What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write the AP Lit Poetry Essay

What’s covered:.

- How to Write the AP Literature Poetry Essay

- Tips for Writing The AP Lit Poetry Essay

To strengthen your AP Literature Poetry Essay essay, make sure you prepare ahead of time by knowing how the test is structured, and how to prepare. In this post, we’ll cover the structure of the test and show you how you can write a great AP Literature Poetry Essay.

What is the AP Lit Poetry Essay?

The AP Literature exam has two sections. Section I contains 55 multiple choice questions, with 1 hour time allotted. This includes at least two prose fiction passages and two poetry passages.

Section II, on the other hand, is a free response section. Here, students write essays to 3 prompts. These prompts include a literary analysis of a poem, prose fiction, or in a work selected by the student. Because the AP Literature Exam is structured in a specific, predictable manner, it’s helpful to prepare yourself for the types of questions you’ll encounter on test day.

The Poetry Essay counts for one-third of the total essay section score, so it’s important to know how to approach this section. You’ll want to plan for about 40 minutes on this question, which is plenty of time to read and dissect the prompt, read and markup the poem, write a brief outline, and write a concise, well-thought out essay with a compelling analysis.

Tips for Writing the AP Lit Poetry Essay

1. focus on the process.

Writing is a process, and so is literary analysis. Think less about finding the right answer, or uncovering the correct meaning of the poem (there isn’t one, most of the time). Read the prompt over at least twice, asking yourself carefully what you need to look for as you read. Then, read the poem three times. Once, to get an overall sense of the poem. Second, start to get at nuance; circle anything that’s recurring, underline important language and diction , and note important images or metaphors. In your annotations, you want to think about figurative language , and poetic structure and form . Third, pay attention to subtle shifts in the poem: does the form break, is there an interruption of some sort? When analyzing poetry, it’s important to get a sense of the big picture first, and then zoom in on the details.

2. Craft a Compelling Thesis

No matter the prompt, you will always need to respond with a substantive thesis. A meaty thesis contains complexity rather than broad generalizations , and points to specifics in the poem.

By examining the colloquial language in Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem, “We Real Cool”, we can see the tension of choosing to be “cool”. This raises important ideas about education, structure, and routine, and the consequences of living to be “real cool”.

Notice how the thesis provides a roadmap of what is to follow in the essay , and identifies key ideas that the essay will explore. It is specific, and not vague. The thesis provides a bigger picture of the text, while zooming in the colloquial language the speaker uses.

A good thesis points out the why as much as the what . Notice how in the above example, the thesis discusses language in the poem as it connects to a bigger message about the poem. For example, it’s not enough to discuss Emily Dickinson’s enjambment and hyphens. A good thesis will make a compelling argument about why those infamous Dickinson hyphens are so widely questioned and examined. Perhaps a good thesis might suggest that this unique literary device is more about self-examination and the lapse in our own judgement.

3. Use Textual Evidence

To support your thesis, always use textual evidence . When you are creating an outline, choose a handful of lines in the poem that will help illuminate your argument. Make sure each claim in your essay is followed by textual evidence, either in the form of a paraphrase, or direct quote . Then, explain exactly how the textual evidence supports your argument . Using this structure will help keep you on track as you write, so that your argument follows a clear narrative that a reader will be able to follow.

Your essay will need to contain both description of the poem, and analysis . Remember that your job isn’t to describe or paraphrase every aspect of the poem. You also need lots of rich analysis, so be sure to balance your writing by moving from explicit description to deeper analysis.

4. Strong Organization and Grammar

A great essay for the AP Literature Exam will contain an introduction with a thesis (not necessarily always the last sentence of the paragraph), body paragraphs that contain clear topic sentences, and a conclusion . Be sure to spend time thinking about your organization before you write the paper. Once you start writing, you only want to think about content. It’s helpful to write a quick outline before writing your essay.

There’s nothing worse than a strong argument with awkward sentences, grammatical errors and spelling mistakes. Make sure to proofread your work before submitting it. Carefully edit your work, paying attention to any run-on sentences, subject-verb agreement, commas, and spelling. You’d be surprised how many mistakes you’ll catch just by rereading your work.

Common Mistakes on the AP Literature Poetry Essay

It can be helpful to know what not to do when it comes time to prepare for the AP Literature Poetry Essay. Here are some common mistakes students make on the AP Literature Poetry Essay:

1. Thesis is not arguable and is too general

Your thesis should be arguable, and indicate the central ideas you will discuss in your essay. Read the prompt carefully and craft your thesis in light of what the prompt asks you to do. If the prompt mentions specific literary devices, find a way to tie those into your thesis. In your thesis, you want to connect to the meaning of the poem itself and what you feel the poet intended when using those particular literary devices.

2. Using vague, general statements rather than focusing on analysis of the poem

Always stay close to the text when writing the AP Literature Poetry Essay. Remember that your job is not to paraphrase but to analyze. Keep explicit descriptions of the poem concise, and spend the majority of your time writing strong analysis backed up by textual evidence.

3. Not using transitions to connect between paragraphs

Make sure it’s not jarring to the reader when you switch to a new idea in a new paragraph. Use transitions and strong topic sentences to seamlessly blend your ideas together into a cohesive essay that flows well and is easy to follow.

4. Textual evidence is lacking or not fully explained

Always include quotes from the text and reference specifics whenever you can. Introduce your quote briefly, and then explain how the quote connects back to the topic sentence after. Think about why the quotes connect back to the poet’s central ideas.

5. Not writing an outline

Of course, to write a fully developed essay you’ll need to spend a few minutes planning out your essay. Write a quick outline with a thesis, paragraph topics and a list of quotes that support your central ideas before getting started.

To improve your writing, take a look at these essay samples from the College Board, with scoring guidelines and commentary.

How Will AP Scores Affect My College Chances?

While you can self-report AP scores, they don’t really affect your admissions chances . Schools are more interested in how you performed in the actual class, as your grades impact your GPA. To understand how your GPA impacts your college chances, use our free chancing engine . We’ll let you know your personal chance of acceptance at over 1500 schools, plus give you tips for improving your profile.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

How to Encourage Students to Master the AP Lit Thesis

- December 1, 2021

- AP Literature , Writing

For years, I have used a Poem of the Week as part of my poetry instruction in AP Literature . Last year, because the pandemic resulted in hybrid instruction and only 50% (or fewer) of my kids were in class at a time, I wanted to be sure that I put some significant emphasis on AP Lit thesis writing.

As part of our weekly poem study, the Friday prompt became an AP-style poetry essay prompt. Students only needed to write a thesis. And early in the year, it became evident that our thesis statements needed work.

AP Literature Thesis Statements and “The Point”

When the College Board came out with the new rubrics in 2019, they set aside a point that is designated for the thesis. It’s one point and students either get it or they don’t. And truthfully, it is not that hard to “get” the point. Students must simply “provide a defensible interpretation in response to the prompt” which could be supported by the text (for more, see AP Central). So in other words, students must be able to find *something* in the text that they can write about beyond a summary.

Early on, I observed two things: 1. Not all AP Lit thesis statement are created equal (even if they do earn the point) and 2. Students needed help moving from making a base claim to making a strong claims that lead to better analysis later in the essay.

AP Lit Thesis Starting Points

At the beginning of the year, my kids were writing things like

- The author uses metaphors to reveal that life gives you new, and endless opportunities each and every day.

- Merriam’s use of her metaphor for a new day in “Metaphor” reveals her positive outlook on life.

- eve marriam’s use of metaphor shows that she feels that every day is new day to write your own story.

- Love can cause pain

- Lowell uses diction and figurative language to show her intimate and spiritual connection to her partner in the poem

- Through Lowell’s uses of poetic elements and techniques, she’s able to carefully convert the speaker’s complex relationship with whoever they’re addressing.

While indeed some of these would earn the thesis point, they do no convey the depth that a good, strong AP Lit thesis will. We want students to address the complexity of the text and these just don’t cut it.

The Issue of Complexity

So the first step in helping students to develop a strong thesis is to get beyond just repeating the topic with a few elements of author’s craft thrown in. They have to be sure that they are fully addressing the complexity of the topic highlighted by the task.

The first set of thesis statements above go with Eve Merriam’s poem “Metaphor.” This is my favorite poem to start the school year with because it reflects where we are. Each school year is also like a “new sheet of paper.”

We spend the week discussing the poem ( My daily prompts are available here. ) Then on Friday, I present students with the following prompt:

In Eve Merriam’s poem “Metaphor” (1986), the speaker portrays the blankness of a new day. In a well written essay, analyze how Merriam uses poetic elements and techniques to convey the speaker’s complex attitude toward life.

And while all of the above thesis statements DO say something about her attitude toward life, none of them get to how it is complex. So the first step is to get students thinking about contrasts within the poem and other elements that help add to the depth of the text. A good way to do this might be through the Interstate, Microscope and Compass Technique from Gina at Lit and More.

AP® Lit Literary Argument

Once students see complexity in a text, they can move into developing a more complex AP® literature thesis statement.

It is also important to remind them that the College Board calls these essays “literary argument.” And an argument is by definition something that has two sides. When we teach argument writing to our English 11 students in preparation for the New York State English Regents we encourage them to include the counterargument in their thesis. And although a literary argument doesn’t necessarily have a counterargument, it should have two sides. In other words, complexity.

In these early stages, it is sometimes useful to give the students complexity starters that they can use as the basis of their thesis statements. This is a list that I provide to my students:

- even though x, y is also true

- not only j, but also k

- although d, also e

- nevertheless

- notwithstanding

- in contrast

This list along with other helpful tips on writing AP Literature Thesis Statements is included in my AP Thesis Anchor charts here .

AP® Lit Thesis Examples

As we work through the year, thesis statements that once read “love can cause pain” become

“Even though Edith Matilda Thomas’s poem entitled “Winter Sleep” appears to be a simplistic take about growing old she also uses poetic elements such as symbolism, diction, and parallel structure to convey a complex attitude towards aging as she looks back on her life.”

“Although the speaker is reflecting on the spring-like happiness of her youth, she understands that death is coming as she moves into the metaphorical winter of her life due to her old age.”

Building on Complexity

The key to helping students earn the thesis point on the AP Literature Rubric is to help them understand that they are writing a literary argument and that an argument by its very nature has two sides or two part. Then include both of those sides in your thesis.

For more help in AP Lit Writing, be sure to check out these other AP Lit Essay Writing Anchor Charts.

more from the blog

Analyzing Character Complexity: Teaching Meaningful Character Analysis

Characterization is one of the most basic skills we teach students about reading. And it is a darn important one. It is actually a life

AP Literature Books about Coming of Age

One of my favorite units to do in AP Literature is a Hybrid Book Club Unit based around the theme of coming of age. Seniors

6 Ways to Elevate Lit Circles for Secondary

Literature Circles, sometimes called Lit Circles or Book Clubs, can be a powerful motivator in the classroom. They allow students choice in their reading and

4 Responses

- Pingback: Teaching Students How to Write Literary Analysis Paper in Six Easy Steps - The Teacher ReWrite

Is there a way to get working links. Both the link to the poem and the link to the daily prompts are both broken and give an error message when clicked.

Thank you for bringing that to my attention. These links are fixed now.

- Pingback: 5 Formative Assessment Strategies for High School - McLaughlin Teaches English

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Hi, I'm Jeanmarie!

I help AP Literature and High School English teachers create engaging classrooms so that students will be prepared college and beyond.

Learn more about me and how I can help you here

Let's Connect!

Your free guide to planning a full year of AP Literature

AP® is a trademark registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse, this product.

Much Ado About Teaching

Ap lit poetry essay review.

Whenever I prepare my students for the AP Literature exam, I don’t really want it to feel like test prep. I want to take the stress out of it all. I want the experience to build confidence. I want the process, starting around February, to have no stakes or very low stakes; it should be practice, not fear mongering. And I want there to be plenty opportunities for improvement.

So what does that look like?

Well, with essay writing we start small — on the sentence-level — at the beginning of the year, working to achieve mastery over thesis statements, evidence, and commentary. Multiple-choice practice is always completed in class, on paper and while scores are recorded, they never go in the grade book. When my students write full-length essays, they have the opportunity to rewrite as long as they conference with me because I learned long ago that a 15 minute conference with a student is far better than anything I could write in the margins.

But this week I was scratching my head trying to figure out how I could make rubric review NOT feel like test prep. My AP Lit classes were reviewing the Q1 essay, which is the poetry prompt. In my experience, rubrics can suck all the life out of a lesson. Students feel like the speaker in the Walt Whitman’s “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer.”

When I heard the learn’d astronomer, When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me, When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them, When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room, How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick,

The lesson I devised ended up being one of the more memorable ones of the quarter.

Day 1: Rubric Rhymes — I hand out copies of the Q1 rubric and toss highlighters to each student. They have to highlight the key descriptors for each category and point value on the rubric. Once that is done, students have to use their highlights and develop a poem in rhyming couplets that identifies what must be accomplished in order to score a six on this essay.

The poem had to be at least 10 lines long.

I will say, they loved this assignment and it I think its effect will endure.

Here are some samples:

You wants to make a good poetry essay creation?

That thesis best be full of top notch interpretation

Don’t just restate or rephrase information

But rather provide a good explanation

How many literary elements should you choose?

Multiple is what you should use

And sprinkle on some good seasoning

The one that tastes like strong reasoning

The last criterion to make you do well on your examination

I s make sure the essay demonstrates that advanced type of sophistication

I be writing a thesis

Just like I be eating reese’s, in pieces

If you don’t want evidence that’s horrific

Then you gotta be spec ific

I could ask Stabz for assistance

Or I could remember one word: consistence -y

Unlike my ex,

You gotta be complex

If you tryna get to the graduation

Then you gotta understand sophistication

Student III

You aint got time to waste

But that doesn’t mean that your essay should be written in haste

40 minutes to read and write

And develop ideas with sophistication and insight

First, make sure your thesis isn’t a bore

To develop a sophisticated interpretation really is a chore .

Answer the prompt, be clear and concise ,

Throw in poetic elements and a d evice

That central idea must be developed

Once stated, evidenced and commentary need to envelop

By not just saying what is true, but how and why

With brilliance so bright it would make an AP Reader cry .

S ummarize and your grade will surely suffe r

Articulate the complexity is much tougher

But do it over and over again

Establishing a line of reason, the n

P olish your thoughts like gems

Make those sentences sweet like M&M s

And never forget to discuss what is complex

All these boxes you must chec k

And a six on this essay will be yours

And you will have the wisdom of a thousand Dumbledors .

Day T wo: Performances/The whole-class essay — Class started with an opportunity for students to read their rap/poem in front of the class for extra credit. Some of the performances were epic.

Then I passed out a previous AP prompt and students had seven minutes to complete my four-step pre-writing organizer . Once those seven minutes were up, the fastest typer in class (we had a contest earlier in the year) came to the class computer and we worked together to develop a whole-class essay. This allowed students to think aloud together, wordsmith key phrases, and discuss their insights in a collaborative and non-threatening environment.

Throughout the process, we kept going back to the rubric to check if we were meeting the requirements.

Here are the intros from each class:

Period 1 — In Paul Lawrence Dunbar’s poem “The Mystery”, the speaker discusses navigating through life by himself. Throughout the poem, the speaker exists in a figurative darkness in which he experiences loneliness and questions the benevolence of a higher power; in this frustrated search for meaning and understanding, he illustrates through personification and imagery that whether or not there is a higher power. His conclusion is that he cannot wallow in his dependency and that he must be self reliant.

Period 6 — In Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem “The Mystery,” the speaker reflects on life. In a state of existential dread, he feels a sense of purposelessness and seeks navigation from a higher being. Paradoxically, in being given no direction, the speaker achieves solace in the inevitability of death and accepts the power of the present.

Period 8 — In Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem, “The Mystery”, the speaker is in a lonely place of uncertainty. While reflecting on the inevitability of death and appealing to a higher power, the speaker gains an awareness, not only of his own solitude, but also his powerlessness in the face of destiny. Through the use of personification, juxtaposition, and imagery, an epiphany is achieved in which he accepts the absurdity of life, thus gaining his autonomy.

Day 3: Essay test day — At this point students know the rubric, they did a practice essay the day before as a class, and now they are ready to do it all on their own.

In the comments section below, please share how you prepare students for the poetry essay on the AP exam.

Brian Sztabnik is just a man trying to do good in and out of the classroom. He was a 2018 finalist for NY Teacher of the Year, a former College Board advisor for AP Lit, and an award-winning basketball coach.

Elevating Student Writing

8 Things to Know for the AP Literature Exam

You may also like.

Book Club Choices

Why I’m Still Teaching

Digital Feedback Made Easy

Please go to the Instagram Feed settings page to create a feed.

Copyright © 2024 DAHZ All Rights Reserved. Much Ado About Teaching.

AP® English Literature

How to get a 9 on poetry analysis frq in ap® english literature.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: March 1, 2022

Are you taking the AP® English Literature and Composition exam? If you’re taking the course or self-studying, you know the exam is going to be tough. Of course, you want to do your best and score a five on the exam. To do well on the AP® English Literature and Composition exam, you’ll need to score high on the essays. For that, you’ll need to write a complete, efficient essay that argues an accurate interpretation of the work under examination in the Free Response Question section.

The AP® English Literature and Composition exam consists of two sections, the first being a 55-question multiple choice portion worth 45% of the total test grade. This section tests your ability to read drama, verse, or prose fiction excerpts and answer questions about them. The second section worth 55% of the total score requires essay responses to three questions, demonstrating your ability to analyze literary works: a poem analysis, a prose fiction passage analysis, and a concept, issue, or element analysis of a literary work.

From your course or review practices, you should know how to construct a clear, organized essay that defends a focused claim about the work under analysis. Your should structure your essay with a brief introduction that includes the thesis statement, followed by body paragraphs that further the thesis statement with detailed, well-discussed support, and a short concluding paragraph that reiterates and reinforces the thesis statement without repeating it. Clear organization, specific support, and full explanations or discussions are three critical components of high-scoring essays.

General Tips to Bettering Your Odds at a Nine on the AP® English Literature and Composition Exam.

Your teacher may have already told you how to approach the poetry analysis, but for the poetry essay, it’s important to keep the following in mind coming into the exam:

- Carefully read, review, and underline key to-do’s in the prompt.

- Briefly outline where you’re going to hit each prompt item–in other words, pencil out a specific order.

- Be sure you have a clear thesis that includes the terms mentioned in the instructions, literary devices, tone, and meaning.

- Include the author’s name and title of the poem in your thesis statement.

- Use quotes—lots of them—to exemplify the elements throughout the essay.

- Fully explain or discuss how your element examples support your thesis. A deeper, fuller, and focused explanation of fewer elements is better than a shallow discussion of more elements (shotgun approach).

- Avoid vague, general statements for a clear focus on the poem itself.

- Use transitions to connect sentences and paragraphs.

- Write in the present tense with generally good grammar.

- Keep your introduction and conclusion short, and don’t repeat your thesis verbatim in your conclusion.

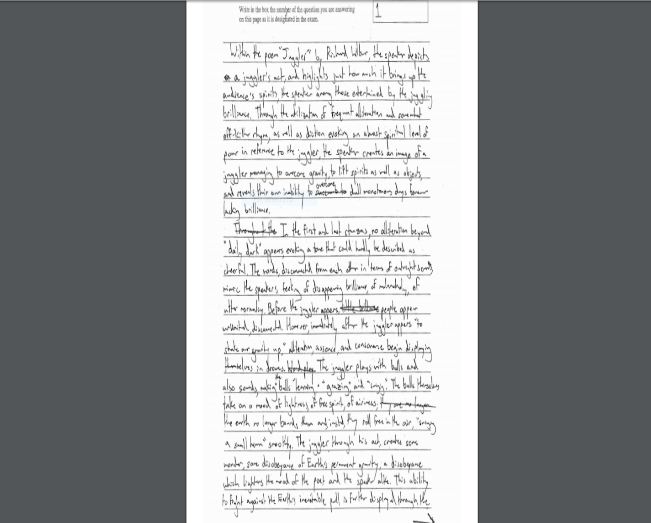

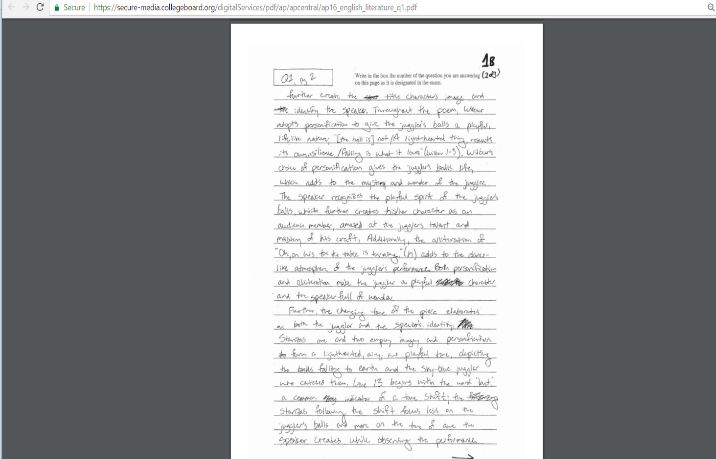

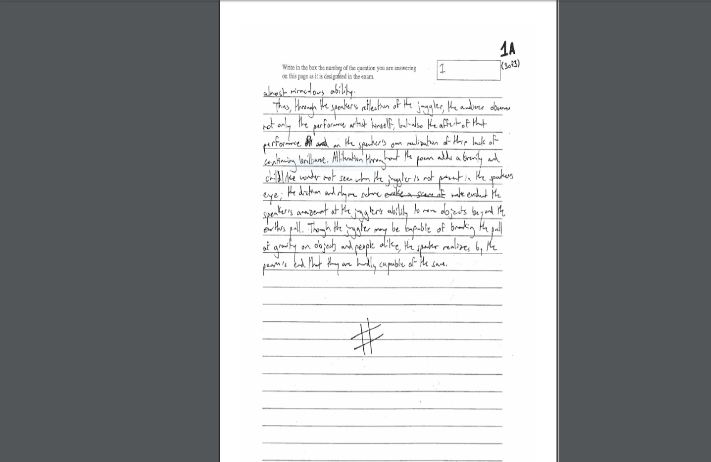

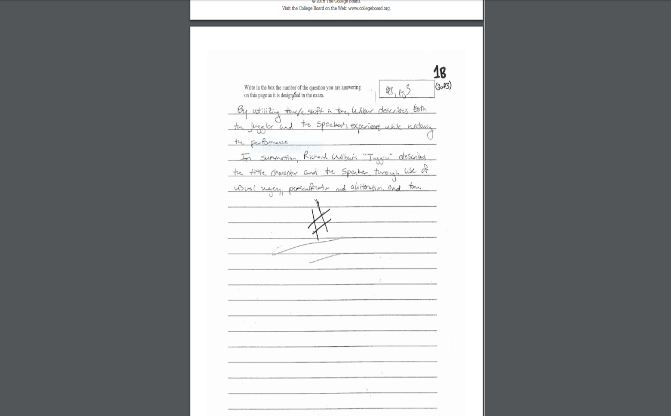

The newly-released 2016 sample AP® English Literature and Composition exam questions, sample responses, and grading rubrics provide a valuable opportunity to analyze how to achieve high scores on each of the three Section II FRQ responses. However, for purposes of this examination, the Poetry Analysis strategies will be the focus. The poem for analysis in last year’s exam was “The Juggler” by Richard Wilbur, a modern American poet. Exam takers were asked to analyze the following:

- how the speaker in the poem describes the juggler

- what the description shows about the speaker

- how the poet uses imagery, figurative language, and tone to convey meaning

When you analyze the components of an influential essay, it’s helpful to compare all three sample answers provided by the CollegeBoard: the high scoring (A) essay, the mid-range scoring (B) essay, and the low scoring (C) essay. All three provide a teaching opportunity for achieving a nine on the poetry analysis essay.

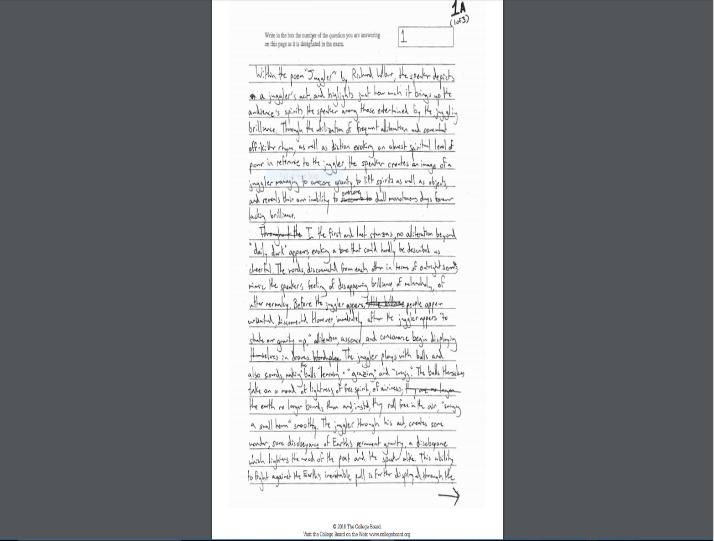

Start with a Succinct Introduction that Includes Your Thesis Statement

The first sample essay, the A essay, quickly and succinctly introduces the author, title, thesis, elements, and devices. The writer’s introduction sentences are efficient: they contain no waste and give the reader a sense of the cohesiveness of the argument, including the role of each of the analyzed components in proving the thesis. The specificity of the details in the introduction shows that the writer is in control, with phrases like “frequent alliteration,” “off-kilter rhyme”, and “diction evoking an almost spiritual level of power”. The writer leaves nothing to guesswork.

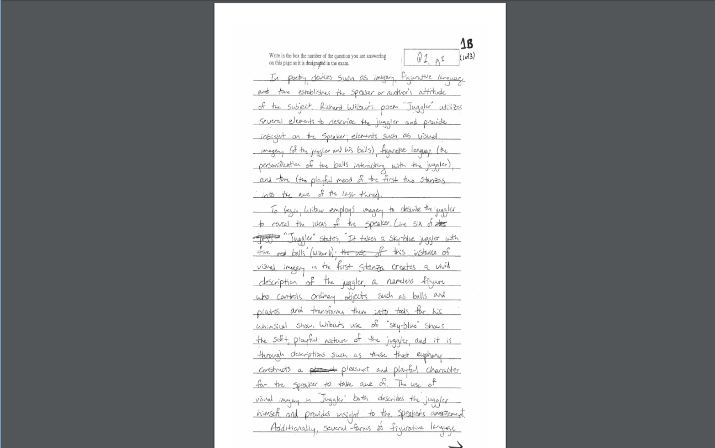

The mid-range B essay introduction also cites some specific details in the poem, like “visual imagery (of the juggler and his balls), figurative language (the personification of the balls interacting with the juggler), and tone (the playful mood of the first two stanza)”. However, the writer wastes space and precious time (five whole lines!) with a vague and banal recitation of the prompt. The mid-range answer also doesn’t give the reader an understanding of an overarching thesis that he or she will use the elements and devices to support, merely a reference to the speaker’s “attitude”.

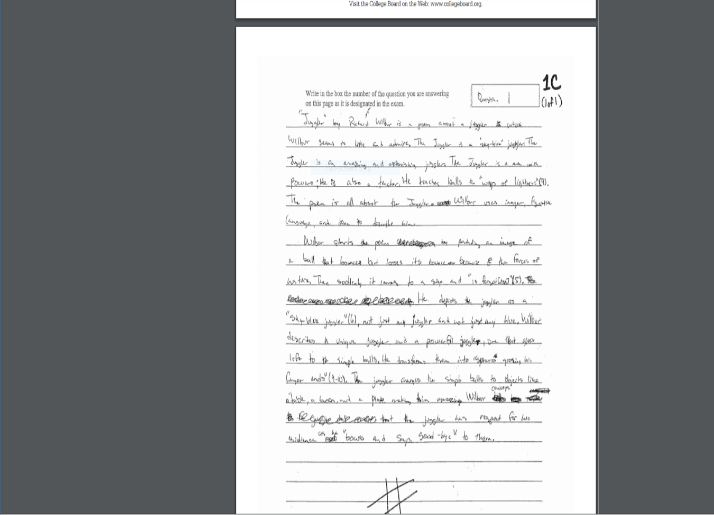

The third sample lacks cohesiveness, a thesis statement, and organization. The sentences read like a shotgun spray of facts and descriptions that give no direction to the reader of the writer’s approach: how he or she will use the elements and details listed to prove a thesis. The short, choppy sentences don’t connect, and the upshot is something so commonplace as Wilbur describes a talented juggler, who is also a powerful teacher. That doesn’t respond to the prompt, which requires an argument about what the juggler’s description reveals about the speaker.

To sum up, make introductions brief and compact, using specific details from the poem and a clear direction that address the call of the prompt. Writing counts. Short, choppy, disconnected sentences make an incoherent, unclear paragraph. Don’t waste time on sentences that don’t do the work ahead for you. Cut to the chase; be specific.

Use Clear Examples to Support Your Argument Points

The A answer first supports the thesis by pointing out that alliteration and rhyme scheme depict the mood and disconnection of both the speaker and the crowd. The writer does this by noting how alliteration appears when the juggler performs, but not before. The student also notes how the mood and connection to the crowd cohere when the juggler juggles, the balls defying gravity and uplifting the crowd with the balls. Then, the writer wraps up the first point about description, devices, and elements by concluding that the unusual rhyme scheme echoes the unusual feat of juggling and controlling the mood of the crowd.

With a clear focus on attaching devices to individually quoted phrases and poem details, the student leads the reader through the first pass at proving the attitude of the poem’s speaker while commenting on possible meanings the tone, attitude, and devices suggest. Again, the student uses clear, logical, and precise quotes and references to the poem without wasting time on unsupported statements. Specific illustrations anchor each point.

For example, the student identifies the end rhyme as an unusual effect that mimics the unusual and gravity-defiant balls. Tying up the first paragraph, the student then goes on to thoroughly explain the connection between the cited rhyme scheme, the unique defiance of gravity, and the effect on the speaker. The organizational plan is as follows: point (assertion), illustration, and explanation.

The mid-range sample also cites specific details of the poem, such as the “sky-blue” juggler, a color that suggests playfulness, but then only concludes that euphony shows the speaker’s attitude toward the juggler without making that connection clear with an explanation. The writer simply concludes without proving that assertion. Without further explanation or exemplification, the author demonstrates no knowledge of the term “euphony”.

Sample C also alludes to the “sky-blue” juggler but doesn’t explain the significance. In fact, the writer makes a string of details from the poem appear significant without actually revealing anything about the details the writer notes. They’re merely a string of details.

Discussion is Crucial to Connect Your Quotes and Examples to Your Argument Points

Rather than merely noting quoted phrases and lines without explanation, the A response takes the time to thoroughly discuss the meaning of the quoted words, phrases, and sentences used to exemplify his or her assertions. For example, the second paragraph begins with an assertion that the speaker’s view of the world is evident through the diction used when describing the juggler and the juggler’s act. Immediately, the writer supplies proof by directing the reader to the first and last stanzas to find “lens,” “dusk”, and “daily dark”.

The selection of these particular diction choices demonstrates the writer’s knowledge of the term “diction” and how to support a conclusion the student will make by the end of the sentence that the speaker’s attitude toward the world around him is “not the brightest”. The writer gives a follow-up sentence to further convince the reader of the previous point about the speaker’s dim view by adding, “All the words and phrases used just fall flat, filled with connotations of dullness…”

Using the transition, “however”, the A response goes on to further explain that the juggler’s description contrasts with that of the speaker’s in its lightness, by again providing both specifically-quoted words and complete one or two full sentence follow-ups to the examples. In that way, the writer clarifies the connection between the examples and their use and meaning. Nothing is left unexplained–unlike the B response, which claims Wilbur uses personification, then gives a case of a quoted passage about the balls not being “lighthearted”.

After mentioning the term, the B essay writer merely concludes that Wilbur used personification without making the connection between “lighthearted” and personification. The writer might have written one additional sentence to show that balls as inanimate objects don’t have the emotions to be cheery nor lighthearted, only humans do. Thus, Wilbur personifies the balls. Likewise short of support, the writer concludes that the “life” of the balls through personification adds to the mystery and wonder–without further identifying the wonder or whose wonder and how that wonder results from the life of the balls.

Write a Brief Conclusion

While it’s more important to provide a substantive, organized, and clear argument throughout the body paragraphs than it is to conclude, a conclusion provides a satisfying rounding out of the essay and last opportunity to hammer home the content of the preceding paragraphs. If you run out of time for a conclusion because of the thorough preceding paragraphs, that is not as fatal to your score as not concluding or not concluding as robustly as the A essay sample (See the B essay conclusion).

The A response not only provides a quick but sturdy recap of all the points made throughout the body paragraphs (without repeating the thesis statement) but also reinforces those points by repeating them as the final parting remarks to the reader. The writer demonstrates not only the points made but the order of their appearance, which also showcases the overall structure of the essay.

Finally, a conclusion compositionally rounds out a gracious essay–polite because it considers the reader. You don’t want your reader to have to work hard to understand any part of your essay. By repeating recapped points, you help the reader pull the argument together and wrap up.

Write in Complete Sentences with Proper Punctuation and Compositional Skills

Though pressed for time, it’s important to write an essay with clear, correctly punctuated sentences and properly spelled words. Strong compositional skills create a favorable impression to the reader, like using appropriate transitions or signals (however, therefore) to tie sentences and paragraphs together, making the relationships between sentences clear (“also”–adding information, “however”–contrasting an idea in the preceding sentence).

Starting each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that previews the main idea or focus of the paragraph helps you the writer and the reader keep track of each part of your argument. Each section furthers your points on the way to convincing your reader of your argument. If one point is unclear, unfocused, or grammatically unintelligible, like a house of cards, the entire argument crumbles. Good compositional skills help you lay it all out orderly, clearly, and fully.

For example, the A response begins the first body paragraph with “In the first and last stanzas, no alliteration beyond ‘daily dark’ appears, evoking a tone that could hardly be described as cheerful”. The sentence, with grammatically-correct commas inserted to section off the lead-in phrase, “In the first and last stanzas,” as well as the dependent clause at the sentence’s end, “evoking a tone that…,” gives a road map to the reader as to the paragraph’s design: alliteration, tone, darkness. Then the writer hits all three of those with a complete explanation.

The next paragraph begins with a rather clunky, unwieldy sentence that nevertheless does the same as the first–keys the reader to the first point regarding the speaker’s view of the world and the devices and elements used to do so. It’s clear the writer tackles the speaker’s view, the juggler’s depiction, and diction choice–both as promised from the beginning in the thesis statement of the introductory paragraph and per the prompt. The writer uses the transition “In the first and last stanzas”, to tie the topic sentence to the examples he or she will use to prove the topic sentence; then the writer is off to do the same in the next paragraph.

So by the time the conclusion takes the reader home, the writer has done all of the following:

- followed the prompt

- followed the propounded thesis statement in exact order promised

- provided a full discussion with examples

- included quotes proving each assertion

- used clear, grammatically correct sentences

- wrote paragraphs ordered by a thesis statement

- created topic sentences for each paragraph

- ensured each topic sentence furthered the ideas presented in the thesis statement

Have a Plan and Follow it

It’s easier than it sounds. To get a 9 on the poetry analysis essay in the AP® Literature and Composition exam, practice planning a response under strict time deadlines. Write as many practice essays as you can. Follow the same procedure each time.

First, be sure to read the instructions carefully, highlighting the parts of the prompt you absolutely must cover. Then map out a scratch outline of the order you intend to cover each point in support of your argument. Try and include not only a clear thesis statement, written as a complete sentence but the topic sentences to each paragraph followed by the quotes and details you’ll use to support the topic sentences. Then follow your map faithfully.

Be sure to give yourself enough time to give your essay a brief re-read to catch mechanical errors, missing words, or necessary insertions to clarify an incomplete or unclear thought. With time, an organized approach, and plenty of practice, earning a nine on the poetry analysis is manageable. Be sure to ask your teacher or consult other resources, like albert.io’s Poetic Analysis practice essays, if you’re unsure how to identify poetic devices and elements in poetry, or need more practice writing a poetry analysis.

Looking for AP® English Literature practice?

Kickstart your AP® English Literature prep with Albert. Start your AP® exam prep today .

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

AP English Literature and Composition Exam Questions. Free-Response Questions and Scoring Information. Download free-response questions from past exams along with scoring guidelines, sample responses from exam takers, and scoring distributions.

Craft a Compelling Thesis. No matter the prompt, you will always need to respond with a substantive thesis. A meaty thesis contains complexity rather than broad generalizations, and points to specifics in the poem. By examining the colloquial language in Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem, “We Real Cool”, we can see the tension of choosing to be “cool”.

Question 1: Poetry Analysis. 6 points. In Richard Blanco’s poem “Shaving,” published in 1998, the speaker writes about the act of shaving. Read the poem carefully. Then, in a well-written essay, analyze how Blanco uses literary elements and techniques to develop the speaker’s complex associations with the ritual of shaving.

The thesis presented in the introductory paragraph of this essay offers a defensible interpretation of the poem and presents a complex idea: “Illuminating the inherent need not only for appreciation of the little things, but of humans for one another, ‘The Man with the Saxophone’ demonstrates the affect of external events on internal emotions.”

In this video, I'll show you how to write the AP English Literature poetry essay (Q1) step by step using the actual 2018 prompt. Watch me annotate the poem given, identify literary...

• Finally, writing a well-organized essay means understanding how their own thoughts about the text are connected, being able to support those assertions with clear, concrete examples, and cueing the reader with the appropriate compositional establishing a thesis and using transitional devices. Sample: 1A Score: 8 This essay offers

The key to helping students earn the thesis point on the AP Literature Rubric is to help them understand that they are writing a literary argument and that an argument by its very nature has two sides or two part.

Sample SS. [1] “The Landlady” poem analyze the speakers complex portrayal by using elements as imagery, diction, and a style of quatrain. [2] The auther organize the poem in a quatrain form and having a lots of stops at the end of the lines causing toughts and curiosity.

Well, with essay writing we start small — on the sentence-level — at the beginning of the year, working to achieve mastery over thesis statements, evidence, and commentary. Multiple-choice practice is always completed in class, on paper and while scores are recorded, they never go in the grade book.

All three provide a teaching opportunity for achieving a nine on the poetry analysis essay. Start with a Succinct Introduction that Includes Your Thesis Statement. The first sample essay, the A essay, quickly and succinctly introduces the author, title, thesis, elements, and devices.