lot of case studies research design tailored projects out there.

Please is there any template for a case study research design whose data type is a secondary data on your repository?

This post is very clear, comprehensive and has been very helpful to me. It has cleared the confusion I had in regard to research design and methodology.

This post is helpful, easy to understand, and deconstructs what a research design is. Thanks

how to cite this page

Thank you very much for the post. It is wonderful and has cleared many worries in my mind regarding research designs. I really appreciate .

how can I put this blog as my reference(APA style) in bibliography part?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3.2 Quantitative Research Designs

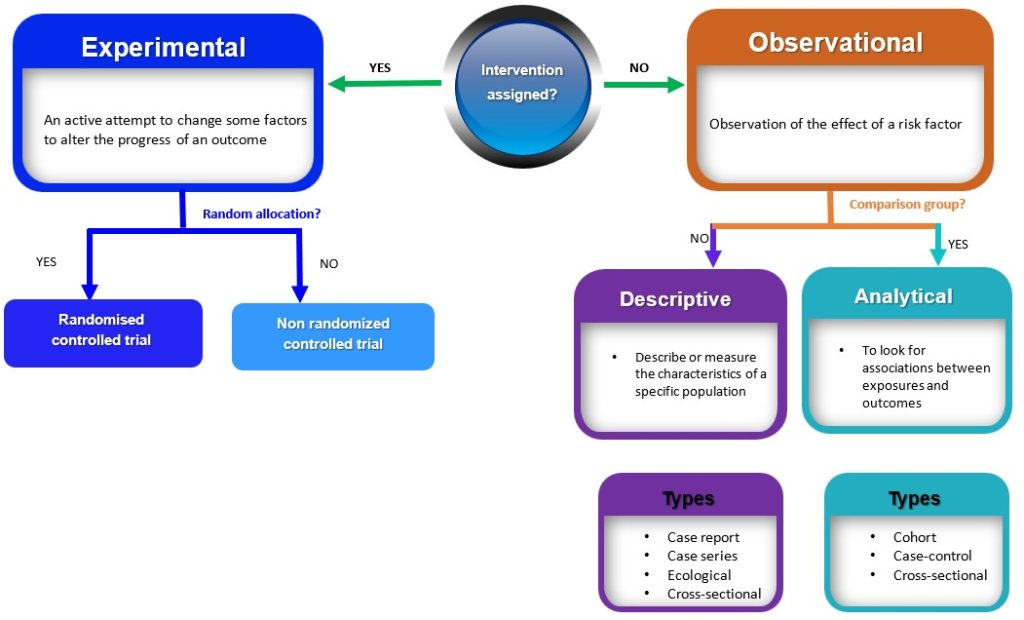

Quantitive research study designs can be broadly classified into two main groups (observational and experimental) depending on if an intervention is assigned. If an intervention is assigned, then an experimental study design will be considered; however, if no intervention is planned or assigned, then an observational study will be conducted. 3 These broad classes are further subdivided into specific study designs, as shown in Figure 3.1. In practice, quantitative studies usually begin simply as descriptive studies, which could subsequently be progressed to more complex analytic studies and then to experimental studies where appropriate.

Observational studies

Observational studies are research designs that involve observing and measuring the characteristics of a sample or population without intervening, altering or manipulating any variables (Figure 3.1). 3 Observational studies can be further subdivided into descriptive and analytic studies. 3

Descriptive observational studies

Descriptive studies are research designs that describe or measure the characteristics of a specific population or phenomenon. These characteristics include descriptions related to the phenomenon under investigation, the people involved, the place, and the time. 4 These study designs are typically non-experimental and do not involve manipulating variables; rather, they rely on the collection and analysis of numerical data to draw conclusions. Examples of descriptive studies include case reports, case series, ecological studies and cross-sectional (prevalence studies). 2 These are discussed below

- Case Reports and Case series

Case reports and case series are both types of descriptive studies in research. A case report is a detailed account of the medical history, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of a single patient. 5 On the other hand, case series is a collection of cases with similar clinical features. 5 Case series are frequently used to explain the natural history of a disease, the clinical characteristics, and the health outcomes for a group of patients who underwent a certain treatment. Case series typically involve a larger number of patients than case reports. 5 Both case reports and case series are used to illustrate unusual or atypical features found in patients in practice. 5 In a typical, real-world clinical situation, they are both used to describe the clinical characteristics and outcomes of individual patients or a group of patients with a particular condition. These studies have the potential to generate new research questions and ideas. 5 However, there are drawbacks to both case reports and case series, such as the absence of control groups and the potential for bias. Yet, they can be useful sources of clinical data, particularly when researching uncommon or recently discovered illnesses. 5 An example of a case report is the study by van Tulleken, Tipton and Haper, 2018 which showed that open-water swimming was used as a treatment for major depressive disorder for a 24-year-old female patient. 6 Weekly open (cold) water swimming was trialled, leading to an immediate improvement in mood following each swim. A sustained and gradual reduction in symptoms of depression, and consequently a reduction in, and cessation of, medication was observed. 6 An example of a case series is the article by Chen et al , 2020 which described the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 infection among 12 confirmed cases in Jilin Province, China. 7

- Ecological studies

Ecological studies examine the relationship between exposure and outcome at the population level. Unlike other epidemiological studies focusing on individual-level data, ecological studies use aggregate data to investigate the relationship between exposure and outcome of interest. 8 In ecological studies, data on prevalence and the degree of exposure to a given risk factor within a population are typically collected and analysed to see if exposure and results are related. 8 Ecological studies shed light on the total burden of disease or health-related events within a population and assist in the identification of potential risk factors that might increase the incidence of disease/event. However, these studies cannot prove causation or take into account characteristics at the individual level that can influence the connection between exposure and result. This implies that ecological findings cannot be interpreted and extrapolated to individuals. 9 For example, the association between urbanisation and Type 2 Diabetes was investigated at the country level, and the role of intermediate variables (physical inactivity, sugar consumption and obesity) was examined. One of the key findings of the study showed that in high-income countries (HIC), physical inactivity and obesity were the main determinants of T2D prevalence. 10 However, it will be wrong to infer that people who are physically inactive and obese in HIC have a higher risk of T2D.

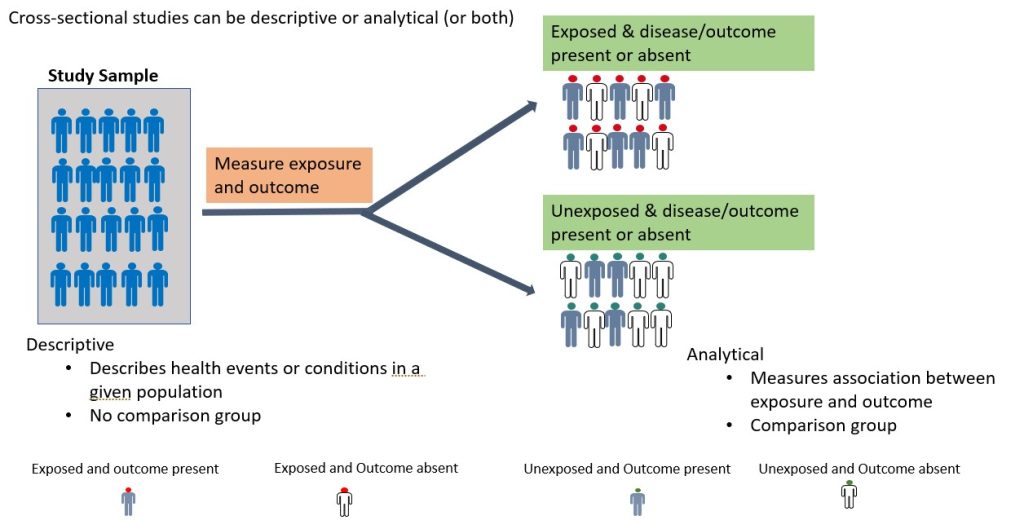

- Cross-sectional Descriptive (Prevalence) studies

A cross-sectional study is an observational study in which the researcher collects data on a group of participants at a single point in time. 11 The goal is to describe the characteristics of the group or to explore relationships between variables. Cross-sectional studies can be either descriptive or analytical (Figure 3.2). 11 Descriptive cross-sectional studies are also known as prevalence studies measuring the proportions of health events or conditions in a given population. 11 Although analytical cross-sectional studies also measure prevalence, however, the relationship between the outcomes and other variables, such as risk factors, is also assessed. 12 The main strength of cross-sectional studies is that they are quick and cost-effective. However, they cannot establish causality and may be vulnerable to bias and confounding ( these concepts will be discussed further later in this chapter under “avoiding error in quantitative research) . An example of a cross-sectional study is the study by Kim et al., 2020 which examined burnout and job stress among physical and occupational therapists in various Korean hospital settings. 13 Findings of the study showed that burnout and work-related stress differed significantly based on several factors, with hospital size, gender, and age as the main contributory factors. The more vulnerable group consisted of female therapists in their 20s at small- or medium-sized hospitals with lower scores for quality of life. 13

Analytical Observational studies

Analytical observational studies aim to establish an association between exposure and outcome and identify causes of disease (causal relationship). 14 Analytical observational studies include analytical cross-sectional ( discussed above ), case-control and cohort studies. 14 This research method could be prospective(cohort study) or retrospective (case-control study), depending on the direction of the enquiry. 14

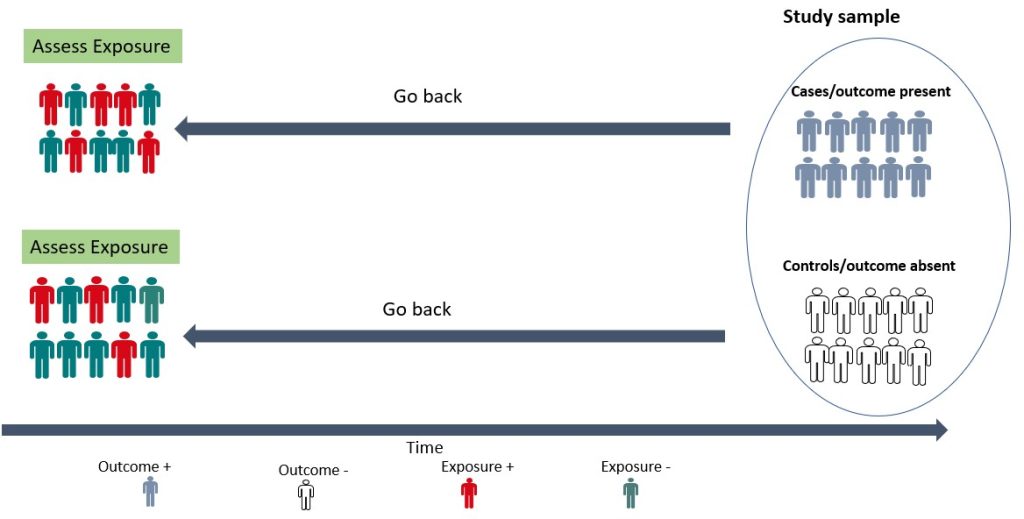

- Case-control studies

A case-control study is a retrospective study in which the researcher compares a group of individuals with a specific outcome (cases) to a group of individuals without that outcome (controls) to identify factors associated with the outcome. 15 As shown in Figure 3.3 below, the cases and controls are recruited and asked questions retrospectively (going back in time) about possible risk factors for the outcome under investigation. A case-control study is relatively efficient in terms of time, money and effort, suited for rare diseases or outcomes with a long latent period, and can examine multiple risk factors. 15 For example, before the cause of lung cancer, was established, a case-control study was conducted by British researchers Richard Doll and Bradford Hill in 1950. 16 Subjects with lung cancer were compared with those who did not have lung cancer, and details about their smoking habits were obtained. 16 The findings from this initial study showed that cancer patients were more frequent and heavy smokers. 16 Over the years, more evidence has been generated implicating tobacco as a significant cause of lung cancer. 17, 18 Case-control studies are, therefore, useful for examining rare outcomes and can be conducted more quickly and with fewer resources than other study designs. Nonetheless, it should be noted that case-control studies are susceptible to bias in selecting cases and controls and may not be representative of the overall population. 15

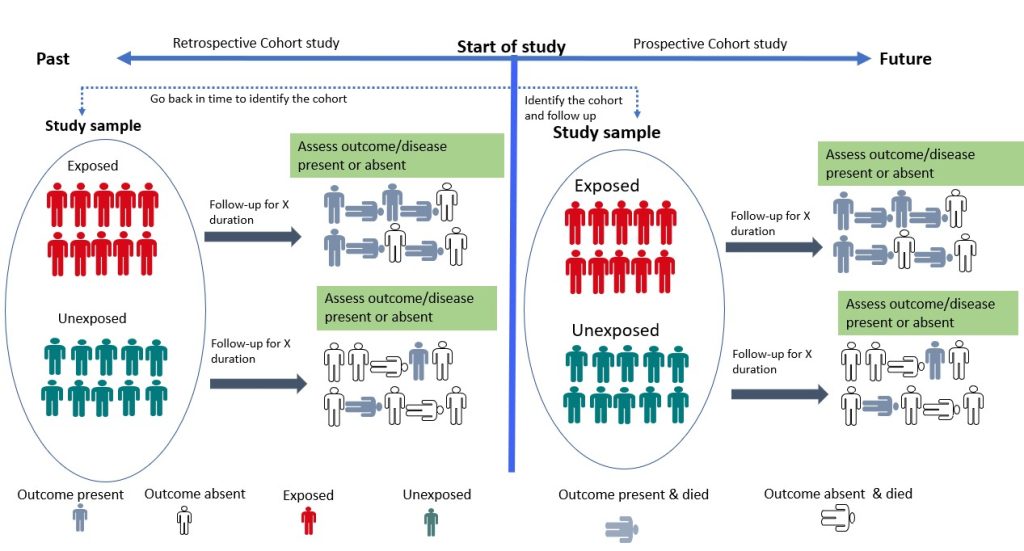

- Cohort Study

Cohort studies are longitudinal studies in which the researcher follows a group of individuals who share a common characteristic (e.g., age, occupation) over time to monitor the occurrence of a particular health outcome. 19 The study begins with the selection of a group of individuals who are initially free of the disease or health outcome of interest (the “cohort”). The cohort is then divided into two or more groups based on their level of exposure (for example, those who have been exposed to a certain risk factor and those who have not). 19 Participants are then followed up, and their health outcomes are tracked over time. The incidence of the health outcome is compared between exposed and non-exposed groups, and the relationship between exposure and the outcome is quantified using statistical methods. 19 Cohort studies can be prospective or retrospective (Figure 3.4). 20 In a prospective cohort study, the researchers plan the study so that participants are enrolled at the start of the study and followed over time. 20, 21 In a retrospective cohort study, data on exposure and outcome are collected from existing records or databases. The researchers go back in time (via available records) to find a cohort that was initially healthy and “at risk” and assess each participant’s exposure status at the start of the observation period. 20, 21 Cohort studies provide an understanding of disease risk factors based on findings in thousands of individuals over many years and are the foundation of epidemiological research. 19 They are useful for investigating the natural history of a disease, identifying risk factors for a disease, providing strong evidence for causality and estimating the incidence of a disease or health outcome in a population. However, they can be expensive and time-consuming to conduct. 15 An example of a cohort study is the study by Watts et al, 2015 which investigated whether the communication and language skills of children who have a history of stuttering are different from children who do not have a history of stuttering at ages 2–5 years. 22 The findings revealed that children with a history of stuttering, as a group, demonstrated higher scores on early communication and language measures compared to their fluent peers. According to the authors, clinicians can be reassured by the finding that, on average, children who stutter have early communication and language skills that meet developmental expectations. 22

Experimental Study Designs (Interventional studies)

Experimental studies involve manipulating one or more variables in order to measure their effects on one or more outcomes. 23 In this type of study, the researcher assigns individuals to two or more groups that receive or do not receive the intervention. Well-designed and conducted interventional studies are used to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables. 23 Experimental studies can be broadly classified into two – randomised controlled trials and non-randomised controlled trials. 23 These study designs are discussed below:

- Randomised Controlled Trial

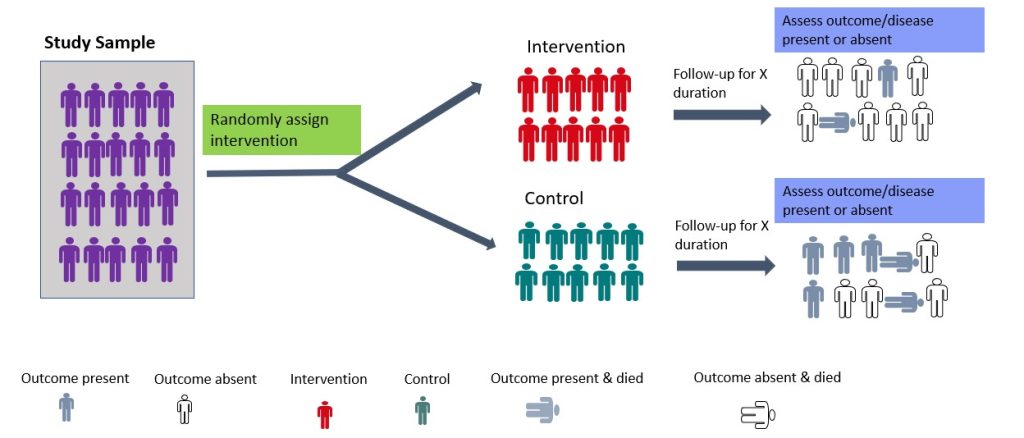

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are experimental studies in which participants are randomly assigned to the intervention or control arm of the study. 23 The experimental group receives the intervention, while the control group does not (Figure 3.5). RCTs involve random allocation (not by choice of the participants or investigators) of participants to a control or intervention group (Figure 3.5). 24 Randomization or random allocation minimises bias and offers a rigorous method to analyse cause-and-effect links between an intervention and outcome. 24 Randomization balances participant characteristics (both observed and unobserved) between the groups. 24 This is so that any differences in results can be attributed to the research intervention. 24 The most basic form of randomisation is allocating treatment by tossing a coin. Other methods include using statistical software to generate random number tables and assigning participants by simple randomisation or allocating them sequentially using numbered opaque envelopes containing treatment information. 25 This is why RCTs are often considered the gold standard in research methodology. 24 While RCTs are effective in establishing causality, they are not without limitations. RCTs are expensive to conduct and time-consuming. In addition, ethical considerations may limit the types of interventions that can be tested in RCTs. They may also not be appropriate for rare events or diseases and may not always reflect real-world situations, limiting their application in clinical practice. 24 An example of a randomised controlled trial is the study by Shebib et al., 2019 which investigated the effect of a 12-week digital care program (DCP) on improving lower-back pain. The treatment group (DCP) received the 12-week DCP, consisting of sensor-guided exercise therapy, education, cognitive behavioural therapy, team and individual behavioural coaching, activity tracking, and symptom tracking – all administered remotely via an app. 26 While the control group received three digital education articles only. The findings of the study showed that the DCP resulted in improved health outcomes compared to treatment-as-usual and has the potential to scale personalised evidence-based non-invasive treatment for patients with lower-back pain. 26

- Non-randomised controlled design (Quasi-experimental)

Non-randomised controlled trial (non-RCT) designs are used where randomisation is impossible or difficult to achieve. This type of study design requires allocation of the exposure/intervention by the researcher. 23 In some clinical settings, it is impossible to randomise or blind participants. In such cases, non-randomised designs are employed. 27 Examples include pre-posttest design (with or without controls) and interrupted time series. 27, 28 For the pre-posttest design that involves a control group, participants (subjects) are allocated to intervention or control groups (without randomisation) by the researcher. 28 On the other hand, it could be a single pre-posttest design study where all subjects are assessed at baseline, the intervention is given, and the subjects are re-assessed post-intervention. 28 An example of this type of study was reported by Lamont and Brunero (2018 ), who examined the effect of a workplace violence training program for generalist nurses in the acute hospital setting. The authors found a statistically significant increase in behaviour intention scores and overall confidence in coping with patient aggression post-test. 29 Another type of non-RCT study is the interrupted time series (ITS) in which data are gathered before and after intervention at various evenly spaced time points (such as weekly, monthly, or yearly). 30 Thus, it is crucial to take note of the precise moment an intervention occurred. The primary goal of an interrupted time series is to determine whether the data pattern observed post-intervention differs from that noted prior. 30 Several ITS were conducted to investigate the effectiveness of the different prevention strategies (such as lockdown and border closure) used during the COVID pandemic. 31, 32 Although non-RCT may be more feasible to RCTs, they are more prone to bias than RCTs due to the lack of randomisation and may not be able to control for all the variables that might affect the outcome. 23

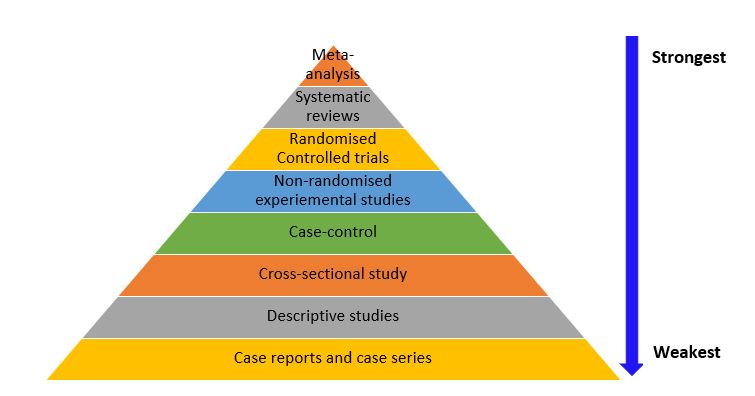

Hierarchy of Evidence

While each study design has its unique characteristics and strengths, they are not without weaknesses (as already discussed) that impact the accuracy of the results and research evidence they provide. The hierarchy of evidence is a framework used to rank the evidence provided by different study designs in research evaluating healthcare interventions with respect to the strength of the presented results (i.e., validity and reliability of the findings). 33 Study designs can be ranked in terms of their ability to provide valid evidence on the effectiveness (intervention achieves the intended outcomes), appropriateness (impact of the intervention from the perspective of its recipient) and feasibility (intervention is implementable) of the research results they provide. 33 As shown in Figure 3.6, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and RCTs provide stronger best-practice evidence and scientific base for clinical practice than descriptive studies as well as case reports and case series. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the research question/ hypothesis determines the study design, and not all questions can be answered using an interventional design. In addition, there are other factors that need to be considered when choosing a study design, such as funding, time constraints, and ethical considerations, and these factors are discussed in detail in chapter 6.

An Introduction to Research Methods for Undergraduate Health Profession Students Copyright © 2023 by Faith Alele and Bunmi Malau-Aduli is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Quantitative Research Design: Four Common Ways to Collect Your Data Efficiently

What is the quantitative research design? Why is the research design needed? What are the four main types of quantitative research designs used by researchers?

This article illustrates research design using an analogy, explains why a research design is needed, describes four main types of research designs, and gives examples of each research design’s application.

In doing your research on whatever goals you have in mind, you make a plan to reach those goals. You spell out the specific items that you want to pursue in your research objectives.

An Analogy of Research Design

Researching to reach a predetermined goal is like building a house. To avoid costly rebuilding, it would be a good idea to make a plan first and consider all the requirements to produce one that appeals to your taste.

You need to engage the architect’s help to draw what you have in mind (your concept), estimate the cost to build it, and list the steps to follow to bring that plan into reality. The architect comes up with a blueprint of the house, detailing the size and quantity of reinforced steel bars, the floor plan, dimensions of the house, and aesthetics.

If your house comprises not only one floor but two, or even three, and you want the house to be sturdy, that could last decades or generations; you will need to engage a structural engineer. He makes sure that the home maintains its integrity and can handle the loads and forces they encounter through time.

And, of course, the electrical connections require the expertise of an electrical engineer. He plans how the electrical circuits are arranged in the entire house to make it convenient for you to access electricity.

To build your dream house, you will need to have a good plan–your design.

Why is a Research Design Needed?

As pointed out earlier, the main reasons for coming up with a research design relate to efficiency and effectiveness. If you have a good research design, you will save time, energy, and cost in doing your research. You have a plan to get the data that you want to answer the research objectives.

Thus, before conducting research, you already have in mind what to expect. And of course, you will know how much that would cost you. If you cannot afford it, then you revise your plan.

Defining the Research Objectives

However, your research design or plan cannot be carried out if you don’t have a clear idea about what you want. The architect cannot design a project based on a simple directive to make a house plan. The outcome may not be to your liking, and you will just be wasting your money and his time. It will be a hit-and-miss approach.

Thus, you will need to define your research objectives based on your topic of interest. What do you want to achieve in your research? Will you be dealing with people, animals, plants, or things?

Will you manipulate some variables? Will you compare different groups? Would you want to know which variable causes an effect on other variables? Or will you describe what is there?

It all boils down to what you want . Be very clear if you’re going to describe things, correlate them, find out if one causes the other, or put up an experiment to test if manipulating one variable can effect a change to another variable.

Now, here are the four quantitative research designs.

The Four Main Types of Quantitative Research Design

Experts classify quantitative research design into four types. These are descriptive, correlational, causal-comparative, and experimental research.

The four quantitative research designs are distinguished from each other in Figure 1. Please note that as you go from left to right; the approach becomes more manipulative. The descriptive research design studies the existing situation, whereas the researcher manipulates variables at the other end, using the experimental method.

Quantitative research design examples are given for each of the four quantitative research designs in the next section.

Examples of the Application of the Different Research Design on the Same Subject

Descriptive research design.

A willingness to pay (WTP) study aimed to determine the vehicle owner’s knowledge about air quality and attitude towards the government’s regulation of requiring emission testing every time the car’s registration is renewed. This investigation will provide information that will show how knowledgeable the respondents are about air quality and reveal patterns of behavior towards the government’s measures to control carbon emissions. It explores the drivers’ willingness to pay for vehicle maintenance costs.

Correlational Research Design

The same study on air quality may be conducted as in Example 1, but this time, the respondent’s awareness about air quality is correlated with their attitude towards emission testing.

The study by Amindrad et al. (2013) on the Relationship Between Awareness, Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Environmental Education Among Secondary School Students in Malaysia exemplifies this research design.

Causal-Comparative Research Design

Still, on the air quality study, you might want to know what causes the respondents to behave positively or negatively towards emission testing. Does attitude have something to do with a person’s educational background? Or perhaps, their capacity to pay for emission testing?

The following video explains this research design further with two examples.

Experimental Research Design

Using still the air quality study, you might now want to test if two groups of drivers behaved differently when one group was required to attend a seminar on air pollution, and the other group was not required to attend.

The two groups’ members were randomly assigned, and all other variables were kept constant, meaning the respondents have similar characteristics where only attendance at the seminar is the difference.

You are interested in finding the difference between a person’s attitude towards emission testing. And what discriminates them from the other is that one group attended a seminar on air pollution while the other group did not.

Final Notes

Note that those listed are not mutually exclusive research designs. We can combine them.

For example, you can undertake a study that uses both a descriptive and a correlational research design. Hence, you describe this approach in your methodology as a descriptive-correlational research design.

That wraps it up.

There are still other types of research designs out there. What is important here is that you are clear about what you want to investigate.

Aminrad, Z., Zakariya, S. Z. B. S., Hadi, A. S., & Sakari, M. (2013). Relationship between awareness, knowledge and attitudes towards environmental education among secondary school students in Malaysia. World Applied Sciences Journal, 22(9), 1326-1333.

© 2020 October 15 P. A. Regoniel, updated 27 November 2021

Related Posts

How to develop a keen perception for research purposes, research findings dispel old myths.

What Makes Content Go Viral? Six Intriguing Reasons Derived From 6,956 Articles

About the author, patrick regoniel.

Dr. Regoniel, a faculty member of the graduate school, served as consultant to various environmental research and development projects covering issues and concerns on climate change, coral reef resources and management, economic valuation of environmental and natural resources, mining, and waste management and pollution. He has extensive experience on applied statistics, systems modelling and analysis, an avid practitioner of LaTeX, and a multidisciplinary web developer. He leverages pioneering AI-powered content creation tools to produce unique and comprehensive articles in this website.

SimplyEducate.Me Privacy Policy

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2 Types of Quantitative Research Designs

There are three main groups of Research Designs that will be explored in this chapter.

- Experimental

- Quasi-experimental

- Non-experimental

When reviewing each design, the purpose and key features of the design, advantages and disadvantages, and the most commonly used designs within the category will be reviewed.

1. Experimental Design

Purpose: Evaluate outcomes in terms of efficacy and/or cost effectiveness

Experimental design features include:

- Randomization of subjects to groups

- Manipulation of independent variable (e.g., an intervention or treatment)

- Control – the use of a control group and control measures (for controlling extraneous variables )

Advantages:

- Most appropriate for testing cause-and-effect relationships (e.g., generalizability is most likely)

- Provides the highest level of evidence (e.g., level II) for single studies

Disadvantages:

- Attrition especially control group participants or with ‘before-after’ experimental designs

- Feasibility and logistics may be an issue is certain settings (e.g., long-term care homes)

Caution: Not all research questions are amenable to experimental manipulation or randomization

Most Commonly Used Experimental Designs

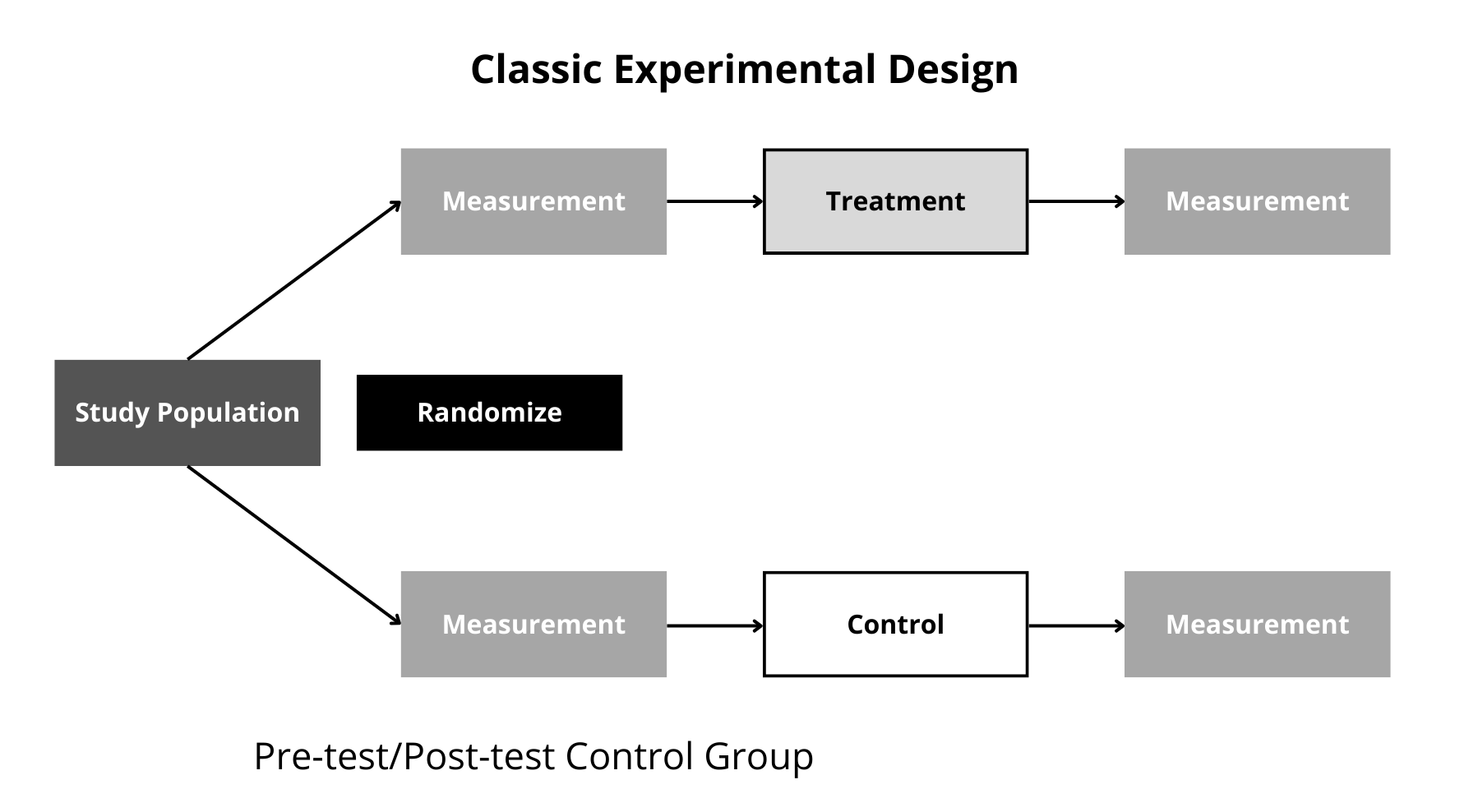

- True experimental (pre- post-test ) design (also referred to as Randomized Control Trials or RCTs ):

Figure 3. True experimental design (pre-post-test).

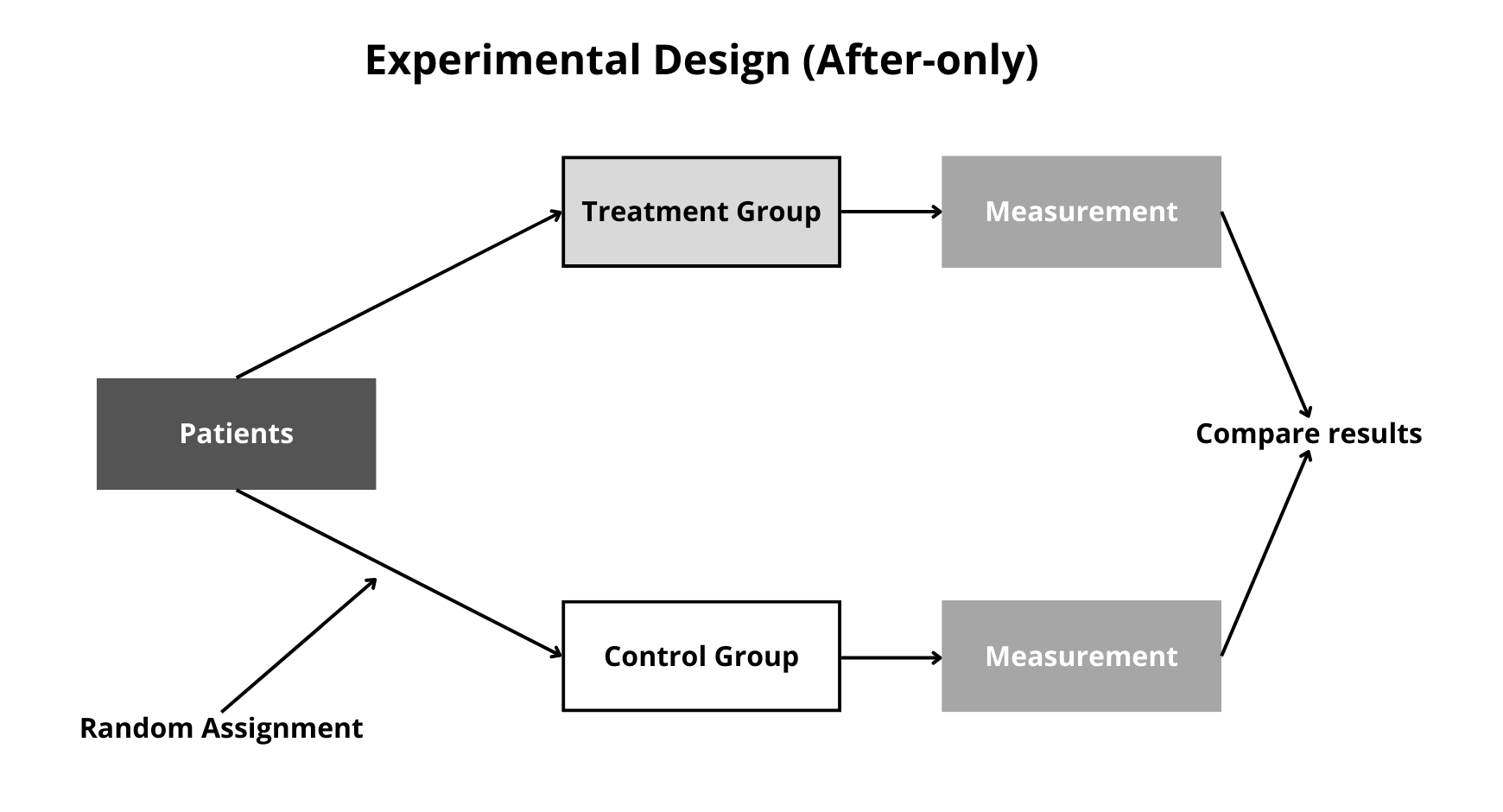

- After-only (post-test only) design :

Figure 4. After-only (post-test only) design.

- Solomon four-group design

This design is similar to the true experimental design but has an additional two groups, for a total of four groups. Two groups are experimental, while two groups are control. These “extra” groups do not receive the pre-test, allowing the researchers to evaluate the effect of the pretest on the post-test in the first two groups.

2. Quasi-Experimental Design

Purpose: Similar to experimental design, but used when not all the features of an experimental design can be met:

- Manipulation of the independent variable (e.g., an intervention or treatment)

- Experimental and control groups may not be randomly assigned (no randomization)

- There may or may not be a control group

Advantages:

- Feasibility and logistics are enhanced, particularly in clinical settings

- Offers some degree of generalizability (e.g., applicable to population of interest)

- May be more adaptable in real-world practice environments

Disadvantages:

- Generally weaker than experimental designs because groups may not be equal with respect to extraneous variable due to the lack of randomization

- As a result, cause-and-effect relationships are difficult to claim

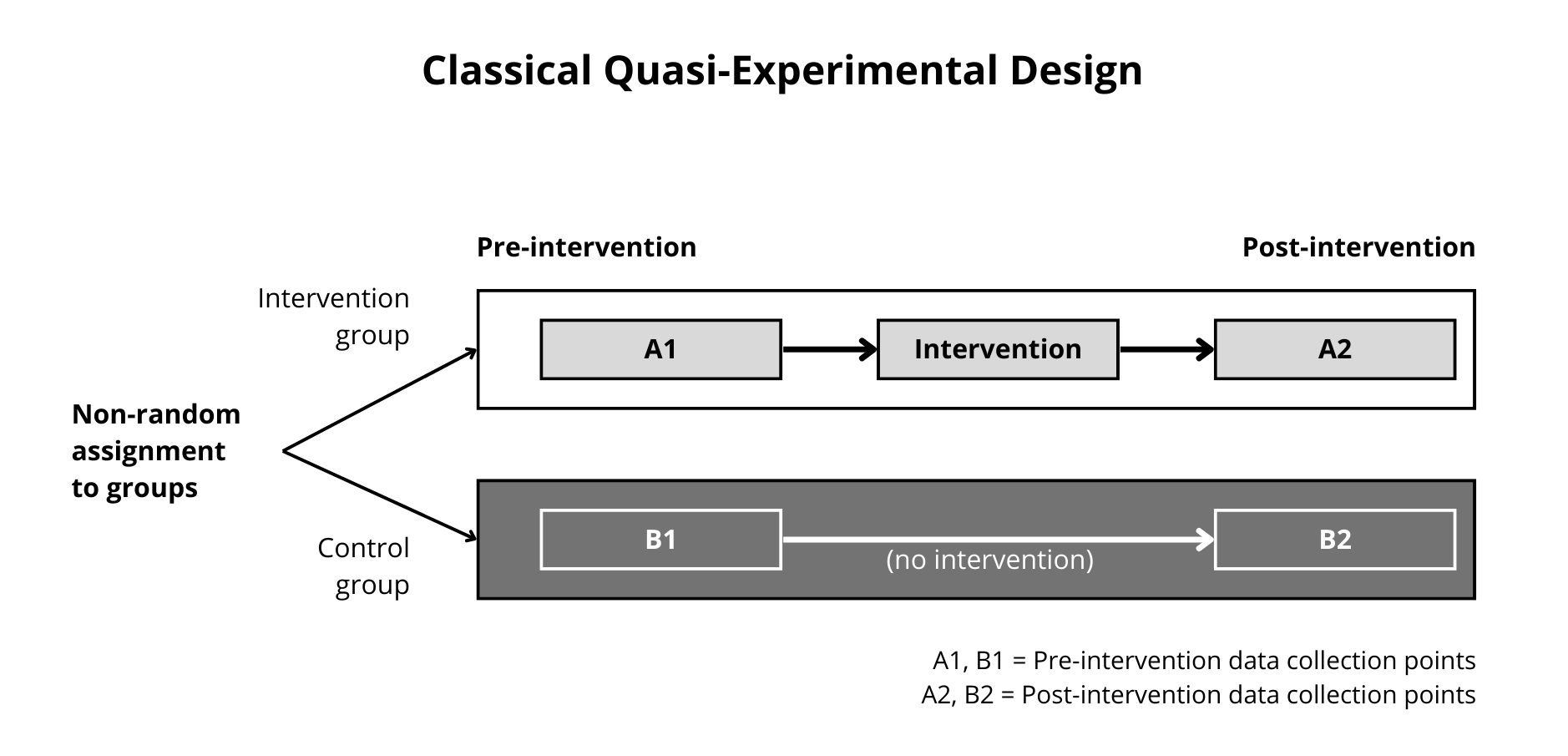

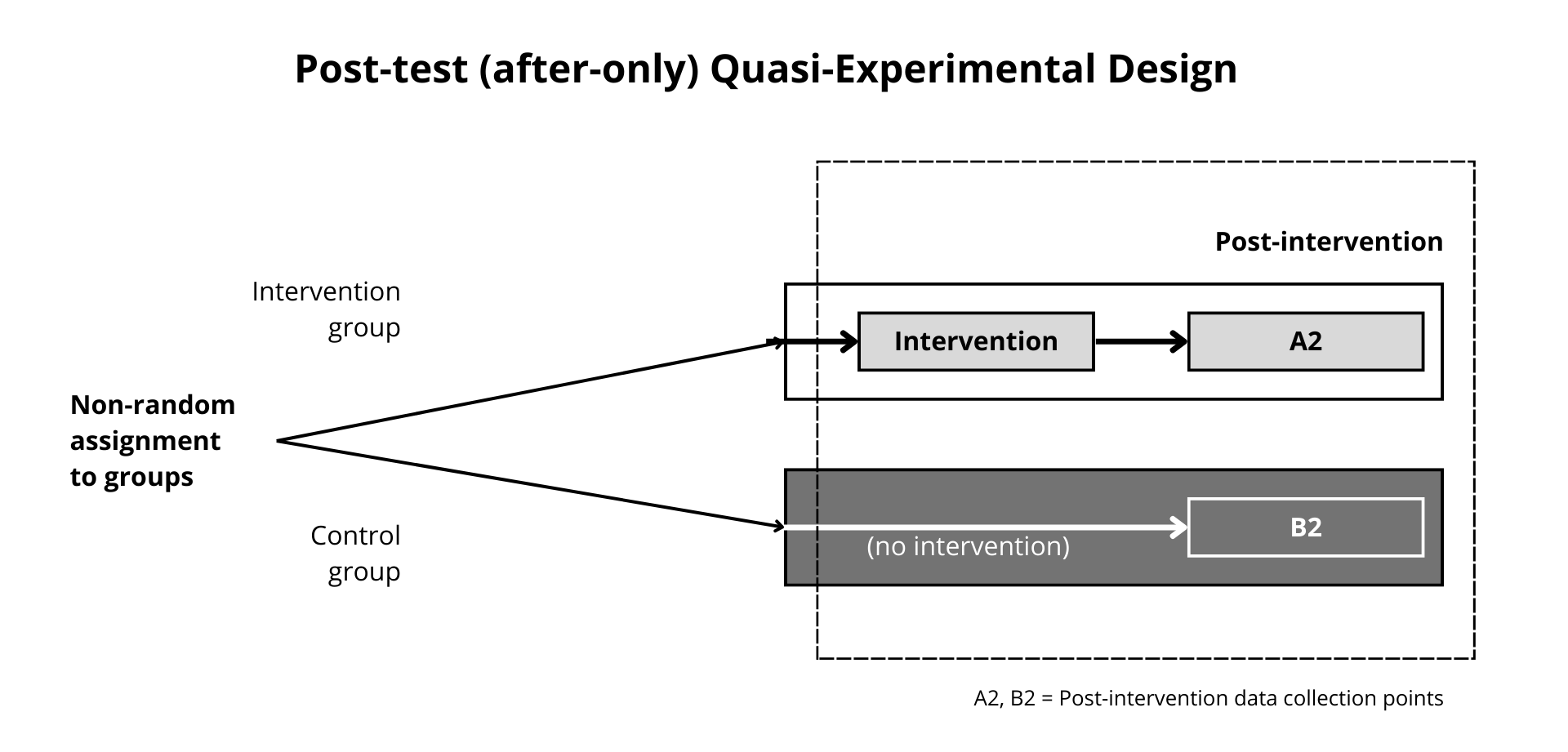

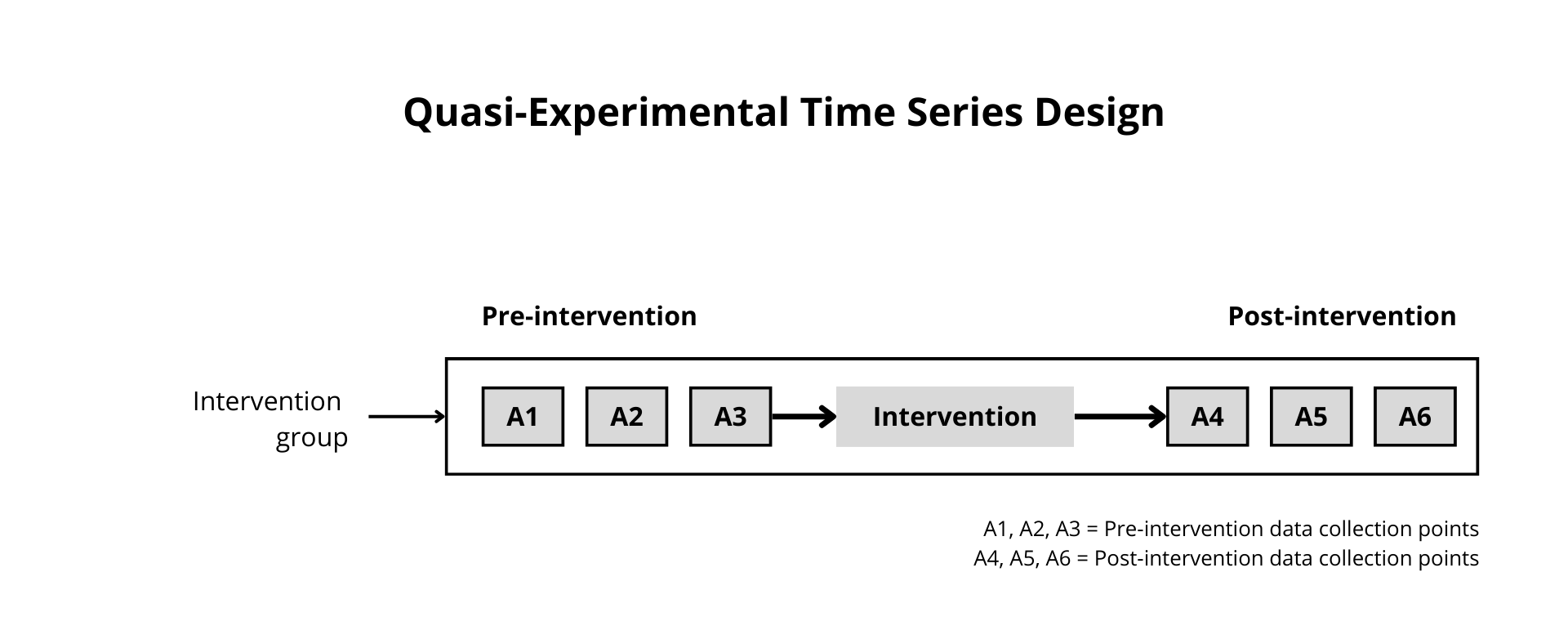

Options for Quasi-experimental Designs include :

- Non-equivalent control group design

Figure 5. Classical Quasi-Experimental Design. Adapted from Knowledge for Health

- After-only control group design

Figure 6. Post-Test Only Quasi-Experimental Design. Adapted from Knowledge for Health.

- Time-series design Important note: The time series design is considered quasi-experimental because subjects serve as their ‘own controls’ (same group of people, compared before and after the intervention for changes over time).

Figure 7. Time-series design. Adapted from Knowledge for Health

- One group pre-test-post-design design In this design there is no control group. The one group, considered the experimental group, is tested pre and post the intervention. The design is still considered quasi-experimental as there is manipulation of the intervention.

3. Non-experimental

Purpose: When the problem to be solved or examined is not amenable to experimentation; used when the researcher wants to:

- Study a phenomenon at one point in time or over a period of time

- Study (and measure) variables as they naturally occur

- Test relationships and differences among variables

- Used when the knowledge base on a phenomenon of interest is limited or when the research question is broad or exploratory in nature

- Appropriate for forecasting or making predictions

- Useful when the features of an experiment (e.g., randomization, control, and manipulation) are not appropriate or possible (e.g., ethical issues)

- Inability to claim cause-and-effect relationships

Options for Non-experimental Designs include:

- Survey studies: descriptive, exploratory, comparative

- Relationship or difference studies: Correlational, developmental

- Cross-sectional studies

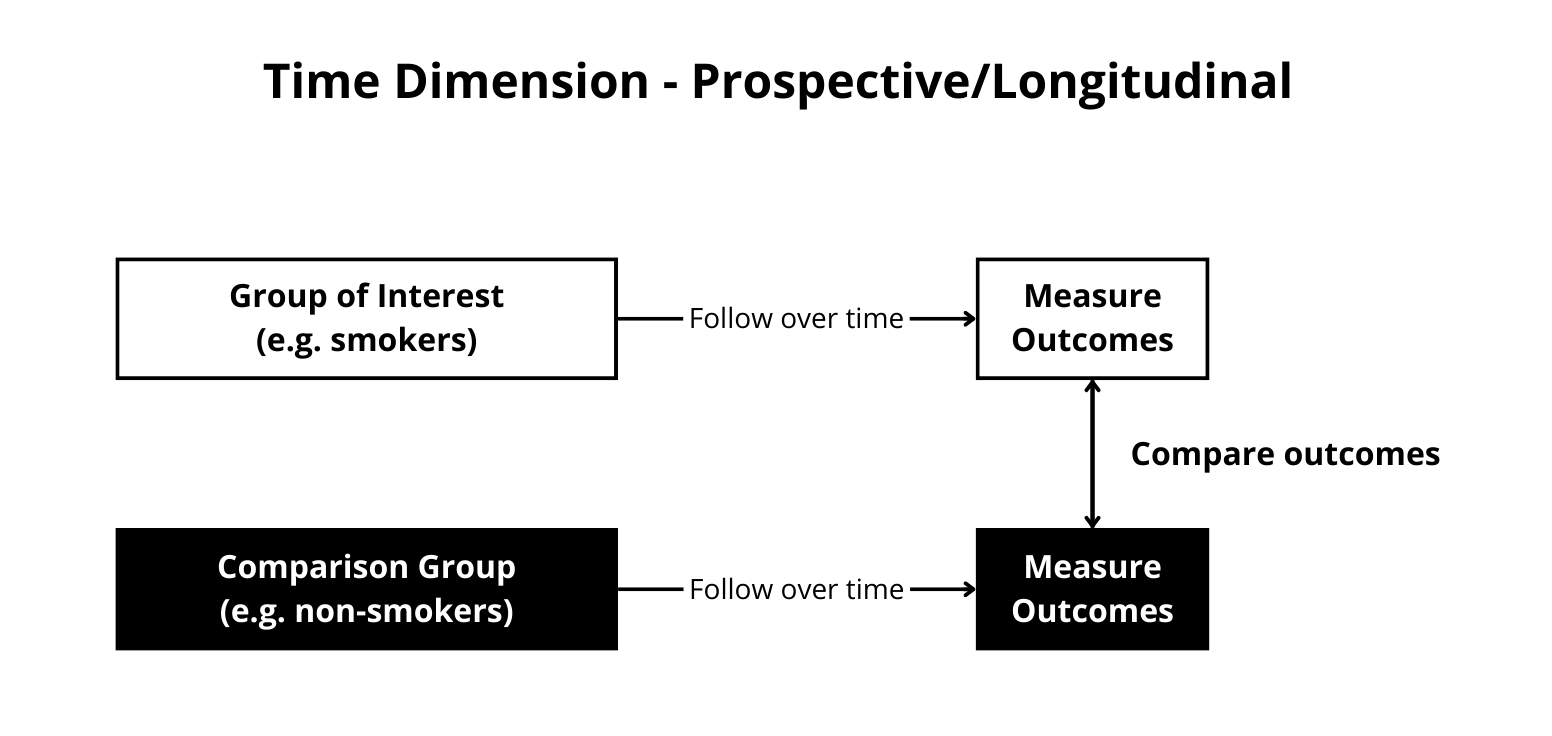

- Longitudinal or Prospective studies

Figure 8. Longitudinal or Prospective studies. Adapted from University of Minnesota, Driven for Discover Libraries .

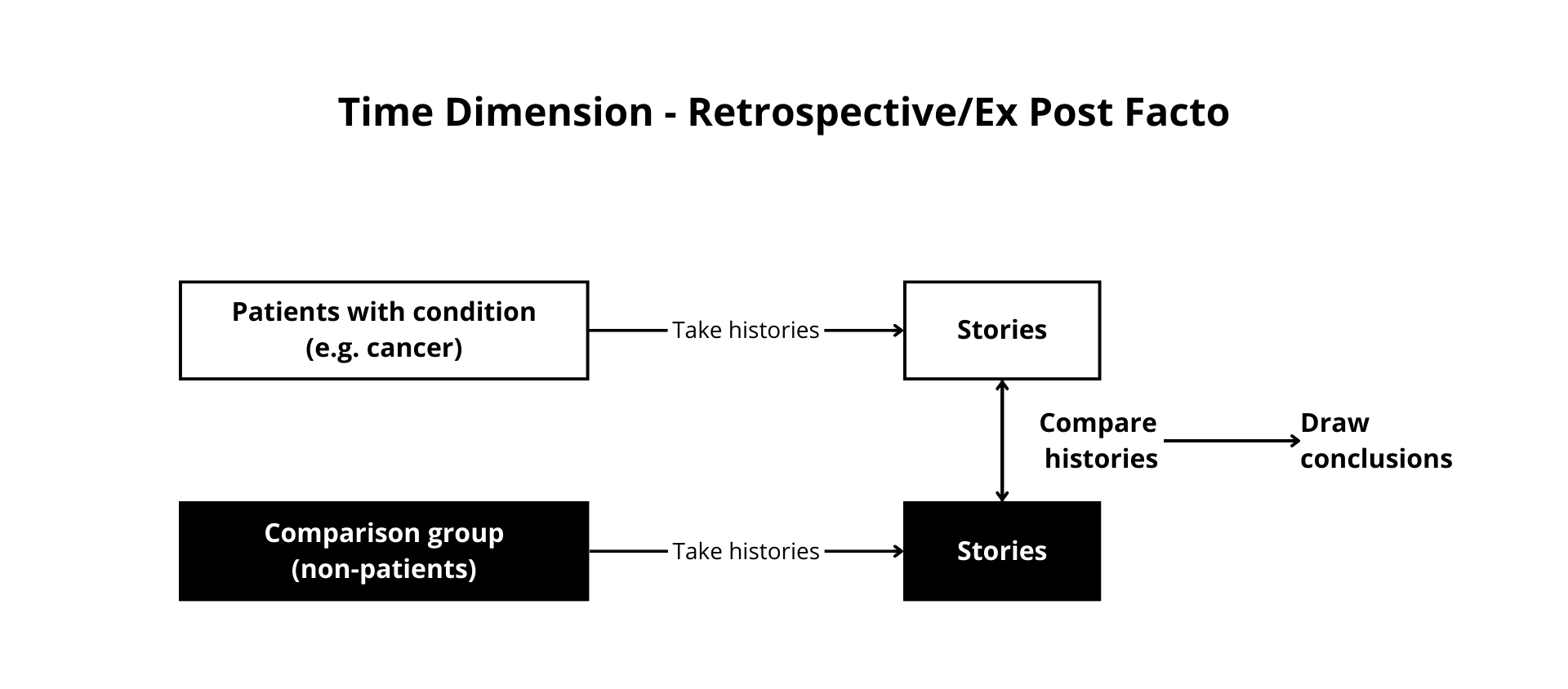

- Retrospective ( Ex Post Facto ) studies

Additional terms to consider when reading research

Learners may find it difficult when reading research to identify the Research Design used. Please consult the table below for more information on terms frequently used in research.

This refers to how the sample is selected. When randomization is used each participant from the desired population has an equal chance of being assigned to the experimental or control group.

These are variable that may interfere with the independent and dependent variables. Also called mediating variables.

The loss of participants from the study.

An Introduction to Quantitative Research Design for Students in Health Sciences Copyright © 2024 by Amy Hallaran and Julie Gaudet is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Types Of Quantitative Research Designs And Methods

Quantitative research design uses a variety of empirical methods to assess a phenomenon. The most common method is the experiment,…

Quantitative research design uses a variety of empirical methods to assess a phenomenon. The most common method is the experiment, but there are other types of quantitative research as well, such as correlation studies and case studies.

In contrast with qualitative research, which relies on subjective interpretations and extensive explorations, the various types of quantitative methods use objective analysis to reveal patterns and relations among data points that often have a numerical value. Quantitative research provides a mathematical summary of the results.

Let’s look at quantitative research design, the types of quantitative research methods and their respective strengths and weaknesses.

Types Of Quantitative Research

Components of quantitative research design.

If a researcher is studying a single variable, time, space, or another construct, they’re engaged in qualitative research. However, if that variable is a collection of quantitative data points—such as the number of employees that use a workplace break room compared to the number of employees who use other break rooms—the researcher is engaged in quantitative research.

Here are some methods commonly used in quantitative research design:

1. Experiment

The experiment is perhaps the most common way for quantitative researchers to gather data. In this method, researchers manipulate one variable at a time, while they hold all other variables constant. If a researcher wishes to determine which type of computer mouse is easier for employees to use, they must ensure the employees are experienced with computers, comfortable with their chairs or desks and have no issues with their eyesight. Common methods for this type of research include randomized experiments, non-randomized experiments, clinical trials and field studies.

2. Correlation

Correlation studies come in many forms, from simple correlation diagrams to the analysis of multiple variables. For instance, a researcher examining rates of depression among veterinarians could look at associations between self-perceived social status, salary and depression.

3. Cohort Studies

Cohort studies provide a way to measure the extent of change over a period of time. This type of research can lead to results that are both objective and subjective, depending on the type of study employed. For instance, a cohort study examining police officer salaries could determine what salary a police officer should make in an area. However, this same study could also delve into the subjective question of whether police officers are fairly paid compared to other professions.

Research design is a critical factor in the success of a study.

While there are many types of quantitative research methods that can be employed, the basic parts of all research designs are the same. Here are the principal components:

At the heart of every research project is a well-framed and considered question. Having a clear objective is the most important part of quantitative research design. Some examples of research questions could be:

- Which type of coffee brewing method extracts the most flavor?

- Which books are contributing most to a publisher’s profit?

- Which newspaper is the most widely read in a city?

In quantitative research design, researchers may explore the relationship between variables in a correlation study, or it could mean determining what variables are best in an experiment.

Once the aim is in place, the actual data collection method must be chosen. This will depend on the data needed to answer the research question. Some options are:

- Participant observations

- Experimental data

As long as the data is expressed numerically, it is quantitative data.

The selection process used to choose participants is a critical component of all types of quantitative research designs. Researchers need a well-defined population. This group can be as small as two people, but it could also be thousands of people as well.

Data Analysis

Once the data is collated, a researcher must decide how to analyze it. Some options at their disposal include:

- Descriptive analysis

- Content analysis

- Statistical tests

Once again, it depends on the research question and the goals of the study.

Presentation

This is sometimes referred to as dissemination. How will the research findings be shared with the world? Common choices are:

- Presentations

- Website articles and blogs

A quantitative researcher’s greatest contribution is that their work can be replicated. Because quantitative research relies on numbers, the results of the study can be exactly duplicated by other researchers.

With Harappa’s Thinking Critically course, professionals at all levels of their careers will learn how to organize their thoughts with the most impact. Assessing available information is an important part of this. Making gut decisions isn’t the mark of a mature manager—when decisions need to be made, all data must be considered dispassionately. These insights then need to be shared with team members and bosses. Give your teams the best chance of success with this course that delivers transformative skills.

Explore Harappa Diaries to learn more about topics such as What is Qualitative Research , Types Of Qualitative Research Methods , Quantitative Vs Qualitative Research and How To Apply Starbursting Technique to upgrade your knowledge and skills.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.