Internet Explorer is no longer supported by Microsoft. To browse the NIHR site please use a modern, secure browser like Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, or Microsoft Edge.

How to disseminate your research

Published: 01 January 2019

Version: Version 1.0 - January 2019

This guide is for researchers who are applying for funding or have research in progress. It is designed to help you to plan your dissemination and give your research every chance of being utilised.

What does NIHR mean by dissemination?

Effective dissemination is simply about getting the findings of your research to the people who can make use of them, to maximise the benefit of the research without delay.

Research is of no use unless it gets to the people who need to use it

Professor Chris Whitty, Chief Scientific Adviser for the Department of Health

Principles of good dissemination

Stakeholder engagement: Work out who your primary audience is; engage with them early and keep in touch throughout the project, ideally involving them from the planning of the study to the dissemination of findings. This should create ‘pull’ for your research i.e. a waiting audience for your outputs. You may also have secondary audiences and others who emerge during the study, to consider and engage.

Format: Produce targeted outputs that are in an appropriate format for the user. Consider a range of tailored outputs for decision makers, patients, researchers, clinicians, and the public at national, regional, and/or local levels as appropriate. Use plain English which is accessible to all audiences.

Utilise opportunities: Build partnerships with established networks; use existing conferences and events to exchange knowledge and raise awareness of your work.

Context: Understand the service context of your research, and get influential opinion leaders on board to act as champions. Timing: Dissemination should not be limited to the end of a study. Consider whether any findings can be shared earlier

Remember to contact your funding programme for guidance on reporting outputs .

Your dissemination plan: things to consider

What do you want to achieve, for example, raise awareness and understanding, or change practice? How will you know if you are successful and made an impact? Be realistic and pragmatic.

Identify your audience(s) so that you know who you will need to influence to maximise the uptake of your research e.g. commissioners, patients, clinicians and charities. Think who might benefit from using your findings. Understand how and where your audience looks for/receives information. Gain an insight into what motivates your audience and the barriers they may face.

Remember to feedback study findings to participants, such as patients and clinicians; they may wish to also participate in the dissemination of the research and can provide a powerful voice.

When will dissemination activity occur? Identify and plan critical time points, consider external influences, and utilise existing opportunities, such as upcoming conferences. Build momentum throughout the entire project life-cycle; for example, consider timings for sharing findings.

Think about the expertise you have in your team and whether you need additional help with dissemination. Consider whether your dissemination plan would benefit from liaising with others, for example, NIHR Communications team, your institution’s press office, PPI members. What funds will you need to deliver your planned dissemination activity? Include this in your application (or talk to your funding programme).

Partners / Influencers: think about who you will engage with to amplify your message. Involve stakeholders in research planning from an early stage to ensure that the evidence produced is grounded, relevant, accessible and useful.

Messaging: consider the main message of your research findings. How can you frame this so it will resonate with your target audience? Use the right language and focus on the possible impact of your research on their practice or daily life.

Channels: use the most effective ways to communicate your message to your target audience(s) e.g. social media, websites, conferences, traditional media, journals. Identify and connect with influencers in your audience who can champion your findings.

Coverage and frequency: how many people are you trying to reach? How often do you want to communicate with them to achieve the required impact?

Potential risks and sensitivities: be aware of the relevant current cultural and political climate. Consider how your dissemination might be perceived by different groups.

Think about what the risks are to your dissemination plan e.g. intellectual property issues. Contact your funding programme for advice.

More advice on dissemination

We want to ensure that the research we fund has the maximum benefit for patients, the public and the NHS. Generating meaningful research impact requires engaging with the right people from the very beginning of planning your research idea.

More advice from the NIHR on knowledge mobilisation and dissemination .

What you need to know about research dissemination

Last updated

5 March 2024

Reviewed by

In this article, we'll tell you what you need to know about research dissemination.

- Understanding research dissemination

Research that never gets shared has limited benefits. Research dissemination involves sharing research findings with the relevant audiences so the research’s impact and utility can reach its full potential.

When done effectively, dissemination gets the research into the hands of those it can most positively impact. This may include:

Politicians

Industry professionals

The general public

What it takes to effectively disseminate research will depend greatly on the audience the research is intended for. When planning for research dissemination, it pays to understand some guiding principles and best practices so the right audience can be targeted in the most effective way.

- Core principles of effective dissemination

Effective dissemination of research findings requires careful planning. Before planning can begin, researchers must think about the core principles of research dissemination and how their research and its goals fit into those constructs.

Research dissemination principles can best be described using the 3 Ps of research dissemination.

This pillar of research dissemination is about clarifying the objective. What is the goal of disseminating the information? Is the research meant to:

Persuade policymakers?

Influence public opinion?

Support strategic business decisions?

Contribute to academic discourse?

Knowing the purpose of sharing the information makes it easy to accurately target it and align the language used with the target audience.

The process includes the methods that will be used and the steps taken when it comes time to disseminate the findings. This includes the channels by which the information will be shared, the format it will be shared in, and the timing of the dissemination.

By planning out the process and taking the time to understand the process, researchers will be better prepared and more flexible should changes arise.

The target audience is whom the research is aimed at. Because different audiences require different approaches and language styles, identifying the correct audience is a huge factor in the successful dissemination of findings.

By tailoring the research dissemination to the needs and preferences of a specific audience, researchers increase the chances of the information being received, understood, and used.

- Types of research dissemination

There are many options for researchers to get their findings out to the world. The type of desired dissemination plays a big role in choosing the medium and the tone to take when sharing the information.

Some common types include:

Academic dissemination: Sharing research findings in academic journals, which typically involves a peer-review process.

Policy-oriented dissemination: Creating documents that summarize research findings in a way that's understandable to policymakers.

Public dissemination: Using television and other media outlets to communicate research findings to the public.

Educational dissemination: Developing curricula for education settings that incorporate research findings.

Digital and online dissemination: Using digital platforms to present research findings to a global audience.

Strategic business presentation: Creating a presentation for a business group to use research insights to shape business strategy

- Major components of information dissemination

While the three Ps provide a convenient overview of what needs to be considered when planning research dissemination, they are not a complete picture.

Here’s a more comprehensive list of what goes into the dissemination of research results:

Audience analysis: Identifying the target audience and researching their needs, preferences, and knowledge level so content can be tailored to them.

Content development: Creating the content in a way that accurately reflects the findings and presents them in a way that is relevant to the target audience.

Channel selection: Choosing the channel or channels through which the research will be disseminated and ensuring they align with the preferences and needs of the target audience.

Timing and scheduling: Evaluating factors such as current events, publication schedules, and project milestones to develop a timeline for the dissemination of the findings.

Resource allocation: With the basics mapped out, financial, human, and technological resources can be set aside for the project to facilitate the dissemination process.

Impact assessment and feedback: During the dissemination, methods should be in place to measure how successful the strategy has been in disseminating the information.

Ethical considerations and compliance: Research findings often include sensitive or confidential information. Any legal and ethical guidelines should be followed.

- Crafting a dissemination blueprint

With the three Ps providing a foundation and the components outlined above giving structure to the dissemination, researchers can then dive deeper into the important steps in crafting an impactful and informative presentation.

Let’s take a look at the core steps.

1. Identify your audience

To identify the right audience for research dissemination, researchers must gather as much detail as possible about the different target audience segments.

By gathering detailed information about the preferences, personalities, and information-consumption habits of the target audience, researchers can craft messages that resonate effectively.

As a simple example, academic findings might be highly detailed for scholarly journals and simplified for the general public. Further refinements can be made based on the cultural, educational, and professional background of the target audience.

2. Create the content

Creating compelling content is at the heart of effective research dissemination. Researchers must distill complex findings into a format that's engaging and easy to understand. In addition to the format of the presentation and the language used, content includes the visual or interactive elements that will make up the supporting materials.

Depending on the target audience, this may include complex technical jargon and charts or a more narrative approach with approachable infographics. For non-specialist audiences, the challenge is to provide the required information in a way that's engaging for the layperson.

3. Take a strategic approach to dissemination

There's no single best solution for all research dissemination needs. What’s more, technology and how target audiences interact with it is constantly changing. Developing a strategic approach to sharing research findings requires exploring the various methods and channels that align with the audience's preferences.

Each channel has a unique reach and impact, and a particular set of best practices to get the most out of it. Researchers looking to have the biggest impact should carefully weigh up the strengths and weaknesses of the channels they've decided upon and craft a strategy that best uses that knowledge.

4. Manage the timeline and resources

Time constraints are an inevitable part of research dissemination. Deadlines for publications can be months apart, conferences may only happen once a year, etc. Any avenue used to disseminate the research must be carefully planned around to avoid missed opportunities.

In addition to properly planning and allocating time, there are other resources to consider. The appropriate number of people must be assigned to work on the project, and they must be given adequate financial and technological resources. To best manage these resources, regular reviews and adjustments should be made.

- Tailoring communication of research findings

We’ve already mentioned the importance of tailoring a message to a specific audience. Here are some examples of how to reach some of the most common target audiences of research dissemination.

Making formal presentations

Content should always be professional, well-structured, and supported by data and visuals when making formal presentations. The depth of information provided should match the expertise of the audience, explaining key findings and implications in a way they'll understand. To be persuasive, a clear narrative and confident delivery are required.

Communication with stakeholders

Stakeholders often don't have the same level of expertise that more direct peers do. The content should strike a balance between providing technical accuracy and being accessible enough for everyone. Time should be taken to understand the interests and concerns of the stakeholders and align the message accordingly.

Engaging with the public

Members of the public will have the lowest level of expertise. Not everyone in the public will have a technical enough background to understand the finer points of your message. Try to minimize confusion by using relatable examples and avoiding any jargon. Visual aids are important, as they can help the audience to better understand a topic.

- 10 commandments for impactful research dissemination

In addition to the details above, there are a few tips that researchers can keep in mind to boost the effectiveness of dissemination:

Master the three Ps to ensure clarity, focus, and coherence in your presentation.

Establish and maintain a public profile for all the researchers involved.

When possible, encourage active participation and feedback from the audience.

Use real-time platforms to enable communication and feedback from viewers.

Leverage open-access platforms to reach as many people as possible.

Make use of visual aids and infographics to share information effectively.

Take into account the cultural diversity of your audience.

Rather than considering only one dissemination medium, consider the best tool for a particular job, given the audience and research to be delivered.

Continually assess and refine your dissemination strategies as you gain more experience.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Reserve a study room

- Library Account

- Undergraduate Students

- Graduate Students

- Faculty & Staff

Create a Research Dissemination Plan

Why create a dissemination plan, dissemination planning resources.

- Dissemination Plan Examples

- Dissemination Plan Template

- Guide Background

Questions or Suggestions?

There are a number of reasons to create a dissemination plan:

Applying for a grant and need a research guide? Dissemination plans are required in many grants.

Wanting to share your process or findings with and beyond the academic community.

Connecting with others who share key areas of research interest and those who may enhance your research by providing new ideas.

Enhancing usability of research by other researchers as well as end users.

Sharing research with the public as a part of our mission as a public research university.

Developing and a disseminating a body of work that creates depth in the field, facilitates tenor, allows faculty to be expert source of research area.

Dissemination planning can help expand your thinking about what research you share, how you share it, and who you share it with. Planning can also help expand access to your research, and ultimately, increase its impact.

PHCRIS (Primary Health Care Research & Information Service). Introduction to Research Dissemination.

This guide will introduce the terminology and definitions surrounding research dissemination, as well as provide you with strategies and further resources to aid your dissemination planning.

Dissemination Planning Tool. AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation.

This tool was developed to help researchers evaluate their research and develop appropriate dissemination plans, if the research is determined to have "real world" impact. It is designed to prompt your thinking about the processes that you would use to disseminate your findings or products, beyond publishing and presenting in peer-reviewed venues.

CARE (Community Alliance for Research and Engagement). Beyond Scientific Publication: Strategies for Disseminating Research Findings.

This document provides key strategies for dissemination, including practical advice and specific templates you can adapt for your use.

URegina Exchanging Knowledge. A Research Dissemination Toolkit.

This toolkit provides a dissemination plan worksheet, tips for effective dissemination, and further resources to aid your dissemination planning.

Becker Medical Library Model for Assessment of Research Impact

The Becker Medical Library Model for Assessment of Research Impact model is a framework for tracking diffusion of research outputs and activities to locate indicators that demonstrate evidence of biomedical research impact. It is intended to be used as a supplement to publication analysis. Using the Becker Model in tandem with publication analysis provides a more robust and comprehensive perspective of biomedical research impact. The Becker Model also includes guidance for quantifying and documenting research impact as well as resources for locating evidence of impact.

- Next: Dissemination Plan Examples >>

- Last Updated: Nov 20, 2023 11:33 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.vcu.edu/dissemination

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

16 21. Qualitative research dissemination

Chapter outline.

- Ethical responsibility and cultural respectfulness (8 minute read time)

- Critical considerations (5 minute read time)

- Informing your dissemination plan (11 minute read time)

- Final product taking shape (10 minute read time)

Content warning: Examples in this chapter contain references to research as a potential tool to stigmatize or oppress vulnerable groups, mistreatment and inequalities experienced by Native American tribes, sibling relationships, caregiving, child welfare, criminal justice and recidivism, first generation college students, Covid-19, school culture and race, health (in)equity, physical and sensory abilities, and transgender youth.

Your sweat and hard work has paid off! You’ve planned your study, collected your data, and completed your analysis. But alas, no rest for the weary student researcher. Now you need to share your findings. As researchers, we generally have some ideas where and with whom we desire to share our findings, but these plans may evolve and change during our research process. Communicating our findings with a broader audience is a critical step in the research process, so make sure not to treat this like an afterthought. Remember, research is about making a contribution to collective knowledge-building in the area of study that you are interested in. Indeed, research is of no value if there is no audience to receive it. You worked hard…get those findings out there!

In planning for this phase of research, we can consider a variety of methods for sharing our study findings. Among other options, we may choose to write our findings up as an article in a professional journal, provide a report to an organization, give testimony to a legislative group, or create a presentation for a community event. We will explore these options in a bit more detail below in section 21.4 where we talk more about different types of qualitative research products. We also want to think about our intended audience.

For your research, answer these two key questions as you are planning for dissemination:

- Who are you targeting to communicate your findings to? In other words, who needs to hear the results of your study?

- What do you hope your audience will take away after learning about your study?

21.1 Ethical responsibility and cultural respectfulness

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Identify key ethical considerations in developing their qualitative research dissemination plan

- Conceptualize how research dissemination may impact diverse groups, both presently and into the future

Have you ever been misrepresented or portrayed in a negative light? It doesn’t feel good. It especially doesn’t feel good when the person portraying us has power, control and influence. While you might not feel powerful, research can be a powerful tool, and can be used and abused for many ends. Once research is out in the world, it is largely out of our control, so we need to approach dissemination with care. Be thoughtful about how you represent your work and take time to think through the potential implications it may have, both intended and unintended, for the people it represents.

As alluded to in the paragraph above, research comes with hefty responsibilities. You aren’t off the hook if you are conducting quantitative research. While quantitative research deals with numbers, these numbers still represent people and their relationships to social problems. However, with qualitative research, we are often dealing with a smaller sample and trying to learn more from them. As such, our job often carries additional weight as we think about how we will represent our findings and the people they reflect. Furthermore, we probably hope that our research has an impact; that in some way, it leads to change around some issue. This is especially true as social work researchers. Our research often deals with oppressed groups, social problems, and inequality. However, it’s hard to predict the implications that our research may have. This suggests that we need to be especially thoughtful about how we present our research to others.

Two of the core values of social work involve respecting the inherent dignity and worth of each person, practicing with integrity, and behaving in a trustworthy manner [1] . As social work researchers, to uphold these values, we need to consider how we are representing the people we are researching. Our work needs to honestly and accurately reflect our findings, but it also needs to be sensitive and respectful to the people it represents. In Chapter 8 we discussed research ethics and introduced the concept of beneficence or the idea that research needs to support the welfare of participants. Beneficence is particularly important as we think about our findings becoming public and how the public will receive, interpret and use this information. Thus, both as social workers and researchers, we need to be conscientious of how dissemination of our findings takes place.

As you think about the people in your sample and the communities or groups to which they belong, consider some of these questions:

- How are participants being portrayed in my research?

- What characteristics or findings are being shared or highlighted in my research that may directly or indirectly be associated with participants?

- Have the groups that I am researching been stigmatized, stereotyped, and/or misrepresented in the past? If so, how does my research potentially reinforce or challenge these representations?

- How might my research be perceived or interpreted by members of the community or group it represents?

- In what ways does my research honor the dignity and worth of participants?

Qualitative research often has a voyeuristic quality to it, as we are seeking a window into participants’ lives by exploring their experiences, beliefs, and values. As qualitative researchers, we have a role as stewards or caretakers of data. We need to be mindful of how data are gathered, maintained, and most germane to our conversation here, how data are used. We need to craft research products that honor and respect individual participants (micro), our collective sample as a whole (meso), and the communities that our research may represent (macro).

As we prepare to disseminate our findings, our ethical responsibilities as researchers also involve honoring the commitments we have made during the research process. We need to think back to our early phases of the research process, including our initial conversations with research partners and other stakeholders who helped us to coordinate our research activities. If we made any promises along the way about how the findings would be presented or used, we need to uphold them here. Additionally, we need to abide by what we committed to in our informed consent . Part of our informed consent involves letting participants know how findings may be used. We need to present our findings according to these commitments. We of course also have a commitment to represent our research honestly.

As an extension of our ethical responsibilities as researchers, we need to consider the impact that our findings may have, as well as our need to be socially conscientious researchers. As scouts, we were taught to leave our campsite in a better state than when we arrived. I think it is helpful to think of research in these terms. Think about the group(s) that may be represented by your research; what impact might your findings have for the lives of members of this group? Will it leave their lives in a better state than before you conducted your research? As a responsible researcher, you need to be thoughtful, aware and realistic about how your research findings might be interpreted and used by others. As social workers, while we hope that findings will be used to improve the lives of our clients, we can’t ignore that findings can also be used to further oppress or stigmatize vulnerable groups; research is not apolitical and we should not be naive about this. It is worth mentioning the concept of sustainable research here. Sustainable research involves conducting research projects that have a long-term, sustainable impact for the social groups we work with. As researchers, this means that we need to actively plan for how our research will continue to benefit the communities we work with into the future. This can be supported by staying involved with these communities, routinely checking-in and seeking input from community members, and making sure to share our findings in ways that community members can access, understand, and utilize them. Nate Olson provides a very inspiring Ted Talk about the importance of building resilient communities. As you consider your research project, think about it in these terms.

Key Takeaways

- As you think about how best to share your qualitative findings, remember that these findings represent people. As such, we have a responsibility as social work researchers to ensure that our findings are presented in honest, respectful, and culturally sensitive ways.

- Since this phase of research deals with how we are going to share our findings with the public, we need to actively consider the potential implications of our research and how it may be interpreted and used.

Is your work, in some way, helping to contribute to a resilient and sustainable community? It may not be a big tangible project as described in Olson’s Ted Talk , but is it providing a resource for change and growth to a group of people, either directly or indirectly? Does it promote sustainability amongst the social networks that might be impacted by the research you are conducting?

21.2 Critical considerations

- Identify how issues of power and control are present in the dissemination of qualitative research findings

- Begin to examine and account for their own role in the qualitative research process, and address this in their findings

This is the part of our research that is shared with the public and because of this, issues like reciprocity, ownership, and transparency are relevant. We need to think about who will have access to the tangible products of our research and how that research will get used. As researchers, we likely benefit directly from research products; perhaps it helps us to advance our career, obtain a good grade, or secure funding. Our research participants often benefit indirectly by advancing knowledge about a topic that may be relevant or important to them, but often don’t experience the same direct tangible benefits that we do. However, a participatory perspective challenges us to involve community members from the outset in discussions about what changes would be most meaningful to their communities and what research products would be most helpful in accomplishing those changes. This is especially important as it relates to the role of research as a tool to support empowerment.

Ownership of research products is also important as an issue of power and control. We will discuss a range of venues for presenting your qualitative research, some of which are more amenable to shared ownership than others. For instance, if you are publishing your findings in an academic journal, you will need to sign an agreement with that publisher about how the information in that article can be used and who has access to it. Similarly, if you are presenting findings at a national conference, travel and other conference-related expenses and requirements may make access to these research products prohibitive. In these instances, the researcher and the organization(s) they negotiate with (e.g. the publishing company, the conference organizing body) share control. However, disseminating qualitative findings in a public space, public record, or community-owned resource means that more equitable ownership might be negotiated. An equitable or reciprocal arrangement might not always be able to be reached, however. Transparency about who owns the products of research is important if you are working with community partners. To support this, establishing a Memorandum Of Understanding (MOU) or Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) e arly in the research process is important. This document should clearly articulate roles, responsibilities, and a number of other details, such as ownership of research products between the researcher and the partnering group(s).

Resources for learning more about MOUs and MOAs

Center for Community Health and Development, University of Kansas. (n.d.). Community toolbox: Section 9. Understanding and writing contracts and memoranda of agreement [Webpage]. https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/structure/organizational-structure/understanding-writing-contracts-memoranda-agreement/main

Collaborative Center for Health Equity, University of Wisconson Madison. (n.d.). Standard agreement for research with community organizations [Template] https://d1uqjtzsuwlnsf.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/163/2018/08/CCHE-UW-MOU-sample.pdf

Office of Research, UC Davis. (n.d.). Research MOUs [Webpage]. https://research.ucdavis.edu/proposals-grants-contracts/international-agreements/memorandum-understanding/

Office of Research, The University of Texas at Dallas. (n.d.). Types of agreements [Webpage]. https://research.utdallas.edu/researchers/contracts/types-of-agreements

In our discussion about qualitative research, we have also frequently identified the need for the qualitative researcher to account for their role throughout the research process. Part of this accounting can specifically apply to qualitative research products. This is our opportunity to demonstrate to our audience that we have been reflective throughout the course of the study and how this has influenced the work we did. Some qualitative research studies include a positionality statement within the final product. This is often toward the beginning of the report or the presentation and includes information about the researcher(s)’s identity and worldview, particularly details relevant to the topic being studied. This can include why you are invested in the study, what experiences have shaped how you have come to think about the topic, and any positions or assumptions you make with respect to the topic. This is another way to encourage transparency. It can also be a means of relegating or at least acknowledging some of our power in the research process, as it can provide one modest way for us, as the researcher, to be a bit more exposed or vulnerable, although this is a far cry from making the risks of research equitable between the researcher and the researched. However, the positionality statement can be a place to integrate our identities, who we are as an individual, a researcher, and a social work practitioner. Granted, for some of us that might be volumes, but we need to condense this down to a brief but informative statement – don’t let it eclipse the research! It should just be enough to inform the audience and allow them to draw their own conclusions about who is telling the story of this research and how well they can be trusted. This student provides a helpful discussion of the positionality statement that she developed for her study. Reviewing your reflexive journal (discussed in chapter 20 as a tool to enhance qualitative rigor) can help in identifying underlying assumptions and positions you might have grounded in your reactions throughout the research process. These insights can be integrated into your positionality statement. Please take a few minutes to watch this informative video of a student further explaining what a positionality statement is and providing a good example of one.

- The products of qualitative research often benefit the researcher disproportionately when compared to research participants or the communities they represent. Whenever possible, we can seek out ways to disseminate research in ways that addresses this imbalance and supports more tangible and direct benefits to community members.

- Openly positioning ourselves in our dissemination plans can be an important way for qualitative researchers to be transparent and account for our role.

21.3 Informing your dissemination plan

- Appraise important dimensions of planning that will inform their research dissemination plan, including: audience, purpose, context and content

- Apply this appraisal to key decisions they will need to make when designing their qualitative research product(s)

This section will offer you a general overview of points to consider as you form the dissemination plan for your research. We will start with considerations regarding your audience, then turn our attention to the purpose of your research, and finally consider the importance of attending to both content and context as you plan for your final research product(s).

Perhaps the most important consideration you have as you plan how to present your work is your audience. Research is a product that is meant to be consumed, and because of this, we need to be conscious of our consumers. We will speak more extensively about knowing your audience in Chapter 24 , devoted to both sharing and consuming research. Regardless of who your audience is (e.g. community members, classmates, research colleagues, practicing social workers, state legislator), there will be common elements that will be important to convey. While the way you present them will vary greatly according to who is listening, Table 21.1 offers a brief review of the elements that you will want your audience to leave with.

Once we determine who our audience is, we can further tailor our dissemination plan to that specific group. Of course, we may be presenting our findings in more than one venue, and in that case, we will have multiple plans that will meet the needs of each specific audience.

It’s a good idea to pitch your plan first. However you plan to present your findings, you will want to have someone preview before you share with a wider audience. Ideally, whoever previews will be a person from your target audience or at least someone who knows them well. Getting feedback can go a long way in helping us with the clarity with which we convey our ideas and the impact they have on our audience. This might involve giving a practice speech, having someone review your article or report, or practice discussing your research one-on-one, as you would with a poster presentation. Let’s talk about some specific audiences that you may be targeting and their unique needs or expectations.

Below I will go through some brief considerations for each of these different audiences. I have tried to focus this discussion on elements that are relevant specific to qualitative studies since we do revisit this topic in Chapter 24 .

Research community

When presenting your findings to an academic audience or other research-related community, it is probably safe to a make a few assumptions. This audience is likely to have a general understanding of the research process and what it entails. For this reason, you will have to do less explaining of research-related terms and concepts. However, compared to other audiences, you will probably have to provide a bit more detail about what steps you took in your research process, especially as they relate to qualitative rigor, because this group will want to know about how your research was carried out and how you arrived at your decisions throughout the research process. Additionally, you will want to make a clear connection between which qualitative design you chose and your research question; a methodological justification . Researchers will also want to have a good idea about how your study fits within the wider body of scientific knowledge that it is related to and what future studies you feel are needed based on your findings. You are likely to encounter this audience if you are disseminating through a peer-reviewed journal article, presenting at a research conference, or giving an invited talk in an academic setting.

Professional community

We often find ourselves presenting our research to other professionals, such as social workers in the field. While this group may have some working knowledge of research, they are likely to be much more focused on how your research is related to the work they do and the clients they serve. While you will need to convey your design accurately, this audience is most likely to be invested in what you learned and what it means (especially for practice). You will want to set the stage for the discussion by doing a good job expressing your connection to and passion for the topic (a positionality statemen t might be particularly helpful here), what we know about the issue, and why it is important to their professional lives. You will want to give good contextual information for your qualitative findings so that practitioners can know if these findings might apply to people they work with. Also, as since social work practitioners generally place emphasis on person-centered practice, hearing the direct words of participants (quotes) whenever possible, is likely to be impactful as we present qualitative results. Where academics and researchers will want to know about implications for future research, professionals will want to know about implications for how this information could help transform services in the future or understand the clients they serve.

Lay community

The lay community are people who don’t necessarily have specialized training or knowledge of the subject, but may be interested or invested for some other reason; perhaps the issue you are studying affects them or a loved one. Since this is the general public, you should expect to spend the most time explaining scientific knowledge and research processes and terminology in accessible terms. Furthermore, you will want to invest some time establishing a personal connection to the topic (like I talked about for the professional community). They will likely want to know why you are interested and why you are a credible source for this information. While this group may not be experts on research, as potential members of the group(s) that you may be researching, you do want to remember that they are experts in their own community. As such, you will want to be especially mindful of approaching how you present findings with a sense of cultural humility (although hopefully you have this in mind across all audiences). It will be good to discuss what steps you took to ensure that your findings accurately reflect what participants shared with you ( rigor ). You will want to be most clear with this group about what they should take away, without overstating your findings.

Regardless of who your audience is, remember that you are an ambassador. You may represent a topic, a population, an organization, or the whole institution of research, or any combination of these. Make sure to present your findings honestly, ethically, and clearly. Furthermore, I’m assuming that the research you are conducting is important because you have spent a lot of time and energy to arrive at your findings. Make sure that this importance comes through in your dissemination. Tell a compelling story with your research!

Who needs to hear the message of your qualitative research?

- Example. If you are presenting your research about caregiver fatigue to a caregiver support group, you won’t need to spend time describing the role of caregivers because your audience will have lived experience.

- Example. If you are presenting your research findings to a group of academics, you wouldn’t have to explain what a sampling frame is, but if you are sharing it with a group of community members from a local housing coalition, you will need to help them understand what this is (or maybe use a phrase that is more meaningful to them).

- Example. If you are speaking to a group of child welfare workers about your study examining trauma-informed communication strategies, they are probably going to want to know how these strategies might impact the work that they do.

- Example. If you are sharing your findings at a meeting with a council member, it may be especially meaningful to share direct quotes from constituents.

Being clear about the purpose of your research from the outset is immeasurably helpful. What are you hoping to accomplish with your study? We can certainly look to the overarching purpose of qualitative research, that being to develop/expand/challenge/explore understanding of some topic. But, what are you specifically attempting to accomplish with your study? Two of the main reasons we conduct research are to raise awareness about a topic and to create change around some issue. Let’s say you are conducting a study to better understand the experience of recidivism in the criminal justice system. This is an example of a study whose main purpose is to better understand and raise awareness around a particular social phenomenon (recidivism). On the other hand, you could also conduct a study that examines the use of strengths-based strategies by probation officers to reduce recidivism. This would fall into the category of research promoting a specific change (the use of strengths-based strategies among probation officers). I would wager that your research topic falls into one of these two very broad categories. If this is the case, how would you answer the corresponding questions below?

Are you seeking to raise awareness of a particular issue with your research? If so,

- Whose awareness needs raising?

- What will “speak” most effectively to this group?

- How can you frame your research so that it has the most impact?

Are you seeking to create a specific change with your research? If so,

- What will that change look like?

- How can your research best support that change occurring?

- Who has the power to create that change and what will be most compelling in reaching them?

How you answer these questions will help to inform your dissemination plan. For instance, your dissemination plan will likely look very different if you are trying to persuade a group of legislators to pass a bill versus trying to share a new model or theory with academic colleagues. Considering your purposes will help you to convey the message of your research most effectively and efficiently. We invest a lot of ourselves in our research, so make sure to keep your sights focused on what you hope to accomplish with it!

Content and context

As a reminder, qualitative research often has a dual responsibility for conveying both content and context. You can think of content as the actual data that is shared with us or that we obtain, while context is the circumstances under which that data sharing occurs. Content conveys the message and context provides us the clues with which we can decode and make sense of that message.

While quantitative research may provide some contextual information, especially in regards to describing its sample, it rarely receives as much attention or detail as it does in qualitative studies. Because of this, you will want to plan for how you will attend to both the content and context of your study in planning for your dissemination.

- Research is an intentional act; you are trying to accomplish something with it. To be successful, you need to approach dissemination planfully.

- Planning the most effective way of sharing our qualitative findings requires looking beyond what is convenient or even conventional, and requires us to consider a number of factors, including our audience, the purpose or intent of our research and the nature of both the content and the context that we are trying to convey.

21.4 Final product taking shape

- Evaluate the various means of disseminating research and consider their applicability for your research project

- Determine appropriate building blocks for designing your qualitative research product

As we have discussed, qualitative research takes many forms. It should then come as no surprise that qualitative research products also come in many different packages. To help guide you as the final products of your research take shape, we will discuss some of the building blocks or elements that you are likely to include as tools in sharing your qualitative findings. These are the elements that will allow you to flesh out the details of your dissemination plan.

Building blocks

There are many building blocks that are at our disposal as we formulate our qualitative research product(s). Quantitative researchers have charts, graphs, tables, and narrative descriptions of numerical output. These tools allow the quantitative researcher to tell the story of their research with numbers. As qualitative researchers, we are tasked with telling the story of our research findings as well, but our tools look different. While this isn’t an exhaustive list of tools that are at our disposal as qualitative researchers, a number of commonly used elements in sharing qualitative findings are discussed here. Depending on your study design and the type of data you are working with, you may use one or some combination of the building blocks discussed below.

Themes are a very common element when presenting qualitative research findings. They may be called themes, but they may also go by other names: categories, dimensions, main ideas, etc. Themes offer the qualitative researcher a way to share ideas that emerged from your analysis that were shared by multiple participants or across multiple sources of data. They help us to distill the large amounts of qualitative data that we might be working with into more concise and manageable pieces of information that are more consumable for our audience. When integrating themes into your qualitative research product, you will want to offer your audience: the title of the theme (try to make this as specific/meaningful as possible), a brief description or definition of the theme, any accompanying dimensions or sub-themes that may be relevant, and examples (when appropriate).

Quotes offer you the opportunity to share participants’ exact words with your audience. Of course, we can’t only rely on quotes, because we need to knit the information that is shared into one cohesive description of our findings and an endless list of quotes is unlikely to support this. Because of this, you will want to be judicious in selecting your quotes. Choose quotes that can stand on their own, best reflect the sentiment that is being captured by the theme or category of findings that you are discussing, and are likely to speak to and be understood by your audience. Quotes are a great way to help your findings come alive or to give them greater depth and significance. If you are using quotes, be sure to do so in a balanced manner – don’t only use them in some sections but not others, or use a large number to support one theme and only one or two for another. Finally, we often provide some brief demographic information in a parenthetical reference following a quote so our reader knows a little bit about the person who shared the information. This helps to provide some context for the quote.

Kohli and Pizarro (2016) [2] provide a good example of a qualitative study using quotes to exemplify their themes. In their study, they gathered data through short-answer questionnaires and in-depth interviews from racial-justice oriented teachers of Color. Their study explored the experiences and motivations of these teachers and the environments in which they worked. As you might guess, the words of the teacher-participants were especially powerful and the quotes provided in the results section were very informative and important in helping to fulfill the aim of the research study. Take a few minutes to review this article. Note how the authors provide a good amount of detail as to what each of the themes meant and how they used the quotes to demonstrate and support each theme. The quotes help bring the themes to life and anchor the results in the actual words of the participants (suggesting greater trustworthiness in the findings).

Figure 21.1 below offers a more extensive example of a theme being reported along with supporting quotes from a study conducted by Karabanow, Gurman, and Naylor (2012) [3] . This study focused on the role of work activities in the lives of “Guatemalan street youth”. One of the important themes had to do with intersection of work and identity for this group. In this example, brief quotes are used within the body of the description of the theme, and also longer quotes (full sentence(s)) to demonstrate important aspects of the description.

Pictures or videos

If our data collection involves the use of photographs, drawings, videos or other artistic expression of participants or collection of artifacts, we may very well include selections of these in our dissemination of qualitative findings. In fact, if we failed to include these, it would seem a bit inauthentic. For the same reason we include quotes as direct representations of participants’ contributions, it is a good idea to provide direct reference to other visual forms of data that support or demonstrate our findings. We might incorporate narrative descriptions of these elements or quotes from participants that help to interpret their meaning. Integrating pictures and quotes is especially common if we are conducting a study using a Photovoice approach, as we discussed in Chapter 17 , where a main goal of the research technique is to bring together participant generated visuals with collaborative interpretation.

Take some time to explore the website linked here. It is the webpage for The Philidelphia Collaborative for Health Equity’s PhotoVoice Exhibit Gallery and offers a good demonstration of research that brings together pictures and text.

Graphic or figure

Qualitative researchers will often create a graphic or figure to visually reflect how the various pieces of your findings come together or relate to each other. Using a visual representation can be especially compelling for people who are visual learners. When you are using a visual representation, you will want to: label all elements clearly; include all the components or themes that are part of your findings; pay close attention to where you place and how you orient each element (as their spatial arrangement carries meaning); and finally, offer a brief but informative explanation that helps your reader to interpret your representation. A special subcategory of visual representation is process. These are especially helpful to lay out a sequential relationship within your findings or a model that has emerged out of your analysis. A process or model will show the ‘flow’ of ideas or knowledge in our findings, the logic of how one concept proceeds to the next and what each step of the model entails.

Noonan and colleagues (2004) [4] conducted a qualitative study that examined the career development of high achieving women with physical and sensory disabilities. Through the analysis of their interviews, they built a model of career development based on these women’s experiences with a figure that helps to conceptually illustrate the model. They place the ‘dyanmic self’ in the center, surrounded by a dotted (permeable) line, with a number of influences outside the line (i.e. family influences, disability impact, career attitudes and behaviors, sociopoltical context, developmental opportunities and social support) and arrows directed inward and outward between each influence and the dynamic self to demonstrate mutual influence/exchange between them. The image is included in the results section of their study and brings together “core categories” and demonstrates how they work together in the emergent theory or how they relate to each other. Because so many of our findings are dynamic, like Noonan and colleagues, showing interaction and exchange between ideas, figures can be especially helpful in conveying this as we share our results.

Going one step further than the graphic or figure discussed above, qualitative researchers may decide to combine and synthesize findings into one integrated representation. In the case of the graphic or figure, the individual elements still maintain their distinctiveness, but are brought together to reflect how they are related. In a composite however, rather than just showing that they are related (static), the audience actually gets to ‘see’ the elements interacting (dynamic). The integrated and interactive findings of a composite can take many forms. It might be a written narrative, such as a fictionalized case study that reflects of highlights the many aspects that emerged during analysis. It could be a poem, dance, painting or any other performance or medium. Ultimately, a composite offers an audience a meaningful and comprehensive expression of our findings. If you are choosing to utilize a composite, there is an underlying assumption that is conveyed: you are suggesting that the findings of your study are best understood holistically. By discussing each finding individually, they lose some of their potency or significance, so a composite is required to bring them together. As an example of a composite, consider that you are conducting research with a number of First Nations Peoples in Canada. After consulting with a number of Elders and learning about the importance of oral traditions and the significance of storytelling, you collaboratively determine that the best way to disseminate your findings will be to create and share a story as a means of presenting your research findings. The use of composites also assumes that the ‘truths’ revealed in our data can take many forms. The Transgender Youth Project hosted by the Mandala Center for Change , is an example of legislative theatre combining research, artistic expression, and political advocacy and a good example of action-oriented research.

While you haven’t heard much about numbers in our qualitative chapters, I’m going to break with tradition and speak briefly about them here. For many qualitative projects we do include some numeric information in our final product(s), mostly in the way of counts. Counts usually show up in the way of frequency of demographic characteristics of our sample or characteristics regarding our artifacts, if they aren’t people. These may be included as a table or they may be integrated into the narrative we provide, but in either case, our goal in including this information is to offer the reader information so they can better understand who or what our sample is representing. The other time we sometimes include count information is in respect to the frequency and coverage of the themes or categories that are represented in our data. Frequency information about a theme can help the reader to know how often an idea came up in our analysis, while coverage can help them to know how widely dispersed this idea was (e.g. did nearly everyone mention this, or was it a small group of participants).

- There are a wide variety of means by which you can deliver your qualitative research to the public. Choose one that takes into account the various considerations that we have discussed above and also honors the ethical commitments that we outlined early in this chapter.

- Presenting qualitative research requires some amount of creativity. Utilize the building blocks discussed in this chapter to help you consider how to most authentically and effectively convey your message to a wider audience.

What means of delivery will you be choosing for your dissemination plan?

What building blocks will best convey your qualitaitve results to your audience?

- National Association of Social Workers. (2017). NASW code of ethics. Retrieved from https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English ↵

- Kohli, R., & Pizarro, M. (2016). Fighting to educate our own: Teachers of Color, relational accountability, and the struggle for racial justice. Equity & Excellence in Education, 49 (1), 72-84. ↵

- Karabanow, J., Gurman, E., & Naylor, T. (2012). Street youth labor as an Expression of survival and self-worth. Critical Social Work, 13 (2). ↵

- Noonan, B. M., Gallor, S. M., Hensler-McGinnis, N. F., Fassinger, R. E., Wang, S., & Goodman, J. (2004). Challenge and success: A Qualitative study of the career development of highly achieving women with physical and sensory disabilities. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51 (1), 68. ↵

- Ede, L., & Starrin, B. (2014). Unresolved conflicts and shaming processes: risk factors for long-term sick leave for mental-health reasons. Nordic Journal of Social Research, 5 , 39-54. ↵

how you plan to share your research findings

One of the three values indicated in the Belmont report. An obligation to protect people from harm by maximizing benefits and minimizing risks.

A written agreement between parties that want to participate in a collaborative project.

A research journal that helps the researcher to reflect on and consider their thoughts and reactions to the research process and how it may be shaping the study

Context is the circumstances surrounding an artifact, event, or experience.

Rigor is the process through which we demonstrate, to the best of our ability, that our research is empirically sound and reflects a scientific approach to knowledge building.

Content is the substance of the artifact (e.g. the words, picture, scene). It is what can actually be observed.

Graduate research methods in social work Copyright © 2020 by Matthew DeCarlo, Cory Cummings, Kate Agnelli is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 15 October 2020

Strategies for effective dissemination of research to United States policymakers: a systematic review

- Laura Ellen Ashcraft ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9957-0617 1 ,

- Deirdre A. Quinn 2 &

- Ross C. Brownson 3 , 4

Implementation Science volume 15 , Article number: 89 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

40k Accesses

52 Citations

41 Altmetric

Metrics details

Research has the potential to influence US social policy; however, existing research in this area lacks a coherent message. The Model for Dissemination of Research provides a framework through which to synthesize lessons learned from research to date on the process of translating research to US policymakers.

The peer-reviewed and grey literature was systematically reviewed to understand common strategies for disseminating social policy research to policymakers in the United States. We searched Academic Search Premier, PolicyFile, SocINDEX, Social Work Abstracts, and Web of Science from January 1980 through December 2019. Articles were independently reviewed and thematically analyzed by two investigators and organized using the Model for Dissemination of Research.

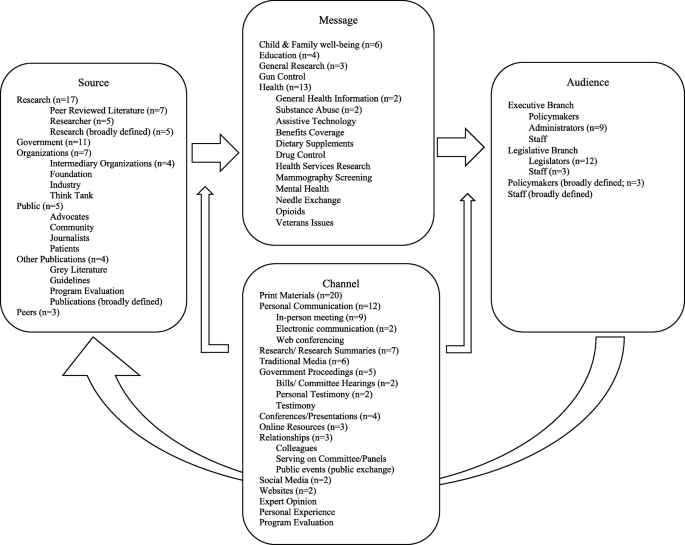

The search resulted in 5225 titles and abstracts for inclusion consideration. 303 full-text articles were reviewed with 27 meeting inclusion criteria. Common sources of research dissemination included government, academic researchers, the peer reviewed literature, and independent organizations. The most frequently disseminated research topics were health-related, and legislators and executive branch administrators were the most common target audience. Print materials and personal communication were the most common channels for disseminating research to policymakers. There was variation in dissemination channels by level of government (e.g., a more formal legislative process at the federal level compared with other levesl). Findings from this work suggest that dissemination is most effective when it starts early, galvanizes support, uses champions and brokers, considers contextual factors, is timely, relevant, and accessible, and knows the players and process.

Conclusions

Effective dissemination of research to US policymakers exists; yet, rigorous quantitative evaluation is rare. A number of cross-cutting strategies appear to enhance the translation of research evidence into policy.

Registration

Not registered.

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the literature

This is one of the first systematic reviews to synthesize how social policy research evidence is disseminated to US policymakers.

Print materials and personal communications were the most commonly used channels to disseminate social policy research to policymakers.

Several cross-cutting strategies (e.g., start early, use evidence “champions,” make research products more timely, relevant, and accessible) were identified that are likely to lead to more effective translate of research evidence into the policy making process in the United States.

In recent years, social scientists have sought to understand how research may influence policy [ 1 , 2 ]. Interest in this area of investigation has grown with the increased availability of funding for policy-specific research (e.g., dissemination and implementation research) [ 3 ]. However, because of variation in the content of public policy, this emerging area of scholarship lacks a coherent message that specifically addresses social policy in the United States (US). While other studies have examined the use of evidence in policymaking globally [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ], the current review focuses on US social policy; for the purposes of this study, social policy includes policies which focus on antipoverty, economic security, health, education, and social services [ 8 , 9 , 10 ].

Significant international research exists on barriers and facilitators to the dissemination and use of research evidence by policymakers [ 4 , 5 ]. Common themes include the importance of personal relationships, the timeliness of evidence, and resource availability [ 4 , 5 ]. Previous work demonstrates the importance of understanding policymakers’ perceptions and how evidence is disseminated. The current review builds on this existing knowledge to examine how research evidence reaches policymakers and to understand what strategies are likely to be effective in overcoming identified barriers.

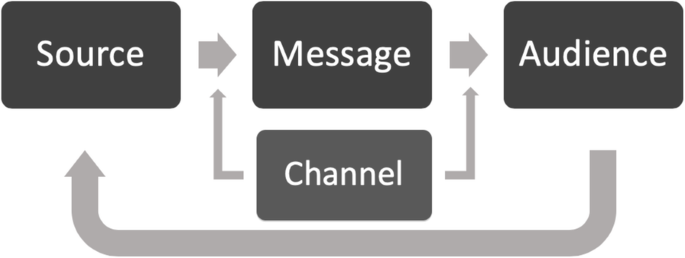

Theoretical frameworks offer a necessary foundation to identify and assess strategies for disseminating research to policymakers. The Model for Dissemination of Research integrates Diffusion of Innovations Theory and Social Marketing Theory with the Mathematical Theory of Communication [ 11 , 12 ] and the Matrix of Persuasive Communication [ 13 , 14 ] to address the translation gap between research and policy. The purpose of the Model for Dissemination of Research is to highlight the gaps between research and targets audiences (e.g., policymakers) and improve dissemination through the use of a theoretical foundation and review of the literature [ 15 ]. Diffusion of Innovations Theory describes the spread and adoption of novel interventions through an “s-curve,” ordered process, and characteristics of the message and audience [ 16 ]. Additional theoretical contributions for dissemination research come from Social Marketing Theory, which postulates commercial marketing strategies summarized by the four P’s (produce, price, place, and promotion) and the understanding that communication of the message alone will not change behavior [ 17 ].

The Model for Dissemination of Research includes the four key components described by Shannon and Weaver [ 11 , 12 ] and later McGuire [ 13 , 14 ] of the research translation process: the source, message, audience, and channel (Fig. 1 ). The source includes researchers who generate evidence. The message includes relevant information sent by the source on a policy topic. The audience includes those receiving the message via the channel [ 15 ]. The channel is how the message gets from the source to the audience [ 15 ].

The Model for Dissemination of Research. The Model for Dissemination of Research integrates Diffusion of Innovations Theory, the Mathematical Theory of Communication, and Social Marketing Theory to develop a framework for conceptualizing how information moves from source to audience. Originally published by Brownson et al. in Journal of public health management and practice in 2018

While the Model for Dissemination of Research and its origins (i.e., the Mathematical Theory of Communication and Diffusion of Innovations Theory) appear linear in their presentation, Shannon and Weaver [ 11 , 12 ] and Rogers [ 16 ] clearly acknowledge that the dissemination of information is not a linear process and is effected by the environment within which it occurs. This approach aligns with the system model or knowledge to action approach proposed by Best and Holmes [ 18 ]. The systems model accounts for influence of the environment on a process and accounts for the complexity of the system [ 18 ]. Therefore, while some theoretical depictions appear linear in their presentation; it is important to acknowledge the critical role of systems thinking.

To date, lessons learned from dissemination and implementation science about the ways in which research influences policy are scattered across diverse disciplines and bodies of literature. These disparate lessons highlight the critical need to integrate knowledge across disciplines. The current study aims to make sense of and distill these lessons by conducting a systematic review of scientific literature on the role of research in shaping social policy in the United States. The results of this systematic review are synthesized in a preliminary conceptual model (organized around the Model for Dissemination of Research) with the goal of improving dissemination strategies for the translation of scientific research to policymakers and guiding future research in this area.

This systematic review aims to synthesize existing evidence about how research has been used to influence social policy and is guided by the following research questions:

What are common strategies for using research to influence social policy in the United States?

What is the effectiveness of these strategies?

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-P) model [ 19 , 20 ] to examine and distill existing studies on strategies for using research evidence to influence social policy.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for this review if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) occurred in the United States; (2) reported in English; (3) systematically evaluated the impact of research on social policy (this typically excluded studies focusing on policymaker dissemination preferences); (4) discussed domestic social policy (as defined above); and (5) were published in the peer reviewed literature or the grey literature (e.g., think tank research briefs, foundation research publications).

We chose to focus our review on the United States to capture the strengths and challenges of its unique, multi-level policy and political environment. The de-centralized structure of government in the United States allows significant decision-making authority at the state and local levels, with wide variation in capacity and the availability of resources across the country [ 21 ]. For example, some states have full-time legislatures while other states have part-time legislatures. In total, these factors create a fitting and complex environment to examine the dissemination of research to policymakers. The influence of lobbying in the United States also differs from other western countries. In the United States, there is more likely to be a “winner-take-all” process where some advocates (often corporations and trade associations) have disproportionate influence [ 22 ]. In addition, the role of evidence differs in the US compared with other countries, where the US tends to take a narrower focus on intervention impact with less emphasis on system-level issues (e.g., implementation, cost) [ 23 ].

Studies were excluded if they were not in English or occurred outside of the United States. We also excluded non-research sources, such as editorials, opinion pieces, and narrative stories that contain descriptions of dissemination strategies without systematic evaluation. Further, studies were excluded if the results focused on practitioners (e.g., case managers, local health department workers) and/or if results for practitioners could not be parsed from results for policymakers.

To identify studies that systematically evaluated the impact of research on social policy, we reviewed the research questions and results of each study to determine whether or not they examined how research evidence reaches policymakers (as opposed to policymaker preferences for disseminated research). For example, we would not include a research study that only describes different types of policy briefs, without also evaluating how the briefs are used by policymakers to inform policy decisions. We used the Model for Dissemination of Research, as defined above, to see if and how the studies describe and test the channels of dissemination. We built on the Model of Dissemination by also considering passive forms of knowledge, such as peer-reviewed literature or research briefs, as potential sources of knowledge and not just as channels in and of themselves.

Information sources

We took a three-pronged approach to develop a comprehensive understanding of existing knowledge in this area. First, we searched the peer reviewed literature using the following databases: Academic Search Premier, PolicyFile, SocINDEX, Social Work Abstracts, and Web of Science. We expanded the inquiry for evidence by searching the grey literature through PolicyFile, and included recommendations from experts in the field of dissemination of research evidence to policymakers resulting in 137 recommended publications.

Search strategy

Our search strategy included the following terms: [research OR study OR studies OR knowledge] AND [policy OR policies OR law OR laws OR legislation] AND [use OR utilization OR utilisation] OR [disseminate OR dissemination OR disseminating] OR [implementation OR implementing OR implement] OR [translate OR translation OR translating]. Our search was limited to studies in the United States between 1980 and 2019. We selected this timeframe based on historical context: the 1950s through the 1970s saw the development of the modern welfare state, which was (relatively) complete by 1980. However, shifting political agendas in the 1980s saw the demand for evidence increase to provide support for social programs [ 24 ]; we hoped to capture this increase in evidence use in policy.

Selection process

All titles and abstracts were screened by the principal investigator (LEA) with 20% reviewed at random by a co-investigator (DAQ) with total agreement post-training. Studies remaining after abstract screening moved to full text review. The full text of each study was considered for inclusion (LEA and DAQ) with conflicts resolved by consensus. The data abstraction form was developed by the principal investigator (LEA) based on previous research [ 25 , 26 ] and with feedback from co-authors. Data were independently abstracted from each reference in duplicate with conflicts resolved by consensus (LEA and DAQ). We completed reliability checks on 20% of the final studies, selected at random, to ensure accurate data abstraction.

Data synthesis

Abstracted data was qualitatively analyzed using thematic analysis (LEA and DAQ) and guided by the Model for Dissemination of Research. The goal of the preliminary conceptual model was to synthesize components of dissemination for studies that evaluate the dissemination of social policy to policymakers.

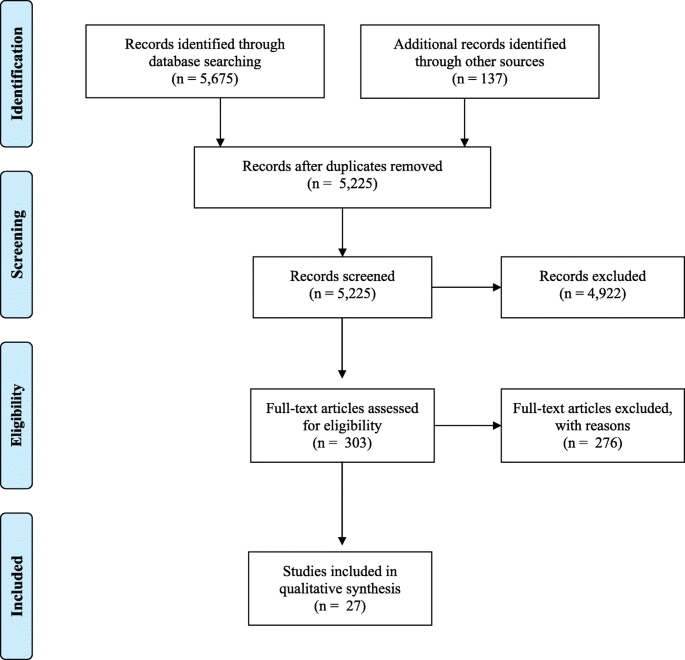

Descriptive results

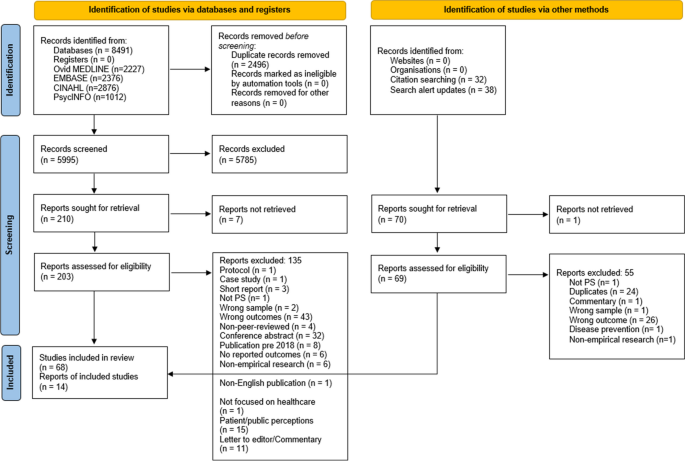

The search of the literature resulted in 5675 articles and 137 articles recommended by content experts for review with 5225 titles and abstracts screened after duplicates removed. Of those articles, 4922 were excluded due to not meeting inclusion criteria. Further, 303 full text articles were reviewed with 276 excluded as they did not meet inclusion criteria. Twenty-seven articles met inclusion criteria (see the Fig. 2 for the PRISMA flow diagram).

PRISMA flowchart. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram reports included and excluded articles in the systematic review

Included studies are listed in Table 1 . The 27 included 6 studies using quantitative methods, 18 that employed qualitative methods, and 3 that used a mixed methods approach. The qualitative studies mostly employed interviews ( n = 10), while others used case studies ( n = 6) or focus groups ( n = 3). Most studies examined state-level policy ( n = 18) and nine studies examined federal-level policy, with some studies looking at multiple levels of government. Included studies focused on the executive and legislative branches with no studies examining the judicial branch.

We examined dissemination based on geographic regions and/or political boundaries (i.e., regions or states). Sixteen of the 27 studies (about 59%) used national samples or multiple states and did not provide geographic-specific results [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Two studies (about 7%) did not specific the geographic region or state in which the study took place [ 43 , 44 ]. Of the remaining studies, four examined policymaking in the Northeastern United States [ 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ], four in the Western US [ 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 ], and one in the South [ 53 ]. The geographic regional groups used similar channels to disseminate evidence to policymakers including publications and presentations.

We also analyzed whether dissemination at different levels of government (i.e., local, state, and federal) used unique channels. Six of included studies (about 22%) examined multiple levels of government and did not separate results based on specific levels of government [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 53 ]. One study did not specifically identify the level of government used [ 46 ]. While there is considerable overlap in dissemination channels used at each level of government, there are some unique characteristics.

Five studies (about 18.5%) examined dissemination at the federal level [ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ]. At the federal level, dissemination channels tended to be more formal such as congressional committee hearings [ 36 ] and legislative development [ 35 ]. Twelve studies (about 44%) evaluated dissemination at the state level [ 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 47 , 48 , 50 , 51 , 52 ]. State level dissemination heavily relied on printed materials including from mental health care disparity report cards [ 41 ], policy briefs [ 38 ], and effectiveness reports [ 50 ]. Another common channel was in-person communications such as one-on-one meetings [ 44 ] and presentations to stakeholders [ 51 ]. Three studies (about 11%) focused on local-level government. Dissemination channels at the local level had little consistency across the three studies with channels including public education [ 45 ], reports [ 37 ], and print materials [ 49 ].