- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: November 16, 2023 | Original: October 6, 2017

Hinduism is the world’s oldest religion, according to many scholars, with roots and customs dating back more than 4,000 years. Today, with more than 1 billion followers , Hinduism is the third-largest religion worldwide, after Christianity and Islam . Roughly 94 percent of the world’s Hindus live in India. Because the religion has no specific founder, it’s difficult to trace its origins and history. Hinduism is unique in that it’s not a single religion but a compilation of many traditions and philosophies: Hindus worship a number of different gods and minor deities, honor a range of symbols, respect several different holy books and celebrate with a wide variety of traditions, holidays and customs. Though the development of the caste system in India was influenced by Hindu concepts , it has been shaped throughout history by political as well as religious movements, and today is much less rigidly enforced. Today there are four major sects of Hinduism: Shaivism, Vaishnava, Shaktism and Smarta, as well as a number of smaller sects with their own religious practices.

Hinduism Beliefs, Symbols

Some basic Hindu concepts include:

- Hinduism embraces many religious ideas. For this reason, it’s sometimes referred to as a “way of life” or a “family of religions,” as opposed to a single, organized religion.

- Most forms of Hinduism are henotheistic, which means they worship a single deity, known as “Brahman,” but still recognize other gods and goddesses. Followers believe there are multiple paths to reaching their god.

- Hindus believe in the doctrines of samsara (the continuous cycle of life, death, and reincarnation) and karma (the universal law of cause and effect).

- One of the key thoughts of Hinduism is “atman,” or the belief in soul. This philosophy holds that living creatures have a soul, and they’re all part of the supreme soul. The goal is to achieve “moksha,” or salvation, which ends the cycle of rebirths to become part of the absolute soul.

- One fundamental principle of the religion is the idea that people’s actions and thoughts directly determine their current life and future lives.

- Hindus strive to achieve dharma, which is a code of living that emphasizes good conduct and morality.

- Hindus revere all living creatures and consider the cow a sacred animal.

- Food is an important part of life for Hindus. Most don’t eat beef or pork, and many are vegetarians.

- Hinduism is closely related to other Indian religions, including Buddhism , Sikhism and Jainism.

There are two primary symbols associated with Hinduism, the om and the swastika. The word swastika means "good fortune" or "being happy" in Sanskrit, and the symbol represents good luck . (A hooked, diagonal variation of the swastika later became associated with Germany’s Nazi Party when they made it their symbol in 1920.)

The om symbol is composed of three Sanskrit letters and represents three sounds (a, u and m), which when combined are considered a sacred sound. The om symbol is often found at family shrines and in Hindu temples.

Hinduism Holy Books

Hindus value many sacred writings as opposed to one holy book.

The primary sacred texts, known as the Vedas, were composed around 1500 B.C. This collection of verses and hymns was written in Sanskrit and contains revelations received by ancient saints and sages.

The Vedas are made up of:

- The Rig Veda

- The Samaveda

- Atharvaveda

Hindus believe that the Vedas transcend all time and don’t have a beginning or an end.

The Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, 18 Puranas, Ramayana and Mahabharata are also considered important texts in Hinduism.

Origins of Hinduism

Most scholars believe Hinduism started somewhere between 2300 B.C. and 1500 B.C. in the Indus Valley, near modern-day Pakistan. But many Hindus argue that their faith is timeless and has always existed.

Unlike other religions, Hinduism has no one founder but is instead a fusion of various beliefs.

Around 1500 B.C., the Indo-Aryan people migrated to the Indus Valley, and their language and culture blended with that of the indigenous people living in the region. There’s some debate over who influenced whom more during this time.

The period when the Vedas were composed became known as the “Vedic Period” and lasted from about 1500 B.C. to 500 B.C. Rituals, such as sacrifices and chanting, were common in the Vedic Period.

The Epic, Puranic and Classic Periods took place between 500 B.C. and A.D. 500. Hindus began to emphasize the worship of deities, especially Vishnu, Shiva and Devi.

The concept of dharma was introduced in new texts, and other faiths, such as Buddhism and Jainism, spread rapidly.

Hinduism vs. Buddhism

Hinduism and Buddhism have many similarities. Buddhism, in fact, arose out of Hinduism, and both believe in reincarnation, karma and that a life of devotion and honor is a path to salvation and enlightenment.

But some key differences exist between the two religions: Many strains of Buddhism reject the caste system, and do away with many of the rituals, the priesthood, and the gods that are integral to Hindu faith.

Medieval and Modern Hindu History

The Medieval Period of Hinduism lasted from about A.D. 500 to 1500. New texts emerged, and poet-saints recorded their spiritual sentiments during this time.

In the 7th century, Muslim Arabs began invading areas in India. During parts of the Muslim Period, which lasted from about 1200 to 1757, Islamic rulers prevented Hindus from worshipping their deities, and some temples were destroyed.

Mahatma Gandhi

Between 1757 and 1947, the British controlled India. At first, the new rulers allowed Hindus to practice their religion without interference, but the British soon attempted to exploit aspects of Indian culture as leverage points for political control, in some cases exacerbating Hindu caste divisions even as they promoted westernized, Christian approaches.

Many reformers emerged during the British Period. The well-known politician and peace activist, Mahatma Gandhi , led a movement that pushed for India’s independence.

The partition of India occurred in 1947, and Gandhi was assassinated in 1948. British India was split into what are now the independent nations of India and Pakistan , and Hinduism became the major religion of India.

Starting in the 1960s, many Hindus migrated to North America and Britain, spreading their faith and philosophies to the western world.

Hindus worship many gods and goddesses in addition to Brahman, who is believed to be the supreme God force present in all things.

Some of the most prominent deities include:

- Brahma: the god responsible for the creation of the world and all living things

- Vishnu: the god that preserves and protects the universe

- Shiva: the god that destroys the universe in order to recreate it

- Devi: the goddess that fights to restore dharma

- Krishna: the god of compassion, tenderness and love

- Lakshmi: the goddess of wealth and purity

- Saraswati: the goddess of learning

Places of Worship

Hindu worship, which is known as “puja,” typically takes place in the Mandir (temple). Followers of Hinduism can visit the Mandir any time they please.

Hindus can also worship at home, and many have a special shrine dedicated to certain gods and goddesses.

The giving of offerings is an important part of Hindu worship. It’s a common practice to present gifts, such as flowers or oils, to a god or goddess.

Additionally, many Hindus take pilgrimages to temples and other sacred sites in India.

Hinduism Sects

Hinduism has many sects, and the following are often considered the four major denominations.

Shaivism is one of the largest denominations of Hinduism, and its followers worship Shiva, sometimes known as “The Destroyer,” as their supreme deity.

Shaivism spread from southern India into Southeast Asia and is practiced in Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia as well as India. Like the other major sects of Hinduism, Shaivism considers the Vedas and the Upanishads to be sacred texts.

Vaishnavism is considered the largest Hindu sect, with an estimated 640 million followers, and is practiced worldwide. It includes sub-sects that are familiar to many non-Hindus, including Ramaism and Krishnaism.

Vaishnavism recognizes many deities, including Vishnu, Lakshmi, Krishna and Rama, and the religious practices of Vaishnavism vary from region to region across the Indian subcontinent.

Shaktism is somewhat unique among the four major traditions of Hinduism in that its followers worship a female deity, the goddess Shakti (also known as Devi).

Shaktism is sometimes practiced as a monotheistic religion, while other followers of this tradition worship a number of goddesses. This female-centered denomination is sometimes considered complementary to Shaivism, which recognizes a male deity as supreme.

The Smarta or Smartism tradition of Hinduism is somewhat more orthodox and restrictive than the other four mainstream denominations. It tends to draw its followers from the Brahman upper caste of Indian society.

Smartism followers worship five deities: Vishnu, Shiva, Devi, Ganesh and Surya. Their temple at Sringeri is generally recognized as the center of worship for the denomination.

Some Hindus elevate the Hindu trinity, which consists of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. Others believe that all the deities are a manifestation of one.

Hindu Caste System

The caste system is a social hierarchy in India that divides Hindus based on their karma and dharma. Although the word “caste” is of Portuguese origin, it is used to describe aspects of the related Hindu concepts of varna (color or race) and jati (birth). Many scholars believe the system dates back more than 3,000 years.

The four main castes (in order of prominence) include:

- Brahmin: the intellectual and spiritual leaders

- Kshatriyas: the protectors and public servants of society

- Vaisyas: the skillful producers

- Shudras: the unskilled laborers

Many subcategories also exist within each caste. The “Untouchables” are a class of citizens that are outside the caste system and considered to be in the lowest level of the social hierarchy.

For centuries, the caste system determined most aspect of a person’s social, professional and religious status in India.

HISTORY Vault: Ancient History

From the Sphinx of Egypt to the Kama Sutra, explore ancient history videos.

When India became an independent nation, its constitution banned discrimination based on caste.

Today, the caste system still exists in India but is loosely followed. Many of the old customs are overlooked, but some traditions, such as only marrying within a specific caste, are still embraced.

Hindus observe numerous sacred days, holidays and festivals.

Some of the most well-known include:

- Diwali : the festival of lights

- Navaratri: a celebration of fertility and harvest

- Holi: a spring festival

- Krishna Janmashtami: a tribute to Krishna’s birthday

- Raksha Bandhan: a celebration of the bond between brother and sister

- Maha Shivaratri: the great festival of Shiva

Hinduism Facts. Sects of Hinduism . Hindu American Foundation. Hinduism Basics . History of Hinduism, BBC . Hinduism Fast Facts, CNN .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

World history

Course: world history > unit 2.

- The rise of empires in India

- Gupta Dynasty

- The Maurya and Gupta Empires

- Empires in India

The history of Hinduism

- The history of Buddhism

- Key concepts: Hinduism and Buddhism

- Indian cultures: focus on Hinduism and Buddhism

- During the Maurya and Gupta empires, the Indian culture and way of life were deeply influenced by Hinduism.

- Hinduism reinforced a strict social hierarchy called a caste system that made it nearly impossible for people to move outside of their social station.

- Emperors during the Gupta empire used Hinduism as a unifying religion and focused on Hinduism as a means for personal salvation.

Background on social systems in India

Popularization of hinduism, what do you think.

- "Aryan." Ancient History Encyclopedia, 2013. http://www.ancient.eu/Aryan/

- Bentley, Jerry H. et. al. Traditions and Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past. New York: McGraw-Hill. 2015, 174-192.

- "Hinduism." Ancient History Encyclopedia, 2013. http://www.ancient.eu/hinduism/

- Strayer, Robert W. and Eric W. Nelson. Ways of the World: A Global History. United States: Bedford/St. Martin's Press, 2016, 157-202.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Hinduism and hindu art.

Krishna Killing the Horse Demon Keshi

Standing Four-Armed Vishnu

Linga with Face of Shiva (Ekamukhalinga)

Standing Parvati

Shiva as Lord of Dance (Nataraja)

Standing Ganesha

Standing Female Deity, probably Durga

Ardhanarishvara (Composite of Shiva and Parvati)

Vaikuntha Vishnu

Krishna on Garuda

Durga as Slayer of the Buffalo Demon Mahishasura

Seated Ganesha

Kneeling Female Figure

Hanuman Conversing

The Goddess Durga Slaying the Demon Buffalo Mahisha

Loving Couple (Mithuna)

Karaikkal Ammaiyar, Shaiva Saint

Vidya Dehejia Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University

February 2007

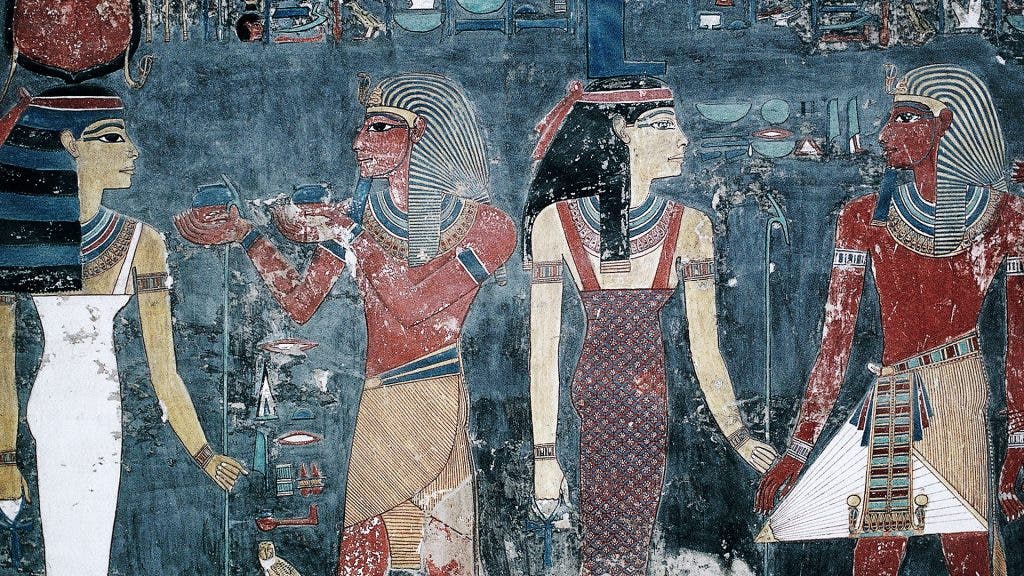

According to the Hindu view, there are four goals of life on earth, and each human being should aspire to all four. Everyone should aim for dharma , or righteous living; artha , or wealth acquired through the pursuit of a profession; kama , or human and sexual love; and, finally, moksha , or spiritual salvation.

This holistic view is reflected as well as in the artistic production of India. Although a Hindu temple is dedicated to the glory of a deity and is aimed at helping the devotee toward moksha , its walls might justifiably contain sculptures that reflect the other three goals of life. It is in such a context that we may best understand the many sensuous and apparently secular themes that decorate the walls of Indian temples.

Hinduism is a religion that had no single founder, no single spokesman, no single prophet. Its origins are mixed and complex. One strand can be traced back to the sacred Sanskrit literature of the Aryans, the Vedas, which consist of hymns in praise of deities who were often personifications of the natural elements. Another strand drew on the beliefs prevalent among groups of indigenous peoples, especially the faith in the power of the mother goddess and in the efficacy of fertility symbols. Hinduism, in the form comparable to its present-day expression, emerged at about the start of the Christian era, with an emphasis on the supremacy of the god Vishnu, the god Shiva, and the goddess Shakti (literally, “Power”).

The pluralism evident in Hinduism, as well as its acceptance of the existence of several deities, is often puzzling to non-Hindus. Hindus suggest that one may view the Infinite as a diamond of innumerable facets. One or another facet—be it Rama, Krishna, or Ganesha—may beckon an individual believer with irresistible magnetism. By acknowledging the power of an individual facet and worshipping it, the believer does not thereby deny the existence of many aspects of the Infinite and of varied paths toward the ultimate goal.

Deities are frequently portrayed with multiple arms, especially when they are engaged in combative acts of cosmic consequence that involve destroying powerful forces of evil. The multiplicity of arms emphasizes the immense power of the deity and his or her ability to perform several feats at the same time. The Indian artist found this a simple and an effective means of expressing the omnipresence and omnipotence of a deity. Demons are frequently portrayed with multiple heads to indicate their superhuman power. The occasional depiction of a deity with more than one head is generally motivated by the desire to portray varying aspects of the character of that deity. Thus, when the god Shiva is portrayed with a triple head, the central face indicates his essential character and the flanking faces depict his fierce and blissful aspects.

The Hindu Temple Architecture and sculpture are inextricably linked in India . Thus, if one speaks of Indian architecture without taking note of the lavish sculptured decoration with which monuments are covered, a partial and distorted picture is presented. In the Hindu temple , large niches in the three exterior walls of the sanctum house sculpted images that portray various aspects of the deity enshrined within. The sanctum image expresses the essence of the deity. For instance, the niches of a temple dedicated to a Vishnu may portray his incarnations; those of a temple to Shiva , his various combative feats; and those of a temple to the Great Goddess, her battles with various demons. Regional variations exist, too; in the eastern state of Odisha, for example, the niches of a temple to Shiva customarily contain images of his family—his consort, Parvati, and their sons, Ganesha, the god of overcoming obstacles, and warlike Skanda.

The exterior of the halls and porch are also covered with figural sculpture. A series of niches highlight events from the mythology of the enshrined deity, and frequently a place is set aside for a variety of other gods. In addition, temple walls feature repeated banks of scroll-like foliage, images of women, and loving couples known as mithunas . Signifying growth, abundance, and prosperity, they were considered auspicious motifs.

Dehejia, Vidya. “Hinduism and Hindu Art.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hind/hd_hind.htm (February 2007)

Further Reading

Dehejia, Vidya. Indian Art . London: Phaidon, 1997.

Eck, Diana L. Darsan: Seeing the Divine Image in India. 2d ed . Chamberburg, Pa.: Anima Books, 1985.

Michell, George. The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms. Reprint . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Mitter, Partha. Indian Art . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Additional Essays by Vidya Dehejia

- Dehejia, Vidya. “ Buddhism and Buddhist Art .” (February 2007)

- Dehejia, Vidya. “ Recognizing the Gods .” (February 2007)

- Dehejia, Vidya. “ South Asian Art and Culture .” (February 2007)

Related Essays

- Nepalese Painting

- Nepalese Sculpture

- Recognizing the Gods

- South Asian Art and Culture

- The Art of the Mughals before 1600

- Buddhism and Buddhist Art

- Early Modernists and Indian Traditions

- Europe and the Age of Exploration

- Jain Sculpture

- Kings of Brightness in Japanese Esoteric Buddhist Art

- Life of Jesus of Nazareth

- Modern Art in India

- The Mon-Dvaravati Tradition of Early North-Central Thailand

- Musical Instruments of the Indian Subcontinent

- Poetic Allusions in the Rajput and Pahari Painting of India

- Postmodernism: Recent Developments in Art in India

- Pre-Angkor Traditions: The Mekong Delta and Peninsular Thailand

- The Rise of Modernity in South Asia

- The Year One

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of South Asia

- Central and North Asia, 500–1000 A.D.

- Himalayan Region, 1400–1600 A.D.

- South Asia, 1400–1600 A.D.

- South Asia, 1–500 A.D.

- South Asia: North, 1000–1400 A.D.

- South Asia: North, 500–1000 A.D.

- South Asia: South, 1000–1400 A.D.

- South Asia: South, 500–1000 A.D.

- Southeast Asia, 1000–1400 A.D.

- Southeast Asia, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Southeast Asia, 500–1000 A.D.

- 10th Century A.D.

- 11th Century A.D.

- 12th Century A.D.

- 13th Century A.D.

- 14th Century A.D.

- 15th Century A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- 17th Century A.D.

- 18th Century A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- 1st Century A.D.

- 20th Century A.D.

- 21st Century A.D.

- 2nd Century A.D.

- 3rd Century A.D.

- 4th Century A.D.

- 5th Century A.D.

- 6th Century A.D.

- 7th Century A.D.

- 8th Century A.D.

- 9th Century A.D.

- Architecture

- Central and North Asia

- Christianity

- Deity / Religious Figure

- Floral Motif

- Gilt Copper

- Literature / Poetry

- Plant Motif

- Relief Sculpture

- Religious Art

- Sculpture in the Round

- Southeast Asia

- Uttar Pradesh

1 Hinduism and Science

Sangeetha Menon is a Fellow in the School of Humanities at the National Institute of Advanced Studies in Bangalore.

- Published: 02 September 2009

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Hinduism represents the religion and philosophy that originated in India. It is the religion of 16 per cent of the world's population, and India is home to more than 90 per cent of the world's Hindus. Today many historians and philosophers of science have started reviewing the dynamic events and historical processes that led to what is called the European Enlightenment and modern science. This article focuses on how Hinduism as a religion has coexisted with scientific pursuits, the underpinnings of such partnerships, and the significant contributions of such dialogues to the current engagements between science and spirituality. The discussion follows how apparently different enterprises of experience and reporting of experience were given a common space, as well as what the areas of convergence are that Hinduism posits for dialogues between and within science and spirituality. The article particularly looks at the Vedantic (Upanishads) tradition.

Introduction

Hinduism represents the religion and philosophy that originated in India, and has a historical past covering the experiences of ‘thousands of different religious groups that have evolved in India since 1500 bce ’ ( Levinson 1998 ). It is the religion of 16 per cent of the world's population, and India is home to more than 90 per cent of the world's Hindus.

It would be incorrect to say that Hinduism is a monolithic religion, owing to its diverse theological traditions and its warm embrace of pluralistic thinking. However, the foundational textual sources can be traced to the corpus of Sruti, Smrti , and Darsana literature. This set consists of the Veda, Purana, Dharmasastra, and the six systems of Hindu philosophy. Vedas are collections of hymns and incantations often guiding worrisome thoughts about the origin of the world and natural forces to gods and goddesses. Purana forms the mythopoetic literature, and the Dharmasastras the code of ethics and moral laws for the individual and the society. Darsana forms systematic discussions on metaphysics, epistemology, and ways of living. To a contemporary Hindu the names of the Bhagavad gītā , Upanishads, and Puranas are significant sources for her thinking, believing, and understanding.

Today many historians and philosophers of science have started reviewing the dynamic events and historical processes that led to what is called the European Enlightenment and modern science. Monolithic and Eurocentric views about science are being challenged from the context of Eastern and Islamic contributions to world science. The role of China, India, and the Islamic culture in developing the bed for the origin of Western science is a theme being widely pursued. The discussion in this chapter does not trace these origins and theories. Rather, the focus will be on how Hinduism as a religion has coexisted with scientific pursuits, the underpinnings of such partnerships, and the significant contributions of such dialogues to the current engagements between science and spirituality.

The origins of Hinduism take us to a time when human experience and its possibilities were the central issues. Science, ethics, and laws were all in the context of the primary experiences of a culture and a society that saw subjectivity as an essential factor in creating objectivity. Knowledge and experience both contributed to humanization. We will see in the discussion to follow how apparently different enterprises of experience (in other words, culture) and reporting of experience (in other words, a systematic body of knowledge) were given a common space, as well as what are the areas of convergence that Hinduism posits for dialogues between and within science and spirituality. In this chapter, I will particularly look at the Vedantic (Upanishads) tradition.

Guidelines and Fundamentals

As one of the oldest religions, which originated thousands of years ago, and as a religion that has assimilated the changing urges and attitudes of the Indian mind, Hinduism represents primarily a pluralistic philosophy. The religion of Hinduism, however segregated its factions are, is founded on a tolerant philosophy that is ready to include and integrate. It is pertinent to look at the fundamental principles of Hinduism that guide the contemporary Hindu to practice her religion and also place her in a global context for engagements with issues concerning humankind in general.

The fundamentals employed are acceptance of diverse views in metaphysics, faith, and belief systems; the ideal of ahimsa —non‐violence; the ideal of satya —Truth; the emphasis on ways of living guided by reflection, detachment ( sakshibhava ), and meditation.

The pluralistic philosophy of Hinduism is founded on these fundamentals, which are also the bedrock for fresh and periodic additions of gods and practices to the religion. A striking feature that greets the eyes of a non‐Hindu traveller in India is the number and form of deities who become part of the religion and day‐to‐day life. A tree, a stone, or even an anthill could suddenly be elevated to a divine status enriching the lives of people. Hinduism best explained is a living and growing religion, with an ability to extend the dimension of the divine and integrate new forms of the divine without disturbing the order of the religious system. The fluid face and form of the Hindu god makes sure that there is more inclusion of ideas, practices, and beliefs into the system of a living religion—what might be called a theology with a systems approach that helps integrate knowledge processes with pluralistic coexistence.

Non‐violence

Tolerance and non‐violence are the basic identities of Hinduism. Ahimsa is non‐injury and non‐violent disagreement. The ideology behind ahimsa is ‘to agree to disagree’ and ‘respect for differences’. For a leader like Mahatma Gandhi, the concept of non‐violence proved to be not only a political tool but also a value that touched daily life. Such is the power of this value that Einstein wrote to Gandhiji: ‘You have shown through your works, that it is possible to succeed without violence even with those who have not discarded the method of violence. We may hope that your example will spread beyond the borders of your country, and will help to establish an international authority, respected by all, that will take decisions and replace war conflicts.’ 1

Gandhiji translated ahimsa into positive interpretations of equity and peaceful coexistence. The famous mantra that influenced Gandhiji in a significant manner says that ‘the whole world is pervaded by the divine; therefore take what you are given and never covet what belongs to another’ (Isavasya Upanishad, 1). The fact that ahimsa is one of the preconditions for a person aspiring to Yogic excellence tells us that Hinduism views non‐violence not merely as an ethical concept, but as a practice capable of leading to transformation and transcendence. India's freedom movement led by Mahatma Gandhi is a testimonial for this.

The ideal of ahimsa , which is hailed as the foundation of religion by Mahabharata , is considered the supreme virtue by Hindu teachings. In a religious and metaphysical environment of contending systems of thought and faith, Hinduism, which is virtually a confederation of faiths, had to develop rules of thumb to ensure peaceful and creative interaction between them. We could say that the concept of ahimsa thus originated as a response to the plurality of movements within Hinduism. Though ahimsa literally means non‐injury to living beings, it can be interpreted in different ways, as ‘respect for difference’, ‘coexistence’, ‘peaceful resolution of conflicts’, ‘multidimensional perspectives’, ‘learning from each others’ experiences', ‘humility’, or ‘ecological harmony of all life forms’. 2

The Fluid Face of Truth

The concept of Truth has implications for epistemic, ethical, metaphysical, and spiritual definitions in Hinduism. Satya is the pursuit of Truth as well as practising Truth in word and deed. The uncompromising connection between what is thought and practised makes Truth a hard value to live, a difficult epistemic concept to define, and an experiential ideal to fulfil. Isavasya Upanishad's mantra says that the ‘face of the Truth is concealed by a golden disc’ (mantra 14). Ramayana's theory is to ‘tell Truth, but say it in a manner that is helpful to others’. Mundaka Upanishad says ‘Truth alone prevails’— satyameva jayate —(3. 1. 6). If there is conflict between ideals of God and Truth, then it is Truth that a Hindu will choose.

In her search for Truth, the Hindu is ready to undergo self‐purification and transformation to refine her means of knowledge. Reason and experiments are therefore not the only valid means of knowing. Depending on the domain of study, reflection, inner transformation, and ontological insights also are means of knowledge. The intricate diagrams of altars in the Vedic literature, such as the symbolic representation of the bird with outspread wings in the Sulvasutra that represents the complex geometry of pre‐Euclidian times, indicate the perceptions of a culture that didn't view ‘doing science’ as a pure objective enterprise but as part of ritualistic experience. 3 The Truth that was pursued demanded a means that is a blend of personal and social engagement, ecological awareness, and advanced mathematics.

The Vedic people performed rituals to harness forces of nature in their favour to gain victory in battle, to receive timely rain, for healthy children, for more cattle, for a good harvest, and for a place in heaven after death. According to their world‐view the world was created by the sacrifice of gods, and gods subsisted by the sacrifice of humans, as described in the Purushasukta of Rig Veda . They developed mathematics, linguistics, astronomy, and metaphysics to aid their rituals, and conceived of a complex system known as the six limbs of Veda ( vedanga ), such as grammar ( vyakarana ), etymology ( nirukta ), manual of rituals ( kalpa ), prosody ( chandas ), and astronomy/astrology ( jyotisha ). For them, gods, nature, and humans formed a web of existence.

The One in the Many

The inclusive identity of Hindu religion is to be seen in the context of the rigour and clarity of its philosophy, exemplified by, for instance, the Jaina view of ‘many‐sided’ and the ‘perhaps’ view of the real, the Buddhist theory of dependent origination, the Upanishadic concept of two kinds of knowledge, and the Nyaya proposal of empirical criteria to serve as a test for truth, such as the concordance with observed data and affirmation by practical utility. Knowledge at no point can be seen as exclusive of its contextual, relative, and tentative nature. The pragmatic view of knowledge that Indian epistemologists developed coexists with their inclusive and tolerant views about ways of living. Adherence to laws of conduct and social rules ( dharma ), contributing and partaking from the collective memories ( smrti ) of the community, taking the lead to search for the ultimate reality and its identity with the self ( moksha )—for the Hindu, knowledge meant all this. On non‐verifiable transcendental issues Hinduism is open‐ended. On practical and ethical issues Hinduism encourages consensus building based on principles of honesty and non‐violence.

The famous Vedic statement, one of the foundational propositions of Hinduism, that says ‘truth is one but expounded in many ways by the wise’ ( Rig Veda: ekam sat vipra bahudha vadanti ), tries to relate Truth to reality, and the pursuit of Truth as the pursuit of the real. This dictum maintains a radical Hindu view that in essence existence is one, though the wise describe it differently. Swami Vivekananda, the representative of neo‐Hinduism, quoted another immortal verse to signify this idea in his speech in the Parliament of Religions held in 1893 in Chicago: ‘As the different streams having their sources in different places all mingle their water in the sea, so, O Lord, the different paths which men take through different tendencies, various though they appear, crooked or straight, all lead to Thee’ ( Swami Vivekananda 1991: 3 ).

The later Upanishads conceived of a world with two realities—the higher and the lower— para and apara , the world of the spirit and of matter. This division continued to exist, and got incorporated in metaphysical theories in the later Vedic and early Upanishadic thought of brahman and maya , purusha and prakrti , kshetrajna and kshetra , and prana and rayi . The later Upanishads and the Bhagavad gītā resolved this dichotomy by positing a higher reality, parabrahman or purushottama that transcends and includes the duality of matter and spirit, prakrti and purusha . The Vedantin perceives seer—seen duality as an expression of parabrahman , which is realized in the wake of enlightenment. Different Hindu schools, the Dvaita , Visish‐tadvaita , Yoga , Tantra , and Sakta , uphold the same idea, with slightly different metaphysics. The thread that runs through all forms of Hindu metaphysics and belief systems is the idea that God, ultimate reality, permeates all material manifestations, and hence that there is no fundamental antagonism between matter and spirit, world and God. Hindu enlightenment is seeing God in every bit of the world and experiencing the harmony of dualities.

In Hinduism and Indian philosophy, pluralism is not limited to the form and nature of the god of one's belief. The Hindu mind conceives pluralism as a method for thinking and experiencing the multidimensionality of reality. Indian epistemology and metaphysics are rich sources of the thinking—experiencing paradigm. Philosophy according to the Hindu view cannot be an alienated rational process, though much discussion goes into theories of knowledge. Why Hindu philosophy is primarily a wisdom tradition is explained by its idea of identity between knowledge and existence, cit and sat . Many dimensions of Truth, many ways of knowing it, and many modes of being it, are built into the Hindu psyche. Ethical priorities, logical efficacies, and metaphysical theories are all finally supposed to lead to a way of living, and transformation of attitudes, approaches, and experiences. Different sects of Hinduism more or less believe that the world is an extension of God, and hence worldly activity is not opposed to religious life. Faith is not opposed to reason, since they deal with different domains. Tools to realize the Truth can also be different, such as knowledge and devotion. At the same time, knowledge about God, self, and their relation ( jnana ) is complementary to one's practice of religion through love of God and humanity ( bhakti ). The striking feature of Hinduism as a religion is its ability to devise tools for coexistence and conflict resolution, to accommodate diverse views and practices, to see a joint enterprise between scientific thinking and spiritual living.

The four crossroads that lead to significant dialogues between Hinduism as a religion and current thinking in science are (i) the Hindu concept of knowledge and method, (ii) theories of causation, (iii) theories of consciousness, and (iv) conflict resolution. The crux of the science and spirituality dialogue seen from a Hindu perspective and the knowing—being nexus in Hinduism can both be explained with the help of these four points of intersection.

Beginnings of Knowledge and Method

Nature was the intimate setting for the Vedic people to do their ‘science’ and experiments in the wilderness. Knowledge, its origin and nature, dominates several discussions in the Upanishadic literature. This trend continues in the other schools of Hindu philosophy as well. But what unites the Vedic, Upanishadic, and classical schools of Indian thought in their concept of knowledge is that equal importance is given to a scientific pursuit of the knowledge of the ‘outer’ and ‘inner’ worlds. The outer and the inner are seen as twin realities of life, and progress for the Vedic people depended on how well they could include each other. On one side the Hindus presented pioneering findings in the Weld of physical sciences—the outer—such as astronomy, mathematics, chemistry, medicine, and metallurgy—and on the other they developed—the inner—a wisdom tradition. The Hindu ideals of love, compassion, and personal well‐being make avenues for ‘material’ developments to meet with ‘spiritual’ progress in a common space for optimal development of the person.

First Signs

The earliest signs of an inquiry to trace the ‘real’, or the basic stuff which things are made of, can be found in expressions like, ‘Who has seen that the boneless bears the bony when being born Wrst? Where may be the breath, the blood, the soul of the earth? Who would approach the wise to make this inquiry?’ ( Rig Veda , I. 164. 4). 4 This and similar verses indicate distinct metaphysical and epistemological routes to reality.

We could also Wnd an inquiry that leads to linguistic, psychological, and trans‐personal issues with certain finesse in some of the hymns. The Vedic concept of rta , close to the present‐day English word ‘rhythm’, is a result of the recognition of a comprehensive and unifying principle by the Vedic people. Vedic sages recognize rta as the rhythm behind the structuring of the dynamic aspects of the universe. In the later part of the Vedic literature ( Samhitas and Brahmanas ), the superior nature of mind in relation to speech is recognized. Further, Taittiriya Samhita recognizes the limitations of both speech and mind to define the first principle. It says, ‘Finite are the hymns, finite the chants, finite the ritual formulae, to what constitute Brahman however there is no end’ (vii. 3. 1. 4).

Bending Knowledge to Realism and Tentativeness

The Upanishadic theories of creation, the Jaina theory of multiple possibilities of existence, and the Nyaya theory of action fulfilment try to bend a structured concept of knowledge with realistic caution. Major schools of Hindu thinking deal extensively with the means ( pramaana ) of knowledge ( prama ) and validation ( praamaanya ). The concept of pramaana could initially be interpreted as a theory of knowledge, of ascertaining knowledge. But its function will not be completely understood without taking into consideration two characteristic features of knowledge as perceived by many of the classical schools of Indian thinking. These two characteristics abhadhitatva , of non‐contradiction, and anadhigatatva , of novelty, lay down the condition for validating knowledge ( Hiriyanna 1975 ). A knowledge statement is of questionable validation if there is another knowledge statement that contradicts the claim of the previous statement. Not being contradicted by another statement alone does not perform the role of validation. The characteristic of non-contradiction is also to be followed by the feature of novelty. Newness of knowledge is as important as non‐contradiction in the ascertaining of knowledge. The feature of ‘novelty’ implies once again the epistemological openness evident in Indian thought.

Beginning and End of Creation

The two creation myths in the Vedic literature are: (i) time‐space‐event creation is an illusory projection of the transcendental Truth, and (ii) the experience of the world as ‘other’ is the result of self‐ignorance. A significant hymn called Nasadiya Sukta says: ‘Verily, in the beginning this (universe) was, as it were. Neither non‐existent nor existent, in the beginning this (universe), indeed, as it were, existed and did not exist: there was then only that Mind’ ( Sathapatha Brahmana , x. 5. 3. 1).

This hymn tries to mark the boundaries of a conceptual categorization of creation in terms of cause and effect. It says that the wholeness which can only be pointed to as ‘That one’ is the ground of all existence— sat —and, by negation, non‐existence is given the designation— asat . In the first verse of Purusha Sukta , reality is depicted as the Virat Purusha , or Cosmic Person, pervading the whole universe but still beyond it.

The Upanishads do not speak of a unitary, divine principle that is opposed to the multiplicity of creation. The ‘transcendence’ that the Upanishads highlight does not signify an aloofness or exclusion. The Upanishadic ideas of immanence and transcendence, creation and creator, can be understood only in the context of theories of consciousness and self. The Rishis expound consciousness as the ultimate reality, and identify it with the Self. The Upanishadic Rishi considers any doctrine on creation or causality as a myth created to explain mystery. The captivating narratives, mostly based on ecopsychological principles, try to break the built‐in linearity in causality theories. Carl Sagan says:

The Hindu religion is the only one of the world's great faiths dedicated to the idea that the Cosmos itself undergoes an immense, indeed an infinite, number of deaths and rebirths. It is the only religion in which the time scales correspond to those of modern scientific cosmology. Its cycles run from our ordinary day and night to a day and night of Brahma, 8.64 billion years long. Longer than the age of the Earth or the Sun and about half the time since the Big Bang. And there are much longer time scales still.…The most elegant and sublime of these is a representation of the creation of the universe at the beginning of each cosmic cycle, a motif known as the cosmic dance of Lord Shiva. The God, called in this manifestation Nataraja, the Dance King. In the upper right hand is a drum whose sound is the sound of creation. In the upper left hand is a tongue of flame, a reminder that the universe, now newly created, with billions of years from now will be utterly destroyed. ( Sagan 1980: 32 )

From one angle of explanation—that is, the non‐existence of anything prior to creation—we find Upanishadic references like ‘There was nothing whatsoever here in the beginning’ ( Brhadaranyaka Upanishad , I. 2. 1); ‘Non‐existence verily was this (world) in the beginning’ ( Taittiriya Upanishad , II. 7. 1); ‘In the beginning this (world) was non‐existent’ ( Chandogya Upanishad , III. 19. 1). From another angle of explaining creation, Aitareya Upanishad speaks of the creator's entrance into the body by the opening in the skull— vidriti. Brhadaranyaka Upanishad adds that the creator entered up to the very tip of the nails. The purpose of this entry was ‘to become everything that there is’ and for ‘assigning names into the objects and the evolution of their functions’ (Chandogya Upanishad, VI. 2. 1). Taittiriya Upanishad says, ‘Having entered it, He became both the actual ( Sat ) and the beyond ( Tyat ), the defined and the undefined, both the founded and the non‐founded, the intelligent and the non‐intelligent, the real and the un‐true. As the real It became whatever there is here’ (II. 6. 1). The declaration of the student in Taittiriya Upanishad , ‘I am food and the eater of food, too’— aham annam …aham annaadah —indicates that the chain of existence is essentially cyclic.

From the Brahmanas to the Upanishads we find a cosmology that, with a more consistent analysis of creation, reaches a psychology identifying the First Principle with consciousness and the Self. Ranade says: ‘Existence is not existence, if it does not mean self‐consciousness. Reality is not reality if it does not express throughout its structure the marks of pure self‐consciousness. Self‐consciousness thus constitutes the ultimate category of existence to the Upanishadic philosophers’ ( Ranade 1926: 270 ). A. L. Basham says in his book The Wonder that was India : ‘The great and saving knowledge which the Upanishads claim to impart lies not in the mere recognition of the existence of Brahman, but in continual consciousness of it … Brahman is the human soul, is Atman, the Self’ ( Basham 1967: 252 ).

The later Hindu schools of philosophy approach the problem of causation, and creation in particular, in interestingly different ways, yet tied together by a common emphasis on the transformation of experience. The naturalistic tradition of Samkhya , the oldest Indian thought, is the basis for many developments in Hindu religion. This tradition avoids the problem of the independent existence of creator and creation by positing a somewhat complex existence of reality that has on the one side dynamic matter, and, on the other, passive spirit. For Samkhya , the universe owes its existence to the interaction of prakrti and purusha , the principles of materiality and consciousness. It is the presence of purusha that upsets the equilibrium of a yet unmanifest prakrti and kick‐starts the evolutionary process of the world. Samkhya recognizes the mutual association of consciousness and matter as essential for creation. It is said in Sarva‐siddhanta Samgraha that ‘Through the association (of prakrti ) with that ( atman ) possessed of consciousness there arises creation’ ( Sarva‐siddhanta Samgraha , X, 15–16). 5 Metaphorically illustrated, the ‘lame purusha cannot operate without the blind prakrti ’. ‘The association of the two, which is like that of a lame man and a blind woman, is for the purpose of Primal Nature being contemplated (as such) by the Spirit’ ( Samkhya Karika , 21). 6 To the question of how long creation subsists, Samkhya answers with the help of the famous analogy: When purusha has enjoyed all manifestations of prakrti, prakrti ceases to act. It is like ‘a dancer [who] desists from dancing, having exhibited herself to the audience’ ( Samkhya Karika , 59).

Consciousness Leading Back to Self

Hindu theories of creation and cosmology are founded on certain central ideas concerning the self and consciousness. Hindu ideas not only about mind and matter, but also about God, self, death, well‐being, and spiritual progress, bring a radically different perspective to the current discussions on consciousness.

A prominent contention in consciousness studies, which is popular as the NCC (neural correlate of consciousness), is that experience is much too complex to be comprehended by ‘building‐block’ approaches. It is possible that segregated explanations of specific sensory functions would give us path‐breaking knowledge about the working of some aspects of human mind and consciousness. But then, whether these explanations together will be sufficient to understand the intricacy and integral wholeness of human self and experience is a question that demands considerable attention. The ‘binding problem’ 7 of consciousness, which scholars are never tired of discussing, is not only the ‘puzzle of conscious experience’ ( Chalmers 1995 ) but also the most evasive problem of the subjective self, the ‘harder problem’ ( Menon 2001 ). The Hindu theories of consciousness focus on the subjective self.

Distinction between Mind and Consciousness

In the Aitareya Upanishad a distinction is drawn between consciousness as the real knower and mind as just another sense organ. The various functions that can be classified under the three categories of cognition, affection, and conation are enumerated. ‘Perception, discrimination, intelligence, wisdom, insight, steadfastness, thought, thoughtfulness, impulse, memory, purpose, life, desire, control’ (III. 1. 2) — all these are identified as the operative names of consciousness. A further point of psychological interest is the analysis of the cognitive act into the knower ( praajna ), the intellect ( prajna ), and cognition ( prajnana ).

Kena Upanishad starts with the psychological inquiry as to what must be regarded as behind the psychophysical functions: namely, thinking, breathing, speech, vision, and action. Why is it that the mind is able to think? Who regulates the vital breath? How is it that the mouth, eye, and ear enable one to speak, see, and hear? Are sense perceptions autonomous, or is there an entity that underlies them? To these queries, the Rishis reply that it is consciousness that underlies all the psychic functions. But sense organs or the mind cannot know it. Consciousness is beyond not only what is known, but also what is unknown. It is beyond the reach of knowledge as well as ignorance. ‘Upanishadic knowledge is renunciation of inferiority along with its vessel; it is transcendence of the very condition of inferiority’ ( Grinshpon 2003 ). Self‐knowledge is a key concept in the Upanishads. We find a frequently occurring refrain, ‘ yo evam veda ’—‘one who knows thus’. Upanishadic psychology presents the Self as the pure subject which never becomes an object.

A definition of consciousness is ‘that which reveals by itself through every act of cognition’— prati bodha viditam ( Kena Upanishad , II. 4). Consciousness is the innermost subject, which makes cognitions and experiences possible and hence by itself cannot be explained using these. Taittiriya Upanishad and Kena Upanishad say, ‘Whence words return along with the mind, not attaining it’ (ii. 4. 1); ‘There the eye cannot go, nor can speech reach’ (i. 3). Brhadaranyaka Upanishad says, ‘You cannot see the seer of seeing, you cannot hear the hearer of hearing, you cannot think of the thinker of thinking, you cannot understand one who understands understanding’ (iii. 4. 2). The Upanishads desist a categorical definition of consciousness. On this Upanishadic style, Deussen remarks: ‘The opposite predicates of nearness and distance, of repose and movement are ascribed to Brahman in such a manner that they mutually cancel one another and serve only to illustrate the impossibility of conceiving Brahman by means of empirical definitions’ ( Deussen 1906: 149 ).

The Inside World of Experiences

There are several verses in the Brahmanas that imply the quest for the source of knowledge and experience ( Menon 2002 a ). From the origins of Indian philosophy to the classical schools and the works of later savants, the focus in Indian philosophy and wisdom traditions has not been on outside diversity, which one then artificially works to bring into a unity. Rather, the goal has been to discover intuitively a unity and then work towards diversity. This is the case even if we consider the most realist schools.

Epistemological analysis, in Indian thought, is subservient to experiential paradigms. Indian schools of thought, in general, have one common thread—to relate to a larger, deeper, and holistic concept or entity called ‘self’. Whether it is for affirmation or denial, they expend considerable reflection and analysis in order to form a philosophy about ‘self’. Both analysis (which is a structured, ‘leading‐to‐the‐next‐step’ kind of hierarchical thinking) and experience (as a set of ‘given’ or self‐evident data) are used as epistemological tools in an integral manner to form distinct but interrelated ontologies. Metaphors and images are used as epistemological tools for creating transcendence in thinking, and thereby experiencing. The aim is not to arrive at structured and classified/listed knowledge of the ‘other’ object or phenomenon, but to gain understanding in relation to an abiding entity whether it be the inner self/no‐self/or outer matter.

Neuroscience, Meditation, and Spiritual Altruism

Recently the discussions on synaesthesia 8 and meditation have gained a renewed interest, and journals are devoting many pages to them. Ideas from the corpus of Hindu philosophical and psychological literature which led to ‘transcendental meditation’ and meditation research two decades ago are gaining centre stage today in the effort to understand the nature of synaesthesia and how much of synaesthetic experience can be simulated. Another area focuses on the current discussions on the role of altruism in sociobiology. The major discussions on altruism that we follow today (especially in the context of sociobiology) give exclusive attention to altruism as an act favouring evolutionary or social benefits. What is almost always neglected is the fact that altruism is a phenomenon exhibited by a self . It is important to understand what exactly constitutes the ‘self‐space’ that links the various levels of altruistic behaviour in order to know why altruism is discussed at all. We have at least three questions from the Hindu point of view: (i) Is there a rationale for altruistic expressions and behaviours? (ii) Is there an ‘emotionale’ for altruistic expressions and behaviours? And (iii), What drives altruistic perceptions and behaviours?

The methodological exclusivity granted to altruistic acts will not only land us in an artificial epistemology; it also supplies too limited a framework for one to identify qualitatively the advantages of altruism. To limit altruism to psychological hedonism is to blindfold oneself with respect to the complexity of this phenomenon. It is essential to look at the psychological process whereby we are able to go from a drive for our own pleasure to a belief that we will gain this pleasure by benefiting others ( Ablondi 1996 ). For, if all humans are naturally self‐preservationists, then each person's possibility for the fulfilment of his or her self‐interests is reduced by the very act of altruism. This could offer a response to Schlick, who said that the processes whereby the general welfare becomes a pleasant goal are ‘complicated … [and] take place chiefly in the absence of thinking’ ( Schlick 1939: 417, 424 ). Even from a utilitarian point of view, the only way to maximize the possibility for fulfilment of self‐interest is by being altruistic to another. The Hindu ideal of lokasamgraha —the uplifting of all—initiates such a meaning. In the famous dialogue between Maitreyi and her husband and Saint Yajnavalkya, Maitreyi asks ‘what is that is most endeared and for whom’? Yajnavalkya, connecting a bare nerve of individual survival to a larger concept of self‐identity, responds that ‘it is for oneself that everything becomes endearing’, 9 meaning that one cannot have purist theories of either self‐survival or Self‐survival. 10

Hindu ways of thinking and notions about self focus on altruism in the context of selflessness and self‐space . The reason I wish to qualify the nature of selflessness and self‐space defined by the Hindu psyche as spiritual altruism is essentially related to the emphasis on selflessness in Hinduism as a state of being . It is directly connected with the transformation of consciousness, but also influences compassion, empathy, and ideas of the social good.

Conflict Resolution

There are two major paradigms in Hindu ways of thinking, in spite of otherwise great differences among metaphysical and epistemological positions. These are (i) what we actually see and experience, which is constituted by the given and the immanent, and (ii) what we could see and experience, which is constituted by future possibilities and the transcendent ( Menon 2003 ). It is within these two paradigms that the elaborate and detailed discussion of fundamental experiences such as pain and pleasure, sorrow and happiness, selfishness and selflessness, freedom and bondage, the given and the possible, etc., takes place. Hinduism and its philosophy are an attempt to bridge these seemingly two contradicting paradigms, through an exploration of the self, based on systematic discussions of (i) theoretical, (ii) experiential, and (iii) transcendental issues.

In the history of humankind, and especially in the new century, the dominant forces that will lead and guide humanity will be the pursuit of knowledge and the need for the coexistence of all life forms. More than at any time in the past, religion and science will be the major collaborators as well as competitors in this common pursuit. The primary question will therefore be how to leverage each other's strengths and minimize weaknesses for the sake of humanity. The Hindu mind, which recognizes the given and the possible as two complementary paradigms for progress, can help to resolve the conflict by introducing a third powerful yet ‘unassuming’ force: that is, spiritual well‐being. What is central to the Hindu concept of such well‐being is its soul‐centredness and the ability to give up what will be proved to be detrimental and inadequate for healthy coexistence. The much misinterpreted Hindu concept of maya proposes a new avatar, so as to provide a sound metaphysical and phenom‐enological explanation for the passing and apparently real world. Maya has often been castigated as a pessimistic concept describing the spatio‐temporal world as worthless and illusory. The growing interest in the ideas of quantum entanglement and multiple possible worlds by quantum physicists might provide a welcome note for the dynamic and positive interpretations of maya, which hold that the world is ‘real while experiencing, but not independently’.

The junctions and meeting points of discussions on theoretical, experiential, and transcendental issues, I think, will be at centre stage for Hinduism in the emerging science and religion dialogues. The key Hindu pointers will include an emphasis on ethical and spiritual discipline as a prerequisite for deeper self‐knowledge and new experiences, a change in self‐knowledge which changes the understanding of the given, and a reorientation of experience in order to allow for new responses to emerging situations.

What distinguishes the Indian way of thinking from what we today call the Western way of thinking is the wholesome connection present in the Hindu world between theoretical, experiential, and transcendental issues. It is also this distinguishing feature of Indian thinking that is often dismissed as ‘mystic’ and ‘otherworldly’. The important point missed by such dismissals is that what interested Indian thinking and its guiding principle in the ancient past, classical period, and modern times, is not the linearity and immediate convenience that is provided by rigid, reductionistic structures of knowledge. Rather, Indian thinking has been characterized by an open‐endedness in which experience and reflection can together bring about a reorientation of how we construe our self‐identities, so that we can respond innovatively to changing situations. This has turned out to be a most difficult challenge for science in particular. Because of their implications for self‐identity, the new findings in the sciences of nanomaterials, string theory, stem cell research, brain studies, and evolutionary biology will face religious and cultural disapproval.

How to understand and reorient emerging human identity will rely, to a great extent, on the theories of well‐being and transformation of consciousness that we affirm and practise. The works of Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902) and Sri Aurobindo (1872–1950) reflect some of these concerns and offer plausible responses. Just as we have physical and moral laws, so there are spiritual laws as well. Swami Bodhananda enumerates seven Hindu spiritual laws, ‘in order to organize our lives for greater good and to achieve greater happiness’ ( 2004: p. xiii ). These laws deal with consciousness/ brahman , the world of experiences/ maya , individual identity/ dharma , individual responsibility/ karma , social interactions/ yajna , detached engagement/ yoga, and effortless work/ lila .

Guidelines for Discourse and Dialogue

Tarkasamgraha , a widely used premier on Indian logic and dialectics, talks about the fourfold preliminary ( anubandha catushtaya ), the set of requirements for a discourse that may bring about meaningful results. The fourfold preliminary for any discourse are elucidations of vishaya (the theme of the discourse), prayojana (its major goal), sambandha (the relation between the theme of the discourse and its goal), and adhikari (the qualified participant).

The practice of specifying the objective and subjective guidelines for a discourse is also found in the foundational texts of Vedanta and Mimamsa . The starting verse of the text specifies the nature of inquiry such as for brahman, dharma , etc. Specifying the defining characteristic of a discourse avoids any doubt that might later ensue about what it is that guides the discourse. The thematic specification of the discourse also helps the student to have a clear picture of what the discourse will not talk about and what themes are restricted. Even if the theme of the discourse is known prior to entering into the discourse, the discussion could at some point raise the question of teleology in the mind of the student. Hence the theme, as well as the purpose of a discussion on such a theme, is specified initially. Though it could be a meta‐question outside the scope of the discourse, it is essential also to anticipate at least to some extent the relationship between the discourse and the theme of the discourse itself. This would enable one to understand how far the treatise or discourse is representative of the theme.

The final and most important preliminary factor for any discourse is to specify who is qualified to enter that particular discourse. This is a major rule for meta‐discourse, which, I think, is almost forgotten in the current discussions of a complex theme like ‘consciousness’. The recognition of the aptitude of the person as playing a vital role in the success of discourse and understanding implies the ever‐present subjective factor involved in epistemological enterprises. It also implies that understanding is always finally related to the basic aptitude of the scientist or philosopher, which once again anticipates the essential relationship between epistemology and phenomenology, knowledge of something, and its experience. One instance of expounding the nature of adhikari can be seen in the primal text of Advaita, Tattvabodha , where Sankaracarya talks about the four qualifications required for a pursuit of self‐knowledge—‘ sadhana catushtaya ’. This includes a distinction between the ontologies of the real and the unreal, a detached view of worldly pleasures, practise of ethical and psychological discipline, and an intense yearning to know the beyond and to be it. These guidelines are expected to resolve competing interests and clarify foundational issues. Most importantly, they serve to achieve ‘transcendence in and while thinking’ ( Menon 2002 a : 26 ).

The foundational issues, crossing the rigidity of being theoretical, experiential, or transcendental, which are embedded in the Hindu religion and philosophy are (i) about human mind, consciousness, and experience, and (ii) about self‐identity. The guidelines for the exploration of these embedded issues are (i) abstraction: to identify the unitary in the discrete; (ii) placeability: to have an ontological meaning for any experience, its object, and its experiencer; (iii) practice: to have values and discipline as essential guidelines for self‐exploration. The role of Hinduism in fostering science and spirituality dialogues is to be placed in this context.

Saints, Science, and Spiritual Quest

The dawn of neo‐Hinduism, inspired by saints and social leaders of India like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Dayananda Saraswati, Swami Vivekananda, Mahatma Gandhi, Sri Aurobindo, Ramana Maharshi, and others has brought to light a uniting force of spiritual quest. Their teachings reiterated the connections between theories of creation, cosmology, and consciousness and theories of self, human identity, and spiritual well‐being.

The dominant thoughts and views of Hinduism as a religion and philosophy time and again imbibe the ideas and visions of its savants, who appear at different historical times as poets, spiritual gurus, political leaders, mystics, and so on. The influence of Rabindranath Tagore on Bengal renaissance, his dialogues with Einstein; dialogue between David Bohm and J. Krishnamurthy, and Ramana Maharshi and Paul Brunton, are some instances of this process. In contemporary times, Swami Sivananda, Swami Tapovan, Swami Chinmayananda, Swami Ranganathananda, Maharshi Mahesh Yogi, Swami Bodhananda, and others, are particularly significant in initiating and contributing to significant dialogues and exchanges between science and Hinduism. Their teachings and views demonstrate that spiritual exploration is the midway between science and religion, especially evidenced by the past and present of Hindu religion.

Self‐oriented thinking, nested narratives that complement rational processes by serving functions of complex explanations, the systems approach of Upanishadic Rishis and Hindu philosophers, and their tryst with temptations and death—all point to a dimension that could be metaphorically addressed as the ‘inner’. The ‘inner’ chooses to reveal best at the junction points of science and religion. Hindu philosophy identifies such meeting points as points of transcendence and inclusion. Hinduism as a living and growing religion is therefore based primarily on an active and positive interpretation of karma theory, of interpreting and integrating challenges of the present.

A great danger in the golden age of dialogues based on spiritual meeting points is the hasty and immature appropriations of different domains of which science and religion are both sometimes guilty. When religion tries to claim that the current trends, theories, and findings of science existed already in ancient thought, forgetting the historicity and cultural specificity of religion, the way is unfortunately paved for primitive competitions rather than for the healthy pursuit of knowledge. Likewise, when science tries to dispossess religion of its central role in defining new meanings for human identity and spiritual well‐being, it critically impinges on our ability to conceptualize the very meaning of existence and survival—that is, human imagination and the pursuit of something still beyond. To see, understand, experience, and be one with the beyond is what inspires the Hindu mind. The points of junction that Hinduism identifies for dialogues that lead to advancement in knowledge and well‐being are consciousness, agency, and self‐identity. Today these three domains are central to both science and spirituality, and each seeks points of convergence in order to contribute to the greater meaning and enrichment of survival and evolutionary advance. It is hoped that such a joint exploration will ensure human progress, healthy coexistence, and spiritual well‐being.

References and Suggested Reading

Ablondi, Fred ( 1996 ). ‘ Schlick, Altruism and Psychological Hedonism ’, Indian Philosophical Quarterly , 23/3–4: 417–24.

Google Scholar

Basham, A. L. ( 1967 ). The Wonder that was India . Calcutta: Rupa and Co.

Google Preview

Chalmers, D. (1995). ‘The Puzzle of Conscious Experience’, Scientific American , December 1995: 62–8; < http://consc.net/papers/puzzle.html >.

Deussen, Paul ( 1906 ). The Philosophy of the Upanishads , trans. A. S. Geden . Edinburgh: Morrison and Gibb Ltd.

Grinshpon, Yohanan ( 2003 ). Crisis and Knowledge: The Upanishadic Experience and Storytelling . Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Hiriyanna, M. ( 1975 ). Indian Conception of Values . Mysore: Kavyalaya Publishers.

Levinson, David ( 1998 ). Religion: A Cross‐Cultural Dictionary . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Menon, S. ( 2001 ). ‘ Towards a Sankarite Approach to Consciousness Studies: A Discussion in the Context of Recent Interdisciplinary Scientific Perspectives ’, Journal of Indian Council of Philosophical Research , 18/1: 90–117.

—— ( 2002 a ). Binding Experiences: Looking at the Contributions of Adi Sankaracarya, Tuncettu Ezuttacchan and Sri Narayana Guru in the Context of Recent Discussions on Consciousness Studies . Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Monograph published under the program Knowledge Dissemination Series.

—— ( 2002 b ). ‘ The Selfish Meme and the Selfless Atma ’, Sophia , 41/1(May): 83–8. 10.1007/BF02780405

—— ( 2003 ). ‘Binding Experiences for a First Person Approach: Looking at Indian Ways of Thinking ( darsana ) and Acting ( natya ) in the Context of Current Discussions on Consciousness’, in Chhanda Chakraborti , Manas K. Mandal , and Rimi B. Chatterjee (eds.), On Mind and Consciousness , Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study, and Kharagpur: Indian Institute of Technology, 90–117.

Muller, F. Max ( 1978 ) (ed.). Sacred Books of the East . Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

Narasimha, R. ( 2003 ). About the NIAS Emblem . Bangalore: National Institute of Advanced Studies.

Ranade, R. D. ( 1926 ). A Constructive Survey of Upanishadic Philosophy . Poona: Bilvakunja Publishing House.

Rangacarya, M. ( 1983 ) (trans.). The Sarva Siddhanta‐Sangraha of Samkaracharya . New Delhi: Ajay Book Service.

Sagan, Carl ( 1980 ). Cosmos . New York: Random House Inc.

Sastri, S. Kuppuswami ( 1932 ). A Primer of Indian Logic: According to Annambhatta's Tarka‐ samgraha . Mylapore: Madras Law Journal Press.

Sastri, S. S. Suryanarayana ( 1973 ) (ed. and trans.). The Sankhya Karika of Isvara Krsna , 2nd edn. Madras: University of Madras.

Schlick, Moritz ( 1939 ). Problems of Ethics , trans. David Ryan . New York: Prentice‐Hall.

Swami Bodhananda ( 2004 ). The Seven Hindu Spiritual Laws . Delhi: BlueJay Books.

Swami Vivekananda ( 1991 ). Chicago Addresses . Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama Calcutta.

See Einstein's letter to Gandhi, courtesy of Saraswati Albano‐Müller; < http://streams.gandhiserve.org/einstein.html >.

Swami Bodhananda in an email to this author, August 2005.

For more on the Sulvasutra see Narasimha (2003) .

Quotations from the Vedas and the Taittiriya Samhita are taken from Muller (1978) .

Quotations from the Sarva‐siddhanta Samgraha are taken from Rangacharya (1983).

Quotations from the Samkhya Karika are taken from Sastri (1973) .

‘Binding experiences’ are how physical, discrete, quantitative neural processes and functions give rise to experiences that are non‐physical, subjective, unitary, and qualitative.

Synaesthesia (also spelled synesthesia); from the Greek syn‐ ‘union’, and aesthesis , ‘sensation’, is the neurological mixing of the senses. A synaesthete may, for example, hear colours, see sounds, and taste tactile sensations. Although considered a symptom of autism, it is by no means exclusive to those with autism. Synaesthesia is a common effect of some hallucinogenic drugs such as LSD or mescaline. See < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synaesthesia > and the 2005 issue of Journal of Consciousness Studies (12/4–5).

See < http://www.swami-krishnananda.org/brdup/brhad_II-04.html > for the dialogue between Yajnavalkya and Maitreyi on the absolute Self.

self is a well‐defined and exclusive identity ( jiva ), and Self is a growing, inclusive identity ( atma ).

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Email Signup

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology

Primary tabs

- View (active tab)

- Order Outline

Header photo: People on the ghats at the holy river Ganges in Varanasi

- Overview Essay

- Bibliography

- Engaged Projects

- Sacred Texts

- Ecojustice Resources

Religious Studies and Theology: Hinduism Essay

Introduction, the fundamental teachings of hinduism, bhagavad-gita in a lyrical format, the power of god.

There are so many religions which are followed by numerous people all across the globe and it is considered by many who believe in god that god is present everywhere which means there is omnipotence with regard to the presence of God. Many religions teach the followers that god is present everywhere that’s what omnipotent means, one such religion is Hinduism and this paper will present a good understanding of Hinduism in a Sympathetic way.

One of the most widely spread religions is Hinduism, those who follow Hinduism are called the Hindus. There are many deities followed by the Hindus. “The underlying tenets of Hinduism cannot be easily defined. Unlike other religions, Hindu Dharma did not originate from a single person, a single book, or at a single point in time. The foundations of this oldest surviving religion were laid by ancient rishis (sages), who taught their disciples the eternal principles of life they had discovered through their meditations. Hindu Dharma is essentially a religion of principles rather than persons. Since Hinduism has no founder, anyone who practices Dharma can call himself a Hindu. Statistically, there are over 700 million Hindus, concentrated mainly in India and Nepal.” (1) (Hinduism, 2009).

The religion like any other religion focuses upon the reality and aims at telling the people about good deeds. The religion tells that people about the importance of good deeds and the connection of the same with Moksha (Salvation).

The more a person does good deeds better are his/her chances to get Moksha. The religion places emphasis upon the importance of truth, like any other religion the main aim of Hinduism is to make the people aware of the supreme power and considering the same the people under this religion are advised to keep a good check on their actions.

“Hindu scriptures teach that an individual is essentially atman clothed in a physical body. The Sanskrit word atman, meaning “God within,” is usually translated as soul, self or spirit. In a human body atman is the source of the mind, intellect and ego sense. Hindu scriptures declare that atman is immortal and divine. In Hindu view, therefore, an individual is potentially divine and eternally perfect. There are two states of existence associated with atman, the bound state and the liberated state. In the bound state, atman is associated with a physical body. As a result of this association, atman is subject to Maya, which causes it to forget its true divine nature and commit evil deeds in the world. In the liberated state, atman is said to have attained moksha (spiritual perfection) and consequently enjoys union with God.” (2) (Hinduism, 2009).

The religion is the third largest religion across the globe only to be behind the likes of Christianity and Islam. This religion is followed extensively in the Asian Continent and India in particular is very popular when this religion is talked about. “Hinduism’s vast body of scriptures are divided into Śruti (“revealed”) and Smriti (“remembered”). These scriptures discuss theology , philosophy and mythology , and provide information on the practice of dharma (religious living). Among these texts, the Vedas and the Upanishads are the foremost in authority, importance and antiquity. Other major scriptures include the Tantras , the Agama , the Purāṇas and the epics Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa . The Bhagavad Gītā , a treatise from the Mahābhārata, spoken by Krishna , is sometimes called a summary of the spiritual teachings of the Vedas.” (3) (Chidbhavananda , 2009).