thesis (n.)

late 14c., "unaccented syllable or note, a lowering of the voice in music," from Latin thesis "unaccented syllable in poetry," later (and more correctly) "stressed part of a metrical foot," from Greek thesis "a proposition," also "downbeat" (in music), originally "a setting down, a placing, an arranging; position, situation" (from reduplicated form of PIE root *dhe- "to set, put").

The sense in logic of "a formulation in advance of a proposition to be proved or debated" is attested by 1570s (contrasted to hypothesis ; in rhetoric it is opposed to antithesis ); that of "dissertation presented by a candidate for a university degree" is from 1650s. The uncertainty of the prosodic sense might have kept it from being established in English. Related: Thetic ; thetical ; thetically .

Entries linking to thesis

*dhē- , Proto-Indo-European root meaning "to set, put."

It forms all or part of: abdomen ; abscond ; affair ; affect (v.1) "make a mental impression on;" affect (v.2) "make a pretense of;" affection ; amplify ; anathema ; antithesis ; apothecary ; artifact ; artifice ; beatific ; benefice ; beneficence ; beneficial ; benefit ; bibliothec ; bodega ; boutique ; certify ; chafe ; chauffeur ; comfit ; condiment ; confection ; confetti ; counterfeit ; deed ; deem ; deface ; defeasance ; defeat ; defect ; deficient ; difficulty ; dignify ; discomfit ; do (v.); doom ; -dom ; duma ; edifice ; edify ; efface ; effect ; efficacious ; efficient ; epithet ; facade ; face ; facet ; facial ; -facient ; facile ; facilitate ; facsimile ; fact ; faction (n.1) "political party;" -faction ; factitious ; factitive ; factor ; factory ; factotum ; faculty ; fashion ; feasible ; feat ; feature ; feckless ; fetish ; -fic ; fordo ; forfeit ; -fy ; gratify ; hacienda ; hypothecate ; hypothesis ; incondite ; indeed ; infect ; justify ; malefactor ; malfeasance ; manufacture ; metathesis ; misfeasance ; modify ; mollify ; multifarious ; notify ; nullify ; office ; officinal ; omnifarious ; orifice ; parenthesis ; perfect ; petrify ; pluperfect ; pontifex ; prefect ; prima facie ; proficient ; profit ; prosthesis ; prothesis ; purdah ; putrefy ; qualify ; rarefy ; recondite ; rectify ; refectory ; sacrifice ; salmagundi ; samadhi ; satisfy ; sconce ; suffice ; sufficient ; surface ; surfeit ; synthesis ; tay ; ticking (n.); theco- ; thematic ; theme ; thesis ; verify .

It is the hypothetical source of/evidence for its existence is provided by: Sanskrit dadhati "puts, places;" Avestan dadaiti "he puts;" Old Persian ada "he made;" Hittite dai- "to place;" Greek tithenai "to put, set, place;" Latin facere "to make, do; perform; bring about;" Lithuanian dėti "to put;" Polish dziać się "to be happening;" Russian delat' "to do;" Old High German tuon , German tun , Old English don "to do."

Trends of thesis

More to explore, share thesis.

updated on March 20, 2024

Trending words

- 3 . spinster

- 9 . pumpkin

- 10 . sandwich

Dictionary entries near thesis

- English (English)

- 简体中文 (Chinese)

- Deutsch (German)

- Español (Spanish)

- Français (French)

- Italiano (Italian)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- Português (Portuguese)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese)

thesis etymology

The word "thesis" comes from the Ancient Greek word "τίθημι" (tithēmi) , meaning "to put, place, set".

A thesis is a formal written argument presented by a student or researcher to fulfill the requirements of an academic degree. It typically involves original research and analysis on a specific topic.

The concept of the thesis as a formal academic document developed over many centuries.

- Ancient Greece: Philosophers and scholars used the term "thesis" to refer to a proposition or argument that was put forward for discussion and debate.

- Middle Ages: In medieval universities, a thesis was a written summary of a student's studies that they had to defend in a public disputation.

- Renaissance: The rise of humanism and the printing press led to the development of more structured and formal theses.

- 18th Century: The modern concept of the thesis as an original research project emerged during the Enlightenment period.

- 19th Century: The university reform movement in Europe and North America established the thesis as a mandatory requirement for higher degrees.

Key Points:

- The Greek origin of the word "thesis" emphasizes its connection to proposing and arguing a point.

- A thesis is not simply a summary of existing knowledge but a unique contribution based on original research.

- The process of writing a thesis involves critical thinking, analysis, and the ability to communicate complex ideas effectively.

Words and phrases

Personal account.

- Access or purchase personal subscriptions

- Get our newsletter

- Save searches

- Set display preferences

Institutional access

Sign in with library card

Sign in with username / password

Recommend to your librarian

Institutional account management

Sign in as administrator on Oxford Academic

thesis noun

- Hide all quotations

What does the noun thesis mean?

There are seven meanings listed in OED's entry for the noun thesis . See ‘Meaning & use’ for definitions, usage, and quotation evidence.

thesis has developed meanings and uses in subjects including

Entry status

OED is undergoing a continuous programme of revision to modernize and improve definitions. This entry has not yet been fully revised.

How common is the noun thesis ?

How is the noun thesis pronounced, british english, u.s. english, where does the noun thesis come from.

Earliest known use

Middle English

The earliest known use of the noun thesis is in the Middle English period (1150—1500).

OED's earliest evidence for thesis is from before 1398, in a translation by John Trevisa, translator.

thesis is a borrowing from Greek .

Etymons: Greek θέσις .

Nearby entries

- thesaurus, n. 1823–

- thesaury, n. a1639–1708

- these, n. a1600–48

- these, pron. & adj. Old English–

- Thesean, adj. 1815–

- Theseid, n. 1725–

- Theseium, n. 1819–

- these-like, adj. 1644–

- thesial, adj. 1654

- thesicle, n. 1863–

- thesis, n. a1398–

- thesis-novel, n. 1934–

- thesis-play, n. 1902–

- thesmophilist, n. 1644–

- Thesmophorian, adj. 1891–

- Thesmophoric, adj. 1788–

- thesmothete, n. 1603–

- thesocyte, n. 1887–

- thesp, n. 1962–

- Thespian, adj. & n. 1675–

- Thespianism, n. 1914–

Thank you for visiting Oxford English Dictionary

To continue reading, please sign in below or purchase a subscription. After purchasing, please sign in below to access the content.

Meaning & use

Pronunciation, compounds & derived words, entry history for thesis, n..

thesis, n. was first published in 1912; not yet revised.

thesis, n. was last modified in June 2024.

Revision of the OED is a long-term project. Entries in oed.com which have not been revised may include:

- corrections and revisions to definitions, pronunciation, etymology, headwords, variant spellings, quotations, and dates;

- new senses, phrases, and quotations which have been added in subsequent print and online updates.

Revisions and additions of this kind were last incorporated into thesis, n. in June 2024.

Earlier versions of this entry were published in:

OED First Edition (1912)

- Find out more

OED Second Edition (1989)

- View thesis in OED Second Edition

Please submit your feedback for thesis, n.

Please include your email address if you are happy to be contacted about your feedback. OUP will not use this email address for any other purpose.

Citation details

Factsheet for thesis, n., browse entry.

- 1.1 Etymology

- 1.2 Pronunciation

- 1.3.1 Inflection

- 1.3.2 Derived terms

- 1.3.3 Descendants

- 1.4 References

- 1.5 Further reading

Ancient Greek

From τίθημι ( títhēmi , “ I put, place ” ) + -σις ( -sis ) , although it could either have been formed in Greek or go back earlier. In the latter case, would be from a Proto-Indo-European *dʰéh₁tis , from *dʰeh₁- (root of τίθημι ( títhēmi ) ). Cognates include Sanskrit अपिहिति ( ápihiti ) , Avestan 𐬀𐬭𐬋𐬌𐬛𐬍𐬙𐬌 ( arōidīti ) , Latin conditiō , and Gothic 𐌲𐌰𐌳𐌴𐌸𐍃 ( gadēþs ) . More at deed . [ 1 ]

Pronunciation

- IPA ( key ) : /tʰé.sis/ → /ˈθe.sis/ → /ˈθe.sis/

- ( 5 th BCE Attic ) IPA ( key ) : /tʰé.sis/

- ( 1 st CE Egyptian ) IPA ( key ) : /ˈtʰe.sis/

- ( 4 th CE Koine ) IPA ( key ) : /ˈθe.sis/

- ( 10 th CE Byzantine ) IPA ( key ) : /ˈθe.sis/

- ( 15 th CE Constantinopolitan ) IPA ( key ) : /ˈθe.sis/

θέσῐς • ( thésis ) f ( genitive θέσεως ) ; third declension

- a setting , placement , arrangement

- adoption (of a child)

- adoption (in the more general sense of accepting as one's own)

- ( philosophy ) position , conclusion , thesis

- ( dance ) putting down the foot

- ( metre ) the last half of the foot

- ( rhetoric ) affirmation

- ( grammar ) stop

Derived terms

- ἀνάθεσις ( anáthesis )

- ἀντένθεσις ( anténthesis )

- ἀντεπίθεσις ( antepíthesis )

- ἀντίθεσις ( antíthesis )

- ἀντιμετάθεσις ( antimetáthesis )

- ἀντιπαράθεσις ( antiparáthesis )

- ἀπόθεσις ( apóthesis )

- διάθεσις ( diáthesis )

- εἴσθεσις ( eísthesis )

- ἔκθεσις ( ékthesis )

- ἐναπόθεσις ( enapóthesis )

- ἔνθεσις ( énthesis )

- ἐπείσθεσις ( epeísthesis )

- ἐπέκθεσις ( epékthesis )

- ἐπένθεσις ( epénthesis )

- ἐπίθεσις ( epíthesis )

- ἐπιπρόσθεσις ( epiprósthesis )

- ἐπισύνθεσις ( episúnthesis )

- ἡμισύνθεσις ( hēmisúnthesis )

- κατάθεσις ( katáthesis )

- μετάθεσις ( metáthesis )

- παράθεσις ( paráthesis )

- παρέκθεσις ( parékthesis )

- παρένθεσις ( parénthesis )

- περίθεσις ( períthesis )

- προδιάθεσις ( prodiáthesis )

- προέκθεσις ( proékthesis )

- πρόθεσις ( próthesis )

- πρόσθεσις ( prósthesis )

- συγκατάθεσις ( sunkatáthesis )

- συναντίθεσις ( sunantíthesis )

- συνεπίθεσις ( sunepíthesis )

- σύνθεσις ( súnthesis )

- ὑπέκθεσις ( hupékthesis )

- ὑπέρθεσις ( hupérthesis )

- ὑπόθεσις ( hupóthesis )

Descendants

- ^ Beekes, Robert S. P. ( 2010 ) “ θέσις ”, in Etymological Dictionary of Greek (Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series; 10 ), with the assistance of Lucien van Beek, Leiden, Boston: Brill, →ISBN , page 543

Further reading

- “ θέσις ”, in Liddell & Scott ( 1940 ) A Greek–English Lexicon , Oxford: Clarendon Press

- “ θέσις ”, in Liddell & Scott ( 1889 ) An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon , New York: Harper & Brothers

- θέσις in Bailly, Anatole ( 1935 ) Le Grand Bailly: Dictionnaire grec-français , Paris: Hachette

- Bauer, Walter et al. ( 2001 ) A Greek–English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature , Third edition, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- “ θέσις ”, in Slater, William J. ( 1969 ) Lexicon to Pindar , Berlin: Walter de Gruyter

- θέσις in Trapp, Erich, et al. ( 1994–2007 ) Lexikon zur byzantinischen Gräzität besonders des 9.-12. Jahrhunderts [ the Lexicon of Byzantine Hellenism, Particularly the 9th–12th Centuries ], Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften

- assumption idem, page 48.

- caution idem, page 119.

- deposit idem, page 212.

- earnest idem, page 259.

- hypothesis idem, page 412.

- place idem, page 616.

- position idem, page 628.

- site idem, page 779.

- situation idem, page 780.

- station idem, page 813.

- supposition idem, page 842.

- thesis idem, page 865.

- Ancient Greek terms derived from Proto-Indo-European

- Ancient Greek terms derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *dʰeh₁-

- Ancient Greek terms suffixed with -σις

- Ancient Greek terms inherited from Proto-Indo-European

- Ancient Greek 2-syllable words

- Ancient Greek terms with IPA pronunciation

- Ancient Greek lemmas

- Ancient Greek nouns

- Ancient Greek paroxytone terms

- Ancient Greek feminine nouns

- Ancient Greek third-declension nouns

- Ancient Greek feminine nouns in the third declension

- grc:Philosophy

- grc:Rhetoric

- grc:Grammar

- Sanskrit terms with non-redundant manual transliterations

- Avestan terms with redundant transliterations

- Pages with entries

- Pages with 1 entry

Navigation menu

BEST SELLER

✔ Add 3,700 must-know words to your vocabulary.

✔ All-in-one: dictionary, thesaurus, & workbook.

✔ 632 pages, 147 lessons, 428 practical activities.

✔ Suitable for students & professionals of all ages.

✔ Ideal preparation for: TOEFL, TOEIC, IELTS, SAT, ACT, GRE, GMAT, CPE, BEC, PTE, FCE

Amazon Best Seller:

#1 Spelling & Vocabulary.

#1 Education TOEFL & TOEIC.

#1 Slang & Idiom Reference Books.

Build a Better Vocabulary Today!

Dictionary definition of thesis

A statement or theory that is put forward as a premise to be maintained or proved. "The thesis was published in an academic journal and received widespread recognition."

Detailed meaning of thesis

The thesis is typically a central idea or argument that is developed and presented in a written work, such as a dissertation or research paper. In higher education, a thesis is often a requirement for a graduate degree, such as a Master's or a PhD. The thesis is usually written under the supervision of a thesis advisor or mentor, and it presents original research or an original interpretation of existing research on a specific topic. The main purpose of a thesis is to contribute new knowledge and understanding to the field of study. It must be based on a rigorous research, the results must be presented in a logical and coherent manner and it must be written in a scholarly manner. Additionally, the thesis should demonstrate the student's ability to conduct independent research, to critically evaluate the existing literature, and to communicate their ideas effectively.

Example sentences containing thesis

1. Her thesis on renewable energy proposed innovative solutions for sustainability. 2. The professor praised the clarity of his student's thesis on social inequality. 3. The thesis of his argument was that technology enhances human communication. 4. The thesis of the book challenged conventional wisdom on economic policy. 5. Grad students often spend years researching and writing their theses. 6. The thesis behind the research project aimed to address pressing health issues.

History and etymology of thesis

The noun ' thesis ' has its etymological roots in ancient Greek. It is derived from the Greek word 'θέσις' (thésis), which means 'a setting down' or 'a position.' In the context of ancient Greece, ' thesis ' was used to refer to a proposition or statement that was put forward as the basis of an argument or discussion. It represented a foundational idea or premise that was to be maintained or proved through reasoning and evidence. As the term entered the English language, it retained this fundamental sense and is now commonly used to describe a statement or theory that serves as the central point of an argument or research project. It embodies the concept of a position or assertion that is presented for examination and verification. Therefore, the etymology of ' thesis ' underscores its use as a noun to denote a statement or theory set forth as a premise to be upheld or substantiated.

Quiz: Find the meaning of the noun thesis :

Continue Quiz

Further usage examples of thesis

1. She defended her thesis before a panel of expert examiners. 2. The conference featured presentations on a wide range of academic theses. 3. His groundbreaking thesis reshaped the field of quantum physics. 4. The thesis statement should encapsulate the main argument of your essay. 5. The thesis explored the intersection of art, culture, and identity in society. 6. The professor praised the student's thesis for its originality and depth. 7. His thesis explored the intersection of psychology and literature. 8. The defense of her thesis was a nerve-wracking but rewarding experience. 9. The thesis statement succinctly summarized the main argument of the paper. 10. The committee members engaged in a lively debate about the merits of the thesis . 11. The thesis proposed a new framework for understanding economic inequality. 12. After hours of editing, her thesis was finally ready for submission. 13. The library had an extensive collection of theses from various academic fields. 14. He was awarded a scholarship for his outstanding thesis on urban planning. 15. The thesis challenged existing theories and presented a fresh perspective. 16. The thesis project required extensive fieldwork and data analysis. 17. Her thesis was published in a reputable journal, gaining widespread recognition. 18. The thesis defense was attended by faculty members, peers, and family. 19. The thesis examined the historical context of the Renaissance art movement. 20. The graduate student presented her thesis findings at an international conference. 21. The thesis highlighted the need for further research in the field of genetics. 22. The thesis concluded with a call to action for policy changes in healthcare. 23. The advisor provided valuable guidance throughout the thesis writing process. 24. The thesis was a culmination of years of research and academic dedication.

https://static.wixstatic.com/media/eb68db_c76b20eee4f544739692acee8c95f51e~mv2.jpg, https://static.wixstatic.com/media/eb68db_14656208e4464bb1a273d7ac7b8c2c94~mv2.jpg, https://static.wixstatic.com/media/eb68db_c3952e52756542aa8faaaa2b25f9be00~mv2.jpg, https://static.wixstatic.com/media/eb68db_d757bc63d7994d5a85f0a9fb1a72ce57~mv2.jpg, https://static.wixstatic.com/media/eb68db_2cfea7e709504d5c8f6e4f13a02e7288~mv2.jpg, https://static.wixstatic.com/media/eb68db_8d472ca04c55431b968d52a6a249030a~mv2.jpg

Advancement and Improvement, Analytical and Interpretive, Nuance and Precision, Resilience and Resolve, Endeavor and Pursuit, Education and Mastery

argument,assertion,hypothesis,postulate,proposition,supposition

idea,proposal,subject

Synonyms for thesis

Quiz categories containing thesis.

Find the Synonym

Find the Antonym

Same or Different?

Spelling Bee

proposition, fact, certainty, proof

eb68db_25c2c7b47f1e4d05beafaf715574acce.mp3

- Dictionary entries

- Quote, rate & share

- Meaning of θέσις

θέσις ( Ancient Greek)

Origin & history.

- a setting , placement , arrangement

- adoption (of a child)

- adoption (in the more general sense of accepting as one's own)

- ( philosophy ) position , conclusion , thesis

- ( dancing ) putting down the foot

- ( metre ) the last half of the foot

- ( rhetoric ) affirmation

- ( grammar ) stop

▾ Derived words & phrases

- ἀντεπίθεσις

- ἀντιμετάθεσις

- ἀντιπαράθεσις

- ἐπιπρόσθεσις

- ἐπισύνθεσις

- ἡμισύνθεσις

- προδιάθεσις

- συγκατάθεσις

- συναντίθεσις

- συνεπίθεσις

▾ Descendants

- Latin: thesis

▾ Dictionary entries

Entries where "θέσις" occurs:

thesis : thesis (English) Origin & history From Latin thesis, from Ancient Greek θέσις ("a proposition, a statement, a thing laid down, thesis in rhetoric, thesis in prosody") Pronunciation IPA: /ˈθiːsɪs/ Pronunciation example: Audio (US) Rhymes:…

deed : …action"), Swedish and Danish dåd ("act, action"). The Proto-Indo-European root is also the source of Ancient Greek θέσις ("setting, arrangement"). Related to do. Pronunciation IPA: /diːd/ Pronunciation example: Audio (US) Rhymes:…

tes : …Origin & history I Noun tes Indefinite genitive singular of te Origin & history II From Latin thesis and Ancient Greek θέσις ("a proposition, a statement"), used in Swedish since 1664. Noun tes (common gender) a thesis, a statement…

Tat : …Low German Daat, Dutch daad, English deed, Danish dåd, Gothic 𐌳𐌴𐌸𐍃, and Ancient Greek θέσις ("arrangement"). Pronunciation IPA: /taːt/ Rhymes: -aːt Homophones: tat Noun Tat (fem.) (genitive Tat…

antithesis : antithesis (English) Origin & history From Ancient Greek ἀντί ("against") + θέσις ("position"). Surface analysis anti- + thesis. Pronunciation (Amer. Eng.) IPA: /ænˈtɪ.θə.sɪs/ Pronunciation example: Audio (US) Examples:…

Quote, Rate & Share

Cite this page : "θέσις" – WordSense Online Dictionary (26th October, 2024) URL: https://www.wordsense.eu/θέσις/

There are no notes for this entry.

▾ Next

θέσκελος (Ancient Greek)

θές (Ancient Greek)

θέτης (Ancient Greek)

θέτο (Ancient Greek)

θέτω (Greek)

θέω (Ancient Greek)

θέων (Ancient Greek)

▾ About WordSense

▾ references.

The references include Wikipedia, Cambridge Dictionary Online and others. Details can be found in the individual articles.

▾ License

▾ latest.

saltatio , waying , pravoslavac , salvamento

- Advanced Skills

- Roots & Affixes

- Grammar Review

- Verb Tenses

- Common Idioms

- Learning English Plan

- Pronunciation

- TOEFL & IELTS Vocab.

- Vocab. Games

- Grammar Practice

- Comprehension & Fluency Practice

- Suggested Reading

- Lessons & Courses

- Lesson Plans & Ideas

- ESL Worksheets+

- What's New?

Greek Roots

Many Greek roots have entered English, both directly (especially in medical and scientific vocabulary) and by way of Latin. Recognizing a few of their common bases (combined with a few prefixes) will increase your reading comprehension. Besides, they’re fun!

A large percentage of English words for math, sciences and social sciences (as well as music and other performance arts) come originally from Greek.

There's a list of some very common Greek roots below, followed by more individual words with Greek origins,

Common Greek Roots for English Words

Here’s a list of some of the most common Greek roots, in their usual combining form. (Most end in ‘o.’ You just drop the ‘o’ if the following syllable begins in a vowel.)

- anthropo- man, human : anthropology, anthropomorphic, philanthropy

- bio- life : antibiotic, biology, biosphere, probiotic, symbiosis

- chrono- time : chronic, chronology, chronometer

- cris, crit- judge or decide : crisis, criteria (standards to use to judge something), critical, hypocrisy

- geo- earth : geologist, geometry, geographic

- graph (from graphein - to write or draw, & graphia - a description of) : calligraphy, demographic, digraph, graph, (a chart showing information in the form of a picture), graphic, photograph

- hydro- water: dehydrate, hydraulic, hydroelectric, hydrogen, hydrophobia, hydrothermal

- logo- (often logy- study of, from logia - a speaking about, logos - word or thought) : biological, cardiology, dermatologist, ecology, ideology, logic, mythology, psychological, theological

- lexis- word: lexical, lexicography (dictionary writing)

- metron- measure : metric, speedometer, thermometer

- morpho- form or shape : metamorphosis, morphology

- patho- feeling , suffering, disease : antipathy, apathetic, empathy, pathogen, pathological, sympathetic

- philo- love (of) : philanthropy, philosophical, technophile

- phobia- fear : agoraphobia, hydrophobia, technophobia

- phone- sound : phonics, phonological, phonograph, symphony, telephone

- photo- light : photography, photosynthesis

- polis- city : metropolis, policy, political, politician

- psych- (via Latin)-soul, mind : psychiatrist, psychic, psychology

- scope- to look at : microscopic, scope (now the breadth and size of a project or vision, enough space to work), stethoscope, telescope

- sphere- ball : atmosphere, hemisphere, sphere, spherical

- techno- art, skill : technique, technology

- tele- far : telegram, telegraph, telephoto, telescope

- thermo- hot : thermal, thermodynamic, thermostat

- thesis (plural theses) - a proposition (idea proposed for debate) : antithesis, hypothesis, synthesis, thesis

More English Words from Greek Roots

Here are some more English words and their relatives that came from Greek (often via Latin):

- chorus (& choir)

Practice with Greek Roots

Two Greek suffixes and a few prefixes that you might need:

- -ic, -al = pertaining to, related to;

- a- = without,

- anti- = against,

- hemi- = half,

- hypo- = under,

- sym- or syn- = with

Instructions : Choose the best answer to each question, then press the right arrow to move to the next question.

Show all questions

- ? apathy

- ? antipathy

- ? empathy

- ? sympathy

- ? calligraphy

- ? criteria

- ? hypotheses

- ? techniques

- ? writes well

- ? feels deeply

- ? thinks clearly

- ? studies the mind intensely

- ? north of Europe in geography books

- ? a geographic line on the globe

- ? the northern half of the earth

- ? the Americas

- ? antithesis

- ? logic

- ? synthetic

- ? thesis

- ? chronometer

- ? stethoscope

- ? thermometer

- ? thermostat

- ? pathetic

- ? pathologist

- ? psychiatrist

- ? psychologist

- ? fears technology

- ? studies technology

- ? loves technology

- ? works with technology

- ? the study of money

- ? the love of philosophy

- ? the love of mankind

- ? the study of mankind

- ? the whole living world

- ? a representation of life together with death

- ? anything that works against life

- ? two forms of life working together for mutual benefit

Practice these Greek roots more with the Greek and Latin Roots Quiz .

Related Root & Prefix Pages

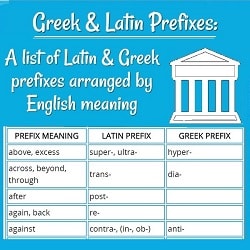

This is a useful list of the English meanings and then the Latin prefixes and Greek prefixes that mean the same thing.

Find the pages to study or practice over 100 root words on EnglishHints. This reference table gives meanings, examples, & links.

You know words made from these roots. Learn the Latin word roots themselves for a big boost in vocabulary!

See also Medical Prefixes , Medical Suffixes , (both almost all from Greek) & Medical Vocabulary .

Still want more? For stories about unexpected words that come from Greek (as well as some from above), see this article from Babble .

Home > Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes > Greek Roots.

Didn't find what you needed? Explain what you want in the search box below. (For example, cognates, past tense practice, or 'get along with.') Click to see the related pages on EnglishHints.

New! Comments

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

- Click on the HTML link code below.

- Copy and paste it, adding a note of your own, into your blog, a Web page, forums, a blog comment, your Facebook account, or anywhere that someone would find this page valuable.

What's New?-- site blog

Learn about new and updated pages on EnglishHints, with just enough information to decide if you want to read more.

Knowing a few roots & prefixes can help you figure out the meanings of new words. If you know ‘form’ (shape) and ‘con’ (with), you can guess that ‘conformity’ is about trying to be like others.

Do you already use English in your profession or studies-- but realize you need more advanced English or communication skills in certain areas?

I can help-- with targeted suggestions & practice on EnglishHints or with coaching or specialized help for faster results. Let me know. I can suggest resources or we can arrange a call.

Vocabulary in Minutes a Month

Sign up for our free newsletter, English Detective . In a few minutes twice a month you can:

- Improve your reading fluency with selected articles & talks on one subject (for repeated use of key words)

- Understand and practice those words using explanations, crosswords, and more

- Feel more confident about your English reading and vocab. skills-- and more prepared for big tests & challenges

For information (and a free bonus), see Building Vocabulary

Home | About me | Privacy Policy | Contact me | Affiliate Disclosure

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

thesis. (n.) late 14c., "unaccented syllable or note, a lowering of the voice in music," from Latin thesis "unaccented syllable in poetry," later (and more correctly) "stressed part of a metrical foot," from Greek thesis "a proposition," also "downbeat" (in music), originally "a setting down, a placing, an arranging; position, situation" (from ...

From Latin thesis, from Ancient Greek θέσις (thésis, “ a proposition, a statement, a thing laid down, thesis in rhetoric, thesis in prosody ”).

The word "thesis" comes from the Ancient Greek word "τίθημι" (tithēmi), meaning "to put, place, set". Meaning: A thesis is a formal written argument presented by a student or researcher to fulfill the requirements of an academic degree.

The earliest known use of the noun thesis is in the Middle English period (1150—1500). OED's earliest evidence for thesis is from before 1398, in a translation by John Trevisa, translator. thesis is a borrowing from Greek .

The term thesis comes from the Greek word θέσις, meaning "something put forth", and refers to an intellectual proposition. Dissertation comes from the Latin dissertātiō, meaning "discussion". Aristotle was the first philosopher to define the term thesis.

From τίθημι (títhēmi, “I put, place”) + -σις (-sis), although it could either have been formed in Greek or go back earlier. In the latter case, would be from a Proto-Indo-European *dʰéh₁tis, from *dʰeh₁- (root of τίθημι (títhēmi)).

thesis is Ancient Greek for "setting (down), placing", and @user438 is completely correct that the connection is that someone "sets down" arguments and propositions.

The noun 'thesis' has its etymological roots in ancient Greek. It is derived from the Greek word 'θέσις' (thésis), which means 'a setting down' or 'a position.' In the context of ancient Greece, 'thesis' was used to refer to a proposition or statement that was put forward as the basis of an argument or discussion. It represented a ...

θέσις. What does θέσις mean? θέσις (Ancient Greek) Origin & history. Could simply be from τίθημι ("I put, place") + -σις, or could go back earlier.

thesis (plural theses) - a proposition (idea proposed for debate): antithesis, hypothesis, synthesis, thesis; More English Words from Greek Roots. Here are some more English words and their relatives that came from Greek (often via Latin): anatomy; character; chorus (& choir) climate; climax; cone; cube; economics; harmony; melody; orchestra ...