Home — Essay Samples — Religion — Religious Pluralism — Role of Religion in Society: Exploring its Significance and Implications

Role of Religion in Society: Exploring Its Significance and Implications

- Categories: Religious Beliefs Religious Pluralism

About this sample

Words: 1028 |

Published: Sep 5, 2023

Words: 1028 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, the significance of religion in society, the implications of religion in society, the debate surrounding the role of religion in society, the historical context of religion in society, the impact of religion on culture and identity, the role of religion in promoting social cohesion, the impact of religion on politics and governance, the relationship between religion and morality, the role of religion in promoting social justice and equality, the debate between secularism and religious influence in society, the impact of cultural attitudes towards religion on the debate, the potential consequences of religion's role in society.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Religion

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 903 words

4 pages / 1709 words

1 pages / 574 words

2 pages / 882 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Religious Pluralism

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a unique place in the landscape of religious pluralism. As a distinct Christian denomination with its own theological beliefs, practices, and history, the LDS Church has [...]

Globalization, the process of increased interconnectedness and interdependence among nations and cultures, has had a profound impact on virtually every aspect of human life. Religion, as a fundamental element of culture and [...]

Through life as we hear about different world religions and what they believe or hold to be true, it becomes easy to begin to build presuppositions about these religions. It can also be found that some or most of these [...]

In the 21st-century ethics as far as religious doctrines are concerned has taken a modernity turn. In the classical period religion was solely relied on to dictate morality but due to contemporariness catalyzed by education [...]

In Zhao Xiao’s book “Churches and the market economy,” it is indicated that, American churches are the core that binds Americans together.The Europeans don't feel contented with the naive visualization of religious USA by [...]

The principle of separation of church and state is a cornerstone of democratic societies, reflecting the delicate balance between religious freedom and government authority. This essay delves into the concept of separation of [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Hidden Brain

Where does religion come from one researcher points to 'cultural' evolution.

Shankar Vedantam

Laura Kwerel

Lucy Perkins

Jennifer Schmidt

Rhaina Cohen

Creating God

Muslim women praying together in Istiqlal mosque, Jakarta, Indonesia. Afriadi Hikmal/Getty Images hide caption

Muslim women praying together in Istiqlal mosque, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Let's take a moment to go back in time.

For most of human history, we lived in small groups of about 50 people. Everyone knew everybody. If you told a lie, stole someone's dinner, or failed to defend the group against its enemies, there was no way to disappear into the crowd. Everyone knew you, and you would get punished.

But in the last 12,000 years or so, human groups began to expand. It became more difficult to identify and punish the cheaters and free riders. So we needed something big — really big. An epic force that could see what everyone was doing, and enforce the rules. That force, according to social psychologist Azim Shariff , was the popular idea of a "supernatural punisher" – also known as God.

Think of the vengeful deity of the Hebrew Bible, known for sending punishments like rains of burning sulfur and clouds of locusts, blood and lice.

"It's an effective stick to deter people from immoral behavior," says Shariff.

For Shariff and other researchers who study religion through the lens of evolution, religion can be seen as a cultural innovation, similar to fire, tools or agriculture. He says the vibrant panoply of religious rituals and beliefs we see today – including the popular belief in a punishing God – emerged in different societies at different times as mechanisms to help us survive as a species.

This week on Hidden Brain , we explore a provocative idea about the origin, and purpose, of the world's religions.

Additional Resources:

Mean Gods make good people: Read Azim Shariff's 2011 study on how the fear of "supernatural punishment" is reliably associated with lower levels of cheating.

Is the call to prayer a call to cooperate? Read this 2015 study by Eric Duhaime, who found that when Moroccan shopkeepers heard the call to prayer , they were more likely to give more money to charity.

Read Scott Atran's 2003 article on the very old practice of suicide attacks in the name of faith , and how to prevent them.

A tour through sacred sound: listen to audio portraits of the call to prayer and the "om" featured in our episode. They come from the Soundscapes of Faith series by Interfaith Voices.

Hidden Brain is hosted by Shankar Vedantam and produced by Rhaina Cohen, Parth Shah, Jennifer Schmidt, Thomas Lu, and Laura Kwerel. Our supervising producer is Tara Boyle. You can also follow us on Twitter @hiddenbrain.

- philosophy of religion

- Azim Shariff

- cultural evolution

Speaking Truth to Israel Requires More Than Academic Freedom

Payangko, or Echidna ( Zaglossus attenboroughi )

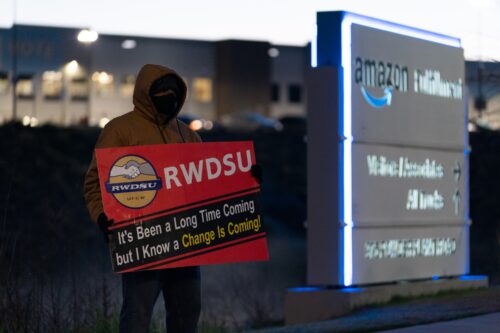

Inside Amazon’s Union-Busting Tactics

Fighting for Reproductive Rights in Retirement

Can Ancient DNA Support Indigenous Histories?

Can Embracing Copies Help With Museum Restitution Cases?

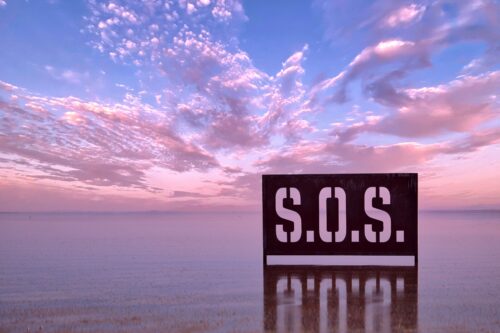

Can Art Save the “Post-Apocalyptic” Salton Sea?

How Allocating Work Aided Our Evolutionary Success

Bringing Back the World’s Most Endangered Cat

The Shortcomings of Height in Politics

Griko’s Poetic Whisper

When a Message App Became Evidence of Terrorism

The Rise of Aunties in Pakistani Politics

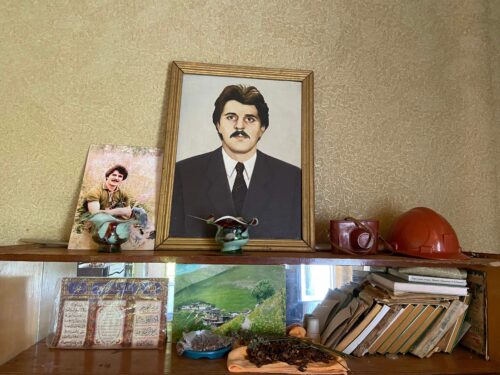

For Families of Missing Loved Ones, Forensic Investigations Don’t Always Bring Closure

Albania’s Waste Collectors and the Fight for Dignity

Grappling With Guilt Inside a System of Structural Violence

Inside Russia’s Campaign to Steal and Indoctrinate Ukrainian Children

Coastal Eden

On the Tracks to Translating Indigenous Knowledge

A Call for Anthropological Poems of Resistance, Refusal, and Wayfinding

Buried in the Shadows, Ireland’s Unconsecrated Dead

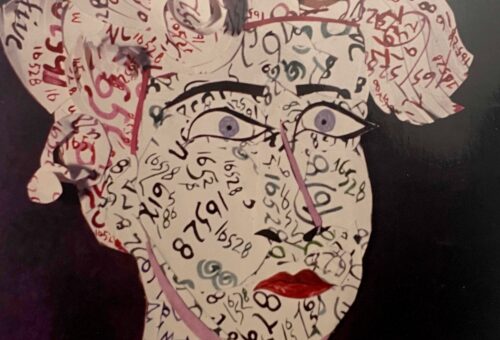

Nameless Woman

A Palestinian Family’s History—Told Through Olive Trees

Can “Made in China” Become a Beacon of Sustainability?

The International Order Is Failing to Protect Palestinian Cultural Heritage

Spotlighting Black Women’s Mental Health Struggles

Being a “Good Man” in a Time of Climate Catastrophe

Cultivating Modern Farms Using Ancient Lessons

Imphal as a Pond

A Freediver Finds Belonging Without Breath

The Trauma Mantras

How Did Belief Evolve?

About 20 years ago, the residents of Padangtegal village in Bali, Indonesia, had a problem. The famous, monkey-filled forest surrounding the local Hindu temple complex had become stunted, and saplings failed to sprout and thrive. Since I was conducting fieldwork in the area, the head of the village council, Pak Acin, asked me and my team to investigate.

We discovered that locals and tourists visiting the temples had previously brought food wrapped in banana leaves, then tossed the used leaves on the ground. But when plastic-wrapped meals became popular, visitors threw the plastic onto the forest floor, where it choked the young trees.

I told Acin we would clean up the soil and suggested he enact a law prohibiting plastic around the temples. He laughed and told us a ban would be useless. The only thing that would change people’s behavior was belief. What we needed, he said, was a goddess of plastic.

Over the next year, our research team and Balinese collaborators didn’t exactly invent a Hindu deity. But we did harness Balinese beliefs and traditions about harmony between people and environments. We created new narratives about plastic, forests, monkeys, and temples. We developed ritualistic caretaking behaviors that forged new relationships between humans, monkeys, and forests.

As a result, the soils and undergrowth were rejuvenated, the trees grew stronger and taller, and the monkeys thrived. Most importantly, the local community reaped the economic and social benefits of a healthy, vigorous forest and temple complex.

Acin taught me that science and rules cannot ensure lasting change without belief—the most creative and destructive ability humans have ever evolved.

Most people assume “belief” refers to religion. But it is so much more. Belief is the ability to combine histories and experiences with imagination, to think beyond the here and now. It enables humans to see, feel, and know an idea that is not immediately present to the senses, then wholly invest in making that idea one’s reality.

We must believe in ideas and abilities in order to invent iPhones, construct rockets, and make movies. We must believe in the value of goods, currencies, and knowledge to build economies. We must believe in collective ideals, constitutions, and institutions to form nations. We must believe in love (something no one can clearly see, define, or understand) to engage in relationships.

In my recent book, Why We Believe , I explore how we evolved this universally and uniquely human capacity, drawing on my 26 years of research into human and other primates’ evolution, biology, and daily lives. [1] [1] Portions of this essay come from the author’s book Why We Believe (Yale University Press, 2019). Our 2-million-year journey to complex religions, political philosophies, and technologies essentially follows a three-step path: from imagination to meaning-making to belief systems. To trace that path, we must go back to where it started: rocks.

A little over 2 million years ago , our genus ( Homo ) emerged and pushed the evolutionary envelope. Its hominin ancestors had been doing pretty well as socially dynamic, cognitively complex, stone tool–wielding primates. But Homo ratcheted up reliance on one another to better evade predators, forage and process new foods, communally raise young, and fashion superior stone tools.

One of the skills that helped Homo succeed was imagination—an ability you can use now to picture how it developed.

Imagine an early Homo preparing the evening meal. She knows stones can be hit and flaked to form sharper utensils that cut and chop. She also knows the stone tools her ancestors made don’t do a particularly great job: They take a long time to hack the raw meat off a carcass, to smash and grind the roots the community has dug up, and to crack open bones and scoop out the delicious marrow.

One day she looks at her brethren laboring to create simple, one-sided, flaked stone tools. She sees, in her mind’s eye, flakes being removed from both sides, further sharpening the edges and balancing the shape. She creates a mental representation of a possibility—and she makes it her reality.

She and her descendants experiment with more extensive reshaping of stones—creating, for example, Acheulean hand axes. They begin to predict flaking patterns. They conceive of more diverse instruments for slicing roots and raw meat , and carving bone and wood. They translate private musings and imaginings into communal realities. When they make a discovery, they teach one another, speeding up the invention process and expanding the possibilities of their efforts.

By 500,000 years ago, Homo had mastered the skill of shaping stone, bone, hides, horns, and wood into dozens of tool types. Some of these tools were so symmetrical and aesthetically pleasing that some scientists speculate toolmaking took on a ritual aspect that connected Homo artisans with their traditions and community. These ritualistic behaviors may have evolved, hundreds of thousands of years later, into the rituals we see in religions.

With their new gadgets, Homo chopped wood, dug deeper for tubers, collected new fruits and leaves, and put a wider variety of animals on the menu. These activities—expanding their diets, constructing new ecologies, and altering the implements in their environment—literally reshaped their bodies and minds.

In response to these diverse experiences, Homo grew increasingly dynamic neural pathways that allowed them to become even more responsive to their environment. During this time period, Homo ’s brains reached their modern size .

But their brains didn’t uniformly enlarge. Parts of the frontal lobes—which play critical roles in emotional, social, motivational, and perceptual processes, as well as decision-making, attention, and working memory—expanded and elaborated at an increased rate .

Another brain organ that ballooned was the cerebellum. Over the course of hominin history, our lineage added approximately 16 billion more cerebellar neurons than would be expected for our brain size. This ancient brain organ is involved with social sensory-motor skills, imitation, and complex sequences of behavior.

These structural changes helped Homo generate more effective and expansive mental representations. What emerged was a distinctively human imagination—the capacity that allows us to create and shape our futures. It also gave rise to the next step in the evolution of belief: meaning-making.

The rise of imagination sparked positive feedback loops between creativity, social collaboration, teaching, learning, and experimenting. The advent of cooking opened up a new landscape of foods and nutrient profiles. By boiling, barbecuing, grinding, or mashing meat and plants, Homo maximized access to proteins, fats, and minerals.

This gave them the nutrition and energy necessary for extended childhood brain development and increased neural connectivity. It allowed them to travel greater distances. It enabled them to evolve neurobiologies and social capacities that made it possible to move from imagining and making new tools to imagining and making new ways of being human.

By about 200,000 years ago, Homo had begun to push the artistic envelope. Groups of Homo sapiens were coloring their stone tools with ochres—red, yellow, and brown pigments made of iron oxide. They were likely also using ochres to paint their bodies and cave walls.

Ochre decoration requires far more complicated cognitive processes than, for example, an Australasian bowerbird arranging sparkling glass and other baubles around its nest to attract a mate. It requires the kind of complex creative sequences made possible by elaborate frontal lobes, a dense cerebellum, and more diverse and intricate social relationships.

Imagine an early Homo sapiens who wants to paint a stone ax. She and her companions must seek out specific types of rocks and use a tool to scrape off the iron oxides. Then, they might manipulate the minerals’ chemistry, mixing them with water to transform them into pigments or heating them to turn them from yellow to red. Finally, they must apply the paint to the ax, changing how light reflects off its surface—making it look different, making it into a new thing.

When early humans colored something (or someone) red or yellow, it changed the way they perceived that tool, that cave, that person. They were using their imagination to reshape their world to match their desired perceptions of it. They were imbuing objects and bodies with a new, shared meaning.

Gradually, they established relations with more and more distant groups, sharing meanings for the items they swapped and the interactions they exchanged. In short, Homo sapiens began engaging full time in meaning-making.

Collective meaning-making changes the way humans perceive and experience the world. It enables us to do the wildly imaginative, creative, and destructive things we do. It is during this period that Homo broke the boundaries of the material and the visible so the realm of pure imagination could be made tangible.

When a typhoon smashes into land, it tosses trees like matchsticks and fills the air with a deafening roar that drowns out voices. For millennia, every animal caught in such a storm feared it, hunkered down, and waited for it to pass. But at some point, members of the genus Homo began to explain it.

We don’t know when it happened, but within the last few hundred thousand years, humans had developed the imagination, the thirst for meaning, and the communication skills necessary for creating explanations of mysterious phenomena.

By 300,000 to 400,000 years ago, human groups across the planet were sparking fires with sticks and stones, and carefully transporting the flames. And by 80,000 years ago, they were carrying water in intricately carved ostrich eggshells . They made glues to craft containers, adorned themselves with beads, painted with multi-ingredient pigments, and etched geometric patterns into shells, stones, and bones.

These kinds of hyper-complex, multi-sequence behaviors cannot simply be imitated. They require explanation. So, when researchers see multiple instances of abstract art and creative crafts, we assume individuals were engaging in deep, intricate communication based on shared meanings.

By at least 40,000 to 50,000 years ago, representational art arose : depictions of hunts, animal-human hybrids, blazing sunsets, and hand prints waving, as if they are signaling meaning across the deep gap of time.

Once groups are attributing shared meaning to objects they can manipulate, it is an easy jump to give shared meaning to larger elements they cannot change: storms, floods, earthquakes, volcanoes, eclipses, and even death. We have evidence that by at least a few hundred thousand years ago, early humans were placing their dead in caves . Within the past 50,000 years, distinct examples of burial practices became more and more common.

Through language, deeply held thoughts and imaginings could be transferred rapidly and effectively from individuals to small groups to wider populations. This created large-scale shared structures of meaning—what we call belief systems.

Between about 4,000 to 15,000 years ago, numerous radical transitions occurred in many populations. Humans started to domesticate plants and animals. They developed, along with agriculture, substantial food storage capacities and technologies. Concepts of property and inequality emerged. Towns and, eventually, cities grew. All of this led to the formation of multi-community settlements with stratified political and economic structures.

This restructuring profoundly shaped, and was shaped by, belief systems. Toward the end of this period—by 4,000 to 8,000 years ago—we see clear evidence of formal religious institutions: monuments, gathering places, sanctuaries, and altars.

There are numerous explanations for the evolution of religions, and none of them by itself is satisfactory. Some proposals are psychological: Our ancestors understood that other individuals have different mental states, motivation, and agency, so they attributed those same qualities to supernatural agents to explain everything from lightning to illness.

Other researchers note that the rise of huge, hierarchical communities that engaged in large-scale cooperation and warfare correlated with the rise of far-reaching, hierarchical religions with powerful, moralizing deities. Some scientists posit that “big groups” prompted the creation of “big gods” who could enforce order and cooperation in unruly societies. Other researchers hypothesize the reverse: that humans first created “big god” religions in order to coordinate larger and larger social groups.

Still other experts say the human capacity for imagination became so expansive it reached beyond the real and the possible into the unreal and the impossible. This generated the capacity for transcendence—a central feature in the religious experience.

But though belief can be transcendent, creative, and unifying, not all of humanity’s beliefs are beneficial.

For example, many humans today believe the world should be exploited for our benefit. Many believe that racial, gendered, and xenophobic inequalities are a “natural” result of inherent differences. Many believe in religious, scientific, or political fundamentalism, which is often used as a weapon against other belief systems.

Over the past 2 million years, we have evolved a capacity that has benefited humans but can also introduce horrible possibilities. It is up to us to manage how we use this power.

Now that we have asked, Why do we believe? , we should ask, What do we want to believe, for the sake of humanity?

This article was republished on discovermagazine.com .

Agustín Fuentes is a professor of anthropology at Princeton University. He focuses on the biosocial, delving into the entanglement of biological systems with the social and cultural lives of humans, our ancestors, and a few other animals with whom humanity shares close relations. Earning his B.A./B.S. in anthropology and zoology and his M.A. and Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of California, Berkeley, he has conducted research across four continents, multiple species, and 2 million years of human history. His current projects include exploring cooperation, creativity, and belief in human evolution, multispecies anthropologies, evolutionary theory and processes, sex/gender, and engaging race and racism. Fuentes’ books include Race, Monogamy, and Other Lies They Told You: Busting Myths About Human Nature , The Creative Spark: How Imagination Made Humans Exceptional , and Why We Believe: Evolution and the Human Way of Being .

Religion – The Origin of Humanity Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Literature review, works cited.

The answer to origin of humanity can be traced through evolution of culture of religion. Religion has been in existence since the earlier man’s period, and records that show that some form of gods were worshipped, which can be found on caves and statutes. In addition, practices by Homo sapiens of burying their dead indicate the existence of religion. Religion also appears to be the only unique practice with human beings.

On the other hand, Darwin model of evolution indicates that through adaptation and selection, there were some forms of changes that took place in earlier organism.

By treating religion like some organism, it is possible to explore some its adaptability and selection, which made human beings more superior than other animals. In such cases, certain attributes of a religion succeeded to the next form. Within these trends of religion, it can be possible to trace exactly the period and the type of religious belief that led to humanity perception in human beings.

This paper explores the argument of other Paleolithic’s and archeologist on the origin of religion. It also explores the transformation of the first form of religion to modern type. Then in a generative discussion, it proceeds to argue that cultural changes in religion as opposed to brain development or species evolution are responsible for the change in human perception of themselves.

Mind Development

The past holds the key to understand the present and this is in archaeology hands (Mithens 10). His archeological work looks at how the human brain developed overtime by overcoming various selective pressures. According to his argument, the mind not only creates but is also capable of imagination. He disputed information from evolutionist psychologist, which argued that the mind can act like Swiss army knife.

He argued that when looking at the brain this way, it would not be possible to understand why modern brain is able to perform tasks not present in the ancestral periods. Instead, he suggests that general intelligence exists. Using a cathedral metaphor, he describes three stages of mind development. First is domination by general intelligence, which is supplemented by domain specific modules, and lastly these modules work in concert with an endless information flow to all domains.

After describing his architecture of the brain, he explored the various human evolution stages to describe the various selective pressures present. His journey begins with the exploration of the ape, common human ancestor. In this stage, he makes several deductions including that due to Chimpanzee problems in tool making, they lack technical intelligence and therefore only general intelligence can describe their behavior (Mithen 34).

He also concludes that they posses certain levels of natural history intelligence and social intelligence. The latter is due to their ability to interact. Finally, he attributes their inability to communicate to their low level of general intelligence.

The next human evolution he described is the Homo Habilis. For these, he finds their ability to form shaped tools as an indication of development of certain technical knowledge as opposed to just general intelligence, which cannot be associated with this kind or craftsmanship. As for other types of intelligence like natural history, he considers some development to have taken place. According to him, brain development reached its climax in the neanderthalensis or Homo sapiens species.

Their natural history intelligence was also more developed especially because of the increased demands by the environment. He further points to existing tools in this period as indications of improved technical intelligence (Mithen 38). To him, these humans had knowledge and abilities equivalent to the present human beings. However, he also observes that they lacked the connection between natural history intelligence and technical intelligence necessary to design multiple-purpose tools.

According to his argument, modern culture originated from increased assimilation of various specialized modules. Therefore, human beings developed objects such as artifacts to communicate social messages. In time, human also demonstrated abilities to read the mind of others as indicated by art work in the time. To him, human beings increased in flexibility on social abilities.

Darwin’s Evolution Theory

His evolution theory consists of two assumptions. The first one is that all living things share the same ancestor. Second is that of natural selection, which explains why existing living things are not similar. Therefore under natural selection, differences occur through DNA mutations.

Some mutation changes to the species characteristics can result into improved reproduction. As a result, this change enables species to survive to the next generation. Species that adapt well to a certain environment are likely to undergo little change in an environment.

Mutation though is said to be progressive even in such environment, only that now the species would remain the same. On the other hand, when the environment is changing or dynamic, the evolvement of a species would be fast. Adaptations previously enjoyed in such an occurrence would cease to be of any benefit to the species. Mutations that take place in this stage would result into changes that make the species fit into the new conditions, and the new genes would be reproduced among generations (ASSS 11).

Apart from natural selection evolution is also a factor of sexual selection. Various male species compete for sexual partners by putting on show, brilliant colors, complex calls, and other physical attributes. As for the female partner, preference is on impressive males. Consequently, these are able to get more of their DNA in the next generation. As a result, some of the traits that are attractive but have little benefit for survival are distributed in a population, like the peacock tail.

Empirical Evidence for evolution

Darwin’s theory of evolution is characterized by changes and adaptation and suggests a common ancestry for all forms of life (Ridley 44). In the contemporary society, molecular biology and chemistry evidence have continued to support his argument; that is, all living things’ physical bodies are made of same basic cells and these are made up of similar molecules.

Similarities of cells between species are more than the differences that have been observed. Anatomical structure across species are said to be more similar. For instance, frogs, rabbits, lizards and birds all have a similar bone arrangement in their forelimb, in spite of the different ways they are used.

Transitional fossils also provide other evidence for evolution of species. They record changes that take place in species across lines separating one body plan to the other and across species as well.

Evidence gathered from them points that a chronology from land mammals to whales as well as dinosaur to birds took place. It has also been verified that as expected, the most primitive organism live in deepest geological layers and complexity and variety of fossil organism increases with the layer preceding the other as one progress to the earth.

Another premise held is that related species should be close to one another both in time and space and have more similarities with existing species in their specific regions as opposed to others living elsewhere. This has been found to be true although at times, fossils of a species are not found in its habitat. Evolutionary theory explains this as a result of migration to other areas, which has been verified by scientific evidence (ASSS 12).

Questioning Darwin Theory of Evolution

The first argument put against it, challenges the first hypothesis of a common ancestry. This hypothesis suggests that all forms of life have a similar origin. It relies on argument that all species have the same DNA or genetic code, to support the similar origin.

Critics of this position argue that God used a common design plan to make the various types of living things that he created. However, they also observe that by arguing so, it might be easy to believe that similarities in various species are due to the shared ancestry or relatedness (Zacharias & Geiser 45).

One of the weaknesses of this theory is that in its argument there are no transitional species. We learn that when Darwin was challenged to defend this weakness, he said that these would be discovered in the long run. However, up to date this has not happened. Instead, just a few transitional species to date have been discovered.

However, critics argue that if his theory was true, millions of these transitional animals would be discovered in the fossils records. They therefore conclude that, although DNA argument backs the common ancestry for this theory the lack of evidence in fossil records circumvents it.

The other level of criticism challenges the mutations forces of change ability to produce new species that have certain traits making them competitive in an environment. Zacharias & Geisler argue that there is no evidence that exist today that supports ability of any mechanism to produce complex living things that exists in the world today, from single celled living things (46).

They further say that the existing evidence on the rate of change, challenges this premise. By examining other work which describes the taxonomy of evolution, they conclude that this would be impossible especially because of the long process.

The second issue taken with Darwin’s theory hypothesis of natural selection is in its inability to explain the source of irreducibly complex system. This particularly takes offense, with some of the suggestions that piecemeal changes can take place. They observe that some parts of the organs would not accommodate such piecemeal changes. In addition, no scientific evidence exists to explain that this kind of piecemeal changes could have existed (Zacharias & Geisler 47).

Biblical understanding of the World

In the nineteenth century, many Europeans believed that God inspired the Bible and that it represented the truth in all respect. From this believe they proceeded to hold that, Creations was directed by God working on his own, that he was actively engaged in it, and he created each species in its original kind and form (ASSS 7).

One of the books of the Bible called Genesis claims that human beings seized a unique place in this formation because they were the last to be created, were made in God’s own image, and were given the powers to dominate the earth.

Emergence of religion

It is not definite when religion began, although evidence points that there of the religion’s main characteristics can be traced back to Upper Paleolithic Revolution. These are shamanism, ancestor worship and belief in supernatural (Rossano 3). This period is about 40,000 years ago.

In this period the cultural changes by the Homo sapiens were evident. The brain of the Homo sapiens did not change, rather it is their capacity to transmit and develop culture. As a result of this form of change these species were able to have some form of symbolism practices in the form of statutes, burial of the dead and cave art.

The earlier man used these caves for more than just aesthetic value, to other purposes like religion. In these caves, graphics of mixture of animals and human have been discovered. They focused their artistic form of worship with their practices of biological necessities that is reproduction through genes transmission and food for survival. The period that followed was Neolithic revolution or agrarian revolution. In this period, food was available in abundance due to agriculture and domestication of animals.

As a result, populations exploded and there was an improved chance for survival. Consequently there was need for more organized religion to bring some form of social order (Hoffman, 1). Diamond argued that this form of religion was important for social cohesion among individuals who otherwise would be great enemies (277). Furthering this point he argued murder was the main cause of death for hunters’ gatherers community.

Polytheism emerged, which is the belief of multiple gods. This was practice in ancient Egypt, Greece and India. In spite of it being developed by a more developed human society, it also retained many attributes of the previous religion. For instance supernatural beliefs continued with statues and cave paintings.

Both these symbolism contained either animal or human features, or both. For instance, animal gods like those of Egyptians or the Hinduism gods of elephant and cows. These gods had specific roles that they played, like war travelers and so on. This element of worshipping god for specific roles was also common in earlier religion, like for purposes of hunting. In this period there was also pantheism form of religion which involves finding peace in oneself. Its faith is based on belief that everything in the world is divine.

Belief in polytheism not only involved personification of god, but also there was belief in the enlargement of the family. That is faith could be expanded by adding on more gods in the family. In this family, some gods whose roles were not significant were demoted to a low rank in the hierarchy.

This then brings us to the question of who among the many gods was supreme. Within the polytheistic religion supreme gods can be traced such as Zeus of the ancient Greek, who was known as the god of all gods. As for Hinduism they had their Brahma who was considered as creator of universe. These trends in religion were followed by Abraham religion prophets that led to monotheism (Hoffman 1).

This new type of religion involved the worshipping of a single God. Before Abrahamic religion, monotheism existed in the form of Zoroastrianism. This was founded in 6 th century BC by a priest known as Zarathustra. He preceded Jesus and Muhammad in converting people to monotheism from polytheism religion.

According to Zoroastrianism teachings, there is only one god and he is the one who created the earth and living and non living things in it. Some of the beliefs that Abrahamic religions adopted are from this earlier form of monotheism. These include concepts of heaven and hell, as well as unchanging cod. Judaism as founded by Abraham though is the largest form f monotheism.

This new religion began in the Middle East around 2000 BC with Judaism being the first form and prophesized by Abraham. Around 33 CE Jesus brought his message of Christianity. Finally at 622 CE, the last form of monotheism, which was Islamic religion, was started by Prophet Muhammad (Hoffman 1).

These religions believed in one god and the message about this god was spread by a human being sent by him. In the new form of religion only one God is to be worshiped and this god was the creator of everything. The new god did not in any way look like human beings.

Morality and living in groups

Although morality is a unique characteristic in humans, other animals that live in groups also exhibits some forms of pre-moral sentiments. Apes for instance practice social bonding, conflict resolution and peacemaking and other forms of morality issues. To facilitate the well being of the groups social animals, are forced to give up some of their individual needs. Within these groups there is social ranking and each animal understands it place in the hierarchy.

Animals such as the chimpanzee have been found to live in these forms of social groupings. In the same line based on the type of live they lived, early men are also presumed to have lived in similar groups. Therefore to control these groups morality is also likely to have evolved to minimize conflict, social control, and for solidarity in the group. However, unlike animals human morality is more complex in that it has stiffer regulation mechanism such as rewards and punishment as well as development of reputation.

More so, human have better judgment and reasoning than animals. Some psychologists have argued that religion developed after morality, and advanced it to include other methods of examining people’s behavior like supernatural beliefs. Through the use of the supernatural powers of ancestors for instance, humans were able to develop more powerful groups that limited selfishness among individuals. In this way religion adaptability helped to improve the chance of group to survive (Rossano 146).

In Darwin’s evolutionary theory argument, making of tools and sexual selection comes out as distinct ways of differentiating humanity from animals. However, from our argument human beings are not the only animals that are known to practice social bonding or make tools. In addition, their brain development is not a factor of expansion of the skull per-se but rather an indication of changing cultural behaviors.

Religion is one such cultural behavior that has transformed for a long time in the history of mankind. Since the early man in the Neolithic times some forms of religion have been practiced by human beings. Rituals like burying of their dead and existence of some painting and statutes have been highlighted as indication of religion in these trends. In addition, human beings are the only animals that have been observed to practice religious activities. This makes emergence of religion as one of the things that differentiate humanity from animals.

Advancing Science Serving Society (ASSS). The Evolution Dialogues . nd. Web. Retrieved

Diamond, Jarred. From Egalitarian to Kleptocracy, the Evolution of Government and Religion. In Guns Germs and Steel , Chap. 14: 277. New York, Norton. 1997. Print.

Hoffman, Howard. “The Emergence and Evolution of Belief, Religion, and the Concept of God Pt II”. serendip, serendip, 15 May 2009. Web.

Mithen, Steven J. The Prehistory of the Mind: The Cognitive Origins of Art, Religion and Science . London: Thames & Hudson, 1996. Print.

Ridley, Mark. Evolution. Malden . Wiley-Blackwell. 2004. Print.

Rossano, Matt J. Supernaturalizing Social Life: Religion and the Evolution of Human Cooperation. Southeastern Louisiana University. 2007. JSTOR PDF files.

- What is religious fundamentalism?

- Divine Revelation and the Mystery of the Blessed Trinity

- Monotheistic Religion of Pharaoh Akhenaten

- Judaism as a Monotheistic Religion

- Zoroastrianism Beliefs in Judaism and Christianity

- Creationism vs. Evolutionism: The Impacts of Religion

- Tirmidhi and His Characteristics

- Create Your Own Religion

- Literature Study on Myth Related Theories

- The Parable of the Sower

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, December 27). Religion - The Origin of Humanity. https://ivypanda.com/essays/religion-the-origin-of-humanity/

"Religion - The Origin of Humanity." IvyPanda , 27 Dec. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/religion-the-origin-of-humanity/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Religion - The Origin of Humanity'. 27 December.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Religion - The Origin of Humanity." December 27, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/religion-the-origin-of-humanity/.

1. IvyPanda . "Religion - The Origin of Humanity." December 27, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/religion-the-origin-of-humanity/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Religion - The Origin of Humanity." December 27, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/religion-the-origin-of-humanity/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

Origins of Religion - A Historical and Methodological Review

This paper will examine some of the theories on the origins of religion in humankind. This will be done to analyze a wide range of ideas from sociologists, anthropologists, psychologists and others at different times of history and using different methodologies. It will then attempt to gauge the progression of ideas on the subject matter in order to gain an interdisciplinary understanding of religion and thoughts on the capability and direction of future research.

Related papers

From the beginning of early man to modern times, the constant factor within our culture has been religion. No other organization or cultural facet has a greater influence on individual, group, cultural, and regional groupings. The inception/origins of religion, though widely varied by academics, rarely have an answer that is acceptable by the majority. Within the book Religion Explained, [4] Boyer states the following on this multitude.In this essay, we will attempt to redefine the parameters for religions inception by using modern understanding of our species cognitive capacities and behaviors. This is an attempt at generating Behavioral Mechanics that are independent of the context they are formed from. With these a framework will be designed that will determine what logically could have lead to the creation of individual and group prehistoric religious models that were then carried into written history. The Cognitive, behavioral, and social functions of Homo sapiens will be the only methodology applied. Regional doctrine and ideologies referenced will only be done as examples and not as defining progressions. The afor ementioned portions of religion are the result of its origins and not predating the inception. We will start with humankind obtaining self-awareness and moving forward to formulating an argument for religious generation.

From the beginning of early man to modern times, the constant factor within our culture has been religion. No other organization or cultural facet has a greater influence on individual, group, cultural, and regional groupings. The inception/origins of religion, though widely varied by academics, rarely have an answer that is acceptable by the majority. Within the book Religion Explained, [4] Boyer states the following on this multitude.In this essay, we will attempt to redefine the parameters for religions inception by using modern understanding of our species cognitive capacities and behaviors. This is an attempt at generating Behavioral Mechanics that are independent of the context they are formed from. With these a framework will be designed that will determine what logically could have lead to the creation of individual and group prehistoric religious models that were then carried into written history. The Cognitive, behavioral, and social functions of Homo sapiens will be the o...

Open Journal of Philosophy, vol. 10(3), pp. 346-367, 2020

Religion emerged among early humans because both purposive and non-purposive explanations were being employed but understanding was lacking of their precise scope and limits. Given also a context of very limited human power, the resultant foregrounding of agency and purposive explanation expressed itself in religion's marked tendency towards anthropomorphism and its key role in legitimizing behaviour. The inevitability of death also structures the religious outlook; with ancestors sometimes assigned a role in relation to the living. Subjective elements such as the experience of dreams and the internalization of moral precepts also play their part. Two important sources of variation among religions concern the adoption of a dualist or non-dualist perspective, and whether or not the religion's early political experience is such as to generate a systematic doctrine subordinating politics to religion. The near ubiquity and endurance of religion are further illuminated by analysis of its functions and ideological role. Religion tends to be socially conservative but has the potential to be revolutionary.

It is next to impossible to know when the first religion was born but archeological records can offer some answers. Archaeologists and social anthropologists study intentional human burials, religious symbols including pictorials and figurines to construct their understanding of the origin of religion. Since many researchers hold that religious symbols tell us a lot about the origins of religion, there is an evidence that as far back as100,000 years ago, people at the South African site of Blombos Cave incised pieces of ochre with geometric designs, creating the first widely recognized signs of symbolic behavior.

Ethology of Religion, which goes back to Charles Darwin himself who revealed in his book The expression of the emotions in man and animals (1872) that any form of behavior is just as important for the survival of the species as the adaptation of morphological structures in the course of their phylogenetic histories. In the humanities this approach was adapted by skilled scholars such as Karl Meuli (1891–1968), Aby Warburg (1866–1929), and currently by Roy Rappaport (1926–1997), Marvin Harris (1927–2001) and others. They were able to outline both human universals and the historical development (evolution) of religious behavior. According to the protagonists of this ethological approach and according to recent biology religion is deeply rooted in the biological human heritage. Inherited behavioral patterns did not only form the main patterns of ritual and iconography, but are most probably at least partly responsible for the origin of religion itself.

This article examines three anthropological theories explaining how religion has evolved and continues to evolve. They are: commitment theory, which postulates that religion is a system of costly signaling that reduces deception and creates cooperation within groups; cognitive theory, which postulates that religion is the manifestation of mental modules that have evolved for other purposes; and ecological regulation theory, which postulates that religion is a master control system regulating the interaction of human groups with their environments. An assessment of the success of the theories is offered. The idea that the biological evolution of the capacity for religion is based on the group selection rather than individual selection is rejected as unnecessary. The relationship between adaptive systems and culturally transmitted sacred values is examined cross-culturally, and the three theories are integrated into an overall gene-culture view of religion that includes both the biological evolution and the cultural evolution of behavioral systems.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

Olu Mike Omoasegun, 2012

Suicidal Utopian Delusions in the 21st Century Philosophy, Human Nature and the Collapse of Civilization Articles and Reviews 2006-2019 4th Edition , 2019

Society, Technology, Language, and Religion, 2013

Routledge Monograph, 2021

Philosophy, Human Nature and the Collapse of Civilization -- Articles and Reviews 2006-2017 3rd Ed 686p(2017)

Estudios de Psicología, 2011

Journal for The Study of Religion, Nature and Culture, 2010

Anpere: Anthropological Perspectives on Religion, 2007

Method & Theory in The Study of Religion, 1998

Studies in Religion, 2012

Oxford Handbooks Online, 2007

Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2000

HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies, 2010

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

13.1 What Is Religion?

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Distinguish between religion, spirituality, and worldview.

- Describe the connections between witchcraft, sorcery, and magic.

- Identify differences between deities and spirits.

- Identify shamanism.

- Describe the institutionalization of religion in state societies.

Defining Religion, Spirituality, and Worldview

An anthropological inquiry into religion can easily become muddled and hazy because religion encompasses intangible things such as values, ideas, beliefs, and norms. It can be helpful to establish some shared signposts. Two researchers whose work has focused on religion offer definitions that point to diverse poles of thought about the subject. Frequently, anthropologists bookend their understanding of religion by citing these well-known definitions.

French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1858–1917) utilized an anthropological approach to religion in his study of totemism among Indigenous Australian peoples in the early 20th century. In his work The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1915), he argues that social scientists should begin with what he calls “simple religions” in their attempts to understand the structure and function of belief systems in general. His definition of religion takes an empirical approach and identifies key elements of a religion: “A religion is a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and forbidden—beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them” (47). This definition breaks down religion into the components of beliefs, practices, and a social organization—what a shared group of people believe and do.

The other signpost used within anthropology to make sense of religion was crafted by American anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1926–2006) in his work The Interpretation of Cultures (1973). Geertz’s definition takes a very different approach: “A religion is: (1) a system of symbols which acts to (2) establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by (3) formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and (4) clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that (5) the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic” (90). Geertz’s definition, which is complex and holistic and addresses intangibles such as emotions and feelings, presents religion as a different paradigm , or overall model, for how we see systems of belief. Geertz views religion as an impetus to view and act upon the world in a certain manner. While still acknowledging that religion is a shared endeavor, Geertz focuses on religion’s role as a potent cultural symbol. Elusive, ambiguous, and hard to define, religion in Geertz’s conception is primarily a feeling that motivates and unites groups of people with shared beliefs. In the next section, we will examine the meanings of symbols and how they function within cultures, which will deepen your understanding of Geertz’s definition. For Geertz, religion is intensely symbolic.

When anthropologists study religion, it can be helpful to consider both of these definitions because religion includes such varied human constructs and experiences as social structures, sets of beliefs, a feeling of awe, and an aura of mystery. While different religious groups and practices sometimes extend beyond what can be covered by a simple definition, we can broadly define religion as a shared system of beliefs and practices regarding the interaction of natural and supernatural phenomena. And yet as soon as we ascribe a meaning to religion, we must distinguish some related concepts, such as spirituality and worldview.

Over the last few years, a growing number of Americans have been choosing to define themselves as spiritual rather than religious. A 2017 Pew Research Center study found that 27 percent of Americans identify as “spiritual but not religious,” which is 8 percentage points higher than it was in 2012 (Lipka and Gecewicz 2017). There are different factors that can distinguish religion and spirituality, and individuals will define and use these terms in specific ways; however, in general, while religion usually refers to shared affiliation with a particular structure or organization, spirituality normally refers to loosely structured beliefs and feelings about relationships between the natural and supernatural worlds. Spirituality can be very adaptable to changing circumstances and is often built upon an individual’s perception of the surrounding environment.

Many Americans with religious affiliation also use the term spirituality and distinguish it from their religion. Pew found in 2017 that 48 percent of respondents said they were both religious and spiritual. Pew also found that 27 percent of people say religion is very important to them (Lipka and Gecewicz 2017).

Another trend pertaining to religion in the United States is the growth of those defining themselves as nones , or people with no religious affiliation. In a 2014 survey of 35,000 Americans from 50 states, Pew found that nearly a quarter of Americans assigned themselves to this category (Pew Research Center 2015). The percentage of adults assigning themselves to the “none” category had grown substantially, from 16 percent in 2007 to 23 percent in 2014; among millennials, the percentage of nones was even higher, at 35 percent (Lipka 2015). In a follow-up survey, participants were asked to identity their major reasons for choosing to be nonaffiliated; the most common responses pointed to the growing politicization of American churches and a more critical and questioning stance toward the institutional structure of all religions (Pew Research Center 2018). It is important, however, to point out that nones are not the same as agnostics or atheists. Nones may hold traditional and/or nontraditional religious beliefs outside of membership in a religious institution. Agnosticism is the belief that God or the divine is unknowable and therefore skepticism of belief is appropriate, and atheism is a stance that denies the existence of a god or collection of gods. Nones, agnostics, and atheists can hold spiritual beliefs, however. When anthropologists study religion, it is very important for them to define the terms they are using because these terms can have different meanings when used outside of academic studies. In addition, the meaning of terms may change. As the social and political landscape in a society changes, it affects all social institutions, including religion.

| Religious Affiliation | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Christian | 70.6% |

| Jewish | 1.9% |

| Muslim | 0.9% |

| Buddhist | 0.7% |

| Hindu | 0.7% |

| *Unaffiliated/Nones | 22.8% |

Even those who consider themselves neither spiritual nor religious hold secular, or nonreligious, beliefs that structure how they view themselves and the world they live in. The term worldview refers to a person’s outlook or orientation; it is a learned perspective, which has both individual and collective components, on the nature of life itself. Individuals frequently conflate and intermingle their religious and spiritual beliefs and their worldviews as they experience change within their lives. When studying religion, anthropologists need to remain aware of these various dimensions of belief. The word religion is not always adequate to identify an individual’s belief systems.

Like all social institutions, religion evolves within and across time and cultures—even across early human species! Adapting to changes in population size and the reality of people’s daily lives, religions and religious/spiritual practices reflect life on the ground . Interestingly, though, while some institutions (such as economics) tend to change radically from one era to another, often because of technological changes, religion tends to be more viscous , meaning it tends to change at a much slower pace and mix together various beliefs and practices. While religion can be a factor in promoting rapid social change, it more commonly changes slowly and retains older features while adding new ones. In effect, religion contains within it many of its earlier iterations and can thus be quite complex.

Witchcraft, Sorcery, and Magic

People in Western cultures too often think of religion as a belief system associated with a church, temple, or mosque, but religion is much more diverse. In the 1960s, anthropologists typically used an evolutionary model for religion that associated less structured religious systems with simple societies and more complex forms of religion with more complex political systems. Anthropologists noticed that as populations grew, all forms of organization—political, economic, social, and religious—became more complex as well. For example, with the emergence of tribal societies, religion expanded to become not only a system of healing and connection with both animate and inanimate things in the environment but also a mechanism for addressing desire and conflict. Witchcraft and sorcery, both forms of magic, are more visible in larger-scale, more complex societies.

The terms witchcraft and sorcery are variously defined across disciplines and from one researcher to another, yet there is some agreement about common elements associated with each. Witchcraft involves the use of intangible (not material) means to cause a change in circumstances to another person. It is normally associated with practices such as incantations, spells, blessings, and other types of formulaic language that, when pronounced, causes a transformation. Sorcery is similar to witchcraft but involves the use of material elements to cause a change in circumstances to another person. It is normally associated with such practices as magical bundles, love potions, and any specific action that uses another person’s personal leavings (such as their hair, nails, or even excreta). While some scholars argue that witchcraft and sorcery are “dark,” negative, antisocial actions that seek to punish others, ethnographic research is filled with examples of more ambiguous or even positive uses as well. Cultural anthropologist Alma Gottlieb , who did fieldwork among the Beng people of Côte d’Ivoire in Africa, describes how the king that the Beng choose as their leader must always be a witch himself, not because of his ability to harm others but because his mystical powers allow him to protect the Beng people that he rules (2008). His knowledge and abilities allow him to be a capable ruler.

Some scholars argue that witchcraft and sorcery may be later developments in religion and not part of the earliest rituals because they can be used to express social conflict. What is the relationship between conflict, religion, and political organization? Consider what you learned in Social Inequalities . As a society’s population rises, individuals within that society have less familiarity and personal experience with each other and must instead rely on family reputation or rank as the basis for establishing trust. Also, as social diversity increases, people find themselves interacting with those who have different behaviors and beliefs from their own. Frequently, we trust those who are most like ourselves, and diversity can create a sense of mistrust. This sense of not knowing or understanding the people one lives, works, and trades with creates social stress and forces people to put themselves into what can feel like risky situations when interacting with one another. In such a setting, witchcraft and sorcery provide a feeling of security and control over other people. Historically, as populations increased and sociocultural institutions became larger and more complex, religion evolved to provide mechanisms such as witchcraft and sorcery that helped individuals establish a sense of social control over their lives.

Magic is essential to both witchcraft and sorcery, and the principles of magic are part of every religion. The anthropological study of magic is considered to have begun in the late 19th century with the 1890 publication of The Golden Bough , by Scottish social anthropologist Sir James G. Frazer . This work, published in several volumes, details the rituals and beliefs of a diverse range of societies, all collected by Frazer from the accounts of missionaries and travelers. Frazer was an armchair anthropologist, meaning that he did not practice fieldwork. In his work, he provided one of the earliest definitions of magic, describing it as “a spurious system of natural law as well as a fallacious guide of conduct” (Frazer [1922] 1925, 11). A more precise and neutral definition depicts magic as a supposed system of natural law whose practice causes a transformation to occur. In the natural world—the world of our senses and the things we hear, see, smell, taste, and touch—we operate with evidence of observable cause and effect. Magic is a system in which the actions or causes are not always empirical. Speaking a spell or other magical formula does not provide observable (empirical) effects. For practitioners of magic, however, this abstract cause and effect is just as consequential and just as true.

Frazer refers to magic as “sympathetic magic” because it is based on the idea of sympathy, or common feeling, and he argued that there are two principles of sympathetic magic: the law of similarity and the law of contagion. The law of similarity is the belief that a magician can create a desired change by imitating that change. This is associated with actions or charms that mimic or look like the effects one desires, such as the use of an effigy that looks like another person or even the Venus figurine associated with the Upper Paleolithic period, whose voluptuous female body parts may have been used as part of a fertility ritual. By taking actions on the stand-in figure, the magician is able to cause an effect on the person believed to be represented by this figure. The law of contagion is the belief that things that have once been in contact with each other remain connected always, such as a piece of jewelry owned by someone you love, a locket of hair or baby tooth kept as a keepsake, or personal leavings to be used in acts of sorcery.

This classification of magic broadens our understanding of how magic can be used and how common it is across all religions. Prayers and special mortuary artifacts ( grave goods ) indicate that the concept of magic is an innately human practice and not associated solely with tribal societies. In most cultures and across religious traditions, people bury or cremate loved ones with meaningful clothing, jewelry, or even a photo. These practices and sentimental acts are magical bonds and connections among acts, artifacts, and people. Even prayers and shamanic journeying (a form of metaphysical travel) to spirits and deities, practiced in almost all religious traditions, are magical contracts within people’s belief systems that strengthen practitioners’ faith. Instead of seeing magic as something outside of religion that diminishes seriousness, anthropologists see magic as a profound human act of faith.

Supernatural Forces and Beings

As stated earlier, religion typically regards the interaction of natural and supernatural phenomena. Put simply, a supernatural force is a figure or energy that does not follow natural law. In other words, it is nonempirical and cannot be measured or observed by normal means. Religious practices rely on contact and interaction with a wide range of supernatural forces of varying degrees of complexity and specificity.

In many religious traditions, there are both supernatural deities, or gods who are named and have the ability to change human fortunes, and spirits, who are less powerful and not always identified by name. Spirit or spirits can be diffuse and perceived as a field of energy or an unnamed force.

Practitioners of witchcraft and sorcery manipulate a supposed supernatural force that is often referred to by the term mana , first identified in Polynesia among the Maori of New Zealand ( mana is a Maori word). Anthropologists see a similar supposed sacred energy field in many different religious traditions and now use this word to refer to that energy force. Mana is an impersonal (unnamed and unidentified) force that can adhere for varying periods of time to people or animate and inanimate objects to make them sacred. One example is in the biblical story that appears in Mark 5:25–30, in which a woman suffering an illness simply touches Jesus’s cloak and is healed. Jesus asks, “Who touched my clothes?” because he recognizes that some of this force has passed from him to the woman who was ill in order to heal her. Many Christians see the person of Jesus as sacred and holy from the time of his baptism by the Holy Spirit. Christian baptism in many traditions is meant as a duplication or repetition of Christ’s baptism.

There are also named and known supernatural deities. A deity is a god or goddess. Most often conceived as humanlike, gods (male) and goddesses (female) are typically named beings with individual personalities and interests. Monotheistic religions focus on a single named god or goddess, and polytheistic religions are built around a pantheon, or group, of gods and/or goddesses, each usually specializing in a specific sort of behavior or action. And there are spirits , which tend to be associated with very specific (and narrower) activities, such as earth spirits or guardian spirits (or angels). Some spirits emanate from or are connected directly to humans, such as ghosts and ancestor spirits , which may be attached to specific individuals, families, or places. In some patrilineal societies, ancestor spirits require a great deal of sacrifice from the living. This veneration of the dead can consume large quantities of resources. In the Philippines, the practice of venerating the ancestor spirits involves elaborate house shrines, altars, and food offerings. In central Madagascar, the Merino people practice a regular “turning of the bones,” called famidihana . Every five to seven years, a family will disinter some of their deceased family members and replace their burial clothing with new, expensive silk garments as a form of remembrance and to honor all of their ancestors. In both of these cases, ancestor spirits are believed to continue to have an effect on their living relatives, and failure to carry out these rituals is believed to put the living at risk of harm from the dead.

Religious Specialists

Religious groups typically have some type of leadership, whether formal or informal. Some religious leaders occupy a specific role or status within a larger organization, representing the rules and regulations of the institution, including norms of behavior. In anthropology, these individuals are called priests , even though they may have other titles within their religious groups. Anthropology defines priests as full-time practitioners, meaning they occupy a religious rank at all times, whether or not they are officiating at rituals or ceremonies, and they have leadership over groups of people. They serve as mediators or guides between individuals or groups of people and the deity or deities. In religion-specific terms, anthropological priests may be called by various names, including titles such as priest, pastor, preacher, teacher, imam (Islam), and rabbi (Judaism).

Another category of specialists is prophets . These individuals are associated with religious change and transformation, calling for a renewal of beliefs or a restructuring of the status quo. Their leadership is usually temporary or indirect, and sometimes the prophet is on the margins of a larger religious organization. German sociologist Max Weber (1947) identified prophets as having charisma , a personality trait that conveys authority:

Charisma is a certain quality of an individual personality by virtue of which he is set apart from ordinary men and treated as endowed with supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional powers or qualities. These as such are not accessible to the ordinary person, but are regarded as of divine origin or as exemplary, and on the basis of them the individual concerned is treated as a leader. (358–359)

A third type of specialist is shamans . Shamans are part-time religious specialists who work with clients to address very specific and individual needs by making direct contact with deities or supernatural forces. While priests will officiate at recurring ritual events, a shaman, much like a medical psychologist, addresses each individual need. One exception to this is the shaman’s role in subsistence, usually hunting. In societies where the shaman is responsible for “calling up the animals” so that hunters will have success, the ritual may be calendrical , or occurring on a cyclical basis. While shamans are medical and religious specialists within shamanic societies, there are other religions that practice forms of shamanism as part of their own belief systems. Sometimes, these shamanic practitioners will be known by terms such as pastor or preacher , or even layperson . And some religious specialists serve as both part-time priests and part-time shamans, occupying more than one role as needed within a group of practitioners. You will read more about shamanism in the next section.

One early form of religion is shamanism , a practice of divination and healing that involves soul travel, also called shamanic journeying, to connect natural and supernatural realms in nonlinear time. Associated initially with small-scale societies, shamanic practices are now known to be embedded in many of the world’s religions. In some cultures, shamans are part-time specialists, usually drawn into the practice by a “calling” and trained in the necessary skills and rituals though an apprenticeship. In other cultures, all individuals are believed to be capable of shamanic journeying if properly trained. By journeying—an act frequently initiated by dance, trance, drumbeat, song, or hallucinogenic substances—the shaman is able to consult with a spiritual world populated by supernatural figures and deceased ancestors. The term itself, šamán , meaning “one who knows,” is an Evenki word, originating among the Evenk people of northern Siberia. Shamanism, found all over the world, was first studied by anthropologists in Siberia.

While shamanism is a healing practice, it conforms to the anthropological definition of religion as a shared set of beliefs and practices pertaining to the natural and supernatural. Cultures and societies that publicly affirm shamanism as a predominant and generally accepted practice often are referred to as shamanic cultures . Shamanism and shamanic activity, however, are found within most religions. The world’s two dominant mainstream religions both contain a type of shamanistic practice: the laying on of hands in Christianity, in which a mystical healing and blessing is passed from one person to another, and the mystical Islamic practice of Sufism, in which the practitioner, called a dervish, dances by whirling faster and faster in order to reach a trance state of communing with the divine. There are numerous other shared religious beliefs and practices among different religions besides shamanism. Given the physical and social evolution of our species, it is likely that we all share aspects of a fundamental religious orientation and that religious changes are added on to, rather than used to replace, earlier practices such as shamanism.

Indigenous shamanism continues to be a significant force for healing and prophecy today and is the predominant religious mode in small-scale, subsistence-based societies, such as bands of gatherers and hunters. Shamanism is valued by hunters as an intuitive way to locate wild animals, often depicted as “getting into the mind of the animal.” Shamanism is also valued as a means of healing, allowing individuals to discern and address sources of physical and social illness that may be affecting their health. One of the best-studied shamanic healing practices is that of the !Kung San in Central Africa. When individuals in that society suffer physical or socioemotional distress, they practice n/um tchai , a medicine dance, to draw up spiritual forces within themselves that can be used for shamanic self-healing (Marshall [1969] 2009).